The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

george-watson -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

2

Transcript of The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge

GEORGE WATSON 49

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge

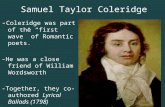

Once in age Coleridge was reminded of a student escapade by an old Cambridge friend, ‘an exploit of which he was the planner, and a late Lord Chancellor the executor’. The incident must belong to the years 1791-4, when he was an undergraduate at Jesus College.

A train of gunpowder was to be laid on two of the neatly shaven lawns of St John’s and Trinity Colleges, in such a manner that, when set on fire, the singed grass would exhibit the ominous words Liberty and Equality - which, with able ladlie dexterity, was duly performed.’

Coleridge’s turbulent undergraduate career lasted till the fall of Robespierre in the summer of 1794, an event he promptly greeted in a play written with Robert Southey. Wordsworth’s, at St John’s College, had belonged to an earlier period, from 1787 until January 1791, when he left Cambridge with a pass degree; and it touched the French Revolution only in its third year. But the event was more immediate upon him in its impact. Coleridge never visited revolutionary France. Wordsworth walked pcross it in the summer of 1790, with a college friend; and from November 1791 he spent thirteen months in Orl4ans, Blois and Paris, living through the September massacres of 1792, soon after the Convention had declared France a republic, and may even have returned to Paris in the autumn of 1793, if Carlyle’s claim in his Reminiscences (1881) is to be believed. In the Prelude he writes of things seen; Coleridge, in The fall of Robespierre and ‘France: an ode’, was content to use reports. The two poets were not to meet till 1795. But their minds ran in broadly parallel lines, and in lines already parallel before they met. Both supported a revolution, and what they understood to be the spirit of that revolution, in their early twenties, if not earlier ; both were to abandon that enthusiasm before the age of thirty. One, in age, was to become the active partisan of local conservative interests : the other a chief theorist and intellectual touchstone of British conservatism after his death.

Both, what is more, were to describe their early enthusiasms at length in middle life. Here, however, all similarity ends, and the evidence provides an instructively contrasting study in autobiographical candour. Wordsworth was to emphasise his changes of conviction, Goleridge to belittle and even deny his. Their case is doubly representative, then, and casts a long shadow forward to the revolutionary enthusiasms of twentieth-century intellectuals : more instruc-

)U Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

tively than Milton, a revolutionary who remained unrepentant to the end of his days; or Shelley, whose enthusiasm was always for a principle of revolution rather than for events. Wordsworth and Coleridge represent types more familiar to the modem mind. They were not pure utopians. They had their promised land, ahd could visit or study it. They welcomed a revolution in youth; watched it change, and themselves change; and found themselves moved, years later, to adjudicate between their conflicting memories of these events. Had France betrayed them, or they France? Wordsworth’s Prelude of 1805, and Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria (1817), largely written in the summer of Waterloo, pose these questions in anxious terms. Then a blanket of consoling amnesia falls, and the issue arises in their ageing minds only at moments of external pressure. Wordsworth continued to revise the Prelude at intervals until his death in 1850, the record of his French enthusiasm before his eyes, though changing before them; and Coleridge at Highgate could be visited by a contemporary of his student days, recalling to his memory a destructive trick with gunpowder he had never himself recorded and yet could not deny.

The question here is to consider, partly on new evidence, how the two principal records of their middle years - the Prelude and the Biographia - represent the probable facts of their early views. The issue is not chiefly one of mendacity, though it includes some wilful suppression. The contrast between the two poets is rather one of facing the truth of one’s early life or accepting a reassuringly selective interpretation. .If there are lies, they are best seen as lies of the heart; if deceptions, as self-deceptions. The disparity of the records is my chief source ; and argument proceeds on the assumption that autorial evidence contemporary to the event, or that of a witness with no motive for fabrication, rightly takes precedence over the poet’s o m later recollection.

The case of Coleridge may be considered first. Though the younger of the two poets by two years, he represents a simpler and more classic instance of disillusionment than Wordsworth; and tangled as the evidence is, it tells a story more familiar in outline to the modem mind.

The most recent evidence concems Coleridge’s account, in the tenth chapter of the Biographia, how at the age of twenty-three he came to write and sell The Watchman, a journal he composed in ten numbers from March to May 1796. Recalling gratefully the help of strangers nearly twenty years before, he adds:

They will bear witness for me how opposite.even then my prinaples were to those of Jacobinism or even of democracy, and can attest the strict accuracy of the statement which 1 have left on record in the tenth and eleventh numbers of The F r i e d .

The claim that chiefly bears on this in The Friend is Coleridge’s assertion that

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 51

his views were never revolutionary, but always in favour of the propertied classes :

I was never myself, at any perid of my life, a convert to the system. From my earliest manhood, it was an axiom in politics with me that in every country where property prevailed, property must be the grand basis of the government:

though he adds a qualification in favour of the freedom of property to circulate. Coleridge’s views by 1809 were already fiercely anti-democratic, and he was ardently convinced by his middle years that popular power could only mean a tyranny worse than that of kings: ‘The Temple of Despotism, like that of the Mexican God, would be rebuilt with human skulls, and more firmly, though in a different architecture’, he quotes approvingly. The Friend concedes no more than that some fashionable revolutionary fervour had once affected his youthful mind, though never a party loyalty or one that involved the membership of a secret society : ‘my little world described the path of its revolution in an orbit of its own’.

This account can now be challenged as seriously misleading. John Thelwall, who first met Coleridge in 1797 after an extended correspondence, and stayed with him at Nether Stowey in Somerset that summer at a time when both poets were under official surveillance as spies, was to mark his copy of the Biographia with indignant comments soon after it appeared in 1817; and none more indignant than at the point where Coleridge denied his youthful Jacobinism:

That IvIr Coleridge was indeed far from democracy, because he was far beyond it, I well remember - for he was a downright zealous leveller, and indeed in one of the worst senses of the word he was a Jacobin, a man of blood. Does he forget the letters he wrote to me (and which I believe I yet have) acknowledging the justice of my castigation of him for the violence and sanguinary tendency of some of his d~ctrines?~

Since Thelwall was already an eminent agitator in the 1790s, and was to remain a man of radical views, this assertion carries weight. Coleridge’s earliest surviving letters to Thelwell date only from April to June 1796, where he speaks of still holding ‘necessitarian’ views in moral matters, but announcing he has just ceased to be an infi+l, having been prejudiced against atheism by the example of William Godwin. That would date Coleridge’s conversion from extreme views to his twenty-fourth year. This is confinned by a letter of 1803, provoked by the execution of Robert Emmet; Coleridge calls twenty-four the very age at which he was himself ‘retiring from politics’, which in that context can only mean revolutionary politics5 But the same letter claims that he never ceased to be a Christian, since his speculative principles in youth were ‘a compound of philosophy and Christianity’. This can only be reconciled with his lettkr to Thelwall about the abandonment of infidelity in 1796 on one assumption: that Coleridge implies his views in the early 1790s were compatible

52 Critical Quurterb, vol. 18, no. 3

with Christia&y in a manner of which he was then unaware. Thelwall’s note suggests that Coleridge held ‘sanguinary’ notions for a year and more after leaving Cambridge in 1794. In the Biograpbia he admits himself to have been ‘conscientiously an opponent of the first revolutionary war’. Like Wordsworth, he sided with France in his heart after it had declared war on England in Febru’kry 1793; though he adds, less persuasively, that his eyes were always ‘thoroughly opened to the true character and impotence’ of the English revolutionaries of that age,

principles which 1 held in abhorrence (for it was part d my political creed that whoever ceased to act as an individual by malung himself a member of any society not sanctioned by his government forfeited the rights of a Citizen), a vehement anti- ministerialist, but after the invasion of Switzerland a more vehement antiGallican, and still more intensely an anti- Jacobin . . .

But it is highly unlikely that Coleridge held revolutionary principles in abhorrence as early as 1793. In ‘France: an ode’, a poem written in February 1798 for publication at the height of the French wars, he concedes that, when ‘Britain joined the dire array’ of monarchs against France in 1793,

Yet still my voice, unaltered, sang defeat To all that braved the tyrant-quelling lance,

And shame too long delayed and vain retreat! For ne’er, 0 Liberty! with partial aim I dimmed thy light or damped thy holy flame ;

But blessed the paeans of delivered France, And hung my head and wept at Britain’s name,

and the poem goes on, invoking the name of Helvetia, to ask forgiveness for having cherished ‘One thought that ever blessed your cruel foes’. Switzerland was invaded by the Directory in January 1798, but the ode makes no bones about the poet’s treasonable thoughts in earlier years. It is equally unlikely that Coleridge in youth held that members of illegal organisations were fair game for judicial punishment; though this claim, publicly made in the Biographia, repeats a similar suggestion in the letter of October 1803. The entire passage is carelessly casuistical, and to call oneself an anti- Jacobin after 1798 is to answer a charge no one was ever likely to make. A sti l l bolder attempt to alter the record of belief was to be made a year after the Biographia, in the expanded version of The Friend in 1818, when a Bristol address of February 1795 was inserted as evidence against an ‘infamous libel’ that he had ever been a Jacobin. Though his 1818 headnote claims that ‘the only omissions regard the names of persons’, any earnest student of the Conciones adpopulum (1795), from which

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 53

the text was borrowed, could have observed at the time the omission of about two hundred and fifty lines of inflammatory prose from the reprint, including a bitter attack on Pitt.‘ Coleridge’s very suppressions are wantonly executed: the Address, even as reprinted, includes a refusal to condemn the ends that Robespierre had in view.

More substantial because more contemporary evidence for Coleridge’s early convictions is to be found in The Fall of Robespiewe (1794), a play written with Robert Southey soon after the execution of the Jacobin leader in July 1794. Its dedication, which is plainly un- Jacobin in tone, speaks of Robespierre’s ‘great bad actions’ and of the ‘vast stage of horrors’ on which the two young poets have set the events of their play. Robespierre is represented as a blood-mad despot ; he is drunk with his own overpowering sense of virtue, and contemptuous of all freedom of debate, which he sees as a foreign plot against the revolution itself. But the play is as anti-monarchical as it is anti-Jacobin, and ends with a tirade by Barrkre, presumably written by Southey, calling on France to ‘liberate the world’ now that she has freed herself. This puts Coleridge’s middle-aged claim never to have been a Jacobin in clearer perspec- tive; his views may have been similar to the Jacobin or, as Thelwell insisted, even more bloodthirsty, and yet independent of party allegiance and suspicious of Robespierre’s personal ambitions. If so, it is a tightrope-walk of an argument that reminds one of Andre Gide’s attitude to Stalin in his Retour de I’Urss (1936). Coleridge’s writings of 1795 help to confirm this view. They praise Brissot, the Girondin leader guillotined in October 1793, as a ‘sublime visionary’ who proved ‘unfit for the helm in the stormy hour of Revolution’ ; and contrast him dispassionately with Robespierre, who never forgot the ends of revolution but lacked scruple over the means:

What that end was, is not known: that it was a wicked one, has by no means been proved. I rather think that the distant prospect to which he was travelling appeared to him grand and beautiful; but that he fixed his eye on it with such intense eagerness as to neglect the foulness of the road. ’

The rest of Coleridge’s argument here then anticipates Wordsworth’s in The Borderers, a play probably begun in the following year: their minds must have been wonderfully in harmony in 1795, when they first met. Idealism, Colendge goes on to argue, is the mother of the blackest political crimes : ‘The ardor of undisciplined benevolence seduces us into malignity: and whenever our hearts are warm, and our objects great and excellent, intolerance is the sin that does most easily beset us.’ This was said in February 1795, and it is plainly the remark of an ex-revolutionary, though not necessarily of an ex-radical. In October 1796, writing reassuringly to the father of a friend, he declared ’

54 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

himself to have ‘snapped my squeaking baby-trumpet of sedition’ , hanging up ‘its fragments in the chamber of penitences’ - a phrase he was to :‘peat nearly two years later,’in March 1798, in a letter to his brother George. From Nov- ember 1797 he was to contribute essays to the Morning Post in favour of parliamentary reform and against the French war and the taxes it occasioned: ’ anti-ministerial journalism, indeed, but no longer based on a fervour that could be called revolutionary.

There is contemporary evidence, then, that, Coleridge held extreme and probably violent political views in the Cambridge years of 1791-4 - extremer, if Thelwall is to be believed, than those of the Jacobins themselves - though probably without joining any revolutionary society or group; that by 1794-5 he could perceive the dangers of that position, though he still counted himself enough of a revolutionary to support France against England in war; that the middle or late months of 1796 show a return to Christianity, in some qualified sense, though still accompanied by necessitarian views about the moral order; that his journalism of 1797 and after shows him still in some sense pro-French, or at least anti-war, though on essentially practical grounds; and that only late in 1799 did he show himself to be anti-bapartist, $?ugh he continued at times to express an admiration for Napoleon’s genius. . Sara, his daughter, was later to call Napoleon ‘the plank or bridge’ across which Coleridge was to pass from French sympathies into hostility. In short, Coleridge ceased to be a revolutionary in or by 1795; and his conservatism, marked by his withdrawal of opposition to Pitt’s government, largely dates from 1798-9.

The problem of Wordsworth’s early convictions is at once subtler in its demands upon the historian than Coleridge’s, and wider in its implications. In his early and middle years, it seems likely, his political interests were even more intense than Coleridge’s, and decidedly more continuous; though he did not consume his later years, as his friend did, in writing political treatises. Coleridge never visited revolutionary France : Wordsworth visited it twice , and perhaps thrice, in 1790-3, his second visit lasting for more than a year. His steadily burning passion for a new political order easily outdistances the pantisocracy of Coleridge and Southey in its inward intensity: it was never merely utopian, being based on a France that he lived in and knew, and his deep communion of friendship in the spring and summer of 1792 with Michel Ekaupuy, a high-minded young French officer in the Loire valley, still warms the Prelude of 1805. Many years later Wordsworth was t6 remark to an American visitor that, though known to the world only as a poet, ‘he had given twelve hours ’ thought to the condition and prospects of society , for one to poetry’.” His mind was less purely literary than Coleridge’s: it certainly dwelt less patiently and. persistently on the conceptual problems of literary

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 5 5

debate; and his dismissive comments on Coleridge’s Biograpbia and its elaborate musings on the proper language of poetry were to show how little he esteemed the extensive rarefications of critical analysis. Wordsworth’s is a mind of intense and unstinting political sensibility: of sensibility rather than than of sense, one might add, since it is almost always the victim rather than the agent of political events. It reacted strongly, even fiercely, to the headlines of the day. It always licked the serenity essential to the highest political intelligence, like Burke’s, and to effective political action. It was easily indignant, and susceptible to panic; distant always from the ‘wise passiveness’ that it proposed to itself and the world as an ideal; and the stoical acceptance of death by the child in ‘We are seven’, or of suffering by the Leechgatherer in ‘Resolution and independence’, were forever remote and unattainable to the poet himself. This is the supreme literary instance in English of those obsessed and anxious minds that write angry letters to the editors of newspapers. The Convention of Cintra (l809), a long prose tract attacking what he saw as the betrayal of the Portuguese allies of England, is a characteristic effusion, though now little read; so are his late sonnets fulminating, fourteener by fourteener, against momentary evils at home and abroad. His mind was politically specific: it was stirred by events that had occurred as much as by ideas, and by what it heard and felt. The faces.he saw about him when he landed at Calais in July 1790,

when joy of one 1s joy of tens of mil l ions ,I2

and kaupuy’s ever-remembered remark to him, two years later, as he pointed to a starved country girl:

’Tis against that Which we are fighting’

(IX. 518-19)

- such specificities are the constant element in a political enthusiasm other- wise fast-wavering and unfixed. Utopia is a place that does not. exist. But Wordsworth loved places that he knew. His search for serenity was always a quest and never a finding, where the

loved object or landscape can offer no more than a temporary stay against anxiety. But some, and perhaps most, of the eternal restlessness of his greatest poetry, and its perpetual yearning for consolation - ‘I long for a repose that ever is the same’ - starts from out of a sense of loss for a world he had once lived and known, a France

56 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

standing on the top of golden hours, And human nature seeming born again.

(VI. 353-4)

Wordsworth is the Adam of his own epic, as doubtfully heroic as the hero of Milton’s poem. Unparadised more than once, he must forever seek a com- pensating reward in the memory of a child’s world that was his before the enthusiasm of revolution swept it away. This helps to explain the Miltonic echoes in The Prelude, which are exceptionally abundant in its first book. By the late 179Os, when he began to write it, the poet had already lost that Eden ; and his opening declaration, ‘The earth is all before me . . .’ (1.15) is an evident echo of the thought Milton plants in the minds of Adam and Eve in the last lines of Paradise Lost, as they are driven forever from the Garden: ‘The world was all before them, where to choose.’ The Prelude begins where Paradise Lost ends. But only its first book echoes Milton strongly, since the poem is less an epic in itself than an apology for being unable to write one:

If my mind, Remembering the sweet promise of the past, Would gladly grapple with some noble theme, Vain is her wish; where’er she turn she finds Impediments from day to day renewed.

(I. 137-41)

The impediments are those memories of specific events, of places and people, that obsess too profoundly and too insistently to permit the philosophic poem urged on him by Coleridge to arise; so that the Prelude is a ground-clearing operation, in the poet’s own view, for a building yet to be planned. Its very scale and shape are still unsure:

Sometimes, mistaking vainly, as I fear, Proud spring-tide swellings for a regular sea, I settle on some British theme, some old Romantic tale by Milton left unsung . . .

(r. 177-80)

and there follows a list of possible epic subjects, medieval, classical and Norse. The Prelude itself, as Wordsworth knew, is no regular sea; and the gap between the shapely narrative of Purodise Lost, moving towards a known and predestined close, and the indeterminacy of a verse autobiography is meant to be noticed. That is not only because most of Wordsworth’s life is still to be lived. It is because liberal man is himself newly created, and no one can be sure

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 57

what the demands of freedom can mean. ‘The present generation’, wrote Tom Paine in 1792, in The Rights of Man, ‘will appear to the future as the Adam of a new world.’ That remark now looks truer than Paine knew. Wordsworth had lost two paradises by the time he came to write the first complete version of the Prelude in the years between 1799 and 1805: a political paradise in revolutionary France, and a sensory paradise of youth as well. He is a twofold Adam. Recollection survives in layers, and the layers must be lifted gently, one by one. And yet the poem - or at least the first ten of its thirteen books - is written in an order the reverse of this, or the order o€ time itself. In so elaborate a dislocation and with so much self-knowledge and self-justification at stake, it is unsurprising if its movement is spasmodic and insecure.

Wordsworth has often been called a Girondin, partly on the evidence of his friendship with Michel Beaupuy described in the ninth book of the Prelude, and commonly with the implication that he was never more than a moderate revolutionary. His nephew Christopher Wordsworth, in his Memoirs (1851), claims he was ‘intimately connected’ with the followers of Brissot, but gives no details 0.77). His residence in France, in the second and longest visit, began in November 1791, when Robespierre and Brissot were about to take up positions as rival leaders of Jacobins and Girondins in the new Legislative Assembly ; and it continued through the declaration of war on Austria in April 1792,. the dismissal of Roland and his colleagues in June, and the suspension of the monarchy in August, followed by the Prussian invasion ; the prison massacres and the abolition of the monarchy followed in September. On 29 October Wordsworth arrived in Paris from the h i r e on the very day when Louvet, the Girondin, accused Robespierre in the Convention of dictatorial ambitions. Weeks after Wordsworth’s return to England in December, compelled by lack of money, the King was executed; and war was declared on Great Britain and Holland on 1 February 1793 - an event which, as Wordsworth unashamedly records in the Prelude, filled him with rebellious despair and passionately treasonable thoughts.

The account of these events in the ninth and tenth books of the 1805 Prelude is strikingly honest, in the sense that Wordsworth (unlike some of his biographers) makes no claims for his own moderation or good judgment, though much for the understanding forgiveness of the reader. It is important to recall here that the PreZiu(e was never published in Wordsworth’s lifetime, and that this aspect of the poem represents an explanation made to intimates - notably to his sister Dorothy and to Coleridge, to whom the poem is jointly addressed - and above all to himself. It was not for the common reader. Wordsworth represents his revolutionary enthusiasm in those years as total, and their cause as youthful inexperience, but in no sense subject to mental reservations; and he strongly implies that he was noisy and extreme in political

58 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

arguments :

I was led to take an eager part In arguments of avil polity, Abruptly, and indeed before my time,

and this out of an excess of idealism:

I had approached, like other youth, the shield Of human nature from the golden side, And would have fought, even to the death, to attest The quality of metal which I saw.

(X. 660-6)

So his own claim is that he was once ready to kill or to die for the revolutionary cause. What is more, Wordsworth’s Girondin associations no longer seem the probable evidence for moderation that they once were. It is admittedly difficult to know how to interpret the evidence here, since the modern historian’s understanding of the Girondin party may not be altogether like the young Wordsworth’s. He had lived in France, and mainly in provincial France, as a dedicated young political idealist aged twenty-one and twenty-two. What he understood of the flux of French revolutionary politics in the last year or less of a brief and fragile experiment in constitutional monarchy and the first three months of the first French Republic can only have been mediated to him, accurately or inaccurately, by what he heard and overheard in hostile royalist circles in Orl6ans and Blois or from the sympathetic conversations of men like Beaupuy. Recent studies suggest that the Girondins had little unity as a party, though they were perhaps philosophically united in a vague version of eighteenth- century Deism, as well as in anti-clericalism and a general attitude of ‘reasoned secular toleration’. ” They were philosophes in politics, the intellectual heirs of Condorcet, Voltaire and D’Alembert. Coleridge describes them in much the& terms in the Bristol lectures of 1795. Nothing in the contemporary and surviving evidence of Wordsworth’s mind in the early 1790s does much to confirm this account, and in any case it looks too sketchy an allegiance to count for much. The paean of praise for revolution that ends his Desm9tiue Sketches (1793), a poem written in the France of 1792 and celebrating the declaration of a republic‘in September, has a sternly military ring. It is the cry of a people in arms, rejoicing in the ‘three-striped banner’ of a new state dedicated to war, where

martial songs have banished songs of love, And nightingales desert the village grove,

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 59

Scared by the fife and rumbling drum’s alarms, And the short thunder, and the flash of arms.

01.614-17)

This is a state resisting a foreign invasion, to be sure. But it is still unlike the poem of a young philosophe :

But foes are gathering - Liberty must raise Red on the hills her beacon’s far-seen blaze . . . ,

0.638-9)

and the new world is seen only on the far side of a sea of blood: ‘Lo, from the flames a great and glorious birth’ when every monarch, or ‘sceptered child of clay’, has been swept away by providential anger, to ‘Sink with his servile bands, to rise no more.’ This is the outpouring of a twenty-two-year-old republican ideologue who sees all political action as a battle between despots and populace, and one where God and the future support the popular cause in a struggle necessarily violent. If this is not exaaly incompatible with the world of the philosophes, the emphasis is plainly and continuously different: more ardent, more martial, and more instant in its demand for action. Girondin is not clearly the right word to describe such a state of mind, which reminds one less of Voltaire than of Washington, Blake or Paine. At all events, it is not remotely a moderate view.

The extremity of Wordsworth’s views grow clearer if set beside the prose evidence of his Letter to the Bishop of Lkznabff, which he wrote, but failed to publish, in February and March 1793, shortly after his return to England. The conclusions of the most recent editors of this tract are persuasive: that Wordsworth’s debt to seventeenth-century English writers such as Milton, James Harrington and Algernon Sydney, who were fashionable reading in the revolutionary Paris of his residence, play only a small part in the Letter; and that Godwin’s Political Justice, which appeared in late February 1793, , represents a view distant from that of the yyung poet - and one too late, in any case, for him to have mastered in time . But then the attempt to see the Letter in a tradition of English political thought was always over-ingenious - especially since Wordsworth, on his own telling, was a highly anti-patriotic yowg man. The work was designed as a pamphlet in defence of a France in arms, and by then in arms against England; and its arguments are French. The manuscript suggests it was to have been published anonymously as ‘By a Republican’. That it was never published in Wordsworth’s lifetime - whether because events in France itself gave him pause, or because his publisher thought it imprudent - does not weaken its interest as evidence. The young poet has just returned from the fresh young republic of his dreams into a hostile

60 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

and suspicious homeland. His reaction is extreme, and it includes a defence of revolutionary violence - if not for its own sake, at least as a natural extravagance of a people too long in chains:

The animal just released from its stall will exhaust the overflow of its spirits in a round of wanton vagaries, but it will won return to itself and enjoy its freedom in moderate and regular delights ,u

he admonished a bishop of conservative temper. The argument was to be heard again, more than a century later, among those eager to excuse the excesses of Russian and German dictatorships in the 1930s. It is the classic defence of immaturity; and one which, by the mid-l790s, was to be inverted into a critique of revolution, when the very argument that had served Wordsworth in an enthusiasm for France was to quicken his hostility against it.

That argument-by-inversion is offered, obscurely enough, in Wordsworth’s only play, The Borderers, a blank-verse tragedy set in thirteenth-century England. He probably began to write it in the autumn of 1796, on settling at Racedown in Dorset, and it has traditionally been seen as a study of Godwin’s doarine of benevolence viewed through the character of the villain Oswald, who leads an innocent into evil. The argument is surely more interesting than that, and more directly attuned to Wordsworth’s earlier convictions. Godwin’s diaries have recently revealed that Wordsworth visited him nine times in London betwen Feb- and August 1795, usually unaccompanied1’; and the Political Justice is admittedly a plea for reform, and especially educational reform, as a soberer and more humane instrument of change than revolution. All this fits Wordsworth’s interests in the 1790s too well to be dismissed as at least a contributory influence. But the most acute critical comment on The Borderers, a work so opaque as scarcely to exist except in the light of its commentaries, was one made by Wordsworth himself half a century later, in a preface written for its fmt publication:

The study of human nature suggests this awful truth, that, as in the trials to which life subjects us, sin and crime are apt to start from their very opposite qualities, so are there no limits to the hardening of the heart and the perversion of the understanding to which they may carry their slaves.

This apperception, which by 1796 was already Coleridge’s, is a more funda- mental critique of revolution than anything in Political Justice ; and if ‘it can fairly be read back into Wordsworth’s mind in 1796-7, then it seems probable that he abandoned his revolutionary faith because he had come to see that it is precisely the idealist who is the supreme political criminal, or at least criminal-

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 61

in-the-making. Albert Camus was to confer a wider argumentative dignity on the same contention in his L’Homme rdvoltb (1951), a work written soon after the opening of the Nazi extermination-camps in 1945. Only the hero of abstract revolutionary convictions like a Robespierre or a Hitler can commit the meme logiqile, which is vaster than any merely private or selfish act. If men stole and killed only selfishly, then they would steal and kill seldom. But the utopian kills for all mankind, and there is no limit to what he may destroy. The French Terror of 1793-4 is the greatest monument to political idealism in Wordsworth’s lifetime, as Auschwitz of our own. And the revolutionary animal, as Wordsworth had come to see by the mid 1790s, does not go quietly back to its stall. If he visited Paris for a third time late in 1793, a matter still uncertain, he may have known this truth on the evidence of his own eyes.

It was ‘logical crime’ that drove Wordsworth, it seems likely, from the creed of revolution. And it drove him towards an enduring belief in habit, nurture and education. In a fragmentary ‘Essay on morals’, which he may have written before he was thirty, and most probably in Germany late in 1798, he criticises Godwin and Paley for failing to notice that ‘all our actions are the result of our habits’.’’ A man is not made or remade for an historical moment, like Robespierre’s inauguration of the Age of Reason. He is the sum of what he has been. There is no new humanity, and no new age. The Prelude, like any penetrating autobiography, attempts to total up the reckoning of experience and to reactivate it in the author’s mind: an account of vital memories, or ‘spots of time’, upon which in future years to draw. The very exercise of writing it was itself unrevolutionary, in that sense, since it set a youthful political enthusiasm into a wider spectrum of sensations and beliefs that begin with childhood, and diminished it from the whole to a part. Like many revolutionaries, Wordsworth in his middle years suffered a mental change that allowed some of the assumptions and interests of early youth to return and inhabit a mind emptied of its ideal sympathies. But in this case the return did not obliterate. The Wordsworthian hero is heroic by virtue of what he can endure as rememberance.

Wordsworth wrote little in the years 1793-5, or little that has survived: a fact that makes his mental progress during and after the French Terror so much the harder to document. The evidence of 1790-3 shows a young poet sympa- thetic to a revolution, and soon passionately dedicated to it, even to the point of treason; from 1796 the evidence of disillusion is clearly there, though not always clearly interpretable. Coleridge’s share in The Fall of Robespierre in 1794, and his lectures of 1795, make a similar transition easier to document. He represents the Terror as no more than a brief perturbation in the march of human progress: one that raises disquieting questions, indeed, about the consequences of untrammelled political idealism, but not before 1795 of a kind to discredit either revolutionary ideas in themselves or their dissemination

62 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

among mankind. Coleridge must still have been some kind of radical idealist in the summer of 1795, when he first met Wordsworth, though his breach with Southey over the project of a settlement in Pennsylvania based on pantisocratic principles had already begun. The minds of both men, at that first Bristol meeting, may have been at or near a point of withdrawal. If so, their friendship is the easier to understand. They must have helped each other, in the few marvellously fertile years that elapsed before their departure for Germany in !+ptember 1798, to descend from the revolutionary heights into humbler moods of self-examination and self-doubt. The Lyrical BalZaa’s is part of the record of that descent, though a record of taxing obscurity.

In later life, and notably in a letter of 1821, Wordsworth was inclined to name Napoleon’s invasion of Switzerland as his moment of disillusion; and there has been scholarly disfyyeement as to whether this refers to the invasion of 1798 or to that of 1802. In the Prelude of 1805, what is more, he refers bitterly to the transformation of France itself, without pretending that the change of conviction lay anywhere but withii himself:

And now, become oppressors in their turn, Frenchmen had changed a war of self-defence For one of conquest.

,

(X. 792-4)

Indeed he volunteers, and with a frankness uncharacteristic of the literature of disillusionment, an admission that the ugly truths of what revolution meant forced him into ever noisier and more absolute protestations of loyalty to the cause. Wordsworth does not plead ignorance, and he does not plead as an excuse that it was France that changed rather than himself. The poem, after all, is about the growth of a poet’s mind - and growth means change:

I read her doom, Vexed inly somewhat, it is true, and sore, But not dismayed, nor taking to the shame Of a false prophet; but roused up, I stuck More firmly to old tenets, and, to prove Their temper, strained them more; and thus, in heat Of contest, did opinions every day Grow into consequence, till round my mind They clung, as if they were the life of it.

(X. 797-805)

This is a memorably outspoken admission of intellectual obstinacy. If, as the editors believe, it refers to 1794-5, then one must imagine the Wordsworth of

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 63

his mid-twenties, in London or on his return north, to have been vociferously pro-French in an England already in the second and third year of war, and one listening in daily horror to reports of the French Terror and its aftermath. So Wordsworth’s revolutionary sympathies spanned the period of the Terror and were held in the knowledge of the Terror. The candour of the tenth book of the Prelude, seen in these terms, is breathtaking. It was written, moreover, less than ten years after the state of mind that it describes, and was not to be substantially altered in these-respects in the revised version of 1850. The frankness of this book can only be understood on the assumption that Words- worth was ready to offer his own youthful errors to himself and his intimates as a warning example. He even concedes an ambition of that time to become an active revolutionary, presumably by taking up arms :

Yet would I willingly have taken up A service at this time for cause so great, However dangerous

(X. 135-7)

having already found himself to be incompetent as an orator, and conscious

How much the destiny of Man had still Hung upon single perms.

Does this hint at a readiness to assassinate? It is hard enough to imagine Wordsworth in the role of a tyrannicide or even of a saboteur ; but these must have been among the desperate thoughts then inwardly revolved.

Much of the scholarly debate, then, concerning which national events precipitated Wordsworth’s change of heart fails to take the literary evidence into account. Wordsworth, in these passages, plainly denies that the atrocities of 1793-4 had a disillusioning effect upon his spirit. In fact they stiffened his resolve. His mind was eager to justify a political terror, as the b t t e r to the Bishop of Ua?zu!afdemonstrates, and it was already possessed of that justification early in 1793, before the extremer courses of the Terror had begun. Revolutions, in that view, may have to devour their enemies as a preparative to the reign of universal happiness to come; and those who exploit a horror of violence, like the Bishop, in order to discredit revolution have set themselves up in opposition to the chief, indeed the only, hope of mankind. Such was the declared judgment of Wordsworth in his early and-mid twenties; and such was his account of his mind even after he had ceased to believe.

There is positive evidence, in short, that Wordsworth’s disillusionment was philosophical rather than historical: that it amounted to a dissatisfaction with

64 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

doctrines of utopian liberalism rather than with events. That could still leave a contributory influence to the self-aggrmdising policies of the Directory of 1795-9 and of Napoleon as First Consul and Emperor. It would represent a rare, and perhaps unique, event in Wordsworth’s intellectual life: a movement of mind occasioned less by a specific happening such as an invasion or a treaty than by a deep shift of ideological faith. But then the revolutionary passion, unlike the rest, had been all-consuming: Wordsworth in the Prelude even confesses how the campaign against the slave trade in the 1790s had failed to interest him, since he could believe in ‘only one solicitude for all’, or the success of France (X. 229). The poem celebrates a return to specificities:

There is One great society alone on earth, The noble living and the noble dead

(X. 968-70)

The uniqueness of this change of heart in the total movement of his mind has not been clearly recognised, partly because of the paucity of evidence in the vital years of shift between 1793 and 1795, and partly because of the understandable neglect of the immature works that immediately follow, Gilt and Sowow and The Borderers. But the silence of those years is not hard to understand. Oswald, in The Borderers, speaks of the ‘after-vacancy’ that follows violent action, when ‘We wonder at ourselves, like men betrayed’. Words- worth is not known to have committed a violent act, or even to have disfigured a college lawn. But it is certain, and on his own telling, that in the years of the Terror he suffered a crisis of painful emotion that involved the guilt of complicity. Coleridge was to speak of his own ‘chamber of penitences’, and his symbol of the Ancient Mariner with a slaughtered albatross hung for shame around his neck could have fitted either poet by the last years of the dying century. Adam had indeed sinned and been sent forth to wander. The difficulty lay in explaining to mankind what paradise had been like: to those who have not lived through a dawn of civic bliss, it is something next to impossible to explain, especially to a fallen world. A few years after writing the ‘Mariner’, in 1803, Coleridge was to dream how

Adam travelling in his old age came to a set of the descendanbl$ Cain, ignorant of the origin of the world; and treating him as a madman, killed him.

Both poets, by then, had reason at once to expect and to fear the incredulity of man. Though politically disenchanted, they were always to remain more firmly rooted in enchantment than the generality of mankind. A mastery of the art of

The revolutionary youth of Wordsworth and Coleridge 65

remembering was itself a guarantee of that. The moment of art had come. Wordsworth’s loss of revolutionary faith, like Coleridge’s, occurred, and was complete, before he became a great poet; and ‘Tintern Abbey’, the Immortality Ode and The PreZude exist in the lengthening shadow of that great change : acts of expiation almost unique in the literature of disillusionment in their honest witness to a total and outspoken faith.

Notes

1

2

3

4 5. 6

7

8 9

10

11

12

James Gillman, The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (London, 1838) pp. 49-50. Gillman was Coleridge’s landlord and doctor at Highgate, and must have heard him being reminded of the affair by a visitor. The future Lord Chancellor can only be John Singleton Copley, Lord Lyndhurst (1772-1863), Chancellor in 1827-30 and twice after. He enjoyed a lifelong reputation for high spirits, and Crabb Robinson in his DMry @I. 402) tells how he chalked ‘Frend forever’ on a Cambridge wall in support of his mathematics tutor William Frend, deprived of his Jesus fellowship in 1793 for revolutionary sympathies. Trinity must have remained unaware of his part in damaging their lawns, as they shortly elected him into a fellowship. Coleridge, The Friend, edited by Barbara F. Rooke (London, 1969) II. 146, from the eleventh number (26 October 1809). Burton R. Pollin, ‘John Thelwall’s marginalia in a copy of Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria’, Bulletin of New York Public Library (February 1970). See my revised edition of the Biographia (hndon, 1975) pp. xxiii-xxiv, 100. Here and elsewhere, in quoting from notes and letters, I have normalised texts and silently expanded contractions. Coleridge, CollectedLetters, edited by E. L. Grigss (Oxford, 1956-71) I. 204f., 221. Ibid., II. 999. These are detailed in foomotes by Barbara Rooke, the most recent editor of The Friend (1%9), I. 326-38.

Coleridge, Lectures 1 795 on Politics and Religion, edited by Lewis Patton and Peter Mann (Lmdon, 1.971), p. 35, from Conciones adpopulum (Bristol, 1795); reprinted with omissions in The Friend of 1818. Coleridge, CollectedLetters (1956-71), I. 240, 397. David V. Erdman, ‘Coleridge as editorial writer’, in Power and Consciousness, edited by Conor Cpise O’Brien and W. D. Vanech (1969), pp. 184f. Coleridge’s contri- butions to the Morning Post in 1797-1803 were considerable: they comprise some 134,000 words of prose and about 3,000 lines of verse. See Edward P. Thompson, ‘Disenchantment or default?’, in Power and Conscious- ness (1969). Thompson, writing before the publication of Thelwall’s marginalia to the Biographia, argues that the creative moment of both poets was not political disillusion- ment itself but rather a point of mental conflict before that. The dates hardly support that conclusion, though they allow the view that the agony of disillusion was a recent enough fact to be an active principle in Lyrical Ballads and in poems written soon after. Rev. Orville Dewey, The Old World and the New: or a Journal (London, 1836), I. 106. William Wordsworth, The Prelude: A Parallel Text, edited by J. C. Maxwell

66 Critical Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3

(Penguin, 1971), book VI, ll. 359-60 (text of 1805). Future references are to the 1805 text in this edition. M. J. Sydenham, The Girondins (London, 1%1), p. 191. W. J. B. Owen and Jane W. Smyser, The Prose Works of William Wordsworth (Oxford, 1974), I. 23-4. This convincingly answers F. M. Todd, Politics and the Poet, who makes less of Paine’s influence and argnes that the Letter ‘contains litt le that i s not in Godwin’ (p. 60). Prop Work (1974), I. 38. Mary Moorman, Willion Wordsworth, a Biography: The Early Yeors, 1770-1803 (Oxford, 1957), p. 262 and note. Geoffrey Little, ‘An incomplete Wordsworth essay upon moral habits’, Review of English Literature, 2 (1961); first collected in Owen and Smyser, Prose Works (1974), I. 103. J. C. Maxwell, ‘Wordsworth and the subjugation of Switzerland’, Modern Languuge Review, 65 (1970). Notebooks of Coleridge, edited by Kathleen Cobum (London, 1957- ), No. 1698.

13 14

15 16

17

18

19

firs' @a$keII edited by J A V Chapple and Arthur Pollard €9.00

‘Altogether she was a remarkable woman of whom, thanks to the diligence of Messrs. Chapple and Pollard one can form an exceptionally clear and detailed picture‘. So wrote Malcolm Muggeridge in the Observer when The Letters of Mrs Gaskell first appeared. Ten years later the book still commands great interest: Margarer Lane in The Daily Telegraph draws readers‘ attention to Mrs Gaskell’s ’irresistible letters . . . the huge Chapple and Pollard edition which appeared ten years ago and revealed her as one of the most delightful women of all time.’ A collection of all the letters available written by Elizabeth Gaskell between 1832 and 1865 and arranged chronologically, the book extends some 1000 pages. Far from being a formal letter writer, Mrs Gaskell’s pen flowed with a spontaneity of style that makes delightful reading: her subjects range from day-to-day famity affairs to literature, travels abroad, current events and progress on her own novels, and apart from family and publisher, among her correspondents were some of the leading literary figures of the day - Elizabeth Barren Browning, for example, John Ruskin and Leigh Hunt. Letters concerning her friendship with Charlotte Bronte are especially illuminating. The editors have included a full introduction, and appendices give biographical sketches of many of the contemporaries to whom she wrote.

MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL.