anyondacamera.org/pdfs/Topanga_Canyon_Festival_Packet.pdfby Topanga State Park, the largest...

Transcript of anyondacamera.org/pdfs/Topanga_Canyon_Festival_Packet.pdfby Topanga State Park, the largest...

Topa

ng

a C

an

yon

Fes

Tiva

l

Sunday, 18 March 2018

Topanga Community Center1440 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.

No interior access

Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum1419 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.

• Concert parking with shuttle service; parking attendants will direct you

• Showcase Performances on the Theatricum grounds every 15-20 minutes from 12:45 to 4:30

• Showcase Performances featuring the Eastern European women’s folk choir Nevenka and dramatic readings by Theatricum actors

The Mountain Mermaid (C.E. Finkenbinder, 1930)20421 Callon Dr.

• ChamberMusicinHistoricSites concerts featuring Vogler Quartet with Ian Parker, piano at 2 & 4PM

• Reception between concerts, 3-4PM

• Wildlife Encounter, 3-4PM

• Live Butterfly Exhibition throughout the afternoon

The Topanga Table1861 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-752-6241 Sun. Hours: 8AM-4PM

Inn of The Seventh Ray128 Old Topanga Canyon Rd.310-455-1311Sun. Hours: 9:30AM–3PM, 5:30–10PM

Spiral Staircase Bookstore128 Old Topanga Canyon Rd.310-455-3370Sun. Hours: 9:30AM-3PM, 5:30PM-10PM

Bouboulina108 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-455-1917Sun. Hours: 10AM-7PM

Topanga Canyon Gallery120 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd. #109310-455-7909Sun. Hours by appointment only

Canyon Bistro & Wine Bar120 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd. #119310-455-7800Sunday Brunch: 11AM-3PM, Dinner: 5-9PM

Waterlily Café120 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-455-0401 Sun. Hours: 8AM-4PM

Topanga Mercantile/Candle Co.115 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-455-2876Sun. Hours: 11AM-6PM

Topanga Art Tile137 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-455-3359Sun. Hours by appointment only

Hidden Treasures154 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd.310-455-2998 Sun. Hours: 10:30AM-6:30PM

1

A

E

B

C

D

2

3

TopangaCanyonCivicLandmarks

LocalArtisans, ShopsandRestaurants

Parking: Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum 1419 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.Concert parking with shuttle service; parking attendants will direct you

P

F

J

G

H

I

TopangaCanyon

2

3

1

N. T

opan

ga C

anyo

n Bl

vd.

Cheney Dr.

Callon Dr.

N

To shops & dining

P

A

N. Topanga Canyon Blvd.

S. Topanga Canyon Blvd.

Old Topanga

Canyon Rd.

To The Mountain Mermaid

B/C

E/F

H

G

I

J

Cuesta

Cala Rd.

D

1

Welcome to Topanga Canyon!

The following is excerpted from an article “California Dreamy: The New Scene in Topanga Canyon” by Susan Morgan published in W Magazine, June 2014. It captures the natural beauty and topography of Topanga as well as the Canyon’s dual persona as a secluded artists enclave and a vibrant cultural community.

As you drive up the Pacific Coast Highway from Santa Monica, the shoreline curves around the bay and the mountains tip downward into the sea. Five miles past the city’s amusement pier, with its carousel and neon Ferris wheel, other emblems of Southern California start to appear: the Getty Villa—a model of an ancient Roman country house—crowns an oceanfront cliff; and the Malibu Feed Bin, a rustic red barn selling chicken feed and livestock sundries, hunkers down at the mouth of Topanga Canyon. Turn right here.

The village of Topanga (population 8,289) has long functioned as Los Angeles’s bohemian Brigadoon. Surrounded by Topanga State Park, the largest wilderness area within a city limit in the United States, it’s accessible by just one route: Topanga Canyon Boulevard passes through chaparral-covered hills and steep outcrops of rock, winding along for 12 miles from the ocean to the San Fernando Valley. Since the early 20th century, a scattering of businesses—a rotation of general stores, taverns, spiritual centers, community galleries, and cozy cafes—have come and gone along this main drag. Perhaps emblematic of the latest wave of creatives: The old Bruno’s Dead Dog Saloon—a biker bar nicknamed the Stop and Fight—was recently transformed into Topanga Fresh Market, featuring organic, locavore fare and pressed juice. But some things don’t change. The Inn of the Seventh Ray, a terraced creekside restaurant that opened in 1973 touting “angelic vibrations,” is still festooned with fairy lights and continues to rate as a romantic destination—celebrity trackers report Leonardo DiCaprio, Channing Tatum, and Fergie as regulars. The French-born Museum of Contemporary Art director, Philippe Vergne, and the curator Sylvia Chivaratanond, who are the L.A. art world’s It couple du jour, were married there.

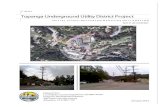

Panormaic view showing Topanga Canyon Road winding its way through the Santa Monica Mountains. Clouds gather above as a storm approaches. (1921)

2

“When you turn off PCH and head up into the canyon, all you can see are those beautiful cliffs and trees,” says the filmmaker Alexander Payne. “You roll down the windows, smell the smells, and I think your blood pressure lowers about five points.” Since 2005, Payne, a devoted Nebraskan, has been dividing his time between a condo in downtown Omaha and a 1930s Topanga retreat boasting fruit trees, live oaks, and spectacular mountain views. [...]

The artist and filmmaker Meredith Danluck and her husband, Jake Burghart, the director of photography for Vice Media, spent six years shuttling between New York and L.A. before happily settling in Topanga four years ago. “We both surf, so being five minutes away from the ocean has been amazing,” Danluck says. “The air here has its own story. Every day it’s something different: citrus blossoms, fireplaces, night-blooming jasmine. And I love watching the Pacific fog roll into the canyon like a slow white river.”

Topanga’s artistic roots date back at least as far as the McCarthy era, when Will Geer—a blacklisted actor and trained botanist—fled Hollywood and bought a parcel of canyon land. With his family, he established a large, working garden and an open-air theater, where Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott performed. In the ’70s, when Geer gained new fame on the hit TV show “The

Waltons” as Grandpa and his children had grown up to be actors, the family created Theatricum Botanicum, now a venerable woodland venue for performances and workshops.

George Herms, a peripatetic beatnik who infuses visual art with a free-flowing jazz sensibility, arrived in Topanga in 1965 for an eight-year sojourn. “It was a creative community unlike anyplace I’d been a part of before—or since,” he says of his circle, which included the late Wallace Berman, one of the West Coast’s most enigmatic and influential artists; and former child actors Dean Stockwell, Billy Gray, and Russ Tamblyn. The artist Peter Alexander arrived a few years later, in 1970. He was living in downtown Los Angeles when land at the top of Tuna Canyon—located on the Malibu edge of Topanga, with a view straight out to the ocean—became available. He and his then wife, the painter Clytie Alexander, and their two small daughters camped out there, planted a garden, and eventually built a house out of timber scavenged from a demolished Union Pacific Railroad building. From their ridgeline, there was only one other inhabited place in sight: Sandstone Retreat, a nudist colony. “We could see little pink things running back and forth,” Alexander remembers. “But what was vivid was a particular sound wave that penetrated the canyon: ice rattling in cocktail glasses.”

Music has long reverberated through the canyon. Although

Topanga Road, 1921

Will Geer

3

the Topanga Corral, a roadhouse on Horseshoe Bend, burned to the ground in 1988, its musical history has grown mythic. In the hippie heyday, the local band Canned Heat pounded out their anthem “Going Up the Country” there; Neil Young, having left Buffalo Springfield to go solo, played; and Taj Mahal delivered the blues. “I remember my dad going to hear the Flying Burrito Brothers in ’68 or ’69,” recalls Wallace Berman’s son Tosh, a writer, who spent a chunk of his childhood in Topanga. “The only people in the audience were my dad and the Rolling Stones.” The musician Jennifer Pearl, of the noirishly psychedelic L.A. band VUM, says that she and her partner in love and music, Christopher Badger, “were magnetically attracted to Topanga’s ethereal forests, musical history, and strange, burnout-’60s-misfit culture.” In 2011, Pearl and Badger emigrated there from L.A.’s Eastside and settled into an apartment that had been the recording studio where Neil Young wrote and produced his 1970 LP “After the Gold Rush”. Embracing “a hideout, hermit lifestyle,” the couple wrote “Laura Palmer/Are You Animal?”—an album produced by their own label, Secret Lodge Recordings.

It’s not hard to understand what draws so many artists to Topanga: wild, wide-open spaces; enforced solitude; and an atmosphere that teeters between insular and inspiring. Perhaps the most dramatic creative compound belongs to the artists Chris Burden and Nancy Rubins, who bought a tract of land atop a mesa in 1981 and, over the years, have acquired an 80-acre spread made up of a modest house, capacious studio buildings, and a

vast collection of airplane parts, vehicles, and architectural salvage that they use to create their sculptures and installations. Three years ago, the artist Sam Falls and his wife, Erin, a director at Hannah Hoffman Gallery, in Los Angeles, landed in Topanga after moving from New York. For Falls, whose process-based work often employs natural elements—rainfall, river water, sunlight—the prospect of working outdoors was a big appeal. The couple soon recruited their friend and former housemate, the artist Joe Zorrilla, who found a tiny cabin on a large property nearby. Zorrilla, who maintains a Mid-City studio, now has what he calls an “outdoor office”—a table where he sits to draw and read. “When I left New York, I wanted to slow things down,” he says. “In the canyon, there are things you couldn’t change even if you wanted to—there’s only one way in and one way out.”

Living within one’s own vision of paradise, Payne says, is central to the Topanga vibe. “Each house in the canyon is an entirely different universe,” he observes. “The only thing that unites them is a sense of creativity, of having your house reflect you in some way. I think that people who live in Topanga have two attitudes going on. One being, I love to be part of a community like this. And the other being, leave me the hell alone.”

George Herms (right), with Wallace Berman, Robert Alexander, John Reed, Los Angeles, ca. 1955.

Neil Young, laughing at Topanga home in 1971

4

Topanga Community Center (est. 1949)No interior access

The Topanga Community Club (TCC) was founded in 1949, originally as the Topanga Woman’s Club, to be a community center for all. The early members joined together to host card and dance parties, cake raffles, bingo games and children’s events, and held rummage sales, sold cookbooks and even donated livestock to support their efforts. A 12-acre parcel was offered to the club in 1950 and a decade later, the shell of the house was built and the mortgage paid, all done by local volunteer labor and love.

In the years gone by, many events and gatherings were held at the Community House. The original Strawberry Festival of the 1960s began here at the House, and over time, this festival evolved into Topanga Days, an annual fundraiser held on the three-day Memorial Day weekend.

The house became the venue for the Topanga Symphony, the annual Nutcracker Ballet, the monthly senior lunches, Topanga Youth Services events, holiday celebrations for children and seniors, the Swap Meet/Chili Cook-off, the Mother’s Day Tea, the Easter Egg hunt, countless community meetings, and youth and adult team sports and exercise classes. Many non-profit groups use the house, including AA, NA, Boy Scouts and, previously, the Topanga Co-Op Preschool.

Topanga Canyon Civic Landmarks

1

Topanga Women’s Auxilary

During World War II, many groups were formed in Topanga, among them the Women’s Auxiliary. They sponsored an old-fashioned community picnic on July 4, 1943 which continued as an annual tradition in Topanga, later becoming Country Fair, Strawberry Festival, Topanga Day to the present day Memorial Weekend Topanga Days sponsored by the Women’s Club.

5

Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum (est. 1933)

• Concert parking with shuttle service; parking attendants will direct you

• Showcase Performances on the Theatricum grounds every 15-20 minutes from 12:45 to 4:30

• Showcase Performances featuring the Eastern European women’s folk choir Nevenka and dramatic readings by Theatricum actors

Long before he founded Theatricum Botanicum, Indiana native Will Geer was well-known for his work on the New York stage, in film, and on radio. By the mid-1950’s, he had relocated permanently to California and had established a successful Hollywood career. His future looked bright. But after being called to testify before the U.S. Congress’ Committee on Un-American Activities, he suddenly found himself blacklisted by the major studios with no viable means of income. For Geer and his young family, the McCarthy Era had arrived.

Relocating to an acreage in Topanga, California, Mr. Geer established a theatre for similarly blacklisted actors and folk singers on the property. Because he held a degree in botany (one of his life long interests) the theater was named for a landmark botany text book, Theatricum Botanicum, which means, quite literally, “a garden theatre.” In the years to come, Geer cultivated not only theater, but a bountiful garden that enabled him and his wife, actress Herta Ware, to earn a living from the sale of vegetables, fruit, and herbs.

With the success of television’s “The Waltons” in 1973, Geer discovered renewed popularity with his portrayal of Walton family patriarch, Zebulon Walton. Now he re-gathered his family (many of whom were working actors in regional theatres across the country) and together they formed a non-profit corporation, The Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum. In those heady days, audiences flocked to free workshop performances of Shakespeare, folk plays, and concerts featuring such well-known artists as Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Della Reese, Burl Ives, and many more.

After his death in 1978, the family (led by their mother, Herta Ware) and a small troupe of dedicated actors tirelessly dedicated their energies to transform Theatricum into a professional repertory theatre, with educational programs and musical events incorporated into its programming.

In 2016, the Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum became a member of The Folger Shakespeare Library Theatre Partnership Program.

Today, under the creative supervision of Artistic Director Ellen Geer (Will’s daughter), the Theatricum has blossomed into a vital creative force that has been recognized internationally for its interpretation of Shakespeare’s work. In addition to an annual summer season of 5 repertory plays, Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum offers year-round classes to actors of all ages, hosts live music concerts, nurtures budding playwrights, and successfully reaches schools and students across the Greater Los Angeles County with the aim of making live theater bloom for generations to come.

Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum stage

2

6

The Mountain Mermaid (C.E. Finkenbinder, 1930)

• Chamber Music in Historic Sites concerts featuring Vogler Quartet with Ian Parker, piano at 2:00 & 4:00pm

• Reception between concerts, 3-4PM

• Wildlife Encounter, 3-4PM

• Live Butterfly Exhibition throughout the afternoon

History & ArchitectureThe historic Mountain Mermaid is now a horticultural retreat for the rejuvenation of mind, body and spirit, and for the preservation of our natural, architectural and historical heritage. It survived the 20th century wearing a variety of hats which have become a part of the lure and lore of this magical setting.

The Mermaid is no stranger to live music - a tradition established more than 40 years ago, when the central great room served as an informal concert hall known as the Mermaid Tavern. Under the direction of former L.A. Philharmonic double-bassist Mickey Nadel and his wife Ann, a weaver, the tavern featured a selection of classical music, inexpensive wines and organic foods one night a week during the early 1970s. It was the last of several different clubs to operate at this location during the building’s 80 plus year history.

The structure’s first role was as the Sylvia Park Country Club, erected in 1930 as the showpiece of Topanga Canyon’s largest residential development. Its architect, C.E. Finkenbinder of Los Angeles, designed the club in the perennially fashionable Spanish style, then at the height of its popularity. The exterior features an arcaded entrance, octagonal tower and espadana parapet recalling California’s missions. Inside, the spacious former lounge boasts a high trussed and beamed ceiling, baronial fireplace and generous views of the surrounding landscape.

When the effects of the Great Depression cut short the growth of Sylvia Park, the club changed hands, operating as the Rancho Topango Country Club during World War II and later serving as an American Legion Hall. The early 1950s saw the structure used as a boys’ school, followed by a long run as the Canyon Club, a popular gay bar. In 1972 the Nadels opened their establishment, taking its name from the pub celebrated by Keats in his Lines on the Mermaid Tavern: “Souls of poets dead and gone / What Elysium have ye known / Happy field or mosey cavern / choicer than the Mermaid Tavern?”

Current owner Bill Burge can take credit for a “My Fair Lady” style transformation which is well documented on his website and in photographs and video. He says, of his twenty year restoration, “The Mermaid’s been this amazing journey. An adventure. A challenge of a lifetime. An exercise in delayed gratification. A work in progress. A wild ride. A labor of love. I have gratitude for the people of this community, the construction gods, for all the rich history and for the benevolent spirit that pervades my premises.”

3

The Mountain Mermaid

7

Butterflys at the Mountain MermaidButterflies are the poster children of the insect world. They suggest warm, sunny days filled with beautiful flowers. Today a large and growing interest in anything to do with butterflies can be seen in such diverse areas as jewelry, clothes, live butterfly releases at weddings, advertisements, festivals, home butterfly gardens, and specialty tours and field trips. In addition, many museums, zoos, and private organizations have opened walk-through butterfly gardens with free-flying butterflies imported from all over the world.

Since our last visit to The Mountain Mermaid, hundreds of native California host and nectar butterfly plants have been planted in designated areas for certain butterflies such as the Monarch, Mourning Cloak, California Sister, and five different kinds of swallowtails. The Mermaid is focusing on bringing back the gorgeous iridescent blue and black Pipevine Swallowtail. In addition to the gardens, enjoy a live butterfly display and plant sale, featuring pesticide free native butterfly plants.

8

Local Artisans, Shops and Restaurants

The Topanga Table 1861 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-752-6241 thetopangatable.com Sunday hours: 8AM-4PM

Seasonal comfort food every day for breakfast and lunch (Sunday brunch). Ingredients are local and organic, and they even bake bread and make sodas with wild sage.

Inn of The Seventh Ray 128 Old Topanga Canyon Rd. 310-455-1311 innoftheseventhray.comSunday hours: 9:30AM–3PM, 5:30–10PM

This fabled destination restaurant offers creekside dining in an idyllic woodland setting at the intersection of two creeks under old sycamores and oaks. The Sunday brunch buffet includes lavender infused mimosa and more than fifty locally-sourced, organic dishes.

Spiral Staircase Bookstore 128 Old Topanga Canyon Rd. 310-455-3370 Sunday hours: 9:30AM-3PM, 5:30PM-10PM

New-Age Bookstore attached to The Inn of the Seventh Ray. Specializes in books about creativity, meditation and spirituality. Beautiful hand-crafted jewelry, natural bath/body and unique gift items.

Bouboulina 108 N Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-455-1917 Sunday hours: 10AM-7PM

Mother/Daughter venture offering original bohemian style since 1980. Handmade purses and tie-dye designs, fringe and fun hippie clothes. Rare vintage, Native American, Navajo and Zuni Jewelry.

Topanga Canyon Gallery 120 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd. #109 310-455-7909 topangacanyongallery.comSunday hours: by appointment only

An artists co-operative founded in 1989, strongly committed to keeping art in the canyon alive. Following the lead of the first Topanga Artists’ Guild in the 1950’s, Topanga Canyon Gallery brings together many well-known and emerging artists from the greater Los Angeles area. Exhibits change monthly.

Canyon Bistro & Wine Bar 120 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd. #119 310-455-7800 canyonbistrotopanga.com Sunday Brunch: 11AM-3PM, Dinner: 5-9PM

French-style cuisine, an eclectic menu of gourmet comfort foods, boutique wines & live jazz highlight this chic, art-filled cafe with a patio.

A

B

C

D

E

F

9

Waterlily Café 120 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-455-0401 waterlilycafe.com Sunday hours: 8AM-4PM

Family owned cafe that features fresh made to order sandwiches, homemade soups, salads and breakfast. Organic ingredients and a gluten free alternative available.

Topanga Mercantile/Candle Co. 115 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-455-2876 topangacandles.com Sunday hours: 11AM-6PM

Eclectic offerings from local artisans. Jewelry, scarves, glass houses, fairy chairs, hand-knit purses and hats, fine art, and metal work artfully displayed among an enchanting array of house made candles inhabiting the most unexpected vessels.

Topanga Art Tile 137 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-455-3359 topangaarttile.comSunday hours by appointment only

A family owned and operated custom ceramic company specializing in hand made porcelain tile fired with hand painted glazes. A variety of techniques are used to create unique high detailed murals with scenes that are brought to life with a wide range of bright colors and textures. Mosaic techniques are used to create specialized murals, architectural sculpture and home furnishings. Topanga Art Tile has produced and installed tile murals throughout the world and in some of the finest houses around, as well as restaurants, hotels and other public spaces.

Hidden Treasures. 154 S. Topanga Canyon Blvd. 310-455-2998 topangacandles.com Sunday hours: 10:30-AM-6:30PM

Eclectic offerings from local artisans. Jewelry, scarves, glass houses, fairy chairs, hand-knit purses and hats, fine art, and metal work artfully displayed among an enchanting array of house made candles inhabiting the most unexpected vessels.

H

Print Sources:

“California Dreamy: The New Scene in Topanga Canyon,” Susan Morgan, W Magazine, June 25, 2014

“Topanga Community Center” at www.topangacommunityclub.com

“Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum” at www.theatricum.com

“The Mountain Mermain” at www.themountainmermain.com

Images:Topanga Canyon historic landscapes [Courtesy of Water and Power associates, Digital photo archive]; Topenga Women’s Auxilary [California State University Northridge, Obviatt Library, Digital Collections]; Will Geer [Courtesy of GoldenGlobes.com]; George Herms & Friends [Courtesy of East of Borneo Magazine]; Neil Young [Courtesy of Henry Diltz]; Topanga Community Center [Courtesy of Wildapricot.com]; The Will Geer Theatricum [Courtesy of Trip Advisor]

G

J

I

1

Lisa MarksThe Guardian, August 8, 2012

Will Geers’ Theatricum Botanicum, the idyllic setting of the four-day California festival, began life as a refuge for actors who were persecuted in the name of anti-communism

The audience arriving for the opening night of the 8th Topanga film festival at the Theatricum Botanicum are greeted by a veritable wooded wonderland. Think Sundance in the Shire, with drinks in front of the Hamlet Hut, a dusty brook and musicians strumming acoustic guitars under giant oak trees.

A trio of belly dancers perform on the wooden stage of the majestic open-air auditorium before the first night screening of Kyle Ruddick’s One Day on Earth, while the half moon throws out a glowing silvery light. “It’s beautiful here, just perfect,” says festival director Urs Baur, to a cheering crowd, who in deference to the festival’s wolf logo, collectively howl at the moon.

The Theatricum Botanicum, nestled deep in Topanga canyon, which sits east of Malibu, in the Santa Monica mountains, is a Pandora for actors. But the lush campus, which includes Woody Guthrie’s tiny wooden cabin (his home for part of the Fifties), belies a painful inception.

Actor Ellen Geer, the theatre’s artistic director, was only 10 years old when her actor father, Will Geer, best known for his role as Grandpa Zeb Walton in The Waltons television series, was hounded out of Hollywood for refusing to testify at the investigations by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), in New York, in 1951.

Her mother, the actor and activist Herta Ware (best known for her role as Rosie Lefkowitz in Cocoon), found the land which they purchased for $10,000, and it soon became a refuge for a community of blacklisted actors, including Virginia Farmer, Anne Revere, Jeff Corey and John Randolph, who had nowhere else to go or perform. Will Geer, an enthusiastic botanist, had earlier graduated from the University of Chicago with a degree in horticulture before heading to Broadway. Theatricum Botanicum means theatre of plants, and the actor made it his mission to grow every plant mentioned in a Shakespeare play. (Figus carica; “O excellent! I love long life better than figs.” Charmian, Antony and Cleopatra, says one inscription in a flower bed). Ellen and siblings were taught the plants’ Latin names, but while this seems charming, Walton-esque even, the hearings cast a pall over the family that tore them apart, and took almost 20 years to heal.

“Pop had been big on Broadway but he came to Hollywood and made a lot of money working as a supporting actor,” explains Ellen, who is currently appearing in the theatre’s production of “The Women of Lockerbie”.

“We lived in a big fancy house in Santa Monica, and went to big fancy schools. He was huge and extraordinary ... I can say that even though he was my dad. Then one day there was a knock on the door, he was handed a pick slip, and everything changed.”

Will Geer was well known for his liberal views and activism. He supported workers’ rights and the unions, and his wife, Herta, grew up surrounded by politics; her grandmother was Ella Reeve Bloor, a founding member of the Social Democracy of America in 1897, which later became the Social Democratic Party. HUAC viewed this link as conclusive proof of Geer’s communist tendencies.

Hounded out of Hollywood: Topanga film festival and the legacy of Will Geer

Actor Will Geer poses next to the sign at the entrance to his Theatricum Botanicum in Topanga, in the Santa Monica mountains.

2

The family decided to travel to the hearings in New York together. “Mother said, ‘You’re not going to court alone.’ So they bought a trailer and drove across country,” says Ellen. “We turned it into a beautiful trip that none of us will ever forget. There were a lot of campfires, a lot of talking about life. When mother and Pop went to the hearings, Pop was wonderful. He said, ‘This is the biggest turkey I’ve ever been in’.”

Unlike some of his peers, Geer refused to testify. “He wasn’t a rat,” says Ellen. “Many of his friends were rats, and they did it to escape what was happening. But Papa always said, ‘You have to understand that when people are put in a situation like that, they don’t know how they’re going to react’.”

Back in Hollywood, acting work quickly dried up but it wasn’t just her parents who struggled; Ellen and her siblings also faced ostracism. “People can be very mean. It was a terrible scene for the kids. We were chased after, and called, ‘Red Diaper Babies’.”

Will Geer become disheartened, and while he worked on the land, which at that time had no running water or electricity, growing fruit and vegetables (their only income), his wife decided to leave, taking the children with her.

“It was the wild west here and I’m not joking. We had mountain lions, fires and floods, but it was beautiful,’ says Ellen, of the fledgling artists’ colony. “We went to school in bare feet, it wasn’t hippy, it was living with nature. Mum got us through it but when Pop collapsed she knew she had to take us away. He was 50, and he stopped as a man. He just stayed in the garden and we saw him lose his heart. It was so hard on him. Ultimately, it broke up my parents’ marriage.”

Eventually, Geer got a call from Broadway, and left Topanga to earn a living on the east coast. In the meantime, Herta and the children moved around all over the country. “We went to 14 different schools and lived in trailer parks.”

Like her parents Ellen decided to become an actor, but the tide only began to turn for the splintered family in 1972 when Will Geer got a call from the producer of the Waltons. One by one the family returned to Topanga, to live together once more, and the following year the Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum, a non-profit corporation, was founded. To this day, audiences noodle their way up the canyon to watch performances of Shakespeare in the open air.

Will Geer may have been wronged but he wasn’t a bitter man, and some of the old wounds healed. “Papa lost friends but got them back. Jimmy Stewart was very right wing but in the end he hired me in his one and only TV series under the auspices that I would never talk politics. After seven or eight episodes he also hired Pop, and it was beautiful to me to see them hug.”

After Geer’s death in 1978, the family decided to continue his work, and alongside the theatrical performances they now also run educational workshops for children. A statue of Will Geer sits in a shady memorial garden on the land, his ashes nearby. “And mother is buried under the sycamore tree,” says Ellen, who has also directed this season’s run of Measure for Measure.

Topanga may only be a 40-minute drive from the centre of Hollywood but it’s light years away in sensibility. There’s nothing flashy here. Just nature and the stars. “We’ve been hoping to work with the Theatricum to hold our event here for years now,” said Urs, who founded the four-day festival with his wife Sara. They’ve now partnered with John Fitzgerald, who co-founded Slamdance, and now runs CineCause, a philanthropic platform, connecting socially relevant films, and celebrities to related causes. “Seeing the Theatricum filled to the gills, buzzing with a sense of anticipation, surrounded by a sea of familiar and new faces, and being able to kick off with a film created by local filmmakers, has been a truly rewarding experience,” said Urs. “It really feels like the festival has found its place in this community.”

Will Geer would no doubt have appreciated the inclusive sentiments of this new wave of artists.

“What happened to him was very shocking,” says Ellen. “He was a true humanitarian. A people person.”

3

This Los Angeles Times article discusses a documentary film about the life and work of visual artist and longtime Topanga resident Chris Burden, best known for his iconic “Urban Light” sculpture at LACMA. The film, entitled simply “Burden”, was released April 2016.

Carolina A. MirandaLos Angeles Times, May 10, 2017

Every documentary has its challenges. Inadequate budgets. Complicated filming locations. Seemingly voluble sources who clam up the minute they get in front of a camera.

But when filmmakers Richard Dewey and Timothy Marrinan set out to make their debut feature documentary about the life and work of the Los Angeles artist Chris Burden, they didn’t know that they would also be contending with his death. In the final months of his life, Burden was quietly battling malignant melanoma, a struggle he lost in the spring of 2015, when he passed away at age 69.

“We had no idea that we’d be capturing the end of his life when we started the project,” Dewey says.

During his life, Burden was known for treacherous performances — in 1971, he had a marksman shoot him in the arm as a work of art — and for producing grand public sculptures, such as the street lamp installation, “Urban Light,” that greets visitors to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Dewey and Marrinan say that observing Burden produce some of his elaborate installations prepared them to complete their own labor of love. After more than half a dozen years of work, their documentary, “Burden,” opened last week in New York and debuts in Los Angeles Friday at the Nuart Theatre. (It is also available for streaming on iTunes and Amazon.)

“There was a ton to learn from Chris,” says Dewey.

“You have to have patience,” Marrinan says. “You have to let things develop. You have to work out the small details.”

“Burden” is a compact 90 minutes that tracks the artist from his years as a student at UC Irvine, where he was part of the university’s first crop of MFA students, through his most iconic — and iconoclastic — performances: “Trans-fixed,” from 1974, in which he had himself nailed to a Volkswagen Beetle in a position of crucifixion; the infamous “TV Hijack,” from 1972, in which he held a curator at knifepoint on a local television program; and, of course, “Shoot.”

The film opens with one of the art videos Burden paid to air on local television stations late at night in the ‘70s as a form of humorous self-promotion, and it closes with another work, one that provides the documentary with an emotional coda.

This consists of footage of the artist’s last completed sculpture: “Ode to Santos Dumont,” a small, fully functional dirigible that went on view at LACMA just five days after his death. The work was a floating, mechanical tribute to the Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, who flew a dirigible around the Eiffel Tower in 1901.

How the iconoclastic life and quiet death of L.A. artist Chris Burden was captured in a new documentary

Richard Dewey, left, and Timothy Marrinan, the directors of a new documentary about the late Los Angeles artist Chris Burden, stand amid his

sculpture “Urban Light” at LACMA.

4

“[That piece] incorporated a lot of things that Chris liked to think about: history, revising history, aviation and engineering,” Dewey says. “Here in the U.S., we say the Wright Brothers invented aviation. But Chris is saying, ‘Wait, there’s a Brazilian guy who had a role in aviation history.’ It shows that the art works on a lot of different levels.”

These sorts of myriad layers, present in so much of Burden’s work, are what inspired Dewey and Marrinan, longtime friends united by an interest in film, to make a documentary about the artist.

Marrinan, who hails from England, first stumbled into Burden’s art while at Harvard University, when he saw photos of early performances in a book. The images, he says, were “unforgettable.”

Dewey, who’s from Pennsylvania, became familiar with Burden after “Urban Light” was installed at LACMA in 2008. Reading a profile of the artist, he was surprised to learn that this beloved work of public sculpture had been made by an artist who’d had a key role in the avant-garde performance art scene of the ‘70s.

“You had a person who did these wild performances, but you also have this person who did these heartwarming civic sculptures,” he says. “And my question was, how did he get from A to B?”

They began to answer that question with a magazine article. (In addition to film, Dewey has a background in journalism.) In 2008, the pair, both living in Los Angeles, teamed to write a profile of Burden for the New York-based Whitewall magazine. (Since then, they have both relocated: Dewey to New York, Marrinan to London.)

During that interview, they learned that the artist was about to stage one of his “Beam Drop” pieces in Antwerp, Belgium. For those works — first executed in Lewiston, N.Y., in 1984 — Burden would drop steel I-beams from a crane into a pool of concrete. Once the concrete hardens, it freezes the beams in a random arrangement, like an action painting produced on an industrial, 3-D scale.

Intrigued, Marrinan and Dewey followed Burden to Antwerp to make a 10-minute short about “Beam Drop” in 2009.

“It was a very low-budget affair,” Marrinan says. “We drove over to Antwerp from London with a kit in the car and just started shooting with a friend of ours. We got to know Chris in that setting.”

That led to the idea of embarking on a full-scale documentary.

“I was interested in the total commitment to his art,” Dewey says. “Putting his body on the line, putting himself in these uncomfortable situations, and in the later years, doing these pieces that took years and years to come about. ‘Urban Light’ wasn’t a commission from LACMA; he just started buying [street lamps]. He had hundreds of them. And it ultimately coalesced into this piece that becomes an L.A. landmark.”

“What we wanted to do was show his art, then dig deeper,” Marrinan explains. “To show the context in which his art was made and the ideas that he was grappling with so that people could come to their own conclusions. People do have a very divergent range of opinions about Chris’ life and career.”

And they wanted to do it in a way that would

The documentary “Burden” examines some of Chris Burden’s most iconic works, including “Shoot,” from 1971, in which the artist had a friend shoot him in the arm.

5

speak to a general audience.

“There are a hundred different ways to tell Chris’ story,” Dewey says. “But we wanted to tell it in a way that was accessible to people who aren’t in the art world. We try to think in those respects.”

In 2010, the pair traveled to Burden’s Topanga Canyon compound and proposed the idea of a feature documentary. Burden agreed right away and provided the filmmakers with access to his personal archives — which included photographs, video and audio.

“Some of his archives were cassette tapes and reel-to-reel tapes, and we had some of it digitized

for the first time,” says Marrinan. “Some of it, I don’t think has been seen.”

The filmmakers also spent a good deal of time interviewing collaborators, friends, colleagues and experts.

“We wanted to get the vivid firsthand testimony of what it was like to be there,” Marrinan says.

And do they ever. This includes interviews with Burden’s first wife Barbara Burden, who assisted in many of the early performances, as well as Bruce Dunlap, the artist and marksman who famously shot Burden in the arm.

“The performances exist in two realms,” Marrinan says. “There’s the experience of looking at the documentation and then there’s the experience of what it was like to be in the room and pull the trigger.”

Also on the lineup is Phyllis Lutjeans, the curator who survived the episode at knifepoint on cable TV.

“I was really terrified,” Lutjeans recalls in the film. “’What went through my mind was, “Has he lost it?” ... But I knew then and I know now that he was going to shift art history.”

Dewey and Marrinan say that part of their task was to get beyond Burden’s sensational public persona to show the profound thinking that went into some of his work. The artist thought deeply about the nature of objects and art — and how the boundaries of each might be prodded and poked and, perhaps, blown to smithereens.

Seeded throughout the film are scenes from an interview that Regis Philbin conducted with Burden in the mid-1970s.

“I think you get the sense at the start of that interview that Regis is, like, ‘Oh, here is this crazy guy,’” says Marrinan. “But Chris answers the questions really genuinely — and by the end I think he turns [Philbin] around. He is genuine about what he is doing. It’s not just for shock value.”

“He had an eclectic set of interests, and a lot of his art is a combination of pulling from those disparate interests,” says Dewey. “That was interesting to see — how wide-ranging his knowledge was, from aviation to trains in the transportation space to the history of civic art in Rome and Paris. And he was really willing to go with his instincts and let things develop over a lot of time.”

The documentary captures difficult moments too. In continuously trying to outdo himself on the performance front, the artist could often alienate those who were close to him.

“Burden” filmmakers Timothy Marrinan, left, and Richard Dewey, stand next to Chris Burden’s “Metropolis II” at LACMA.

6

“Burden” covers his transition back to sculpture, which like his performance work, played with elements of force and aggression: the “Beam Drop” pieces, the impossible towers made out of Erector set parts and the 1987 installation devoted to chronicling all of the submarines employed in the U.S. Navy’s fleet (a wry take on the history of U.S. militarism).

During filming, Dewey and Marrinan happened upon the completion and installation of one of Burden’s more popular Los Angeles works: the frenetic “Metropolis II,” a three-dimensional cityscape clogged with highways and filled with speeding toy cars (currently on long-term view at LACMA).

Dewey says that he is grateful for what they were able to capture before Burden’s death.

After his passing, as the filmmakers worked to complete the film, “we had to dig deeper for archival materials.” Marrinan says.

“In some ways,” he adds, “an unexpected limitation like that can benefit a project. When we did get hold of some of the early footage of him, it was so great to see him talk about those projects at the time that they were happening. The ideas were so present to him.”

“People move in and out of your life,” Dewey says. “To have him move into your life at that period? It’s a remarkable experience.”

“You have an unusual relationship making a documentary with someone,” adds Marrinan. “You have this imposed distance, you are behind the camera. ... But when you’re not filming them, you’re talking about them, thinking about them, thinking about the structure, going over the interviews you’ve shot. You feel so close to your subject.

“The film, it’s the culmination of a whole process for us, and a really great experience. It’s a shame that Chris couldn’t see it.”

7

Flavia PotenzaTopanga Messenger, December 12, 2013

Bob Harris, owner of Malibu Ceramic Works Inc., likes to do what he likes to do.

Nowadays, that is keeping the lost art of handmade California tile of the early 20th century and its cultural richness alive and prospering.

In 1979, Harris worked in the film industry and knew nothing about tile. But when a friend moved out of Topanga, Harris bought his collection of Malibu Tile that was produced by Malibu Potteries from 1926-1932.

“I liked them and would give them away as Christmas presents,” says Harris.

Little did he know that 30 years later, he would be regarded as the founding father of Malibu Tile and other decorative art tiles of the early 20th century because he was able to recreate the formulas that had been lost to history.

The most comprehensive collection of Malibu Potteries, that once boasted more than 100 artists and craftsmen, can be found at the historical Adamson House in Malibu, once the home of Rhoda Rindge, of the famed Rindge Ranch, and her husband Frederick Adamson.

When the depression hit in 1929, the public’s interest in decorative art tile was waning. In 1932, Malibu Potteries burned down and went out of business, as did other companies.

In 1979, Harris thought it would be “interesting” to remake the tiles and called upon his friend, Topanga ceramist Jim Sullivan, whose tile art you walk on when you cross the threshold of the Topanga Library.

Together they started Malibu Ceramic Works in Harris’ garage. They started testing colors and making tiles and eventually created an entire production model, as well as the business model.

“It took two years,” Harris says. “There were no books, no internet. We had to figure it all out ourselves: the technology, the formulas and techniques to make glazes and restore the lost art of making Malibu tile. I financed it because I was still working in the film business.”

Little by little, they created a business.

“In the ‘70s, when there wasn’t much interest in decorative arts, we started restoring the use of brilliant colors at a time when the preferred colors were earth tones,” says Harris. “We learned that low-temperature firing is the method to get the brilliant reds and yellows and restored that tradition.”

They went through years of struggle, moving from the garage to a pottery studio behind the Legion Hall (now Froggy’s Fish Market). When it burned down in 1991, they moved to the Turnout (the Flying Pig) until 1992 when the mudslide took

Bob Harris’ Malibu Ceramic Works

Malibu Potteries tile and fountain Adamson House, Malibu, California

8

out the building, then back to Harris’ home when he took over and ran the business himself.

In 2002, he bought the property that had been Pamela Ingram’s Sassafrass Nursery—she died in 2000 and there was a family tussle over the inheritance. He set up shop with his son, Matthew, who runs the day-to-day operations, and expanded the business to do other tile designs of that era.

“Other companies can’t do production like we can. I’m very efficient in making it, developing new systems that other ceramic people don’t use. A lot of other companies have a lot of seconds. We don’t have seconds; we have overruns.

“We’re a full-service business and do all the things that Malibu Potteries did. They were a big company. We try to emulate what they did. They had good designs. We also do a lot of restoration on old buildings; people will ask us to match old tile. We’ve done big jobs and small.

One of the small jobs they did was for Patricia Colvig, who wanted to redo her kitchen in Malibu tile.

“I agreed to that job and tried to help Patty in every way because she loved the tiles so much and appreciates it. The tile is reasonable for what it takes to make it, but it was expensive for her.”

Colvig was more than happy with the job and her kitchen stands as testimony to the skill and artistry of Harris and the Malibu Ceramic Works production team.

“This has been a visionary project,” says Harris. “It takes something like that to do what no one has done for years. I’m good at that. I like to work as a team and like to delegate. If you work together everything gets better. I can figure things out and am good with color. It’s a talent I never knew I had.”

When he worked in films, he and his team were never out of work and even won an Oscar for Bird.

“The producers who hired us appreciated us,” he says. “They can pick whomever they want and they picked us. I like to do what I like to do. You do your job and you get more work.”

Malibu Ceramic Works has established itself as a local art treasure. Many of the Art Tile projects designed and manufactured by Malibu Ceramic Works adorn prominent commercial and residential structures such as: The Battistone Villa in Santa Barbara, the Four Seasons Biltmore Hotel in Santa Barbara and most recently, Malibu’s Legacy Park and the restored Malibu Lagoon. For more information: [email protected]; (310) 455-2485; malibuceramicworks.com; 275 N Topanga Canyon Blvd, Topanga, CA, by appointment only.

9

Carren JaoLos Angeles Times, June, 7, 2017

When experienced home builder and sometime illustrator Bill Buerge calls the restoration of the Mountain Mermaid his “ultimate challenge,” he isn’t kidding.

“Piles of exterminated bees, horse manure and goat poop littered the floors. Most of the plaster had fallen from the walls,” he recalls. That’s just on the inside of the 7,000-square-foot Spanish Colonial Revival-slash-Mission Revival structure nestled in Topanga Canyon.

Out in the five-acre garden, invasive plants ruled. Large eucalyptus trees were especially troublesome. Roots snaked beneath the property and up through the shower floor 50 feet away. Meanwhile, water runoff chipped away at the foundation, causing the whole structure to list.

It was enough to scare away a few buyers, but not Buerge. “I was hopelessly in love with this floundering water-logged Mermaid,” he says.

He compares the Mermaid’s appeal to a siren song. Irresistible.

Perhaps it was the Mermaid’s checkered past; previous incarnations include a country club, a dude ranch, a gay bar, a Jewish boys’ school, and even an upscale brothel and gambling joint run by gangster Mickey Cohen. Built in 1930, it was called the Mermaid Tavern at one point, and Buerge retained that name.

Perhaps it was the bucolic location that drew Buerge as well, as he doggedly pursued his siren and eventually moved into the property on New Year’s Day 1990.

Buerge immediately went about putting the Mermaid back together. With the help of semi-retired contractors and workmen, he built a new foundation and brought the structure up to code. His seemingly endless to-do list included: upgrading the Mermaid’s electrical, plumbing and heating systems; straightening and insulating the walls; rebuilding the fireplace; refinishing the antique floors; and replacing a leaking roof with mission tile.

Major reboot of Topanga house and gardens was a passion project, builder-owner says: ‘I was hopelessly in love...’

The dining room in the Mountain Mermaid in Topanga, a 7,000-square-foot home with expansive gardens.

The pool and exterior of the Mountain Mermaid; it took about three years just to make it habitable.

10

It took Buerge about three years to address the major issues and gain a certificate of occupancy from the Department of Building and Safety. He has been fine-tuning the property ever since. In the meantime, he also turned his attention to the Mermaid’s gardens.

At first, Buerge read books, joined gardening clubs and worked with landscape designers to rework the Mermaid’s gardens. Eventually, he gained enough confidence to undertake the garden design himself.

Today, the Mermaid is once again a place of beauty — not to mention the site of many photo shoots and events. The once desolate garden is now a serene retreat of meandering paths, cool shade and 15 flowing fountains. “Birds and bees abound. Snakes slither. Lizards patrol. Bunnies hop. Raccoons, possum, coyotes and bats come to life at night,” says Buerge, “It’s a magnet for wildlife.”

It has the paperwork to prove it too. The Mermaid’s lush garden is one of the National Wildlife Federation’s Certified Wildlife Habitats. It’s a designation that Buerge says came naturally. The garden already met the prerequisites for certification. It provides food, water, shelter and places for reproduction.

Buerge employs two men, Sergio Jimenez and Stevie Montes de Oca, to maintain the garden and the structure. The two prune, rake and repair throughout the property. Rather than use chemical pesticides, the gardeners pull weeds by hand and spray the leaves with soapy water, which can kill spiders and ants that harm the foliage.

Butterflies are the garden’s special guests. Monarchs, western tiger swallowtails, mourning cloaks and California sisters are just a few of the garden’s VIPs.

For them, Buerge and his two gardeners plant several kinds of milkweed, lantana and sedum, which are magnets for these winged creatures. California natives, succulents and grasses add to the garden’s verdant surroundings.

Butterflies even have special accommodations at the Mermaid. Once spotted in the gardens, a caterpillar egg is carefully transferred into a 100-square-foot mesh enclosure built by Jimenez, where it is protected from predators. Jimenez says there are plans to build an even larger 1,000-square-foot enclosure in the near future.

With the help of his daughter, Luna, Jimenez makes sure each butterfly has enough to eat and drink. When a giant swallowtail butterfly hatches, for example, the two set aside organic citrus fruits for them to feed on.

Buerge says special consideration is given to these winged creatures because of their dire straits. “They’re the most beautiful creatures in nature, but they are getting wiped out around the world.” For example, the monarch butterfly population has declined 90% in the last two decades.

Beth Pratt-Bergstrom, California director for the National Wildlife Federation and author of “When Mountain Lions Are Neighbors,” says places like Buerge’s gardens are important links for wildlife trying to make their way in the world.

“A garden and an edifice like this can quickly begin to look rough around the edges, malfunctions and deteriorates without constant attention,” she said. “But we are terribly passionate about the place and its resident wildlife, don’t mind the effort, and love what we do.

This afternoon’s Topanga Canyon Festival and concerts are made possible in part by a generous grant from

The Premium Series is cosponsored by Sally & Irwin Goldstein.

Special thanks to our host for this afternoon’s festival and concerts, Bill Buerge and Gayle MacDonald-Tune. Additional thanks to Ellen Geer, Executive Director, Will Geer Theatricum Botanicum for her generous support and assistance. And a special thanks to this Afternoon’s Showcase Performance artists, Nevenka and Members of Theatricum Botanicum. To

pan

ga C

an

yon

Fes

Tiva

l