Toougly,butIloveitsshape ... · perceivedasmorenaturalthanthesustainabilityslogan(Msustainability...

Transcript of Toougly,butIloveitsshape ... · perceivedasmorenaturalthanthesustainabilityslogan(Msustainability...

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Food Quality and Preference

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodqual

Too ugly, but I love its shape: Reducing food waste of suboptimal productswith authenticity (and sustainability) positioningRoxanne I. van Giesena,1,⁎, Ilona E. de Hoogeb,1a CentERdata, PO Box 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The NetherlandsbWageningen University, PO Box 8130, 6700 EW Wageningen, The Netherlands

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:Food wasteSuboptimal productsSustainabilityAuthenticityPricingMarketing strategies

A B S T R A C T

In the societal change towards a more sustainable future, reducing food waste is one of the mostly discussedtopics. One significant source of food waste is the reluctance of supply chains and consumers to sell, purchase, orconsume products that deviate from optimal products on the basis of only cosmetic specifications. Yet, it iscurrently unclear how consumers can be motivated to purchase such suboptimal products. The present researchsuggests that presenting suboptimal products with a sustainability positioning or with an authenticity posi-tioning can positively affect consumers’ purchase intentions and quality perceptions of suboptimal products.Two studies (total N=1804) presenting suboptimal products with a sustainability positioning, an authenticitypositioning, or no positioning under varying price levels reveal that especially authenticity positioning canincrease purchase intentions for and quality perceptions of suboptimal products independent of the prices ofsuboptimal products. A sustainability positioning appears to work best when combined with a moderate pricediscount. Moreover, the findings show that respondents have lower intentions to waste suboptimal foods when aclear positioning is provided compared to when this is not provided. Together, these findings provide a con-structive first step towards a more sustainable solution for the suboptimal product waste problem.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, the high amount of food waste has receivedincreasing attention. Food waste can be defined as “any food, and in-edible parts of food, removed from the food supply chain to be re-covered or disposed (including composted, crops ploughed in/notharvested, anaerobic digestion, bio-energy production, co-generation,incineration, disposal to sewer, landfill or discarded to sea)” (FUSIONS,2014, p. 6). About one-third to half of all food produced for humanconsumption is wasted along the food supply chain and in households(FAO, 2013; Parfitt, Marthel, & MacNaughton, 2010), amounting to astaggering millions of tons of food being wasted yearly (Brautigam,Jorissen, & Priefer, 2014; Buzby & Hyman, 2012; Buzby, Hyman,Stewart, & Wells, 2011). As the production of food requires extensiveuse of natural resources such as water, energy, and land (FAO, 2013;Godfray et al., 2010), and produces greenhouse gas emissions (Garnett,2011), food waste is highly inefficient.One significant source of food waste is the reluctance of consumers

to purchase or consume suboptimal products (Aschemann-Witzel, deHooge, Amani, Bech-Larsen, & Oostindjer, 2015; Buzby & Hyman,

2012; de Hooge et al., 2017; Loebnitz, Schuitema, & Grunert, 2015).Suboptimal foods, also called oddly-shaped foods (Loebnitz et al., 2015)or foods with aesthetic or cosmetic imperfections (Beretta, Stoessel,Baier, & Hellweg, 2013; North, Hargreaves, & McKendrick, 1997), areproducts that deviate from optimal products on the basis of (a) cosmeticspecifications (e.g. weight, shape, or size), (b) their date labelling (closeto or beyond the best-before date), or (c) their packaging (e.g., a tornwrapper, a dented can), without deviating on the intrinsic quality orsafety (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2015; de Hooge et al., 2017; White,Lin, Dahl, & Ritchie, 2016). The focus of the present research is oncosmetic sub-optimality of fruits and vegetables. > 50 million tons offruit and vegetables are discarded each year in the European EconomicArea, largely because these products do not meet retailers’ and con-sumers’ standards of how they should look (Porter, Reay, Bomberg, &Higgins, 2018). Retailers use high aesthetic standards for the fruits andvegetables they offer (de Hooge, van Dulm, & van Trijp, 2018; Loebnitzet al., 2015). One reason for this is that the storage and distribution offruits and vegetables with similar shapes and sizes is more efficient(Porter et al., 2018). Retailers also argue that consumers are not willingto purchase fruits and vegetables with cosmetic flaws (de Hooge et al.,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.02.020Received 28 June 2018; Received in revised form 28 February 2019; Accepted 28 February 2019

⁎ Corresponding author.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (R.I. van Giesen), [email protected] (I.E. de Hooge).

1 Both authors contributed equally to this work. Author order is determined by alphabetical order.

Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

Available online 06 March 20190950-3293/ © 2019 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

T

2018). Therefore, retailers typically sell suboptimal fruits and vege-tables with price discounts (e.g. Intermarché’s Inglorious foods in-itiative and Loblaws “Naturally imperfect” initiative2, see alsoAschemann-Witzel et al. (2017)). Finally, consumers are generally un-willing to purchase cosmetically suboptimal fruits and vegetables(Bratanova et al., 2015; de Hooge et al., 2017; Loebnitz & Grunert,2015; North et al., 1997).Multiple studies indeed support the idea that consumers tend to

avoid purchasing suboptimal products. For example, consumers per-ceive superficial packaging damages as a source of potential con-tamination, and therefore have lower intentions to purchase such pro-ducts (White et al., 2016). In supermarkets, non-perishable productssuch as pasta or cereals are often discarded because of “crushed,dented, or otherwise damaged packaging, and expired shelf dates”(Kantor, Lipton, Manchester, & Oliveira, 1997, p. 5). Together, suchconsumer responses to suboptimal products can maintain high retailerstandards.It is currently unclear how consumers can be motivated to purchase

suboptimal products. There is some evidence that consumers purchasesuboptimal products when they receive extreme price discounts (deHooge et al., 2017; Verghese, Lewis, Lockrey, & Williams, 2013), whensuboptimal products are advertised as being grown with low pesticideuse (Bunn, Feenstra, Lynch, & Sommer, 1990), or when the deviationfrom the cosmetic specifications is only moderate (compared to ex-treme) (Bratanova et al., 2015; Loebnitz & Grunert, 2015; Loebnitzet al., 2015). Yet, none of these options reflects a sustainable or fi-nancially viable solution for the supply chain (de Hooge et al., 2018).Our research aims to provide initial insight into how consumers

could be encouraged to purchase suboptimal products in a sustainableand financially viable way. Contrary to using price discounts to sellsuboptimal products, a more sustainable and financially viable strategymight be to position suboptimal products differently. We examinewhether a different positioning of suboptimal products is as effective asprice discounts or whether a combination of these strategies is moreeffective. Two studies, conducted in two different European countries,reveal that sustainability and authenticity positioning can increasepurchase intentions of suboptimal products. Moreover, by includingpricing strategies, the studies demonstrate that sustainability andespecially authenticity positioning can generate higher purchase in-tentions for suboptimal products compared to price discounts.Together, these findings provide a valuable step towards a more sus-tainable solution for the suboptimal product waste problem.

1.1. Pricing strategies

Pricing strategies are used to boost sales and to change consumers’purchase decisions (Chen, Monroe, & Lou, 1998) for, among others,suboptimal products (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2017). Consumersusually determine the value of products based on product character-istics and price (Ahmetoglu, Furnham, & Fagan, 2014). When seeingsimilarly priced optimal and suboptimal products together, consumerstend to purchase the most aesthetically appealing (optimal) product(Kyutoku, Hasegawa, Dan, & Kitazawa, 2018). A price discount forsuboptimal products can act as a motivator for consumers to purchasesuboptimal products (de Hooge et al., 2017). However, price discountscan simultaneously signal and confirm consumers’ perceptions that theproduct is of lesser quality, increasing the likelihood of the productbeing wasted at home (Tsiros & Heilman, 2005).Instead, Study 1 examines whether providing a product character-

istic cue in the form of a positioning message may positively affect

consumer quality perceptions of suboptimal products, and thereby re-duce the need for price discounts. If positioning messages indeed in-crease quality perceptions, it might be possible to combine these withother signals of a high quality, such as higher prices (Zeithaml, 1988).Therefore, Study 2 further investigates the effect of positioning togetherwith a price increase.

1.2. Sustainability positioning

Nowadays, multiple information channels such as governmentalcampaigns (e.g. the European Waste Framework Directive), NGO ac-tivities (e.g. the Waste Resource Action Program (WRAP) in the UK), orpublic activities on social media (e.g. Food sharing apps) provide con-sumers with information about sustainability issues. The general idea isthat increasing consumers’ awareness about sustainability motivatesconsumers to adjust their behavior accordingly (Abrahamse, Steg, Vlek,& Rothengatter, 2005; FAO, 2013). For instance, WRAP’s “Love Food,Hate Waste” awareness campaign effectively reduced food waste byemphasizing environmental impacts (Principato, 2018). In addition,previous research showed that providing information on the carbonfootprint of bread production increased consumers’ willingness to payfor lower-carbon-footprint bread (Del Giudice, La Barbera, Vecchio, &Verneau, 2016). Also, raising consumer awareness of food waste (e.g.with diary studies) increased consumers’ intentions to reduce theirhousehold food waste (Quested, Parry, Easteal, & Swannell, 2011).These findings imply that providing information on sustainability as-pects related to food waste of suboptimal products (e.g., “purchase thisproduct to avoid food waste”) may motivate consumers to act sustain-ably and to purchase suboptimal products. Sustainability positioning isin the present research defined as the positioning of suboptimal pro-ducts in a way that highlights their environmental sustainability.At the same time, there are some arguments against the potential

positive effect of sustainability positioning, as such positioning providesan external reason to purchase a suboptimal product. In the case ofsuboptimal products, consumers experience uncertainty about the in-trinsic quality aspects of the product (de Hooge et al., 2017; Loebnitzet al., 2015). Intrinsic quality aspects refer to the physical part of aproduct, such as taste, shape, or size; aspects that cannot be changedwithout altering the physical composition of the product (Olson, 1977;Zeithaml, 1988). Extrinsic quality aspects are product-related aspectsnot part of the physical composition of the product itself, such as ad-vertising, brand names, or price. Whenever there is informationasymmetry within a transaction, consumers tend to focus on one or twoextrinsic quality aspects to make their purchase decision (Connelly,Certo, Ireland, & Reutzel, 2011; Darby & Karni, 1973; Spence, 1973). Asustainability positioning may then function as an extrinsic quality cue,signaling that there are additional external reasons to purchase theproduct. Yet, the positioning will not address consumers’ low expecta-tions concerning the quality and taste of suboptimal products.Therefore, we expect that a sustainability positioning can increase

purchases for suboptimal products compared to not using positioningbecause it provides an additional reason for purchasing, however thispositioning would not increase consumers’ quality perceptions of sub-optimal products. As both sustainability positioning and price discountsare extrinsic quality cues, we expect that they are equally effective inincreasing sales. At the same time, when sustainability positioning andprice discounts are combined, it is expected that purchase intentionswill increase more than when only a price discount or a sustainabilitypositioning is provided.

1.3. Authenticity positioning

A positioning strategy that focuses on increasing quality perceptionsof suboptimal products might also be used. For example, suboptimalproducts may be perceived as more realistic or natural compared tooptimal products. This can be done by using a positioning that focuses

2 For more information, see: http://www.canadiangrocer.com/worth-reading/french-grocer-tackles-food-waste-with-ugly-fruit-pos-41007 andhttp://www.thestar.com/life/food_wine/2015/03/12/loblaws-sells-ugly-fruit-at-a-discount-to-curb-food-waste.html

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

250

on the authenticity of a product. Authenticity positioning of suboptimalproducts highlights the product’s genuineness, origin, or naturalness.Authenticity is a broad construct encompassing various dimensions. Forinstance, brand authenticity encompasses continuity, originality, re-liability, and naturalness (Bruhn, Schoenmüller, Schäfer, & Heinrich,2012). Authentic products are perceived as products with a more nat-ural, home-made, or handmade appearance, are often described asnostalgic, local, regional and/or traditional, and are perceived as pro-ducts for which more effort was needed to produce it (Hersleth, Næs,Rødbotten, Lind, & Monteleone, 2012; Kadirov, 2015). Following theproduct authenticity literature, we focus on the degree to which pro-ducts are perceived as real, sincere and genuine (Bendix, 1992;Beverland & Farrelly, 2010; Morhart, Malär, Guèvremont, Girardin, &Grohmann, 2015).Specifically relevant for the current type of foods studied (fruits and

vegetables) is the naturalness dimension of authenticity. This dimen-sion covers the perceived healthiness and freshness of a product, andrespect for the environment (Binninger, 2017; Margetts et al., 1997).Natural products are products based on grown plants, animals, or ma-terials collected from the environment, and with an absence of ad-ditives, pesticides, preservatives, chemicals, or processing in the finalproduct (Rozin, Fischler, & Shields-Argelès, 2012). Natural products areperceived as better, more genuine, more green and organic (Rozin et al.,2012). Therefore, emphasizing the abnormal shapes of suboptimalfoods could underline the product’s naturalness, and thus also its gen-uineness.Authenticity cues in regular (i.e., in manufactured, optimal) pro-

ducts have been shown to increase brand choice (Fritz, Schoenmueller,& Bruhn, 2017; Morhart et al., 2015), purchase intentions and will-ingness to pay (O’Connor, Carroll, & Kovács, 2017). Moreover, au-thenticity cues can increase perceptions of product quality and fresh-ness (Groves, 2001; Lu, Gursoy, & Lu, 2015; Moulard, Raggio, & Folse,2016). Authenticity positioning may thus function as an intrinsicquality cue, in the same way as a ‘Cues of organic’ label has been foundto act as a heuristic cue from which consumers infer higher productquality and additional health aspects (Vega-Zamora, Torres-Ruiz,Murgado-Armenteros, & Parras-Rosa, 2014). Therefore, we expect thatan authenticity positioning of suboptimal products (e.g. “naturallyimperfect”) will increase both purchase intentions and quality percep-tions compared to suboptimal products without positioning. Moreover,we expect that authenticity positioning will be equally effective in in-creasing sales as price discounts. At the same time, when authenticitypositioning and price discounts are combined, purchase intentions willincrease more than when only a price discount is provided.The present two studies examine the effects of sustainability and

authenticity positioning on purchase intentions, choice and qualityperceptions. In both studies, consumers were presented with optimaland suboptimal products (apples or carrots) of varying prices with anaccompanying sustainability or authenticity positioning (or no posi-tioning). Consumers then made a choice between the optimal andsuboptimal product, and indicated their quality perceptions and pur-chase intentions for the suboptimal product only. In both studies, weexpected sustainability positioning to only influence purchase inten-tions for suboptimal products, and authenticity positioning to influenceboth purchase intentions and quality perceptions. We tested the fol-lowing hypotheses:H1: Sustainability and authenticity positioning of suboptimal pro-

ducts increase purchase choice and intentions compared to no posi-tioning.H2: Authenticity positioning increases quality perceptions com-

pared to sustainability or no positioning.H3: The larger the price discount, the higher the purchase choice

and intentions for suboptimal products.H4: Positioning of suboptimal products combined with price dis-

counts increases purchase choice and intentions more than only a pricediscount.

Additionally, Study 2 tests whether the purchases for suboptimalproducts depend on consumers characteristics such as their commit-ment to environmental issues (Alcock, 2012), or organic buying beha-vior (Porter et al., 2018). Consumers who are environmentally com-mitted or who are used to buy organic products might view suboptimalproducts as more natural than consumers low on these characteristics(Loebnitz et al., 2015), and may therefore be more susceptible to sus-tainability or authenticity positioning.

2. Study 1: A first test of sustainability and authenticitypositioning

Study 1 tested whether a sustainability or authenticity positioningincreases purchase intentions for and quality perceptions of suboptimalproducts, and whether these effects would be comparable to the effectsof price discounts (H1-H4). The study included apples and carrots totest whether any effects would hold for two different types of products.

2.1. Method

2.1.1 Respondents and designFour hundred ninety-six visitors of the Milan Expo3 (250 males,

Mage= 31.41, SDage=13.40) participated during the summer of 2015in exchange for a gift voucher of €5 that they could spend at the Exposite. Respondents came from fifteen different European countries,northern Africa (2), the USA (6), or from Asia (11). They were ran-domly assigned to one of the conditions of a 3 (Positioning: sustain-ability vs. authenticity vs. control)× 3 (Price: discount vs. moderatediscount vs. same price)× 2 (Product: apple vs. carrot) between-sub-jects design. Purchase choice, purchase intentions, and quality per-ceptions of suboptimal products functioned as the dependent variables.

2.1.2 Procedure and variablesData collection took place in a quiet room located near the main

street of the Milan Expo. Respondents imagined doing their weeklygrocery shopping at their local supermarket and needed to buy, amongothers, apples or carrots. They imagined that they wandered throughthe aisles, and then encountered two shelves filled with apples (Applecondition) or carrots (Carrot condition), one filled with optimal (per-fect-looking) products and one with suboptimal products. The sub-optimal products only deviated in terms of appearance (oddly shaped),and prices were added to both suboptimal and optimal products. In allcases, the optimal apples cost €2 per kilogram and the optimal carrots€1.50 per kilogram, approximately in line with the regular prices forapples and carrots in Italy and the Netherlands at that time. In the sameprice condition, the suboptimal products were priced exactly the sameas the optimal products. In the discount condition, the price for thesuboptimal products was 30% lower compared to the optimal products(€1.40 for apples and €1.05 for carrots). In the moderate discountcondition, these prices were 15% lower (€1.70 for apples and €1.25 forcarrots).To manipulate positioning, the suboptimal products in the sustain-

ability condition were accompanied by the slogan “Embrace im-perfection: Join the fight against food waste!”. The focus of Study 1 wason the naturalness dimension of authenticity, so in the authenticitycondition, the slogan “Naturally imperfect: Apples the way they actu-ally look!” was added (see Appendix A). In the control condition re-spondents saw the products without any text. A pre-test (N=53)showed that the sustainability slogan was perceived as more sustainablethan the authenticity slogan (Msustainability slogan=6.0, Mauthenticity

slogan=5.12, F (1, 52)= 1.76, p= .002). The authenticity slogan was

3 The 2015 Expo was a universal exposition hosted by Milan (Italy) with thetheme “Feeding the planet, energy for life”, encompassing technology, in-novation, culture, traditions and creativity and how they relate to food and diet.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

251

perceived as more natural than the sustainability slogan (Msustainability

slogan=5.87, Mauthenticity slogan=5.08, F (1, 52)= 5.18, p= .027), andthere were no differences in how traditional the slogans were perceived(Mauthenticity slogan=3.74, Msustainability slogan=3.85, F (1, 52)= 0.55,p= .816).To measure Purchase choice respondents clicked on the product

(optimal or suboptimal) that they would buy. Next, respondents in-dicated how likely they were to buy the suboptimal product (Purchaseintention, 1, not at all likely, to 9, very likely) and they provided qualityperceptions for the suboptimal products (poor vs. good taste, flavorlessvs. flavorful, not at all delicious vs. very delicious, very poor vs. verygood quality, 9-point scales). A Factor analysis showed a clear one-factor solution (Quality perceptions, Eigenvalue= 3.37, R2= 84%,α=0.94, See Appendix B). Finally, respondents answered backgroundand demographic questions (gender, age, income, nationality, livingregion, educational level, profession).

2.2. Results and Discussion

2.2.1 Purchase choicesAnalyses of the data for the apples and carrots separately revealed

no differences between products (all Fs < 1.21, all ps > 0.27), hencewe analyzed the data for both products as one dataset. A chi-squareanalysis with positioning as the independent variable and purchasechoice of suboptimal products as the dependent variable showed asignificant association between positioning and purchase choice, sup-porting H1 (χ2 (2, N=496)=29.25, p < .001). Overall, for the sus-tainability positioning (54%) and the authenticity positioning (46%)suboptimal products were selected more often than for the controlcondition (26%, χ2 (1, N=327)=13.61, p < .001, and χ2 (1,N=338)=28.35, p < .001, respectively, see Table 1). The sustain-ability and authenticity positioning conditions did not differ in pur-chase choice (χ2 (1, N=327)=2.57, p= .11).Under all price conditions, (marginally) significant associations

were found between positioning and purchase choices (all χ2s(2) > 5.43, ps < 0.06), see Fig. 1. In line with H4, under all priceconditions more respondents preferred the suboptimal products whenthey were exposed to a sustainability positioning (discount: 53%;moderate discount: 64%; same price: 47%) vs. no positioning (discount:33%; moderate discount: 29%; same price: 16%; all χ2s (1) > 4.53,ps < 0.03). Further, more respondents who were exposed to authen-ticity positioning (vs. control) preferred the suboptimal products whenreceiving a high (30%) discount (51% of the respondents vs. 33% of therespondents in the control condition) or when receiving no discount(47% of the respondents vs. 16% in the control condition), (χ2 (1,N=110)= 3.74, p= .05, and χ2 (1, N=107)= 12.02, p= .001, re-spectively). Unexpectedly, however, authenticity positioning did notaffect purchase choice when respondents received a moderate discount(39% of the respondents, vs. 29% in the control condition, χ2 (1,N=110)= 1.03, p= .31).Most importantly, without any discount, more respondents pre-

ferred the suboptimal products when they were exposed to sustain-ability positioning (47%) or authenticity positioning (47%) comparedto when no positioning was provided without any discount (16%), witha moderate (29%), or with a high discount (33%) (all χ2s (1) > 4.56,ps < 0.04). This shows that a sustainability or authenticity positioning(without any price discount) can increase purchase choices of sub-optimal products more than price discounts (without any positioning).

2.2.2 Purchase intentionsA two-way ANOVA with positioning and price as independent

variables and purchase intention for suboptimal products as the de-pendent variable showed a main effect of positioning, supporting H1 (F(2, 487)= 11.96, p < .001, η2=0.05). Not in line with hypotheses H3and H4, there was no main effect of price, (F (2, 487)= 0.70, p= .50)and no interaction between positioning and price, (F (4, 487)= 1.84,p= .12). Follow-up contrast analyses showed that a sustainability po-sitioning (M=5.64, SD=2.50) or an authenticity positioning(M=5.58, SD=2.44) increased purchase intentions compared to theControl condition (t(493)= 4.33, p < .001; t(493)= 4.03, p < .001,respectively). There were no differences between the sustainability andauthenticity positioning (t(493)= 0.23, p= .82). When controlling forsocio-demographics, by adding these as covariates, the outcomes ofthese analyses remained similar. There were also no effects of demo-graphics on purchase intentions for suboptimal foods, except for age(Fage= 22.17, p < .001; all other Fs < 0.061, all ps > 0.92). Olderpeople generally showed lower purchase intentions for suboptimalproducts (b=-0.32). Thus, the findings suggest that sustainability andauthenticity positioning can increase purchase intentions for sub-optimal products compared to when no positioning is provided, in-dependent of the price of the suboptimal product and of the re-spondents’ demographics.

2.2.3 Quality perceptionsA two-way ANOVA with positioning and price as independent

variables and quality perceptions as the dependent variable revealed amain effect of positioning (F (2, 487)= 8.78, p < .001, η2=0.04), butno main effect of price (F (2, 487)= 0.23, p= .80). Partially in linewith H2, follow-up contrast analyses revealed that sustainability posi-tioning (M=5.85, SD=2.02) and authenticity positioning (M=5.67,SD=1.93) both increased quality perceptions of the suboptimal pro-ducts compared to the Control condition (M=4.98, SD=2.13, t(493)= 3.94, p < .001; t(493)= 3.09, p < .01). There was no dif-ference between the two positioning strategies (t(493)= 0.78, p= .43).Moreover, an interaction between positioning and price was found

(F (2, 487)= 3.15, p= .01, η2= 0.03): both sustainability and au-thenticity positioning increased quality perceptions of suboptimalproducts, but this effect depended on the price of the suboptimal pro-ducts. Contrast analyses showed that in the discount condition, onlyauthenticity positioning marginally significantly increased quality

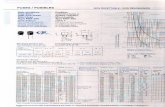

Table 1Purchase choice, purchase intentions, and quality perceptions means (and SDs)for suboptimal products as a function of positioning and price in Study 1.

Positioning condition

Dependent variable Control Sustainability AuthenticityPrice condition

Purchase choice % % %Price discount (30%) 33 %a 53 %c 51 %c

Moderate price discount (15%) 29 %a 64 %c 39 %a

Same price 16 %b 47 %c 47 %c

Total 26 %a 54 %b 46 %b

Purchase intention M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)Price discount (30%) 4.38 (2.61)a 5.05 (2.63)a 5.71 (2.27)b,c

Moderate price discount (15%) 4.64 (2.53)a 6.25 (2.06)b 5.19 (2.44)a,c

Same price 4.36 (2.55)a 5.63 (2.65)b 5.82 (2.60)b

Total 4.46 (2.55)a 5.64 (2.50)b 5.58 (2.44)b

Quality perceptions M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)Price discount (30%) 5.09 (2.08)a,c 5.55 (2.11)a 5.82 (1.74)d

Moderate price discount (15%) 4.82 (2.12)b,c 6.39 (1.77)d 5.11 (2.06)a

Same price 5.04 (2.22)a,c 5.63 (2.10)a 6.09 (1.89)d

Total 4.98 (2.13)a 5.85 (2.02)b 5.67 (1.93)b

Note. Purchase choice reflects the percentage of respondents who chose thesuboptimal product above the optimal product. Purchase intentions means (andstandard deviations) reflected respondents’ preference for the suboptimal pro-duct (not at all likely (1) – very likely (9)). There are no significant differencesbetween means with the same superscript, with χ2s and ts < 1.29, p > .20.Means with different superscripts differ significantly with χ2s > 5.19, ps <0.02 and ts > 2.14, ps < 0.04.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

252

perceptions compared to the control condition (t(4 8 7)= 1.92,p= .06). Unexpectedly, when prices were moderately lower, onlysustainability positioning increased quality perceptions compared tothe authenticity condition (t(4 8 7)= 3.28, p= .001) and compared tothe control condition (t(4 8 7)= 4.11, p < .001). Finally, when priceswere similar, only authenticity positioning increased quality percep-tions compared to the control condition (t(4 8 7)= 2.70, p < .01). Thissuggests that authenticity positioning indeed yields higher qualityperceptions, and that a discount is not necessary (and may even di-minish the effects of positioning on quality perceptions).

2.2.4 DiscussionStudy 1 provides first evidence for positive effects of presenting

suboptimal products with a positioning message. Overall, it appearsthat both sustainability and authenticity positioning can motivateconsumers to purchase suboptimal products, and that these effects mayoccur independent of the prices of suboptimal products. Moreover, re-spondents exposed to authenticity positioning reported higher qualityperceptions than respondents exposed to sustainability positioning. Inaddition, three unexpected findings were obtained from Study 1: First,there was no main effect of price discounts. This could be due to thespecific sample of Study 1. Milan Expo visitors are relatively caringabout the environment, as indicated by their high pro-environmentalself-identity (M=5.60, 7-point scale), and they might therefore be lesssensitive to price discounts. Second, authenticity positioning did notincrease purchases of suboptimal products when consumers received amoderate price discount, and third, not authenticity but sustainabilitypositioning increased quality perceptions of suboptimal products whenconsumers received a moderate price discount. To test whether thesefindings can be generalized beyond the specific messages and re-spondent sample used in Study 1, Study 2 was conducted.

3. Study 2: Further evidence for sustainability and authenticitypositioning strategies

Study 2 had multiple aims. First, Study 2 tested whether the findingsof Study 1 could be generalized beyond the specific sustainability andauthenticity messages used in Study 1. Specifically, Study 2 used newmessages, of which the authenticity message focused on the genuinedimension of authenticity. Second, Study 2 aimed to replicate thefindings with a representative Dutch sample. Third, Study 2 aimed tofurther investigate the combination of positioning and pricing, by adding acondition where suboptimal products were priced moderately higherthan optimal products. Furthermore, we tested for the potential

moderating effect of commitment to environmental sustainability (Alcock,2012), and organic buying behavior as a measure for prior exposure tosuboptimal products. Finally, thus far we studied the influences of po-sitioning on purchase intentions of suboptimal products to reduce wasteof suboptimal products. Yet, consumers’ purchase decisions in super-markets are influenced by different factors than consumers’ consump-tion decisions at home (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2015; de Hooge et al.,2017). Therefore, the effect of positioning strategies on purchase de-cisions does not necessarily translate to food consumption (and therebyfood waste) at home. To examine whether products are more or lesslikely to be wasted at home and the influence of positioning thereof,Study 2 also measured likelihood to waste suboptimal products.

3.1. Method

3.1.1 Respondents and design1308 Dutch inhabitants (50.2% female, Mage= 53.46,

SDage= 16.94) participated in a study on food choices in exchange for amonetary reward. Data collection took place via an online survey in anationally representative consumer panel, managed by CentERdata(CentERpanel).4 Respondents were randomly assigned to one of theconditions of a 3 (Positioning: Sustainability vs. authenticity vs. con-trol)× 4 (Price: Discount vs. moderate discount vs. same price vs. priceincrease)× 2 (Product: Apple vs. carrot) between-subjects design withpurchase choice, purchase intention, quality perceptions, and wastelikelihood as the dependent variables.

3.1.2 Procedure and variablesThe procedure was similar to Study 1. To manipulate positioning,

the sustainability slogan read “Apples (carrots) with special shapes:Don’t let them be wasted!”, and the authenticity slogan – focusing onthe genuine dimension, as induced by the first part of the slogan – read“Directly from the tree: apples with natural shapes! (Directly from thefield: carrots with natural shapes!)”. A pre-test (N=1059) showed thatthe sustainability positioning was perceived as more sustainable thanthe authenticity positioning and the control condition without posi-tioning (Msustainability slogan=5.67, Mauthenticity slogan=5.40, Mno

slogan=5.24, F (2, 1057)= 8.75, p < .001). The authenticity posi-tioning was perceived as more authentic than the sustainability posi-tioning and the control condition without positioning (Mauthenticity

slogan=5.06, Msustainability slogan=4.77, Mno slogan=4.63, F (2,

Fig. 1.

4 See https://www.centerdata.nl/en/projects-by-centerdata/the-center-panel

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

253

1058)= 6.39, p= .002). There were no differences in naturalness be-tween the sustainability and authenticity positioning, but the productsin both conditions were perceived as more natural than the products inthe control condition (Msustainability slogan=5.44, Mauthenticity slogan=5.49,Mno slogan=5.13, F (2, 1058)= 4.52, p= .011).5 Price conditions werethe same as in Study 1, except that a price increase condition was addedin which prices for suboptimal products were 15% higher compared tothe optimal products (€2.30 for apples and €1.95 for carrots).

Purchase choice and purchase intention were measured in the sameway as in Study 1, except that purchase intention was now measured ona 7-point scale. Quality perceptions were measured with the items taste,healthiness, safety, quality, and receiving value for money (all rangingfrom 1 to 7) (Quality perceptions, Eigenvalue= 3.62, R2= 73%,α=0.90, see Appendix B). To measure waste likelihood, the re-spondents indicated the likelihood that they would waste at least part ofthe suboptimal products after having purchased the product (rangingfrom 1, not at all likely, to 7, very likely).The respondents then answered a shortened three-item version of

the Commitment to Environmental Sustainability Scale (Alcock, 2012),which measures personal commitment to environmental sustainabilityby putting sustainability in the context of personal costs and forgoingother things in life (1= completely disagree, 7= completely agree) (deHooge et al., 2017) (Eigenvalue= 2.01, R2= 67%, α=0.75). Tomeasure organic buying behavior, respondents indicated how often theybought fruits or vegetables from the local farmer and how often theybought biologically grown fruits or vegetables (1= never, 5= always,Pearson’s R=0.38, p < .001). These items largely overlap with theitems “How often do you eat locally grown foods?” and “When inseason, how often do you shop at farmer’s markets?” from the GreenEating Behavior scale (see Weller et al., 2014). Finally, the respondentsindicated how often they engaged in grocery shopping and cooking fortheir households (both items 1= never, 5= always, averaged into oneshopping/cooking variable, Pearson’s R=0.70, p < .001) (de Hoogeet al., 2017), and completed several questions regarding their demo-graphics.

3.2. Results and Discussion

3.2.1 Purchase choicesAnalyses of the data for the apples and carrots separately revealed

no differences between products (all Fs < 1.06, all ps > 0.30), hencewe analyzed the data for both products as one dataset. A chi-squareanalysis with positioning as the independent variable and purchasechoice of suboptimal products as the dependent variable showed asignificant association between positioning and purchase choice, sup-porting H1 (χ2 (2, N=1308)= 33.57, p < .001; see Table 2 andFig. 2). Overall, suboptimal products were selected more frequentlywhen presented with the sustainability positioning (36%) than with nopositioning (29%), χ2 (1, N=846)= 4.73, p= .03). Also, suboptimalproducts were selected more frequently when presented with the au-thenticity positioning (47%) than with the sustainability positioning(χ2 (1, N=881)=12.15, p < .01), or with no positioning (χ2 (1,N=889)=32.42, p < .001).Separate chi-square analyses showed significant associations be-

tween positioning and purchase choices under all price conditions,partially in line with H4 (all χ2s (2) > 7.92, ps < 0.02). Contrary toStudy 1, only when respondents received a moderate discount, sub-optimal products were more frequently selected when presented with asustainability positioning (58%) than with no positioning (38%, χ2 (1,N=218)=8.01, p < .01). Under the price discount or similar priceconditions, suboptimal products were selected more frequently when

presented with the authenticity positioning (discount: 64%; moderatediscount: 51%; same price: 51%) than with no positioning (discount:45%; moderate discount: 38%; same price: 19%; all χ2s (1) > 6.88,ps < 0.01; χ2 (1, N=213)=3.16, p= .07 for moderate discountcondition). When prices were similar or higher, suboptimal productswere selected more frequently when presented with the authenticitypositioning than with the sustainability positioning (both χ2s(1) > 9.93, ps < 0.01).Finally, suboptimal products were selected more frequently when

presented with the authenticity positioning without any discount (47%)than with a moderate discount in the control condition (38%; χ2

(1)= 8.28, p < .01), and these choices did not differ from a 30%discount in the control condition (45%; χ2 (1)= 1.79, p= .22). Thisshows that authenticity positioning (without any price discount) canincrease purchase choices of suboptimal products at least as much asprice discounts.

3.2.2 Purchase intentionsA two-way ANOVA with positioning and price as independent

variables and with purchase intentions for suboptimal products as thedependent variable showed a main effect of positioning, supporting H1(F (2, 1296)= 16.70, p < .001, η2=0.03). Follow-up contrast ana-lyses showed that there was a marginally significant effect of sustain-ability positioning on purchase intentions (M=3.50, SD=1.73)compared to the control condition (M=3.27, SD=1.77, t(1305)= 1.89, p= .06). Authenticity positioning increased purchaseintentions (M=3.91, SD=1.79) compared to both the control condi-tion (t(1305)= 5.40, p < .001), and to sustainability positioning (t(1305)= 3.45, p= .001).Supporting H3, there was also a main effect of price (F (3,

Table 2Purchase decision, purchase intentions, quality perceptions, and waste like-lihood (and SDs) for suboptimal products as a function of positioning and pricein Study 2.

Positioning condition

Dependent variable Control Sustainability AuthenticityPrice condition

Purchase choice % % %Price discount (30%) 45 %a 53 %a 64 %e

Moderate price discount (15%) 38 %a 58 %d,e 51 %d

Same price 19 %b 23 %b 51 %d

Price increase (15%) 12 %b,c 10 %c 26 %b

Total 29 %a 36 %b 47 %c

Purchase intention M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)Price discount (30%) 3.81 (1.89)a,d 3.91 (1.74)a,d 4.50 (1.68)e

Moderate price discount (15%) 3.54 (1.81)a,c 4.16 (1.71)d,e 3.85 (1.90)a,d

Same price 3.01 (1.50)b,c 3.24 (1.65)c 4.05 (1.67)d

Price increase (15%) 2.71 (1.64)b 2.70 (1.43)b 3.28 (1.70)c

Total 3.27 (1.77)a 3.50 (1.73)b 3.91 (1.79)c

Quality perceptions M (SD) M (SD) M (SD)Price discount (30%) 4.70 (0.92)a 4.65 (1.04)a 5.13 (1.05)b

Moderate price discount (15%) 4.59 (1.22)a 5.02 (1.04)b 5.00 (1.06)b,c

Same price 4.55 (1.03)a 4.51 (1.16)a 5.24 (0.84)b

Price increase (15%) 4.78 (1.01)a,c 4.74 (0.87)a 5.08 (1.00)b

Total 4.66 (1.05)a 4.73 (1.05)a 5.11 (0.99)b

Note. Purchase choice reflects the percentage of respondents who chose thesuboptimal product above the optimal product. Purchase intentions means (andstandard deviations) reflected respondents’ preference for the suboptimal pro-duct (not at all likely (1) – very likely (7)). There are no significant differencesbetween means with the same superscript, with χ2s and ts < 1.07, p > .27.Means with different superscripts differ significantly with χ2s > 5.19, ps <0.02 and ts > 1.94, ps < 0.05.

5 We did not expect that the sustainability and authenticity messages woulddiffer on naturalness as both slogans emphasize that the shape explicitly differsfrom optimal foods.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

254

1296)= 30.86, p < .001, η2= 0.09). Higher prices for suboptimalproducts decreased purchase intentions: contrast analyses showed thatevery time the prices went up with 15%, purchase intentions decreased(M=4.10, SD=1.79 for discount condition, M=3.85, SD=1.82 formoderate discount, M=3.44, SD=1.67 for similar prices, andM=2.92, SD=1.62 for price increase; all ts (1304) > 2.96, allps < 0.01, except for a marginal difference between a 30% and a 15%discount, t (1304)= 1.87, p= .06).Moreover, there was an interaction between positioning and price,

partially in line with H4 (F (6, 1296)= 2.49, p= .02, η2=0.01).Contrast analyses showed that when prices were moderately lower,only sustainability positioning increased purchase intentions comparedto the control condition (t(1296)= 2.67, p < .01; t (1296)= 1.32,p= .19 for authenticity compared to control). When prices of thesuboptimal products were 30% lower, similar to, or 15% higher, onlyauthenticity positioning increased purchase intentions compared to thecontrol condition (ts(1296) > 2.56, ps < 0.02) and compared to thesustainability condition (ts(1296) > 2.58, ps < 0.02; ts < 1 for sus-tainability compared to control).To test whether commitment to environmental sustainability or

organic buying behavior would predict respondents’ purchase inten-tions for suboptimal products, we conducted a linear regression analysison purchase intentions of suboptimal products with positioning, price,commitment to environmental sustainability, organic buying behavior,and demographics as independent variables. This analysis showed noeffect of any of the demographics (all βs < 0.21, all ps > 0.13; seeTable 3). There were positive effects of commitment to environmentalsustainability and of organic buying behavior on purchase intentions inaddition to the positioning and pricing strategies: a higher commitmentand higher organic buying behavior increased purchase intentions.Adding interaction terms between the positioning strategies and or-ganic buying behavior or between the strategies and commitment asindependent variables in the regression did not result in significantinteraction effects (all βs < 0.06, all ps > 0.60), showing that theeffects of positioning did not depend on these consumer characteristics.

3.2.3 Quality perceptionsWe expected that especially authenticity positioning would affect

quality perceptions of suboptimal products. Replicating Study 1, a two-way ANOVA with positioning and price as independent variables andwith quality perceptions as the dependent variable showed a main ef-fect of positioning (F (2, 1296)= 24.94, p < .001, η2=0.04), but nomain effect of price (F (2, 1296)= 0.71, p= .54). Contrast analysisshowed that an authenticity positioning increased the quality percep-tions (M=5.11, SD=0.99) compared to the control condition(M=4.66, SD=1.05, t(1299)= 6.56, p < .001), and compared to

the sustainability positioning, supporting H2 (M=4.73, SD=1.05, t(1299)= 5.45, p < .001). There was no difference between the sus-tainability positioning and the control condition (t(1299)= 1.05,p= .29).There was an interaction between positioning and price (F (2,

1296)= 3.01, p < .01, η2=0.01). Contrast analysis revealed thatauthenticity positioning increased quality perceptions compared toboth the control and sustainability conditions under almost all priceconditions (authenticity vs. control: ts(1296) > 2.56, ps < 0.02) (au-thenticity vs. sustainability: ts(1296) > 2.58, ps < 0.02; t < 1 in themoderate discount condition). Replicating the unexpected finding ofStudy 1, sustainability positioning only increased quality perceptionscompared to the control condition when prices were 15% lower (t(1296)= 3.05, p < .01; ts < 1 for the other price conditions).

3.2.4 Waste likelihoodTo test whether the positioning strategies would influence

Fig. 2.

Table 3Linear regression analysis for purchase intentions of suboptimal products inStudy 2.

Purchase intention suboptimal products

Variable B SE B βSustainability Positioning (1

Sustainability condition, 0 other)0.23 0.12 0.06*

Authenticity Positioning (1Authenticity condition, 0 other)

0.62 0.11 0.17**

Price Discount (1 30% discount, 0other)

0.63 0.13 0.15**

Moderate Price Discount (1 15%discount, 0 other)

0.47 0.13 0.11**

Price Increase (1 15% increase, 0other)

−0.52 0.13 -0.13**

Gender (0 male, 1 female) 0.10 0.11 0.03Age (16–93 y.o.) < 0.01 < 0.01 < 0.01Number of household members (1–7) −0.04 0.05 -0.03Urbanity living region < 0.01 0.04 < 0.01Education 0.02 0.04 0.02Household income −0.03 0.02 -0.04Do shopping/cooking 0.03 0.05 0.02

Commitment to environmentalsustainability

0.20 0.05 0.12**

Organic buying behavior 0.25 0.05 0.14**

R2 14%F 14.47**

Mean purchase intention (SD) 3.57 (1.78)

Note. Significant relationships are indicated in bold. *p < .05. ** p < .01.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

255

household wastage of suboptimal products, we ran a two-way ANOVAwith positioning and price as the independent variables and wastelikelihood as the dependent variable. The results showed a main effectof positioning (F (2, 1296)= 3.45, p= .03, η2=0.01), no effect ofprice (F (2, 1296)= 1.35, p= .26), nor an interaction (F (6,1296)= 0.87, p= .52). Contrast analysis showed that a sustainabilitypositioning (M=2.23, SD=1.43) or an authenticity positioning(M=1.98, SD=1.30) did not increase wastage of suboptimal productscompared to the control condition (M=2.09, SD=1.38; t(1299)= 1.51, p= .13 and t(1299)= 1.13, p= .26, respectively). Theauthenticity positioning did decrease intentions to waste suboptimalproducts compared to the sustainability positioning, t(1299)= 2.66,p < .01).

3.2.5 DiscussionStudy 2 provides further support for the idea of presenting sub-

optimal products with a marketing positioning. Replicating Study 1with different slogans and with a representative Dutch sample, Study 2shows that a sustainability positioning can increase preferences forsuboptimal products. Yet, these effects appear to depend on the pricesof suboptimal products. On the contrary, an authenticity positioningseems to have a positive effect on purchase intentions for suboptimalproducts, and can increase purchase choices at least as much as pricediscounts. Moreover, authenticity positioning has a positive effect onquality perceptions of suboptimal products compared to sustainabilitypositioning or no positioning, and does not seem to increase wastage ofsuboptimal products in consumer households.

4. General Discussion

The belief that consumers do not purchase suboptimal productsmakes supply chain actors sell suboptimal products with a price dis-count or avoid selling suboptimal products altogether (de Hooge et al.,2018; Stuart, 2009). The consequences are unsustainable: lowering thevalue of food paves the way for more household food waste (Tsiros &Heilman, 2005), and not selling suboptimal products increases foodwaste across the supply chain (Beretta et al., 2013; Buzby et al., 2011).In a search for more sustainable solutions, the current research exploredwhether consumer acceptance of suboptimal products could be in-creased with marketing strategies. Two studies in two European coun-tries revealed that sustainability and especially authenticity positioningcan increase purchase intentions for suboptimal products. Moreover, anauthenticity positioning can increase quality perceptions of suboptimalproducts, and can increase purchase intentions at least as much as pricediscounts. Together, these findings show that marketing strategies canprovide a sustainable solution that stimulates the acceptance of sub-optimal products.

4.1. Theoretical implications

The present findings demonstrate that a sustainability positioningcan increase consumer choices for suboptimal products. Some priorevidence suggested that providing consumers with information on thefood waste issue can influence their behavior (Del Giudice et al., 2016;Quested et al., 2011). Our findings extend this line of reasoning anddemonstrate that sustainability cues can influence consumer choicesalso for suboptimal products.Similarly, we expand the authenticity literature by revealing that an

authenticity positioning can also be effective for suboptimal products.Previous studies have shown that authenticity positioning can affectconsumer responses to brands and to optimal products (e.g., Beverland& Farrelly, 2010; Fritz et al., 2017). Our findings demonstrate thatpositioning suboptimal products as genuine or natural can motivateconsumers to purchase these products. Moreover, it appears that au-thenticity positioning can counteract the doubts that consumers haveabout the intrinsic quality of suboptimal products. This is especially

surprising when considering that an authenticity positioning empha-sizes the “error” of suboptimal products: focusing attention on visibleweaknesses of products in a positive way can apparently generate po-sitive consumer responses.Our studies are among the first to compare the effects of multiple

marketing strategies on consumer responses to suboptimal products.Existing research has separately demonstrated effects of sustainabilitypositioning (e.g., Del Giudice et al., 2016; Quested et al., 2011) andauthenticity positioning (e.g., Beverland & Farrelly, 2010; Morhartet al., 2015) for regular products. Studies investigating marketingstrategies for suboptimal products have demonstrated effects of claimsused in practice, such as messages focusing on health aspects, goodtaste, and lower prices (Louis & Lombart, 2018). Yet, theoretical andempirical comparisons between strategies are essential to advanceknowledge about the differences and similarities between these stra-tegies and to advance supply chain decision-making. Indeed, the cur-rent studies indicate that an authenticity positioning of suboptimalproducts can be more beneficial than a sustainability positioning, be-cause it effectively increases quality perceptions.By combining positioning strategies with pricing strategies, our re-

search demonstrates that the effects of positioning strategies depend onthe pricing situation. In both studies, authenticity positioning positivelyaffected purchase intentions and quality perceptions when consumersreceived a price discount or when prices were similar to those of op-timal products. Conversely, authenticity positioning did not affectpurchase intentions when consumers received a moderate price dis-count. The effects of price discounts have been shown to vary de-pending on the size of the discount and on whether consumers expect adiscount (Kalwani & Yim, 1992). It is possible that the positioningstrategies influence consumers’ expectations concerning discounts, suchthat consumers would either expect a large discount (e.g. with sus-tainability positioning) or no discount (e.g. with authenticity posi-tioning), but not a moderate discount. In general, discounts are costly tosupply chains and can negatively affect consumers’ reference prices andquality perceptions (Palazon & Delgado-Ballester, 2009). Therefore, itseems promising that sustainability and especially authenticity posi-tioning can increase purchase intentions at least as much as price dis-counts.

4.2. Limitations and future research

There are several remarks that could be made with respect to ourfindings. Although we think that none of these is critical to our findings,it is valuable to shortly discuss each. First, some of the results were notconsistent across the studies. Study 1 showed no differences in purchasechoice and intention between authenticity and sustainability posi-tioning, except for the moderate price discount situation (where thesustainability positioning was more effective). In contrast, in Study 2,authenticity positioning lead to higher purchase choice and intentioncompared to sustainability positioning, except for the moderate pricediscount situation. It seems likely that these differences depend on theoperationalization of the multi-dimensional construct authenticity.Whereas Study 1 focused on the naturalness dimension of authenticity,Study 2 focused on the genuineness dimension. This suggests that fo-cusing on more than ‘just’ the naturalness dimension of authenticity(e.g., genuineness) is more effective, as is also supported by earlierresearch on the authenticity of regular products (Bryła, 2015; Morhartet al., 2015). Future research could directly compare the relative ef-fectiveness of the different authenticity dimensions to market sub-optimal products.Second, the pricing effects are somewhat inconsistent across the

studies. Specifically, the studies demonstrated some interactions be-tween positioning and pricing, but these interactions were mixed acrossstudies and dependent variables. Both studies did, however, show that amoderate price discount combined with sustainability positioning in-stead of an authenticity positioning increased quality perceptions of

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

256

suboptimal products. It is possible that combining a positioning thatsignals high product quality (authenticity) with a price that signalsdoubtful product quality (a moderate price discount) can confuse con-sumers, or lead them to misattribute their motivation to purchase (e.g.,“I chose it because it was on sale”) (Darke & Chung, 2005). Such aneffect would not occur for larger discounts, as such discounts can beperceived as sacrifices that companies valuing authenticity are pre-pared to make for consumer welfare (Kadirov, 2015). Future research isneeded to further examine the (underlying process of) potential inter-actions between the positioning and pricing strategies for suboptimalproducts.Third, the present research focused on purchase and waste inten-

tions and not on consumer behavior. Purchase and waste intentions arestrong predictors for behavior, also in the domain of environmentallyresponsible behavior (e.g., Follows & Jobber, 2000). Similarly, thecurrent research focused on oddly shaped fruits and vegetables, butother types of sub-optimality exist (e.g., in packaging such as a tornwrapper). It is therefore valuable to extend the current findings topurchase and waste behavior for varying types of suboptimal products.Finally, it is possible that promoting suboptimal fruits and vege-

tables as being natural can have other, undesired effects that were notinvestigated in the current studies. For example, consumers may in-correctly equate authentic with organic and generate the idea that theproducts are without pesticides or chemicals (Vega-Zamora et al.,2014). Therefore, it is important for future research to explore whetherconsumers confuse authentic with organic and how such confusion canbe avoided.

4.3. Conclusion

Thus far, supply chain actors have been unwilling to market sub-optimal products, and consumers have been unwilling to purchasethem. It appears that suboptimal products require a more unique ap-proach than “simple” price discounts to address consumers’ unwill-ingness to purchase these products. The present studies suggest thatretailers can sell suboptimal products without price discounts by ap-proaching the weaknesses of ugly products as authentic and sustainableelements. Emphasizing the genuineness or naturalness of suboptimalproducts appears to be a unique selling point for these products, andmight provide a cost-effective solution for food waste issues. Thus,there is beauty in ugliness after all.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Millie Elsen, Erica van Herpen, and JornaLeenheer for their invaluable contributions to the data collection andtheory development of the paper, and Karolien van den Akker for hervaluable feedback on a later version of the paper.

Funding

Study 1 was conducted in the context of a contract with theConsumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (Chafea) onbehalf of the European Commission Directorate-General for Justice andConsumers. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of Roxannevan Giesen and Ilona de Hooge only and do not represent the EuropeanCommission/Chafea position.

Appendix A

Examples of Positioning and Pricing manipulations used in Study 1

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

257

Appendix B

Items and factor loadings of the Quality perceptions measures in Study 1 and Study 2

Item Study 1 Study 2

1. Taste? 0.90 0.842. Flavor? 0.90 –3. Delicious? 0.90 –4. Quality? 0.86 0.855. Healthiness? – 0.816. Safety? – 0.777. Value for money? – 0.78

Reliability (α) 0.94 0.90Note. Items in study 1 were answered using 9-point scales and in study 2 on 7-point scales with end points labelled (very bad taste/very unhealthy/very unsafe/of very bad quality/hardly any value for money) to (very good taste/very healthy/very safe/of very good quality/much value formoney).

Appendix C. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.02.020.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

258

References

Abrahamse, W., Steg, L., Vlek, C., & Rothengatter, T. (2005). A review of interventionstudies aimed at household energy conservation. Journal of Environmental Psychology,25(3), 273–291.

Ahmetoglu, G., Furnham, A., & Fagan, P. (2014). Pricing practices: A critical review oftheir effects on consumer perceptions and behaviour. Journal of Retailing andConsumer Services, 21(5), 696–707.

Alcock, I. (2012). Measuring commitment to environmental sustainability: The develop-ment of a valid and reliable measure. Methodological Innovation Online, 7(2), 13–26.https://doi.org/10.4256/mio.2012.008.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., de Hooge, I. E., Amani, P., Bech-Larsen, T., & Oostindjer, M.(2015). Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability,7, 6457–6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066457.

Aschemann-Witzel, J., de Hooge, I. E., Rohm, H., Normann, A., Bossle, M. B., Grønhøj, A.,& Oostindjer, M. (2017). Key characteristics and success factors of supply chain in-itiatives tackling consumer-related food waste–A multiple case study. Journal ofCleaner Production, 155, 33–45.

Bendix, R. (1992). Diverging paths in the scientific search for authenticity. Journal ofFolklore Research, 103–132.

Beretta, C., Stoessel, F., Baier, U., & Hellweg, S. (2013). Quantifying food losses and thepotential for reduction in Switzerland. Waste Management, 33, 764–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2012.11.007.

Beverland, M. B., & Farrelly, F. J. (2010). The quest for authenticity in consumption:Consumers' purposive choice of authentic cues to shape experienced outcomes.Journal of Consumer Research, 36(5), 838–856. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/615047.

Binninger, A.-S. (2017). Perception of naturalness of food packaging and its role inconsumer product evaluation. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 23(3), 251–266.

Bratanova, B., Vauclair, C. M., Kervyn, N., Schumann, S., Wood, R., & Klein, O. (2015).Savouring morality: Moral satisfaction renders food or ethical origin subjectivelytastier. Appetite, 91, 137–149.

Brautigam, K.-R., Jorissen, J., & Priefer, C. (2014). The extent of food waste generationacross EU-27: Different calculation methods and the reliability of their results. WasteManagement & Research, 32(8), 683–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X14545374.

Bruhn, M., Schoenmüller, V., Schäfer, D., & Heinrich, D. (2012). Brand authenticity:Towards a deeper understanding of its conceptualization and measurement. Advancesin Consumer Research, 40https://ssrn.com/abstract=2402187.

Bryła, P. (2015). The role of appeals to tradition in origin food marketing. A surveyamong Polish consumers. Appetite, 91, 302–310.

Bunn, D., Feenstra, G. W., Lynch, L., & Sommer, R. (1990). Consumer acceptance ofcosmetically imperfect produce. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 24(2), 268–2790022-0078/0002-268.

Buzby, J. C., & Hyman, J. (2012). Total and per capita value of food loss in the UnitedStates. Food Policy, 37, 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.06.002.

Buzby, J. C., Hyman, J., Stewart, H., & Wells, H. F. (2011). The value of retail- andconsumer-level fruit and vegetable losses in the United States. The Journal ofConsumer Affairs, 45(3), 492–515.

Chen, S.-F. S., Monroe, K. B., & Lou, Y.-C. (1998). The effects of framing price promotionmessages on consumers' perceptions and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing,74(3), 353–372.

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: Areview and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419.

Darby, M. R., & Karni, E. (1973). Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud.Journal of Law and Economics, 16, 67–88.

Darke, P. R., & Chung, C. M. (2005). Effects of pricing and promotion on consumerperceptions: It depends on how you frame it. Journal of Retailing, 81(1), 35–47.

de Hooge, I. E., Oostindjer, M., Aschemann-Witzel, J., Normann, A., Mueller Loose, S., &Almli, V. L. (2017). This apple is too ugly for me! Consumer preferences for sub-optimal food products in the supermarket and at home. Food Quality and Preference,56, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.09.012.

de Hooge, I. E., van Dulm, E., & van Trijp, H. C. (2018). Cosmetic specifications in thefood waste issue: Addressing food waste by developing insights into supply chaindecisions concerning suboptimal food products. Journal of Cleaner Production, 183,698–709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j/clepro.2018.02.132.

Del Giudice, T., La Barbera, F., Vecchio, R., & Verneau, F. (2016). Anti-waste labeling andconsumer willingness to pay. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing,28(2), 149–163.

FAO. (2013). Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources (Publication no.http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3347e/i3347e.pdf. Retrieved September 8, 2014,from FAO.

Follows, S. B., & Jobber, D. (2000). Environmentally responsible purchase behaviour: Atest of a consumer model. European Journal of Marketing, 34(5/6), 723–746.

Fritz, K., Schoenmueller, V., & Bruhn, M. (2017). Authenticity in branding–exploringantecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. European Journal of Marketing,51(2), 324–348.

FUSIONS. (2014). FUSIONS Definitional Framework for Food Waste, Full report.Garnett, T. (2011). Where are the best opportunities for reducing greenhouse gas emis-

sions in the food system (including the food chain)? Food Policy, 36, S23–S32.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.10.010.

Godfray, H. C. J., Beddington, J. R., Crute, I. R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J. F., ...Toulmin, C. (2010). Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 Billion people. Science,

327, 812–818. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1185383.Groves, A. M. (2001). Authentic British food products: A review of consumer perceptions.

International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25(3), 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1470-6431.2001.00179.x.

Hersleth, M., Næs, T., Rødbotten, M., Lind, V., & Monteleone, E. (2012). Lamb meat —Importance of origin and grazing system for Italian and Norwegian consumers. MeatScience, 90(4), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.11.030.

Kadirov, D. (2015). Private labels ain’t bona fide! Perceived authenticity and willingnessto pay a price premium for national brands over private labels. Journal of MarketingManagement, 31(17–18), 1773–1798.

Kalwani, M. U., & Yim, C. K. (1992). Consumer price and promotion expectations: Anexperimental study. Journal of Marketing Research, 90–100.

Kantor, L. S., Lipton, K., Manchester, A., & Oliveira, V. (1997). Estimating and addressingAmerica’s food losses. Food Review, 20(1), 2–12.

Kyutoku, Y., Hasegawa, N., Dan, I., & Kitazawa, H. (2018). Categorical nature of con-sumer price estimations of postharvest bruised apples. Journal of Food Quality.

Loebnitz, N., & Grunert, K. (2015). The effect of food shape abnormality on purchaseintentions in China. Food Quality and Preference, 40, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.08.005.

Loebnitz, N., Schuitema, G., & Grunert, K. (2015). Who buys oddly shaped food and why?Impacts of food shape, abnormality, and organic labeling on purchase intentions.Psychology & Marketing, 32(4), 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20788.

Louis, D., & Lombart, C. (2018). Retailers’ communication on ugly fruits and vegetables:What are consumers’ perceptions? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 41,256–271.

Lu, A. C. C., Gursoy, D., & Lu, C. Y. (2015). Authenticity perceptions, brand equity andbrand choice intention: The case of ethnic restaurants. International Journal ofHospitality Management, 50, 36–45.

Margetts, B. M., Martinez, J., Saba, A., Holm, L., Kearney, M., & Moles, A. (1997).Definitions of 'healthy' eating: A pan-EU survey of consumer attitudes to food, nu-trition and health. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 51(2), S23.

Morhart, F., Malär, L., Guèvremont, A., Girardin, F., & Grohmann, B. (2015). Brand au-thenticity: An integrative framework and measurement scale. Journal of ConsumerPsychology, 25(2), 200–218.

Moulard, J. G., Raggio, R. D., & Folse, J. A. G. (2016). Brand authenticity: Testing theantecedents and outcomes of brand management's passion for its products. Psychology& Marketing, 33(6), 421–436.

North, A., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1997). In-store music affects productchoice. Nature, 390(6656), 132.

O’Connor, K., Carroll, G. R., & Kovács, B. (2017). Disambiguating authenticity:Interpretations of value and appeal. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0179187.

Olson, J. J. (1977). Price as an informational cue: Effects in product evaluation. In A. G.Woodside, J. N. Sheth, & P. B. Bennett (Eds.). Consumer and industrial buying behavior(pp. 267–286). New York: North Holland Publishing Company.

Palazon, M., & Delgado-Ballester, E. (2009). Effectiveness of price discounts and premiumpromotions. Psychology & Marketing, 26(12), 1108–1129.

Parfitt, J., Marthel, M., & MacNaughton, S. (2010). Food waste within food supply chains:Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philosophical Transactions: BiologicalSciences, 365(1554), 3065–3081. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0126.

Porter, S. D., Reay, D. S., Bomberg, E., & Higgins, P. (2018). Avoidable food losses andassociated production-phase greenhouse gas emissions arising from application ofcosmetic standards to fresh fruit and vegetables in Europe and the UK. Journal ofCleaner Production, 201, 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.079.

Principato, L. (2018). Food waste at consumer level: A comprehensive literature review.Springer.

Quested, T. E., Parry, A. D., Easteal, S., & Swannell (2011). Food and drink waste fromhouseholds in the UK. Nutrition Bulletin, 36, 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2011.01924.x.

Rozin, P., Fischler, C., & Shields-Argelès, C. (2012). European and American perspectiveson the meaning of natural. Appetite, 59(2), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.06.001.

Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3),355–374.

Stuart, T. (2009). Waste – Uncovering the global food scandal. London: WW Norton &Company.

Tsiros, M., & Heilman, C. (2005). The effect of expiration dates and perceived risk onpurchasing behavior in grocery store perishable categories. Journal of Marketing, 69,114–149. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30162048.

Vega-Zamora, M., Torres-Ruiz, F. J., Murgado-Armenteros, E. M., & Parras-Rosa, M.(2014). Organic as a heuristic cue: What Spanish consumers mean by organic foods.Psychology & Marketing, 31(5), 349–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20699.

Verghese, K., Lewis, H., Lockrey, S., & Williams, H. (2013). The role of packaging inminimising food waste in the supply chain of the future. Australia: CHEP.

Weller, K. E., Greene, G. W., Redding, C. A., Paiva, A. L., Lofgren, I., Nash, J. T., &Kobayashi, H. (2014). Development and validation of green eating behaviors, stage ofchange, decisional balance, and self-efficacy scales in college students. Journal ofNutrition Education and Behavior, 46(5), 324–333.

White, K., Lin, L., Dahl, D. W., & Ritchie, R. J. B. (2016). When do consumers avoidimperfections? Superficial packaging damage as a contamination cue. Journal ofMarketing Research, 53(2), 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.12.0388.

Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-endmodel and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1251446.

R.I. van Giesen and I.E. de Hooge Food Quality and Preference 75 (2019) 249–259

259