The Well-Being of a City and Animal Shelter Funding: An In-Depth Look Inside Philadelphia’s Tragic...

-

Upload

douglas-ross-cpa -

Category

News & Politics

-

view

482 -

download

0

Transcript of The Well-Being of a City and Animal Shelter Funding: An In-Depth Look Inside Philadelphia’s Tragic...

The Well-Being of a City and Animal Shelter Funding

An In-Depth Look Inside Philadelphia’s Tragic Animal Control Function and How it can be Saved

Douglas M. Ross, CPAFounder & CEO, Aces United LLC

Table of ContentsI. AbstractII. Introduction

i. A History of Philadelphia’s Animal Care and Control Function

ii. Philadelphia’s Underfunded Animal Control Functioniii. The Well-Being of Philadelphians

III. Results and AnalysisIV. The Animal Welfare and Human Well-Being ConnectionV. Shared Solutions to Animal and Human Maltreatment

i. Educationii. Volunteerismiii. Resource Availability

VI. Conclusion

Page 1 of 9

I. Abstract In this study, the 10 largest US cities (measured by population) are compared by analyzing their overall well-being in relation to their respective investment in Animal Care and Control Functions (ACCF). The results of this study will prove that there is a correlation between the aforementioned investment and the overall well-being of the city’s population. This paper will not suggest that there is a causal relationship between the two variables. The purpose of this paper is to compel the city of Philadelphia, which has the lowest-quality of well-being and the lowest investment in their ACCF, to recognize this correlation, understand the ways that improving animal welfare can improve human well-being, and encourage Philadelphia’s governing body to increase their investment in its animal control function. In this article, we will present a brief history of Philadelphia’s animal care and control function, display the inadequate funding of that function as well as the poor quality of well-being experienced by Philadelphians. Finally, we will propose a way through which both animal welfare and human well-being can be improved through increased investment in the city’s animal care and control function. II. Introduction When compared to the 10 largest cities in the US, Philadelphia (ranking 5th in population) provides the lowest amount of funding to its ACCF. The analysis offered in this paper will also support the argument that of the 10 largest cities, Philadelphia offers the lowest quality of well-being to its human residents. These two variables, while lacking an obvious correlation, they do in fact pose a number of possibilities for a city official to consider: Can the well-being of a city’s neglected animal population be directly related to the well-being of its citizens? Does the inadequate funding of a city’s animal shelter shine a light on poorly managed city funds? Is there a connection between an ACCF’s ability to care for its neglected animal population (which is largely determined by a well-funded Primary Intake Shelter (PIS)) and the treatment of its underprivileged human population? i. A History of Philadelphia’s Animal Care &

Control Function The City of Philadelphia has had a unique and complex relationship with its neglected animal population for most of the past two decades. In the 30 years leading up to 2002, Philadelphia had a long-standing contract in place with the 1 A common misperception is that all “SPCA’s” are related; however, the Pennsylvania SPCA is an independent organization and is not a branch of any other humane society.

Pennsylvania Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (PSPCA)1 to serve as its PIS. In 2002, Philadelphia was faced with losing the services of the PSPCA due to funding issues and the city’s unwillingness to adopt the PSPCA’s pit bull policy (Philadelphia refused to outlaw the breed while it was the PSPCA’s policy to euthanize them). With the PSPCA’s departure, Philadelphia was forced to quickly put a shelter operation in place. The solution resulted in the formation of the Philadelphia Animal Care

and Control Association (PACCA), which fell under control of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. The building that PACCA operated out of was the facility that the PSPCA had previously utilized as an intake shelter. It was not equipped to handle the full scope of services of a fully-functioning animal control shelter at the time. As

such, that building had to be immediately retrofitted to accommodate the day to day shelter operations. When looking at our current situation, it is important to contemplate this hasty transition. The old PSPCA facility was not designed with forethought about the space and personnel needed to maintain a high life-saving rate. Suddenly, programs centered on adoptions, fostering and expanded clinic services like spaying and neutering, previously considered programs the PSPCA would oversee, were now the responsibility of PACCA. The retrofitting of the facility involved the installation of used kennel runs (which are now 14 years older than when they were installed). Under the initial administration of PACCA, the shelter was described as a “grisly murder mill”2 until 2004 when Daily News’ Stu Bykofsky wrote a five-part exposé on the shelter. Bykofsky’s work led to a reformist administration of PACCA between 2005 and 2008. In 2009 the PSPCA, under new leadership, took back the city contract to operate as the city’s primary intake shelter.

2 The (Scary) Truth About Cats and Dogs. April 21, 2009. Philadelphia Weekly

Page 2 of 9

The chaotic transition of responsibilities shifting from PACCA to the PSCPA led to the dissolution of PACCA and the facility in which they operated was (once again) taken over by the PSPCA. In 2011, it was determined that the PSPCA’s contract with the city of Philadelphia would terminate on March 31, 2012. As a response to this, the Animal Care and Control Team of Philadelphia (ACCT) was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) in 2011 and they took over the city contract in 2012, which they hold to this day. As we can see, the Animal Care and Control Functions (ACCF) in Philadelphia have changed frequently, and often abruptly, over the past 15 years. Placing the complexity and politicking of these transactions aside, it is important to note two things: 1. The facility in which ACCT currently operates has

been a constant variable in the animal welfare equation. The facility was arguably inadequate when it was implemented in 2002 and undoubtedly inadequate to handle the transition in 2012. Little of the infrastructure has changed since conception, leading to its current decaying conditions (read further in details).

2. The allocation of city funds to its ACCF take on a new meaning when considering the change from the PSPCA to the Animal Care and Control Team of Philadelphia (ACCT).

According to their 2011 Form 990 (the final year of their contract with the city of Philadelphia), the PSPCA reported $13.2 million in annual revenues. Of this, $3.4 million was provided by the city contract. In 2011, the PSPCA reported an intake of 41,162 canines and felines. According to their 2012 Form 990 (without the city contract), the PSPCA reported annual revenues of $10.7 million of which $1.1 million was provided by the city of Philadelphia (reflecting the portion of the year that they still held the contract). The PSPCA’s 2012 intake was reported as 7,789 canines and felines. The purpose of this illustration is to show that the PSPCA had a significantly larger sum of money to handle Philadelphia’s booming neglected animal count. The PSPCA’s animal intake to funds available ratio skyrocketed from $259 to $1,694 as a result of the transition.

3 "American FactFinder – Results". United States Census Bureau, Population Division.

ii. Philadelphia’s Underfunded ACCF Function

As mentioned earlier, when compared to the 10 largest cities in the US, Philadelphia provides the smallest amount of funding to its ACCF. This statement can be supported by analyzing three variables: 1. The population of the 10 largest cities as of July 1, 2015,

as estimated by the United States Census Bureau3. 2. The amount of money allocated to the ACCF in a city’s

annual budget. a. It is important to note that every city in this study has

a designated primary intake shelter (PIS). The PIS is the first destination for any animal obtained by law enforcement and required to take in any animal surrendered by its owner. The PIS provides a number of lifesaving services to the animals in a community including vaccinations, micro-chipping, neuter/spay operations, and licensing. Without exception, the funds allocated in a city’s budget to support their ACCF benefit the designated PIS.

b. A city’s ACCF manifests itself in one of two ways: i. The city designates a non-profit, 501(c)(3)

organization to serve as its PIS (normally through a bidding process) and provides annual funding to that organization.

ii. The city sustains a department within the Mayor’s office; making the ACCF a branch of city government.4

3. The number of “neglected” canines and felines taken in by a city’s primary intake shelter (PIS). i. For this study, a “neglected” animal refers to one

that has been abandoned, abused, surrendered, confiscated by authorities, or stray.

4 Of the 10 largest cities in the US, three have elected to utilize a non-profit and seven directly incorporate animal control into their governing body.

Page 3 of 9

iii. The Well-Being of Philadelphians Philadelphia offers the lowest quality of “well-being” to its residents. “Well-being” can be defined as a state of safety, comfort, and financial health. For the purposes of this paper, a city’s overall “well-being” is determined by analyzing a number of measured variables:

1. City Crime Index5 2. Poverty Rate6 3. Homelessness Per Capita7 4. Mean Home Price8 5. Unemployment Rate9 6. Median Household Income10 7. Percentage of Population without High School

Diploma11 8. Percentage of Population without Health insurance12 9. US News & World Report Z-Score13

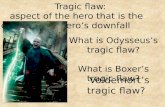

III. Results and Analysis The results of the study’s calculations and scoring are charted in Table 5 below: Table 5. AWI Comparison by WBI Score Ranking

The results are displayed in order of a city’s Well-Being Index ranking, from lowest (most desirable) to highest (least desirable). We can reasonably conclude that there is a

5 Obtained from City-Data.com, their Crime Index is a calculation of the number of Murders, Rapes, Robberies, Assaults, Burglaries, Thefts, Auto Thefts, and Arson per 100,000 residents. 6 Obtained from the City-Data.com report for the year-ending 2015. 7 Obtained from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development for 2015. https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/4832/2015-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness/ 8 Obtained from the City-Data.com report for the year-ending 2015. 9 Obtained from the City-Data.com report for adults over the age of 25 in 2015.

correlation between a city’s WBI Score and their Animal Welfare Index. While there may not be an alarming relationship between these two variables we can make a few meaningful observations:

1. The cities at the higher-end of the WBI spectrum have better funded ACCFs than the cities on the lower end.

2. Los Angeles County could be considered an outlier in this study. By far, they provide the most funding to their ACCF. However, we should take into account that they have the second highest euthanasia rate in the country. This raises a number of other questions surrounding the overall efficiency of their shelter’s operations.

3. The City of Philadelphia has an extremely low AWI score and when taking into account the correlation between WBI and AWI, it is not surprising that the city’s residents experience the lowest quality of well-being.

Analyzing the graphically illustrated results in Table 5.1 provides us with a much clearer understanding of the relationship between a community’s well-being and its correlation to animal welfare. The line in Table 6 displaying the trending average of the results shows an obvious relationship. IV. The Animal Welfare and Human Well-Being Connection The relationship between the human and animal condition has been studied for decades. While studies have confirmed the connection between low socioeconomics and high prevalence of animal abuse and neglect, these studies have not explored the role that city-funded animal shelters play in this relationship. Accordingly, this section will offer a relatively new way of thinking about the role city-funded animal shelters play. In 2010, Jodi Levinthal, a University of Pennsylvania PhD, wrote a dissertation entitled “The Community Context of Animal and Human Maltreatment.14. Her study offers an

10 Obtained from the City-Data.com report for the year-ending 2015. 11 Obtained from the City-Data.com report for the year-ending 2015 noting the number of adults over the age of 25 that have not obtained a high-school (or equivalent) diploma. 12 Data obtained from a survey conducted by Enroll America in partnership with Civis Analysis. 13 US News & World Report 2016 Report Data. Weighted value calculation of Job Market Index, Value Index, Quality of Life Index, Desirability Index, & Net Migration 14 Levinthal, Jodi, "The Community Context of Animal and Human Maltreatment: Is there a Relationship between Animal Maltreatment and Human Maltreatment: Does Neighborhood Context Matter?"

City Rank WBIScore AnimalWelfareIndexSanDiego,CA 1 31 38.25SanJose,CA 2 34 41.91NewYorkCity,NY 3 45 48.62Houston,TX 4 52 40.81Chicago,IL 5 56 25.60SanAntonio,TX 6 56 38.64Dallas,TX 7 61 23.89Phoenix,AZ 8 62 29.84LosAngeles,CA 9 71 41.17Philadelphia,PA 10 75 15.23

Page 4 of 9

unprecedented level of research demonstrating the ways that animal neglect directly correlates with demographic and neighborhood factors as well as cultural and structural aspects of block groups. Overall, her research and analysis suggests that social disorganization leads to animal neglect. The fact that her dissertation focused on the city of Philadelphia makes this information all the more relevant. Levinthal’s dissertation indicates that family violence (which is associated with a number of other social problems including teenage pregnancy, runaway and homeless youth, substance abuse, and crime) is linked to animal abuse. Levinthal states, “either form of abuse can be a strong predictor of the other. Types of crime such as burglary and graffiti positively correlate with animal abuse, as does the overall crime factor.” It is important to understand that negative human relationships and interactions often result in the mistreatment and neglect of animals and vice versa. Therefore, it’s reasonable to surmise that if the Philadelphia city government focused on improving the relationship between its human and neglected animal population while bettering the conditions of its neglected animals, the conditions of the human population of Philadelphia would similarly improve. V. Shared Solutions to Animal and Human Maltreatment

i. Education The origin of a city’s economic and socioeconomic plight can typically be traced back to the presence of, or lack of, quality education offered by a community. Children learn many critical life lessons in the classroom outside of core curriculum (e.g. Mathematics, Language Arts, Science, etc.). These lessons include, but are not limited to, compassion, respect, and responsibility for themselves, their neighbors, and the place that they live. Can we assume that crime is often the result of a breakdown in one of these areas? Is it fair to say that a person that has respect and a strong sense of responsibility to their community is less likely to vandalize their city’s property? Research confirms this supposition and therefore we can similarly conclude that a person who is compassionate and respectful to those around them is less likely to physically assault a stranger. A city cannot and should not expect for our city’s youth to learn these lessons at home and on the street.

(2010). Publicly accessible Penn Dissertations. Paper 274. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/274/

The often overlooked relationship between humans and animals offers a unique opportunity to enrich a city’s youth (and even adult) population through increased education focused on animal welfare. In Stephanie Itle-Clark’s article “Increasing Student Engagement through Animal Welfare Education and Service”15 student engagement is driven by three factors: 1) underlying need for competence 2) the extent to which students experience membership in the school, and 3) the authenticity of the task they are given. Animal welfare education and correlated service-learning can address all three of these factors. “Learner interest in animals and animal welfare issues… is reported by both students and teachers alike to be high. Utilization of a high-interest topic provides traditional pedagogy a set of teeth that supports active engagement and builds the foundation for increased engagement and success.” By enhancing our schools’ “core” curriculum with animal welfare education, a city can accomplish a number of educational goals as well as rebuild student trust in the education system. Currently in the US, there are many humane societies and animal rescue group developing and providing precisely this curriculum to public schools. Using the Human Society of Southern Arizona as an example, they provide teachers with presentations, including but not limited to:

• Animal Welfare at a Glance • School Based Community Serve Projects • Behind the Scenes Shelter Tours • Exploring Animal Careers

These incredibly useful educational tools not only teach students about the important role their local animal shelter plays but they inherently develop a deeper sense of respect and compassion for the community’s institutions. While schools across the country certainly grapple with finding “room” for these non-traditional supplementary curriculums amidst strict testing standards, the lifetime benefits of these programs are proving to be consistently compelling and worthwhile. It would be challenging to identify a better institution to develop and distribute this curriculum to a community than

15 Itle-Clark, S. (2014). Increasing student engagement through animal welfare education and service. Living Education eMagazine, 42-43, 57-58.

Page 5 of 9

the city animal shelter. As this paper will discuss in greater depth below, an underfunded animal shelter that is barely capable of providing the basic services to its homeless and neglected animals cannot begin to explore this area without increased funding.

ii. Volunteerism The value of volunteers in a community is immeasurable. The organizations that provide opportunities to volunteer are key players in the local economy, reducing the burden of government spending and investing in people through training, boosting skills and improving the employability of people on the margins of the labor market. Volunteerism also plays a key role in relationships shared within a community. Volunteer activities bring together people who might not otherwise have contact with one another, serving as a bridge between socioeconomic divides. Alexis de Toqueville (1988)16, in his classic study of American democracy, saw volunteering as a form of civic engagement through which individuals can make meaningful contributions to their own visions of societal well-being. Not all forms of civic engagement are equal in nature. Volunteers that work with pets and other animals have been shown to enjoy a variety of unique benefits, including but not limited to: decreased likelihood to suffer from depression, lowered blood pressure, and increased levels of relaxation. Volunteers in an animal shelter environment experience emotional situations that are not found in other volunteer capacities. In an animal shelter setting, volunteers encounter an overabundance of clients (animals) on a daily basis. With such high numbers of animals, both staff and volunteers are overwhelmed.17 For this as well as many other reasons, it is important for a city’s animal shelter to have an enhanced volunteer recruitment and retention program. While there is a tremendous amount of guidance available on how to develop and implement these programs, doing so is complex and requires additional funding to hire the individuals necessary. 16 Eleanor Brown, “Assessing the Value of Volunteer Activity”, 1999; http://nvs.sagepub.com/content/28/1/3.full.pdf17 Davis, Rebecca, "Understanding Volunteerism in an Animal Shelter Environment: Improving Volunteer Retention" (2013). College of Professional Studies Professional Projects. Paper 54.

iii. Intake Prevention and Pet Retention Programs It has been argued that the most effective way that an animal shelter can decrease animal neglect within a community is to implement well-functioning intake prevention and pet retention programs. Thousands of animals are abandoned and surrendered every year because owners cannot afford to care for their pet. There are a variety of ways that a city’s ACCF can keep pets in homes and out of shelters (where they are using space, resources, and are at risk for euthanasia). These programs include providing city residents with: • A pet food pantry that assists those with a low or fixed income • Free of charge spay/neuter services • Medical care that would otherwise be unaffordable to an owner

and result in abandonment. The extent to which an animal shelter can offer these necessary services to a community is entirely dependent on their available funds. Many intake prevention and pet retention programs fall outside the scope of “core services” that an animal shelter is responsible for providing under a city contract, however, many city shelters have robust programs in place due to adequate funding provided by the municipality. VI. Conclusion In this study, we have researched the largest cities in the US with a focus on the current situation in Philadelphia and their approach to animal welfare and control. It would be reasonable to analyze Philadelphia’s AWI results and suggest that the Animal Care and Control Team of Philadelphia (ACCT) is extremely efficient. The results do, in fact, support this argument. Considering the large quantity of neglected animals taken in by ACCT, they have been able to demonstrate strong results in several areas. Their adoption rate (34%) is slightly above the average for the cities researched18. Philadelphia also has a strong network of rescue organizations that pull from their PIS. If it were not for this exceptional network, the most significant being the Pennsylvania Animal Welfare Society (PAWS) organization, we would likely see significantly higher euthanasia figures.

http://epublications.marquette.edu/cps_professional/54/ 18 San Diego has the highest rate of adoption (53%) and Chicago the lowest (6%).

Page 6 of 9

What the results of this study do not describe are the decrepit conditions inside of Philadelphia ACCT. As mentioned earlier in this study, the kennel runs installed at Philadelphia’s PIS are ancient and poorly functioning. These kennel runs have not been replaced since their installation in 2002 (and it’s important to remember they were not brand-new even when installed). The importance of this fact cannot be overstated. The well-being of an animal currently sheltered in the ACCT facility heavily relies on the structural integrity of the kennel it is kept in. A well-functioning kennel effectively drains animal fecal matter. A shelter animal spends nearly 100% if it’s time inside of its kennel, eating, sleeping, defecating, and urinating in a space about as a large as a living room closet. When the integrity of that kennel is jeopardized, these animals are susceptible to a wide-variety of disease and infection, which not only makes their life miserable but makes it far more difficult for them to be adopted (adopters tend to want to adopt healthy animals). While this study has not included observations on the condition of other city shelters, it would be difficult to imagine a more desperate situation than the one currently being experienced by ACCT. There are both economic and socioeconomic benefits that can be realized in Philadelphia under the administration of ACCT. However, in order for these benefits to be realized funding must be allocated to improve the programs currently in place and implement those which are not. Having a well-functioning and well-maintained animal control facility is paramount. Where can blame be fairly placed for this crisis? We know that we cannot place it on the countless number of volunteers that spend their time at ACCT working to improve the lives of these animals. Likewise, it would not be fair to place the blame on ACCT’s administrators or Board of Directors. These individuals operate a city’s primary intake shelter with inadequate funding that barely covers the essential costs of running the shelter. The concept of implementing critical programs such as various community-based education campaigns, fund raising initiatives to engage philanthropists, and exceptional medical protocols to treat sick or mistreated animals is near-impossible with only $4.5 million in annual funding. As discussed earlier in this paper, the City of Philadelphia’s response to losing the PSPCA (and its nearly $14 million in annual revenues) as its PIS in 2012 was to transfer

19http://www.phila.gov/Newsletters/MayorsOperatingBudgetInBriefFY2016.pdf

responsibility to a poorly-equipped facility and provide it with a despicable amount of money to operate. This is unacceptable and should lead the citizens of Philadelphia to question many other issues surrounding their community’s well-being. Again, of the top-ten cities in the United States Philadelphia has the 2nd highest rate of crime and poverty and ranks dead-last in unemployment, median household income, and mean home values. It would be safe to say that our city’s inability to properly allocate funding to its PIS goes hand-in-hand with its inability to provide its citizens with a high-quality of well-being. In 2015, the City of Philadelphia reported nearly $6 billion in annual revenues (of which $3.4 billion was procured through taxes). Philadelphia ACCT receives .08% of this annual funding every year. To put it another way, for every $1,000 our city receives they spend 76 cents on a very important city function, saving the lives of neglected animals. This is unacceptable. A common argument in defense of Philadelphia is their lack of available funding. How can our city procure the funding to adequately fund its city animal shelter when it is faced when other budgetary concerns such as education, public safety, and economic development? Every citizen of Philadelphia should invest the time to review the Mayor’s Operating Budget in Brief for FY201619 and see for yourself where your tax dollars are spent. The budget describes a number of “key” investments for FY2016 including: • $3.9 million for the Department of Parks and Recreation to

expand the Summer Jobs program to help with youth unemployment.

• $3.6 million for the Police Department to begin implementing the use of body cameras ($500,000) and for ballistic vests, tasers, and ammunition for additional training exercises ($3.1 million).

• $8.0 million to the Department of Fleet Management (which is already allocated $61 million from the city budget) to replace “old” vehicles.

• $1.1 million to the Commerce Department to fund a program with the purpose of keeping Philadelphian’s from leaving Philadelphia after they graduate college.

This small sample of city investments is not listed to undermine their importance. Rather, they are displayed to demonstrate that there is, in fact, money available that would have a major impact on the well-being of our city’s neglected animal population. The conversation does not need to involve the trade-off between public education and animal welfare. Fiscally speaking, that would be an apple to

Page 7 of 9

oranges comparison. Similarly, Philadelphia ACCT does not need to be included in the discussion about public safety; that department received $1.32 billion from the city this year. In summary, Philadelphia has a long history of caring for its neglected animals. With the city’s primary intake shelter on the verge of collapse, now is the time to revisit this conversation and ask ourselves: Can Philadelphia improve in this area? What effect would this improvement have on the city’s other issues? Can Philadelphia do better? VI. Methodology The data-driven portion of this study will involve the analysis of two sets of figures commonly used to measure the strength of an animal shelter and well-being of a community. For the analysis of shelters, we are taking into consideration the reported annual revenue20, intake figures for canines and felines21, and the number of euthanized canines and felines. This data is charted in Table 1. To analyze the well-being of a city, we considered measures of socioeconomic indication that are normally taken into account when describing the strength and welfare of a community. This data is illustrated in Table 3. In this study, the calculations and figures presented are meant to impartially and accurately reflect the adequacy of a shelter’s funding. The result will ultimately be an Animal Welfare Index (AWI) score. To determine this, we need to first establish the number of neglected animals (i.e. those taken in by a shelter) per resident of the city. This is illustrated as the Person Per Intake (PPI) figure in Table 2. That calculation is divided by 10 for no reason other than to make the resulting calculation easier for the reader to interpret. Next, we determined the portion of the municipal budget allocated to a city’s PIS on a per capita basis by dividing the total PIS revenue by the city’s population. By multiplying a city’s Adjusted PPI by the budgetary allocation per capita we can gain a strong sense of how much funding is provided to its PIS as it relates to the city’s population and shelter intake. This is illustrated in Table 2 as the Adjusted Revenue per Capita figure.

Many shelters determine the adequacy of their funding by simply dividing annual revenues by the city’s population. While this appears to be sound logic, it is faulty. Analyzing the

20 Revenue figures are obtained from either the city budget (for governmental entities) or the most recent Form 990 filed with the IRS (for entities claiming 501(c)(3) status.

Animal Care Centers of New York (ACC) emphasizes the necessity for this alternative calculation. If one were to judge a city’s funding based solely on a per capita basis, it would appear that New York City provides very little funding to their PIS. This would not be a fair or accurate assessment due to the fact that the city’s massive population does not directly correlate with its neglected animal population. Furthermore, there is very little evidence to support that there is any correlation between the size of a city and its neglected animal population.

The final variable taken into consideration when calculating a city’s AWI score is the euthanasia rate of the PIS. The rationale employed is that programs that do not involve euthanizing animals require more funding than procedural euthanasia. As such, this should be taken into consideration when determining the adequacy of funding for a city’s PIS. We multiply the percentage of neglected animals not euthanized by the adjusted revenue per capita figure to arrive at our AWI score. We can assume the cities with the highest AWI scores allocated an adequate amount of funding to their PIS. There are many ways to statistically measure the well-being of a city and this study does not insist on the supremacy of one over another. Our comparison illustrated in Table 4 will produce a Well-Being Index (WBI) score. For each of the aforementioned indicators, we ranked each city on a scale of one to ten; one being most desirable, ten being least. The summation of the rankings provides us with the WBI score with the lowest scoring cities providing the highest quality of well-being to its citizens.

21 Wildlife statistics (normally reported) are not taken into consideration for this study due to their de minimus and widespread nature.

Page 8 of 9

Table 1. Data Pertaining to the Funding, Intake, and Euthanasia for the Ten Largest US Cities.

Table 2. The Calculation of a City’s Animal Welfare Index (AWI)

Table 3. Socioeconomic Data Compiled for the Ten Largest US Cities

City PersonsperIntake PPI%100 Revenue/Capita AdjustedRevenue/Capita Non-Kill% AnimalWelfareIndex(AWI)1 NewYorkCity,NY 292.83 29.28 $1.93 $56.44 86% 48.622 LosAngeles,CA 63.82 6.38 $9.54 $60.88 68% 41.173 Chicago,IL 168.68 16.87 $2.10 $35.36 72% 25.604 Houston,TX 88.56 8.86 $6.11 $54.14 75% 40.815 Philadelphia,PA 66.40 6.64 $2.95 $19.56 78% 15.236 Phoenix,AZ 43.36 4.34 $8.95 $38.80 77% 29.847 SanAntonio,TX 52.09 5.21 $8.53 $44.44 87% 38.648 SanDiego,CA 71.51 7.15 $6.42 $45.91 83% 38.259 Dallas,TX 49.23 4.92 $8.51 $41.90 57% 23.8910 SanJose,CA 68.60 6.86 $7.46 $51.20 82% 41.91

KeyIndicator NYC LA Chicago Houston Philadelphia Phoenix SanAntonio SanDiego Dallas SanJose

City-Data.comCrimeIndex 246.5 265.8 436.5 534.5 508.3 390.9 454.6 211.5 409.3 253.2

PovertyRate 20.7% 30.1% 23.0% 22.4% 26.3% 23.6% 19.6% 15.8% 24.4% 12.8%

HomelessnessperCapita 881 1,037 249 201 383 360 197 627 242 638

CCSULiteracyRanking 20 63 33 60 35 65 70 31 44 39

MeanHomePrice 652,456.00$ 615,283.00$ 276,694.00$ 218,032.00$ 136,800.00$ 214,846.00$ 143,300.00$ 542,854.00$ 240,562.00$ 617,104.00$

UnemploymentRate 8.2% 9.1% 10.4% 6.3% 11.3% 7.4% 6.4% 7.7% 6.4% 8.1%

MedianHouseholdIncome 52,223.00$ 48,466.00$ 47,099.00$ $45,353 36,836.00$ 46,601.00$ 45,399.00$ 63,456.00$ 41,978.00$ 80,977.00$

DidnotGraduate(HS) 19.6% 25.4% 17.8% 22.8% 17.8% 18.8% 17.2% 12.5% 25.0% 17.7%

WithoutHealthInsurance 5% 12% 9% 6% 12% 12% 15% 10% 17% 7%

Z-Score(U.S.News&WorldReport) 5.6 6.0 5.9 6.9 6.1 6.6 6.8 6.9 6.9 7.1

City 2015Pop. ACCFStatus TotalRevenue Intake(D) Intake(C) TotalIntake Kill#(D) Kill#(C) TotalKill %Kill1 NewYorkCity,NY 8,550,405 501(c)(3) 16,480,268$ 9,443 19,756 29,199 951 3,094 4,045 14%2 LosAngeles,CA 3,971,883 MunicipalBranch 37,889,322$ 33,459 28,775 62,234 4,842 15,310 20,152 32%3 Chicago,IL 2,720,546 MunicipalBranch 5,703,307$ 9,158 6,970 16,128 3,306 1,148 4,454 28%4 Houston,TX 2,296,224 501(c)(3) 14,036,665$ 17,033 8,895 25,928 3,982 2,403 6,385 25%5 Philadelphia,PA 1,567,442 501(c)(3) 4,618,025$ 8,670 14,935 23,605 2,108 3,119 5,227 22%6 Phoenix,AZ 1,563,025 MunicipalBranch 13,987,717$ 32,014 4,033 36,047 8,324 23%7 SanAntonio,TX 1,469,845 MunicipalBranch 12,538,983$ 28,215 3,680 13%8 SanDiego,CA 1,394,928 MunicipalBranch 8,956,214$ 11,321 8,187 19,508 1,064 2,192 3,256 17%9 Dallas,TX 1,300,092 MunicipalBranch 11,064,301$ 26,407 11,353 43%

10 SanJose,CA 1,026,908 MunicipalBranch 7,664,063$ 6,114 8,855 14,969 941 1,775 2,716 18%26,407 11,353

8,324 28,215 3,680

Page 9 of 9

Table 4. The Well-Being Index (WBI) Calculation

Table 5.1. Graphical Illustration of Community Well-Being and its Relationship to Shelter Investment

KeyIndicator NYC LA Chicago Houston Philadelphia Phoenix SanAntonio SanDiego Dallas SanJoseCity-Data.comCrimeIndex 2 4 7 10 9 5 8 1 6 3

PovertyRate 4 10 6 5 9 7 3 2 8 1HomelessnessperCapita 9 10 4 2 6 5 1 7 3 9CCSULiteracyRanking 1 8 3 7 4 9 10 2 6 5MeanHomePrice 1 3 5 7 10 8 9 4 6 2

UnemploymentRate 7 8 9 1 10 4 2 5 2 6MedianHouseholdIncome 3 4 5 8 10 6 7 2 9 1

DidnotGraduate(HS) 7 10 4 8 4 6 2 1 9 3WithoutHealthInsurance 1 6 4 2 6 6 9 5 10 3

Z-Score(U.S.News&WorldReport) 10 8 9 2 7 6 5 2 2 1Well-BeingIndex(WBI)Score 45 71 56 52 75 62 56 31 61 34

KeyIndicatorRankings(1-MostFavorableto10-LeastFavorable)&Well-BeingIndex(WBI)Score

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Communi ty Wel l-Being as i t Relates to Shelter Investment

WBI Score Animal Welfare Index Trending (W-Score) Trending (AWI)