The Neo Abu Sayyaf - Cambridge Scholars · 2021. 4. 30. · List of Illustrations x Fig. 5.8....

Transcript of The Neo Abu Sayyaf - Cambridge Scholars · 2021. 4. 30. · List of Illustrations x Fig. 5.8....

The Neo Abu Sayyaf

The Neo Abu Sayyaf:

Criminality in the Sulu Archipelago of the Republic of the Philippines

By

Bob East

The Neo Abu Sayyaf: Criminality in the Sulu Archipelago of the Republic of the Philippines By Bob East This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Bob East All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9733-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9733-4

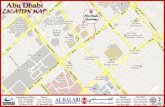

Fig. A. Map of the Sulu Archipelago area: Western Mindanao, Southern Philippines.

TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Tables .............................................................................................. xi Acknowledgments .................................................................................... xiii Preface ....................................................................................................... xv Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 7 Examining Historical Causes of Resentment Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 33 The Abu Sayyaf Flexes its Muscles Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 47 Selective Kidnappings Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 63 Counteraction, Criticism and Numerical Strength of the Abu Sayyaf Chapter Five .............................................................................................. 75 Various Leaders and Majordomos of the Abu Sayyaf Chapter Six ................................................................................................ 99 Basilan 2015: Unprecedented Violence and Other Events Chapter Seven .......................................................................................... 113 Sulu 2015: Violence and More

Table of Contents

viii

Conclusion ............................................................................................... 125 Bibliography ............................................................................................ 129 Index ........................................................................................................ 133

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. A. Map of Sulu Archipelago Fig. I.1. Abdurajak Janjalani Fig. I.2. Khadaffy Janjalani Fig. I.3. Abu Sabaya (wanted poster) Fig. 1.1. Map of original Moro Province Fig. 1.2. A Moro hanging in Sulu in 1911 Fig. 1.3. Moros massacred in 1906 (Bud Dajo) Fig. 1.4. Cardinal Quevedo Fig. 2.1. Lt. Gen. Donald Wurster Fig. 2.2. Abdul Mukim Edris on display Fig. 2.3. Fathur Rohman al-Ghozi (dead) Fig. 2.4. Hamsiraji Marusi Sali (dead) Fig. 2.5. 2004 Philippine presidential election results Fig. 3.1. Martin & Gracia Burnham Fig. 3.2. Guillermo Sobero (beheaded) Fig. 3.3. Ediborah Yap (killed in crossfire) Fig. 3.4. Map showing Palawan and the Sulu Sea Fig. 3.5 Vagni before capture Fig. 3.6 Vagni after release Fig. 3.7 Rodwell before capture Fig. 3.8 Rodwell after release Fig. 3.9 L/Horn & R/Vinciguerra before capture Fig. 3.10. Vinciguerra after his escape Fig. 3.11. Atyani before capture Fig. 3.12. Atyani after release Fig. 3.13. Okonek & Diesen just after kidnapping Fig. 3.14. Okonek & Diesen a short time before release Fig. 4.1. U.S. wanted poster of Sahiron Fig. 5.1. Abu Sayyaf members 2000 Fig. 5.2. Members of Abu Sayyaf wanted by the U.S. Government Fig. 5.3. Members of Abu Sayyaf wanted by the Philippine Government Fig. 5.4. Poster produced sometime in 2005 Fig. 5.5. Kristy Kenny displaying approval at the deaths Fig. 5.6. Albader Parad. Circa 2008 Fig. 5.7. A dead Albader Parad

List of Illustrations

x

Fig. 5.8. Wanted poster of a young Abu Jumdail Fig. 5.9. A hooded informant is rewarded Fig. 5.10. A sinister looking Khair Mundos Fig. 5.11. A nonchalant Harun Jaljalis Fig. 5.12 . A wounded Imran Mijal Fig. 5.13. The Zamboanga Peninsula Fig. 5.14 . Handcuffed Bon Sarapbil on display Fig. 5.15. Arasad Saidjuwan on display Fig. 5.16. A boyish-looking Mhadie Umangkat Sahirin Fig. 6.1. Map of Basilan Province Fig. 7.1. Sulu Province Fig. 7.2. Norwegian hostage Kjartan Sekkingstad Fig. 7.3. Hostages Flor, Ridsdel, Hall & Sekkingstad Fig. 7.4. Hostage Nwi Seong Hong

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1. Moro minoritisation: Zamboanga. Table 1.2. Moro minoritisation: Cotabato Table 1.3. Moro domination to 1970 (Sulu) Table 1.4. Moro domination continues (Sulu) Table 4.1. Estimates of Abu Sayyaf operatives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This author wishes to acknowledge the following persons—not in

order of importance—who contributed to the successful completion of this book.

Victor Taylor of the Philippines. Victor is a wealth of knowledge on

many aspects of state security and associated safety in the southern Philippines. His help—as usual—was always appreciated.

Dr. Peter Sales of the Wollongong University, Australia. Peter was

always ready to advise me on a region in which he has spent many years living and researching.

Dr. Eric Elks of Stanthorpe, Australia. Eric spent hours proof-reading

my manuscript, for which I am appreciative. Finally my sincere thanks to my Filipino wife, Maria Teresa East. Her

knowledge of her country’s languages were, and always are, invaluable to my research.

PREFACE

Basilan and the other provinces in the Sulu Archipelago have a

population the majority of whom are Muslims. This has been the make-up of the population in this region for centuries. Ever since the Spanish attempted colonisation of the greater Mindanao area (southern Philippines) in the mid to late 16th century there has been resentment from the local Muslims—known as Moros—and to a lesser degree from the native indigenous people.

It was crucial to the consolidation of Spanish power in the Philippines

for the local inhabitants to be converted to Christianity—namely Catholicism. This conversion occurred in other Spanish territories, and to a lesser degree it was successful in their newest colony—the Philippines. However the Moros of the greater Mindanao region resisted the attempt at conversion fiercely. Inter alia, Moro comes from the Spanish word Moro from the older Spanish word Moor, the Reconquista-period term for Arabs or Muslims.

From 1569 to 1762 there were continuing military confrontations

between the Spanish colonial forces and the Moros, who at that time occupied most of the greater area of the Philippines. These military confrontations were known as the Moro Wars and were significant because of Moro successes. In the two decades to 1596, the Spanish tried unsuccessfully to establish a colony in Mindanao and, significantly, in one military encounter, Christianised Indios, (Spanish word for natives of a country) fought against fellow Moros. For most of the 17th century the Moros of Mindanao, including the Sulu Archipelago were successful in repelling Spanish attacks, and even captured the Spanish fort in Zamboanga, the only region in Mindanao where there was a significant Spanish presence. The Moro Wars were to last until 1762 when the British occupied Manila in October of that year—this was during the Seven Years’ War. In May 1764 British troops withdrew from Manila and briefly occupied a number of islands in the Sulu Archipelago, eventually being evicted by the Moros around 1773.

Preface

xvi

However Spain, which had a formidable army and navy, was a very successful foreign occupier, and over the next 50 years or so were successful at not only colonisation in the Visayas and Luzon regions of the Philippines (central and northern Philippines) but religious conversion as well. This left only Mindanao, including the Sulu Archipelago, where the Moros were undefeated and retained their Islamic faith. Consequently, from 1829 until 1898—the year the United States of America (U.S.) acquired the Philippines after the Spanish/American War—an uneasy truce existed between the Spanish colonial forces and the Moros of the southern Philippines.

From 1898 to the time of writing 2015/16 there has been unrest in the

greater Mindanao area, especially the Sulu Archipelago region. This region has seen U.S. colonization, Japanese invasion and occupation, minoritisation of the Muslim population and continued unrest and at times fierce fighting between the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Moros in all their complexities and groups. This fighting and general unrest continues today and is, in part, included in this publication.

This publication, unlike other publications analysing the alleged Abu

Sayyaf Group—hereafter just called the Abu Sayyaf—in Basilan Province and the immediate region, does not strictly follow a chronological format. It examines the first decade and a half of the 21st century of these troubled provinces in the context of—not exhaustive—kidnaps-for-ransom, AFP presence and armed clashes with the Abu Sayyaf, various leaders and majordomos of the Abu Sayyaf, political involvement, and the influence the Catholic Church had and still has on political decisions. Of course it was necessary to examine historical events that may have influenced contemporary events—hence the chronological “jumping”.

In the 15 years since 2000 the amount of violence and associated

criminality attributed to—as the media would now prefer to call them “suspected Abu Sayyaf members”—has increased, at the time of writing to a position where almost daily there are reports of kidnappings, robberies and armed clashes between members of the AFP and suspected members of the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan Province, and of course its immediate neighbours especially Sulu Province.

If the three Philippine Administrations in the first 15 years of the 21st

century—Estrada, Macapagal-Arroyo, and Aquino—were correct in their assessments of who was responsibility for the lawlessness, in Basilan and

The Neo Abu Sayyaf

xvii

Sulu Provinces, then the blame lay squarely on members of the Abu Sayyaf. If the blame for the present increasing violence and associated criminality in Basilan and Sulu does indeed lie with the Abu Sayyaf then it a worrying escalation of what appeared to be decreasing Abu Sayyaf activity in the broader Mindanao region toward the end of the first decade of the 21st century.

Before examining this escalation of violence in Basilan, Sulu, and its

immediate neighbours—and other associated matters—it is important to firstly differentiate between the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan and the Abu Sayyaf in its neighbouring province, Sulu. In the latter part of the 20th century the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan came under the leadership/s or direction—for the most part—of Abdurajak Janjalani, his younger brother Khadaffy Janjalani, Abu Solaiman, and Abu Sabaya. It is fair to say at that time, in the main, the struggle for the most part was ideologically driven by a sense of attempting to gain self-determination for their fellow Moros. Negotiations for a peaceful transition to a form of self-determination had been ongoing since the historic 1996 Peace Agreement between the Ramos Administration and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). However frustration at the drawn-out process had surfaced, as well as discontentment with the other Moro paramilitary group the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) being ignored in 1996. This led to many Moros leaving both the MNLF and the MILF to join forces with the more aggressive Abu Sayyaf.

Of course for the Abu Sayyaf to be taken seriously in its endeavour for

Moro self-determination it needed a more aggressive stance to attain this goal—armed confrontation. Armed confrontation meant the necessity to secure weapons, preferably the M16, a self-loading rifle that fires a 5.56 x 45 mm NATO round. However the M16 is an expensive weapon, in Philippine terms—costing in the vicinity of USD $1400 (approximately 65,000 Philippine pesos)—and this amount had to be raised somewhere. Hence the necessity for criminal activity, in particular kidnaps-for-ransom.

In the latter part of the 20th century the Abu Sayyaf in Basilan and

Sulu—and to a lesser extent the southernmost province of the Sulu Archipelago, Tawi-Tawi—were, in the main homogeneous in objectives and ideology. However with the gradual and inevitable disintegration of the group due to lack of strong leadership—or indeed identifiable leadership—the Basilan and Sulu chapters of the Abu Sayyaf saw profit—for profit-sake—to be gained by continuing criminality and having it associated with the feared name of Abu Sayyaf. Ideology took a back-seat

Preface

xviii

to greed. As expected there was no shortage of eager young men willing to be associated with the name, and, consequently joined the ever increasing coterie of likeminded criminals. With the increasing numbers came various individuals jockeying for the position/s of leadership. And this will also be examined later.

This publication, unlike other publications analysing the alleged Abu

Sayyaf in Basilan and the immediate region, does not—as previously mentioned—strictly follow a chronological format. More so, it examines the first decade and a half of the 21st century of these troubled provinces because that was the period of greatest unrest. This in turn raises the question whether the criminality in 21st century Basilan/Sulu region is national terrorism, national insurgency, a combination of both, or something in between.

INTRODUCTION Terrorism and criminal activity would, at first glance, appear to be one

and the same because terrorist activity involves criminal behaviour. Unfortunately the Muslim domestic insurgency movement in the southern Philippines has been seen as terrorism—primarily because of its inclusion by the U.S. in their now defunct Global War on Terror. The main protagonists in this “war” in the southern Philippines—in particular the Sulu Archipelago region of Mindanao—were members of the Abu Sayyaf. Of interest: Academic and Australian doyen on Mindanao’s problems Dr Peter Sales of the Wollongong University describes the Abu Sayyaf as a criminal band composed entirely of thugs and criminals and any claims they may have about commitment to a Higher Cause, like the assertion that it belongs in company with the MILF or the MNLF as an Islamic force in Mindanao are nonsense. He goes on to state they are culturally corrupt—known for brutality not suicidal sacrifice.

The two other major Muslim paramilitary organisations in the southern

Philippines, the MILF and the MNLF—mentioned by Sales—were not included as protagonists in the U.S. Global War on Terror—although originally the MILF was for a short period but subsequently withdrawn from the “list” after a request from the then Philippine President, Gloria Arroyo to U.S. President George W. Bush. En passant, in 2008 another player came into the greater Mindanao region, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), however they have no physical presence in Basilan or Sulu rather their main area of operations appears, at this time to be the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) province of Maguindanao.

The Abu Sayyaf—in its true form—had its heyday in the last decade of

the 20th century and the first five years of the 21st century—perhaps a little more either end of this timeframe. It was during this time the Abu Sayyaf’s strength peaked at an estimated 1200 paramilitary operatives—although its sympathisers were probably considerably more. If unstopped it had the potential to become the Philippines behemoth—an Asian enclave of the modern day ISIL (ISIS)—ISTP? (The Islamic State in the Philippines).

Introduction

2

That the original Abu Sayyaf or indeed the “new look or neo” Abu Sayyaf in Basilan and adjoining regions do commit acts that may be described as “terror” or “criminal” is not in dispute. However, in the true sense of the word/s today, “international terrorism” does not fit comfortably within the context to describe the Abu Sayyaf—although most of their kidnap victims may be international in terms of race or ethnicity.

Fig I.1.Abdurajak Janjalani

It is believed that in 1990 Abdurajak Janjalani, the founder of the Abu

Sayyaf, returned to the Philippines—more than likely to Basilan his birthplace—from Afghanistan after allegedly fighting with the Taliban against Soviet troops. It was further believed Janjalani had met with Osama Bin Laden who gave him USD 6 million to help set up the Abu Sayyaf Group. (Exactly how Janjalani managed the logistics of carrying 6 million USD through the officials at the Manila International Airport is unknown). There is so much myth surrounding Abdurajak Janjalani that it is impossible to differentiate between what is fact and what is ephemera. Even the exact date of his birth—1959—is uncertain. That Abdurajak Janjalani, his father Abubakar, and four other male siblings including Khadaffy and Hector—serving a life sentence in Bilibid Prison, Muntinlupa City-Metro Manila—are/were Sunni Muslims is not disputed. As was their desire to see more autonomy for their fellow Moros. It would appear the elder of the Janjalani brothers—Abudurajak—favoured a more

The Neo Abu Sayyaf 3

peaceful approach unlike his other siblings. Of interest, Hector strenuously denied—and still does—he had anything to do with the Abu Sayyaf in the main.

In the last decade—or a little more—of the 20th century, the Abu

Sayyaf in Basilan under the leadership of Abdurajak Janjalani was highly organised. Not only did it have a chairman, as Janjalani was known, but an intelligence chief—Abdul Ashmad—and an operations chief—Ibrahim Yacob. (Both were more than likely former members of the MNLF). Unexpectedly, on 18 December 1998 in an encounter with AFP troops, Abdurajak Janjalani was killed outside the northern Basilan city of Lamitan. His death left a vacuum in the leadership of the Abu Sayyaf that was quickly filled by Abdurajak’s younger brother, Khadaffy—pictured. Khadaffy’s authority was titular at best more so than plenipotentiary. Other majordomos in the group, including Abu Solaiman and Abu Sabaya had leadership aspirations which led, at times, to tension.

Fig I.2 Khadaffy Janjalani

By the year 2000 the Abu Sayyaf had changed direction. At the behest

of Abu Sabaya—but more than likely with the blessing of Khadaffy Janjalani—the focus of operations went from ideological to mercenary. It soon became apparent to the various commanders, sub-commanders and majordomos of the Abu Sayyaf, especially in Basilan that to continue the

Introduction

4

struggle for self-determination for the Moros it would require money to purchase weapons and also to financially support its members and their families. Kidnappings-for-ransom appeared to be the easiest solution to liquidity problems.

Armed robbery has its logistical problems, and there is no guarantee of

success or even the amount to be gained. It is a complex exercise that requires careful planning and in most instances a high degree of callousness for the unfortunate victim/s. With kidnapping, the target first up has to be selected—preferably unarmed, rich, and a foreigner if possible. The amount to be realised would be subject to “negotiation”. Both Sabaya and Solaiman were quite adept in liaising techniques as opposed to the more maladroit Khadaffy Janjalani. In the future, crime for the Abu Sayyaf would become a criminal commercial enterprise.

Fig I.3 Abu Sabaya

.

The hostility and kidnappings eased somewhat in June 2002 when Abu Sabaya—wanted poster pictured—was killed in the Sulu Sea off the coast of Zamboanga. Of course the killing of Sabaya, and the subsequent killing of Khadaffy Janjalani—December 2006—and Abu Solaiman—January 2007—did not mean a halt in criminal activity. All it did was make the

The Neo Abu Sayyaf 5

Abu Sayyaf more factionalised. Inter alia, both Janjalani and Solaiman were killed on the neighbouring island (province) of Sulu indicating that either the Abu Sayyaf in Sulu was then under the direction of Janjalani or Solaiman or working in tandem with them—the latter being favoured.

As mentioned, the death of Khadaffy Janjalani did not signal a halt in

kidnappings or associated criminality in Basilan and the surrounding regions—this will be examined in later chapters. To the contrary, it ushered in opportunities for other like-minded criminals to engage in the lucrative activity of kidnappings-for-ransom, and of late the egregious crime of extortion. Consequently this, unfortunately, is how the media in the main see and portray the provinces of Basilan and Sulu at the time of writing—a hotbed of Abu Sayyaf criminality and a place to be avoided at all costs for purposes of personal safety.

The question must now be asked how did these beautiful tropical

islands, with some of the most pristine coastal scenery in all of the Philippines—Boracay included—acquire a reputation for being so unsafe? Although being classified as a 3rd class province—in terms of income—Basilan nevertheless has a much more even distribution of wealth than many other Philippine provinces—Sulu is down the ladder somewhat. When it comes to poverty Basilan is certainly not the poorest province in the Philippines. It has consistently been ranked third nationwide in the gap between rich and poor. As well, Basilan compares very well when measured against the GINI Coefficient for the Philippines overall. (The GINI Coefficient measures a nation’s income distribution.)

Therefore if poverty; an uneven distribution of wealth; a waning of

enthusiasm for self-determination—notwithstanding the proposal now for a separate political entity-Bangsamoro; the presence of large numbers of AFP personnel as well as U.S. advisors; a reasonably stable political situation—although with some exceptions; and a strategically well-constructed circumferential road in Basilan that can transport men and equipment anywhere on this island quickly—all abound, then the problem of continuing violence in Basilan and Sulu must have an underlying cause. Or had an underlying cause.

Has the incident of major crime including kidnappings, extortion,

beheadings, military action against the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the AFP, been a festering sore that “explodes” periodically? Is the violence opportunistic? Is it a deep-seated resentment to Malacanang and

Introduction

6

all it stands for? Is it the desire to keep the name of Abu Sayyaf alive and feared? Is it all of these scenarios or a combination of just some?

The following chapters do not attempt to give answers to the above

questions rather they just examine the various incidents that may have helped shaped Basilan and Sulu’s unfortunate violent contemporary history. (The reader or student can make his or her own assessment) Included in this study will be Catholicism, and the part it played, and still does, in dividing religious beliefs—either intentional or unintentional—and an uneven distribution of state funds to the Catholic Church. At the same time the examination of events both historical and contemporary may also give some inkling of where Basilan and the neighbouring province’s futures lie.

CHAPTER ONE

EXAMINING HISTORICAL CAUSES OF RESENTMENT

In 1905, Dr. Najeeb M Saleeby wrote in a book, Studies in Moro

History, Law, and Religion, that the Moros were a law-abiding people, provided however they felt the government which ruled them was their own. That the majority of the Muslim population of Basilan and adjoining provinces did not regard the central government sitting in Malacanang, Manila, as representing their interests was obvious. Whilst it is now true the Moros have congressional representatives and Senators they are, in the main, ineffectual when it comes to legislation because of numerical factors.

Where law and order breaks down—or is under pressure as it is in

Basilan and the other majority Muslim provinces at the time of writing—it is necessary to ascertain the likely causes. Of course “law” is dependent on what a society deems acceptable for stability, whereas “order” is what is necessary for everyday peaceful existence in a society. The following analysis of events is not meant to be conclusive, rather they are included in an attempt to make some sense of what was—and still is—a complex issue in a complex and historical part of the southern Philippines’ greater Muslim region, especially the Sulu Archipelago area.

There was no single incident that precipitated the unfortunate decline

in the predominant Muslim provinces in the 20th century. Rather it was an amalgam of events, some predicable; some intentional; some unintentional; some avoidable; some unavoidable; and some as a consequence of religious historical practice under threat. But nonetheless all adding to the growing animus toward the Christian minority population, and in particular for the most part, the non-Muslim composition of the authorities in charge of peace and security—PNP and AFP. Included in this chapter are a number of factors that may have influenced the way history evolved in the Sulu Archipelago area—and also the greater Mindanao region.

Chapter One

8

Minoritisation

Minoritisation of a race or clan can be either intentional or unintentional. Whatever adjective fits the exercise the consequence is usually the same—loss of influence. For the purpose of definition, intentional can be as a consequence of being purposely outnumbered, or unintentional as a result of natural events such as lower fertility. For the purpose of this examination the former—being outnumbered—is considered below.

The Sulu Archipelago may not have been intentionally or directly

affected by the various legislations of “minoritisation” in the first half of the 20th century, however it is important to understand how it affected the broader Moro population of Mindanao as a whole. Therefore it is necessary to look at the big picture because only then can minoritisation be fully understood for what it was.

Minoritisation did not directly affect Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi

because the Moro population in the Sulu Archipelago remained—and still does—relatively static in the way of Moro percentages. If Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi had been affected by minoritisation, then the number of Christians and non-Christians would be closer in number, thus breeding resentment by the Moros against those who were perceived as interlopers—that is exactly what occurred in many of the provinces in mainland Mindanao. That is not to say a greater number of Christians may have had a stabilising effect on some Moro dissidents in Basilan, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi because it may have had just the opposite effect. However both scenarios are speculative. The Abu Sayyaf—who are in the main the major bandit group in these island provinces—were not seen originally as dissidents but more as domestic or national insurgents. That is, antagonists fighting a national government which had some degree of legitimacy and popular support.

The following analysis of minoritisation is examined, and at times the

affected provinces are compared with the provinces of the Sulu Archipelago. Minoritisation did produce the MNLF and the MILF but it can be argued not the Abu Sayyaf. (The Abu Sayyaf presence came after the major minoritisation programs in the Mindanao mainland had, in most instances, ceased). However if the Muslim population had not been proportionally reduced then they would still be in the majority and represented in Congress accordingly. Crime may still have been present, but it could not have been used as an excuse for advocating “justice to the

Examining Historical Causes of Resentment 9

oppressed”. Minoritisation of Mindanao Muslims is a complex issue but needs to be examined in part here to see how it affected the Moros in the broader context, which includes the 13 ethnolinguistic tribes in that region.

In the 20th century the Moros went from being an ethnic majority to an

ethnic minority. The ability of an ethnic group to influence or “supervise” their own, decreases when another group achieves majority—law enforcement agencies with their respective officers, in the main, come from the major group. This can breed resentment in the minor group. And this is exactly what has occurred in the greater Mindanao region especially since the post-Commonwealth period—1935. Inter alia, although Basilan for example is in the majority, Muslim, its law enforcement officers—PNP and especially AFP—are for the most part Christians from the northern Philippines.

Minoritisation by outnumbering meant allowing an influx of Christians

from Luzon and the Visayas into the greater Mindanao region. However to do this there would need to have been an incentive for these Christians to migrate south. The original indigenous inhabitants of the northern regions, including the Kalingas and Isnegs would not have had any desire to migrate. The Kalingas and Isnegs were, in the main, primary producers on the fertile areas of northern Luzon. The incentive for Christian migration was the attractiveness of opening up land holdings to them. This first came about with the enactment of Act No. 926 in 07 October 1903. This Act declared all land to be public—basically government land, or what is known in British Commonwealth countries as Crown Land. Act No.926 is reproduced below with an important caveat bolded and in italic.

Act No. 926: An act prescribing rules and regulations governing the homesteading, selling, and leasing of portions of the public domain of the Philippine Islands, prescribing terms and conditions to enable persons to perfect for the issuance of patents without compensation to certain native settlers upon the public lands, providing for the establishment of town sites and sales of lots therein, and providing for a hearing and decision by the court of land registration of all applications for the completion and confirmation of all imperfect and incomplete Spanish concessions and grants in said islands, as authorized sections thirteen, fourteen and fifteen of the Act of Congress of July first nineteen hundred and two, entitled “An Act to Provide for the Administration of the Affairs of Civil Government in the Philippine Islands, and for Other Purposes”. (Chan Robles)

Chapter One

10

The full extent of Act No.926 and what it meant for the original inhabitants—predominately Moro—of the greater Mindanao region was not immediately obvious. Some Sultans and their Datus (princes and/or chiefs) were believed to have been happy the Mindanao region would be classified as “public land”. Perhaps they believed in some arcane way they would be able to increase their landholdings. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s that the full effect of Act No 926 became obvious. The official name given to the period when the Moros were disenfranchised in their homeland was “resettlement”. Minoritisation may appear to be a dysphemistic noun for the word “resettlement”, however the facts speak for themselves.

At this time in the analysis of the minoritisation period it may be

perspicuous to show the trend of Christian migration from Luzon and the Visayas to the Mindanao region from 1903 to 1970—1970 being the early part of the Marcos Administration. During the early part of the Marcos Administration the Moros of the southern Philippines became “militarily organised” and this was one of the reasons Marcos gave for implementing marshal law—domestic insurgency including action from both the Moros and home-grown communists.

It is quite valid to argue that had the migration from the north not been

as severe as it was, and equilibrium—in numbers—of Moros and Christians been the result then the unrest and domestic counterinsurgency may not have occurred because political representation would have been roughly equal. However this is pure speculation—the facts and effects of minoritisation remain.

The migration from the north was very effective and it achieved a

greater degree of minoritisation than had been anticipated. It resulted in the partial disenfranchisement of the original—or ethnic population apart from the indigenous people—over a period of only seven decades. The various Acts, resettlement initiatives, and other official actions enacted and undertaken by various American and Philippine administrations during these seven decades are listed below. Minoritisation of original inhabitants in an occupied region/country may not have been new, however in the greater Mindanao region it paved the way for future counterinsurgency policies and other actions by Manila.

The 1913 Act 2254, known as the “Agricultural Colonies Act” created

agricultural regions in the Cotabato Valley—as opposed to Cotabato

Examining Historical Causes of Resentment 11

Province. These regions were Pikit, Pagalungan and Glan. Pikit today forms part of North Cotabato, Pagalungan a part of Maguindanao, whilst Glan is a part of Sarangani. The Act was intended to open up land for agricultural use. (The Mindanao region was—and still is—considered the agricultural basin of the Philippines). It was also hoped that Act 2254 would attract Christians—with the necessary agricultural skills—from the northern regions of the Philippines. (Very successful in North Cotabato where today the Muslims are in minority). Christians from Cebu formed the first batch of migrants under Act 2254 in June 1913 and they settled in Pikit. It is not meant here to suggest Act 2254 was intended to be the sole tool for the minoritisation of the Moros—but it certainly did not hinder the process.

Act 2254 came into being during the time of the Moro Province—June

01, 1903 – July 23, 1914. 1913 was the penultimate year of the Moro Province after which the area went from military to civilian government The Moro Province formed part of today’s provinces of the Cotabatos, the Zamboangas, the Davaos, the Lanaos, Maguindanao, Sarangani, and the Sulu Archipelago provinces of Basilan, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi. The Moro Province saw many conflicts between Moros—who were only showing resentment at being colonised—and the U.S. Military. Justice was swift—and brutal—for Moros convicted of crimes against the U.S. military. As well it was during this period that one of worst massacres of Moros to have ever occurred took place in a volcanic crater on Jolo Island in today’s Sulu Province.

Fig 1.1 Map of the original Moro Province.

Chapter One

12

Fig 1.2 A Moro hanging in Sulu in 1911

Bud Dajo (in brief)

Now referred to as the Bud Dajo Massacre, upward of 800 Moros—many of whom were women and children—were massacred by U.S. Troops under the control of Colonel J.W. Duncan, who in turn was under orders from General Leonard Wood to either kill or capture those “savages”—as Wood referred to the local Moros. Such was Wood’s enthusiasm to have the Moros butchered he took advantage of a position overlooking the crater where the Bud Dajo massacre occurred. Wood wished to witness the event first-hand. After the massacre, U.S. soldiers were photographed in front of a pile of dead Moros—the iconic photo below clearly shows a Moro female, breast exposed, and dead children nearby. An official report was sent to President Theodore Roosevelt, who in turn congratulated General Wood asking him to covey his thanks to the U.S. Troops for upholding the honour of the Stars & Stripes.