TRADITIONAL ATHABA - ERIC · .traditional. Athabascan law waiys le: (1) failure to perceive the...

Transcript of TRADITIONAL ATHABA - ERIC · .traditional. Athabascan law waiys le: (1) failure to perceive the...

DOCUMENT RESUME' '

ED 110 259 RC 000 708

rs

,

A

AUTHOR - erc Arthur E.; Conn; StephenTITLE -. Traditional Athabascan 'Alf Ways and Their 17

Relationship toContemporary Problems of flp sh,,Justice " Some Preliminaty Observations on Structureand Fundtio.n. Institute of Social, Economiot,andGovernment Research (ISEGR) Occasional Papers No.7..

INSTITUTION Alaskapiv., Fairbanks. Inst. of Socialy Economic,and G ent Reserch:

REPORT NO ISEPUB DATE AuNOTE ,, 23p ava=ilable in hard copy'due to marginal

legi laity of original document'AVAILABLE FROM ute bfSocial, Economic andGov rnment

Re rch, University of Alaqka, Fairb s, Alaska01 ($1.15, Xerox copy)

. 1

MF-$0.7 PLUS POSTAGE. HC Not Available from E'D'F.S.DESCRIPTORS *Americ n Indians; Authoritarianism; Community

Attitu es; Cultural Awareness;, *Cultural Background;*Cultu e Conflict; Justice; *Laws; legal Problems;Police Cgamunity F,e4ationship; *Values ,

-77.IDENTIVIERS *Alaska Natives; Athabascans

EDRS PRICE

ABSTRACT. . ,

-Resdlution of conflicts and disputes in traditionalsocietyociety was based on assumption S that:' (1) thefauthority

of the leader was absolute, for as, representative of both village andvictim, he was limited oily by the fact' that the crime had to beserious enough for third loarty intervention and that severe Sanctions.demanded village consensus; (2) once called berfore the villageauthority, an individual was already determined'guilty; (3) the

' offender was called before the village authoiity to redress bothpublic and private wrongs via repentant reconciliation. Besides its

-authoritative character, Athabascan; law entailed flexibility anddeliberateness. ,Flexibility weS manifest in formal checks on the.chief_s authority and the personalistic nature of legal proceedings,while deliberateness Lifa's manifest`,in the lack of haste in thedecision making process: Among the modern day problems, posed by

i' .traditional Athabascan law waiys le: (1) failure to perceive thelegitimacy of white legal author y, (since such authdrity isdelegated to f'sgures of "low" status (2) lack of parallels among the

%.3lays'most frequ ntli invoked against Athabascans (drunkenness, pettyassult,' etc.); ) an impersonal vs a,personal justice; (4) anassumption of innocence rather-than guilt; (5) lack of parallels in..the,defendent/prosecutor prOcess; andi(6) abstract laws. (JC) I

CV

riC:1

co.,'

10.

CT?

-

/

U S. OEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EOUCATION A WELFARENATIONAL INSTITUTE OF

EDUCATIONTHIS DOCUAAENT HAS .BEEN REPROOUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVEO FROMTHE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN

. MIND IT POINIS OF VIEW OR OPINIONSSTATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF

.EOUCATION POSITION OR POLICY

15EGR OC'6ASIONAL. PAPERS

No. 7; A(49ist 67'2,O

(` -

Traditional .A-thabascan Law Ways.

and Their Re/ationship to Con-ternporaryPtobrns of "Bush justice" .

Sane Preliminary ObservatirsStructure and Fonda*

AMUR E. HIPPLERand

STEPHEN CONN

r-1

- lks-r(urE ce Ecohtivie.AHD criovERNMENT RESEARC4

tiNIVERSITI OF ALASKAFairbartity Ale*

??70/

ono2

t

ISE.GR" Occollao Econ

o Aul,hors-are ice

11.

Ptxpe.rs aria pot!>114,s8 he InstitOernic, and Governrnant tiewarcll, University- bcto deyelop theft. own ideas an Their awry

Soihen Con 15 an -attorney at law anitIL member of the }Jew. York.

. and,10tm )it, \*s. He mcetvecl his13. A. from Colgate University,

kro*I1 oluMbia University Sch6o1 of Law, end M.A. Ininteriva1/44na afkairs from Colombia F-4sool wf tnternatibnal 4tft-4irs.

ippler IS an associate PrOfeseor of itnthroPo logy at the

Univers't of _Alaska. 13e -a 13.A. 'and 'Ph.O. both ine,y from' the, University er Caliprnia,

'Preps on D'F' this )"apex was ,supported in park by the l.Y..5.,

DePa ent. Itielth, Education and WelOare, under Title 1 of tK

Higher duration Actof 1065,"and by Nationsi%caince., E-ounclatton

Grant No.- 6S-34321.0 amendment 3.. ;The paper slould not becons} .-resisreseritingqi-te opinions tor policy p1 any overnment

atone

'Prica 1.00

11 0

Yscier Fssc Drecior of the.1nst- itute

James 0, Babb/Jr., tch tor

TRADITIONAL ATHABAAND THEIR RELATIONSHIP

PROBLEMS OF "BU

Some Preliminary 0Structure and F

A

Arthur E. Hi

and

Stephen CI

0

a

I

TRADITIONAL/ATHABASCAN tAW:inies °

AND THEIR REtATIONSHIP TO CONTEIVOR,ARY'PROBL,EMS OF "BUSH JUSTICE"

ccSQMOreliminary Obsirvaitions on

/Structure and Ftmertion .

1Aihscl veitodicaltY\ y The instituemantlieseitrch, Univers of Alaska. ,

on ideas 'on their awry`

t law sr member of the Wu; Yerk,vecl his B. A:. f rt,ott Cesigate University,,

ity School of Law, and M.A. Inrnbia 'School thternational Afca'irs.

4,

ate profese.cir afc anthropology attheIds a 13.A. -and t'h.b. bath in

y tz eti(eity

supportea in part by theion aria Welfeareuncler Title 1 of the,and by NatiorraLSafince. Founclatton

ent 1. The paper sliould, not bepinioris 1r policy or an/ government

Victor FiscAlerillirector of the tostituteJmic O. ell?b, Jr., tailor

T)i)-1)2

by

Arthur. E. Hipple

, and

Stephen Conti

ond4' '

wed

I

O

Thi :tudy specifically avoids making concrete recOmmendationsen live.. intuitively obvious ones,_ which might. flow from our

olxelvatio, s and analsis, This is so because it is the -first of a 4partseries whiel will .include analysis of Eskimo law ways, an alternativeinterptrtat G n of our findingcand, finally, a systematic analysts of Bush.Ju:tici: Arlin nistration. In this final number of the series, a number ofconcretely s wcific and general recommendations for change , ormodification f the sysiem of Bush Justice,will be proposed. t

I

4' PREFACE

This paper is directed towardunderstanding of traditional law waysIndians and -of the present state of the"bush"--village Alaska. An outgrowthCotlference sponsored by the Alaska

ithary purpose is to help facili

ap opriate delivery and administrethnically distinct populations Alask

, Aside from that specific- purposcurrent growing interest among ethntraditional social -.organization technespecially in the area of dispute solviirecent years, Nader (19,65) 'edited '01.Anthropologist devoted Welk. to OfBohannon (1965), j-loebel (1965), Whwritten extensively in this field.

Studies of law ways almost unifordispute -solving and conflict resolutiowith social, cultural, and'economiC'-coyear:

-i (to, the ethnologist, law) . , . is not-a

but rather an integral.part of cult"living law," '-''created, and carriedparticular society, a social phenomeibecause of human action.

4 The scope, content, and meaning,'techniques of the law, are determinedthem. Thus, people_undergoing cultserious Problems in understanding corgi

are based on assumptions radically cliff,

ohls 1;laking concrete recommendations:s ones, which might flow from our.is so .because it is the first of a 4=part

sis of Eskimo law ways, an alternativend, finally, a systematic analysis of Bushfinal number of the series, a number ofral recommendations for change or'ush Justice will be propissed. .

onn5

.5

r-

PR ACE

:this paper is. dir.ected toward helping chieve,. a betterundekstanding of traditional 'lawi)ways,among aska's Athabascan

Indians and ofpthe present'state f the administ ation or law in the."bush"village Alaska. An outgrowth of the 1970 Bush Juitice

. Conference sponsored by the*Alaska Judicial Council. the paper's

primary purpose cis to help facilitate establishment of moreappropriate delivery and administration of legal ervices for

ethnically distinct populations,of Alaska.

Aside from that specifici purpose, the Paper also reflects thecurrent growing interest among ethnography's and others in the

traditional social organization techniques of primitive peoples,-

especially in the area of dispute solving and conflict resolution. In

recent years, Nader (1.965) edited an entire issue of the AmericanAnthropologist dev solely to this subject. Scholars such as,Bohannon. (1964, loebel (1965), Whiting (1965), and others have'

written extensively this field.

Studies of law ways almost unilbrmly suggest that techniques ofdispute solving and conflict resolution are inextricably intertwinedwith social, cultural, and ,economic conditions.' As Pospist noted this '

year:

(to the ethnologist, law) ... is not an autonomous institutionbut rather art integral part of culture ... his law is part of"living law,' created and carried on by' members of aparticular society, I social phenomenon that is ever chargingbecause of human action.. -

/,

I. ,

The scoK content, and meaning, as well as the administrativetechniques of the law, 'are determined by

change ma experienceby the.cultute that, develops

them. Thus, people ithdergoing cultserious; problems in understanding contemporary legal stems that

are based on assumptions radically different from those with which

they arc famili, Research that elucidates the traditional legalthought of goups undergoing change not only can make clearer thebasis of these misunderstandings, but also can provide valuableinsights in dealing with minority subcultures.

Jlowever, if each culture's law system were to be describedsoleb, in the terms of the culture studiedi(a so-called `.`emit" analysis,sut.14 as that proposed by Bohannon [19691), its lack ofcomparability to Euro-American law would be of little use tostudents of comparative law or to those concerned 'wi h theadministration of justice. The product would be an obscti,. studyunrelated to any othe'r. 'As Pospisl (1972:4) notes, quoting Ghrekmanand Ilotbel, it is ,necessitry;4 an

.d, in fact inevitable; to translate :./ .

traditional terms into those usable by persons accustomed to k..American jurisprudence.'

The authors of this paper are an anthropologist (Hippler) who. has spent five years studying Eskimos and Indians in Alaska, and anattorney (Conn) with cross- cultural experience .in Brazilian andNavajo law. This interdisciplinary collaboration was deemed: mostappropriate for such research since it would add twthe substantiveperspectives of law best develope by an.gforney those insights intothe unique character of the disti ct cultural group best provided byan anthropologist. Methods use jn the study include a revievil.,''Of theethnographic and other pertinent informatiob, lnterviews,;, withAlaska Natives in various communities,, and interviee_ andobservation of law enforcement, judieiaV; and legal paannel.

J v V,

servicing this population.4

t=4:.%

1":",

Appreciation is expressed to all 'those, especially the IsSijIlage.people, who have assisted in this work. .

August 1972

4*.

non7

Arthur E. RipplerStephei?'Conn

/

TRADITIONAL ATHABASAND,THEIR RELATIONSHIP

PROBLEMS Or PRU

Some Preliminary Obs;Structure and Fu

a

by

Arthur E. ippler and S,

INTRODUCTI

This paper analyzes Alaska Athabdiscusses discontinuities 'betweeAnglo-American law, which createAthabascans in their relationship toThese difficulties stein' not jr-om thsystem, but precisely from its existenintegrated into all aspects of ..AthabasSystem operated in such a way asassumptions about normative hehavdiscordant with contemporary law.

A number of -authors, chiefly 0(1959, 1965) have commented on eersystem/of law. Although their insightsbased most heavily upon recent reaboriginal Athabascan ltivv-wdys.1relevant to the Upper Tanana Indiaapplication to most of Alaska's Interid

+f ,/..

I .

. / ,. ,

Natives. Jaw W1This study, requested by:i ihe State J1

better understanding Alaska'"bush justice" in Alaska, and iil,the first in Ti-law ways now underway. To this end the vianthropologist and an attorney..}.1,:

n.8

fat elucidates the traditional legalange not only can make clearer thes, but also can provide valuableubc ul to rev.

law system were to1ineseribedstudied (a so-called "emit" analysis,I3ohannon (19691), its lack ofii law would be of little use tosir to those concerned with theroduct would be an obscure study(1972:4) notes, quoting Gluckmand in fart inevitable, to translate

sable by persons accustomed to

re an anthropologist (!-Tippler) wholinos and Indians in Alaska, and antural experience in Brazilian andy collaboration was deemed mostice it would add to the substantive -d by an attorney those insights intoet cultural group best provided byin the study include a review of the.ent information, interviews withz-ommunities, and interviews andat, judicial, and ' legal personnel

o all those, especially the village 'ork.

Arthur E. H' pierSteph Conn

4 i.

0

V

TRADITIONAL ATHABASCAN,. LAW vvt.Y3,,AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP- TO CONTEMPOPIARY

PROBLEMS OF "BUSH JUSTICE"

Some Preliminary Observations onStructure and Function

by

Arthur E. Hip ler and Stephen Conn

INTRODUCTION

This paper analyzes Al ska Athabascan aboriginal law ways anddiscusses discontinui.t'es between them and contemporaryAntlo-American law, w ich create some difficulties 'for manyAthabascans in their relationship to contemporary ,legal modesses.These difficulties stem n6t, from the lack of a traditiorial legalsystem, but precisely from existencein a form 'that was deeplyintegrated into all aspects of thabasean life. The traditional legalsystem operated in such a ay as to develop expectations andassumptions about normative behavior that in some Cases arediscordant' with contemporary law.'

. A number of authors, chiefly Osgood (1936) and *Kerman(1959, 1965) have commented on,certain aspects of the Athabascansystem of law. Although their insights lave been useful.-thiS paper isbased, most heavily upon,- recent rese ches by the authors intoaboriginal Athabascari law ways). The 'formation is: primarilyrelevant to the Upper .Tanana Indians . ugh. much: 'of it hasapblication to most of Alas a's In r Athabascan population. The

. .

i'This study, requested by the State Judicial Council, is for Mc purpose of

better understanding Alaskts,N ve law ways, toward the end ogimproving"bush justice" in Alaska;and is the trst in a series of studies of Alaska Nativelaw ways now andanthropologist and ani attorney,

.. cinn8

ay. To this enethe work has been done jointly by an9

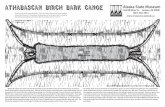

FIGURE 1*chiefly inheritance , . 'normal inheritance

(patrilineal) /A\ (matrilineal)

/ ,.< \\ A

elan A - clan B

A A0'

In this diagram, the triangles represent males,the circles females, and the

equal sign between them indicates a marriage. Lines descending from the

marriage show offspring. One can see that all children took the elan affiliation of

the mother, while the chieftainship, which went by patrilineal inheritance,

actuallx..alternated between clans and therefore moities.

the modal emotional Organization of the group's members. Thecritical issue of Athabascan emotional organization to an analysis2bf

law ways is the primary importanceylieed on control of emotionalimpulses. 'The :concern with internal individual controls tended_ tolead Athabascans toward a great need for balancing relationships and

\ obligations. _,TInts,, tendencies _toward explosively violent -emotions

\ were- defended against by reliance on external authority 4,least as\much as by reliance on internal controls.5

,This was expressed in two main ways. First was the PotIathh,a

pose-funeral Oft-giving ritual, through which the UppEtr tanana

5An explication either of . the modal emotional organization or the

methodology used to uncover it is beyond the scope of this paper and-will be ,

dealt with at length elsewhere. - , ..,

4

(inn9

Indians not only alleviated guilt anloved one, but also expressed aggressproFnoted pf4litical poiver.6. They alsoand `strengthen the balance of relatiokin groups.

emphasis on control ofinstitutionalized in the law waysandcareful deliberative techniques that tl

,of externalizing these controls wasabsolute power .in the chief: The needovercome fears' of einottonal disor'expressed in the attempt to inaintaireciprocal obligations between grouthe actual operation of the Iegal syste

Athabascan Law Ways Th

The ) resolution 'of conflicAthabascan society was .based uponprocesses which flow, from theseuniform for nearly all' Alaska Athafollows:

1. Within his sphere of colleader was viewed as ab.constraints upon that atoperate. -First, it was,limiteenough .to demand 'interauthority) who at the samwell-being of the 'village athe wrongdoing. Second,severe sanctions fo; p'authority depended ontechniques to mold vial

consensus of other villagtheir lineage: If the saneconsensus would 'extend tthrough clan relationships

/

N

6The authors are.presently, with Drdescribing, the psythological and social signi

A 5

10

E

normal inheritance(matrilineal)

/clan A clan

present males, the circles females, and the

a :marriage. Lines descending from the

that all children took the clan affiliation of

, which went by patrilineal inheritance,

therefore moities.

tion of the grOup's members. ThfLionel organization to an analysis ofnce placed on control of emotional .

ternal individual controls tended tot need for balancing relationships andoward explosively violent emotionsnce on external authority at least ascontrols.5

main ways. First was the potlatch, athrough which the Upper Tanana

e .modal emotional organization or the

beyond the scope of this paper and will be

4onn9

-^,Indians not only alleviated guilt and anxiety over tae death of a

loved ()lie, but also, expressed aggression and affillatioi) needsond

promoted political power.6,,Thky'also used the potlatch-to maintain

and strengthen the balance of relationships and obligatons,between

kin groups.

The emphasis on -control of emotional impulses was also

knstitutionalized in the law ways, and was manifestly expressed in the

careful deliberative techniques that they demanded. 'lite importance

Of externalizing these controls was 'emphasized in lhevesting of

wer in'the chibf. The need/or internal .psychic balance to

felirs of emotional disorOnization, which ,was overtly

in the attempt to maintain a balance -p1 .Aarmonious and

obligations between groups, was further ,demonstrated, in

ion orthe legal system.

abso uovercomeexpressedreciprothe actual opera

aAthaba can Law WaysThe Philosophical, aSis

.-+; r . J r ,

The resolUti n,, of conflicts' and disptites- in .aboriginal

AthabaKan society w s based upon three primary'asmnptiOns, The

processes which flow from -these assumptions were 4ppareritly

.uniform, for nearly all Alaska Athabasans, The' aSsamptions are as

follows:

1. Within his sphere of competency, the atithority, of tWleader was viewed as absolute. Ilowever, two kinds of .;constraints won that absolute authority .did in\ fact

operate. First,:it was limited to disputes eimsiciered Serious .

enough to demand intervention of a third party (Choauthority) who, at the same time represented the corporate

well -being of the village and the interests oft he victimof

Aire wrongdoing. Second, {in older to impok the most

%etpre ,sanctions Air particularly off nsive. acts, .thisauthority ,depended on the adroit us of conciliatory

techniques to mold village opinion a d achieve, a

consensus a other villagers respected s leitiders within

their lineage. If the sanction intended. vas warfare, this

consensus would extend to other powerf 1 persons linked

.. through clan relationships in neighboring lames:

-. .

6The4authors are presently, with Dr. rL. Bryce Boyer; preparing an article

describing the psychological and social significance of the potlatch.; '

5

044:111

2. To 1w called before the village's authority for_wrongdoing

implied that the authority had-reached a conclusion thatthe individual was "guilty." That is, his conduct was atvariance with widely recognized village norms that defined

"bad" public and private acts.7 ,

3. 'lila offender was called before the village authority for-;two reasons. First, he needed to be reconciled with thevillage through acts that demonstrated his sorrow for deeds

that had potentially clanked the baltince between lineagesih the community. Second, he had to make amends to theispecifiL Maim or victims of the wrong committed., Theawoblem before the authority, theretbre, was to find a justsolution to both the public and private wrongs inherent in

single act of misconduct.

The determination that the act in question was bad endligh to

warrant a hearing required that the authority apply village norniAofacts ascertained by him or his associates through investigation.8

However, the selection of a remedy to reconcile -the individual with

the village and to right the private injury was achieved during the

hearing through a conciliatory process:The outcome of the processof, ,reconciliation Was very much dependent- upon the state of

repentance of the wrongdoer.

k

li t.

e ,7"Bad acts" were th+ with concrete and ascertainable Consequences that

impaired private prhperly rights and viii6ge relationships. Thus, acts that might

be categorized as crimes for {the benefit of teaching youngsters abOut right and

-- wro ngtheft; slander, . ado' Illy, or murderwere categorized, only after

experience had .stiown that hey empirically impaired individual survival and,

more importa'nt'ly,' (he success' of 4e)operative work endeavors and

interrelationships of village life:\\

, 8Wrongful acts that involved such diverse activities as slander, theft, or'

adultery were described from Illestandpoint of injuries as property losses. Theasanction of remuneration far the victim in material terms/facilitated the .

resolution of private lisp tes with)solutions that, while huh, ere-lessstvere-------- .

*" in execution dr banish ndnt. The wrongdoer could also expect to lose his r i

public reputation for "rig it acting.". The implications of this loss in yeputation...,

in the many cooperativ endeavors of 91age life were that he might suffer,

additional .property loss A man ir,ho stole Might, be described as a thieftby

villagers for ten years aft r the act. r,

.

The Pragmatic Structureof Athabascan La

Besides its authoritative charadehad two other identifying characteristiand, all proceedings 'were deliberatedLit°, traditional law in two 'ways. Thechecks on the chief's ,authority andpersonalistic relations that characterize

The chief was the final authgrity.the chief was making a poor judgment.positipn of authority second only to ton the matter by one of the linenopenly state his disagreement. . Atconclude, that more deliberation 'Was t

brooked hi5.4cidgment in council, he ,v%)

important- reasons. A° chief who woawould soon find himself regarded ai."1

hard to ovetcorne, and Athabascans stTh eed to avoid a reputation fo,r Ii

existing ency for long and careful I

Personalistic rather than impzbetween the authority and the accuset

be/blind. In certain oases, even murdexample, the murderer was a "good irwho (very pertinently) had a large mattthis kind of political factor could lead

The system was deliberate in thatmatters were made in haste. Conmurder, deliberations might be co taDeliberation also entered t to

reintegration into the grout). A niconfessed thief would have to' bear 1

Fiffeptively;, this acted as arecidi ist during the probation periodoffenses taken into account during

offenses, however, would be given les

nap 'wrond acts. .

O

village's authority for wrongdoingrity had reached a conclusion thatilty." That is, his conduct was atcognized village norms that defined,e acts.?

d before the village authority orneeded to be reconciled with thedemonstrated his sorrow for'deedsmged the balance between lineagesnd,' he had to make amends to the

ens of the wrong committed. Thehority, therefore, was t9 find a justWe and private Vittotigs inherencinet.

act in 'question was bad enough tohe authority apply village norms to

associates through invvtigation,8dy to reconcile the individual withate injury,was achieved during theocess. The outcome of the processeh dependent upon the . state of

crete and ascertainable consequences thatllage relationships. Thus, acts that might

t of youngsters about rightanVmu erwer categorized only after

impaired individual survival and,of cooperative Work endeavors and

ii &Verse activities 'as slander, theft, 6rpoint I.:4f injuries at property losses. The

'Kim in, material terms' facilitated theutrons t t, while harsh, were less,severewrongdo r could also expect to lose hishe impli Lions of this loss in reputationf villag life were that he might-guffer

stole fight be described as a thief by

01

,

I

0

The PragMatic Structure and Operation-. of Athabaschn Law'llyayi

Besides its authoritative.,eharacter, tiVe Athabascan law system

had two other identifying characteristics.Thtlpv ways wer>i lexible,

and all proceedings were deliberate Flexi edict-0d,

into traditional law in vo .ways..'11 irideway was throu h formal

checks' n the chief's at thority ,and the second was through the

personal c relations th characterized the prciceedings.

The cbief was1ti> final authority. Nonetheless, if it was feft that

the chief 1..s making a poor judgment, the .ithellief.14.110 pccupired a

position of authority second only to theiehief, might be approached

on the matter. by one of the -lineage heads-rind would thereafter

ly s his disagreement. lit this i hoint, the chief lad toconclude that ore deliberatiiih was necoksary, because if s":Aneone

brooked nis j dgment, in council, he would only do so for extremely

import sons:- A chief who would ,ignore such a clear signal

would IP nd himself regarded as !OastY." Such ayeptitation was

hard to ove 'ome, and Athabascans strove to avoid- lacing so labeled.

e need t void a repjifation for hastiness added to the already

existing t r long and careful deliberation.

1

'Personalistic ratherthan 'impersonal 'relationships °existed

between the authority and the accused. Juste was'inIc*expected tb

..be blind. In certain cases, even murders.quld be oskrloolod if, forexam le, the Murderer was a "good man," an important.,,Moral man

who (very pertinently).had:a large matrilineal kin group, Overlooking

this kind of political factor could lead towar. . .

(flew wrong acts. z., .,. ,

..,.)

The system was deliberate\tn tiliat.no decisions about importc' 0

matters were :made in haste. Concerning critical is smell as

murder, delibergioris might be continued for as.long as five vars.

Deliber also. entered into the techniques for forgiveness a 4

. rei to ation into the group. ,A man who was=ia' S'cinvieted r

con eised thief would have t ear that stignia fleas long as-t nyears. Effectively, this acted , a:period of ,pwlsationLThat is, arecidivist during the probation, period ran the risk of haling Ills old

offenses taken into' account during his, iiew hearing; Very oldoffenses,.however, would 1:4e given less weight in later beatings about

Major Offenses'and Their Resolution

The interaction of the general principles of balance, flexibility,and deliberativeness with the absolute authority ,of the chief, thepresumed guilt of the accused, and the punishment throughrepentance and restitution can best be seen in a description of the

--resolution of specific antisocial acts.

Adultery !,

Adu ry %tt's considered to be a serious 'offense because. it couldlead tO Itolence, which was very ,dangerous becatise it strained theyfabric of mutual obligations and reciprocal-responsibilities that tiedtogether riot only kin goups,,,,Ipt communities. At its worst,adultery might lead to murder, the splitting up of a village, and hencewar hetween-Oillages.

Wheri adulterous acts wer2 brought to the attention of thechief, usually by the:, offended lineage heads, this ordinarily meantthat the lineage heads did clot believe the problem could be solved.outside of the council. Though bringing such an act to the attentionOf, the council brought shame on the offending matrilines, to ignorethe situation could result in potentially very dangerous and violentconsequences. Therefore, often both the offending matriline and theoffended matriline would conjointly bring the problem to the chief.9

The guilty ?individuals, without their spouses, were broughtbefore the %li and council to discuss their case. It-they chose todeny .guilt,Itt this first 'meeting, a second meeting was held with, the

.Spouses present. If-the adulterers still stubliornlY denied their guilt,the 'offended spouses and the council would tear their clothing fromthem and beat the offenders severely*. If, on the other hand, thertulty parties admitted Jiteir guilt at the,firstme/ting, they would bespared the geating,, but Nvould 'still be .subigct- rest of the

(S.san ons... .. ,. . .

'-. Ae-thiS,:- point,' 'the offending man 'would be- ordered to,remittierate theoffended hnsband. The husband was then permitted?to Ow a -formal warning' 'to the adulterer that if :the \ act '6:rere:rePeatecl; heliould kill the offender. This warning was given- before

. , .

matriline 'most offended was That of the victimliedihuibandilhOughAkhabasean women were by no means re,,ticertt and did not make life easyl4r a 'tying husband.

00 1, 3

c chief and , 'council and meant:111offender couy be undertaken with ittaken for his tkeath, and, even if lierecompense that his relatives_could_gsmall amount of "wergild" or death pa

If the adultery reisUlted in hiklb-tO the father's relatives fi*liphringing,mother's. clan., A hearing similar to tlheld before the chief, and tl guilty nfine (damages) to the husbandlifhis p

Theft

Theft was also a serious offense,circumstances such as hunger mightparty would bring the case to the -attecall both the complainant and (Wenthe lineage, heads. If the man adtnittmitigating circumstances, he would bhis actual damages, plus an additionalthief:s matriline was not expected toand indeed had a vested interest in ento prevent antagonisms from growinthief admitted his theft but had stoleneed, especially hung'er, he would be fibut his matriline would be expectedmorebver, would be shamed since it wknown about their lOsman's need and

. If a thief was either unrepentantwere no mitigating circumstances, hisIn addition to being forced to recombanished from the - village for from orecidivist would be absolutely' banishedso on ain of eath. Killing a banishptear r aliation and withoutrecomp nse a dead mart's relatives

6 'banish s nearly a capital punishAlaska is almost overwhelmingly difTanana band tended to distrusf.eachipby wandering hunter's if he. could notsatisfaction. Finally, athipf who-had

0014'

d Their Resolution

al principles of balance, flexibility,solute authority of the chief, the

d, and, the punishment throughest be ,seen in a description of thets.

e a serious offense becauset coulddangerous °because it strained the

reciprocal responsibilities that tiedbut :communities. At . its worst,splitting up of a village, and hence

brought to the attention of theneage heads, this ordinarily meantlieve the problem could be solvebx,ingirg such an act to the attentionthe offending 'matrilineS, to ignorentially very dangerous and violentth the offending matriline and thely bripg,the problem to the chief.9,

out their spouses, were broughtiscuss their case. If they chose to

second meeting was held with thestill stubbornly denied their guilt,nail would tear their clothing fromerely. If, on the other hand, the

.at the first meeting, they would betill be subject to the ;gst of the

ing man would be ordered toThe husband was then permitted

e adulterer that if the act wereer. This warning was given before

that of,the victimized husband; thougheticent and did not make life easy for a

1:

the chief and council and meant that the killing of the reilidivistoffender could be undertaken with impunity-No revenge lic.'uld betaken for his death, and, even if he were an important man,all ttrerecompense that his relatives could get from his death `<7.vas a verysmall amount of "wergild" or deatItpAyment.

If the adultery 'resulted in childbirth, the. child would be given,to the father's relatives for upbringing, eve(' though it balonged to itsmother's elan. A hearing similar to that described above would beheld before the chibl, and the guilty man would be forced to pay afine (damages) to husband' of his paramour:

0Theft

i

, theft was alio a serious offenk, bu one in w rich mitigatingi circumstances /such" as hunger might be4c. nsidered The offended

party would bijng the case to the atentioneof the c ief, who wouldcall both the complainant and defendant byfore hind irl council withthe _lineage heads. if Air man admitted his guilt and there were nomitigating cireunistanN, he would be made to pay the amount ofhis actual damages, plus an additional recompens to his victim. Thethief's matriline was riot expected to help him ith this obligationand indeed had a vested interest in enforcing the udgment in orderto prevent antagonisms from growing between kin groups. If thethief. ,admitted his theft but had stolen through the press of greatneed, especially hunger, he would be fined like the unmitigated thief,but his niatriline, would be expected, to assist his repaynient and,moreover, would be shamed since it was their responsibility to haveIcriocvn about their kinsman's need and to have assisted him.

. ... .. . ., .

If a thief was either unrepentant, denied his guilt, or if theres

were no mitigating circumstances, his- Punishment was more severe.In addition to being forced to recompense 'iris victim, he might bebanished from the village for from one to, several 'yea's:A chronicrecidivist would be absolutely'banished and, if he returned would do"so on pain of death. Killing a banished man could be done withoutfear of .. retaliation and without assuming the obligation torecompense a dead man's relatives. ,..It should be noted' thatbanishment was nearly a capital punishrnint. Living alone in InteriorAlaska is almost overwhelmingly difficult. Further, 'Sine LipnerTanana bandi tended to distrust each other, the exile might killedby wandering hunters if he could not account for himself to theirsatisfaction. Finally, a thief who had been banished and returned at

,

90014

f

s

, the end of his' sentence, and-who had paid recompense to litshadfaced the approximate ten year`: period of "probation."

1

Eyed* though borrowing and then "forgetting" to pay back ordAnging the borrowed goods Was not really considered theft,Athabascuns tended to, borrow only from matrilineal kinsmen toavoid inter -clan hostility. Nonetheless, the chronic borrower who wasslow to return things that. he had- borrowed from non-kin wastolerated and was not brought before the chief. He did, however, lose-considerable status because of thi weakness..a-

Murder..

fMtirderwas the most serio ,o 'crimes and could be AiunishecAf Wby death. There were various w t Alin which this problem might,' be

handled, .however. The Eomplaii4 tt, in a murder case were usupy.the ,matrilineal kinsmen of the vi .tim. The chief then either had to: -persuade the kinsmen of the victim to accept a death' pay ent fromthe killer, or persuade the kinsmt$1 pf the killer to accept he deathsentence.. If the matriline of the, victim were convinced to accept adeath payment after a hearing a which the murderer and variouswitnesses, if any, were beard, .tie matter ended lhere.1 A deathpayment would generally be acce ted if the victim was felt to haveprovoked the attack, or to have be n of Much lesSer importance thanhis killer. Among the consid4ations involved would . be theimportance and size of the matriline. Even if they wouldaccept the death penalty for o e Of their number, they mightbecome unfriendly to the complai ;ant group. In this event, a tensionand imbalance in the mutual ex ectations and obligatipns mightproi;e -disastrous fore the group. LE tie ,victim's matriline :demandedthe death penalty and the chief coneUrred, the murdereti.wasAilledby an executioner appointed' by ,the chief. Should ,the murderer <attempt to flee, he would be con. dered a fugitive and anyone-couldkill him .with impunity.

Complications occurred wh4n a "good" man (influential, wellthought of, and from a powerful! family) murdered a man of similarstature. In such a case, if the of ended matriline woulenot accept adeath payment, there was usual! no way for a death penalty to beenforced.. The offended matrili i,would i eel it could not ask for thedeath of a "good" man, and the offe ing matriline would notwillingly acquiesce in the ea, punishment of one of their

)15.

$

luminaries. At such an impasse,impending, and', once again,'theactive.1.0

The offended matriline would coheads 'in all of the surrounding villageintermittently for up to five years tobe initiated. Such a process realisticoffender and his victim were not only

J.different bands (villages), since the prso terrible that another solution to the

The clan's discussion about whe,several elements. There was alwaysintransigence of the parties to the dialter eiidaativ other than war would be foand ngers of war and subsequent redetail to deter those who demanded yen

,- If and when all the line:4e himports t men who were privy to thefavor of ar, the clan or the lineage hthis situa 'on 'would isq made war chiwould be There were no conscientWhen the ar chief called his men, a resummary, ca ital,' punishment. At thisstarted. Chie s and lineage heads woexercises; pratce wrestling, and weepdrilled in mane ver and fire tactics thatsurprise, and fir 4 power. Additionally, tllarrows. The chie and lineage heads wiwho would try to, void them. This traitits share of casualti and even fatalities.

A .date would beset for massing aunderstood anaceepte that some peo

the dispute would killed Thisflict. On the other hail memberithe village of the offe ders face

slaughtered as potential fifth co mnists

1 0In fiet it appears that all wars started to1

, 11

001-6

had paid recompense to his victim, -

ar period of "probation."

then "forgetting' to pay back orwas not really considered theft,only from matrilineal kinsmen toless, the chronic borrower who washad borrowed from nonkin Was

fore the chief: He did, however, loses weakness.

us of crimes and 'could be punisbecr-ayi in .which this problem might beants in a murder case were usually

victim. The chief then either.had ttini %o accept a death payment froen of the killer to accept the death

e victim were convinced to accept aat lifhialk the murderer arid variousthe matter ended' there.. A 'death

opted if the victim was felt to have

been. of much lesser importance thanderations involved' would be theler's matrilinet,,Even if they wouldone of them: number, they might

lainant 16':otrt,In this event, a tensionexpectations :and obligations mightIf the victim's matriline .demanded

f concurred, the murderer was killedby the chief. Should the murderernsidered a fugitive andnyone could.

hen a ",good" man (influential, wellul family) murdered a man of similarffended.matrairie wouldnot accept aly no. way for a death penalty, to be

ne would feel it could not ask for thethe 'offending matriline would notpital Punishment of one of their

4

luminaries. At such an bnliasse, all p arties realized war was

impendhig, and, once again, the del erative process b came,

active.10 .

The offended matriline would conta all of its majO family

heads in all of th surrounding villages. D tcussion 'would ontinue

intermittently for al) to'five years to deter ine whether w r should

be initiated. Such a process realistically o ,curred only then the'offender and his victim were not only 'from ifferent clans, but from

different bands (villages), since the prospect\ \of intravillage war was

so terrible that another solution to the eolith had o be found.

The clan's discussion about whether tseveral elements. There was always the hintransigence of the parties to the dispute"atternative other than war would befound. Thand dangers of war and subsequent retaliationdetail to deter those who demanded vengeance.

If :and when all the lineage heads in timportant. men who were privy to the discussion in

favor of war, the clan or the lineage, bead whose to

this situation would be made war chief and pre ,for war

would begin. There -were no conscientious objecto uch wars.

When the War chief called his men, a rental to coin met with

summary capital punishment. At this point;Tbasic training"' was,

started. Chiefs and lineage -heads would asOmble heir men, for /

exercises, practice wrestling; and weapons taining. The men were

drilled in maneuver and Tire tactics that primally emphasized stealth,

surprise, and firepower. Additionally, theme trained to dodge

arrows: The chief and lineage heads would fire arrows at the men',

who would try to avoid,tbern..:This training was expected to produce

its share of casualties and even fatalities.

wage war invorvede that in lime theould weaken and an

extr me difficultieswere pointed out in

,

and 'othnvincehad le

r,

A date would be set for massing and surprise attack. Everyone

understood and accepted that some people whowere actually, neutral

in the dispute would be killed. 'This would, of course, widen the

conflict:On the other hand, members of the offended lineage living,

in the village of the offenders, faced. the possibility of being

slaughtered as potential fifth coluninists. .

1°In fact it appears that anaifitarted this way.

11

001 6 .

'There was no simile Way out of such a war,,hich had the :aracter of a war of extermination. The wars ended with thestrurtion of one oranother'grouP, or -dragged onfo a generationd were finally abandoned-4ut of ,exhaustion. It, was for theseasons that war was feared, and every effort was made to avold'it.

Thus', Athabascan ,warfare was not a, randoM haphazard(Torrence, por- was it a spontaneous a-legal occurrence. It was'Minded, by rules.,and institutionalized. procedures. That is, war was

of simply the result of a Janie of legal organization; bid xather an .

int6g-ral part of the systerhi and the threat of war ..was a maiddet&rent: to murder: ,

Summary of Atliabascan Law Ways=

Froni the foregoing' brief overview, '-some aspects:61

thetic:Wm and function tit traditional Oithabascan Taw ways -seem:

Iran 'I'i4liaps most iinpAriantly`-the "Imi" was in no sense a thingapart from everyday lift. Law wits .StresSed. the- mztintenance ofharmonious relationship between the -matrilineal 'kin, groups. The

application of 'justice was to a'signifi cant degree dependent'upon theattitude of nialefaCtor, and the bent of the law was towardrecompense orvidtims and reintegration of the offender.

The chkf -ileterinin6d- the' resolution that a: Conflict or disputeshould have, taking into account the'deiree ot.guilt and repentanceof the wrongdoer, his position in society; and the likely aftereffects

f the judgment. 'Thus, the-chief balanced off the multiviried claims

f his's'Oaiety in thegiveniesuelir such a-way that the general social

()Oct was upheld: lie never;a4ed precipitthisly. 'i; -1

The iinplirtanCe- elihe'ration and, flexibility knot be :

verstated. 'Though the Chief w.tis_absolute in one senieethefragilityf The ,social order' Of, the band -Was such that he could notl,afford to

E di etitOr. Discussion Corisultation,ind.sloW,action Prevented

agmentation o t)ie" 'Small bands; which 'could have eritlangered,,etyOrie/S,surviral; pot- to - Mention the possibility of precipitating,

arfaret-

--di

th.en

.

Nonetheless, authority was vested in the chief. Indi,Vidualstivmferent.lineagekdidnot 'attempt to resolve serious disputes between

mselves, since such an attempts could precipitate 'feuding and

anger the caiefully -developed System of mutual obligations and

12

\,

reciprocal expectations. Disputants I

objective authority, and, to provenaccept that authority as absolute.

The chief, however, acted inimportant men in the community, wl

reached actually was an expression ocouched in terms of the chief's absundertaken actually had. the unassaila

:members of the community.

In structural terms, the admimaintenance of the balanced -ielatiowithin a community were the same thnormative, was concrete in the sontaken against an' abstract code based

.of right and wrong, but, rather, they-important network of obligations' a'Athabascan society. f s

-

7 '

However, even though theapplication of the law, judgments werThere Was in fact the intention -of unthe legal authority rested upOn assuthe rights and duties of the partiactually part Of the universal applica

Overall, glen, Athaba can law"which the AthAbascans int ated inthe need for controls and b lacr,and social structural realities, uc asand fragmented residence pat ms,system for the resolution o theinevitable among human beings.

t

Law Wa s and C

At present, Athabascins litraditional power is no longer obvioand is lo longer absolute. The authin the ,lAnds of state troopers an

13"

{1,9,

out of such a war, which had thenation. The wars ended with theoup, or dragged on for a generation

of exhaustion. lb was for' thesevery effort was made to avoid it.

was not a random haphazardtaneous a-legal occurrence. It wasalined procedures. That is, war wasof legal organizationbut rather and the 'threat. 9f war was a major

abascan Law Ways

f Overview, some aspects of theitional Athabascan law way's seem, the "ldv" was in. no sense a thingways stressed the maintenance ofen theiatriliinal kit) *scups. Thegnificantdeltree dependdnt upon the the bent 'pi the lap was towardgationlor the offender.

,resolution that a conflict or disputethe degree. of guilt and repentancesociety,, and the likely. aftereffects

f balanced off the multivaried claimsin such a way that thp general socialprecipito?ly.

ation ail flexibility. Cannot beabsolute tn one senserthe fragility

was such that he could not'afford to-ultation, and slow-actioir'prev,entesinds, which could.-have endanbrettion the possibility Of precipitating

t

vested in the chief. Individuals fromt to resolve serious disputes 'betweenmpt eould precipitate feuding andd system of mutual obligations and

20(11,7

reciprocal eicpe4tattions.ollistiutanCs had td rely .on a supposedly

-objective a hotity.4,:,ank to prevent continuing conflid; had to

ac_cept-that- riikai'itiolute.,';'Lt:

The "Chletfhoweyer--,., acted lit. conlection with the other

Important iinen.iir;:the community, ,AV.hich 004 that a decision once

reached, actually was an'expression of ,c,diornAlty consensus. While

couched' in''tenns of the chief's -absolute atith'ority. any sanctionsundertakpi-actually had the unassailable support of ali the dominant

membeis 'of thgeommunity... .

+.,

-In structilial termS,, -- the. Achill n istration of jasytice and themain4,enanee -Of the balanced _relationships between kin groups and ,

withiii:a community were:the same thing. The law, though abstractly' .

n kinatfve,,,was' co, in the sense "that - offeoses were not acts

laketirlig(111§(a)) listiract code based upiiii philosophical distinctions

of ,right-10-4:-* n ''''':.',.tathe'r, they were acts that endangered theimportant Oticit ':-.4*-obligations and expectationkthzt made upAthabascan iiiele gy''''' '

.S.- ( _

. if:. -..1,...T....i..._

-4.- -V.A.i'n

Ho *eyer;-- 0.041:. though the foregoing suggests cc; iyocal

application of the': a*, judgments' were not Meant to be made cl hoc:There was in fact- 4-intention of universal application. Decisions of

the legal ,.authority acted upon assumption's of obit:641A", in which'

the rights and :dill( of -the- parties were defined. The variance was

actually. parr C, I the,A iversal application rule..

,

.-- Olierall, heri thabascan 'law waYs reflected the manner inwhich the 'Atha-bacihs integrated. internal, psychic needs, especially

. ,,_ - - .- . , -the 'need for Controls and-balance, with the press of environmental .

and social strtiiittircuealities such as their impoverished environmenti .1 , _ '- -

s. - -and-fragmented restilence.patterns,:to provide a balanced deliberate.1-... ., . - ...

- system, for ihe resolution -the conflicts and disputes that are.

or'inevitable ainonghuinan beings.

I I ;

j

Days

At present; Athabtraditional/pover is no Ion

.and is/nolonger abso te.

, ,- -in the hands if state troo

and Culture Change

ns live 'in communities :in whichobviously legitimated by lineage headsauthority for law, enfoicement is now

and city police. The institutio

tr)- -

, 1

torganization andfinuch of the emotional commitment to traditional-law ways has disappeared, since the chief no longer can imposesanctions, except in his role as-village leader, in which he can play

,upon special rtttionships or duties conferred on him by lawV enforcement of icers. State troopers, who must travel to villages

when crimes arc* reported, often inforMally select the v. age chief to;notify the troopers of crimes' and to sign criminal mplaints. The

; chit,: may then achieve status as a dispute resolver a d judge by usinghis option of) notifying the authorities as leverage in seekingreconciliation, :'or even in imposing a sanction, when both thewrongdoer and victim are convinced that a ready solutio.n ,to thedispute within the village is preferable to. an a st and conviction in

rthe'- magistrate's court. This manipulation of 'nformally derived7 power as a_ lingering threat is a faint replica:of he use of possible

intervention by the chief in earlier times to encourage individuals ortheir families to reConcile their differences.

.L

-c there are, however, other ways in which the old pfstenicontinues to have an impact on modern perception of law and legalprOess. Present.day 20-year-olds have grantl_parents who lived underthe old sygem. Their emotional expectations toward the presentjudicial system appear to reflect a transfer of attitudes from the older

system.

Past and. Present Law Ways:Some Disjunctions

Athabasetuls often fail to perceive the legitimaey.atidrationality.of white legal.atithority. * the standards j6 which.theyradhere, thislegal authority is irrationally delegated to figures of- lois encl.::queitionable status (village police, magistrates,,and troopers). Policeand magistrates perform in a manner that appears to 13e arbitrary-andcapricious when _Compared to the . manner in which traditionalAthabascan authority reviewed the,eircumstanCes.. og the offense And

character ?f One offinder with nearly. excessive care. That care wasdirected ton the issue of what outcome wou14_selve.to'reconstitutethe balance, betWeen lineages *and the victim Throagh-ponipensationTor the victim's injury'and an admission of guilkandreptance. . .

. .

That theforces.of taw and r are hea'dquartered distant from

the -village,and its personali laga relationships reinforces theimpression hat",the state legal system - responds arbitrarily to crime at

the bush lei/el. The authorities show little concern for remuneration#

00 1 ,9c

L.

of the victim of criminal acts, leaving fa

for damages. This heightens the auththe eyes of the :Athabascan. In thesentence, the judiciary seems to care ,f

its intent to punish. Lack of concernrelationship with the village, his victiconfusing fact of contemporary Amwho experience it in "the bush."

Secondly, the laws for whichthemselves called to accountpublicdisorderly conductdo not have esociety. Indians do not take these minthey do not inconvenience anyone. Tsuch behavior

ofbewildering and it

consequences of the supposed bad act ithe results of the criminal Process.

A third problem arises from thjudicial process and the participantscourt's aynamics'aie striking if compelAthabascan. For example, in contetemphasis is placed upon the adversaiconflict between the parties and theboth sides of the issue of innoceinonliability, will be presented beforeis conflict between the defendant andencouraged. Nothing like this existed I

was no such thing as a-defense attornel

Next, the judge is not personallyhe already privy to the detail's of thegossip .about the, defendant,'butinadmissible. Authority in court isaccustomed to the idea of personalassumed guilty, but innocent. The errguilt, although the state hai takedefendant. Thus, in a criminal case;circumstances of arrest, as well asdetermine whether 'the agencies of,properly and whether procedural safethe defendant to ensure that a true tdefendant

and prosecution will take plan

15

0 0 20

,/-

aloha! commitment to traditionalthe chief no longer can iMpote

Wage leader, inlwhich he can playuties conferred; oif him by lawpers, who must travel to villages

*liformally select the village chief tod to sign criminal complaints. Thedispute resolver arid judge br_usinguthorities as leverage in seeking

ing a sanction, when both theneed that a ready solution to' theruble to ,an arrest and 'conviction inanipulatiOn of *informally derivedfaint replica of the use of possibleer times to encourage individuals orfferences.

ways in which the old - systemmodern perception'of law and regal

have grandparents who lived under1 expectations f toward the presenttransfer of attitudes from the older

ent Caw Waysisjunctions

rceive the legitimacy and rationalitystandards to Which they adhere, thisdelegated to:i, figures of low ande, magistrates,, and troopers). Policerider that appears ta.be arbitrary andthe manner which traditionale circumstances of the offense and

nearly excessive care. That care wasutcome, would serve Co reconstituted the victim through compensation'Won of. guil t:and repentance.

order are headquartered distant from.'village relationships reinforces thestem responds arbitrarily to crime athow little concern for remuneration

1-1n19

of the victim of criminal acts, leaving that for a separate civil prOce.ss

for damages. This heightens the authorities' evident irrationality in

the eyes of the Athabascan. In the court's levy of a fine or jail

sentence, the judiciary seems to care for nothing more than forni in

its intent to punishLack of concern for the wrongdoer's,continuing

relationship with the village, his victim, and the victim's telatives is a

confusing fact of contemporary American justice for AthabaScans

who experience it in "the bush.

Secohdly, the laws for which Atl a msc 1s most often find

themselves called to account -public drunke , petty assault, and

disorderly conductdo net have exact diets in Athabascansociety. Indians do not take these minor disorders seriously as long as

they do not inconvenience an ne. To be arrested and detained for

such behavior is bewilder g an. infuriating, especially when the

consequences of the supp sed bud ac ay little or no part in guiding

the results of the criminal process.

A. third problem aris m e I diahs' perception of the

judicial process and the participan t. Certain aspects of the

court's dynamicsere striking if compared with the expectations of an

Athabaican. For example, in contemporary Anicrin law, greatemphasis is placed upon the adversary system. Out of a symbolic

conflict between the parties and 'their attorneys, it is assumed that

both sides of the issue of innocence or guilt, of liability or

nonliability, will be presented before a decision is reached. Not only

is conflict between the defendant and prosecutor perniitted, but it is

. encouraged. Nothing like this existed in Athabascanlaw, where there

wasno such thing as a defense attorney.

Next, the judge is not personally engaged in the pr blem, no is

he already privy to the details of the dispute. He does of seek out

gossip about the defendant, but dismisses this as hoa y and asinadmissible. Authority in court is strangely. impels() to oneaccustomed to the idea of personal justice. The defers anp is not

assumed guilty, but innocent: The arrest is not sufficient vidence of4,-

guilt, although* the state h taken serious action a ainst thedefendant. Thus, in, a criminal case; \ the court will even review the;circumstances of arrest, as well as the act complained' adetermine whether the agencies of `law enforcement ha e actedproperly and whether procedural safeguards have been pies rvefOrthe defendant to ensure that a true test pf both the pcisitio s of thedefense and prosecution will takplaqe:

15

0020

^-4

' The trial itself places the initial_ of proof upon the#iprosecution, the representative of ?fie stale. Official conduct in 4pursuit of evidence for the proseculion-is examined, Should thatconduct be found to be faulty, the lfate's evidence will be excludedin whole or in part by the judicialSpresentative of the state: Thecourt may even be impelled to stYp further consideration of thealleged criminal act and to dismiss c case, These conflicts betvieendifferent officers of the white an's-Jaw, and the fact that'procedural /details can overwhel -iiibstang of a -case, areinexplicable to qne who presumes: tieiligcalICI before authoritymeans that the fact. of guilt has alrifti bee 'established,

The defendant has. the' 14 to stand mute- in theproceedings, .and to examine the eyOence of prosecution and officialconduct .with respect to him. Tis is quite different' from thetraditional notion of meekly confesing and accepting punishment.Since_ his .guilt in the eyes of- the Afpority figures in the court mayseem to the clefendantto he a foregone conclusion, and since he .doesnot understand adversarial dynarn a ingful consideration andwaiver or assertion of his rig( is . 'cult. The''Athabascandefendant may be reluctant to c lenge autlyrity since he cannotsee that it is in his interest to re staments :fif the Police. If heshould plead hunger or poverty, will:find to htt surPrise that thisis not very often cOnsidered mitig

The Athabascan deftndanverdict of inilocent will be the resmollify the authority figures by atheir anger. Effectively, thisobstruct the official inquiry. Thmlie attempts ti) extricate himselffrom the criminal process by thelraditional and expedient means ofageeing ,Nyith everything, waive his rights, and assuming thatwhatever the judge metes out as. i! ± ishment will be just. _

4E4A

linbly does not expect that aof the proCeedings. His dm is toeing-with them and thu's appeases . he will waive his rights to

. Local, magistrates, who aresystem 'to bush Alaskans, are ofthe correctional process and thThey ase often motivated in thconsiderations or, in some eases,

,born out ofrelii,fious or racialcourts sometimes consult beforabout the defendant's potentiofficial .eannot ordinarily provdefendant, and at. the Same tim

\4?

nient of the judicial 'tr ed in the workings of

iO4 thab underlie them.agistrial actions by local political

y, personal notions of pUnishment(or self- hatred). Although,higher

nteneing with correctional officersor Wolin,- even the most sensitive

for the ,needi of the indiVitial.''S village, add the legal system.

0 A

i 'I"

The court system's punishments adefendant who expects that' they .witrclationQips, assuage personal feelings;.in :the community, 'The severity ofreceives' may at times' be related to tlsorrow or guilt, but the court will usualthat lie recompenses his viiim or

- sentence tends to strike against the conare dependent upon the wrongdeet. for

Fines are an abstract payment tand Jail sentences are a strangely elkbanishment. Formerly inflicted -for ocommitted by unrepentant offenderoutine through the imposition of jailwho are arrested by ' state troopersmagistrate's court Modern day banishalso considerably, easant, since the jmeals. ".(

Although the typical Athabascanof white authority or the appropriate'him o/it-as a malefactor and imposiicannot :escapee its power. Absolute awell understands. The fact that he is oguilty according to laws. he evidently doften- confused by. ,the denouementrecenciled Bah' anyone and he recompdoes not 'M The crime as he- understanleaves the encounter in the belief thatthe victim ,of ,a crime, is to avoid the 1may well Teel that there is no juitice,is most comforlable would be connsociety. A

4 .

rr,Vt-

nitial burden of proOf. upon the --f the state. Official, conduct inecution is examined. Should that

state's evidence will be excludedrepresentative of the state. The

step, further' consideration of the,. .tl e case. These conflicts betweenm n's law, and the fact- that

m tl e substance of aH case, arethat eing called before authorityady been established:

'al right to stand .mute in thevidence o prosecution and official'his is q 1,e different from thekissing and accepting punishment.uthority, fi res in the court maygone conclus on, and sincecs, a meanin ul consideratio andis is difficul The 'Athabascanallenge autho tinge he ,cannotto statements the police. If hee will- End to hi surprise that thisUlt.:- A

t t

probabIS, dpes inotIt of the proceedineeing 'with them anans he will waive, he attempts to extrtraditional,and expedieg his rights, and- assnishment will be just.

expect that a. His aim is tothus, appeaseis 'rights toate himselft means of

ing that

e main embodiment of th judicialpoorly. trained :in the wo ings Of .

social theories that underli: them.magistrial actions by localy personal ,notions of punish ent(or self hatred). Although hi a er

ntencirigifsvvith. correctional offiers,or reform, even the most sensiti e

for the needs of the indiyliaus village, and thdlegal system.

21

.

The ourt system's putiishments appear pointlessly abstract to ae ec nt ,,,who expects that they will be designed to reconstruct

relationshinsl.assuage personal frelings and reestablish his reputationin the severity of the sentence the defendantreceives ,may it dines be related to the defendant's expressions ofsorrow`gr guilt, but the court %rill usually make no attempt to insurethat he recompenses his victim or his community. In bet, thesentence tc.,n, to strike against the community, especially those who

are deptendeptupon the wrongdoer for sustenance.-.t

-Mips' are an abstract payment to a faceless public authority,,

and ..jak sentenctis are strangely istorted version -of traditional_banishment: Formerly inflicted or nly, the Most serious,' crimescommitted by unrepentant enders, banishinerit has becomeroutine through the imposition jail sentences On most defendantswho are arrested by, state tro ers and processed -through themagistrate's court. Modern day ham merit is'exiot only routine, butalso considerably pleasant, since the ail is warn and serves regularmeals.

. -cp

Although the typitml ,A thabascan may questiiin the legitimacyOf vvhite, authority or the appropriateness of its response in singling-

*him out as a. malefactor and imposing punishmenki' pan him, he,cannot °escape- its Mower. Absolute authority is something that hewell' understands. The fact tha he is on` trial makes,,hirn assume he is

-.. guilty according to laws'he evidently does not,understand. Yet, he isoften .sonfuseid",by the denouement of the 04r:because he is not

;T.. . reconciled with anyone and he recompenses neone. Me punishment

does. not fit the crime as he understands crime:and punishment. Heleaves. the encounter in the belief that the best tiling to do, if he is

' the' victim of 'a crime, is..to avoid., the legal proceSS. As defendant, hemay well feel did there is,frb justice, siricelhe fuStiCe- with which heis most comfortable woUld'Ibe connected with his .role in villagesociety. 0,

cit)?.2.7

MS,

v

REFERENCES

Bohannon, Paul J., "The Differing Realms of the Law," AmericanAnthropologist Vol. (67, No., 6, Pt. 2, December 1965, pp.

33 -42.

--.---; "Ethnography and Comparison in Legal Anthropology," inLaw in Culture and (Society Laura Nader (ed.), Chicago: Aldine

IA Publi'Shing Co., 1969, pp. 40-,418.,t) its..

( -I.

. . . Hoebel, E., Adamson, "Fundamental Cultural Postulates and Judicial'.Law Making in Paldstan," American Anthropologist, Vol. 67,

No. 6, Pt. 2, December 1965, pp. 43.56.s

McKeniian, Robert A., The _Upper 'Tanana Indians, Yale UniversityPublications in Anthrdporogy No. New Haven: rat*University Press, 1959.

, The Chandalar Kutchin, Arctic Institute of North America,Technical Paper No. 17, Montreal: Arctic Institute sif No11America, 1965.

Nader, Laura, The Ethnography of Law, American AnthropologistVol. 67, No. 6, Pt. 2, December 1965.

a/

Osgood, Cornelius, Contributions to the Ethnography of theKutchin, Yale Uniiiersity Publications in Anthropology No. 14,New Haven: Yale University Pres-54936-

Pospisl, Leopold, The Ethnography of Law, Addison-Wesley ModularPublication 12, New 'York: Addison-Wesley PublishingCompany, Inc., 1972.

Whiting, Beatrice B., "Sex Identity Conflict 'and PhySical Violence,"

. American Anthropologist Vol. 67, No. 6, Pt. 2, December 1965,---:---

pp. 123-140. ,, e.

19-

0023

.5;