The origin of haplogroup I1-M253 in Eastern Europe Alexander Shtrunov

-

Upload

aleksandr-shtrunov -

Category

Documents

-

view

2.324 -

download

1

description

Transcript of The origin of haplogroup I1-M253 in Eastern Europe Alexander Shtrunov

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

1

The origin of haplogroup I1-M253

in Eastern Europe

Alexander Shtrunov

Abstract

One of the actual issues of modern genetic genealogy is the origin of a haplogroup. It is not easy to connect data on genetics,

archeology, linguistics, anthropology and other related sciences. In this paper the author tries to find the root of haplogroup I1-M253 in Eastern Europe.

Haplogroup I1* together with it’s relative sub-clades I2a* and I2b* is the native European hap-logroup because its frequencies outside Europe are extremely small. This spreading of carriers of

this haplogroup gave basis to consider carriers of I1 as the descendants of Paleo-European popula-tion. The area of haplogroup I1-M253 is concen-trated mainly in the north of Europe, in the Scan-dinavian countries. There are also local of I1 in England (15,4%) [1], Sicily (up to 18,75%) [2] and in the centre of European Russia (up to 17%) [3]. The presence of carriers of haplogroup I1-M253 at British Isles is associated with the ex-pansion of the Vikings and the Normans, which was proved by historical and genealogical stu-dies, though the ancient migrations are also possible. In Sicily, haplogroup I1-M253 strongly correlates with Norman invasions from the terri-

tory of modern France (Normandy, I1 – 11,9%) and the foundation of the Kingdom of Sicily (Sici-lian Kingdom) in 1130. However, the presence of haplogroup I1-M253 with high frequencies in the center of the European part of Russia brings up a lot of questions. E.V. Balanovskaya and O.P. Ba-lanovsky state the following about it in their book «The Russian gene pool of the Russian Plain» [4]:

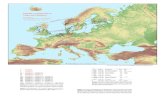

«Spreading of «Nordic» haplogroup I1a in Russian area is considered quite unexpected (Fig. 1). The high values of I1a would be predicted close to Scandinavia in the northwest of Russian

area. There, as well as at the western boundary «Varangian» influence can be expected in the form of high frequencies of I1a. However, com-pact maximum of I1a (11-12%) is located in an entirely different area at the north-east. This lo-cal centre stands out against the background of low frequencies (less than 6%), which are typical of the rest of the Russian area. The presence of this center is based on data of three Russian populations studied by extensive sampling. Of course, in comparison with frequencies of I1a in Scandinavia (25-40%), this local maximum is minor. But its remoteness from the main zone of high frequencies of this haplogroup in Scandina-

via requires explanation. It is hard to explain this local maximum by close relations between Scan-dinavia and regions of Transvolga and basin of Vychegda excluding other relative Russian re-gions. Apparently, history of population of haplo-group I1a is more complicated than a simple ex-pansion from Scandinavia, and it may include an-cient relations between the Finno-Ugric peoples of Eastern Europe and the ancestors of German-speaking Scandinavians».

____________________________________________________________

Received: May 11 2010; accepted: May 12 2010; published: May 16 2010 Correspondence: [email protected]

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

2

Fig. 1. Map of presence of haplogroup I1 (Balanovsky et al. 2008 [5]).

Krasnoborsk, Archangelsk region 12,1%

Vologda 11,6%

Unzha, Kostroma region 11,5%

Complete the data about the region in question from works of other researchers to compare the

spatial distribution of haplogroup I1:

Vologda Region 17,0% (Roewer et al. 2008 [3]*)

Archangelsk 14,2% (Mirabal et al. 2009 [6])

Ryazan Region 14,0% (Roewer et al. 2008)

Tatarstan 13,0% (Genofond.ru**)

Moksha people from Staro-Shayga district of Mordovia 12,0% (Rootsi et al. 2004 [7])

Penza region 12,0% (Roewer et al. 2008)

Kostroma 11,3% (Underhill et al. 2007 [1])

Tambov region 10,0% (Roewer et al. 2008)

Ivanovo region 10,0% (Roewer et al. 2008)

Data from additional sources confirm the exis-

tence of a local maximum of I1-M253 in the cen-tral part of European Russia. The boundaries of

this local maximum can be seen clearly on the map (Figure 2) developed by the author.

_____________________________________________________________

*Calculation of frequency of haplogroup I1 was carried out by predictor, ** data was taken from the atlas at Genofond.ru)

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

3

Fig. 1. Map of distribution of frequencies of haplogroup I1-M253.

Due to the fact that detailed studies (for) cla-rifying the reason of such high local frequencies of haplogroup I1 on such a wide area still don`t exist, let us try to fill up the gap by analyzing da-ta from published papers, linking data of genet-ics, archeology, linguistics, anthropology and other related sciences.

Since there is no reliable data about historical migrations from Scandinavia, which could have left such a significant mark on the territory of modern Russia, we will try to consider all availa-ble variants.

Goths of Ermanaric. Ermanaric (died in 376)

was the king of the Goths from the Amali clan. Gothic historian Jordanes wrote about Ermanaric [8]: «Soon after Geberich, king of the Goths, had passed away from human deeds, Hermanaric, the noblest of the Amali, succeeded to the throne. He subdued many warlike peoples of the north and made them obey his laws. Many ancient authors

had justly compared him to Alexander the Great. Among the tribes he conquered were the Gol-thescytha, Thiudos, Inaunxis, Vasinabroncae, Me-rens, Mordens, Imniscaris, Rogas, Tadzans, Athaul, Navego, Bubegenae and Coldae». (Here the researchers assume the prototype of enume-ration from Russian Chronicles: Rus, Chud and all languages: Ves, Merya, Mordvins (?)...)

Ermanaric and his Goths probably could not

have made a significant mark on the territory of modern Russia - especially in this region, be-cause the existence of such vast empire is quite doubtful (Fig. 3). Even if this Empire had existed, its age wasn`t long because of the invasion of Huns. Goths are associated with Chernyakhov

archaeological culture (III century AD), and therefore we should look for descendants of Goths among the mountain population of the Crimean Tartars (Tata) and the Greeks of Azov region, comparing their haplotypes with the hap-lotypes of population of northern Spain and Got-land.

Varangians. Varangian invasions (IX-XII cc.)

could also made their mark in the gene pool of Eastern Europe, though basic routs of Varangians had passed away from examined areas. The finds related to the Scandinavians point rather at trade relations, than expansion. Therefore the Varan-

gians had to be excluded from the list of possible contenders who could have left a significant mark in the gene pool of eastern Europe. Though it`s quite possible that a part of the Normans could have settled and assimilated with the local popu-lation of this region [10].

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

4

Fig. 3. «Empire of Ermanaric» in IV century AD and the assumed itinerary of III-IV centuries AD (by BA Rybakov). a – peoples mentioned in the list of Jordanes; b – the order of the peoples; c – the main areas of Cherniakhov culture in II-IV

centuries AD.; d – direction of sea expansions in III century AD; e – direction of Slavic colonization in III-IV centuries AD. [9].

Ancient migrations. Probably, we deal with ancient migrations on the territory of Eastern Eu-rope, assumed by The Balanovskys. That seems reasonable, given the exclusively European area of haplogroup I-M170.

If haplogroup I1-M253 is linked with the an-

cient population of Europe, it is quite possible that they were the speakers of Paleo-European language.

Researches of Serebrennikov BA [11] have

showed that the ancient substrate toponyms of unknown origin (i.e. non-Uralic and non-Indo-

European) are presented on the territory between Volga and Oka rivers. Also it is widely spread in the Nizhny Novgorod area (no data), Chuvashia (7,5% I1), Kirov region (no data), Vologda region (17% I1), Archangelsk region (14,2%), in Karelia (8,6% I1) and in the west of Smolensk region (2% I1).

Examples of substrate toponyms with end-ings:

– ga (Yuzga – branch of Moksha, Arga –

branch of Alatyr, Vyazhga – branch of Moksha and Volga)

– ta (Pushta – branch of Satis, etc.); – sha (Ksha – branch of Sura, Shoksha); – ma (Losma – branch of Moksha, Shalma –

branch of Sivin);

– da (Amorda) [12]. On the basis of Serebrennikova’s study Tre-

tyakov PN offered a hypothesis that this Paleo-European language belonged to the creators of the Neolithic cultures of the comb ceramics (CCC) [13].

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

5

CCC had originally occupied the territory of the Volga-Oka-Klyazma rivers. In 3rd millennium BC its carriers moved to the north and north-

west, where they settled on the territory from the Baltic sea to Vychegda and Pechora.

Craniological data suggest that the carriers of CCC of Lyalovo type are very heterogeneous. Lyalovo people was generated by alien Nordic

population of Sami subrace (Fig. 4, at right) and the aboriginal Mesolithic population of Caucasoid people of Volga-Oka post-Swiderian culture - as the carriers of Upper Volga culture [14].

Fig. 4. Sculptural reconstruction of the skull of a man from Valadar* (the lower reaches of the Oka region) [15]

and the skull of a young man from the burial № 19 of the Sakhtysh II sepulcher (Ivanovo region) [16].

Culture of Upper Volga had spread in the cen-

ter of the Russian Plain since the turn of the 6-5th millennium BC until the end of 5th millennium BC. The earlier monuments of Upper Volga culture

are concentrated in the eastern part of its area, the later – in the central and western areas that is apparently due to the arrival of new alien population.

Fig. 5. Area of Upper Volga, Volosovo and Fatyanovo cultures [17].

_____________________________________________________________ *This site refers to the culture more ancient than Upper Volga and Volosovo

archaeological cultures, but the sculptural reconstruction reflects more close-ly the image of Caucasoid population of the Volga-Oka Mesolithic post-Swiderian tradition

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

6

At present the hypothesis of origin of Volga-Oka culture and CCC from the Volga-Oka Meso-lithic post-Swiderian tradition is the most plausi-

ble, since the transition from Mesolithic to Neo-lithic was smooth and Butovo culture prevailing in the end of the Mesolithic in the Volga-Oka region also succeeded to the Swiderski tradition [18].

Swiderian culture is the archaeological culture

of the final Paleolithic on the territory of Central and Eastern Europe. Due to the changes of cli-matic conditions in the 11-10th millennium BC people of Sviderian culture began to move from the area of modern Poland, Belarus and Lithuania to the east and reached the given region of Vol-ga-Oka rivers in 8th millennium BC.

The same processes forced the migrations of the neighboring population of carriers of Ahrens-burgian tradition, probably allied to the people of

Sviderian culture. This Paleolithic culture existed in 10-9th millennium BC in Denmark and Northern Germany; the main occupation of this population was hunting for reindeer.

In 10th millennium BC people of Ahrensbur-

gian culture began to move following two direc-tions of the retreating ice cover – to the north-west and north-east, passing along both sides of the Baltic glacial lake (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Stages of the formation of Baltic Sea basin [19].

1. Baltic Ice Lake (about 16 thousand years BC). 2. Yoldia Sea (about 7,9 thousand years BC).

3. Ancylus Lake (about 6,8 thousand years BC). 4. Littorina Sea (about 5 thousand years BC).

Arensburgian people established a number of so-called «culture of Maglemose» in 8-6th millen-nium BC. These are such cultures as Fosna-Hensbacka in Sweden and Norway, Komsa in the far north of Scandinavia, including the Kola Pe-ninsula, Askola and Suomusjärvi in Finland and

Karelia, Veretye in east the lakeside of Ladoga, Kunda in the Neva region, Estonia, Latvia and Maglemose in England, Northern Germany and Denmark.

It is necessary to mantion that most high di-versity of haplotypes of I1-M253 - a is fixed it in Denmark [1], which is the starting point of people of Arensburgian culture.

If the assumption about the relationship be-

tween carriers of Ahrensburgian and Swiderian cultures is correct, then we will observe similar anthropological, linguistic and genetic situation in Scandinavia.

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

7

Fig. 7. Mesolithic (8.-5. mil BC) roots of Early Iron Age substratum components. [18].

Legend: 1 – Maglemose-Ertebølle tradition (M – Maglemose incl. English Maglemose; F – Fosna; K – Komsa; A – Askola; S – Su-omusjärvi); 2 – Świdry tradition (Ś – Świdry, Co – Baltic Typical Comb Pottery culture); 3 – area of formation of Pit-and-Comb

Pottery cultures of Central Russia.

Anthropological type of carriers of Ahrensbur-

gian culture had a characteristic sharp dolicho-cranic (Fig.8.) broad-faced Caucasoid type, which

corresponds well to the post-Sviderian aboriginal type in the Volga-Oka region, who had a dis-tinctly Caucasoid dolichocranic type with the nar-row face. The same anthropological type partici-pated in formation of the Sami. Comparison of anthropological data shows that Sami type

presents features of the ancient North-European population and more recent features associated with penetration of the Mongoloid features to the

north. The combination of the two components led to the formation of anthropological features of Sami people. Dentistry also notes the existence of ancient Northern and recent Mongoloid fea-tures among Sami [20].

Fig. 8. Examples of different skull types [21].

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

8

In the Sami language two components are al-so made out. The first is Pre-Finnish substratum, the second is the Old Finnish, which is close to

the Baltic-Finnic and Finno-Volgaic languages. The legacy of the Pre-Finnish substratum can be seen well in the lexicon, less in the morphology, phonetics and syntax. According to specialists, up to one third of the Sami lexicon is of substratum origin, and has no analogies in any of the existing languages of the world [20].

Genetic evidence suggests that haplogroup I1,

with which we associate Paleo-European popula-tion of Northern Europe, has the following fre-quencies in the Sami gene pool: Sami – 28% [7], the Sami from Sweden – 32% [22], Inari Sami– 34% [23]*, Skolt Sami – 52% [23], Sami from Lujávri (Lovozero) – 17% [23].

Based on the stated data the hypothesis

about the connection between haplogroup I1 and

Paleolithic population of Europe looks very con-vincing.

Analysis of sources allows us to reconstruct the population history of haplogroup I1-M253 the following way:

It is not clear yet how and when carriers of

haplogroup I appeared in Europe, this question is being dicussed at present. It is not also clear when and where I1 separated from I. However, in the Paleolithic era carriers of haplogroup I1 settled in in the northern part of central Europe of the territory of present Denmark, northern Germany and Poland. They created such cultures as Ahrensburgian and Swiderian (the author does not exclude the role of carriers of I2a in forming of Swiderian culture); their main occupation was hunting (predominantly for reindeer, elk (Fig. 9) and beaver) and gathering.

Fig. 9. The elk. The skeleton of an elk aged 8700 years was found in a peat bog in 1922 near the town Taderup.

Elk was wounded, in the same bog harpoon was found [26].

_____________________________________________________________

*Haplogroup I1 is not typed in this paper, but the results of other studies [24]

and public DNA projects [25] allow us to declare it

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

9

In 11-10th millennium BC global climate changes took place, this led to the melting of the ice cover in Scandinavia. Vegetation penetrated

to the territories cleared from the ice cover, with the main food of local population – reindeer – fol-lowing after it; that caused the migration of Pa-leolithic hunters. The colonization of Scandinavia, Baltic and Central Eastern Europe was started.

In the Mesolithic haplogroup I1 faced the

eastern newcomers, who related confidently with haplogroup N1c. They had Uraloid appearance (with a Mongoloid and Caucasoid features). Spreading of Uralic languages in Eastern Europe is connected with N1c.

Relations between the newcomers and abori-

ginal population were generally peaceful; it is evident from mixed graves and gradual appear-ance of mixed anthropological types.

The next important step to the formation of

present situation was made by the carriers of

cord ceramics cultures, who had haplogroup R1a [27], and were related to the spreading of South-ern European agricultural and pastoral tribes in Central Europe.

In the 3rd millennium BC tribes of corded ce-

ramics from Central Europe entered the Baltic region (Corded ware culture) and the upper and middle Volga areas (Fatyanovo-Balanovo cul-tures, (Fig. 5)). Their anthropological type was sharply dolichocranic with moderately broad-Caucasoid type [28].

Most likely the tribes of corded ceramics were

quite aggressive and forced out aboriginal popu-lation (I1/N1c) to the remote areas and partially assimilated it. Aboriginal population could not compete with the newcomers economically and

militarily, because it was not familiar with metal-lurgy and productive farming [29].

Mass migration of Slavic tribes (VII-VIII cen-turies AD) that have made significant changes to the gene pool of Eastern Europe should also be mentioned. The Slavs were mainly the carriers of haplogroup R1a (more) and I2a.

As a result of these processes carriers of Hap-

logroup I1 were partially displaced from their areals and assimilated by more developed new-comers.

In the end I would like to highlight the basic

conclusions: - Roots of haplogroup I1 evidently came from

such Paleolithic cultures as Ahrensburgian and Swiderian; its carriers represented were the part of autochthonous population of Northern and Eastern Europe.

- The main activities of carriers of haplogroup I1 were hunting and gathering.

- Initial anthropological appearance of carriers

of haplogroup I1 was sharply dolichocranic, broad-faced, tall Caucasoid type.

- Carriers of haplogroup I1 were speakers of

Paleo-European language, which didn’t belong to the Uralic or Indo-European families. Its traces were reveiled in the European toponimy and in the Sami language.

Compact local maximum of frequencies of I1

in the center of the Russian Plain is the conse-quence of ancient migrations of Paleolithic popu-lation of Europe, which led to the foundation of Upper Volga culture (the 6-5th millennium BC).

References 1. Underhill PA, Myres NM, Rootsi S et al: New phylogenetic

relationships for Y-chromosome haplogroup I: reapprais-

ing its phylogeography and prehistory; in Mellars P, Boyle K, Bar-Yosef O, Stringer C (eds): Rethinking the Human

Revolution. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute Mono-graphs, 2007, pp 33– 42.

2. Di Gaetano C, Cerutti N, Crobu F et al: Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by

genetic evidence from the Y chromosome. Eur J Hum Ge-

net 2009; 17: 91– 99. 3. Roewer L., Willuweit S., Krüger C. et al. 2008 Analysis of Y

chromosome STR haplotypes in the European part of Rus-sia reveals high diversities but non-significant genetic dis-

tances between populations Int J Legal Med. 4. Балановская Е. В., Балановский О. П. Русский генофонд

на Русской равнине. – М.: Луч, 2007. 5. Balanovsky et al. Two sources of the Russian patrilineal

heritage in their Eurasian context. Am J of Hum Genet 2008; 82: 236– 250.

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

10

6. Mirabal S, Regueiro M, Cadenas AM et al. (2009) Y-

Chromosome distribution within the geo-linguistic land-scape of northwestern Russia. Eur.J.Hum.Genet.

7. Rootsi et al. 2004 Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Hap-logroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene

Flow in Europe, Am. J. Hum. Genet. , 2004, vol. 75, pp. 128–137.

8. Иордан. О происхождении и деяниях гетов. Спб. Але-тейя. 1997.

9. Рыбаков Б.А. - Язычество Древней Руси.1987. 10. Пушкина Т.А. О проникновении некоторых украшений

скандинавского происхождения на территорию Древ-ней Руси//Вестник МГУ. История. 1972. № 1.

11. Серебренников Б. А. 1955. Волго-окская топонимика на территории Европейской части СССР // Вопросы язы-

кознания. №6. Москва. 12. Цыганкин Д.В. Мордовская архаическая лексика в то-

понимии Мордовской АССР. / «Ономастика Поволжья». Выпуск 4. – Саранск, 1976.

13. Третьяков П. Н. 1958. Волго-окская топонимика и во-просы этногенеза финно-угорских народов // Совет-

ская этнография. №4. Москва. 14. Костылева Е.Л., Уткин А.В. Краткая характеристика

антропологических типов эпохи первобытности на тер-ритории Ивановской области, Проблемы отечественной

и зарубежной истории: Тез. докл. Иваново, 1998. С. 55-57.

15. Герасимов М. М. Восстановление лица по черепу: со-временный и ископаемый человек. - М., 1955. - С.

377. 16. Лебединская Г.В. Облик далеких предков: Альбом

скульптурных и графических изображений. - М.: Нау-ка, 2006.

17. Рисунок взят с сайта http://www.prezidentpress.ru/ 18. Напольских В.В. Происхождение субстратных палеоев-

ропейских компонентов в составе западных финно-угров. // Балто-славянские исследования 1988-1996.

М., 1997. 19. Рисунок взят с сайта Георгия Хохлова

http://hohloff-spb.narod.ru/cayt/golocen.html

20. Манюхин И.С. Этногенез саамов Ижевск 2005 (опыт комплексного исследования).

http://elibrary.udsu.ru/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/655/05_12_010.pdf?sequence=2

21. Рисунок взят с сайта Балто-Славика, http://www.balto-slavica.com/

22. Karlsson, A. O., Wallerstrom, T., Gotherstrom, A., Hol-

mlund, G. (2006) Y-chromosome diversity in Sweden – a

long-time perspective. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 14, 963–70. 23. Raitio M., et al., Y-chromosomal SNPs in Finno-Ugric-

speaking populations analyzed by minisequencing on mi-croarrays, Genome Res. 11 (2001) 471–482.

24. Pericic, M., Lauc, L.B., Klaric, A.M. et al. High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces ma-

jor episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic popula-tions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1964-1975 (2005).

25. Family Tree DNA Saami Project http://www.familytreedna.com/public/Saami/default.aspx

26. Рисунок взят с сайта http://oldtiden.natmus.dk/ 27. Haak, W., Brandt, G., de Jong, H., Meyer, C., Ganslmeier,

R., Heyd, V., Hawkesworth, C., Pike, A., Meller, H., and Alt, K. (2008). Ancient DNA, Strontium isotopes and os-

teological analyses shed light on social and kinship organ-ization of the Later Stone Age. Proceedings of the Nation-

al Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 18226-18231.

28. Денисова Р.Я. 1975. Антропология древних балтов.

Рига. 29. Крайнов Д.А., Лозе И.А., 1987. Культуры шнуровой

керамики и ладьевидных топоров в Восточной Прибал-тике. // Археология СССР. Эпоха бронзы лесной поло-

сы СССР. М. 30. Бадер О.Н. О древнейших финно-yrpax на Урале и

древних финнах между Уралом и Балтикой // Пробле-мы археологии и древней истории угров. М., 1972.

31. Боготова З.И. Изучение генетической структуры попу-ляций кабардинцев и балкарцев. Уфа – 2009 Авторе-

ферат диссертации на соискание ученой степени кан-дидата биологических наук.

32. Лобов А.С. Структура генофонда субпопуляций баш-кир. Автореферат на соискание ученой степени канди-

дата биологических наук. Уфа. 2009. С.15. 33. Напольских В.В. К реконструкции лингвистической

карты Центра Европейской России в раннем железном веке // Арт. №4. Сыктывкар, 2007; стр. 88-127.

34. Напольских В.В. Предыстория уральских народов // Acta Ethnographica Hungarica. T. 44:3-4. Budapest,

1999; стр. 431-472. 35. Харьков В.Н., Степанов В.А., Медведева О.Ф. и др.

Различия структуры генофондов северных и южных алтайцев по гаплогруппам Y-хромосомы // Генетика.

2007. Т. 43. № 5. С. 675–687. 36. Харьков В.Н., Медведева О.Ф., Лузина Ф.А., Колбаско

А.В., Гафаров Н.И., Пузырев В.П., Степанов В.А.. Сравнительная характеристика генофонда теле-

утов по данным маркеров Y-хромосомы. Генетика. 2009. Т. 4.

37. Юнусбаев Б.Б.. Популяционно-генетическое исследо-вание народов Дагестана по данным о полиморфизме

Y-хромосомы и Alu-инсерций: дис. канд. биол. наук: 03.00.15 Уфа, 2006 107 с. РГБ ОД, 61:07-3/183.

38. Abu-Amero et al Saudi Arabian Y-Chromosome diversity and its relationship with nearby regions // BMC Genetics

2009, 10:59 doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-59. 39. Battaglia V, Fornarino S, Al-Zahery N, Olivieri A, Pala M,

Myres NM, King RJ, Rootsi S, Marjanovic D, Primorac D,

Hadziselimovic R, Vidovic S, Drobnic K, Durmishi N, Tor-roni A, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, Underhill PA, Semino

O Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in Southeast Europe European Journal of Hu-

man Genetics, Vol. 17. No. 6. (June 2009), pp. 820-830. 40. Capelli C, Redhead N, Abernethy JK, Gratrix F, Wilson JF,

Moen T, Hervig T, Richards M, Stumpf MP, Underhill PA,

Bradshaw P, Shaha A, Thomas MG, Bradman N, Goldstein

DB (2003) A Y chromosome census of the British Isles. Curr Biol 13:979–984.

41. Cinnioglu C, King R, Kivisild T et al: Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia. Hum Genet

2004; 114: 127– 148. 42. Csányi B., Bogácsi-Szabó E., Tömöry G., Czibula A.,

Priskin K., Csısz A., Mende B., Langó P., Csete K., Zsolnai A., Conant E.K., Downes C.S. and Raskó I. Ychromosome

analysis of ancient Hungarian and two modern Hunga-rian-speaking populations from the Carpathian Basin. Ann

Hum Genet 2008. 72: 519-534. 43. Dupuy BM, Stenersen M, Lu TT, Olaisen B: Geographical

heterogeneity of Y-chromosomal lineages in Norway. Fo-rensic Sci Int 2005; Epub. December 6.

44. Fornarino S. et al, "Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome di-versity of the Tharus (Nepal): a reservoir of genetic varia-

tion," BMC Evolutionary Biology 9:154, 2009.

The Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy: Vol 1, №2, 2010 ISSN: 1920-2989 http://ru.rjgg.org © All rights reserved RJGG

11

45. Heinrich M., Braun T., Sänger T, Saukko P., Lutz-

Bonengel S. and Schmidt U. Reduced-volume and low-volume typing of Y-chromosomal SNPs to obtain Finnish

Y-chromosomal compound haplotypes Int J Legal Med (2009), 123(5): pp. 413-418.

46. King RJ, Ozcan S, Carter T et al: Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cre-

tan Neolithic. Ann Hum Genet 2008; 72: 205– 214. 47. Kharkov V. N. Kharkov, V. A. Stepanov, O. F. Medvede-

va, M. G. Spiridonova, N. R. Maksimova, A. N. Nogovitsi-na, and V. P. Puzyrev, "The origin of Yakuts: Analysis of

the Y-chromosome haplotypes, " Molecular Biology, Vo-lume 42, Number 2 / April, 2008.

48. Kasperaviciute D, Kucinskas V, Stoneking M. 2004. Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA variation in Lithua-

nians. Ann Hum Genet 68:438–452. 49. Kushniarevich A.I., Sivitskaya L.N., Danilenko N.G. et al.

Y-chromosome gene pool of Belarusians – clues from bial-lelic markers study // Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2007. V. 51.

№ 5. P. 100–105. 50. Lappalainen T, Laitinen V, Salmela E, Andersen P, Huopo-

nen K, et al. (2008) Migration Waves to the Baltic Sea Region. Ann Hum Genet. 72: 337–348.

51. Lappalainen et al, Regional differences among the Finns: A Y-chromosomal perspective. Gene Apr 28, 2006.

52. Lappalainen, Tuuli 2009: Human genetic variation in the Baltic Sea Region: features of population history and nat-

ural selection. Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland (University of Helsinki, Finland) and Department of Bio-

logical and Environmental Sciences (Faculty of Bios-ciences).

53. Luca. F., Di Giacomo. F., Benincasa. T., Popa. L. O., Ba-nyko. J., Kracmarova. A., Malaspina. P., Novelletto. A.,

Brdicka. R., Y-chromosomal variation in the Czech Repub-lic American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2007, vol

132; Number 1, pages 132-139. 54. Marjanovic D, Fornarino S, Montagna S et al: The peopl-

ing of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome hap-logroups in the three main ethnic groups. Ann Hum Genet

2005; 69: 757– 763.

55. Marjanovic, D; Fornarino, S, Montagna, S, Primorac, D, Hadziselimovic, R, Vidovic, S, Pojskic, N, Battaglia, V,

Achilli, A, Drobnic, K, Andjelinovic, S, Torroni, A, Santa-chiara-Benerecetti, AS, Semino, O (2005). The peopling

of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome haplo-

groups in the three main ethnic groups. Annals of Human

Genetics 69 (6): 757–763. 56. Martinez L, Underhill PA, Zhivotovsky LA et al: Paleolithic

Y-haplogroup heritage predominates in a Cretan highland plateau. Eur J Hum Genet 2007; 15: 485–493.

57. Noveski et al. Y chromosome single nucleotide polymor-phisms typing by SNaPshot minisequencing // Balkan

Journal of Medical Genetics, 12 (2), 2009. 58. Passarino G., Cavalleri G.l., Lin A.A. et al., "Different ge-

netic components in the Norwegian population revealed by the analysis of mtDNA and Y chromosome polymor-

phisms," European Journal of Human Genetics (2002) 10, 521 – 529.

59. Petrejčíková E., Siváková D., Soták M., Bernasovská J., Bernasovský I., Sovičová A., Boroňová I., Bôžiková A.,

Gabriková D., Švíčková P., Mačeková S., Čarnogurská J. Y-STR Haplotypes and Predicted Haplogroups in the Slo-

vak Hoban Population Journal of Genetic Genealogy Vo-lume 5, Number 2 ISSN: 1557-3796 Fall, 2009 A Free

Open-Access Journal. 60. Sengupta S, Zhivotovsky LA, King R et al: Polarity and

temporality of high-resolution Y-chromosome distribu-tions in India identify both indigenous and exogenous ex-

pansions and reveal minor genetic influence of central Asian pastoralists. Am J Hum Genet 2006; 78: 202– 221.

61. Sengupta S., Zhivotovsky L., King R., Mehdi S.Q., Ed-monds C.A., Chow C-E.T., Lin A., Mitra M., Sil S., Ramesh

A., Usha Rani M.V., Thakur C.M., Cavalli-Sforza L., Ma-jumder P., Underhill P. «Polarity and Temporality of High-

Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal

Minor Genetic Influ-ence of Central Asian Pastoralists»// Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78 (2): 202–21.

62. Varzari A. (2006), "Population History of the Dniester-Carpathians: Evidence from Alu Insertion and Y-

Chromosome Polymorphisms," Dissertation for the Facul-ty of Biology at Ludwig-Maximilians University, München.

63. Zastera J., Roewer L., Willuweit S., Sekerka P., Benesova L., Minarik M. Assembly of a large Y-STR haplotype data-

base for the Czech population and investigation of its

substructure , 13 July 2009 Forensic Science Internation-al: Genetics April 2010 (Vol. 4, Issue 3, Pages e75-e78).