The relationship between labour cost per patient and the size of intensive care units: a multicentre...

-

Upload

guido-bertolini -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

2

Transcript of The relationship between labour cost per patient and the size of intensive care units: a multicentre...

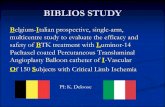

Received: 18 June 2003Accepted: 19 August 2003Published online: 5 November 2003© Springer-Verlag 2003

The authors appear on behalf of the GiViTIgroup [Gruppo Italiano per la Valutazionedegli Interventi in Terapia Intensiva (Italian Group for the Evaluation of Inter-ventions in Intensive Care Medicine)]. A complete list of study participants ap-pears in the Appendix

G. RossiI Servizio di Anestesia e Rianimazione,Spedali Riuniti,Livorno, Italy

E. ArrighiIstituto di Economia Sanitaria,Milan, Italy

B. SiminiServizio di Anestesia e Rianimazione,Ospedale Generale Provinciale,Lucca, Italy

was computed for each participatingunit, by applying to the average an-nual salaries the proportions of in-ICU activity working time for physi-cians and nurses. Multiple regressionanalysis was used to identify ICUcharacteristics that predict labourcosts per patient. Labour cost per patient was positively correlatedwith ICU mortality and patients av-erage length of stay (slopes =0.67,p =0.048 and 0.09, p <0.0001, re-spectively). Labour cost per patientdecreases almost linearly as thenumber of beds increases up to about eight, and it remains nearlyconstant above about twelve beds.The number of patients admitted per physician (not per nurse) increas-es with the number of beds (Spear-man correlation coefficient =0.567,p <0.0001). Conclusions: Our find-ings suggest that ICUs with less thanabout 12 beds are not cost-effective.

Keywords Intensive care unit · Intensive care · Costs and cost analysis · Health care costs · Health resources

Intensive Care Med (2003) 29:2307–2311DOI 10.1007/s00134-003-2019-1 B R I E F R E P O RT

Guido BertoliniCarlotta RossiLuca BrazziDanilo RadrizzaniGiancarlo RossiEnrico ArrighiBruno Simini

The relationship between labour cost per patient and the size of intensive careunits: a multicentre prospective study

Introduction

Although Intensive Care Units (ICUs), compared to oth-er hospital wards, consume lots of resources [1], theircosts are not accurately analysed [2]. Salaries certainlyaccount for the largest slice of total ICU costs, up to 55%[3], but ICU staff often also work outside the unit fornon-ICU patients (extra-ICU activities). Staff time actu-

ally devoted to ICU patients (in-ICU activity) varieswidely among differently organised units [4]. Hence sal-aries, which include the cost of extra-ICU activities, can-not be used to accurately compare labour costs in differ-ent ICUs [5].

Within the framework of a wider multiannual projecton ICU costs and consumption of resources started in1997, we determined the cost of the time actually spent

G. Bertolini (✉) · C. RossiGiViTI Coordinating Center,Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario Negri”, Centro di Ricerche Cliniche per le MalattieRare Aldo e Cele Daccò,24020 Ranica, (Bergamo), Italye-mail: [email protected].: +39-035-4535313Fax: +39-035-4535371

L. BrazziIstituto di Anestesia e Rianimazione,Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico IRCCS,Milan, Italy

D. RadrizzaniI Servizio di Anestesia e Rianimazione,Ospedale Civile di Legnano,Legnano, (Milan), Italy

Abstract Objective: We examinedthe relationship between major ICU characteristics and labour costper patient. Design: Four-week pro-spective data collection, in which the hours spent by each physicianand nurse on both in-ICU and extra-ICU activities were collected. Setting: Eighty Italian adult ICUs.Measurements and results: The costof the time actually spent by ICUstaff on ICU patients (labour cost)

by ICU staff on in-ICU activities and sought whether itis correlated with indicators of ICU size and activity [5].

Materials and methods

Of all 202 ICUs belonging to the Gruppo italiano per la Valutazi-one degli Interventi in Terapia Intensiva (GiViTI), 110 ICUs withan interest in costs were invited to take part.

Data collection

In order to estimate actual labour costs, two differentsurveys were done by means of previously validatedquestionnaires. First, we recorded the number of physi-cians’ and nurses’ working days allocated to each ICUduring the preceding year. We considered all physiciansand nurses paid for by the hospital administration, re-gardless of their position or seniority. Aides and helperswere not considered under nursing staff.

Indicators of ICU size and activity were also collect-ed. These indicators included: ICU typology (general,surgical, neurosurgical, cardiosurgical), ICU occupancyrate (number of patient-days provided during the year di-vided by the number of beds multiplied by 365), ICUmortality, the number of beds, the number of patients ad-mitted per year, and the number of patient-days, thenumber of physicians per bed, and of nurses per bed. Foreach ICU we considered the nominal number of beds,disregarding any planned or unplanned closure of bedsduring the year.

Second, in a 4-week prospective data collection cam-paign, we measured the actual working time, in hours,spent by each physician and nurse on both in-ICU andextra-ICU activities. In order to compute the annual ICUlabour cost, the average proportions of in-ICU activityworking time for physicians and nurses were applied tothe average annual salaries (taking into account staffworking part-time) for these categories of personnel em-ployed in each ICU. In order to derive labour cost per

patient, total labour cost was divided by the number ofadmissions for each ICU.

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression analysis using a step-by-step back-ward approach was used to identify independent predic-tors of labour costs per patient. All the available ICUcharacteristics were entered in the model. Following cli-nicians’ expectations, we sought a second-order polyno-mial fit between the number of ICU beds and labour costper patient. In the backward approach, different modelswere compared by means of the likelihood ratio test, us-ing p ≤0.05 as the level of significance.

Collinearity, i.e., the presence of a linear relationshipbetween independent variables, was assessed by meansof the Variance Inflation Factors and the Condition Num-ber [6]. A Variance Inflation Factor greater than 10 or aCondition Number greater than 30 were considered sug-gestive of moderate to severe collinearity, a problem thatcould affect the accuracy of regression calculations.

Normality and homoscedasticity of the dependentvariable distribution were assessed by means of theShapiro-Wilk test and the Spearman correlation coeffi-cient between predicted values and absolute values of re-siduals, foreseeing to use a data transformation to ac-complish the two goals. Data were analyzed with theSAS System 8.02.

Results

Eighty ICUs out of 110 (73%) took part in the project,and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Meanyearly personnel cost was 163,400 (SD=53.400)Euro/bed or 3,800 (SD=1.500) Euro/patient or 540(SD=194) Euro/patient-day. Labour cost was 128,300(SD=38.600) Euro/bed or 3,000 (SD=1.200) Euro/patientor 421 (SD=124) Euro/patient-day. The percentage of la-bour cost to total personnel cost ranged from 55% to

2308

Table 1 Characteristics of par-ticipating ICUs. (ICU IntensiveCare Unit, SD standard devia-tion, IQR interquartile range,pts. patients)

Type of ICU n (%)

General 68 (85.0%)Surgical 9 (11.3%)Pediatric 3 (3.8%)University affiliated n (%) 24 (30.0%)Number of beds mean (SD) − median (IQR) 7.9 (3.1) − 7 (6–9)Number of physicians/bed mean (SD) − median (IQR) 1.0 (0.5) − 0.9 (0.7–1.1)Number of nurses/bed mean (SD) − median (IQR) 2.5 (0.6) − 2.4 (2.0–2.8)Average length of stay mean (SD) − median (IQR) 7.5 (2.9) − 7.0 (5.8–8.6)Number of pts. admitted/year mean (SD) − median (IQR) 369.7 (211.0) − 318.5 (253.5–426)Average mortality mean (SD) − median (IQR) 20.3 (8.4) − 20.7 (14.0–27.1)Occupancy rate mean (SD) − median (IQR) 84.6 (14.9) − 84.8 (74.5–94.7)Number of hospital beds mean (SD) − median (IQR) 696 (381) − 583 (430–920)

100% in different ICUs. Physicians and nurses (exclud-ing heads) accounted for 40% and 49% of labour costs,respectively.

Both normality and homoscedasticity assumptions forlabour cost were violated (Shapiro-Wilk test =0.92,p <0.001; Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.285,p =0.012). Since the distribution was positively skewed

and variance increased markedly with increasing values,we adopted the log transformation, that successfullyhelped in normalising the distribution and stabilising thevariance (Shapiro-Wilk test =.99, p =0.57; Spearmancorrelation coefficient =0.15, p =0.20).

Three variables turned out to be significantly corre-lated with higher labour costs: number of ICU beds, av-erage ICU mortality, and average length of stay. Thenumber of beds squared gave a better fit of the datathan the number of ICU beds itself. VIF and CN ruled

2309

Fig. 1 Relationship between labour cost per patient and number of ICU beds (best multivariate polynomial fit)

Fig. 2 Relationship between the number of patients admitted perphysician/nurse — mean (SD) — and ICU size

out collinearity. The correlation coefficient was 0.63,p <0.0001.

Labour cost per patient was positively correlated withICU mortality and average length of stay, (slopes =0.67,p =0.048 and 0.09, p <0.0001 respectively). Labour costper patient decreases almost linearly as beds increase upto about eight, it remains roughly constant above 12 beds(Fig. 1).

Because of this result, we investigated the relation-ship between the number of patients admitted per profes-sional category and the number of ICU beds. The num-ber of patients admitted per physician increases with thenumber of beds (Spearman correlation coefficient =0.57,p <0.0001). The number of patients admitted per nurseremains constant regardless of the number of beds(Spearman correlation coefficient =0.12, p =0.31, seeFig. 2).

Discussion

Total ICU costs have been studied for years. Yet, al-though they account for about 55% of total costs [3],personnel costs have hardly been addressed. We have re-cently shown that the cost of labour actually devoted toICU patients by ICU staff is a reliable parameter to com-pare ICUs [5].

This study identified three determinants of ICU la-bour cost: length of ICU stay, average ICU mortality,and number of beds.

It is not surprising that the longer patients stay on theICU the higher the costs per patients are. Less intuitive iswhy average mortality and labour costs are correlated.However, since mortality can be seen as a proxy of theseverity of the ICU case-mix, the question boils down towhy labour cost per patient is higher in ICUs admittingmore critically ill patients. This has two possible expla-nations. On one hand, ICUs which treat more criticallyill patients tend to have more staff and/or this staff tendsto work only on the ICU. On the other hand, under-staffed ICUs probably transfer more severely ill patientsto other ICUs, thereby limiting admissions to cases witha lower mortality.

The third parameter we identified as a determinant ofICU labour cost, the number of beds, is an unprecedent-ed finding. We found that below about eight beds, as thenumber of beds decreases, labour cost per patient in-creases almost linearly and that above 12 beds it remainsnearly constant. Why does this relationship exist for phy-sicians and not for nurses? The nurse to patient ratio ishigher than the physician to patient ratio and, unlike thelatter, is constant in time (e.g., morning vs night) for agiven ICU. For this reason, the physician-to-bed ratio ismore easily tuned as the number of beds increases,reaching a plateau at which it is most cost-effective. Forexample, if the number of beds in an ICU changes from

four to eight, the number of nurses working in the ICUwill be accordingly increase by the same number ofnurses day and night. On the other hand, the number ofphysicians will undergo different increases at differenttimes of the day and night (e.g., two physicians insteadof one during the day, but still only one physician duringthe night). This yields a higher number of patients seenby each physician but no increase in the number of pa-tients per nurse.

In Europe, 62% of ICUs have less than ten beds, and36% less than seven beds [4]. The same figures for the202 Italian ICUs adhering to the GiViTI group are 83%and 49%, respectively. Are therefore most EuropeanICUs too small to be cost-effective? It is not easy to an-swer this question with the available data. ICU labourcosts are but one piece of a complex picture. From theperspective of those paying for health care, a small post-operative unit in a hospital with otherwise favourablecosts may be more cost-efficient than a larger unit in amore expensive hospital.

If we link our findings with those of a study on 79European ICUs, which showed that mortality is lowest inICUs with at least nine beds [4], we might conclude thatICUs with less than about ten beds are both too risky forpatients and too costly for those who run the ICUs.

Acknowledgements We are indebted to Marta Cattaneo for herinvaluable help. The study was partially supported by a grant fromRicerca Finalizzata, Ministero della Sanità, Contratto N° ICS-030.2RF95/199 “La valutazione delle prestazioni e dei costi delleTerapie Intensive nell’ambito del nuovo sistema di finanziamentoospedaliero” and by an unconditioned grant from AstraZeneca Ita-lia S.p.A., Milano, Italy.

Appendix

List of participating clinicians (with their hospitals in brackets):Guagliardi Clementina (Acquaviva delle Fonti-BA); PrigioneBonifacio (Alessandria); Gallini Carla (Alessandria); PennacchioniSilvio (Ancona); Vernero Sandra (Aosta); Nannoni Sonia (Arezzo); Gavioso Marina (Asti); Cinnella Gilda (Bari); PegoraroMaurizio (Bassano del Grappa-VI); Pezza Brunello (Benevento);Ricci Alessandro (Bologna); Neri Massimo (Bologna); Giovannitti Alfonso (Bologna); Sangiorgi Gabriela (Bologna);Baroncini Simonetta (Bologna); Zappa Sergio (Brescia); CabanoGianni (Busto Arsizio-VA); Pastorini Simonetta (Camposam-piero-PD); Gabriele Franco (Castellana Grotte-BA); QuattrocchiPasqualino (Catania); Visconti Maria Grazia (Cernusco S/N-MI);Mancinelli Annetta (Chieti); Camerini Sandro (Cremona); AlbertiArnaldo (Dolo-VE); Giannoni Stefano (Empoli); Maitan Stefano(Faenza-RA); Mantovani Giorgio (Ferrara); Bartoli Teresa (Firenze); Mangani Valerio (Firenze); Rossi Gianni (Imola-BO);Di Lullo Giuliana (Isernia); Cossu Giovanni (La Spezia); CarinciPier Paolo (Lanciano-CH); Caione Raffaele (Lecce); Ciceri Rita(Lecco); Tavola Mario (Lecco); Cirillo Francesco Maria (Legnago-VR); Cortellazzi Paolo (Legnano-MI); Rossi Giancarlo(Livorno); Paternesi Nazareno (Macerata); Guadagnucci Alberto(Massa); Sicignano Alberto (Milano); Rotelli Stefano (Milano);Boselli Luigi (Milano); Ravizza Adriano (Milano); Pezzi Angelo(Milano); Giudici Daniela (Milano); Beretta Luigi (Milano); Azzimonti Gaetano (Milano); Salmoiraghi Luisa (Milano);

2310

Marcora Barbara (Monza-MI); Postiglione Maurizio (Napoli);Zuccoli Paolo (Parma); Spadini Elisabetta (Parma); Negri Giovanni (Pavia); Carnevale Livio (Pavia); Gorietti Adonella(Perugia); Breschi Cesare (Pesaro); Dagnino Alessandro (PietraLigure-SV); Lagomarsini Ginetta (Pisa); Malacarne Paolo (Pisa);Lavacchi Luca (Pistoia); Garelli Alberto (Ravenna); Bottari Walter (Reggio Emilia); Pessina Carla (Rho-MI); Barberis Bruno

(Rivoli-TO); Manni Corrado (Roma); Appierto Linda (Roma); Siviero Silvano (Rovigo); Hellmann Ferruccio (Savigliano-CN);Vecchietti Massimo (Savona); Rosi Roberto (Siena); NuciforaConcetto (Siracusa); Scherini Alberto (Sondrio); Vaj Monica (Torino); Nascimben Ennio (Treviso); Cominotti Silvano (Varese); Zamponi Edoardo (Vercelli); Digito Antonio (Vicenza);Muttini Stefano (Vimercate)

2311

References

1. Jacobs P, Noseworthy TW (1990) National estimates of intensive care uti-lization and costs: Canada and the Unit-ed States. Crit Care Med 18:1282–1286

2. Glydmark M (1995) A review of coststudies of intensive care units: problemswith the cost concepts. Crit Care Med23:964–972

3. Edbrooke DL, Hibbert CL, Ridley S,Long T, Dickie H (1999) The develop-ment of a method for comparative cost-ing of individual intensive care units.Anaesthesia 54:110–120

4. Miranda DR, Ryan DW, Schaufeli WB,Fidler V (Eds.) (1998) Organization andmanagement of intensive care: a pro-spective study in 12 European Coun-tries. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York

5. Brazzi L, Bertolini G, Arrighi E, RossiF, Facchini R, Luciani D (2002) Top-down costing: problems in determiningstaff costs in intensive care medicine.Intensive Care Med 28:1661–1663

6. Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Muller KE(1988) Applied regression analysis andother multivariable methods.Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove, Calif., USA