Towards a Critical Geography

description

Transcript of Towards a Critical Geography

-

. . . [A]rchitecture, even when pluralistic, is never enough. It is no answer to the lackof effective political pluralism . . . Architecture can accomplish much by acceptingand celebrating heterogeneity, but it is no substitute for a better politics, economicopportunities and community cohesion.1

ven before its huge glass doors opened to the public in June 1995,Vancouvers newest civic landmark was embroiled in public debate. In plan-

ning the new Vancouver Public Library building, city officials intended the $110million complex to be a proud symbol of Vancouvers self-proclaimed status asa global city.2 The city is changing fast. Thirty years ago it was a broad-shoul-dered resource centre dominated by the docks, saw mills and factories throughwhich the raw materials of Canadas interior passed on their way to world (andespecially US) markets. Now the city is a financial services centre and Canadas

Ecumene 2001 8 (1) 0967-4608(01)EU207OA 2001 Arnold

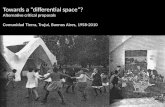

TOWARDS A CRITICALGEOGRAPHY OF ARCHITECTURE:

THE CASE OF AN ERSATZCOLOSSEUM

Loretta Lees

This paper argues that an architectural geography should be about more than justrepresentation. For both as a practice and a product architecture is performative in the sensethat it involves ongoing social practices through which space is continually shaped and inhab-ited. I examine previous geographies of architecture from the Berkeley School to politicalsemiotics, and argue that geographers have had relatively little to say about the practical andaffective or nonrepresentational import of architecture. I use the controversy overVancouvers new Public Library building as a springboard for considering how we mightconceive of a more critical and politically progressive geography of architecture. The librarysColosseum design recalls the origins of western civilization, and is seen by someVancouverites to be an insensitive representation of a multicultural city of the Pacific. I seekto push geographers beyond this contemplative framing of architectural form towards a moreactive and embodied engagement with the lived building.

E

-

multicultural gateway to the Pacific Rim, and what many believe will be a newPacific century.3 In this time of change Vancouvers leading architectural criticRobin Ward was not alone in hoping that the construction of a new publiclibrary was an opportunity to design a landmark for the twenty-first-centuryfuture of a progressive, environmentally sensitive and cosmopolitan Pacific Rimmetropolis.4

The City Council chose a peculiar design for the task: a nine-storey swirl ofglass and reddish-brown granite (Figure 1) that resembles the ruins of theColosseum in Rome. Its oval shape, open, see-through arcade at the top of thebuilding, paired columns on the facade, arched openings, buff-coloured sand-stone-like concrete and monumental scale all mark the resemblance. The visualeffect is stunning: an oval ruin from antiquity in a sea of glistening towers framedby mountains and the Pacific.5 Whether you love it or hate it, theres no mis-taking it, noted a columnist for the Vancouver sun. When you go in, straight-away, you give the big building a once-over. You cant help it. Its a monument,a landmark, an event. So huge and distinctive with its Colosseum-like tiers ofcolumns that you cant ignore it.6

As a symbol and civic landmark the public library has sparked extensive dis-cussion and debate. Local architectural critic Robin Ward cheered its architectMoshe Safdie for understanding Vancouvers essentially wacky personality andsens[ing] that the local political climate would favour his brash billboard styleof design.7 In contrast to Wards upbeat response, others have objected stri-dently to the symbolism of the Colosseum design. Take, for example, thiscomment from a letter to the Vancouver sun: that the Colosseum design recallsthe origins of Western civilization is an insensitive, retrogressive view of a cityof the Pacific and its multicultural mix.8 While some charged Eurocentrism,others complained about the inauthenticity of a design not obviously rooted in

52 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

Figure 1 ~ The Colosseum-like facade of Vancouvers newest civic landmark

-

the local traditions of the city, and even that the playful style and shopping mall-like interior arcade turned an important civic institution into a Disneyesquetheme park.

In this essay, I use the controversy over Vancouvers new public library build-ing as a springboard for considering how we might conceive of a more criticaland politically progressive geography of architecture. A dozen years ago, JonGoss claimed that geography has generally failed to come to terms with thecomplexity of architectural form and meaning.9 Since Gosss manifesto therehas been an explosion of new work by cultural geographers interpreting themeanings of the built environment and of landscapes more generally. In a worldof rapidly accelerating global flows, architecture is an important way of anchor-ing identities and of constructing, in the most literal sense, a material connec-tion between people and places, often through appeals to history. Recent workin cultural geography has concerned itself, in particular, with the contestedmeaning of history and its representation in the built environment. As thedebate over the symbolism of the public library design demonstrates, the cul-tural and symbolic are also deeply political, and a critical geography of archi-tecture must be sensitive to their contested meanings.

In the pages that follow I pay considerable attention to the politics of archi-tectural interpretation surrounding Vancouvers newest civic landmark. The pub-lic debate over the library design opens important questions about the properform, function and meaning of civic architecture in a multicultural city. But Iwant to argue that, while this attention to meaning is clearly necessary, it is byno means sufficient for a truly critical geography of architecture. Architectureis about more than just representation. Both as a practice and a product, it isperformative, in the sense that it involves ongoing social practices through whichspace is continually shaped and inhabited. Indeed, as the urban historianDolores Hayden argues, the use and occupancy of the built environment is asimportant as its form and figuration.10 And yet in their focus on the symbolicmeaning of landscape as sign or as text, geographers have had relatively littleto say about the practical and affective, or what Nigel Thrift calls the non-rep-resentational import of architecture.11 As I discuss below, attention to theembodied practices through which architecture is lived requires some newapproaches, just as it opens up some new concerns for a critical geography ofarchitecture.

Geographies of architecture: from the Berkeley School topolitical semiotics

The roots of architectural geography, if indeed we can talk of such a subdisci-pline, can be found in the rural landscape tradition of (largely American) cul-tural and historical geography.12 The study of architecture initially attractedthose geographers interested in the uniqueness of landscapes and their peoples.The specific focus on vernacular architecture, Goss notes, was seen as coun-teracting the architects overemphasis on the monumental, the unique and theurban.13 Buildings were treated as artefacts that reflected cultural values and a

Towards a critical geography of architecture 53

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

societys level of technological development. This tradition in cultural geogra-phy suffered from a relative lack of theoretical sophistication that allowed (nowseemingly) naive correlations to be made between architectural types and cul-tural ones.14 Early cultural geographers tended not to interpret architecture perse; rather, they described and mapped geographical patterns of architecturalstyles, and as a consequence their interpretations of culture were later perceivedto be thin rather than thick.15 For instance, Holdsworth has complained thatgeographers put an undue emphasis on form and type at the expense of otherfactors that tease out social and economic meanings.16

Partly in response to these perceived interpretive and theoretical shortcom-ings, Goss and so-called new cultural geographers, inspired by social theoryand interested in contemporary urban as well as historical and rural landscapes,have advanced new approaches to understanding architecture and its geogra-phies.17 At the risk of some oversimplification, one might identify two broadstrands. First, there were those, such as Cosgrove and Daniels, who took inspi-ration from Marxism, especially the maverick cultural materialist RaymondWilliams, and tried to understand architecture as a social product that bothreflected and legitimated underlying social relations.18 Secondly, there werethose like Ley and Duncan who looked to semiotics and the cultural anthro-pology of Clifford Geertz to read the built environment as a text in which socialrelations are inscribed.19 These two broad theoretical approaches were not asexclusive as my categorization may suggest. Indeed, Goss, in his 1988 manifestofor an architectural geography called for an interpretive framework that com-bined Marxism with semiotics and structuration theory. Giddenss structurationtheory taught architectural geographers that practices of power in the spaces ofthe built environment enabled and constrained the relations between structureand agency, and analyses and critiques of semiotics were taken on board byurban geographers interested in analysing landscape as a form of language.20

As the bitter debates of the 1980s over Marxism and geography have faded(and with them much of the emancipatory ambition of social theory), differ-ences between these two broad theoretical wellsprings of new cultural geogra-phy have been attenuated as well.21 While recent work by those who are explicitlyhostile to Marxism, like Duncan and Ley, has settled into what might be calleda political semiotic approach to the built environment in which landscapes areread for the cultural politics of their symbolic meaning, the attachment to polit-ical economy as an approach to interpreting landscape and architecture is barelyapparent in more recent books by Cosgrove and Daniels. For example, inDanielss most recent book, Humphry Repton: landscape gardening and the geogra-phy of Georgian England, his formal interpretation of landscape gardening dis-places the critical concern with cultural politics that animated his earlier workon the iconography of landscape.22 There is clearly an important place for thiskind of exhaustive scholarly work, but it is important also that the criticalimpulses that once made new cultural geography so politically vital not be evac-uated altogether. The result will be a politically anaemic cultural geography prac-tised purely for its own sake. The very best work in the field remains in touchwith the connections between the cultural and the political, in the very broad-

54 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

est sense of those words; but arguably there are signs of exhaustion within thispolitical semiotic approach to landscape and the built environment as the searchfor novel sites and signs reaches the point of diminishing returns.23

The problems are theoretical as much as political. Insisting upon the impor-tance of social context to the meaning of landscape texts, new cultural geog-raphers like Holdsworth insist that we cannot simply read; but reading, albeitpracticed in more theoretically self-aware ways, is exactly what they are doing.24

The new cultural geography of landscape, like the old cultural geography ofvernacular landscape, has tended to see buildings as signs or symptoms of some-thing else be it class, culture, capitalism, or resistance to them.25 For instance,in her recent Invented cities, Mona Domosh reads the cultural landscape of thecity as a form of self-representation in which the middle and upper classes ofBoston and New York inscribed their visions of social order . . . and in so doingproduce[d] visible representations of their individual and group beliefs.26 Whilethose of postcolonial inclinations have complained that this semiotic conceit ofdistant (in time and space) landscapes being inscribed with meanings availablefor us to read radically effaces cultural, historical and other differences sepa-rating geographers from their objects of inquiry environmental critics argue thatthis interpretive approach to landscape as a meaningful social constructionignores the agency of nature.27 While I share these concerns, the point I wantto make here is somewhat different.

This political semiotic approach to reading landscape in terms of the socialand economic context of its production tends to discount questions about howordinary people engage with and inhabit the spaces that architects design. Thus,for example, Hopkins, in his study of the West Edmonton Mall, argued that theowners spatial strategy of a simulated elsewhere contributed to consumerism an ideology by which the domination of corporate capital was legitimized andreproduced. As Bondi has warned, this interpretation strips the built environ-ment of the meaning it is given by the people who live in it and of the trans-formations, however modest, that they make.28 While there has been a greatdeal of recent work in geography on the cultural production of the built envi-ronment, much less attention has been given to its consumption. Contemporaryarchitectural geographies do not emphasize enough the fact that urban mean-ing is not immanent to architectural form and space, but changes according tothe social interaction of city dwellers.29

In exploring how architectural spaces are inhabited and consumed, geogra-phers of architecture might take a page from developments in the new con-sumption literature.30 Geographers now argue that consumption should be seenas a productive activity through which social relations and identities are forged.Such a perspective on consumption as an active, embodied and productive prac-tice dispels the sharp production/consumption distinction, and with it those tireddebates about resistance to versus domination by the inauthentic consumerismof more or less duped consumers. The new geography of consumption recog-nizes the creativity of ordinary consumers in actively shaping the meaningsof the goods they consume in various local settings, while insisting also that thecommodities themselves, the processes of their production and the identities of

Towards a critical geography of architecture 55

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

their consumers cannot be thought of as fixed and essential but instead mustbe theorized as what Harvey calls structured coherences, or what Latour callsactants that emerge as such through networks of inter-related practices.31 Byadopting such a perspective on the consumption and use of architecture, criti-cal geographers would be able to explore the ways that the built environmentis shaped and given meaning through the active and embodied practices bywhich it is produced, appropriated and inhabited. Such an approach to under-standing the built environment unsettles the sharp public/private boundarybetween the production and consumption of architecture and its meaning(s),and opens up the question of its dwelling as a politicized practice through whichsocial identities, environments, and their interrelations are performed and trans-formed.

But a critical geography of architecture must go a step further and acknowl-edge that much in the world is not discursive. Thrift has been the most stridentadvocate of this view. He insists that the consumption of commodities is not justabout the production of (symbolic) meaning.32 In what he calls, somewhatgrandiosely, nonrepresentational theory he seeks to move geography away froman emphasis on representation and interpretation towards theories of practice.His idea of non-representational theory demonstrates a progressive sense ofplace that is embodied and performative: This is not, then, a project concernedwith representation and meaning, but with the performative presentations,showings, and manifestations of everyday life.33 From a different perspec-tive, Don Mitchell makes a similar plea for us to see how culturalism operatesin social practice.34

If we are to take seriously this suggestion that an architectural geography mustaddress itself to something beyond the symbolic to questions of use, process,and social practice important methodological implications follow.Traditionally, architectural geography has been practised by putting architec-tural symbols into their social (and especially historical) contexts to tease outtheir meaning. But if we are to concern ourselves with the inhabitation of archi-tectural space as much as its signification, then we must engage practically andactively with the situated and everyday practices through which built environ-ments are used. In this regard, ethnography provides one way to explore howbuilt environments produce and are produced by the social practices performedwithin them.35 Those pursuing such a project, Thrift argues, must be observantparticipants rather than participant observers.36

Informative as it is, however, ethnography by itself is no more sufficient thanthe political semiotics of old. It is important to guard against criticisms such asthose recently made by Goss: the ethnographic approach risks banality by repro-ducing the obvious finding that consumers make their own meanings, withoutengaging in positive or negative critique of the politics of meaning.37 Thus,adopting an ethnographic approach to understanding architecture should notmean abandoning questions about the meaning of built environments. Rather,it means approaching them differently, as an active and engaged process ofunderstanding rather than as a product to be read off retrospectively from itssocial and historical context. As Bernstein suggests, meaning is not self-con-

56 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

tained simply there to be discovered; meaning comes to realization only inand through the happening of understanding.38 The happening of under-standing is something performed by investigators engaging actively with theworld around them and in the process changing them both. Thrift provides auseful explication in answering the question: what is place? He argues that cul-tural geographers have looked at place as something to be animated by cul-ture, as if place is made before it is lived in. Thrift prefers to see place simplyas there as a part of us, something that we constantly produce, with others aswe go along.39 Thrift also uses the case of dance to illustrate nonrepresenta-tional theory, quoting Isadora Duncan: If I could tell you what it meant, therewould be no point in dancing it.40

In getting to grips with the happening of architectural understanding, criti-cal geographers might also draw fruitfully from the planning literature. Drawingon postmodern, post-structuralist, feminist and postcolonial critiques LeoneSandercock confronts planning with its anti-democratic, race and gender-blind,and culturally homogenizing practices.41 She constructs a normative cosmopo-lis multicultural city one which can never be realised, but must always bein the making.42 In postmodern fashion, her thesis is deliberately ambiguous.She outlines those principles through which the cosmopolis might emerge:social justice, difference, citizenship, community and civic culture. This requiresa more politicized and bottom-up style of planning (insurgent or radical) thatresists closures and incorporates protest, civil disobedience and the mobilizingof different constituencies without exclusion. Sandercock provides planners withan epistemology of cosmopolis and an ontology of multiplicity that engagesdirectly with the embodied practices of making those cultural and political dif-ferences (multiethnic coalitions, neighbourhood groups, womens activism andso on).43

If the aim and object of a more critical geography of architecture must be toengage with those embodied and socially negotiated practices through whicharchitecture is inhabited, its understandings cannot be produced throughabstract and a priori theorizing. Rather, understanding comes out of active andembodied engagement with particular places and spaces. Accordingly, I wouldlike to try to flesh out my somewhat programmatic comments about a criticalarchitectural geography by reflecting on a number of experiences of the spacesof Vancouvers new Public Library.44

Exploring the building of Vancouvers newest civic landmark

When I first moved to Vancouver in April 1995 the new library was not yet open,but the Colosseum design was already materializing on the building site. As anewcomer to the city I spent a lot of time that summer walking and cyclingaround the city, in the double role of both tourist and geographer trying to geta feel for the city. On a tour of Granville Island and False Creek, I remembersaying to David Ley that I thought Vancouver was unreal, too perfect, a choco-late box city. I thought it resembled a city on Prozac. It was the image ofVancouver that struck me initially, but I had much more to learn.

Towards a critical geography of architecture 57

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

Vancouver is a city conscious of the reawakening of First Nations peoples andof changes due to an influx of capital and people from the Pacific Rim.45 Duringthe period 199095 the immigrant population of Vancouver had increased tonearly 35 per cent of the citys total, the second highest in Canada after Toronto.In 1996 the number of international immigrants in British Columbia exceeded50 000 for the first time since 1912, and for the first time ever Britain ceased tobe the leading origin of the foreign-born. In recent years 80 per cent of immi-grants to British Columbia have originated from Asia, led by Hong Kong andTaiwan, and the British contribution has now fallen to 2 per cent.46 I becameincreasingly interested in the urban politics of what I immediately realized wasa rapidly changing multicultural city. On reading David Leys paper onVancouvers monster houses and visiting Kerrisdale, I also became cognizantof the cultural politics of race and identity as they were reflected by, and builtinto, the architectural fabric of the city. 47

The debates over the library design raging in local newspapers and magazinesfuelled my curiosity about these issues still further. Vancouvers new PublicLibrary, funded through a publicprivate partnership, was and still is the largestmunicipal capital project to have been undertaken in the citys history. The pro-ject was to be the anchor for a planned redevelopment of the eastern sectionof downtown. Insofar as the issues were similar to those in gentrification workthat I had previously done, I was attracted to them but wanted to do somethingdifferent from the standard rent gap and political semiotic readings of gentri-fying landscapes.48 It was against this background that I began a detailed studyof the controversy over the new library, which seemed like the perfect vehicleboth to get acquainted with a new city and to explore in a different (for me atleast) way some wider concerns about representation, multiculturalism, and thecultural politics of urban change.49

To explore these issues I followed up on the media coverage of the library byinterviewing library officials and examining the results of their public consulta-tion exercises, as well as by talking to library users and other members of thepublic, and reading up on the architectural history of the city. Since I was inter-ested in the cultural-political assumptions about history and identity implicit inthe debates over the library design, I found that the most useful sources werenot the formal submissions to City Council but the op-ed pieces and letters writ-ten into the Vancouver sun, the Georgia Strait, and the Globe and mail. These Iread as symptomatic of the underlying fault-lines of difference surfacing in thecontext of debate over the appropriateness of the design for the citys newestcivic landmark.

I have struggled with this paper for the last five years, occasionally turningback to it in between other research projects. Each time I thought I had under-stood the library and its meaning, further reflection sapped my confidence inmy ability to represent fully the political semiotics of the building. What followsis not really an analysis of the library per se, but rather the story of how, inwrestling to represent its meaning, I have felt the inadequacies of an approachto understanding the built environment and the need for a different kind ofarchitectural geography.

58 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

I begin with a cultural reading of the main criticisms that have been mountedagainst the symbolism of the design. Then I recount a series of gradual steps Ihave taken away from this conception of architectural space as something withidentifiable and relatively stable, if also contested, meanings to be read. First, byreflecting on the ambiguity of design intention and then on the play of hybridhistories I consider the difficulties of fixing the meanings represented by archi-tectural forms in terms of determinate contexts. This is a fairly familiar decon-structive move, and my intention in executing it is not to make the stridentlypost-structural claim about the ultimate undecidability, and thus, in some sense,the political irrelevance, of the architectural sign. Rather, I want to suggest theimportance of remaining open to the ongoing enactment of architecture andthus of the dangers of reading too much politically into the signs and symbolsof architecture, to discounting the ongoing practices through which meaningsare performed. Thus, my third step away from political semiotics is to follow thesuggestions of Sandercock and explore the processes of public involvement inthe architectural competition through which understandings of the library werearticulated and produced. But since the meaning (and politics) of the libraryspace is not something dead and fixed only ever to be re-presented, my finalstep beyond the political semiotic approach to architecture is to engage criti-cally with the embodied and nonrepresentational practices through whichlibrary spaces are actually being used, appropriated, and inhabited. Relaying aseries of brief vignettes taken from my ethnographic notebooks I demonstratehow the meaning of the library is continually produced through the daily activ-ities of its users. I conclude by outlining some general principles of a more livelyand critical geography of architecture.

Criticisms of the symbolism of the Colosseum design

a larger drama facing every city is a commercial force that undermines all culturallandscapes. Symbolic meanings are eroded as steeples are overtopped by office build-ings, and as high-rise apartments are designed without ethnicity, post offices withoutnationality, corporate logos without language. Cities become stage sets for the plasticidentities of international banks and hotel chains. If indeed money dissolves culture,the determination of all Canadians to preserve their several identities is a defence ofvalues deeper than the dollar.50

Criticisms of the library design fell into three main sectors of concern about thepolitical meanings it implied. First, many complained that the design was racistand Eurocentric. For example, a planning consultant to the Vancouver PublicLibrary Board complained:

What does an ethnocentric archaeological image say to Vancouverites, NativeCanadians, Asian Canadians? What does it say about Canadian identity at all? Whatdoes it say about our future on the Pacific Rim? Successful buildings are usually def-erential neighbours, not visitors from another culture, continent and time.51

This critique reflects contemporary liberal anxieties about race relations inVancouver and Canada more generally. Over the past three decades, changes in

Towards a critical geography of architecture 59

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

Canadian immigration policy have brought substantial increases in immigration.In contrast to previous, predominantly European waves of immigration toCanada, contemporary migrants have come predominantly from Asia, Africa,the Caribbean and Central and South America, and the presence of these het-erogeneous allophones has disrupted the founding myths of Canadian nationalidentity as a contract between two founding peoples one English and the otherFrench. British Columbia was a latecomer to Confederation, and its colonial set-tlement history has meant that it always fitted rather uncomfortably into thisfounding myth, but recent immigration has been no less disruptive to the long-standing sense of British Columbia. Vancouver has become a particular magnetfor Chinese immigrants from the mainland and the former British colony ofHong Kong. One striking and well-publicized indication of the changing demo-graphics of Vancouver is the fact that now over 50 per cent of schoolchildrenin Vancouver have a mother tongue that is not English.

While immigration is one major source of the recent concern with race andidentity in the city, relations with Canadas First Nations are another. The legalrights, status and situation of Native Canadians are higher on the public agendain British Columbia than ever before, both because of the provinces large pop-ulation of Native peoples and because the peculiar history of land policy in theprovince means that legal rights to its territory and the very land on which thecity of Vancouver and its public library now sit is being contested in the courtsby Native Canadians.52 These colonial legacies make the alleged Eurocentrismof the design a particularly sensitive issue in a city struggling to come to termswith a more vocal and multicultural population. Another letter writer picked upon this same theme:

Its gratifying to see that Vancouver has finally caught up with 300 BC. We can onlyguess what design theyll pick to replace it 200 years from now, Windsor Castleperhaps?53

This is a relatively new sensitivity in Vancouver. After all, when Vancouversfirst public library, the Carnegie Public Library, was built in 1903, the buildingwas also controversial, but not for its Eurocentrism. Rather, the design of promi-nent Vancouver architect George Grant was widely criticized for its ostentatiousdecoration and the free mixing of domed Ionic portico with Romanesquerustication and a mansard roof.54 Times are different now, and the question ofheritage is on the lips of Vancouverites as perhaps never before. Arguably thisconcern with the past has been intensified as the pace of social and demographicchange in the city has accelerated.

Even before the construction of the library, Vancouver residents were sensi-tized to the intersections between heritage, race, and the built environmentthrough controversies over the construction of what the media has termed mon-ster houses (Figure 2). These large, opulent, modernist-style houses were builtfor the wealthy overseas Chinese immigrants moving into Vancouver in the late1980s and 1990s. To make room for their newly built homes, older homes inthe dominant Tudor revival and Arts and Crafts styles of Vancouvers old Anglo-Canadian elites were razed, and their destruction to make way for ugly new

60 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

monster houses was often resented. When the wealthy and largely white resi-dents of the Shaughnessy Heights and Kerrisdale neighbourhoods tried to banmonster homes and the relatively unvegetated style of landscaping oftenfavoured by Chinese immigrants, they became embroiled in a heated public con-troversy about the planning system, the preservation of Vancouvers architec-tural heritage and some deeper and more uncomfortable questions about raceand the cultural hegemony of Anglo-Canadians in a multicultural society.55

The debates over the design of Vancouvers new library echoed these recentconflicts. One critic charged: Youve created the most un-Asian of buildings inNorth Americas most Asian city.56 For many, of course, this would have beenhigh praise. The tender issues of racism and ethnocentrism are a reflection ofthe birth of Vancouver as a multicultural city. These local concerns are alsoinflected by, as indeed they helped influence, wider debates about Canadianidentity in the wake of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the long-running saga over the secession of Quebec. Canada is officially bilingual andyet also multicultural. As Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau explained, althoughthere are two official languages, there is no official culture, nor does any eth-nic group take precedence over another.57 Canadian policy on multicultural-ism aims to foster a society that respects and reflects the diversity of culturesand develops civic participation amongst Canadas diverse population. In recentyears, though, many have criticized Canadian multicultural policy for being tooconcerned with celebrating and expressing different cultures rather than devel-oping intercultural dialogue, for constructing an image of ethnic harmonyrather than paying attention to ethnic fault-lines.58

Towards a critical geography of architecture 61

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

Figure 2 ~ A Vancouver monster house

-

The reality of a multicultural city is directly related to a second criticism fre-quently made of the library design: its placelessness and inauthenticity.Editorialists complained:

Why did officials select a design from long time dead people? Why not somethingthat speaks of our times and ourselves . . . The City went to the four corners of theEarth, like modern day Argonauts in search of an original design . . . and whimperedback with a copy.59

For this critic, a civic landmark for contemporary Vancouver must be original,authentic, something that speaks of our times and ourselves. This is a hard taskfor a city that is itself increasingly disembedded from any single place such thatits identity is determined by global movements of money, information andpeople, what Appadurai calls mobile ethnoscapes.60 Local architectural criticTrevor Boddy expressed an all too typical elitist contempt for the citys archi-tecture:

Vancouvers sense of its own history is largely borrowed or invented in the most per-sonalised manner imaginable, making it ripe for the instant identi-kit of PoMo. It isno accident that the consumer-packaged historicism of the Post-Modern has its great-est successes in the US sunbelt and Canadian west coast, places neurotically missinga sense of history and wanting to invent one by architectural means.61

Without a sense of its own history, rooted in and represented by an authenticlocal style, Vancouver, Boddy suggests, can have no sense of itself. Though DavidLey is more approving of the human scale of many postmodern styled devel-opments, he too detects in these complexes a symbol of modern anomie,detached from any authentic sense of place.62 From such a perspective themonumental scale, Colosseum-like form and promiscuously borrowed style ofthe new library building was frequently condemned as a sign of the essentialrootlessness and inauthenticity of globalization, through which the face ofVancouver was coming to resemble so many other business-friendly Pacific Rimcities.

Finally, other critics connected the apparent inauthenticity of the librarydesign to a dystopic Disney thesis.63 For these critics, the resemblance of thelibrary to the Roman Colosseum was a symbol of the wider process by which thedisplacement of public spaces was being concealed through elaborate bread-and-circuses variety dis(at)tractions staged within shopping malls, theme parks andother ersatz public spaces. To this view, the Colosseum design is an architectureof deception, one which substitutes an essentially false image of both past andpresent for the more authentic city.64 The Colosseum design, with its commer-cial arcade of shops and cafes, is a contrived and ersatz architecture, devoid ofany geographical specificity, that substitutes the placebo experience of con-sumption in a shopping mall-type environment for the truly democratic publicspace of the public library.65 One indignant letter-writer complained:

Of what possible relevance to Vancouver, the Pacific Northwest, its people and envi-ronment, could an imitation Roman Colosseum be? I would say its about equal tothat of the values of panen et circensis to those of a library. Some good may come ofit. Our childrens children will be able to tell how a bunch of culturally foggy city

62 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

fathers had a ring slipped through their noses without even becoming aware of it. Onwith the creation of Disneyland North!66

The Disneyland reference then, speaks not only to anxieties about the appar-ent Americanization of Vancouver and of Canada in the wake of NAFTA, andwith it the loss of local identity, but also to deeper concerns about the libraryas a symbol of decline in the civic quality of the city.67

Insofar as critics of the library design responded in these three very differentways, the debate over the library design demonstrates the ambiguity of the archi-tectural sign. This interpretative flexibility and the continuous possibility of mak-ing out still other ways of reading the library problematizes critiques of thelibrary design as a straightforward symbol of Eurocentrism or as placeless inau-thenticity, or of the creeping Disneyfication of the city. Indeed, I found that theambiguous nature of the library design itself made any definitive reading of thelibrarys meaning difficult to sustain.

The ambiguity of intention

Most people are able to read an image, a landmark quality they can absorb and reactto, even before its built. . . . The city has changed a lot since I spent a bit of timehere. The tranquil little town by English Bay became a thriving Pacific Rim com-mercial centre with hundreds of towers. Green glass, blue glass, pink glass, graniteand metal. The city glistening in a kind of crass commercial modernity in the mostbeautiful physical setting. Now in the midst of all that . . . Im asked to create a civicplace with a sense of civic identity. (Moshe Safdie)68

Hoping to provide a thicker and more intertextual reading of the library design,I turned to the writings of its architect, Moshe Safdie, for some clues as to whatit might represent. This was an approach to interpreting landscape recom-mended both by Domosh and by Duncan and Duncan, but as I pursued it Ifound that, far from providing a secure context for my own semiotic interpre-tation, my reading of Safdies reading(s) of the library left me feeling confused.69

Indeed, the experience seemed to suggest the difficulty of pinning down defin-itively what the library signified.

In a series of interviews and other writings, Safdie has responded to publiccriticisms of his library design and expressed his own rather idiosyncratic andcontradictory views of architecture. Responding specifically to the charge ofEurocentrism, he asserted that as many people have seen hanging gardens or aGreek temple in the library design as have seen the Roman Colosseum. Whatpeople call it is their business, he offered, but insisted that people need to getpast the image of it as Colosseum-like.70 On another occasion, however, Safdieclaimed to have settled on a Roman expression for the library design by acci-dent: When I began working on Vancouver, the idea came forward to central-ize the stacks . . . and create a reading gallery around them . . . We ended upwith a rectangular block, surrounded by an ellipse . . . At this point we recog-nised the similarity to the Coliseum [sic], both dimensional and proportional.And we actually were amused, as it appeared completely unconsciously.71

Such inconsistency is typical of Safdies writings. His written texts often seem

Towards a critical geography of architecture 63

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

to speak in riddles, and my difficulty deciphering Safdie made me increasinglyuneasy about the contextualization method proposed by Domosh and other cul-tural geographers for interpreting the meaning of landscape and other nontexttexts.72 With so many confusing and contradictory claims, it did not seem pos-sible to tease out Safdies original intentions of what he had meant it to repre-sent. The logical corollary of this unsettling realization was that a structuralcontext on which to ground architectural interpretations might prove just as elu-sive as an individual one, because any given context could itself be viewed as atext in a never-ending chain of signification.73

A look at Vancouvers new library is not a straightforward peek into MosheSafdies thoughts, and even if it were Im not sure that it would necessarily beany less ambivalent! Safdie has long criticized postmodern architecture for itsnarcissism, its pointless hungering for novelty and its lack of commitment tosocial and community issues. For him, Postmodernist doctrine confuses gen-uine universal symbols, ones that are immediately meaningful to people from aparticular culture, with ironic metaphors symbols that are in and familiar toa particular group, while totally meaningless to the public at large. Safdie hasargued that the duty of architecture is to serve the community rather than theego of the architect a comment that seems strange in light of the postmod-ern monumentalism of his design for the Vancouver Public Library.74 Indeed,Safdies friend and fellow architect Frank Gehry has said of Safdie: For a guywhos put down postmodernism, and then designs a library that apparently lookslike the Colosseum, maybe its time to write another article saying Im sorry.75

The play of hybridity

The library design exploits the contrasts between a classical exterior and amodern interior (Figure 3; compare Figures 1 and 4).76 Its round shape, tiersof columns and sandstone coloured concrete all echo the classical form of theRoman ruin. But when you enter the library, the feeling is very different: sleek,modern and high-tech. Looking up through seven spectacular floors of glisten-ing glass protecting library stacks and reading-tables from the noisy interiorarcade below (Figure 4), you soon forget its classical and Colosseum-like echoes,so impressive is the display of the buildings high-tech innards: air ducts, pipesand wires.77

I often puzzled over this juxtaposition of self-consciously old and new, andwhat the re-emergence of classicism in postmodern architecture might mean.78

I began to wonder if the return to classical forms might signify an espousal ofthe values of the classical tradition, and whether this historical context couldprovide me with a grounding for my reading of what the library meant. As Idelved deeper into the histories of architecture and of ancient Greece andRome, I turned up some interesting arguments that problematize the claims ofcritics who argue that the classical tradition is simply Eurocentric and thus inap-propriate for a multicultural Vancouver. For instance, Galinsky argues that it isinaccurate to conceive of Greek and Roman societies as monocultural andmonoethnic.79 The notion of pure culture, he claims, is an invention of nine-

64 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

teenth-century romanticism. As such, Galinsky implies that if a return to classi-cal forms does signify an espousal of the values of the classical tradition, theclassical values we need to recover are those of its actual multicultural historyand not those of the Romantics classical revival.80

Architectural writer Abel argues that in fact there are very few examples ofindigenous architecture in the world. Most of the worlds architecture has beeninfluenced by cross-cultural contact. Even the Islamic empires typical hypostylemosque owes much to Roman building types. Thus, he says there is much to belearned from colonial architecture, for the colonists home architecture wasnot simply duplicated in a different environment; its relocation involved thetransformation of the colonists cultural baggage: for both monumental andnon-monumental architecture generally, the critical measure of historical importis not the individual work taken separately, but the whole linked series of prece-dents and later variants, with all their transformations over time, each of whichin turn becomes a potential model which can beget still more transformations.81The Tudor revival mansions of Vancouver provide such an example, yet most ofthe geographical writing on this Anglo-Canadian architectural style has tended

Towards a critical geography of architecture 65

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

Figure 3 ~ The contrast between a classical exterior and a modern interior

-

to treat it as a straightforward reflection of the late Victorian values of middle-class England, without much discussion of the transformations involved in itsdislocation and relocation to British Columbia.82 By way of contrast, David Leysdiscussion of Vancouvers monster houses goes some way towards an under-standing of the continuities and discontinuities involved.83 Anthony King alsooffers a superb analysis of the global cultural production of the bungalow,another characteristic feature of Vancouvers vernacular architecture.84

In reflecting on the ambiguity and hybridity of the library design, I began towonder if those who have criticized the ersatz Colosseum, and even perhapsSafdie himself at times, have missed the postmodern play. The Colosseum designis ambiguous: it reflects no singular engagement and can be read as multiper-spectival.85 Users can locate their own places in and through the different mem-ories and images that the design throws up for them.86 These readings arestructured and do adhere to certain patterns, but, as some published letters illus-trate, the library is liable to many different, and some quite wacky, readings. Forexample, one person repatriated the circular design as a landmark of New Age

66 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

Figure 4 ~ Inside the Colosseum facade a high tech building with a taut glass skin

-

spirituality: Far from being ethnocentric, the circle has had mystical significancefor cultures as diverse as the ancient Celts and the aboriginals of the NorthAmerican plains. What better shape for such an important building as alibrary?87

Lowenthal suggests these multiple readings are the results of different mem-ories. He argues that ideas of identity and heritage swim in a swamp of collec-tive memory.88 Likewise Boyer, in her City of collective memory, argues that thereis a need for an architecture of collective memory that allows for differencedrawing absences into the present. But how is this effect produced? My gut feel-ing was that Safdies Colosseum had such potential. The ambiguities of its hybridform seemed capable of drawing out different memories and bringing themtogether, but I had difficulty imagining the concrete social process throughwhich the built environment could help us, as Boyer put it, to recall, reexam-ine, and recontextualize memory images from the past until they awaken withinus a new path to the future.89

The architectural competition and the public articulation of meaning

There is a strong sense of collective responsibility . . . There is, too, a strong sense oflocal citizenship which is informed by the context of cosmopolis, that is, by an aware-ness of the need for a new kind of enlarged thinking, the need for connection tothe cultural Other . . . in the multipli/cities of the postmodern age.90

I struggled with these questions for some time. Upon reading SandercocksTowards Cosmopolis, I decided once again to go back to my notes and drafts ofthis essay to think some more about the public process of articulating and con-testing the meaning of Vancouvers new library building. Sandercock empha-sizes the importance of public participation in planning for a multicultural city.91

In order to achieve a planning process that is sensitive to community and cul-tural diversity, planners need to listen to the voices of difference, to the multi-plicity of publics, before they can imagine togetherness in difference. ReadingSandercock prompted me to think again about the consultation process that wasassociated with the choice of architectural design for Vancouvers newest civiclandmark. Previously, I had simply mined the commentaries for quotationsthat struck me as symptomatic of the underlying cultural politics reflected inthe library debate. But having read Sandercock I began to wonder if I didntneed to think much more about the public process, for its meaning wascontested.

In a new spirit of participatory government, city officials made an effort toconsult the public about the choice of the design for the new public librarybuilding. Councillor Price from the library selection panel explained: This is amonument I think a monument is something that has to be loved by the peo-ple, and one of the ways of creating that bond from the beginning is by involv-ing them in the choice.92

Under the aegis of the Architectural Institute of British Columbia, the cityheld a formal architectural competition. The competition stirred up more pub-lic interest in architecture in Vancouver than there had been for some years,

Towards a critical geography of architecture 67

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

but it also produced certain tensions and contradictions.93 Only two of the com-petition entrants were local: the world-famous Arthur Erickson and RichardHenriquez.94 Neither passed the initial selection, and the elimination of the onlyVancouver-based architects from the competition to design the Vancouver PublicLibrary sparked heated debate among the citys architectural connoisseurs.Andrew Gruff, Professor of Design at the University of British Columbia, howledin protest:

Its bloody ridiculous you cant argue that there was nobody here who could do theproject. Its an undermining of local culture if all you do is allow outsiders to com-pete for what is probably the most important public building of the decade.95

His view was echoed by Canadian architectural critic Trevor Boddy:

A society which chooses not to listen to its best architects as Canada has over thepast decade or two risks the loss of a sense of the past and the future in equalmeasure, with potentially disastrous results.96

Significantly, both these critics appealed to notions of heritage. For Gruft, localculture was being undermined by the selection of non-Canadian architects asfinalists in the competition, while Boddy worried that as a result a Canadian andspecifically Vancouver sense of place would be lost. The past and the localwere integral to their sense of Vancouvers identity and indeed of its future. Yetthe library design was supposed to represent the present, more globalVancouver, a city into which there has been a significant immigration of Asians,South and Central Americans, Caribbeans, East Europeans, and so on. In thesecircumstances the Northwest European traditions harkened to by these aestheticnationalists are problematic.

The three finalists were announced in December 1991 and given $100 000 todevelop a concept and model. The three groups came up with very differentdesign proposals. As we have seen, the eventual winners, the Boston-based Safdieconsortium (with local partners Downs/Archambault), proposed a Colosseumdesign, a flourish of elliptical colonnades and ersatz classical moulding (seeFigure 5). Los Angeles-based Hardy Holzer Pfeifer proposed a modernist-stylehalf-moon model that some compared unflatteringly to a multi-storey car park,and the Toronto firm Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg proposed a Bauhaus-style model reminiscent of the old public library (a classic modernist design)but with echoes also of a Chinese pagoda.

The city then approached Vancouver residents to find out which of the threedesigns they preferred. This new style of participatory urban politics has beentaken on board by the relatively liberal planning community in Vancouver. Publicmeetings were held in response to the monster house conflict in Kerrisdale, andthe city of Vancouver has gone out of its way in recent years to solicit the view-points of the Vancouver public to inform the production of new planning doc-uments.97

In February 1992 the three anonymous models went on display at City Hall,several community centres and shopping malls, as well as the central library forpublic inspection. Along with the models there was also a single-page question-naire, The Library Square Design Competition questionnaire for the public, with pho-

68 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

tographs of the three models and a comments sheet, to be filled out by inter-ested members of the public. Over 7000 people filled out the questionnaire, ofwhom 70 per cent chose Safdies Colosseum model. The representativeness ofthis sample cannot be gauged with any certainty, but it probably did not includea cross-section of Vancouvers many social classes and ethnic groups.98 The ques-tionaire asked: Does the proposal convey an appropriate image as one ofVancouvers most important public buildings? Most of the responses were littlemore than one-liners about the designs, but some were more substantial. Somepeople even went so far as to attach seven or eight typewritten pages of com-ments.

The general view was that the Safdie model was fun and had panache. Theother two models were seen as too conventional, too much like ordinarydowntown office blocks or parkades. Safdie seems to have won because hehad a strong vision. As Vancouver Public Library director Madge Aalto latertold me, The AIBC had printed 500 sheets to start with and were astonishedat the feedback over a three week period and kept reprinting the sheets to

Towards a critical geography of architecture 69

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

Figure 5 ~ Architect Moshe Safdies model for the design competition

-

meet demand. Public interest was high.Safdie apparently found the public vote quite a traumatic experience.99 He

would have preferred not to have taken part in a public competition, for heargues that a public vote can often preclude more avant-garde designs. However,to what extent the publics comments influenced the final judgement it is dif-ficult to say, because the final deliberation of the committee was closed to thepublic. But given the strong support for the Colosseum design, it would havebeen awkward (to say the least) for the competition committee to contravenethe results of the public consultation exercise. Andrew Gruft argued that theColosseum design was popular because it was splashy, easy to read, made thebiggest gesture, but he felt that the public didnt know enough of the techni-calities to make an informed choice.100 There is something to this criticism. Laypublics do not generally have the technical knowledge necessary to makeinformed choices about, for example, building materials, costs, and the feasi-bility of structures. This critique of the publics understanding of expert systemsis frequently made in, for example, environmental debates, where defenders ofexpert discretion argue such decisions should be left to the professionals orexperts. The issue is whether architecture is strictly a technical matter that onlyexperts are qualified to decide or whether it is something that the public canjudge, and how to balance expertise against democratic participation.

In the case of the Vancouver Public Library the final decision was made by aselection committee that included five members of the library board, three pro-fessional architects (New York-based William Pederson, Fumihiro Maki fromJapan and Vancouvers Gerald Rolfson) and three publicly elected officials (thenMayor Gordon Campbell and two councillors). The panellists evaluated reportsfrom the technical advisory board and the urban design panel, as well as thepublic responses to the three finalists. This was an unusual panel of judges foran architectural competition: such competitions are customarily more heavilyweighted towards professional architects.101

We can perhaps assume, therefore, that the final decision in this case was pop-ularly and politically driven as much as professionally.102 Indeed, althoughSafdies model won the contract, it was not technically feasible, at least not withinthe allotted budget. As a result the office building had to be relocated, one ofthe lower floors eliminated, the overall floor space of the library reduced, allbut one of the atria filled in (compare Figure 1 with Figure 5), and the rooftoppublic garden, one of the biggest selling-points of Safdies design, was left forfuture redevelopment.103 These changes reinforced the scorn of critics whocharged that he had won the contract through misrepresentation and ersatzhistory, the obvious Colosseum form playing to the gallery, the bread-and cir-cuses crowd which was crucial to the mock democratic architect selection, mod-els being displayed in shopping malls, then collecting votes.104

This conclusion bothered me until reading Sandercock reminded me of theimportance of the process through which the design and its meaning had beenarticulated. Perhaps the very fact that there has been so much public debateand controversy over the library design represented a success, albeit partial, forSandercocks vision of cosmopolis. The building has generated great public

70 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

interest and excitement about the library. As city councillor and member of thecompetition panel Gordon Price put it, At least this building provokes passionand opinion. The worst thing we could have done would have been to have cho-sen something bland and safe.105 Though the design itself is clearly provoca-tive, much of this passion and public feeling was generated through the publicconsultation process itself, and the way in which different constituenciesengaged with the library design.

Turning to consumption: ethnographies of use

Local architects have never accepted the design, saying that it does not reflect ourwest coast architecture and in that they are correct. It does, however, provide theclient and the user with a signature building that functions well for the patron andwhich has become a major tourist attraction, as well as an immensely successful libraryattracting 6,000 to 8,000 people a day year round.106

Once I realized that the public process of deliberating on the library design wasthe very means through which its contested meanings were produced, I beganwondering why this process of enacting meaning should be imagined as some-thing finished only continually to be re-presented. This led me to think moreabout the public consumption of architecture and to reconsider the ongoinguses of the library and its spaces. Drawing on Deleuze and Foucault, I had writ-ten previously about how the intellectual spaces of the library proffered a con-testatory countersite and thus acted in the terms of the heterotopia.107 Somehow,though, I had always distinguished in my mind between the actual functions anduses of the library and the cultural-political symbolism represented by its design.True to the political semiotic approach, I had conceived the latter only in termsof a (mis)representation of the former, and thus conceived the task of a criti-cal geography of architecture as one of simply diagnosing the political semioticsof mystification and legitimation in the library design.

Acknowledging the ongoing uses and inhabitation of the library took me afinal step beyond this political semiotic approach to the built environment andits concern with architecture only as representation. Concern for the habitual(and nonhabitual) use and consumption of the library throws open importantnew questions of everyday practice, embodiment and performance. Instead ofasking what the library means, I began also to consider what it does. What takesplace within (and without) the library? How are dominant (and not so domi-nant) social practices and relations performed? Such questions about the dif-ferent social experiences and uses of modern architectural spaces have beenexplored by Borden et al., who have begun the critical task of understandinghow the architectures of modern life are actually lived by differently positionedindividuals.108

In moving towards a critical geography of architecture I do likewise. This inter-est in the nonrepresentational and embodied practices enacted within thelibrary treats the spaces in which practice takes place much more seriously. Nolonger just a passive stage for the rehearsal and re-presentation of predeter-mined social scripts, space becomes alive and integral, inextricably connected

Towards a critical geography of architecture 71

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

to and mutually constitutive of the meanings and cultural politics being workedout within it.109

With this new understanding of the importance of the embodied consump-tion and practical inhabitation of space, I went back over my field notes with anew eye and revised my discussion of the library yet again. I now recognize that,while architecture and the meanings it represents are clearly important anddemand our critical attention, so too are the ways in which they are enacted,performed and often subverted. Indeed, I now realize the two are inseparableand not usefully thought of in terms of those familiar representational dualisms signifier/signified, form/content in which I had originally organized my dis-cussion. It is through the ongoing and practical appropriation and use of thelibrarys spaces that its social meanings become sedimented.

In an effort to lay bare the happenings of architectural space, their embod-ied and creative consumption, and their meaningful understanding, I want topresent several vignettes drawn from my notes taken during eighteen monthsof my own intermittent study at, and of, the library. I have selected these frag-ments to show how the library and its spaces and meanings were producedthrough everyday (and not so everyday) practices of use, including my own.110

During this time I went on library tours, talked to a number of library usersand of course used the library.111 I read and borrowed books, looked atpromotional materials and browsed through the library web site (http://www.vpl.vancouver.bc.ca). I also ate and shopped in the librarys retail street andinterviewed the librarys director, librarians, retail staff and security guards. Ihad originally produced these ethnographic field notes to provide empirical datafor the work I was doing at the time on the privatization of public space andthe public space of the Vancouver public library.112 In retrospect, however, Ihave also found them useful in reflecting back on my own experiences of thelibrary and in changing my understanding of it.

Of course, the richness and diversity of library user experiences cannot berepresented fully here. The Vancouver Public Library is the second largest pub-lic library in Canada, with 395 000 card-holders and over 8 million items bor-rowed annually. My hope is that disclosing a selection of vignettes will convinceyou, as it has me, of the importance of the librarys ongoing appropriation anduse.

My first vignette takes place over a cup of coffee whilst sitting outside BlenzCoffee in the librarys commercial arcade. I often took a coffee break whilstworking in the library. On this particular day I happened to sit at a table nextto a young couple, a white man with leather jacket and ponytail and a well-dressed Japanese woman, talking intently. Sipping my latte I listened to theirconversation. In his laconic west coast accent he was telling her how to beCanadian. You have to be more assertive, he said. That comment pricked upmy ears, as it wasnt how I thought of Canadians. It soon became apparent thatthe pair werent a couple at all, but had only just met, perhaps in the libraryarcade. The woman had trouble understanding the comment and acted coy.Soon the conversation drifted beyond what it meant to be Canadian and into adiscussion of attracting the opposite sex. Before leaving the man gave the Asian

72 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

woman his telephone number and said that she could telephone him if shewanted to talk further.

In this case the couple used the space of the library for their own purposes.The library was transformed into a site in which cultural values were beingworked through while playing out the mating game or, depending on how youread it, sexual harrassment. The library became a site for the process throughwhich their sociability was getting worked out. This interaction to a consider-able degree makes a nonsense of dystopic theses on the demise of public space,for the arcade became an amenity, a stage, for public interaction rather than asymbol or example of the privatization of public space. The tables and chairsand coffee shop in the library arcade were fundamental to the nature of theinteraction. In another context, for example at work, where the couple may haveknown each other, or in a bar where they didnt know each other, the interac-tion would have been quite different.

My second vignette is situated in the newspaper and magazine section of thelibrary. The library has made a real effort to further its principles of openness,appreciation for difference, and cultural inclusiveness.113 For the multiculturalpopulation, some of the librarians are required to have different language skills,and the library has a special language laboratory, as well as a selection of for-eign newspapers and magazines. During the day the newspaper and magazinesection gets a lot of use. Particularly noticeable are the number of elderly immi-grants whose age and dress mark them out from the students and business peo-ple who also make heavy use of this section of the library. Many are regularswho come to the library every day. Indeed this section of the library seems toact as a kind of gathering-place a home away from home. A social and cul-tural cross-section of Vancouvers elderly population can be found reading for-eign newspapers from around the world.

I often spent time there reading British newspapers and sometimes struck upconversations with other users. I remember an elderly English gentleman saidto me, as he rattled The Times, Foreign newspapers are expensive, so with timeon my hands, Im retired, I come here to find out about back home. An elderlyGerman gentleman said to me, Its quiet here and cosy and I can catch up onevents back in Germany in peace. A Chinese woman walked around the read-ing-tables searching for a particular Chinese newspaper, as if someone had stolenit from her. Through their reading these users transform the library into a placeof connection in which everyday horizons are extended back or forward fromcontemporary Vancouver to imagined elsewheres, perhaps mother countries orhomelands of distant relations. These connections and the meanings they givethe space of the library are not pregiven but continually (re)shaped and (re)pro-duced. The public library, with its access to foreign newspapers and magazines,becomes a space in-between, in-between Canada and their country of birth, aspace in which ideas about home and nation and encounters with Others, realand imagined, are played out. From talking to these old folk, I discovered thatfor them the library became temporarily a place/space of not here nor there,of indeterminacy; as one woman said to me, Sitting here reading news fromhome I feel like Im not there [i.e., Hong Kong, her place of birth] but Im not

Towards a critical geography of architecture 73

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

here either its strange. Some said that they felt like strangers in a strangecity, but that the library gave them a kind of life line to home . Another saidthat he was glad that he wasnt at home. Although their reading was located in the newspaper and magazine section their reading eluded the librarybuilding as the space became home. In this way the space of the library wasincorporated into processes of identity formation and reproduction.

My third story takes place in the library toilets (that is in the ladies toilets).Due to a lack of public facilities on the streets, many people come into thelibrary simply to use its toilets. After a coffee break and before sitting down todo some more work I decided to go to the toilet. On entering I came across ahomeless woman looking under the door of one of the cubicles. I have com-mented on the design of the librarys toilets elsewhere114 with wide gaps belowthe doors for surveillance purposes. Perturbed, I went into the adjacent cubi-cle. When I came out the woman was staring at a young woman who had beenin the cubicle but was now washing her hands. The young woman left, and Istarted to wash my hands. At the same time the homeless woman began toundress and to fill the sink with soapy water. I did not stay and watch, but thewoman began to wash herself as I left. The library, that is the library toilets,became a site in which bodily cleansing was negotiated. The woman, I assume,was checking to see if anyone was in the cubicle before undressing to wash her-self.

This homeless woman appropriated the library for her own purposes tobathe. She used a public space to undertake a private activity. She made a pub-lic space temporarily a private one, as evidenced by my uncomfortableness Ifelt like I was intruding in her space. Critically, she ignored the surveillance ofthe toilets (as I have mentioned elsewhere they were patrolled regularly); BigBrother watching (the Panopticon) had little impact on her behaviour. Attentionto the geography of this womans embodiment points to the expressive powerof embodiment. There was a sense that cleanliness and public propriety wasimportant to this woman even though she lacked access to facilities for it. Heruse of the toilets, her bathing, signified a social exclusion that she was perhapstrying to cover up. This capacity to take up and transform the space of thelibrary (toilets) alludes to the myriad of possibilities (politics of the moment)that can be taken up in the built environment.

One activity that I saw over and over again was schoolkids playing on thelibrary escalators, running up the moving escalators to see if they could get tothe librarys fifth floor and back down again before their friends did. As theyran up the escalators they would push other users out of the way, laughing andpanting. Here the kids, to many peoples annoyance, were appropriating thelibrary as an indoor playground, as a site of physical performance, even as a siteof disrespect (as one adult on the escalator said to me) for their elders. Thisuse points to the inadequacies of reading the library as pure symbol. For thesekids, what the library means is largely irrelevant. Rather, theyre interested inwhat it does and in what they can do there. While their use of the library as aplay space and site of homework production may be particular, their shaping ofits spaces through bodily inhabitation is not. In focusing so much attention on

74 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

what meanings the built environment might represent, cultural geographershave failed to pay enough attention to questions of practice and to the livedpolitics of architectural use opened up by these brief vignettes of the library asdwelling.

Moves towards a critical architectural geography

Every serious cultural analysis starts from a sheer beginning and ends where itmanages to get before exhausting its intellectual impulse.115 My moves towardsa critical architectural geography pivot around the argument that [w]e do notact within spatial segments on the one hand and read meanings onthe other.116 The built form frames both representation and social practicessimultaneously.117 As Barthes says:

If I am a woodcutter . . . The tree is not an image for me, it is simply the meaningof my action. But if I am not a woodcutter . . . this tree is no longer the meaning ofreality as human action, it is an image-at-ones-disposal.118

Architecture professor Kim Dovey finds clues for this framing in Heideggerscontemplative (Vorhandenheit) and active (Zuhandenheit) modes of dwelling.119

The meaning of both architectural form and behaviour in space are processualand based in everyday life, in dwelling. Whilst we may need different method-ological tools to understand these framings, they are nevertheless integrated.There remains in this integration a theoretical and methodological tensionbetween deconstruction and communicative practices. To remain open to thelessons of deconstruction but to move towards a social and communicative jus-tice and democracy, Bernstein argues that we need to grasp (the tensionsbetween) both of these elements.120

In moving from a political semiotic reading of the Vancouver public librarybuilding towards a nonrepresentational approach open to ongoing social prac-tices, I have moved from an abstract contemplation of architecture as repre-sentation to a more active and embodied engagement with the lived building.I do not suggest that behaviour in space is more important than architecturalform, only that the meaning of both is based in everyday life, in dwelling. It fol-lows that representations are not simply read, but are constructed throughinteraction.121 This interactionist approach no longer privileges architect (orproducer) and form over function. It recognizes that meaning is not somethingfixed but is ongoing and continually produced through practice, for humanaction itself is forever unfinished.122

In this approach, power over and empowerment become one, for [a]ll ques-tions about power as mediated in built form come back to those of empower-ment.123 Contrary to Gerecke, who argues that connecting architecture and theemerging philosophy of empowerment may seem like mixing oil and water,124

in that architecture is usually about power over rather than empowerment, aconsideration of social practices enables us to appreciate the embodiment ofgestures of emancipation within the formal imagery of a building. The con-nection between built form and human action is kept alive. As such, radical

Towards a critical geography of architecture 75

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

and/or emancipatory possibilities are drawn back into the equation. Such anapproach recognizes the multiple connections of power to built form. It recog-nizes the spatialized entanglements of power.125

Political engagement is important in a critical geography of architecture, soperhaps it is time to think about it more broadly. Architectural geographers havesought to engage politically with the built environment (primarily in terms ofthe contested meanings it represents).126 As demonstrated by the debates overthe meanings represented by the Vancouver Public Library, this is clearly nec-essary for a critical geography of architecture, but not sufficient. For in uncov-ering embodied geographies of practices and performances, these may be recastas resistant acts. For example, the homeless woman bathing in the library couldbe read as a form of resistance to the surveillance (and thus control) of thelibrarys toilets. However, as Cresswell argues, there is a danger in geographythat the resistance currently being found in all areas of social life could lead toresistance being a meaningless and theoretically unhelpful term.127 Indeed,Thrift argues that it is time to move beyond a geography in which often thegenerative aspects of space are shoehorned into negative theoretical formats asresistance and to acknowledge, following Perec, all the different species ofspaces.128 Thrift seeks to broaden his analysis of space(s) by emphasizing every-day practices in/of those spaces: These are unreflective, lived, culturally spe-cific, bodily reactions to events which cannot be explained by causal theories(accurate representations) or by hermeneutical means (interpretations).129 Butmaybe he goes too far.

By considering the everyday social practices of the consumers/users of archi-tecture, identity and its formation become a central theme in this critical geog-raphy of architecture. This ties into the work of contemporary urban planners,such as Sandercock, who emphasize a practical engagement with multiplicityand difference in post-modern planning, as well as architects who now arguethat architecture as identity rivals architecture as a language and architec-ture as space as one of the main themes and metaphors in architectural dis-course.130 In the Vancouver library identity formation for the elderlyimmigrants in the newspaper section was about occupying many places on dif-ferent maps simultaneously it was about the species and pieces of spaces.

Finally, I want to urge architectural geographers to learn from developmentsin critical geography more generally.131 For researching and writing this paperhas taught me that architectural geographers need to become more open todevelopments in disciplines outside of geography, in for example architectureand urban planning. These two disciplines in particular (along with recentdebates in critical geography) have made me realize the importance of makingacademic work more public, and of linking up with urban practitioners.132 Toclose, I quote from Borden et al., who outline the kind of critical architecturalgeography that I would like to see:

a cultural and educational initiative aiming to explore, understand and communicatethe complex intersection of architecture, cities and urban living. It does so in threeways: publicly, by presenting and promoting new ideas about architecture and citiesto the general public; professionally, by presenting to architects and other urban

76 Loretta Lees

Ecumene 2001 8 (1)

-

design professionals new ideas about cities and urban living; and academically,through interdisciplinary enquiries involving architectural history, art history, culturalstudies, feminism, planning, sociology and urban geography.133

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Don Mitchell, David Demeritt, an anonymous referee andDavid Ley for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.Research for this paper was undertaken during a two-year research period at theUniversity of British Columbia, Canada, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, UK.Finally, thanks to the Director of Vancouver Public Library, Madge Aalto, foranswering my questions on the design and public consultation phases of thelibrary competition, and to all my interviewees.

Notes1 C. Jencks, Heteropolis: Los Angeles, the riots and the strange beauty of hetero-architecture

(London, Academy Editions, 1993), p. 77.2 The library complex includes the central public library and a 22-storey federal office