The relationship between trusting beliefs and Web site loyalty: The moderating role of consumer...

-

Upload

reetika-gupta -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of The relationship between trusting beliefs and Web site loyalty: The moderating role of consumer...

The Relationship BetweenTrusting Beliefs and WebSite Loyalty: The ModeratingRole of Consumer Motivesand FlowReetika GuptaLehigh University

Sertan KabadayiFordham University

ABSTRACT

This research (1) examines how specific consumer motives (i.e., goal-directed: searching for information, experiential: browsing for recre-ation) influence the trusting belief–loyalty relationship at a Web site ina distinct manner and (2) investigates how the online flow experiencein each of the motive states strengthens or weakens the trustingbelief–loyalty relationship. The results suggest that for consumerswith an experiential motive, benevolence- and integrity-related beliefsare the key drivers of loyalty, while ability-related beliefs do not driveloyalty. On the other hand, for consumers with a goal-directed motive,the ability- and integrity-related beliefs are the key drivers of loyalty,while benevolence-related beliefs are not influential. Further, thisresearch illustrates that when consumers with an experiential motiveexperience a high level of flow, the impact of trusting beliefs on loyaltyweakens. However, for consumers with a goal-directed motive, trust-ing beliefs continue to exert the same impact on loyalty across bothhigh and low levels of flow. © 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 27(2): 166–185 (February 2010)Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com)© 2010 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. DOI: 10.1002/mar.20325

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

167

The notion of loyalty has become an important construct within the e-businessframework because of consumers’ easy switching behavior on the Web (Crockett,2000; Rodgers, Negash, & Suk, 2005; Tsai et al., 2006). Both academics andpractitioners agree that building loyalty is not only an important strategy butalso a necessity for companies operating on the Internet (Reichheld & Schefter,2000; Yang & Peterson, 2004; Yoon, Choi, & Sohn, 2008; Zhao, 2001). Trust hasbeen shown to be a key determinant of loyalty in offline and online environ-ments (e.g., Berry & Parasuraman, 1991; Doney & Cannon, 1997; Kabadayi &Gupta, 2005; Papadopoulou et al., 2001; Shankar, Urban, & Sultan, 2002). Sev-eral studies indicate that trust plays a key role in creating satisfied and expectedoutcomes in online transactions (Chen & Barnes, 2007; Pavlou, 2003; Wu &Cheng, 2005). However, studies investigating the trust–loyalty relationship havetreated trust as a unitary concept. Recently, researchers have advocated that trustcomprises two dimensions, trusting beliefs and trusting behavior (e.g., Mayer,Davis, & Schoorman, 1995; Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006;Yousafzai, Pallister, &Foxall, 2005), suggesting that the trust–loyalty relationship at a Web site shouldaccount for this multidimensional nature of trust. Several studies have exam-ined the effectiveness of signals or tactics at a Web site (e.g., security state-ments, design-based investments) in the formation of trusting beliefs and theirresulting influence on various online behaviors such as consumers’ intentions toshare personal information with a Web vendor (Aiken & Boush, 2006; McKnight,Choudhury, & Kacmar, 2002) or to purchase products (Schlosser, White, & Lloyd,2006). However, the relationship between consumers’ trusting beliefs and loy-alty toward a Web site has remained unexplored.

This research examines how the relationship between distinct trusting beliefs(i.e., ability, benevolence, and integrity) emerging from elements in a Web siteand loyalty toward a Web site varies across distinct consumer motives for vis-iting a Web site. There is a stream of research to suggest that motives such as“goal-directed” (e.g., searching for specific information) and “experiential” (e.g.,browsing for recreation) persuade consumers to focus on completely differentaspects of the Web site, leading to varied effects on evaluations and purchaseintentions at a Web site (Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Schlosser, 2003; Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006). This difference in focus suggests that these two motiveslead consumers to pay attention to distinct signals and tactics used at a Web siteand therefore rely on distinct trusting beliefs, based on these signals, when mak-ing loyalty decisions (i.e., revisiting and spending more time) at the Web site. In addi-tion, drawing on the theory of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975, 1990) used by Internetresearchers to denote a compelling navigation experience (e.g., Mathwick &Rigdon, 2004), this research investigates if the level of flow in each of the motivestates strengthens, weakens, or has no effect on the trusting belief–loyalty rela-tionship at a Web site.

This research has implications for theory and practice. In terms of theorydevelopment, it extends research examining the trust–loyalty relationship by examining each of the specific trusting beliefs and their influence on loyaltytowards the Web site in each of the two motive states, goal-directed and expe-riential. Additionally, this research explores the role of flow in influencing thetrusting belief–loyalty relationship. Finally, a number of these constructs (e.g.,goal-directed and experiential motives, flow) have been explored independentlyor within other contexts; this research presents them together at a combinedlevel to better understand how the trusting belief–loyalty relationship varies in

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

168

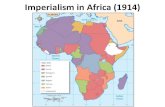

distinct online settings (see Figure 1). From a practitioner’s view, if marketerscan determine the motives of consumers’ Web visits through survey or consumerprofiling, it is possible to tailor the signals and tactics at a Web site to match theconsumer motives and ensure positive loyalty outcomes. Also, understandingthe influence of flow on the trusting belief–loyalty relationship can help mar-keters devise strategies to maximize the flow experienced at their Web sites,thereby compensating for consumers’ low level of trusting beliefs.

Below, the paper proceeds with a literature review on trust and loyalty. Next,it presents hypotheses, research method, and empirical analyses. It concludeswith a discussion of the findings, their implications for managers and researchers,and future directions for research.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Web Site Loyalty

Researchers investigating loyalty in a traditional brick-and-mortar environ-ment have asserted that loyalty constitutes both behavioral and attitudinalaspects (Dick & Basu, 1994; Oliver, 1997). In keeping with this view, Zhao (2001)posits that repeat visits (frequency of visits) is just one side of the story and arenot enough to describe loyalty in an online environment. Crockett (2000) arguesthat the time consumers spend at a Web site, in addition to the frequency withwhich they return, should be included into the operationalization of Web site loy-alty. Therefore, loyalty towards a Web site encompasses users’ return to thesame site (repeat visits) and also their stay (stickiness) at the site. Recently,researchers (e.g., Floh & Treiblmaier, 2006) have argued that the attitudinalaspect (i.e., stickiness at a Web site) needs to be incorporated in the under-standing because it has implications not only for a higher repurchase intent, butalso for resistance to counter-persuasion, resistance to adverse expert opinion,

Trusting BeliefsAbility

BenevolenceIntegrity

Web SiteLoyalty

PerceivedFlow

Motives(Goal-Directed/Experiential)

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

169

willingness to pay a price premium, and willingness to recommend the serviceprovider to others (Oliver, 1993; Palmer, 2002).

Based on Oliver’s (1999) and Zhao’s (2001) definitions, this research hasadopted a two-dimensional conceptualization of Web site loyalty, consisting ofboth revisit and stickiness. Accordingly, in this study, Web site loyalty is definedas a deeply held willingness and commitment to revisit the Web site consis-tently and desire to stay more at the Web site at each visit, thereby causingsticky and repetitive visits.

Trust and Trusting Beliefs

Trust can be defined as a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whomone has confidence (Moorman, Zaltman, & Deshpande, 1992). Although someresearchers have treated trust as a unitary concept (e.g., Rotter, 1971), mostnow agree that trust is a multidimensional construct with two interrelated com-ponents: trusting beliefs (perceptions of trustworthiness of the vendor) andtrusting behavior (willingness to depend) (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995;McKnight, Choudhury, & Kacmar, 2002; Rousseau et al., 1998; Yousafzai,Pallister, & Foxall, 2005). In an online setting, while trusting beliefs represent a sen-timent or expectation about a Web site’s trustworthiness (Moorman, Zaltman, &Deshpande, 1992), trust-related behaviors refer to actions that demonstratedependence on a Web site (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995).

Trusting beliefs are the trustor’s perceptions that the trustee possesses char-acteristics that would benefit the trustor (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995;McKnight & Chervany, 2001). In other words, they collectively reflect the per-ceptions of the trustworthiness of the object of trust (Smith & Barclay, 1997).Although various trusting beliefs have been studied in the literature and differentterms have been used to refer to those different trusting beliefs, they have beengrouped into three beliefs: ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer, Davis, &Schoorman, 1995; McKnight, Choudhury, & Kacmar, 2002; Schlosser, White, &Lloyd, 2006; Sirdeshmukh, Singh, & Sabol, 2002).

Ability beliefs reflect the consumers’ confidence that a firm has the skills andcompetencies necessary to perform the job (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995).In the literature it has been shown that marketing investments can serve as asignal firms use to reflect their abilities (e.g., Kirmani & Wright, 1989). Accord-ingly, observable Web site design–related investments (e.g., many menu options,superior transaction procedures) lead consumers to make inferences aboutthe functions at a Web site, such as ease of navigation and order fulfillment,and are therefore instrumental in generating beliefs about a Web site’s abilityto perform its stated functions (Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006). Benevolencebeliefs reflect the confidence that a firm has a positive orientation toward its con-sumers beyond an egocentric profit motive, will consider their well-being ratherthan its own benefits, and will act in the consumers’ interests (Mayer, Davis, &Schoorman, 1995). Privacy or security statements at a Web site indicating howthe Web site uses consumer-related information (Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006),the display of trustworthy third-party seals (Yang et al., 2006), and descriptionof corporate social responsibility activities at a Web site are likely to yield thebenevolence-related beliefs. Finally, integrity beliefs reflect the confidence that aWeb site adheres to a set of moral principles or professional standards thatguide its interactions with its consumers. They include the expectation that the

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

170

Web site will act in accordance with socially accepted standards of honesty ora set of principles that consumers expect, such as not telling a lie or keeping apromise (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995). The Web site characteristics thatpertain to the validity of the information or procedures presented at the Web site(e.g., using standard transaction practices, external information validating theinformation presented at the Web site) signal the integrity-related beliefs at aWeb site. Further, when marketers include previous consumer/visitor evaluationsof the Web site’s past practices, it is aimed at generating integrity beliefs aboutthe Web site (Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006).

These three trusting beliefs are related yet distinct, as each belief capturessome unique elements of trustworthiness. For example, in an online environment,a consumer may believe that a Web site cares about its consumers and intendsto deliver a high quality of service (i.e., the Web site is benevolent), but they mayalso believe that the firm lacks the skills and ability to do so (Mayer, Davis, &Schoorman, 1995; Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006). Therefore, it is possible fora Web site to be perceived high on some of those beliefs and low on some oth-ers. Furthermore, some previous studies (e.g., McKnight, Choudhury, & Kacmar, 2002; Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006) have reported differences in termsof the effect of individual trusting beliefs on different behaviors. Following the suggestion to treat each trusting belief separately (e.g., Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006), the authors examine the individual effects of ability, benevolence,and integrity beliefs on Web site loyalty.

Drawing on past research on trusting beliefs (e.g., McKnight, Choudhury, &Kacmar, 2002), consumer motives (e.g., Hoffman & Novak, 1996), and flow (e.g.,Novak, Hoffman, & Duhacheck, 2003), a conceptual model is developed for under-standing (1) how consumer motives (i.e., goal-directed and experiential) deter-mine the relationship between the three trusting beliefs and loyalty, and (2) whetherthe level of navigation experience (i.e., flow) in each of the motive states strength-ens, weakens, or has no impact on the trusting belief–loyalty relationship.

Role of Consumer Motives

Goal-directed motives such as searching for specific information and experien-tial motives such as browsing for recreational purposes have received consid-erable attention in online environments. While goal-directed motives arestructured and aimed at achieving a specific purpose, experiential motives are relatively unstructured and recreational in nature (Hartman et al., 2006;Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003; Schlosser, 2003).

Researchers have asserted that each of the motives, experiential and goaldirected, embodies a unique set of information processing needs (Agarwal &Venkatesh, 2002) that persuades consumers to adopt separate mechanisms thatguide their evaluations and perceptions of the Web site (e.g., Schlosser, 2003).Kim and Benbasat (2003) theorize that consumer-related factors (i.e., customerresource lifecycle) influence perceptions of trust at a Web site, suggesting thatconsumers with distinct motives will rely on distinct trusting beliefs at a Website to determine their willingness to return or stay at the Web site.

Consumers with an experiential motive are not guided by goals or outcomesand adopt a nonlinear, intuitive, and spontaneous route. Specifically, instead offocusing on the information content or information structure at the Web site, theyfocus on other interesting aspects of the environment, such as rhythm and

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

171

metaphors used (Rosenblatt, 1978; Schlosser, 2003). Since consumers with anexperiential motive seek a personalized, engaging interaction with the Web site,they tend to focus on credibility aspects of the Web site (e.g., privacy statements,external validation), which allow them to feel confident and comfortable inseeking to fulfill their experiential goals. Therefore, consumers with an expe-riential motive will rely on the trusting beliefs that arise from the credibilityaspects of a Web site (i.e., benevolence and integrity) to determine their loyaltytoward the Web site. Moreover, since consumers with an experiential motive arenot focused on performance-related issues, the ability-related trusting belief thatcaptures whether the content or structure of the Web site enables them to ful-fill some search objective at a Web site should have relatively little or no effecton their Web site loyalty (Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006). Thus, the firsthypothesis is

H1: For consumers with an experiential motive, Web site loyalty is driven by their beliefs about the Web site’s benevolence and integrity rather thantheir beliefs about the Web site’s ability.

In contrast, consumers with a goal-directed motive use the Internet for itsinformative value and purchase utility, such as searching for information to com-plete a task or to reduce purchase uncertainty (Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Novak,Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003; Schlosser, 2003). Consumers with a goal-directedmotive are outcome-focused, allocating effort to activities that are means to achiev-ing an end (Deci & Ryan, 1985). They have a clearly definable goal hierarchy(Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003), adopting the mostefficient linear routes to achieve their end goal. Therefore, they focus on limitedelements that help them gather information efficiently to pursue their end goal(Janiszewski, 1998). Due to their orientation toward reaching the end goal effi-ciently, they are likely to focus on performance-oriented Web site elements per-taining to organization of content and navigational efficiency at the Web site(Dutta-Bergman,2005) and on interactive features such as active server pages (ASPs)that enable consumers to customize information at a Web page (Fiore, Jin, & Kim,2005). Accordingly, for consumers with a goal-directed motive, the ability-relatedtrusting belief generated from these cues will be a significant determinant of loy-alty (Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006). Moreover, for these consumers, the integrity-related belief also has implications for loyalty. For example, the beliefs about thestability of procedures at the Web site are likely to determine whether the con-sumers can maintain their performance at the Web site in future visits. In contrast, trusting beliefs, which are not performance-related (i.e., benevolencebelief), should have relatively little or no effect on their Web site loyalty (Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006). Therefore, the second hypothesis is:

H2: For consumers with a goal-directed motive, Web site loyalty is driven bytheir beliefs about the Web site’s ability and integrity rather than theirbeliefs about the Web site’s benevolence.

Although consumers in each of the different motives have a different trustingbelief–loyalty relationship, the nature of their navigation experience (e.g., levelof flow) would determine the strength of the trusting belief–loyalty relationship.

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

172

Role of Flow in the Belief–Loyalty Relationship

The construct of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) has been proposed by Hoffman andNovak (1996) as essential to understanding navigation experiences in onlineenvironments. In broad terms, the state of flow is defined as one where the con-sumer experiences an “optimal mental state” and is achieved if the consumerhas an immersive and compelling experience at a Web site (Csikzentmihalyi,1975, 1990; Hoffman & Novak, 1996; Huang, 2006; Mathwick & Rigdon, 2004).Researchers have shown that both consumers who are engaged in a focused,goal-directed search task and those engaged in an experiential browsing taskcan experience a state of flow at a Web site because both motives enable them tobe completely immersed in their respective activities (Mathwick & Rigdon, 2004;Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003). For example, a corporate buyer closing adeal at a Web site experiences a goal-directed state of flow while a surfer explor-ing a Web site would experience an experiential state of flow (Hoffman & Novak,1996). Flow generated during specific tasks at a Web site creates “memorableexperiences that are believed to strengthen relationships” (Deighton & Grayson,1995). In an online context, researchers have theorized that such positive flowexperiences can attract consumers, mitigate price sensitivity, and positively influ-ence subsequent attitudes and behaviors (Novak, Hoffman, & Yung, 2000). Specif-ically, researchers have shown that a compelling flow experience is positivelyassociated with consumer attitudes toward the focal Web site and the focal firm(Mathwick & Rigdon, 2004) and with the intention to revisit and spend moretime at the Web site (Kabadayi & Gupta, 2005). Therefore, the level of flow expe-rienced is likely to influence the trusting belief–loyalty relationship.

While flow can be experienced in both motive states, due to the differences inthe nature of tasks in each of the two motive states, there are likely to be differ-ences in the types of flow generated in each of the two motive states. In turn, thisdifference in the nature of flow across the two motive states may influence the trust-ing belief–loyalty relationship differently. In other words, this research examineswhether the trusting belief–loyalty relationship gets strengthened, weakened, oris not affected across varying levels of flow in each of the two motive states.

Consumers with an experiential motive are focused on deriving enjoymentfrom their navigation experience at the Web site (Schlosser, 2003) and thereforea high level of flow completely fulfils the sensation-seeking requirement. Sincethey are more oriented toward the process rather than the outcome (Deci &Ryan, 1985), the nature of their navigation experience will have a stronger effecton decisions to revisit and stay at the Web site than their inferences or beliefsabout the Web site. While the benevolence and integrity dimensions are impor-tant in driving loyalty outcomes among consumers with an experiential motive,the relationship weakens when consumers experience a high level of flow ascompared to a low level of flow. Therefore, the third hypothesis is:

H3a: For consumers with an experiential motive, the effect of benevolence-related beliefs on Web site loyalty weakens as the level of flow experiencedby consumers increases.

H3b: For consumers with an experiential motive, the effect of integrity-relatedbeliefs on Web site loyalty weakens as the level of flow experienced byconsumers increases.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

173

In contrast, although consumers with a goal-directed motive can experiencea high level of flow at a Web site, it does not fulfill their end goal of searchingfor or acquiring some specific information. Since consumers with a goal-directedmotive are focused on the outcome of acquiring something specific, outcome-related factors such as the beliefs about the ability and integrity of the Web sitedrive their decisions to revisit and stay at the Web site. Therefore, the effects ofthe ability- and integrity-related beliefs on loyalty do not vary across levels of flowbecause the trusting beliefs about performance at a Web site (i.e., ability andintegrity) are the primary drivers of loyalty towards the Web site. The fourthhypothesis is:

H4a: For consumers with a goal-directed motive, the effect of ability-relatedbeliefs on loyalty does not change as the level of flow experienced by con-sumers increases.

H4b: For consumers with a goal-directed motive, the effect of integrity-relatedbeliefs on loyalty does not change as the level of flow experienced by con-sumers increases.

METHODOLOGY

Participants

One hundred forty-five undergraduate business students at a northeastern uni-versity participated in the study in exchange for course credit. The sample was47% female. All participants had bought a CD online before: 19% bought morethan five CDs each month, 31% bought two to five CDs each month, 37% boughtone CD each month, and 13% had bought a CD online but did not buy frequently.

Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of two existing Web sites that were selected to ensure vari-ance in the data. First, in a pretest, subjects were asked to list CD-selling Websites. As in similar studies (e.g., Jarvenpaa, Tractinsky, & Vitale, 2000), the twoWeb sites that appeared at the top of all lists were not chosen as stimuli to ensurethat the well-knownness of those Web sites would not confound the findings.Another important consideration for the choice of Web sites was whether theWeb site had an offline presence (i.e., brick and mortar store) or not. Since the offline presence may confound the findings,Web sites with only online presencewere chosen. The two Web sites chosen for this study were columbiahouse.comand cdbaby.com. Subjects responded to questions regarding their familiarity withthose Web sites (“I am very familiar with this Web site”) and their perceptionsof the two Web sites in terms of their size (“This Web site is a large one”). Therewas no significant difference between subjects’ perception of those Web sites interms of their size (Mcolumbiahouse � 3.53, Mcdbaby.com � 3.42; F � 2.68, n.s.).Also, eventhough Columbia House represents a relatively better known Web site thancdbaby.com, the difference between subjects’ familiarity with those two Web siteswas not significant (Mcolumbiahouse � 3.72, Mcdbaby.com � 3.54; F � 3.12, n.s.).

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

174

Procedure

Once the participants arrived at the computer lab, they were randomly assignedto one of the two Web sites, columbiahouse.com or cdbaby.com. Next, they weregiven one of the two task conditions, capturing the two distinct motives, goal-directed and experiential. The nature of the tasks was adopted from researchon goal-directed and experiential motives (Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003)and object interactivity (Schlosser, 2003). Subjects in the goal-directed condi-tion were instructed to go to the site with “the goal of efficiently finding some-thing specific within that site,” while those assigned to the experiential conditionwere instructed to “have fun, looking at whatever you consider interesting orentertaining” (Schlosser, 2003).1 Upon completion of their tasks, participantswere instructed to fill out the questionnaire provided.

Measures

Existing scales were adopted to measure the three trusting beliefs, flow, andloyalty. All of the variables were measured with 5-point Likert-type scalesanchored by “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” The specific scale items forthe variables are listed in Table 1 along with their sources, reliabilities, anditem loadings.

The primary dependent variable was loyalty toward the Web site. A 5-itemscale including the two facets of loyalty, revisit and stickiness, was used. Therevisit items included “it is likely that I will revisit this Web site in the nearfuture” and “it is likely that I will return to this Web site in the near future.” Thestickiness items included “it is likely that I will spend a long time at the Website,” “when I go to this Web site I would not mind spending a long time there,”and “when I visit this Web site, I do not want to switch to another Web site fora while” (Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003). The scores of the scales were averagedto derive an index score for loyalty towards the Web site (Cronbach’s � � 0.86).Higher scores indicate a more favorable loyalty toward the Web site. In addition,participants also responded to a set of perceived flow measures at the Web site(see Table 1). The items were developed based on some verbatims reported byNovak, Hoffman, and Duhachek (2003). They were “when I was browsing in thisWeb site, I felt totally captivated”; “when I was navigating this Web site, timeseemed to pass very quickly”; and “when I visited this Web site, nothing seemedto matter to me.”

Control Variables

Although this study focuses on the moderating role of consumer beliefs and flowon the relationship between three trusting beliefs and Web site loyalty, previ-ous research suggests that several other variables might affect consumers’ Web

1 The manipulation check for the two motive conditions (goal-directed and experiential) was pre-tested using a scale, based on the codes constructed by Novak, Hoffman, and Duhachek (2003)for the two tasks. The scale included items that specifically measured the goal-directed motiveversus the experiential motive. Participants in the goal-directed condition (M � 5.18) reporteda significantly higher score than those assigned to the experiential condition (M � 3.78; F �101.9, p � 0.01), suggesting that they were more focused and had an identifiable purpose.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

175

site attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Jarvenpaa, Tractinsky, & Vitale, 2000; Schlosser,White, & Lloyd, 2006). Therefore, the frequency of consumers’ Internet usage (howoften do you use the Internet per week, answers ranging from zero to more than10 hours per week), their experience with the Web in general (how experienceddo you consider yourself with the Internet, answers ranging from not experi-enced to very experienced), and their past experience with the specific Web sitein particular (how frequently have you visited this Web site before, answers rang-ing from not frequently to very frequently) were included as control variables.

Measure Validation

The measurement properties of the constructs were evaluated in confirmatoryfactor analyses using Lisrel 8.71. The model fit was evaluated by using a seriesof indices suggested by Gerbing and Anderson (1988) and Hu and Bentler (1999),including a goodness of fit index (GFI), a comparative fit index (CFI), and the rootmean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The model fitted the data satis-factorily [model: x2(124) � 176.85, p � 0.00; GFI � 0.93; CFI � 0.94; RMSEA �0.08]. All the factor loadings were highly significant (p � 0.001), which showedunidimensionality of the measures (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). The conver-gent validity of the measures was assessed by examining the path coefficients

Table 1. Scale Items, Sources, Reliabilities, and Item Loadings.

Scales Factor Loading

Trusting Beliefs (source: Jarvenpaa & Tractinsky, 1999; Mayer & Davis, 1999)

Integrity (� � 0.79)1. This Web site is honest with its visitors. 0.852. This Web site acts sincerely in dealing with its visitors. 0.76

Ability (� � 0.80)1. This Web site has the ability to handle business on the Internet. 0.802. This Web site has sufficient expertise and resources to do business 0.78

on the Internet.3. This Web site has adequate knowledge and skills to manage its 0.83

business on the Internet.

Benevolence (� � 0.83)1. This Web site keeps my best interests in mind. 0.852. This Web site considers my welfare besides making profit. 0.82

Flow (� � 0.76) (source: Novak, Hoffman, & Duhachek, 2003)1. When I was browsing in this Web site, I felt totally captivated. 0.862. When I was navigating this Web site, time seemed to pass 0.83

very quickly.3. When I visited this Web site, nothing seemed to matter to me. 0.72

Loyalty (� � 0.86) (source: Anderson & Srinivasan, 2003)1. I am willing to revisit this Web site in the near future. 0.812. I am willing to return to this Web site in the near future. 0.843. I enjoy spending long time in this Web site. 0.834. When I go to this Web site, I want to spend more time there. 0.845. When I visit this Web site, I do not want to switch to another 0.88

Web site for a while.

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

176

(loadings) for each latent factor to their manifest indicators. The analysis indi-cated that all items loaded significantly on their corresponding latent factors (seeTable 1). Then, discriminant validity was assessed by examining the shared vari-ance between all possible pairs of constructs in relation to the average varianceextracted for each individual construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1982; Bagozzi & Yi,1988).As expected, the former was much lower than the latter (see Table 2). A reli-ability test was performed for each construct to see if all the measures demon-strated satisfactory coefficient reliability. All Cronbach’s alphas of the constructswere above 0.70. Thus, the measures demonstrated adequate convergent valid-ity and reliability.

Analysis and Results

To test the first two hypotheses, two separate stepwise regression analyses wereconducted, one for consumers with an experiential motive (n � 74) and anotherfor consumers with a goal-directed motive (n � 71). This method allows theresearcher to examine the contribution of each independent variable to the regression model and thus to identify the best subset of independent vari-ables that predict the dependent variable. For consumers with an experientialmotive the first integrity variable, the variable with the highest correlation withthe dependent variable, was entered into the model (model 1). Then, in additionto integrity, benevolence was entered into the regression model (model 2). Finally,in addition to the first two variables, ability was entered (model 3). As shown inTable 3, the results indicate that the addition of benevolence to integrity (model 2)had a significant contribution to the model (�R2 � 0.132, p � 0.001). However,the addition of ability into the regression model (model 3) did not contributesignificantly to explaining Web site loyalty (�R2 � 0.011, n.s.). Furthermore,while both integrity (b � 0.41 in model 1, b � 0.37 in model 2, and b � 0.34 in model 3) and benevolence (b � 0.32 and b � 0.29 in model 2 and 3,respectively) had significant positive relationships with Web site loyalty, abil-ity had no such significant relationship (b � 0.11, n.s.). These findings con-firmed that ability belief is not significant in explaining Web site loyalty ofconsumers with an experiential motive. Thus, H1 was supported.

For consumers with a goal-directed motive, the same procedure was repeated(model 1). Then, in addition to integrity, ability was entered into the regression

Table 2. Correlations and Descriptive Statistics (n � 145).

1 2 3 4 5

1. Integrity 1.002. Ability 0.35* 1.003. Benevolence 0.39* 0.28* 1.004. Flow 0.11 0.08 0.09 1.005. Loyalty 0.42* 0.33* 0.29* 0.12 1.00Mean 3.21 3.14 3.26 3.06 3.18Standard deviation 0.46 0.58 0.54 0.64 0.68Average variance extracted 0.59 0.52 0.61 0.51 0.58Highest shared variance 0.11 0.09 0.07 0.13 0.09

* p � 0.05.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

177

model (model 2). Finally, in addition to the first two variables, benevolence wasincluded into the regression model (model 3). The findings, as shown in Table 4,indicate that when ability was entered into the regression model in addition to integrity (model 2), R2 of the model significantly increased (�R2 � 0.101, p �0.001). However, the addition of benevolence into the regression model (model 3)did not contribute significantly to explaining Web site loyalty (�R2 � 0.019,n.s.). Furthermore, both integrity (b� 0.39 in model 1, b� 0.33 in model 2, andb� 0.31 in model 3) and ability (b� 0.28 and b� 0.26 in model 2 and 3, respec-tively) had significant positive relationships with Web site loyalty, whereasbenevolence had no such significant relationship (b � 0.09, n.s.). These find-ings give support to H2, confirming that unlike ability and integrity, benevolencebelief is not significant in explaining Web site loyalty of goal-directed consumers.

In the second part of the analysis, separate hierarchical moderated regres-sion analyses were conducted for consumers with experiential and goal-directedmotives to test interaction hypotheses 3 and 4. Following the advice of Aiken andWest (1991), all the variables were mean centered to minimize the threat ofmulticollinearity between the interaction terms and their components in equa-tions where the authors included the interaction terms. Multicollinearity amongthe variables was tested by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) for eachof the regression coefficients. The VIF values (lowest � 1.32; highest � 3.75)were well below the cut-off of 10.

Table 5 shows the findings of the hierarchical moderated regression analy-sis for consumers with an experiential motive. In Step 1, only the three control

Table 3. Stepwise Regression Analysis for Consumers with Experiential Motive(Dependent Variable: Web Site Loyalty) (n � 74).

Model Variables R2 F for R2 �R2 F for �R2 Coefficientsa

1 Integrity 0.44 9.47* – – 0.41*2 Integrity 0.57 12.45* 0.132 19.28* 0.37*

Benevolence 0.32*3 Integrity 0.58 11.40* 0.011 1.70 0.34*

Benevolence 0.29*Ability 0.11

a Standardized coefficients.

* p � 0.001.

Table 4. Stepwise Regression Analysis for Consumers with Goal-Directed Motive(Dependent Variable: Web Site Loyalty) (n � 71).

Model Variables R2 F for R2 �R2 F for �R2 Coefficientsa

1 Integrity 0.48 11.74* — — 0.39*2 Integrity 0.58 10.52* 0.101* 16.19* 0.33*

Ability 0.28*3 Integrity 0.60 9.80* 0.019 3.36 0.31*

Ability 0.26*Benevolence 0.09

a Standardized coefficients.

* p � 0.001.

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

178

variables were entered. In Step 2, the main effects of ability, benevolence, andintegrity beliefs and flow were entered along with the control variables. Andfinally, in Step 3, the two-way interaction effects between three trusting beliefswith flow were entered along with the control variables and the main effects ofability, benevolence, and integrity beliefs and flow. Evidence of the two-wayinteractions, H3a and H3b, would exist if the interaction terms accounted for asignificant incremental variance in explaining Web site loyalty, either individ-ually, manifested by negative beta values, or collectively, revealed by the valuesof the incremental F-statistic.

As shown in Step 1 (Table 5), none of the control variables were significantlyrelated to Web site loyalty. Next, Step 2 provided a significant increase in varianceexplained over Step 1 (�R2 � 0.17, �F � 6.78, p � 0.001). While integrity beliefs(b� 0.34, t � 6.52, p � 0.001) and benevolence beliefs (b� 0.27, t � 4.39, p � 0.05)were positively and significantly related to Web site loyalty, ability (b� 0.12, t �1.79) and flow (b � 0.09, t � 1.49) had no such significant relationship.

The two-way interaction hypotheses (H3a and H3b) were tested by observing theincremental variance explained by Step 3 over Step 2.As shown in Table 5, the addi-tion of the two-way interactions between ability, integrity, and benevolencebeliefs and flow increased R2 by 19% in Step 3 over Step 2 (�F � 8.43,p � 0.001). More specifically, the interaction between integrity belief and flow(b � �0.38, t � �7.34, p � 0.001) and the interaction between benevolencebelief and flow (b � �0.32, t � �6.82, p � 0.05) were both negatively and sig-nificantly related to Web site loyalty. However, the interaction between abilitybelief and flow was negatively but insignificantly related to Web site loyalty.

Table 5. Hierarchical Moderated Regression Analysis for Consumers with Experiential Motive (Dependent Variable: Web Site Loyalty) (n � 74).

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Variables ba t-value ba t-value ba t-value

ControlsFreq. of usage 0.11 1.37 0.14 1.49 0.12 1.43Web exp. 0.07 0.97 0.11 1.12 0.08 1.02Web site exp. 0.09 1.25 0.12 1.35 0.11 1.29

Main EffectsIntegrity (1) 0.34 6.52* 0.36 6.79*Benevolence (2) 0.27 4.39** 0.29 4.85*Ability (3) 0.12 1.79 0.11 1.72Flow (4) 0.09 1.49 0.10 1.51

Interaction Effects1 � 4 �0.38 �7.34*2 � 4 �0.32 �6.82**3 � 4 �0.014 �1.48

R2 0.21 0.38 0.57F 16.8** 17.2* 23.4*�R2 0.17 0.19�F 6.78* 8.43*

a Standardized coefficients.

* p � 0.001; ** p � 0.05.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

179

To better interpret the findings on interaction effects and gain further sup-port for the direction of the hypothesized interaction relationships, a simpleslope analysis was conducted, as suggested by Aiken and West (1991). Low levelof flow was calculated by subtracting one standard deviation from mean, and highlevel of flow was found by adding one standard deviation to mean value. Table 6shows that the slopes of benevolence beliefs and integrity beliefs and their rela-tionships with Web site loyalty remained positive at different levels of flow.However, the slopes were significantly more positive at low levels of flow (0.39for integrity and 0.35 for benevolence) than at high levels (0.18 for integrityand 0.14 for benevolence). These results suggest that an increase in flow weak-ens the positive effects of integrity and benevolence on Web site loyalty. Thus,the results of slope analysis combined with hierarchical moderated regressionanalysis results provide support for H3a and H3b.

For consumers with goal-directed motives, the same hierarchical moderatedregression analysis as explained above was repeated. H4a and H4b would besupported if the addition of interaction terms did not increase the variance inexplaining Web site loyalty, either individually, manifested by insignificant betavalues, or collectively, revealed by the values of the insignificant �F-statistic. Asshown in Table 7 in Step 1, control variables had no significant relationship withWeb site loyalty. In Step 2, the variance explained significantly increased over thevariance explained in Step 1 (�R2 � 0.22, �F � 7.11, p � 0.001). In Step 2, bothintegrity beliefs (b � 0.32, t �7.43, p � 0.001) and ability beliefs (b � 0.28, t �5.57, p � 0.05) were found to be positively and significantly related to Web siteloyalty. However, neither benevolence beliefs (b� 0.08, t � 1.36) nor flow (b� 0.10,t � 1.32) had such significant relationships with Web site loyalty.

The two-way interaction hypotheses for consumers with goal-directed motives(H4a and H4b) were tested by observing the increase in variance explained byStep 3 over Step 2. As shown in Table 7, the addition of the two-way interactionsbetween ability, integrity, and benevolence beliefs and flow increased R2 only by2% in Step 3 over Step 2 (�F � 1.09, n.s.). This insignificant increase in R2 indi-cated that addition of interaction effects was not significant. This finding wasfurther supported by insignificant coefficients for the interaction between integritybelief and flow (b� �0.14, t � �2.03, n.s.) and interaction between ability beliefand flow (b � �0.12, t � �1.92, n.s.). Thus, H4a and H4b were supported.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The major thrust of this research lies in understanding the relationship betweenthe three distinct trusting beliefs (i.e., ability, integrity, and benevolence) and

Table 6. Slope Analysis for Various Levels of the Moderator Variable (Flow)for Consumers with Experiential Motive.

Slope for Various Levels of Flow

Low (M � SD) High (M � SD)

Integrity beliefs → Loyalty 0.39 0.18Benevolence beliefs → Loyalty 0.35 0.14

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

180

loyalty within the context of specific consumer motive orientations in an onlineenvironment. Additionally, this research explores whether the level of flow expe-rienced at each of the motive states influences the trusting belief–loyalty rela-tionship. The findings are consistent with the view that trusting beliefs do nothave an equally strong influence on online evaluations across motive orienta-tions (Schlosser, White, & Lloyd, 2006). The results show that the relative impor-tance of specific trusting beliefs in determining loyalty varies based on theconsumers’ motives for visiting the Web site. For example, among consumerswith an experiential motive, benevolence- and integrity-related beliefs were thekey drivers of loyalty, while ability-related beliefs were not. On the other hand,among consumers with a goal-directed motive, the ability- and integrity-relatedbeliefs were the key drivers of loyalty, while benevolence-related beliefs were notthat influential. Together, these findings underscore the importance of under-standing the consumers’ motives for visiting a Web site. These motives are closelytied to specific signals (e.g., Web site navigation, privacy statements) that trig-ger the relevant trusting beliefs, which determine consumers’ decisions to revisitand spend more time at the Web site.

Furthermore, the results indicate that the level of flow experienced at eachof the motive states may or may not influence the trusting belief–loyalty rela-tionship. For consumers with an experiential motive, as the level of flow increases,the positive effects of the integrity and benevolence beliefs on loyalty becomeweakened. However, for consumers with a goal-directed motive, changes in thelevel of flow do not influence the relationships between their integrity and abil-ity beliefs and loyalty.

Table 7. Hierarchical Moderated Regression Analysis for Consumers with Goal-Directed Motive (Dependent Variable: Web Site Loyalty) (n � 71).

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Variables ba t-value ba t-value ba t-value

ControlsFreq. of usage 0.09 1.25 0.12 1.21 0.11 1.31Web exp. 0.05 0.87 0.09 1.01 0.12 1.17Web site exp. 0.10 1.31 0.12 1.37 0.09 1.26

Main EffectsIntegrity (1) 0.32 7.43* 0.36 7.65*Benevolence (2) 0.08 1.36 0.11 1.77Ability (3) 0.28 5.57** 0.31 6.53**Flow (4) 0.10 1.32 0.12 1.44

Interaction Effects1 � 4 �0.14 �2.032 � 4 �0.09 �1.783 � 4 �0.12 �1.92R2 0.29 0.51 0.53F 14.2** 19.6* 23.4*�R2 0.22 0.02�F 7.11* 1.09

a Standardized coefficients.

* p � 0.001; ** p � 0.05.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

181

This research further refines and extends research on the trust–loyalty rela-tionship in an online environment. Even though most previous studies haveshown that trust is an indispensable part of the loyalty building process, thosestudies have treated trust as a unitary construct. By examining trust as a func-tion of the three distinct trusting beliefs, it enriches the understanding of trusteffects on loyalty. Accounting for this multidimensionality enables researchersto understand how and when certain trusting beliefs can be triggered to instillthe desired loyalty responses for consumers. Although these constructs havebeen explored independently in separate studies, this research studies themtogether within an integrated framework to better understand how trustingbeliefs and loyalty relationships vary in distinct online environments.

Prior flow research focused on flow as a source of experiential value, exceptfor research by Mathwick and Rigdon (2004), who linked flow to the attitudinaloutcomes in an online environment. This research contributes to the extant flowliterature by revealing that for consumers with an experiential motive, the com-pelling flow experience is capable of delivering value at a level that eventuallyinfluences loyalty outcomes toward a Web site. Further, although previousresearch asserted that the state of flow can be induced in each of the motivationalorientations (goal-directed and experiential), its impact on navigational out-comes was not explored. This study extends this research stream by examiningthe interplay of flow and trusting beliefs across distinct motives. Specifically, theinfluence of the firm’s benevolence- and integrity-related beliefs on loyalty weak-ens when a consumer experiences a high level of flow as compared to a low levelof flow because the consumer with an experiential motive is primarily focusedon the satisfying navigation experience characterizing a high level of flow. Onthe other hand, ability-related trusting beliefs do not diminish in importanceacross levels of flow for consumers with a goal-directed motive because they arefocused on achieving a performance-oriented goal.

The findings provide invaluable managerial insight regarding Web site design,especially for new start-up Web companies. As demonstrated by previous stud-ies, Web site design is a critical part of Internet marketing strategy in buildingtrust (e.g., Hoffman, Novak, & Peralta, 1999; Shankar, Urban, & Sultan, 2002).A new start-up company with a new name, little awareness, limited financialresources, and low sales figures can be in a disadvantageous position vis-à-visother competitors that have existed for several years and have made invest-ments to design their Web sites to develop trust among the consumers. The find-ings of this research suggest that new companies’ sites can still have a pool ofrevisiting consumers who will spend a longer time at the sites as long as mar-keters can determine the consumers’ purposes for visiting the Web site. They canprovide enhanced navigation experiences or appropriate Web site signals toengender the relevant trusting beliefs among their visitors. In other words, mar-keters can tailor their Web sites and the tactics they use to match those consumermotives and thus ensure positive outcomes such as loyalty. Also, the findings sug-gest that Web sites do not need to invest in different signals to create differenttrusting beliefs simultaneously. Since two out of three trusting beliefs deter-mine the loyalty for consumers in each of the two motives, once they identify theconsumer motive for visiting the Web site, marketers can focus their invest-ments on creating the specific trusting beliefs relevant for the particular motive.Finally, since increased level of flow weakens trusting belief–loyalty relationshipsfor consumers with an experiential motive, marketers may devise strategies to

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

182

maximize the level of flow experienced by these consumers at the Web site andthus compensate for consumers’ low level of trusting beliefs.

While this research demonstrates the relationships between trusting beliefs,consumer motives, and navigation experiences in determining loyalty, severallimitations and follow-up questions for future research arise. One such limita-tion is the generalizability of the findings of this study to other products or Websites. Future studies may test the same relationships using different product cat-egories and Web sites. Also, given that individuals’ willingness to trust can beinfluenced by their culture, some studies may want to use subjects from differ-ent cultures to test the cross-cultural validity of the findings. While the resultsof this study show that the comparative relevance of specific trusting beliefsand positive flow experiences do vary across motives, the underlying processremains unexplored in this study. It would be interesting to examine whetherany other processes or variables (e.g., enhanced perceived control) mediate theeffects of trusting beliefs on loyalty. Finally, this study’s independent treatmentof the two motives is another limitation. A number of consumption activitiesare a combination of these two motives (e.g., information search across severalWeb sites for purchase), as consumers may first engage in an experiential searchwhere they explore across several Web sites and then engage in a more goal-directedfocused search where they scan for relevant information (Groner,Walder, & Groner,1984). Given that both these motives can occur within a single visit, there is aneed to examine how the dynamic nature of motives would impact consumers’reliance on trusting beliefs and navigation experiences in determining loyalty.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, R., & Venkatesh, V. (2002). Assessing a firm’s web presence: A heuristic evalu-ation procedure for the measurement of usability. Information Systems Research, 13,168–186.

Aiken, K. D., & Boush, D. M. (2006). Trustmarks, objective-source ratings, and impliedinvestments in advertising: Investigating online trust and the context-specific natureof internet signals. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34, 308–323.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interac-tions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, W. (1982). Some methods for respecifying measurement mod-els to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research,19, 453–460.

Anderson, R. E., & Srinivasan, S. (2003). E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingencyframework. Psychology & Marketing, 20, 123–138.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journalof the Academy of Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.

Berry, L., & Parasuraman, A. (1991). Marketing services. New York: The Free Press.Chen, Y. H., & Barnes, S. (2007). Initial trust and online buyer behavior. Industrial Man-

agement & Data Systems, 107, 21–36.Crockett, R. (2000). Keep ’em coming back. Business Week, 3681, 112.Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-

Bass.Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York:

Harper and Row.Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human

behavior. New York: Plenum.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

183

Deighton, A., & Grayson, J. (1995). Marketing and seduction: Building exchange rela-tionships by managing social consensus. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 660–676.

Dick, A., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: An integrated conceptual framework. Jour-nal of Academy of Marketing Science, 22, 99–113.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, A. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 35–51.

Dutta-Bergman, M. J. (2005). The impact of completeness and web use motivation onthe credibility of e-health information. Journal of Communication, 54, 253–269.

Fiore, A. M., Jin, H., & Kim, J. (2005). For fun and profit: Hedonic value from image interactivity and responses toward an online store. Psychology & Marketing, 22,669–694.

Floh, A., & Treiblmaier, H. (2006). What keeps the e-banking customer loyal? A multigroupanalysis of the moderating role of consumer characteristics on e-loyalty in the finan-cial service industry. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7, 97–110.

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale developmentincorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research,25, 186–192.

Groner, R., Walder, F., & Groner, M. (1984). Looking at faces: Local and global aspects ofscanpaths. In A. G. Gale & F. Johnson (Eds.), Theoretical and applied aspects of eyemovement research (pp. 523–533). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Hartman, J. B., Shim, S., Barber, B., & O’Brien, M. (2006). Adolescents’ utilitarian andhedonic Web consumption behavior: Hierarchical influence of personal values andinnovativeness. Psychology & Marketing, 23, 813–839.

Hoffman, D. L., & Novak, T. P. (1996). Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated envi-ronments: Conceptual foundations. Journal of Marketing, 60, 50–68.

Hoffman, D. L., Novak, T. P., & Peralta, M. (1999). Building consumer trust online. Com-munications of the ACM, 42, 80–85.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structureanalysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Model-ing, 6, 1–55.

Huang, M. H. (2006). Flow, enduring, and situational involvement in the web environment:A tripartite second-order examination. Psychology & Marketing, 23, 383–411.

Janiszewski, C. (1998). The influence of display characteristics on visual exploratorysearching behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 290–312.

Jarvenpaa, S., & Tractinsky, N. (1999). Consumer trust in an internet store: A cross-cultural validation. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 5. RetrievedDecember 23, 2008, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol5/issue2/jarvenpaa.html.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., Tractinsky, N., & Vitale, M. (2000). Consumer trust in an Internet store.Information Technology and Management, 1, 45–71.

Kabadayi, S., & Gupta, R. (2005). Web site loyalty: An empirical investigation of itsantecedents. International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, 2, 321–345.

Kim, D., & Benbasat, I. (2003). Trust-related arguments in Internet stores: A frameworkfor evaluation. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 4, 49–63.

Kirmani, A., & Wright, P. (1989). Money talks: Perceived advertising expense and expectedproduct quality. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 344–353.

Mathwick, C., & Rigdon, E. (2004). Play, flow, and the online search experience. Journalof Consumer Research, 31, 324–332.

Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system on trustin management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 123–136.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organiza-tional trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

McKnight, D. H., & Chervany, N. L. (2001). What trust means in e-commerce customerrelationships: An interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International Journal of Elec-tronic Commerce, 6, 35–59.

GUPTA AND KABADAYIPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

184

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trustmeasures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research,13, 334–359.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providersand users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations.Journal of Marketing Research, 29, 314–328.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., & Duhachek, A. (2003). The influence of goal-directed andexperiential activities in online flow experiences. Journal of Consumer Psychology,13, 3–16.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., & Yung, Y. F. (2000). Measuring the flow construct in onlineenvironments: A structural modeling approach. Marketing Science, 19, 22–42.

Oliver, R. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of satisfaction response. Jour-nal of Consumer Research, 20, 418–430.

Oliver, R. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York:Irwin/McGraw Hill.

Oliver, R. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44.Palmer, J. W. (2002). Web site usability, design, and performance metrics. Information

Systems Research, 13, 151–167.Papadopoulou, P., Andreou, A., Kanellis, A., & Martakos, D. (2001). Trust and relation-

ship building in electronic commerce. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Appli-cations and Policy, 11, 322–332.

Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust andrisk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Com-merce, 7, 101–134.

Reichheld, F. F., & Schefter, P. (2000). E-loyalty: Your secret weapon on the web.Harvard Business Review, 78, 105–113.

Rodgers, W., Negash, S., & Suk, K. (2005). The moderating effect of on-line experience onthe antecedents and consequences of on-line satisfaction. Psychology & Marketing,22, 313–331.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of liter-ary work. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Rotter, J. B. (1971). Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. American Psy-chologist, 26, 443–452.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all:A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

Schlosser, A. E. (2003). Experiencing products in the virtual world: The role of goal andimagery in influencing attitudes versus purchase intentions. Journal of ConsumerResearch, 30, 184–198.

Schlosser, A. E., White, T. B., & Lloyd, S. M. (2006). Converting web site visitors into buy-ers: How web site investment increases consumer trusting beliefs and online pur-chase intentions. Journal of Marketing, 70, 133–148.

Shankar, V., Urban, G. L., & Sultan, F. (2002). Online trust: A stakeholder perspective,concepts, implications and future directions. Journal of Strategic Information Sys-tems, 11, 325–344.

Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Sabol, B. (2002). Consumer trust, value and loyalty in rela-tional exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66, 15–27.

Smith, J. B., & Barclay, D. W. (1997). The effects of organizational differences and truston the effectiveness of selling partner relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 3–21.

Tsai, H. T., Huang, H. C., Jaw, Y. T., & Chen, W. K. (2006). Why on-line customers remainwith a particular e-retailer:An integrative model and empirical evidence. Psychology &Marketing, 23, 447–464.

Wu, J. J., & Cheng, Y. S. (2005). Towards understanding members’ interactivity, trustand flow in online travel community. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 105,937–954.

TRUSTING BELIEFS AND WEB SITE LOYALTYPsychology & Marketing DOI: 10.1002/mar

185

Yang, S. C., Hung, W. C., Sung, K., & Farn, C. K. (2006). Investigating initial trust towarde-tailers from the elaboration likelihood model perspective. Psychology & Marketing,23, 429–445.

Yang, Z., & Peterson, R. T. (2004). Customer perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: Therole of switching costs. Psychology & Marketing, 21, 799–822.

Yoon, D., Choi, S. M., & Sohn, D. (2008). Building customer relationships in an electronicage: The role of interactivity of e-commerce Web sites. Psychology & Marketing, 25,602–618.

Yousafzai, S. Y., Pallister, J. G., & Foxall, G. R. (2005). Strategies for building and com-municating trust in electronic banking: A field experiment. Psychology & Marketing,22, 181–201.

Zhao, M. (2001). Building loyalty in cyberspace. Proceedings from 2001 American Mar-keting Association Summer Conference, 65–71.

Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to: Reetika Gupta, Department ofMarketing, College of Business and Economics, Lehigh University, 621 Taylor Street,Bethlehem, PA 18015 ([email protected]).