UMS Teacher Resource Guide - Ladysmith Black Mambazo

-

Upload

omari-rush -

Category

Documents

-

view

225 -

download

3

description

Transcript of UMS Teacher Resource Guide - Ladysmith Black Mambazo

1UMS 09-10

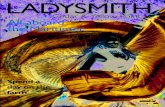

L A D Y S M I T HB L A C K M A M B A Z O

T E A C H E R R E S O U R C E G U I D E

2 0 0 9 - 2 0 1 0

2 UMS 09-10

Michigan Council for Arts & Cultural Affairs

University of Michigan

Anonymous

Arts at Michigan

Arts Midwest’s Performing Arts Fund

Bank of Ann Arbor

Bustan al-Funun Foundation for Arab Arts

The Dan Cameron Family Foundation/Alan and Swanna Saltiel

Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan

Consulate General of the Netherlands in New York

Doris Duke Charitable Foundation

Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Art

DTE Energy Foundation

The Esperance Family Foundation

David and Phyllis Herzig Endowment Fund

Honigman Miller Schwartz and Cohn LLP

JazzNet Endowment

W.K. Kellogg Foundation

Masco Corporation Foundation

Miller, Canfield, Paddock and Stone, P.L.C.

THE MOSAIC FOUNDATION (of R. and P. Heydon)

The Mosaic Foundation [Washington, DC]

National Dance Project of the New England Foundation for the Arts

National Endowment for the Arts

Prudence and Amnon Rosenthal K-12 Education Endowment Fund

Rick and Sue Snyder

Target

TCF Bank

UMS Advisory Committee

University of Michigan Credit Union

University of Michigan Health System

U-M Office of the Senior Vice Provost for Academic Affairs

U-M Office of the Vice President for Research

Wallace Endowment Fund

This Teacher Resource Guide is a product of the UMS Youth Education Program. Researched, written, and edited by Carlos Palomares and Cahill Smith.

Special thanks to Savitski Design and Omari Rush for their contributions, feedback, and support in developing this guide.

SUPPORTERS

For an additional opportunity to see Ladysmith Black Mambazo, attend this public perfor-mance:

Ladysmith Black Mambazo Sunday, January 31, 4 pm Hill Auditorium

Call the UMS Ticket Office at 734-764-2538 for tickets to this public performance. Note: public performance ticket prices differ significantly from Youth Performance ticket prices and Ticket Office staff can provide full details on avail-ability and cost.

3UMS 09-10

Photo: Rajesh Jantilal

L A D Y S M I T HB L A C K M A M B A Z O

GRADES K-12

1 1 A M - 1 2 N O O N

MONDAY

FEBRUARY 1

2 0 1 0HILL

AUDITORIUM

T E A C H E R R E S O U R C E G U I D E 2 0 0 9 - 2 0 1 0

U M S Y O U T H E D U C AT I O N P R O G R A M

4 UMS 09-10

ATTENDING THE PERFORMANCE6 Attending the Show8 Map + Directions9 HIll Autitorium

LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO11 Overview12 Ensemble History14 Meet the Singers15 Joseph Shabalala18 Further Resources

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABOUT SOUTH AFRICA19 South Africa21 A Timeline25 The Provinces 26 Population 28 The Zulu People31 Ilemb33 Further Resources

ABOUT THE MUSIC35 South African Music38 Isicathamiya39 Further Resources

CONNECTIONS42 Appreciating the Performance44 For Students + Educators45 Community

ABOUT UMS47 University Musical Society49 Youth Education Program51 Send Us Feedback!

Short on time?If you only have 15 minutes to review this guide, just read the sections in black in the Table of Contents.

Those pages will provide the most important information about this performance.

5UMS 09-10

AT T E N D I N G T H E P E R F O R M A N C E

Photo: Ladysmith

6 UMS 09-10

TICKETS We do not use paper tickets for

Youth Performances. We hold school reserva-

tions at the door and seat groups upon arrival.

DOOR ENTRY A UMS Youth Performance

staff person will greet your group at your bus

as you unload and escort you on a sidewalk to

your assigned entry doors of Hill Auditorium.

BEFORE THE START Please allow the usher

to seat individuals in your group in the order

that they arrive in the theater. Once everyone

is seated you may then rearrange yourselves

and escort students to the bathrooms before

the performance starts. PLEASE spread the

adults throughout the group of students.

DURING THE PERFORMANCE At the

start of the performance, the lights well

dim and an onstage UMS staff member will

welcome you to the performance and provide

important logistical information. If you have

any questions, concerns, or complaints (for

instance, about your comfort or the behavior

of surrounding groups) please IMMEDIATELY

report the situation to an usher or staff memer

in the lobby.

PERFORMANCE LENGTH One hour with

no intermission

AFTER THE PERFORMANCE When the

performance ends, remain seated. A UMS

staff member will come to the stage and

release each group individually based on the

location of your seats.

SEATING & USHERS When you arrive at

the front doors, tell the Head Usher at the

door the name of your school group and he/

she will have ushers escort you to your block

of seats. All UMS Youth Performance ushers

wear large, black laminated badges with their

names in white letters.

ARRIVAL TIME Please arrive at the Hill

Auditorium between 10:30-10:50pm to allow

you time to get seated and comfortable before

the show starts.

DROP OFF Have buses, vans, or cars drop off

students on East Washington, Thayer or North

University streets based on the drop off as-

signment information you receive in the mail.

If there is no space in the drop off zone, circle

the block until space becomes available. Cars

may park at curbside metered spots or in the

visitor parking lot behind the power Center.

Buses should wait/park at Briarwood Mall.

DETAILS

AT T E N D I N G T H E S H O WWe want you to enjoy your time with UMS!

PLEASE review the important information below about attending the Youth Performance:

TICKETS

USHER

7UMS 09-10

BUS PICK UP When your group is released,

please exit the performance hall through the

same door you entered. A UMS Youth Perfor-

mance staff member will be outside to direct

you to your bus.

AAPS EDUCATORS You will likely not get

on the bus you arrived on; a UMS staff mem-

ber or AAPS Transportation Staf person will

put you on the first available bus.

LOST STUDENTS A small army of volun-

teers staff Youth Performances and will be

ready to help or direct lost and wandering

students.

LOST ITEMS If someone in your group loses

an item at the performance, contact the UMS

Youth Education Program (umsyouth@umich.

edu) to attempt to help recover the item.

AAPS

SENDING FEEDBACK We LOVE feedback

from students, so after the performance please

send us any letters, artwork, or academic

papers that your students create in response

to the performance: UMS Youth Education

Program, 881 N. University Ave., Ann Arbor,

MI 48109-1011.

NO FOOD No Food or drink is allowed in

the theater.

PATIENCE Thank you in adavance for your

patience; in 20 minutes we aim to get 3,500

people from buses into seats and will work as

efficiently as possible to make that happen.

ACCESSIBILITY The following services are

available to audience members:

• Courtesy wheelchairs

• Hearing Impaired Support Systems

PARKING There is handicapped parking

located in the South Thater parking structure.

All accessible parking spaces (13) are located

on the first floor. To access the spaces, driv-

ers need to enter the structure using the

south (left) entrance lane. If the north (right)

entrance lane, the driver must drive up the

ramp and come back down one level to get

to the parking spaces.

WHEELCHAIR ACCESSIBILITY Hill Au-

ditorium is wheelchair accessible with ramps

found on the east and west entrances, off

South Thayer Street and Ingalls Mall. The au-

ditorium has 27 accessible seating locations

on its main floor and 8 on the mezzanine

level. Hearing impairment systems are also

available.

BATHROOMS ADA compliant toilets are

available near the Hill Auditorium box office

(west side facing South Thayer).

ENTRY There will be ushers stationed at

all entrances to assist with door opening.

Wheelchair, companion, or other special

seating

8 UMS 09-10

POWER

HILL

ZONE C

ZONE A

ZO

NE

B

PARK

PALMER DRIVE

E. HURON ST

E. WASHINGTON ST

E. L IBERTY ST

WILLIAM ST N. UNIVERSITY AVENUE

WA

SH

TE

NA

W A

VE

NU

E

FLET

CH

ER

ST

TH

AY

ER

ST

STA

TE

ST

CH

UR

CH

ST

MA

LL PAR

KIN

G &

RACKHAM

M A P + D I R E C T I O N SThis map, with driving directions to the Hill Auditorium, will

be mailed to all attending educators three weeks before the performance.

MAP

9UMS 09-10

H I L L A U D I T O R I U M

VENUE

HILL AUDITORIUM was built by noted

architectural firm Kahn and Wilby.

Completed in 1913, the renowned

concert hall was inaugurated at the

20th Ann Arbor May Festival, and has

continued to be the site of thousands

of concerts, featuring everyone from

Leonard Bernstein and Cecilia Bartoli to

Bob Marley and Jimmy Buffett.

In May, 2002, Hill Auditorium under-

went an 18-month, $38.6-million dollar

renovation, updating the infrastructure

and restoring much of the interior to its

original splendor. Exterior renovations

included the reworking of brick paving

and stone retaining wall areas, restora-

tion of the south entrance plaza, the

reworking of the west barrier-free ramp

Photo: Mike Savitski

and loading dock, and improvements to

landscaping.

Interior renovations included the

creation of additional restrooms, the

improvement of barrier-free circulation

by providing elevators and an addition

with ramps, the replacement of seating

to increase patron comfort, introduction

of barrier-free seating and stage access,

the replacement of theatrical perfor-

mance and audio-visual systems, and

the complete replacement of mechanical

and electrical infrastructure systems for

heating, ventilation, and air condition-

ing. Re-opened in January, 2004, Hill

Auditorium now seats 3,538.

HILL AUDITORIUM

850 North University Ave

Ann Arbor, MI 48109

Emergency Contact

Number:

(734) 764-2538(Call this number to reach a UMS staff person or

audience member at the performance.)

10 UMS 09-10

L A D Y S M I T H B L A C K M A M B A Z O

11UMS 09-10

LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO is an

all-male, a capella vocal ensemble from

South Africa.

Assembled in the early 1960s, in South

Africa, by Joseph Shabalala – then a

young farmboy turned factory worker

– the group took the name Ladysmith

Black Mambazo. Ladysmith refers to the

name of Shabalala’s rural hometown,

Black refers to oxen, the strongest of

all farm animals, and Mambazo, the

Zulu word for axe, is a symbol of the

group’s vocal ability to “chop down” all

competition. Their collective voices were

so tight and their harmonies so polished

that they were eventually banned from

isicathamiya competitions, although

they were welcome to participate strictly

as entertainers.

Though a vital and popular contempo-

rary song-and-dance style, isicathamiya

has roots in older Zulu musical and

dance idioms that still flourish within

certain rural communities in South Afri-

ca. The isicathamiya style was developed

largely by Zulu-speaking migrant work-

ers, and over time, the style has drawn

into itself traces of such other idioms as

American minstrelsy, vaudeville, spiritu-

als, missionary hymnody, Tin Pan Alley,

Hollywood tap-dance, and gospel music.

The name isicathamiya is of relatively

recent origin, and is inseparable from

Joseph Sabalala’s impact on the shap-

ing of the style over the last thirty years.

Joseph Shabalala is not only the most

prolific living composer of isicathamiya

music; he is also the style’s foremost

recording artist. (Ballantine 3,4)

While a radio broadcast in 1970 opened

the door to their first record contract,

Ladysmith Black Mambazo was intro-

duced to an international audience in

the mid-1980s when Paul Simon traveled

to South Africa and met Joseph Shabalala

and the other members of Ladysmith

Black Mambazo in a recording studio in

Johannesburg. Simon was captivated by

the stirring sound of bass, alto and tenor

harmonies and incorporated these tradi-

tional sounds in Graceland, a landmark

1986 recording that won the Grammy

Award for Best Album and is considered

seminal in the creation of “World Music”

as a music industry marketing genre.

Since then, Ladysmith Black Mambazo

has gone on to its own successful inter-

national career, performing worldwide,

recording over fifty albums, andwinning

several Grammy awards. On January

31, 2009, Ladysmith Black Mambazo

will perform at Hill Auditorium in Ann

Arbor,Michigan.

Sources: http://imnworld.com/artists/detail/24/ladysmith-black-mambazo

Ballantine, Chirstopher. “Joseph Shabalala: Chronicles of an African Composer.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology, Vol. 5 (1996), pp. 1-38.

O V E R V I E WL A D Y S M I T H B L A C K M A M B A Z O

ABOUT

12 UMS 09-10

E N S E M B L E H I S T O RY

ABOUT

LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO is

regarded as a cultural emissary at home

and around the world representing the

traditional culture of South Africa. For

more than forty years, Ladysmith Black

Mambazo has married the intricate

rhythms and harmonies of their na-

tive South African musical traditions to

the sounds and sentiments of Christian

gospel music. The result is a musical and

spiritual alchemy that has touched a

worldwide audience representing every

corner of the religious, cultural and

ethnic landscape. To many, they are a na-

tional treasure of the new South Africa in

part because they embody the traditions

suppressed in the old South Africa.

The traditional music sung by Ladysmith

Black Mambazo is called isicathamiya.

It was born in the mines of South Africa.

Black workers were taken by rail to work

far away from their homes and their

families. Poorly housed and paid worse,

they would entertain themselves, after

a six-day week, by singing songs into

the wee hours every Sunday morning.

Cothoza Mfana they called themselves,

“tip toe guys”, referring to the dance

steps choreographed so as to not disturb

the camp security guards. When miners

returned to the homelands, the tradi-

tion returned with them. There began a

fierce, but social, competition held regu-

larly and a highlight of everyone’s social

calendar. The winners were awarded a

goat for their efforts and, of course, the

adoration of their fans. These competi-

tions are held even today in assembly

halls and church basements throughout

Zululand South Africa.

In the late 1950’s Joseph Shabalala took

advantage of his proximity to the urban

sprawl of the city of Durban, allowing

him the opportunity to seek work in a

factory. Leaving the family farm was not

easy, but it was during this time that

Joseph first showed a talent for sing-

ing. After singing with several groups in

Durban he returned to his hometown

of Ladysmith and began to put together

groups of his own. He was rarely satis-

fied with the results. “I felt there was

something missing. I tried to teach the

music that I felt but I failed, until 1964,

when a harmonious dream came to me.

I always heard the harmony from that

dream and I said ‘This is the sound that

I want and I can teach it to my guys’.”

Joseph recruited family and friends. He

taught the group the harmonies from his

dreams. With time and patience Joseph’s

work began to gel into a special sound.

Shabalala says his conversion to Chris-

tianity, in the ‘60s, helped define the

group’s musical identity. The path that

the axe was chopping suddenly had

a direction: “To bring this gospel of

loving one another all over the world,”

he says. However, he is quick to point

out that the message is not specific to

any one religious orientation. “Without

hearing the lyrics, this music gets into

the blood, because it comes from the

blood,” he says. “It evokes enthusiasm

and excitement, regardless of what you

follow spiritually.”

Their musical efforts over the past four

decades have garnered praise and ac-

colades within the recording industry.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s discography

currently includes more than forty record-

ings, garnering three Grammy Awards

and fifteen nominations, including one

for their most recent recording Ilembe:

Honoring Shaka Zulu. In addition to

their work with Paul Simon, Ladysmith

Black Mambazo have recorded with

numerous artists from around the world,

including Stevie Wonder, Josh Groban,

Dolly Parton, Sarah McLaughlin, Em-

mylou Harris, Natalie Merchant, Mavis

Staples, Ry Cooder and Ben Harper. They

have appeared in film, soundtracks and

commercials. A film documentary titled

On Tip Toe: Gentle Steps to Freedom,

the story of Ladysmith Black Mambazo,

was nominated for an Academy Award

for Best Documentary. The group has also

performed at two Nobel Peace Prize Cer-

emonies, a performance for Pope John

Paul II, the South African Presidential in-

augurations, the 1996 Summer Olympics,

and many musical award shows from

around the world.

Amid extensive worldwide touring, the

ambitious recording schedule and the

numerous accomplishments and acco-

lades, tragedy struck the group in 2002

when Nellie Shabalala, Joseph’s wife of

thirty years, was murdered by a masked

gunman outside their church in South

Africa. “At the time that this happened,

I tried to take my mind deep into the

spirit, because I know the truth is there,”

Shabalala recalls. “In my flesh, I might

be angry, I might cry, I might suspect

somebody. But when I took my mind into

the spirit, the spirit told me to be calm

and not to worry. Bad things happen,

and the only thing to do is raise your

spirit higher.”

Out of this dark chapter came Raise

Your Spirit Higher -Wenyukela, Black

Mambazo’s brilliant debut recording on

Heads Up International, released in 2004

to coincide with the 10-year anniversary

of the end of apartheid. The album was

Shabalala’s message of hope and unity

to a troubled world. “When the world

looks at you and finds the tears in your

eyes,” says Shabalala, “but you smile in

spite of the tears, then they discover that,

‘Oh, he’s right when he says you must be

strong, because many things have hap-

pened to him, and he still carries on with

the spirit of the music.’”

Ladysmith Black Mambazo celebrated

twelve years of democracy in the Repub-

lic of South Africa with the January 2006

release of Long Walk to Freedom, a

collection of twelve new recordings of

classic Mambazo songs with numer-

ous special guests, including Melissa

Etheridge, Emmylou Harris, Taj Mahal,

Joe McBride, Sarah McLachlan, Natalie

Merchant, and Zap Mama. Also appear-

ing on this monumental recording are a

number of South African international

icons lending their support to the South

African anthem “Shosholoza,” including

Hugh Masekela, Vusi Mahlasela, Lucky

Dube, Nokukhanya and others.

Two years later, the group paid tribute

to Shaka Zulu, the iconic South African

warrior who united numerous regional

tribes in the late 1800s and became the

first king of the Zulu nation. Ilembe:

Honoring Shaka Zulu was released in

January 2008. The newest offering from

the group is Ladysmith Black Mambazo

Live! (HUDV 7149), a DVD set for release

in January 2009. The visual feast captures

fourteen songs performed on the stage

of EJ Thomas Hall at the University of

Akron in Akron, Ohio, as well as forty

minutes of in-depth interviews with Sha-

balala and other members of the group.

Meanwhile, traditional life in South Africa

continues to change. Cable television,

MTV, the internet and other international

influences are taking its toll on tradition,

and Joseph sees the wonder and the peril

in this progress. Always a man to find

faith in his dreams, Joseph’s life ambition

now is to establish the first Academy for

the teaching and preservation of indig-

enous South African music and culture in

South Africa.

Joseph continues teaching young children

the traditions of his his elders. Joseph’s

appointment as an associate professor

of ethnomusicology at the University of

Natal has given him a taste of the life

of a scholar. “It’s just like performing,”

says Joseph, beaming. “You work all day,

correcting the mistakes, encouraging the

young ones to be confident in their ac-

tion. And if they do not succeed, I always

criticize myself. I am their teacher. They

are willing to learn. But it is up to me to

see they learn correctly.” Over the years,

with the retirement of several members

of the group, Joseph has enlisted the tal-

ents of his four sons,the next Mambazo

generation. They bring a youthful energy

to the group, ensure the preservation of

the teachings and the traditions of the

South African.

The group has devoted itself to raising

consciousness of South African culture.

Attracting the financial and moral sup-

port of many, including Danny Glover

and Whoopi Goldberg, was just the

beginning. Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s

continues to spread the word of Joseph’s

dream of preservation through educa-

tion, while encouraging all those who

can to give their support.

Compiled from the following sources:

http://imnworld.com/artists/detail/24/ladysmith-black-mambazo www.rockpaperscissors.biz/index.cfm/fuseaction/current.bio/project_id/245.cfm www.mambazo.com/biography.html www.concordmusicgroup.com/artists/Ladysmith-Black-Mambazo/

13UMS 09-10

14 UMS 09-10

M E E T T H E S I N G E R S

PEOPLE

J O S E P H S H A B A L A L A

Soprano

T H A M S A N Q A S H A B A L A L A Alto

S I B O N G I S E N I S H A B A L A L A Bass

T H U L A N I S H A B A L A L A Bass

M S I Z I S H A B A L A L A Tenor

R U S S E L M T H E M B U Bass

A L B E RT M A Z I B U K O Tenor

A B E D N E G O M A Z I B U K O

Bass

N G A N E D L A M I N I Bass

THE PERSONNEL of Ladysmith Black

Mambazo has changed many times

over the years. the original group was

composed of Joseph Shabalala, his

brothers Headman and Enoch; in-laws

Albert, Milton, and Joseph Mazibuko;

and close friend Walter Malinga. Aside

from Joseph Shabalala, Albert Mazibuko

is the only original member left in the

group. Altogether, the group has had

over 30 different members over the past

forty-five years.

Even though the early line-ups of the

group contained mostly relatives from

Shabalala’s family, many of the members

that joined the group after the mid-

1970s were recruited for their profes-

sional qualities. Abednego Mazibuko

joined the group in 1974 and Russel

Mthembu in 1975, both as bass voices.

After alto voice Milton Mazibuko was

murdered in 1980, the group took a

few months offbefore returning the

following year with two new members,

Inos Phungula and Geophrey Mdletshe.

Another long hiatus ensued after the

murder of Joseph’s younger brother

Headman on December 10, 1991. The

group stopped singing for a while be-

fore Joseph recruited four of his six sons.

Joseph Shabalala’s sons Thamsanqa,

Sibonnngiseni, Thulani, and Msizi joined

the group in 1993, moving up from Lady-

smith Black Mambazo’s junior choir, Msh-

engu White Mambazo that was formed

by Joseph in the 1970s. Long-time mem-

ber Jockey Shabalala died in his home in

Ladysmith on February 11, 2006. He was

62, and was a member of the group for

almost forty years. Thamsanqa Shabalala

will take over as the leader of the group

after his father’s retirement.

The members of the group currently re-

side in Kloof, just outside of the coastal

city of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal -

though due to their heavy performance

schedule, the group spends only brief

periods at home.

Sources: Wikipedia “Ladysmith Black Mambazo” Erlmann, V: “Nightsong”, brief history of Ladysmith Black Mambazo (page 93). The University of Chicag Press, 1996

Photo: Rajesh Janeilal

15UMS 09-10

J O S E P H S H A B A L A L A

PEOPLE

THE FOLLOWING EXCERPTS from “Jo-

seph Shabalala: Chronicles of an African

Composer” by ethnomusicologist Chris-

topher Ballantine are included to give

the reader insight into Shabalala’s ap-

proach to music composition. Ballantine

looks at Shabalala’s education, methods,

and asthetics in composition includ-

ing some of Shabalala’s written notes.

Through conversations with Shablala,

Ballantine creates a sketch of Shabalala’s

creative procedures to “begin to gain

a deeper understanding of the creative

musical process itself” (37).

How did Shabalala learn to compose?

His answer was startling: for a period

of six months in 1964, he was visited in

his dreams every night by a choir “from

above” who sang to him. It was, he

says, just like a nightly show in which

he was the only listener. “I’m sleeping

but I’m watching the show. I saw myself

sleeping but watching just like when

you are watching TV.” Shabalala com-

pares this experience to that of going to

music school. (5)

If the dreamtime encounters were for

Shabalala the equivalent of going to a

music school, a later dream assumed

the significance of a final examination

and graduation ceremony, giving him

the confidence and authority to become

the composer-leader of an isicathamiya

group. He dreamt he was sitting on a

revolving chair in the middle of a circle

of twenty-four wise old men: “I used to

call them the senior, the golden oldies

married men-the old ones with white

hair.” Each of them was to address him

with one question, and if he answered

the questions satisfactorily, the circle of

elders would declare him fit to be “a

leader of musicians.” (6)

For Zulu traditionalists,dreams are not

only a pathway for communication be-

tween “the survivors and the shades,”

are also a vital, purposeful activity in

the lives of Zulu people. Joseph Sha-

balala and other traditionalists believe

that dreams can be a way of reaching

focused insight and a means of self-

empowerment. (7)

Joseph Shabala, Photo: R. Hoffman

16 UMS 09-10

ing a performance, he will humorously

encourage them to give a little more (or a

little less) by gesturing in the direction of

the bellies of one or more of his singers.

With a movement of his hand, he sug-

gests that he is turning up (or down) the

volume control on an amplifier.

A little more freedom is granted to the

group when they have performed a song

many times and are very familiar with it;

however such liberties are underpinned

by a belief that individual freedom and ex-

pression should not jeopardize the identity

or the coherence of the group. (16, 17)

E D U C AT I O N

Shabalala is committed to the notion

that his compositions should go out

into the world and make a difference.

He holds that he must share his com-

positional knowledge, insight, and

experience. The principal beneficiaries

of such sharing are other composers

in the isicathamiya tradition, but this

activity also reaches various other musi-

cians, students, and so on. Since about

1992, Shabalala has begun trying to

consolidate and summarize, in written

form, the knowledge and principles

he believes may be of most help to the

composers who seek his assistance. (21)

Compiled from source:Ballantine, Chirstopher. “Joseph Shabalala: Chronicles of an African Composer.” British Journal of Ethnomusicology, Vol. 5 (1996), pp. 1-38 www.jstor.org/stable/3060865 Accessed: 12/11/2009

COMPOSITIONAL THEMES

M U S I C F O R P E A C E

“Music is for peace. When you sing,

you feel like you want people to

come together and love each other

and share ideas.” And this has always

driven him. (13)

D O S O M E T H I N G N E W

One demand Shabalala always makes

of himself as a composer [is] to try to

do something new. At one level, this

means nothing more than that he seeks

to satisfy his audiences’ appetite for

new Ladysmith Black Mambazo songs.

At another level, though, is the injunc-

tion Shabalala places on himself to be

original, to surpass himself, to do what

has never been achieved before within

the isicathamiya style. Indeed, it is his

sense that he is capable of originality that

keeps him going. (15)

I M P R O V I S AT I O N

Only Shabalala’s solo part is normally

improvised and he maintains that neither

he nor the group know in advance the

details of what he is going to do. The

only thing of which he is certain is that

he will improvise, and the ability to do so

will come from an inspirational force that

he calls “the spirit.” Beyond the arena

of his own solo part, Shabalala permits

the members of his group to improvise

within strict limits and under specific

conditions. “I’m the only one who’s free

all the time!” he says. Sometimes dur-

Shabalala does not immediately produce

finished compositions. The ideas need to

be worked on, fleshed out, refined. And

though this work can be carried out at

any time, Shabalala attributes by far the

largest and most important part of it to

processes that occur while he is asleep.

“When I’m sleeping”, he says, “my spirit

does the work. Sometimes at night when

I’m sleeping,I will discover my wife shak-

ing me- ‘Hey what’s going on? Are you

singing now?’ So that’s why I say: When

my flesh is sleeping, it’s daytime in my

spirit.” When he awakes, he can recall

the dream. He then either makes notes

about it, or if it is vivid enough, he may

go directly to his group and teach them

what he has learned.

How does he compose the parts of

a song and choreograph the dance

steps? Shabalala composes each piece

entirely on his own, working it out and

singing all the various choral parts. His

own soloistic leading part, however, he

treats differently: this will be improvised,

once the group has learned the song.

Almost invariably, the last important

detail to be composed is the intricate

and characteristic choreography that

normally erupts in the cyclical final sec-

tion of a song. (11)

When this dance section is present

in Shabalala’s compositions, he takes

special care with it. A meaningful

match of music and dance has been a

real concern of his since his youth, and

became one of the topics addressed in

the dream visits of his celestial choir.

In any case, he finds that the task of

choreographing comes easily to him.

This is partly a matter of self-confidence:

Joseph knows he is an outstanding

dancer. The members of his group know

this too, and they proudly regard him,

he says, as their dance teacher.

17UMS 09-10

F U R T H E R R E S O U R C E SL A D Y S M I T H B L A C K M A M B A Z O

EXPLORE

WEB

LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO

www.mambazo.com

LISTEN

www.npr.org/templates/story/story.

php?storyId=93391815

Jazzset With Dee Dee Bridgewater: •

Ladysmith Black Mambazo And

Hugh Masekela: Carrying South

Africa

www.npr.org/templates/story/story.

php?storyId=1672483

Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Live In •

Studio 4a: Group Celebrates A De-

cade Of South African Freedom

www.npr.org/templates/story/story.

php?storyId=1186957&ps=rs

Musicians In Their Own Words: •

Joseph Shabalala

WATCH

Ladysmith Black Mambazo (2009) Live.

[DVD]. Heads up video.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo. (1999). In

Harmony. [DVD]. Gallo Record Company.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo. (1997). The

Best of [DVD]. Gallo Record Company.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo. (1988). Jour-

ney of Dreams. [DVD]. ILC Ltd.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo. (2004). On

Tiptoe: Gentle Steps to Freedom. [DVD].

New Video Group.

Paul Simon. (1997). Classic Albums -

Graceland. [DVD]. Harcourt Films/Isis

Productions

READ

NIGHTSONG

The Introduction to Veit Erlmann’s book

Nightsong was written by Shabalala and

first given as a speech at the University of

Cape Town. This introduction can be ac-

cessed for free at the Google books site

below. See pages 3-9.

Erlmann, Veit. Nightsong: Performance,

Power, and Practice in South Africa. Uni-

versity of Chicago Press, 1996.

18 UMS 09-10

A B O U T S O U T H A F R I C A

Ladysmith Townhall

19UMS 09-10

S O U T H A F R I C A

GEOGRAPHY

SOUTH AFRICA IS IN THE southern tip of Africa where, two great oceans meet, warm weather lasts most of the year, and big

game roams just beyond the city lights. This is where humanity began: fossilised footprints 80,000 years old and the world’s oldest

rock paintings can still be seen in South Africa.

Today, South Africa is the powerhouse of Africa, the most advanced, broad-based economy on the continent, with infrastructure

to match any first-world country. About two-thirds of Africa’s electricity is generated here. Around 40% percent of the continent’s

phones are here. Over half the world’s platinum and 10% of its gold is mined here. And almost everyone who visits is astonished at

how far a dollar, euro or pound will stretch.

Who lives in South Africa?

South Africa is a nation of over 47-mil-

lion people of diverse origins, cultures,

languages and beliefs. Around 79%

are black (or African), 9% white, 9%

«coloured» - the local label for people of

mixed African, Asian and white descent -

and 2.5% Indian or Asian. Just over half

the population live in the cities.

Two-thirds of South Africans are Chris-

tian, the largest church being the indig-

enous Zion Christian Church, followed

by the Dutch Reformed and Catholic

churches. Many churches combine Chris-

tian and traditional African beliefs, and

many non-Christians espouse these tra-

ditional beliefs. Other significant religions

–though with much smaller followings–

are Islam, Hinduism and Judaism.

What languages do people speak?

There are 11 officially recognised lan-

guages, most of them indigenous to

South Africa. Around 40% of the popu-

lation speak either isiZulu or isiXhosa.

You don’t speak either? If your English

is passable, don’t worry. Everywhere you

go, you can expect to find people who

speak or understand English.

English is the language of the cities, of

commerce and banking, of government,

of road signs and official documents.

Road signs and official forms are in Eng-

lish. The President makes his speeches in

English. At any hotel, the receptionists,

waiters and porters will speak English.

Another major language is Afrikaans, a

derivative of Dutch, which northern Euro-

peans will find surprisingly easy to follow.

Is South Africa a democracy?

South Africa is a vigorous multi-party

democracy with an independent judiciary

and a free and diverse press. One of the

world’s youngest - and most progres-

sive - constitutions protects both citizens

and visitors. You won’t be locked up for

shouting out your opinions, however

contrary. (But be careful about smoking

cigarettes in crowded restaurants!)

What about apartheid?

Up until 1994, South Africa was known

for apartheid, or white-minority rule. The

country’s remarkable ability to put cen-

turies of racial hatred behind it in favour

of reconciliation was widely considered

a social miracle, inspiring similar peace

efforts in places such as Northern Ireland

20 UMS 09-10

and Rwanda. Post-apartheid South Africa

has a government comprising all races,

and is often referred to as the rainbow

nation, a phrase coined by Nobel Peace

Prize winner Desmond Tutu.

What’s the weather like?

Summery, without being sweltering. In

Johannesburg, the country’s commer-

cial capital, the weather is mild all year

round, but can get cool at night. Durban,

the biggest port, is hot and sometimes

humid, a beach paradise. And in Cape

Town, where travellers flock to admire

one of the world’s most spectacular

settings, the weather is usually warm,

though temperamental. If you’re visit-

ing from the northern hemisphere, just

remember: when it’s winter over there,

it’s summer over here. Bring sunglasses

and sunscreen.

Is it a big country?

To a European, yes. The country straddles

1.2-million square kilometres, as big as

several European countries put together.

To an American, maybe not - it’s an

eighth the size of the US. Still, it’s more

than a day’s drive down the highway

from Johannesburg in the north to Cape

Town in the south (if you’re driving sensi-

bly), with the topography ranging across

the spectrum from lush green valleys to

semi-desert.

How is it divided up?

South Africa has nine provinces. Gau-

teng, the smallest and most densely pop-

ulated, adjoins Limpopo, North West and

Mpumalanga in the north. The Northern

Cape, the largest province with the small-

est population, is in the west. The Free

State is in the middle of the country. And

the coastal provinces of KwaZulu-Natal,

the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape

lie to the south.

What are the big cities?

South Africa has two capitals. Cape

Town, the oldest city, is the legislative

capital, where Parliament sits. Pretoria,

1 500 kilometres to the north, is the

executive capital, where the government

administration is housed. Next door to

Pretoria, and close enough that the outer

suburbs merge, is the commercial centre

of Johannesburg, once the world’s great-

est gold mining centre, now increasingly

dominated by modern financial and

service sectors. The second-biggest city

is Durban, a fast-growing port on the

eastern coast, and the supply route for

most goods to the interior.

Is it true that there are robots on the

street corners?

Yes, there are. In South Africa, traffic

lights are known as robots, although no

one knows why. A pick-up truck is a bak-

kie, sneakers are takkies, a barbeque

is a braai, an insect is a gogga and an

alchoholic drink ins a dop.

courtesy of: www.southafrica.info/

21UMS 09-10

S O U T H A F R I C A : A T I M E L I N EThe timeline that appears in this section is focused on events in the history of South Africa

and Apartheid with a few other relevant dates included.

HISTORY

1 6 5 2

Dutch settlers establish a colony on the

Cape of Good Hope, taking land from

indigenous tribes and bringing slaves

from Asia.

1 7 9 5

Great Britain takes control of the colony.

1 8 3 3

The British abolish slavery. Seeking

political freedom and new indigenous

laborers, the Dutch, or “Boers,” migrate

inland.

1 8 6 6

Diamonds discovered in Kimberly, South

Africa.

1 8 9 1

The Indian community, also suffering

under viciously racist treatment was

expelled from the Orange Free State

altogether.

1 8 9 2

Mahatma Ganfhi arrives in South Africa

as a young lawyer and goes on to be-

come a leading figure in Indian resistance

in South Africa.

1 9 1 0

ollowing a series of wars, the British

colonies and Boer republics merge into

the Union of South Africa, with shared

political power between the two white

groups.

1 9 1 1

The African National Congress (ANC)

forms to protect the rights of black South

Africans.

1 9 1 3

The Native Land Act limits property

ownership by blacks. “As against the Eu-

ropean the native stands as an eight year

old against a man of mature experience,”

argues Boer politician JBM Hertzog.

1 9 1 4

The Indian poll tax in Natal is removed

after a mass strike in which a number of

Indians were killed.

Mahatma Gandhi leaves the country.

1 9 1 8

One million black mine workers go on

strike for higher wages.

ANC constitution refers to ANC as a

“Pan African Assosiation.”

1 9 1 9

The Industrial and Commercial Workers’

Union of South Africa was formed.

1 9 3 4

South Africa becomes independent from

Great Britain.

1 9 4 4

The ANC Youth League was formed.

Nelson Mandela was its secretary.

1 9 4 8

The Boers’ National Party is elected to

power on a platform of systemized, legal-

ized racial segregation, or “apartheid.”

1 9 5 0

The Population Registration Act identifies

four racial classifications, in order of su-

periority: white, Asian, coloured (mixed

heritage) and black. The Group Areas

Act designates specific homelands for

each race, and hundreds of thousands of

blacks, coloureds and Asians are forcibly

relocated. Blacks, comprising over 70%

of the population, are restricted to 13%

of the land.

1 9 5 2

The Pass Laws Act requires blacks to carry

identification booklets at all times.

22 UMS 09-10

1 9 6 0

In the town of Sharpeville, white police

open fire on a group of black protesters

burning their pass books. To suppress fur-

ther resistance, The ANC and other black

political organizations are banned.

1 9 6 1

A wing of the ANC led by Nelson Man-

dela threatens violence as a last resort.

Mandela is arrested and imprisoned the

following year. “a democratic and free

society in which all persons live together

in harmony and with equal opportuni-

ties…is an ideal which I hope to live for

and to achieve,” Mandela tells the court.

“But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I

am prepared to die.”

South Africa became a republic and

leaves the Commonwealth.

1 9 6 2

The UN condemns South African apart-

heid policy and passes an arms embargo

the following year.

Madela was arrested and sentenced to a

three-year sentence for incitement.

1 9 6 3

In July a police raid on the Rivonia farm

Lilliesleaf led to the arrest of several of

Mandela’s senior ANC colleagues. Man-

dela was brought from prison to stand

trial with them. They were charged with

sabatoge.

1 9 6 4

Mandela and colleagues were all sen-

tenced to life in prison and taken to

Robben Island.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo is formed.

1 9 6 6

BJ Vorster became prime minister after

the assasignation of Verwoerd. Segrega-

tion became even more strictly enforced.

1 9 6 9

Realing under the blow of the “Rivonia

Trial,” the ANC continued to operate

regrouping at the Morogoro Confrence

in Tanzania

1 9 7 3

Ladysmith Black Mambazo released their

first album, Amabutho, which was the

first album by a black musician or group

in South Africa to receive gold status.

1 9 7 6

June 16, in the black township of Sowe-

to, students take to the streets to protest

forced tuition in Afrikaans; Police fired on

them. 575 people are killed.

1 9 8 5

As civil unrest increases and labor strikes

threaten the economy, Prime Minister

P.W. Botha declares a state of emergency

and implements martial law. Over the

next four years thousands of blacks are

killed and thousands more detained.

Media access is also restricted.

1 9 8 6

The collaboration of Paul Simon and

Ladysmith Black Mambazo produces the

album Graceland.

1 9 8 9

F.W. De Klerk succeeds Botha as Prime

Minister; in his opening address to Parlia-

ment, he announces a plan to desegre-

gate public facilities and unban the ANC.

1 9 9 0

F.W. de Klerk lifted restrictions on 30

oposition groups including the ANC.

After 27 years in prison, Nelson Mandela

is released. Meetings between De Klerk

and Mandela begin a four-year negotia-

tion process to abolish apartheid. “Today

we have closed the book on apartheid,”

De Klerk declares.

1 9 9 2

The white electorate of South Africa en-

dorsed de Klerk’s stance in a referendum

ending white minority rule.

1 9 9 4

South Africa holds its first democratic

election with universal suffrage; the

turnout is so substantial that voting lasts

three days. ANC leader Nelson Man-

dela is elected president and joins with

the National Party in a Government of

National Unity.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo sings at Nel-

son Mandela’s inaugaration ceremony

Sources: www.longwharf.org/off_homeTime.htmlwww.southafrica.infowww.sahistory.org.za

23UMS 09-10

T H E P R O V I N C E S

SOUTH AFRICA HAS nine provinces, each with its own government, landscape, population, economy and climate.

Before 1994, South Africa had four provinces: the Transvaal and Orange Free State, previously Boer republics, and Natal and the

Cape, once British colonies. Scattered about were also the grand apartheid “homelands”, spurious states to which black South

Africans were forced to have citizenship.

Under South Africa’s new democratic constitution, the four provinces were broken up into the current nine, and the “homelands”

blinked out of existence. The Cape became the Western Cape, Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and the western half of North West,

while the Transvaal became Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Gauteng and the eastern half of North West. Natal was renamed KwaZulu-Na-

tal, incorporating the “homeland” of KwaZulu, and the Orange Free State became simply the Free State. courtesy of: www.southafrica.info/

A map of South Africa before 1994, showing the original four provinces of the Cape, Or-ange Free State, Natal and Transvaal, as well as the grand apartheid “homelands” (Image: South African History Online

Map used with permission from: http//www.SA-Venues.com

GEOGRAPHY

24 UMS 09-10

P O P U L AT I O NSouth Africa is a nation of over 47-million people of diverse origins, cultures, languages and beliefs.

Courtesy of: www.southafrica.info

S O U T H A F R I C A’ S P O P U L AT I O N B Y R A C E

AFRICANS ARE IN the majority at just over 38-million, making up 79.6% of the total population. The white population is estimated at

4.3-million (9.1%), the coloured population at 4.2-million (8.9%) and the Indian/Asian population at just short of 1.2-million (2.5%).

While more than three-quarters of South Africa’s population is black African, this category is neither culturally nor linguistically ho-

mogenous. Africans include the Nguni people, comprising the Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele and Swazi; the Sotho-Tswana people, compris-

ing the Southern, Northern and Western Sotho (Tswana); the Tsonga; and the Venda.

GEOGRAPHY

*

25UMS 09-10

Khoisan is a term used to describe two separate groups, physically similar in being light-skinned and small in stature. The Khoi,

who were called Hottentots by the Europeans, were pastoralists and were effectively annihilated; the San, called Bushmen by the

Europeans, were hunter-gatherers. A small San population still lives in South Africa.

South Africa’s white population descends largely from the colonial immigrants of the late 17th, 18th and 19th centuries:Dutch,

German, French Huguenot and British. Linguistically, it is divided into Afrikaans- and English-speaking groups, although many small

communities that have immigrated over the last century retain the use of other languages.

The majority of South Africa’s Asian population is Indian in origin, many of them descended from indentured workers brought to

work on the sugar plantations of the eastern coastal area then known as Natal in the 19th century. They are largely English-speak-

ing, although many also retain the languages of their origins. There is also a significant group of Chinese South Africans.

*The label “coloured” is a contentious one, but still used for people of mixed race descended from slaves brought in from East

and central Africa, the indigenous Khoisan who lived in the Cape at the time, indigenous Africans and whites. The majority

speak Afrikaans.

S O U T H A F R I C A’ S P O P U L AT I O N B Y L A N G U A G E

Nine of the country’s 11 official languages are African, reflecting a variety of ethnic groupings which nonetheless have a great deal in common in terms of background, culture, and descent.

26 UMS 09-10

Zulu Warriors, Photo: Library of Congress

T H E Z U L U P E O P L E

ABOUT

ISIZULU IS THE LANGUAGE of South

Africa’s largest ethnic group, the Zulu

people, who take their name from the

chief who founded the royal line in the

16th century. The warrior king Shaka

raised the nation to prominence in the

early 19th century. The current monarch

is King Goodwill Zwelithini.

A tonal language and one of the coun-

try’s four Nguni languages, isiZulu is

closely related to isiXhosa. It is probably

the most widely understood African lan-

guage in South Africa, spoken from the

Cape to Zimbabwe but mainly concen-

trated in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

The writing of Zulu was started by mis-

sionaries in what was then Natal in the

19th century, with the first Zulu transla-

tion of the Bible produced in 1883. The

first work of isiZulu literature was Thomas

Mofolo’s classic novel Chaka, which was

completed in 1910 and published in 1925,

with the first English translation produced

in 1930. The book reinvents the legend-

ary Zulu king Shaka, portraying him as a

heroic but tragic figure, a monarch to rival

Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND BELIEFS

The Zulu language, of which there are

variations, is part of the Nguni language

group. The word Zulu means ‘Sky’ and

according to oral history, Zulu was the

name of the ancestor who founded the

Zulu royal line in about 1670. Today it is

estimated that there are more than forty-

five million South Africans, and the Zulu

people make up about approximately

22% of this number. The largest urban

concentration of Zulu people is in the

Gauteng Province, and in the corridor of

Pietermaritzburg and Durban. The largest

rural concentration of Zulu people is in

Kwa-Zulu Natal.

IsiZulu is South Africa’s most widely

spoken official language. It is a tonal

language understood by people from

the Cape to Zimbabwe and is charac-

terized by many ‘clicks’. In 2006 it was

determined that approximately nine

million South Africans speak Xhosa as a

home language

Its oral tradition is very rich but its

modern literature is still developing. J.L

Dube was the first Zulu writer (1832)

though his first publication, a Zulu story

was written in English titled ‘A Talk on

my Native Land’. In 1903, he concen-

trated on editing the newspaper ‘Ilanga

LaseNatali’. His first Zulu novel ‘Insila

kaShaka’ was published in 1930. We see

a steady growth of publications especially

novels from 1930 onwards’.

27UMS 09-10

The clear-cut distinction made today

between the Xhosa and the Zulu has no

basis in culture or history, but arises out

of the colonial distinction between the

Cape and Natal colonies. Both speak

very similar languages and share similar

customs, but the historical experiences

at the northern end of the Nguni culture

area differed considerably from the his-

torical experiences at the southern end.

The majority of northerners became part

of the Zulu kingdom, which abolished

circumcision. The majority of southern-

ers never became part of any strongly

centralised kingdom, intermarried with

Khoikhoi, and retained circumcision.

Many Zulu people converted to Christian-

ity under colonialism. Although there are

many Christian converts, ancestral beliefs

have not disappeared. There is now a

mixture of traditional beliefs and Chris-

tianity. Ancestral spirits are important

in Zulu religious life,and offerings and

sacrifices are made to the ancestors for

protection, good health, and happiness.

Ancestral spirits come back to the world

in the form of dreams, illnesses, and

sometimes snakes. The Zulu also believe

in the use of magic. Ill fortune such as

bad luck and illness is considered to be

sent by an angry spirit. When this hap-

pens, the help of a traditional healer is

sought, and he or she will communicate

with the ancestors, or use natural herbs

and prayers, to get rid of the problem.

The Zulu are fond of singing as well as

dancing. These activities promote unity

at all the transitional ceremonies such as

births, weddings, and funerals. All dances

are accompanied by drums and the

men dress as warriors . Zulu folklore is

transmitted through storytelling, praise-

poems, and proverbs. These explain

Zulu history and teach moral lessons.

Praise-poems (poems recited about the

kings and the high achievers in life) are

becoming part of popular culture. The

Zulu, especially those from rural areas,

are known for their weaving, craft-

making, pottery, and beadwork. The Zulu

term for “family” (umndeni) includes

all the people staying in a homestead

who are related to each other, either by

blood, marriage, or adoption. Drinking

and eating from the same plate was and

still is a sign of friendship. It is customary

for children to eat from the same dish,

usually a big basin. This derives from a

‘share what you have’ belief which is part

of ubuntu (humane) philosophy.

Source: www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmediaculture/cul-ture%20&%20heritage/cultural-groups/zulu.htm

ORIGINS Archaeological evidence

shows that the Bantu-speaking groups,

ancestors of the Nguni, migrated

down from East Africa as early as the

eleventh century.

Long ago, before the Zulu were forged

as a nation, they lived as isolated family

groups and partly nomadic northern

Nguni groups. These groups moved

about within their loosely defined

territories in search of game and

good grazing for their cattle. As they

accumulated livestock and supporters,

family leaders divided and dispersed in

different directions, while still retaining

family networks.

The Zulu homestead (imizi) consisted

of an extended family and others at-

tached to the household through social

obligations. This social unit was largely

self-sufficient, with responsibilities di-

vided according to gender. Men were

generally responsible for defending the

homestead, caring for cattle, manufac-

turing and maintaining weapons and

farm implements, and building dwellings.

Women had domestic responsibilities and

raised crops, usually grains, on land near

the household.

By the late eighteenth century, a process

of political consolidation among the

groups was beginning to take place. A

number of powerful chiefdoms began to

emerge and a transformation from pasto-

ral society to a more organised statehood

occurred. This enabled leaders to wield

more authority over their own sup-

porters, and to compel allegiance from

conquered chiefdoms. Changes took

place in the nature of political, social,

and economic links between chiefs of

these emerging power blocks and their

subjects. Zulu chiefs demanded steadily

increasing tribute or taxes from their sub-

jects, acquired great wealth, commanded

large armies, and, in many cases, subju-

gated neighbouring chiefdoms.

Military conquest allowed men to

achieve status distinctions that had

become increasingly important. This

culminated early in the nineteenth

century with the warrior-king Shaka

conquering all the groups in Zululand

and uniting them into a single powerful

Zulu nation, that made its influence felt

over southern and central Africa. Shaka

ruled from 1816 to 1828, when he was

assassinated by his brothers.

Shaka recruited young men from all over

the kingdom and trained them in his

own novel warrior tactics. His military

campaign resulted in widespread violence

and displacement, and after defeat-

ing competing armies and assimilating

their people, Shaka established his Zulu

nation. Within twelve years, he had

forged one of the mightiest empires the

African continent has ever known. The

28 UMS 09-10

Zulu empire weakened after Shaka’s

death in 1828.

Source: www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmediaculture/cul-ture%20&%20heritage/cultural-groups/zulu.htmcourtesy of: www.southafrica.info/

COLONIALISM AND APARTHEID One

of the most significant events in Zulu

history was the arrival of Europeans in

Natal. By the late 1800s, British troops had

invaded Zulu territory and divided Zulu

land into different chiefdoms. The Zulu

never regained their independence. Natal

received ‘Colonial government’ in 1893,

and the Zulu people were dissatisfied about

being governed by the Colony. A plague

of locusts devastated crops in Zululand and

Natal in 1894 and 1895, and their cattle

were dying of rinderpest, lung sickness,

and east coast fever. These natural disasters

impoverished them and forced more men

to seek employment as railway construc-

tion workers in northern Natal and on the

mines in the Witwatersrand.

The last Zulu uprising, led by Chief

Bambatha in 1906, was a response to

harsh and unjust laws and unimaginable

actions by the Natal Government. It was

sparked off by the imposition of the

1905 poll tax of £1 per head, introduced

to increase revenue and to force more

Zulus to start working for wages. The

uprising was ruthlessly suppressed.

The 1920s saw fundamental changes

in the Zulu nation. Many were drawn

towards the mines and fast-growing cit-

ies as wage earners, and were separated

from the land and urbanized. Zulu men

and women have made up a substantial

portion of South Africa’s urban work

force throughout the 20th century, espe-

cially in the gold and copper mines of the

Witwatersrand. Zulu workers organized

some of the first black labour unions in

the country. For example, the Zulu Wash-

ermen’s Guild, Amawasha, was active in

Natal and the Witwatersrand even before

the Union of South Africa was formed

in 1910. The Zululand Planters’ Union

organized agricultural workers in Natal in

the early twentieth century.

The dawn of apartheid in the 1940s

marked more changes for all Black South

Africans, and in 1953 the South African

Government introduced the “home-

lands”. In the 1960s the Government’s

objective was to form a “tribal authority”

and provide for the gradual development

of self-governing Bantu national units.

The first Territorial Authority for the Zulu

people was established in 1970 and the

Zulu homeland of KwaZulu was defined.

In March 1972, the first Legislative Assem-

bly of KwaZulu was constituted by South

African Parliamentary Proclamation.

The homeland of KwaZulu (or place of

the Zulu) was granted self-government

under apartheid in December 1977. Ac-

cording to the apartheid social planners

ideal of ‘separate development’ it was

intended to be the home of the Zulu

people. Although it was relatively large,

it was segmented and spread over a

large area in what is now the province of

KwaZulu-Natal.

Chief Mangosutho (Gatsha) Buthelezi, a

cousin of the king, was elected as Chief

Executive. The town of Nongoma was

temporarily consolidated as the capi-

tal, pending completion of buildings at

Ulundi. The 1970s also saw the revival of

Inkatha, later the Inkatha Freedom Party

(IFP), the ruling and sole party in the self-

governing KwaZulu homeland.

The capital of KwaZulu was Ulundi and

its government was led by Chief Man-

gosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Inkatha

Freedom Party (IFP), who established a

good relationship with the ruling National

Party. He also distanced himself from the

African National Congress (ANC), with

whom he had had a close relationship.

The government offered Buthelezi and

KwaZulu the status of fully ‘indepen-

dent homeland’ several times during the

1980s. He continually refused, saying he

wanted the approximately four million

residents of the homeland to remain

South African citizens. Nonetheless,

Buthelezi claimed chief ministerial privi-

leges and powers in the area.

Military prowess continued to be an

important value in Zulu culture, and this

emphasis fueled some of the political vio-

lence of the 1990s. Buthelezi’s nephew,

Goodwill Zwelithini, was the Zulu mon-

arch in the 1990s. Buthelezi and King

Goodwill won the agreement of ANC

negotiators just before the April 1994

elections that, with international media-

tion, the government would establish a

special status for the Zulu Kingdom after

the elections. Zulu leaders understood

this special status to mean some degree

of regional autonomy within the province

of KwaZulu-Natal.

In 1994, KwaZulu became a part of

South Africa when it merged with the

former Natal to become KwaZulu-Natal.

Sources: www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmediaculture/cul-ture%20&%20heritage/cultural-groups/zulu.htmwww.sahistory.org.za/pages/places/villages/kwazuluNatal/kzn.htm

29UMS 09-10

I L E M BH O N O R I N G S H A K A Z U L U

HISTORY

LADYSMITH BLACK MAMBAZO has re-

leased at least two records bearing Shaka

Zulu’s name: Shaka Zulu in 1987 and

Ilemb: Honoring Shaka Zulu in 2008.

With that in mind, it is worth looking at

the history of the warrior king.

One history of Shaka Zulu is available

online at www.sahistory.org.za/pages/

people/bios/zulu-shaka.htm.

The image of Shaka Zulu portrayed in this

account is of a brutal warrior who united

the Zulu nation through force and who

“accorded white traders most favored

treatment, ceded them land, and permit-

ted them to build a settlement at Port

Natal” (now Durban). This image, along

with the general history of Shaka Zulu,

is a disputed topic. For example, take a

look at the book Myth of Iron: Shaka

in History, by Dan Wylie, an academic at

South Africa’s Rhodes University.

Dr. Wylie described his book as an “anti-

biography” because the material for an

accurate biography did not exist. “There

is a great deal that we do not know, and

never will know,” he says.

Dr. Wylie argues that Shaka Zulu, the

19th-century warrior king dubbed Af-

rica’s Napoleon, was not the bloodthirsty

military genius of historical depiction

[…] His reputation for brutality was

concocted by biased colonial-era white

chroniclers and unreliable Zulu storytell-

ers who turned the man into a myth.

(source www.guardian.co.uk/world/2006/

may/22/rorycarroll.mainsection)

An 1824 Sketch of Shaka (1781-1828), the great Zulu king, four years before his death.By James King, it is the only known drawing of Shaka (Image: South African Government Online)

30 UMS 09-10

Although the history of Shaka Zulu

is disputed and his heroic status is

somewhat ambiguous, nevertheless,

Ladysmith Black Mambazo has chosen

to honor Shaka.

The ensemble’s official website offers

the following story in the promotion of

their album Ilemb: Honoring Shaka

Zulu (2008):

In the late 1700s, Shaka Zulu, a charis-

matic and cunning young warrior, united

the Zulus with various neighboring tribes

into a single powerful force that helped

give birth to a proud nation. Today, Sha-

ka Zulu is regarded as one of the greatest

leaders in African history. His combina-

tion of warrior discipline, visionary leader-

ship, innate creativity, and unshakable

belief in a united nation continues to

resonate to this day in South Africa. He

is revered as the single figure that gave

birth to the indomitable fighting spirit of

the Zulus – the same spirit that enabled

South Africans to persevere amid the

European domination of their homeland

for nearly two centuries of apartheid.

Ilembe: Honoring Shaka Zulu celebrates

not only Shaka Zulu but the sense

of perseverance, creativity and pride

that he has inspired in generations of

descendants. “He was a warrior, an

athlete, a singer, a dancer, a visionary,

he was so many things,” says Joseph

Shabalala,…“He was a diplomat too. He

could talk about differences in a civilized

way, but he was also very proud. If you

said, ‘No, I’m not going to cooperate,’

then he would say, ‘Alright, let us see

who is the boss.’”

Nearly two centuries after Shaka Zulu’s

passing the messages of peace, unity,

social harmony and national pride tran-

scend their points of origin and resonate

throughout the globe. “There have been

so many generations that have come and

gone since Shaka was king of the Zulus,

but there are still many hearts and minds

to be conquered,” says Shabalala, who

balances his spiritual convictions with his

cultural roots. “There are still many peo-

ple who need to be filled with the spirit

of unity and hope that Shaka embodied.

We are trying to remind people of the

importance of what this man did. That

was my purpose, to bring the people

back to the roots of their culture.”

Source www.mambazo.com/

31UMS 09-10

2004 NPR SPECIAL SOUTH AFRICA, 10

YEARS LATER

www.npr.org/news/specials/mandela/

This includes:

Legacy of the U.S. Anti-Apartheid •

Movement

South Africa’s Rocky Road to De-•

mocracy

South Africa: Truth and Reconcilia-•

tion

Cornel West Commentary: U.S.-•

South African Relations

Michael Eric Dyson Commentary: 10 •

Years After Apartheid

WEB

FRONTLINE: THE LONG WALK OF

NELSON MANDELA

www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/

shows/mandela/

MORE DETAILED HISOTRY TIMELINES

OF SOUTH AFRICA:

www.sahistory.org.za/pages/chronology/

chronology.htm

TIMELINE OF APARTHEID LEGISLA-

TION

www.sahistory.org.za/pages/chronology/

special-chrono/governance/apartheid-

legislation.html#1920

ART AND RESITANCE APARTEID

www.sahistory.org.za/pages/artsmedi-

aculture/protest_art/index.htm

SOUTH AFRICAN HISTORY ONLINE

www.sahistory.org.za/

U.S. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SA

COUNTRY STUDY

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/zatoc.html

F U R T H E R R E S O U R C E SS O U T H A F R I C A

EXPLORE

LISTEN

MANDELA: AN AUDIO HISTORY

www.radiodiaries.org/mandela/

A five-part radio series documenting the

struggle against apartheid through rare

sound recordings, including the voice

of Nelson Mandela himself. The series

includes:

A recording of the 1964 trial that •resulted in Mandela’s life sentence

A visit between Mandela and his •family secretly recorded by a prison

guard

Marching songs of guerilla soldiers•Government propaganda films•Pirate radio broadcasts from the •African National Congress

Interviews with former ANC activists, •National Party politicians, army gen-

erals, Robben Island prisoners, and

ordinary witnesses to history

32 UMS 09-10

A B O U T T H E M U S I C

33UMS 09-10

S O U T H A F R I C A N M U S I C

ABOUT

From the earliest colonial days until the present time, South African music has created itself out of the mingling of local ideas and forms with those imported from outside the country,

giving it all a special twist that carries with it the unmistakable flavor of the country.

BEGINNINGS In the Dutch colonial

era, from the 17th century on, indig-

enous tribes people and slaves imported

from the east adapted Western musical

instruments and ideas. The Khoi-Khoi,

for instance, developed the ramkie, a

guitar with three or four strings, based

on that of Malabar slaves, and used it to

blend Khoi and Western folk songs. The

mamokhorong was a single-string violin

that was used by the Khoi in their own

music-making and in the dances of the

colonial centre, Cape Town, which rapidly

became a melting pot of cultural influ-

ences from all over the world.

Western music was played by slave

orchestras (the governor of the Cape,

for instance, had his own slave orchestra

in the 1670s)and travelling musicians

of mixed-blood who moved around the

colony entertaining at dances and other

functions, a tradition that continued

into the era of British domination after

1806. In a style similar to that of British

marching military bands, coloured (mixed

race) bands of musicians began parading

through the streets of Cape Town in the

early 1820s, a tradition that was given

added impetus by the travelling min-

strel shows of the 1880s. The tradition

continues to the present day with the

great carnival held in Cape Town every

New Year.

MISSIONARIES AND CHOIRS The

penetration of missionaries into the inte-

rior of South Africa over the succeeding

centuries also had a profound influence

on the nation’s musical styles. In the late

1800s, early African composers such

as John Knox Bokwe began composing

hymns that drew on traditional Xhosa

harmonic patterns. In 1897, Enoch Son-

tonga, then a teacher, composed the

hymn “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” (God Bless

Africa), which was later adopted by the

liberation movement and ultimately be-

came the national anthem of democratic

South Africa.

The missionary influence, plus the later

influence of American spirituals, spurred

a gospel movement that is still very

strong in South Africa today. Drawing

on the traditions of churches such as

the Zion Christian Church, it has expo-

nents whose styles range from the more

traditional to the pop-infused sounds of,

for instance, former pop-singer Rebecca

Malope.

Gospel, in its many forms, is one of the

best-selling genres in South Africa today,

with artists who regularly achieve sales of

gold and platinum status. The missionary

emphasis on choirs, combined with the

traditional vocal music of South Africa,

and taking in other elements as well, also

gave rise to a mode of a capella singing

that blend the style of Western hymns

with indigenous harmonies. This tradition

is still alive today in the isicathamiya

form, of which Ladysmith Black Mam-

bazo are the foremost and most famous

exponents. This vocal music is the oldest

traditional music known in South Africa.

It was communal, accompanying dances

or other social gatherings, and involved

elaborate call-and-response patterns.

Though some instruments such as the

mouth bow were used, drums were

relatively unknown. Later, instruments

used in areas to the north of what is

now South Africa, such as the mbira or

thumb-piano from Zimbabwe, or drums

34 UMS 09-10

or xylophones from Mozambique, began

to find a place in the traditions of South

African music-making. Still later, Western

instruments such as the concertina or the

guitar were integrated into indigenous

musical styles, contributing, for instance,

to the Zulu mode of maskanda music.

The development of a black urban prole-

tariat and the movement of many black

workers to the mines in the 1800s meant

that differing regional traditional folk

musics met and began to flow into one

another. Western instrumentation was

used to adapt rural songs, which in turn

started to influence the development of

new hybrid modes of music-making (as

well as dances) in South Africa’s develop-

ing urban centers.

MINSTRELS In the mid-1800s, travelling

minstrel shows began to visit South Af-

rica. At first, as far as can be ascertained,

these minstrels were white performers in

“black face”, but by the 1860s genuine

black American minstrel troupes had be-

gun to tour the country, singing spirituals

of the American South and influencing

many South African groups to form

themselves into similar choirs.

Regular meetings and competitions be-

tween such choirs soon became popular,

forming an entire sub-culture unto itself

that continues to this day in South Africa.

This tradition of minstrelsy, joined with

other forms, also contributed to the

development of isicathamiya, which

had its first international hit in 1939 with

“Mbube.” This remarkable song by Solo-

mon Linda and the Evening Birds was an

adaption of a traditional Zulu melody, and

has been recycled and reworked innumer-

able times, most notably as Pete Seeger’s

hit “Wimoweh” and the international

classic “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.”