The Impact of Hotel Management Contracting on IHRM Practices_ Understanding the Bricks and Brains...

Transcript of The Impact of Hotel Management Contracting on IHRM Practices_ Understanding the Bricks and Brains...

The impact of hotel managementcontracting on IHRM practicesUnderstanding the bricks and brains split

Judie GannonOxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK

Angela RoperSchool of Management, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, and

Liz DohertyFaculty of Organisation and Management, Sheffield Hallam University,

Sheffield, UK

Abstract

Purpose – The international hotel industry’s growth has been achieved via the simultaneousdivestment of real estate portfolios and adoption of low risk or “asset light” market entry modes suchas management contracting. The management implications of these market entry mode decisions havehowever been poorly explored in the literature and the purpose of this paper is to address theseomissions.

Design/methodology/approach – Research was undertaken with senior human resourceexecutives and their teams across eight international hotel companies (IHCs). Data were collectedby means of semi-structured interviews, observations and the collection of company documentation.

Findings – The findings demonstrate that management contracts as “asset light” options forinternational market entry not only provide valuable equity and strategic opportunities but also limitIHCs’ chances of developing and sustaining human resource competitive advantage. Only wherecompanies leverage their specific market entry expertise and develop mutually supportiverelationships with their property-owning partners can the challenges of managing human resourcesin these complex and diversely owned arrangements be surmounted.

Research limitations/implications – A limitation of this paper is the focus on the human resourcespecialists’ perspectives of the impact of internationalization through asset light market entry modes.

Originality/value – This paper presents important insights into the tensions, practices andimplications of management contracts as market entry modes which create complexinter-organisational relationships subsequently shaping international human resource managementstrategies, practices and competitive advantage.

Keywords Market entry, Managers, Contracts of employment, Human resource management,International business

Paper type Research paper

IntroductionKey debates in the internationalisation of firms and industries have revolved aroundthe risks and returns of different market entry modes (Altinay, 2001; Brookes andRoper, 2008; Brown et al., 2003; Dunning and McQueen, 1982; Dunning and Kundu,1995; Erramilli et al., 2002; Zhao and Decker, 2004). Cultural and institutional externalfactors, as well as internal factors, have been recognised as critical to the success of

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0959-6119.htm

IJCHM22,5

638

Received 1 July 2009Revised 27 September 2009,21 November 2009Accepted 22 November 2009

International Journal ofContemporary HospitalityManagementVol. 22 No. 5, 2010pp. 638-658q Emerald Group Publishing Limited0959-6119DOI 10.1108/09596111011053783

international market entry decisions (Altinay, 2001; Chung and Enderwick, 2001).While the strategic and operational aspects of market entry mode choices have beenaddressed, there has been limited exploration of how international human resourcemanagement (IHRM) may be affected by decisions to enter international marketsthrough various ownership arrangements. This paper identifies how managementcontracts, as one of the main international expansion options available to internationalhotel companies (IHCs) (Bender et al., 2008; Whittaker, 2006), have shaped anindustry’s capacity to realise competitive advantage through their human resources.Known also the “bricks and brains” split the management contract mode allows hotelcompanies to separate their hotel operations from their real estate assets, and inviteother investors to undertake the property burden (Todd and Mather, 2001; Bender et al.,2008). In this paper, such strategic market entry mode decisions are explored in relationto the likelihood of further industry concentration and the challenges and opportunitiesfor developing HRM talent and effective people management practices.

Previous authors have argued that the hotel industry provides an interesting andvaluable setting for any exploration of HRM (Boxall, 2003; Hoque, 1999; Nickson, 2007).It is a sector which has experienced sustained growth, is a major employer andgenerates nearly US$500 billion revenue across the world (WTO, 2007). Across thehotel industry, the majority of properties are small (in terms of number of bedrooms)and independently owned; however, the international corporate sector is dominated byseveral major IHCs. These organisations, through their growth strategies, havedeveloped brand names and portfolios of several thousand hotel properties (Litteljohnet al., 2007). The success of these IHCs is dependent upon developing multiple andbroadly replicated properties across the world to ensure investor support and marketshare growth (Litteljohn, 2003; Litteljohn et al., 2007; Roper et al., 2001; Segal-Horn,2000; Whitla et al., 2007). These companies are also able to fuel their expansion byderiving economies of scale and scope over small, independent and typically domestichotel operators (Litteljohn, 2003; Roper et al., 2001).

Todd and Mather (1995, 2001) identify the impact of wider environmental changes,such as the recession and collapse of the property market in the USA as also forgingnew approaches to international hotel management. The proportion of high fixedinvestment costs and the prospect of separating the operation from the ownership ofassets, means hotel companies have a range of alternative expansion options availableto them (Altinay, 2001; Bender et al., 2008; Johnson, 1996; Litteljohn, 2003; Zhao andOlsen, 1997). The most common market entry modes include: exporting, strategicalliances, licensing, management contracting, franchising and foreign directinvestment (Graham, 2006). The nature of hotel services and importance of presencein key locations across the world also suggests that global brand recognitionnecessitates the involvement of investors with local knowledge and expertise (Altinay,2001; Brown et al., 2003; Erramilli et al., 2002; Whitla et al., 2007). The IHCs have tobalance the need for asset investment, local knowledge and expertise with the issues offlexibility and control in selecting specific market entry modes for their expandinghotel portfolios ( Johnson et al., 2005).

Litteljohn et al.’s (2007) analysis of hotel industry internationalization highlightsthat less attention has been paid to the management implications of market entry modechoices. Within the hotel industry, it is an adage that “a hotel is only as good as itsmanager” (Forte, 1986, p. 119) with companies’ successes depending upon the abilities

Hotelmanagement

contracting

639

and expertise of their unit managers. Such arguments identify the importance ofrelevant management development strategies and practices (D’Annunzio-Green, 2002,1997; Jones et al., 1998; Kriegl, 2000). The IHCs’ use of management contracts andpursuit of the “bricks and brains” split, implies an asset shift from real estate intohuman capital with clear implications for the effective management and developmentof managerial resources. As such, unit managers are seen as strategic human resourcesor “rainmakers” vital to companies’ pursuit of competitive advantage (Boxall andSteeneveld, 1999; Marchington et al., 2003). Yet, the human capital and human resourcepractice implications of not owning the hotel properties which the IHCs’ hotelmanagers operate have not been clearly accounted for under these corporate financearrangements. There is a limited body of research on companies’ experiences andapproaches to managing people, practices and policies across these permeableinternational organisational boundaries (Truss, 2004). Coupled with the call fromLitteljohn et al. (2007) for research on the management implications of choice of marketentry mode, the value of this study is clearly apparent.

This paper provides new empirical data on IHRM practices and offers freshtheoretical insights into the impact of market entry modes as inter-organisationalrelationships on IHRM. It reports directly on the ways corporate HRM executivesunderstand and manage the development and deployment of strategic humanresources in light of their organisations’ wider strategic market entry mode decisions.

The next section presents a review of the literature on management contracts. Thepaper then proceeds to explore the limited research on IHRM and market entry modedecisions. An evaluation of the present insights on IHRM in international jointventures (IJVs) is undertaken to indicate where gaps in understanding exist. Theresearch design deployed in the study is then outlined. Subsequently, the results arediscussed and analysed prior to the practical and theoretical implications for IHRMand specialist and operational managers being highlighted.

Management contractsAs international hotel brand expansion demands developing multiple units across theworld, equity investments can be seen to be a real constraint on companies’international aspirations (Whittaker, 2006). There are then clear benefits andopportunities for IHCs expansion to be “asset light” based upon three factors. First,stock markets’ reassessment of the risks and returns of hotel ownership by companies.Second, there is the renewed interest in hotel assets by private equity and real estatefunds. Finally, the difficulty of securing adequate market penetration with onlyinternal equity, given the sheer size and scale of international markets, is also evident(Slattery et al., 2008). Whilst IHCs may use a range of market entry options one of themost prominent is the management contract as commented by Guilding (2006, p. 402),“The ubiquity of the hotel management contract in Western economies can be viewedas a highly significant and differentiating aspect of the hotel industry.” Companiescontinued divestment of their “bricks from their brains” (real estate and managementoperations) has freed up capital to acquire close (and not so close) competitors andincrease shareholder value as well as strengthen their brands’ market share (Benderet al., 2008; Johnson, 2002; Litteljohn, 2003; Whittaker, 2006). In their generic form,management contracts are seen to be temporary with the long-term aim of encouraginghost country nationals (HCNs) to take over upon contract expiry (Hollensen, 2004;

IJCHM22,5

640

Stonehouse et al., 2000). In the hotel industry, management contracts are signed over thelonger term often with local investors who are unlikely to assume control of contractswhen they expire (Eyster, 1997). As Contractor and Kundu (1998, p. 329) identify:

A management service contract is a long-term agreement, of up to ten years or even longer,whereby the legal owners of the property and real estate enter into a contract with the hotelfirm to run and operate the hotel on a day to day basis, usually under the latter’sinternationally recognized brand name.

The local investor benefits from the brand name, technical expertise and managementsupport of the IHC. The IHC meanwhile receives a fee for these managerial services(usually a percentage of gross revenue), brand name presence in a foreign location andsome additional performance-based inducements (Bader and Lababedi, 2007; Beals,2006; Beals and Denton, 2004; Schlup, 2003). As such, key features of managementcontracts include (Brookes, 2007, p. 36):

[. . .] pre-opening and technical assistance, rights and duties concerning daily operations,budgets, owner’s/operator’s costs, central services, banking, accounting and reporting, feesand the term of the contract and termination.

There are advantages for IHCs in terms of control over corporate know-how throughday-to-day managerial control but the integral nature of the property in all hoteltransactions creates specific dilemmas (Eyster, 1997; Guilding, 2006; Whittaker, 2006).The division between hotel ownership and hotel operations in management contractsindicates that the participating parties have potentially conflicting interests not only ininvestment choices but also in ongoing management decisions (Bader and Lababedi,2007; Brookes and Roper, 2008; Beals, 2006; Eyster, 1997; Guilding, 2006; Panvisavasand Taylor, 2006). In addition, the owners and operators in international managementcontracts typically originate from different cultural and institutional backgrounds byvirtue of the need for IHCs to gain access to host country markets and local owners toacquire international hotel brand names and expertise (Altinay, 2001; Antel, 2005;Panvisavas and Taylor, 2006). As such, the domestic partner (owner) and foreignpartner (IHC) possess very different areas of expertise and use the partnership toleverage their knowledge and create competitive advantage. For example, the IHCprovides access to a global brand name, managerial know-how and reservationstechnology while the owner provides equity plus local knowledge of institutions,customer groups and the labour market (Magnini, 2008).

Recently, researchers (Beals, 2006; Brookes and Roper, 2008; Eyster, 1997; Schlup,2003; Whittaker, 2006) have argued that owners have become more influential, gettinginvolved in personnel and budgeting decision making. In addition many now alsodemand some limited equity investment from operators (Beals, 2006; Schlup, 2003;Whittaker, 2006). This increased involvement is apparent in Guilding’s (2006) study ofinvestment appraisal issues in management contract hotels where his respondents(hotel general managers (GMs) and other senior unit executives) identified the conceptof “ego-trip ownership”, or the “ostentatious desire to own a lavish hotel decorated withexpensive furniture and fittings.” (Guilding, 2006, p. 420). The management contract inthe international hotel industry therefore presents specific challenges due, not only tothe cultural and institutional differences between the owners and hotel operators, butalso the divergent interests arising from the real estate and operations split; so that,issues of control and flexibility remain significant.

Hotelmanagement

contracting

641

Internationalisation: IHRM and modes of market entryTruss (2004, p. 57) identifies there is little research on “the impact of external, orinter-organisational, relationships on HRM” this is despite the growing trends towardsmore diverse ownership arrangements, which result in more indistinguishableorganisational boundaries. Issues arising from these blurred boundaries include; whois covered by certain HRM practices, how implementation and enforcement aremanaged and where influences for HRM practices come from (Gardner, 2005; Truss,2004). Subsumed by the globalisation and localisation debates, the IHRM literatureemphasises the way macro institutional and cultural factors in the parent and hostcountries influence HRM practices (Harzing and Van Ruysseveldt, 2004, 1995;Rosenzweig, 2006) rather than diversity of ownership issues. Welch and Welch (1994)addressed how market entry modes impacted upon IHRM in an early study,specifically in relation to the need for different skills and corporate resources. Theyargued for a blend of long- and short-term assignments to subsidiaries dependent uponmodal choice and identified the importance of management socialisation. Theexpatriation literature (Bonache and Zarraga-Oberty, 2008; Caligiuri and Colakoglu,2007; Harzing and Van Ruysseveldt, 2004; Scullion and Collings, 2006) has alsohighlighted the pressures applied to international firms to localise management roles.

In the generic literature, management contracts are seen as market entry modeswith non-equity implications for companies; however, in the hotel industry, ownersoften demand some outlay from the hotel operator (Beals, 2006; Guilding, 2006). Thereis some research on the IHRM implications of IJVs but very little on managementcontracts as a form of IJVs, and IHRM. For example, Schuler et al. (2004) identify theimpact of IJVs on IHRM in relation to the inter-organisational relationships in firmsexpanding across national borders. Schuler and Tarique’s (2006) model explores IHRMand organizational issues in IJVs as partnerships form, exchange knowledge anddevelop learning processes, then implement and advance their business relationship,and finally reconcile issues of trust, conflict and control. However, the complexity ofmanaging diverse arrangements across multiple partners is crucial in the internationalhotel industry, and not addressed in this model (Harvey, 2007; Magnini, 2008).Furthermore, there is little discussion in the IJV literature of how companies influenceand develop their managerial expertise across considerable distances, and inpartnership with their local investors (the hotel owners). There is also limitedunderstanding of how operating international subsidiaries via diverse market entrymodes, alongside management contracts, impinges on the strategic development andmanagement of human resources. The idiosyncratic nature of IJVs, and particularlymanagement contracts in the hotel industry, suggests that caution is appropriateregarding the applicability of the IJV and IHRM literature (Magnini, 2008; Panvisavasand Taylor, 2006; Whitla et al., 2007).

In management contracts, IHCs are mainly focused upon leveraging theiroperational know-how and technologies to, from and between host countries (Brownet al., 2003; Erramilli et al., 2002). As a labour intensive industry the main route totransferring these capabilities and expertise is through human resources, specificallythe hotel managerial resources (Aung, 2000; Beals, 2006, 1995; Kriegl, 2000; Segal-Horn,2000). Where employees provide disproportionate value to their organisations they areoften recognized as strategic human resources or “rainmakers” (Boxall and Steeneveld,1999; Marchington et al., 2003). Boxall’s (1996, p. 67) original arguments on strategic

IJCHM22,5

642

human resources identified them as human capital advantage, accrued by employingpeople with specific skills, knowledge and abilities, who are “latent with productivepossibilities.” Likewise, international subsidiary managers, specifically expatriates,are identified as vital assets in the internationalisation and IHRM research (Barhamand Oates, 1991; Bonache and Zarraga-Oberty, 2008; Scullion, 1992; Scullion andCollings, 2006).

Research designIn order to capture the managerial deployment and development practices of IHCs withexpanding portfolios, a largely qualitative research design was employed (Bryman andBell, 2007; Robson, 2002, 1993). A purposive sampling technique (Bryman and Bell, 2007;Saunders et al., 2000) was utilised based upon identifying companies who had extensiveglobal hotel portfolios across five continents. An initial sample of 13 companies wasderived, but this reduced to nine due to concentration across the industry. Eight of thenine companies granted the main researcher access to their senior human resourceexecutives (typically vice-presidents of human resources), their support teams,administrative systems and archives to provide corporate insights into managerialdevelopment and deployment across the IHCs. This is in line with Scullion and Starkey’s(2000, p. 1065) argument that a key role for corporate HR is the management of those“identified as strategic human resources and seen as vital to the company’s future andsurvival.” The authors’ personal experiences of the international hotel industry alsoverified these individuals as responsible for the deployment and development of hotelmanagers. Access was negotiated and achieved via the researchers’ own networks ofindustry contacts and personal recommendations from other members of faculty. A proforma checklist was developed to aid with the collection of documentary evidence anddeployed alongside in-depth interviews conducted with the IHCs’ executives and theirteams (Bryman, 1992; Bryman and Bell, 2007; Robson, 2002, 1993; Silverman, 1999).

Each company was given a pseudonym, which masked their true origin and allmaterial collected had company names and trademarks removed to provideconfidentiality to respondents. Table I provides an overview of the IHCs concerned,their size, the service levels of the brands they operated and the market entry modesdeployed. Fieldwork took place mainly in Europe by visiting headquarters, regionaloffices and hotel units. The main interviews with the executives lasted on average fourhours and focused upon how they were developing the managerial talent to meet theirexpanding international portfolios. The executives’ interview responses and thecontent analysis of the IHCs’ documentation form the main focus of this paper.Documentation included: HRM policies, performance appraisal forms, organizationalcharts, training manuals, company newspapers, job descriptions and successionplanning charts, as well as demonstrations of technical systems such as talent bankdatabases. This helped to develop the context and depth of the research data (Bryman,1992; Bryman and Bell, 2007; Saunders et al., 2000).

The interview transcripts, observations and company documentation wereanalysed using manual and computer aided techniques (Miles and Huberman, 1994;Silverman, 1997, 1999). Initial coding identified specific HRM practices, managementcriteria and company strategies and market entry modes, and then followed bydescriptive coding focused upon processes and associations within the organisations.Further, interpretive coding and analytic coding directed at topics emerging from the

Hotelmanagement

contracting

643

IHC

sN

o.of

hot

els

Ser

vic

ele

vel

sof

bra

nd

sIn

tern

atio

nal

isat

ion

Met

hod

sof

gro

wth

Eu

rom

ult

igro

w2,

350

17h

otel

bra

nd

ssp

lit

into

thre

eg

rou

ps:

Up

scal

ean

dm

id-s

cale

Eco

nom

yan

dB

ud

get

Lei

sure

hot

els

73co

un

trie

sM

ixed

typ

eof

oper

atio

nis

use

dac

ross

por

tfol

io;

app

rox

imat

ely

,46

per

cen

tow

ned

,21

per

cen

tle

ased

,22

.5p

erce

nt

man

agem

ent

con

trac

tsan

d10

.5p

erce

nt

fran

chis

edF

ran

chis

eKin

g2,

100

Fiv

eb

ran

ds:

Ori

gin

alm

idm

ark

etb

ran

dP

rest

ige

bra

nd

Bu

dg

etb

ran

dM

id-m

ark

etb

ut

mor

elo

cali

sed

bra

nd

Hol

iday

reso

rtac

com

mod

atio

n

63co

un

trie

s“T

ob

eth

ep

refe

rred

hot

elsy

stem

,h

otel

man

agem

ent

com

pan

y,

and

lod

gin

gfr

anch

ise

inth

ew

orld

.T

ob

uil

don

the

stre

ng

thof

the

Fra

nch

iseK

ing

nam

eu

tili

sin

gq

ual

ity

and

con

sist

ency

asth

ev

ehic

leto

enh

ance

its

per

ceiv

ed‘v

alu

efo

rm

oney

’p

osit

ion

inth

em

idd

lem

ark

et.

To

max

imis

ed

istr

ibu

tion

thro

ug

hou

tth

ew

orld

by

agg

ress

ive

exp

ansi

onof

exis

tin

gan

dn

ewp

rod

uct

sth

rou

gh

own

ed,

man

aged

and

fran

chis

edd

evel

opm

ents

.”E

mp

loy

men

tli

tera

ture

Bri

tbu

yer

960

Nin

eb

ran

ds

atth

efo

llow

ing

lev

els:

Up

scal

eM

idm

ark

etB

ud

get

All

oper

atin

gin

tern

atio

nal

lyan

dd

omes

tica

lly

50co

un

trie

sO

ne-

thir

dof

pro

per

ties

are

own

edan

dtw

o-th

ird

sar

em

anag

emen

tco

ntr

act

arra

ng

emen

ts.

Gro

wth

thro

ug

hm

anag

emen

tco

ntr

acti

ng

,fr

anch

isin

gor

mar

ket

ing

agre

emen

tsan

dso

me

own

ersh

ipP

urc

has

eda

pre

miu

min

tern

atio

nal

Fre

nch

hot

elch

ain

in19

95an

dw

assu

bse

qu

entl

yp

urc

has

edit

self

by

aB

riti

shle

isu

reg

rou

pin

1997

US

mix

edec

onom

y(U

SM

E)

460

Pre

stig

eb

ran

dM

id-m

ark

etb

ran

d–

Nor

thA

mer

ica

63co

un

trie

sG

row

thth

rou

gh

man

agem

ent

con

trac

tin

gso

me

own

ersh

ipan

dfr

anch

isin

g.

Acq

uir

eda

pre

stig

iou

sE

uro

pea

nb

ran

din

the

earl

y19

90s

(continued

)

Table I.Profiles of the eight IHCs

IJCHM22,5

644

IHC

sN

o.of

hot

els

Ser

vic

ele

vel

sof

bra

nd

sIn

tern

atio

nal

isat

ion

Met

hod

sof

gro

wth

An

glo

-Am

eric

anP

rem

ium

180

incl

ud

esd

omes

tic

un

its

Pre

stig

ein

tern

atio

nal

bra

nd

Nat

ion

alU

Km

id-m

ark

etb

ran

d48

cou

ntr

ies

“An

glo

-Am

eric

anP

rem

ium

’sst

rate

gy

for

inte

rnat

ion

alg

row

this

toco

nti

nu

eit

sex

pan

sion

inp

rim

eci

tyce

ntr

ean

dre

sort

loca

tion

san

dd

evel

opcl

ust

ers

ofh

otel

sse

rvin

gin

div

idu

alco

un

trie

sor

reg

ion

s.T

he

stra

teg

yis

bei

ng

ach

iev

edth

rou

gh

aco

mb

inat

ion

ofn

egot

iati

ng

man

agem

ent

con

trac

tsto

run

hot

els

and

esta

bli

shin

gjo

int

ven

ture

sor

par

tner

ship

sw

ith

reg

ion

alor

nat

ion

alow

nin

gco

mp

anie

s.”

Con

trac

tman

Inte

rnat

ion

al20

2to

tal

wit

h68

inte

rnat

ion

alu

nit

sF

our

lux

ury

oru

psc

ale

bra

nd

s,d

epen

den

tu

pon

size

,le

ng

thof

stay

,an

dfa

cili

ties

35co

un

trie

sId

enti

fies

itse

lfas

anen

trep

ren

euri

al,

mar

ket

-dri

ven

com

pan

yw

ith

am

ult

icu

ltu

ral

app

roac

hto

hot

elm

anag

emen

t.It

gro

ws

sole

lyb

yse

curi

ng

man

agem

ent

con

trac

tag

reem

ents

wit

hse

lect

inv

esto

rsE

uro

alli

ance

51O

ne

up

scal

eb

ran

d16

cou

ntr

ies

stro

ng

Eu

rop

ean

reg

ion

alro

ots

Gro

wth

thro

ug

hm

anag

emen

tco

ntr

acti

ng

,ra

ther

than

own

ersh

ip,

and

ag

lob

alp

artn

ersh

ipw

ith

one

ofth

eA

mer

ica’

sla

rges

tin

tern

atio

nal

hot

elco

rpor

atio

ns

Glo

bal

alli

ance

190

hot

els

Pre

stig

eb

ran

dM

id-m

ark

etb

ran

d–

Nor

thA

mer

ica

70co

un

trie

sG

row

thth

rou

gh

man

agem

ent

con

trac

tin

g,

fran

chis

ing

orm

ark

etin

gag

reem

ents

and

som

eow

ner

ship

Table I.

Hotelmanagement

contracting

645

respondents and the theoretical relationships arising from the data and initial coding(Silverman, 1997, 1999). Of particular importance were the themes of similar anddistinctive HRM practices deployed by the companies, how the companies’characteristics (brands, market levels, size and market entry modes) influenced HRM,and the overall significance of developing management expertise. The subsequentsections examine how managerial resources are developed and managed in light of theIHCs widespread use of management contracts, before the conclusions and practitionerand research agendas are outlined.

Management contracts influence on deploying and developing hotelmanagersThe ways in which the “asset light” option of management contracts affects themanagement of hotel managers are captured in five emerging themes as follows: hotelmanagement talent, owner interference, global versus local management talent,developing future hotel GMs and the impact of multiple market entry modes.

Hotel management talentTable I confirms the wide scale use of management contracting, and reinforces theevidence from the literature of the popularity of this market entry mode (Bender et al.,2008; Todd and Mather, 2001). Specific issues regarding the ownership of managementtalent and its development, also emerge from the data. Each of the human resourceexecutives highlighted this particular market entry method as presenting challenges totalent development, deployment and transfer across hotel portfolios. The IHCs wereunable to control the movement and development of their managers thereby limitingthe advantages of this market entry mode. While hotel management contracts suggestcompanies compete on the basis of brand names and managerial expertise in operatinghotel services, these points are negated where property investors decree that “their”managers’ (and their expertise and knowledge) are not to be moved. Not all investorsparticipated in HRM decisions, with some owners acting as “sleeping partners” (purelyconcerned with the investment) refraining from involvement in their hotel’s day-to-dayoperations. Owner interference was more evident though in unit level seniormanagement appointments. While all the IHCs’ respondents complained to someextent about “interfering owners”, this issue was more prevalent when companies’portfolios were focused upon the luxury end of the market and was less evident whereheavily branded budget and mid-market hotels were concerned.

In terms of employer status, the IHCs, as part of their management contract, tookresponsibility for at least the GM and up to ten other executive members of staff,depending upon hotel size. However, exceptions occurred, for instance, where only theGM would be the employee of the IHC and all other staff were employed by the localowner. The issue of continuity of service became problematic where local legislationdid not permit managers to be employed by a foreign entity (the IHC). So although themanagers were employed by local investors, the IHCs sought to provide employmentcontinuity reassurances (evidenced by talent database notes and contracting memos).Without providing employment contract continuity, the HRM executives, andtheir teams argued it was difficult to get the “best” and most experienced staff torelocate to particular countries and hotel units. In other cases, management contracts

IJCHM22,5

646

were complicated by IHC investments as well. The HR executive from Franchisekingidentified:

There are several complex cases where because the unit is a management contract, butthrough a joint venture with Franchiseking as one arm of the partnership, the company(Franchiseking) does employ most of the staff but under another company name.

All the respondents agreed that manager transfers were vital to company success, aswell as to managers’ own careers, and establishing clear agreement with owners wascritical. Most companies aimed to move managers after two/three years, though thiswas dependent upon a number of factors. Globalalliance felt it was much easier totransfer younger managers while established GMs were only likely to move where themanager themselves saw a more prestigious unit was on offer. The executive fromBritbuyer commented on some owners’ approach to management transfers:

Once you put their ideal people in there you can forget about them as it will be difficult to getthem out. It is a problem. The best way to handle it is to agree everything up front. Theyknow then it is a two-year assignment and that is as far as it will go. It can be managed wellbut there are occasional problems.

The length of management assignments was complicated by the challenges of certainglobal locations. Known in the expatriate literature as “hardship locations” (Scullionand Collings, 2006), each company had computer listings of their hotel propertieswhere managers were only offered limited length transfers as operating conditions, aswell as the owner relations, were particularly demanding. In this study, such locationsincluded; Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Uganda, Nigeria, Russia and Bulgaria. Postings tosuch localities were seen by the HR executives, and their teams, as beneficial formanagers’ future careers, but difficult culturally. Therefore, strict conditions wereapplied, evidenced in the assignment contracts made with owners and expatriates.

A very different type of problem was faced by HR executives when their managerswent “native” (Black and Gregersen, 1992; Van Oudenhoven et al., 2001). In thetraditional sense, this occurs where a manager assumes the lifestyle and managerialstyle of the country in which they are posted. In the international hotel industry,it involved managers, GMs in particular, “going native” with the property ownerand losing their allegiance to their IHC. This was only an occasional problem forIHCs, and occurred due to the typical longevity of hotel management contracts ormanagers’ personal circumstances (e.g. such as a commitment to children’s schoolingor spouses’ jobs).

Owner interferencePart of the underlying problem with transferring managers was the interference byproperty partners in selection decisions. “Beauty parades” of eligible managers wereoften demanded by management contract partners, and the comments from theBritbuyer executive were characteristic of the situations HR executives and their teamsfound themselves in:

We have owners, for example, [. . .] but we have owners who are very, very clear about thepeople who we are likely, or more often than not, we can’t employ. Usually, it’s in terms ofnationalities and colours, race and sexual preferences they don’t like. It is their hotel and ifthey say “I don’t want somebody with red hair” then you don’t put somebody with red hair in,it’s as simple as that.

Hotelmanagement

contracting

647

An executive from Anglo-American Premium identified that the policy in hiscompany was:

Usually, owners interview the three candidates we put forward for each GM position andinvariably, well [. . .] they select the candidate preferred by the company, though VicePresidents often have to use some powers of persuasion.

Additionally, the HR executives identified some common sense or “unwritten rules” interms of securing senior management positions in their management contract units.These included no female appointments to senior positions in some Middle East states;Jewish managers would not be placed in Muslim countries; and no Greek managerscould be located in Turkey, and vice versa. Indeed, certain regions of the world seemedto be associated with particular problems with owner-company and owner-managerrelations, specifically, the Middle East, parts of Eastern Europe and China. None of thecompany executives suggested that they could abandon such locations in the face ofdifficult owner-relations but wanted to emphasise the challenges involved, as theUSmixedeconomy executive stated:

As far as ownership relations are concerned some owners have a lot more say than others. Inthe Middle East owners have a lot of say and between two and three candidates are alwaysput forward for key management posts.

The risks associated with managing hotels in certain areas of the world wereparticularly apparent to the HR executives and their teams. However, they alsocommented on the strategic benefits of developing their hotel portfolios in difficult(often developing or turbulent) regions of the world. Typically, these benefits werebased upon the needs of international customers, and also on relations with existingand future business partners. Assessing the risks of particular hotel ventures wasfraught with complications and an adverse experience in one country often meant thatother ventures were jeopardised (Butler, 2008).

Global versus local management talentA key theme within the expatriate literature has been the deliberations over thelocalisation of subsidiary management positions (Collings and Scullion, 2006; DeNisiet al., 2006; Scullion, 1994; Scullion and Brewster, 2001). This issue works both ways inthe international hotel industry as the HR executives recounted instances where specificnationalities were demanded for specific positions. For example, “only French headchefs” or “Swiss or British GMs” were sought due to the status associated with certainnational stereotypes in the hotel industry. However, the IHC respondents suggested theywould all be increasing the numbers of HCNs in unit management posts but would notaltogether abandon the use of expatriates due to issues of control, co-ordination, andprestige (for properties, partners and customers). These difficulties caused most concernto those IHCs with a greater concentration on softer, more exclusive, prestige servicehotel brands (such as Britbuyer, USMixedeconomy, Anglo-American Premium,Contractman International, Euroalliance and Globalalliance – Table I) who were moreinternationally focused, but also locally adapted. Here, the HR executives and their teamshad developed initiatives where junior managers from the country in question wererecruited and provided with an intensive corporate development programme. Theseprogrammes included experience in the companies’ luxury properties across severaldifferent countries, and some limited time at regional or head-office. Such secondments

IJCHM22,5

648

often lasted for several years so that the HCNs could eventually take up a seniormanagement posts in their home units following extensive exposure and socialisationwithin the IHC. This can be seen as a hotel sector variation of inpatriation (Harvey et al.,1999, 2000) which highlight the importance of operational experience and renderheadquarter postings inappropriate.

A rather different example of owner intervention (in this case the government) wasprovided by the Britbuyer executive regarding a new management contract in anEastern European country. He stated:

I mean we have this situation in a certain Eastern European country. The hotel in thatcountry is actually government owned and the GM is a host country national who is agovernment employee. We are trying to put a sales director into that hotel, and we have foundsome very good candidates, but every time we put forward a candidate who speaks Russian,which we think is important, they get turned down, because they can hear as well as speak.The next time we put forward a candidate we are going to tell them not to speak Russian infront of them, the owners and the GM.

These political ramifications were also complicated by the company’s previousexperience in the region and the difficulty of establishing trust between the partners.This case epitomizes the problems of the partners originating from different culturaland institutional backgrounds and attempting to use those differences to their ownadvantage in the venture.

Developing future hotel GMsThe executive respondents also identified that their companies encountered problemsin securing first-time GM posts due to management contract ownership issues. Someunits, because of their owners and the complexity of facilities, were not suitablefor initial or even early unit management experience. The Euroalliance executivecommented in a similar vein on first time GM appointments:

There are the units that managers can cut their teeth on, i.e. they’re not really going to screwup the business if they go awfully wrong, we can keep an eye on them and there are otherhotels which are on the “no-no” list unless you’ve got some experience. It could be culturalrelations, unions or the fact they make the most money for the company.

While all companies faced this problem to some extent it did seem to present fewerdilemmas for companies which had “harder” brands or operated hotels at lower servicelevels (budget brands – Euromultigrow and Franchiseking in Table I). The executivesalso identified how prior to appointment to GM and deputy GM positions, hotelmanagers were primarily recruited, selected, developed, and rewarded due to theirmanagerial, leadership and technical skills and knowledge. However, at GM and deputyGM levels the ability to manage key stakeholders, specifically property owners, becamea vital skill. Exposure to different owners during the development of a manager’s careerwas therefore becoming part and parcel of building talent for the IHCs and the managersthemselves.

Across the IHCs, the executives identified the important role of area GMs (GMsresponsible for several hotels) and regional operations managers who worked tosupport and maintain effective relationships between unit GMs, owners and the IHCs’corporate/regional headquarters. These individuals all had extensive GM experienceand travelled regularly to provide the organisational glue between the hotels and the

Hotelmanagement

contracting

649

corporate brand and service standards. They knew their cluster of hotels “inside out”and were influential in the management of hotel managers too. However, theoperational focus of their roles made such executives wary of developing managerswho they perceived might be unpopular with property owners. In one case, an HRexecutive commented that he had experienced regional executives reluctant to developfemale managers with the argument that “the owners just wouldn’t buy it”. The HRexecutive and his team countered such claims by demonstrating the higher proportionof female managers the company’s franchised units.

The impact of “asset light” market entry modes on IHRM practicesIn effect, executives’ sensitivity to the perceived preferences of property owners hadshaped organisational practice and effective talent management. In addition, someowners’ were reluctant to have staff (at all levels) participate in their IHCs’ training anddevelopment initiatives. Schemes such as graduate management or executivedevelopment programmes were rejected by some owners on the grounds that theirproperty would not specifically benefit from such HRM investments. While all therespondents used management contracting as an international expansion method, andexperienced the same problems to a degree, the severity of these challenges did differacross the sample. The Franchiseking and Euromultigrow companies (Table I) withtheir larger portfolios of budget and mid-market brands experienced more investmentfrom “sleeping partners” or at least those who did not feel the need to interfere:

This is because most of the property owners which Euromultigrow has contracts with aresolely interested in financial returns or real estate investments (HR executiveEuromultigrow).

It was the IHCs with portfolios of luxury hotels which suffered more extensively from theproblems of “ego-trip ownership” (Guilding, 2006). There was seen to be a directrelationship between the higher service levels and luxury hotel facilities of some unitsand the recalcitrance and interference of owners, so managing these delicaterelationships was an on-going challenge for corporate and regional industry executives.

One company, Contractman International, had developed a particular approach toeffectively managing its management contracts with property owners. It was the onlycompany in the sample to use management contracting as its sole market entry mode,and although it did have some limited capital investment in properties it did not ownany properties outright. Its relationships with owners were noteworthy due to the waysin which owners were treated as partners, with their own specific aims and desires.The argument from the HR executive was that; “We work with owners like they are ourpartners. So we will always be fair and honest about our reasons for decisions, forthings, for people.” This can be contrasted with the more adversarial positionsexpressed about owners by the other IHCs’ HR executives and their teams. This maybe because Contractman International included its regional HR teams in searching hostcountries for management contract partners and encouraged their participation incontract agreement discussions from their earliest inception. The company alsoundertook detailed labour market investigations in host countries and specificlocations to ascertain the quality of human resources and operating implications fortheir HRM practices. In addition, it seems that because Contractman International hadno alternative market entry modes through which to achieve international expansion,

IJCHM22,5

650

it prioritised developing effective management contract partnerships. This meant thatwhile the company still experienced some of the HRM challenges associated with thisasset light method it had better communication mechanisms in place to tackle them.Contractman International worked hard to sustain relations with its owners and thiswas important in creating competitive advantage over its industry rivals.

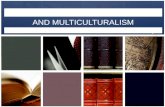

DiscussionThe data clearly demonstrate that management contracts in the international hotelindustry shape the management of strategic human resources (Brown et al., 2003; Chungand Enderwick, 2001; Erramilli et al., 2002). Furthermore, the impact of the managementcontracting “bricks and brain split” on the effective management of key humanresources is apparent. Figure 1 shows the key factors in the bricks and brains split byhighlighting the broader contexts in which owners and IHCs exist and their approachesto managing human resources within international hotel management contracts. Theinfluence of owners is seen to have a bearing on management competences, selection,transfers, and development, ultimately indicating that IHCs have only limited controlover their key asset when participating in such arrangements. These results highlightthat the HRM implications of modal choice are critical to the continued success of IHCsand the wider industry (Litteljohn et al., 2007).

The characteristics of owners themselves suggest that IHCs should be very careful intheir initial partner selection (Schuler and Tarique, 2006). Research (Altinay, 2001; Antel,2005; Panvisavas and Taylor, 2006) identifies the management contract option as fraughtwith political issues in partner selection. The fierce competition in the industry for specificlocations and the requirement for speedy entry and contract signing are additionaldimensions which restrict detailed and lengthy compatible partner discussions(Beals, 2006; Beals and Denton, 2004; Whitla et al., 2007). Yet, the long-termimplications of a troubled management contract relationship can be detrimental, andmay even undermine other ownership arrangements, and ultimately long-term survival

Figure 1.The human resource

dilemmas facing IHCsinvolved in management

contracts

IHCsBroader context:

• Mainly Anglo-Saxon values• Industry and technical expertise• Multiple and geographically disparate portfolio• Limited equity involvement• Brand presence and market share• International focus

• Local values and practices: host country culture and institutional practices• Local business expertise• Substantial equity involvement• Return on investment• Ego ownership• Local or domestic focus

Loyalty to owner/hotel

Loyalty to company

Beauty paradeRecruitment andselection based on competence

Long term competent andknowledgeable managers

Long-term development ofcorporate human resources

Stereotyped views ofhotel managers

Equal opportunitiesand diversity

Local and ‘ego’ valuesNational valuesand global ambitions

Brainsmanagers

Bricksproperty

Mediating tensions and practices

Less owner influence on budget,hard brands

More owner influence on luxury,soft brands

OwnersBroader context:

Hotelmanagement

contracting

651

(Butler, 2008; Erramilli et al., 2002; Whitla et al., 2007). Where IHCs hope to expand inlocations known for “challenging” ownership relations then the training and support ofcorporate executives in their negotiations with partners will be invaluable (Antel, 2005).

The mediating tensions and practices in Figure 1 highlight the problems for IHCsdeveloping human resource advantage through their strategic human resources(Boxall, 1996; Boxall and Purcell, 2003, 2007). The IHCs’ capacity to develop and deployhuman resources with the right skills, knowledge and abilities can be continuouslycompromised by owners. In the light of wider ethical, moral and business concernsabout equal opportunities and diversity management, the HR executives faced furtherfrustrations in selecting the best managers for their units (Brewster et al., 2007).

The HR executive respondents were also wary of the issue of securing the exit ofsuccessful managers from certain owners’ properties. Overall, these experiencessuggest that the corporate HR departments in IHCs have a vital role to play in workingwith their peers to shape management contract agreements. By highlighting some ofthe typical tensions in management contracts, both partners can be persuaded of thevalue of setting clearer mutual HRM parameters within contracts and agreeinglonger-term approaches to talent management. The example of ContractmanInternational, who experienced fewer difficult owner relationships, and proactivelyparticipated in developing partnerships, serves as an important role model. This firm’scommitment to the management contract as its sole means of international growthmeant that organisational expertise and capability in forging mutually beneficialowner-operator partnerships resulted in fewer problems over the development ofmanagerial talent (Brown et al., 2003). This example suggests that where companiesaim to expand, in the more challenging luxury hotel sector, single market entry modeexpertise may create a more coherent corporate strategy.

There may also be a role for corporate HR departments in promoting diversityinitiatives with prospective and existing owners (Dietz and Petersen, 2006) givencurrent demographic forecasts. Already within the broader hotel industry, there hasbeen a drive towards pursuing partnerships with atypical business investors(Anon., 2007), from a broad range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds. This willhopefully provide direct evidence for companies to present to owners the efficacy (andethics) of selecting hotel managers on the basis of their talent and abilities rather thanstereotyped national and cultural characteristics.

The IHCs had developed their own version of inpatriation schemes, whichsupported their property partners’ desires to localise their management teams (Harveyet al., 1999, 2000). The ability to take a long-term development approach with HCNswas seen as supporting and facilitating knowledge transfer to host countries. Theevidence from these inpatriate development schemes and managerial developmentinitiatives highlights that managerial development responsibilities lie very much withthe IHCs rather than the owners. The ability of IHCs to engage their owners inshouldering this burden, as their portfolios grow and human resource assets increase,will become critical in the future. The already complex nature of hotel managementcontracts (Beals, 2006; Beals and Denton, 2004; Schlup, 2003), suggests more attentionbe paid to HRM issues, and specifically the development of managerial talent, to realiseappropriate returns for IHCs and property owners.

The results also highlight that companies need to address the managerialcompetences of (aspiring) GMs (the intellect and functioning of the “brains”) to ensure

IJCHM22,5

652

that owner relations are prioritised in management development initiatives. Thecompanies had been slow to identify owner relations as a distinct development needalongside their changing market entry decisions (Whitla et al., 2007). Analysis ofmanagers with successful owner relations expertise might help companies pinpoint thecompetences managers need to accrue, and develop this important capabilityprogressively. As management contracting grows, and other asset light market entrymodes develop, the importance of GMs with effective investor relationship skills willbecome more highly prized.

Finally, research with owners themselves may also provide insights into thecompetences required to manage these critical relationships. Owner accounts ofmanagement contracting have been more limited (Beals, 2006; Beals and Denton, 2004;Guilding, 2006) with a focus directed primarily at the issues of investment andcontractual arrangements. However, the evidence from this study demonstrates thatowners play a critical role in both inhibiting and facilitating operational and corporatemanagerial talent and their perspective on this issue warrants primary investigation.

ConclusionThis study highlights the IHRM implications of industry developments involving thesale of property assets by hotel operators as part of wider international expansionstrategies (Whittaker, 2006). This trend is likely to continue and hotel companies arefaced with the need to develop new ways of managing their human resources alongsideinterventions from (some of) their business partners. The IHCs within this studydemonstrate a lack of agency where growth through low risk entry options constrainsother functional decisions and practices (Child, 1997; Truss, 2004). The research alsohighlights the permeable boundaries of organisations where hotel operators can onlyachieve competitive international hotel portfolios through investment with (local)business partners. These partnerships clearly constrain companies’ capacity to buildand effectively manage their human resources. This creates a paradox where companieshave divested their main property assets by adopting management contracts, forcingthem to become more reliant on the expertise of their human resources. These samehuman resources, however, cannot be managed in line with the companies’ strategiesand goals because of the relinquished control passed to property owners.

This paper offers original empirical insights into the impact of permeableorganisational boundaries where companies expand using limited equity involvementstrategies. Most explanations of market entry modes fail to capture the humanperspective and this paper directly addresses such omissions. It is apparent from thisstudy that while asset light strategies may offer international brand expansionadvantages they can simultaneously undermine the managerial expertise and talentupon which that brand reputation is built. Therefore, managing the organisational andcompetitive compromises of the management contract market entry mode will becritical to the long-term success of IHCs.

While this research offers valuable insights into the implications of entry modedifferences on IHRM, it does so in a narrow way as the focus is on managers.Furthermore, only HR executives and their teams were involved directly in evidencegathering. Without the views of other IHC corporate executives, the perceptions of theadverse implications management contracts may be one-sided. In addition, hotelowners, the other side of the management contract relationship, were not asked about

Hotelmanagement

contracting

653

their perceptions of people management practices and their responsibilities. There arethen clear incentives to develop a more coherent understanding of this area in order formore effective management contracts to be produced in the intensely competitiveinternational hotel industry.

References

Altinay, L. (2001), “International expansion of a hotel company”, PhD thesis, Oxford BrookesUniversity, Oxford.

Anon. (2007), “Accor North America seeks to improve diversity in the hospitality industryby providing opportunities and tools for minorities to succeed”, available at: www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4032324

Antel, S.C. (2005), “Do’s and don’ts for getting hotel deals done in the Russian/CIS markets”,Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, Vol. 5, pp. 212-18.

Aung, M. (2000), “The Accor multinational hotel chain in an emerging market: through the lensof the core competency concept”, The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 20 No. 3, pp. 43-60.

Bader, E. and Lababedi, A. (2007), “Hotel management contracts in Europe”, Journal of Retail &Leisure Property, Vol. 6, pp. 171-9.

Barham, K. and Oates, D. (1991), The International Manager, Economist Books, London.

Beals, P. (1995), “The hotel management contract: lessons from the North American experience”,in Harris, P. (Ed.), Accounting and Finance for the International Hospitality Industry,Ch. 15, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 278-94.

Beals, P. (2006), “Hotel asset: management: will a North American phenomenon expandinternationally?”, in Harris, P. and Mongiello, M. (Eds), Accounting and FinancialManagement: Developments in the International Hospitality Industry,Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Beals, P. and Denton, G. (2004), “The current balance of power in North American hotelmanagement contracts”, Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, Vol. 4 No. 2, pp. 129-45.

Bender, B., Partlow, C. and Roth, M. (2008), “An examination of strategic drivers impacting U.S.multinational lodging corporations”, International Journal of Hospitality & TourismAdministration, Vol. 9 No. 3, pp. 219-43.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1992), “Serving two masters: managing the dual allegiance ofexpatriate employees”, Sloan Management Review, Summer, pp. 61-71.

Bonache, J. and Zarraga-Oberty, C. (2008), “Determinants of the success of internationalassignees as knowledge transferors: a theoretical framework”, International Journal ofHuman Resource Management, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 1-18.

Boxall, P. (1996), “The strategic HRM debate and the resource-based view of the firm”, HumanResource Management Journal, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 59-75.

Boxall, P. (2003), “HR strategy and competitive advantage in the service sector”, HumanResource Management Journal, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 5-20.

Boxall, P. and Purcell, J. (2003), Strategy and Human Resource Management, PalgraveMacmillan, Basingstoke.

Boxall, P. and Purcell, J. (2007), Strategy and Human Resource Management, 2nd ed., PalgraveMacmillan, Basingstoke.

Boxall, P. and Steeneveld, M. (1999), “Human resource strategy and competitive advantage:a longitudinal study of engineering consultancies”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 36No. 4, pp. 443-63.

IJCHM22,5

654

Brewster, C., Sparrow, P. and Vernon, G. (2007), International Human Resource Management,2nd ed., CIPD, London.

Brookes, M. (2007), “The design and management of diverse affiliations: an exploration ofinternational hotel chains”, unpublished PhD thesis awarded by Oxford BrookesUniversity, Business School, Oxford.

Brookes, M. and Roper, A. (2008), “The changing nature of hotel management contracts and theresponse from hotel management firms”, To be presented at the BAM Conference –Hospitality, Leisure and Tourism Management Track, Harrogate, September.

Brown, J.R., Dev, C.S. and Zhou, Z. (2003), “Broadening the foreign market entry mode decision:separating ownership and control”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 34 No. 5,pp. 473-88.

Bryman, A. (1992), “Quantitative and qualitative research: further reflections on theirintegration”, in Brannen, J. (Ed.), Mixing Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Research,Avebury, Aldershot.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2007), Business Research Methods, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press,Oxford.

Butler, J. (2008), “Hotel Lawyer: Ritz-Carlton breached contractual and fiduciary duties underhotel management agreement giving rise to free termination, $10.3 million in damages plusattorneys fees. When will hotel operators ‘get it’?”, available at: http://hotellaw.jmbm.com/2008/02/hotel_lawyer_ritzcarlton_breac_1.html

Caligiuri, P. and Colakoglu, S. (2007), “A strategic contingency approach to expatriateassignment management”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 17 No. 4,pp. 393-410.

Child, J. (1997), “Strategic choice in the analysis of action, structure and organizations andenvironment: retrospect and prospect”, Organization Studies, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 43-76.

Chung, H.F.L. and Enderwick, P. (2001), “An investigation of market entry strategy selection:exporting vs foreign direct investment modes – a home-host country scenario”, AsiaPacific Journal of Management, Vol. 18, pp. 443-60.

Collings, D.G. and Scullion, H. (2006), “Strategic motivations for international transfers: why doMNC’s use expatriates?”, in Scullion, H. and Collings, D.G. (Eds), Global Staffing,Routledge, London, pp. 39-56.

Contractor, F.J. and Kundu, S.K. (1998), “Modal choice in a world of alliances: analyzingorganizational forms in the international hotel sector”, Journal of International BusinessStudies, Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 325-58.

D’Annunzio-Green, N. (1997), “Developing international managers in the hospitality industry”,International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 9 Nos 5/6,pp. 199-208.

D’Annunzio-Green, N. (2002), “An examination of the organizational and cross-culturalchallenges facing international hotel managers in Russia”, International Journal ofContemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 20-32.

DeNisi, A.S., Toh, S.M. and Connelly, B. (2006), “Building effective expatriate-host countrynational relationships: the effects of human resources practices, international strategy andmode of entry”, in Morley, M.J., Heraty, N. and Collings, D.G. (Eds), International HumanResource Management and International Assignments, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke,pp. 1114-34.

Hotelmanagement

contracting

655

Dietz, J. and Petersen, L.E. (2006), “Diversity management”, in Bjorkmann, I. and Stahl, G. (Eds),Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management, Edward Elgar,Camberley, pp. 223-43.

Dunning, J.H. and Kundu, S. (1995), “The internationalization of the hotel industry – some newfindings from a field study”, Management International Review, Vol. 35, pp. 101-33.

Dunning, J.H. and McQueen, M. (1982), “Multinational corporations in the international hotelindustry”, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 9, pp. 48-63.

Erramilli, M.K., Agarwal, S. and Dev, C.S. (2002), “Choice between non-equity entry modes:an organizational capability perspective”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 33No. 2, pp. 223-42.

Eyster, J.J. (1997), “Hotel management contracts in the U.S.”, Cornell Hotel & RestaurantAdministration Quarterly, June, pp. 21-33.

Forte, C. (1986), Forte: The Autobiography of Charles Forte, Sidgwick and Jackson, London.

Gardner, T.M. (2005), “Human resource alliances: defining the construct and exploring theantecedents”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 16 No. 6,pp. 1049-66.

Graham, I. (2006), “Cross-border reporting for performance evaluation”, in Harris, P. andMongiello, M. (Eds), Accounting and Financial Management: Developments in theInternational Hospitality Industry, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Guilding, C. (2006), “Investment appraisal issues arising in hotels governed by a managementcontract”, in Harris, P. and Mongiello, M. (Eds), Accounting and Financial Management:Developments in the International Hospitality Industry, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Harvey, B. (2007), “International hotels”, Journal of Retail and Leisure Property, Vol. 6, pp. 189-93.

Harvey, M.G., Novicevic, M.M. and Speier, C. (1999), “Inpatriate managers: how to increase theprobability of success”, Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 51-81.

Harvey, M.G., Novicevic, M.M. and Speier, C. (2000), “Strategic global human resourcemanagement: the role of inpatriate managers”, Human Resource Management Review,Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 153-75.

Harzing, A. and Van Ruysseveldt, J. (Eds) (1995), International Human Resource Management,Sage, London.

Harzing, A. and Van Ruysseveldt, J. (Eds) (2004), International Human Resource Management,2nd ed., Sage, London.

Hollensen, S. (2004), Global Marketing: A Decision-oriented Approach, Prentice-Hall, London.

Hoque, K. (1999), “New approaches to HRM in the UK hotel industry”, Human ResourceManagement Journal, Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 64-75.

Johnson, C. (1996), “Globalization and the multinational hotel industry”, Special report submittedto The International Association of Scientific Experts in Tourism for the 46th AnnualConference, Rotorua.

Johnson, C. (2002), “Locational strategies of international hotel corporations in Eastern Europe”,PhD thesis presented to the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at the University ofFribourg, Fribourg.

Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2005), Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text andCases, 7th ed., FT/Prentice-Hall, Harlow.

Jones, C., Thompson, P. and Nickson, D. (1998), “‘Not part of the family?’ The limits to managingthe corporate way in international hotel chains”, The International Journal of HumanResource Management, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 1048-63.

IJCHM22,5

656

Kriegl, U. (2000), “International hospitality management”, Cornell Hotel & RestaurantAdministration Quarterly, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 64-71.

Litteljohn, D. (2003), “Hotels”, in Brotherton, B. (Ed.), The International Hospitality Industry:Structure, Characteristics and Issues, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp. 5-29.

Litteljohn, D., Roper, A.J. and Altinay, L. (2007), “Territories still to find – the business of hotelinternationalisation”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 18 No. 2,pp. 167-83.

Magnini, V. (2008), “Practising effective knowledge sharing in international hotel joint ventures”,International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 27, pp. 249-58.

Marchington, M., Carroll, M. and Boxall, P. (2003), “Labour scarcity, the resource-based view, andthe survival of the small firm: a study at the margins of the UK road haulage industry”,Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 13 No. 4, pp. 5-22.

Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M. (1994), Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook,Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Nickson, D. (2007), Human Resource Management for the Hospitality and Tourism Industries,Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Panvisavas, V. and Taylor, S.J. (2006), “The use of management contracts by international hotelfirms in Thailand”, International Journal of Contemporary HospitalityManagement, Vol. 18No. 3, pp. 231-45.

Robson, C. (1993), Real World Research, Blackwell, Oxford.

Robson, C. (2002), Real World Research, 2nd ed., Blackwell, Oxford.

Roper, A., Doherty, L., Brookes, M. and Hampton, A. (2001), “Company man meets internationalcustomer”, in Guerrier, Y. and Roper, A. (Eds), A Decade of Hospitality ManagementResearch: Tenth Anniversary Volume, CHME/Threshold Press, Newbury, pp. 14-36.

Rosenzweig, P.M. (2006), “The dual logics behind international human resource management:pressures for global integration and local responsiveness”, in Stahl, G.K. and Bjorkman, I.(Eds), Handbook of Research in International Human Resource Management, Ch. 3,Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 36-48.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2000), Research Methods for Business Students,2nd ed., FT/Prentice-Hall, Harlow.

Schlup, R. (2003), “Hotel management agreements: balancing the interest of owners andoperators”, Journal of Retail and Leisure Property, Vol. 3, pp. 331-42.

Schuler, R.S. and Tarique, I. (2006), “International joint venture system complexity and humanresource management”, in Bjorkman, I. and Stahl, G.K. (Eds), Handbook of Research inInternational Human Resource Management, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp. 385-404.

Schuler, R.S., Jackson, S.E. and Luo, Y. (2004), Managing Human Resources in Cross-borderAlliances, Routledge, New York, NY.

Scullion, H. (1992), “Strategic recruitment and development of the ‘international manager’: someEuropean considerations”, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 3 No. 1, pp. 57-69.

Scullion, H. (1994), “Staffing policies and strategic control in British multinationals”,International Studies of Management & Organization, Vol. 24 No. 3, pp. 86-104.

Scullion, H. and Brewster, C. (2001), “The management of expatriates: messages from Europe?”,Journal of World Business, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 346-65.

Scullion, H. and Collings, D.G. (Eds) (2006), Global Staffing, Routledge, London.

Hotelmanagement

contracting

657

Scullion, H. and Starkey, K. (2000), “In search of the changing role of the corporate humanresource function in the international firm”, International Journal of Human ResourceManagement, Vol. 11 No. 6, pp. 1061-81.

Segal-Horn, S. (2000), “The search for core competencies in a service multinational”, in Aharoni, Y.and Nachum, L. (Eds), Globalization of Services: Some Implications for Theory and Practice,Routledge, London, pp. 320-33.

Silverman, D. (1997), “Introducing qualitative research”, in Silverman, D. (Ed.), QualitativeResearch: Theory, Method and Practice, Sage, London, pp. 1-8.

Silverman, D. (1999), Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook, Sage, London.

Slattery, P., Gamse, I. and Roper, A. (2008), “The development of international hotel chains inEurope”, in Olsen, M.D. and Zhao, J.L. (Eds), Handbook of Hospitality StrategicManagement, Elsevier, Oxford.

Stonehouse, G., Hamill, J., Campbell, D. and Purdie, T. (2000), Global and Transnational Business:Strategy and Management, Wiley, Chichester.

Todd, G. and Mather, S. (1995), The International Hotel Industry: Corporate Strategies & GlobalOpportunities, Economic Intelligence Unit, London.

Todd, G. and Mather, S. (2001), “The structure of the hotel industry in Europe”, in Hall, L. (Ed.),New Europe and the Hotel Industry, PriceWaterhouseCoopers Hospitality and LeisureResearch, London, pp. 16-26.

Truss, C. (2004), “Who’s in the driving seat? Managing human resources in a franchise firm”,Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 57-75.

Van Oudenhoven, J.P., van der Zee, K. and van Kooten, M. (2001), “Successful adaptationstrategies according expatriates”, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 25,pp. 467-82.

Welch, D. and Welch, L. (1994), “Linking operation mode diversity and IHRM”, The InternationalJournal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 5 No. 4.

Whitla, P., Walters, P.G.P. and Davies, H. (2007), “Global strategies in the international hotelindustry”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 26, pp. 777-92.

Whittaker, C. (2006), “Sale and leaseback transactions in the hospitality industry”, in Harris, P.and Mongiello, M. (Eds), Accounting and Financial Management: Developments in theInternational Hospitality Industry, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

WTO (2007), Trends in Tourist Markets, World Tourism Organization, Madrid.

Zhao, J.L. and Olsen, M.D. (1997), “The antecedent factors influencing entry mode choices ofmultinational lodging firms”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 16No. 1, pp. 79-98.

Zhao, X. and Decker, R. (2004), “Choice of foreign market entry mode: cognitions from empiricaland theoretical studies”, available at: http://bieson.ub.uni-bielefeld.de/volltexte/2004/507/pdf/m_entry.pdf

Corresponding authorJudie Gannon can be contacted at: [email protected]

IJCHM22,5

658

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: [email protected] visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints