Tourism Journal7

-

Upload

sharifah-syed -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Tourism Journal7

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

1/18

This article was downloaded by: [Universiti Teknologi Malaysia]On: 14 November 2011, At: 00:12Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Tour ism and Cultural ChangePublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:htt p:/ / www.tandfonline.com/ loi/ rtcc20

Socio-cultural t ransformations throughtourism: a comparison of residents'perspect ives at two dest inat ions inKerala, IndiaLeena Mary Sebastian a & Prema Rajagopalan a

aDepartment of Humanit ies and Social Sciences, Indian Inst itute

of Technology Madras, Chennai, 600036, India

Available online: 07 May 2009

To cite this article: Leena Mary Sebast ian & Prema Rajagopalan (2009): Socio-cul turalt ransformat ions through tourism: a comparison of residents' perspectives at two dest inat ions in

Kerala, India, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 7:1, 5-21

To link to this art icle: htt p:/ / dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/ 14766820902812037

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtcc20http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditionshttp://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditionshttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14766820902812037http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtcc20 -

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

2/18

Socio-cultural transformations through tourism: a comparison

of residents perspectives at two destinations in Kerala, India

Leena Mary Sebastian and Prema Rajagopalan

Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai,600036, India

(Received 28 July 2008; final version received 3 February 2009)

Kerala, a state in Southwestern India, evolved into a prominent international tourism

destination primarily by linking tourism experiences with nature. Although sufficientsignificance has been accorded to tourism as a development strategy in Kerala,tourisms contributions to the development processes and the sustainability of tourismactivities remain unexplored. Though tourism impacts have been extensively studied,researchers have rarely compared socio-cultural transformations in destinations withand without a planned intervention in tourism. This paper compares residents

perceptions on socio-cultural impacts of tourism at Kumily and Kumarakom inKerala. The article explores whether tourism activities in Kumily, with its plannedintervention, are more sustainable than in Kumarakom, without any interventions.The conversion of ex-poachers into forest protectors and the involvement of themarginalized people in community-based ecotourism are a few among the manytransformations that have occurred at Kumily while haphazard tourism developmentat Kumarakom gave rise to several socio-cultural challenges. Primary data were

collected through residents survey, and the findings indicate that Kumily with its planned intervention has a more sustainable tourism development pattern thanKumarakom.

Keywords: socio-cultural; residents perceptions; planned intervention; Kerala

Introduction

The socio-cultural impacts of tourism have received increasing attention from researchers

since the 1970s. Socio-cultural transformations engendered by tourism on host commu-

nities include changes in traditional lifestyles, value systems, family relationships, individ-ual behavior and community structure (Ratz, 2000). Scholars have used stage-related

models like Doxeys (1975) irritation index or Butlers (1980) destination life cycle

model to analyze tourisms impacts. Studies have examined the influence of diverse

aspects such as monetary benefits from tourism, proximity of respondents residence to

the tourism zone, duration of stay at the destination and community attachment on resi-

dents perceptions on tourism. However, scholars have not compared the socio-cultural

transformations induced by tourism in places with and without a planned intervention in

tourism.

ISSN 1476-6825 print/ISSN 1747-7654 online

# 2009 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/14766820902812037

http://www.informaworld.com

Email: [email protected]

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change

Vol. 7, No. 1, March 2009, 521

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

3/18

Tourism is viewed as a viable strategy to foster development in Kerala. The states

development experience has won much international acclaim due to its spectacular achieve-

ments in the social sphere. However, critics question the sustainability of the Kerala model

of development since economic growth lags behind the corresponding social development

indicators (Heller, 2000). Conscious efforts are made to expand the service sector in Kerala,

and in this context, tourism gained significance. With 7.70% contribution to the GDP, the

tourism sector is a major contributor to Keralas economy (Economic Review, 2007).

Planned interventions in tourism are increasingly deployed as sustainable strategies to

further develop tourism at several locales in the state. The prominence accorded to tourism

in Kerala makes sustainable and responsible tourism practices unavoidable (Netto, 2004).

Tourism activities in Kerala are inextricably linked with nature. This paper attempts to

compare socio-cultural transformations at two nature-based tourism destinations, Kumily

and Kumarakom. It specifically looks at whether tourism activities in Kumily, with its

planned intervention, are more sustainable than in Kumarakom, where there are no inter-

ventions. Residents support is crucial for sustainable tourism development, and hence,

this study looks at permanent residents perspectives on socio-cultural impacts of tourism.

Literature review

Sustainable tourism, a sub-branch of sustainable development, has attained widespread

acceptance in academia and practice. Tourism development will be sustainable if only it con-

siders the economic, social, environmental and ethical aspects of the host region (Mbaiwa,

2004). Tourism offers immense opportunities and challenges simultaneously, and hence sus-

tainability should be ensured. Numerous studies consider residents perceptions and atti-

tudes towards tourism (Allen, Long, Perdue & Kieselbach, 1988; Liu & Var, 1986;

Mason & Cheyne, 2000). Studies suggest that benefits such as employment opportunities,increased revenue generation, infrastructure improvement and enhanced standard

of living often motivate local communities to adopt tourism (Archer & Cooper, 1998;

Lindberg, 2001; Liu & Var, 1986). Researchers have also dealt with the undesirable conse-

quences of tourism in destination communities such as inflation, leakage of tourism revenue,

changes in value systems and individual behaviour, crowding, littering and water shortage

(Buckley, 2001; Ceballos-Lascurain, 1996; Mathieson & Wall, 1982).

Despite the substantial research on sustainable tourism, only a few studies have

focussed on states attempts to mitigate the adverse social impacts of tourism in developing

countries (Brenner, 2005). Studies show that interventions enable local communities to

maximize gains and minimize losses from tourism. Planned intervention refers to policies,

programs, plans, projects and its implementation by government and development insti-

tutions including research bodies (Long, 1984). Local contextual features into which any

intervention is implemented should be well understood, for from this context an interven-

tion takes its meaning and probability for success (Lepp, 2008). In the absence of formal-

ized intervention or planning, the possibilities for communities characterized by

unawareness in tourism and outside investments, to benefit from tourism is minimal

(Campbell, 1999). Long (2001), however, points out that outcomes of an intervention

may differ from the initial plan.

Comparison of tourism development scenarios at Kumily and Kumarakom

Kumily and Kumarakom were selected for the study as they have approximately similar

social settings, which permit comparisons about the effect of planned interventions on

6 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

4/18

sustainability (Figure 1). Thekkady, an international tourism destination, is part of the

Kumily Gram Panchayat.1 Tourism activities at Thekkady focus on the Periyar Tiger

Reserve (PTR). The PTR, with 777 km2, is a biodiversity hotspot in the Western Ghats.

Kumarakom is famed for enchanting backwaters, paddy fields, mangroves, bird sanctuaryand canals. The Vembanad Lake that forms an integral part of Kumarakom is a significant

constituent of the Vembanad-Kol2 Wetland system.

Despite their underlying commonalities (Table 1), Kumily and Kumarakom have dis-

similar tourism development patterns. In Kumily, it was significantly influenced by a

planned intervention ensuing high tourists host interaction, whereas in Kumarakom,

tourism was shaped largely by the demand for a backwater destination. The spontaneous

tourism growth in Kumarakom resulted in minimal local involvement and touristhost

interaction. The hotels/resorts developed by the private sector are exclusive touristicspaces, segregating tourists from locals. Further, most of the hotels/resorts are expensive,typically visited by high-spending tourists. Kumily has diverse accommodation facilities

attracting tourists with different spending capacities. To compare, in 2004, 378,830

domestic and 36,543 international tourists visited Kumily. Kumarakom received 30,416

domestic and 16,860 international tourists in 2004.

Figure 1. Kerala tourism map.Source: Prokerala.com.

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 7

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

5/18

The two cases: Kumily and Kumarakom

Kumily

Kumilys evolution into a renowned tourism destination is linked with a planned interven-tion at PTR. The reserve had several conservational issues such as poaching, sandalwood

smuggling, marijuana cultivation and bio-mass dependence. Conflicts existed between

the Forest Department (FD) and locals regarding the resource use (Gurukkal, 2003). The

majority of the fringe area inhabitants are poor. To some extent, forest exploitation could

be connected with poverty. Kumily is a transit point to Sabarimala.3 Littering associated

with Sabarimala pilgrimage and mass tourism activities were additional concerns.

As part of the multi-state India Eco-Development Project, an intervention was

implemented at PTR during 19962001 with financial assistance from World Bank and

Global Environment Facility. The project aimed at biodiversity enhancement in PTR

(Thampi, 2005). The core strategies were reduction in unsustainable resource dependence

by providing sustainable livelihoods to financially marginalized fringe area inhabitants and

involving locals in conservation.

One among the activities initiated was community-based ecotourism (CBET) that led to

positive effects such as community development and conservation. Jobs in Eco-lodges and

Tribal Heritage Museum and as guides, patrolling squads, trackers, etc., significantly

reduced the poverty among the scheduled caste (SC)4 and scheduled tribe (ST). The inter-

vention transformed ex-poachers into forest protectors, providing tourism jobs. A major

share of the CBET revenue goes to the community welfare fund. CBET programs are con-

servation-oriented, jointly developed by the locals and FD authorities. During the interven-

tion, numerous capacity building and environmental awareness programs and cleaning

campaigns were organized. For instance, on 28th of every month, plastic was removedin Kumily, involving all the stakeholders.

Following the CBET, the locals became actively involved in tourism. Tourism activities

at Thekkady effectuated small-scale tourism enterprises in Kumily town and nearby regions.

The locals offer diverse facilities and attractions such as homestays, plantation tours and

elephant safaris. Subsequent to intervention, Periyar Foundation, a state-owned public

trust, was established to sustain the activities.

Kumarakom

Kumarakoms emergence as a Kerala tourism icon could be attributed to the demand for

a backwater tourism destination. Kumarakom gained attention when the Taj Group, one of

Indias leading hotel chains, opened its heritage resort in 1989. It played vital role to set off

private sector investments here. Decline of tourism in Kashmir following the outbreak

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics of Kumily and Kumarakom.

Parameters Kumily Kumarakom

Population 33,722 23,771Literacy rate in percentage 83.63 96.5

Households below poverty linein percentage

57.48 56.68

Major occupation Agriculture, animal husbandry,quarry, daily wage labor,tourism

Agriculture, fishery, lime-shellcollection, daily wage labor,tourism

Source: Panchayat level statistics Kerala (Department of economics and statistics, Government of Kerala, 2006).

8 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

6/18

of terrorism shifted the focus of promotional activities at the national level (Kokkranikal &

Morrison, 2002). The resemblance of kettuvallams, used to carry cargo through inland

waterways, to the houseboats in Kashmir was advantageous to Kerala.The transformation

of kettuvallams into a tourism attraction in the early 1990s simultaneously facilitated

Kumarakoms tourism. Further, the National Geographic magazines millennium edition

describes Kerala as one of the 10 paradises found and its write-up on Kerala features

Kumarakom mostly.

The socio-economic scenario of Kumarakom in the 1990s was conducive to tourism

development. The traditional occupation of villagers such as agriculture and fisheries

were declining and became an unsustainable means of livelihood,5 especially for the

poor. Tourism was well received by the villagers (Padmanabhan, 2006), who anticipated

that tourism would enhance their declining economy. Initially, tourism establishments

were constructed parallel to the lakefront. Eventually, scarcity of land led to the conversion

of paddy fields into tourism sites. Access to the lakefront that served as common property

resource was adversely affected by the resort enclaves.

As per the Conservation and Preservation Act 2005, Kumarakom was declared aSpecial Tourism Zone to safeguard against any irreversible impact on its fragile ecosystem.

However, the guidelines stipulated for tourism activities and further tourism development

have not yet been implemented.

Methodology

This article is part of a larger ongoing study that investigates multi-stakeholders perspectives

on socio-cultural, economic and environmental sustainability of tourism development.

However, the present paper focusses on permanent residents perceptions on socio-cultural

impacts of tourism. It relies largely on the results of pilot studies conducted at Kumily and

Kumarakom.Yin (1994) argues that case study research is pertinent to exploratory studies since it

provides an in-depth and first-hand understanding within real-life context. For this

purpose, a case study approach was adopted. The key characteristic of case studies is the

use of multiple sources of evidence to attain the best possible answers to the research ques-

tions (Silverman, 2000). Though qualitative data are predominant, case studies may adopt

both qualitative and quantitative methods (Yin, 1994). Scholars point out that qualitative

method is more insightful to understand tourism as a social process (Gjerald, 2005).

Since this paper is on socio-cultural transformations, qualitative data predominate. The

period of reference of the study was 2000 2007, as significant changes occurred in

Kerala Tourism since 2000. The paper also draws on various government reports and docu-ments, published and unpublished reports and studies pertaining to the study areas.

During the first stage of the study, in-depth interviews were conducted with beneficiary

and non-beneficiary permanent residents. Previous studies identify economic reliance on

tourism as a significant factor influencing residents perceptions. For the purpose of this

study, beneficiaries of tourism included respondents employed in tourism and associated

occupations. A heterogeneous group of respondents were chosen to ensure maximum

variation and richness of data. An interview guide was prepared based on the literature

review of similar studies. Some dimensions of the interview guide were perceptions

towards tourism and tourists, residents involvement in tourism, tourism and community

development, states role in tourism development and the merits and demerits of tourism.

Interviews lasted from 20 min to 1 h. They were all taped and subsequently transcribed.

To attain a holistic view, informal interviews were carried out with the officials of

Tourism Department, FD and Gram Panchayat. The researcher also undertook on-site

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 9

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

7/18

observation of touristhost interactions and participated in events and discussions linked to

tourism.

For the second stage of the study, a survey instrument was prepared based on the

insights from the first stage of the study and a review of relevant literature (Gezici,

2006; Gjerald, 2005; Mbaiwa, 2004; Ying & Zhou, 2007). Most questions were a combi-

nation of multiple choice questions, followed by open-ended queries. For instance, respon-

dents were asked about their attitude towards tourism activities, merits and demerits oftourism and tourisms influence on children at the destination. The questionnaire also

measured quantitative aspects such as the income of the respondent and household. The

respondents were selected using purposive snowball sampling based on the following cri-

teria: (i) adequate representation of SC, ST and others; (ii) should be residing permanently

at the destination from 1999 onwards and (iii) should include both beneficiaries and

non-beneficiaries of tourism (Table 2).

Based on the above criteria, a total of 50 respondents were chosen at both the study

areas. The researcher identified and interviewed a few respondents who met the study

criteria. As with snowball sampling, the early participants in turn recommend others who

they know meet the study criteria. The questionnaire was administered orally to the house-hold heads. The interviews lasted approximately from 30 min to 1.5 h. Fieldwork was

undertaken during the months of May and June 2007. As in similar studies, the number

of respondents from various social categories was decided on the basis of informational

redundancy (Gjerald, 2005).

Both the study areas have substantial number of households below poverty line. The

incidence of poverty among SC and ST households is significantly higher than among

others (Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala, 2006). Addition-

ally, intervention at PTR focused on ST and SC. Consequently, it was relevant to explore

the perceptions of various social categories. The study seeks to elicit the changes at the

study areas during 200007, and hence selected residents living in the study area perma-nently from 1999. The rationale for including both beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries of

tourism was to obtain a balanced perspective.

Socio-cultural transformations through tourism

Socio-cultural impacts of tourism are the effects on host communities with direct or indirect

contact with tourists and the tourism industry. These are subjective, not always apparent,

and are often difficult to measure, as, to a large extent, they are indirect (Ratz, 2000).

Consequently, this study explores socio-cultural transformations invoked by tourism

through residents perceptions rather than attempting to measure the actual effects.

Perceptions towards tourists and tourism

The following section analyses residents attitude towards tourists and tourism over signifi-

cant dimensions.

Table 2. Respondents at Kumily and Kumarakom.

Kumily Kumarakom

Respondents SC ST Others SC ST Others

Beneficiaries 3 6 4 4 3 5 Non-beneficiaries 4 4 4 5 4 4Total 25 25

10 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

8/18

Type of tourists preferred

All respondents in Kumily and Kumarakom held favorable attitudes towards tourists visit-

ing their community. Most respondents (Kumily: 84%; Kumarakom: 67%) preferred inter-

national tourists to domestic tourists. Respondents said that international tourists spend

more money and give tips. At both the places, there are instances where international tour-ists have sponsored childrens education. They also pointed out that Western tourists are

well mannered and friendlier. Conversely, respondents criticize North Indian tourists as

rude, arrogant and bargaining. In Kumily, 16% of respondents preferred domestic

tourists because they buy more local products

Kumily is challenged by exposure to health hygiene sanitation risks during the

Sabarimala pilgrimage. Residents reported that over the past few years the Panchayat

took measures to clean Kumily immediately after the pilgrimage season. Residents feel

that, though cleaning activities are primarily due to the presence of international tourists,

it has improved their quality of living. In contrast, 78% of the respondents were concerned

about the way tourism has developed in Kumarakom. For instance, . . . . whoever (tourists)

come and stay in the resorts, we see them only when they go in houseboats (Female

respondent, 38 years, Kumarakom).

At Kumarakom, 22% of the respondents prefer domestic tourists because they do not

appreciate the dress code of the international tourists. A few (8%) respondents said that

only domestic tourists should visit Kumarakom since foreigners bring AIDS. Lack of

knowledge of foreign languages was also mentioned as a reason.

Young day-trippers to Kumarakom are perceived as a threat as they come solely for

alcohol consumption and make sexually suggestive remarks at women. A few cases of

immoral activities and abduction by day-trippers were mentioned. Young day-trippers

are not considered as tourists by residents.

Tourists and community activities

To comprehend the extent to which local culture was incorporated in tourism experiences,

respondents were asked about tourist presence during festivals and other cultural activities.

Ninety-four percent of the respondents in Kumily stated that foreigners often come for fes-

tivals and marriages. All respondents expressed pleasure in sharing their culture with tour-

ists. One spoke of an incident in which a group of tourists who went to watch a movie

shooting ended up acting in it. He felt that it was an experience that the tourists will

never forget. Respondents also mentioned that cultural shows are offered on a commercial

basis as the tourists are enthusiastic about Keralas art forms.

While visiting the tribal colony, tourists enter houses if ceremonies occur. Tribalsexpressed happiness and pride in entertaining foreigners. A few tribal art forms were

revived for tourism. This respondent represents the view of most tribals,

Our children are excited to see them. Even we enjoy their presence. We perform traditionaldance for them. Some come to our temple. Only after people started coming to our colony,we learned to communicate. Earlier we were shy and scared, and used to hide seeing outsiders.(Male respondent, 39 years, Tribal, Kumily)

However, a tribal woman expressed dislike over tourists taking their photographs without

permission.

Conversely, in Kumarakom, only a few tourists attend community entertainment

programs. Respondents said that they would be happy if tourists attended local functions.

A few residents perform in hotels and resorts for tourists. Residents also mentioned

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 11

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

9/18

that foreigners get married in temples in a traditional manner, where they often give

big donations. Tourists rarely go for village tours escorted by guides who are not

from Kumarakom. Residents consider it an honor, if foreigners visit their marriage or

festivals.

Tourists within the destination

Another resemblance is that residents have no dislike towards tourists presence at both the

destinations. In Kumily, the dominant attitude is that tourists should be everywhere, they

are our livelihood source. Respondents residing away from the tourist zone wish that more

tourists would visit. For security reasons, outsiders are not encouraged within the tribal

colony, located in the PTR fringes. Hence, tribals are not permitted to operate homestays

within their colony.

Foreigners should come to our colony. Facilities should be developed inside the colony toattract them. The department doesnt permit tourists to stay within the colony. We had proposeda tree house, but they (forest department) opposed. Many locals are constructing houses liketribals and making money . . . but we cannot. (Male respondent, 60 years, Tribal, Kumily)

However, in Kumarakom, respondents said that tourists hardly come out of the resorts.

They see tourists only when they travel in taxies or houseboats. Most respondents expressed

their desire to see tourists near their locality.

Merits and demerits of tourism

Respondents were asked about the primary merits and demerits of tourism. Residents in

Kumily perceive more benefits than costs from tourism. Most (88%) respondents in

Kumily did not report any demerit.

Most residents reported more than one benefit from tourism. For 84% of the respon-

dents, including tribals, economic opportunities from tourism constitute the primary

merit. Additionally, infrastructural development, foreign language skills, cleaning activities

at Kumily, environmental awareness and increased demand for spices are perceived as the

merits of tourism.

Kumily was a backward region. Now most people have money. Every house has vehicle. Allthese changes are because of tourism. We know how to handle guests. Even those who haventgone till seventh standard speak seven languages. Now we manage household things better . . . .

(Male respondent, scheduled caste, 53 years, Kumily)

Another resident perceives the availability of better educational facilities in Kumily as

the merit. According to him, Kumily lacked educational institutions. On completion of

10th standard, residents went to other places for further studies. Now, people from other

places come to Kumily for education. This change in the educational scenario was facili-

tated by infrastructure, which was developed for tourism.

However, a few respondents said they lack resources to invest in tourism businesses. A

Panchayat authority stated that tourism is beneficial only for the capitalists. The major

demerits are pollution from vehicles and plastic and crowding. One respondent expressed

fear that in future Kumily might become infamous like Kovalam.6

In Kumarakom, there was a reversal in the response pattern with 76% reporting that

there are no merits for the locals through tourism. Some respondents (17%) consider

increase in land value as the most important benefit of tourism. Other merits mentioned

12 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

10/18

were the international fame Kumarakom has earned, better roads, jobs in resorts and tips to

houseboat employees. A few (7%) said that fisher folk have gained due to the increased

demand for fish. Nonetheless, increase in fish prices has made fish that constituted a signifi-

cant part of local communitys diet unaffordable.

Ninety-two percent of the respondents perceive that tourism gave rise to several demer-

its at Kumarakom. Seventy percent of the respondents consider the contamination of back-

waters with garbage and oil from boats as the biggest threat. Kumarakom forms a part of

Kuttanad, a predominant rice growing region in Kerala. Respondents felt that the conver-

sion of paddy fields into resorts adversely affects their livelihoods. Other demerits

of tourism were increase in immoral activities, alcoholism and an increase in the cost of

living.

Future tourism activities

Respondents (92%) in Kumily desire increased tourism development, as it leads to overall

community development. The respondents pointed out that tourism boosts local economy,improves living standards, generates more jobs, develops new transportation facilities,

raises land values and improves communication skills. Nonetheless, one tribal expressed

anxiety that if tourism becomes lucrative, tribals might be relocated. Those who disfavored

tourism expansion were anxious about outsiders settling permanently, particularly Kashmiri

handicraft dealers. Handicraft traders from other states of India, predominantly from

Kashmir, have settled in Kumily to engage in tourism trade. Eighty-six percent of the respon-

dents anticipate an increase in tourist numbers, and the rationale was again community

development.

In Kumarakom, 72% of the respondents disapproved further tourism development.

They stated that tourism has engendered severe environmental damage. A few (18%)

respondents felt that with further expansion of tourism there will be no jobs for the

locals. Livelihoods of most of the residents were dependent on Vembanad Lake. Hotels

and resorts dump garbage into the backwaters, and this leads to depletion in fishery

resources. Fifty-six percent of respondents felt that the number of tourists should not be

increased. One respondent pointed out that with the rise in land value, the locals are

unable to purchase any land in Kumarakom.

In the past, Kumarakom was a much better place to live. If we further promote tourism what hashappened in Nandhigram5 will happen here. Locals do not have enough jobs with tourism. If

possible the entire tourism activities should be stopped in the village.

Those who desire tourism development in future anticipate more job opportunities, better

infrastructural facilities and increase in land values.

Influence of tourism on community life

Relationship among members

While most respondents in Kumily felt that tourism has not effected much change in the

relationship among the members, a few involved in tourism business felt that cooperation

has increased. Two tribal communities, Mannan and Paliyan, relocated from PTR to

Kumily, are descendants of aboriginals who came to Kumily from Madurai district in

Tamil Nadu in the seventeenth century and are not aboriginals of the area. Interaction

between tribals and other residents was minimal in the past. The tribals observed a

change in the attitude of other residents following the implementation of IEDP. Previously,

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

11/18

the rest of the community considered tribals uncivilized, unclean and could be easily fooled

in their transactions. As they became associated with the FD and obtained tourism jobs

within PTR, the tribals gained respect from locals. The tribals stated that, due to better

mathematical skills achieved through the intervention, they are not cheated by locals in

transactions.

On the other hand, residents in Kumarakom felt that relationships among community

members have decreased due to out-migration. Also, residents who sell part of their land

or paddy field become rich unexpectedly and many of them have settled in interior areas

of Kumarakom. Respondents observed that these residents do not mingle much with the

rest of the community, since they feel their social status has improved. The tribals in

Kumarakom mentioned that they do not maintain relationships with other members in

the community, though this situation was not a consequence of tourism.

Communitys identity and pride

Residents at Kumily and Kumarakom perceive that the communitys identity and pride haveimproved through tourism. Despite this general optimistic view, one respondent expressed

her surprise at how an unclean destination like Kumarakom could be on the international

tourism map.

Residents mobility within the destinations

In spite of strict conservational measures at PTR, fringe area inhabitants could access forest

for subsistence. Most respondents (71%) were content with the existing control over the

reserve as it leads to better conservation. A few residents (13%) engaged in tourism felt

that forest officials are partial in their approach. They said that the FD is interested in pro-

moting the interests of tribals alone and discourages tourism by charging foreign nationalswith higher entry fees. This deters international tourists from visiting Kumily and in turn

tourism business suffers.

The Vembanad lake front in Kumarakom served as a place for social gatherings but,

following the construction of resorts, the locals were denied access. Tribals said they suf-

fered from suffocation due to the restricted movement of air resulting from the huge resort

walls. Fishermen also complained about the humiliation faced when they entered resort

property following a boat capsize or wreck. A few stated that, in future, to see the back-

waters, they would have to travel in boats like tourists.

Occupation

The occupational patterns at both the destinations are notably influenced by tourism. In

Kumily, residents have diverse opportunities both in formal and informal tourism

sectors. Residents are engaged in tourism activities within PTR, hotels, homestays,

plantation tours, restaurants, shops and as tourist guides. However, in Kumarakom,

tourism employment is confined largely to jobs in hotels and resorts, except for a few

homestays.

The hotel jobs, available to residents at both places, are generally semiskilled or

unskilled, with low remuneration. Gender-wise, women gain more employment in hotels,

either in housekeeping or gardening. There is a difference in the attitude towards hotel

jobs at both the places. Many respondents (68%) in Kumily said that they dislike jobs in

hotels due to the low pay structure, whereas the residents (72%) in Kumarakom complained

that locals get very few jobs.

14 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

12/18

Respondents in both places said that only catering or hotel management qualified

youngsters with influence got permanent jobs in the formal hospitality sector. Nonetheless,

a few hotels give employment in their branches at other places. Respondents view this as a

measure adopted by hoteliers to avoid issues such as strikes and trade unionism as it will

take time for the employees to get acquaintances in new places.

In Kumarakom, residents were involved as daily wage laborers during the construction

phase of resorts. The respondents spoke of conflicts between residents and hoteliers over the

low wage structure. Also, some resorts gave employment to laborers from other places such

as Tamil Nadu and Nepal as they were willing to work for lower wages than locals. The

construction of a few resorts was halted temporarily due to the involvement of local politi-

cal parties. Now the wage structure in Kumarakom is decided jointly by hoteliers and trade

unions. Residents said that the involvement of political parties has both merits and demerits.

For instance, hoteliers are now scared to employ locals.

A shift from traditional occupations, especially agriculture, is observed at both Kumily

and Kumarakom. A few residents in Kumily offer plantation tours since it is less laborious

and has more flexibility and profit than farming. Tourism enterprises such as homestays areof high societal recognition in Kumily. Marginalized sections such as tribals are involved in

tourism activities within PTR. The tribals feel that those with tourism jobs are accorded a

relatively higher status within their community. Also, they perceive that their occupations

within PTR made them more acceptable to the local community. Prior to the intervention at

PTR, tribals were dependent on forest resources and agricultural labor for subsistence.

Respondents also perceive that the spices trade in Kumily has benefited from tourism.

In Kumarakom, respondents mentioned that locals are reluctant to engage in paddy cul-

tivation. Agriculture is considered laborious, less remunerative and of low status. Many are

selling their paddy fields due to increase in land prices with the development of tourism.

A few respondents (9%) said that construction of resorts has caused geographical mobilityof laborers from Kumarakom as many are unable to continue with their occupations that

were dependent on backwaters. Another related trend observed in Kumarakom is the occu-

pational mobility of non-traditional fishermen into fishery due to the higher fish price.

Out-migration of residents

Tourism often generates land requirements and out-migration of residents for various

purposes. These aspects were analyzed to realize its magnitude and linkage, if any.

In Kumily, 80% of the respondents stated that the out-migration rate is insignificant. Most

residents (73%) do not want to sell their homes and leave Kumily. Nonetheless, respondents

were happy about the exorbitant land values. Some (19%) felt that, only those who are notable to invest or gain from tourism out-migrates. A few (10%) pointed out that those who

have daughters sell their property for marriage expenses including dowry. One respondent

voiced that people sell their land as it is difficult to get agricultural laborers.

Tribals, in Kumily, cannot sell their property since they have not yet obtained land titles.

One tribal respondent said,

we dont have pattayam (land title) for our land, so cannot sell it. We cannot even rent ourhouses. We could move to places where we will getpattayam. We are not interested to go any-where. This is thebesttribal colony in Kerala. Kumily is thebestplace for common people to live.If we go elsewhere our people will not get tourism jobs. (Male respondent, 37, tribal, Kumily)

In contrast, 92% of the respondents in Kumarakom reported that the out-migration rate is

high. The major reason was economic gain through increased land values. Those who

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 15

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

13/18

sell invest in rubber estates elsewhere. A few who sold land, settled in near-by and interior

regions. Investors are interested in purchasing several plots together for resort development.

Hence, residents often sell plots together to ensure maximum profit. Respondents perceive

that land brokers gain the most in transactions.

There were instances of residents losing money earned through land sale, due to incom-

petence in managing the money. A few migrants came back to Kumarakom since they did

not thrive in these places. Residents said that the entire lakefront has been sold out. A few

residents sold their property to become houseboat owners and are now well-off. The back-

water contamination and drinking water scarcity also led to out-migration. Increased alco-

holism and immoral activities with tourism were also causes for out-migration, particularly

among those with girl children.

Perceptions on tourisms impact on standard of living and safety

In Kumily, 88% of the respondents perceive that living standards have improved, with 64%

relating it with tourism. Tribals view this as the achievement of Eco-Development Commit-tees, an institutional mechanism established to implement the intervention. Ninety-six

percent of the respondents consider Kumily safer with reduced crime, poaching, alcoholism

and prostitution due to strict surveillance and better awareness. Only one respondent felt

that Kumily has become less desirable because of safety concerns.

Conversely, in Kumarakom, only 24% of the respondents perceive that the standard of

living has improved due to tourism. Sixty-one percent of the respondents said that safety

within Kumarakom has decreased with tourism. Respondents said that they felt insecure

with strangers around. A few (12%) felt that anti-social elements within Kumarakom are

taking advantage of tourism. In general, the respondents felt that crime rate was not affected

by tourism.

Children and tourism

In Kumily and Kumarakom, children are not exploited by the tourism industry, either sexu-

ally or as child laborers.

At Kumily, children participate in environmental campaigns and cultural activities as

part of various tourism activities through their schools. Residents are proud about childrens

foreign language skills, acquired due to the interaction with tourists. Residents motivate

their children to study well and to learn English in particular for future tourism jobs.

Previously, tribal children were reluctant to go to school. But now, tribals encourage

their children to complete at least high school for better chances through tourism. A fewtribals (7%) said that they did not qualify for tourism jobs within PTR due to insufficient

schooling.

Many good change after ECO. Youngsters get tourism jobs. We struggled with elephants in theforests. Now, we are better off. . . . I tried for tourism jobs, they say education is less. Daughteris studying in 10th. At least she will get a tourism job. We are in darkness, our children shouldescape. (Male respondent, 39 years, tribal, Kumily)

Boating in Periyar Lake forms a major tourist attraction for possible wildlife spotting. Only

limited boats are available, and the FD explains this to be in line with the sustainability

measures. There is a huge demand for boat tickets, especially during peak season. On

most days, tickets are sold out in the morning itself, usually purchased by agents and

guides. These are often resold to tourists at higher rates. Agents often hire children to

16 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

14/18

stand in queues early in the morning to purchase tickets. Children view it as a source of

pocket money as the work is not time-consuming.

In Kumarakom, most respondents said that children have no role in tourism. Foreigners

give pens and sweets to children and occasionally join children in fishing. However, a few

respondents (14%) said that tourism is promoting beggary among children. Some respon-

dents complained that children have lost their interest in studies because of tourism activi-

ties in the village. Houseboats often halt in front of schools and children get easily distracted

by them. Children skip school and go after houseboats and tourists. The tribals mentioned

that the rich in the village send their children to study in nearby towns so that they are not

distracted by tourism.

A few children do small tourism jobs during weekends for pocket money. Alcohol

is easily available at these places and employers often encourage children to take drinks.

Consequently, alcoholism has increased among school children. A Panchayat official men-

tioned that there are instances when children were caught capturing sexually explicit photo-

graphs of female tourists on mobile phones. Often parents are unaware about these

activities, thinking their children are at school.

Relationship with other stakeholders in the destination

With the intervention, the dynamics of social relations between the residents and FD underwent

significant transformations in Kumily. Frequent conflicts between the FD and fringe area

inhabitants were resolved, and financially marginalized were permitted to enter the forest

for subsistence requirements. For instance, permits were issued to the traditional fisherman

among the tribals. Simultaneously, the fringe area community reduced forest exploitation con-

siderably. However, the dispute between local tourist guides and forest authorities prevails. The

guides feel that stringent conservational measures at PTR stand in the way of their livelihood.

Frequent conflicts occur between residents and handicraft dealers. Residents involved in

tourism business perceive that, Kashmiris take away the tourism money. Most residents

(72%) complained that the Kashmiris do not mingle with locals to protect their business

secrets. Respondents perceive Kashmiris to be associated with terrorism, which in turn

might undermine Kumilys peace.

In Kumarakom, a conflict of interest exists among residents and tourism businesses.

Respondents reported that resorts and houseboats dump garbage, including human

excreta, into the water. Numerous houseboats and speed boats that ply in the backwaters

generate a heavy load of waste that pollutes its water and affects fish movements. This

has a direct impact on the livelihoods of fishermen dependent on lake resources. Further,

there are conflicts between houseboat drivers and traditional fisherman. The fishing netsused by the fisherman often get entangled with houseboats.

Who benefits from tourism activities at the destination?

Most respondents (72%) in Kumily perceive that the locals benefit the most from tourism.

The residents view tribals to have benefited the most from tourism. Tribals, on the other

hand, had diverse responses. Some felt that residents other than tribals, particularly those

in Kumily town, benefit the most. While others said that tribals themselves have gained

the most through tourism.

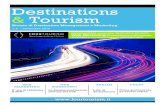

In Kumarakom, 76% of the respondents felt that outsiders benefit from tourism

(Figure 2). Outsiders include resort owners, hoteliers and those employed in these establish-

ments from other places. Those who stated that residents gain the most referred to locals

who sold their properties.

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 17

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

15/18

Conclusion

It is evident from the study that Kumily with its planned intervention has a more sustainable

tourism development pattern than Kumarakom. The intervention at PTR was successful as

it considered site-specific socio-cultural features, brought about societal transformations

through awareness and addressed communitys socio-economic requirements through

sustainable livelihoods.

The intervention initiated many institutional changes in Kumily. It resolved the long-standing conflict between the locals and FD over subsistence needs and conservational con-

cerns. The CBET enhanced the probability to retain tourism benefits within the community.

Residents perceive that tourism has engendered better employment opportunities, enhanced

the well-being of marginalized people, increased societal acceptance of tribals, revitalized

tribal art, reduced alcoholism and immoral activities, facilitated learning of foreign

languages and created demand for local produce such as spices. Environmental education

instigated positive attitudinal shift towards conservation among the locals. However, con-

cerns such as conflict between handicraft dealers and locals due to insufficient trust,

unauthorized guiding, rise in the price of essential commodities and crop-raiding that

affects the health of tribals prevail. Furthermore, the prominence given to tourism mightlead to unsustainable dependence on tourism, abandoning traditional occupations such as

agriculture.

Conversely, the lack of benefits from tourism, backwater pollution by houseboats and

hotels and the socio-cultural and livelihood challenges triggered by tourism have generated

anti-tourism attitude in Kumarakom. Most villagers are dependent on natural resources for

livelihoods. Natural resources were deteriorating due to various unsustainable practices.

Tourism activities intensified environmental degradation. The construction of accommo-

dation establishments on the banks of the Vemband Lake rendered backwaters inaccessible

to the fishermen and shell collectors. The conversion of paddy fields for tourism purposes

further undermined the villagers livelihoods. Residents perceive that tourism have

increased alcoholism and immoral activities, brought undesired changes in the value orien-

tation of children, altered community structure due to large-scale out-migration and

increased the price of essential food products such as fish. The upward social mobility of

Figure 2. Perceptions on who benefits from tourism.

18 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

16/18

a few members through land sale widened the gap between the wealthy and the poor. None-

theless, tourism activities resulted in better infrastructure and environmental awareness

among the residents. The incomplete agricultural intervention such as the bund, which

has adversely affected their occupation, might have influenced the residents perceptions.

In Kumarakom, most of the negative tourism impacts are due to haphazard tourism

development and are rectifiable. Through spatial planning, areas appropriate for tourism

and community activities should be demarcated and developed accordingly. This will

improve the quality of life of the residents and prevent conflicts between various stake-

holders. A planned intervention will increase the villagers possibilities to gainfully

engage in tourism. By imparting education to all stakeholders on sustainable environmental

practices and by implementing regular cleaning activities, backwater could be conserved.

Some aspects of the intervention that could be implemented in destinations with

conservational value are linking conservation with tourism, addressing socio-economic

concerns through sustainable livelihoods, converting marginalized individuals as tourism

beneficiaries, shifting environmental attitudes and behavior through education and

regular cleaning activities involving all the stakeholders. However, the success of any inter-vention will also depend on site-specific features.

This article has limitations such as the assessment of sustainability based on residents

perceptions and socio-cultural dimensions alone and small sample size. At present, Kumily

and Kumarakom are part of an ongoing, larger intervention in responsible tourism.

Notes

1. Gram Panchayats are local administrative bodies at the village level in India. They constitute thefoundation of the Panchayati Raj system.

2. Vembanad-Kol wetland is one of the largest estuarine systems in the Western coastal wetlandsystems (Parikshit, 2006). Considering the uniqueness of the region and the threat to its environ-ment the wetland was declared a Ramsar Site in 2002.

3. Sabarimala, located in the Western Ghats of Kerala, is a leading pilgrimage center dedicated tothe Hindu God Lord Ayyappa. Sabarimala gets crowded with devotees during the main pilgrim-age season from November to January.

4. SCs and STs are historically disadvantaged and vulnerable social groups in India. The Indian con-stitution has various provisions for their development.

5. Kumarakom forms a part of Kuttanad region famous for paddy cultivation. As Kuttanad liesbelow the mean sea level, a second round of cultivation was difficult. To restrict salt water intru-sion during summer and to flush out flood waters into the sea during the monsoon, the Thaneer-mukkom barrage was constructed. The incomplete construction work and ineffective operationsgave rise to ecological concerns such as fish reduction and pollution of the backwaters.

6. Kovalam, one of the earliest beach destinations in Kerala, faced severe socio-cultural andenvironmental concerns due to disorganized tourism development. Nevertheless, several projectsare underway to rejuvenate Kovalam.

7. Nandhigram is a village in the state of West Bengal, India. The governments decision to bringthe rural area under the Special Economic Zone policy was opposed by farmers, fearing landacquisitions. This led to violent clashes and loss of life of villagers.

References

Allen, L.R., Long, P.T., Perdue, R., & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The impact of tourism development onresidents perception of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 27(1), 1621.

Archer, B.H., & Cooper, C. (1998). The positive and negative impacts of tourism. In W.F. Theobald(Ed.), Global tourism: The next decade (pp. 6381). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Brenner, L. (2005). State-planned tourism destinations: The case of Huatulco, Mexico. TourismGeographies, 7(2), 138164.

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 19

-

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

17/18

Buckley, R. (2001). Environmental impacts. In D.B. Weaver (Ed.), The encyclopedia of ecotourism(pp. 522). New York: CABI Publishing.

Butler, R.W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management ofresources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 512.

Campbell, L.M. (1999). Ecotourism in rural developing communities. Annals of Tourism Research,26(3), 534553.

Ceballos-Lascurain, H. (1996). Tourism, ecotourism and protected areas: The state of nature-basedtourism around the world and guidelines for its development. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

Department of Economics and Statistics, Government of Kerala (2006). Panchayat level statistics2006, Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Kerala.

Doxey, G.V. (1975). A causation theory of visitorresidents irritants: Methodology and researchinferences, The Impact of Tourism, Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel

Research Association (pp. 195198). San Diego, CA: The Travel Research Association.Economic Review (2007). The information and public relations department, Government of Kerala.

Tourism, (chapter 9). Retrieved May 12, 2008, from http://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdf.

Gezici, F. (2006). Components of sustainability: Two cases from Turkey. Annals of Tourism Research,33(2), 442455.

Gjerald, O. (2005). Sociocultural impacts of tourism: A case study from Norway. Journal of Tourismand Cultural Change, 3(1), 3658.

Gurukkal, R. (2003). The ecodevelopment project and the socio-economics of the fringe area of thePeriyar Tiger Reserve: A concurrent study. Kerala Research Programme on Local Level

Development. Retrieved June 17, 2006, from http://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfHeller, P. (2000). Social capital and the developmental state: Industrial workers in Kerala. In

G. Parayil (Ed.), Kerala: The development experience: Reflections on Sustainability andReplicability (pp. 6687). New Delhi: Zed Books.

Kokkranikal, J.J., & Morrison, A. (2002). Entrepreneurship and sustainable tourism: A case study ofthe houseboats of Kerala. Tourism and Hospitality Research: The Surrey Quarterly Review, 4(1),720.

Lepp, A. (2008). Attitudes towards initial tourism development in a community with no prior tourism

experience: The case of Bigodi, Uganda. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(1), 522.Lindberg, K. (2001). Economic impacts. In D.B. Weaver (Ed.), The encyclopedia of ecotourism

(pp. 363378). Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing.Liu, J., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes towards tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism

Research, 13(2), 193214.Long, N. (1984). Creating space for change: A perspective on the sociology of development.

Sociologia Ruralis, 34(3/4), 168184.Long, N. (2001). Development sociology: Actor perspectives. London and New York: Routledge.Mason, P., & Cheyne, J. (2000). Residents attitudes to proposed tourism development. Annals of

Tourism Research, 27(2), 391411.Mathieson, A., & Wall, G. (1982). Tourism: economic, physical and social impacts. New York:

Longman.

Mbaiwa, J.E. (2004). The socio-cultural impacts of tourism development in the Okavango Delta,Botswana. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 2(3), 163184.Netto, N. (2004). Tourism development in Kerala. In B.A. Prakash (Ed.), Keralas economic develop-

ment: Performance and problems in the post-liberalization period(2nd ed., pp. 269292). NewDelhi: Sage Publications.

Padmanabhan, P.G. (2006). Kumarakom: An insiders introduction. Kottayam: Learners Book House.Parikshit, G. (2006). Vembanad-kol wetland. Retrieved June 27, 2008, from http://www.wwfindia.

org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfm

Prokerala.com. Kerala Tourism Map. Retrieved February 5, 2009, from http://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htm

Ratz, T. (2000). Residents perceptions of the socio-cultural impacts of tourism at Lake Balaton,Hungary. In G. Richards & D.R. Hall (Eds.), Tourism and sustainable community development

(pp. 3647). London: Routledge.Silverman, D. (2000). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. London: Sage Publications.

20 L.M. Sebastian and P. Rajagopalan

http://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.prokerala.com/kerala/maps/kerala-tourism-map.htmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.wwfindia.org/about_wwf/what_we_do/freshwater_wetlands/our_work/ramsar_sites/vembanad___kol_wetland_.cfmhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.krpcds.org/report/Rajangurukkal.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdfhttp://www.kerala.gov.in/economic_2007/chapter9.pdf -

8/2/2019 Tourism Journal7

18/18

Thampi, S.P. (2005). Ecotourism in Kerala, India: Lessons from the eco-development project inPeriyar Tiger Reserve. International Ecotourism Monthly, 13. Retrieved October 21, 2007,from http://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdf

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd ed.). Beverly Hills, CA: SagePublishing.

Ying, T., & Zhou, Y. (2007). Community, governments and external capitals in Chinas rural culturaltourism: A comparative study of two adjacent villages. Tourism Management, 28(1), 96107.

Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 21

http://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdfhttp://www.ecoclub.com/library/epapers/13.pdf