TWO AND T P NYU L R (2008) Victor Fleischer

Transcript of TWO AND T P NYU L R (2008) Victor Fleischer

Legal Studies Research Paper Series

Working Paper Number 06-27 March 2006

Revised May 4, 2007

TWO AND TWENTY:

TAXING PARTNERSHIP PROFITS IN PRIVATE EQUITY FUNDS

FORTHCOMING, NYU LAW REVIEW (2008)

Victor Fleischer

Associate Professor University of Colorado Law School

Associate Professor

University of Illinois College of Law (effective June 2007)

TWO AND TWENTY

2

TWO AND TWENTY: TAXING PARTNERSHIP PROFITS

IN PRIVATE EQUITY FUNDS

Victor Fleischer*

Private equity fund managers take a share of the profits of the

partnership as the equity portion of their compensation. The tax rules for compensating service partners create a planning opportunity for managers who receive the industry-standard “two and twenty” (a two percent management fee and twenty percent profits interest). By tak-ing a portion of their pay in the form of partnership profits, fund man-agers defer income derived from their labor efforts and convert it from ordinary income into long-term capital gain. This quirk in the tax law allows some of the richest workers in the country to pay tax on their labor income at a low rate. Changes in the investment world – the growth of private equity funds, the adoption of portable alpha strate-gies by institutional investors, and aggressive tax planning – suggest that reconsideration of the partnership profits puzzle is overdue. In this Article, I offer a menu of reform alternatives, including a novel cost-of-capital approach that would strike an appropriate balance be-tween treating returns on human capital as ordinary income and re-warding entrepreneurial activity with a tax subsidy.

* Associate Professor, University of Colorado Law School; Associate Professor, University of Illinois College of Law (effective June 2007). I am indebted to Alan Auerbach, Steve Bank, Deborah DeMott, Wayne Gazur, Bill Klein, Henry Ordower, Miranda Perry Fleischer, Alex Raskolnikov, Ted Seto, Dan Shaviro, Kirk Stark, Larry Zelenak, and Eric Zolt for their helpful comments and suggestions. I thank the participants at the 2006 Junior Tax Scholars Confer-ence, the Tax Section of the AALS 2006 Annual Meeting, the Agency & Partnership Section of the AALS 2007 Annual Meeting, the UCLA Tax Policy & Public Finance Colloquium, and the NYU Tax Policy & Public Finance Colloquium for their comments and suggestions.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction.........................................................................................................1 I. The Tax Treatment of Two and Twenty...................................................4 II. Why It Matters Now .................................................................................11 III. Deferral ......................................................................................................18

A. The Reluctance to Taxing Endowment..............................................19 B. Pooling of Labor and Capital Subsidy ................................................22 C. Measurement Concerns .........................................................................28

IV. Conversion.................................................................................................31 A. Below-Market Salary and Conversion................................................32 B. Compensating Service Partners............................................................33 C. The Entrepreneurial Risk Subsidy ......................................................35

V. Reform Alternatives...................................................................................38 A. The Status Quo.......................................................................................40 B. The Gergen Approach ..........................................................................41 C. The Forced Valuation Approach ........................................................42 D. The Cost-of-Capital Approach............................................................43 E. True Preferred Return Variation ........................................................45 F. Talent-Revealing Election....................................................................46 G. Summary.................................................................................................47

VI. Conclusion .................................................................................................48

TWO AND TWENTY

1

It’s like Moses brought down a third tablet from the Mount—and it said ‘2 and 20.’

— Christopher Ailman, California State Teachers’ Retirement System1

INTRODUCTION Private equity fund managers take a share of partnership

profits as the equity portion of their compensation. The industry standard package is “two and twenty.” The “two” refers to an annual management fee of two percent of the capital that investors have committed to the fund. The “twenty” refers to a twenty percent share of the future profits of the fund; this profits interest is also known as the “carry” or “carried interest.” The profits interest is what gives fund managers upside potential: If the fund does well, the managers share in the treasure. If the fund does badly, however, the manager can walk away. Any proceeds remaining at liquidation would be dis-tributed to the original investors, who hold the “capital interests” in the partnership.2

The tax rules treat partnership profits interests more favorably

than other forms of compensation, such as cash, stock, stock options, or a capital interest in a partnership. By getting paid in part with carry instead of cash, fund managers defer the income derived from their human capital. They are often also able to convert the character of that income from ordinary income into long-term capital gain, which is taxed at a lower rate. This conversion of labor income into capital gain is contrary to the general approach of the tax code, and it

1 As quoted in Neil Weinberg & Nathan Verdi, “Private Inequity,” FORBES, March 13, 2006. 2 For more general discussion on the financial structure of private equity and venture capital

funds, see Ulf Axelson, Per Stromberg & Michael Weisbach, Why are Buyouts Levered? The Financial Structure of Private Equity Funds (forthcoming, 2007 draft manuscript on file with the author); William A. Sahlman, The Structure and Governance of Venture Capital Organiza-tions, 27 J. FIN. ECON. 473 (1990).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

2

diverges from the treatment of other compensatory instruments. Partnership profits interests are treated more favorably than other economically similar methods of compensation, such as partnership capital interests, restricted stock, or at-the-money nonqualified stock options (the corporate equivalent of a partnership profits interest). The tax treatment of carry is roughly equivalent to that of Incentive Stock Options, or ISOs. Congress has limited ISO treatment to rela-tively modest amounts; the tax subsidy for partnership profits inter-ests is not similarly limited.3 A partnership profits interest is, under current law, the single most tax-efficient form of compensation avail-able without limitation to highly-paid executives.

The Article considers some possible law reform alternatives. I

have previously considered how the tax law may distort contract de-sign and the behavior of fund managers.4 Here, I focus on possible improvements in the tax law. One significant concern is the loss of ef-ficiency that occurs when investors and managers alter their contracts to provide compensation in a tax-advantaged form: Investors swal-low an increase in agency costs in order to allow fund managers to pay lower taxes, which in turn allows investors to pay less compensa-tion. Current law may also unnecessarily favor private investment funds, which are organized as partnerships, over investment banks and other financial intermediaries organized as corporations.5

Distributive justice is also a concern for those who believe in a

progressive or flat rate income tax system. This quirk in the partner-ship tax rules allows some of the richest workers in the country to pay tax on their labor income at a low effective rate. While the high pay of fund managers is well known, the tax gamesmanship is not. Changes in the investment world – the growth of private equity funds, the adoption of portable alpha strategies by institutional inves-tors, the increased capital gains preference, and more sophisticated tax planning – suggest that reconsideration of the partnership profits

3 Congress has limited ISO treatment to options on $100,000 worth of underlying stock, measured on the grant date, per employee per year. See § 422(d). The capital interests underly-ing the profits interests of fund managers, by comparison, generally range from $100 million to several billion dollars. A 20% profits interest is equivalent to an option on 20% of the fund; as-suming a modest fund size of $100 million and ten annual grants, the available incentive is about 20 times as large as would be allowed for corporate stock options under the ISO rules.

4 See Victor Fleischer, The Missing Preferred Return, 31 J. CORP. L. 77 (2005). 5 Private investment funds organize as partnerships or LLCs, rather than C Corporations, in

order to avoid paying an entity-level tax that would eat into investors’ returns.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

3

puzzle is overdue. Ironically, while the public and the media have focused on the “excessive” pay of public company CEOs, the evidence suggests that they are missing out on the real story. Almost nine times as many Wall Street managers earned over $100 million as public company CEOs; many of these top-earners on Wall Street are fund managers.6 And they pay tax on much of that income at a 15% rate, while the much-maligned public company CEOs, if nothing else, pay tax at a 35% rate on most of their income.

At the same time, populist outrage won’t necessarily lead us to

the right result from a tax policy perspective. The best tax policy de-sign depends on an exceedingly intricate and subtle set of considera-tions, including the extent to which one wishes to subsidize entrepre-neurial risk-taking, whether one believes the partnership tax rules are a sensible way to provide such a subsidy, one’s tolerance for complex rules, and on one’s willingness to tolerate the deadweight loss associ-ated with tax planning. Furthermore, increasing the tax rate on fund managers will encourage more of them, on the margins, to relocate operations overseas. This Article thus considers a menu of reform al-ternatives; the right answer depends on the relative weight that policy makers may choose to place on these various considerations. I do not take a strong position on which reform alternative is best. Instead, this Article illuminates what might make some alternatives more at-tractive than others.

This Article makes three principal contributions to the tax pol-

icy literature. First, it makes a practical contribution to the doctrinal tax literature by re-examining the partnership profits puzzle in the context of modern private equity finance. The tax policy implications of current law are quite different as applied in the real world of pri-vate equity – and the case for law reform is stronger – than one might think from reading the partnership tax rules in isolation, without con-sidering the institutional context in which they matter the most.

Second, this Article contributes to the broader tax policy litera-

ture by introducing a novel “cost-of-capital” approach to measuring the option value of equity. This approach approximates other eco-

6 See Steven N. Kaplan & Joshua Rauh, Wall Street and Main Street: What Contributes to the Rise in the Highest Incomes?, working paper available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=931280 .

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

4

nomically similar arrangements, curbing the planning opportunity created when tax-indifferent counterparties offer compensatory at-the-money or out-of-the-money options or option-like instruments to taxable service providers. It also disaggregates the timing and charac-ter issues in a useful way.

Third, the Article offers a critical assessment of “sweat equity”

as a rationale for the preferential tax treatment of a profits interest in a partnership. The capital gains preference for investment capital is normally justified as a subsidy for taking on market risk, reducing the lock-in effect, or making up for the failure to index gains for inflation. None of those traditional justifications for the capital gains preference adequately capture the essence of the problem here. This Article in-stead hones in on entrepreneurial risk subsidy as a possible justifica-tion for treating the option value of partnership equity received in ex-change for future services in a tax-advantaged manner. Somewhat surprisingly, however, the tax advantage from working for oneself comes primarily from the ability to invest in one’s own business using pre-tax dollars rather than from the capital gains preference. This tax advantage, I argue, follows inevitably from our sensible reluctance to tax unrealized human capital, or endowment.

The Article is organized as follows. Following this introduc-

tion, Part I sets the stage with an overview of how private equity funds are taxed. Part II explains why addressing the long-standing partnership profits puzzle is so important today. Part III analyzes de-ferral issues, while Part IV analyzes conversion issues. Part V, build-ing on this analysis, offers a menu of reform alternatives.

I. THE TAX TREATMENT OF TWO AND TWENTY In order to keep the length of this Article manageable, I offer

only a brief description of the organization of private investment funds before turning to the tax treatment of fund manager compensa-tion.7 Funds are organized as limited partnerships or limited liability

7 For a more general description, see Sahlman, supra note 2; Ronald J. Gilson, Engineering a Venture Capital Market: Lessons from the American Experience, 55 STAN. L. REV. 1067 (2003). For more on the tax considerations that affect the compensation arrangement between fund managers and investors, see Fleischer, The Missing Preferred Return, supra note 4; Victor

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

5

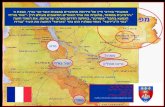

companies (LLCs) under state law. Investors become limited partners (LPs) in the partnerships and commit capital to the fund. A general partner (GP) manages the partnership in exchange for an annual management fee, often two percent of the fund’s committed capital. The GP also receives a share of any profits; this profit-sharing right is often called the “promote,” “carry,” or “carried interest.” The GP typi-cally receives twenty percent of the profits. The carried interest helps align the incentives of the GP with the goals of the LPs: because the GP can earn significant compensation if the fund performs well, the fund managers are driven to work harder and earn profits for the partnership as a whole. The GP also contributes some of its own capital to the fund so that it has some “skin in the game.” This amount ranges from one to five percent of the total amount in the fund.

GP

Private Equity Fund, L.P.

Limited Partners (LPs)

Portfolio Companies

Investment Professionals

Profits Interest Capital Interests

Management Fees

Fund Structure

Fleischer, The Rational Exuberance of Structuring Venture Capital Start-ups, 57 TAX L. REV. 137 (2004); Joseph Bankman, The Structure of Silicon Valley Start-Ups, 41 UCLA L. REV. 1737 (1994).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

6

After formation, the GP deploys the capital in the fund by investing in portfolio companies. In the case of venture capital funds, the portfolio companies are start-ups. In the case of private equity funds, the fund might buy out underperforming public companies, divisions of public companies, or privately-held businesses. After some period of time (often between two to seven years) the fund sells its interest in the portfolio company to a strategic or financial buyer, or takes it public and sells its securities in a secondary offering. The proceeds are then distributed to the partners, and when all the partnership’s invest-ments have been exited, the fund itself liquidates. The carried interest creates a powerful financial incentive for the GP. The GP is itself a partnership or LLC with a small number of professionals as members. The GP receives a management fee that covers administrative overhead, diligence and operating costs, and pays the managers’ salaries. The management fee is fixed and does not depend on the performance of the fund. The carry, on the other hand, is performance-based. Because private equity funds are leanly staffed, a carried interest worth millions of dollars may be split among just a handful of individuals. The tax treatment of a fund manager’s compensation depends on the form in which it is received. The management fee is treated as ordinary income to the GP, taken into income as it is received on an annual or quarterly basis. (As I discuss later, many fund managers take advantage of planning techniques to convert these tax-disadvantaged management fees into tax-advantaged carry.)

The treatment of carry is more complicated. When a GP re-ceives a profits interest in a partnership upon the formation of a fund, that receipt is not treated as a taxable event. This treatment seems counter-intuitive. There is little question that the GP receives some-thing of value at the moment the partnership agreement is signed. But valuation and other considerations prevent the tax law from treating this receipt as a taxable event. This creates a conceptual ten-sion. On the one hand, a carried interest is a valuable piece of prop-erty that often turns out to be worth millions and even hundreds of millions of dollars. On the other hand, it’s difficult to pin down a fair market value at the time of grant because the partnership interest is typically non-transferable, highly speculative, and depends on the ef-forts of the partners themselves (and thus would have a lower value

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

7

in the hands of an arms-length buyer). How should we treat this as-pect of the transaction for tax purposes? In the context of corporate equity compensation, section 83 puts executives to a choice: they may make a section 83(b) election and recognize income immediately on the current value of the prop-erty, or they can wait-and-see. If they make the election, any further gain or loss is capital gain or loss. If they wait-and-see, however, the character of the income is ordinary. From a revenue standpoint, the stakes of this choice are fairly low: any conversion or deferral of in-come, which lowers the executives’ tax bill, is roughly offset by the conversion or deferral of the corporate deduction for compensation paid.

The treatment of partnership equity is different than corpo-rate equity, and it’s not entirely consistent with these broad section 83 principles. The tax law tackles the problem of partnership equity by dividing partnership interests into two categories: capital interests and profits interests. A profits interest is an interest that gives the partner certain rights in the partnership (thus distinguishing it from an option to acquire a partnership interest) but has no current liquidation value. A capital interest gives the partner certain rights in the partnership and also has a positive current liquidation value. When a partner re-ceives a capital interest in a partnership in exchange for services, the partner has immediate taxable income on the value of the interest. Determining the proper treatment of a profits interest is more diffi-cult, however. It lacks any liquidation value, making its value diffi-cult to determine. This categorization is analytically convenient, but it is deceptively simple, somewhat inaccurate from an economic standpoint, and it creates planning opportunities that are widely ex-ploited.

Timing. A bit more explication of the tax background may be

helpful. The tax treatment of a profits interest in a partnership has been fairly consistent historically. There was a period of uncertainty following the 1971 case of Diamond vs. Commissioner, where the Tax Court (affirmed by the Seventh Circuit) held that the receipt of a prof-its interest “with determinable market value” is taxable income.8 A profits interest in a partnership rarely has a determinable market

8 See Diamond v. Commissioner, 492 F.2d 286, 291 (7th Cir. 1974), aff’g 56 T.C. 530 (1971).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

8

value, however; tax lawyers remained comfortable advising clients that the receipt of a profits interest was not normally a taxable event. The IRS later provided a safe harbor, in Revenue Procedure 93-27, for most partnership profits interests.9 The Treasury Department has proposed regulations (and an accompanying notice) that would reaffirm the status quo.10 The pro-posed regulations, like Rev. Proc. 93-27, require that, in order for the receipt of a profits interest to be treated as a non-taxable event, the partnership’s income stream cannot be substantially certain and pre-dictable, that the partnership cannot be publicly traded, and that the interest cannot be disposed of within two years of receipt. The typical carried interest finds ample shelter in the proposed regulations. The interest has no current liquidation value; if the fund were liquidated immediately, all of the drawn-down capital would be returned to the LPs. And while the carried interest has value, it is not related to a “substantially certain and predictable stream of income from partner-ship assets.” On the contrary, the amount of carry is uncertain and unpredictable.11 The receipt of a partnership interest, therefore, is not a taxable event under current law. The timing advantage continues as the partnership operates. The partnership holds securities in its portfolio companies; these securities are often illiquid and difficult to value. Like any other investor, the partnership then enjoys the benefit (or detriment) of the realization doctrine, which allows taxpayers to defer gain or loss until investments are actually sold (or until some other re-alization event occurs). One might think that the timing effect of the

9 See Rev. Proc. 93-27, 1993-2 C.B. 343. Rev. Proc. 93-27 spelled out the limits of this safe harbor. To qualify, the profits interest must not relate to a substantially certain and predictable stream of income from partnership assets, such as income from high-quality debt securities or a high-quality net lease, must not be disposed of within two years of receipt, and the partnership must not be publicly traded. See id. See also Rev. Proc. 2001-43, 2001-2 C.B. 191 (holding that a profits interest that is not substantially vested does trigger a taxable event when restrictions lapse; recipients need not file protective 83(b) elections). Rev. Proc. 93-27 defines a capital in-terest as an interest that would give the holder a share of the proceeds if the partnership’s assets were sold at fair market value and then the proceeds were distributed in a complete liquidation of the partnership. See Rev. Proc. 93-27, 1993-2 C.B. 343. A profits interest is defined as a partnership interest other than a capital interest. See id. The determination as to whether an interest is a capital interest is made at the time of receipt of the partnership interest. See id.

10 See 70 Fed. Reg. 29675 (May 24, 2005). 11 See Laura Cunningham, Taxing Partnership Interests Exchanged for Services, 47 TAX. L.

REV. 247, 252 (1991).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

9

realization doctrine would even out. Taxable losses are deferred, just as gains are. Because the GP receives a substantial share of the eco-nomic gains but only a small share of the fund’s losses (the one to five percent “skin in the game”), however, the realization doctrine works to the benefit of GPs.12 In sum, the tax law thus provides a timing benefit for GPs by allowing deferral on their compensation so long as the compensation is structured as a profits interest and not a capital interest in the partnership.13 Character. By treating the carried interest as investment in-come rather than service income, the tax law allows the character of realized gains to be treated as capital gain rather than ordinary in-come. Compensation for services normally gives rise to ordinary in-come. In the partnership context, characterizing a payment for ser-vices can be a difficult issue when the recipient, like the fund manager here, is a partner in the partnership. Section 83 provides the general rule that property received in connection with the performance of ser-vices is income.14 Section 707 addresses payments from a partnership to a partner. So long as the payment is made to the partner in its ca-pacity as a partner (and not as an employee) and is determined by ref-erence to the income of the partnership (i.e. is not guaranteed), then

12 The presence of tax-indifferent LP investors who don’t mind deferring tax losses makes this deferral much more significant from a revenue standpoint than it would otherwise be.

13 The net result is also more advantageous than parallel rules for executive compensation with corporate stock. As two commentators have explained, the valuation rules for corporate stock are more stringent.

The treatment of SP’s receipt of a profits interest under Rev. Proc. 93-27 is significantly better than the treatment of an employee’s receipt of corporate stock. While the economics of a prof-its interest can be approximated in the corporate context by giving investors preferred stock for most of their invested capital and selling investors and the employee "cheap" common stock, the employee will recognize OI under Code §83 equal to the excess of common stock’s FMV (not liquidation value) over the amount paid for such stock. In addition, if the common stock layer is too thin, there may be risk that value could be reallocated from the preferred stock to the common stock, creating additional OI for the employee.

William R. Welke & Olga A. Loy, Compensating the Service Partner with Partnership Equity: Code § 83 and Other Issues, 79 Taxes 94 (2001)

14 See § 83(a). If one assumes that a partnership profits interest is property, then a simple read-ing of § 83 suggests that the GP should be taxed immediately on the fair market value of the carried interest. It is far from clear, however, that Congress intended this reading when it en-acted § 83. Cite to legislative history from senate finance committee; Cunningham, supra note 11; New York State Bar Association, Tax Section, Report on the Proposed Regulations and Revenue Procedure Relating to Partnership Equity Transferred in Connection with the Per-formance of Services (October 26, 2005).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

10

the payment will be respected as a payout of a distributable share of partnership income rather than salary.15 In colloquial terms, if a ser-vice partner receives a cash salary and an at-the-money or out-of-the-money equity “kicker,” the kicker is treated as investment income, not labor income.

The tax law therefore treats the initial receipt of the carry as a non-event, and it then treats later distributions of cash or securities under the terms of the carried interest as it would any other distribut-able share of income from a partnership. Because partnerships are pass-through entities, the character of the income determined at the entity level is preserved as it is received by the partnership and dis-tributed to the partners. With the notable exception of hedge funds that actively trade securities, most private investment funds generate income by selling the securities of portfolio companies, which nor-mally gives rise to long-term capital gain.

The impact of these rules on the other partners varies from fund to fund. Treating the receipt of a profits interest by the GP as a non-event for tax purposes is good for the GP but bad for taxable LPs, as the partnership cannot take a deduction for the value of the interest paid to the GP, which in turn means that the LPs lose the benefit of that current deduction. If the GP and LPs have the same marginal tax rates, then the tax benefit to the GP is perfectly offset by the tax detriment to the LPs. As discussed in more detail below, how-ever, many LPs are tax-exempt. It is therefore rational for many funds to exploit the gap between the economics of the carried interest and its treatment for tax purposes.

In sum, a profits interest in a partnership is treated more like a

financial investment rather than payment for services rendered. Partnership profits are treated as a return on investment capital, not a return on human capital. In Parts III and IV, I explore why that is the case. Before turning to the justifications for deferral and conver-

15 Arguably, the initial receipt of the carried interest is better characterized as itself a guaran-teed payment (as it is made before the partnership shows any profit or loss). See Cunningham, supra note 11, at 267 (“Because the value of a partnership interest received by a service partner, whether capital or profits, invariably is dependent upon the anticipated income of the partner-ship, the mere fact that the right to reversion of the capital has been stripped from the interest does not convert the property interest represented by the profits interest into a distributive share of partnership income.”)

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

11

sion, however, it is worth highlighting why this issue is worthy of at-tention.

II. WHY IT MATTERS NOW

The scholarly literature on the tax treatment of a profits inter-

est in a partnership is extensive.16 The debate sometimes has the air of an academic parlor game. Setting aside a couple of hiccups – the Diamond and Campbell cases familiar to partnership tax jocks – three generations of tax lawyers have been perfectly comfortable advising their clients that the grant of a profits interest in a partnership does not give rise to immediate taxable income.17 The Treasury Depart-ment’s proposed regulations would quasi-codify this longstanding rule. Why reopen the debate? I argue here that that the increased use of partnership profits as a method of executive compensation in the context of private investment funds suggests the need for reform. The investment world has changed since the days when mortgage broker Sol Diamond sold his partnership interest for $40,000.

The key development has been the growth and professionali-

zation of the private equity industry. The private equity revolution has shaped the source of investment capital, spurred an increase in demand for the services of intermediaries, and allowed portable alpha strategies (defined and discussed below) to develop. These institu-tional changes have put increasing pressure on the partnership tax rules, which were designed with small businesses in mind. Games-manship has increased. Meanwhile, congressional policy towards ex-ecutive compensation in the corporate arena tightened up following the Enron scandals; the gap between the treatment of corporate eq-uity and partnership equity is increasing and, if not addressed, will

16 See, e.g., Cunningham, supra note 11; Leo Schmolka, Taxing Partnership Interests Ex-changed for Services: Let Diamond/Campbell Quietly Die, 47 TAX L. REV. 287 (1991); Martin B. Cowan, Receipt of an Interest in Partnership Profits in Consideration for Services: The Diamond Case, 27 TAX L. REV. 161 (1972); Hortenstine & Ford, Receipt of a Partnership Inter-est for Services: A Controversy That Will Not Die, 65 TAXES 880 (1987); Sheldon Banoff, Con-versions of Services Into Property Interests: Choice of Form of Business, 61 TAXES 844 (1983).

17 Subchapter K was enacted in 1954. Even before then, under common law rules, a profits interest was treated at least as favorably as it us under current law. See NYSBA report, supra note 14.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

12

encourage even more capital to shift from the public markets into pri-vate equity.

Source of Investment Capital. The first factor that warrants reconsideration of the partnership profits puzzle is the change in pri-vate equity’s source of investment capital. In the 1950s and 1960s, the private equity industry was populated mostly by individuals. The industry had a maverick culture. It attracted risk-seeking investment cowboys. Today, by contrast, even the most stolid institutional inves-tors include alternative assets like venture capital funds, private eq-uity funds, and hedge funds in their portfolios. The most powerful investors, such as large public pension funds and university endow-ments, may invest as much as half of their portfolio in alternative as-sets.18

This shift in the source of investment capital creates some tax

planning opportunities. Large institutional investors are long-term investors, which creates an appetite for illiquid investments like pri-vate equity that offer an illiquidity premium. The lengthy time hori-zon of these investments increases the value of deferring compensa-tion for tax purposes. More importantly, many of these institutional investors are tax-exempt, such as pension funds and university en-dowments. Substitute taxation is not available as a backstop to pre-vent exploitation of gaps in the tax base created by the realization doctrine and conversion of ordinary income into capital gain.19

Increased use of intermediaries. The second factor that war-

rants reconsideration of the partnership profits puzzle is the increased

18 The shift began with modern portfolio theory and accelerated with the Department of La-bor’s “prudent man” ruling in 1979, which allowed institutional investors to include high-risk, high-return investments as a part of a diversified portfolio.

19 In the corporate context, substitute taxation is essential to bringing the tax treatment of de-ferred compensation close to the economics of the arrangement. Consider your typical corpo-rate executive who receives non-qualified stock options. Those stock options have economic value when they are received, yet the executive defers recognition until the options vest. This deferral is valuable to the executive. But it is costly to the employer, which must defer the cor-responding deduction. Thus corporate equity compensation is not enormously tax-advantaged in the usual case. Corporate equity compensation is tax-advantaged if the corporation shorts its own stock to hedge the future obligation, or if the executive’s marginal tax rate is higher than the corporation’s marginal tax rate. See David I. Walker, Is Equity Compensation Tax-Advantaged?, 84 B. U. L. REV. 695 (2004); Merton H. Miller & Myron S. Scholes, Executive Compensation, Taxes and Incentives (1982); see also Gregg Polsky & Ethan Yale, Reforming the Taxation of Deferred Compensation, N.C. L. REV. (forthcoming 2007).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

13

use of intermediaries. As the industry has professionalized, the de-mand for private equity has increased. Smaller institutions, family of-fices, and high net worth individuals now seek access to the industry. Funds-of-funds and consultants have stepped in to provide these ser-vices. In addition to providing increased access to funds, these inter-mediaries screen funds to find the best opportunities and monitor the behavior of GPs in the underlying funds. In exchange, they often re-ceive a share of the profits – a carried interest of their own.20 Each year, more and more financial intermediaries take advantage of the tax treatment of two and twenty.

Portable Alpha. The third factor that warrants reconsidera-

tion of the partnership profits puzzle is the pursuit of a new invest-ment strategy by institutional investors. Tax scholars have generally discussed the partnership profits puzzle in the context of small busi-nesses and real estate partnerships. But the issue arises perhaps most often, and certainly with greatest consequence, for private investment funds.21 Thanks to recent growth in the industry, these funds now manage more than a trillion dollars of investment capital.22 Because of economies of scale, one might expect to see a small increase in abso-lute compensation but a decrease in proportion to the size of the fund. Instead, “two and twenty” has remained the industry standard.23 Something is fueling demand for the services that private equity fund managers provide.

20 Private investment funds (including most funds-of-funds) are engineered to be exempt from the Investment Company Act of 1940. As a result, the fund managers may be compensated by receiving a share of the profits from the fund. In contrast, mutual fund managers may not re-ceive a share of the profits, but rather must be paid a percentage of the assets of the fund (like the management fee in a private equity fund). As capital shifts away from mutual funds into private investment funds, more compensation takes the form of tax-advantaged carry, and less takes the form of tax-disadvantaged management fees.

21 See NYSBA Report, supra note 14. 22 See Axelson et al., supra note 2, at 2. Discussing the problem in the context of the Diamond

and Campbell cases is like drafting stock dividend rules to accommodate Myrtle Macomber. See Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920). Human stories and judicial opinions make the problem more accessible for students and scholars, but they can also distort public policy con-siderations. See also Growing Pains, in Special Report: Hedge Funds, THE ECONOMIST, March 4, 2006, at 63, 64 (“There are more than 8,000 hedge funds today, with more than $1 tril-lion of assets under management.”) Between hedge funds, private equity funds, and venture capital funds, the amount of investment capital flowing through the two and twenty structure easily exceeds two trillion dollars.

23 In larger funds one does tend to observe a lower management fee.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

14

The growing adoption of “portable alpha” strategies among

institutional investors helps explain the increased demand for the ser-vices of private investment fund managers, which in turn increases the dollar amount of compensation they receive.24 Portable alpha is an investment strategy that emphasizes seeking positive, risk-adjusted returns (alpha) rather than simply managing risk through portfolio al-location. Modern portfolio theory, in its simplest form, cautions in-vestors to maintain a diversified mix of stock, bonds, and cash. Only a small amount of assets would be placed in risky alternative asset classes like real estate, venture capital, buyout funds and hedge funds. According to portable alpha proponents, many investors fool them-selves into thinking that because they achieve high absolute returns, they are doing well. In reality, most of the return simply reflects a re-turn for bearing market risk (beta). What many investors have amounts to little more than an expensive index fund. A portable al-pha strategy, by contrast, recognizes that the real value comes from risk-adjusted returns. When alpha opportunities arise, they should be exploited fully; the remainder of the portfolio can be cheaply adjusted, using derivatives, to increase or decrease beta. (The availability of ad-justing beta through the use of derivatives is what makes the alpha “portable.”)25

Regulatory Gamesmanship. The fourth factor which makes

reconsideration of current law more pressing is the increase in regula-tory gamesmanship. Many investment funds exploit the tax treat-ment of a profits interest in a partnership by failing to index the measurement of profits to an interest rate or other reflection of the cost of capital. This phenomenon, which I call the “missing preferred return,” allows fund managers to maximize the present value of the carried interest and accept lower management fees than they other-wise would, thereby maximizing the tax advantage.26

24 One might ask why, if demand is increasing, supply does not follow. It does, of course – there are more fund managers than there used to be – but because it takes some time to develop a reputation, there is a lag. See Douglas Cumming & Jeffrey Macintosh, Boom, Bust & Litiga-tion in Venture Capital Finance, 40 WILLAMETTE L. REV. 867 (2004).

25 Alpha requires two inputs; the talent of the managers who can create it, and the capital of investors to implement the strategy. The two parties share the expected returns; investors are quite rationally willing to share large amounts of the abnormal returns with the fund managers who create them.

26 See Fleischer, The Missing Preferred Return, supra note 4. Buyout funds and many hedge funds use a hurdle rate, which also increases tax savings compared to a true preferred return.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

15

Buyout funds and most other investment funds use a form of

preferred return. Rather than a true preferred return, however, most use a hurdle rate. Until a fund clears a hurdle of, say, 8%, any profits are allocated to the LPs. Once the hurdle is cleared, profits are then allocated disproportionately to the GP until it catches up to the point where it would have been had it received twenty percent of the profits from the first dollar. Moral hazard concerns prevent private equity funds from doing away with the preferred return entirely. Still, by us-ing a hurdle rate – also known as a disappearing preferred return – rather than a true preferred return, profits interests are larger than they would otherwise be, raising the stakes on the tax question.27

Conversion of management fees into capital gain. GPs have

become more aggressive in converting management fees, which give rise to ordinary income, into additional carry. This planning strategy defers income and may ultimately convert labor income into capital gain. Some GPs opt to reduce the management fee in exchange for an enhanced allocation of fund profits. The choice may be made up front, triggered upon certain conditions, during formation of the fund; in other cases the GP may reserve the right to periodically waive the management fee in exchange for an enhanced allocation of fund prof-its during the next fiscal year of the fund.28

There is a trade-off between tax risk and entrepreneurial risk. So long as there is some economic risk that the GP may not receive sufficient allocations of future profit to make up for the foregone management fee, most practitioners believe that the constructive re-ceipt doctrine will not apply, and future distributions will be re-spected as distributions out of partnership profits.29

27 Whether the design of the preferred return is explained by tax motivations is a question I take up elsewhere. Regardless of whether the design is tax-motivated, there is no question that GPs are maximizing the amount of compensation they receive in carried interest. Nor is there any question that (with the exception of certain hedge funds) distributions typically give rise to long-term capital gain. Thus, even if one thinks that tax somehow has no influence on the design of preferred returns, the tax consequences raise considerations of distributional equity. A large amount of profits allocated to GPs represents the time value of money, received in exchange for services, yet it is treated as a risky investment return and afforded capital gains treatment.

28 See Jack S. Levin, STRUCTURING VENTURE CAPITAL, PRIVATE EQUITY, AND ENTREPRE-

NEURIAL TRANSACTIONS at 10-13 (2004 ed.). 29 See id. at 10-13; see also Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, Converting Management Fees

in Carried Interest: Tax Benefits vs. Economic Risks (2001) (on file with the author).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

16

The entrepreneurial risk may be smaller than it appears at first glance, depending on the underlying portfolio of the fund. If the management fee is waived in favor an increased profit share in the following year, and the GP knows that an investment will be realized that is likely to generate sufficient profits, then the constructive receipt doctrine should arguably apply. To my knowledge, however, there is no published authority providing guidance as to how much economic risk justifies deferral in this context.30

Lastly, GPs also take advantage of the current tax rules by converting management fees into capital interests. Recall that GPs are expected to have some “skin in the game” in the form of their own capital contributed to the fund. This gives GPs some downside risk and partially counterbalances the risk-seeking incentive that the car-ried interest provides. Rather than contribute after-tax dollars, how-ever, GPs again convert management fees into investment capital. In a technique known as a “cashless capital contribution,” GPs forego a portion of the management fee that would be otherwise due, using this cash to fund the GP capital account. This arrangement slightly increases agency costs (as it reduces the downside risk in the initial years of the fund), but the tax savings more than offset the increase in agency costs. (The tax savings can effectively be shared with the LPs by reducing management fees slightly.)

Distortion of investment behavior. Lastly, the problem war-

rants renewed attention because the treatment of a profits interest in a partnership represents a striking departure from the broader design of executive compensation tax policy. Economically similar transactions are taxed differently. Investors structure deals to take advantage of the different tax treatment. Generally speaking, this sort of tax plan-ning is thought to decrease social welfare by creating deadweight loss, that is, the loss created by inefficient allocation of resources. Specifi-cally, the tax-advantaged nature of partnership profits interests may encourage more investments to take place through private investment funds, which are taxed as partnerships, rather than through publicly-traded entities, which are generally taxed as corporations.31

30 Cf. Notice 2005-1 (discussing non-application of 409A to profits interest in a partnership). 31 As I discuss in more detail later, there may be offsetting positive social externalities that

may justify the disparate treatment of partnership equity. As an initial matter, however, it is

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

17

Section 83 is the cornerstone of tax policy regarding executive

compensation. Broadly speaking, § 83 requires that property received in exchange for services be treated as ordinary income. When an ex-ecutive performs services in exchange for an unfunded, unsecured promise to pay, or when she receives property that is difficult to value because of vesting requirements, compensation may be deferred. When compensation is received, however, the full amount must be treated as ordinary income. The treatment of partnership profits in-terests departs from this basic framework.

The clearest way to understand the point is to compare the

treatment of a partnership profits interest to a nonqualified stock op-tion (NQSO). When an executive exercises an option and sells the stock, she recognizes ordinary income to the extent that the market price of the stock exceeds the strike price. By contrast, a fund man-ager’s distributions are typically taxed at capital gains rates. A profits interest, in other words, is treated not like its economic sibling, an NQSO, but is instead treated in the executive’s hands like an Incen-tive Stock Option (ISO). ISOs are subject to a $100,000 per year limi-tation, reflecting a Congressional intent to limit the subsidy. Carried interests, by contrast, are not subject to any limitation.

The disparity between the treatment of corporate and part-

nership equity has grown recently. Section 409A, enacted in response to deferred compensation abuses associated with the Enron scandals, has forced more honest valuations of grants of common stock. Regu-lations under § 409A, however, exempt the grant of a profits interest in a partnership from similar scrutiny. As explained in more detail in Appendix A, this disparity in tax treatment gives rise to deadweight loss, although the distortion may not be as severe as one might think at first glance.32 [N.B. I’m still revising Appendix A, which isn’t yet attached. It shows that the disparity in tax treatment is most impor-

useful to describe the disparity before exploring whether the distortions that follow might none-theless be justified on policy grounds.

32 Some evidence of distortions of the market may be found in the behavior of the key market

participants. In response to labor market pressures, investment banks (which are mostly or-ganized as corporations) have begun to set up “side” funds to allow their fund managers to re-ceive a profits interest in funds that invest in portfolio companies so that they, too, can benefit from the tax treatment of two and twenty. See Berg & Serebransky. The investment bank still receives some fees, but the human capital provided by its employees is taxed at a lower rate.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

18

tant when portfolio companies have low effective tax rates, as with most venture capital-backed start-ups and many under-performing or debt-laden companies acquired by buyout shops. For companies with high effective tax rates, the ability to deduct managerial compensation is more valuable, which makes the corporate form more attractive.]

Summary. Together these institutional factors have contrib-

uted to an important but largely overlooked shift in executive com-pensation strategy in the financial services industry. The most tal-ented financial minds among us – those whose status is measured by whether they are “airplane rich” – are increasingly leaving investment banks and other corporate employers to start or join private invest-ment funds organized as partnerships.33 The partnership profits puz-zle has greater significance than ever before, and while this fact is well known within the private equity industry, it has received little atten-tion from academics or policymakers.34

III. DEFERRAL The concept that a fund manager can receive a profits interest in a partnership without facing immediate tax on the grant may not sit well with one’s intuitive sense of fair play. These profits interests have enormous economic value. Tax Notes columnist Lee Sheppard characterizes Treasury’s proposed regulations as a “massive give-away.”35

But the question is more complicated than it might seem at

first glance. Historically there has been broad agreement among tax scholars that deferral is appropriate for a profits interest received in exchange for future services. The underlying principles in support of deferral are (1) a philosophical resistance to taxing endowment and/or taxing unrealized human capital, (2) a subsidy for the pooling of labor

33 You are airplane rich if you own your own private jet. 34 The issue attracted attention on Capitol Hill and in the media while this paper was circulat-

ing in draft form. See Editorial, “Taxing Private Equity,” NEW YORK TIMES, April 2, 2007 (cit-ing this paper as “[a]dding grist to lawmakers’ skepticism,” notably Senator Max Baucus, the Democratic chairman of the Finance Committee, and Senator Charles Grassley, the commit-tee’s top Republican).

35 Cite to Tax Notes, March 2006.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

19

and capital, and (3) measurement/valuation concerns. The objections to taxing endowment are easily dealt with by considering accrual taxation alternatives. Encouraging the partnership form as a conven-ient method of pooling together labor and capital is somewhat more appealing as a justification for current law, although the normative underpinning for such a subsidy is unclear. Nor is it self-evident that such a subsidy, if desirable, should be extended to large investment partnerships. Measurement concerns are certainly valid; I offer a novel method for dealing with such concerns in part C below.

A. The Reluctance to Taxing Endowment

The deferral of income associated with the receipt of a profits

interest is sometimes explained by the same objections that scholars have toward taxing endowment. Endowment taxation calls for tax-ing people based on their ability or talent. A pure endowment tax base would tax both realized and unrealized human capital.

The primary attraction of using endowment as an ideal tax

base is that by taxing ability rather than earned income, it eliminates the incentive problem created by the fact that utility derived from lei-sure activities is untaxed. Endowment taxation reduces or eliminates the labor-leisure tax distortion and the deadweight loss that comes with it. Endowment taxation would, for example, eliminate the tax advantage of the currently untaxed psychological, status, and identity benefits of being a law professor – such as the intellectual stimulation of the job, the joy of teaching, academic freedom, and lifetime job se-curity. On the margins, an endowment tax scheme would encourage workers to labor in the sector which the market compensation is high-est, which in turn allocates labor resources more efficiently, reducing deadweight loss.

Using endowment as a tax base can give rise to a so-called

“talent slavery” objection. In a pure endowment tax system, a tal-ented lawyer graduating from Columbia Law School would be taxed on her anticipated future profits at a Wall Street law firm. She would have to pay this tax even if she quits law firm practice to become a law professor or work for a charitable organization – after all, the tax is based on one’s ability to earn income, not one’s actual earned in-come.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

20

Few tax scholars (if any) support a pure system of taxing en-

dowment.36 There are powerful liberal egalitarian objections to tax-ing endowment, mostly rooted in the talent-slavery objection. Equal-ity of opportunity is important, but so too is the autonomy of the most talented among us.37 Human beings were not created simply to cre-ate wealth or even simply to maximize personal or social utility; the government should play only a limited role in dictating the path they choose to follow.

These liberal egalitarian objections to endowment taxation

help explain why we do not tax a profits interest in a partnership re-ceived in exchange for future services. In the partnership profits tax literature, which predates the recent revival of academic interest in endowment taxation, the concern is articulated as an objection to tax-ing unrealized human capital. Professor Rebecca Rudnick character-ized the principle of taxing human capital only as income is realized as one of the four fundamental premises of partnership tax.38 “Hu-man capital,” she noted, “is not normally taxed on its expectancy value.”39 It’s unfair to tax someone today on what they have the abil-ity to do tomorrow; taxing human capital on its expected value com-modifies human capital by treating it like investment capital. It may provide a more accurate assessment of the value of human capital (and thus, arguably, a sounder tax base) but carries a high perceived cost.

Similarly, Professor Mark Gergen has argued that taxing un-

realized human capital is inconsistent with our system of income taxa-tion. “No one thinks, for example, that a person making partner in a

36 See generally Lawrence Zelenak, Taxing Endowment, 55 DUKE L. J. 1145 (2006). See also Daniel Shaviro, Endowment and Inequality, in TAX JUSTICE: THE ONGOING DEBATE (Thorndike & Ventry eds., 2002); Kirk J. Stark, Enslaving the Beachcomber: Some Thoughts on the Liberty Objections to Endowment Taxation, 18 CANADIAN J. L. & JURIS. 47 (2005); David Hasen, Liberalism and Ability Taxation, (forthcoming); Linda Sugin, Why Endowment Taxa-tion is Unjust (2007 draft manuscript on file with the author).

37 See, e.g., Liam Murphy & Thomas Nagel, THE MYTH OF OWNERSHIP: TAXES AND JUSTICE 123 (2002); John Rawls, JUSTICE AS FAIRNESS: A RESTATEMENT 158 (2001); David Hasen, The Illiberality of Human Endowment Taxation (draft manuscript).

38 See Rebecca S. Rudnick, Enforcing the Fundamental Premises of Partnership Taxation, 22 HOFSTRA L. REV. 229, 232-33 (1993) (“The four major premises of Subchapter K state that … (3) human capital providers are not taxed on the receipt of interests in profits if they are of merely speculative value[.]”)

39 See id. at 350.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

21

law firm should pay tax at that time on the discounted present value of her future earnings.”40 Professor Gergen acknowledges that the profits interest puzzle can be more complicated than the simple anal-ogy to a law firm associate making partner, and he identifies weak-nesses in the usual arguments about taxing human capital. In the end, however, he concludes that equity holds up the bottommost tur-tle.41 “Perhaps we cross over a line,” he explains, “where valuation or other problems are sufficiently difficult that wealth in the form of human capital cannot be taxed in most cases, and so, for the sake of equity, we choose to tax it in no cases.”

Professor Gergen’s objections to taxing unrealized human

capital are more pragmatic than normative. He emphasizes the im-portance of consistency, and so would draw a bright line between the exchange of cash in exchange for future services (which he would treat as a taxable event) and any other form of property, including a profits interest, which he would not. “Whatever the reason, the real-ity is that we do not tax human capital, and, unless we want to radi-cally change the tax, consistency requires that we not tax rights short of cash given in anticipation of future services.”42 Professor Gergen’s approach, while elegant and practical, creates its own inconsistencies, namely by treating economic equivalents differently.

The accrual tax alternative. The parade of horribles associ-ated with taxing endowment should not be used to justify a blanket

40 Mark Gergen, Pooling or Exchange: The Taxation of Joint Ventures Between Labor and Capital, 44 TAX L. REV. 519, 544 (1989).

41 See Stephen Hawking, A BRIEF HISTORY OF TIME, describing an anecdote about an en-counter between a scientist and a little old lady:

A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lec-ture on astronomy. He described how the Earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the centre of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, "What is the tortoise standing on?" "You're very clever, young man, very clever," said the old lady. "But it's turtles all the way down!"

42 Gergen, Pooling, supra note 40, at 550.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

22

rule that does not tax unrealized human capital. Accrual-based in-come taxation may serve as an attractive middle ground between en-dowment taxation and transaction-based income taxation. Even if we don’t want to tax human capital on its expectancy value, we may want to approximate the current value of returns on human capital as they accrue, rather than waiting until those returns are actually real-ized in the form of cash.

Because accrual income taxation taxes partners only so long as

they remain in their chosen profession, it avoids the “talent slavery” or “enslaving the beachcomber” objections to endowment taxation. Elite lawyers could still work for the Southern Center for Human Rights if they so choose. A Harvard MBA would not be forced to toil away at a private equity fund in order to pay off a tax imposed on her ability to perform the work. But once she chooses the path of riches, there is nothing normatively objectionable about taxing the returns from her human capital on an annual basis rather than on a transac-tional basis (i.e. whenever the partnership liquidates investments).43 One might object to the added complexity of accrual-based taxation of partnership profits, of course, but it suffices at this stage of the ar-gument to note that talent-slavery is a red herring.

B. Pooling of Labor and Capital Subsidy

It is often said that the appeal of the partnership form is its

convenience as a method of pooling together labor and capital. The corporate form can be rigid, for example, by demanding one class of stock (if organized as an S Corporation), or extracting an entity-level tax on profits (if organized as a C Corporation). The corporate form is said to be like a lobster pot: easy to enter, difficult to live in, and pain-ful to get out of.44 The partnership form, on the other hand, allows considerable flexibility to enter and exit without incurring an extra taxable recognition event.

43 The concern about taxing unrealized human capital could also be addressed through a spe-cial surtax on income at the point of realization.

44 See Peracchi v. Commissioner, 143 F.3d 487 (9th Cir. 1998), citing Boris I. Bittker & James Eustice, FEDERAL INCOME TAXATION OF CORPORATIONS AND SHAREHOLDERS, ¶ 2.01[3] .

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

23

Easiest Hardest

Pooling of Labor and Capital

Sole Proprietorship Partnership Corporation

Individual Aggregate / Entity Entity

Commentators have used the desirability of allowing the pool-

ing of labor and capital to justify the tax treatment of a profits interest in a partnership. But this policy goal of facilitating pooling lacks a solid normative justification. Pooling of labor and capital can take place in any entity form, from a sole proprietorship to a publicly-traded corporation. At one end of the spectrum is a sole proprietor-ship funded entirely with debt. There is no entity, and the owner/laborer is, of course, taxed as an individual. At the other end of the spectrum is a C Corporation, taxed at both the entity level and in-dividual shareholder level. In the middle stands the partnership, which is sometimes treated as an aggregate of individuals, and some-times as an entity. Compared to a corporation, it’s easier for investors and founders to get into and get out of without incurring tax. But it’s not as simple as a sole proprietorship.

Line-drawing rules distinguishing between pooling transac-

tions (treated as non-recognition events) and exchange transactions (treated as recognition events) will tend to be arbitrary. In the context of partnership tax, the current rules treat the receipt of a profits inter-est as a pooling event, but the receipt of a capital interest as an ex-change (like the receipt of other forms of property, like stock or cash, received in exchange for services). Professor Laura Cunningham’s 1991 Tax Law Review article challenged the logic of distinguishing be-tween a capital interest and a profits interest in a partnership. There is no economic distinction, she noted, between a capital interest and a profits interest that would justify taxing the two interests differently.45

45 Cunningham, supra note 11.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

24

Because the value of a profits interest, like the value of a capital inter-est, depends on the value and expected return of the partnership’s underlying assets, she concludes that the distinction is without a dif-ference. Treating one as “speculative” simply because it has no cur-rent liquidation value does not bring one closer to economic reality.46

Professor Cunningham nonetheless ultimately agreed with the status quo treatment of a partnership profits interest when the profits interest is granted in exchange for future services.47 The policy against taxation of unrealized human capital, she explains, “would dictate against taxation until realization occurs. Nothing in subchap-ter K changes this result: In fact, subchapter K arguably was in-tended to encourage just this type of pooling of labor and capital by staying current tax consequences until the partnership itself realizes gross income.”48 For Cunningham, the only relevant question is whether the partnership interest was received for services performed in the past or in the future. Property received for services already per-formed ought to be taxed currently, regardless of whether the prop-erty is styled as a profits interest or a capital interest. If property is re-ceived in exchange for future services, however, current taxation would violate realization principles, and a wait-and-see approach is proper. Embedded in Cunningham’s argument, however, is the as-sumption that subchapter K was arguably intended to encourage

46 Cunningham, supra note 11, at 256. As an example, Cunningham discusses a partnership that holds a single asset, a ten year bond with a face amount of $1000 bearing interest at the rate of 10% a year. The partnership hires a service partner, S, who receives (1) a 25% interest in both the profits and capital of the partnership, (2) a 65% interest in the partnership capital, but no profits interest, and (3) a 40% profits interest, but no capital. In each case, the current fair value of S’s interest is 25%. Yet the tax consequences differ markedly. This result, she ar-gues, “ignores the economic reality that any given interest in a partnership is composed of some percentage of the partnership’s capital and the return on capital, or profits.” Separating the two conceptually, she continues, is a mistake. “The disaggregation of these components of the interest does not change the fact that each represents a significant portion of the value of the partnership’s assets.” Taxing one while not taxing the other, she concludes, has no apparent justification.

47 See Cunningham, supra note 11, at 260 (“Where the profits interest is granted in anticipa-tion of services to be rendered in the future, … taxation of the interest on receipt would violate the realization requirement and the policy against taxing human capital. This would be incon-sistent with the basic purpose and structure of subchapter K.”)

48 Cunningham would therefore limit immediate taxation to cases in which the service partner completed all or substantially all of the services to be rendered at the time it receives its interest in the partnership.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

25

“just this type of pooling of labor and capital[.]” It depends what type of pooling “this” type refers to. Congress contemplated the pooling of labor and capital among small business professionals. But Cunning-ham does not address the workings of these rules in the large invest-ment fund context. Today, perhaps two or three trillion dollars in in-vestment capital is flowing through private investment partnerships, with the income derived from managing that capital largely deferred until realization. It’s not clear that Congress would make the same choice if asked to consider it on these terms. Taxing the value of self-created assets. To examine the ques-tion more closely, it is useful to assume for the moment, as tax schol-ars normally do, that the tax liability of partners should generally be determined by treating the partnership as an aggregate of individuals, rather than as an entity. Aggregate treatment generally dictates that an individual be taxed identically whether the business is operated in partnership form or as a sole proprietorship.49 The next question is whether, in a sole proprietorship, one would be taxed on an unrealized increase in wealth attributable to one’s own labor. The answer, under current law, is no: One is gener-ally not taxed on unrealized imputed income in the form of self-created assets.50 If you build a gazebo in your backyard, you are not taxed when the last nail is struck. You are only taxed, if at all, when you sell the house. If you rent a kiosk at the mall and stock it with appreciated works of art, you are not taxed when you open for busi-ness. You are only taxed as you realize profits from selling the paint-ings.

Should this tax treatment be extended from the individual to the partnership context? The policy rationale in extending the Code’s generous treatment of self-created assets to partnerships may derive from a desire to be neutral between a service provider’s decision to act as a sole proprietor or provide services within a partnership. Tax-ing a service partner currently would appear to distort the choice be-tween becoming a partner versus a sole proprietor engaging in a bor-

49 See Cunningham, supra note 11, at 260-61. 50 See Mark P. Gergen, Reforming Subchapter K: Compensating Service Partners, 48 Tax. L.

Rev. 68, 79 (1992); but cf. Noel Cunningham & Deborah H. Schenk, How to Tax the House that Jack Built, 43 TAX L. REV. 447 (1988) (arguing for accrual taxation when a taxpayer uses capital on its own behalf).

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

26

rowing transaction.51 Professor Rudnick, following this train of thought, argues for deferral. She acknowledges that the analogy is imperfect; some projects are too risky to be funded entirely with debt. In that case, she argues, pointing to restricted stock (coupled with an § 83(b) election) as the classic example, “the tax law has generally al-lowed service providers to share equity returns with others and to re-ceive capital gain returns.”52

A subtle yet important detail, however, distinguishes the taxa-tion of a partnership profits interest from restricted stock. When valuing restricted stock for purposes of a § 83(b) election, the relevant regulations do not allow one to rely on liquidation value alone. In the context of high-tech start-ups, for example, the rule of thumb among Silicon Valley practitioners is that even in the case of common stock with no liquidation value, the common stock should be valued at least at one-tenth the value of the preferred stock to reflect the option value of the common stock. This approximation is generally thought to be low, and these valuations have been receiving increased scrutiny as a result of § 409A. But even at a low valuation, current practice with respect to restricted stock results in some immediate recognition of in-come, while partnership profits interests, under current law and the proposed regulations, may be valued at their liquidation value or zero. There is, in other words, an inconsistency between the treatment of partnership and corporate equity that Professor Rudnick does not fo-cus on. Still, Professor Rudnick is right in that the tax Code tends not to tax the imputed income from self-created assets. Professor Len Schmolka, along similar lines, argues that just as one should not be taxed on the creation of self-created assets until realization occurs in a market transaction, neither should one be taxed on the creation of partnership-created assets. One should be taxed only on the income that those assets actually generate in market transactions.53

Professor Schmolka suggests that we need only ask one ques-tion: Were the services rendered in one’s capacity as a partner? If one acts as a partner (and not as an employee or independent contrac-

51 Rudnick, supra note 38, at 354. 52 Rudnick, supra note 38, at 355 & n.528. 53 See Schmolka, supra note 16, at 294.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

27

tor) then one ought to be allowed to enjoy the benefits of Subchapter K. He explains that the “same policy of tax neutrality that apparently animated the contribution and distribution rules” should bar recogni-tion by partners, “provided they join as partners” and not as mere employees or independent contractors.”54 If one insists on recognizing the economic value of a profits in-terest, Professor Schmolka argues, the proper economic analogy is to § 7872, which governs compensation-related and other below-market interest rate loans. Professor Cunningham’s central premise is that a naked profits interest shifts the use of capital for an indefinite period to the service partner. “Economically,” Professor Schmolka notes, “that temporary [capital] shift is the equivalent of an interest-free, compensatory demand loan.” The service partner is compensated through the use of the other partners’ money. Section 7872 principles ought to apply. Section 7872 would force service partners to recog-nize ordinary income for the forgone interest payments on the deemed loan; if the deemed loan had an indefinite maturity, then the rules would demand this interest payment on an annual basis so long as the “loan” remained outstanding. Subchapter K normally comes close to this result by looking to actual partnership income (the income pro-duced by the constructive loan) rather than using a market interest rate for lack of a better proxy. So long as the service partner’s ser-vices are rendered as a partner and not as an employee, Professor Schmolka concludes, nothing beyond subchapter K is needed. Professor Schmolka’s argument holds up, however, only if the partnership is one that has current income from business operations, like a law firm or a restaurant. The income of the partnership is not a good proxy for the ordinary income of a service partner if, as is the case in venture capital and private equity funds, the realization doc-trine defers the partnership’s recognition of income for several years. (The partnership’s timing of income is determined at the entity level, when it liquidates portfolio companies. Even with an increase in

54 See Schmolka, supra note 16, at 297 (emphasis in original). Schmolka stresses that the tax law draws distinctions analogous to the capital/profits interest distinction all the time, when-ever it draws a line between property and income from property. For example, the transfer of a term interest in property yields different tax consequences than transferring a remainder inter-est. See Schmolka, supra note 16, at 289. The coupon stripping rules of section 1286, he asserts, “mark the only instance of congressional abandonment of this judicially developed distinction between property and income from property.” See Schmolka, supra note 16, at 291 n.20.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

28

wealth, there is no income to allocate to the partners until investments are liquidated.) In sum, the tax treatment of a partnership profits interest pro-vides deferral benefits that go beyond what one might achieve with an economically equivalent transaction (a nonrecourse loan from the LPs to the GP, followed by an investment of the proceeds in a capital interest in the partnership). Professor Schmolka’s observation that such deferral benefits are consistent with subchapter K principles is accurate, but besides the point: these principles are in tension with other aspects of the tax Code (such as §§ 83 and 7872) that argue for taxing human capital in an economically accurate manner. Ulti-mately, the correct approach depends on the extent to which we want to allow the flexibility and favorable tax treatment of subchapter K to override other tax policy considerations. Professors Cunningham, Schmolka, Rudnick and Gergen all raise valid concerns about the measurement of unrealized income; I address these concerns next.

C. Measurement Concerns

The strongest argument for deferral is the difficulty of measur-

ing a partner’s income on an accrual basis. This argument is espe-cially strong in the context of venture capital and private equity funds, where the underlying investments are illiquid. A mark-to-market system could not function, as there is no market for portfolio companies from which we could reliably estimate a value.55

Cost-of-capital method. The valuation problem may not be as intractable as it seems. While neither a mark-to-market nor mark-to-model system is desirable, we could use another proxy, which I call the “cost-of-capital” method. The GP would have imputed income, on an annual basis, of an interest rate times its share of the profits

55 Under certain assumptions, deferral is a red herring. So long as tax rates are constant and the employer and employee are taxed at the same rate, deferral is irrelevant, as the increase in income also gives rise to greater tax on that income later on. In this context, however, the tax rates are not equivalent, assuming a capital gains preference. The compensation (if one chooses to view it as such) should be taxed at 35%, but because the character of the income is deter-mined at the partnership level, the earnings are often taxed at the long-term capital gains rate of 15%. One could characterize this as a conversion problem, but the opportunity arises only because we allow the income to be deferred in the first place.

Draft of 5/4/2007

TWO AND TWENTY

29