The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10_ Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

-

Upload

theideatingfreak -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10_ Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 1/8

BIOLOGY | HISTORY

The Seeds That Sowed aRevolution

Galapagos Finches are famous, yet Darwin learned more about evolution from the plants.d

BY HENRY NICHOLLSILLUSTRATION BY GABY D’ALESSANDRO

FEBRUARY 13 , 2014

ADD A COMMENT FACEBOOK TWITTER EMAIL SHARINGc f t m U

hen the HMS Beagle dropped anchor on San Cristobal, the easternmost island in the Galapagos archipelago, in

September 1835, the ship’s naturalist Charles Darwin eagerly went ashore to gather samples of the insects, birds,

reptiles, and plants living there. At first, he didn’t think much of the arid landscape, which appeared to be “covered

by stunted, sun-burnt brushwood…as leafless as our trees during winter” But this did not put him off. By the time the Beagle left

these islands some five weeks later, he had amassed a spectacular collection of Galapagos plants.

It is fortunate that he took such trouble. Most popular narratives of Darwin and the Galapagos concentrate on the far more

celebrated finches or the giant tortoises. Yet when he finally published On the Origin of Species almost 25 years later, Darwin

made no mention of these creatures. In his discussion of the Galapagos, he dwelt almost exclusively on the islands’ plants.

By the early 19th century, there was increasing interest in what we now refer to as biogeography, the study of the distribution of

species around the globe. Many people still imagined that God had been involved in the creation of species, putting fully formed

versions down on Earth that continued to reproduce themselves, dispersing from a divine “center of creation” to occupy their

current habitats. To explain how the plants and animals reached far-flung places such as the isolated Galapagos, several

naturalists imagined that there had to have been land bridges, long-since subsided, that had once connected them to a continent.

But in the wake of the Beagle voyage, the collection of Galapagos plants suggested an alternate scenario.

W

But when the botanist began to study the leaf structure and the flowers andseeds in minute detail, he was in for a big surprise.

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 2/8

Even if there had once been a land bridge to the islands, it could not account for the fact that half of the plant species Darwin

collected were unique to the Galapagos, and that most of them were particular to just one island. “I never dreamed that islands,

about fifty or sixty miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite

similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted,” wrote Darwin in his Journal of Researches.

His observations could be best explained if species were not fixed in nature but somehow changed as the seeds traveled to

different locations.

In order to make that conjecture, Darwin needed to classify the plants. Given his limited

botanical expertise, he turned to a young botanist named Joseph Dalton Hooker. Darwin was

excited to find out the number of different plant species he’d collected and their distribution

across the archipelago. At first, Hooker did not anticipate a huge amount of novelty. “The

species will no doubt be peculiar but they may not form peculiar genera of more than one or

two species.” In other words, he expected most of the Galapagos plants to fit into the

established botanical framework.

But when the botanist began to study the leaf structure and the flowers and seeds in minute

detail, he was in for a big surprise. “The Galapagos plants are far more extensive in number of

species than I could have supposed,” he wrote to Darwin in great excitement in late 1843.

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 3/8

Although they resembled the vegetation from mainland South America, almost half of the flora appeared to be endemic, found

only in the Galapagos. Even more interestingly, Hooker noted that almost every species of flowering plant and fern that he

described was confined to just one island. This “most strange fact,” wrote Hooker, “quite overturns all our preconceived notions

of species radiating from a centre.” Rather, each different island had its own similar, yet different flora.

Darwin, in turn, was ecstatic. “I cannot tell you how delighted & astonished I am at the results of your examination; how

wonderfully they support my assertion on the differences in the animals of the different islands.” In addition to Hooker’s insights

into the distribution of plants in the Galapagos, his paper On the Vegetation of the Galapagos Archipelago contained some very

interesting speculation about how plants had got to the islands in the first place. For example, Hooker noted that in comparison

to the tropical plants from the continent, the Galapagos flora contained a far smaller proportion of a particular kind of flowering

plant. Perhaps, he suggested, there might have been “obstacles to the transport of seeds from the continent.” He went on to

suggest four main routes through which plants might have reached the Galapagos. “The means of transport which may have

introduced these plants are, oceanic and aerial currents, the passage of birds and man,” he wrote.

Hooker guessed that most of the species found near the coast had probably reached Galapagos by floating, their tough seeds

helping them “in resisting for some time the effects of salt water.” There were also some species beyond the coast with seeds

“too large for probable transport by winds” and “no means of attaching themselves to birds” that had probably also taken an

oceanic route to Galapagos. Hooker felt that it was only species with small seeds or those “furnished with wings or other

appendages” that might have arrived on the wind. Birds, he felt sure, could account for many of the presence of many of the

plant species lying further from the coast. It was known that humans had visited the Galapagos so it was clear that they had

brought plants too, for Floreana—then the only inhabited island—was the only one with a significant number of plants that could

be exploited as food.

In 1855, Darwin put his mind to testing some of Hooker’s predictions. He began by playing around with seeds and seawater at his

home in the English countryside south of London. He kicked off with species he could easily get his hands on—cress, radish,

cabbage, lettuce, carrot, celery, and onion—just to establish whether seawater kills seeds. It was a question he admitted “might

naturally appear childish to many,” but one that produced some intriguing results and unexpectedly profound conclusions.

He left the seeds in salt water for a week before planting them in little pots. To his surprise, they all germinated. “It is quite

surprising that the Radishes shd have grown, for the salt-water was putrid to an extent, which I cd not have thought credible had

I not smelt it myself,” he wrote. He went further, buying seeds of still more species and gradually extending the length of time

they were immersed in his seawater concoction. By the time he published On the Origin of Species in 1859, he had exposed the

seeds of 87 different plant species to these hostile conditions. Incredibly, nearly all of them germinated after stewing in brine.

Some survived just days, but others still seemed in perfectly good working order after several months.

If you have a fussy reproductive set-up, the odds of surviving on a remote islandin somewhere like the Galapagos are stacked against you.

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 4/8

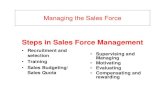

Drawings of Galapagos plants from another expedition in the late 19th century. B. L. Robinson

Suddenly, the vast expanse of salty ocean between South America and the Galapagos did not seem to be such an obstacle. There

was, however, a snag: A lot of the seeds he experimented with sank and would have been lost in the oceanic depths long before

reaching the Galapagos. But Darwin had an answer to this, discovering that the condition of the seed affects its buoyancy. “For

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 5/8

instance, ripe hazel-nuts sank immediately, but when dried, they floated for 90 days and afterwards when planted they

germinated,” he wrote in On the Origin of Species. Likewise, “an asparagus plant with ripe berries floated for 23 days, when dried

it floated for 85 days, and the seeds afterwards germinated.”

Even a seed that sinks, Darwin realized, might still be carried on ocean currents if it hitches a ride on a clod of earth attached to

the roots of some big tree or is protected inside the carcass of a dead animal. To illustrate this possibility, he fed a pigeon on

seeds that would normally be “killed by even a few days’ immersion in sea-water.” He then sacrificed it and floated its body on

salty water for a month. To his great surprise (and, one imagines, satisfaction), the delicate seeds “nearly all germinated.”

If most seeds could survive weeks in seawater, would they be able to reach remote islands like the Galapagos intact? Darwin

hauled A. K. Johnston’s Physical Atlas from his bookshelf and worked out that the Atlantic currents run at an average of 33 miles

per day, fast enough to carry a significant proportion of seeds a very long way before they either sank or succumbed to the salty

insult. In the case of the Galapagos, the current that flows out from continental South America runs considerably faster, often

around twice Johnston’s Atlantic average. So a back-of the-envelope calculation suggests that a seed—either floating or hitching

a ride—could reach the Galapagos in just over nine days. Those species with the most delicate seeds might not make it. But a lot

of species would.

Although some Galapagos plants clearly came on ocean currents and others on the wind, it’s thought that most Galapagos plants

arrived with help from birds. “Living birds can hardly fail to be highly effective agents in the transportation of seeds,” Darwin

wrote in the Origin. Obvious as it might be, he still sought evidence, going out into his garden in search of bird droppings. “In the

course of two months,” he wrote, “I picked up in my garden 12 kinds of seeds, out of the excrement of small birds, and these

seemed perfect, and some of them, which I tried, germinated.” He also dug around in the mud and showed it was full of seeds, in

one instance a small cupful of sludge from a nearby pond producing more than 500 little plant shoots. “I think it would be an

inexplicable circumstance if water-birds did not transport the seeds of fresh-water plants to vast distances,” he wrote.

Once a plant had become established in an isolated spot like an island in the Galapagos, Darwin felt that the “preservation of

favorable variations and the rejection of injurious variations” would eventually result in the origin of new species, a process he

termed “natural selection.” “I can see no limit to the amount of change, to the beauty and infinite complexity of the

coadaptations between all organic beings, one with another and with their physical conditions of life, which may be effected in

the long course of time by nature’s power of selection,” he wrote in the Origin.

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 6/8

Darwin did not go into detail about how the first seeds to reach Galapagos entered into this “struggle for life.” Almost 180 years

after his visit, however, there is plenty of evidence for such adaptation. One of the most telling observations, made in the 1980s,

is that the vast majority of flowering plants in the Galapagos are capable of self-pollination. Darwin would have loved this

observation and reveled in the explanation. If you have a fussy reproductive set-up, like a flowering plant that relies on a special

insect to carry pollen to a fellow member of your species, the odds of surviving on a remote island in somewhere like the

Galapagos are stacked against you. This also accounts for the fact that most flowering plants in the archipelago, with no need to

attract insects, are not particularly showy (white or yellow petals are the norm).

In fact, there is evidence of adaptation everywhere in Galapagos. Near the coast, we see plants that are tolerant of dry, salty

conditions. The red mangrove, for instance, is able to survive with specialized roots that can draw water from the sea without

bringing too much salt on board. The leaves of black mangroves also contain salt glands capable of shifting salt from the inside to

the outside of the plant.

Darwin’s collection of Galapagos plants proved to be a vital inspiration for his

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 7/8

Beyond the salty coastal region, the lowest reaches of each Galapagos volcano are dominated by the arid zone, where water—or

the lack of it—is the perennial problem. On Santiago, Darwin stuck a thermometer into some brown soil, and the mercury

rocketed up to almost 60 degrees Celsius (140 degrees Fahrenheit). It could have been yet still hotter, but Darwin’s thermometer

only went so far. It takes a certain kind of plant—usually with rather special roots—to survive in such a parched environment.

Take the prickly pear cacti of the genus Opuntia, for example. These have two kinds of roots: one superficial set of finer roots

whose job it is to suck up every last drop of water in the aftermath of a downpour, and a deeper “tap” root, which gives the plant

a stronger hold on the rocks and searches out deeper sources of water. Life in the arid zone is also easier if you are capable of

storing water, something that cacti are famous for. Their leaves, after all, have been so modified that we call them spines—and

these modifications are a perfect way to cut down on water loss.

During the cool season, between June and November, a cool mist hovers at between 500 meters and 1,000 meters above sea

level, creating a lush, moist zone, overrun with effulgent flora of an altogether different kind. When Darwin experienced the

transition from the arid to the humid zone, it struck him too. Landing at Black Beach on Floreana (where the small town of

Puerto Velasco Ibarra now stands), he walked about 8 kilometers inland, where he was thrilled “to find black mud & on the trees

to see mosses, ferns & Lichens & Parasitical plants adhaering.”

Darwin’s collection of Galapagos plants proved to be a vital inspiration for his ideas on evolution by natural selection. In 1837, his

bird specimens—particularly the Galapagos mockingbirds—alerted him to the possibility that the Galapagos flora and fauna

would be allied with the productions of South America, that there would be an extraordinarily high level of novelty, and that most

new species would be confined to a single island. But his failure to record the island of origin for many of his bird specimens

meant that they could not furnish him with the robust evidence to support or refute his suspicions.

Darwin’s Galapagos plants, however, were fit for purpose. Hooker’s initial assessment confirmed that the Galapagos flora was

indeed allied to that of South America, that there were lots of endemic species, and that many of these novelties seemed to be

confined to just one island. These conclusions reached Darwin in early 1845, just in time for him to weave them into the second

edition of his Journal of Researches. The chapter on the Galapagos ballooned to accommodate the new material and he became

bolder with his conclusions.

“Reviewing the facts here given,” he wrote, “one is astonished at the amount of creative force, if such an expression may be

used, displayed on these small, barren, and rocky islands.” And it was in direct response to Hooker’s findings that Darwin reached

the following, now-famous conclusion: “Both in space and time, we seem to be brought somewhat near to that great fact—that

mystery of mysteries—the first appearance of new beings on this earth.”

Henry Nicholls is the author of Lonesome George, which was shortlisted for the Royal Society Book Prize, and the forthcoming

The Galapagos. He lives in London.

Adapted from The Galapagos: a Natural History by Henry Nicholls. Available from Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books

Group. Copyright © 2014

ideas on evolution by natural selection.

1

21/9/2014 The Seeds That Sowed a Revolution - Issue 10: Mergers & Acquisitions - Nautilus

http://nautil.us/issue/10/mergers--acquisitions/the-seeds-that-sowed-a-revolution 8/8

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

2 Comments Nautilus Login

Sort by Newest Share ⤤

Join the discussion…

• Reply •

Ryan • 7 months ago

Great insight into the process Darwin used to understand the world.

"During the cool season, between June and November, a cool mist hovers at between 500 miles and 1,000 miles above sea level"

Surely that should be feet or meters? Otherwise we are talking about a cool mist twice as high as the space station! 4△ ▽

• Reply •

Quinn Canelias • 7 months ago

First time reading any article on Nautilus. Im glued. 4△ ▽

Subscribe✉ Add Disqus to your sited

Favorite ★

Share ›

Share ›

NEXT ARTICLE:

BIOLOGY

Top 5 Real Wolves of WallStreetBy Tim Requarth, Jason Stajich, Andreas Hejnol,

BIOLOGY

Evolution, You’re DrunkBy Amy Maxmen

BIOLOGY

In Search of the First HumanHomeBy Ian Tattersall

BIOLOGY

Evolution in a Finite WorldBy Sean H. Rice

RELATED ARTICLES:

ABOUT NAUTILUS PRIVACY POLICY

ADVERTISING AND SPONSORSHIP SUBSCRIBE

TERMS OF SERVICE CONTACT NAUTILUS

RSS AWARDS AND PRESS

NAUTILUS: SCIENCE CONNECTED

Nautilus is a different kind of science magazine. We deliver big-picture science by

reporting on a single monthly topic from multiple perspectives. Read a new chapter

in the story every Thursday.

© 2014 Nautilus, All rights reserved. Matter, Biology, Numbers, Ideas, Culture, Connected