The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

-

Upload

ruben-ananias -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

1/11

University

The Weak Suffer What They Must:A Natural Experiment in Thought and Structure

Because of a change at a hospital, we are able to contrast two different structures of leadership in a union worksite. Sincewe had tested a cognitive construct we call "union co nsciousness" before the chang e, the difference in structure provides anatural experiment to determine the consequences of structural change for cognition. We repeated the test after the changeand found a different cognitive structure. We conclude that cognitive structures are not enduring configurations but thatthey change as structures change. This leads to the further conclusion that external structures are powerful determ inants ofpatterns of thought, [experiment, cognition, structure, organized labor, unions, healthcare, culture, theory]

or some the experiment is the defining feature ofscientific research. An investigator deduces fromtheoretical conjecture and empirical findings that an

field (Kuhn 1970; Kuznar 1997).

developed techniques of observing and recording phe-

ger and Erem 1997a, 1997b; Erem and Durren-1997), we had a chance to benefit from such a natu-rkers at a jobsite w ho are organized into

ith supervisors, represent the worker at a sec-this failsty, the steward m ay call a union rep-

resentative whom the local hires to represent mem bers at anumber of worksites. The union reps, as they are called,can represent the member at a third-step hearing with thedepartment manager and the company's vice-president ofhuman resources. If the grievance is not resolved at thethird-step hearing, and if both sides agree, it can be submit-ted to the judgment of an arbitrator whose decision is bind-ing.Thus law and practice have established a set of roles fordealing with workplace problems through union mecha-nisms. Union members do not establish the roles of stew-ard, rep, supervisor, manager, or co-worker, but conducttheir work lives in terms of them and construct various rep -resentations of these categories. Malinowski (1922) differ-entiated between internal views of the people he was tryingto understand as "ethnographic" in distinction to externalconstructions that he called "sociological." Marvin Har-ris's (1999) distinction between the emic and the etic cap-tures another difference that Sandstrom and Sandstrom(1995) discuss at some length. The people w e are trying tounderstand build emic statements from discriminationsthey make. Such statements are wrong if they contradictparticipants' sense of similarity, difference, significance,meaningful ness, or appropriateness. Etic statements de-pend on distinctions upon which a scientific communityagree. They are wrong if empirical evidence fails to sup-port them (H arris 1999). In this exam ple, the law and prac-tice determine the external, or "sociological," perspectiveon union-management relations, and we can ascertain

American AnthtaaalneixtMU 4):78 3-79 3. Copyrighl 2000. American Anthropological Association

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

2/11

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

3/11

DURRENBERGER AND EREM / THE WEAK SUFFER WHA T THEY MUST 7 8 5Table 1. Perfect Union Model.

Supervisor1.00.00.00.00.0

Manager

0.00.00.00.0

Steward

1.00.50.5

UnionRe p

0.50.5

Dif.Line

1.0

o further ways. First, I correlated them to one

itself, members with

roles while those that are not correlated do not. Some of

d An thropac's multidimensional scaling program to de-Those items that are similar cluster together; those

ual representation of similarities and differences that the

(n = 18), a public hosp ital (n = 9), a group of in-rial workers ( n = l l ) , and Rehabilitation Hospital(n = 6) and 1998 (n - 25). To further testhe staff of a different local in the same international un-go (n - 25), and Table 2 shows that their simi-

Table 2. Correlations among Proximity Matrices.Sch96-.41

Staff- .47

.64

Indust-.18- .16

.29

Public-.32

.68.89.14

Staff2-.39

.64

.98

.17

.88

Pure-.39.67

.96.21

.88.96

the emic use of union/nonunion distinctions for orderingterms for the relevant workplace relationships.Having a way of characterizing the m ental picture, inter-nal scheme, or folk model of union-management relationsat different worksites not only allowed me to comparethese constructs at different places, but also allowed me todevelop hypotheses about how the internal models are re-lated to other variables such as level of activism in the un-ion. I expected that more activist stewards would have amodel of social relations more similar to the staff or the"outside" or "prefect" union m odel to be m ore consciousof the union as an organizing principle and show it in theirtriads tests. A similar triads test administered to the stew-ards of the local gathered at their annual convention in1996 indicated that there was no relationship between un-ion activism and union consciousnesswhether or notstewards thought in terms of the "perfect model," one ofthe alternatives (hierarchy or workplace), or some mixtureof the three (Durrenberger 1997).

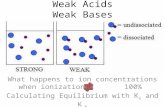

There was a relationship between union consciousnessand the place of the union in the organization of work-sitesa dimension of structure rather than thought or cog-nition. The aggregate similarity matrix for the triads testsof the union local's staff was very close to the externalmodel. I therefore used this as the measure of union con-sciousness. To the extent that a group of mem bers showeda similar cognitive pattern, I concluded that they exhibitedunion consciousness. Members at only two worksites ex-hibit union consciousness. One was a public hospital(Pearsons r = .89), where for various reasons the union isvery strong and significant (Durrenberger 1997). The otherwas Rehabilitation Hospital (r = .64). I concluded that thiswas because of the small size of the membership and thestrength of the chief steward who had been in office forseveral decades and cultivated a vast network of relation-ships of mutual obligation, not only among members butwith management. Furthermore, just before I administeredthe first triads tests, there had been a union victory that allof the members had celebrated. I argued that without timedepth it was not possible to know whether such cognitiveconfigurations were stable through time or whether theyrespond to such episodes as a victory or a defeat for the un-ion at a site (Durrenberger 1997). As show n in the m ultidi-mensional scaling diagram in Figures 2 and 3, the one dif-ference between Rehabilitation Hospital (Figure 2) and thepublic hospital (Figure 3) was that the members at Reha-bilitation Hospital departed from the "union model" toplace their steward hierarchically above rather than belowthe rep, so their steward w as on a par with the ma nager andthe rep with the supervisor. Another, which represents therelative power of the union in the two workplaces, is theplacement of the public hospital's stewards and rep at ahigher level in the hierarchy than supervisors or managers(Durren berger 1997). The reversal of the stew ard/rep

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

4/11

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 101, No. 4 DECEMBER 1999

DLWORKER

SLWORKERSUPERVISOR

MANAGER

REPSTEWARD

DL WORKER

SLWORK

STEWARD

UNION REP

Figure 2. (top) Rehabilitation Hospital 1996.Figure 3. (bottom) Public Hospital.

at Rehabilitation Hospital was an accurate re-of the chief steward's long association and devel-ith the management of the hosp ital. At the

in fact had more power than the rep, thoughreinforce it by putting the authority of the lo-

ne nor the history of recent v ictories or intri-of relations that connected the leadership of

of Rehabilitation Hospital. I concluded (Durren-1997) that union consciousness seemed to be relatedof structurerealities of power and organiza-perhaps history or recent events.

is usually where the story stops. We observe andIf we are quantitative in our tastes, if wethe patterns and m ake them accessible to oth-

to observe and test, we translate some of these intoIf we are em pirically oriented, we test hypothe-

andbase other speculations on theoretical assertionsof the past. The association of thethe structure seems plausible for

want of any convincing measure of structure that would bemore than a poor proxy. But we could argue, I suppose,that the cultures of worksites are sufficiently different tocause different structures. Just because it does not seemplausible to me does not mean that it might to someoneelse.However, w hen the chief steward at Rehabilitation H os-pital retired just before the unit negotiated a new contract,Suzan and I were presented with the possibility of at least aquasi-experimental design. We had the triads tests from1996, and now in 1998 we could administer them again, af-ter a significant structural change, to detect whether thepatterns of thought had changed with the change of struc-ture. While this was a change of personne l within the exist-ing collective bargaining arrangements, though the unionstructure remained intact with stewards and reps and law,there were changes of relations of power in the changingnetworks of the workplace. As this steward withdrew fromthe workplace, her well-developed relationships of mutualobligation with management and workers alike disap-peared. This shift brought together what Alford (1998)calls multivariate, historical, and ethnographic approachesto bear on a single theoretical question that is at the sametime a practical issuethe relationship between con-sciousness or patterns of thought and changing realities ofpow er and organization (structure) at a single worksite.Theoretical Backgroun ds

From advertising to education there are modern institu-tional structures dedicated to the proposition that the wayto change pe ople's actions is to chang e their minds, a pro-posal that rests on the assumption that thought determinesaction. When Jean Lave (1988), attempting to understandhow people learn and use that most cerebral of cognitiveskills (mathematics), challenged transference theorythenotion that we can isolate abstract properties of systemsand communicate them to others via symbolsshe advo-cated expanding our understanding of cognition fromsomething that happens in the mind to a process thatstretches over the environment as well as time into past ex-periences and future expectations. In doing so, she offereda new definition to a movem ent O rtner (1984) detected inthe attempts to synthesize and sort out anthropologicaltheorizing since the 1960s, a trend Ortner tentatively called"practice theory."

Some who called themselves cognitive anthropologists,before boring themselves to death, as Keesing (1972)quipped in a pre-mature death knell (Durrenberger 1982),described well-structured patterns of thought they under-stood by talking to people. In a precursor of the now fash-ionable "linguistic turn" (P&lsson 1995), some (Black1969) even argued that because cultures were things of themind embodied in language, anthropologists had only totalk to people to understand their cultures.

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

5/11

DURRENBERGER AND EREM / THE WEAK SUFFER WHA T THEY MUST 7 8 7

itive anthropologists questioned the salience

s in Thailand and concludes that "the process of cre-

by hearing about them but by doing them. A ctions, he

economic, political, and cultural rela-

o thought as m aterialists would have it?

t all out because it is too complex. At best w e can pro-ulate it in another mode. Replication of reality needs

hurricane forecasters watching butterflies to detect howat of their individual wings will impact El Nino .

transference of patterns, is not the answer. Thehere is that we are trying to change yourby just that means! On the other hand, we are contentone 's

t.are of more than theoretical or

because it was those outcomes that were important in try-ing to bring about the changes she d esired.The Story

When Delia retired from Rehabilitation Hospital Rehabafter 30 years as chief steward, I knew the union wouldnever be the same. She warned me she was retiring, but ittook a year or more for her to finally leave, so after awhileher complaints of the pain in her wrists from dishing outfood for three decades didn't register with me as poign-antly and I thought she would stay at least as long as Iwould.But finally Delia announced the date she would leave.She assured me that the gangly young jokester who'd just"become un ion" a year before w ould make a good steward.Bernard adored Delia, that was clear, but so did everyoneelse. She was the center of the hospital, like a grand motheris the center of a huge family, so it was hard to believe thistall, thin, fun-loving but inattentive charac ter could ever fillher shoes. I knew Delia 's judgm ent w as sound, so I trustedshe'd teach him everything he needed to know.A year earlier, the other veteran steward, Marie, fromhousekeeping, retired. Her retirement wasn't as noticeablebecause D elia was the true matron, but it left an entire de-partment without a steward. Between Marie's retirementand Delia's was Monica's promotion. Monica was theyoung, articulate, and fastidious steward from the nursingdepartment. About three m onths after running a successfulunion protest against the hospital, she was prom oted out ofthe union into a management position as a scheduleraposition that, because it is considered management, is bylaw not in the bargaining unit. Within a year she had ababy. When she tried to return to work, RehabilitationHospital " could n't find" a position for her. Around the hos-pital the workers would say they knew R ehabilitation H os-pital did her wrong after the way she helped run that boy-cott last year, but it was her fault for getting out of theunion.So Delia was the last and most effective steward to leavethe shop, and that left me with a vacuum. Bernard tookover the kitchen, and at a membership meeting a quiet m annamed Greg volunteered to take on housekeeping. Nostewards came forward from nursing. Greg and Bernardspent a Saturday morning to com e to a stewards' training Iheld at the union office for healthcare workers. They gaveup another Saturday to attend the 1997 annual stewards'conference as well. (Well, Bernard tried to attend, but afterhe picked up Delia in a snowstorm his car broke down onthe expressway. They were both stranded for hours.) Gregcalled at least once a week to update me on problems, butoften indicated he "had it under control." Bernard, yo ungerand cockier, and that much less secure, never called. W henI'd hear problems from other members, I'd ask him aboutthem, but he always assured me "h e had taken care of it."

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

6/11

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLO GIST VO L. 101, No. 4 DECEMBER 1999

M ore than a year passed before I realized som ething se-

from the bargaining unit. The hospital w as eliminatingnd was careful not to target the union. Insteadlayoff, the members votedwith Delia's

the patient count reached an average of 77 for 90ould go up soon w ith the open-

Delia retired, and six months later Rehabilitation Hospi-

their hours at 7 asll! The m embers were enraged, and so was 1.1 made fu-

e to ever agree to such a thing, since taking theif w e'd thought they w ere going to hire new staff any

Meanwhile, we had just wrapped up six months of bar-

and the contract was signed.But every time I went to the hospital, members ap-e with the same question: "When are we gonna

nagem ent for what it had done, but within a few monthst was not manageme nt who w as get-of it.To test my theory, I told the stewards w e needed to run a

copies. Then I gave them a week to get eve-to sign it. A w eek later, the petition w as nowhere toI asked the stewards, and they said they passed it

Now I knew we w ere in trouble, but the stewards neededthat I knew before I could approach them with the

couldn't get a single person to go with them. This was thehottest topic of the year, and not a single person was will-ing to follow the union steward on it. Finally, I started ask-ing the most honest questions and getting some answers.'T he y say the union is weak," said one person. "T he uniongave our hours away and can't get them bac k."I realized I had a serious leadership crisis. More often

than not, members started coming up to me with theirgrievances about a nasty boss or denied vacation. I re-ceived phone calls from members I'd never heard fromasking if managem ent had the right to do this or that. I'd re-fer them to the stewards, but they would say the stewarddidn't know. Worse, they'd go away without talking to thesteward, and without telling me, unsatisfied and believingthe union was weak and ineffective to help with theirworkplace problems.In February 1998, after negotiating a new contract, weheld the contract ratification meeting where I describedwhat we'd negotiated, and we distributed the same triadstest Paul had done more than a year before, when Deliawas still there. Members voted, then filled out the triadstests, and then received their contracts. The contract wasratified. With bargaining behind me, I could focus on theinternal problems more carefully.I sat down with the two stewards. I said, 'T hi s isn't fairto you and it's bad for the union. These folks wo n't followyou and you're beating your heads against the wall." Bothmen nodded enthusiastically at that assessment. I agreed tohold steward elections, define the job of steward, and rein-force that once members vote for a steward they have totrust and follow that person.The word went out through the kitchen that Bernard wasup for election, and the older workers looked concerned."Why?" they asked me. "Because you're not followinghim, and the union can't afford that. If you're going to fol-low him, then re-elect him; if not, then vote for somebodyelse. But w e've got fights to fight, and we c an't be screw-ing around." By the end of that week, Bernard called meand announced that he'd taken six workers from thekitchen with him to the human resources department anddemanded to meet with the director. Th ey'd met for almost

a half hour. I congratulated him loudly. Later that day I re-ceived a phone call from management requesting that onlyone person meet w ith them. I knew w e'd made a point. Thenext week, the mem bers re-elected him steward.Housekeeping didn't turn out the same way. I askedmembers what they thought good qualities in a stewardwere. They listed them: "They ought to speak up for peo-ple. They ought to study up on the laws and the contract.They ought to never be cutting their own deals, but lookingout for everybody." So I relisted them"so they shoulddefend their co-workers, go to trainings, and lead." They

agreed. Then I reminded the members that if the stewardholds up his end of the deal, they have to hold up theirs'

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

7/11

DURRENBERGER AND EREM / THE WEAK SUFFER WHA T THEY MUST 7 8 9

ith training.

-time hours. That wou ld be the

Triads Revisitedthenew contract shows a cognitive pattern quite dif-om the first one m ore than a year before (r = -.41)

= .64), the second is not (r = -.47).erent people responded to thebut the proportions of people in different depart-e about the same, and at least som e of the same in-there are no factions, so differential representation ofl views could not be a factor.scaling representations of the two2 and 4 show there is a shift away from a

his hierarchy; the superiority of the steward to

DLWORKER

STEWARDREP

SUPERVISOR

The ratification vote was strong, so the shift in the triadscannot indicate alienation because of the new contract. Theshift must be related to what appeared to Suzan to be aleadership crisis, the change in the structure of the unit oc-casioned by the withdrawal of all of the experienced stew-ards and the chief steward and the disappearance of thosenetworks of relationships from the unit. The cognitivemodels reflected the changing realities of power and or-ganizationstructurein the worksite. The fact that thecognitive model changes to mark reorganization of thestructure leads to the conclusion that structure causes cog-nition, not the other way around.Details

Here we report in more depth the statistics of this exer-cise. Those w ho find such material boring will perhaps for-give the exercise and skip to the next m ore qualitative sec-tion on structure, agency, and class so that our colleagueswith more developed senses of methodological aestheticswill not be neglected.A comparison of the proximity matrices of differentworksites shows just how they differ. Table 3 shows theproximity matrix for a group of industrial work ers. Table 4shows the proximity matrix for the public hospital, whichwas considered a model of strong organization. Table 5shows the proximity matrix for the staff. The "perfect"model and staff model show a 0 or near 0 similarity be-tween union reps and stewards on the one hand and super-visors and managers on the other, while the industrialmodel shows a stronger similarity. The "perfect" and staffmodel show a near 0 similarity of members with supervi-sors and managers but the industrial model shows signifi-cantly stronger relations. The "perfect" and staff modelsshow a similarity of about .5 for stewards and reps on theone hand and mem bers on the other. The industrial modelshows a m uch weaker similarity. All together, these 12 re-lationships indicate that industrial members see themselvesas closer to management and farther from union officersthan the "union m odel" would. The m ultidimensional rep-resentation of these relationships shows the contrast amongindustrial members and staff as Figures 5 and 6 indicate.These representations suggest that while staff see a cleardemarcation between union and management and a hierar-chy much like the outside model, the industrial members

Table 3. Industrial Members.

Figure 4. Rehabilitation Hospital 1998.

ManagerStewardUnion RepDif. LineSame Line

Supervisor

.73

.23

.09.16

.25

Manager

.18

.25.25

.20

Steward

.89.18

.27

UnionRep

.27

.18

Dif.Line

.82

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

8/11

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST VOL. 101, No. 4 DECEMBER 1999

Table 4. Public Hospital Members.Supervisor Manag er Steward Union Dif.

Rep Line

RepLine

.93.10

.18

.10.05

.08

.25

.08.08.88.35.48 .28.30 .90

agem ent and union officers as being equally differ-and more powerful than mem bers.The contrast between Rehabilitation Hospital in 1996

and 1998 (Figure 4) shows the structural changeThe corresponding 1996 andmity matrices illustrated inTables 6 and 7 show

as members see stewards and reps as closer toand supervisors in 1998 than in 1996, see them-

o m anagers but somew hat less close to su-and see themselves as less similar to reps andIn these respects, the 1998 proximity matrix forone.To what extent do these figures and tables representof thought? This has been an issue sincellace raised it (1961). Romney, W eller, and Batchelder

the theory and mathematics for computingon cultural domains, and Borgartiit in A nthropac. H ere, the purpose

is only toassess the agreementThe procedure computes a factorof the chance-adjusted measures of agreementIf the first factor is less than three

as great as the second, there is noconsensus. Table 8the ratio of the first to the second factor for eachand the number of respondents. It is clear that thereat each site toconsider the proxim-

Given that there is consensus among respondents, toare the samples of respondents representativethe whole group? Sampling techniques were neither

nor very pure. The exigencies of shifts,a wide area, dubious quality of mem-the random sampling that we desired

Table 5. Staff.Supervisor Manager S teward Union

RepDif.Line

RepLine

.83.04

.00

.04

.08

.06.07

.06.03

.68

.64

.73.49.44

REP/STEWARDS MAN/SUPER

WORKERS

Figure 5. Industrial Members.

and attempted hopelessly quixotic. Todo the work, we hadto rely onother techniques, chiefly opportunistic sampling.Some of the samples represent almost the entire popula-tion, and for those sampling is not problematic. Virtuallythe entire staff of the local responded, so that is not an is-sue. Almost all of the nonsupport staff of the second localresponded , and that included virtually all of the reps. Reha-bilitation Hospital has about 60 members (64 in 1996, butthe number varies as Suzan's narrative in this paper indi-cates); thefirstsample of 6 is thus about 10%; the second isnearly half, 42%, and represents all departments as doesthe first sample. W hile these are neither random nor strati-fied samples, they are fairly representative of the member-ship. The industrial sam ple is from a random sample list offour industrial sites Durrenberger drew from the member-ship list. This represents about 1 % of the total industrialme mbership of the local. The public hospital sample is par-tially from a random sample List I drew from the member-ship list and partially an opportunistic sample of its 674service employees and 79 technicians (753 total), about a1 % sample. The samples of the staffs and RehabilitationHospital members are probably representative, but there

SUPERVISOR

MANAGER

WORKERS

STEWARD

REP

.94 Figure 6. Staff.

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

9/11

DURRENBERGER AND EREM / THE WEAK SUFFER WHA T THEY MUST 7 91

Table 6. Rehabilitation Hospital 1996. Table 8. Sites, Numbers of Respondents, and Ratio of First andSecond Factors in Consensus Analysis.Supervisor

.81

.13

.10

.28

.31

Manager

.06.07.22.26

Steward

.60

.31.26

UnionRep

.17.26

Dif.Line

.88

, though the sam pling was m ore purely random.Stru ctu re, Agency, and Class

Alford (1998) po ints out the problems of the mu ltivari-oach in understanding historical phenom ena de-

resources (Fried 1967), agency and structure may haveerent positions in different classes because access to re-hence c lass position, rests on differential power, ae seemsbe dual awareness of both structure and agency, w hereas

ructures is less a cultural convention than a recognitionthe reality of pow erlessne ss (Griffith 1995; HackenbergHunt 1996; Newman 1988,1993; Rubin 1992).The relationship has never been stated more clearly thanhe words Thucydides put into the mouths of the Athe-

and of men we kno w, that by a necessary law of their

Table 7. Rehabilitation Hospital 1998.Supervisor

.86

.32

.28

.17.21

Manager

.22

.23

.19.28

Steward

.70

.19.18

UnionRep

.22.22

Dif.Line

.84

Site N RatioRehab96Rehab98StaffStaff2PublicIndustrial

6251825911

4.54.05.85.210.611.2

did not make this law, but found it "and shall leave it to ex-ist for ever after us" (Crawley n.d.: 361-362). The demo-cratic Athenians then besieged the place and finally, afterthe Melians surrendered, killed all of the men and sold thewomen and children into slavery (Crawley n.d..-365). TheAthenians' observations are as valid for modem social or-ders as for ancient ones.The chief goal of the union movement in industrial so-cial orders is to redress the structural imbalance and givesome sense of agency to those who provide labor but donot necessarily control the conditions for its use. It doesthis by attempting to develop collective power based onstructural principals other than wealth. The intentions ofthe powerful are more conseq uential than those of the un-powerful. Thus by the actions of the powerful do their in-tentions become structures that shape the cognition of thepowerless. Cognition and agency may determine structurefor some classes while for others structure may determine

cognition; the causal arrows m ay be functions of class po-sition or power rather than being constant across the w holesocial order. Thus even the question of causal relations be-tween structure and cognition is not a constant but variesby class. This is one theoretically important reason that an-thropologists should not perpetuate the American folkmodel of the classless society but should explore the struc-tural, cultural, and practical dimensions and consequencesof stratification in our own society (see the works in For-man 1995) and other social orders ancient and m odern.

ConclusionWe have offered an analysis of some triads tests and astory. The story explains the results of the testsit ex-plains the ethnographic data. When people saw unionstewards as powerful and effective, they stressed unionmembership and the power of union officers comparedwith management personnelthey were conscious of theirunion as efficacious. A little over a year later, following theloss of all the seasoned stewards and their networks of mu-tual obligation with management, a source of power andinfluence, after a series of ineffective interventions to meetmanagement imprecations, the same triads test shows thatworkers see themselves closer to a more powerful

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

10/11

AMERICAN ANTHROPO LOGIST VO L. 101, No. 4 DECEMBER 1999

which we can base statements about the relation-

than the dimensions of contrast amo ng sets

ill, the skill, and the modesty required to bring our

hope we have suggested that the world is more com-

ently related and differentially efficacous.

Epiloguetakes up the story again.

iddle of the summ er of 1998 we had everyone

gh turnover among manage-to create new structures. If management elects not to

what happens at their jobs as they becom e m ore or-

NoteWe thank Tom Balanoff, President of

Hart, President of SEIU Local 1, both of Chicago, for theirsupport during various phases of this project. We also thankthe staff, officers, and members of these two locals for theirassistance. We thank Robert W. Sussman, editor of the Ameri-can Anthropologist, for his editorial suggestions and the fouranonymous readers whose reviews helped us improve thepaper.

References CitedAlford, Robert R .1998 The Craft of Inquiry: Theories, Methods, Evidence. New

York: Oxford University Press.Bernard, H. Russell1988 Research Methods in Cultural Anthropology. NewburyPark, CA: Sage.Black, Mary B.1969 Eliciting Folk Taxonom y in Ojibwa. In Cognitive An-thropology . Stephen Tylor, ed. Pp . 165-189. New York: Holt,Rinehart and Win ston.Borgatti, Stephen P.1996a Anthropac 4.0. Natick, MA : Analytic Technologies.1996b Anthropac 4.0 Methods Guide. Natick, MA : AnalyticTechnologies.Crawley, Richard, trans.N.d. Thucyd ides: The Peloponnesian War. New York: Dol-phin Books.Durrenberger, E . Paul1982 An Analysis of Lisu Symbolism, Economics, and Cog-nition. Pacific Viewpoint 23:12 7-14 5.1996 Gulf Coast Sounding s: People and Policy in the Missis-sippi Shrimp Industry. Law rence: University Press of Kansas.1997 That' 11 Teach Yo u: Cognition and Practice in a ChicagoUnion Local. Human Organization 56(4):388-392.Durrenberger, E. Paul, and Suzan Erem1997a Getting a Raise: Organizing Workers in an Industrializ-ing Hospital. Journal of Anthropological Research 53(1):3146 .

1997b The Dance of Power: Ritual and Agency among Un-ionized American Health Care Workers. American Anthro-pologist 99( 3):4 89^ 95.Durrenberger, E. Paul, and John M orrison1979 Com ments on Bro wn 's Ethnoscience. American Eth-nologist 6(2):408-40 9.Erem, Suzan, and E. Paul Durrenberger1997 The Way I See It: Perspectives on the Labor M ovementfrom the People in It. Anthropology and Humanism22(2): 159-169.Forman, Shepard, ed.

1995 Diagnosing America: Anthropology and Public En-gagement. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.Fried, Morton H.1967 The Evolution of Political Society. New York: RandomHouse.Gatewood, John B.

1985 Actions Speak Louder than W ords. In Directions in Cog-nitive Anthropology. Janet W. D. Daugherty, ed. Pp.199-21 9. Urbana: U niversity of Illinois Press.

-

7/27/2019 The Weak Suffer What They Must-A Natural Experimentl in Thought and Struture

11/11

DURRENBERGER AND EREM / THE WEAK SUFFER WHAT THEY MUST 7 9 3

1995 Hay Trabajo: Poultry Processing, Rural Industrializa-tion, and the Latinization of Low-Wage Labor. In Any WayYou Cut It: Meat Processing and Small-Town America. Don-ald D. Stull, Michael J. Broadway, and David G riffith, eds. Pp.129-151. Law rence: U niversity Press of Kansas.1995 Conc lusion: Joe Hill Died for Your Sins: Empowering

Minority W orkers in the New Industrial Labor Force. In AnyWay You Cut It: Meat Processing and Sm all-Town Am erica.Donald D . Stull, Michael J. Broadway, and D avid Griffith,eds.Pp . 23 1-264 . Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.1999 Theories of Culture in Postmodern Tim es. Walnut

Creek, CA : AltaMira Press.Matthew O .1996 The Individual, Society, or Both: A Com parison ofBlack, Latino, and White Beliefs about the Causes of Poverty.Social Forces 75(1 ):293-322.

1972 Paradigms Lost: The New Ethnography and the NewLinguistics. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology (Journalof Anthropological Research) 28 (4):299-332.Thom as1970 The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Second edition.Chicago: University of Chicago P ress., Lawrence A .1997 Reclaiming a Scientific Anthropology. Walnut Creek,CA: AltaMira.1988 Cognition in Practice. New York: Cam bridge UniversityPress.1997 An Introduction to Theory in Anthropology. New York:Cambridge University Press.1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Reprint. ProspectHeights, IL: Waveland Press.1988 Falling from Grace: The Experience of Downward Mo-bility in the American Middle Class. New York: Free Press.1993 Declining Fortunes: The Withering of the AmericanDream. New York: Basic Books.

Ortner, Sherry B.1984 Theory in Anthropology Since the Sixties. Com parativeStudy of Society and History 26(1): 126-166.Palsson, Gisli1994 Enskilment at Sea. Man 29 (4):901-927.1995 The Textual Life of Savants: Ethnography, Iceland, andthe Linguistic Turn. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academ icPublishers.Romney, A. Kimball1999 Culture Consensus as a Statistical Mo del. Current An-thropology 40 (supplement)^ 103-s 115.Romney, A . Kimball, John P. Boyd, Carmella C. Moore,William H . Batchelder, and Timothy J. Brazill1996a Culture as Shared Cognitive Representations. Proceed-ings of the National Academy of Science 93:4 699 -470 5.Rom ney, A. Kimball, and Carmella Moore1998 Toward a Theory of Culture as Shared Cognitive Struc-tures. Ethos 26(3):314-337.Romney , A. Kimball, Carmella M oore, and Craig D . Rush1996b Cultural Universals: Measu ring the Semantic Structure

of Emotion Terms English and Japanese. Proceedings of theNational Academy of Science 94:548 9-549 4.Romney, A . Kimball, Susan C . Weller, and William H.Batchelder1986 Culture as Consensus: A Theory of Culture and Inform-ant Accuracy. American Anthropologist 88(2):31 3-338 .Rubin, Lillian B .1992 Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working-Class Family. NewYork: Basic Books.Sandstrom, Alan R., and Pamela Effrein Sandstrom1995 The Use and Misuse of Anthropological Methods in Li-brary and Information Science Research. Library Quarterly65(2): 161-199.Van Esterik, Penny1978 Comm ent on Brown et al. American Ethnologist 5(2):404-405.Wallace, Anthony F. C.1961 Culture and Personality. New York: Random House.Wang, Zhusheng1997 The Jingpo Kachin of the Yunnan P lateau. Tempe, Ari-zona: Program for Southeast Asian Studies Monograph Seriesof Arizona State University.Weller, Susan C , and A. Kimball Romney1988 Systematic Data Collection. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.