The regulatory tax and house price appreciation in Florida

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

ron-cheung -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

1

Transcript of The regulatory tax and house price appreciation in Florida

Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Housing Economics

journal homepage: www.elsevier .com/locate / jhec

The regulatory tax and house price appreciation in Florida

Ron Cheung *, Keith Ihlanfeldt, Thomas MayockDepartment of Economics, 113 Collegiate Loop Room 288, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-2180, USA

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:Received 18 January 2008Available online 12 February 2009

JEL classification:R52R31H7

Keywords:Regulatory taxCost of regulationHouse pricesLand use regulation

1051-1377/$ - see front matter � 2009 Elsevier Incdoi:10.1016/j.jhe.2009.02.002

* Corresponding author. Fax: +1 (850) 644 4535.E-mail address: [email protected] (R. Cheung).

1 Both the nationwide as well as MSA-specific OFHEcan be found at http://www.ofheo.gov.

a b s t r a c t

Much attention was given to the soaring price of housing that took place in different partsof the country in the 1990s and the first half of the current decade. Traditional explanationsfor the increase include rising land values and costs of construction, but a strand of litera-ture, popularized by Glaeser et al. [Glaeser, Edward L., Gyourko, Joseph, Saks, Raven, 2005a.Why have housing prices gone up? National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper#11129; Glaeser, Edward L., Gyourko, Joseph, Saks, Raven, 2005b. Why is manhattan soexpensive? Regulation and the rise in housing prices. The Journal of Law and Economics48(2)], has looked at the role of land use regulations and posits that complying with themimposes a regulatory tax on housing consumers. In this paper, we apply and extend Glaeserand Gyourko’s methodology in order to estimate the regulatory tax on an individual houselevel in a set of Florida metropolitan areas. Our novel data address some of the quality mea-surement concerns raised about the Glaeser and Gyourko methodology and allow us tolook at the evolution of the regulatory tax over a 10-year period. We find that the tax isan important component of sales price and that as a percentage of sales price has increasedin a majority of Florida’s MSAs. In addition, we decompose the overall house price increaseinto land, materials and regulatory components and find that increasing stringency in theregulatory environment within Florida represents a substantial portion of the run-up inhouse prices in most metropolitan areas.

� 2009 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Before the recent downturn in the housing market,much media attention had been paid to the fact that theprice of housing soared over the 1990s and the first halfof the current decade. According to the repeat sales indexpublished by the Office of Federal Housing EnterpriseOversight (OFHEO), nationally the price of a constant-qual-ity home increased 131% between the first quarter of 1989and fourth quarter of 2005.1 Various explanations are of-fered for this phenomenon: demand-side explanations suchas demographic trends, wider financing options, and specu-lative buying as well as supply-side explanations such as ris-

. All rights reserved.

O repeat sales indices

ing costs of construction and increasing land scarcity.Whatever the reasons, rapidly rising house prices have sig-nificant welfare costs, particularly among households look-ing for low or moderately priced homes. Escalating pricesrepresent a significant barrier to first-time homeownershipand may lengthen commuting distances between workersand their jobs, as buyers are forced to purchase cheaperhomes in distant suburban or exurban communities.

While in some states – particularly those in the Sunbelt– demand and demographic trends undoubtedly encour-aged considerable in-migration and subsequent houseprice increases, the data suggest that fast populationgrowth does not automatically imply rapid price apprecia-tion. Table 1 shows some simple statistics. We calculateappreciation at the metropolitan statistical area (MSA)level between 1989 and 2005 in the OFHEO housing priceindex and group MSAs from all states into quartiles byprice appreciation. We compare four fast-growing states

Table 1Number of MSAs in quartile according to OFHEO housing price apprecia-tion, 1989 to 2005.

State 1st 2nd 3rd 4th

AK 0 0 2 0AL 5 5 1 0AR 2 2 2 0AZ 0 0 3 2CA 0 0 1 27CO 1 0 6 0CT 0 0 1 3DC 0 0 0 1DE 0 0 1 1FL 0 0 3 18GA 3 4 5 0HI 0 0 0 1IA 3 5 0 0ID 1 3 1 0IL 4 2 3 0IN 10 3 0 0KS 1 0 2 0KY 2 3 0 0LA 2 3 2 0MA 0 0 1 5MD 0 0 1 4ME 0 0 1 2MI 2 9 3 0MN 0 0 3 1MO 1 4 1 0MS 2 1 0 0MT 0 0 3 0NC 10 1 1 0ND 0 1 2 0NE 1 1 0 0NH 0 0 0 2NJ 0 0 1 6NM 0 1 3 0NV 0 0 0 3NY 1 2 3 6OH 5 5 0 0OK 1 2 0 0OR 0 2 3 1PA 0 6 7 1RI 0 0 0 1SC 1 2 2 0SD 0 1 1 0TN 4 5 0 0TX 17 8 1 0UT 4 0 1 0VA 0 1 4 3VT 0 0 1 0WA 2 1 6 1WI 2 5 5 0WV 3 2 1 0WY 0 0 2 0

2 A home is classified as affordable if the median income householdfacing current interest rates would qualify for the mortgage according tostandard underwriting criteria. NAHB assumes that a family can afford tospend 28% of its gross income on housing (http://www.nahb.org).

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 35

– specifically Texas, California, Florida and North Carolina,which place first, second, third and sixth, respectivelyamong the states in absolute population growth as of the2000 census. We see that while Florida and California havethe most MSAs in the top quartile in house price apprecia-tion, Texas and North Carolina have the most MSAs in thebottom quartile. On average across metropolitan areas,prices in Florida and California have appreciated 166%and 188%, respectively, between 1989 and 2005, whilethose in Texas and North Carolina have grown by only70% and 87%, respectively. These data suggest that despiterapid growth in demand, house prices in Texas and North

Carolina have not risen as quickly as prices in other rapidlygrowing states. Apparently in Texas and North Carolinawith the growth in demand there occurred a commensu-rate increase in supply. What then happened in Floridaand California to maintain such rapid housing pricegrowth?

One possible answer to this question can be found in astrand of recent literature that has looked at the impact oflocal land use regulations on housing prices. Regulationsare often enacted to affect the pattern of land use develop-ment, to make communities more attractive and to miti-gate negative environmental externalities caused bydevelopment. In practice, they encompass a myriad ofrules intended to affect the level and the type of develop-ment allowed. The most common form of local land useregulation is restrictive zoning, which stipulates differentdevelopment possibilities for different zones in the juris-diction. Beyond this, the regulatory arsenals of local gov-ernments commonly include impact and permitting feesand environmental impact studies to be undertaken bythe developer before permission to build is granted. InFlorida, and a growing number of other states, an impor-tant subset of regulations are those that implement thecomprehensive plans required by state growth manage-ment mandates. Finally, some regulations are designed toslow or halt development altogether; examples include an-nual building permit caps, urban growth boundaries andminimum lot size restrictions.

Notwithstanding the benefits that they may impart onresidents, land use regulations impede the supply of hous-ing. The costs of compliance and enforcement hold thesupply of new housing back in areas where the demandfor housing is expanding; this can result in higher houseprices, depending on whether regulatory costs are shiftedbackward to landowners or forward to housing consumers.Understanding the link between regulations and houseprices is crucial to the proper evaluation of regulationpolicy.

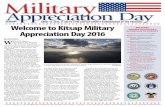

As an example of why land regulation matters to hous-ing policy, consider the fact that rising house prices are clo-sely linked to declines in home affordability. The mostwidely cited measure of affordability is the HousingOpportunity Index (HOI), published by the National Associ-ation of Home Builders, which measures the percentage ofhomes sold in a given geographic area that are affordableto a household with the median income.2 The evolutionof the HOI over the years 1995–2006 is plotted in Fig. 1for five metropolitan areas. There are striking differencesin the trends, suggesting that housing affordability problemsare metropolitan, as opposed to national, in scope. Housingin the West Palm Beach and Boston markets has becomemuch less affordable over the last decade, with the indexdropping sharply between 2002 and 2006. San Franciscohas also become less affordable since 1995. However, de-spite increasing population pressures, housing in the Dallasand Chicago MSAs seems no less affordable in 2006 than it

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005Year

NA

HB

Affo

rdab

ility

Inde

x

DallasChicagoWest Palm BeachSan FranciscoBoston

Fig. 1. HOI affordability index for five metropolitan areas.

36 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

was in 1995. We argue that part of the variation we observein affordability comes from the variation in land use regula-tions, both across metropolitan areas and over time. Indeed,the five metropolitan areas plotted in the figure are chosento represent different styles of land use regulation, on thebasis of a Brookings Institution study by Pendall et al.(2006). Dallas is classified in the group called ‘‘Wild WildTexas”, which is the most growth friendly region in the na-tion. Chicago is in the ‘‘Traditional” category, characterizedby voluntary planning and general laxity of land use regula-tion. Boston belongs to ‘‘Exclusion”, and West Palm Beachand San Francisco belong to ”Growth Control”; both classesare characterized by more stringent land use regulation andcomprehensive plan adoption. The figure shows a clear cor-relation between the effect of regulatory style and afford-ability across the metropolitan areas, but also suggeststhat style is related to the trend in affordability over time.As Pendall et al. point out, in many jurisdictions the localgovernments have ‘‘invented new growth control instru-ments [and]. . . modified their use of older standard toolsin attempts to influence development outcomes”.

There is a growing economic literature on the effect ofregulations on housing values. Quigley and Rosenthal(2005) overview papers on regulations and house pricesand find a lack of consensus, which they attribute to meth-odological and measurement differences across studies.They argue most studies rely on indices of restrictivenessbased upon the number and types of regulations in place,which in practice may not reflect the true degree of restric-tiveness in a jurisdiction due to differences in enforcement.In recognition of this, more recent work by Glaeser andGyourko (2003, hereafter GG) and Glaeser et al. (2005a,hereafter GGS) suggest an alternative methodology to mea-

sure the effect of regulations on prices. GG and GGS arguethat the price of a house, net of its costs of construction, com-prises both the value of the lot on which the home is situatedand the value of having satisfied all land use regulations.Their studies consist of estimating this last component,which they call the regulatory tax. They argue that theirtax is the result of suppressed housing supply and is largelyresponsible for the high price of housing that can be foundwithin select metropolitan areas throughout the US.

In this paper, we apply and extend the GG methodologyto the estimation of the regulatory tax in a set of Floridametropolitan areas, at the same time addressing some ofthe criticisms that Quigley and Rosenthal have made ofprevious studies. The contributions of our paper includethe use of individual house-level data over a 10-year period,a procedure for determining construction costs of housesof varying quality and a decomposition of the overall houseprice increase into land, materials and regulatory costcomponents. In contrast to GG and GGS, who measurethe regulatory tax for the average house within a metro-politan area, we, by estimating the tax at the house leveland then averaging up, are better able to control forhouse-specific construction costs and thereby obtain amore reliable estimate of the tax. We find that the tax isa significant component of house price and that increasesin this component account for a significant portion of therun-up in Florida house prices between 1995 and 2005,as the regulatory environment within the state over theseyears became increasingly more stringent. This study alsosheds light on the variation of regulatory stringency withina state. We find considerable variation in the scope andscale of regulation used within Florida, leading to differentimpacts on housing prices.

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 37

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we discussthe theoretical framework underlying the regulatory taxand the measurement of regulatory stringency. In Section3, we describe the methodology and the data used. In Sec-tion 4, we present our results. Section 5 concludes.

2. Background on measuring the land use regulationtax

Stringent regulation may raise prices for new homes be-cause it imposes time and money costs on developers. Italso may drive up prices of all homes (both new and exist-ing) by removing land from the possible supply of residen-tial land.3 The evidence on these possible relationships ishighly mixed. Some studies find a strong positive relation-ship between housing prices and regulation (e.g., Malpezzi,1996; Glaeser and Gyourko, 2003; Downs, 1991; Glaeseret al., 2005b), while others find little or no relationship(e.g., Phillips and Goodstein, 2000). In general, these studiesproceed by finding some measure of regulatory stringencythat varies across jurisdictions and then a reduced formmodel is estimated by regressing housing values or a hous-ing price index on stringency, along with a set of controlvariables representing other supply and demand shifters.

A fundamental obstacle is how to define regulatorystringency. The standard approach is to use survey datato formulate an index to rate jurisdictions along certain cri-teria.4 However, while straightforward, indices may notaccurately reflect the burden of stringent regulation.5 Oneproblem is that the researchers must decide which regula-tions to include in the index. A related problem is whatweight should be given to each regulation. Generally, with-out justification, each regulation is weighted equally. Finally,arguably the most serious obstacle is that count indices re-flect the regulations that are on the books, but the negotia-tion and compromise that commonly occurs betweendevelopers and municipal officials may result in a regulatoryenvironment that bears little relationship to the value of theindex. Indeed, Quigley and Rosenthal (2005) argue that thelack of definitive estimates of regulatory stringency in theempirical literature may be due to the fact that ‘‘...some-times, local regulation is symbolic, ineffectual, or onlyweakly enforced.”6

GG and GGS depart from the index approach and in-stead argue that the price of a house incorporates the costsof having satisfied all local land use regulations. In a com-petitive housing market devoid of land use regulations, thesales price of a newly constructed house equals the sum ofthe cost of constructing the house and the value of the loton which the home is located. The cost of construction in-

3 Restricting the supply of new housing can also reduce the rate at whichhigher quality homes filter down to lower income households. Forempirical evidence of this effect, see Mayer and Somerville (2000).

4 For instance, Brueckner (1998) counts the number of growth controls.5 See Somerville (2004) for a more thorough review of these issues.6 In addition, Quigley and Rosenthal cite four areas that the traditional

literature has failed to address. They are (i) ignoring the endogeneitybetween housing prices and regulations; (ii) not recognizing the interactionbetween policymaking and regulatory behavior; (iii) infrequent adminis-tering of regulatory surveys; and (iv) failing to use sophisticated priceindices that correct for biases in price reporting.

cludes the cost of labor and materials and also a normal re-turn for the developer. GG’s ”regulatory tax” hypothesisholds that regulations, because they add to the costs ofconstruction and restrict lot subdivision, introduce awedge that drives the selling price of the house higher thanthe sum of construction and land costs. GG use the Amer-ican Housing Survey to estimate the regulatory tax facedby the average house in various MSAs, and they find thatthe tax is negligible in some areas (mostly in the Midwest),but substantial in others, including markets in California,Florida and New York. Thus they claim that in some se-lected markets prices are high because of myriad landuse regulations.

In this paper, we apply the GG regulatory tax concept tohouse-level data from Florida. Our methodology has cer-tain advantages over GG and allows us to address someof the concerns about GG’s measurement of constructioncost and housing quality, raised by such authors as Somer-ville (2004). We use individual house level data from theFlorida property tax rolls and estimate the regulatory taxborne by the purchasers of individual homes.7 We use ac-tual sales price instead of an owner-estimated value, whichaddresses one of the limitations of prior studies raised byQuigley and Rosenthal (2005). Our estimations allow us tomove from speculation regarding the regulatory environ-ment and its role in explaining rising house prices to a solidestimate of its impact. Finally, the panel aspect of our dataallows us to calculate the regulatory tax for parcels for eachyear between 1995 and 2005, which enables us to decom-pose the total change in the price of housing into the por-tions attributable to construction costs, land value and theregulatory tax. This represents an improvement over previ-ous papers, which for the most part are static in nature.

Because our data allow us to estimate the regulatory taxon an individual house level, we can compute the mean va-lue of the tax for any level of aggregation in order to sum-marize our results. We argue that the correct level ofaggregation is the metropolitan area. While cities withinthe same metropolitan area have different land use regula-tions, inter-jurisdictional differences in regulatory restric-tiveness cannot cause differences in the regulatory taxacross cities if, as is commonly assumed, consumers aremobile within the metropolitan area. However, the averagelevel of restrictiveness within the metropolitan area mayaffect the metropolitan-wide housing price, since it is rea-sonable to assume that the demand for housing at themetropolitan level is less than perfectly elastic.

3. Methodology and data

Our general methodology for estimating the regulatorytax follows that of GG and GGS. In equilibrium, the cost of ahome in an unregulated market comprises two distinctcomponents: the value of land and the value of theimprovement on the land. If we denote the price of a home

7 It is important to keep in mind that the regulatory tax is not a tax perse, but rather a measure of the additional costs incurred as part ofcomplying with the land use regulations and regulation-driven supplyrestrictions. We use the term tax in order to be consistent with GG and GGS.

38 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

on a lot of size L as P(L), this equilibrium condition can bewritten as

PðLÞ ¼ rLþ K; ð1Þ

where r denotes the per unit price of land and K denotesthe cost of constructing the home.

In the presence of land use regulations, however, regu-latory compliance costs for developers and restrictions onthe subdivision of lots drive a wedge between the valueof a lot of size L in a competitive market (rL) and the resid-ual value of land obtained by netting out the cost of con-struction from the price of housing (P(L) � K). GG andGGS call this difference between the two implicit land val-ues the regulatory tax, denoted T below.8 The equilibriumcondition in the regulated model is now

PðLÞ ¼ rLþ K þ T; ð2Þ

and the price appreciation of a property can be decom-posed into three distinct parts: the change in the value ofland, Dr; the change in the costs of construction, DK; andthe change in the regulatory costs, DT. In unregulated mar-kets in which the market value of land is not increasingover time, this condition suggests that the increase in thevalue of a home should be roughly equal to the increasein the cost of home construction. To get a sense of whetherthis is reasonable, we plot in Fig. 2 the evolution of the OF-HEO price index along with the RS Means Company MSA-level construction cost index for the five MSAs mentionedin the previous section. The home price trends for Dallasand Chicago (the least regulated according to the Brook-ings study) follow the cost of construction trends closelyover the ten-year period.

The remaining three MSAs tell a different story. Theprice trends for West Palm Beach, Boston and San Fran-cisco follow the construction cost trend at the beginningof the sample period, after which the two trends divergedramatically. Appealing to Eq. (2), this divergence betweenhome values and construction costs may be attributable toeither increasing land value or costs of housingregulations.9

Determining the relative importance of the land andregulation components necessitates estimating the valueof land in various locales. As GG suggest, the value of anadditional unit of land can be estimated using standard he-donic regressions. Once this land value is estimated, the

8 A concern Somerville (2004) raises with GG is that they assume that T isconstant. In reality the regulatory taxes may vary with the size of the house.We discuss this issue further on in the paper.

9 Previous literature on house price appreciation hints at the role thatregulations play. Jud and Winkler (2002) look at house price appreciationacross 130 metropolitan areas and explain the yearly price appreciation bythe growth in variables such as population, income, wealth, interest ratesand construction costs. They take a fixed effects framework to control forMSA-specific cost factors. Their explanatory variables are all positive andsignificant (with the largest coefficient appearing on population growth),but notably, they find that the estimated MSA fixed effects are correlatedwith growth restriction indexes developed in Malpezzi (1996), Segal andSrinivasan (1985) and others. Malpezzi et al. (1998) also use cross-MSAdata and include a regulatory index as a determinant of house priceappreciation. A city that moves from the first to the third quartile ofregulatory stringency experiences a house price increase of between 32%and 46%.

portion of the home’s value attributable to regulatory costscan be backed out using the equilibrium condition. Byrepeating this estimation over time, we can decomposethe change in housing value into the portions attributableto changes in construction, land and regulatory costs.

3.1. Data and the Florida regulatory environment

We utilize a rich set of data containing geographic andsales information for single-family residences in the 20MSAs in Florida.10 The MSAs, each of which is composedof one or more counties, range widely in size as shown inthe summary statistics of Table 2. All parts of the state –Panhandle, inland and coastal – are represented in our anal-ysis. One MSA (Tallahassee) has only one incorporated city,while another (Miami-Hialeah) has 35. There is also varia-tion in housing price appreciation, as measured by changesin the median sales price between 1995 and 2005. Finally,there is evidence that suggests that there is variation in reg-ulatory stringency across MSAs. Developers and plannerstend to agree on which counties are stricter and which arelaxer. For instance, Leon County (Tallahassee MSA) has areputation for being stringent and anti-growth, while PolkCounty (Lakeland MSA) has a reputation for no-holds-barred, laissez-faire growth. While these perceptions areanecdotal, it is worthwhile to note that they are taken seri-ously by land developers, who have a clear interest in know-ing how much complying with regulations will add to theircosts. As additional evidence, Ihlanfeldt (2007) calculatesregulatory indices for Florida cities using the results froma 2002 survey of the chief planner of each city. The indicesrange from 1 (least stringent) to 7 (most stringent). We re-port the index for the largest city in each MSA in the last col-umn of Table 2. They provide additional evidence that thereis a range of regulatory stringency among the metropolitanareas that we examine.

In addition to cross-sectional variation in regulatorystringency, there are two reasons to believe that statewideregulation has over time become more stringent. Floridapassed its Growth Management Act in 1985, which man-dates comprehensive planning at the local level. Chapinet al. (2007) note that the land development regulationsrequired to implement the plans began to be adopted bylocal governments in the early 1990s and these regulationshave grown in number and complexity since then. More-over, regulations adopted at one point in time may not im-pede supply until later, when continuing populationgrowth causes the constraint imposed by the regulationto become binding. There are many examples of such reg-ulations in Florida, with the two most recognizable beingurban growth boundaries and transportation concurrency.As long as the boundary is beyond the urban fringe, it haslittle effect on the pace of development. Similarly, as longas traffic is low enough such that the required level of ser-vice is satisfied on a particular roadway, development con-tinues to occur.

10 In our analysis, MSAs are constructed using the 1990 definitions fromthe U.S. Census Bureau.

Price and Cost Index: Boston 1995-2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005Year

Inde

x Va

lue

RS Means IndexOFHEO Index

Price and Cost Index: Chicago 1995-2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005

Year

Inde

x Va

lue

RS Means IndexOFHEO Index

Price and Cost Index: Dallas 1995-2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005

Year

Inde

x Va

lue

RS Means IndexOFHEO Index

Price and Cost Index: San Francisco 1995-2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005Year

Inde

x Va

lue

RS Means IndexOFHEO Index

Price and Cost Index: West Palm Beach 1995-2005

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005Year

Inde

x Va

lue

RS Means IndexOFHEO Index

Fig. 2. Evolution of OFHEO repeat sales index and RS means construction cost index: 1985–2005.

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 39

House price information is obtained from the FloridaDepartment of Revenue’s (DOR) abbreviated county taxrolls from 1995 to 2005. For each parcel’s two most recentsales, these rolls contain information on the price of thehome, whether the transaction was arm’s-length and theyear and month of sale. In addition to the sales informa-tion, the rolls also contain typical structural characteristicssuch as the year the improvement was built, whether ornot the parcel was improved at the time of sale, and inte-

rior living space. Finally, the greatest strength of the DORdata is that for each parcel we have information on thereplacement cost of all of the improvements on the site.This aspect of the data is discussed more thoroughlybelow.

We first select the arm’s-length transactions of im-proved single-family properties for each year between1995 and 2005. Using GIS techniques, the square footageof each parcel is calculated, and the record for each parcel

Table 2Population, home values, regulatory environment and sample size for Florida MSAs.

MSA name No. of counties inMSA

Population Median home salesprice

Regulatory index* forlargest city

Sample size ofproperties

1995 2005 1995 2005

Bradenton 1 237,593 304,988 96,000 300,000 3 50,881Daytona Beach 1 413,419 486,369 72,900 195,000 3 67,790Fort Myers-Cape Coral 1 391,823 542,480 89,900 269,000 5 100,778Fort Pierce 2 290,527 376,328 67,000 243,000 1 59,712Fort Lauderdale- Hollywood-

Pompano Beach1 1,447,124 1,770,707 117,900 305,000 2 304,331

Fort Walton Beach 1 162,900 183,438 84,900 204,000 3 31,065Gainesville 2 228,234 259,887 71,500 173,200 5 30,197Jacksonville 4 1,000,149 1,225,080 85,900 197,000 6 49,213Lakeland-Winter Haven 1 447,182 538,783 69,000 167,000 3 55,198Melbourne-Titusville- Palm Bay 1 451,310 526,805 80,400 217,500 5 90,241Miami-Hialeah 1 2,086,286 2,356,378 114,500 299,000 5 169,032Naples 1 199,639 306,773 139,800 396,000 4 28,333Ocala 1 230,611 301,805 69,000 160,000 3 26,597Orlando 3 1,250,442 1,664,856 93,900 239,500 6 324,492Panama City 1 142,101 161,599 75,000 204,000 3 15,593Pensacola 2 380,205 445,042 71,900 162,900 2 67,594Sarasota 1 304,165 363,973 95,000 252,000 5 61,868Tallahassee 2 266,586 300,090 85,000 172,550 7 40,668Tampa-St Petersburg- Clearwater 4 2,226,036 2,643,092 81,000 197,900 4 348,125West Palm Beach- Boca Raton-

Delray Beach1 1,013,781 1,259,234 1,08,300 333,000 7 105,903

Florida 14,537,875 17,736,027 105,500 3.6**

* Index as in Ihlanfeldt (2007). The higher the index, the more stringent is the regulation.** State mean.

40 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

is assigned to a jurisdiction, census tract, and census blockgroup.11 We also calculate the distance from each parcel tothe center of the appropriate central business district andthe distance from the parcel to the coast for coastal MSAs.A final series of sample cuts are made to minimize the influ-ence of outliers.12 The last column of Table 2 reports thenumber of parcels in the sample of each MSA over the 10-year period.

3.2. Empirical methodology for estimating the regulatory tax

The first step in calculating the regulatory tax is to esti-mate the intensive value of land (r). It is important to notethat in this context, the intensive value of land, measuredper square foot, is simply the consumption value of an ex-tra square foot of lot. Reiterating GG’s argument, in a worldlacking regulatory constraints, the intensive value of a unitof land would be the price at which the homeowner wouldbe indifferent between (1) consuming the land and (2) sub-dividing and selling it. The fact that there are regulatorybarriers to subdividing, permitting and building on land

11 When assigning parcels to census tracts and block groups, we utilizethe tract and block group definitions from the 2000 Census.

12 Only homes on lots less than one acre in size are included in thesample. In general, including larger homes tended to depress the implicitprice of land, increasing the regulatory tax. This could possibly reflect a biasin that homes situated on very large lots are located in areas where land isinexpensive for some unobservable reason. We also filtered out sales forwhich the total living space or sales price per square foot appeared to beextreme. The final sample includes only homes with total living spacebetween 600 and 6000 square feet and with price per square foot valuesbetween $20 and $250.

is precisely why a wedge is formed between the intensiveand extensive values of land.

Although the theoretical foundations of the implicitmarket valuation approach are well-established (Rosen,1974), theory provides little help in specifying the func-tional form of the hedonic function. As our interest is notin the values of each of the hedonic coefficients per se,but rather using these estimates to estimate the value con-sumers place on additional yard space, special attentionwas paid to how estimates of the regulatory tax variedacross empirical specifications. The summary measures ofthe regulatory tax and the results from the decomposition(reported below) were remarkably stable across a numberof specifications including log-linear models, models inwhich the size of the lot is interacted with block groupdescriptors, and linear models that include a quadraticlot size term. Given the invariance of the regulatory costestimates across the models, for the sake of parsimony,we focus on the most easily interpretable model: a linearspecification augmented with a quadratic lot size term.

The unit of analysis is a single-family house that soldbetween 1995 and 2005, and the dependent variable isthe sales price. The key explanatory variable is lotsize, thesize of the lot on which the house is situated. Other controlvariables include (1) distance measures to the central busi-ness district and to the coast; (2) two house characteristics,living space and age; (3) dummy variables for quarter ofsale to capture seasonal effects; and (4) dummy variablesfor the local jurisdiction.13 Table 3 summarizes the vari-ables used in the hedonic.

13 The unincorporated portion of a county is counted as a local jurisdic-tion and assigned a dummy variable accordingly.

Table 3Variables used in regulatory tax calculation.

1/DistCBD Inverse distance in miles to the central business district1/DistCoast Inverse distance in miles to the coast (recorded only if

county is coastal)totliv,totliv2 Interior living space and space squaredage,age2 Age and age squared of primary improvement on lotlotsize Size of lot in square feetlotsize2 Size of lot squaredsale Sale price of homeQ 4 � 1 vector of indicators for quarter of saleJ Vector of jurisdictional indicators

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 41

To allow for the intensive margin to vary across bothMSAs and over time, the following model is separately esti-mated for each MSA-year combination14:

sale ¼ aþ b11

DistCBD

� �þ b2

1DistCoast

� �þ c1lotsize

þ c2ðlotsizeÞ2 þ d1ageþ d2age2 þ f1totliv

þ f2totliv2 þ J þ Q þ e ð3Þ

Based on standard errors that are robust to heteroskedas-ticity and clustering at the block group level, the estimatesof the coefficient on lot size turn out to be precisely mea-sured.15 For each parcel in the sample, we use the estimateof the intensive margin, d cPðLÞ

dL , and the size of the lot, L, to esti-mate the implicit value of the land on which the home is sit-ting, d cPðLÞ

dL L. This serves as an estimate of rL in the equilibriumcondition (Eq. (2)).

The next step is to estimate the cost of construction ofeach home, bK . GG and GGS used indirect methods to esti-mate bK ; specifically, they used data from the companies RSMeans and Marshall and Swift to estimate the cost persquare foot of living space for homes of various qualities.Somerville (2004) notes that the major drawback of thisapproach is that it requires ad hoc assumptions regardingthe quality of construction. Furthermore, even if the qual-ity of construction is correctly assumed, simply using dataon the cost of constructing the primary structure of thehouse is likely to underestimate the true construction costof all the improvements on the property. Even homes oflow quality construction may have special features suchas pools, decks and sheds. Failing to account for the valueof these improvements will bias the tax upwards acrossall home qualities.

One of the primary strengths of our data is that for eachparcel, the county appraiser’s office reports the replace-ment costs, accounting for depreciation, of all of theimprovements on a given parcel; we use this as our mea-sure of bK . These improvements include the main structureas well as any special features, such as a pool, garage ordeck.16 The detail involved in generating these replacement

14 Note that we use a reciprocal transformation to capture the relation-ship between price and distance to the CBD (coast). This transformationassumes that price decreases at a decreasing rate as distance increasesbetween the property and the CBD (coast). As such, it has intuitive appealand is consistent with the standard urban model.

15 The hedonic regression results are available upon request.16 More information on the data can be found at http://dor.myflori-

da.com/dor/property/appraisers.html.

values is substantial. After an improvement that requires apermit is recorded on a parcel, the county appraiser mustphysically inspect the property. The appraiser then uses acombination of information on national and local construc-tion costs in order to estimate the cost of replacing all ofthe improvements on the property under current factor in-put cost conditions. For the main structure, these cost esti-mates reflect the quality and size of construction and thetype of exterior materials used. Quality is usually gradedon a scale from 1 (well below average) to 6 (well above aver-age). For special features such as pools and decks, the qualityof construction is also taken into account. The total improve-ment value for the property is then adjusted to reflect struc-tural depreciation.17 There is also a legal requirement forappraisers to physically inspect the property at least onceevery five years, regardless of whether a permitted improve-ment has been recorded.

Of course, the reliability of bK is only as good as the ap-praiser’s accuracy in determining the quality of theimprovements. Unobservable features may bias our esti-mates of the construction cost, and hence our estimatesof the regulatory tax, on two dimensions. The first dimen-sion is that they may affect our estimates at a given pointin time. For instance, some improvements are only ob-served after the appraiser’s periodic on-site inspectionhas occurred. Hence, appraised values lag improvementsbecause there are delays in updating the record ofimprovements. Another potential source of unobservablescomes from interior improvements that do not require abuilding permit, such as new floors or new appliances. Be-cause the appraiser cannot account for these interior up-grades, the construction cost estimate will beunderestimated. This error may be magnified in high-endhouses because as homes become more valuable, the morevaluable the unobservable improvements are likely to be.

The second dimension is that the bias caused by unob-servable improvements may be exacerbated over time. Inperiods of rapid price appreciation, home improvements,both observed and unobserved by the appraiser, may be-come more popular if homeowners take advantage of equi-ty loans to finance improvements. In addition, householdsmay substitute towards those upgrades and remodelingprojects that do not require permits if regulations becomemore onerous.

While acknowledging the potential biases associatedwith the inability of the appraiser to observe all homeimprovements, we argue that to the extent that interiorimprovements usually cost much less than observedimprovements (for example, a room addition), our replace-ment cost values should not be subject to serious measure-ment error. We also note that our estimated replacementcosts still represent a substantial improvement over previ-ous work, which generally has relied on metropolitan-levelconstruction cost tables.

17 Depreciation rates are based on the actual age of construction for eachindividual improvement. For instance, suppose there are two improve-ments on a parcel: a house that is ten years old and a swimming pool that istwo years old. The depreciated value of the total improvement value of theproperty reflects the fact that the improvements are of different ages.

19 We also estimated our hedonic model with census tract fixed effects inlieu of jurisdictional fixed effects; results are not qualitatively verydifferent.

20 More specifically, we estimate the value of this home in one-tenth of amile increments, moving progressively farther away from the CBD. We didexperiment using finer step size increments for a number of MSAs. Theresults from these experiments were virtually identical to the estimatesunder the one-tenth of a mile step size.

21 For parcels beyond the urban fringe, the urban access amenity value isset to zero.

22 We use the word ‘‘amenity,” but we do allow both the proximity to theCBD and proximity to the coast to be disamenities. This is not common, butfor some MSA/year combinations, we do find negative amenity effects.

23 As the fringe moves outward, the amenity value of a parcel at a givendistance from the CBD (coast) increases in value, as predicted by thestandard urban model.

24 We also used an alternative method to account for amenity values byusing the census tract fixed effects in our hedonic to stand for A. Thisassumes that the amenity component is identical throughout the tract andinvariant to lot size. When we net this tract fixed effect out, the regulatorytax we derive captures that portion of the regulatory tax that is orthogonalto the amenity value. We interpret bT A estimated using these tract fixedeffects as a lower bound estimate of the regulatory tax because A willsweep out whatever is common across homes within the census tract. Inthis case, A not only represents amenity values but also incorporates a

42 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

Given our estimate of the consumption value of the lotand the value of all improvements, the regulatory tax iscalculated as follows:

bT ¼ Sale Price� bK � d dPðLÞdL

L: ð4Þ

We call this bT the ‘‘uncorrected regulatory tax” on a parcel.

4. Correcting for amenity effects

An important issue that arises with our methodology iswhether bT from Eq. (4) is entirely attributable to land-useregulation. The model above assumes that all land ishomogeneous, and there is no price differential in the costand consumption value of a square foot of lot. If some par-cels in the sample are located in areas that command alocational premium, however, these assumptions are vio-lated. As a result, the uncorrected regulatory tax will over-state the effect of regulatory stringency on parcels thatcommand locational premia. We now present an alterna-tive approach to estimating the regulatory tax that correctsfor such amenity differentials.

If parcels of land differ in an amenity value A that isunmeasured and orthogonal to the land consumption va-lue, the price of the house, net of implicit land value (rL)and construction costs (K), will comprise the amenity value(A) as well as the regulatory tax. To accurately estimate theregulatory tax, an estimate of A (bA) must be included in theright hand side of Eq. 4, which implies

bT A ¼ Sale Price� bK � d dPðLÞdL

L� bA: ð5Þ

If we do not net out the amenity component, we will tendto overestimate the regulatory tax.18 Looking at priceappreciation over time, we may attribute too much of theappreciation to regulatory tax increases, when in fact itmay be the amenity value that is appreciating. There aremany sources of locational premia within metropolitanareas, but arguably the most important are CBD and coastalaccess. We therefore treat the amenity value of a parcel as afunction of its proximity to the central business district(CBD) and, for a parcel in a coastal county, its proximity tothe coast. Parcels located farther away from the CBD (orthe coast) will command lower prices, as consumers requirea compensating price differential for costly commutes. Bycomparing two otherwise identical homes, one located atthe urban fringe (f) and another located d miles from theCBD, with d < f, we can estimate the amenity value associ-ated with access to the business district at distance d asthe difference in the values of the two homes. An analogousprocedure can be used to estimate the amenity value associ-ated with beach access. We can then estimate A as the sumof the beach and CBD access premia. With bA in hand, weestimate the implicit value of the lot as the sum of this ame-

18 GG and GGS do not explicitly consider the amenity effect, but they hintat its importance. Presumably, they are not overly concerned with this issuebecause they estimate the tax for the average house within the metropol-itan area and they implicitly assume that the supply of lots at the MSA levelis perfectly elastic. This implies that when they compare across MSAs, theyare measuring only the difference in T between areas.

nity value and the pure consumption value of land(bA þ d cPðLÞ

dL L).We utilize the estimated coefficients from the hedonic

price (Eq. (3)) to operationalize this amenity correction.19

The first step in the process is to estimate the location ofthe urban and coastal fringes. To locate the urban fringe,we predict the value of an otherwise-similar home locatedprogressively farther from the CBD using the coefficient onthe inverse distance term (cb1 ) from the hedonic.20 We thencompare the difference in the estimated value of this homeat consecutive distances (e.g., the value of the home at d = 1and d = 1.1). We define the urban fringe (denoted f) as thatpoint at which this value difference is $100 or less. For eachparcel in the sample, we then estimate the price of the par-cel at the urban fringe and the price of the parcel at its actuallocation. The difference in these predicted values then servesas our estimate of the parcel’s urban access amenity.21 Forcoastal MSAs, we repeat this procedure using the coefficienton the inverse coastal distance term (cb2 ) from the hedonic.As in the case of CBD access, a parcel’s coastal access valueis estimated as the difference between the estimated valueof the parcel at the ‘‘coastal fringe” and the estimated valueof the parcel at its actual location. The total amenity effect(A) is the sum of the CBD and coastal effects.22

As we repeat this amenity correction procedure for eachMSA-year combination, we allow A to vary across spaceand time. Additionally, our procedure allows for the urbanand coastal fringes to change over time in response tochanges in macroeconomic conditions such as populationor income growth.23 After estimating A, we calculate bT A

using Eq. (5). In what follows, we refer to bT A as the ‘‘ame-nity-corrected regulatory tax.”24

common regulatory component. That said, it is possible that regulatorytaxes may still differ even within an area as small as the census tract, as inpractice there is often a great deal of idiosyncratic negotiation betweendevelopers and municipal officials. As expected, the results from thisalternative correction generally give much smaller estimates of theregulatory tax, but nonetheless still suggest that the tax exists and isincreasing overtime for most of the MSAs. We do not report results fromthis correction, but they are available upon request.

Table 4Tallahassee MSA: mean values for regulatory tax calculations. Extensiveand intensive margins are expressed in square foot terms. Implicit landvalue and regulatory taxes are expressed in dollars.

Tallahassee 1995 2005

Uncorrected Amenity Uncorrected Amenity

Extensive margin 3.70 8.05Intensive margin 1.32 1.47Implicit land value 11,961 12,464 13,879 15,143Regulatory tax 19,306 18,803 45,656 44,392Tax/sale price 0.17 0.16 0.22 0.21Observations 3460 5632

Table 5Lakeland MSA: mean values for regulatory tax calculations. Extensive andintensive margins are expressed in square foot terms. Implicit land valueand regulatory taxes are expressed in dollars.

Lakeland 1995 2005

Uncorrected Amenity Uncorrected Amenity

Extensive margin 3.45 6.33Intensive margin �0.01 1.27Implicit land value �278 �355 11,360 11,414Regulatory tax 32,601 32,677 43,269 43,215Tax/sale price 0.40 0.40 0.21 0.21Observations 4898 14,242

Table 6West Palm Beach MSA: mean values for regulatory tax calculations.Extensive and intensive margins are expressed in square foot terms.Implicit land value and regulatory taxes are expressed in dollars.

West Palm Beach 1995 2005

Uncorrected Amenity Uncorrected Amenity

Extensive margin 7.58 19.83Intensive margin 4.39 4.56Implicit land value 37,668 44,684 37,725 36,068Regulatory tax 38,083 31,067 132,860 134,517Tax/sale price 0.09 0.01 0.34 0.35Observations 8577 14,547

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 43

5. Estimation results

5.1. Estimates by MSA and by year

Because of space constraints we do not present numer-ical results for each MSA and for each year in our sample.25

Rather, to motivate the discussion, we report summarymeans for three MSAs – one large (West Palm Beach), onemedium (Lakeland) and one small (Tallahassee) – and onlyfor 1995 and 2005. Later, however, results are presentedand discussed graphically for all MSAs and years.

Tables 4–6 present, for each of the three MSAs, summarymeans of the regulatory tax calculations without and withthe corrections for amenity effects.26 The ”extensive margin”measures the per square foot price of the house exclusive ofconstruction costs, while the intensive margin measures theper square foot consumption value of the land. The intensivemargin is quite small, both in absolute value and relative tothe extensive margin; as such, the magnitudes are consistentwith GG’s findings for Florida MSAs. This large difference be-tween the prices on the two margins reflects a wedge thatcould be attributable to the costs of regulation.

While remaining relatively small, the intensive margindid rise substantially in a number of MSAs over the decade,indicating that in some areas the value attached to a largerlot is rising. Of our three representative MSAs, the percent-age change in the intensive margin has been most substan-tial in Lakeland. This increase may be attributable to atransition from an area highly dependent on phosphate min-ing and citrus farming to a bedroom community for com-muters to Tampa and Orlando. The change in the intensivemargin was much smaller in Tallahassee and West PalmBeach. Relative to the intensive margin, the estimatedextensive margins are quite large and have grown muchmore rapidly over time. This is true for our three representa-tive MSAs, as well as the full sample of MSAs.

Focusing now on the taxes themselves, we see that forall three metropolitan areas, the mean regulatory tax issubstantial in absolute dollars, ranging from $19,306 inTallahassee in 1995 to $132,860 in West Palm Beach in2005. As a percentage of sales price the tax is also large,ranging from 9% in West Palm Beach in 1995 to 40% inLakeland in 1995. Looking at the change in the taxover time shows a substantial increase in all MSAs. In WestPalm Beach and Tallahassee, the growth of the regulatorytax without the amenity correction has substantially outp-aced housing price growth. This is reflected in the fact thatthe mean ratio of tax-to-sale price has increased between1995 and 2005. In these two MSAs, it appears that the costsof complying with regulation now represent a higher per-centage of the home value than they did ten years ago. InLakeland, though the mean regulatory tax has grown overthe period, the average tax-to-value ratio in 2005 was lessthan half the size of the 1995 tax-to-value ratio.

Switching to the amenity-corrected regulatory taxes,there is little change in the above conclusions. The tax re-

25 Although they are available upon request.26 The results reported are based on estimates from Eq. (3). Alternative

specifications, including models that allow for census tract fixed effects,produced very similar results.

mains large in magnitude and has grown substantially overtime. However, the effect of the amenity correction on theestimated regulatory tax varies by MSA. In West Palm Beach,the effect of regulation in 1995 is substantially attenuatedwhen we correct for parcel-level access amenities, withthe average tax falling by approximately 18% after the ame-nity correction. Parcel-level access premia appear to bemuch less important in Lakeland and Tallahassee, however,as the amenity-corrected and uncorrected estimates of theaverage regulatory tax are virtually identical. The differencebetween the corrected and uncorrected models appears tobe even less important in 2005, with little difference be-tween the two estimates of regulatory costs in each of thethree MSAs. These results suggest that although there is gen-erally a large locational premium for individual parcels lo-cated close to the CBD and the coast, when averagingacross all parcels at the metropolitan level, CBD and beachaccess have little effect on the average price.

The close relationship between the uncorrected and thecorrected estimated regulatory taxes is borne out by exam-ining the 20 MSAs together. The mean regulatory tax-to-

Fig. 3. Ratio of mean regulatory tax to value by MSA (1 of 2).

27 Although selecting homes that sold both in 1995 and 2005 may seemtoo limiting, this was not the case. In the Tallahassee MSA, 8% of the homesthat sold in 1995 were also sold in 2005. In the Lakeland and West PalmBeach MSAs, this figure is 5.5% and 6.3%, respectively.

44 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

value ratio for each MSA between 1995 and 2005 is plottedin Figs. 3 and 4. The dashed line represents TA as the mea-sure of regulatory cost, while the solid line is the uncor-rected ratio using T as the measure of regulatory cost. Inthe majority of metropolitan areas, these two trend linestrack each other very closely, though, as expected, theamenity-corrected ratio is generally lower than its uncor-rected counterpart. The only instances of relatively largedivergences between the corrected and uncorrected ratioestimates are MSAs located in southern, coastal Florida(e.g., Fort Lauderdale, West Palm Beach, and Miami-Hialeah).

As the figures show, in 12 of the 20 MSAs, the averagetax to sales price ratio increased between 1995 and 2005.The increases are particularly large in Ocala, West PalmBeach, Orlando, and Panama City. A common feature ofthese metropolitan areas is that, except for Panama City,they are among the five fastest growing metropolitan areasin the state (as measured from 1990 to 2000 with Censusdata). This is not surprising, because, as noted earlier,restrictive supply-side regulations have their greatest ef-fect on housing prices where demand is strongest.

5.2. Appreciation decomposition

The results above suggest that the driving force of priceappreciation over time may differ substantially across dif-

ferent Florida housing markets. In metropolitan areas withincreasing regulatory tax-to-value ratios (such as WestPalm Beach), it appears that appreciating property valuesmay be due to increasingly stringent regulatory environ-ments. On the other hand, appreciation in areas for whichthis ratio is changing little over time (such as Miami) ap-pears to be driven by increasing land values, constructioncosts, or amenity values.

The multi-year nature of our dataset allows us to disen-tangle the relative importance of the regulatory cost, landcost and construction cost components of price apprecia-tion over the sample decade. Without accounting for ame-nities, the change in home value can be decomposed asDP = Dr + DK + DT. The share of a home’s appreciation thatcan be attributed to increasing regulatory, land and con-struction costs can thus be estimated as DT

DP ;DrDP, and DK

DP,respectively. To do our decomposition, we first estimatethe regulatory tax and intensive margin for each parcel ineach year as described above. We then select those parcelsthat have sales occurring in both 1995 and 2005 and calcu-late the various components of the total price increase sep-arately for each MSA.27

Table 7House price appreciation decomposition.

MSA Obs. Uncorrected Amenity correctionShare of appreciation Share of appreciation

(1) Land (%) (2) Const. (%) (3) Regul. (%) (4) Land (%) (5) Const. (%) (6) Regul. (%)

Tallahassee 290 1.8 71.0 27.2 3.4 71.0 25.6Lakeland 269 14.9 72.5 12.6 15.2 72.5 12.3West Palm Beach 541 0.1 45.3 54.6 �2.6 45.3 57.3

Fig. 4. Ratio of mean regulatory tax to value by MSA (2 of 2).

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 45

Columns (1) to (3) of Table 7 report summary results forour three representative MSAs: Tallahassee, Lakeland andWest Palm Beach.28 The key finding is that regulatory costappreciation accounts for a significant share of the overallprice increases, ranging from around 13% in Lakeland to over50% in West Palm Beach. In Tallahassee and Lakeland, con-struction cost increases account for about 70% of the totalhouse price appreciation, probably reflecting the similarityof construction costs across markets throughout the state.The share of appreciation attributable to construction wassomewhat lower in West Palm Beach, with physical costsexplaining approximately half of the price increase. Finally,it is interesting to note that the regulatory share is larger

28 The appreciation decomposition figures reported are the averageappreciation shares, with the mean taken over all sales occurring in both1995 and 2005.

than the land share in two of the three MSAs. The value ofland in the Tallahassee MSA accounts for only about 2% ofthe total price appreciation, presumably due to the availabil-ity of developable land in the Florida Panhandle region. Theimplicit land value appears to have risen even more slowlyin West Palm Beach as the estimated land share is less than1%. In Lakeland, however, it appears that the intensive mar-gin rose much more quickly, accounting for almost 15% ofappreciation.

The percentages in the first three columns of Table 7 alltell a similar story; namely, that the increases in the valueof being able to build on the land (i.e., the value of havingsatisfied the land use regulations) make an important con-tribution to house price appreciation within our three MSAsample. However, there remains the possibility that theland value component of appreciation has been underesti-mated (and thereby the regulatory component overesti-

46 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

mated) by not correcting for possible increases in the ame-nity value of land. We examine this issue in the next threecolumns of the table.

In a manner parallel to the previous section, if we accountfor the fact that the price of a home reflects the amenity va-lue of the land (as distinct from the pure consumption valueof the land), then our decomposition identity isDP = Dr + DK + DA + DTA. Should the amenity value beappreciating over time, we would expect the land share ofappreciation to be larger using this specification.29 Columns(4) to (6) of Table 7 show the results. The amenity-correctedland share almost doubles in Tallahassee, though the cor-rected land share still explains less than 4% of the appreciationover the period. The regulatory component falls slightly from27.2% to 25.6%. In West Palm Beach, the amenity (or disame-nity) correction reduces the land share from 0.1% to �2.6%,resulting in an even larger appreciation share attributable toregulation.30 Finally, the amenity correction appears to makelittle difference in Lakeland as the uncorrected and amenity-corrected estimates are virtually identical. In all three MSAsthen, the amenity correction does not substantively changethe regulatory component. The fact that large estimated reg-ulatory components remain suggests that regulatory factorshave contributed substantially to home price appreciation.31

To expand the analysis to all twenty Florida MSAs, wepresent graphics of the decomposition in Fig. 5. For eachMSA, we present the decomposition for the uncorrectedmodel in the left bar graph (labeled S for the standardmodel) and for the amenity-corrected model in the rightbar graph (labeled A). The dark bars represent the propor-tion of the price appreciation that we attribute to the localregulatory environment. Comparing the size of the bars,we see that regulation has contributed to increasing pricesin MSAs throughout the state, though the magnitude ofthis regulatory share exhibits substantial variance acrossmarkets, generally ranging from 10% to 50%. This resultholds even with our more conservative amenity-correctedspecification. Interestingly, the land component tends to besmall and in some MSAs (e.g., Tallahassee and Tampa), al-most negligible; this underscores the importance of sepa-rating the implicit value of land from the regulatorycompliance value of land. It is not the consumption noramenity value of land that is driving up prices, but ratherthe value attached to being able to build on that land.

29 Note that when adding the estimate of amenity value, the portion ofappreciation attributable to land value (through consumption and accessamenities) will be DrþDA

DP .30 In this decomposition exercise, nothing precludes a component from

having a negative effect on property values. For instance, if the implicitvalue of land declines over the period, this may result in a depreciation ofthe land component of the home value.

31 It may be the case that parcels selling in both 1995 and 2005 are notrepresentative of the entire housing market, in which case our estimate ofthe portion of appreciation attributable to regulation would be biased. As acheck on this, we compared the 1995 and 2005 average tax/price ratios ofhomes that were used to calculate the appreciation decomposition (thedecomposition sample) with the 1995 and 2005 mean tax/price ratiosreported in Tables 4–6 (the full sample). For our three sample MSAs(Lakeland, Tallahassee, and West Palm Beach), the full sample anddecomposition sample ratios were similar in magnitude, suggesting thatthe cost of regulation does not differ substantially between the full anddecomposition samples.

As expected there is a correspondence between Fig. 5 andFigs. 3 and 4. Generally, in metropolitan areas where the tax/value ratio has grown the most, the tax also explains a rela-tively large share of house price appreciation. But as notedabove, both sets of figures demonstrate that the growth inthe regulatory tax has not been uniform across metropolitanareas. The expectation is that the tax/value ratio will in-crease the most and the percentage of the appreciationattributable to the tax will be the greatest where there existsa confluence of strong demand and highly restrictive regula-tion. Generally, the results are consistent with this expecta-tion. For example, West Palm Beach displays one of thelargest increases in the tax/value ratio and the tax also ac-counts for a relatively large share of its house price appreci-ation. This metropolitan area is both heavily regulated (ithas the highest value, 7, on the Ihlanfeldt index reported inTable 2) and had the third highest population growth of Flor-ida MSAs from 1990 to 2000 (only Naples and Orlando grewfaster). At the other end of the growth (in the bottom five interms of population growth) and regulatory spectrum (in-dex value of 3) is Lakeland, where the tax/value ratio de-clined over the decade and the tax accounts for a verysmall portion of house price appreciation.

As the accuracy of replacement costs are of paramountimportance in the calculation of the regulatory tax, a largeportion of homes for which these cost estimates are unreli-able could possibly pollute our measure of the effect of reg-ulation on housing values. One way to test the robustness ofour decomposition results is to eliminate older homes fromthe sample, as accurately appraising such structures is likelyto be far more difficult than estimating replacement costs fornewly built homes. To that end, of the homes that sold inboth 1995 and 2005, we restrict the sample to homes thatwere constructed after 1990 and recalculate the apprecia-tion shares. The results of the decomposition exercise usingthis restricted sample are reported in Table 8. A comparisonof the results in Tables 7 and 8 suggests that the decomposi-tion estimates are not very sensitive to the inclusion of olderproperties in the sample.

6. Conclusion

Home values increased substantially over the decade(1995–2005) analyzed in this paper, and this appreciationwas particularly sizeable in the state of Florida. While de-mand for housing was undoubtedly a driver of the pricerun-ups, theory suggests that this appreciation could beexacerbated by three broad, supply-sided factors: increas-ing construction costs, higher land costs and more strin-gent regulatory environments.

In this paper we applied the regulatory tax methodol-ogy of GG and GGS to a rich set of parcel-level tax roll data.These data allowed us to more accurately estimate con-struction costs and thereby obtain more reliable estimatesof the regulatory tax. We find that, regardless of the metro-politan area, the tax is an important component of theprice of a home within the state of Florida, although thereis considerable variation in the size of the tax componentacross these areas. These results are in-line with those re-ported by GG and GGS.

-50

050

100

-50

050

100

-50

050

100

-50

050

100

S A S A S A S A S A

S A S A S A S A S A

S A S A S A S A S A

S A S A S A S A S A

Bradenton DaytonaBeach FortLauderdale FortMyers FortPierce

FortWaltonBeach Gainesvil le Jacksonvil le Lakeland Melbourne

Miami Naples Ocala Orlando PanamaCity

Pensacola Sarasota T allahassee T ampa W estPalmBeach

Tax Land

Construction

Per

cen

tag

e o

f Ap

pre

ciat

ion

S: Standard ModelA: Amenity Correction Model

Fig. 5. Decomposition of price appreciation from 1995 to 2005.

R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48 47

Going beyond GG and GGS, we addressed the issue ofthe importance of the regulatory tax in explaining the sub-stantial rise in housing prices that occurred in Florida over

the 1995-2005 time period. We decomposed the overallhouse price increase into land, materials and regulatorycomponents and found that increases in the regulatory

Table 8House price appreciation decomposition: properties built after 1990.

MSA Obs. Uncorrected Amenity correctionShare of appreciation Share of appreciation

(1) Land (%) (2) Const. (%) (3) Regul. (%) (4) Land (%) (5) Const. (%) (6) Regul. (%)

Tallahassee 123 1.7 72.6 25.7 2.5 72.6 24.9Lakeland 80 12.8 74.2 13.0 12.8 74.2 13.0West Palm Beach 98 0.3 49.4 50.3 �0.5 49.4 51.1

48 R. Cheung et al. / Journal of Housing Economics 18 (2009) 34–48

tax represents from 5% to 50% of this run-up in houseprices, depending on the locality.

Regulation plays an important role in rising housingprices in many of Florida’s metropolitan areas because oftwo mechanisms. The first comes from the increasing biteof the land development regulations adopted in the early1990s by local governments in order to implement theircomprehensive plans, mandated by the state in the 1985Growth Management Act. All local governments were re-quired to adopt regulations, but the state gave local gov-ernments considerable latitude in their construction. Theimpact of some of these regulations (e.g., urban growthboundaries) grows over time, as the constraint imposedby the regulation becomes more binding. Hence, evenwithout more regulations, with growing demand more ofthe increases in housing prices can be attributed to extantregulation. The second mechanism is more direct: therehave also been incremental changes in land use regulationsin most Florida communities, as more and more haveadopted growth boundaries, impact fees, and other landmanagement techniques.32 This has also contributed tothe role played by the regulatory tax in explaining Florida’srun-up in housing prices.

What has happened in Florida is not unique. For exam-ple, by our count at least 15 other states have passed someform of growth management or smart growth legislation.33

These laws have increased the degree of land use regulationwithin these states, allowing for the possibility that housingprices are being pushed upward by the regulatory tax. Fu-ture research is needed on states other than Florida in orderto document these trends. Where the appropriate data exist,our methodology can be replicated for this purpose.

In closing, we wish to emphasize that our focus hasbeen on the effects that land use regulations have on hous-ing supply. Regulations are also expected to affect housingdemand, by improving the quality of local amenities. In or-der to carefully document the costs and benefits of regula-tions, future research is needed that looks at regulations’effects on both sides of the market.34

32 The intertemporal changes in impact fees have been particularlywidespread. Between 1995 and 2005, 32 of Florida’s 67 counties eitheraltered or adopted residential impact fees, with a total of 108 such changesand adoptions occurring over the period.

33 These states (and the year of the initial legislation) are Arizona (1998),California (1965), Colorado (2000), Georgia (1989), Hawaii (1961), Maine(1988), Maryland (1992), Minnesota (1994), New Jersey (1986), Oregon(1973), Rhode Island (1988), Tennessee (1998), Vermont (1988), Washing-ton (1991), and Wisconsin (2000).

34 A recent study that estimates the effects of comprehensive planning onthe demand for housing, but not the supply of housing, is by Ihlanfeldt(2009).

References

Brueckner, Jan., 1998. Testing for strategic interaction among localgovernments: the case of growth controls. Journal of UrbanEconomics 44 (3).

Chapin, Timothy S., Connerly, Charles E., Higgins, Harrison T., 2007.Growth Management in Florida: Planning for Paradise. AshgatePublishing Limited, Burlington VT.

Downs, Anthony, 1991. The advisory commission on regulatory barriersto affordable housing: its behavior and accomplishments. HousingPolicy Debate 2 (4).

Glaeser, Edward L., Gyourko, Joseph, 2003. The impact of zoning onhousing affordability. Economic Policy Review 9 (2).

Glaeser, Edward L., Gyourko, Joseph, Saks, Raven, 2005. Why have housingprices gone up? National Bureau of Economic Research WorkingPaper #11129.

Glaeser, Edward L., Gyourko, Joseph, Saks, Raven, 2005b. Why ismanhattan so expensive? Regulation and the rise in housing prices.The Journal of Law and Economics 48 (2).

Ihlanfeldt, Keith, 2007. The effect of land use regulation on housing andland prices. Journal of Urban Economics 61 (3).

Ihlanfeldt, Keith, 2009. Does comprehensive land use planning improvecities? Land Economics 85 (1).

Malpezzi, Stephen, Chun, Gregory H., Green, Richard, 1998. New place-to-place housing price indexes for US metropolitan areas, and theirdeterminants. Real Estate Economics 26 (2).

Malpezzi, Stephen, 1996. Housing prices, externalities, and regulation inUS metropolitan areas. Journal of Housing Research 7 (2).

Mayer, Christopher J., Somerville, C. Tsuriel, 2000. Residentialconstruction: using the urban growth model to estimate housingsupply. Journal of Urban Economics 48 (1).

Pendall, Rolf, Puentes, Robert, Martin, Jonathan, 2006. From traditional toreformed: a review of the land use regulations in the nation’s 50largest metropolitan areas. Brookings Institution Metropolitan PolicyProgram, Washington, DC.

Phillips, Justin, Goodstein, Eban, 2000. Growth management and housingprices: the case of Portland, Oregon. Contemporary Economic Policy18 (3).

Quigley, John M., Rosenthal, Larry A., 2005. The effects of land useregulation on the price of housing: what do we know? What can welearn? Cityscape 8 (1).

Rosen, Sherwin, 1974. Hedonic prices and implicit markets: productdifferentiation in pure competition. The Journal of Political Economy82 (1).

Somerville, C. Tsuriel, 2004. Zoning and affordable housing: a criticalreview of Glaeser and Gyourko’s paper. Canada Mortgage andHousing Corporation Research Report CR 6665-70.