True Brit Preview

description

Transcript of True Brit Preview

-

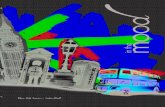

LEO BAXENDALEFRANK BELLAMYBR IAN BOLLAND

MARK BUCK INGHAMJOHN M BURNS

ALAN DAV I SRON EMBLETONHUNT EMERSONDAVE G I BBONS

FRANK HAMPSONBRYAN H I TCHSYD JORDAN

DON LAWRENCEDAV ID LLOYD

DAVE MCKEANM IKE NOBLE

KEV IN ONE I LLFRANK QU I TELY

KEN RE IDBRYAN TALBOT

BARRY W INDSOR-SM I TH

LEO BAXENDALEFRANK BELLAMYBR IAN BOLLAND

MARK BUCK INGHAMJOHN M BURNS

ALAN DAV I SRON EMBLETONHUNT EMERSONDAVE G I BBONS

FRANK HAMPSONBRYAN H I TCHSYD JORDAN

DON LAWRENCEDAV ID LLOYD

DAVE MCKEANM IKE NOBLE

KEV IN ONE I LLFRANK QU I TELY

KEN RE IDBRYAN TALBOT

BARRY W INDSOR-SM I TH

A CELEBRATION OFTHE GREAT COMIC BOOK ARTISTS

OF THE UK

A CELEBRATION OFTHE GREAT COMIC BOOK ARTISTS

OF THE UK

-

Edited by George KhouryEditorial assist by David A. RoachBook design/artwork original and digitalversion by Paul Holder Email: [email protected] and production assist by Eric Nolen-Weathington

CONTRIBUTORSBrian Duke Boyanski, Norman Boyd, Jon B. Cooke, Peter Hansen, Paul Holder, George Khoury, Eric Nolen-Weathington, David A. Roach

SPECIAL THANKSRichard Ashford, Alex Bialy, Rich DeDominicis, Jamie Grant, Paul Gravett, Lis Lawrence, Garry Leach, Craig Lemon, Marc McKenzie, Ian Robson, Matt Smith, Greg Strohecker and the staff at 2000 AD

TwoMorrows Publishing10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh,North Carolina 27614www.twomorrows.comemail: [email protected]

All DC Comics, Marvel Comics, Rebellion A/SComics, and other material, illustrations, titles,characters, related logos and other distinguishingmarks remain copyright and trademark of theirrespective copyright holders and are reproducedhere for the purposes of historical study.

First print edition July 2004Digital Edition created September 2011

THE HISTORYOF BRITISHCOMIC ART

by David Roach 6

LeoBAXENDALE 42

FrankBELLAMY 52

BrianBOLLAND 70

MarkBUCKINGHAM 90

John MBURNS 93

AlanDAVIS 105

RonEMBLETON 116

HuntEMERSON 128

DaveGIBBONS 140

FrankHAMPSON 146

Prefaceby George Khoury 5

-

BryanHITCH 156

SydneyJORDAN 174

DonLAWRENCE 180

DavidLLOYD 193

DaveMcKEAN 204

MikeNOBLE 212

KevinONEILL 224

FrankQUITELY 234

KenREID 251

Bryan

TALBOT 262BarryWINDSOR-SMITH 269

Contributors Biographies 280

-

6 true brit the history of british comic artTH E GR I T I N D I G I TA L T RUE B R I TOver the last 30 years, British comic book creators have had a tremendous impact over how comic arecrafted today. British writers, like Alan Moore, Garth Ennis, Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, and WarrenEllis, have entirely changed the dynamics of how we perceived stories in these four-color books, eachof them re-energizing a form that had been stagnant for too long. For their written work, these menhave received loads of much-deserved accolades and recognition, but the artistic counterparts wereremaining a bit under-looked. Dont know about you, but I find the artwork by Windsor-Smith, Gibbons,and Bolland as alluring and as important to comics today as when I was a 13-year old schoolboy,discovering their works for the first time. These artists are very much storytellers and pioneers in theirown right, theyre the ones whose art heralded those issues of Conan the Barbarian, Watchmen,Batman, and so many other fondly-remembered titles. So it was my privilege to have had theopportunity to spearhead True Brit, a book exactly as the subtitle indicates: A Celebration of the GreatComic Book Artists of the U.K., and the last of my sort-of trilogy of books on British comics that startedwith Kimota! and continued with The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore.

True Brit was an idea which had been brewing in my head for abloody long time. There have been various articles and occasional magazine

issues, here and there, devoted to comics British Invasion, but I wanted to painta more complete picture, one that was inviting, attractive and accessible to comics readers, both new andold. This is an in-depth book that studies the roots of British comics. We look at the work of classic artistslike Ken Reid, as important as the contributions made by young guns like Frank Quitely to the entirepicture. Within this book are interviews and profiles of, in my opinion, the very best British artists ever tohave drawn a comic book. Each and every one of the 21 artists is someone of quality and someone Irespect, for who they are and the work theyve done throughout each respective career. Without anyhesitation, I can say this is easily the most important book of the few that Ive produced.

Here in America, very little is known of the British creators prior to Barry Windsor-Smith. Artists like FrankBellamy, Leo Baxendale, and Sydney Jordan are far from household names; a tragedy, really, becausewhen you see their art, it will seduce you. Adding to the tragedy is the fact that not much of the U.K.s mostimportant comics prior to mid-70s has not been reprinted or imported into the States. Theres also agrowing concern in the U.K. that, as British comic readers grow older, new readers are not discovering therichness of the nations history in comics. Long gone are the golden age days of U.K.s very active comicsfandom in the 70s and 80s, when great magazines about comics, like Arken Sword, Fantasy Express,Speakeasy, and Escape were commonplace in comic shops. My hope is that this book will provoke people tosearch for the work of artists they are less familiar with, to appreciate even more the ones they know. Ifyoure feeling that American comics are becoming somewhat redundant, search those great U.K. titles thatfeature strips Garth, Jeff Hawke, Charleys War, Dan Dare, and Modesty Blaise. You wont bedisappointed in how entertaining and beautiful these serials are.

Its hard for me to believe that this 200-page book was completed in less than a year, because of the greatmany people and sheer research involved. I pitched the idea to my publisher, John Morrow, on August 13,2003, and the completed tome was in stores roughly around the same date,one year later. If there was a difficult decision, it was narrowing down a listof artists to interview and profile from what seemed like hundreds of greats;so I decided to cover the gamut of the artists who I decreed most important,and best represented this history we were writing about. Along with theother contributors of this book, I made an effort to interview as many livingartists as possible, to capture each ones story and feelings regarding theirheritage (and for those deceased, feature profiles filled with the appropriaterespect and sincere admiration).

Above all, I enjoy working with my friends and everyone who made acontribution in this book is a friend. I dont think I could have done True Britif that wasnt the case. Its important for me to know who Im working with,and Ive toiled with good people, people of substance, so Im very proud ofeveryone who lent a hand. Those appendages belong to old friends like JonB. Cooke and Eric Nolen-Weathington, as well as newer friends fromacross the pond: Brian Duke Boyanksi, Norman Boyd, Paul Holder (alsothe brilliant designer of this project) and Peter Hansen. David A. Roach wasmy Yoda, my spiritual encyclopedia of the entire 100-plus-year history ofBritish comics, and has been one of the top artists in U.K. funnybooks forclose to 30 years. David spoke to me for many hours over the last year, andwrote the important and exhaustive historical exposition that opens thisvolume. No one was more important in making this book than Mr. Roach,who always and unerringly pointed me in the right direction.

So, in closing, why would a Yank like me, one from the armpit of the UnitedStates (thats New Jersey), write and edit a book on comic creators from theBritish Isles? Because I wondered why there were so many great artistscoming from the same place, and I think, with this book, we discovered abeautiful kinship that crosses different artists. As I said in the originalpreface of the book, This tome is recognition for every British artist (past,present, and future) for a rich heritage that I hope will never be forgotten. Itrust these sentiments are apparent whether youre just browsing or doingus the courtesy of actually buying this book.

PREFACE

THEHISTORYOFBRITISHCOMICART by David Roach

by

George

Khoury

Judge Dredd Megazine cover art by Patrick Goddard & Dylan Teague. Rebellion A/S

-

The story of British comics is a long, rich,diverse, frustrating and largely untold one.Britain was one of the first countries of theworld to develop the comic strip as we know ittoday, predating American strips by severalyears. Indeed, some believe it to be the truehome of the comic strip. For the first fewdecades of its existence, from the 1890s to atleast the 1930s, the British strip evolvedlargely in isolation from developments,traditions and innovations from elsewhere,creating its own idiosyncratic language. Whileboth British and American strips share acommon root in such Victorian humoroustitles as Punch and Puck, they emerged indifferent formats. British strips initiallyappeared in comic books, only establishing asignificant presence in newspapers in the1920s, while in the States the opposite is true;there, newspaper strips inspired a comic bookcounterpart in the mid-30s. In fact, in mostcritical ways it is Britain that led the world increating the comic strip as we know it today,from the comic strips in the first regularlypublished comic book (Comic Cuts in 1890) tothe first significant recurring characters(Weary Willie and Tired Tim, in IllustratedChips in 1896) and the first adventure strip(Rob the Rover, in 1920).

From the late 40s onward, the Britishadventure strip really came into its own, partlyinspired by Americas comic strips, and thiscaused a schism in the marketplace andamong fans which persists to this day. So it isprobably true to say that there are two distincttraditions of British comics: humour comicsthat have their origins in Tom Brownes WearyWillie and Tired Tim, and post-war adventurecomics, which combined British and American

influences. Strangely, UK comics historianshave largely been fans of the humour comicsand have regarded the nations Golden Age ofcomics as being in the 20s and 30s.Consequently, what has been written about thecountrys comics (and there has beensurprisingly little) has been grotesquelyunbalanced, partial and misleading. This hasextended to the perception of comics as awhole in the UK; for a long time, they havebeen seen as a juvenile, disposable andsomewhat tawdry medium, with little ofsubstance or depth to it. Nothing could befurther from the truth.

In America, Britain, and mainlandEurope, sophisticated societythroughout the Victorian era wasentertained by humorous publicationswhich combined comic verse withsatirical illustrations and cartoons. In Britain, publications such as Punch &Judy and Comic News often featuredcomic illustrations and even rudimentary

strips short, comicnarratives told over thecourse of several linkedillustrations with accomp-anying captions and eventhe occasional wordballoon. However, althoughpublications such as FunnyFolks (1874) and Ally SlopersHalf Holiday (1884) regularlyfeatured these proto-strips,each issue was dominatedby captioned singleillustrations and short textpieces. The British comicstrip as we know it reallyemerged in Comic Cuts, firstpublished by AlfredHarmsworth in 1890, whichfeatured many short stripsand set the pattern of Britishcomics for the following fewdecades. It was cheaplypriced (at a half-penny), wasprinted in a black-and-white tabloid format, andwas published weekly.

Comic Cuts was soon joinedby competitors such asFunny Cuts as well ascompanion titles fromHarmsworth itself, such asIllustrated Chips and Funny

Wonder. All were published weekly and allran at a miserly eight pages! Visually,they shared the broadly realistic, highlyrendered and somewhat fussy styling ofmost Victorian publications, but all thatchanged dramatically with the arrival of thefather of British comic illustration, TomBrowne. Browne was something of aRenaissance man, entering comics in 1895 at

Rob The Rover

Weary Willie and Tired Tim

Art by Tom Browne. AP/FleetwayOther images respective holder.

the history of british comic art true brit 7

-

the age of 23, working for two years in theUnited States for the leading New York andChicago dailies, and travelling across Europeand the Far East as an artist for The Graphic. Onhis return to London, he helped found theSketch Club, exhibited at the Royal Academyand became a member of many leadingartistic societies, including the Royal Institute,before dying at the tragically early age of 38.

What Browne brought to comics, particularlyin the form of his first significant strip work,Weary Willie and Tired Tim (which firstappeared in Illustrated Chips #298 in May, 1896),was a dynamic, pared-down, linear style thatdid away with Victorian over-rendering at astroke. Browne was inspired by the elegantminimalism of Punch magazines leadingcartoonist, Phil May, but he combined Maysprecision of line with a wicked eye forcaricature and exaggeration. The result wasthe modern comic strip as we recognise ittoday. Interestingly, R.F. Outcaults first YellowKid strip appeared some six months later,which puts the lie to the notion that hepioneered the form. Admittedly, the Brownestrip rarely used speech balloons in its earlyyears, preferring the standard Britishapproach of a printed caption beneath eachpanel. However, the captioned panel was aubiquitous feature of British comics right up tothe second world war, and is indeed stillcommon in comics for the very young to thisday it is simply a quirk of the nations comics.It is also worth noting that, whereas Outcaultsearly strips had little plot, background ordialogue, Brownes strips were wittynarratives with fully realised settings, aroving visual viewpoint and a keen earfor dialogue. Visually, Browneseconomy of line was years ahead ofOutcault and his fellow pioneers,

F. Opper, Jimmy Swinnerton, and even RudolfDirks, creator of the Katzenjammer Kids.

The Adventures of Weary Willie and TiredTim, two work-shy tramps prone to endlessmishaps and pratfalls, quickly propelledIllustrated Chips to sales of 600,000 copies perweek an astonishing figure for the 1890s and helped make Harmsworth into thecountrys leading publisher. Through mergersand name changes over the years,Harmsworth became first the AmalgamatedPress, then Fleetway, IPC and Fleetway againbefore being bought by Egmont/Methuen inthe 1990s. For most of its 100-year existence,the company was the countrys most prolificand successful comic publishing house andenjoyed a virtual monopoly until the late 30s.In the early years of the twentieth century,Harmsworth/AP released a steady stream oftitles, including The Rainbow, Puck, TheButterfly, Comic Life, Merry and Bright, Tip Top,Sparkler, and The Jolly Comic. These wereaimed at a predominantly young readershipand featured strips about children,anthropomorphic funny animals (such asJulius Stafford Bakers Tiger Tim in TheRainbow) or disaster-prone adults in the WearyWillie-Tired Tim mould. Such artists as H.S.Foxwell, Frank Minnitt, Brian White, PercyCocking, and Albert Pease found greatsuccess by working broadly in the Brownestyle, which remained largely unchallengedfor decades.

Whereas in the United States the comic striporiginated in newspapers before spreading to

comic books some 40 years later, in Britain thereverse was true. Aware of APs success,many of the countrys leading newspapersadopted their own strips, including (in 1919)A.B. Paynes whimsical Pip, Squeak andWilfred, which ran for 36 years in the DailyMirror. The strip described the gentle highjinksof a dog, a rabbit, and a penguin, and itattracted a loyal following (known as theWilfredian League of Gugnuncs) numbering inthe hundreds of thousands. Other importantstrips included J.F. Horrabins Dot and Carrie,Roland Davies Come on Steve, and CharlesFolkards Teddy Tail, which first appeared inthe Daily Mail in 1915. However, the mostsuccessful British newspaper strip of that orany other era was undoubtedly Rupert theBear, created by Mary Tourtel for the DailyExpress in 1920.

Tourtels elegant, simple line was bothcharming and sophisticated, and the littlebears whimsical adventures in the village ofNutwood immediately struck a chord with thepapers readership. Collections of Rupertstrips appeared as early as 1921, and the firsthardbacked annual collection made its debutin 1930, initiating a publishing sensation thatcontinues to this day. Tourtel retired in 1935and was succeeded by Alfred Bestall, who wasin his 40s and already a distinguished andsuccessful illustrator for Punch and The Tatler.Bestall soon became one of the mostimportant comic artists that the country hasever produced, and under his brilliantstewardship the strip became a British

8 true brit the history of british comic art

Rupert the Bear

Art by Alfred Bestal andMary Tourtell. ExpressNewspaper

-

institution, delighting generations of readers and inspiring a mountain of merchandise. The wonderfullyeccentric strip invariably featuredyoung Rupert encountering astrange array of characters, frompirates and Gypsies to pixies,dragons, talking birds,magicians, inventors andcannibals. Another eccentricitywas the strips unique format.In the annuals, each pagedisplayed four identicallysized panels, below each ofwhich were two lines ofrhyming narrative, while two furtherparagraphs of text appeared at the bottom ofthe page. This meant that each story waseffectively related three times: first in pictures,then in rhyming couplets and finally, inexpanded form, in prose. Happily, the annualsstill maintain that strange convention to this day.

Bestalls visual style flourished in the stripsrigid conformity, displaying virtuoso drawingand a remarkable sophistication imagine across between Arthur Rackhams fairy taleillustrations and Hergs minimalist Tintinartwork, and you will get some idea ofBestalls style. For the covers and endpapersof the annuals, Bestall would create achinglybeautiful, character-filled panoramas, fullypainted in subtle washes of watercolour whichwould have made Rackham proud. Bestallalso appeared to have an unusual interest inthe Orient; he often filled his strips withChinese dragons, pagodas and conjurors, aswell as regularly providing readers withorigami puzzles. Under his tenure, sales of theannuals grew to one-and-a-half million copiesper issue at peak, and they still sell over250,000 today. The great man began to scaledown his Rupert work in the early 70s anddrew his final strip in 1982; he died four yearslater, soon after receiving an MBE from theQueen. In his later years he had starred in a TVspecial written by Monty Pythons Terry Jones,and his biography had been written by GeorgePerry. Among Ruperts almost uncountable

mediatie-ins can befound comics, toys,several animatedcartoon series,confectionery, books,hit records (includingthe Frog Chorussingle by PaulMcCartney, whichreached numberthree in the Britishcharts in 1984), andeven shops devotedto the character.Artists Alex Cubieand John Harroldhave kept the stripalive since Bestalls retirement, and right up tothe present day each new generation of youngBritish readers is raised on Rupert.

Another notable early newspaper stripboasted an artist who, like Bestall, had comefrom the illustration field. This Daily Sketchstrip was called simply Pop, and his artistwas the extraordinary J. Millar Watt. Pop effectively a British version of GeorgeMacmanus legendary US strip Bringing upFather centred on the pratfalls of a put-upon,portly dad and his demanding family. LikeBringing up Father, the strip was oftenvisually quite stark, but Millar Watt had the

expressive, loose line of a painter rather thanMacmanus Deco-minimalism. A quirk of thePop feature was Millar Watts way with a joke:in each four-paned installment, panels oneand two set up the gag, panel three had thepay-off, and the final panel usually contained awordless reaction shot. Millar Watt was anoutstanding draughtsman and imbued hislinework with an expressive vitality and asense of space and drama that bordered onthe poetic. With its visual sophisticationmarried to a more conventional thoughinvariably funny storyline, Pop appealed toboth intellectuals and the masses, and it ranfrom 1921 to 1960.

Miller Watt retired from the strip in 1949 toconcentrate on his illustration work (GordonHogg took over Pop in his absence) but in themid-50s he was recruited into APsburgeoning comics line, where he enjoyed athird career change as a comic book artist. For the rest of the decade he drew incrediblydense and detailed strips such as Robin Hoodand The Three Musketeers while alsopainting a series of outstanding covers. In the60s he moved on to full-colour, glossyAP/Fleetway prestige comic titles such asRanger, where he drew his final major stripwork in 1965: an atmospheric adaptation ofTreasure Island. With that exception, however,from 1962 until his death at the age of 80,Millar Watt concentrated primarily onillustrations for Look & Learn, Princess and OnceUpon A Time illustrations which rival the likes

the history of british comic art true brit 9

Pop

Tiger Tim AP/Fleetway

Happy Days by Roy Wilson. AP/FleetwayPop by J. Millar Watt. Daily Sketch.

-

42 true brit leo baxendale

It would be impossible to have a book about great British comicartists without including the enigmatic Leo Baxendale. In theearly 1950s, British weekly comics were undergoing a revolutionwith the Eagle comic entering the marketplace to redefine thestandards for boys comics. In Dundee, Scotland, home of thegiant DC Thomson publishing empire this new event was largelyignored and the focus instead was to revamp their own line ofpopular comics and redefine the way humour comics were presented.

Given a new direction, men who became comic legends such asDudley Watkins, David Law, Ken Reid, and Paddy Brennanstormed onto the scene ushering in the new era. At the centre of this cauldron of creativity was Che Guevara himself, Leo Baxendale.

An outspoken Englishman from Lancashire, Baxendale was aself-taught artist who after completing his National Service inthe Royal Air Force in 1950 joined the art department of the localLancashire Evening Post newspaper, where he wrote and

illustrated his own short, humorous

pieces. He also gained experience drawing theoccasional comic strip and sports cartoons.

At the age of 21 Baxendale submitted some of hiscomic strips to the Beano comic published by DCThomson. They hired him immediately and he beganwork on a number of minor pieces as a freelance artist.His first real comic strip, Little Plum, Your RedskinChum, made its debut on October 10, 1953.

Instantly popular, this strip was followed up withMinnie the Minx and When the Bell Rings, whicheventually changed its name to the now world-renowned The Bash Street Kids. He added to his ever-growing output in 1956 when he started drawing thepopular Banana Bunch and The Gobbles in the new

comic, Beezer.

His last major contribution for the firm was the addition of TheThree Bears in the Beano in June of 1959. This hilarious animalstrip where the animals are more human than the peoplebecame extremely popular.

In 1964, following a rift with DC Thomson, Baxendale left to workfor Odhams Press. Surprisingly the refit revolved around artistic

license and not money asone would expect. Once thedie was cast Baxendalebegan preparing a total of30 samples which he sentout to British comicpublishers at the rate oftwo per day. Years later hefound out from AlbertCosser of Odhams Pressthat he neednt have goneto all that trouble, as

Cosser recounted, If youd have sent a scribbled note sayingIm available, that would have been enough.

As it happened only two packages were mailed out and bothrecipients responded quickly. Two days after he mailed hispackages Baxendale was sitting across the table in Dundee withAlf Wallace, the managing editor of the Odhams group of comics,who had traveled from London to see him in person. He toldBaxendale that Odhams market research had revealed thecomplete dominance of DC Thomsons comics in themarketplace, especially the Beano. He went on to say that hedidnt want Baxendale to draw some strip in Eagle or Swift, but

instead wanted to build a newcomic around his talents.Within a short time a newcontract was signed thatdoubled Baxendales income inone fell swoop. Furthermore,he could now sign his work,and the new comic would beprinted in full-colour gravure.At Thomsons any scriptsprovided by Baxendale hadbeen free, but Odhams werewilling to pay him for any hemay write, which would further

Bash Street Kids

Leo

BAXENDALEby Peter Hansen

Leo photo: Respective holder. Bash Street Kids, Three Bears DC Thomson. Bad Penny: Odhams.

-

Graphic, unfussy, stylish yet modern a very distinctive signature, making abold statement, in fact insisting upon it. A very distinctive artist whosedraughtmanship, design anddynamism made him one of themost dramatic of illustrators. In acareer spanning over three decadesencompassing adventure, mystery,fantasy, science fiction and historicaladventures he became one of the finestand most influential of British comicartists. His major works wereproduced from the mid-1950s until thelate 60s, during a golden era forBritish comics, inaugurated by the highquality Eagle comic which was to makehis name.

Frank

BELLAMYby Paul Holder

52 true brit frank bellamy

1917 -1976

-

frank bellamy true brit 53

Frank AlfredBellamy cameinto the worldon 21st May

1917 in a small bedroom of a Victorian terraced house in BathRoad, Kettering, in the county of Northamptonshire. A centralpart of England that is obviously a fertile breeding ground fortalent as artist Alan Davis and writer Alan Moore both hail fromthe region. The second child of Horace and Grace and youngerbrother of Eva, Frank was a bright and lively boy, full of jokes andfun who soon displayed a love for drawing. He must have cravedadventure too, as at the age of six or seven, he managed to pullsome hairs from a lions tail while visiting a local circus. Theywere proudly kept in a jar for a number of years no doubt untilhe could fulfill his ambition to be a big game hunter! Art andAfrica remained abiding passions throughout his life.

If he couldnt be a big game hunter then he would have to be anartist. Luckily, Kettering had its own advertising studio and soonafter leaving school he managed to get a job there. He spent

some six years at William Blamires studio, with a break for hisnational service, learning lettering, layout and honing hisdrawing skills. There was a lot of local advertising and displaywork, particularly for the local cinema advertising forthcomingattractions such as the films of Cagney and Bogart. He hadvolunteered to go to Africa when his call up papers arrived, butwas considered more useful to the army as an artist and postedto West Auckland in Northern England. Over a period of sixmonths he painted an aircraft recognition room, thereby beingone of the few people allowed to draw the German swastika, yetstill managed to draw a weekly football cartoon for the KetteringEvening Telegraph for their Saturday sporting paper The Pinkun. He was promoted from Lance Bombardier to Sergeant.Promotion from the ranks of a single man came when hemarried 19-year-old Nancy Caygill from nearby BishopAuckland, County Durham on 6 March 1942.

A son, David, soon followed in 1944, like Frank arriving at the tailend of a world war. Aware of growing family commitments, helooked to London to further his career, securing a job at Norfolk

Frank and Nancy Bellamy in the mid-sixties

Movie Crazy Years Radio Times publications

-

70 true brit brian bolland

Out of Lincolnshire came this left-handed virtuoso,who grew up on a steadfast diet of Silver Age DCComics, and was so enamored with the art that byeleven he created his very own comics, sequentialdrawings on reams of typing paper. While enrolled atNorwich School of Art, Bolland immersed himselfinto the British underground early strips wereprinted in Oz and Friendz in the early 70s along withthe self-published Suddenly at 2 OClock in theMorning. Upon leaving school he acquired an agent,Bardon Press Features, and landed commercialassignments for magazines such as Time Out andParade along with providing illustrations forrestaurants, concert promoters and otheradvertising work. By 1975 Brian landed his first

professional ongoing strip, rotating artwork withDave Gibbons on Powerman, a comic that wasdistributed primarily in Nigeria and neighboringAfrican countries. Beginning in 1977, he becameassociated with the stellar roster of talented artistsat 2000 AD and became the books most celebratedartist with his bold work during Judge Dreddsgolden age. After a lengthy stay at 2000 AD, DCComics enlisted Brian to render work for GreenLantern, Justice League of America, AdventureComics, and Mystery in Space the work on thesetitles was a childhood ambition now realized. Withwriter Mike W. Barr, the artist undertook the longestnarrative work of his career, (and one of the fewoccasions where his work would be inked by others)in DCs bold experiment the companys first limitedseries Camelot 3000, which was only sold in comicspecialty shops. 1988 brought readers Batman: TheKilling Joke with writer Alan Moore which remainsthe last full-length work hes produced. Afterwardshes dedicated himself primarily to being a coverartist and creating some of the most exciting andtitillating imagery seen throughout his lengthystays on Animal Man, Wonder Woman, TheFlash, and Batman: Gotham Knights. Bollandhas also written his fair share of eccentric

Brian

BOLLANDby George Khoury

Transcription by Marc McKenzie

All c

hara

cter

s

Reb

ellio

ns A

/S

-

brian bolland true brit 71

stories, all drawn by him and capturing his sense ofhumor, like The Princess and the Frog (in HeartThrobs #1), The Kapas (in Strange Adventures #1),The Actress and The Bishop (in A1 Vol. 1 #3), andAn Innocent Guy (in Batman: Black and White #4),plus his chronicling his own ongoing short: Mr.Mamoulian. Today, Bolland illustrates directly intohis computer with his trusty Wacom tablet the samesharp linework and meticulous detail that wevecome to expect from this master.

Lets start at the beginning where and when were youborn? [laughs] Well, I was born on the 26th of March, 1951 in asmall village called Frieston near the town of Boston thats theoriginal Boston in Lincolnshire.

What type of profession did yourparents have? They owned a farm, Ibelieve? Yeah, my dad was a farmer,but we didnt live on the farm. We lived inthe village, but his farm was in the nextvillage, Benington, a couple of milesaway. You dont really have villages overthere [in the United States], but we havevillages. It was a very small farm; it wasonly 68 acres. By American standardsthats like a garden a backyard, isnt it?

No, thats a decent plot of land[laughs]. Yeah.

What did he do on the farm? Did hehave livestock, or ? No, it wasntlivestock, it was arable. Cabbages,potatoes, and sugar beets, things like that.

Did you have any other siblings? Howwould you describe your childhood?No, I was an only child. Growing up Ivegot nothing really to compare it with. Itwas in the country and there was a smalltown nearby. Im not sure what I can sayabout all that; I was I just grew up withwhatever most 1950s-1960s children grew up with, really.

What was your earliest comic book experience? I dontthink I really particularly took to comics until I was nine or ten no, I think I was nine; it was 1960. But, even then, I rememberthat there had been some Batman comics around the house,because I later found them without covers lying around in acupboard. I dont know where they came from, becauseAmerican comics only started being shipped here in 1959. Therewas one from 1956-57; it was a Dick Sprang Batman story. Theone where Batman was there were Batmen from all countries.There was a Mexican Batman and there were... other kinds ofBatmen, all in slightly different foreign Batman outfits.

So your parents didnt have a problem with comics? Ah,well they did later, because from 1960 onwards I started tocollect them in a fairly excessive way and my dad was reallyworried, you know, whether they were a bad influence on me. Heonce threatened to take em out and burn em.

What exactly did he want you to be? He always said he didntreally want me to be a farmer; I had very little interest in the

farm, and he always said that he didnt particularly want me tobe a farmer, but later, in adult life, Id been told that he was, kindof, disappointed that I didnt take up farming. But he was verysupportive when I became interested in art. He was very, verysupportive when I made the decision and paid for me to go to artschool later on.

So when exactly did you get the urge to start drawing? Istarted drawing in 1960 or 61, pretty soon after I started buyingcomics and it was well, actually no, I remember all kids diddrawings at school, whether you take it up later on or not,because Ive still got drawings I did of dinosaurs and of the localbirdlife. There are some drawings I did in crayon of bluetits andthrushes and things. Ive a vague recollection of stickmencomics. Ill have to have a look for them.

Was that one of your Insect League strips? The InsectLeague coincided with the beginning ofmy collecting comics and it was maybetrying to do something that looked like acomic book. That would have been from1960-1961 onwards. I did quite a lot ofthat.

So being a teenager, did youexperience peer pressure because youwere so into comics? When I was 16, Iwas at school with a kid called JeffHarwood, and his brother Dave turned outto be a great comic collector. I met Daveand we became great friends. We still aretoday. He was into the fanzine scene. Iwasnt particularly, but through hiscontacts I got my early stuff printed invarious places.

He would ink your early work, stufflike that? Yes, he inked my stuff, and Iinked him, we did these kind of one-offcomics fanzine type of things together.And that was very good for me because itmeant I had someone nearby who I couldshow the work to and get feedback fromand who would do the same to me. We

just drew in ballpoint pen and colored in in crayon.

But you were pretty much a loner during high school, or ?Well, I had a fairly typical circle of friends. I dont think I was anymore of a loner than most kids. I think the fact was that I was ata school that wasnt all that close to where I lived meant that Ididnt spend time with the local kids. So once I left the school atthe end of the day, I was not surrounded by close friends. So Isuppose to that extent thats true.

So who were the first artists that struck your fancy? Well the first comic I ever bought was called Dinosaurus. I talked my granny into buying it, bless her. It was a Dell comic,from 1960, drawn by Jesse Marsh, although I didnt know his name until many years later, when Joe Staton informed me. After that, I was buying DC, and I think Gil Kane was prettymuch my first passion. I just idolized him and I really wanted todraw like him. But I mean, all those other artists Alex Toth,Carmine [Infantino], Bruno Premiani, Curt Swan, MurphyAnderson they were all there and to various extents they wereinfluences on me.

The Actress and The Bishop Brian Bolland

-

brian bolland true brit 73

What about British comics? Had you not seen too many atthat point? No, I wasnt particularly impressed with them. Iwas never into the funny comics; a lot of people in this country,they were keen on the funny comics like Beano and Dandy. But Iwas never into that at all. There was a comic that started the yearbefore I was born, which is well known, and thats Eagle, but Idnever bought it. So I never got into that stuff until my collegeyears. Ive now got a few of the very first ones from the year Iwas born. Number 6 is the earliest from 1951.

But there were also a lot of adventure artists like DonLawrence, Hampson, and Bellamy. Yes, all of those thingsI discovered in my later teenage years, in my later school years,and through my college years. I was able to, kind of, expand anddiscover everything that was going, including Don LawrencesTrigan Empire and all the Eagle stuff that Id missed in mychildhood, you know?

Were you naturally drawn to Bellamys style? Well, I wasnever a big Bellamy fan; Id never bought anything by Bellamy. Iknew he was very highly regarded, but I never had a FrankBellamy passion at all. In an answer to an earlier question, the firstBritish comics I started buying as a boy, from about the age of 12or 13 in 64 was a comic called Valiant and that had in it a stripcalled The Steel Claw drawn by Jess Blasco, a Spanish artist.

You were very into his work? Very, very much so. I think heused photos quite a bit, which was rare at the time, but it lookedgood. And also, something called Mytek the Mighty, drawn byEric Bradbury a Brit. And various other strips in that comic. Iwas very keen on Valiant, so thats the only British comic I reallywas into as a child. My interest in British stuff was acquired lateron, really. Other things from that period I also got very into SydJordans Jeff Hawke, a daily newspaper strip, and another onecalled Carol Day, by David Wright. Both fantastic andunderrated.

What was it about the Silver Age that struck you, thatappealed to you so much? Well, I mean at the time it wasntthe Silver Age; it wasnt called that until later on, really, was it?Its just the comics that happened to be coming out at the time.

But there was something about the American culture youliked or... was it something about the comics that weredifferent? Thats an interesting question. I mean, as far as thecomics were concerned, I think I liked them as objects. I wasreally keen on the comics and

You were strictly a collector was that what it was? I dontthink I was consciously thinking of building a collection here; Ijust wanted the next one and the next one and the next one. Butwhen I got the comic itself, I held it in my hand like it was sort of

Judge Dredd Rebellion A/S Illustration (right) Brian Bolland

-

90 true brit mark buckingham

British comics were so important to me growing up, and remainso today. I loved Frank Bellamys stuff, and Don Lawrence.... Andas for Frank Hampson and his studio producing such rich andlovingly crafted art on Dan Dare... I wish I could lavish suchtime and effort on my own work. Leo Baxendale... a genius.British humor comics in general, especially Monster Fun andShiver and Shake... I loved those books and I dearly wish I stillhad copies of them. Those were the days when comics were acheap disposable entertainment that you shared with friends.

Collecting? Whats that? 2000 AD and Warrior my two favoriteUK comics of all time and the greatest influence on my work.Kev ONeill, Dave Gibbons, Brian Bolland, Alan Davis, GarryLeach, Ian Gibson, Mike McMahon, Steve Dillon, Bryan Talbot,Alan Moore, Grant, and Wagner... heroes every one!!

I have always loved comics and they have always been a part ofmy life. They helped to establish my appetite for reading from avery early age, inspired me, fueled my imagination and mycreativity, and they offered me a safe haven to escape to duringthose darker moments of childhood. I soon realized that it alsooffered me the chance to access my own imagination and desireto tell stories in a very direct and personal way, and I tookpleasure in using it to entertain others.

I always endeavor to remain open-minded in all aspects of life,and especially in my work. I love to try new things and stretchmyself as an artist. I am also a very versatile artist... I havesurvived when others have not because I am always adapting. Iguess the other reason is that although I rarely dazzle peoplewith my art, writers and editors have often complimented me onthe strength of my storytelling which is something that willalways be essential if you want to survive in this business.

While earning a Bachelor of Arts in Design atStaffordshire University, Mark flirted briefly with acareer in animation before taking on comics. WithinStrip AIDS, he made his debut and became acquaintedwith Neil Gaiman when he provided illustrations for thesatirical magazine The Truth. He broke into DC Comics

as an inker on Hellblazer andestablished himself as one of thetop inkers in the industry with hisbrushwork bringing out the bestof his pencilers in titles likeGeneration X, Sandman, GhostRider 2099, and Death: The HighCost of Living. Championed by

Gaiman and Dave McKean, he was able to prove to theDC brass that he was a more than an inker when hewould fully illustrate a Poison Ivy story for Secret Originsand eventually penciling even Hellblazer itself. InMiracleman Book IV: The Golden Age, Mark displayedhis knack for impeccable storytelling and design,sculpting some of the finest comics ever seen. More ofhis versatility as a penciler can be seen in Death: TheTime of Your Life, Merv Pumpkinhead, Peter Parker:Spider-Man, Batman: Shadow of the Bat, DoctorStrange: Sorcerer Supreme, Mortigan Goth: Immortalis,and his Tyranny Rex art in 2000 AD. Today, you can findhis present work on the critically-acclaimed Vertigotitle, Fables, with artwork as compelling as ever.

Mark

BUCKINGHAMby George Khoury

Who were your British artistic influences? What was their appeal to you?

What lead you to a career in comics? And what has beenyour secret to constantly work in the business?

Convention Ad Art Respective Holders

-

john m burns true brit 93

John M. Burns represents the finest in visualstorytelling graphics not just as a British artist buta visionary who has spent a lifetime advancing hisart without the slightest interest in what it is to be ahot artist, flavour of the moment/month/era, orsimply put a star. All he ever did was thrive in thejoy of telling the best imaginable stories the bestimaginable way: from within, constantly managingto improve and stay fresh no matter if it is doingblack-and-white ink drawings with pen or brush,coloured pen and ink visuals, or painted vistas thatinspire with their sincerity. The reason for hisinclusion in this wonderful book is simple: Mr. Burnsis an artistic treasure a paragon of modesty,

kindness, and generosity, and of dedication tohis craft. John M

BURNSby Brian Duke Boyanski

Judge Dreddcover

Judge Dredd Rebellion A/S

-

94 true brit john m burns

Did you always want to draw comics?

Yes. I always wanted a job drawing or illustrating, well, eversince I was 13 years old and passed my 13+ exam whichenabled me to go to the West Ham County Technical School [inEast London]. Here the lessons were in favour of art. Iremember having the usual career, what you want to do withyour working life when you leave school interview and beingnervous I hadnt explained really what I wanted to do. Later asluck would have it I found out that the careers officer lived nearwhere I lived. I knocked on his front door. He was quiteunderstanding about it and let me explain what it was I wanted to do that I had not explained atthe interview.

This is where luck plays itspart: the illustration studio, Links

Studios, that I eventually joined had decided tocome back to the same school they had acquired their

previous apprentice from. Every two years the Links Studiostook on a young boy as an apprentice the year I was leavingschool was the time for a new apprentice to be taken on. A friendand myself went for an interview. I had concentrated on figureillustration, my friend more towards advertising. The LinkStudios was an agency for comic strip illustrators, so I joinedLink Studios as an apprentice in 1954 at the princely sum of twopounds and five shillings [per week]. The career officer hadnothing to do with my joining Link Studios and becoming anillustrator, but I think it shows how badly I wanted to do this job.

What has inspired you to start drawing in general andwhen did you start?

My brother was always drawing, and I wanted to draw as well ashe did. When I was 13, a friend and I entered and came first andsecond in a national painting competition (the very same friend Iwent to the Link Studios interview with) and the art teacher wasvery encouraging, so having passed the 13+ exams we bothwent on to the County Technical School.

How long are you in the comics business?

I started in 1954 when I became an apprentice at Link Studios.

Well, congratulations for the first 50 years, sir! Now, whowere the artists that inspired and influenced you?

My leaving present from school was a book suggested by my

future studio manageress and owner of Link Studios, DorisWhite. The book was Figure Drawing, by Andrew Loomis anAmerican illustrator and instructor at the American Academy ofArt in Chicago. He was the first of many American illustrators toinspire me. Some of those were Austin Briggs, Ken Rilley, JoeDemers, Joe Bowler, Norman Rockwell, Robert Fawcett afantastic draughtsman and lots more. Later I became aware ofAlex Raymond and Stan Drake, newspaper strip artists.

Are there current visual storytellers that catch yourfancy at the moment?

Not one in particular. I like bits from most. Im usually looking foroutstanding drawing, colour, and storytelling.

Did you ever write your own scripts, or do you prefer towork with other writers?

I would like to be able to write my own scripts, but Ill stick towhat I do best.

Do you challenge a scriptwriter bouncing back andforth ideas, proposing your vision, etc. or do you preferjust to visually realise what is written for you?

I illustrate the script as presented. I might change a point of viewor two if I think it makes a better looking page, but I neverchange the writers storyline.

Did you have any formal art training?

No, but I had a better advantage [than formal art school training]:full-time drawing and being taught by working strip illustrators,plus [it seemed at the time] every night evening classes andweekends sketching in London museums!

When have you decided to start painting your pages? Doyou prefer that to just inking the pencils?

When I realised that transparent inks were not giving me the

Countdown

Countdown Polystyle

-

alan davis true brit 105

Alan Davis wasborn, raised, andcurrently resides in the Midlandsof England. At anearly age, Alandeveloped a keeninterest in stories and soon began creating his own.These stories took many shapes and forms, be theyshort stories (usually accompanied by illustrations),bits of sequential art, or even complicated dioramas.But Alan never thought he would become a comicbook artist. In fact, it wasnt until well after he hadestablished both a career and a family of his ownthat he drew his first professional comic book work.Initially, Alan thought his foray into comics to bemerely a fun hobby he could spend time with duringthe weekends. Before long, though, the hobbybecame the career and a very successful career atthat. From his beginnings on such strips as CaptainBritain, Marvelman, and D.R. & Quinch, throughExcalibur and ClanDestine, and with his currentwork on JLA: Another Nail and Uncanny X-Men, Alanhas built quite a resum. But when its all boileddown, Alan Davis is simply a storyteller.

Im going to call out some names and Id like youto say what you think of first with each one....Frank Hampson.

Well obviously, Ive got to say Dan Dare, but I dont knowwhat else I could say about him really. I know other workthat hes done, but Dan Dare is what hes most wellknown for.

You read Dan Dare some as a child, right?

Yeah, it was actually before I got into looking for my own comics.I had older relatives who had Eagle, but Dan Dare was reprintedat various times, so I did get to see it all. It was a landmark comicand a landmark character. Anyone whos seen it will know thatthe designs and the philosophy behind it were far ahead ofanything that was done in comics then, or even since. As ascience-fiction strip, it had just terrific inventiveness.

Did the strip influence you creatively in any way?

I cant say that it influenced me in a specific artistic way, becausethe artwork was very labor-intensive; it was produced by a studio.Frank Hampson did the original artwork as thumbnails or roughs which were amazing things on their own but then you wouldhave a studio of people do the finished art. They posed incostumes; they built models of all the characters, the ships, thecities; so it was very, very intensive to get the reality of it. All of thisstuff Ive only found out in recent years; I didnt know it at the time.

But could you tell even as a child that there was a lot ofwork going into it?

I dont know. I think that when I was a kid, I just thought thatsome artists are better than others. Its only as you get older thatyou start to really understand the dedication and the limitationsof the medium and the efforts that people make to try andovercome those limitations.

How about Don Lawrence?

Well Don Lawrence did The Trigan Empire, which is what hesmost known for. I wasnt really a fan of Don Lawrences artwork I always found a bit of a woodeness to it but the coloring andthe way it was put together was very nice, and I liked The TriganEmpire as a concept. It was like Spartacus meets 300 Spartansin space. It was always nice to look at, but I wasnt ever reallyinto as much as I was Dan Dare and some other things.

Changing styles a bit, Leo Baxendale.

The creation of his that I liked most as a kid was Grimly Feendish.As a kid I didnt know who Leo Baxendale was, because a lot of theartwork, if it was signed I didnt notice, but there was a lot that wasjust unsigned, and he did have an awful lot of imitators. The thingabout a very simplistic art style is that it is very easy to copy it. Ithink that Leo Baxendale would be the equivalent of Carl Barks inBritish terms. He had a style that everyone else based their workon or at least were very heavily influenced by.

You use a lot of humor in your writing and in your artworkas well at times, depending on what you are working on,of course. Did any of that develop from humor strips likeGrimly Feendish, or was it always a part of you?

I dont know if the humor comes from a specific source like that.I always appreciated it, and I dont know if it was a chicken andegg thing. Did I appreciate it because the humor was in me, ordid the humor appeal to me and make me think that way? I dontreally know. Grimly Feendish was like the British version ofThe Addams Family. I honestly dont remember that much

Alan

DAVISby Eric Nolen-Weathington

Nightcrawler Marvel Characters, Inc.

-

106 true brit alan davis

about it, I just remember that there was a certain look to theartwork and a certain design to the characters that appealed tome, because it was so different than all of the nice stuff thatwas being done at the time. It was an anarchic strip.

Syd Jordan.

Lance McLane was my favorite of Syds work, although hemade his name with Jeff Hawke. Jeff Hawke was aimed at anolder audience while I was still in my infancy. I caught on to JeffHawke later on. But Syd was often ghosted by other people Paul Neary drew some of the stuff for Syd, and since then theresquite a few other people I know who either helped Syd or filledin for him on the artwork side. But he had a vision of sciencefiction which I dont think Ive ever seen in comics. Id say evenwith Dan Dare and things like that, his vision was far morerealistic he was far more grounded in science and it had thisLovecraftian twist where there were dimensions to the alienspecies and to the cultures that the characters interacted withwhich were just very, very strange.

Since you have that connection to him through Paul Neary,have you ever met Syd and talked about art with him?

I met him a couple of times many, many years ago, but I cant claimto know him that well. I was fortunate enough to go into his studioand to see a lot of his work and listen to him talk about how heapproaches storytelling, but, no, I cant really claim to know him.

John M. Burns.

John M. Burns has been fairly prolific. Although the work of hiswhich I prefer most are his newspaper strips, he did a tremendous amount of work in kids comics and various otherthings over the years, in newspapers, magazines and hes justa phenomenal artist. I dont know what else I can really say.[laughter] His coloring is terrific. Hes done work for Europe Capitn Trueno. Ive never seen him anywhere else, outside ofEurope. Hes just very, very prolific and hes able to draw anything.

Does he stick mainly with newspaper strips or...?

No. I think it might be TV 21, he did some science-fiction strips for.I know he drew Doctor Who a long time ago, and he did anotherscience-fiction strip, but it was a long time ago and I dont haveany copies of it. Obviously, a lot of the British comics when I wasgrowing up were anthology titles, and what I would do was rip thepages of artwork out that I liked best, or the stories I liked best,and staple them together. But when you tend to do that, it meansthat you end up with a pile of ratty copies that are falling to pieces you dont keep them like you do comics that are complete.

Now for the one who had probably the biggest influenceon you, Frank Bellamy.

Frank Bellamy I knew because hed filled in for Frank Hampsonon Dan Dare. Hed also done the Thunderbirds strip, which hewas very well known for. Before that hed done work for Eagle -The Churchill Story, The Montgomery Story, Fraser in Africa,other things like that. But it was when I saw Garth that I reallyrecognized his ability, because one of the things about seeing anartists work in color is you can be dazzled by the technique in adifferent way so that you dont see the simplicity; its so clever,thats its almost too clever. But when you see an artist work inblack-&-white, and you know the limitations of black-&-white,and you see them go so far beyond what anyone else is able todo, you realize the ability in breaking the restrictions that otherartists acknowledge.

He influenced your take on Captain Britain as well. Can you go into that a little?

Well he wasnt really a big influence; it was more the characterof Garth. Id followed Garth before Frank Bellamy came ontothe strip, but Id never really liked it because I didnt like theartwork that much. But when Frank Bellamy took over Garth, Igot into the Garth character. He was a mix of James Bond, JohnCarter, and pretty much every other hero you can imagine rolledinto one. The way that Bellamy drew the strip, it just felt right.

Barry Windsor-Smith, or Barry Smith as he was knownwhen you first saw his work.

Well Barry Smith came quite late really. I think the first work Idseen of Barry Smith was when he was into his Kirby/Steranko-influenced stage when he first started working for Marvel. I dontknow if he did anything before then; Im certainly not aware ofanything. He was novel, because he was so different fromeveryone else you could see that he was doing the Americanstyle artwork, but it didnt quite fit. I really watched him growwhen he took on Conan and basically made Conan his own.

When you first saw his work, did you just assume he wasan American artist or were you aware he was British?

I dont remember. I just remember seeing the artwork andthinking, Some of this isnt very good, but theres somethinggoing on here thats exciting.

Obviously, you spent a lot of time as a child reading theBritish comics and newspaper strips, but you also saw a lotof American comics. They were very different in terms ofstyle and content. Do you think the American and Britishstyles of comics have become more similar over the years?

I think to a great extent comics have died out. They dont haveany individuality. I dont want to sound too depressing, becauseit is a quite depressing picture, but when I was younger, Britishcomics were anthology titles the ones that still exist are as well where you would get two- or three-page stories, and maybesix or seven of them in an issue. The very first comics that I sawwere mostly text and the comics were a very small part of them,so they were almost like serialized novels with a couple of comicstrips as well. As for the actual content, there werent any super-heroes per se, especially when I was younger there were warstories, historical stories, mythological, and sci-fi. In the warstories genre, youd have things like Captain Hurricane,Typhoon Tracy, and Braddock, who was a WW II pilot. With thehistorical stuff you had Heros the Spartan from Frank Bellamy,and the classic things like Robin Hood and King Arthur theywere always coming up. With the kids comics, you had thingslike football stories, athletes stories. Roy of the Rovers is oneof the big footballing characters over here hes almost iconic. Inever really got into football comics; I was never interested infootball. There were other things like Wilson, the GreatestAthlete, who trained on the moors and ran barefoot and won inthe Olympics and things like that. For kids characters therewere things like Billy the Cat, a school kid who decides to be asuper-hero dressed as a cat, but that came quite late on. Therewas General Jumbo, a kid who could control an army of toys he had a control device on his arm. There were The Cubites,which was basically just a gang of kids riding around on bikes.

There were things that might be recognized more as super-heroes: The Dollman, who Ive told you about before the guywho has the group of robots he controls and uses ventriloquism

-

alan davis true brit 107

to give them personalities and that was prettyfreaky. There was The Spider, who was verystrange he was sort of a super-villain whofought other super-villains. As always withthese things there was a lot of science fiction.The Iron Man was a particular favorite of mine.You basically had a robot who was a super-computer, super-strong android. The SteelClaw, had the guy with the artificial hand whobecame invisible except for the hand wheneverhe got an electrical shock. More recently when I say more recently, it was in my earlyteens, so its only more recently in a historicsense [laughter] there was one called TheMissing Link, which was about a caveman thatwas thawed out and turned out to be TheMissing Link. He was mutated and became asuper-hero called Johnny Future and was ina super-hero costume for a while. I wouldsay that he would have been the mostrecognizable as a super-hero. Therewere other interesting things wherethere were period super-heroes.Heros might fit into that slightly,but Janus Stark, who I supposewas a little bit like the characterin X-Files, in that he was able todistort his body and crawlthrough places, and he was aVictorian equivalent of Houdini.There was Adam Eternal, whowas cursed with immortality he actually travelled throughtime in the end, and they didsome interesting things withhim. But it was more bizarrestuff than what you wouldrecognize as part of a DCor Marvel universe.

Most of the diversityin American comicsfaded out over timeand tended to followtrends, but it soundsas though the Britishcomics really kept thatdiversity throughout.

I dont think it was a case oftrying to be diverse, because with Dan Darethere were imitators, like Jet Ace Logan,where as soon as youve got something thatssuccessful, everyone else will try to imitate it.There were always lots of robots - giant robots,alien robots, clunky robots, heroic robots.Robot Archie was a very successful strip not one that I particularly liked. There were alot of Tarzan-type characters, and there wereloads and loads of war comics and Westernstrips. I think the diversity came purelybecause there seemed to be a market for it.

Doctor WhoDoctor Who British Broadcasting Corporation

-

116 true brit ron embleton

Once out of the army, he set up astudio with several other tyroartists and quickly established

himself with publishers such asScion, Gerald D. Swan, DC

Thomson, and Fleetway. Muchof his work

in thisperiod waswesterns

(in such comicsas Comet, Hotspur,Dynamic Thrills, and

Mickey Mouse Weekly),drawn in a slick, smooth stylewhich was clearly influenced

by American comics. Embletonbegan to come into his own by

the mid-50s with yet morewesterns for Cowboy ComicsLibrary, Strongbow in Mickey

Mouse Weekly (from 54-59), andstrips in Super Detective. However, hisbreakthrough undoubtedly came withthe full-colour Wulf the Briton strip

in Express Weekly (one of the weeklies inspired by the Eagle, thepre-eminent comic of the 50s). Wulf was set in the time of theRoman conquest of Britain, and gave Embleton ample scope todevelop his painting skills and to reveal his seemingly effortlessmastery of the human form.

By the end of Wulfs run (57-59), themature Embleton style had emerged: anastonishingly realistic and detaileddrawing style married to a sophisticated,dramatic control of colour. He was fast,too. Invariably, it seemed as if nothing not even the most apocalyptic scene ofmassed armies in pitched battle fazedhim, and in addition to producing severalfully-painted comic-strip pages healways managed to find time tocontribute to numerous annuals,magazines and books. Wulf wasfollowed by a succession of war strips forthe renamed TV Express (60-61), YoungLorna Doone in Princess (62), and The

Wrath of the Gods for Boys World(63). The Michael Moorcock-

scripted Wrath of the Gods is widelyregarded as his masterpiece, though

1930-1988

Ron Embleton was one of the true giants of British comics and, along with theother artists of the big four (Frank Hampson, Frank Bellamy, and DonLawrence), did much to establish the adventure strip in the country. Embletonwas the first of the big four to become a professional at the precocious age of17 with strips for Scions Big series of comics. His budding career wasinterrupted a year later when he was called up for his period of National Service(Britains equivalent of the Draft), including a tour of duty (1948-1950) in Malaya.Ron

EMBLETONby David Roach

Stingray

Self-portrait Embleton Estate Wrath of Gods Respective Holders Stingray Carlton International Media Limited

-

128 true brit hunt emerson

If Leo Baxendale, the quintessential Britishmainstream bigfoot artist, could somehow havemated with brilliant American underground comixcartoonist Robert Crumb, such unholy spawn woulddoubtless resemble our next subject, Hunt Emerson.Though we Yanks tend to ignore any Brit comicsoutside of the pages of 2000 AD, Great Britain has itsown rich history of homegrown underground comix that is, non-mainstream, alternative funny-booksquite often focused on confessional tales of sex,drugs and rock n roll and Englands cartoonycomics, with its weekly episodes of (more oft thannot) the manic, bigfoot antics of anarchistic,

reprobate schoolchildren,have been wildly popularon the Isles since wellbefore World War Two.Hunt, it appears, iscomfortable straddlingboth indie and mainstreamcamps, and as youll findout momentarily he hasa fine grasp of the historyof British comics.

Newcastle-on-Tyne, which is northeast of England.

1952.

Yes, I guess so. Theclass distinctions, Im

sure you know, are very finely defined in England [laughter], andwe would probably be lower middle class. My dad was a radiooperator on weather ships, among other things, but that was hismain thing. And me mum, when I was small, she didnt work,and then later she was an office worker.

Two brothers.

No. Me mum wasslightly musical.

But no, it all came out in me and my brothers

Not particularly, no. I had an uncle whowas a very dynamic man and could kind

of do most things, including sketching and suchlike, butthat wasnt what he did. He didnt do it as a hobby oranything, it was just something he could do. But no, memums often wondered this. She doesnt know where it

came from, the fact that Ive got this art and me brothers, wereall musicians as well. We were always playing in bands together.Especially me and Norm, the elder of the two. We still playtogether when we get together.

Yes and no. Not a lot, but Icertainly do. Ive been in a band

well, there is a band, or there was a band, a couple of monthsago, which got together for a birthday party, actually for mypartner Janes birthday party, when she was 50. We put a bandtogether. And then we did another gig for somebody elsesbirthday party. Theres nothing else thats happened since then.

It was great. [laughter]

Guitar.

I like playing live. I dont mindwhat Im playing. [laughs] For

listening, I like country and western, Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris.

Its just something that I do. It was funny, actually, doing it withthis band what was it, two months ago now, three months ago at this birthday party, because it was actually a good stage anda good P.A., and we were doing tracks like Money and Mess ofthe Blues. Very rock and roll and R&B things. And I can really dothese, I can belt it out. But all of the people that I know inBirmingham have never seen me do this, cause I hadnt actuallydone it for years. So we did this gig and everybody was saying,I didnt know you could do that, thats fantastic! I said, Well, Ivealways been able to do this. Its just nobodys ever seen me doit. Because other times Ive always been playing country musicor traditional music, which isnt the same, you know. [laughs] I like rock and roll.

The first half of it was, yes. Then we moved to a place that was abit more urban. The first half was cornfields and, yeah, fantastic.

Well, Ive always drawn, since I could hold a pencil. I always didfunny drawings to amuse me classmates and things, but neverreally thought about it seriously. I knew that whatever I was

going to do, it was going to besomething to do with art, so whenit came time to choose collegeand things, I insisted in going toart college.

Hunt

EMERSONby Jon B. Cooke Transcribed by Steven Tice

Where are you originally from?

You were born when?

Did you have siblings?

What do you play?

What's your preference?

And when did you first start drawing?

So was it a pastoral kind of upbringing?

I would venture to guess that maybe 80% ofcartoonists would be terrified to be on stage.

Were your parents creative at all?

Any relatives?

Do you still play music today?

What kind of upbringing did you have?Was it working-class?

How'd it sound?

Hunt Emerson

-

And I did two years of preparation work in Newcastle, a two-yearcourse that was really more like an extension of high school.And then I came to Birmingham to do university well, theequivalent to a university degree in painting, but I was onlythere a few months and realized I didnt know what the hell I wasdoing, basically. Whatever I was, I wasnt an artist in that way. SoI quit that after a year, and that was when I started doing comicsand cartoons.

Yeah, everybody did. Beano and Dandy, Beezer,Topper, and things like that. I wasnt fanatical aboutthem, but yeah, all kids saw them; they were aroundthe place. I also used to see Mad when it waspublished as a comic book, except that I saw it in theBallantine paperback reprints, the ones you had toturn on the side to read. And they were an absoluterevelation. Id never seen anything like this before,and I was very, very interested in those.

Actually, I do! Which is quite unusual for me. [laughs]But yes, there was a time when, the first one I sawwas Utterly Mad, and some kid had brought it intoschool. I must have been about eight or nine. Andsome kid had brought it into school, and I rememberthere being a great pile of kids on the desk looking atthis thing, and my kind of glimpsing it from the back ofthis crowd of kids, sort of seeing what it was, andliterally fighting me way through to the front, becauseId never seen anything like it before.

Absolutely! I was totallyintrigued by it. And I didnt

see any more after that for quite a while, for maybe a year ormore. But then gradually I started to find out where they were,so I saw two or three of them. Of course, it was only later that Imanaged to get hold of a full set and all the rest of it. But the onethat first got me was G.I. Schmoe in Utterly Mad.

Yes, rather than the adventure strips, because we had two formsof comics in England at that time. There were the humor ones Beano, Dandy, Topper, and Beezer, and others like that and thenthere was Valiant, Hotspur, Victor, and other ones, which werebasically adventure strips. And I was never particularlyinterested in those ones. I always liked the funny stuff.

Oh, thats right, yes. Used to go on a Saturday morning to seeBatman and Zorro....

Yeah, I guess so... I never really thought about it. I dont know ifyou noticed, but Ive been working for the Beano now, you know?

For the last year Ive been drawing Little Plum,Your Red-skinned Chum. Although they dont

actually use the red-skinned chum line these days. [laughter]

Its great fun. I wish they paid more,cause they dont pay a lot, but its

actually great fun doing these. Im not writing them, the editorswriting them, sends me scripts. But its very good fun doing it.And its the most visible thing Ive ever done in the comics world.

No, I didnt realize there were any. [laughs]

When you were a child, did you regularlyread the British weeklies?

You know, I'm talking to a lot of Americanunderground comics artists, and for me I remember exactly where I was when I firstencountered the Ballantine paperbacks,because they just I mean, I had seen theSuper-Duper Man beforehand but justthought that was an anomaly. I had no ideathat Mad was comics. Do you have a distinctmemory of where you were?

And you must see it. [laughs]

Were you particularly attracted to the plethora of kidhumor material, like Leo Baxendale?

I dont know if this analogy is wrong, but it seems to methat I talk to a lot of British artists, they seem to almosthave the same experience in the 50s and early 60s that alot of American cartoonists and comics artists had in the30s: that a culture was being developed just for them.There was the growth of the weeklies with Frank Bellamyand the adventure stuff. There would actually be movieserials, right? When they were long gone in the United States,they were still going on strong in England, werent they?

hunt emerson true brit 129

Did you feel like you had your own little culture?

Are you?

How do you like it?

Did you have favorite cartoonists who worked in theBritish weeklies when you were

Hunt Emerson

-

dave gibbons true brit 141

David Chester Gibbons was born at Forest Gate Hospital inLondon, England, on April 14th of 1949 to Chester, a townplanner with architectural training, and Gladys, a secretary. Atthe age of seven he discovered Superman and was sooncompletely enraptured by the romanticism of the comic book,both British and American, like Mad and Eagle. Among thosethat whet his artistic eye from childhood were the elegant stylesof Wally Wood, Will Elder, Frank Bellamy, Jack Kirby and WillEisner. This self-taught artist spent much of his youth emulatingthe comics he cherished by often illustrating his own personalhumor strips before eventually breaking into the world of comicsfandom for fanzines like Rock & Roll Madness.

In his early 20s Gibbons became a building surveyor butmanaged gradually to break into the UK comics scene letteringmostly humor books for IPC. In time he scored more illustrationwork at DC Thomson where he would do adventure and sci-fistrips. By 1975, together with Brian Bolland, Dave worked onPowerman, a book designed and illustrated by both, for theNigerian marketplace. Shortly after, Gibbons put aside hissurveyor day job to solely focus on his career as a comic bookartist which was just beginning to take-off for the better.

With the arrival of 2000 AD a new exciting breed ofcomics were about to commence and Gibbons wasthere from the inception of the anthology comic. At2000 AD, he illustrated and wrote stories forHarlem Heroes, Dan Dare, Ro-Busters,Rogue Trooper, Judge Dredd, and various othershort stories. With his growing reputation andprofessionalism, his work became sought after bymost comic book companies including Marvel UKwhere he helmed a fondly remembered Doctor Whorun for many years.

Gibbons art finally made waves in the United Stateswhen DC recruited him to be at the art helm of GreenLantern, in 1982, and paired him with writer LenWein. He continued to work at 2000 AD whileexploring the rest of the DC universedoing covers and stories for almostevery DC character, from Batman toWonder Woman, at some point oranother. A major career highlight and one of his best experiences at DC was the tale, For the Man Who HasEverything, a quintessentialSuperman story written by AlanMoore and edited by the legendaryJulius Schwartz, the editor of manyof the comics the artist adored as achild. The arrival and success ofGibbons efforts in the States alongside those of Moore andBolland helped open the doors forthe avalanche of British talent thatwould follow in the coming years.Now triumphant on both sides of theAtlantic, the artist would soonconfront his biggest challenge inanother book with Alan Moore thatwould shake the foundation of thecomics industry.

Watchmen was the twelve-part maxi-series thattransformed the art form and captured unprecedentedaccolades from critics, comic fans, skeptics, and themainstream reading public. For the project the artist liberatedhimself from second-guessing what the American readingpublic wanted to see and constructed pages much the way hedid for 2000 AD. The series collected many awards and prizesfrom many literary circles including a prestigious Hugo Award in1988. With Watchmen Gibbons was able to push his storytellingabilities by experimenting with the design and mood of thishighly expressive work. From the unique symbolic covers to theintricate layout of his pages, the artist was able to tell a boldstory with complete and utter mastery of composition. The titleremains fondly remembered because it will forever stand as atestimony to the craftsmanship and application that serieswriter Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons injected into thiscomplex super-hero epic.

As if being one of comics most influential artistswasnt enough, Gibbons has also demonstrated that hes afabulous writer, having written Worlds Finest (with artist SteveRude), Captain America (with art ist Lee Weeks), and

Dave

GIBBONSby George Khoury

Rogue Trooper

Rogue Trooper Rebellion A/S

-

142 true brit dave gibbons

Batman Versus Predator (with art ist Andy Kubert). And onthe art front he has also continued to collaborate with the finestwriters in the field like Frank Miller (on the Martha Washingtonseries), Stan Lee (on DCs Just Imagine: Green Lantern) andHarvey Kurtzman (on Strange Adventures).

To this day Dave Gibbons remains as one of the most prominentnames within his field. The virtuoso continues to be a part of thekind of comics that are always adventurous and fun. Presently,the artist is at work on his largest and most ambitious project

since Watchmen: an original graphic novel named The Originalswhich is also written by him. Having spent the last two yearsworking on The Originals, it promises to be his most personaland most thought-provoking work, utilizing all of his storytellingand design skills to make it a truly unique effort.

Outside of comics, Dave has provided art for advertising clients,educational companies and designed various record covers. Hecontinues to live in England with his family.

(top) The Story So Far Dave Gibbons (lower) A.B.C. Warriors Rebellion A/S

-

We knowhowimportantan influenceAmericanartists like WallyWood and Will Eisner were to your career, so howimpactful were the works of British artists like Hampsonand Bellamy early on? Were there any other Englishartists whove inspired you as a professional?

Most British comics of the 50s and 60s were in black-and-whiteon really cheap paper, so the beautifully printed Eagle, whereHampson and Bellamys full-color work was mainly seen, wasan object of wonder. I loved the precision and detail of their workand their powerful storytelling.

Other artists whose work influenced me were Joe Colquhounwho drew World War II strips (and whose work I later ghosted atthe beginning of my career); Ron Embleton, whose beautiful full-color work appeared in many places and who ended up drawingWicked Wanda: Don Lawrence, of Trigan Empire and Stormfame; Ian Kennedy, who drew great aircraft strips; and RonTurner, who drew Rick Random, Space Detective. Turner washeavily influenced by American pulp illustrators like Ed Cartierand drew the best aliens and spaceships ever!

I also loved a lot of artists who turned out to be Italian, ratherthan British, notably Tacconi and Gino DAntonio, who drew forthe monthly War Picture Library series.

Were there any favorite British strips as you were growing up? Did you passionately pursue and collect them?Did your parents encourage your comics passion?

Ive mentioned a few of my favorites above. Hampson and, later,Bellamy drew Dan Dare. Bellamy was also responsible forHeros, the Spartan and, later, Thunderbirds. As for newspaperstrips, I loved Jeff Hawke, a science-fiction strip by Syd Jordanand Willie Patterson; I persuaded my parents to get the dailynewspaper it appeared in and would clip the strips out.

My dad had been a reader and collector of American SF pulps inthe 30s and drew cartoons himself as a boy. His parents had alodger in their house when my father was young, who drewillustrations for DC Thomson, the big Scottish comics publisher.I still have his paintbox, given to my dad, and inherited by me.

I remember my dad bringing home the first British edition ofMad, ostensibly for me, but I think he read every page, too! Ihave fond memories of him driving me around the localnewsstands to buy comics. My parents were a little lesssupportive of me drawing comics for a living, with good reason,given the alternatives that were open to me!

dave gibbons true brit 143

Top: Comicon 71 Dave Gibbons Above: Cyclops Marvel Characters, Inc.

-

156 true brit bryan hitch