The impact of coaching in South African primary science InSET

-

Upload

stephen-harvey -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

3

Transcript of The impact of coaching in South African primary science InSET

Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205www.elsevier.com/locate/ijedudev

The impact of coaching in South African primary scienceInSET

Stephen Harvey*

Zisize Project, Box 391, Nongoma, 3951 South Africa

Abstract

This article presents evidence from an evaluation conducted by the Primary Science Programme (PSP) in SouthAfrica, concerning the impact of classroom-based coaching on the teaching methods used by primary science teachers.The methods used by teachers provided with both workshops and classroom-based coaching were compared with thoseused by teachers who received workshops only and a control group who received no InSET at all. The findings showedthat teachers who received coaching made substantial changes, whereas most teachers who received workshops-onlyremained similar to the control group. A social constructivist approach is adopted in interpreting these findings. Theimplications of this study for designing effective InSET in developing countries are also discussed. 1999 ElsevierScience Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Teacher education; In-service training; Primary science; South Africa; Constructivism; Leader teachers

1. Introduction

In South Africa, most formerly-black schools arestill characterised by deprived material conditions,large class sizes, weak school management, andlow levels of teacher education (see Table 1).Teaching methods are dominated by whole-classinteraction, concentrating on low-order questioningand chorus recitation, with little pupil activity.English is widely used as the medium of instruc-tion, though the capacity of pupils for self-expression in this language is often very limited(Hofmeyer and Hall, 1996; Ntshingila-Khosa, 1994and Table 2). Given the country’s recent history,there is great expectation for change. As in many

* Tel.: 1 27-358-310555; fax:1 27-358-310555; e-mail:[email protected]

0738-0593/99/$ - see front matter 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.PII: S0738 -0593(99 )00012-7

developing countries, most South African initiat-ives aimed at improving the quality of teachingemphasise the importance of inservice educationand training (InSET).

This study presents evidence relevant to thedevelopment of more effective models of InSETwhere activity-based teaching methods are beingintroduced. In particular, it focuses on the role ofclassroom-based coaching. The teaching methodsemployed by primary science teachers who wereprovided with coaching are compared with thosewho received only centre-based workshops and acontrol group who received no InSET.

The evidence presented comes from an evalu-ation of the impact of InSET provided by the Pri-mary Science Programme (PSP) in 46 schools inthe Madadeni area of KwaZulu-Natal between1993 and 1996 (Harvey, 1997). In keeping withchanges in South African curriculum policy, PSP

192 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Table 1Mean of contextual variables

Phase 1 (n5 19) 2 (n 5 17) 3 (n 5 19) 0 (n 5 17) Total (n5 72)

Teacher characteristicsGender (% female) 68.4 41.2 47.1 42.1 50Years teaching experience 11.2 11.1 12.0 9.3 10.8Years teaching science 7.6 7.9 8.5 4.9 7.2Qualifications (% with at least 3-year PTD) 63.2 58.8 57.9 58.8 59.7Total no. workshops attended during study 11.2 10.1 11.2 1.2 8.3School characteristicsTotal no. pupils enrolled 865.1 705.5 807.3 742.8 819.6Pupil:teacher ratio 44.6 40.4 42.3 43.7 42.8Observed class size 61.8 52.2 52.1 57.8 56.2Total no. teaching staff 18.4 17.1 19.6 16.5 17.0Total no. classrooms 14.6 15.3 14.0 13.2 14.3% schools with electricity 52.6 29.4 82.4 26.3 47.2% schools with telephone 68.4 58.8 58.8 36.8 63.9% schools with running water 63.2 17.6 35.3 35.3 37.5Urban/rural (% rural) 36.8 70.6 35.3 73.7 54.2Condition of buildings (rated on scale 1–5) 2.8 3.1 2.9 2.8 2.9Condition of furniture (rated on scale 1–5) 2.9 2.9 2.9 2.8 2.9% classrooms with sloping double desks 100 94.1 100 100 98.6% classrooms with adequate seating 84.2 94.1 88.2 94.7 90.3% classrooms with space to circulate 84.2 94.1 82.2 94.7 90.3% classrooms with space to rearrange desks 63.2 94.1 82.4 52.6 72.2% schools with science kit 100 100 89.2 47.4 83.3Condition of apparatus (rated on scale 1–5) 3.7 3.6 3.3 1.7 3.4% of pupils with own text book 47.4 68.4 64.7 64.7 61.1Staff morale (rated on scale 1–5) 3.3 3.6 3.4 3 3.3Staff cooperation (rated on scale 1-5) 3.7 3.6 3.5 3 3.4Principal’s support (rated on scale 1-5) 3.6 3.9 3.3 3 3.4

is working towards a vision of quality science edu-cation that is activity-based and that developspupils’ scientific knowledge, process skills andcritical attitudes, in a balanced way. In this goalPSP shares much in common with many other pro-jects worldwide that are also working within tightresource constraints (Lewin, 1992).

2. PSP’s InSET methods

PSP’s original implementation strategy duringthe 1980s did not have a school-based component.It relied exclusively on providing science kits andcentre-based workshops. Early evaluations showedthat this strategy was rarely effective in changing

classroom practice (Morphet, 1987; Potter andMoodie, 1991). As a result, ‘classroom support’evolved (Raubenheimer, 1992), which mayencompass any of the following activities: mode-ling demonstration lessons, cooperative planning,team-teaching, negotiated lesson observation,offering advice, mediating critical reflection, draft-ing school science teaching policies, supportingteacher collaboration, and supporting the manage-ment of learning resources.

PSP implementation in Madadeni started inJanuary 1994 with the supply of a low-budget kitof science apparatus to schools, and an orien-tation workshop. For the following three years,teachers had access to seven one-day workshopsper year. There was a focus on subject knowledge

193S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Table 2Means of selected SCOS observation items

Item/description Observation group

Preparation 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0Number of teachers in the sample 19 19 17 17 19 17% teachers expressed aims in terms of content 100 100 100 100 100 100% teachers expressed aims in terms of process 21.1 15.8 17.6 5.9 12.5 5.3skills% teachers prepared resources in advance 100 89.5 88.2 76.5 76.5 5.2

Presentation 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0% teachers sought pupils’ existing knowledge 78.9 100 88.2 100 82.3 63.2% teachers used visual aids 100 94.7 88.2 82.4 70.6 63.2% teachers made factual error 42.1 10.5 47.4 29.4 23.5 35.3Estimated % lesson time spent on teacher-talk 73.4 71.6 77.1 72.9 73.5 81.1% teachers led practical demonstration 47.4 47.4 52.9 68.8 52.9 47.4Teacher skill with apparatus (rated 1–5) 3.7 3.4 3.1 3.3 3 2.9% lessons summarised at conclusion 73.7 78.9 70.6 100 52.9 57.9Logical sequence of lesson (rated 1–5) 3.6 3.5 3.4 3.5 3.1 3

Pupil Activity 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0% lessons in which written work observed 57.9 63.1 29.4 75 52.9 31.6% lessons in which practical work observed 57.9 21.1 47.1 75 17.6 0% lessons in which group work observed 52.6 42.1 47.1 62.5 35.3 10.5

Language 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0% lessons > 5 pupils spoke original English 42.1 84.2 35.3 53.3 52.9 31.6sentence% lessons > 5 pupils wrote original English 0 5.3 0 66.7 11.8 10.5sentence% teachers used Zulu at least once in lesson 94.8 89.5 82.4 94.1 76.5 63.2% pupils used Zulu at least once in class discussion 31.6 42.1 29.4 70.6 29.4 31.6

Questioning and Assessment 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0Number of oral questioning strategies counted 4.3 4.6 3.5 4.8 4.2 3.8Estimated % of pupils answering individually 46.8 47.4 44.1 43.0 43.2 37.7% lessons in which pupils asked own question 10.5 31.6 0 0 11.8 5.3% lessons conclusion which evaluated 84.2 73.7 76.5 88.2 58.8 68.4understanding% lessons with individual marking of books 31.6 26.3 0 47.1 5.9 10.5% lessons girls and boys contributed equally in oral 94.7 84.2 82.4 76.5 88.2 89.5work

Classroom Management 1.1 1.2 2.1 2.2 3 0Time management (rated 1-5) 3.6 3.6 3.6 3.5 3.1 3% teachers resorting to formal discipline methods 31.6 15.8 5.9 47.1 11.8 21.1% teachers with pupils seated in rows 63.2 73.7 64.7 56.25 76.5 100

and the use of apparatus in the first year, a focuson developing a repertoire of teaching methodsin the second year, and a focus on lessons plan-ning and self-evaluation in the third year. Bydeveloping a network of subject-interest commit-

tees, the active participation of teachers in pro-gramme implementation and management wasalso promoted.

In each year of the study, ten schools (referredto as a ‘phase’) were selected, on the basis of work-

194 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

shop attendance, to receive eight day-long ‘class-room support’ visits spread over one year. Duringvisits, the author worked on a one-to-one basiswith teachers in timetabled science classes. Usu-ally, he spent two hour-long lessons with each ofup to three teachers per visit. Initially teachersoften requested demonstration lessons on problem-atic topics. Subsequent visits increasingly empha-sised cooperative planning and team teaching. Dur-ing the second or third months of support, theauthor facilitated the drafting of ‘school scienceteaching policies’, through group discussion,focusing on two simple questions: ‘What is ourvision of a good science lesson?’ and ‘What is ourvision of a school where science is promoted?’ Thepolicies were useful in providing realistic sharedaims that teachers felt commitment to. As monthspassed, some more skilled teachers developed apreference for being observed teaching lessons oftheir own devising. Each visit was concluded witha debriefing discussion.

3. Research into the impact of coaching

PSP’s InSET methods developed largely in iso-lation from the influence of InSET projects in othercountries. However, the emergence and develop-ment of ‘classroom support’ in PSP has parallelsin projects worldwide. There is a strong affinitybetween what PSP refers to as ‘classroom support’and what other prominent authors, such as Joyceand Showers (1980, 1988) call ‘coaching’.

The coaching of teaching occurs in the work-place following initial training. Coaching pro-vides support for the community of teachersattempting to master new skills, provides techni-cal feedback on the congruence of practice trialswith ideal performance, and provides com-panionship and collegial problem-solving asnew skills are integrated with existing behaviorsand implemented in the instructional setting(Joyce and Showers, 1988, p. 69).

These authors’ extensive synthesis of research intothe characteristics of effective InSET remains

among the most widely quoted on this topic. Withspecific reference to coaching, they have con-cluded that:

1. “Coached teachers generally practice new stra-tegies more frequently and develop greater skillin the actual moves of the teaching strategy thando uncoached teachers who have experiencedidentical initial training…”

2. “In our studies, coached teachers used theirnewly learned strategies more appropriatelythan uncoached teachers in terms of their owninstructional objectives and the theories of spe-cific models of teaching…”

3. “Coached teachers exhibited greater long-termretention of knowledge about, and skill with,strategies in which they had been coached and,as a group, increased the appropriateness of useof new teaching models over time....” (Joyceand Showers, 1988, pp. 88–90)

These authors have shown that to bring a newmodel of teaching of only medium complexityunder control requires twenty or twenty-five trialsin the classroom. During this period, innovationsare particularly vulnerable because teachers’ per-formance is awkward and anxiety is at its height,yet the need for tangible benefit is also at its great-est. Several other commentators have noted anapparent regression in even experienced teacherswhen faced with complex instructional inno-vations, which can strip away their self-perceptionof expertise and make them highly dependent onexternal support (e.g. Hall and Loucks, 1978;Meverech, 1995). Coaching seems to alleviate thissituation by allowing the risk of innovation to beshared.

“A crucial condition for nurturing reflection ina practicum setting is that of establishing a cli-mate of trust and a non-defensive posture on thepart of both the novice teacher and the super-visor. This condition is essential because thenovice has to be able to experiment in as risk-free an environment as possible” (MacKinnon,1988 p. 133).

The above conclusions, regarding the importanceof coaching, were mainly derived from North

195S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

American research. However, they are consistentwith numerous other reviews of InSET evaluationin both developed countries (e.g. Bolam, 1987;Veenman et al., 1994) and developing countries(e.g. Greenland, 1983; Avalos, 1985; Andrews etal., 1990; Dalin, 1994; Little et al., 1994). Fore-most among relevant studies in developing coun-tries is perhaps Dalin’s “How Schools ImproveProject” (Dalin, 1994). Based on a survey of 300World Bank sponsored projects, throughout thedeveloping world (Verspoor, 1989), Dalin selectedthree primary education improvement projects inColombia, Ethiopia and Bangladesh that hadenjoyed sustainable success for more than 15years. These projects were subjected to intensivestudy in order to establish determinants of theirsuccess. Findings underlined the importance ofschool-based InSET.

“Reforms depend on a permanent and locallyavailable in-service teacher training system andan effective system of supervision and support.All three systems have a combination of trainingand supervision locally available as a regularpart of the school work” (Dalin, 1994, p. xii).

4. Theoretical perspectives on coaching

This author is struck by the consistency of thefindings cited above with a social constructivistview of adult learning. This school of thoughtmay be traced back to Vygotsky’s work in Russiaduring the 1920s and 1930s which underlined theimportance of the role of social setting and inter-action in the learning of higher mental functions(see Vygotsky, 1978, 1986 and reviews byWertsch, 1985; Daniels, 1996). Though his ownresearch originally referred to children, through‘activity theory’ (Kozulin, 1996), Vygotskianconcepts have been extended to adult professionallearning (e.g. Scribner and Sachs, 1991; Martin,1993).

Vygotsky proposed that acquiring complexlearning involves sequential activity on two lev-els, namely: the inter-psychological (betweenpeople) and the intra-psychological (within the

individual), but he emphasised the importance ofthe first.

“The social dimension of consciousness is pri-mary in time and in fact. The individual dimen-sion of consciousness is derivative and second-ary” (Vygotsky, cited Wertsch, 1985, p. 66)

Vygotsky developed the concept of the “Zone ofProximal Development” (ZPD) to describe thecharacteristics of effective social interaction duringcomplex learning. He defined the ZPD as the dis-tance between:

“… actual developmental level as determined byindependent problem solving and the higherlevel of potential development as determinedthrough problem solving under adult guidanceor in collaboration with more capable peers…the dynamic region of sensitivity in which thetransition from interpsychological to intrapsych-ological can be made” (Vygotsky cited inWertsch, 1985, p. 67)

The ZPD concept emphasises the importance ofcollaboration between novices and more skilledindividuals in the learning of complex skills. Theindividual attention offered during coaching per-mits such a focus on activities that are beyond theteacher’s normal repertoire of skills, but withintheir capabilities with assistance. Like other formsof instructional scaffolding (Wood et al., 1976),coaching is temporary, adjustable and removedwhen there is no longer a need for it. Coachingduring InSET can be viewed as an attempt to pro-vide such a social context for learning that situatesInSET within the ZPD.

A further development of social constructivismthat also illuminates the seeming necessity forclassroom-based coaching is the ‘theory of situatedlearning’ (Rogoff, 1990). This is based on a bodyof research suggesting that

“knowledge is adapted to the settings, purposes,and tasks to which it is applied. Consequentlyif we want students to learn and retain knowl-edge in a form that makes it usable for appli-cation, we need to make it possible for them to

196 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

develop the knowledge in the natural setting,using methods and tasks suited to that setting”(Good and Brophy, 1995, p. 193).

The message here is that new teaching methods aremost effectively acquired by engaging in authentictasks in authentic settings.

5. Research design and methodology

This study may be seen as testing the assertionsof Joyce and Showers (1988) regarding the natureof effective InSET in a South African setting.However, the original motivation for the researchwas pragmatic. Since the first democratic electionsin South Africa in 1994 there has been a declinein corporate funding for non-governmental organ-isations (NGOs) like PSP. Internal evaluationshave therefore come to emphasise the gathering ofsummative output data, as hard decisions of prior-itisation and organisational survival are being made(Morphet, 1996). Coaching is a labour-intensiveform of InSET and needs justification in this fund-ing environment. This study was thereforedesigned to assess the ‘value added’ by coaching interms of observable changes in teachers’ classroompractice. To this end, three specific hypotheseswere framed for testing:

Hypothesis 1 “Teachers that have participatedin PSP InSET use different methods to thosethat have not”Hypothesis 2 “Teachers change methods morereadily if they participate in both classroomsupport and workshops, than if they participatein workshops only”.Hypothesis 3 “Changes in teaching methodsare sustainable after support is withdrawn”.

The author employed an observational studywith a quasi-experimental design, cross-refer-enced with a battery of ethnographic instru-ments, including interviews and diaries. Whilerecognising the widely discussed limitations ofexperimental designs in educational research,this author holds that they are still appropriatewhere a simple causal relationship is being tested(Soltis, 1984; Shulman, 1986). PSP’s InSET

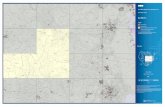

implementation design in Madadeni presentedthe opportunity to make observations of theclassroom practice of comparable groups of tea-chers, before and after defined InSET experi-ences. Fig. 1 describes InSET implementationand the programme of observation designed toevaluate it.

Hypothesis 1was tested by comparing methodsused by PSP teachers with a control group of non-PSP teachers (comparison 15 Phase 0 versusPhases 1.2, 2.2 and 3).

Hypothesis 2was tested through the followingcomparisons

I Firstly, within Phase 2, each teacher’s perform-ance was compared before and after support(comparison 2a5 Phase 2.1 versus Phase 2.2).

I Secondly, Phase 3 teachers who had workshopsonly, were compared with teachers who hadboth workshops and support during the sameperiod (comparison 2b5 Phase 3 versus Phases1.2 and 2.2).

I Thirdly the control group was compared withteachers who had both workshops and support(comparison 2c5 Phase 0 versus Phases 1.2and 2.2).

I Fourthly the control group was compared withteachers who had workshops only (comparison2d 5 Phase 0 versus Phase 3).

Hypothesis 3was tested by comparing the per-formance of Phase 1 teachers as they completedclassroom support with their performance 14months later (comparison 35 Phase 1.1 versusPhase 1.2).

The main observation instrument, developed bythe author, was the ‘Shared Criteria ObservationSchedule’ (SCOS) and its accompanying post-observation interview schedule. Its design wasbased on operationalising 46 ‘shared criteria’ forquality teaching, agreed by teachers when drafting‘school science teaching policies’. In their policies,teachers articulated goals that they understood ona rhetorical level, yet had not mastered in practice.If one accepts the following alternative definitionof the ZPD as

“the distance between understood knowledge, asprovided by instruction, and active knowledge,

197S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Fig. 1. The timing of implementation and observation. ‘X’ denotes participation in workshops, ‘Y’ participation in classroom supportand ‘O’ formal observations. The lower case ‘x’ in the control group indicates that these teachers had little or no exposure toworkshops. Vertical lines represent the end of each cycle of classroom support. The dotted lines separating each phase indicate thatschool conditions in each phase were broadly comparable, though they were not equated by randomisation.

as owned by the individual” (Lave andWenger, 1996)

then SCOS may be seen as an attempting to collectdata focusing on teachers’ ZPD.

Observation items in SCOS yielded four categ-ories of data:

I Dichotomous items—noting if an event, behav-iour, etc. was observed or not; e.g. whetherpupils performed practical work.

I Evaluation items—rating performance on a five-point scale; e.g. how skillfully a teacher conduc-ted a practical demonstration.

I Counts; e.g. the average size of pupil groups.I Free written descriptions not amenable to stat-

istical analysis.

In some cases, observation items required littleobserver-inference (e.g. recording on a checklistwhether or not a conspicuous event like practicalwork had occurred). In other cases a consider-able inference was required (e.g. in rating on afive-point scale the degree to which pupilsappeared to be interested in the lesson). Duringthe piloting of this schedule the wording and for-mat of high inference items was honed for inter-observer reliability through three drafts. Thiswas done to ensure that the author did not encodehigh inference items in an idiosyncratic manner,

despite the fact that all observations were ulti-mately to be conducted by the author himself.For all 5-point rating scales the mean inter-observer discrepancy across all items was calcu-lated as follows.

Total difference Observer 16 Observer 2across all observation items

Total number of observation items

In the final draft of the schedule, for the 17 obser-vation items inviting judgement on a 5-point ratingscale, the mean inter-observer discrepancy acrossa series of seven lessons was 0.51. In this case theco-observer was a South African Zulu-speakingeducation specialist.

The observation study proceeded according tothe timetable described in Fig. 1. The authorattempted to observe a sample of one lesson fromeach of two teachers in each of the ten schoolsparticipating in each phase. This represented 80%of all possible teachers participating in the coach-ing programme and was the maximum numberpossible within the time and resources available forthe study. In cases where there were three teachersin a school who had participated in the programme,the choice of two to be observed was an opport-unity sample based on minimising disruption to theschool timetable. In negotiating access, the author

198 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

explained to teachers that the observations serveda dual purpose. Firstly they were an integral partof the classroom support programme, providing abaseline for work at the start of support, and clos-ure at the end. Secondly observation was explainedas an integral part of programme evaluation. Tea-chers were assured of confidentiality.

The pooled data from each observation groupwere amenable to comparison using standard stat-istical tests of significance:

I Chi-squared test for significance of change inunpaired dichotomous data

I McNemar test for significance of change inpaired dichotomous data

I T-test for significance of change in unpairedscores, counts or percentages

I Paired t-test for significance of change in pairedscores, counts or percentages.

Most statistical tests were conducted on com-puter using the programme “Statview 1.03”. Thesingle exception was the McNemar test, which isnot a feature of this programme and was computedmanually. One possible weakness of this analysiswas that no test was made of whether the datamatched the assumptions upon which the t-testrests, i.e. that the data are sampled from normallydistributed populations of equal variance. How-ever, in defense of this approach, the author citesthe work of Boneau (1960), whose investigationsfound that the validity of the t-test remains remark-ably robust, even in the face of violations of theseunderpinning assumptions.

These statistical tests were used as a crude ‘fil-ter’ to highlight significant differences betweengroups. For each of the group comparisons listed,a significance test was computed for each of the200 items of the SCOS observation schedules.This analysis showed with regard to which‘shared criteria’ the observation groups differed.The author was aware that an unknown numberof the significant statistical tests would be a pro-duct of random variation. Conversely, given thesmall sample size, if an item did not yield a sig-nificant difference, this was not treated as con-clusive evidence that there was no change in tea-chers’ practice. Subtle changes or strategies thatwere only used occasionally were not easily

registered by this method. All results were inter-preted in concert with the extensiveaccompanying ethnographic evidence, collectedover three years of participant observation duringclassroom support visits to schools.

Before presenting results, it is worth pausing toemphasise that this study should be classified as‘quasi-experimental’ (Campbell and Stanley,1963), rather than experimental, because itcompromised the experimental ideal in a numberof ways, the most notable of which are declaredhere.

I Methods of classroom support were refined overtime. Phase 1 and phase 2 were therefore notexposed to exactly the same classroom supportinput.

I Phases were not constituted by random selec-tion, rather on the basis of workshop attendanceand geographical distribution of schools.

I The control group was not constituted randomly,but rather by an opportunity sample of compara-ble schools that did not participate in PSP.

I The control group was constituted post-hoc andonly observed once.

To compensate for the lack of randomisation,data were gathered to assess the comparability ofobservation groups with respect to a multiplicityof potentially confounding contextual variables(Table 1). These data were subjected to parallelstatistical comparisons to those for SCOS items.If a significant difference between groups in acontextual variable was found, analysis was con-ducted to ascertain if that variable was signifi-cantly associated with any aspects of teachingstyle. If an observation item had been so con-founded, and this applied to less than 5% ofitems, then it was omitted from the results presen-tation below.

6. Result of the SCOS observation study

The statistical analysis of data from SCOSinvolved the manipulation of data from six separ-ate observation groups referred to in Fig. 1 asobservations 1.1, 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 3, and 0. Aninspection of the means presented in Table 2 may

199S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

provide the reader with an indication of teachingmethods that prevailed in each of the observationgroups. Six separate series of statistical compari-sons were conducted on these data, describedabove as comparisons 1, 2a, 2b, 2c, 2d and 3.Each series of comparisons involved the compu-tation of a separate statistical test of statisticalsignificance for each of 200 observation itemsencoded in SCOS. Space obviously does not per-mit the reproduction of all this data here. Theauthor has therefore selected 26 key observationitems to report in detail. The means and samplesizes of each observation group are presented inTable 2 and the values of significance tests arepresented in Table 3. Additionally with respect toeach of the six series of statistical comparisons,a brief written summary is offered of significantdifferences (at the 5% level) across all the 200observations items. Those readers seeking greaterdetail are referred to the original research docu-mentation (Harvey, 1997).

6.1. Findings regarding Hypothesis 1

(Comparison 1: Phase 0 versus Phases 1.2, 2.2and 3).

Hypothesis 1 was sustained. There was indeeda clear difference in teaching methods betweenPSP and non-PSP teachers that represented animprovement in quality as defined by the ‘sharedcriteria’.

PSP teachers were more focused in their aimsand more likely to achieve those aims. They weremore versatile in the range of teaching strategiesthat they used. More practical and activity-basedlearning took place, and these activities were morecomplex. Lesson content had greater relevance topupils’ everyday lives, and was judged moreappropriate to their ability levels. Pupils contrib-uted more of their own experience and knowledgeto lessons. More attention was paid to developingEnglish language skills through structured langu-age activity. Pupils did more talking and writingin English in whole sentences. PSP teachers usedZulu more often, and for a wider range of pur-poses. They employed a wider range of oral ques-tioning methods and provided more feedback,especially in the correction of written classwork.

Science lessons were on average longer, permittinga wider range of activities. Pupils were less likelyto sit in rows.

Some aspects of teaching style, however, provedresistant to change. The only scientific processskills that were practiced more often in PSPclassrooms were observation and the manipulationof apparatus. While more practical work occurred,it was valued by teachers primarily as a means ofdemonstrating scientific principles in a memorableway, and not as a means to develop process skills.While pupils contributed more to lessons, they stillrarely asked the teacher questions and rarelyshowed any other forms of initiative.

6.2. Findings regarding Hypothesis 2

Findings also support hypothesis 2. Teacherschange their teaching methods more readily if theyparticipated in both classroom support and work-shops than if they had workshops only. Indeed thegains of attending workshops only were often neg-ligible.

Comparisons 2a and 2b produced a consistentpicture. In comparison with teachers who partici-pated in workshops only, supported teachers wereclearer in their plans and more likely to fulfilthese aims. They used a wider variety of teachingstrategies, and kept pupils more active. Pupilswere more likely to manipulate apparatus. Therewere also marked differences in how languagewas used in supported classes. Supported teach-ers used a wider range of strategies to introducevocabulary and a wider range of strategies tostructure English usage. Pupils were more likelyto speak English in whole sentences and morelikely to engage in written work. At the sametime teachers were also more likely to use Zuluand permit the use of Zulu by pupils. Supportedteachers also used a wider range of questioningand assessment strategies.

However comparisons 2a and 2b also revealedsome aspects of practice that proved resistant tochange. There was no evidence of an overallincrease in groupwork. Likewise pupils did not usea wider range of scientific process kills. Further-more, supported pupils were not more likely to askquestions or show other forms of initiative. Sup-

200 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Table 3Statistical comparison of selected SCOS observation items

Item/Description Statistical comparison

Preparation 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3 (paired)(paired)

Teachers expressed aims in terms of process skills (D) 0.11 0.50 0.12 0.05 0.02 0.25Teachers prepared resources in advance (D) 4.47* 0.25 0.04 4.46* 1.30 0.00

Presentation 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3Teachers sought pupils’ existing knowledge (D) 8.91** 0.50 3.84* 12.06*** 0.83 0.75Teachers used visual aids (D) 2.15 0.00 1.60 3.67 0.01 0.00Teachers made factual error (D) 0.04 0.00 0.06 0.02 0.01 4.0*Estimated % lesson time spent on teacher-talk -2.42* 1.30 0.36 2.26* 1.93 0.63Teachers led practical demonstration (D) 0.13 0.17 0.07 0.09 0.0 0.00Teachers’ skill with apparatus (rated 1-5) 1.18 20.21 1.19 1.35 0.32 2.0Lessons summarised at conclusion (D) 1.76 3.20 6.60* 5.31* 0.001 0.00Logical sequence of lesson (rated 12 5) 1.78 20.72 1.64 2.29* 0.44 0.18

Pupil Activity 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3Written work observed (D) 4.50* 4.00* 0.43 4.84* 0.92 0.00Practical work was observed (D) 7.5** 1.5 2.53 9.85** 1.71 3.27Group work was observed (D) 6.15** 0.25 0.50 6.76** 1.91 0.17

Language 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3> 5 pupils spoke original English sentence (D) 4.14* 0.17 0.43 4.84* 0.92 5.14*> 5 pupils wrote original English sentence (D) 0.10 0.50 0.01 0.05 0.18 0.00

Teacher used Zulu at least once in lesson (D) 3.60 0.00 1.19 5.01* 0.25 0.00Pupils used Zulu at least once in class discussion (D) 0.82 4.00* 2.21 1.99 0.05 0.25

Questioning and Assessment 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3Number of oral questioning strategies counted 1.9323.48** 1.01 2.09* 1.05 20.72Estimated % of pupils answering individually 1.5 0.30 0.41 1.44 0.9020.09Pupils asked own question (D) 0.54 0.00 0.00 0.61 0.01 1.125Conclusion evaluated understanding (D) 0.02 0.25 1.80 0.45 0.06 0.25Individual marking of books (D) 1.23 6.13* 3.99* 2.92 0.01 0.00Girls and boys contributed equally in oral work (D) 0.09 0.00 0.09 0.218 0.17 0.5

Classroom Management 1 2a 2b 2c 2d 3Time management (rated 1–5) 1.387 0.49 1.85 1.83 0.17 0.21Teachers resorted to formal discipline methods (D) 7.65 5.14* 1.30 0.19 0.09 0.8Teachers with pupils seated in rows (D) 5.89* 0.00 0.36 7.10** 2.92 0.17

Table 3 displays values of tests of significance. Items marked ‘D’ are dichotomous and were compared using a chi-squared test fornon-paired data (comparisons 1, 2b, 2c and 2d) and the McNemar test for paired data (comparisons 2a and 3). All other itemscompared continuous numerical values by means of the unpaired t-tests (comparisons 1, 2b, 2c and 2d) and paired t-test (comparisons2a and 3). Levels of significance are indicated using asterisks. ‘*’ represents 5% significance and ‘**’ represents 1% significanceand ‘***’ represents 0.1% significance.

ported teachers were more likely to resort to disci-pline methods, which may reflect problems ofmaintaining control when employing new teachingmethods in crowded classrooms.

Comparison 2c provided clear evidence of theeffectiveness of the whole package of PSP InSET.Compared to non-PSP teachers, supported PSP tea-chers were clearer in their planning, more logical

201S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

in their progression, and used a wider range ofteaching methods. They brought their lessons toclearer conclusions. Pupils were more likely tolearn through self-activity in practical and groupwork. Presentation was likely to be more relevantto pupils’ everyday experiences and they werelikely to contribute more to lessons. Teachers werelikely to use a wider range of language strategiesto structure contributions in English. Pupils weremore likely to speak English in whole sentences,and more written work took place. Zulu was usedfor a wider range of purposes by the teacher. Les-sons were likely to have higher cognitive demand,with teachers asking a wider range of questions andexpecting pupils to employ a wider range of pro-cess skills. Supported teachers were also morelikely to use a wider range of assessment strategies.

Again, certain anticipated advances were notdemonstrated in this comparison. Supported teach-ers were not judged to be more skillful in theirhandling of apparatus, though this may reflect thefact that they attempted practical activities with ahigher degree of difficulty. Once again there wasno significant increase in the asking of questionsby pupils.

Comparison 2d showed that teachers who onlyreceived workshops remained remarkably similarto the control group of teachers who received noInSET at all. Workshops alone produced fewchanges detectable by the present methods ofanalysis. Those significant changes that weredetected related to teachers’ command of subjectknowledge. Accompanying ethnographic dataattest that a small minority of unsupported teachersdid change, though this proportion was not largeenough to be detectable once the data for phase 3had been pooled.

Accompanying interviews revealed that coach-ing was valued by teachers for the followingreasons:

1. Providing a model of practice.“I was able to see different approaches to intro-duction. I was able to see how to ask differenttypes of questions and how to get childreninterested by asking them what they thoughtwould happen. You were able to demonstrate

teaching methods” (“Masondo” quoted inHarvey, 1997, p. 206).

2. Providing counseling on contextual implemen-tation problems.“This has made the teachers feel more easywith science. You don’t come as an inspectorbut you come to share” (“Hlatshwayo” quotedin Harvey, 1997, p. 206).

3. Providing motivation to both teachers andpupils.“You always do your best for a visitor”(“Ndaba” quoted in Harvey, 1997, p. 206).

4. Heightening the credibility of PSP as an organ-isation that understood teachers’ problems firsthand.“Classroom support helps you to understandthe problems that we face in classrooms firsthand. It helps you help us” (“Dube” quoted inHarvey, 1997, p. 206).

6.3. Findings regarding Hypothesis 3

This study provided only limited evidence forsustainability of changes attributable to PSPInSET. Teachers maintained most gains for 14months after classroom support was withdrawn.This is true of the promotion of the use of Englishspoken in whole sentences and strategies toencourage pupil participation in lessons. Therewas, however, also evidence of regression concern-ing the frequency with which pupils engaged inpractical work. It was likely that this was relatedto a decline in the condition of the science kit.

In this study teachers still had regular contactwith PSP. The social network, promoted throughteachers’ committees and workshops, reinforcednew norms of practice. This analysis says nothingof how sustainable the gains of PSP InSET wouldbe in the absence of any ongoing contact. It alsosays nothing about how far into the future sus-tainability can be extrapolated. It is one thing totalk of sustainability over a 14-month period, andquite another to talk of it over a period of severalyears. This issue of sustainability, and the con-ditions necessary for it demands further research.

202 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

7. Implications of findings for planning InSETin developing countries

This study supports the applicability of the con-clusions of Joyce and Showers (1988) to SouthAfrica. The image of effective InSET portrayed isone in which it is essential to furnish an appropri-ate social context for the collaborative testing, vali-dation, and adoption of new teaching methods.

The conclusion that coaching may be a prerequi-site for change is alarming, given South Africa’sstretched education budget and the crisis in post-election NGO funding. Coaching is expensive andlabour-intensive. At 1994 prices, it cost PSP120 000 Rands per year (then £21 000), includingall salaries, transport and operating expenses, tokeep one implementer in the field. Given the sheernumber of schools in need, it is impossible toenvisage PSP reaching more than a small pro-portion of schools nationwide with this model inthe foreseeable future. There is therefore a needto find cost-effective alternative ways of deliveringsupport, while remembering that it cannot be pro-vided by just anyone.

Interviews with Madadeni teachers revealed thateffective coaching depends on an open and trustingrelationship between teachers and the implementer.For this very reason Joyce and Showers (1988);Fullan (1991); Scho¨n (1988) have all drawn thesame conclusion, regarding who can best providesupport.

“I, as others, believe that peer and supervisorytracks for development should be separated asclearly as possible from decision-making pro-cedures for termination, promotion and the like”(Fullan, 1991, p. 325).

PSP’s NGO status places its implementers in anideal position to provide this service, since theyare completely dissociated from managerial powerstructures. They can develop a purposeful, yet con-fidential relationship, in which teachers can experi-ment at no risk.

We need to ask however, whether there areothers within the education system in a position toassume this relationship. In theory, existing ‘sub-ject advisors’ could be sufficiently impartial, but in

practice, they are often distrusted by teachersbecause they participate in school inspection. Ifthey are to provide support then this must change.Another problem is that they are stretched toothinly on the ground. Each may be expected tosupervise several hundred schools. One interestinginitiative that PSP is involved with, may test theplausibility of using subject advisors to providesupport.

Another model being investigated, notably inthe Eastern Cape, where both the geographicalextent and development needs are considerable,is the concept of ‘nodal development’. Here PSPwould service a given area quite intensively.Departmental officials, such as teacher supportfacilitators or subject advisors would be invitedto participate with PSP at its ‘node’ and thenreplicate the operation at their own bases wherethe PSP would hope to give on-site support tothe officials. (Glover in PSP, 1996).

The results of experiences like this need to beclosely documented. The strategy has successfulprecedents though. There are several examples invarious developing countries of school improve-ment projects leading to a shift in the approach ofeducational support staff from coercive to support-ive. (see Dalin, 1994; Shaeffer, 1994).

Another much-talked-about option for providingmore classroom-based support is the establishmentof a cadre of ‘leader teachers’, as promotionalposts. These teachers then offer pedagogical sup-port within their schools or school clusters.

In several provinces, notably in Gauteng, agroup of Lead Teachers is being developed. It ishoped that these teachers, with continued butdecreasing levels of support from the PSP, willeventually take over as change agents amongstother teachers in their localities. These teacherswould be most effective if they were to becomethe ‘classroom based subject advisors’ mooted inthe ANC’s education policy framework documentof 1994 (Glover in PSP, 1996).

This is a promising avenue for taking PSP’swork and other InSET initiatives to a nationalscale. Similar strategies have achieved success incountries as diverse as Indonesia, Zambia and

203S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Guatemala (see Little et al., 1994). However, aswith any form of cascade model there is the riskof ‘dilution’ if the ‘leader teachers’ themselvesare not adequately trained, supported, or super-vised (Peacock, 1994). The experience of otherprojects e.g. Breakthrough to Setswana in Bots-wana (Peacock and Morakaladi, 1995), alsoshows the importance of institutionalising clearcareer paths for such ‘leader teachers’. Initiativeslike the one in Gauteng need to be closely docu-mented.

This shift in emphasis from direct contact withall teachers to contact with ‘leader teachers’necessitates a shift in the role of InSET providerslike PSP. A new InSET curriculum will be neededfor ‘leader teachers’, which focuses not only onensuring a command of activity-based teachingmethods, but also a command of workshop andclassroom support, and other InSET techniques.The selection of these ‘leader teachers’ will also bea crucial issue. They will need the same qualitiesrequired by an effective PSP implementer. Fore-most among these may be:

I A sound understanding of subject matter.I A command of activity-base science teaching

methods.I The ability to clearly articulate and share this

understanding.I The ability to elicit the trust and enthusiastic

participation of colleagues.I The ability to reflect and problem-solve, in order

to develop local models of practice,I The ability to work independently.

These are quite stringent criteria, but such teachersdo exist, many of whom have developed throughexisting programmes like PSP.

The move towards ‘leader teachers’ in SouthAfrica is paralleled by international movestowards more mutual support for teachers. In theUSA, Showers and Joyce (1996) have turnedtheir attention to peer coaching as a means ofsupporting the implementation of new strategies.Their work suggests that valuable support can beprovided between teachers of similar levels ofdevelopment. However, we need to be cautiousin applying this idea to PSP. The experience ofthis study shows that teachers with little experi-

ence of activity-based pedagogy may beespecially dependent on clear models of newpractice. Peer coaching under such circumstancesis surely only possible where at least one partici-pant has a thorough conceptualization of theinnovation. It is probable that peer coaching onlybecomes viable in the middle phases ofimplementation, after the need for modeling haspassed. Trials of peer coaching along the linesproposed by Showers and Joyce (1996) arepresently being conducted in Botswana (Thijsand van den Akker, 1997). The author awaits theresults of this study with some interest.

Given its necessity, the search for cheapermeans of providing coaching is of vital importanceto developing effective InSET strategies indeveloping countries. This was clearly appreciatedby Beeby some years ago when he cautioned theWorld Bank with these words:

“If a country cannot afford such a follow-up ser-vice to achieve a radical advance in teachingmethods, it should consider a less ambitiousform of change. Skimping in follow-up servicesis the most common and, in the end, the mostwasteful reason that large projects fail” (Beeby,1986, p. 40).

It is certainly arguable that in the absence of sup-port, it might be wise to limit educational reform todeveloping the quality of existing teacher-centredmethods rather than attempting a radical shift inunderpinning pedagogy.

References

Andrews, J.H.M. Housego, I.E., Thomas, D.C., 1990. Effectivein-service programs in developing countries: a study ofexpert opinion. In: Rust, V., Dalin, P. (Eds.), Teachers andTeaching in the Developing World. Garland Press, NewYork.

Avalos, B., 1985. Training for better teachers in the ThirdWorld: lessons from research. Teaching and Teacher Edu-cation 1 (4), 289–299.

Beeby, C.E., 1986. The stages of growth in educational systems.In: Heyneman, S.P., White, D.S. (Eds.), The Quality of Edu-cation and Economic Development. Washington, WorldBank.

204 S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Bolam, R. (1987) What is Effective InSET? Paper presented atthe annual members conference of the National Foundationfor Educational Research in England and Wales, Bristol.

Boneau, C.A., 1960. The effects of violations of assumptionsunderlying the T-Test. Psychological Bulletin 57, 49–64.

Campbell, D.T., Stanley, J.C., 1963. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research on teaching. In: Gage,N.L. (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching. RandMcNally, Chicago.

Dalin, P., 1994. How Schools Improve. IMTEC, London.Daniels, H., 1996. An Introduction to Vygotsky. Routledge,

London.Fullan, M., 1991. The New Meaning of Educational Change.

Cassel Education, London.Good, T.L., Brophy, J., 1995. Contemporary Educational Psy-

chology. Longman, New York.Greenland, J., 1983. In-Service Training of Primary Teachers

in Africa. Macmillan, London.Hall, G.E., Loucks, S., 1978. Teachers concerns as a basis for

facilitating and personalising staff development. TeachersCollege Record 80, 36–53.

Harvey, S.P., 1997. Primary Science InSET in South Africa: AnEvaluation of Classroom Support, unpublished Ph.D. thesis,Exeter University.

Hofmeyer, J., Hall, G., 1996. The National Teacher EducationAudit Synthesis Report. Danida, Johannesburg.

Joyce, B., Showers, B., 1980. Improving in-service training: themessages of research. Educational Leadership 37, 379–385.

Joyce, B., Showers, B., 1988. Student Achievement ThroughStaff Development. Longman, New York.

Kozulin, A., 1996. The concept of activity in Soviet psy-chology. In: Daniels, H. (Ed.), An Introduction to Vygotsky.Routledge, London, pp. 99–123.

Lave, U., Wenger, E., 1996. Practice, person, social world. In:Daniels, H. (Ed.), An Introduction to Vygotsky. Routledge,London, pp. 143–151.

Lewin, K.M., 1992. Science Education in Developing Coun-tries: Issues and Perspectives for Planners. Paris, Inter-national Institute for Educational Planning, Unesco.

Little, A., Hoppers, W., Gardner R., 1994. Beyond Jomtien:Implementing Primary Education for All. Macmillan, Lon-don.

MacKinnon, A.M., 1988. Taking Scho¨n’s ideas to a sciencepracticum. In: Grimmet, P.P., Erickson, G.L. (Eds.), Reflec-tion in Teacher Education. Pacific Education Press, Van-couver, pp. 113–136.

Martin, L.M.W., 1993. Understanding teacher change from aVygotskian perspective. In: Kahaney, P., Perry, L., Janang-elo, J. (Eds.), Theoretical and Critical Perspectives onTeacher Change. Ablex Corp., New Jersey, pp. 71–90.

Meverech, Z.R., 1995. Teachers’ paths on the way to and fromthe professional development forum. In: Guskey, T.R., Hub-erman, M. (Eds.), Professional Development in Education:New Paradigms and Practices. Teachers College Press, NewYork, pp. 151–170.

Morphet, A.R., 1987. An Evaluative Study of the Primary

Physical Science Programme. Urban Foundation, Johannes-burg.

Morphet, T., 1996. The survival stakes. In: The Primary ScienceProgramme 1995 Annual Report. PSP Braamfontein.

Ntshingila-Khosa, R., 1994. Teaching in South Africa observedpedagogical practices and teacher’s own meaning. In:Improving Educational Quality Project. Proceeding of aSeminar on Effective Schools, Effective Classrooms 30thMarch 1994. IEQ, Durban.

Peacock, A., 1994. The in-service training of primary teachersin science in Namibia: models and practice constraints.Southern African Journal of Mathematics and Science Edu-cation 1, 21–28.

Peacock, A., Morakaladi, M., 1995. Jaanong ke kgona go balale go kwala: beginning to evaluate ‘Breakthrough’ in Bots-wana. Research Papers in Education 10 (3), 401–421.

Potter, C., Moodie, P., 1991. National Evaluation Report. In:Potter, C., Moodie, P. (Eds.), The Urban Foundation Pri-mary Science Programme: National Evaluation Report. Uni-versity of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

PSP, 1996. Primary Science Programme Annual Report 1995.PSP, Braamfontein.

Raubenheimer, C.D., 1992. An emerging approach to teacherdevelopment: who drives the bus? Perspectives in Education14 (1), 67–80.

Rogoff, B., 1990. Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Devel-opment in Social Context. Oxford University Press, NewYork.

Schon, D.A., 1988. Coaching reflective teaching. In: Grimmett,P.P., Erickson, G.L. (Eds.), Reflection in Teacher Education.Pacific Education Press, Vancouver, pp. 19–29.

Showers, B., Joyce, B., 1996. The evolution of peer coaching.Educational Leadership 53, 12–16.

Scribner, S., Sachs, P., 1991. Knowledge acquisition at work.Institute on Education and the Economy Brief 2, 1–4.

Shaeffer, S., 1994. Collaborating for educational change. In:Little, A., Hoppers, W., Gardner, R. (Eds.), Beyond Jom-tien: Implementing Primary Education for All. Macmillan,London, pp. 187–210.

Shulman, L.S., 1986. Paradigms and research programs in thestudy of teaching: a contemporary perspective. In: Wittrock,M. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd Ed. Mac-millan, New York, pp. 3–36.

Soltis, J.S., 1984. On the nature of educational research. Edu-cational Researcher, December, pp. 5–10.

Thijs, A.M., van den Akker, J., 1997. Peer Coaching as a Prom-ising Component of Science Teachers’ Inservice Training?Paper delivered at the 5th Annual Meeting of the SouthernAfrican Association for Research in Mathematics andScience Education, Witwatersrand University, Johannes-burg.

Veenman, S., Van Tulder, M., Voeten, M., 1994. The impactof inservice training on teacher behaviour. Teaching andTeacher Education 10 (3), 303–317.

Verspoor, A., 1989. Pathways to Change: Improving the Qual-ity of Education in Developing Countries. World Bank,Washington DC.

205S. Harvey / Int. J. of Educational Development 19 (1999) 191–205

Vygotsky, L., 1978. Mind in Society: the Development ofHigher Psychological Processes, Harvard University Press,Cambridge MA.

Vygotsky, L., 1986. Thought and Language. MIT Press, Cam-bridge MA.

Wertsch, J.V., 1985. Vygotsky and the Social Formation of theMind. Harvard University Press Cambridge MA.

Wood, D., Bruner, J., Ross, G., 1976. The role of tutoring inproblem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psy-chology and Psychiatry 17, 89–100.