Reconstructing Macroeconomics: Structuralist Proposals and ...

Theoretical Troika: Neo-classical, Structuralist & Dependency Theory. A critical resume.

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

virgilio-rojas -

Category

Documents

-

view

36 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Theoretical Troika: Neo-classical, Structuralist & Dependency Theory. A critical resume.

Excerpts from Rojas V (2013) Latin America. When Dependency

Made Sense. Third Eye Publishers: Stockholm.

I

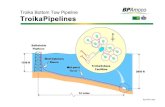

THEORETICAL TROIKA

-CATCHING-UP FROM BELOW VS ABOVE, CATCH-22 FROM WITHOUT

Conflicting accounts of Latin American late industrialization have largely gathered theoretical logistics from three trend-setting approaches at loggerheads: neoclassical and structural growth theories, and Marxist and neo-Marxist theories of dependent development. While this feuding trio has broadly problematized late industrialization in terms of “obstacles to (industrial) growth and development” (or alternatively, impediments to dynamic capitalist accumulation), there has been vicious internecine strife on the specification of causal variables and corrective industrial strategies, and how these relate to the concept of development itself. Of the three, the first two have alternated in intellectually furnishing and legitimizing strategic shifts in official Latin American industrial policies, elsewhere labelled as the “conservative” versus “reformist” versions of bourgeois development thinking:1 from the laissez faire staple export policies of the pre-Depression (neoclassical) era, to the pre- and early post-World War II ISI heydays (structuralist), to the recent export-led industrial thrust of the 1970s onwards (neoclassical). The third makes for a radical indictment of these dominant discourses and an attempt to construct a theory not so much of development as of “underdevelopment.”

CATCHING-UP THEORIES-FROM BELOW VS ABOVE

Conjointly, contending catching-up theories depart from the nation-state as central unit of analysis and conceptually collapse industrial growth with economic development, the latter

1

1For an illuminating brief review see Clements (1980) From Right to Left in Development Theory. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. Equally helpful in reconstructing the major assumptions and theoretical divisions marking these three traditions have been the more recent reviews of Bernard & Ravenhill (1995) “Beyond Product Cycles & Flying Geese,” World Politics, 17: 171-209; Kiely, Ray (1994) “Development Theory & Industrialization: Beyond the Impasse,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 24, No. 2: 133-60; and Jenkins, Rhys (1992) Theoretical Perspectives” (Ch. 5) in Hewitt, Johnson & Wield (eds.), op.cit.

in turn perceived as the quintessential product of rational factor mobilization and allocation (i.e., of land, labor & capital). There is also a shared tendency to read off the catching-up process in the ideal-type terms of precedent Western competitive capitalism of late 19th century vintage. Hostilities center however, as the labels conservative and reformist aptly suggest, on whether to attribute this primeval allocative function to either pure market or market-rehabilitating state forces. This clash between neoclassical market versus structuralist state-centered growth theories finds its verbatim translation in the rift between postwar import substitution and export-oriented industrial strategies. For neoclassicists, the market is sacrosanct and considered as the ultimate allocating mechanism of scarce factors, thereby serving as the principal guarantor of growth. In a perfectly competitive market scenario, as they argue, where transactions among individual producers and consumers were intrinsically motivated by rational profit-maximizing-cum-cost-minimizing instincts, factor price/quantity disequilibria will eventually even out according to the universal law of supply and demand. Whether in the North or South, the market will, if only un-perturbed, guarantee that factors of production respond to changes in prices and wages in the most efficient/profitable way possible, and that, as far as industrial activity is concerned, enterprises failing to adjust to these signals will eventually be flushed out by competition. In this vein, pre-existing factor endowment disparities among national economies––particularly in the South where mobilization of capital for industrial investments and expansion is regarded as an acute problem––will, assuming perfect transnational factor mobility, be rectified over time by international free trade and productive specialization in areas of comparative advantage.2 Obstacles to growth equate in the neoclassical sense to any and all variables restricting the free interplay of market forces and retarding dynamic industrial entrepreneurship and development to evolve naturally from “below.” Neoclassical principles are recycled into practical use by three inter-related policy prescriptions currently in high fashion in official development circuits: a) limited and selective state economic intervention; b) limited price distortions (“getting prices right”); c) an outward-looking export promotion strategy.3 Limited government intervention entails policies such as the removal of state subsidies to industry, minimum wage legislations, and price controls. In turn, these, together with a realistic exchange rate, will lead to low levels of factor price distortion4 (“so that factor prices may reflect the true opportunity costs of resources being used”),5 which facilitates “correct price signals,” to which investors and consumers respond. Therefore, a close correlation exists between a low level of price distortion and economic growth.6

2

2Neoclassicist concern with the causes of national and international market equilibrium, international specialization in terms of comparative advantage, and the effective market allocation of resources finds its most politicized expression in the classic work of Rostow. Among the most crucial impediments to growth in the less developing countries, according to him, consists in the mobilization of domestic and foreign savings in productive investments. Rostow (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: CUP (p. 3)

3see Kiely (1994), op.cit.

4Factor price distortions refer in the neoclassical sense to situations in which factors of production are paid prices which do not reflect their competitive market prices due to institutional arrangements that tamper with the free workings of supply and demand. Todaro, M.P. (1977) Economics for a Developing World. London: Longman (p. 418)

5ibid.: 427.

6World Bank, 1983: 60-3.

Finally, export promotion allows government to import goods in which it does not possess comparative advantage in return for the export of goods which it does produce cheaply and efficiently. While neoclassicists acknowledge that a great deal of Latin American and Third World industrialization has occurred without export promotion, it is argued that this has been inefficient and unsustainable in the long haul.7 As earlier noted, however, these basic tenet lost much steam in favor of structuralist thinking during the Depression and interwar years when Latin America was reeling under the disastrous downturn of world staple export markets and incorrigible balance of trade and payments (BOT/P) crises. Such disconcerting trends led pioneering structuralists like Raul Prebisch to argue that there constantly were powerful internal and external structural (i.e., socioeconomic and political) forces operating against market, technological, and industrial dynamism in Latin America. In sinister ways, the latter issues were held hostage internally and externally by oligarchic vested interests in tandem with the “asymmetrical” nature of “core-periphery” trade relations. From within, industrial entrepreneurship was held back by agro-comprador elites whose productive and consumption patterns were profligately prejudiced toward low-value added staple and mineral exports and high value-added imported luxury goods. Oligarchic monopoly over wealth and power restricted factor mobility and rational resource allocation (fostering supply inelasticities), recreated skewed income and ownership structures with their corresponding limiting impact on domestic demand, and reinforced BOT/P maladies by dint of capricious consumption. All of which throttles indigenous industrial expansion. Further, these internal structural constraints are vindicated rather than vitiated from without by by the proverbial classical and neoclassical growth catalyst––international trade, whose terms, according to one author,8 are “constantly moving against the primary producing countries” (i.e., the ratio of index of export versus import prices). Structuralist headquarters, ECLA, rejects classical and neoclassical overindulgence in the “gains of trade,” which in effect smokescreens the essentially exploitative nature of inter-national exchange. Adverse terms of trade as key source of chronic balance of payments (BOP) problems take their cue in another sense from the contrastingly high “income elasticity of demand for imports of the center compared to that of the periphery.”9

As opposed to the neoclassicists, structuralists endorse a state-orchestrated, albeit non-coercive, catching-up strategy from above, in the light of the market’s inert incompetence in promoting decisions and policies that eliminate structural obstacles to growth and self-sustainable industrialization. The task of eliminating external and internal constraints calls for systematic state interference. For instance, with balance of payments, i.e., through protection and import controls. Or, in accelerating the process of import substitution and diversification such that

3

7State protection of domestic industry leads to the subsidizing of expensive producers transferring in effect these costs in the marketplace to consumers. This problem is fostered by state allocation of licenses for selected imports and state regulation of the financial markets. Both these forms of rationing encourage the promotion of speculative, rather than productive economic activity. World Bank Report (1985) Oxford: OUP (pp. 37-41)

8 Hirschman (1964) quoted from Clements, op cit.: 21.

9 ibid. Income elasticity, conventionally defined here as the proportionate change in the quantity of commodity demanded after a unit proportionate change in the income of consumers with prices held constant. Generally, luxury items enjoy high income elasticities, while basic items, such as food and inferior goods usually comprising Third World exports, command respectively low and negative elasticity values. It is assumed that countries exporting commodities with low income elasticities will suffer worsening terms of trade problems in the long-run if world economic growth occurs, because they will have a falling share of total spending.

rigid foreign exchange barriers are avoided. Not to mention in the sense of speeding up factor mobility at intra- and inter-sectoral levels via comprehensive agrarian and income redistributive policies designed to change demand structures and the scope of domestic markets in favor of industry. Or in the mobilization of infrastructural investments, reduction of population growth, boosting of national savings, selection of appropriate technology. Lastly, state intrusion may, under given conditions, go for the elimination of outdated foreign enclave capital, yet at the same time accept “dynamic” foreign capital, one which takes a “determined share in the intensive process of industrialization.”

CATCH-22 FROM WITHOUT -DEPENDENCY THEORY, THE RADICAL CRITIQUE

But as the once vibrant ISI regimes of the 50s were one after the other thrown out of kilter into massive recession in the late 1960s and early 1970s and foreign debt crises of the early 1980s, the structuralist paradigm that informed them also fell into disrepute. Moreover, underneath the debris of the ISI collapse lay deteriorating conditions of mass poverty and social marginalization, lingering import (technological and financial) dependency, and debilitating trade and payments imbalances. Ironically enough, they were those very same maladies structuralist ISI policies wished to address in the first place. These transparent anomalies––the growth-poverty-dependency paradox––inadequately captured by either one of the dominant discourses, provided fertile ground in which neo-Marxists and critical structuralists were able to merge and breed a whole new tradition in development thinking––dependency theory. Due to its complex intellectual origins though, theoretical positions within this school of thought elude easy summary. Nevertheless, a central over-bridging argument among them is that the dependency factor built into Latin American late industrialization operates in favor of underdevelopment rather than development. Whether or not capitalist development is fully compatible with a position of dependence is, however, a hotly contested issue, which counterpoises radical exponents like Andre Gunder Frank with more moderate dependistas like Cardoso. An issue approached in either mutually exclusive terms by radicals as a Catch-22-like “development of underdevelopment,” or more inclusively by moderates as a distinct type of “development-with-a-dependency-catch-to-it.” By ironing out noted diversities however, it is possible to isolate a number of core assumptions on which to predicate concerted dependista position on development and under-development:10

• The most important obstacles to development were not lack of capital or entrepreneurial skills, but were to be found in the international division of labor (i.e., they were external rather than internal to the underdeveloped economy).

• This international division of labor geo-spatially occurring between the developed center and underdeveloped periphery of the capitalist world economy is reproduced and operationalized by relations of domination and unequal exchange, allowing the wholesale transfer of surfeit resources from the subordinate latter to the superordinate former.

• Insofar as the periphery was deprived of its surplus, which the center amassed to prime up its own development, development in the center somehow implied underdevelopment in

4

10This summary derives heavily from Hettne’s exquisite review. Hettne (1982) Development Theory and the Third World. Stockholm: SAREC (p. 46). For a more incisive and critical elaboration on theoretical origins of the dependency approach, see Barone (1985) Marxist Thought on Imperialism: Survey and Critique. London: Macmillan, and Wilber, ed. (1984) The Political Economy of Development and Underdevelopment. New York: Random House.

the periphery. Thus development and underdevelopment could aptly be described as “two sides of the same coin” or twin aspects of a single global process. With no exception, participants locked into this process were considered capitalist, although a distinction was made between center and peripheral versions of capitalism.

• Since the periphery was doomed to underdevelopment because of its linkage to the center, it was considered necessary for a country to sever itself from the world market and strive for self-reliance. To make this possible, nothing short of a revolutionary political transformation was called for. Following the elimination of external obstacles, development, as a more or less automatic and inherent process, would ensue.

Thus, dependency theory breaks radically with Marxist and non-Marxist orthodoxies in stating that global capitalist accumulation is only selectively, rather than indiscriminately, progressive in favor of the developed center economies. From this basic position dependistas have, in their attempts to construct a theory of underdevelopment, focused research on historically changing, specific and polyvalent (economic, political, social and cultural) dimensions of development and underdevelopment on the international, national-state, regional, firm levels, and on operative mechanisms and agencies recreating exploitative and intrinsically antagonistic relationships between center and periphery accumulation.

Subjugation and control of the periphery have, according to dependista stereotypes, been sponsored by among others:11

• class alliances forged between international capital and local agro-commercial ruling elites in the periphery, whose economic and political power have traditionally been tied up with the export-import trade and undermined, for all intents and purpose, the advance of native industrial capital.

• subservient client-states whose fiscal fortunes are, as a result of the import dependent nature of industrial activity, keyed on the vitality of the local agro-commercial and dynamic foreign controlled industrial sectors. Even in the case of home-market oriented ISI regimes in Latin America, state industrial policies have benefitted foreign manufacturing subsidiaries and thus international rather than native capital accumulation.

• monopoly ownership, innovation and control of technology by center nations, which effectively raises the cost of withdrawal from the world capitalist economy and the prospects of autonomous development in the periphery.

• the concentration of both financial and industrial capital in the center nations.• transnational corporations whose activities––proliferating in the 1950s onwards in the

periphery, both as a result of changing needs of global capitalist accumulation and radical innovations in world productive, communication and organizational technologies––have spearheaded the tighter integration of the periphery into the ambit of international capitalism. Dependista specialists on the subject (Sunkel, 1973; Radice, 1975) tried to demonstrate empirically how the international coordination of manufacturing and marketing has for instance accelerated national “disintegration” and the inability of firm and governments in the periphery to determine their own futures.

• cultural and ideological dependence flowing from economic dependency mutually reinforces each other, whereby local values and world-views have increasingly become emulative of Western patterns of thought, standards of preferences and consumption diffused via the mass media, educational system, etc.

5

11The following presentation quotes extensively from Clements (1980), op cit.

The tendency of posing the question of development and underdevelopment (or dependency) in mutually exclusive terms has, specially among radicals who toed the neo-Marxist lines of Baran and Frank, made dependency theory vulnerable to a series of devastating criticisms, ultimately leading to its near-extinction by the end of the 1970s. As Lall (1975) correctly pointed out, the dependency concept as hitherto formulated, invites circular reasoning in a way that seriously compromises its analytical currency value. For example, the exercise of distinguishing dependent from independent industrialization easily breaks down. In a sense, almost all countries––including those, which by normal standards may not be regarded as underdeveloped, do import technology, are dependent on exports, have in reality a tendency to emulate patterns abroad, contain marginalized groups as well as regions in their territory, etc. According to him, “it would perhaps be more sensible to proceed in terms of a “scale” of dependence,12 since given the fluidity of above distinction it would be hard to rule out the possibility of industrialization for a certain category of countries based on it. Other critics argued that even in a number of unmistakably full-fledged industrialized economies of the center, the development process did involve varying degrees of dependency (i.e., in the context of the world market on which they were “dependent” and with very different preconditions in terms of indigenous technology and capital). Underdevelopment theory, departing from an over-dilated picture of the self-centered nature of classical capitalist development (i.e., competitive capitalism of British 19th century vintage), as one author chided (Bernstein, 1979) “cannot have it both ways.” To the extent that there is “no capitalist formation whose development” in the context of the world economy “can be (absolutely: my addendum) regionally autonomous, self-generating or self-perpetuating ... Development cannot be conceptualized by its self-centered nature and lack of dependence nor ”underdevelopment” by its dependence and lack of autonomy.”13

Reformed dependistas like Cardoso argue, in contrast to a few of his more reckless peers, that it is wrong to raise, structural bottlenecks of peripheral capitalism (e.g., limited internal market and paucity of dynamic capital) to the status of inexorable law, which to his mind are actually conjunctural rather than permanent features of peripheral capitalism. Stripped down to bare essentials, it is in this sense that retired dependista Collin Leys (1975) criticized dependency theory for being insensitive to social classes, the state, politics and ideology, and, as such, guilty of economic determinism. In similar vein, it has also been accused of reductionism from Marxist quarters (Laclau,1971, Brenner 1977, Foster-Carter 1978, Rojas 1992) for defining capitalism solely on the basis of exchange and external factors at the expense of production and internal factors . In essence, the theory is thus able to account for neither the “dual history” of capitalist development in the periphery (which, in the final analysis, was in fact shaped by the interaction of capitalist and non-capitalist modes of production and surplus extraction), nor, for that matter, the de facto positive net-effects engendered by capitalist penetration at large (Warren, 1973). Finally, in agency terms, dependency theorists often refer to the impotence of the native bourgeois classes in terms of fulfilling their “historic mission” to lead the industrial project as a key stumbling block to development in the periphery. Again, reformist dependista Cardoso, “bringing the state back in,” suggests that there is now evidence indicating that a new social category be labelled the “state bourgeoisie”––a social stratum politically able to control parastatal enterprises without necessarily having private ownership of the means of production––has emerged to fill in the vacuum. This

6

12Quoted from Hettne, op cit.: 48.

13ibid.: 49.

‘stratum,’ according to him, could possibly encourage hope of expansionist statism, quite autonomous of the interests of transnational corporations, and possessing both the political will as well as the bargaining leverage to actually push local accumulation in progressive directions.

II

WHEN DEPENDENCY MADE DEVELOPMENT SENSE

CROSSING THEORY WITH THE PRACTICE(S) OF DEPENDENCY & DEVELOPMENT

How then is the true-life story of Latin American late industrialization to be accurately told? Considering the relatively high dependency content (in terms of borrowed foreign factors) of regional postwar industrial career-building at large––a common commodity among late-industrializers––how are we to make sense of dramatic diversities to date, and the vast industrial gulf separating manufacturing giants, like Mexico and Brazil, from dwarfs like Guatemala and Honduras? Does this gulf signal the fulfillment of catching-up prophecies, that some with enough creative management––by either market liberating or market rehabilitating structural adjustments––may very well have succeeded to turn the vice of “borrowing-to-industrialize” into the virtue of relatively self-sustaining indigenous capitalist accumulation and develop-ment? Or is this merely a deceptive decoy to more divisive relations of domination operating in the world capitalist economy between superordinate Northern core industrial and subordinate Southern peripheral economies like those of Latin America, where compulsive borrowing from the former to industrialize in the latter amounts to, as it were, doubly jeopardizing native development? In this “Catch-22” perception, the extortive terms of “industrializing on credit” reinforces the unbridled transfer of re-investible surpluses from periphery to core and compels the former to pay for the costs of both its underdevelopment and core development. Surely, the reality of Latin American late industrialization falls somewhere in between these extreme positions, which tend to over-dramatize the primacy of either benefits or costs of development, one over the other. It is certainly one in which extant relations of dependency by no means cancel out development a priori. Nor is it one in which industrial growth and development automatically extinguishes dependency relations and the costs associated with them. It may very well be a fusion of both, where the degree of overlap between dependency and development will, as earlier pointed out by critics, vary along a scale depending on a panoply of intervening factors and distinct national experiences. Thus, the extent to which dependency on, for example of foreign factors, may work for or against development is a question defying predetermination and must be established empirically.

7

The double-edged story of Latin American late industrialization draws from a repertoire of rigid assumptions previewed in the preceding chapters, which have often been more asserted than empirically tested. Majority of the contributions (Weaver 1979, Evans 1979, Jongkind 1981, Finch 1981, Becker 1983) included here represents fecund attempts in the opposite direction and forms variants of the “post-dependency” (or “dependency with development”) approach cropping up in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Other works link up with either the early neoliberal critique of structuralist development economics (Diaz 1970) and postwar ISI strategy; the critical re-examination by kindred reformers of standard structural narratives on the genesis of regional late industrialization (Cardenas 1984, Fitzgerald 1984); or yet lingering attempts at recycling perspectives (Buttari 1981).

CATCHING UP WITH A ‘CATCH’ MINUS THE ’22’

What makes dependency Catch-22 accounts of Latin American late industrialization “development-blind”? This ‘visual failure’ had been linked by critical post-dependency scholars to a series of serious flaws in dependista conceptual frameworks. Such defects tend to foster a historically unilinear view of core-periphery capitalist development in which the former is vested arbitrary powers to dictate the rate and direction of the latter. Another tendency generated by such flaws is the construction of definitions and mutually exclusive distinctions (development versus underdevelopment) on the basis of an over-dilated concept of a perfectly auto-centric capitalist accumulation and ideal-type models of competitive capitalism associated with the pioneering 19th century British example. Further, noted inclinations, respectively overstate and under-state the case for external structures/factors (i.e., exchange, foreign investments, credit, etc.), relations (particularly economic) and agencies (transnational corporations and institutions) versus internal ones (production, local factors, economic, political, social and cultural relations, state, parastatal enterprises, local bourgeoisie, elite and other classes) in the industrial and accumulation processes. Finally, above-cited biases assume the existence of an intrinsically unbridgeable contradiction between global versus national/local accumulation, rationalities and strategies, as embodied in no less than the dependent nature of peripheral industrialization. In this context, where interdependency and prospective benefits therefrom are ruled out per definition, industrial catching up can only therefore make sense as a process which ultimately deepens peripheral dependency and makes the Catch-22 situation even more inescapable. While the dependency paradigm may still be partially validated by predominantly agrarian Third world economies, its analytical legitimacy has been increasingly embarrassed by a distinct set of ‘junior-or-about-to-qualify-into-major-league’ industrializing nations in Latin America and East Asia (or what Evans refers to in the following as the ‘semi-periphery’ of the world capitalist economy). These economies appear to have developed rapidly in the 1970s and onwards, not despite dependency, but, perhaps to a substantial degree, because of it. Cases which seem to stand outside the conceptual reach of dependency theory and casts serious doubt on the sustainability of basic tenets. Insights included here expand on the critical arguments delivered by pioneering post-dependistas, innovatively putting more empirical ‘bite’ to their critical ‘bark.’ Drawing from the examples of Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, Venezuela, and Uruguay, these commonly argue that under specific conditions dependency may indeed make development sense.

8

In the historical structural account of Weaver (1980), postwar Latin American late-industrialization makes sense in the general context of monopoly rather than the competitive or the financial phases of global capitalism. Some, like Brazil and Mexico, were able to industrialize more than others, i.e., along monopoly capitalist lines, because they were internally able to match the technical, social (plus related political and ideological) requirements specific to this modern ‘mode’ of capitalist production. Perspicaciously, Weaver links the origins of this diversity to contrasting types of staple export economies, which preceded and helped shape succeeding industrial patterns. Moreover, while late-industrialization has generally meant increasing internationalization and rising transnational corporate involvement in local productive activities, the ‘externalizing’ impact of which supposedly kills off indigenous capitalism in the long-run, a process of ‘internalization,’ as Evans (1979) elegantly puts it, has unfolded in the opposite direction among large market and strategically resource-rich (or in Becker’s jargon ‘bonanza’) economies like Brazil, Mexico and Peru. In the context of ‘internalization,’ dependency and ‘counter-dependency,’ have, as it were, evolved concurrently to the extent that locally incorporated (e.g., direct domestic production and markets) transnational corporations (TNCs) now have a genuine stake in advancing national accumulation in these selected cases. For all intents and purposes, these countries in the ‘semi-periphery’ have become vital ‘alternative arenas’ for TNC survival and expansion, and strategic aces in inter-corporate rivalries. Employing institutional and class analysis, Evans’ and Becker’s more agency-sensitive accounts of transnational corporate activities in the Brazilian pharmaceutical, textile, and petrochemical as well as Peruvian mining industries demonstrate that rising TNC involvement did not, contrary to dependista expectations, necessarily lead to ‘denationalization’ or loss of local control over indigenous accumulation across-the-board, but rather more complexly to ‘diversification,’ niche-specialization, and ‘triple alliances’ (Evans 1979) or ‘triads’ (Becker 1983) between state, local and foreign capitals. This is particularly the case in branches and sub-areas (or ‘buffer zones’) where no single actor had full reign. The Brazilian and Peruvian pieces both testify to the fact that while contradictions between transnational (global) and national corporate rationalities and strategies do exist, they could very well be neutralized in favor of indigenous development and collaborative ventures. In Brazil as well as Mexico and Peru, transnational corporate behavioral modification in this direction had been unwillingly influenced by the institutional nature of industries in which they operated (e.g., the oligopolistic character of petrochemical and mining), the rising centralization of state political power and entrepreneurship in vital industries, and the reunification of the once fractured native bourgeois classes (Becker‘s ‘new bourgeoisie’). That neither political autonomy nor vital economic control dissipates in the face of import dependency and proliferating foreign investments is again cogently portrayed by Venezuela (Jongkind 1981) and Uruguay (Finch 1981). These final cases put in stark relief the contrastingly extenuating effects of resource opportunity and adversity (plus the relative autonomy of the state and politics) on the course of dependent industrialization in the relatively durable democracies of oil-blessed Venezuela and resource-poor Uruguay, by either allowing a ‘forex-fat’ state in the former to buy imported factors without having to be subservient to foreign suppliers, or to transfer these costs unto local taxpayers via politically volatile and restrictive social reform, welfare cuts and tax hikes. Or by simply being an area of low priority for foreign investments, thereby forcing the state in the latter to, as it were, politically enlarge the home-market in order to industrialize by raising aggregate demand through progressive social welfare and wage reforms.

9

REFERENCES

Amin, Samir. Accumulation on a World Scale: A Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment. 2 vols. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

——. Delinking: Towards a Polycentric World. London: Zed, 1980.

——. Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formation of Peripheral Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1977.

Baran, Paul A. The Political Economy of Growth. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1957.

Barone (1985) Marxist Thought on Imperialism: Survey and Critique. London: Macmillan.

Becker, David (1983) The New Bourgeoisie and the Limits of Dependency: Mining, Class, and Power in ”Revolutionary” Peru, Princeton: PUP.

Bernard & Ravenhill (1995) “Beyond Product Cycles & Flying Geese,” World Politics, 17: 171-209.

Buttari, J (Spring, 1992) of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs, Vol. 34, No. 1 , pp. 179-214

Cardoso, Fernando H., and Enzo Faletto. Dependency and Development in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Chilcote, Ronald H. Theories of Development and Underdevelopment. Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1984.

Clements (1980) From Right to Left in Development Theory. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Evans, Peter (1979) Dependent Development: The Alliance of Multi-national, State, and Local Capital in Brazil, Princeton: PUP.

–– (1995) Embedded Autonomy: States and industrial Transformation, Princeton: PUP.

Frank, Andre G. Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Latin America: Historical Studies of Chile and Brazil. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1967.

——. "The Development of Underdevelopment." Monthly Review 18 (1966): 17–31.

——. Latin America: Underdevelopment or Revolution. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969.

——. Lumpen-Bourgeoisie: Lumpen-Development, Dependency, Class, and Politics in Latin America. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970.

Furtado, Celso (1967) Development and Underdevelopment. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gerschenkron, Alexander (1962), Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective, A Book of Essays, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

10

Hettne (1982) Development Theory and the Third World. Stockholm: SAREC.

Hewitt, Johnson & Wield (1992) Industrialization & Development. Oxford: OUP.

Jenkins, Rhys (1992) Theoretical Perspectives” (Ch. 5) in Hewitt, Johnson & Wield (eds.).

Kiely, Ray (1994) “Development Theory & Industrialization: Beyond the Impasse,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, Vol. 24, No. 2: 133-60

Kitching, G. N. Development and Underdevelopment in Historical Perspective: Populism, Nationalism, and Industrialization. London: Methuen, 1982.

Laclau, E. "Feudalism and Capitalism in Latin America." New Left Review (May–June 1971): 19–38.

Leys, Colin. "Kenya: What Does 'Dependency' Explain?" Review of African Political Economy 17 (1980): 108–113.

Love, Joseph. 2005. The Rise and Decline of Economic Structuralism in Latin America. Latin American Research Review 40 (3): 100–125.

Mamdani, Mahmood. 1996. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Marchand, Marianne, and Jane Parpart, eds. Feminism/Post-Modernist Development. London: Routledge, 1995.

Mouzelis (1996) “Modernity, Late Development and Civil Society,” in Rudebeck, Törnquist & Rojas (eds.) Democratization in the Third World: Concrete Cases in Comparative and Theoretical Perspective. Uppsala University: Seminar for Development Studies.

Nafzinger, E W (1984) The Economics of Developing Countries. Belmont: Wadsworth Pub Co.

Pieterse, Jan N. Development Theory: Deconstructions/Reconstruct-ions. London: Sage, 2001.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L'Ouverture, 1972.

Rojas, V (1992) ”The Mode of Production Controversy:Anatomy of a Lingering Theoretical Stalemate.” Philippine Left Review, Issue 4 (Sept).

Rostow (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: CUP.

Sunkel O. (1966), 'The Structural Background of Development Problems in Latin America' Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 97, 1: pp. 22 ff.

Sunkel O. (1973), 'El subdesarrollo latinoamericano y la teoria del desarrollo' Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno Editores, 6a edicion.

Thirlwall, A.P. (1994) Growth and Development. London: Macmillan.

Todaro, M.P. (1977) Economics for a Developing World. London: Longman.

Tucker, Vincent. "The Myth of Development: A Critique of a Eurocentric Discourse." In Critical Development Theory, edited by R. Munck and D. O'Hearn, 1–26. London: Zed, 1999.

Wallerstein, Immanuel M. The Capitalist World Economy: Essays. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

11

——. The Modern World System. Vol. 1: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic, 1974.

——.The Modern World System. Vol. 2: Mercantilism and Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600–1750. New York: Academic, 1980.

––––.The Modern World-System, Vol. III: The Second Great Expansion of the Capitalist World-Economy, 1730-1840's. San Diego: Academic Press, 1989.

Warren, Bill. Imperialism, Pioneer of Capitalism. London: New Left Books, 1980.

Williams, Eric E. Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944. Weaver, Frederick Stirton (2000) Latin America in the World Economy. Boulder: Westview Press.

Wilber, ed. (1984) The Political Economy of Development and Underdevelopment. New York: Random House.

World Bank Report (1985) Oxford: OUP.

12