THE INTERRUPTION OF TASKS: … INTERRUPTION OF TASKS: METHODOLOGICAL, FACTUAL, AND THEORETICAL...

Transcript of THE INTERRUPTION OF TASKS: … INTERRUPTION OF TASKS: METHODOLOGICAL, FACTUAL, AND THEORETICAL...

Psychological Bulletin1964, Vol. 62, No. 5, 309-322

THE INTERRUPTION OF TASKS:

METHODOLOGICAL, FACTUAL, AND THEORETICAL ISSUES 1

EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

Yale University

After describing the criterion scores which have been used to assess be-havior in the interrupted task paradigm (ITP), a summary of the re-search literature is presented. ITP as a source of data for evaluating thepsychoanalytic theory of repression is found not to allow for the sepa-ration of learning and retention effects, and so is not well suited to thestudy of repression. Similarly, the mediation-avoidance hypothesis makespredictions only concerning interrupted task recall and while it is par-tially consistent with indirect data, it has yet to receive direct experi-mental test. The need-achievement conception predicts interrupted taskrecall satisfactorily but is inapplicable to completed task recall or rela-tive recall scores. Finally ITP is considered as a source of data for adevelopmental conception of success-failure reactions, Repetition choicescores are found to be consistent with the developmental theory, butsome recall results are not.

In the interrupted task paradigm(ITP) the subject (5) is engaged in anumber of tasks some of which he isallowed to complete and some of whichare interrupted before he completesthem. Zeigarnik (1927) first introducedITP as a test of the prediction fromthe gestalt theory of motivation thatinterrupted tasks should be recalledmore frequently than completed tasks.Her findings supported this predictionand is known to this day as theZeigarnik effect. However, ITP encom-passes more than just the Zeigarnikeffect or even the recall of tasks. In thefirst place, the Zeigarnik effect is farfrom being the invariable result in ITP.Frequently, more completed than in-completed tasks are recalled (e.g., At-kinson, 1953). In the second place,measuring the relative recall of com-

1This paper is a revision of part of adissertation submitted in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the degree of Doctorof Philosophy at George Peabody College. Atthe time of this revision the author wassupported by Research Grant MH-06809from the National Institute of Mental Health,United States Public Health Service.

pleted and incompleted activities is notthe only way to assess behavior in ITP.For example, ITP may be assessed byhaving S choose which task he wouldlike to repeat (e.g., Rosenzweig, 1933,1945). Finally, and most important,ITP has assumed a much wider theoret-ical significance than just being a testof a derivation from gestalt theory.(The reader who is interested in ITP asa source of evidence for the differentialutility of gestalt and stimulus-responsetheory should see Osgood, 1951.) It hasbeen used to test the psychoanalytictheory of repression (Rosenzweig, 1938),a mediation-avoidance hypothesis ofpersonality functioning (Inglis, 1961),the achievement-motive conceptions ofMcClelland, Atkinson, Clark, and Lowell(1953), and a developmental theory ofsuccess-failure conceptualization (Crom-well, 1963). Indeed, ITP has becomeone of those instances in the history ofpsychology when a single technique hasbeen used to test several theoreticalissues. Therefore, the methodologicaland theoretical issues involved and the

309

310 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

factual findings with ITP deserveelucidation.

Because there has been a great dealof inconsistency and circularity in theinterpretation of findings with ITP(Alper, 1952; Glixman, 1948; Osgood,1951), this review first summarizes thefunctional relationships found with ITPand then considers the theoretical issueswhich have grown out of these findings.

ITP CRITERION SCORES

The empirical findings from ITP canmost readily be grasped by groupingthem according to criterion scores. Itwill subsequently be seen that such agrouping also clarifies the theoreticalissues. The criterion scores used in ITPstudies fall naturally into three groups.This grouping excludes studies whichhave used as their criterion scores eitherthe relative rate of spontaneous resump-tion of incompleted and completedtasks (Henle, 1942; Nowlis, 1941;Rickers-Ovsiankina, 1937) or attractive-ness ratings (Cartwright, 1942; Geb-hardt, 1948) because there are so fewof them and because the factors whichdetermine spontaneous resumption seemso numerous and so poorly understood.

One group of criterion scores whichis concerned with recall of ITP taskskeeps the recall of incompleted (I) andcompleted (C) tasks separate. Thus,the measures are the number of I or Ctasks recalled (IR and CR, respec-tively) .

A second group of ITP criterionscores which is also concerned with taskrecall includes only those measureswhich reflect the relative recall of I andC tasks taken together. This group in-cludes the various recall differences andrecall ratio scores. The recall differencescores are: IR-CR, CR-IR, and CR/C-IR/I. The recall ratio scores are:

IR/CR, IR/I, and a variety of moreCR/C

complex and less interpretable ratios.The feature common to all relative

recall scores is that changes in themmay not be attributed to any particularchange in either IR or CR individually(Glixman, 1948). An increase in a dif-ference or ratio score may be due to:an increase in IR accompanied by nochange in CR, a decrease in CR ac-companied by no change in IR, an in-crease in IR accompanied by a decreasein CR, an increase in IR accompaniedby a smaller increase in CR, and adecrease in CR accompanied by asmaller decrease in IR. Likewise, theopposite of these five conditions canlead to a decrease in relative recallscore. Therefore, either an increase ora decrease in a recall ratio or differencescore may reflect an increase, nochange, or a decrease in IR or CR in-dividually. Furthermore, a relative re-call score may remain constant evenwhen both IR and CR change. Forthese reasons, hypotheses concernedwith change in either IR or CR alonemust measure them directly rather thanby relative recall scores. Also, anytheoretical scheme which makes pre-dictions about only IR or CR cannotbe tested by a study which employsonly relative recall scores. Only when atheory makes predictions about rela-tive differences or ratios, or when itpredicts both IR and CR separately, isa relative recall score appropriate to it.Even then the analysis of preference isone which does not use a relative recallscore. The preferred procedure is to usecompletion-incompletion as a dimensionof the analysis. When completion-in-completion is used as a dimension of theanalysis no information about eitherCR or IR is lost. Consequently, anyrelative recall effects, which are mani-

INTERRUPTION OP TASKS 311

fested as interactions involving the com-pletion-incompletion dimension, are im-mediately interpretable. That is, CRand IR are not obscured in this pro-cedure as they are in the calculation ofrelative recall scores.

A third group of ITP criterion scoresis concerned with task repetition ratherthan task recall. Task repetition scoresare secured by requiring S to choose torepeat one member of a pair of tasks,one of which he has previously com-pleted and one of which he has previ-ously begun but not completed. In allbut two investigations of repetitionchoice (RC) to date (Butterfield, 1963;Stedman, 1962), Ss have been givenonly two tasks, one of which was com-pleted and one of which was interrupted.Consequently, the only score used tomeasure RC has been some indicationof whether S repeated the I or the Ctask. Therefore, no relative recall scores,such as ratios and differences, have beenemployed.

Investigators have typically usedeither recall or repetition-choice scoreswithout any consideration of the rela-tionships between the two classes ofcriterion scores. This fact reflects anastonishing lack of basic methodologicalwork with ITP. Despite the long his-tory of research with ITP, Butterfield(1963) was apparently the first toexamine the intercorrelations of thevarious criterion scores which it yields.Yet, knowledge of this kind is essentialif the literature is to be integrated.More crucially, there has apparentlybeen no systematic investigation of thereliability of the various ITP scores.

CORRELATES OF THE VARIOUS ITPCRITERION SCORES

IR and CR Taken Separately

A substantial portion of the experi-mentation with ITP has concerned the

effects of instructions administeredprior to task presentation. In practicallyall of these investigatons the instruc-tions have varied along a dimensionwhich Alper (1946) characterized astask versus ego orientation and whichInglis (1961) characterized as stressfulversus nonstressful. Under the ego orstress instruction, S is told that taskcompletion or incompletion is a measureof his ability or intelligence. Under thetask-oriented or nonstress instruction,5 is told that task completion or incom-pletion is of secondary importance andthat it has nothing to do with his abilityor intelligence. In the present articlethis instructional dimension is referredto as neither an ego versus task-orienta-tion nor a stressful versus nonstressfulcontinuum. It is referred to as a skillversus nonskill dimension because thislatter label emphasizes the nature ofthe instructions rather than S's hypo-thetical reaction to the instructions.

The most striking thing about thevarious findings on the effects of skillinstructions is their inconsistency. Skillinstructions have been shown to in-crease (Atkinson, 1953), to have noeffect upon (Alper, 19S7; Atkinson &Raphelson, 1956; Eriksen, 1952a; Ken-dler, 1949; Rosenzweig, 1943), and todecrease IR (Alper, 1946; Caron &Wallach, 1957; Eriksen, 1952b, 1954;Glixman, 1949; Smock, 1956). Similarlywith skill instructions, CR has beenshown to decrease (Alper, 1946; Caron6 Wallach, 1957; Kendler, 1949), toremain the same (Alper, 1957; Atkin-son, 1953, Atkinson & Raphelson, 1956;Eriksen, 1952b, 1954; Glixman, 1949;Rosenzweig, 1943; Smock, 1956), andto increase (Eriksen, 1952a).

Several studies suggest that the in-consistent findings concerning the ef-fects of skill instructions upon IR andCR, particularly upon IR, may be dueto differences in 5 variables between the

312 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

studies. Atkinson (1953) found thathigh need achievement (n Ach) 5s in-creased their recall of incompleted taskswhile low n Ach Ss decreased their re-call of incompleted tasks when instruc-tions were more skill oriented. Atkinsonand Raphelson (1956) found no dif-ferences between high and low n Ach5s under nonskill instructions. However,under skill instructions high n Ach 5srecalled more I tasks than low n Ach 5s.Atkinson and Raphelson also foundthat while there were no differences inhigh and low need affiliation 5s underskill instructions, high need affiliation5s recalled more I tasks under non-skill instructions than did low needaffiliation 5s. In these nonskill instruc-tions, 5 was told that he was helpingthe experimenter participating in ITP.Neither Atkinson nor Atkinson andRaphelson found any instruction—orpersonality—related differences in therecall of completed tasks. Caron andWallach (19S9) replicated Atkinsonand Raphelson's findings concerning IRand n Ach, even though they used asubstantially different measure of n Ach.In addition, however, Caron and Wal-lach found that while high n Ach 5s'recall of completed tasks was unaffectedby skill instructions, low n Ach 5s re-called fewer completed tasks under skillthan nonskill instructions. Eriksen(1954) found that 5s who were highon the MMPI psychasthenia recalledmore I tasks under skill instructionsthan 5s who were low on that scale,and that 5s who were high on theMMPI hysteria scale recalled fewer Itasks under skill instructions than 5slow on that scale. Eriksen found nopersonality-related differences in therecall of C tasks. Eriksen also foundthat 5s with ego strength, as inferredfrom high F+% on the Rorschach, re-called more I tasks under skill instruc-tions than low ego-strength 5s. Using

a different Rorschach measure of egostrength, Jourard (1954) found no re-lationship with IR or CR. Apparentlyhigh n Ach and strong-ego 5s respondto skill instructions by recalling more Itasks while n Ach and weak-ego 5srespond to skill instructions by recallingfewer I tasks. The trend for CR is lessclear. The degree of overlap in the nAch and ego-strength constructs re-mains in question.

Marrow (1938) investigated instruc-tions which did not vary along thetypical skill versus nonskill dimension.Some 5s were told task completion in-dicated success; others were told taskincompletion indicated failure. His re-sults clearly indicated that 5's interpre-tation of C and I, rather than C and Iper se, determined recall. Findings byMcKinney (1935) support this inter-pretation. Subsequent analysis of Mar-dow's data also indicated that IR andCR were both unaffected by telling 5during the course of ITP that he wasdoing very poorly on ITP as a whole.

The relationships of IR and CR tovariables other than instructional dif-ferences have also been investigated.For example, IR and CR are differentlyaffected by the passage of time. Martin(1940) found an increase in the recallof C tasks 2 days after task presenta-tion which was not present for I tasks.Pachuri (1935) found a similar in-crease 1 day after task presentation.After 2 weeks, however, Martin (1940)found that the reminiscence of C taskshad dissipated and that both IR andCR had decreased. Sanford and Risser(1948) found after both 2 weeks and4 months that CR had decreased sig-nificantly while IR had not changed.

Pachuri (1935) found that fatigue atthe time of task administration reducedIR but did not affect CR and thatfatigue at the time of recall affectedneither IR nor CR.

INTERRUPTION OF TASKS 313

Caron and Wallach (1957) found thatthe verbal cancellation or relief of skillinstructions subsequent to task recalldid not affect IR. Subjects who hadand 5s who had not had their skillinstructions relieved recalled the samenumber of I tasks, this being fewer thanthat of nonskill-instruction Ss.

Recall of I Relative to C Tasks

The experimental findings concerningthe relative recall of I and C tasks canbest be summarized under the followingfour headings: effects of instructions,effects of 5 variables, interaction of in-structions and 5 variables, and othervariables.

Effects of Instructions. The experi-mental literature unequivocally in-dicates that skill instructions increasethe ratio of C task recalled to I taskrecall (Alper, 1946; Eriksen, 19S2a,19S2b; Hays, 19S2; Kendler, 1949;Lewis, 1944; Lewis & Franklin, 1944;Rosenzweig, 1941, 1943; Smock, 1956).

Effects of S Variables. Rosenzweigand Sarason (1942) found that 5s whowere more suggestible and/or hypnotiz-able recalled relatively more C than Itasks while the opposite was true of5s who were less suggestible and hyp-notizable. In a related study Sarasonand Rosenzweig (1942) found, bymeans of ratings derived from ThematicApperception Test protocols, that those5s who recalled more C than I taskswere relatively high on need affiliationand need deference while those 5s whorecalled more I than C tasks were rela-tively high on need autonomy and onanxiety.

Tamkin (1957) found that underskill instructions more adult schizo-phrenics than adult normals recalledmore I than C tasks. Winder (1952)found that under skill instructions moreparanoid schizophrenics than nonpara-

noid schizophrenics recalled more Ithan C tasks.

Sanford (1946) and Rosenzweig andMason (1934) have investigated theeffects of mental age (MA) and chrono-logical age (CA) upon relative recall.Using skill instructions, crippled institu-tionalized 5s, and different numbers oftasks for different 5s, Rosenzweig andMason failed to find any clear relation-ship between either MA or CA and rel-ative recall. Nevertheless, they reportedan impression that as both MA and CAincreased the recall of C tasks increasedto the recall of I tasks. Stanford, on theother hand, used nonskill instructionswith slightly older, intellectually andphysically average children from thepublic schools. He found a clear increasein the recall of I relative to C tasks asa function of CA. Stanford's findings areprobably more general and reliablethan Rosenzweig and Mason's. Butter-field's (1963) findings are consistentwith this conclusion.

Interaction of Instruction and S Vari-ables. Instructions and 5 variables in-teract when relative recall scores areused as the criterion. Persons withstrong egos as measured by a compositeRorschach score (Eriksen, 1954) and aquestionnaire (Alper, 1957) recall rela-tively more I tasks under nonskill in-structions and relatively more C tasksunder skill instructions. Alper's strong-ego 5s have higher need recognition andneed dominance and react to failurewith more increased effort than do herweak-ego 5s (Alper, 1948). People withlow n Ach recall relatively more I tasksunder nonskill instructions and rela-tively more C tasks under skill instruc-tions (Atkinson, 1953; Atkinson &Raphelson, 1956; Caron & Wallach1957, 1959). People with weak egosand high n Ach recall relatively moreC tasks under nonskill instructions and

314 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

relatively more I tasks under skillinstructions.

Other Variables. Abel (1938) investi-gated the relationship of relative recallto the Schneider index of neurocircula-tory efficiency. The Schneider index issupposedly a measure of response tophysiological stress. Abel found that 5swho recalled more I tasks relative to Ctasks had significantly greater neuro-circulatory efficiency. Strother and Cook(1953) have shown that 5s with lowneurocirculatory efficiency respond tostress with a decrement in performance.Therefore, it may be that 5s who recallmore I than C tasks respond with lessdecrement in performance under stressthan do 5s who recall more C than Itasks. Bialer and Cromwell (1960) foundevidence which seems to support thesuggestion that 5s who recall more Ithan C tasks respond with less perform-ance decrement to stress than 5s whorecall more C than I tasks. They foundthat mentally retarded Ss who returnto incompleted tasks respond with agreater increase in rate of card sortingafter induced failure than do 5s whoreturn to completed tasks in ITPprocedure.

Hays (1952) found that the interpo-lation of an interesting task betweenthe ITP and recall caused 5s to recallrelatively fewer C tasks than when heinterpolated a boring task.

RC

The RC has been studied exclusivelywith children and has been most ex-tensively related to MA and CA. Bialer(1957), Bialer and Cromwell (I960),Butterfield (1963), Rosenzweig (1933,1945), and Spradlin (1955-60) haveshown that as both MA and CA in-crease more Ss choose to repeat I tasks.Crandall and Rabson (1960) have madesimilar findings for boys but not for

girls. Bialer (1960) has found by usingaverage and mentally retarded Ss thatthis increasing tendency to choose I in-stead of C tasks under skill instructionsis due solely to increase in MA. It is un-related to increases in CA when MA ispartialed out. Miller (1961) found thatRC of the I task varies with MA andnot with CA when ITP is administeredunder skill instructions but not un-der nonskill instructions. Bialer (1957,1960), Bialer and Cromwell (1960),Butterfield (1963), Rosenzweig (1933,1945), Spradlin (1955-66), and Cran-dall and Rabson (1960) all used skillinstructions so that Miller's (1961) find-ings are consistent with theirs. Miller'sfailure to find a relationship betweenRC and MA under nonskill conditionsmay be due to the fact that practicallyall of his Ss chose the I task under non-skill conditions. Consequently, there wasno possibility of his finding any differ-ential relationship between the choice ofI and C tasks.

A number of apparently similar per-sonality variables have been related toRC behavior. Subjects who return to Irather than C tasks have been rated byteachers as more rebellious (Miller,1961) and as having more pride (Rosen-zweig, 1933) and by observers of theirfree-play activity as being more as-sertive and independent (Crandall &Rabson, 1960). Bialer (1960) foundthat Ss who reported in questionnaireitems that they feel personal controlover what happens to them more oftenrepeat I tasks than Ss who report feel-ings of more external control. It is pos-sible that none of these relationshipswould have been found if MA had beencontrolled. For example, Bialer's (1960)finding was eliminated when MA wascontrolled statistically.

In the only study to investigate theeffects of different instructions uponRC, Miller (1961) found that skill

INTERRUPTION OF TASKS 315

instructions increased the tendency toreturn to C rather than I tasks.

THEORETICAL ISSUESThe ITP has been considered to pro-

vide validity measures for the psycho-analytic theory of repression, the media-tion-avoidance hypothesis of personalityfunctioning, the McClelland and hisassociates' (1953) conception of achieve-ment motivation, and a developmentaltheory of success-failure conceptualiza-tion. Its role in each of these fourtheoretical realms is considered in turn.

Repression

Rosenzweig (1938) originated the ra-tionale for deriving a measure of re-pression from ITP. He reasoned thatskill instructions would make I tasksseem like failure to the 5s, therebycausing them to repress the I tasks.Therefore, 5s would recall fewer I tasksunder skill instructions than under non-skill instructions. Rosenszweig derivedno predictions from psychoanalytictheory about the effects of skill instruc-tions upon C tasks and no such deriva-tion seems possible.

Rosenzweig found that the ratio of Itasks to C tasks was less under skillthan under nonskill conditions. How-ever, Rosenzweig suggested, and Glix-man (1948) subsequently establishedby reanalyzing Rosenzweig's data, thatthis relative change was due to an in-crease in CR rather than to the pre-dicted decrease in IR. Other investi-gators have also failed to find anyconsistent effects of skilled instructionsupon IR when 5s were unselected forpersonality variables (Alper, 1946,1957; Atkinson, 1953; Atkinson &Raphelson, 1956; Caron & Wallach,1957; Eriksen, 1952a, 1952b, 1954;Glixman, 1949; Kendler, 1949). When5s were selected for personality vari-ables,' skill instructions increased the IR

of 5s high in n Ach and MMPI psych-asthenia and decreased the IR of 5s lowin n Ach and high in MMPI hysteria.Therefore, if a decrease in IR due toskill instructions is indeed repression,repression occurs markedly more oftenin some personalities than in others.This is as might be expected. Further-more, other personalities actually showthe opposite of repression—call it ob-session (Caron & Wallach, 1959)—totask interruption under skill conditions.

While it is conceivable that some 5sshould react to interruption under skillinstructions by repressing the I taskand others by becoming obsessed withthe I task, there is a good reason todoubt that changes in IR due to skillinstructions have demonstrated eitherrepression or obsession. While the pres-ent argument is made solely for thephenomenon of repression, it also ap-plies to obsession. It is said to occurwhen some experience has been regis-tered, that is, learned but because ofsome painful association has beenwarded off from recall. In order todemonstrate repression, it is first neces-sary to demonstrate that two groupshave learned some response equally welland then to show that some painfulexperience leads one group to recall thatresponse significantly less well. That is,it is necessary to be able to separate theeffects of learning from the effects ofretention upon recall. In ITP, it is im-possible to show that the groups to becompared on retention are equal onoriginal learning. For an example of astudy which separates the effects oflearning and retention by placing therepression-inducing stimulus after a testfor initial learning see Zeller (1952).This inability to show that I and Ctasks are equally well learned is acrucial shortcoming of ITP as a meas-ure of retention since the original learn-ing opportunity is frequently shorter

316 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

for I than for C tasks. Since ITP doesnot allow for the separation of learningfrom retention it is not well suited tothe study of repression. Nevertheless,indirect attempts have been made todetermine whether differential recall ofI tasks was a phenomenon of learningor of retention.

Theoretically, repressed materialshould not be subject to the same lawsof retention as unrepressed material aslong as the reason for the repressionexists. In ITP, the ostensible reasonfor repression is S's reaction to hisbelief that task incompletion is due tohis lack of skill. Therefore, until theskill instructions are somehow counter-manded and S "realizes" that task in-completion is unrelated to his skillful-ness, IR should not change overtime the way CR does. However, thereshould be no differences in changes overtime between IR and CR when thetasks are presented under nonskill in-structions. As was reported earlier,Martin (1940), Pachuri (193S), andSanford and Risser (1946) found dif-ferences between changes in IR andchanges in CR, but these differencesoccurred under both skill and nonskillinstructions. Therefore, these differ-ences establish neither that decreasesin IR are due to retention, that is,repression, nor that they are due tooriginal learning.

Caron and Wallach (19S9) theorizedthat, since the ostensible reason forrepression in ITP is S's reaction to hisbelief that task incompletion is due tohis lack of skill, they could determinewhether differential recall was due tolearning or retention by comparing therecall of three groups: nonskill instruc-tions, skill instructions, and skill instruc-tions which were countermanded be-tween the time of task presentation andtask recall. If the countermanded skill-instruction group was similar to the

nonskill group, then the effect would beone of retention. If the countermandedskill group was similar to the skillgroup and different from the nonskillgroup, then the effect would be one oforiginal learning. Their results sug-gested that differences were probablydue to differences in original learning.

Pachuri's (193S) finding that fatigueat the time of task administration af-fects IR while fatigue at the time oftask recall does not, also suggests thatdepressed recall is due to differencesin learning rather than differences inretention.

In summary, both logical considera-tion and research findings with ITPsuggest that, as it has been used in thepast, it is not well suited to the study ofrepression.

Mediation-A voidance Hypothesis

Inglis (1961) attempted to integratethe results of ITP studies by meansof the mediation-avoidance hypothesis.According to this hypothesis, Ss reactto moderate amounts of "socializedanxiety" by avoiding the mediator orinstigator of that anxiety. Smallamounts of anxiety are said to haveno influence upon avoidance behaviorand large amounts are said to be dis-ruptive of avoidance behavior. Inother words, the mediation-avoidancehypothesis postulates a curvilinear rela-tionship between anxiety and avoid-ance. Furthermore, there are said to betwo sources of socialized anxiety: S'simmediate environment and his person-ality. The environment ranges fromnonstressful to stressful situations insuch a way that task interruption underskill instructions is more stressful thantask interruption under nonskill instruc-tions. The personality factors which aresaid to be related to socialized anxietyare the dimensions of stability to neu-roticism and introversion to extraversion.

INTERRUPTION OF TASKS 317

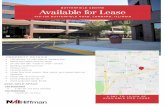

Neurotic extraverts are least suscepti-ble, neurotic introverts are most sus-ceptible, and stable introverts andstable extraverts are intermediately sus-ceptible to stress. Since, accordingto the mediation-avoidance hypothesis,there is a curvilinear relationship be-tween anxiety and avoidance, and sinceanxiety is contributed to by both theenvironment and S's personality, themediation-avoidance hypothesis predictsan interaction in the production ofavoidance reactions between personalityand situational stress (see Figure 1).

From these premises of the mediation-avoidance theory the present author hasderived the following predictions.

1. Under conditions of low stress,introverts recall fewer I tasks thanextraverts.

2. Under conditions of high stress,introverts recall more I tasks thanextraverts.

3. If both the introverts and extra-verts are neurotic the differences pre-dicted in Hypotheses 1 and 2 above aregreater than if the groups are unselectedfor neuroticism.

4. Under similar instructional condi-tions, there are no mean differencesbetween neurotic and stable groupswhich are equal on or unselected forintroversion-extraversion.

5. Under similar instructional condi-tions, the variance is greater and thedistribution of avoidance scores is morebimodal for neurotic than for stablegroups when the groups are equal onextraversion-introversion.

6. The effects of stress instructionsupon IR are unpredictable withoutknowledge of S's personality.

These predictions refer only to therecall of interrupted tasks becauseaccording to Inglis (1961, p. 280) Itasks are the only "anxiety-producingmediators" in ITP. Therefore, since

STRESS

NE SE SI Nl NE SE SI Nl

SUSCEPTIBILITY TO STRESS

NE - Neurotic extroversionSE - Stable ext rovers ionSI - Stable introversionNl - Neurotic introversion

FIG. 1. Hypothetical relationship betweensusceptibility to stress and avoidance reactions(adapted from Inglis, 1961).

changes in relative recall scores dependupon changes in both IR and CR, rela-tive recall scores do not provide adefinitive test of the validity of themediation-avoidance hypothesis. Conse-quently, Inglis' (1961) discussion ofITP in which he relied entirely uponrelative recall scores is inconclusivewith regard to the mediation-avoidancehypothesis and his conclusion that ITPstudies confirm the mediation-avoidancehypothesis is questionable if not er-roneous.

There are no studies in the literaturewhich test directly the predictionsmade from the mediation-avoidancehypothesis. However, some indirecttests have been made. For example, ifit is assumed, as Inglis does, that highn Ach is an index of neurotic extra-version, then the findings of Atkinson(19S3), Atkinson and Raphelson(19S6), and Caron and Wallach (1959)support Hypotheses 1 and 2 above.Since Hypotheses 1 and 2 taken to-gether constitute the prediction of an

318 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

interaction between instructional and Svariables, the mediation-avoidance hy-pothesis predicts some of the mostcomplex ITP phenomena. Hypothesis 3has not been tested even indirectly.If it is assumed, as Inglis does, thatEriksen's (1954) measure of egostrength is a valid index of neuroticism,then Hypothesis 4 has been contra-dicted and Hypothesis 5 has receivedno support. The author's conclusionthat Hypothesis 4 has been contra-dicted differs from Inglis' interpreta-tion of the evidence. Inglis concludedthat a study by Eriksen (1954) sup-ported the mediation-avoidance hy-pothesis when it would not have doneso even if a relative recall score wasan appropriate criterion score withwhich to test the hypothesis. Inglisnoted that Eriksen measured egostrength "partly by a Rorschach con-formity score not unlike that found byEysenck to be a fairly good measure ofneuroticism." He concluded from thefact that Eriksen's ego-strength meas-ure was positively related to relativerecall scores under nonstress conditionsand negatively related to relative recallscores under stress conditions that themediation-avoidance hypothesis was up-held. It is clear from Inglis' diagrams(see Figure 1), however, that neuroti-cism independent of extraversion-intro-version is predicted to be unrelated todirectional differences in avoidance.That is, Eriksen's finding of a direc-tional relationship between neuroticismand relative recall is contrary to ratherthan supportive of the derivation fromthe mediation-avoidance hypothesis.Hypothesis 6 has been supported by thelack of consistency in the results ofstudies examining the effects of skillinstructions upon IR.

It is apparent that while the media-tion-avoidance hypothesis is relevantto the recall of I tasks, much more

research is needed before it can beasserted that it adequately summarizesor predicts even the existing findingswith ITP.

Achievement Motivation

In order to predict ITP findings fromn Ach scores it has been assumed thatdifferences in n Ach indicate qualitativedifferences in motive structure ratherthan, or in addition to, differences inintensity of motivation (McClelland,1951; McClelland et al., 1953). Spe-cifically, it has been assumed that per-sons with high n Ach scores are moti-vated primarily by a need to approachsucccess while persons with moderate orlow n Ach scores are motivated primarilyby a fear of, or a need to, avoid failure.Furthermore, skill instructions are as-sumed to enhance the motivationswhich the person possesses. That is, forlow or moderate need achievers, skillinstructions are said to be threateningand to lead to increased avoidance offailures, that is, I tasks "since recall offailures would serve to redintegrate thepain of failure [McClelland et al.,1953]." On the other hand, for highneed achievers, skill instructions are saidto be an incentive or challenge whichleads to increased approach to, or recallof, I tasks. It is as if the high needachiever "wanted to continue to striveto complete them [McClelland, et al.,1953]." These predictions about theinteractive effects of instructions andn Ach on IR are supported by the ex-perimental literature.

As it was developed by McClellandand his associates (1951, 1953), theachievement-motive conception makesno predictions about the recall of Ctasks. Therefore, it cannot predict theinteractive effects of instructions andn Ach upon relative recall scores with-out the addition of factually unwar-ranted assumptions. It would be neces-

INTERRUPTION OF TASKS 319

sary to assume that neither n Ach norskill instructions affect CR. While it istrue that n Ach is unrelated to CR,instructions do affect it. Consequently,without the addition of some specifica-tion of conditions under which instruc-tions affect CR, achievement-motivetheory is concerned with only the rela-tionship between IR and n Ach.

Success-Failure Conceptualization

While theorists who were interestedin repression, the mediation-avoidancehypothesis, and achievement motivationhave used task recall measures as theircriterion scores, theorists who wereinterested in success and failure con-ceptualization and developmental vari-ables have used task RC.

These latter theorists (Bialer, 1960;Cromwell, 1963) have based their pre-dictions about RC on developmentalhypotheses such as the following:

From the time of birth the child isassumed to respond to stimuli aspleasant or unpleasant and to learn toapproach stimuli previously associatedwith pleasant events and to avoidstimuli previously associated with un-pleasant events. As the child maturesa second motivational and conceptualsystem is said to develop. This secondsystem is called the success-approachversus failure-avoidance system. As itmatures the child comes more and moreto conceptualize events in terms of hisown behavioral competence, that is,success and failure and less and lessin terms of pleasantness and unpleas-antness. In terms of the ITP situationin which the child is asked to repeatthe task of his choosing, this meansthat the older child will more oftenchoose to repeat the task which allowshim to demonstrate behavioral compe-tence. The younger child, on the otherhand, will more often choose the taskwhich gave him the greatest pleasure.

Since more behavioral competence canbe demonstrated by doing a more dif-ficult task, the older child will moreoften choose the more difficult task.Theoretically, the only clue to difficultyin the ITP situation is completion orincompletion, the I task appearing tobe more difficult. Therefore, the olderchild should more often return to theI task even though the C task was prob-ably the more pleasurable to him.The evidence strongly supports thisprediction.

This developmental viewpoint hasdifficulty predicting the relationship be-tween ITP behavior and instructionaland 5 variables. The predictions it doesmake all stem from a straightforwardand well-documented derivation fromthe notion of a developmental success-striving versus failure-avoiding motiva-tion system; namely, that as childrenmature they report more frequently andin a wider variety of situations thatthey feel control over what happens tothem (Bialer, 1960; McConnell, 1963;Miller, 1961). To the extent that thistendency to report oneself in control ofwhat happens to him is correlated withMA or CA, the increases in it are as-sociated with increasing resumption andrecall of I tasks. However, there issome evidence that the tendency toverbalize control is not solely dependentupon MA or CA and that increases inthe portion of verbalized control whichare independent of MA or CA are asso-ciated with increasing resumption of Ctasks (Bialer, 1960). These findingshave been interpreted (Butterfield,1963) to mean that the particular partof the variance in verbalized controlwhich is independent of MA is a meas-ure of the degree to which an individualstrives to avoid events at which he suc-ceeded in the past. This interpretationgives the developmental position two 5variables by which to predict ITP be-

320 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

havior: intellectual maturity and ver-balized control. As intellectual maturityincreases, the resumption or recall ofI tasks becomes more frequent. Asan individual verbalizes more controlover events without concomitant growthin intellectual maturity, the resumptionor recall of C tasks becomes morefrequent.

The verbalized control construct alsomakes it possible for the developmentaltheory to make predictions about theeffects of skill instructions. Accordingto the developmental position, the effectof skill instructions is the same as thatof S's verbalized control. That is, skillinstructions simply induce S to believethat he controls task completion. In-ternal control independent of MAleads to reduced resumption of I andincreased resumption of C tasks.

Virtually all of the data within therealm of task resumption are consistentwith the developmental theory outlinedabove. However, it does not predict themore thoroughly studied task recall phe-nomena as well. Skill instructions donot always decrease the recall of I tasksand increase the recall of C tasks asthe developmental theory predicts.Furthermore, the developmental theorydoes not include variables with knownrelationships to many of the 5 variableswhich have been shown to interact withthe various ITP scores. For example,it can make no predictions about theeffects of n Ach. Therefore, it is notapplicable to some of the most reliableand orderly findings with ITP. How-ever, the developmental position doespredict the fact that skill instructionsalways decrease the recall of I tasksto the recall of C tasks and vice versa.This is a distinct difference between itand the other theoretical schemes con-sidered here. The reason the develop-mental scheme predicts the effects ofskill instructions upon relative recall

scores is that, unlike all of the otherpositions here considered, it makes pre-dictions about both IR and CR. Conse-quently, relative recall scores are asrelevant to the development positionas are scores which keep IR and CRseparate.

CONCLUSION

It is apparent that none of the sys-tematic attempts to deal with ITP phe-nomena has adequately accounted forall of the known relationships. How-ever, these theoretical efforts and theliterature upon which they are basedclearly indicate that any adequate ex-planation of ITP phenomena musttake into account: instructions, person-ality variables, developmental level ofthe subject, and probably task variables.

REFERENCES

ABEL, THEODORA M. Neurocirculatory reac-tion and the recall of unfinished and com-pleted tasks. /. Psychol., 1938, 6, 377-383.

ALPER, THELMA G. Memory for completedand incompleted tasks as a function of per-sonality: An analysis of group data. /.abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1946, 41, 403-420.

ALPER, THELMA G. Memory for completedand incompleted tasks as a function ofpersonality: Correlation between experi-mental and personality data. J. Pers., 1948,17, 104-137.

ALPER, THELMA G. The interrupted taskmethod in studies of selective recall: Are-evaluation of some experiments. Psychol.Rev., 19S2, 59, 71-88.

ALPER, THELMA G. Predicting the directionof selective recall; its relation to egostrength and N achievement. /. abnorm.soc. Psychol., 1957, 55, 149-165.

ATKINSON, J. W. The achievement motiveand recall of interrupted and completedtasks. J. exp. Psychol, 1953, 46, 381-390.

ATKINSON, J. W., & RAPHELSON, A. C. Indi-vidual differences in motivation and behav-ior in particular situations. /. Pers., 1956,24, 349-363.

BIALER, I. Differential task recall in mentaldefectives as a function of consistency inself-labeling. Unpublished master's thesis,George Peabody College for Teachers, 1957.

INTERRUPTION OF TASKS 321

BIALER, I. Conceptualization of success andfailure in the mentally retarded and nor-mal children. Ann Arbor, Mich.: UniversityMicrofilms, 1960. (Also, in brief, /. Pers.,1961, 29, 303-320.)

BIALER, I., & CROMWELL, R. L. Task repeti-tion in mental defectives as a function ofchronological and mental age. Amer. J.ment. Defic., 1960, 65, 265-268.

BUTTERFIELD, E. C. Task recall and repetitionchoice as a function of locus of controlcomponents, mental age, and skill vs. non-skill instructions. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Uni-versity Microfilms, 1963.

CARON, A. J., & WALLACE, M. A. Recall ofinterrupted tasks under stress: A phe-nomena of memory or learning? /. abnorm.soc. Psychol, 1957, 55, 372-381.

CARON, A. J., & WALLACE, M. A. Personalitydeterminants of repressive and obsessive re-actions to failure stress. J. abnorm. soc.Psychol., 1959, 59, 236-245.

CARTWRIGHT, D. The effect of interruption,completion, and failure upon the attrac-tiveness of activities. J. exp, Psychol., 1942,31, 1-16.

CRANDALL, V., & RABSON, ALICE. Children'srepetition choices in an intellectual achieve-ment situation following success and failure./. genet. Psychol, I960, 97, 161-168.

CROMWELL, R. L. A social learning approachto mental retardation. In N. R. Ellis (Ed.),Handbook of mental retardation. NewYork: McGraw-Hill, 1963.

ERIKSEN, C. W. Defense against ego threatin memory and perception, /. abnorm. soc.Psychol, 1952, 47, 231-236. (a)

ERIKSEN, C. W. Individual differences in de-fensive forgetting. J. exp. Psychol, 1952,44, 442^43. (b)

ERIKSEN, C. W. Psychological defenses and"ego strength" in recall of completed andincompleted tasks. /. abnorm. soc. Psychol,1954, 49, 45-50.

GEBHARDT, M. E. The effect of success andfailure upon the attractiveness of activitiesas a function of experience, expectation,and need. /. exp. Psychol, 1948, 38, 371-388.

GLIXMAN, A. F. An analysis of the use of theinterruption technique in experimentalstudies of "repression." Psychol Bull, 1948,45, 491-506.

GLIXMAN, A. F. Recall of completed andincompleted activities under varying degreesof stress. /. exp. Psychol, 1949, 39, 281-295.

HAYS, D. G. Situational instructions and taskorder in recall for completed and inter-

rupted tasks. J. exp. Psychol, 1952, 44,434-437.

HENLE, M. An experimental investigation ofthe dynamic and structural determinants ofsubstitution. Contr. psychol Theory, 1942,2(3).

INGLIS, J. Abnormalities of motivation and"ego-functions." In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.),Handbook of abnormal psychology. NewYork: Basic Books, 1961.

JOURARD, S. M. Ego strength and the recall oftasks. /. abnorm. soc. Psychol, 1954, 49,51-58.

KENDLER, TRACY. The effect of success andfailure on the recall of tasks. /. gen.Psychol, 1949, 41, 79-87.

LEWIS, A. B., & FRANKLIN, M. An experi-mental study of the role of the ego inwork: II. The significance of task orienta-tion in work. /. exp. Psychol, 1944, 34,195-215.

LEWIS, H. B. An experimental study of therole of the ego in cooperative work. /. exp.Psychol, 1944, 34, 113-126.

MCCLELLAND, D. C. Personality. New York:Sloane, 1951.

MCCLELLAND, D. C., ATKINSON, J. W., Clark,R. A., & Lowell, E. L. The achievementmotive. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1953.

McCoNNELL, T. R. Suggestibility in childrenas a function of chronological age. /.abnorm. soc. Psychol, 1963, 67, 286-290.

McKiNNEY, F. Studies in the retention ofinterrupted learning activities. /. camp.Psychol, 1935, 19, 265-296.

MARROW, A. J. Goal tensions and recall. Part2. /. gen. Psychol., 1938, 19, 37-64.

MARTIN, J. R. Reminiscence and gestalttheory. Psychol. Monogr., 1940, 52, 1-37.

MILLER, M. B. "Rebelliousness" and repetitionchoice of a puzzle task under relativeautonomy and control conditions in adoles-cent retardates. Amer. J. ment. Defic., 1961,66, 428-434.

NOWLIS, H. H. The influence of success andfailure on the resumption of an interruptedtask. J. exp. Psychol, 1941, 28, 304-325.

OSGOOD, C. E. Method and theory in experi-mental psychology. New York: OxfordUniver. Press, 1951. Pp. 578-587.

PACHURI, A. R. A study of gestalt problemscompleted and interrupted tasks. Brit. J.Psychol, 1935, 25, 365-381, 447-457.

RiCKERS-OvsiANKiNA, MARIA. Studies on thepersonality structure of schizophrenic in-dividuals: II. Reaction to interrupted tasks.J. gen. Psychol, 1937, 16, 179-196.

322 EARL C. BUTTERFIELD

ROSENZWEIG, E. The experimental study ofrepression. In H. Murray (Ed.), Explora-tions in personality. New York: OxfordUniver. Press, 1938. Pp. 422-491.

ROSENZWEIO, S. Preferences in the repetition ofsuccessful and unsuccessful activities asa function of age and personality. /. genet.Psychol., 1933, 42, 423-440.

ROSENZWEIG, S. Need-persistive and ego-defensive reactions to frustration as demon-strated by an experiment on repression.Psychol. Rev., 1941, 48, 347-349.

ROSENZWEIG, S. An experimental study of"repression" with special reference to need-persistence and ego-defensive reactions tofrustration. /. exp. Psychol., 1943, 32, 64-74.

ROSENZWEIG, S. Further comparative data onrepetition choice after success and failure asrelated to frustration tolerance. J. genet.Psychol., 194S, 66, 75-81.

ROSENZWEIG, S., & MASON, G. A. An experi-mental study in memory in relation to thetheory of repression. Brit. J, Psychol., 1934,24, 247-265.

ROSENZWEIG, S., & SARASON, S. An experi-mental study of the triadic hypothesis:Reaction to frustration, ego-defense, andhypnotizability. II. Correlational approach.Charact. Pers., 1942, 11, 1-19.

SANFOKD, N., & RISSER, J. What are the con-ditions of self-defensive forgetting? /. Pers.,1948, 17, 244-260.

SANFORD, R. N. Age as a factor in the recallof interrupted tasks. Psychol. Rev., 1946,S3, 234-240.

SARASON, S., & ROSENZWEIG, S. An experi-mental study of the triadic hypothesis: II.Thematic apperception approach. Chart.Pers., 1942, 11, 150-165.

SMOCK, C. D. Recall of interrupted and non-interrupted tasks as a function of experi-mentally induced anxiety and motivationalrelevance of the task stimuli. /. Pers.,1956, 25, 589-599.

SPRADLIN, J. Task resumption phenomena inmentally retarded Negro children. Abstr.Peabody Stud. went. Defic., 1955-60, 1, 40.

STEDMAN, D. J. Locus of control as a deter-minant of perceptual defense in mentallyretarded subjects, Ann Arbor, Mich.: Uni-versity Microfilms, 1962.

STROTHER, G. B., & COOK, D. M. Neurocircu-latory reactions and a group stress situation./. consult., Psychol., 1953, 17, 267-268.

TAMKIN, A. S. Selective recall in schizo-phrenia and its relation to ego strength.J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1957, 55, 345-349.

WINDER, C. L. On the personality structureof schizophrenics. /. abnorm. soc. Psychol.,1952, 47, 86-100.

ZEIGARNIK, B. Das Behalten erledigter andunerledigter Handlungen. In K. Lewin(Ed.), Untersuchungen zer Handlungs: UndAffectpsychologie. Psychol. Forsch., 1927, 9,1-85.

ZEIXER, A. F. An experimental analogue ofrepression: III. The effect of induced failureand success on memory measured by recall.J. exp. Psychol, 1952, 42, 32-38.

(Received January 2, 1964)