The Third Dimension: Locality and Linguistic Landscapes · 2016-05-02 · The Third Dimension:...

Transcript of The Third Dimension: Locality and Linguistic Landscapes · 2016-05-02 · The Third Dimension:...

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 1Spring 2016

!

The Third Dimension: Locality and Linguistic Landscapes

Hend M. Ghouma Indiana University of Pennsylvania

Abstract Studies of linguistic landscapes have gained wide interest recently (Bolton, 2012). Different studies documented the use of English in public spaces, such as the use of English in the bilingual landscape of Chinatown in Washington, DC (Lou, 2012); the English used in Thai internet advertisements (Troyer, 2012); and the multilingual political graffiti depicted on the separation wall between Palestine and Israel (Hanauer, 2011). Furthermore, studies explored the use of English in linguistic landscapes from different aspects. Some documented the percentage of using English in these landscapes in comparison to other language(s) (Hanauer, 2011; Lawrence, 2012). On the other hand, other studies focused on the significance of the location of graffiti, for instance in relation to space, time, and the domain (Bordin, 2013; Hanauer, 2004, 2011; Pennycook, 2010). Lawrence (2012) documented the English signage and graffiti in different cities around Korea and compared it with the use of Konglish and the local Korean language, in addition to the Chinese language. Bordin (2013), on the other hand, documented graffiti in a train and what this act of resistance signifies in terms of the geo-space and the control of a public domain.

Pennycook (2010) has argued that language should not be examined in isolation. In other words, the time, space and the location where the linguistic forms are found should be examined when scrutinizing any linguistic forms. In addition, the analysis of any foreign language in linguistic landscapes should involve a bottom-up study of the language as a local practice, prior to linking it to the global function of language (Pennycook, 2010). The locality of language could potentially change the meaning of these linguistic forms drastically. The aim of this paper is to apply the concept of “spatial turn” or the third dimension introduced by Pennycook (2010) on language practice in the study of linguistic landscapes. The significance of the spatial turn would be examined in light of a sample of graffiti that was drawn in Tripoli, the capital city of Libya. Furthermore, the paper aims at examining the concept of “multivocality” in relation to the location of the graffiti.

Through examining the sample of the graffiti in this study, it is concluded that the location of where these graffiti were found adds another layer of meaning that could not be understood without examining the geographical location of these linguistic landscapes.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 2Spring 2016

Introduction

When we examine linguistic forms, we often extract them and try to qualitatively and/or

quantitatively study them and treat languages as “system or as countable entities” (Pennycook,

2010, p. 1). Researchers often link linguistic forms to the time and the space where they

occurred. However, in the analysis of these linguistic forms, the location of these forms is

excluded, when it was the sole purpose of the writer to write in those specific domains to target a

specific passerby (the locals, for instance), or even to attract the international community.

Pennycook (2010) argued that “[t]o speak of language as a local practice is to address not only

the embeddedness of language in place and time, but also the relation between language locality

and a wider world” (p. 78). Often when public language forms are examined, issues such as time,

space, place, and even identity of the writers are taken into consideration. However, examination

and analysis of language forms that exclude the locations of these places in relation to the locals

neglect a substantial part of what these forms convey. Sayer (2010) argued that the audience for

whom those linguistic forms were written should be considered in examining linguistic

landscapes. The purpose of using English in a specific landscape, for instance, could potentially

define the function of English in that context.

Languages written on public platforms in general gain another meaning when passersby

see them. For instance, graffiti written in the back alleys does not have the same connotation as

that on the wide streets or on government buildings. This paper attempts at drawing on the

significance of location in the examination of linguistic forms. In addition, it signifies the

importance of examining the English used in public platforms, specifically graffiti in Tripoli, the

capital of Libya, first as a local practice that occurs in a specific local dimension, and second as a

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 3Spring 2016

global practice. Furthermore, the study examines the concept of “multivocality” in relation the

location of the graffiti.

Language and Locality

Places are not founded randomly. In ancient civilizations people gathered around sources

of water and food and built civilizations. Foucault (1997) argued that people shifted places

during the past centuries according to their beliefs. For instance, cemeteries that used to be in the

center of urban areas when people believed in the afterlife shifted to peripheries of urban areas

when people began to see them as a potential cause for disease spread.

The constructions built around cities are for certain plans or according to certain reasons.

The building of mosques in every neighborhood in the capital city of Libya, for instance, is to

accommodate the number of people who go there every Friday for prayers. Foucault (1997)

stated that “we do not live in a sort of a vacuum, within which individuals and things can be

located, or that may take on so many different fleeting colors, but in a set of relationships that

define positions which cannot be equated or in any way superimposed” (p. 331). The schools, the

hospitals, and even the military bases are built according to certain needs and specific agendas.

In Ain-Zarah, a small urban area in the southern part of Tripoli, a military base is built

approximately at every four miles. The location of military bases in such large numbers in an

urban area seems to serve the purpose of securing any civil unrest that might arise during the rule

of the former dictator Ghadafi 1969-2011. The relations that people develop with these places

build what Pennycook (2010) has referred to as the locality. The connotation that places have

differs from one country to another and within the same country among individuals. Therefore,

the languages such as that in graffiti writings that appear on these places have two layers of

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 4Spring 2016

meaning. The first is linked to the immediate place of the construction itself and what it signifies

in relation to the geographical location, and the second is linked to the relation between the

locals and their view of the place and how that might affect how the language(s) are perceived.

Pennycook (2010) has argued, “language practices are activities that produce time and

space” (p. 56). The meaning of certain language forms could change over time and place, and

meaning can further change when it is transmitted over locations or when language forms are

taken out of their location. The perceived definition of language as a system of communication

used in different context has been challenged. Conversely, language is produced when people

interact in social and cultural activities (Pennycook, 2010).

Researchers have argued that studies of language and of linguistic landscapes should be a

bottom-up process rather than a top-down (Hanauer, 2011; Pennycook, 2010). Therefore, English

used in graffiti should be examined from the locals’ points of view and in relation to the local

language before looking into any potential global functions. Though the English used might have

stemmed from inner or the outer circle countries according to Kachru’s (1985) three-circle

model, it is the result of locals’ interaction with the language which eventually resulted in the

production of their own use of English.

English as Local and Global Practices

Some researchers’ (Pennycook, 2010; Sayer, 2010) tendency to examine the English used

in linguistic landscapes as a local practice originates from the belief that such practice is not the

result of the spread of English from “Inner Circle” countries (Kachru, 1985) but rather the result

of perceiving that English as a production of the locals instead.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 5Spring 2016

The false dichotomy of often conceiving the use of English in “Expanded Circle”

countries (Kachru, 1985) or former colonies, as a post-colony resistant form of the language, is

further challenged by researchers (Higgins, 2009; Pennycook, 2010; Sayer, 2010). Higgins

(2009) stated that English used within post-colony countries of Britain is often connected to the

locals’ need to communicate with the global community, neglecting the obvious function that

meant to serve the locals. Sayer (2010) further emphasized that “we can see that as English

becomes increasingly globalized, it also acquires new, local meanings as people in those contexts

take it up, learn it, and begin to use it for their own (whether global or local) purposes” (p. 151).

The function of English in what Kachru (1985) terms the “Expanding Circle Countries”

has often been documented in different studies (Hanauer, 2004, 2011; Kasnaga, 2012; Lawrence,

2012; Lou, 2012; Martin, 2007; Sayer, 2010). Such studies came to a consensus when it came to

the fact that English serves a local function within the communities where it was documented, in

addition to the international or the global function. English, as a local language, seems to serve

many functions within the local context. Bruthiaux (2003) argued that in Expanding Circle

countries, “the use of English reflects in part (legitimate) aspirations for a better future among

educated, outward looking individuals, who see English as a modernizing force operating in

conjunction with other indicators of socioeconomic development such as increased international

trade” (p. 169). English is often seen as a marker of modernity and prestige; however, in these

same circumstances it is perceived as a “sign of arrogance” (Kasanga, 2012, p. 52).

In his study of the English used in linguistic landscapes in Oaxaca in Mexico, Sayer

(2010) came to the conclusion that the use of English was connected to the social values it

represented and listed the following as functions that English played: advanced and

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 6Spring 2016

sophisticated, fashionable, cool, sexy, for expression of love, and for the expression of

subversive identities.

Sharifian (2009) has stated that English has played many roles in people’s lives whether

to depict marginalization and hegemony or to establish power and “upward mobility” (p. 1).

Lawrence (2012) added that English used in some of the graffiti under bridges, which showed

names of individuals rather than their tags, was for the sole purpose of “resistance identities” (p.

85). Lawrence (2012) argued that these individuals used English to “‘voice’ their identity” (p.

85). On the other hand, English is used in “linguistic landscapes of contemporary Korea served

as a marker of modernity, luxury and youth.” (Lawrence, 2012, p. 9)

Lawrence (2012) stated that, in Korea and other Asian countries, attitudes towards the use

of English range from positive to neutral to negative (p. 72). He argued that while some

researchers linked the use of English to “internationalization,” “reliability,” “modernity,” and

“sophistication,” others documented the neutral attitude Asian countries have towards the use of

English in reference to its use in technological terminology, “neologisms” and

“euphemisms” (Lawrence, 2012). On the other hand, Collins (1995) noted that English is

sometimes perceived in a negative manner: For instance, in Korea, the use of English by pop

stars has been considered as pro-Japanese and pro-U.S military government (as cited in

Lawrence, 2012). Martin (2007), on his account of the English used in French advertising

discourse, argued that English served as a lingua franca for global audiences and reflected the

“linguistic and cultural reality of French” (p. 185).

On the other hand, when looking at English from a local to a global perspective, English

seems to act as a connection between the local and the global. Hanauer (2011) argued, in his

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 7Spring 2016

documentation of the use of English in graffiti written on the separation wall between Israel and

Palestine, that English was written for the international community. Sharifian (2009) stated that

English as an International Language includes all varieties of English that are used as

“intercultural” communication. Pennycook (2003) termed the English used for international

communication as “transcultural.” Speakers of World Englishes in their use of English take it to

a new level of internationalism by addressing the global community (Pennycook, 2003;

Sharifian, 2009).

English as an international language originated from locals adopting English and

institutionalizing it (Pennycook, 2003), and further developing a relationship with the language

that “touched their identities, cultures, emotions, personalities . . . so the stories they tell reveal

significant links between language, culture, and identity (Sharifian, 2009, p. 5). Thus English

developed locally is used for global purposes, and that is to reach out to the international

community.

Multivocality and Location

Multivocality is used to refer to an utterance that has more than one voice or one

interpretation. Higgins (2009) stated that “multivocality” refers,

to the different ‘voices’ or polyphony that single utterances can yield due to their

syncretic nature. Creative language forms are frequently produced when speakers

intermingle the languages and language varieties circulating in their daily lives. The

results of this multilingual practice are varied and can take the form of assimilation into a

language (i.e. borrowing), language mixing (the use of two or more languages that

produces no pragmatic effect), and code switching. (p. 7)

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 8Spring 2016

Multivocality allows the analysis of the use of English in utterance to different interpretation.

Higgins (2009) stated that might include “linguistic imperialism” and “global hegemony,” in

addition to “resistance to imperialism.” However, it might further include the locals’ adaptation

of English for their own local use (Pennycook, 2003).

English Graffiti in Tripoli-Libya

The use of English in graffiti has been widely observed around the world. Graffiti in

Libya is a relatively recent phenomenon (Ghouma, 2015). Political graffiti did not exist before

the 2011 revolution. According to Kachru’s (1985) three-circle model, Libya falls within the

“Extended Circle Countries.” Remarkably in a sample collected from three main streets in the

capital of Libya, English appeared in more than 27% of the photographs taken (Ghouma, 2015).

The use of English in a country where the former regime had long been known for its political

dispute with the United States and England, and for banning teaching English for almost a

decade, serves as a form of resistance (Ghouma, 2015). However, the English documented in the

graffiti can be analyzed further from two main perspectives: first as a local and a global practice

and second in relation to its location.

The graffiti used in the study was drawn between August 2011 and October 2013.

Photographs of the graffiti were taken by an individual from the walls of the 77 Military

Compound, Zawiyat E-Dahmani, and Ben Ashour areas. The photographs were taken in

September 2013. The total number of photographs is 79. The sample used in this paper is

comprised of only eighteen photographs. The eighteen photographs were chosen because they

contained English inscriptions.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 9Spring 2016

The photographs are divided into two territories according to where the graffiti was

found. The first territory includes two areas, Ben Ashour and Zawiyat E-dahmani. The reason I

combined the two areas under one territory is their closeness in terms of geographical location

and in their role during the revolution (Ghouma, 2015).

The function of the use of English in linguistic landscapes is defined within the location

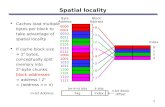

and purpose and the audience it was directed towards (Sayer, 2010). In Figure 1, English graffiti

appears on the walls of a former police station located in Zawiyat E-dahmani. The history of the

police station is well known by the locals. The stories of interrogations, torture, and the

disappearance of Libyans that took place in police stations are evident in people’s minds when

they attacked and burned down the place during the first days of the 2011 revolution. However,

the graffiti on the wall with the English visual inscription of “STOP WAR” and Arabic

inscription of “God is the greatest” seems to contribute two opposite meanings. The Arabic

inscription is a form of a celebration of the taking of the city from Gadhafi’s forces. On the other

hand, the second inscription in English is in reference to the need of stopping the killing of

innocent Libyans by Gadhafi and his loyalists, if I am to consider it was written by a freedom

fighter. However, if I am to weigh in the small possibility that the English inscription was written

by a Gadhafi loyalist, then the meaning takes a whole new direction and becomes a message

targeting the international community to stop the NATO bombing and targeting of Gadhafi’s

loyalists. In Figure 1 the English inscription had two possible layers of meaning: the local and

the international.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 10Spring 2016

�

Figure 1. Police Station in Zawiyat E-dahmani: Visual inscription in English “STOP WAR” and Arabic “God is the greatest (هللا اكبر).”

In the second figure, the same notion of multivocality observed in Figure 1 seems to

repeat itself; however, the meaning that can be voiced from the English visual inscription that

appears in Figure 2 seems to originate from the same side of fighters, the rebels. The colors of

the new Libyan flag, symbolizing the new revolution, leave no room for any interpretation

related to Gadhafi’s loyalists. The graffiti was definitely drawn by a rebel fighter or a

sympathizer. The graffiti appearing in Ben Ashour Area with the visual inscription of

“FREEDOM.LIBYA” can be understood from two main perspectives: one as a celebration of

freeing Libya from Gadhafi’s rule, or a second which is the hope for that to happen. Perhaps the

hand that appears in the middle of the word “FREEDOM” that symbolizes “either winning or

dying” is an indication of the ongoing battle and the probability of the second interpretation.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 11Spring 2016

!

Figure 2. A street in Ben Ashour Area: English inscription “FEEDDOM.LIBYA.”

The two graffiti that are shown in Figures 3 and 4 appeared on the walls of the 77

Military Compound, one of the largest military compounds in the capital and a residence of the

former dictator Gadhafi. The writing on those walls adds a new level to the meaning inscribed of

“RESPECT” and that “The law is over ALL.”

In Figure 3, the word “RESPECT” appears on the wall of the 77 Military compound and

implies two meanings: first, the demand to be respected by the new leadership in Libya, and the

second is the gaining of the respect after ousting the Gadhafi regime that had long demeaned its

people and degraded them (Ghouma, 2015).

!

Figure 3. The word “RESPECT” on the walls of the 77 Military Compound.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 12Spring 2016

The 77 Military compound, the outside walls of which appear in the photograph of Figure

4, is one of the strongest military compounds in Tripoli. Furthermore, its location near the

residency of the former president Gadhafi added to the significance of taking over such a

significant place during the war. The history that is attached to military compounds and what

occurred behind those walls during the rule of Gadhafi gave them another meaning in the eyes of

the locals. Passersby of this military compound in the time of the rule of the Gadhafi could feel

the eyes of his men that watched every move in the areas surrounding his residency. After the

rebels took over Tripoli and wrote on those same walls, that projected long the fear and the

possible threat rendered vacant after NATO bombarded it. However, the writings on its wall

“Law is over ALL” still seem to make reference to the place before conquering it by the rebels.

The graffiti seems to reference those people who hid behind those walls and committed crimes

against the Libyans in the name of security, in addition to referencing the former ruler who lived

behind those walls. It is further a call for the new government not to repeat the history, a form of

a reminder that what happened behind those walls is not going to happen again. Another voice

can be read in this same statement, a declaration of establishing the law in a country that was

known for a long history of corruption (Transparency International, 2010).

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 13Spring 2016

!

Figure 4. The military compound: English inscription of “Law is over ALL.”

Political graffiti is meant to be displayed. It usually appears on sites that either were or

became tourist attractions, such as the separation wall between Palestine and Israel (Lovatt,

2010), or the one that witnessed a turning event in a history of a country such as the Berlin Wall.

The political graffiti that appeared in Libya during and after the revolution in 2011 attracted

international media. The three different places that appear in the data of this paper exemplify the

significance of the message displayed in terms of the place and the location.

Ben Ashour and Zawiyat E-dahmani are two areas in Tripoli that witnessed some of the

heaviest fighting between the former government and the rebels (Ghouma, 2015). The heavy

fighting is an indication of resistance. Many residents in these two areas opposed the regime and

either joined or aided the rebels in those battles. The second indicative could point to the

potential cause for these areas to join/aid the rebels. Gadhafi’s long, bloody history is no secret to

anyone in the country; he ruled for decades. Many families in Libya had someone who was

killed, served time in jail for political reasons, or had to live in exile.

Furthermore, these two areas are known to be the residences of some of the wealthiest

families in Tripoli. Seven years after his coup in 1969, Gadhafi declared what he called “The

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 14Spring 2016

People’s Revolution,” in which he basically confiscated the property of well-off people and

distributed it to his loyalists. As a result, many families lost their businesses or properties, such

as lands and commercial shops that they had worked years to build. These people were a

percentage of those who rose against Gadhafi during the revolution to claim their rights and seek

justice on those who had taken over their property for more than thirty years.

Pennycook (2010) argued that “(discourse produces language rather the other way

around)”; he further added that “(the local produces the spread rather than the spread becoming

local)” (p. 77). These two statements are proven in the graffiti collected in two clear examples.

Pennycook (2010) emphasized, “Local language practices do not reflect the local reality but are

part of its production” (p. 72). The drawing of graffiti on those walls and the use of English was

no random act.

The use of phrases and words of celebration in the areas of Ben Ashour and Zawyiat E-

dahmani is a manifestation of the domain, of the fighting, and of the ordeal that the residents of

these areas witnessed after being targeted by the regime. All the circumstances right before the

liberation of these areas from Gadhafi forces created the language that would not propose the

same meanings or convey the same feelings if it were on other random walls. When residents of

those areas pass by these walls, it would further give them another dimension of meaning other

than the time, the space—and that is the location and what that implies.

The analysis of the language used in the graffiti cannot be accomplished without deep

analysis and consideration of the geographical location, space, and the time. Perhaps this takes

me back to why graffiti was painted on these specific walls. The geographical location of these

walls added another layer to the messages and words written on those walls. The use of English

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 15Spring 2016

along with the local language, sometimes translated and often not, provides another layer of

meaning to these linguistic forms.

To examine the graffiti from a bottom-up approach, first we have to look into the function

that English serves in Libya. English was banned during the eighties by the former regime and

considered the language of the enemy (Ghouma, 2015). A certain animosity was created toward

those who used it in public places or in the media; however, this was only limited to groups that

followed the regime and were part of it. Many parents enrolled their children early on in their

educational career in English courses, and this perhaps can be attributed to two main reasons: to

help children in their college career and because English is considered as the language of the

elite and the privileged.

As a result, the English used in the graffiti can be viewed to serve three main functions.

In addition to being a language of resistance, English in the graffiti is used as the language of

power. Moreover, in addition to the local function of the use of English in graffiti, the

international dimension is manifested due the nature of the Libyan revolution that had the

international support. The revolution in Libya won the international community’s sympathy early

on in its days. The international intervention was effective less than two months after the

revolution started. The involvement of the international community has perhaps continued to

impact on the country. The use of the sentence “Law is over ALL” is perhaps one of the

sentences that speaks both for the local as well as for the international communities—for those

who came to watch Libyans lead their country after ousting the regime. Libyans knew the world

was watching them. Television channels were visiting and documenting these sites, especially

the former residence of Gadhafi.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 16Spring 2016

The concept of multivocality is presented in the three graffiti by the use of English.

Despite the inability to define the time in which these graffiti were written, the place plays the

second role in defining the meaning of these inscriptions. These places and their history seem to

produce these utterances. Further, the significance of where these graffiti appeared adds another

layer of meaning.

Conclusion

In this study, graffiti artists have always considered their audience. Their message on

public walls was meant to be read and targeted a specific local and/or international audience.

Furthermore, their messages were coined from local contexts. And to understand that context, we

must look deep into the construction of those spaces and their meaning to understand the

language being used. The use of English in those spaces should be interpreted from the locals’

perspective first for being a product of the locals and then could be linked to the possible global

meanings.

Multivocality of utterances that have English usage in them points to the double meaning

or the layers of meaning and the way these utterances function locally and on the international

level. To neglect the local meaning that primarily constructed those utterances and that are

heavily embedded with the culture or identity of those who produce it is to leave out a large part

of the meaning intended.

Location produces as much as contributes to the meaning formed by the locals. Whether

the locals’ utterances were in their own language or whether they adopted another language to

become their local variety can be defined within how the language functions that is to convey

messages to the locals and/or to the “Expanded” international community.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 17Spring 2016

Graffiti is not just writing on the wall; it represents many aspects of the graffiti artists’ life

and personality, of the time, and of the space and of the location of where the graffiti was found.

Pennycook (2010) argued that “[g]raffiti is one of the ways cities are brought into life and space

is narrated” (p. 56). Therefore, the main aim of the study was to bring these linguistic landscapes

presented in the graffiti “to life” by signifying the location as a key element in examining the

embedded functions of the graffiti.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 18Spring 2016

References

Bolton, K. (2012). World Englishes and linguistic landscapes. World Englishes, 31(1), 30-33.

Bordin, E. (2013). Expanding lines: Negotiating body, space and language limits in train

graffiti. Rhizomes, 25.

Bruthiaux, P. (2003). Squaring the circles: Issues in modeling English worldwide. International.

Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 159-178

Corruption perceptions index. (2010). Transparency International: The global coalition

against corruption. Retrieved from http://www.transparency.org/cpi2010/results

Foucault, M. (1997). Of the other spaces: Utopias and heterotopias. In N. Leach (Ed.),

Rethinking architecture: A reader in Cultural Theory (pp. 330-336). New York, NY:

Routledge.

Ghouma, H. (March, 2015.) Graffiti in Libya as Meaningful Literacy. Arab World English

Journal (AWEJ), 6(1), 397-408.

Hanauer, D. (2004). Silence, voice and erasure: psychological embodiment in graffiti at the site

of Prime Minister Rabin’s assassination. Psychotherapy in the Arts, 31, 29-35.

doi:10.1016/j.aip.2004.01.001.

Hanauer, D. (2011). The discursive construction of the Separation Wall at Abu Dis

Graffiti as political discourse. Journal of Language and Politics, 10(3), 301-321.

doi:10.1075/jlp.10.3.01han.

Higgins, C. (2009). English as a local language: Post-colonial identities and multilingual

practice. Tonawanda, NY: MPG Book Group

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 19Spring 2016

Kachru, B. B. (1985). Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language

in the Outer Circle. In R. Quirk & H. G. Widdowson (Eds.), English in the world:

Teaching and learning the language and literatures (pp. 11-30). Cambridge, United

Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Kasanga, L. (2012). English in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. World Englishes, 31(1),

48-69.

Lawrence, B. (2012). The Korean English linguistic landscape. World Englishes, 31(1), 70-92.

Lou, J. (2012). Chinatown in Washington, DC: The bilingual landscape. World Englishes, 31(1),

34-47.

Lovatt, H. (2010). The Aesthetic of space: West Bank graffiti and global artists.

Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/935825/The_Aesthetics_of_Space_

West_Bank_Graffiti_and_Global_Artists

Martin, E. (2007). “Frenglish” for sale: Multilingual discourses for addressing for addressing

today’s global consumer. World Englishes, 26(1), 170-188.

Pennycook, A. (2003). Global Englishes, rip slime and performativity. Journal of

Sociolinguistics, 7(4), 513-533.

Pennycook, A. (2010). Language as a local practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sayer, P. (2010). Using the linguistic landscape as a pedagogical resource. English Language

Teaching Journal, 64 (2), 134-154. doi:10.1093/elt/ccp051

Sharifian, F. (Ed). (2009). English as an international language: Perspectives and pedagogical

issues. Ontario, Canada: Multilingual Matters.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 20Spring 2016

Troyer, R. (2012). English in the Thai linguistic landscape. World English, 31 (1), 93-

112.

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 21Spring 2016

BenAshour&ZawiyatE-dahmani

Photo(1)

Photo(2)

Photo(3)

Photo(4)

Photo(5)

Photo(6)

Photo(7)

Freedom

Thankyourevolu

FreeLibya

ReutersTV

Kara(name)

Knanina(name)

Snap

Esp

StopWar

RevoluGon

Tripoli

LibyaFree

FreedomLibya

17Feb

املجد للشهداء

اهلل اكبر

فبراير 17

تورة الحريه

ليبيا حره

حريه

جامع القبطان

فبراير 17

معليشي شفشوفه

توار جامع القبطان

طريق الصور

اهلل

اهلل اكبر

ابدأ بنفسك

ثوره

ليبيا الصمود

GloryforMartyrs

GodisGreat

17February

FreedomRevoluGon

Libyaisfree

Freedom

QubtanMosque

February,17

ItisOkMessyhair

QubtanMosqueRebels

SourRoud

God(Allah)

God(Allah)isGreat

Startwithyourself

DefyingLibya

Working Papers in Composition and TESOL • Ghouma ! 22Spring 2016

Photo(12)

Photo(13)

Photo(14)

Libya

MEDO

KindnessisFree

البناء

رضا ابوشويقير

اعادة االعمار

محمد البوعيشي

ConstrucGng

RedaAbushweger

Rebuilding

MohamedBu-Ashi

Photo(15)

Photo(16)

Photo(17)

Photo(18)

RESPECT

Youth

DCA

Libya

Freedom

هاشم

حريه

Hashim(name)

Freedom