The Monthly Newsletter of the Bays Mountain Astronomy Club · and the birds start to chatter. When...

Transcript of The Monthly Newsletter of the Bays Mountain Astronomy Club · and the birds start to chatter. When...

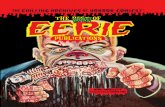

The Monthly Newsletter of the

BaysMountain AstronomyClub

Edited by Adam Thanz M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 1

Decem

ber 2016

Chapter 1

Looking Up

B r a n d o n S t ro u p e - B M A C C h a i r

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 2

Hello BMACers,

December is here. The last month of the year. 2016 is nearly to a close. This year feels like it has just flown by. I hope everyone had a great Thanksgiving. Christmas will be here before we know it. Did anyone ask Santa for a new telescope, a new mount, or even perhaps a new camera for your telescope? It is always nice to cap off the year with new equipment. We have had a lot of good events this year. We have had great speakers, intriguing presentations, and wonderful conversations. StarFest 2016 was an awesome event. I would like to thank all of you for all the help you have given this year to make everything a success. I plan on next year to be as good or even better than this year has been. And hopefully 2017 will provide us with much better weather for gazing at the heavens. As for the rest of this year, I hope we will have some good, clear weather to finish it off.

For our final meeting this year, I want everyone to welcome Dennis Hands. Dennis is an active observational astronomer. He taught astronomy and a few other subjects in the Greensboro City Schools. After his retirement, he made presentations to school groups at the Greensboro Natural Science Center for

several years. Dennis currently serves as the chair of the Advisory Committee for Cline Observatory at Guilford Technical Community College and has been teaching astronomy at High Point University since 2008. He’s been a member of the Greensboro Astronomy Club since 1985. Dennis lives in Greensboro with his wife Barbara.

Dennis’s presentation will be titled, “How Far Away Are the Stars?” Since antiquity we’ve wondered about the stars. What are they made of? How far away are they? When asked today about the distances, it’s easy to say that Proxima Centauri is almost 13 trillion miles away. We point our telescopes at M31 and tell our guests that the Andromeda Galaxy is almost 3 million light years away. But how do we know? Dennis will take us on a journey through time to remember how we learned the distances to the stars. Beginning with Aristotle and Hipparchus we’ll rediscover the methods used to determine one of the most basic features of the night sky: How far away are the stars?

I am very excited about Dennis’s presentation. I hope everyone will make it a point to be there. Please invite your friends, family, and co-workers. I would love to “pack the house” for Mr. Hands

Brandon Stroupe

Looking Up

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 3

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

4 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Perseus the Hero

image from Stellarium

layout by Adam Thanz

and our last presentation for the year. I believe everyone will enjoy his talk. I will look forward to seeing everyone there.

At our November meeting, we welcomed Mark Marquette. Mark is one of our club members who has recently been able to visit some pretty cool places. His presentation was titled, “MarQ’s 2016 Space Places: From Odessa Meteor Crater to Surveyor 3’s Moon Scoop.” Mark spent the time taking us on a journey of the numerous places he has visited in the recent year during his retirement. He shared many pictures and stories from his travels. Some of the places that he visited included Odessa Meteor Crater, McDonald Observatory, Cosmosphere in Kansas, and the Texas Star Party. He visited many more museums and observatories. I think we all were a little jealous of what he is being able to do. Thank you, Mark, once again, for your great presentation.

Our constellation this month is Perseus. Perseus is named after the Greek mythological hero Perseus. It is one of the 48 listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. In Greek mythology, Perseus was the son of Zeus and Danaë, He was a hero to the Greeks because he slayed Medusa and rescued his future wife Andromeda for being sacrificed to Cetus the sea monster. Perseus and Andromeda had six children. One of the well-known deep-sky objects in this constellation are the two open clusters NGC 869 and NGC 884, better known as the Double Cluster. Many of us have seen them through our telescopes more than

once. Another deep-sky object is M76, which is a planetary nebula, also called the Little Dumbbell Nebula. There are many more objects in Perseus that would be worth looking at if you so desire. Probably the most notable thing about Perseus is its famous Perseids meteor shower. They are a prominent annual meteor shower that appear to radiate from Perseus from mid-July, peaking in activity between August 9 and 14 each year. This meteor shower has been observed for about 2,000 years.

That will be it for this month. Just a reminder that the StarWatches finish at the end of November. They will begin again in March 2017 along with the SunWatches. I want to thank everyone that came out to help with the StarWatches. We couldn’t have done it without you. We look forward to next year when they start back up. Also, please mark your calendars for our upcoming annual dinner. The date will be January 14th and the snow date will be January 21st. The location will be announced at our meeting this month. Until next month… Clear Skies.

5 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Chapter 2

BMACNotes

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 4

Appalachian Eclipse 2017Witness one of nature’s most exciting, and rarest, celestial events - a total solar eclipse! The next one to occur will be on August 21, 2017.

The goal is to travel to the narrow path of totality as it stretches across the continental United States. The Bays Mountain Park Association is proud to announce an exclusive excursion to enjoy this experience. To do so, you need to be one of the 112 very lucky few who pre-register, with payment, to attend this special adventure.

A total solar eclipse is when the Moon travels between the Earth and Sun. The viewer, if on a narrow path, will see the Sun fully obscured to reveal the faint, tenuous Corona. Totality typically only lasts a few minutes or so. A brief, fleeting of time.

Our event boasts privacy, safety, and quietness. The reason is important. There is much that occurs in the natural world during a total solar eclipse. The temperature drops, the wind picks up, and the birds start to chatter. When totality approaches, it

becomes a false twilight. The lighting becomes quite eerie as the Sun’s light reaches us indirectly from all sides as we become bathed in the Moon’s shadow. The birds, and wind, quite down. There is more to experience, and you should, on our excursion.

This trip includes: motor coach ride to the astronomical site and back, private access to PARI (the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute), a special tour of PARI, snacks, lunch, and exceptional dinner, unique t-shirt, solar glasses, access to telescopes with solar filters, hosted by degreed astronomers, and more!

Not only are there only 112 seats available on our trip, but PARI is limiting access to their site so as to not overload their facility. They will have guarded gates for safety. Our group will have a private corner of their campus including our own bathrooms, water access, and air conditioning. PARI is an astronomical marvel with an amazing history in America’s space program. There are lots of details, so please visit the Park’s website here:

http://www.baysmountain.com/plan-your-visit/special-events-at-bays-mountain-park-planetarium/appalachian-eclipse-2017/

----------------------

BMAC News

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 7

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

Appalachia Dark Sky SurveyAppalachia's dark skies are an important national and regional resource. The University of Tennessee and the Appalachian Regional Commission are working to help protect and promote the region's night sky destinations. As part of this effort, we want to learn more about the people who visit these places.

We have designed a brief survey to help us learn more about visitors to dark sky sites and their travel preferences. We are sending the survey to dark sky stakeholders throughout the region, including local astronomy groups. Please feel free to share this survey with your members and other enthusiasts.

The survey is anonymous and no personal information about participants will be collected or shared. No one will contact you afterwards and you will not be placed on any distribution or mailing lists. Information collected from the survey will be used to help improve and protect dark sky destinations in the Appalachian region. The survey should take less than 10 minutes.

Here is a link to the online survey:

https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/AppalachianDarkSkies

Thank you for your participation.

Tim Ezzell, Ph.D.Research Scientist, Political Science DepartmentUniversity of Tennessee

8 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Chapter 3

Celestial Happenings

J a s o n D o r f m a n

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 5

Despite the media hype, last month’s Super Moon was quite a sight! If you don’t know what I’m talking about - just 2.5 hrs before the full Moon on the 14th of last month, the Moon was at perigee, it’s closest approach to Earth. This is the closest the Moon has been to Earth, during full Moon, since 1948. Now, even though there is only a 7% difference between the size of the Moon from apogee to perigee, the clear skies that we have been experiencing lately contributed to some excellent views of the full Moon. I thought it looked quite large and impressive.

Looking to the skies above this month, we continue to have good opportunities to view the planets and there are two meteor showers, the Geminids and Ursids. The skies have been quite clear over the last two months. We had a record number of nights at the observatories for our StarWatch program. Though the fires breaking out around the state show the desperate need for some rain, I’m hoping for some more clear skies as we approach the better seeing conditions of winter. The winter skies contain some of my favorite constellations. As I write this, the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus is already visible in the east after sunset. Orion and the beautiful Orion Nebula, M42, rise around 9

p.m. this month. About an hour later, we find Canis Major and the brightest star in the sky, Sirius.

At the end of November, we saw Mercury return to our evening skies. Look for it low in the southwest at dusk. Mercury reaches it’s greatest elongation on the 10th when it will be 21 degrees from the Sun. A telescope and an evening with good seeing will show you a gibbous disk that will be about 60% lit on the 14th. After the 17th, Mercury will move swiftly back towards the Sun becoming unobservable about the 19th.

Venus will continue to become more prominent in the evening sky as it rises higher and continues it’s trek closer to Mars. During December, Venus will shine at magnitude -4. In a telescope, it’s diameter will grow from 17” to 22” while the phase will decrease from 68% to 56% lit.

Mars continues to dim as it travels from Capricornus into Aquarius. From the 9th through the 13th, Mars and Venus will make shiny bookends to the squashed triangle of Capricornus. Keep an eye to the southwest during the first 5 days of the

Jason Dorfman

Celestial Happenings

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 10

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

month. A waxing crescent Moon will be making it’s way just above the ecliptic and the array of planets just described.

In the early morning skies, Jupiter can be seen in Virgo rising just before 3 a.m. at the beginning of the month and closer to 1 a.m. by the end. At almost magnitude -2, it will be quite bright as it continues it’s eastern movement towards Spica. On the 22nd, a waning crescent Moon will be seen above Jupiter forming an almost straight line with Jupiter and Spica and a small triangle on the next night as the Moon moves to the north of Spica. Saturn, the other gas giant planet in our Solar System, is moving into our morning skies by month’s end, as well. Saturn passes through superior conjunction on the 10th, so will not be visible for most of December. But, look for it rising an hour before sunrise starting Christmas morning.

Once again the full Moon will interfere with a prominent meteor shower this month. The Geminids peak on the night of December 13-14, which is also the night of the full Moon. However, the Geminids are often bright and colorful. With a predicted hourly rate of 120, there’s a good chance that you will see a few bright ones despite the Moon’s glow. You’ll have to be patient, though. A better opportunity this month are the often neglected Ursids that peak on the night of December 21-22. Though the predicted rate is quite low at 10 per hour, outbursts have been reported that exceeded 25 per hour. The shower’s radiant is near Kochab at the bowl of the Little Dipper. Perhaps it’s the cold weather, the close

date to Christmas or the Geminids stealing the show, but the Ursids are very poorly observed. Meteor scientist really want more data! If you’re interested in learning the standardized methods for taking meteor counts and reporting it in, check out www.imo.net/visual.

11 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Chapter 4

TheQueenSpeaks

R o b i n B y r n e

This month we celebrate the birthday of a man whose contributions to astronomy are as varied as they are important, and who also happens to share a birthday with me. Walter Sydney Adams was born December 20, 1876 in either Syria or Turkey, depending on which source you look at. His parents, Lucien and Nancy, were missionaries, so it’s possible they had lived in both places. When Walter was eight years old, the family moved back to the United States.

Adams’ formal education included high school in Vermont, first at St. Johnsbury Academy, and then the Phillips Academy, from which he graduated in 1894. His college education began at Dartmouth College, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Astronomy in 1898. One of his professors, Edwin Frost, was moving on to Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin and invited Walter to join him. Adams did, and his work earned him a Masters of Science in Astronomy from the University of Chicago in 1900. Adams than spent a year at the University of Munich in Germany until he was invited by George Ellery Hale to work as his assistant at Yerkes Observatory. For the next three years, Adams worked at Yerkes, where he was most interested in

measuring the radial velocities of stars. In 1904, Hale invited Adams to join him at the new Mount Wilson Observatory in California.

At Mount Wilson, Adams began as Hale’s deputy, but rose through the ranks to become the director of the observatory in 1923. Adams held that position for 23 years. One of his tasks at Mount Wilson was to oversee the establishment of the solar observatory, which was first used in 1912. Adams was also integral to the development of the 100 inch Hooker telescope, which saw first light in 1917.

When Adams first arrived at Mount Wilson, the 60 inch telescope was still under construction, so he made due with other equipment that was available. One of the first objects he studied was the Sun. Using photographs of the Sun, Adams was able to accurately measure the rotation rate of the Sun at different solar latitudes. Because the Sun is gaseous, it does not rotate as a solid body, but, instead, rotates faster at the equator than at the poles. This differential rotation had been known, but Adams was able to provide much more quantified measurements of the different rates. Adams also used spectroscopy to study

Robin Byrne

Happy Birthday Walter Sydney Adams

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 13

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

14 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Walter Sydney Adams

Image from http://

www.phys-astro.sonom

a.edu/brucemedalists/adams/index.html

sunspots. Working with Hale, they found that sunspots are cooler than the surrounding regions of the Sun, but have much stronger magnetic fields. Adams also studied the convection currents that occur just below the Sun’s “surface.”

In 1910, Adams married Lilliam Wickham. Sadly, she died less than 10 years after the wedding. Two years after losing Lilliam, Adams married Adeline Miller with whom he had two sons: Edmund and John.

The 60 inch telescope was completed in 1908, and Adams quickly used it for his passion of spectroscopy, which he described as “the only fun I have.” At first, Adams busied himself measuring the radial velocities of hundreds of stars and the spectra of novae. In 1915, Adams began investigating the companion star of Sirius, Sirius B. He was able to determine both the size and luminosity of this star. Adams found that it was not much bigger than Earth in size, yet the amount of light given off per unit area was brighter than the Sun, and the mass was similar to the Sun! He had measured the characteristics of the first known white dwarf star.

Working with Arnold Kohlschütter, they investigated F, G and K stars with known parallaxes, hence known distances. Knowing the distances, they were able to determine the absolute magnitudes of the stars. This allowed them to determine which of the stars were main sequence, and which were giants. Adams and Kohlschütter then compared the spectra of the stars. They

found that the intensity and width of spectral lines correlated to the star’s absolute magnitude. This could then be used to measure distances to stars too far to measure their parallax. With the start of World War I, Kohlschütter had to return to Europe. Adams continued with their work on his own, now incorporating B, A and M stars.

In 1925, Arthur Eddington was presenting at the International Astronomical Union’s meeting in Cambridge, England. His talk was about relativity. During his presentation, Eddington dropped a bombshell: that morning he received a telegram from Adams. Adams was able to measure the gravitational redshift of light coming from Sirius B. Eddington had predicted that the redshift should be 20 km/s. Adams measured a value of 19 km/s - a very strong confirmation of general relativity theory.

Later in his career, Adams continued with his love of spectroscopy, but now studying something other than stars. Looking at the spectra coming from interstellar gas clouds, Adams found spectral lines indicating the presence of cyanide (CN) and the hydrocarbon methylidyne (CH). Then Adams turned to the planets. With Theodore Dunham, they looked at the spectrum of Venus’ atmosphere and found that it was composed of carbon dioxide. In 1941, Adams looked at the spectrum of the atmosphere of Mars, in particular, looking for evidence of water vapor and oxygen. He found no traces of either, which led Adams to conclude that there was no life on Mars. Not too surprising,

15 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

16 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Walter Sydney

Adams is seen in the back left amongst

some prominent figures in

physics: A. A.

Michelson, Walther Mayer, Albert

Einstein, Max

Ferrrand, & Robert A. Millikan, Caltech,

1931.

Image from http://

www.phys-astro.sonom

a.edu/brucemedalists/adams/index.html

that discovery made headlines.

In 1946, Adams retired, but he hardly stopped working. He continued conducting research at the Hale Solar Laboratory in Pasadena. He even played a role in the development of the 200 inch Hale telescope at the Mount Palomar Observatory. Adams continued doing research until his death on May 11, 1956 at the age of 79. Walter Adams not only was an exceptional research scientist, he also had a knack for explaining astronomy to the general public. For many decades, whenever space was in the news, odds are that the story included a quote from Adams. For someone who made so many important contributions to astronomy, it’s a shame his name isn’t better known. Whether you prefer looking at planets, like Venus and Mars, or stars or interstellar nebulae, the next time you gaze up at the heavens, take a moment to remember the man who helped us better understand it all - Walter Sydney Adams.

References:

Walter Sydney Adams - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Sydney_Adams

Walter Adams - biography.com

http://www.biography.com/people/walter-adams-9176170

Walter Adams American Astronomer - britannica.com

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Walter-Adams

Walter Sydney Adams 1928 Bruce Medalist

http://www.phys-astro.sonoma.edu/brucemedalists/adams/index.html

Walter S. Adams - NNDB

http://www.nndb.com/people/789/000141366/

Obituary: Walter S. Adams, 1876 - 1956; Stratton, F. J. M.

The Observatory, Vol. 76, p. 139-140 (1956)

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1956Obs....76..139S

17 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Chapter 5

Space Place

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 6

Boasting intricate patterns and translucent colors, planetary nebulae are among the most beautiful sights in the Universe. How they got their shapes is complicated, but astronomers think they’ve solved part of the mystery—with giant blobs of plasma shooting through space at half a million miles per hour.

Planetary nebulae are shells of gas and dust blown off from a dying, giant star. Most nebulae aren’t spherical, but can have multiple lobes extending from opposite sides—possibly generated by powerful jets erupting from the star.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers discovered blobs of plasma that could form some of these lobes. “We’re quite excited about this,” says Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Nobody has really been able to come up with a good argument for why we have multipolar nebulae.”

Sahai and his team discovered blobs launching from a red giant star 1,200 light years away, called V Hydrae. The plasma is 17,000 degrees Fahrenheit and spans 40 astronomical units—roughly the distance between the Sun and Pluto. The blobs don’t erupt continuously, but once every 8.5 years.

The launching pad of these blobs, the researchers propose, is a smaller, unseen star orbiting V Hydrae. The highly elliptical orbit brings the companion star through the outer layers of the red giant at closest approach. The companion’s gravity pulls plasma from the red giant. The material settles into a disk as it spirals into the companion star, whose magnetic field channels the plasma out from its poles, hurling it into space. This happens once per orbit—every 8.5 years—at closest approach.

When the red giant exhausts its fuel, it will shrink and get very hot, producing ultraviolet radiation that will excite the shell of gas blown off from it in the past. This shell, with cavities carved in it by the cannon-balls that continue to be launched every 8.5 years, will thus become visible as a beautiful bipolar or multipolar planetary nebula.

The astronomers also discovered that the companion’s disk appears to wobble, flinging the cannonballs in one direction during one orbit, and a slightly different one in the next. As a result, every other orbit, the flying blobs block starlight from the red giant, which explains why V Hydrae dims every 17 years. For decades, amateur astronomers have been monitoring this variability, making V Hydrae one of the most well-studied stars.

Marcus Woo

Dimming Stars, Erupting Plasma, and Beautiful Nebulae

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 19

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

20 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 8

Because the star fires plasma in the same few directions repeatedly, the blobs would create multiple lobes in the nebula—and a pretty sight for future astronomers.

If you’d like to teach kids about how our sun compares to other stars, please visit the NASA Space Place: http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/sun-compare/en/

This article is provided by NASA Space Place.

With articles, activities, crafts, games, and lesson plans, NASA Space Place encourages everyone to get excited about science and technology. Visit spaceplace.nasa.gov to explore space and Earth science!

This four-panel graphic illustrates how the binary-star system V Hydrae is launching balls of plasma into space. Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI

21 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

Chapter 6

BMAC

Calendar

and more

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 7

BMAC Calendar and more

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 23

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

Date Time Location Notes

B M A C M e e t i n g sB M A C M e e t i n g sB M A C M e e t i n g sB M A C M e e t i n g s

Friday, December 2, 2016 7 p.m. Nature CenterDiscovery Theater Program: Dennis Hands, High Point University – “How Far Away Are the Stars?”; Free.

Friday, February 3, 2017 7 p.m. Nature CenterDiscovery Theater Program: Topic TBA; Free.

Friday, March 3, 2017 7 p.m. Nature CenterDiscovery Theater Program: Topic TBA; Free.

S u n W a t c hS u n W a t c hS u n W a t c hS u n W a t c h

Every Saturday & SundayMarch - October

3-3:30 p.m. if clear At the dam View the Sun safely with a white-light view if clear.; Free.

S t a r W a t c hS t a r W a t c hS t a r W a t c hS t a r W a t c h

Oct. 22, 29, Nov. 5, 2016 7:00 p.m.Observatory View the night sky with large telescopes. If poor weather, an alternate live tour of the night sky will be held in the

planetarium theater.; Free.November 12, 19, 26, 2016 6:00 p.m.

Observatory View the night sky with large telescopes. If poor weather, an alternate live tour of the night sky will be held in the planetarium theater.; Free.

S p e c i a l E v e n t sS p e c i a l E v e n t sS p e c i a l E v e n t sS p e c i a l E v e n t s

Saturday, January 14, 2017 6:30 p.m. ? Annual BMAC Dinner. Topic, date and place TBA. Jan. 21 is the snow date.

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club

853 Bays Mountain Park Road

Kingsport, TN 37650

1 (423) 229-9447

www.baysmountain.com

Annual Dues:

Dues are supplemented by the Bays Mountain Park Association and volunteerism by the club. As such, our dues can be kept at a very low cost.

$16 /person/year

$6 /additional family member

Note: if you are a Park Association member (which incurs an additional fee), then a 50% reduction in BMAC dues are applied.

The club’s website can be found here:

www.baysmountain.com/astronomy/astronomy-club/

Regular Contributors:

Brandon Stroupe

Brandon is the current chair of the club. He is a photographer for his home business,

Broader Horizons Photography and an avid astrophotographer. He has been a member

since 2007.

Robin Byrne

Robin has been writing the science history column since 1992 and was chair in 1997.

She is an Associate Professor of Astronomy & Physics at Northeast State

Community College (NSCC).

Jason Dorfman

Jason works as a planetarium creative and technical genius at Bays Mountain Park.

He has been a member since 2006.

Adam Thanz

Adam has been the Editor for all but a number of months since 1992. He is the

Planetarium Director at Bays Mountain Park as well as an astronomy adjunct for

NSCC.

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 24

Footnotes:1. The Rite of SpringOf the countless equinoxes Saturn has seen since the birth of the solar system, this one, captured here in a mosaic of light and dark, is the first witnessed up close by an emissary from Earth … none other than our faithful robotic explorer, Cassini.Seen from our planet, the view of Saturn’s rings during equinox is extremely foreshortened and limited. But in orbit around Saturn, Cassini had no such problems. From 20 degrees above the ring plane, Cassini’s wide angle camera shot 75 exposures in succession for this mosaic showing Saturn, its rings, and a few of its moons a day and a half after exact Saturn equinox, when the sun’s disk was exactly overhead at the planet’s equator.The novel illumination geometry that accompanies equinox lowers the sun’s angle to the ring plane, significantly darkens the rings, and causes out-of-plane structures to look anomalously bright and to cast shadows across the rings. These scenes are possible only during the few months before and after Saturn’s equinox which occurs only once in about 15 Earth years. Before and after equinox, Cassini’s cameras have spotted not only the predictable shadows of some of Saturn’s moons (see PIA11657), but also the shadows of newly revealed vertical structures in the rings themselves (see PIA11665).Also at equinox, the shadows of the planet’s expansive rings are compressed into a single, narrow band cast onto the planet as seen in this mosaic. (For an earlier view of the rings’ wide shadows draped high on the northern hemisphere, see PIA09793.)The images comprising the mosaic, taken over about eight hours, were extensively processed before being joined together. First, each was re-projected into the same viewing geometry and then digitally processed to make the image “joints” seamless and to remove lens flares, radially extended bright artifacts resulting from light being scattered within the camera optics.At this time so close to equinox, illumination of the rings by sunlight reflected off the planet vastly dominates any meager sunlight falling on the rings. Hence, the half of the rings on the left illuminated by planetshine is, before processing, much brighter than the half of the rings on the right. On the right, it is only the vertically extended parts of the rings that catch any substantial sunlight.With no enhancement, the rings would be essentially invisible in this mosaic. To improve their visibility, the dark (right) half of the rings has been brightened relative to the brighter (left) half by a factor of three, and then the whole ring system has been brightened by a factor of 20 relative to the planet. So the dark half of the rings is 60 times brighter, and the bright half 20 times brighter, than they would have appeared if the entire system, planet included, could have been captured in a single image.The moon Janus (179 kilometers, 111 miles across) is on the lower left of this image. Epimetheus (113 kilometers, 70 miles across) appears near the middle bottom. Pandora (81 kilometers, 50

miles across) orbits outside the rings on the right of the image. The small moon Atlas (30 kilometers, 19 miles across) orbits inside the thin F ring on the right of the image. The brightnesses of all the moons, relative to the planet, have been enhanced between 30 and 60 times to make them more easily visible. Other bright specks are background stars. Spokes -- ghostly radial markings on the B ring -- are visible on the right of the image.This view looks toward the northern side of the rings from about 20 degrees above the ring plane.The images were taken on Aug. 12, 2009, beginning about 1.25 days after exact equinox, using the red, green and blue spectral filters of the wide angle camera and were combined to create this natural color view. The images were obtained at a distance of approximately 847,000 kilometers (526,000 miles) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 74 degrees. Image scale is 50 kilometers (31 miles) per pixel.The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.Image Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

2. Duke on the Craters EdgeAstronaut Charles M. Duke Jr., Lunar Module pilot of the Apollo 16 mission, is photographed collecting lunar samples at Station no. 1 during the first Apollo 16 extravehicular activity at the Descartes landing site. This picture, looking eastward, was taken by Astronaut John W. Young, commander. Duke is standing at the rim of Plum crater, which is 40 meters in diameter and 10 meters deep. The parked Lunar Roving Vehicle can be seen in the left background.Image AS16-114-18423Creator/Photographer: NASA John W. Young

3. The Cat's Eye Nebula, one of the first planetary nebulae discovered, also has one of the most complex forms known to this kind of nebula. Eleven rings, or shells, of gas make up the Cat's Eye.Credit: NASA, ESA, HEIC, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)Acknowledgment: R. Corradi (Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes, Spain) and Z. Tsvetanov (NASA)

4. Jupiter & Ganymede

Footnotes

Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016 25

M o re o n t h i s i m a g e .

S e e F N 3

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has caught Jupiter's moon Ganymede playing a game of "peek-a-boo." In this crisp Hubble image, Ganymede is shown just before it ducks behind the giant planet.Ganymede completes an orbit around Jupiter every seven days. Because Ganymede's orbit is tilted nearly edge-on to Earth, it routinely can be seen passing in front of and disappearing behind its giant host, only to reemerge later.Composed of rock and ice, Ganymede is the largest moon in our solar system. It is even larger than the planet Mercury. But Ganymede looks like a dirty snowball next to Jupiter, the largest planet in our solar system. Jupiter is so big that only part of its Southern Hemisphere can be seen in this image.Hubble's view is so sharp that astronomers can see features on Ganymede's surface, most notably the white impact crater, Tros, and its system of rays, bright streaks of material blasted from the crater. Tros and its ray system are roughly the width of Arizona.The image also shows Jupiter's Great Red Spot, the large eye-shaped feature at upper left. A storm the size of two Earths, the Great Red Spot has been raging for more than 300 years. Hubble's sharp view of the gas giant planet also reveals the texture of the clouds in the Jovian atmosphere as well as various other storms and vortices.Astronomers use these images to study Jupiter's upper atmosphere. As Ganymede passes behind the giant planet, it reflects sunlight, which then passes through Jupiter's atmosphere. Imprinted on that light is information about the gas giant's atmosphere, which yields clues about the properties of Jupiter's high-altitude haze above the cloud tops.This color image was made from three images taken on April 9, 2007, with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 in red, green, and blue filters. The image shows Jupiter and Ganymede in close to natural colors.Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Karkoschka (University of Arizona)

5. 47 TucanaeIn the first attempt to systematically search for "extrasolar" planets far beyond our local stellar neighborhood, astronomers probed the heart of a distant globular star cluster and were surprised to come up with a score of "zero".To the fascination and puzzlement of planet-searching astronomers, the results offer a sobering counterpoint to the flurry of planet discoveries announced over the previous months."This could be the first tantalizing evidence that conditions for planet formation and evolution may be fundamentally different elsewhere in the galaxy," says Mario Livio of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, MD.The bold and innovative observation pushed NASA Hubble Space Telescope's capabilities to its limits, simultaneously scanning for small changes in the light from 35,000 stars in the globular star cluster 47 Tucanae, located 15,000 light-years (4 kiloparsecs) away in the southern constellation Tucana.Hubble researchers caution that the finding must be tempered by the fact that some astronomers always considered the ancient globular cluster an unlikely abode for planets for a variety of reasons. Specifically, the cluster has a deficiency of heavier elements that may be needed for building planets. If this is the case, then planets may have formed later in the universe's evolution, when stars were richer in heavier elements. Correspondingly, life as we know it may have appeared later rather than sooner in the universe.Another caveat is that Hubble searched for a specific type of planet called a "hot Jupiter," which is considered an oddball among some planet experts. The results do not rule out the possibility that 47 Tucanae could contain normal solar systems like ours, which Hubble could not have detected.

But even if that's the case, the "null" result implies there is still something fundamentally different between the way planets are made in our own neighborhood and how they are made in the cluster.Hubble couldn't directly view the planets, but instead employed a powerful search technique where the telescope measures the slight dimming of a star due to the passage of a planet in front of it, an event called a transit. The planet would have to be a bit larger than Jupiter to block enough light — about one percent — to be measurable by Hubble; Earth-like planets are too small.However, an outside observer would have to watch our Sun for as long as 12 years before ever having a chance of seeing Jupiter briefly transit the Sun's face. The Hubble observation was capable of only catching those planetary transits that happen every few days. This would happen if the planet were in an orbit less than 1/20 Earth's distance from the Sun, placing it even closer to the star than the scorched planet Mercury — hence the name "hot Jupiter."Why expect to find such a weird planet in the first place?Based on radial-velocity surveys from ground-based telescopes, which measure the slight wobble in a star due to the small tug of an unseen companion, astronomers have found nine hot Jupiters in our local stellar neighborhood. Statistically this means one percent of all stars should have such planets. It's estimated that the orbits of 10 percent of these planets are tilted edge-on to Earth and so transit the face of their star.In 1999, the first observation of a transiting planet was made by ground-based telescopes. The planet, with a 3.5-day period, had previously been detected by radial-velocity surveys, but this was a unique, independent confirmation. In a separate program to study a planet in these revealing circumstances, Ron Gilliland (STScI) and lead investigator Tim Brown (National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO) demonstrated Hubble's exquisite ability to do precise photometry — the measurement of brightness and brightness changes in a star's light — by also looking at the planet. The Hubble data were so good they could look for evidence of rings or Earth-sized moons, if they existed.But to discover new planets by transits, Gilliland had to crowd a lot of stars into Hubble's narrow field of view. The ideal target was the magnificent southern globular star cluster 47 Tucanae, one of the closest clusters to Earth. Within a single Hubble picture Gilliland could observe 35,000 stars at once. Like making a time-lapse movie, he had to take sequential snapshots of the cluster, looking for a telltale dimming of a star and recording any light curve that would be the true signature of a planet.Based on statistics from a sampling of planets in our local stellar neighborhood, Gilliland and his co-investigators reasoned that 1 out of 1,000 stars in the globular cluster should have planets that transit once every few days. They predicted that Hubble should discover 17 hot Jupiter-class planets.To catch a planet in a several-day orbit, Gilliland had Hubble's "eagle eye" trained on the cluster for eight consecutive days. The result was the most data-intensive observation ever done by Hubble. STScI archived over 1,300 exposures during the observation. Gilliland and Brown sifted through the results and came up with 100 variable stars, some of them eclipsing binaries where the companion is a star and not a planet. But none of them had the characteristic light curve that would be the signature of an extrasolar planet.There are a variety of reasons the globular cluster environment may inhibit planet formation. 47 Tucanae is old and so is deficient in the heavier elements, which were formed later in the universe through the nucleosynthesis of heavier elements in the cores of first-generation stars. Planet surveys show that within 100 light-years of the Sun, heavy-element-rich stars are far more likely to harbor a hot Jupiter than heavy-element-poor stars. However, this is a chicken and egg puzzle because some theoreticians say that the heavy-element composition of a star may be enhanced after if it makes Jupiter-like planets and then swallows them as the planet orbit spirals into the star.

26 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016

The stars are so tightly compacted in the core of the cluster – being separated by 1/100th the distance between our Sun and the next nearest star — that gravitational tidal effects may strip nascent planets from their parent stars. Also, the high stellar density could disturb the subsequent migration of the planet inward, which parks the hot Jupiters close to the star.Another possibility is that a torrent of ultraviolet light from the earliest and biggest stars, which formed in the cluster billions of years ago may have boiled away fragile embryonic dust disks out of which planets would have formed.These results will be published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters in December. Follow-up observations are needed to determine whether it is the initial conditions associated with planet birth or subsequent influences on evolution in this heavy-element-poor, crowded environment that led to an absence of planets.Credits for Hubble image: NASA and Ron Gilliland (Space Telescope Science Institute)

6. Space Place is a fantastic source of scientific educational materials for children of all ages. Visit them at:http://spaceplace.nasa.gov

7. NGC 3982Though the universe is chock full of spiral-shaped galaxies, no two look exactly the same. This face-on spiral galaxy, called NGC 3982, is striking for its rich tapestry of star birth, along with its winding arms. The arms are lined with pink star-forming regions of glowing hydrogen, newborn blue star clusters, and obscuring dust lanes that provide the raw material for future generations of stars. The bright nucleus is home to an older population of stars, which grow ever more densely packed toward the center.NGC 3982 is located about 68 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major. The galaxy spans about 30,000 light-years, one-third of the size of our Milky Way galaxy. This color image is composed of exposures taken by the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2), the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), and the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3). The observations were taken between March 2000 and August 2009. The rich color range comes from the fact that the galaxy was photographed invisible and near-infrared light. Also used was a filter that isolates hydrogen emission that emanates from bright star-forming regions dotting the spiral arms.Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)Acknowledgment: A. Riess (STScI)

8. This four-panel graphic illustrates how the binary-star system V Hydrae is launching balls of plasma into space. Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI

27 Bays Mountain Astronomy Club Newsletter December 2016