The Politics of Adaptation: Subsistence Livelihoods and Vulnerability to Climate Change in the...

Transcript of The Politics of Adaptation: Subsistence Livelihoods and Vulnerability to Climate Change in the...

The Politics of Adaptation: Subsistence Livelihoodsand Vulnerability to Climate Change in the KoyukonAthabascan Village of Ruby, Alaska

Nicole J. Wilson

Published online: 29 November 2013# Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract The concepts of vulnerability and adaptation havecontributed to understanding human responses to climatechange. However, analysis of the implications of the broaderpolitical context on adaptation has largely been absent.Through a case study of the subsistence livelihoods ofKoyukon Athabascan people of Ruby Village, this paperexamines the implications of adaptation to the social changesprecipitated by colonization for the articulation of currentresponses to climate change. Semi-structured interviews, sea-sonal rounds, and land-use mapping conducted with 20 com-munity experts indicate that subsistence livelihoods are ofcontinued importance to the people of Ruby in spite of thedramatic social change. While adaptive responses demon-strate resilience, adaptation to one form of change can increasevulnerability to other kinds of perturbations. Research find-ings illustrate that a historical approach to adaptation canclarify the influence of the present political context on indig-enous peoples’ responses to impacts of climate changes.

Keywords Adaptation . Climate change . Equity and justice .

Indigenous peoples . Subsistence livelihoods . Vulnerability .

Alaska

Introduction

Arctic and subarctic regions of the world are experiencingsome of the most extreme impacts of climate change (Nuttallet al. 2005). Although local impacts vary widely (Nuttall et al.2005), climate change poses substantial risks to indigenouspeoples across the Arctic and Subarctic (ACIA 2005). Manyof these risks are associatedwith subsistence livelihoods, which

continue to have sociocultural and ecological significance forindigenous peoples (Kassam 2009; Wheeler and Thornton2005). A large number of studies document the impacts ofclimate change on indigenous peoples of the Arctic andSubarctic, primarily from the perspective of vulnerability andadaptation (ACIA 2004; Herman-Mercer et al. 2011; Kassam2009; Krupnik and Jolly 2002; Nichols et al. 2004; Reidlingerand Berkes 2001).

Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change

While mitigation continues to be important in addressing theroot causes of climate change, the slow pace of politicalnegotiations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and evidencesuggesting that we are committed to a certain amount ofwarming has motivated a shift in focus toward adaptation(Ford and Smit 2004). Adaptation to climate change is broadlydefined as an “adjustment in natural or human systems inresponse to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects,which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities”(IPCC 2007:869). Adaptation can be planned or spontaneousand, depending on its timing, can be either anticipatory orreactive (IPCC 2007; Smit and Wandel 2006). It occurs atmultiple and interacting scales simultaneously (Adger et al.2005) and in response to diverse stimuli (Smit et al. 2000).

Recent scholarship on climate change draws on the theoryof vulnerability to explain why some populations are moreable to adapt than others (Adger and Kelly 1999; Agrawal andPerrin 2009; Ribot 1995). Vulnerability is defined as “thedegree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to copewith, adverse effects of climate change , including climatevariability and extremes. Vulnerability is a function of thecharacter, magnitude, and rate of change and variation towhich a system is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptivecapacity” (IPCC 2007:883). Other social and biophysical non-climatic drivers of change also contribute to vulnerability(Adger 2006).

N. J. Wilson (*)Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, Universityof British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, USAe-mail: [email protected]

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101DOI 10.1007/s10745-013-9619-3

The study of vulnerability is rooted in three theoreticalapproaches (Eakin and Luers 2006). First, the risk-hazardapproach to vulnerability comes from natural hazard literature(Burton et al. 1993; White 1973) and measures vulnerabilityas the difference between biophysical risk factors and poten-tial loss (Eakin and Luers 2006). Second, the political-economy or political-ecology approach examines vulnerabil-ity resulting from social inequalities and conflict in societies,emphasizing difference in vulnerability based on “exposureunits,” defined variously as class, ethnicity, etc., that are thebasis for differential entitlements (Eakin and Luers 2006;Turner et al. 2003). Third, the ecological resilience approachdefines vulnerability in the context of stresses acting oncoupled social and ecological systems where humans areconstantly interacting with the biophysical environment(Eakin and Luers 2006). C. S. Holling (1973) defines resil-ience as the ability of a system to absorb change and distur-bance without modifying its structure or relations. Resilienceis an important factor in determining the potential for societiesto adapt to environmental changes because “the adaptivecapacity of all levels of society is constrained by the resilienceof their institutions and the natural systems on which theydepend. The greater their resilience, the greater is their abilityto absorb shocks and perturbations and to adapt to change”(Berkes et al. 2003:14). Resilience is understood as the op-posite of vulnerability and must be taken into account in orderto avoid conceptualizing local communities as the passivevictims of change (Kassam et al. 2011). Because the charac-teristics of particular systems differ, understanding resiliencewithin those specific contexts is an important element ofanalysis of sociocultural and ecological systems (Turneret al. 2003). Since vulnerability is not only a function ofenvironmental or biophysical variability but also of sociopo-litical and institutional factors, the socio-ecological approachshould be applied to climate change analysis (Adger et al.2006; Agrawal and Perrin 2009; Turner et al. 2003).Consequently, the ecological resilience approach addressesthe weaknesses of the first two approaches to vulnerabilityby acknowledging both social and biophysical factorswithin a complex system. Most studies of vulnerabilityrepresent a combination of these three approaches (Eakinand Luers 2006).

The impacts of climate change on arctic and subarcticindigenous communities have been studied primarily from avulnerability perspective (Chapin III et al. 2004; Ford et al.2007; Ford and Pearce 2010; Ford et al. 2006; Kassam et al.2011; McNeeley 2011). However, the vulnerability approachcan be strengthened with more explicit attention to the ethicaldimensions of climate change adaptation (Adger et al. 2006).First, justice is central to adaptation due to the fact thatindigenous peoples are among the world’s populations thathave contributed the least to the causes of climate change yetare most affected by its impacts due to the close connection

between their livelihoods and their local ecology (Crate andNuttall 2009; Mearns and Norton 2010). Second, although theinfluence of politics on the adaptive cycles in socio-ecologicalsystems has to some extent been examined in the resilienceliterature (Carpenter et al. 2001), the study of vulnerabilityand adaptation has been critiqued for its failure to sufficientlyacknowledge the influence of the broader political context ona human community’s capacity to respond to change(Cameron 2011). Colonialism has had dramatic impacts onindigenous peoples. Given indigenous peoples’ documentedability to adapt to ecological change, it has been suggested thatsome of the largest barriers to climate change adaptation willbe political rather than ecological (Wenzel 2009). Therefore,understanding the political context within which indigenouspeoples are responding to the impacts of climate change addsfurther complexity to the analysis of justice in adaptation.

While there are many definitions of adaptation (Smit et al.2000), any discussion of adaptation requires clarification ofboth the units of analysis (who or what is adapting) and thespecific stimuli to which they are responding (adaptation towhat) (Smit et al. 2000). For the purpose of this analysis, Idefine adaptation as “a community-led process, based oncommunities’ priorities, needs, knowledge, and capacities,which should empower people to plan for and cope with theimpacts of climate change” (Reid et al. 2009:13).Community-led approaches to adaptation suppose that thereare many ways to respond to the impacts of climate changeand that local communities are the most qualified to determinetheir path to adaptation (Smit and Wandel 2006). While itmust be acknowledged that there is considerable diversitywithin communities (Kassam 2009), this research does notanalyze the influence of this diversity on adaptation. The studypresented here focuses on the political context for adaptationin Ruby Village, Alaska, by examining the influence of his-torical social changes on subsistence livelihoods and the bear-ing these changes have on the communities’ present responsesto climate change.

Context for Case Study of Ruby Village

Ruby Village is situated in the middle river region of theYukon River, in the interior of Alaska (64° 44′ 22.00″ N, -155° 29′ 13.00″ W) (Fig. 1). This region is characterized byplentiful bogs, streams, lakes and sloughs, open spruce for-ests, and shrubs and provides habitat for a rich variety of fishand wildlife including salmon, moose, diverse species ofmigratory waterfowl, bears, wolves, beavers, and other smallgame (Nelson 1986).

While the land and water surrounding Ruby Village hasbeen part of the traditional territory of the KoyukonAthabascans for millennia, the settlement itself was foundedas a supply point for gold prospectors during the miningbooms of 1906 and 1910 (Larson 2006). After WWII, most

88 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

miners had moved away and Ruby became primarily a nativevillage. The current population of Ruby is 166 persons, livingin 62 households. Approximately 87 % of the residents ofRuby are Alaska Native (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

The people of Ruby rely on their local ecology to maintainsubsistence livelihoods. Populations living in rural areas ofAlaska depend on wild foods to a greater extent than those inurban areas: wild foods provide approximately 57 % of thetotal calories and 396 % of required protein in rural Alaska,whereas wild foods provide 2 % of the calories and 15 % ofthe protein needs in urban areas such as Fairbanks andAnchorage (McNeeley 2011; Wolfe 2000). The location ofRuby Village off the Alaska road system means that it isdifficult and expensive to access other sources of food, whichhave to be flown in or shipped to the village via the YukonRiver barge system. For the people of Ruby, subsistence isviewed as a means not only to meet their basic nutritionalneeds but also to maintain their traditional “way of life”(Wheeler and Thornton 2005).

The climate of the interior of Alaska is characterized bynatural variability, including extremes in annual temperatures

and changes associated with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation(PDO), which causes decadal shifts in climate averages(Salinger 2005). Furthermore, populations of subsistence spe-cies fluctuate dramatically (Nelson 1986). Local subsistencelivelihoods are adapted to the natural variability of the climateand ecology of the interior of Alaska (Nelson 1986; VanStone1974), specifically by a high level of flexibility that allows forshifts in the timing, intensity, and location of harvestingdepending on climatic and ecological factors that vary annu-ally (Nelson 1986; VanStone 1974).

Climate change is projected to result in climatic extremesthat have not previously been experienced (ACIA 2004; IPCC2007). These changes are already being observed. For exam-ple, mean temperature increases indicate that arctic and sub-arctic regions are disproportionately experiencing the effectsof climate change (ACIA 2005; Hansen et al. 2006). Climatedata from the interior of Alaska indicate some of the mostmarked warming statewide over the last six decades (Salinger2005). Despite populations’ adaptation to climatic variability,unprecedented climate change has the potential to challengethe limits for adapting subsistence practices. This paper is

Fig. 1 The location of Ruby Village, Alaska in the Yukon River Basin

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 89

primarily concerned with the implications of past socialchanges for the people of Ruby’s vulnerability to the presentimpacts of climate change on subsistence livelihoods.

Methods

This study uses Participatory Action Research (PAR), an iter-ative approach to research used to generate knowledge throughcycles of action and reflection (Greenwood and Levin 2008).Furthermore, PAR is a fundamentally ethical research philoso-phy that informs research methods and design in order thatscience can serve as the basis for social change (Greenwoodand Levin 2008). The study can be characterized as participa-tory in the sense that it was designed and conducted in partner-ship with the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council(YRITWC), whose goal is to meet the needs of the 70 indig-enous governments they serve in the Yukon River Basin.Furthermore, the YRITWC facilitated a research partnershipwith the Ruby Tribal Council (RTC). The project was modifiedto fit the context of Ruby Village. All research outputs wereshared with and validated the RTC and the YRITWC.

Research was carried out during two field seasons, in 2010and 2011. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20community experts, including Elders, subsistence harvesters,and tribal administrators. Interviewees included eight womenand 12 men whose ages ranged from 49 to 92. Communityexperts were recruited using a snowball method (Patton 2002).Contacts at the RTC were asked to make a list of communityexperts who could contribute to the research, and individualswere added to the initial list when referred by individuals whohad already participated in the study. The community expertswere selected because they were considered knowledgeableabout subsistence practices and had lived in Ruby for anextended period of time.

A minimum of three meetings was held with each commu-nity expert. During an initial interview, participants wereasked to describe their subsistence livelihoods and observa-tions of social and ecological change. Specific follow-upquestions were asked to clarify responses. Interviews weredocumented using written field notes rather than audio record-ings. I wrote an interview narrative or an essay based oninterview field notes.

Seasonal rounds or annual calendars depicting the timingof 14 subsistence livelihood activities were created based oninterview data. Of the 20 community experts interviewed, 15opted to make seasonal rounds representing present subsis-tence practices. Three married couples created a seasonalround to show their combined harvesting. A total of 12 sea-sonal rounds resulted from this research. These calendarsinclude both the twelve-month Gregorian calendar and select-ed months from the Koyukon traditional lunar calendar (Jettéand Jones 2000).

Land use mapping was also conducted during interviews.Community experts were asked to place icons representingkey species, livelihood activities, and drinking water sourceson a 1:250,000 scale topographic map encompassing thetraditional territory of the people of Ruby Village.1 This mapwas then digitized using ArcGIS.

Typed versions of interview narratives, seasonal rounds,and the land use map were validated during a second inter-view. Interview narratives were read aloud to the communityexpert. At the time of validation, changes were made to eithercorrect information or add other important information left outat the time of the initial interview. A printed version of thedigitized land use map was also presented during follow-upinterviews, at which point additional icons and place nameswere added and feedback regarding the layout was gathered.During a third visit, each individual received final printedversions of interview narratives and seasonal rounds for theirrecords.

Interview narratives were coded for observations of changeusing Text Analysis Markup System (TAMS) Analyzer, aqualitative data analysis tool. The interpretation of this re-search was then shared with the community for validationduring a public presentation in Ruby Village in July 2011.Community experts consented to having their names used inthis research. Their names are used as a form of citation and torecognize the essential contribution their knowledge has madeto this research.

Results and Discussion

Adaptation is a pertinent topic for the people of Ruby, who arealready experiencing the impacts of climate change. Researchfindings indicate that the study of adaptation should includenot only seeking to understand the immediate impacts ofclimate change on subsistence livelihoods but also consider-ing the ways that the political and historical context in whichharvesting takes place influences a community’s ability torespond to these changes. The people of Ruby and theirsubsistence livelihoods have undergone dramatic socialchange since the 1950s that may have a continued effect ontheir capacity to adapt to the impacts of climate change.2 In theanalysis that follows, I briefly review the observed impacts ofclimate change on the subsistence livelihoods of the people of

1 Icons were adapted from land use mapping projects conducted inWainwright, Alaska, and Hay River, Northwest Territories (Kassam andthe Wainwright Traditional Council 2001; Kassam and the Soaring EagleFriendship Centre 2001).2 Significant social change occurred prior to this era, including during thegold booms of 1906 and 1910. At its peak, the population in the regionsurrounding Ruby is estimated to have been as high as 10,000 (Larson2006). However, the 1950s are used as a baseline for this study becausethe majority of changes in subsistence livelihoods identified by commu-nity experts occurred after this date.

90 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

Ruby. I then explore how the people of Ruby responded topast social changes and examine the implications of theseadaptations for their current responses to climate change.

Observed Impacts of Climatic Change on SubsistenceLivelihoods

Community experts are observing a wide variety of climaticchanges in the traditional territory of the KoyukonAthabascans of Ruby Village. These include changes in tem-perature, precipitation, permafrost thaw, erosion of riverbanks, river ice regimes, and fish and wildlife. These changesare in many cases consistent with those observed elsewhere inthe Arctic and Subarctic (ACIA 2004). The impacts of ob-served changes can be divided into four categories: access,predictability, safety, and species availability (Berkes andJolly 2001) (Table 1). While it is not the purpose of this paperto review these observations in detail, documenting the im-pacts of climate change is essential to the analysis of vulner-ability and adaptation to change in Ruby Village. For thispurpose, the specific impacts of the observed changes onmoose populations are discussed in depth later in this paper.The following section describes subsistence livelihoods inRuby prior to the 1950s and the people of Ruby’s responsesto the dramatic social changes that have occurred in recentdecades in order to gain insight into their present vulnerabilityto climate change.

Social Change and Subsistence Livelihoods

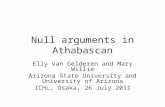

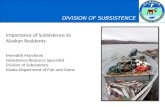

Subsistence livelihoods have changed for the people of Rubyin a number of ways since the 1950s. The current seasonalround for Ruby Village depicts the harvesting timing of thepeople of Ruby (Fig. 2). Seasonal rounds depict the timing of14 subsistence livelihood practices prior to the present (for adetailed description of these practices, see Appendix A). Landuse mapping illustrates the current spatial distribution of sub-sistence practices (Fig. 3).3 Data documenting current subsis-tence practices are compared to narratives of interviews withseveral Elders including Lorraine Honea, Clara Honea, BillyMcCarty, and Martha Wright, who were active subsistenceharvesters prior to the 1950s.

Interview narratives indicate that before the 1950s, thepeople of Ruby followed a seasonal pattern of migration,moving three to four times a year. Elders from Ruby Village,including Martha Wright and Lorraine Honea, referred to thisannual seasonal movement as the “cycle of life.” They wouldspend the winter months in winter camp, hunting and trapping

up the “Novi” River (Nowitna River) and the summer monthson the Yukon River, in the Village of Kokrines or at fish camp.Although the social changes the people of Ruby have experi-enced since the 1950s are numerous, three major onesinfluenced subsistence livelihoods during this time:sedentarization, intensified contact with the market economy,and the creation and enforcement of fish and wildlife regula-tions pertaining to subsistence harvesting.

In the 1950s, the people of Ruby stopped spending thewinters up the “Novi” and began to settle permanently.Sedentarization, or settlement in a central village locationrather than seasonal movement on the land, occurred as theresult of a number of influences including increased pressuresto enroll children in schools. Once people were required to puttheir children in school they could no longer spend the wholewinter in hunting and trapping camps as they used to. Theeffects of mandatory education on traditional seasonal migra-tion have also been noted among other Alaska Native peoples(Dombrowski 2001; Kawagley 1999). Due to this pressure,people began to settle more permanently in the village ofKokrines, and the majority of these residents moved to Rubywhen the Kokrines School was closed. Althoughsedentarization did not take place as the consequence of thesame overt government policies promoting settlement andrelocation that have been seen in the Canadian Arctic andSubarctic (Tester and Kulchyski 1994), mandatory educationlaws can be understood as an indirect, but nevertheless coer-cive, means of encouraging people to settle.

Increased contact with the market economy was anothermajor change that occurred for the population of Ruby afterthe 1950s. Assimilationist theories of cultural change led topredictions that indigenous cultures would be “‘lost’ throughassimilation to expanding Euro-American cultures” (Ericksonand Murphy 1998:74). Instead, cash and technologies such assnowmobiles have been actively integrated into subsistencepractices, which continue to constitute an important way oflife. The hybridization of traditional and market economies, inwhich cash resources become an important input into subsis-tence activities, has been referred to elsewhere as the creationof a “mixed economy” (Wenzel et al. 2000).

The introduction of new technologies was facilitated bycontact with the market economy and has had lasting impactson subsistence. Snowmobiles were introduced in RubyVillage during the late 1950s or early 1960s. The integrationof new technologies such as snowmobiles is seen as an adap-tive response to sedentarization by indigenous peoples(Wenzel 1991). While subsistence harvesters began to live ina central village location, snowmobiles allowed them to main-tain a modified seasonal round in spite of the social disrup-tions that accompanied the increased distance from traditionalhunting and trapping sites (Wenzel 1991). Although someElders, such as Lorraine Honea and her late husband JohnHonea, used dogs as their main method of transportation

3 Mapping for past land use was not conducted, but interviews reveal thatpresent land use is not as extensive as it used to be. However, the peopleof Ruby continue conduct subsistence livelihood activities within themajority of their traditional territory.

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 91

throughout their lives, travel over land in the winter is nowalmost exclusively by snowmobile.

The use of snowmobiles also had some negative conse-quences. These and other new technologies contributed to adependency on cash and fossil fuels in order to maintainsubsistence livelihoods. Emmitt and Edna Peters discussedtheir reliance on fossil fuels:

Gas for hunting is also expensive. Some people say thatit is almost too expensive to hunt. You have to have gasto hunt. The price of gas in Ruby is currently about$4.80 a gallon. In Galena, it is almost a dollar more thanRuby. So, subsistence becomes difficult, unless you aregoing up the river in a canoe.

Reliance on fossil fuels makes subsistence harvesters vul-nerable to fluctuations in the market economy. The impendingglobal fuel crisis highlights problems associated with depen-dency on fossil fuels that are likely to intensify.

Harvesting regulations have also had a major impact onsubsistence livelihoods. Koyukon Althabascans have a well-developed system of knowledge, practice, and beliefs regard-ing conservation of moose and other fish and wildlife (Nelson1986). Although the people of Ruby place importance on thecontinued use of Koyukon conservation practices, interviewnarratives reveal that the introduction of hunting and fishingregulations has substantially reduced local control over sub-sistence livelihoods, consequently diminishing the flexibility

to choose the timing, location, and intensity of harvesting.Junior Gurtler stated, “before if you wanted a moose youwould just hunt it.” Karen and Junior Gurtler commented onthe impacts that the enforcement of regulations have had onsubsistence livelihoods:

[The Alaska Department of] Fish and Game is givingout a lot of tickets. It didn’t used to be like that. You usedto be able to get what you needed and Fish and Gamewould only come every 5 years or so. Now they arecoming all the time. Now you have to have a license.

Regulations have seriously impacted subsistence by limitingharvesting practices to the open season and to a designated baglimit or a permittedmaximum, for example, formoose harvested.Failure to follow these regulations results in serious penalties.

Since the 1950s, subsistence regulations have changedsignificantly. Alaska Statehood in 1959 led to major alter-ations in subsistence regulations. The Statehood Act (1958)did not acknowledge the rights of Alaska Natives to land orproperty held in trust for them and gave the state the right toselect more than 103 million acres of lands they considered“vacant, unappropriated, and unreserved” (U.S. Public Law85–508 1958). Although aboriginal title to these lands wasnever extinguished, the state treated the traditional territoriesof Alaska Natives as part of the public domain. Consequently,the state’s attempt to regulate subsistence began in 1958.Alaska Natives actively resisted these regulations by pushing

Table 1 Examples of observed environmental changes and their impacts on subsistence harvesting in Ruby Village, AK

Impacts Definition Observations

Predictability Climate impacts that reduce the ability to predict weather including,rain, snowfall and temperature, to the detriment of a harvester’sability to plan and carry out subsistence livelihood activities.

The weather these days is strange and it is harder to predict.Increased variability of rain and snowfall.Reduced ability to predict when river ice will freeze or break up.Reduced predictability of streamflow on the Yukon River.

Access Climate impacts reducing or preventing access to a particular areafor subsistence harvesting. Access can be influenced by changesin ice, snow, or open water crucial for transportation.

Sandbars forming at the mouths of sloughs reduce access by boat.Reduced water levels in sloughs during the fall prevent entry byboat and therefore access to key hunting grounds.

Changing freeze-up and break-up dates for river ice can temporarilyalter time periods in which people have access to certain areas.

Changes in streamflow and sediments may be altering context-specific conditions required to fish, e.g.,. changes in eddiesimportant for fishing salmon.

Safety Climate impacts reducing the safety of subsistence harvesters,largely in the course of travel on the Yukon River and itstributaries. Safety is closely linked to predictability.

Increased number of open leads, or unfrozen spots, on the rivermake travel over frozen rivers and sloughs dangerous.

Water levels have been higher than normal on the Yukon Riverduring the summer, making travel and fishing on the river moredangerous at times.

Increased spoilage of meat due to higher fall temperatures.

SpeciesAvailabili-ty

Climate impacts reducing the availability of subsistence specieseither through the introduction of new species to the area orreduction in the temporal or spatial availability of other speciesthrough altered migration or other factors.

Observed delay in moose rut, likely caused by increasedtemperature.

New birds have been observed.Observed changes in salmon populations could be influenced byclimate since streamflow and temperature may affect salmonpopulations, as they are controlling factors in their life cycles(Bryant 2009).

92 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

for the recognition of native subsistence rights (Berger and theAlaska Native Review Commission 1985).

In 1971, a growing global interest in developing naturalresource extraction, such as the oil discovered at Prudhoe Bayin 1968, motivated the passing of the Alaska Native ClaimsSettlement Act (ANCSA) to extinguish native rights to theland and its resources. ANCSA resulted in the creation of 13regional corporations and the allocation of 44 million acres(10 % of the total land) and $962.5 million in compensationfor relinquished lands (about $3 per acre). At the same time,

197 million acres of land were reserved for the federal gov-ernment (60 % of the total land), and the State of Alaska wasgranted the remaining 124 million acres (30 % of the state)(Berger and the Alaska Native Review Commission 1985).

ANSCA also included a vague promise that native subsis-tence rights would be protected. This protection was not real-ized until 1980 with the passage of the Alaska National InterestLands Conservation Act (ANILCA). ANILCA applies exclu-sively to federal lands. Title VIII of ANILCA creates a ruralsubsistence priority. Subsistence rights to wild resources are

Fig. 2 Combined seasonal round depicts the timing of present subsistence practices of all community experts.Grey areas, circled in red, indicate moosehunting seasons that are no longer permitted

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 93

promoted over all other uses, including recreational and com-mercial uses, in times of shortage. Only conservation takespriority over rural subsistence (U.S. Public Law 96–4871980). The subsistence rights guaranteed by ANILCAare not exclusive to Alaska Natives, because they aregranted on the basis of rural residency. However, ANILCAacknowledges the importance of subsistence rights for nativecultural existence, allowing for hunting for “customary andtraditional uses,” such as hunting a moose for a communitypotlatch (Berger and the Alaska Native Review Commission1985; U.S. Congress 1980). In contrast, the State of Alaskaguarantees subsistence priority for all Alaska residents(Alaska 1956). Many native peoples take issue with subsis-tence rights in Alaska, as defined by the state and federalgovernments, because competition for scarce resourcesposes a threat — not only to their food security butalso to their way of life (Thornton 2001; Wheeler and

Thornton 2005). Consequently, subsistence rights continueto be one of the most hotly debated issues in Alaska(Wheeler and Thornton 2005).

Subsistence is regulated by both state and federal agencies.Changes in subsistence regulations are determined by both theFederal Subsistence Board and State Board of Game (BOG)and implemented by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service andthe Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) respec-tively (Carey 2009). The Alaska Department of Fish andGame manages the hunt on all state and private lands includ-ing native allotments and lands held by native corporations.U.S. Fish and Wildlife regulates hunting on all federal landsincluding Nowitna National Wildlife Refuge (the “Novi”),part of the traditional territory of the people of Ruby. Thepeople of Ruby hunt in the middle Yukon region, whichconsists of a patchwork of native corporation–selected land,native allotments, and state and federal lands (Unit 21).

Fig. 3 Land use map for the people RubyVillage illustrates the spatial distribution of present subsistence practices throughout the majority of the peopleof Ruby’s traditional territory

94 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

Subsistence Livelihoods, Vulnerability, and Adaptationto Climate Change

Research findings indicate that social vulnerabilities created byhaving to adapt subsistence livelihoods to past social changehave bearing on the current ability to respond to climate impacts(Table 2). The potential for social vulnerabilities to constrainadaptation to ecological change is illustrated by several exam-ples. First, adaptation to the impacts of climate change will beinfluenced by a dependency on cash resources and fossil fuels.The development of a mixed economy and the use of newtechnologies represent adaptive responses to the social changes.While these adaptations allowed the people of Ruby to maintainsubsistence livelihoods in spite of dramatic social change, theresulting dependency on cash resources and fossil fuels makesthem susceptible to fluctuations in the market economy. Theabove case study indicates that dependency on cash and fossilfuels has important implications for subsistence livelihoods.Climate change adds complexity to this scenario. Because theirability to respond to ecological changes is limited by the avail-ability of resources, these dependencies will influence the peopleof Ruby’s ability to respond to climatic changes requiring thatthey hunt for longer or travel further away to meet their subsis-tence needs. For example, reduced fall water levels in sloughscan be a barrier to accessing important hunting grounds. Theinability to access certain sloughs by boat can mean that huntersmust travel further to hunt for moose, therefore using more gas.

Second, adaptation to climate change is constrained by thepeople of Ruby’s loss of flexibility and control over subsistenceharvesting due to the creation and enforcement of fish andwildlife regulations. The imposition of regulations removed localcontrol over decision making about subsistence harvesting in-cluding choice regarding the timing,4 intensity, and locations ofthe harvest. Climate change is impacting subsistence species andtheir habitat. For example, the people of Ruby are alreadyobserving and responding to the impacts of climate change onmoose hunting.5 Increasing temperatures are believed to be a

factor in an observed a shift in the timing of the moose rut to laterin the fall. George Albert noted that

Except for this year [2010], it has been too warm.It has been hard for the moose because they don’tstart moving around until really late. One oddthing I noticed about moose is that last year, theygot a bull moose on the 16th of September and he waswith two cows but wasn’t in rut either. He didn’t smellor anything. Somebody else got a moose that late alsoand it was not in rut.

Several other community experts made similar obser-vations regarding a delay in the rutting season, whichthey believed to be triggered by increasing temperatures.Fall breeding dates are determined by photoperiod(length of daylight) (Schwartz 1998) and temperature,when cool temperatures cause bulls start to movearound in search of cows (Bubenik 1997). The exacttemperature that triggers bull movements is not known;however, other Koyukon hunters in the interior ofAlaska have similarly observed that increasing tempera-ture is contributing to a delayed bull movement (McNeeleyand Shulski 2011).

The ability of the people of Ruby and other Alaska Nativehunters to shift the timing of their harvest in response to thedelayed rut is limited by state and federal subsistence huntingregulations.6 Regulations are implemented in response toperceived declines in moose populations. Threats to moosepopulations identified by conservation biologists (Stout 2008)and the people of Ruby include predation by wolves, weather,and overhunting, largely by nonlocal hunters. The objec-tive of these regulations is twofold: to maintain andenhance moose populations and their habitat, and toprovide sustained opportunities for moose hunting forsubsistence and sport hunters (Stout 2008). As describedabove, federal regulations give subsistence priority torural residents while state regulations grant these rightsto all Alaska residents.

4 Interview narratives indicate that while the people of Ruby were previ-ously able to hunt moose at any time of year, they would primarily huntmoose during the fall (August and September), as they do now, and in thespring (February and March). Cow moose were primarily hunted duringthis time because they are typically in better shape than bull moose, withmore fat after the winter. Moose would also be hunted after breakup ifthere were no other food sources available.5 Moose hunting is one of the most significant subsistence livelihoodactivities for the people of Ruby. In a 2004 study, it was found thatapproximately 88% of the people of Ruby use moose meat. At that time,64% of households participated in hunting and 40% had successfullyhunted a moose. Of those who had hunted a moose, 60% reported sharingmoose meat (Brown, Walker, and Vanek 2004). Moose hunting is notonly important as a means of meeting the nutritional needs of the peopleof Ruby, it is also a culturally important activity and considered part of away of life.

6 The open season for moose hunting occurs during the fall. Inthe area around Ruby, ADF&G regulates an open season fromAugust 22 to 31 and September 5 to 25 (on state and privatelands, including lands held by native corporations) and U.S. Fishand Wildlife regulates a hunt from September 26 to October 1 (onfederal lands) (AFWS 2010). Moose hunting is no longer permit-ted at any other time of year, with the exception of taking amoose for community potlatches or other traditional purposes.The harvest is limited to one moose per person. People are onlyallowed to hunt bulls with antlers. Hunting cow moose in the areanear Ruby is prohibited. Hunting regulations, seasons, bag limits,and means of hunting are determined by both the state andfederal boards of game and implemented by their respectiveagencies (Carey 2009).

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 95

The observed shift in timing of the moose rut hasprompted negotiations over the timing of the regulatedfall subsistence hunt. The people of Ruby and otherAlaska Native villages in the Koyukon region ofAlaska have negotiated with both state and federalagencies in an attempt to lengthen the regulated timeframe for subsistence hunting or shift it to later in thefall season (McNeeley 2011). In 2008 and 2009, Rubyexperienced especially poor moose seasons. Accordingto Tribal Fish and Wildlife staff, the Ruby TribalCouncil bargained with state and federal agencies tochange the hunting season in response to the need toharvest more moose. The impacts of temperature on thetiming of rut were considered during the process. WhileU.S. Fish and Wildlife was responsive to the possibilitythat climate change may be a factor affecting mooseharvest for the people of Ruby, the ADF&G took theposition that climate does not affect the timing of the rut andhunting should not take place during the peak breedingdates, which, they assert, occur between September 25and October 5 (Van Ballenberghe and Miquelle 1993).Notably, this position is based on studies of the mediancopulation dates of moose conducted between 1982 and1987, making the data nearly three decades old (VanBallenberghe and Miquelle 1993). Consequently, U.S. Fishand Wildlife extended the season on the Nowitna WildlifeReserve by 1 week, September 25 to October 1. The ADF&Gextended the hunt by an additional 5 days at the end ofAugust.

The case of moose hunting shows that the people ofRuby have some influence over the decisions regardingsubsistence harvesting through direct negotiation withthese agencies; it also demonstrates the potential for fish

and wildlife regulations to increase vulnerability byconstraining the ability of those directly affected to re-spond to the impacts of climatic change on subsistencespecies and their habitat. Shannon McNeeley states,“Alaskan communities are impacted by a regulatorydecision-making process that, to date, can’t effectivelyrespond to slow-onset climate change that impacts moosebehavior and moose harvest success thereby threateningfood security and community well-being” (McNeeley2011:2). While the objective of fish and wildlife regula-tions to conserve fish and wildlife populations is not indispute, the role of indigenous communities, such as RubyVillage, in the decision-making process is problematic.This case study indicates that current institutional arrange-ments have the capacity to increase vulnerability to eco-logical change by reducing local control over harvestingdecisions.

Implications for Climate Change Adaptation

Climate change adaptation is a pertinent issue for thepeople of Ruby and their subsistence livelihoods. Thepeople of Ruby have experienced incredible socialchanges during the course of the last six decades in-cluding sedentarization, increased contact with the mar-ket economy, and the creation and enforcement of sub-sistence harvesting regulations. These changes havelargely been a consequence of European contact andcolonization. Analysis of adaptation to historical changeexperienced since the 1950s can provide insight into theways that social and political contexts shape vulnerabil-ity to climate impacts. For example, dependency oncash and fossil fuels and imposition of fish and wildlife

Table 2 Summary of adaptations to past social change and present vulnerabilities

Social change Adaptation/copingmechanism

Impact Presentvulnerability

Climate impact

Sedentization or settlementin a central village location.

Use of snowmobiles tomaintain seasonal rounds.

Dependence on gas andmarket economy.

Vulnerability tofluctuations inmarket economy.

Reduced access andpredictability in subsistencelivelihoods can mean thatpeople need to travel longerperiods of time or distancesto obtain their harvest. Theircapacity to do so is limitedby access to cash and otherresources.

Increased presence ofthe market economy.

Development of a“mixed economy.”

Dependence on marketeconomy.

Creation and enforcementof subsistence harvestingregulations.

Changes in timing, intensity,and location of harvesting.

Reduced flexibility of(control over) subsistenceharvesting (intensity,timing, and location).

Restricted ability toadapt subsistenceharvesting toecological change.

Reduced predictability andaccess highlight challengesassociated with the loss offlexibility or control oversubsistence.

96 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

regulations, resulting from past social changes, can increasevulnerability by constraining people’s ability to respond toecological change.

It was been noted that diversity is essential for adaptationwithin socio-ecological systems (Kassam 2010, 2009, 2008;Pretty et al. 2008; Valdivia et al. 2010). While this paperfocused on the role of broader political factors on acommunity’s ability to adapt to climate change, it must beacknowledged that Ruby Village and other communities areheterogeneous and characterized by variation in knowledgeand practices related to subsistence harvesting, political per-spectives, and other factors that result in the use of diverseadaptation strategies. Understanding the role of diversitywithincommunities in adaptation to change is a promising area thatmerits further investigation.

As issues of justice in climate change adaptation are in-creasingly brought to the forefront, acknowledging the influ-ence of the political context for adaptation becomes a neces-sity. Human communities differ in their ability to respond tothe impacts of climate change (Adger 2006), and adaptation tothe biophysical impacts of climate change has the capacity toaggravate and reproduce existing vulnerabilities (Adger et al.2006; Mearns and Norton 2010). Climate justice for indige-nous peoples has at least three dimensions. First, indigenouspeoples have contributed the least to the causes of climatechange (Crate and Nuttall 2009). Second, they are among thefirst to be impacted due to their close connections to their localecology through subsistence livelihoods (Kassam 2009).Third, as this study illustrates, the legacy of colonialismpresents political barriers that can make indigenous commu-nities more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

The impact of fish and wildlife regulations on the people ofRuby’s ability to respond to ecological change is an example ofa political barrier to adaptation. Although the regulation ofsubsistence livelihoods for Alaska Natives and the impacts ofnative self-determination has been hotly contested since AlaskaStatehood, through ANCSA and ANILCA (Berger and theAlaska Native Review Commission 1985), climatic impactson subsistence add further relevance to existing criticisms.Further research should be done to examine alternative institu-tional arrangements that might address the current lack offlexibility and local control in harvesting regulations andalso ensure the conservation of subsistence species forpresent and future generations. Koyukon Athabascanconservation practices (Nelson 1986) would be an ef-fective starting place for developing alternative institu-tional arrangements. Given the long-term struggle of AlaskaNatives to gain control over subsistence harvesting,convincing both state and federal agencies to alter thecurrent power-sharing arrangements is likely to be asignificant hurdle to increasing local control over subsistence

livelihoods through the implementation of co-managementagreements or otherwise. This reality adds to the urgency forfuture research on this topic.

Conclusion

Climate change adaptation is an important issue for indige-nous peoples and their subsistence livelihoods, which areclosely connected to the local ecology. The people of Rubyhave faced tremendous changes in the last half century.Interview narratives illustrate many of these changes insubsistence livelihoods. The people of Ruby’s responsesto historical changes, including sedentarization, in-creased contact with the market economy, and the cre-ation and enforcement of subsistence harvesting regula-tions, demonstrate their resilience and determination tomaintain subsistence livelihoods. Research findings alsoindicate adaptations to these past social changes havebearing on the people of Ruby’s present vulnerability toclimate impacts. Furthermore, this analysis raises manyethical considerations regarding the constraints presentedby the current political context, shaped by a colonialhistory, to indigenous peoples’ ability to respond to theimpacts of climate change in the manner of their choos-ing. As such, adaptation to climate change is not solelyabout responding to the directly observable impacts ofclimate change on subsistence livelihoods, it is also aboutunderstanding and addressing the manner in which thebroader political context can make communities more or lessvulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Acknowledgments This paper is based on research conducted in com-pletion of my MS thesis at Cornell University. It would not have beenpossible without support from my research partners, the Yukon RiverInter-Tribal Watershed Council and the Ruby Tribal Council. I am alsodeeply grateful to the community experts from Ruby Village who sharedtheir knowledge including George Albert, Phillip Albert, Tom Esmailka,Billy Honea, Clara Honea, Lorraine Honea, Junior and Karen Gurtler,Nora Kangas, Billy McCarty, Emmitt and Edna Peters, Joe Peters, Markand Tudi Ryder, Ed Sarten, Lily Sweetsir, Pat Sweetsir, Allen Titus andMarthaWright. Enaa baasee’ (Thank you). I would also like to thankmyadviser, Karim-Aly Kassam, and my minor committee members, PaulNadasdy and Todd Walter. I am also grateful to Morgan Ruelle, RyanToohey, and Carol Hasburgh for reviewing a previous draft of this paperand to Morgan Ruelle for the inspiration to incorporate seasonal roundsinto my research methods. This study was made possible by variousfunding sources including the Cornell Department of Natural Resourcesand American Indian Program, the Arctic Institute of North America,Grants In-Aid (2010), the Department of Foreign Affairs and Internation-al Trade, Canada Circumpolar World Fellowship (2010), the CornellGraduate School Research Travel Grant (2010, 2011), the Mario EinaudiCenter for International Studies Travel Grant (2010, 2011) and theWoodrow Wilson Fellowship Foundation’s Doris Duke ConservationFellowship (2011–2012).

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 97

Appendix7,8

Table 3 Description of fourteen subsistence activities in Ruby Village, AK

Livelihood activity Description Species names (Common, Scientific & Koyukon)

Moose hunting Moose hunting is one of the most important subsistenceactivities for the people of Ruby. It is culturally important,and moose meat comprises a large proportion of theirdiet (Brown et al. 2004).

Moose (Alces alces): Deneega

Fishing Fishing is one of the most important subsistence activities.Salmon provide one of the most important subsistencesources of food. Salmon fishing occurs between the endof June and the end of September and many people stillmaintain a fish camp. Other fish are caught throughoutthe year. However, the spring camp where much of thisfish was at one time caught is no longer practiced.

Alaska blackfish (Dallia pectoralis): oonyeeyhBurbot, loche, ling cod (Lota lota): tl’eghesDolly Varden trout (Salvelinus malma , uncertainidentification): ggaal yeega’, silyee lookk’a

Grayling (Thymallus arcticus): tleghelbaayeLongnose sucker (Catostomus catostomus):bedleneege toonts’oode

Northern Pike (Esox lucius): K’oolkkoyeSalmon (any kind): lookk’eChinook or King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha):ggaal

Summer-run Dog or Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus ketaII):noolaaghe

Fall-run Dog or Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus ketaII):noldlaaghe

Silver or Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch): leghaaneSheefish, inconnu (Stendous leucichthys nelma): ledlaagheWhitefish (any kind): look’e

Bear hunting Bears are hunted for their skins and meat. Bear huntingis traditionally only done by men and takes place atvarious times of the year. Bears are considered HutlaneeAnimals (taboo), which have very strong spirits.

American Black Bear (Ursus americanus): sesGrizzly or Brown Bear (Ursus arctos): tlaaghoze

Fur animal huntingand trapping

Trapping usually starts in November when the snow fallsand ends in March or April at the end of the beaverseason. Marten, mink, fox, lynx, wolf, wolverine,beaver, and muskrat are all trapped for their furs andin some cases for meat. Furs are either used locallyor sold to fur traders. Although currently fewerindividuals actively participate in trapping, itcontinues to be an important activity.

Marten (Martes Americana): soogeAmerican Mink (Neovison vison): taahgoodzeLiterally: “under water”

Red Fox (Vulpes fulva): naaggedleLynx (Lynx canadensis): kaazene Literally: “black tail”Wolverine (Gulo luscus): neltseel , doyonhWolf (Canis lupus): nek’eghun, tookkoneMuskrat (Ondatra zibethicus): bekenaaleBeaver (Castor canadensis): noye’e, ggaagge

Snowshoe hare huntingand trapping

Rabbit snaring begins in late November or earlyDecember when the snow has fallen and the rabbitshave changed color. There is no closed season andno harvest limit. Rabbits are snared for their meatand fur. Their fur is used to make mittens andother articles of clothing.

Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus):White in winter: gguhBrown summer coat: saanh zooge

Waterfowl hunting People hunt waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swanswhen they return in March until break up occurs onthe Yukon River. They are hunted again after breakup when people go out on the river in their boats.People make sure to stop hunting them in June whenthey are breeding. Specific trips to hunt these birdsare not made often. They are hunted in the courseof other subsistence activities such as moose hunting.

Common Loon (Gavia immer): dodzeneGoose (general term): dets’eneCanada Goose (Branta Canadensis): belaalzeneSnow Goose (Chen hyperboreus): hugguhDuck (general term): nendaaleSandhill Crane (Grus Canadensis): deldooleSwan (Cygnus sp.): toyene

98 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

7 Livelihood activities were borrowed from Nelson 1986 and adapted tothe context of Ruby Village.8 All Koyukon names sourced from The Koyukon AthabascanDictionary authored by Eliza Jones and Jules Jetté (2000).

References

(2005). Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversity Press.

(2009). Biocultural diversity and indigenous ways of knowing: Humanecology in the Arctic. Calgary: University of Calgary Press/ArcticInstitute of North America.

(2009). Canadian Inuit subsistence and ecological instability—if theclimate changes, must the Inuit? Polar Research 28(1): 89–99.

(2010). Coupled socio-cultural and ecological systems at the margins: arcticand alpine cases. Frontiers of earth science in China 4(1): 89–98.

ACIA (Arctic Climate Impact Assessment) (2004). Impacts of a warmingArctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge, UK.

Adger, W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16(3):268–281.

Adger, W. N., and Mick Kelly, P. (1999). Social vulnerability to climatechange and the architecture of entitlements. Mitigation andAdaptation Strategies for Global Change 4(3): 253–266.

Table 3 (continued)

Livelihood activity Description Species names (Common, Scientific & Koyukon)

Spruce grouse hunting Spruce grouse or spruce hens can be hunted startingas early as mid-August up until mid-April. However,most people hunt them from September until it snowsin November, because after a certain time their meatbegins to taste like spruce.

Spruce Grouse (Canachites canadensis): deyh

Willow or ruffed grousehunting

Willow grouse (Ruffed grouse) can be hunted fromAugust until about mid-April. Most people huntthem in the fall between September and November,when the snow falls. Some people begin huntingthem again in January and February. Some peoplesaid that they have the same season as Spruce grouse,while others stated that they hunt Willow Grouselater into the season.

Willow Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) : tsonggude

Ptarmigan hunting Ptarmigan live in the tundra of the high Arctic in thesummer months and migrate south to the forestfor the winter months. It is possible to hunt thesefrom late November or early December untilthe end of February.

Willow Ptarmigan (Lagopus lagopus): daaggooRock Ptarmigan (Lagopus muta): daak’aa

Berry picking The people of Ruby pick many kinds of berries duringthe summer and fall months. Berries are eaten fresh,made into fish ice cream, made into baked goods,or preserved as jam.

Bog cranberry (Oxycoccuss microcarpus): daal nodoodle’Highbush cranberry (Viburnum edule): donaaldloyeLowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis): denaalekk’ezeCrowberry, blackberry (Empetrum nigrum): deenaalt’aasRed Currant (Ribes triste): notsehtl’ooneBlack Currant (Ribes hudsonianum): dotson’ geege’Raspberries (Rubus idaeus): dets’en tl’aakkRosebuds (Rosa acicularis): kooykSalmonberry, cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus): kkotlWild rhubarb (Polygonum alaskanum): ggool

Wood cutting Wood is cut or collected for various uses includingfirewood and to build traditional snowshoes and sleds.

American Green Alder (Alnus crispa): kk’esBalsam poplar (often mistakenly called cottonwood poplar)(Populus balsamifera): t’eghel

White spruce (Picea glauca): ts’ebaaBlack spruce (Picea mariana): ts’ebaa t’aalPaper Birch (Betula papyrifera): kk’eeykQuaking aspen (Populus trichocarpa): t’eghel kk’oogeWillow (general term): kk’uyk

Gardening Gardens have been cultivated in Ruby since the earlytwentieth century. At the time this research wasconducted, 11 out of 62 households had a smallgarden. There is also a community garden that beingused primarily to teach children about gardening.

A variety of vegetables are cultivated including potatoes,turnips, carrots, strawberries, tomatoes, rutabaga,cabbage, and lettuce.

Wage labour The economy of Ruby can be characterized as a“mixed” economy, where cash is an important inputinto subsistence livelihoods (Wenzel et al. 2000).

A variety of seasonal and year-round jobs are heldin industries including carpentry, construction,and firefighting.

Caribou hunting There are caribou from the Western Arctic Herd inthe Kilbuck-Kuskokwim Mountains near Ruby.The people of Ruby used to hunt caribou, but thisis not practiced anymore.

Caribou (Rangifer tarandus granti): bedzeeyh

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 99

Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., and Tompkins, E. L. (2005). Successfuladaptation to climate change across scales. Global EnvironmentalChange Part A 15(2): 77–86.

Adger, W. N., Paavola, J., Huq, S., and Mace, M. J. (eds.) (2006). Fairnessin adaptation to climate change. MIT Press, Cambridge Mass.

Agrawal, A., and Perrin, N. (2009). Climate Adaptation, Local Institutionsand Rural Livelihoods. # W08I-6. IFRI Working Paper. University ofMichigan: International Forestry and Resources Institution.

Alaska, F. (1956). The Constitution of the State of Alaska. AlaskaConstitutional Convention, Fairbanks.

Alaska Fish and Wildlife Service. (2010). Unit 21/Hunting - MiddleYukon. Federal Subsistence Wildlife Regulations. http://alaska.fws.gov/asm/pdf/wildregs/unit21.pdf, accessed January 23, 2012.

Berger, T., and the Alaska Native Review Commission (1985). Villagejourney: The report of the Alaska native review commission, 1st ed.Hill and Wang, New York.

Berkes, F., and Jolly, D. (2001). Adapting to climate change: social-ecological resilience in a Canadian western arctic community.Conservation Ecology 5(2): 18.

Berkes, F., Colding, J., and Folke, C. (2003). Navigating social-ecological systems: Building resilience for complexity and change.Cambridge University Press, New York.

Brown, C. L.,Walker, R. J. andVanek, S. B. (2004). The 2002–2003 harvestof moose, caribou, and bear in Middle Yukon and Koyukuk RiverCommunities. Division of Subsistence, Alaska Dept. of Fish andGame. http://www.subsistence.adfg.state.ak.us/TechPap/tp280.pdf.

Bryant, M. (2009) Global Climate Change and Potential Effects onPacific Salmonids in Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska.Climatic Change 95(1): 169–193.

Bubenik, A. B. (1997). Behavior. In Ecology andmanagement of the NorthAmerican Moose. Washington (D.C.): Smithsonian Institution Press.

Burton, I., Kates, R. W., and White, G. F. (1993). The environment ashazard. Guilford Publications.

Cameron, E. S. (2011). Securing indigenous politics: a critique of thevulnerability and adaptation approach to the human dimensions ofclimate change in the CanadianArctic. Global Environmental. Change.

Carey, E. (2009). Building resilience to climate change in Rural Alaska:Understanding impacts, adaptation and the role of TEK. Universityof Michigan.

Carpenter, S., Brian Walker, J., Anderies, M., and Abel, N. (2001). Frommetaphor to measurement: resilience of what to what? Ecosystems4(8): 765–781.

Chapin III, F., Stuart, G. P., Berkes, F., et al. (2004). Resilience andvulnerability of northern regions to social and environmental change.AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 33(6): 344–349.

Congress, U. S. (1980). Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act(ANILCA). Public Law 96: 487.

Crate, S. A., and Nuttall, M. (2009). Anthropology and climate change:From encounters to actions. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Dombrowski, K. (2001). Against culture: development, politics, andreligion in Indian Alaska. University of Nebraska Press.

Eakin, H., and Luers, A. L. (2006). Assessing the vulnerability of social-environmental systems. Annual Review of Environment andResources 31: 365–394.

Erickson, P. A., and Murphy, L. D. (1998). A history of anthropologicaltheory. Illustrated edition. UTP Higher Education.

Ford, J. D., and Pearce, T. (2010). What we know, do not know, and needto know about climate change vulnerability in the western Canadianarctic: a systematic literature review. Environmental ResearchLetters 5(1): 014008.

Ford, J. D., and Smit, B. (2004). A framework for assessing the vulner-ability of Communities in the Canadian arctic to risks associatedwith climate change. Arctic: 389–400.

Ford, J. D., Smit, B., and Wandel, J. (2006). Vulnerability to climatechange in the arctic: a case study from arctic Bay, Canada. GlobalEnvironmental Change 16(2): 145–160.

Ford, J. D., Pearce, T., Smit, B., et al. (2007). Reducing vulnerability toclimate change in the arctic: the case of Nunavut, Canada. Arctic60(2): 150–166.

Greenwood, D. J., and Levin, M. (2008). Introduction to action research:Social research for social change, 2nd ed. Sage, Thousand Oaks,California.

Hansen, J., Sato, M., Ruedy, R., et al. (2006). Global temperature change.PNAS 103: 39.

Herman-Mercer, N., Schuster, P. F., and Maracle, K. B. (2011).Indigenous observations of climate change in the Lower YukonRiver Basin, Alaska. Human Organization 70(3): 244–252.

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems.Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4(1): 1–23.

IPCC (International Protocol on Climate Change) (2007). Climate change2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working group IIContribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC (ClimateChange 2007). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK.

Jetté, J., and Jones, E. (2000). Koyukon athabaskan dictionary.Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks,Fairbanks, AK.

Kassam, K-A. S. (2009) Biocultural Diversity and Indigenous Ways ofKnowing: Human Ecology in the Arctic. Calgary: University ofCalgary Press/Arctic Institute of North America.

Kassam, K-A. S. (2010) Coupled Socio-cultural and Ecological Systemsat the Margins: Arctic and Alpine Cases. Frontiers of Earth Sciencein China 4(1): 89–98.

Kassam, K.-A. S. (2008). Diversity as if nature and culture matter: bio-culturaldiversity and indigenous peoples. The International Journal ofDiversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations 8(2): 87–95.

Kassam, K-A. S., and the Soaring Eagle Friendship Centre. (2001). “Sothat our voices are heard”: Forest use and changing gender roles ofdene women in Hay River, Northwest Territories. CIDA-ShastriPartnership Project.

Kassam, K-A. S., and the Wainwright Traditional Council. (2001).Passing on the Knowledge: Mapping Human Ecology inWainwright, Alaska. Arctic Institute of North America.

Kassam, K-A. S., Baumflek, M., Ruelle, M., and Wilson, N. (2011).Human ecology of vulnerability, resilience, and adaptation: Casestudies of climate change from high latitudes and altitudes. InClimate change – socioeconomic effects. Juan Blanco andHoushang Kheradmand, eds. Pp. 217–236. Intech. http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/human-ecology-of-vulnerability-resilience-and-adaptation-case-studies-of-climate-change-from-high-la, accessed April 30, 2011.

Kawagley, A. O. (1999). Alaska native education: history and adaptation inthe new millennium. Journal of American Indian Education 39(1):31–51.

Krupnik, I. I., and Jolly, D. (2002). The earth is faster now: Indigenousobservations of Arctic Environmental Change. Arctic ResearchConsortium of the United States.

Larson, W. (2006). Ruby Alaska a Gold Rush Town on the Yukon River.http://rubyalaska.info/, accessed July 27, 2010.

McNeeley, S. M. (2011). Examining barriers and opportunities for sus-tainable adaptation to climate change in interior Alaska. ClimaticChange: 1–23.

McNeeley, S. M., and Shulski, M. D. (2011). Anatomy of a closingwindow: Vulnerability to changing seasonality in Interior Alaska.Global Environmental Change.

Mearns, R., and Norton, A. (eds.) (2010). Social dimensions of climatechange: Equity and vulnerability in a warming world. World Bank,Washington, DC.

Nelson, R. K. (1986). Make prayers to the Raven: A Koyukon view of theNorthern Forest. University of Chicago Press.

Nichols, T., Berkes, F., Jolly, D., and Snow, N. B. (2004). Climate changeand Sea Ice: local observations from the Canadian Western Arctic.Arctic: 68–79.

100 Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101

Nuttall, M., Berkes, F., Forbes, B., et al. (2005). Hunting, herding, fishingand gathering: Indigenous peoples and renewable resource use in thearctic. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Cambridge UniversityPress, Cambridge, pp. 649–690.

Patton, M. Q. (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3rdedition. Sage Publications, Inc.

Pretty, J., Adams, B., Berkes, F. et al. (2008). How do biodiversity andculture intersect. In Plenary Paper Presented at the Conference forSustaining Cultural and Biological Diversity in a Rapidly ChangingWorld: Lessons for Global Policy Pp. 2–5.

Reid, H., Alam, M., Berger, R., et al. (2009). Community-based adapta-tion to climate change: an overview. Participatory Learning andAction 60(1): 11–33.

Reidlinger, D., and Berkes, F. (2001). Contributions of traditional knowl-edge to understanding climate change in the Canadian Arctic. PolarRecord (203): 315–328.

Ribot, J. C. (1995). The causal structure of vulnerability: its application toclimate impact analysis. GeoJournal 35(2): 119–122.

Salinger, M. J. (2005). Climate variability and change: past, present andfuture – an overview. Climatic Change 70(1–2): 9–29.

Schwartz, C. C. (1998). Reproduction, Natality and growth. In Ecologyand management of the North American Moose. Pp. 141–171.Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Smit, B., and Wandel, J. (2006). Adaptation, adaptive capacity andvulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16(3): 282–292.

Smit, B., Burton, I., Klein, R. J. T., and Wandel J. (2000) An anatomy ofadaptation to climate change and variability. Climate Change45(223–251).

Stout, G. W. (2008). Unit 21B moose. Wildlife moose managementreport, project 1.0. Moose Management Report of Survey andInventory Activities 1 July 2005–30 June 2007. AlaskaDepartment of Fish and Game, Alaska, USA.

Tester, F. J., and Kulchyski, P. K. (1994). Tammarniit (mistakes): InuitRelocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939–63. UBC Press.

Thornton, T. F. (2001). Subsistence in northern communities: lessonsfrom Alaska. The Northern Review 23: 82–102.

Turner, B. L., Matson, P. A., McCarthy, J. J., et al. (2003). Illustratingthe coupled human–environment system for vulnerability

analysis: three case studies. Proceedings of the NationalAcademy of Sciences of the United States of America 100(14):8080–8085.

U.S. Census (United States Census). (2010). Ruby City, Profile ofGeneral Population and Household Characteristics. Summary File(Public Law (P.L.) 94–171). http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DP_DPDP1&prodType=table, accessed September 21, 2011.

U.S. Public Law 85–508. (1958). Alaska Statehood Act. http://www.lbblawyers.com/statetoc.htm, accessed July 1, 2011.

U.S. Public Law 96–487. (1980). ANILCA (Alaska National InterestLands Conservation Act).

Valdivia, C., Seth, A., Gilles, J. L., et al. (2010). Adapting to climatechange in Andean ecosystems: landscapes, capitals, and perceptionsshaping rural livelihood strategies and linking knowledge systems.Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100(4): 818.

Van Ballenberghe, V., and Miquelle, D. G. (1993). Mating in moose:timing, behavior, and male access patterns. Canadian Journal ofZoology 71(8): 1687–1690.

VanStone, J. W. (1974). Athapaskan adaptations: Hunters and fishermenof the subarctic forests. Aldine Publishing Co.

Wenzel, G. W. (2009) Canadian Inuit Subsistence and EcologicalInstability—if the Climate Changes, Must the Inuit? PolarResearch 28(1): 89–99.

Wenzel, G. W. (1991). Animal rights, human rights: Ecology, econo-my and ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of TorontoPress.

Wenzel, G. W., Hoevelsrud-Broda, G., Kishigami, N., andHakubutsukan, K. M. (2000). The social economy of sharing:Resource allocation and modern hunter-gatherers. NationalMuseum of Ethnology, Osaka.

Wheeler, P., and Thornton, T. F. (2005). Subsistence research in Alaska: athirty year retrospective. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 3(1): 69–103.

White, G. F. (1973). Natural hazards research. Directions in Geography:193.

Wolfe, R. J. (2000). Subsistence in Alaska: a year 2000 Update. Divisionof Subsistence, Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Hum Ecol (2014) 42:87–101 101