undernutrition in older adults

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

firdakusumaputri -

Category

Documents

-

view

251 -

download

5

description

Transcript of undernutrition in older adults

Aging is not synonymous with poor health, despite popular societal belief. Often, patho-

logical conditions are mistaken for aspects of normal aging, both by older adults and health care profes-sionals. Undernutrition is one such pathological condition that may be disregarded because some of its symp-toms are considered characteristic of normal aging (e.g., muscle wasting, weight loss). A missed diagnosis of undernutrition can lead to complex and chronic illness, with serious ef-fects on an older adult’s physical and emotional resources, as well as on health care resources. Thus, patients and primary care providers must be aware of signs and symptoms of dis-ease versus aspects of normal healthy aging. In this article, the need for nutritional assessment across the continuum of care is addressed, and

barriers to effective treatment of un-dernutrition are identified.

BACKGROUNDUndernutrition is a broad term

meaning conditions that occur when the intake of dietary nutrients are less than adequate to sustain health. Un-dernutrition is referred to throughout the literature as malnutrition, protein energy undernutrition (PEU), pro-tein energy malnutrition (PEM), or protein calorie malnutrition (PCM), often without distinction (Kayser-Jones, 2000; McCool, Huls, Pepones, & Schlenker, 2001; Stechmiller, 2003; Xaverius, Altus, & Mathews, 1999). In this article, the term undernutrition will be used to incorporate all of these more specific terms.

Researchers have found that un-dernutrition is a significant problem in the older adult population. Accord-

ing to the literature, the prevalence of undernutrition, in older adults ranges from 5% (Sullivan, 2000) to 85% (Kayser-Jones, 2000), depending on the study’s setting. Researchers also indicate that undernutrition contrib-utes to older adult functional disability (Gary & Fleury, 2002), physical com-plications (Sullivan, 2000), morbidity and mortality (McCool et al., 2001), longer length of stay in hospitals (Gary & Fleury, 2002), and increased admissions to long-term care facilities (Gary & Fleury 2002; Huffman, 2002). Symptoms such as increased infection, electrolyte imbalance, altered skin in-tegrity, anemia, generalized weakness, and fatigue have all been associated with undernutrition (Burger, Kayser-Jones, & Bell, 2001). Additionally, the weakness and fatigue associated with undernutrition may also predispose older adults to periods of prolonged inactivity which, subsequently, can result in further complications.

These facts, combined with the in-crease in the older adult population predicted during the next few decades, suggest that undernutrition could be-come a more extensive problem in the coming years. Also noteworthy is the increased incidence of chronic disease in the older adult population. Chronic disease may cause increased dysfunc-tion in older adults, which also may affect their nutritional status (Gary & Fleury, 2002). Regardless of whether chronic disease contributes to under-nutrition or undernutrition exacer-

ABSTRACT

Undernutrition can be a significant deterrent to healthy aging and can nega-

tively affect health outcomes in older adults. Researchers have identified the

prevalence of undernutrition in older adults and the need for intervention,

yet the incidence remains high. The purpose of this article is twofold: to em-

phasize the need for nutritional assessment across the continuum of care as

experienced by older adults, and to identify possible barriers to effective treat-

ment. The assessment of nutritional status and the implementation of effec-

tive nutritional interventions are essential to the health of older adults.

ELLEN F. FURMAN, BS, RN

Undernutrition in Older Adults Across the Continuum of CareNutritional Assessment, Barriers, and Interventions

JANUARY 200622

bates chronic disease, prevention and treatment remain essential.

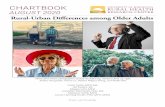

Realizing that older adults have unique nutritional needs has led to the development of a modified food pyramid for older adults (Russell, Ras-mussen, & Lichtenstein, 1999). This pyramid (adaptation represented in the Figure) acknowledges the reduced ener-gy needs of older adults and recognizes the need for increased micronutrients and hydration as compared to younger adults. Health care professionals, hav-ing also realized these unique needs, use a variety of nutritional assessment tools across health care settings to identify older adults who are under-nourished or at risk for becom-ing undernour-ished. Despite these efforts, older adults continue to ex-perience under-nutrition within the community, in the acute care hospital setting, and in long-term care facilities.

NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENTUndernutrition in Community-Dwelling Older Adults

It is estimated that 5% to 10% of community-dwelling older adults are undernourished (Sullivan, 2000). Cog-nitive changes in older adults may lead to missed meals (Chen, Schilling, & Lyder, 2001; Kayser-Jones, 2000; “Posi-tion of the American Dietetic Associa-tion [ADA],” 2000; Stechmiller, 2003). Medications can influence both feelings of satiation and absorption of nutri-ents (Chen et al., 2001; “Position of the ADA,” 2000; Stechmiller, 2003; Sullivan, 2000). Changes in dentition or the abil-ity to swallow may alter an older adult’s capability to eat, thereby limiting nutri-tional intake (Chen et al., 2001; Kayser-Jones, 2000; McCool et al., 2001; Stech-miller, 2003; Sullivan, 2000). Functional

disabilities may limit both the acquisition and preparation of food (Chen et al., 2001; “Position of the ADA,” 2000;

Stechmiller, 2003). Social isolation can lead to depression, which may influence appetite (Chen et al., 2001; Stechmiller, 2003; Sullivan, 2000). Chronic health problems may contribute to dysfunc-tion or require special diets that affect appetite (Callen & Wells, 2003). Older adults may have a limited income, which could require they forego food or compromise on the nutritional value of foods (“Position of the ADA,” 2000; Xaverius et al., 1999).

Failure to assess and treat undernutri-tion in community-dwelling older adults can lead to both physical and functional disabilities that result in ad mission to acute care hospitals, long-term care fa-cilities, or death. Two instruments may be useful for assessing undernutrition in community dwelling older adults. The Nutrition Screening Initiative (NSI),

(McCool et al., 2001) has developed a questionnaire that enables older adults to self-assess if they are at risk for under-nutrition. The NSI has also developed a second tier of its screening tool, which includes more comprehensive indica-tors of undernutrition that may be used by primary care providers within com-munity settings (Gary & Fleury, 2002). Additionally, the use of the Mini Nutri-tional Assessment (MNA) tool (Stech-miller, 2003) has been used to identify undernutrition in the older adult popu-lation with high degrees of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value. Accord-ing to Stechmiller (2003), the MNA uses anthropometric measurements, dietary questions, general health questions, and self-perceived health status questions to evaluate nutritional status.

Undernutrition in Hospitalized Older Adults

When an acute illness requires admis-sion to a hospital, older adults may be at increased risk for undernutrition and re-lated complications. It is estimated that as many as 60% of older adults either

S

Fats, oils and sweets use sparingly

Water > 8 servings

Modified Food Pyramid for 70+ Adults

Calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and

supplements

Meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs and nuts

group 2 servings

Bread, fortified cereal, rice and pasta

group 6 servings

Milk, yogurt and cheese group 3 servings

Fruit group 2 servings

Vegetable group 3 servings

Figure. Original and modified food pyramids.

SFats, oils and sweets use sparingly

Meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs and nuts group

2-3 servings

Fruit group 2-4 servings

Bread, cereal, rice and pasta

group 6-11 servings

Original Food Guide Pyramid

Vegetable group 3 servings

Milk, yogurt and cheese group 3 servings

JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL NURSING 23

are undernourished upon admission to the hospital or become undernourished during their hospital stay (Gary & Fleury, 2002). Causes of undernutrition within this setting include many of the causative factors identified for commu-nity-dwelling older adults. In addition, the food served in hospitals may not be culturally appealing or may lack the taste or texture of the foods an older adult is accustomed to eating, thereby affect-ing intake. Further changes in physical and functional health status may inhibit or prohibit oral food intake. The need for continued nutritional assessment throughout older adults’ length of stay is necessary because changes in health may necessitate changes in nutritional therapies. Also, acute illness places an additional burden on older adults. Dur-ing episodes of acute illness, physiolog-ical stress leads to catabolism which, subsequently, results in increased meta-bolic demands and a need for additional nutrition (Gary & Fleury, 2002).

The presence of undernutrition has been associated with increased length of hospital stay, increased in-hospital morbidity, and increased complica-tions, such as pressure ulcers and in-fections (Kamel, Karcic, Karcic, & Barghouthi, 2000). Studies also sug-gest that older adults who are under-nourished at discharge are at increased risk for non-elective readmission to hospitals, as well as subsequent death (Sullivan & Walls, 1998). Despite these statistics, many older adults do not re-ceive adequate nutritional assessment or treatment during their hospitaliza-tion (Kamel et al., 2000).

According to Gary and Fleury (2002), older adults are especially vulner-able because undernutrition occurs with less physiologic stress and in a shorter time than it occurs in younger adults. Thus, the assessment time is especially critical because of the current decreased length of hospital stays. However, if hospital stays are protracted because of a complex condition, older adults may become more profoundly undernour-ished and their clinical course may be-come more complicated because of their nutritional status.

According to Gary and Fleury (2002), effective nutritional assessment tools for identification of nutritional status in hospitalized patients include the MNA and the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA). The SGA uses nutritional history, including dietary changes, as well as physical findings to evaluate nutritional status (Persson, Brismar, Katzarski, Nordenstrom, & Cederholm, 2002).

Undernutrition in Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities

Long-term care facilities are thought to have the highest incidence of undernutrition of all settings across the continuum of care. It is reported that between 35% and 85% of nurs-ing home residents are undernour-ished (Kayser-Jones, 2000). Factors contributing to undernutrition in this population include factors common to community-dwellers and hospitalized older adults. In addition, older adults residing in long-term care facilities of-ten have increased physical, functional,

and cognitive deficits (the primary rea-son for admission). Because of these impairments, older adults in long-term care facilities may require either partial or total assistance to eat.

Kayser-Jones (2000) found nursing homes often were understaffed, and this resulted in residents’ receiving in-adequate assistance with eating. Con-sequently, residents’ dietary intake was insufficient. Kayser-Jones also found that the percentage of food eaten and nutritional supplements consumed by residents was often erroneously reported, leading to a discrepancy be-tween residents’ medical records and their clinical parameters. Other factors contributing to undernutrition in this setting include inactivity and lack of the social aspects of eating (e.g., eat-ing alone in bed). These factors were believed to contribute to decreases in appetite and dietary intake.

In this setting, undernutrition is of-ten assessed using the Minimum Data Set (MDS). The MDS is completed for older adults upon their admission to a long-term care facility, and con-tains a nutritional assessment portion shown to be reliable as an assessment tool (Crogan, Corbett, & Short, 2002). Use of the MDS or certain MDS vari-ables (e.g., weight loss, percentage of meals consumed, psychiatric diagno-ses, functional disabilities, age) may be useful in identifying residents who are undernourished or are at risk for undernutrition. However, the MDS is not required to be fully completed until day 14 after admission.

An additional tool that may be ben-eficial in the assessment, treatment, and management of undernutrition in this setting is the clinical guidelines formu-lated by the Council for Nutritional Clinical Strategies in Long-Term Care (Thomas, Ashman, Morley, Evans, & the Council for Nutritional Strate-gies in Long-Term Care, 2000). This tool represents a multidisciplinary ap-proach to managing undernutrition in long-term care and contains guidelines for dietary staff, nursing staff, dieti-cians, and physicians, as well as the Geriatric Depression Scale (Yesavage

CAUSES OF UNDERNUTRITION IN OLDER ADULTS

● Acute illness● Chronic illness● Cognitive impairment● Culturally unappealing foods● Depression, loneliness,

social isolation● Financial limitations● Functional disabilities● Impaired dentition or ability

to swallow

● Lack of adequate staff or inadequate education of staff

● Medications● Social conditions

– Unappealing environment– Eating alone– Eating in bed

● Unappealing taste or texture of foods

JANUARY 200624

et al., 1982-1983) and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (Alexo-poulos, Abrams, & Shamoian, 1988).

The Persistent Problem of Undernutrition

Despite all the information related to the known causes of undernutrition (Sidebar on p. 24), the known prevalence, the potential for increased incidence of undernutrition across the continuum of care, and apparently valid assessment tools, undernutrition continues to occur within the older adult population. Older adults are most often admitted to nurs-ing homes from hospitals (44%), pri-vate residences (32%), and other nurs-ing homes (12%). These older adults are most often discharged from nursing homes to hospitals (28%), die (27%), or move to other nursing homes (7.5%) (Gabrel, 1997). These data indicate that as older adults move along the continu-um of care, they are often admitted and discharged into facilities in which the prevalence of undernutrition has been well documented. Therefore, failure to adequately assess, diagnose, and treat older adults at risk for undernutrition within each setting may perpetuate, and perhaps exacerbate, this problem.

Why and how undernutrition con-tinues to occur should be of great concern to health care professionals. Undernutrition has proven extremely costly to older adults in terms of disease trajectory, health outcomes, and health care use. Barriers to effective assessment, diagnosis, and treatment must be identi-fied and overcome to help ameliorate this problem. Although further research is indicated, after reviewing the literature related to undernutrition in older adults, possible barriers are apparent.

BARRIERS TO ADEQUATE NUTRITIONUnclear Definitions

Foremost among the barriers may be the variability of definitions related to malnutrition. The term malnutri-tion is ambiguous because it may refer to both overnutrition and undernutri-tion (Gary & Fleury, 2002). However, much of the literature uses malnutri-

tion to refer to undernutrition. Addi-tionally, undernutrition may refer to the marasmus-type, the kwashiorkor-type, a combination of both (Chen et al., 2001), or a deficiency of micronu-trients (McCool et al., 2001). Marasmus is the insufficient intake of calories and kwashiorkor is the insufficient intake of proteins—both result in undernu-trition. Chen et al. also questioned whether malnutrition is the process that occurs with poor dietary intake or the state an older adult reaches after being malnourished. Without a profes-sional consensus related to terminol-ogy and definition, patients and health care workers may well be confused. Variable definitions also may compro-mise replication of research, necessary in the formulation of evidence-based clinical guidelines.

Lack of Diagnostic CriteriaAlthough nutritional assessment tools

have been shown to be valid for use in identifying older adults at risk for under-nutrition, no diagnostic tool has proven conclusive in its diagnosis. Measurement of body weight, body mass index (BMI), and other anthropometrical measures are often used to help diagnose undernutri-tion in older adults. However, changes in stature and loss of bone, tissue, and muscle mass (Gary & Fleury, 2002) that occur with normal aging can confound these data. Also, by the time changes in measures such as BMI indicate under-nourishment, it may be advanced.

Biochemical assessments have been used to help diagnose undernutrition. Examples of biochemical assessments in-clude screening for serum proteins such as albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, and total cholesterol (Gary & Fleury, 2002). However, because albumin and trans-ferrin have long half-lives, undernour-ishment may be quite advanced before it is detected. Comorbidites prevalent in older adults also have the potential to af-fect these serum values.

Often, health care professionals will use a combination of diagnostic tools including weight, diet history, BMI, anthropometrical measurements, and biochemical values, which is represen-

tative of current best practice. How-ever, lack of professional consensus related to diagnostic criteria makes de-velopment of standards for diagnosis and treatment difficult.

Confused Symptomatology and Comorbidities

Older adults and primary care pro-viders may confuse symptoms of un-dernutrition with aspects of normal aging (e.g., decreased appetite, changes in satiation, muscle wasting). This may lead to under-reporting of symptoms or under-diagnosis. Weight loss may be in-sidious, and therefore, less alarming and less reportable by the older adult. The increase in chronic health problems and associated symptoms that occur in older adults may mask symptoms of under-nutrition. Dementia may affect some older adults’ ability to provide a weight and diet history.

Limited time during primary care ap-pointments may require older adults to focus on issues that are the most prob-lematic. During an acute care hospital admission, the plan of care may focus more on the condition that lead to the admission, rather than on a more holis-tic approach to care. The admission of the older adult to a long-term care facil-ity may present additional risk because of older adults’ increased frailty and in-creased incidence of undernutrition in these facilities.

Fragmented CareAnother barrier to successful as-

sessment, diagnosis, and treatment of undernutrition may be lack of coordi-nation of care (“Position of the ADA,” 2000). Kowanko, Simon, and Wood (1999) found that nurses had knowl-edge deficits and role conflict related to various aspects of patient nutrition. Be-lieving that the dietician is responsible for the nutritional care of older adults in hospitals and long-term care facilities can result in poorer care. The delegation of oral feeding to aides should not mini-mize the nurse’s role in the assessment of nutritional status. As at-risk and un-dernourished older adults move back and forth along the continuum of care,

JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL NURSING 25

lack of methods to track interventions and outcomes limit the evaluation of treatment that would provide for a continued plan of care.

Lack of Treatment OptionsAnother barrier to adequate nutri-

tion may be lack of treatment options. Primary care providers, unsure of an older adult’s disease trajectory, may de-lay changes in nutritional therapies. The invasiveness of a feeding tube may make placement a poor choice for both patient and primary care provider. Complica-tions associated with long-term use of parenteral nutrition may limit use and, according to Bowers (1999):

The standard intravenous infu-sion of 100 to 150 grams of glucose in an electrolyte solution, does not meet minimal nutritional requirements for a 24 hour period, much less for days or weeks....and if the diet is significantly inadequate for more than a few days catabolism begins (p. 147).

Therefore, should an older adult’s nutrition be deemed less than ad-equate for more than a few days, prompt implementation of nutritional therapy should be instituted to avoid further complications.

Medication MismanagementSome medications that cause an-

orexia or interfere with the absorption of nutrients may contribute to un-dernutrition. Commonly prescribed medications such as metformin, spi-ronolactone, digoxin, amantadine, and fluoxetine have been associated with anorexia, and antacids and antibiotics may contribute to malabsorbtion of nutrients (White & Ashworth, 2000). Also, pharmocokinetics are different in older adults and should be assessed on an individual basis (Edmunds & Mayhew, 2000). Polypharmacy, preva-lent in the older adult population, must be assessed as an etiology of decreased appetite and weight loss.

INTERVENTIONSCommunity-Dwelling Older Adults

Undernutrition treatment must focus on the etiology of the condi-

tion after at-risk older adults within the community are identified. Nutri-tional programs, such as the Elderly Nutrition Program, provide home delivered meals and congregate meals for older adults. These programs have been shown to improve nutritional intake (McCool et al., 2001). Social connectedness has been shown to positively influence appetite (Callen & Wells, 2003); therefore, maintenance or establishment of social relationships should be encouraged. Oral examina-tions should be performed routinely. Educational programs for both older adults and caregivers should focus on the recommended intake of vari-ous nutrients, identification of nutri-ent dense foods, positive feedback for healthy food choices (Xaverius et al., 1999), and the use of nutritional sup-plements as indicated by the primary care provider. Primary care providers, pharmacists, nurses, and older adults must be aware of interactions between drugs, foods, and conditions, and pre-scribe, dispense, and administer ap-propriate medications accordingly.

Hospitalized Older AdultsAfter a nutritional assessment com-

pleted on admission has identified older adults at risk of becoming undernour-ished during their acute illness, early in-terventions should be aimed at reversing or preventing further decline. Thera-peutic diets, diets of varying consisten-cies, small and more frequent meals, and dietary supplements may be used if the older adult is able to swallow and has a functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Bowers, 1999; McCool et al., 2001). If the older adults’ ability to swallow or the gag reflex is compromised, enteral feedings via feeding tube is an alterna-tive therapy. Should an older adult have a non-functioning GI tract, parenteral nutrition should be started.

The multidisciplinary team must consider the older adult holistically. Nutritional aspects of care are included in this holistic approach. Consultation among all team members throughout the nursing process is necessary so qual-ity care can be provided.

Older Adults Living in Long Term Care Facilities

Suggested treatments for undernutri-tion in this setting include:

● Specialized diets or discontinua-tion of dietary restrictions in an attempt to stimulate appetite.

● Nutritional supplements (Huff-man, 2002).

● Increased dietary selections including more culturally appropriate meals.

● Increased staff and training of staff in the techniques of safe and effec-tive feeding techniques.

● Designated areas for dining (Kayser-Jones, 2000).

● Enteral and parenteral nutrition (Bowers, 1999).

An older adult’s willingness to eat, which affects appetite, has been associ-ated with positive mood, independence, good health, well-prepared food, a clean and cheerful eating environment, and ca-maraderie with other residents (Wikby & Fagerskiold, 2004). Therefore, inter-ventions implemented to maximize older adults’ independence and functionality as well as contribute to an aesthetic eat-ing environment may improve appetite.

CONCLUSIONSA dichotomy exists between knowl-

edge and treatment of undernutrition in the older adult population. Although some symptoms of undernutrition may appear similar to characteristics of normal aging, health care professionals working with and caring for older adults should be expert in their abilities to holistically assess and diagnose symptoms of un-dernutrition. The increased prevalence of undernutrition in this population should substantiate screening practices that identify older adults at risk so pre-ventative practices can be implemented before the condition becomes problem-atic. Awareness that undernutrition may be a prevailing problem or an underly-ing problem in older adults with other comorbidites should increase routine screening practices.

Additionally, the screening and as-sessment of nutritional status must be ongoing, corresponding to changes in

JANUARY 200626

older adults’ physical, functional, and cognitive status. This requires a com-prehensive assessment of all indicators of undernutrition throughout the con-tinuum of care as experienced by older adults. Nutritional assessment tools are available and have been proven valid in identifying older adults who are un-dernourished or at risk for becoming undernourished. However, because no single diagnostic tool has been proven conclusive in the diagnosis of undernu-trition, health care professionals must use a variety of available tools to ensure treatment is implemented promptly. This process must be well documented so the effectiveness of treatment can be evaluated as the older adult moves across the continuum of care. Failure to evalu-ate older adults’ nutritional history can lead to delayed treatment, which may result in poorer health outcomes.

Research indicates that undernutriton contributes to unhealthy aging. Poten-tial barriers to adequate nutrition must be overcome if older adults are to age healthily across the continuum of care. Older adults have unique nutritional needs and vulnerabilities and, therefore, nutritional status must be assessed con-tinuously throughout their care. Further research is needed to identify why un-dernutrition continues to occur; barriers to treatment; implications in this popula-tion; and better methods to assess, diag-nose, and treat this condition.

REFERENCESAlexopoulos, G.S., Abrams, R.C., Shamoian, C.A.

(1988). Cornell Scale for Depression in Demen-tia. Biological Psychiatry, 23(3), 271-84.

Bowers, S. (1999). Nutrition support for malnour-ished, acutely ill adults. Medsurg Nursing, 8(3), 145-165.

Burger, S.G., Kayser-Jones, J., & Bell, J. P. (2001). Food for thought. Contemporary Long Term Care, 24(4), 24-28.

Callen, B.L., & Wells, T.J. (2003). Views of commu-nity-dwelling, old-old people on barriers and aids to nutritional health. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 35(3), 257-262.

Chen, C.C.-H., Schilling, L.S., & Lyder, C.L. (2001) A concept analysis of malnutrition in the elderly. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(1), 131-142.

Crogan, N.L., Corbett, C.F., & Short, R.A. (2002). The minimum data set: Predicting malnutrition in newly admitted nursing home residents. Clinical Nursing Research, 11(3), 341-353.

Edmunds, M.W., & Mayhew, M.S. (2000). Pharma-cology for the primary care provider. St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Gabrel, C.S. (1997). Characteristics of elderly nurs-ing home current residents and discharges: Data from the 1997 National Nursing Home Survey. Advance Data, 312, 1-16.

Gary, R., & Fleury, J. (2002) Nutritional status: Key to preventing functional decline in hospitalized older adults. Topics of Geriatric Rehabilitation, 17(3), 40-71.

Huffman, G.B. (2002). Evaluating and treating un-intentional weight loss in the elderly. American Family Physician, 65(4), 640-650.

Kamel, H.K., Karcic, E., Karcic, A., & Barghouthi, H. (2000). Nutritional status of hospitalized elderly: Differences between nursing home patients and community-dwelling patients. An-nals of Long-Term Care, 8(3), 33-38.

Kayser-Jones, J. (2000). Improving the nutritional care of nursing home residents. Nursing Homes Long Term Care Management, 49(10), 56-59.

Kowanko, I., Simon, S., & Wood, J. (1999). Nutri-tional care of the patient: Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes in an acute care setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8, 217-224.

McCool, A.C., Huls, A., Pepones, M., & Schlenker, E. (2001). Nutrition for older persons: A key to healthy aging. Topics in Clinical Nutrition, 17(1), 52-71.

Persson, M.D., Brismar, K.E., Katzarski, K.S., Nordenstrom, J., & Cederholm, T.E. (2002). Nutritional status using mini nutritional as-sessment and subjective global assessment predict mortality in geriatric patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(12), 1996-2002.

Position of the American Dietetic Association: Nu-trition, aging, and the continuum of care. (2000, May). Journal of the American Dietetic Associa-tion, 100(5), 580-595.

Russell, R.M., Rasmussen, H., & Lichtenstein, A.H. (1999). Modified food guide pyramid

for people over seventy years of age. Journal of Nutrition, 129, 751-753.

Stechmiller, J.K. (2003). Early nutritional screening of older adults. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 26(3), 170-177.

Sullivan, D.H. (2000). Undernutrition in older adults. Annals of Long-Term Care, 8(5), 41-46.

Sullivan, D.H., & Walls, R.C. (1998). Protein-energy undernutrition and the risk of mortality within six years of hospital discharge. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 17(6), 571-578.

Thomas, D.R., Ashmen, W., Morley, J.E., Evans, W.J., & the Council for Nutritional Strategies in Long-Term Care. (2000). Nutritional manage-ment in long-term care: Development of a clini-cal guideline. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 55A(12), M725-M734.

White, R., & Ashworth, A. (2000). How drug therapy can affect, threaten, and compromise nutritional status. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 13(2), 119-129.

Wikby, K., & Fagerskiold, A. (2004). The willing-ness to eat: An investigation of appetite among elderly people. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 18, 120-127.

Yesavage, Y.A., Brink, T.L., Rose, T.L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., et al. (1982-1983). Devel-opment and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37-49.

Xaverius, P.K., Altus, D., & Mathews, R.M. (1999). Malnutrition of elders: A review of the literature and suggestions for a comprehensive treatment program. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 19(1), 41-47.

ABOUT THE AUTHORMs. Furman is Advanced Practice student,

University of Massachusetts, Amherst.Address correspondence to Ellen F.

Furman, BS, RN, 104 Wildflower Circle, Westfield, MA 01085.

KEYPOINTS

UNDERNUTRITION IN OLDER ADULTSFurman, E.F. Undernutrition in Older Adults Across the Continuum of Care: Nutritional Assessment, Barriers, and Interventions. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 2006, 32(1): 22-27.

1 Undernutrition can significantly affect the health of older adults, and nurses must consider the unique nutritional needs of this population.

2 Nutritional assessment of older adults occurs across the continu-um of care, yet the incidence of undernutrition remains high.

3 Nutritional assessment, treatment, and evaluation must be ongo-ing as older adults move across the continuum of care.

4 Possible barriers to nutritional health must be overcome for older adults to maintain optimal health as they age.

JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL NURSING 27