The impact of biopsychosocial factors on quality of life ... · biopsychosocial model for...

Transcript of The impact of biopsychosocial factors on quality of life ... · biopsychosocial model for...

502

British Journal of Health Psychology (2011), 16, 502–527C© 2010 The British Psychological Society

TheBritishPsychologicalSociety

www.wileyonlinelibrary.com

The impact of biopsychosocial factors on qualityof life: Women with primary biliary cirrhosison waiting list and post liver transplantation

Judith N. Lasker1∗, Ellen D. Sogolow2, Lynn M. Short3

and David A. Sass4

1Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA2Englewood, Florida, USA3University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA4Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Objectives. Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is the second most common reasonfor liver transplants among women in the USA. While survival rates are high, thereis evidence of persistent problems post-transplant. This study aimed to identifysignificant contributors to quality of life (QOL) for women with PBC on waiting list(WL) and post-transplant (PT) and compare QOL in each group with US populationnorms.

Design. A cross-sectional, two-group study design was used.

Methods. WL and PT participants were recruited through medical centres andon-line. QOL was measured by the Short Form-36 and an indicator of Social QOLcreated for this study. A biopsychosocial model incorporating demographic, biomedical,psychological, and sociological factors guided choice of variables affecting QOL. Analysesexamined (1) all factors for differences between WL and PT groups, (2) associationbetween factors and QOL outcomes within each group, (3) multivariate regression ofQOL on factors in the model for the sample as a whole, and (4) comparison of QOLoutcomes with national norms.

Results. One hundred women with PBC participated in the study, 25 on WL and75 PT. Group comparisons showed improvement for PT participants in most biomedicaland psychological variables and in QOL outcomes. QOL was related to many, but not all,of the variables in the model. In multivariate analysis, Fatigue, Depression, Coping, andEducation – but not Transplant Status – were identified as indicators of QOL. PhysicalQOL improved significantly after 5 years PT, when it was no longer worse than nationalnorms. Mental QOL remained worse than national norms despite distance in time fromtransplant.

∗Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Judith N. Lasker, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Lehigh University,681 Taylor Street, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA (e-mail: [email protected]).

DOI:10.1348/135910710X527964

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 503

Conclusions. The model proved useful in identifying a range of factors that con-tributed to QOL for women with PBC before and after transplant. Recommendationswere made for clinical practice to improve QOL through a combination of treatmentand self-management.

With the increasing number of people suffering from chronic liver disease (LD) and theimprovement in long-term survival following liver transplantation (LT), considerableresearch has focused on quality of life (QOL) in people with LD, both prior toand following transplant. The present study expanded on this literature by using abiopsychosocial model for understanding contributors to QOL and focusing on a groupof women with the LD primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

Previous QOL research focused on the effects of physical and emotional stateon functioning and the assessment of a patient’s overall well-being from his or herperspective (Raiz & Monroe, 2007). Researchers who studied QOL in the context ofLT convincingly documented dramatic improvements in measures of QOL after LT (DeBona et al., 2000; Gross et al., 1999; Littlefield et al., 1996; Tome, Wells, Said, & Lucey,2008).

Yet, results from post-transplant studies also indicated a wide range of problems.Researchers documented deficits in QOL overall (Bryan et al., 1998). In physicalfunctioning, problems such as fatigue, medication toxicity, metabolic complications,and osteoporosis were noted (Desai et al., 2008). In psychosocial adjustment, problemssuch as adaptation to changed work and family roles and psychological distress (Blanchet al., 2004; Bravata, Olkin, Barnato, Keeffe, & Owens, 1999; Dew et al., 2000; Nickel,Wunsch, & Egle, 2002) were identified.

Tome and colleagues reviewed both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of QOLwith LT. In longitudinal studies that followed patients from before to after LT, theyfound significant improvements. Relative to controls in the general population, theyfound significant deficits in PT populations. They concluded that ‘the perception ofimprovement of QOL after LT may have been overstated’ (p. 569) and recommendedmore attention to female LT recipients, to patients with specific diagnoses, and topsychological health (Tome et al., 2008).

Gutteling, de Man, Busschbach, and Darlington (2007) reviewed studies of QOLamong people with LD (not only transplant related) and concluded that more suchassessments are needed for improving care of people with LD. They pointed out thatfew studies have looked systematically at the factors that affect QOL in this populationand their relative importance (Gutteling et al., 2007).

The present study addressed the gaps identified in these reviews; it focused on agroup of women with the specific diagnosis of PBC and assessed the relative impact ofmany factors on the physical, psychological, and social aspects of QOL. It was cross-sectional but included people who were on a waiting list (WL) as well as those whowere post-transplant (PT). We had several study aims in this research: first, we aimed toprovide a comprehensive examination of the demographic, biomedical, psychological,and sociological factors that were thought to be related to QOL and to see whetherthese differed before and after transplant. The comparison of WL and PT populationspermitted an understanding of what indicators were indeed improved after transplant.While studies cited below each focused on a few factors, no study of LD or of transplantpopulations had taken this comprehensive approach. Second, we aimed to identify whichfactors were related to QOL outcomes, separately by group. Third, we used multivariate

504 Judith N. Lasker et al.

analysis to identify the factors that were most critical for QOL and thus most in need ofclinical and research attention. Fourth, comparison to national norms for QualityMetric’s(2009) Short Form-36 (SF-36), a widely used measure of QOL (Ware, Kosinski, & Dewey,2000) demonstrated the relative status of this population before and after transplant.

Very few studies of QOL in people with LD or after LT considered PBC specifically.Yet among women who had LT in the USA (OPTN, 2009), PBC was the second mostcommon diagnosis (after Hepatitis C). Rannard, Buck, Jones, James, and Jacoby (2004)reviewed all studies that included measurement of QOL in relation to PBC (not specificto transplant) and found only three, all of which focused primarily on the significantimpact of fatigue on QOL. Gross et al. (1999) and Navasa et al. (1996) studied QOLin people with PBC PT, and Poupon, Chretien, Chazouilleres, Poupon, and Chwalow(2004) studied QOL in patients with PBC (non-transplant) compared with a controlpopulation; these studies all focused on biomedical correlates of QOL such as fatigueand disease symptoms. No research addressed either the psychological or sociologicalconcerns or correlates of QOL in people with PBC before or after transplant.

In addition to the frequency of PBC in LT, studies showed that women with PBChave had better survival rates after LT than people with most other aetiologies (Jacobet al., 2008; Maheshwari, Yoo, & Thuluvath, 2004). Thus, patients and their cliniciansreasonably had high expectations for successful recovery following transplant. Yeteven this group had ongoing concerns about organ rejection (Neuberger, 2003) andcomplications (Navasa et al., 1996). Additionally, Sylvestre, Batts, Burgart, Poterucha,and Wiesner (2003) estimated that about 20–25% of patients undergoing LT for PBCwould develop recurrent disease over the ensuing 10 years.

Gershwin and Mackay (2008) described PBC as a slow, progressive disease ofautoimmune aetiology characterized by injury of the intrahepatic bile ducts that couldeventually lead to liver failure. They noted PBC’s strong genetic basis, its frequentassociation with other autoimmune disorders, and the possibility of being triggeredby environmental factors. Diagnosis was based on a combination of clinical features, inparticular, fatigue and pruritus (itching; Lindor et al., 2009).

A review of the literature on PBC concluded that its prevalence was not wellestablished, with wide variability by country and region within a country. Gross andOdin (2008) reported that PBC was a relatively rare disease, with point prevalenceestimates ranging from 11.1 to 128.0 cases per million population; they also consideredit to be increasing in prevalence. Studies noted that affected individuals are usually intheir fifth to seventh decades of life at the time of diagnosis, and 90% were women(Gershwin & Mackay, 2008; Parikh-Patel, Gold, Mackay, & Gershwin, 1999). Despiteevidence of an increased prevalence of PBC, the number of transplants for people withPBC declined somewhat in recent years, most likely due to an improvement in medicalmanagement of the disease symptoms (Milkiewicz, 2008).

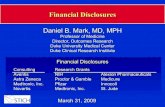

We used a biopsychosocial model to organize into demographic, biomedical, psycho-logical, and sociological categories the factors identified in the literature as importantcorrelates of QOL with chronic disease and transplantation. Efforts to move clinicalresearch and practice towards a biopsychosocial model had been advocated for severaldecades (Engel, 1977; National Research Council, 2001) and were seen in a number offields of medicine (Alonso, 2004; Coughlan, Sheehan, Bunting, Carr, & Crowe, 2004;Lindau, Laumann, Levinson, & Waite, 2003). However, this comprehensive approachhad not been applied to LT populations. Using the model allowed us to explore thebroad range of potential influences on QOL in people with PBC both before and aftertransplant and to see which ones, when analysed together, emerged as most influential

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 505

Demographic Age Education

Psychological Coping Uncertainty Depression Fear/anxiety

Biomedical Transplant status (WL vs. PT)

Fatigue Liver disease symptoms Medication effects

Sociological Social support Stigma Information

Quality of Life SF-36, health-related QOL Social QOL

Figure 1. QOL in PBC: a biopsychosocial model.

in diminishing QOL and, therefore, were in most need of attention. The factors includedin each of the four categories represented the best evidence of what may be relevant forunderstanding variations in QOL (see Figure 1).

DemographicAge and education were commonly used demographic characteristics that had beenshown to affect QOL in other populations, with greater age generally being associatedwith worse QOL and greater education associated with better QOL (Desai et al., 2008;Groessl, Ganiats, & Sarkin, 2006; Sainz-Barriga et al., 2005). Yet Nickel et al.’s (2002)study of LD patients found no effect of age or social class on QOL. In a previous study ofwomen with PBC, ranging from early (1 or 2) to late (3 or 4) stages (Sogolow, Lasker, &Short, 2008), educational level was not associated with QOL, while older people in thesample had better scores on some aspects of QOL than younger people. Thus, the roleof these variables was still unclear and in need of further testing.

BiomedicalSeveral biomedical indicators were shown to be related to QOL in people with LD:Transplant Status (De Bona et al., 2000; Gross et al., 1999; Littlefield et al., 1996; Tomeet al., 2008), Fatigue (Newton, Bhala, Burt, & Jones, 2006; Poupon et al., 2004; Sogolowet al., 2008), LD Symptoms (Gross et al., 1999; Saab et al., 2008), and Medication Effects(Liu, Feurer, Dwyer, Shaffer, & Pinson, 2009; Santos et al., 2008).

PsychologicalQualitative studies identified coping as a key theme for people waiting for transplant(Brown, Sorrell, McClaren, & Creswell, 2006; Vermeulen, Bosma, van der Bij, Koeter, &TenVergert, 2005). However, coping had many different dimensions (Carver, Scheier,& Weintraub, 1989) and thus had a more complex association with QOL than mostmeasures. Some types of coping, such as information seeking (Christensen, Ehlers,

506 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Raichle, Bertolatus, & Lawton, 2000), were associated with better QOL followingtransplant, while others, such as avoidant coping (Myaskovsky et al., 2003), were relatedto worse QOL. A more comprehensive analysis of coping and QOL was needed withtransplant populations.

Uncertainty was also a major concern for people with chronic diseases (Baileyet al., 2009; Johnson, Zautra, & Davis, 2006; Mishel, 1999). Mishel (1981) characterizeduncertainty as a psychological state resulting from an individual’s inability to form acognitive schema – the recognition and classification of stimuli that give meaning to anevent. Uncertainty in relation to illness ‘occurs in situations where the decision makercannot assign definite values to objects and events and/or is unable to accurately predictoutcomes’ (Bailey et al., 2009, p. 138). Thus, uncertainty was a common concern forpeople both awaiting LT (Bjork & Naden, 2008) and PT (Dudley, Chaplin, Clifford, &Mutimer, 2007).

Depression and anxiety were commonly recognized as important contributors toQOL in people with LD and in transplant patients (Blackburn, Freeston, Baker, Jones, &Newton, 2007; Goetzmann et al., 2007; Nickel et al., 2002; van Os et al., 2007).

SociologicalSociological variables were included less often in studies of people with LD or thosewho had undergone transplants. Many studies demonstrated that social support wasan important factor in improved physical and mental health generally (Berkman, Glass,Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001) and in outcomes of chronic illness(Gallant, 2003; Montazeri, 2008) as well as after organ transplant (Cetingok, Hathaway,& Winsett, 2007). Researchers also demonstrated that information about illness helpedchange behaviours associated with chronic illness (Ayers & Kronenfeld, 2007), but theinformation must be appropriate to both patient and context (Brashers, Goldsmith, &Hsieh, 2002; Kiesler & Auerbach, 2006), making assessment of the role of informationin QOL less than straightforward. Finally, stigma was a prominent issue for peoplewith many types of chronic illness (Grytten & Maseide, 2006; Herek, 1990; Levisohn,2002) and was particularly a challenge for people with LD, due to the associations withsubstance abuse (Grundy & Beeching, 2004; Neuberger, 2007).

In this study, we did not test the model as a whole, but rather used it as a heuristicfor identifying factors expected to affect QOL in women with PBC, both while on WLand PT. Our aim was to identify and understand the relative contributions of the manyQOL-related factors so that, with this evidence, strategies to improve care could bedeveloped.

MethodRecruitmentThe sample was recruited from (1) the on-line PBCers Organization, (2) the Universityof Pittsburgh Medical Centre, and (3) the University of Pennsylvania Health System. Theproject was approved by each of the medical school Institutional Review Boards as wellas by Lehigh University’s IRB (ORSP 05/86, 2/25/05) and by the Board of Directors ofthe PBCers Organization.

In previous studies of rare diseases, on-line networks were often excellent sourcesof participants, but they posed a risk of bias due to differences in the kinds of people(generally younger and more educated) who use the Internet and participate in support

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 507

groups (Cotton & Gupta, 2004; Eysenbach & Wyatt, 2002). The medical centres wereincluded to expand the numbers of possible participants and to allow for examining thepotential differences between on-line and medical centre samples.

ProceduresThe PBCers organization, the main on-line resource for support and education of peoplewith PBC, posted announcements about the survey on its website and on two LISTSERVs,one for all people with PBC and the other for people who were PT. Potential participantswere directed to the survey at www.surveymonkey.com. The medical centres, tosafeguard patient confidentiality, contacted potential participants and asked them ifthey would be willing to participate. If interested, individuals returned a postcard to theresearchers requesting that a copy of the survey be mailed to them or that they be calledfor a phone interview. They were also given the option of using a link to the SurveyMonkey website that was specific for their medical centre and included the consentmaterial approved by the centre’s IRB.

MeasuresThe Appendix describes all of the measures used and the sources where furtherinformation about psychometric properties can be found. Standardized instruments wereused for Fatigue, Depression, Coping, Uncertainty, Social Support, Stigma, and QOL. Allof these measures were widely used and validated in other studies. New measures weredeveloped for those variables in the model with no appropriate standardized measures –LD Symptoms, Medication Effects, Fear/Anxiety, Information, and Social QOL.

We developed the measure LD Symptoms based on several sources: (1) the NIDDK-QA measure of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney, used bytransplant centres to track symptoms and other indicators of QOL in people post-LT(Kim et al., 2000), (2) the PBC-40 instrument (Jacoby et al., 2005), and (3) other sourcesdescribing the symptoms of PBC (e.g., Friedman, Keeffe, & Schiff, 2004; Talwalkar &Lindor, 2003). Since there was no established standardized measure of symptoms withPBC before and after transplant, final selection of items for LD Symptoms was madeusing the following criteria: it fit self-report methods (i.e., we did not ask for laboratorydata), and it was either common or salient enough to be known to the respondent. Thismeasure was used in a previous study and found to be significantly associated with QOL;it was revised it slightly for the current study based on the prior results (Sogolow et al.,2008). Similarly, we developed the list of Medication Effects from the Physician’s Desk

Reference descriptions of medications most commonly used by people with PBC bothbefore and after transplant.

Based on our own prior interviews and literature (Nickel et al., 2002), we noted thatfear and anxiety about the future were commonly found both before and after transplant;therefore we asked about five sources of such fear and anxiety – not obtaining a liverwhen needed, infection, organ rejection, pain, and death.

We also asked, ‘How helpful was the information you received from health carepersonnel?’ while on WL. While this measure incorporates both current report for WLgroup and retrospective report for PT group, analyses (not reported here) showed nosignificant differences and thus reassured us that they could be combined.

Finally, we sought to expand the assessment of QOL to include not only physical andmental health and functioning, but also social involvement, which we called Social QOL.

508 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Some studies suggested the difficulties posed by changes in social roles with chronicillness and the necessity of renegotiating roles before and after transplant (Crowley-Matoka, 2005; Nickel et al., 2002; Paris & White-Williams, 2005). The SF-36 has beenused as a measure of Health-Related QOL (e.g., Tome et al., 2008), asking whetherphysical or emotional health interfered with ‘work or other daily activities’ and with‘normal social activities with family, friends, neighbours, or groups’ in the past 4 weeks.We were interested in examining the domains of work, social, and family life separatelyand without specific reference to the impact of health. We, therefore, asked aboutinvolvement in social, family, and work life at the time of the survey.

The new measures were developed based on existing literature and face validityand were pre-tested with volunteers. The current analysis allowed us to establish theirconcurrent and internal consistency reliability. Scale scores resulted from summation ofindividual items, after recoding of some items so that higher scores were consistentlyindicative of a higher level of the construct being studied. The only exception was theBrief COPE, which consisted of 14 factors assessing different coping strategies; Carverindicated that each researcher who wanted to combine factors should use his or herown data (Carver, 1997; see the Results section, for factor analysis of the items).

Statistical analysisData were analysed in SPSS, version 16.0.1 (SPSS for Windows, 2007). All variables inthe model were first compared for the two groups, WL and PT. MANOVA was used toreduce the error involved in multiple t test comparisons. Missing values were imputedusing the linear trend at point procedure. People who did not respond to most items ina scale were not included in analyses of those scales or in regression analyses. Responseto items ranged from 93 to 100%.

Secondly, for each cohort, WL and PT, bivariate relationships between the variablesin the model and QOL were analysed. Third, multiple regression analyses tested therelative importance of the 13 variables in the model in explaining QOL outcomes forthe sample as a whole. In this last analysis, Transplant Status (WL vs. PT) was treatedas one of the indicator variables; the dependent variables were the physical componentsummary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) of the SF-36 and Social QOL.

Finally, SF-36 scores for each group were compared with national norms for womenage 55–64, the age group that included the largest percentage of both cohorts. Sincethese norms were available only by age and sex category, we selected the one that mostnearly matched our sample. To be sure this comparison would be valid, we comparedthe women in our sample who were 55–64 with those who were younger and olderthan that age group and found no differences in the scores on the SF-36 summary scales.

ResultsSampleA total of 100 women with PBC, 25 WL and 75 PT, completed the survey. On-linerespondents were 75, 24 replied by mail, and 1 person was interviewed by phone.Participants were enrolled at one of more than 50 different transplant centres. Theyranged in age from 28 to 79 (mean = 58:45); the majority (82%) of respondents were intheir 50s and 60s. Time since diagnosis ranged from 1 to 31 years, with a mean of 13.5.For the PT group, the time between the surgery and the survey ranged from less than 1year to more than 17 years, with a mean of 5.23 years.

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 509

Through the PBCers site 68 women were recruited. The organization had approx-imately 2,500 members at the time of the study, but not all members were eligible.Some did not have PBC (family members, health professionals, and friends participate aswell), and many of those who did were at early stages of the disease. It was impossibleto know how many people who fit the eligibility criteria were aware of the study,and therefore the response rate was unknown. The 32 women recruited through theirmedical centres represented almost one-third (31.7%) of those who were sent lettersasking them to participate. Of the PBCers participants, 27.9%, compared with 18.8% ofthe medical centre participants, were on the WL (difference not statistically significant).When examining PT participants only, those recruited through the PBCers site wereyounger (mean age 57.2 years for PBCers vs. 61.8 years for those participating via medicalcentres; t = 22:42, p = :018). The PT participants were not significantly different onany of the other variables in the model. Therefore, participants recruited from differentsources were combined for analysis.

Internal consistency reliability of measures usedSee the Appendix for Cronbach’s alpha for all of the measures used in this sample; allhad good internal consistency reliability except Social QOL. When the two measuresof Stigma were compared, the adapted Berger HIV measure had a higher Cronbach’salpha than that of Gralnek’s LDQoL Stigma subscale (see Appendix), very likely dueto the larger number of items in the former. The two measures were also significantlyintercorrelated (r = :603, p = :000). Therefore, further analyses used only the adaptedBerger scale as a measure of Stigma.

The measure of Social QOL – which combined level of involvement in family, social,and work life – had an alpha of .440. It improved considerably (� = :695) when workinvolvement was omitted. Since many participants (59 of the 93 – 63.4% – who respondedto this question) were not working, social and family involvement combined was used asthe measure of Social QOL. Overall, the face validity combined with internal consistencyreliability of the new measures gave us confidence in their usefulness in the currentstudy.

Factor analysis of the Brief COPE with the current sample resulted in two factorsthat we labelled Positive Coping and Negative Coping. Positive Coping included 10of the 14 subscales (e.g., Use of Emotional Support, Positive Reframing, Planning, andHumour), and Negative Coping was composed of the other four (e.g., Denial, Substanceuse, Behavioural disengagement, and Self-blame).

Comparison of WL and PT participants on factors in the modelSee Table 1, for all the measures for WL and PT separately, indicating when these weresignificantly different from each other. As expected, the PT group scored lower on mostmeasures of biomedical and psychological problems and higher on the SF-36.

There were no significant differences between the groups in the demographic factors(Age and Education). Results on the biomedical factors indicated that participantswho had a transplant experienced less severe Fatigue and had significantly fewer LDSymptoms (mean = 1:84 out of 8) compared with the WL group (mean = 5:08). Theonly item that did not differ between WL and PT groups was osteoporosis. In contrast,the total average number of conditions due to Medication Effects (mean = 7:01 for WLand 5.54 for PT, out of 17) did not differ statistically across groups; only 1 out of 13

510 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Table 1. Factors in the model: Means and standard deviations, comparing WL and PT

Medication Effects (pain) was significantly less prevalent PT (27%) compared with WLstatus (64%; See Appendix for lists of L.D. Symptoms and Medication Effects).

Results on psychological factors showed that Uncertainty, Depression, andFear/Anxiety were all significantly lower in the PT group than in the WL group. NeitherPositive nor Negative Coping differed between the groups. There were no differencesin the sociological variables, and all three measures of QOL – PCS, MCS, and Social QOL,were significantly higher among women who were PT.

Biopsychosocial factors and QOL: Bivariate relationshipsSee Table 2, for correlations for each of the factors in the model and the QOL outcomes,for WL and PT separately. For WL, higher scores on the PCS (i.e., better physical QOL)were correlated with fewer Medication Effects, less Fatigue, and less Fear/Anxiety.Higher scores on the MCS (i.e., better mental QOL) were related to older Age, fewerMedication Effects, less Fatigue, and lower Uncertainty and Depression. Higher Social

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 511

Tabl

e2.

Sign

ifica

ntco

rrel

atio

nsof

indi

cato

rva

riab

les

inth

em

odel

with

QO

L,W

L,an

dPT

512 Judith N. Lasker et al.

QOL was related to older Age, fewer LD Symptoms and Medication Effects, less Fatigue,Uncertainty, Depression, and Stigma, and more Social Support.

For the PT group, higher PCS was associated with fewer Medication Effects and lessfatigue. Higher MCS was related to less Education, less Fatigue, less Negative Coping,fewer Medication Effects, lower scores on Depression, Uncertainty, and Fear/Anxiety,and a lower score on Stigma. Better Social QOL was associated with fewer MedicationEffects, less Fatigue, less use of Negative Coping, and less Uncertainty and Depression.

Multiple regressionThe 13 non-QOL factors in the model (see Figure 1) were entered into stepwise linearmultiple regression for the sample as a whole. The results in Table 3 showed that themost important indicators of better PCS were lower Fatigue and higher Depression.The significant positive beta coefficient for Depression found in the multiple regressionwas due to the collinearity between Depression and Fatigue (r = :72), and indicatedthat although Fatigue was a good predictor of the PCS, part of the Fatigue score wasdetermined by the reported Depression.

For the MCS, lower Depression was the only significant indicator of better mentalhealth. Social QOL was predicted by less Fatigue, Education, and Depression and bymore Positive Coping. It is important to note that Transplant Status was not a significantfactor in any of the three outcome measures when all other variables were included.

Comparisons with national normsBoth WL and PT groups reported significant deficits relative to national norms for thesummary scores (See Tables 4 and 5).

DiscussionDifferences between WL and PTResults confirmed substantial improvements with transplant, as expected, but alsoshowed continued deficits relative to national norms. For this discussion, the model’sorganization of variables into five categories was used to examine how each one differsbetween WL and PT.

(1) Demographic. Age and Education were not different between the two groups.The lack of age difference was valuable, as it reduced the possibility that any QOLdifferences between WL and PT were due to normal age-related changes.

(2) Biomedical. Participants reported significantly fewer LD Symptoms PT comparedwith WL. Fatigue also was significantly diminished for the group as a whole, butcontinued to be a problem for many PT participants; 18% scored 80 or higheron the Fatigue Impact Scale (Fisk et al., 1994) indicating an average responseof ‘moderate problem’ for every item in the scale. This was consistent withthe increasing body of evidence that PBC could continue following transplant(Milkiewicz, 2008). Importantly, PT participants reported no fewer MedicationEffects than WL participants. Results highlighted the persistence and salience ofphysical symptoms following transplant.

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 513

Tabl

e3.

Reg

ress

ions

ofph

ysic

alan

dm

enta

lsum

mar

ysc

ores

,SF-

36,o

nin

dica

tor

vari

able

s,to

tals

ampl

e,N

=94

514 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Table 4. QOL (SF-36) summary scales, means, standard deviations, and ranges, comparing people withPBC: Wait list group with US norms

(3) Psychological. Uncertainty, Fear/Anxiety, and Depression were all significantlylower in the PT group. Using the recommended CES-D cut-off score of 16 as anindication of major depression (Pandya, Metz, & Patten, 2005), two-thirds (66.7%)of WL participants qualified, compared with 39.7% PT. While the comparisonindicated a significant improvement, concern remained that almost 40% of PTwomen in this sample had high scores. van Os et al. (2007) cautioned thatinstruments such as the CES-D were not meant to be diagnostic for depression;they concluded that their sample of people with cholestatic LD was no moredepressed than the general population. Yet, scores on the CES-D in this samplewere strongly associated with the MCS measure of QOL. Further study in this areais warranted. Coping strategies did not differ between WL and PT.

(4) Sociological. Social Support, Stigma, and Information given by health care providerswere no different between WL and PT groups, suggesting stability in perceptionof social relationships over time. While the function of others in a social supportnetwork necessarily changed after transplant, the assessment of the value of thosesupport networks remained the same. Further study of the nature of and changesin social support (Lasker, Sogolow, & Sharim, 2005) is needed. Stigma was moredependent on the assumption by others that LD is related to alcoholism or drugabuse (Sogolow, Lasker, Sharim, Weinrieb, & Sass, 2010) than on factors relatedto transplant. With regard to Information, 50% of the WL group and 40% of the

Table 5. QOL (SF-36) summary scales, means, standard deviations, and ranges, comparing people withPBC: Post-transplant group with US norms

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 515

PT groups reported that the information they received while on WL was less than‘very helpful’, suggesting some desire for improved information.

(5) QOL. Results confirmed the research cited earlier on improvements in QOL follow-ing LT. This study added a new dimension, Social QOL, reflecting involvement infamily and social life, and showed an improvement in that area as well.

Elements in the model in relation to QOLAll of the variables, with the exception of Positive Coping and Information, weresignificantly related to at least one of the three QOL measures. Thus the use of abiopsychosocial model allowed us to identify a wide variety of factors that were relatedto QOL. Of particular note was that Medication Effects and Fatigue, both biomedicalvariables, were the only ones in the model related to all three measures of QOL in bothgroups, WL and PT. None of the other types of variables, with the one exception ofFear/Anxiety (which references specific biomedical potentialities such as infection andrejection), was related to PCS score.

It was when we examined MCS and Social QOL that demographic, psychological, andsociological variables showed significant relationships. However, demographic variableswere related in ways that ran counter to expectations. For those in the WL group, olderAge was associated with better MCS and higher Social QOL. This contrasts with Desaiet al.’s (2008) study that found worse QOL in participants over 60; however, the samplein that study ranged in age between 12 and 76 years, a much greater range than ourstudy, which included only adults, only 10% of whom were under 50. Also, our findingwas consistent with the national norms for the MCS, which increased with Age (Wareet al., 2000).

For the PT group, more Education was correlated with less favourable MCS. YetSainz-Barriga et al. (2005) found a protective effect of higher education in their Italianstudy. Perhaps the difference was related to the selective bias in the American transplantsystem for people with medical care coverage, who were on average more educated(Cohen & Martinez, 2009).

Most important influences on QOLIn multivariate analysis, Fatigue and Depression were the most salient factors in QOL.Positive Coping also played a significant independent role in Social QOL and MCS. Itmay be that the challenges of Fatigue and Depression required ongoing coping efforts,and these seemed to enable a level of engagement that was important for improvedQOL. Finally, Education was negatively related to Social QOL in regression analysis. Thisfinding requires further investigation, including attention to social class, which mayinteract with education and outcomes.

Surprisingly, Transplant Status did not have an independent impact on QOL in mul-tivariate analysis, despite transplantation being obviously life-saving. Perhaps TransplantStatus was masking important differences within the PT group, with those who had onlyrecently had a transplant being more similar in physical status to WL than those whohad survived for years. Previous studies (De Bona et al., 2000; Desai et al., 2008; Gubby,1998; Sainz-Barriga et al., 2005) either had not addressed or found conflicting findingswith regard to the impact of time since transplant on QOL. This needs further researchand would help clarify expectations for those anticipating a transplant.

We examined time since transplant in relation to QOL. While it was not related toMCS in this sample, it did correlate significantly with PCS (r = :258, p = :009) and Social

516 Judith N. Lasker et al.

QOL (r = :277, p = :005), indicating improvements over time in these aspects of QOL.To test the possibility that time since transplant would be a better measure of TransplantStatus than the WL–PT distinction, we ran the multivariate analysis again using timesince transplant as a continuous variable, with WL assigned a value of 0. The results didnot change. We also examined SF-36 scores in the PT group to see whether it wouldbe possible to identify a point after which QOL increased substantially in this sample.We concluded from this examination that 5 years PT appeared to be such an importantturning point, with a t test for differences between those who were 5 years or less andthose who were more than 5 years PT being significant for PCS (t = 22:41, p = :018),although not for MCS or Social QOL.

Comparison with national norms showed continued deficits, consistent with previouscross-sectional studies (Tome et al., 2008). Since there were significant differences inPCS in this sample between those who were 5 years or fewer PT and those who weremore than 5 years PT, we compared each group separately with national norms for SF-36.The first group was significantly worse off than national norms; those who were morethan 5 years beyond transplant scored no differently from the general population for thePCS but continued to be lower on the MCS (see Table 6).

Table 6. QOL (SF-36) summary scales, means, standard deviations, and ranges, comparing people withPBC with US norms, 5 years or less PT and more than 5 years PT

Implications for practiceResults emphasized the impact of Fatigue, Depression, and Medication Effects for allelements of QOL, and the important role of Uncertainty, Coping, Fear/Anxiety, andStigma for some elements of QOL. These findings confirmed the importance of takinga comprehensive biopsychosocial approach in clinical care to help people with PBCimprove QOL. Several implications for practice emerged from these results.

FatigueThe underlying disease requires ongoing medical attention. Fatigue, in particular, canbe deadly; Jones et al. (2006) study of people with PBC (without transplant) revealed

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 517

that those with higher levels of fatigue at initial assessment were more likely to die inthe subsequent years. Persistence of fatigue, even PT, should be tracked and treatedwith medication management and physical therapy for strength building to counteractmuscle wasting and deconditioning.

DepressionBecause depression is generally treatable with medications and counselling, the impactof this persistent problem can be diminished. Primary-care clinicians can play a key rolein identifying and responding to depression. The findings of potentially lifelong deficitsin MCS relative to national norms, and the central role of Depression in reducing QOL,require greater attention to the debilitating effects of depression.

Medication effectsIt was notable that there was no reduction PT in participants’ perception of problemscaused by medications, but not surprising given the new medications required forimmune suppression. Efforts to reduce the harmful side-effects of medications to theextent possible can be expected, based on our findings, to improve all three dimensionsof QOL – physical, mental, and social.

Uncertainty and fear/anxietyThese psychological factors were both related to aspects of QOL, reflecting the uneasyreality of life with a serious chronic disease when future developments are unknown andthe meaning of symptoms unclear (Lasker, Sogolow, Olenik, Sass, & Weinrieb, 2010). Theprovision of information and social support can help to alleviate some of the uncertaintyand fear.

Positive copingWhile unrelated to any aspect of QOL in bivariate analysis, Positive Coping emerged asa significant indicator of both MCS and Social QOL in multivariate analysis. Counsellingthat aims to further develop positive coping skills, such as seeking support and planning,and diminish negative coping strategies, such as self-blame and denial, may be helpful.

StigmaBoth MCS and Social QOL were diminished by the perception of being stigmatized as aresult of the disease. Most frequently, concerns were over others believing they werealcoholics or drug addicts, and the source of such comments was often a health careprofessional (Sogolow et al., 2010).

Transplant centre teams, primary-care clinicians, psychologists, and others haveongoing roles in the care of people with PBC. Our results showed the benefits ofproviding satisfactory information before transplant as well as the possible advantages ofhelping patients deal with uncertainty and stigma. Overall, the aim would be to enableand support the self-management knowledge and skills that will enhance QOL in thelong term.

518 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Further, the results indicated that physical health and Social QOL may be expectedto improve over time, but that mental health may not improve or may require greaterattention. The significant variables in the regression analysis (Depression and Fatigue)explained only 24.0% of the variance in PCS, leaving open the question of what otherfactors might help explain variation in this score. For MCS, Depression alone explained58.3% of the variance, indicating the great potential benefits of efforts to reducedepression. Four variables – Fatigue, Depression, Positive Coping, and Education –accounted for 61.4% of the variance in Social QOL. The recommendations above thuscan contribute to improving all elements of QOL.

Limitations

Sample sizeA larger sample of both WL and PT participants would have increased statistical powerand made it possible to detect possible additional statistically significant results. Yet PBCis a relatively rare disease, and obtaining 100 participants during 2 years of intensiverecruitment efforts allowed us to arrive at valuable results. Recruiting nationally forpeople on WL was particularly a challenge, as persons ill enough for WL may have beenless able to participate. Still, the disparity between WL and PT sample sizes reflectedthe nature of the populations. At any given point in time, there were approximately 450women with PBC waiting for transplants in the USA, whereas the cumulative numberof women who had LT during the same period of time as our sample (1989–2007) wasabout 3,500. Even considering likely mortality in the latter group, the proportions in thecurrent study were 25% and 75%, very likely overrepresenting WL relative to PT in thepopulation.

Study designThis study was cross-sectional, comparing WL and PT cohorts. On the plus side, thegroups were derived from the same recruitment sources and were similar in age andeducation. Still, other unmeasured differences between the groups may have confoundedfindings. It would be preferable to examine a single cohort longitudinally, particularlywith respect to the ability to determine causality. Nonetheless, findings from otherstudies that made comparisons with healthy controls were similar to those of singlecohort longitudinal studies (Gershwin & Mackay, 2008; Tome et al., 2008). This studyhad the advantage of including both WL and PT comparison as well as comparison ofeach group with national norms.

Sample biasAlmost all participants (94%) were from within the US transplant centre system, whereeligibility for placement on the WL required financial/insurance resources as well assome level of Positive Coping and availability of Social Support. Therefore, it could havebeen that screening for transplant reduced variation in these results. Additionally, on-linerecruitment, increasingly common in the study of rare diseases, had the potential forselection bias, as it reaches people who have computer access and facility and who havechosen to be part of an on-line support network. Such people have tended to be youngerand more educated (Cotton & Gupta, 2004). The participants who responded to thePBCers announcement were on average younger than the medical centre participants,

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 519

but there was no other difference between the two groups, in Education or in any of theother measures. On-line recruitment yielded a higher percentage of WL participants, anadvantage in reaching a relatively small and very sick population.

MeasuresNot all measures had been established in other studies as valid and reliable, but theresults from this study support further development of such instruments.

ConclusionsThanks to the progress of transplant surgery and immunosuppressants, major improve-ments were made in survival and in reducing the side-effects from medications. Thisstudy also emphasized important improvements in mental health and social activity PT,as women had less anxiety and uncertainty about their futures as well as less fatigue.Yet, comparisons with national norms for women of similar ages showed that thosewho were PT continued to fall short of the well-being of the national female population,especially with regard to mental health. The value of applying a biopsychosocial modelin clinical practice (Alonso, 2004) was demonstrated by the findings that a variety ofbiomedical, psychological, and sociological factors contributed to QOL for women withPBC. Addressing these factors – especially Fatigue and Depression, but also Uncertainty,Stigma, Medication Effects, and Coping – would mean PBC could become a chronicillness that is increasingly well-managed throughout the life-span.

AcknowledgementsMany thanks for their important contributions to this research and paper go to the following:PBCers Organization, Dr Robert Weinrieb, Sirry Alang, Kateland Aller, Dr Andrea DiMartini,Dr Rashida Gray, William Miner, Jennifer Olenik, Carrie Rich, Glenda Rosen, Rebecca Sharim,Anu Paulose, Cynthia Morose, Susan Hansen, and Lehigh University.

ReferencesAlonso, Y. (2004). The biopsychosocial model in medical research: The evolution of the health

concept over the last two decades. Patient Education and Counseling, 53, 239–244. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00146-0

Ayers, S. L., & Kronenfeld, J. J. (2007). Chronic illness and health-seeking information on theInternet. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and

Medicine, 11(3), 327–347.Bailey, D. E., Jr., Landerman, L., Barraso, J., Bixby, P., Mishel, M. H., Muir, A. J., . . . Clipp, E. (2009).

Uncertainty, symptoms, and quality of life in persons with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosomatics,50(2), 138–146. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.50.2.138

Berger, B., Estwing-Ferrans, C., & Lashley, F. R. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV:Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 24(6),518–529. doi:10.1002/nur.10011

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health:Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 843–857. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

520 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Bjork, I. T., & Naden, D. (2008). Patients’ experiences of waiting for a liver transplantation. Nursing

Inquiry, 15(4), 289–298. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00418.xBlackburn, P., Freeston, M., Baker, C. R., Jones, D. E., & Newton, J. L. (2007). The role of

psychological factors in the fatigue of primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver International, 27(5),654–661. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01500.x

Blanch, J., Sureda, B., Flavia, M., Marcos, V., de Pablo, J., De Lazzari, E., . . . Visa, J. (2004). Psychoso-cial adjustment to orthotopic liver transplantation in 266 recipients. Liver Transplantation,10(2), 228–234. doi:10.1002/lt.20076

Brashers, D. E., Goldsmith, D. J., & Hsieh, E. (2002). Information seeking and avoiding in healthcontexts. Human Communication Research, 28(2), 258–271. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00807.x

Bravata, D. M., Olkin, I., Barnato, A. E., Keeffe, E. B., & Owens, D. K. (1999). Health-related qualityof life after liver transplantation: A meta-analysis. Liver Transplantation and Surgery, 5(4),318–331. doi:10.1002/lt.500050404

Brown, J., Sorrell, J. H., McClaren, J., & Creswell, J. W. (2006). Waiting for a liver transplant.Qualitative Health Research, 16(1), 119–136. doi:10.1177/1049732305284011

Bryan, S., Ratcliffe, J., Neuberger, J. M., Burroughs, A. K., Gunson, B. K., & Buxton, M. J. (1998).Health-related quality of life following liver transplantation. Quality of Life Research, 7(2),115–120. doi:10.1023/A:1008849224815

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Considerthe brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92–100. doi:10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401 6

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoreticallybased approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56 , 267–283. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

Cetingok, M., Hathaway, D., & Winsett, R. (2007). Contribution of post-transplant social supportto the quality of life of transplant recipients. Social Work in Health Care, 45(3), 39–56.doi:10.1300/J010v45n03 03

Christensen, A. J., Ehlers, S. L., Raichle, K. A., Bertolatus, J. A., & Lawton, W. J. (2000). Predictingchange in depression following renal transplantation: Effect of patient coping preferences.Health Psychology, 19(4), 348–353. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.19.4.348

Cohen, R. A., & Martinez, M. E. (2009). Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates from

the National Health Interview Survey, 2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrievedfrom http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm

Cotton, S. R., & Gupta, S. S. (2004). Characteristics of online and offline health information seekersand factors that discriminate between them. Social Science and Medicine, 59(9), 1795–1806.doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.020

Coughlan, B., Sheehan, B., Bunting, J., Carr, A., & Crowe, J. (2004). Evaluation of a model ofadjustment to an iatrogenic hepatitis C virus infection. British Journal of Health Psychology,9(Pt. 3), 347–363. doi:10.1348/1359107041557093

Crowley-Matoka, M. (2005). Desperately seeking ‘normal’: The promise and perils of livingwith kidney transplantation. Social Science and Medicine, 61(4), 821–831. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.043

De Bona, M., Ponton, P., Ermani, M., Iemmolo, M., Feltrin, A., Boccagni, P., . . . Burra, P. (2000).The impact of liver disease and medical complications on quality of life and psychologicaldistress before and after liver transplantation. Journal of Hepatology, 33, 609–615. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80012-4

Desai, R., Jamieson, N. V., Gimson, A. E., Watson, C. J., Gibbs, P., Bradley, J. A., & Praseedom, R.K. (2008). Quality of life up to 30 years following liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation,14(10), 1473–1479. doi:10.1002/lt.21561

Dew, M. A., Switzer, G. E., DiMartini, A. F., Matukaitis, J., Fitzgerald, M. G., & Kormos, R. L. (2000).Psychosocial assessments and outcomes in organ transplantation. Progress in Transplantation,10(4), 239–259.

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 521

Dudley, T., Chaplin, D., Clifford, C., & Mutimer, D. J. (2007). Quality of life after liver trans-plantation for hepatitis C infection. Quality of Life Research, 16 , 1299–1308. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9244-y

Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for bioscience. Science,196(4286), 129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

Eysenbach, G., & Wyatt, J. (2002). Using the Internet for surveys and health research. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 4(2), e13. doi:10.2196/jmir.4.2.e13Fisk, J. D., Ritvo, P. G., Ross, L., Haase, D. A., Marrie, T. J., & Schlech, W. F. (1994). Measuring the

functional impact of fatigue: Initial validation of the Fatigue Impact Scale. Clinical Infectious

Diseases, 18(Suppl. 2), 79S–83S.Friedman, L. S., Keeffe, E. B., & Schiff, E. R. (2004). Handbook of liver disease. Edinburgh:

Churchill Livingstone.Gallant, M. P. (2003). The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review

and directions for research. Health Education and Behavior, 30(2), 170–195. doi:10.1177/1090198102251030

Gershwin, M. E., & Mackay, I. R. (2008). The causes of primary biliary cirrhosis: Convenient andinconvenient truths. Hepatology, 47(2), 737–745. doi:10.1002/hep.22042

Goetzmann, L., Klaghofer, R., Wagner-Huber, R., Halter, J., Boehler, A., Muellhaupt, B., . . .Buddeberg, C. (2007). Psychosocial vulnerability predicts psychosocial outcome after an organtransplant: Results of a prospective study with lung, liver, and bone-marrow patients. Journal

of Psychosomatic Research, 62(1), 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.023Gralnek, I. M., Hays, R. D., Kilbourne, A., Rosen, H. R., Keeffe, E. B., Artinian, L., . . . Martin, P.

(2000). Development and evaluation of the liver disease quality of life instrument in personswith advanced chronic liver disease – the LDQOL 1.0. American Journal of Gastroenterology,95(12), 3552–3565.

Groessl, E. J., Ganiats, T. G., & Sarkin, A. J. (2006). Sociodemographic differences in qual-ity of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacoeconomics, 24(2), 109–121. doi:10.2165/00019053-200624020-00002

Gross, C. R., Malinchoc, M., Kim, W. R., Evans, R. W., Wiesner, R. H., Petz, J. L., . . . Dickson,E. R. (1999). Quality of life before and after liver transplantation for cholestatic liver disease.Hepatology, 29(2), 356–364. doi:10.1002/hep.510290229

Gross, R. G., & Odin, J. A. (2008). Recent advances in the epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis.Clinics in Liver Disease, 12, 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.001

Grundy, G., & Beeching, N. (2004). Understanding social stigma in women with hepatitis C.Nursing Standard, 19(4), 35–47.

Grytten, N., & Maseide, P. (2006). ‘When I am together with them I feel more ill.’ The stigma ofmultiple sclerosis experienced in social relationships. Chronic Illness, 2(3), 195–208.

Gubby, L. (1998). Assessment of quality of life and related stressors following liver transplantation.Journal of Transplant Coordination, 8(2), 113–118.

Gutteling, J. J., de Man, R. A., Busschbach, J. J., & Darlington, A. S. (2007). Overview of researchon health-related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Netherlands Journal of

Medicine, 65(7), 227–234.Herek, G. (1990). Illness, stigma and AIDS. In P. Costa & G. R. VandenBos (Eds.), Psychological

aspects of serious illness (pp. 103–150). Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health.Jacob, D. A., Bahra, M., Schmidt, S. C., Schumacher, G., Weimann, A., Neuhaus, P., & Neumann,

U. P. (2008). Mayo risk score for primary biliary cirrhosis: A useful tool for the prediction ofcourse after liver transplantation? Annals of Transplantation, 13(3), 35–42.

Jacoby, A., Rannard, A., Buck, D., Bhala, N., Newton, J. L., James, O. F., & Jones, D. E. (2005).Development, validation, and evaluation of the PBC-40, a disease specific health related qualityof life measure for primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut, 54, 1622–1629. doi:10.1136/ gut.2005.065862

Johnson, L. M., Zautra, A. J., & Davis, M. C. (2006). The role of illness uncertainty on coping withfibromyalgia symptoms. Health Psychology, 25(6), 696–703. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.696

522 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Jones, D. E., Bhala, N., Burt, J., Goldblatt, J., Prince, M., & Newton, J. L. (2006). Four year followup of fatigue in a geographically defined primary biliary cirrhosis patient cohort. Gut, 55(4),536–541. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.080317

Kawachi, I., & Berkman, L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health,78(3), 458–467.

Kiesler, D. J., & Auerbach, S. M. (2006). Optimal matches of patient preferences for information,decision-making and interpersonal behavior: Evidence, models and interventions. Patient

Education and Counseling, 61, 319–341. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.002Kim, W. R., Lindor, K. D., Malinchoc, M., Petz, J. L., Jorgensen, R., & Dickson, E. R. (2000).

Reliability and validity of the NIDDK-QA instrument in the assessment of quality of life inambulatory patients with cholestatic liver disease. Hepatology, 32, 924–929. doi:10.1053/jhep.2000.19067

Lasker, J. N., Sogolow, E. D., Olenik, J. M., Sass, D. A., & Weinrieb, R. M. (2010). Uncertaintyand liver transplantation; Women with primary biliary cirrhosis before and after transplant.Women and Health, 50(4), 1–17.

Lasker, J. N., Sogolow, E. D., & Sharim, R. R. (2005). For better and for worse: Family and friends’responses to chronic liver disease. Illness, Crisis, and Loss, 13(3), 249–266.

Levisohn, P. M. (2002). Understanding stigma. Epilepsy and Behavior, 3(6), 489–490. doi:10.1016/S1525-5050(02)00598-X

Lindau, S., Laumann, E., Levinson, W., & Waite, L. (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplinesin pursuit of health: The interactive biopsychosocial model. Perspectives in Biology and

Medicine, 46(Suppl. 3), S74–S86.Lindor, K. D., Gershwin, M. E., Poupon, R., Kaplan, M., Bergasa, N. V., & Heathcote, E. J. (2009).

Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology, 50(1), 291–308. doi:10.1002/hep.22906Littlefield, C., Abbey, S., Fiducia, D., Cardella, C., Greig, P., Levy, G., . . . Winton, T. (1996). Quality

of life following transplantation of the heart, liver, and lungs. General Hospital Psychiatry,18(Suppl. 6), 36S–47S. doi:10.1016/S0163-8343(96)00082-5

Liu, H., Feurer, I. D., Dwyer, K., Shaffer, D., & Pinson, C. W. (2009). Effects of clinical factors onpsychosocial variables in renal transplant recipients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(12),2585–2596. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05111.x

Maheshwari, A., Yoo, H. Y., & Thuluvath, P. J. (2004). Long-term outcome of liver transplantation inpatients with PSC: A comparative analysis with PBC. American Journal of Gastroenterology,99(3), 538–542. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04050.x

Medical Economics (2003). Physicians’ Desk Reference (58th ed.). Montvale, NJ: ThomsonHealthcare.

Milkiewicz, P. (2008). Liver transplantation in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinical Liver Disease,12(2), 461–472. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.015

Mishel, M. H. (1981). The measurement of uncertainty in illness. Nursing Research, 30(5), 258–263.

Mishel, M. H. (1997). Uncertainty in illness scales manual. Chapel Hill, NC: University of NorthCarolina.

Mishel, M. H. (1999). Uncertainty in chronic illness. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 17,269–294.

Montazeri, A. (2008). Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: A bibliographic reviewof the literature from 1974 to 2007. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research,27, 32. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-27-32

Myaskovsky, L., Dew, M. A., Switzer, G. E., Hall, M., Kormos, R. L., Goycoolea, J. M., . . . McCurry,K. R. (2003). Avoidant coping with health problems is related to poorer quality of life amonglung transplant candidates. Progress in Transplantation, 13(3), 183–192.

National Research Council (2001). New horizons in health: An integrative approach. Washington,DC: National Academy Press.

Navasa, M., Forns, X., Sanchez, V., Andreu, H., Marcos, V., Borras, J. M., . . . Rode’s, J. (1996).Quality of life, major medical complications and hospital service utilization in patients with

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 523

primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantation. Journal of Hepatology, 25(2), 129–134.doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80064-X

Neuberger, J. (2003). Liver transplantation for primary biliary cirrhosis. Autoimmunity Reviews,2(1), 1–7. doi:10.1016/S1568-9972(02)00103-9

Neuberger, J. (2007). Public and professional attitudes to transplanting alcoholic patients. Liver

Transplantation, 13(11), 65–68. doi:10.1002/lt.21337Newton, J. L., Bhala, N., Burt, J., & Jones, D. E. (2006). Characterizations of the associations and

impact of symptoms in primary biliary cirrhosis using a disease specific quality of life measure.Journal of Hepatology, 44(4), 776–783. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.012

Nickel, R., Wunsch, A., & Egle, U. T. (2002). The relevance of anxiety, depression, and coping inpatients after liver transplantation. Liver Transplantation and Surgery, 8(1), 63–71. doi:10.1053/jlts.2002.30332

OPTN Online Database (2009). Retrieved from The Organ Procurement and TransplantationNetwork (OPTN) Web site: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/

Pandya, R., Metz, L., & Patten, S. (2005). Predictive value of the CES-D in detecting depressionamong candidates for disease-modifying multiple sclerosis treatment. Psychosomatics, 46 ,131–134. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.131

Parikh-Patel, A., Gold, E., Mackay, I. R., & Gershwin, M. E. (1999). The geoepidemiology of primarybiliary cirrhosis: Contrasts and comparisons with the spectrum of autoimmune diseases.Clinical Immunology, 91(2), 206–218. doi:10.1006/clim.1999.4690

Paris, W., & White-Williams, C. (2005). Social adaptation after cardiothoracic transplantation: Areview of the literature. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(Suppl. 5), S67–S73.

Poupon, R. E., Chretien, Y., Chazouilleres, O., Poupon, R., & Chwalow, J. (2004). Quality of life inpatients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology, 40(2), 489–494. doi:10.1002/hep.20276

QualityMetric (2009). Retrieved from http://www.qualitymetric.com/WhatWeDo/GenericHealthSurveys/tabid/184/Default.aspx?gclid=CKflsZuMppwCFc5L5QodPnlYkA

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general pop-ulation. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/ 014662167700100306

Raiz, L., & Monroe, J. (2007). Employment post-transplant: A biopsychosocial analysis. Social Work

in Health Care, 45(3), 19–37.Rannard, A., Buck, D., Jones, D. E., James, O. F., & Jacoby, A. (2004). Assessing quality of life

in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology: The Official Clinical

Practice Journal of the American Gastroenterological Association, 2(2), 164–174.Saab, S., Ibrahim, A. B., Surti, B., Durazo, F., Han, S., Yersiz, H., . . . Busuttil, R. W. (2008).

Pretransplant variables associated with quality of life in liver transplant recipients. Liver

International, 1087–1094.Sainz-Barriga, M., Baccarani, U., Scudeller, L., Risaliti, A., Toniutto, P. L., Costa, M. G., . . . Bresadola,

F. (2005). Quality-of-life assessment before and after liver transplantation. Transplantation

Proceedings, 37(6), 2601–2604. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.06.045Santos, J. R., Miyazaki, M. C., Domingos, N. A., Valerio, N. I., Silva, R. F., & Silva, R. C. (2008).

Patients undergoing liver transplantation: Psychosocial characteristics, depressive symptoms,and quality of life. Transplantation Proceedings, 40(3), 802–804. doi:10.1016/j.transpro-ceed.2008.02.059

Sogolow, E. D., Lasker, J. N., Sharim, R., Weinrieb, R. M., & Sass, D. A. (2010). Stigma andliver disease: The case of primary biliary cirrhosis. Illness, Crisis, and Loss, 18(3), 229–254.doi:10.2190/IL.18.3.e

Sogolow, E. D., Lasker, J. N., & Short, L. M. (2008). Fatigue as a major predictor of quality of life inwomen with autoimmune liver disease: The case of primary biliary cirrhosis. Women’s Health

Issues, 18(4), 336–342. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2007.12.005SPSS for Windows (2007). Rel. 16.0.1. Chicago: SPSS.Sylvestre, P. B., Batts, K. P., Burgart, L. J., Poterucha, J. J., & Wiesner, R. H. (2003). Recurrence of

primary biliary cirrhosis after liver transplantation: Histologic estimate of incidence and naturalhistory. Liver Transplantation, 9(10), 1086–1093. doi:10.1053/jlts.2003.50213

524 Judith N. Lasker et al.

Talwalkar, J. A., & Lindor, K. D. (2003). Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet, 362(9377), 53–61.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13808-1

Tome, S., Wells, J. T., Said, A., & Lucey, M. R. (2008). Quality of life after liver transplantation. Asystematic review. Journal of Hepatology, 48, 567–577. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.12.013

van Os, E., van den Broek, W. W., Mulder, P. G. H., ter Borg, P. C. J., Bruijn, J. A., & van Buren, H. R.(2007). Depression in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis.Journal of Hepatology, 46(6), 1099–1103. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.036

Vermeulen, K. M., Bosma, O. H., van der Bij, W., Koeter, G. H., & TenVergert, E. M. (2005). Stress,psychological distress, and coping in patients on the waiting list for lung transplantation:An exploratory study. Transplant International, 18, 954–959. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00169.x

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., & Dewey, J. E. (2000). How to score version two of the SF-36 health

survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric.Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale

of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201 2.

Received 2 December 2009; revised version received 14 July 2010

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 525

Ap

pen

dix

Elem

ents

ofth

em

odel

and

mea

sure

men

tsus

eda

526 Judith N. Lasker et al.A

pp

end

ix

(Con

tinue

d)

QOL with PBC, pre- and post-transplant 527

Ap

pen

dix

(Con

tinue

d)