The Value of Intestinal Myotomy and Myectomy in Endorectal Pull ...

-

Upload

truongkhanh -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

2

Transcript of The Value of Intestinal Myotomy and Myectomy in Endorectal Pull ...

The Value of Intestinal Myotomy and Myectomy in

Improving the Reservoir Capacity of theEndorectal Pull-through

RICHARD H. TURNAGE, M.D., ARNOLD G. CORAN, M.D., and ROBERT A. DRONGOWSKI, M.A.

In laboratory models of massive small bowel resection and col-ectomy, intestinal myotomy has been shown to decrease stoolfrequency and malabsorption. Using physiologic and anatomicparameters of gastrointestinal function, we assessed the abilityof three types of ileal myotomies to improve outcome after totalabdominal colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and endorectal pull-through (ERPT) without an enteric reservoir. Twenty puppiesunderwent ERPT. These dogs were randomly assigned to threeexperimental groups or a control group consisting of animalswithout a myotomy. The myotomies were performed by excisingthe serosa and muscularis propria of the ileal wall in three dif-ferent patterns. There was no difference between any of thegroups with respect to general health, postoperative weight gain,stool frequency, intestinal transit time, water absorption, elec-trolyte absorption, barium enemas, neorectal capacity and di-mensions, and histology.

I N 1947 RAVITCH AND SABISTON described the tech-nique of mucosal proctectomy and endorectal ilealpull-through (ERPT) in dogs' and later in nine pa-

tients with familial polyposis coli and ulcerative colititis.2'3This procedure initially fell into disrepute but was rein-troduced by Martin in 19774 and since then has gainedincreasing acceptance as a reliable and safe alternative toa permanent Brooke ileostomy or Koch pouch in thesepatients.5'6 Significantly increased stool frequency, es-pecially in the first postoperative months, prompted manyinvestigators to construct ileal reservoirs to improve thisfrequency and urgency.7-9 The results with these reservoirshas generally been good; however they are associated witha number of disadvantages, including the use of 15 to 45cm of healthy bowel, more technically demanding oper-ations, and greater morbidity associated with long entericsuture lines. These factors have encouraged us to continueto use a straight pull-through without a reservoir at thecost of a slightly greater early stool frequency.'0 Recent

From the Section of Pediatric Surgery, University ofMichigan Medical School and the C. S. Mott

Childrens' Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan

studies from our laboratory have confirmed no differencein multiple physiologic parameters of gastrointestinalfunction between the straight pull-through and the pull-through with various reservoirs in dogs."We hypothesized that an intestinal myotomy might de-

crease early postoperative diarrhea while maintaining thesimplicity of the straight ERPT. This has been successfulin controlling diarrhea and malabsorption in laboratorymodels after massive small bowel resection,'2-'5 total ab-dominal colectomy and ileoproctostomy,'6 and total ab-dominal colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ERPT.'7We tested this hypothesis in a canine model by usingphysiologic and anatomic parameters of gastrointestinalfunction, including general health, weight gain, stool fre-quency, intestinal transit time, water absorption, electro-lyte absorption, barium enemas, neorectal capacity anddimensions, and histopathologic examination.

Materials and Methods

Twenty conditioned puppies (4 months old) were ran-domly assigned to each of four groups. The dogs under-went a total abdominal colectomy and mucosal proctec-tomy with endorectal pull-through in a manner previouslydescribed." Antibiotics (250 mg ampicillin and 10 mgkanamycin) were given by mouth every 6 hours for 24hours before the procedure. Immediately before the pro-cedure the animals underwent mechanical bowel prepa-ration with soap water followedby betadine enemas untilthe effluent was clear. Chloramphenicol (10 mg subcu-taneously) was given before operation and the animalswere anesthetized with xylazine (2.5 mg/kg subcutane-ously) and sodium pentobarbitol (20 mg/kg intrave-

463

Address reprints requests to Arnold G. Coran, M.D., Section of Pe-diatric Surgery, C. S. Mott Children's Hospital, Room F7516, Ann Arbor,MI 48109-0245.

Accepted for publication September 13, 1989.

TURNAGE, CORAN, AND DRONGOWSKI

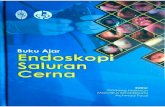

nously). The animals were endotracheally intubated andmechanically ventilated during the procedure. Understerile conditions a total abdominal colectomy was per-formed. The colectomy was carried down to the peritonealreflection of the rectum and a mucosal proctectomy wasextended to the dentate line. The rectal mucosectomy wasperformed through the laparotomy incision and the mu-cosa was everted through the anus. The distal ileum wasanastomosed to the dentate line of the anus with absorb-able sutures. No drains were placed.The experimental groups are outlined in Figure 1. My-

otomies were performed by removing the serosa andmuscularis propria of the ileal walls, thus allowing thesubmucosa and mucosa to pout through. Circular my-otomies were constructed by the excision of 1-cm stripsof the longitudinal and circular muscle and the serosa.These myotomies were placed 1 cm apart with the mostdistal myotomy 1 cm from the ileoanal anastamosis. Theyextended along 75% of the circumference of the bowelwall. The longitudinal myotomies were placed at 90, 180,and 270 degree angles with respect to the mesenteric sur-face of the ileum and were 5 cm long and 1 cm wide. Thethird experimental group (window myectomy) underwentremoval of the serosa and muscularis propria from 180degrees of the circumference of the bowel wall extendingfrom 90 degrees to 270 degrees of the wall with respectto the mesenteric surface. This myectomy was 5 cm long.In each case the integrity of the ileal wall was ensuredbefore closure and the myotomy or myectomy was totallycontained within the rectal muscular cuff.The general health, stool consistency, perineal excoria-

tion, hydration status, and body weight were assessed be-fore operation and weekly after the operation. Stool fre-quency, gastrointestinal transit times, water absorption,and electrolyte absorption were also analyzed at monthlyintervals. Barium enemas were performed on all animals6 months after the operation. The volume of the neorec-tum was directly measured 6 months after operation. Thegross and microscopic features of the pull-through ter-minal ileum were studied.The intestinal transit time was defined as that time re-

quired for a bolus of food to pass from the mouth of the

Window Longitudinal

dog through the anus. The animals were fed a can of reg-ular dog food containing 10 g of charcoal per can. Thedogs were observed until the charcoal was noted to passin the stool.The stool frequency was measured by direct counting

of bowel movements during an 8-hour period.Deuterium oxide (D20) absorption has been found to

be a good reference for gastrointestinal water absorp-tion.'8" 9 D20 (2.5 mL/kg) was placed into the stomachof each animal with an orogastric tube. Blood sampleswere drawn for D20 analysis before and 3 hours after theadministration of the D20."l After double-vacuum, freezedistillation of the serum to remove solutes and impurities,the serum distillates were analyzed for D20 concentrationby the falling drop method and mass spectroscopy.20The following formula was used to calculate percentage

of D20 absorption:

[D'Opost- (D2Os)pre] X 0.7 X wt(kg)- ~~~~~~~X100[D20]administered

where (D2O0)p,,o and (D2Os)p,, are serum concentrationsof D20 after and before the administration of D20 (totalbody water), and D20 administered is the amount of D20given by mouth, 0.7 X weight in kilograms is the approx-imate volume for distribution of D20 (total body water),and D20 administered is the amount of D20 given bymouth.Sodium bromide absorption parallels the gastrointes-

tinal absorption of sodium chloride.21-25 Five per centsodium bromide (4 mL/kg) was administered into thestomachs of the dogs through an orogastric tube. Bloodsamples were obtained before and 3 hours after the inges-tion ofthe sodium bromide. Serum bromide was analyzedby a spectophotometric technique.26 The percentage ab-sorption was calculated using the following formula:

[(Brs)post- (Brs)pre] X 0.35 X wt(kg) X 100[Br]administered

where [Brs]post and the [Brs]pre are serum concentration ofbromide before and after oral administration, 0.35X weight in kilograms is the volume ofdistribution of Br,and [Br]administered is that amount given by mouth.

Circular

-7

FIG. 1. Illustration of thethree intestinal myotomies.

I44I b

464 Ann. Surg. * April 1990

CAPACITY OF THE ENDORECTAL PULL-THROUGH

Barium enemas with fluoroscopy were obtained 6months after the operation. The neorectal pouch wasmeasured at the second coccygeal body in each dog. Thiscorresponded to the top of the rectal cuff as marked bymetal clips at operation. Anteroposterior and transversediameters were measured at this point. The ileum andneorectum were inspected for evidence of stricture, ob-struction, leak, fistula, and proximal ileal dilatation.

Six months after ERPT all dogs underwent laparotomywith inspection of the pelvis for evidence of abscess anddilation of the neorectum or ileum proximal to thesphincter. The endorectal pouch was dissected free fromsurrounding tissues, leaving the rectal muscular coat withthe ileum. The pulled-through ileum was then washedclean of feces and the anus was closed with a purse-stringsuture. The ileum was divided 5 cm above the top of theendorectal cuff. This was then distended with normal sa-line at 30 cm of water pressure and pouch capacity wasmeasured. The distended pouch was then fixed with for-malin (10% solution). 16

Histologic evaluation of the neorectum, rectal mus-culature, and anus was performed using light microscopy.Inflammation, pouchitis, and strictures were looked forspecifically. The integrity of the muscular layers of thebowel wall was also noted.

Analysis of variance was used to examine the meansof the experimental groups for statistical significance,which was assigned at the 95% confidence level.

Results

There were no consistent differences in the generalcondition, perineal excoriation, and stool consistencyamong any of the experimental groups. In each case thestool became semi-solid within 1 month ofthe operation.No animal became dehydrated after operation secondaryto diarrhea. Defecation behavior was abnormal in all an-imals initially; however, within 2 months after operationdefecation became normal in all but two dogs.

All dogs experienced perineal excoriation early in thepostoperative course. As the stool became semi-solid this

30

U.

0

a

-a

465

---- circular---e- longitudinal

* window* straight

0 1 0 20 30time (wks)

FIG. 3. Postoperative stool frequency after colectomy and ERPT.

resolved in all but four dogs. These dogs continued tohave perineal exoriation even 6 months after operation.

All dogs experienced consistent weight gain after aninitial decline immediately after operation (Fig. 2). By 1month after operation the average weight gain was 8%.This increased to 16% per month between 3 and 6 months.There were no statistically significant differences in weightgain between the myotomy groups and the straight pull-though group or within the myotomy groups themselves.

Stool frequencies rose after operation to a mean of 17stools per 8-hour period (Fig. 3). The frequency stabilizedwithin 1 month after operation. Although a general de-crease in the stool frequency was noted during the periodof observation, this did not approach statistical signifi-cance (average: 1 month = 16.75, 3 months = 14.5, 6months = 14.25 stools per 8-hour period.) No myotomywas clearly superior to the others or the straight pull-through.

Gastrointestinal transit time dropped markedly afterthe procedure (Fig. 4). The transit times decreased 65%at 1 month and changed little over the next 6 months.There were no differences between any of the myotomygroups or the straight pull-through.NaBr absorption was used as a marker of NaCI ab-

sorption. There were no significant differences in the ab-sorption ofNaBr between any ofthe experimental groupsat any time after operation, (p > 0.05; Fig. 5).

6

4-

E3-

S.

-0- circular- longitudinal* window* straight

1 0

time (wks)

FIG. 4. Gastrointestinal transit time after colectomy and ERPT.

Vol.211 *No.4

10

9

8

- 7

3: 6

windowcircularlongitudinalstraight

0 1 0 20 30time (wks)

FIG. 2. Postoperative weight gain.

5

TURNAGE, CORAN, AND DRONGOWSKI

40

30

E

010-

0-

a circularM longiludina.o window

FnG. 5. Absorption ofNaBr from the gastrointestinal tract after colectomyand ERPT.

FIG. 7. Neorectal capacity (direct measurement) 6 months after colectomyand ERPT.

D20 absorption has been shown to be a good referencefor water absorption. There were no significant differencesin the absorption of this isotope at 2, 4, and 12 weeksafter operation (Fig. 6). Both before operation and 6months after operation the straight pull-through groupabsorbed significantly more D20 then the other groups,(p < 0.05).The dimensions of the neorectum were measured with

two methods. Neorectal volume was estimated 6 monthsafter operation by measuring the volume ofwater acceptedby the neorectum after occluding the bowel 5 cm abovethe rectal muscular cuff. The capacity varied from 22 to30 mL and there was no significant difference betweenthe three myotomy groups (Fig. 7).The neorectal dimensions were also assessed using

roentgenographic measurements of anteroposterior andtransverse diameters of the terminal ileum with bariumenemas (Fig. 8). Again there were no differences betweenthe three myotomy groups. The neorectal dimensions ofthe animals with myotomies were significantly smallerthan the rectal dimensions of normal dogs. The dimen-sions ofthe straight ERPT without myotomy was betweenthese groups in that it was not different from the the un-operated controls and was not significantly different fromthe myotomy groups.

Barium enemas (Fig. 9) confirmed the absence ofprox-imal dilation. Also there was no evidence of stricture, fis-tula, or abscess formation.

100 -

0-

0

75 -

50 -

25 -

Postmortem gross inspection of the terminal ileum/neorectum demonstrated no abnormalities. There was noevidence of pelvic or perineal sepsis. None ofthe animalshad cuff abscesses to suggest a leak from the myotomysite. There was no inflammation of the mucosa on eithergross or microscopic examination to suggest pouchitis(Fig. 10). In all myotomy groups there was absence oftheileal muscularis propria and serosa on histologic exami-nation. The ileal submucosa was fused with the rectalmuscular wall of the cuff.

Discussion

Successful treatment of familial polyposis coli andchronic ulcerative colitis is afforded by total proctocolec-tomy and end ileostomy. However many patients are dis-satisfied with a permanent abdominal stoma. Because ofthis, alternatives to an end ileostomy have been developed;however a common unsatisfactory feature of these hasbeen high stool frequencies and diarrhea, especially in thefirst postoperative months. In a study by Morgan, Man-ning, and Coran,'0 the mean stool frequency 3 monthsafter the procedure was 1 1.8 stools per day. This decreasedto 9.6 and later to 8 stools per day at 1 and 3 years, re-spectively. However to many patients this still representsa significant handicap, although this has been almost uni-formly preferred to an abdominal stoma.

3.

-9 STRAIGHT-*-- CIRCULAR*--- LONGITUDINAL

--- WN

_ 2

U.-SE

1 -.1*

0-

-Lu

0

circularlongitudinalwindowstraightcontrol

A-P

FIG. 6. Absorption of deuterium oxide from the gastrointestinal tractafter colectomy and ERPT.

FIG. 8. Anteroposterior and transverse diameters of the neorectum 6months after colectomy and ERPT as measured by barium enema.

466100

75.0-

0o50-

* 25-

- -- STRAIGHT- CIRCULAR

LONGITUDINAL*VNDOW

o 10 20 30weeks

1 0 20 30weeks

Ann. Surg. * April 1990

-.0

Vol.211 .No.4 CAPACITY OF THE ENDORECTAL PULL-THROUGH

FIG. 9. Barium enema 6months after colectomy andERPT. There is no consistentdilatation of the terminalileum to suggest reservoirformation. The arrowheadsmark the extent of the rectalcuff and pulled-throughileum.

After Kock's27 addition of an ileal reservoir to a stan-dard Brooke ileostomy, modifications of this techniquehave been applied to the ERPT to reduce high postop-erative stool frequencies. Despite the introduction ofmanyvarieties of intestinal reservoirs, none have clearly emergedas superior to the others. This led to a study in our lab-oratory that demonstrated that in a canine model therewere no significant advantages of either the J-pouch, lat-eral isoperistaltic pouch, or the S-pouch over a straightERPT without a reservoir." The advantages of the latterinclude technical simplicity and avoidance oflong entericsuture lines.

Operative techniques to lower stool frequency usingartificial intestinal sphincters have been applied in animalexperiments of massive small bowel resection,'2"13"15 col-ectomy with ileoproctostomy16 and total abdominal col-ectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ERPT.17 Glassman28created an artificial ileocecal valve in dogs after ileoco-lostomy and noted that this improved the general healthof the animals as compared to controls. Schiller'2"13 pro-

duced artificial sphincters by removing the outer longi-

tudinal muscular layer of the small bowel. It was hypoth-esized that this would permit unrestricted contraction ofthe inner circular layer, thus recreating the mechanismof a sphincter and reducing the rate of intestinal flow indogs after massive enterectomy. Also he noted that themyotomy removed the myenteric plexus, thus creating a

localized segment of aganglionic bowel. He found thatthe artificial sphincter increased survival time, decreasedintestinal transit time, and decreased weight loss. Schiller,in replying to a paper by Richardson and Griffith, 4 statedthat he had studied intraluminal pressure within thesphincter and found it to be higher than in the surroundingbowel, thus supporting his theory of the formation of thissphincter. Richardson and Griffith'4 studied this sphincterin dogs after massive small bowel resection and foundthat the muscle ablation sphincter improved absorptionof fat and carbohydrates and reduced the bacterial over-

growth within the remaining intestine. Stacchini et al.'5further modified Schiller's technique by removing thelongitudinal muscle from a 1-cm area of small intestinealong its entire circumference. He also demonstrated im-

467

TURNAGE, CORAN, AND DRONGOWSKI Ann. Surg. * April 1990

..........

.. ..

...

4.15

w., .. .. ..A...... .... ........ ..

-A F,UR:::: A'm ME

4V

X

T I .0MA. j.,.i?P.'. .44M.....Aft.

.4:71

4.jK..T

Ab

T

R -4

'4Y.

M.7. W

A: 7A. W:

MWA1.11 iSS

P, &*4W,A-0%NS

...7 A-iV

Ac,'P!

FIG. 10. Histologic examination of the neorectum. The ileal mucosa is normal and the muscularis propria and serosa have been removed allowingapposition of the ileal submucosa and the rectal muscular cuff. The arrows mark the junction of the rectal muscularis propria (marked by the letter"R") with the pulled-through ileum. The ileal muscularis propria is marked by the letter "I". This histologic section was taken through a myotomyand demonstrates the absence of ileal muscularis propria in this region.

proved weight gain in dogs after massive small bowel re-section.

O'Malley et al.i7 performed a 20-cm longitudinal my-otomy in the ileum just above the peritoneal reflection indogs after total abdominal colectomy, mucosal proctec-tomy, and ERPT. He hypothesized that the myotomywould allow for distention ofthe distal ileum, which couldthen function as a reservoir. It was also hoped that themyotomy would dampen peristalsis through the myotomysegment. He demonstrated the maintenance ofweight af-ter operation, water and electrolyte absorption, and stoolfrequency equal to that after a J-pouch.

Aly and Fonkalsrud,29 using a 15-cm longitudinal my-

otomy in dogs after abdominal colectomy with ileosig-moid anastomosis demonstrated no distention ofthe my-otomized segment and thus believe that this techniquehad little application in the treatment of patients under-going ERPT when studied 4 months after operation.We have studied extensively three different types of

myotomies and demonstrated no differences in multiplephysiologic parameters of bowel function after ERPT.Similarly anatomic assessment with direct measurement

and barium enemas failed to demonstrate the consistentformation ofa reservoir proximal to the anus by 6 monthsafter operation. We could not demonstrate any benefit ofthe addition ofan intestinal myotomy to a straight ERPT.

References1. Ravitch MM, Sabiston DC Jr. Anal ileostomy with preservation of

the sphincter: a proposed operation in patients requiring totalcolectomy for benign lesions. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1947; 84:1095-1099.

2. Ravitch MM. Anal ileostomy with sphincter preservation in patientsrequiring total colectomy for benign conditions. Surgery 1948;24:170-187.

3. Ravitch MM, Handelsman JC. One stage resection of the entirecolon and rectum for ulcerative colitis and polypoid adenomatosis.Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1951; 88:59.

4. Martin LW, LeCoultre C, Schubert WK. Total colectomy and mu-cosal proctectomy with preservation of continence in ulcerativecolitis. Ann Surg 1977; 186:477-480.

5. Coran AG. New surgical approaches to ulcerative colitis in childrenand adults. World J Surg 1985; 9:203-215.

6. Coran AG, Sarahan TM, Dent TL, et al. The endorectal pull throughfor the management of ulcerative colitis in children and adults.Ann Surg 1983; 197:99-105.

7. Fonkalsrud EW. Total colectomy and endorectal ileal pull-throughwith internal ileal reservoir for ulcerative colitis. Surg GynecolObstet 1980; 150:1-8.

468

CAPACITY OF THE ENDORECTAL PULL-THROUGH

8. Parks AG, Nicholls RJ. Proctocolectomy without ileostomy for ul-cerative colitis. Br Med J 1978; 2:85.

9. Utsunomiya J, Iwama T, Imajo M, et al. Total colectomy, mucosalproctectomy and ileoanal anastamosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1980;23:459-466.

10. Morgan RA, Manning PB, Coran AG. Experience with the straightendorectal pull through for the management of ulcerative colitisand familial polyposis in children and adults. Ann Surg 1987;206:595-599.

1 1. Stoller DK, Coran AG, Drongowski RA, et al. Physiologic assessmentof the four commonly performed endorectal pull through. AnnSurg 1987; 206:586-594.

12. Schiller WR, DiDio LJA, Anderson MC. Production of artificialsphincters. Ablation of the longitudinal layer of the intestine.Arch Surg 1967; 95:436-442.

13. Schiller WR, DiDio LJA, Winter TQ, et al. Production of artificialsphincters of the gastrointestinal tract by ablation of the longi-tudinal muscle layer the intestine. Bull Soc Int Chir 1968; 5:449-455.

14. Richardson JD, Griffen WO. Ileocecal valve substitutes as bacteri-ologic barriers. Am J Surg 1972; 123:149-153.

15. Stacchini A, DiDio LJA, Primo MLS, et al. Artificial sphincters assurgical treatment for experimental massive resection of smallintestine. Am J Surg 1982; 143:721-726.

16. Ghory MJ, Pekcan M, Hebiguchi T, et al. A muscle ablation sphincterto prevent diarrhea after total colectomy in puppies. A preliminaryreport. J Pediatric Surg 1985; 20:302-306.

17. O'Malley VP, Keyes DM, Cannon JP, Postier RG. Longitudinalileal myotomy: a new reservoir for use with ileoanal anastamosis.Current Surg 1985; 42:113-117.

46918. Visscher E, Stanton F, Carr CW. Isotopic tracer studies on the

movement of water and ions between intestinal lumen and blood.Am J Physiol 1944; 142:550-575.

19. Scholer JF, Code CF. Rate of absorption of water from stomachand small bowel of human beings. GE 1954; 27:565-576.

20. Schloerb PR, Friis-Hansen BJ, Edelman IS. The measurement oftotal body water in the human subject by deuterium oxide di-lution; with a consideration of the dynamics of deuterium dis-tribution. J Clin Invest 1950; 29:1296-13 10.

21. Palmer JW, Clarke HT. The estimation ofbromides from the blood-stream. J Biol. Chem 1932; 99:435-445.

22. Geiling EM, Hunt R, Marshall EK. Proceedings from the AmericanSociety for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics In-corporated. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1938; 63:63-67.

23. Sendrov J. Microdetermination of chloride in biological fluids withsolid silver iodate. J Biol Chem 1937; 120:405-417.

24. Hastings AB, Harkins SK. Blood and urine studies following bromideinjection. J Biol Chem 1931; 94:881-895.

25. Wolf RL, Eadie GS. Reabsorption of bromide by the kidney. Am JPhysiol 1950; 163:436-441.

26. Drongowski RA, Coran AG, Wesley JR. Modification of the serumbromide assay for the measurement of extracellular fluid volumein small subjects. J Surg Research 1982; 33:423-426.

27. Kock NG. Intraabdominal "reservoir" in patients with permanentileostomy; preliminary observations on a procedure resulting infecal "continence" in five ileostomy patients. Arch Surg 1969;99:223-230.

28. Glassman JA. An artificial ileocecal valve. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1942;74:92-98.

29. Aly A, Fonkalsrud EW. Construction of ileal reservoir with longi-tudinal ileal myotomy. Am Surg 1988; 54:475-478.

Vol.211 * No.4