The Human Side of Medicine

description

Transcript of The Human Side of Medicine

-

THE HUMAN SIDEOF MEDICINE:

Learning What Its Like toBe a Patient and What Its

Like to Be a Physician

Laurence A. Savett, M.D.

AUBURN HOUSE

-

THE HUMAN SIDEOF MEDICINE

-

THE HUMAN SIDEOF MEDICINE

Learning What Its Like to Be a Patient andWhat Its Like to Be a Physician

Laurence A. Savett, M.D.Foreword by William H. Harvey

AUBURN HOUSEWestport, Connecticut London

-

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this book complies with thePermanent Paper Standard issued by the NationalInformation Standards Organization (Z39.481984).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Savett, Laurence A., 1936

The human side of medicine : learning what its like to be a patient and what its

like to be a physician / Laurence A. Savett.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0865693188 (alk. paper)ISBN 0865693196 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Physician and patient. 2. MedicineMiscellanea. 3. Medical care

Miscellanea. I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Physician-Patient Relations. 2. Attitude of Health Personnel.

3. Attitude to Health. 4. Nurse-Patient Relations. 5. Patientspsychology.

W 62 S266h 2002]

R727.3.S355 2002

610.696dc21 2001053837

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available.

Copyright 2002 by Laurence A. Savett

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be

reproduced, by any process or technique, without the

express written consent of the publisher.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001053837

ISBN: 0865693188

0865693196 (pbk.)

First published in 2002

Auburn House, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881

An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

www.greenwood.com

-

Copyright Acknowledgments

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission for use of the photograph and

for extensive excerpts from the following material.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. Drug-induced Illness: Causes for Delayed Diagnosis and a Strat-

egy for Early Recognition. Postgraduate Medicine 67, No. 1 (January 1980): 155166. Re-

printed by permission of Postgraduate Medicine.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. Medical Care and Teaching: Stories of Inadequacy, Opportu-

nities for Growth. Primarily Nursing (January/February 1994): 1012. Reprinted by permis-

sion of Creative Nursing.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D., and Susanne G. Savett, M.S.W. Genuine Collaboration: Our

Obligation to Our Patients and to Each Other. Creative Nursing (September/October

1994): 1113. Reprinted by permission of Creative Nursing.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. Dealing with Uncertainty: Yet Another Dimension in Caring

for Our Patients. Creative Nursing (January/February 1995): 1113, 20. Reprinted by per-

mission of Creative Nursing.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. Spirituality and Practice: Stories, Barriers, and Opportunities.

Creative Nursing, No. 4 (1997): 711, 16. Reprinted by permission of Creative Nursing.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. How Can I Keep from Becoming Emotionally Involved? Cre-

ative Nursing, No. 4 (1998): 35. Reprinted by permission of Creative Nursing.

Laurence A. Savett, M.D. Values and Dealing with Change. Creative Nursing, No. 3

(2000): 1113, 15. Reprinted by permission of Creative Nursing.

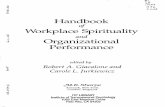

Photograph by Rob Amberg. Home Health Nurse Examining a Patient in His Home, Mad-

ison County, North Carolina. Copyright 1984. Reprinted with permission of Rob

Amberg.

-

FOR SUE

AND

FOR ALEX AND THE NEXT GENERATION

-

Teach your children diligently.

Deuteronomy 6:7

I swear . . . that I will fulfill . . . this oath and covenant: . . . to give a

share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my

sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and the pupils who

have . . . taken this oath according to the medical law.

The Hippocratic Oath

May I never see in the patient anything but a fellow creature in pain.

Physicians oath, attributed to Maimonides

-

Contents

Tables xv

Foreword by William H. Harvey, Ph.D. xvii

Acknowledgments xix

Introduction: Defining the Human Side of Medicine andIdentifying the Audience xxv

Part I. What Its Like to Be a Patient

1. Medical Care Starts with the Patients Story 3

2. Learning from End-of-Life Stories 19

3. Time 27

4. Learning from Patients Experiences 31

5. Learning from Students Experiences 37

6. Learning about Uncertainty 43

7. Learning How Patients Handle Illness 51

Part II. What Its Like to Be a Physician

8. A Day in the Life of a Physician 59

-

9. The Medical History 71

10. Diagnosis: How Physicians Reason 81

11. Treatment and Prognosis 93

12. Medicine Is a Collaborative Profession 97

13. Rituals 109

14. Language and Communication 111

15. What Can Go Wrong 121

16. The Physician as Professional 131

17. Values and Dealing with Change 143

18. Becoming a Physician: The Evolution of a Career 151

Part III. The Doctor-Patient Relationship

19. The Qualities of the Doctor-Patient Relationship 163

20. What Can Go Wrong with the Doctor-PatientRelationship 173

21. Addressing Some of the Myths about the Doctor-PatientRelationship 179

Part IV. The Human Side of Medicine: Bringing It All Together

22. Another Look at a Day in the Life of a Physician 187

Part V. Teaching the Human Side of Medicine

23. Teaching the Human Side of Medicine 217

Part VI. Summing Up

24. Fashioning the Best System of Medical Care Possible:What Would Be Ideal for the Patient; What Would BeIdeal for the Physician 229

25. Epilogue and My Personal Journey 239

Appendix: Outline of the Seminar in the Human Side of MedicineCourse at Macalester College 247

Notes 253

xii Contents

-

Selected Bibliography 259

Index 261

Contents xiii

-

Tables

Table 10.1 Using the History as the First Step in theDifferential Diagnosis of Right Lower AbdominalPain (in Case 1) 84

Table 10.2 Using the History as the First Step in theDifferential Diagnosis of Change in Mental Status(in Case 2) 87

Table 10.3 Differential Diagnosis of Change in Mental Status(in Case 3) 91

Table 19.1 Comparison of Some Qualities of Appendicitis andMetastatic Breast Cancer 167

Table 20.1 Congestive Heart Failure: Symptoms andDifferential Diagnosis 177

Table 20.2 Difficult Patient: Symptoms and DifferentialDiagnosis 177

Table 23.1 Teaching Principles of Reasoning Simultaneouslywith Information about Specific Problems andDiseases 223

-

Foreword

Dr. Laurence Savett has had a respected career as a practicing physicianand medical school teacher. Now retired from active practice, he has dedi-cated his considerable abilities and energies as an advisor, teacher, andmentor to premedical undergraduates at several institutions. This is an un-usual and exciting role for a physician.

Drawing on all these experiences, he has written a most informativebook, The Human Side of Medicine: Learning What Its Like to Be a Patient andWhat Its Like to Be a Physician. I enjoyed reading it, and it should be consid-ered required reading for anyone considering a career in medicine. Thebook is a primer for pre-professional students, including those who are in-terested but unsure about medicine and those who are firmly committed. Itis also a book for medical students and residents, for their teachers and ad-visors, and for professionals and other staff who work with physicians andpatients. It is an important book for patients, who, as Dr. Savett writes inthe Introduction, should expect both technical skill and humanity fromtheir physicians. I am a strong advocate for responsible patienthood and thisbook reinforces the need for partnering between patient and physician.

Based on many years of practice, Dr. Savett describes what its like to be aphysician, but he details more than the day-to-day tasks performed by thephysician. He writes about the dynamics and the potential fragility of thedoctor-patient relationship. He addresses issues of compassion, empathy,and sensitivity, using examples collected over his long medical career.

-

The case studies are wonderful and revealing: the good and bad deci-sions made, good and bad teaching demonstrated, the rush to judgment un-derlined, and first impulses discouraged without careful thought. Dr.Savetts life experiences are woven into the fabric of the text, giving thebook credibility and warmth.

It is a wonderfully informative book that is all about humanism in medi-cine. It is well titled, and I like the statement that appears in the bookssummarizing chapter: Good medicine does not just happen; it is thought-fully planned and practiced. In this context, Dr. Savetts book focuses onthoughtful and careful observations and on reflections free from precon-ceived biases and prejudices. Emphasis is placed on truly seeing and pro-cessing what one is observing, listening, and then, that rare event, hearingwhat one is listening to. So much of this book is about being a good listener.

This book should be required reading for all medical students, and theyshould read it more than once, at the beginning of their pre-professionaltraining as undergraduates and frequently during their years in medicalschool. Today, far too little emphasis is placed on issues of humanity inmany medical school curricula. Medical school faculty will be grateful forthis text, and they should read it carefully. Advisors who work with under-graduate advisees interested in any area of health care will want to have acopy of this book on their shelves. It is also a useful book around which tobuild a seminar for pre-professional students, where one might address im-portant questions, such as, Is a career in medicine a humanistic careersupported by science or a scientific career supported by humanism?

Thank you, Dr. Savett, for focusing on these important issues of human-ism in medicine. Your book is greatly appreciated.

William H. Harvey, Ph.D.Professor of Biology and Chief Health Services Advisor,

Earlham College, Richmond, IndianaPresident, Central Association of Advisors for the

Health Professions.

xviii Foreword

-

Acknowledgments

Who are your models? Who are your teachers?

A career in medicine is a commitment to lifelong learning. I like to ask

premeds: Who are your models? Who are your teachers? Now I acknowl-

edge my own teachers. Many of them, I am sure, have no idea of the magni-

tude of their influence.I learned from many of my patients, who taught me what textbooks do

not: nuances of how illnesses behave, how best to say things, the languageof compassion, what works and what does not, how people handle toughsituations, and about meaning and spirituality. Their stories and theirwords fill this book. I acknowledge many CanSurmount members who un-selfishly shared their stories with my students. I especially thank CarolLindberg, the coordinator for the St. Paul chapter, who made those con-nections.

I have felt privileged to teach at the University of Minnesota MedicalSchool since 1969 and at Macalester College since 1994. I continue tolearn from my students, and I specifically acknowledge these Macalesterstudents: Alejandro Baigorria, Eric Brown, Robert Carlson, Tierre Chris-ten, Neena Davis, Rebecca Egbert, Cesar Ercole, Paul Evans, Megan Flom,Susannah Ford, Eric Geigle, Marissa Getter, Phung Gip, Laura Goodspeed,Tom Hermanson, Karin Holt, Cara Hummer, Julie Knoll, Nat

-

Kongtahworn, Anthony Koo, Jessica Maddox, Tarra McNally, WamaidMestey-Borges, Caroline Nerhus, Laura Neumann, Anna Person, AimeePowelka, Britta Schoster, Misty Shanahan, Andrea Sternberg, CathleenSteinegger, Phang Thao, Jessica Tobin, Kai Tuominen, Amy Voedisch,and Jeannette Ziegenfuss. Along with many others in the seminar, theyhelped me test, refine, clarify, and critique my thought and concepts. I alsoacknowledge the insights of two from the University of Minnesota MedicalSchool: Henry Riter and Ted Haland.

From Bob Feldman, Mike Glasgow, Ruben Haugen, Lou Lachter, LeonOlenick, Melanie Soucheray, and Chris Volpenone of them physi-ciansI gained insight into the question, What is a professional?

Later I will allude to my parents illnesses. Each of them wrestled with se-rious illness and never gave up. As a participant of their medical dramas, Ilearned from them and from my sister Enid what excellent care andnot-so-good care are, and that illness is a family affair. Other family andfriends have told me stories of fine medical care and shameful neglect;through their eyes, I got more of a picture of what it is like to be a patient orthe family of a patient. Many of their stories appear in the text.

Certain authors influenced my method of practice and teaching. I takespecial note of Robert Coles, whom I have never met. His book, The Call ofStories, and his example, that of a physician teaching at an undergraduatelevel, gave me the idea for my course at Macalester. And his concept of theimportance of story, though not new to me, validated and put into theright words what I had taught for many years.

Years ago I stumbled upon an ad for Medical Choices, Medical Chances:How Patients, Families, and Physicians Can Cope with Uncertainty. The titletantalized me, and reading the book validated another concept I had con-tinually used but never discussed with others. At my invitation, one of theauthors, Harold Bursztajn, came to St. Paul to discuss his insights in an eve-ning seminar for physicians. From time to time through the years, I havesent on to him what my students have written about uncertainty and histext.

My high school history teacher at Utica Free Academy, Frank Mason,showed me that there is more to learn than what is written. His lecturespresented information and concepts beyond the text, and from him Ilearned to examine alternative ways of teaching. For the first time, I real-ized that there were bad teachers, good ones, and really good ones. He wasmy first model of a really good teacher. From Otto Liedke, my German pro-fessor for four years at Hamilton College, I learned the importance of therelationship between the student and the teacher and that teaching goesbeyond mastery of a subject; it involves performing. I sometimes find my-

xx Acknowledgments

-

self copying some of his shtick, as I hear myself saying to a student, as hewould with a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye, Mr. X, you being aperson of great insight, please tell me. . . .

The best teacher I have ever had, Earl Schwartz, has taught every mem-ber of my family, and I continue to learn from him. He commands an audi-ence with his mastery of the subject, his prose, which is like poetry, themanner of his presentation, and his relationship to his students. He re-spects his audience, young or old; he never talks down to them. At times heis very, very funny.

Of all the physicians who influenced me, Irving Cramer, my family doc-tor, had the first and most substantial impact. Whenever I think of the bestin a physician, he is my model.

At the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry,George Engel helped to fashion my approach to patients. He took thehard-to-define qualities of the human side of medicine, described them indetail, refined them as they applied to each patient, taught that thepsychosocial history ought to be part of every transaction, placed thoseskills as a central part of the curriculum, and then modeled it for us byteaching us clinical interviewing. Our first experience with patients,whether it was on a medical or surgical ward, was overseen by him and hiscolleagues in the medicine-psychiatry liaison section of the faculty.

Two of my teachers at Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital wereespecially influential. Lawrence Weed devised the problem-orientedmedical record, actually a system of reasoning, which helped me organizemy diagnostic and therapeutic impressions on paper. That discipline fo-cused my inquiry and pursuit of clues from the patients story and stream-lined my thinking. I used it throughout my career in practice, and it is awonderful teaching tool. V. N. Kapur, a pulmonary specialist, taught mehow to read chest x-rays. Long before the advent of CT scans, he saw cluesin plain x-rays that no one else saw, and he taught me how to discover thoseclues. In providing me a system of approaching an abnormal x-ray in a step-wise fashion, he also taught me to transfer that approach to other clinicalsituations.

My senior associate in Gloucester, Walter ODonnell, a fine primarycare internist, writer, and student of the sociology of medicine, taught methe best way to say difficult things to patients. He relished telling me his pa-tients stories as he signed out to me on a weekend, and he enjoyed hearingabout mine. The maxim 90 percent of patients problems are within theken of 90 percent of most doctors came from him. He also showed me howto run an office efficiently. He dictated all his notes, had his secretary tran-scribe them sequentially and in duplicate, placed them in the patients

Acknowledgments xxi

-

chart, and kept the copy, essentially a diary of his professional day, as a re-source in his writing. Throughout my practice, I followed that example;and a diary of one of my days provides the content of chapters 8 and 22.

It was my special privilege in Gloucester to learn from Warren Babson,the dean of Gloucester medicine, a meticulous surgeon, consummate diag-nostician, and perpetual teacher. I remember vividly the moment when heconsulted on my patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer, beckoned me tothe bedside, and said, Listen to this, a hepatic friction rub, a rare physicalfinding, diagnostic of the intraabdominal perforation I had suspected. Hetaught me about collaboration, about defining the roles of each physicianin the care of their common patient, that sometimes taking a chance intreatment, despite uncertainty, is necessary. I liked to watch him deal softly,firmly, and credibly with patients, colleagues, and hospital staff. His cre-dentials were his experience and his commitment to his patients, to theAddison Gilbert Hospital, and to the community at large.

Gordon Addington, another surgeon, also an ordained minister and for-mer missionary, was my St. Paul physician-soulmate. We shared the care ofmany patients and also shared our views about meaning in medicine andother spiritual matters. I continue to accumulate role models. DenisClohisy, a University of Minnesota orthopedist, sustained my wife and mewith his humanity as we dealt with the pain and the uncertainty of a com-plex illness in 1997.

My friend Vicki Itzkowitz, a writer and editor, helped me define the audi-ence for this book and its content and purpose. She helped me see thateven if the book were never published, nonetheless the writing of thebookthe drafting, revising, recomposingwould be a labor of love andself-discovery. If lifelong learning is an important quality of a career inmedicine and, as a medical school applicant taught me, one dimension oflifelong learning is learning more about yourself, then the writing of thisbook has been an end in itself.

When I was exploring new ways to stimulate myself professionally, myfriend Marie Manthey, a very creative thinker, nurse, administrator,teacher, and consultant, well known for her concept of primary nursing,suggested I write the first of several articles for the journal Creative Nursing.By recruiting me for its editorial board, she enhanced my appreciation ofthe partnership between physicians and nurses.

Many reviewed all or parts of this manuscript. They rewarded me withtheir candor, an important part of any relationship. I thank Ruth Cope,Earl Schwartz, Paul Evans, Lou Lachter, Marie Manthey, WalterODonnell, Vicki Itzkowitz, Jonathan Spira-Savett, Bob Feldman, MarthaPalmer, Chris Bliersbach, and Annie Birnbaum. I thank Gregory

xxii Acknowledgments

-

Vercellotti, Madgetta Dungy, and Ilene Harris from the University of Min-nesota Medical School; Susan Resnik at the University of California, SanDiego, School of Medicine; my colleague prehealth profession advisors atMacelester and the University of St. Thomas, Lin Aanonsen, Jan Serie,Rebecca Hoye, Darlane Kroening, and Charlotte Ovechka; and my fellowadvisors at other institutions, Heidi Lang, William Harvey, Karen Paulsen,and Barbara Huntington.

Lisa Legge and I had collaborated on material for Creative Nursing, andshe consented to review this manuscript critically. She unraveled and re-shaped complicated sentences, helped me sharpen the text and clarify mythoughts, and did so with good humor and respectother qualities of agood relationship. She would be a fine doctor and teacher. I learned a lotfrom her.

David Unowsky helped me focus on the logistics of getting the book intoprint. Through Susan Resnik and Elizabeth Kramer, I met John Harney,who gave me realistic advice about content, length, and marketing andmade the connection with Greenwood Publishing Group. Jane Lerner, myproduction editor at Greenwood, coordinated the task of turning mymanuscript into a finished work and patiently shepherded me through theprocess, no small job.

For the use of his photograph, Home health nurse examining a patientin his home, Madison County, North Carolina, I thank my friend andteacher, Rob Amberg. Rob lives in Madison County and has documentedits rural life over the years with his poignant photographs and sensitivetext.

Through the years, my daughter, Ellen, has kept me humble. Never re-luctant to critique my teaching style, question my views, or shore me upwith the wisdom of a younger person, she helped me examine somelong-held opinions. A skilled librarian, she has pointed me to good re-sources and encouraged me to hone my own research skills. Since he wasvery young, my son, Jon, has stimulated me with his insights, his sense ofhumor, and his intellectual prodding. As a rabbi and high school teacher,he has provided yet another model of good pedagogy and has helped me toexamine the similarities between the doctor-patient relationship and theteacher-student one. Both kids are very good writers. Both take me seri-ously, but not too seriously.

Finally, there is Sue. Through the years, my wife has helped me refinehow I speak with patients and colleagues and struggle with how to establishrapport with patients with whom I am having difficulty. When I have strug-gled in other wayswith a patient in failing health, with relationships, orwith lifes more serious dilemmasshe has helped me sort things out.

Acknowledgments xxiii

-

Much of the wisdom related to dealing with patients comes from the socialwork paradigm, which she helped me understand. Her profession and mineoverlap nicely, and together we now teach first-year medical students. Suetaught me most about relationships; ours continues to grow. Many, manytimes, I tell others, Sue is the best part of me.

xxiv Acknowledgments

-

Introduction: Defining the HumanSide of Medicine and Identifying the

Audience

The patient is the center of the drama.

At a time of great changes in the technology and delivery of medical care,

what is timeless and unchanging for patients and physicians is the human

side of medicine, the nontechnical part. Many feel that unless one is by na-

ture a compassionate and understanding person, that dimension of medi-

cine is hard to teach and hard to learn.Two premises inspired this book and the course of the same name that I

teach at Macalester College, a small nationally known liberal arts collegein St. Paul, Minnesota: that it is as important for a physician to master thehuman side of medicine as its technology and that the human side of medi-cine can be taught. Attending to the human side enhances care. Again andagain, elements of the human side hold the key to diagnosis and treatmentby recognizing the unique qualities of each patient. Attending to the hu-man side of medicine enriches the experience for all those in the caringprofessions.

Some years ago, I was a guest in a class of adult students of a world-re-nowned biblical scholar. When they asked him to eulogize a recently de-ceased colleague, equally well known, they expected high praise. Insteadhe was critical. He didnt leave even one person to carry on his work, hesaid. He created a private language that was not transferable. It was

-

opaque and so it was not useful to others. Transparent knowledge can beused by others and can be transmitted. There are those who do what theydo well, but it is not teachable. He gave solutions but not formulas, and for-mulas can be used by others.

In this book, I reflect on formulas for the human side of medicine,based on over thirty years of practice and of teaching, mentoring, and ad-vising medical students and undergraduates. I describe them so that otherscan use them as students, practitioners, teachers, and informed patients. Isuggest transparent formulas for thoughtful medical interviewing, ex-ploring the psychosocial issues related to illness, addressing uncertainty,collaborating, developing relationships, attending to values, and for inte-grating all of these skills into preparation for a careers worth of good pa-tient care.

The Human Side of Medicine describes what keeps the practice of medi-cine stimulating: not fascinating cases, but fascinating peoplethe bestreason to enter medicine. Attention to the human side is the physiciansbest protection against professional disenchantment. The book validatesthe relationship between physician and patient as crucial to all that tran-spires between them; it is not simply a vestige of the good old days. It inte-grates science and technology with the human side but declares thatknowledge of science is not enough if one is to be a good physician. The hu-man side of medicine is not simply being nice to patients; it is a combina-tion of many dimensions of care, a deliberate, focused, reproducibleprocess. Its elements can be analyzed, and most anything that can be ana-lyzed can be taught. I continued to analyze and learn as I wrote this book.

I know that the human side of medicine can be taught, because I learnedabout it from other physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers,clergyand from patients, an almost infinite number and the real experts.As physicians, we have an obligation to the community of patients, to col-leagues, to prospective physicians, and to teachers to share and teach whatwe do in a way that is attractive, interesting, transmittableand transpar-ent. Then the teacher-student relationship becomes a model for the doc-tor-patient relationship.

THE AUDIENCE

The Human Side of Medicine addresses a primary audience of students al-ready committed to a career in medicine, those just beginning to considerit, those who counsel them, and physicians-in-training in medical schooland residency training programs. It also speaks to experienced physicians,nurses, social workers, clergy, and others in the clinical professions, to those

xxvi Introduction

-

who teach medicine, to those who work with doctors and patients in hospi-tals and physicians offices, and to patients.

The Human Side of Medicine addresses students already committed to acareer in medicine and those beginning to consider it and wondering what it islike. It is a recruiting book, intended to attract talented, compassionatepeople to the profession. Though this is not a book about tactics in apply-ing to medical school, it will enhance the readers understanding of a med-ical career and help the process of applying by focusing the student on theessential elements of being a physician. Among the most importantchoices in life is that of a career and lifes work. In this single choice arecombined our values and aspirations, our self-expectations and assessmentof our talents, uncertainty, consideration of coststime and money, andconcern about how the choice will have impact on our personal and familylife. The choice is, in a word, complex. The choice of a medical career is allof that.

This book is intended to provide fundamental information and perspec-tive about the experience of being a patient and a physician in a way that israrely taught at the undergraduate level, so that students can make an in-formed choice, the first step toward a satisfying career. The book will helpthose who have thought about a medical career for the right reasonsthedesire to serve and the intellectual challengebut declined serious consid-eration for invalid ones. One is that the current system of medical care, es-pecially managed care, intrudes inappropriately on the relationshipbetween patient and physician and the amount of time spent together. Re-gardless of their practice setting, physicians who have always put their pa-tients interest first and never compromised their professional values havepreserved their identity and enthusiasm as caring doctors. Attending to thehuman side of medicine does not take much time, and it is time well spent.The book should help to dispel other myths: that physicians can not have apersonal life and that it takes a genius to be a doctor.

This book is for those who are already learning how to be physicians in medicalschools and residency training programs. For those in the first years of medicalschool, it will provide an ongoing context for learning about the humanside of medicine. For those in the clinical years and the residency beyond, itwill enlarge and reinforce what they have learned. I have set out to write forthem a book full of stories to create a warm anticipation of the joy of a medi-cal career.

This book is for physicians, those in practice or retirement and those who may bestruggling with change or disenchantment. It is directed also to those who neverhad the opportunity to talkreally talkwith a colleague about what it islike to be a physician and the meaning of the career. By validating the physi-

Introduction xxvii

-

cians commitment to the human side of medicine, I hope to reinforce thejoy of recognition and to rekindle that joy for those who, in the midst ofday-to-day pressures, may have forgotten the real reason why they chose thatcareerfor the human side. In the course of this writing, I have, of course,heightened my own joy. The book is meant to model the role of reflection onones career; such an activity can be satisfying and renewing, like a sabbati-cal in place. The book is also meant to encourage physicians to recycle theirexperience by teaching and modeling it for students.

This book is for teachers of medicine, those who are good at it, those who wishthey could do it better, and those who would like to examine what works in teach-ing and what does not. Not many of us who teach medicine have had formaltraining as educators or speak regularly with our fellow teachers about ef-fective techniques. As teachers describe, understand, and reflect on whatthey do in caring for patients and teaching others, they can better critique,sharpen, discard, reproduce, and improve their techniques and teach them.Medical school curricula are often long on teaching disease states and shorton teaching the human side of medicine.

This book is for other professionalsnurses, physical and occupational thera-pists, psychologists, social workers, chaplains and other clergyand staff whowork with patients and their families in hospitals, physicians offices, nursinghomes, and patients homes. By enhancing their appreciation of what it islike to be a patient and a physician, they will see even more clearly the op-portunities to work together and serve patients better.

Finally, this book is for patients. This book will help them recognize goodcare and affirm that they need not choose their physicians either for theirhumanity or for their technical skill; they can expect both. Older patientsremember what it was like to have a physician who knew them well, over along period of time, who appreciated their place in their family and in theircommunity, who asked what was going on in their lives, and who could in-tegrate that knowledge into the decisions made and advice offered. Otherpatients may not know that they can expect both technical excellence andhumanity. By understanding how their physicians work, patients can bemore effective partners in their own care.

This book, in short, is for all of us kindred souls. The goals are commonto us all.

THE PHYSICIAN EXPERIENCE: AN INTRODUCTION

Physicians have the privilege to serve in ways that few careers allow. Pa-tients and their families depend on us, by sharing their burdens and oftenby turning their burdens over to us completely.

xxviii Introduction

-

Being a physician is a joy. The intellectual stimulation of dealing withpeople and their problems, simple and complex, and the variety of chal-lenges is exhilarating. Sobering, too, for patients share the stories of theirlives, given only the simplest of encouragement: How is this for you? orWhats going on in your life? Such questions give them permission to telltheir stories.

Each patient has a story, and few are reluctant to tell it. When I ask,Who do you share your feelings with? many will answer, My wife (or hus-band or uncle or friend), but more than you can imagine will say, Yourethe only person Ive ever told about this.

So being a physicianprivilege and joy asideis a responsibility. If weare to be partly responsible for the physical and psychological problems ofour patients, we must know what we are doing. We must know what to lookfor, how to get the information, how to identify all the issues, how to dis-card the trivial, how to use the technology of medicine (and how to restrainourselves from using it unnecessarily), how to address issues of ethics anduncertainty, and how to integrate all of this information and knowledgequickly into action that serves our patients well.

Physicians are perpetual teachers. We teach our patients; uninformed,they are less likely to follow our instructions. We teach our colleagues also;each consultation, formal or informal, is an opportunity to teach. Many ofus teach in medical schools, residency programs, and a few, like me, in un-dergraduate settings. We are also perpetual students. We learn from ourteachers and our colleagues, from what we read and hear in the medical mi-lieu, from our patients, and from our students. We learn from our experi-ence within and outside of our careers. A career in medicine is acommitment to lifelong learning.

But because medicine is changing, the community faces the hazard thatattention to the human side of medicine may be neglected. Of all the let-ters of appreciation I received from patients during my years of practice, notone thanked me for that great CT scan, that great blood test, or thatgreat surgical referral. Rather, they expressed gratitude for my listening,being present, helping them through difficult times, providing emotionalsupport, and enabling them to understand what was going on and how todeal with itall aspects of the human side of medicine. Patients ought toexpect that from all their physicians.

Many argue that unless one is by nature a compassionate and under-standing person, the human side of medicine is hard to teach. Not so. I be-lieve that exposing undergraduates to that aspect of a medical careershould help attract talented and compassionate people to the professionand provide a context for lifelong learning. I also believe that teaching the

Introduction xxix

-

human side of medicine as a primary, and not incidental, subject in medicalschool and that continuing to emphasize it throughout postgraduate resi-dency training is critical to becoming a good doctor. The community of pa-tients is the ultimate beneficiary. Absent the human side, both patientsand their physicians lose.

I am a primary care physician, an internist trained before the advent ofthe major technologic advances in medicine. I learned medicine at theUniversity of Rochester in upstate New York, a medical school whose cur-riculum was firmly based in the biopsychosocial view of illness. I have hadgood physicians as models. I have been a patient, a concerned family mem-ber, and I am the husband of a talented and compassionate medical socialworker. All of these influences contribute to how I look at the doctor-pa-tient relationship.

I am also a perpetual student. I am accustomed to asking, What did Ilearn from this encounter with the patient? What did I learn from this classthat I taught? From this student? The insights from these sources make mea better physician and teacher.

My ongoing experience as a teacher is threefold. I have taught medicalstudents, interns, and residents for thirty years at the University of Minne-sota, and during most of those years, I have taught small groups of first- andsecond-year medical students in one of their first direct experiences withpatients, as they are beginning to form their habits of practice. Though thecourse was designed to teach them skills in medical interviewing and diag-nosis, I added dimensions emphasizing the human side of medicine. In thelast eight years, I have taught undergraduates at Macalester College. Thecourse is called, Seminar in the Human Side of Medicine: What Its Liketo Be a Patient; What Its Like to Be a Physician. And finally, each day ofmy practice, I taught my patients the meaning and implications of their ill-ness and treatment. One of our roles as physicians is to transmit the best ofwhat we have learned, to build on those lessons, and to preserve the time-less values. A statement in rabbinic literature declares, We may not beable to finish the task; even so, we shouldnt shrink from it.1

My generation of physiciansI am in my 60s and graduated medicalschool in 1961is especially important as a bridge generation. Our teach-ers were educated before the arrival of big medical technologyfiberopticendoscopy, coronary artery catheterization, CT and MRI scanners, evenblood chemistry screening testsand so they relied a great deal on themedical interview, the patients story of illness. They valued it as the entreto the patients diagnosis and treatment and squeezed more informationout of it. They thought things over as much as possible before pressing on tolaboratory work or consultations. They recognized the value of presence.

xxx Introduction

-

Less reliant on technology, they were better listeners. Treatment in thosedays was simpler also. The therapeutic choices often included no treat-ment, simple treatment such as penicillin for infection or digitalis for con-gestive heart failure, time, or rest. There were no intensive care units orextraordinary measures like ventilators, cardiopulmonary resuscitation,and dialysis.

Wherever I practiced, there were always one or two extraordinary physi-cians, people with unique viewpoints and approaches and extra measuresof diagnostic and therapeutic wisdom. Colleagues recognized them as com-munity treasures and resources. When, despite their own best efforts andthose of their consultants, physicians still did not know what was going onwith a patient and what to do next, they turned to one of them. Most of thetime, they came up with the solution to the unsolved diagnostic problemnot by collecting more laboratory data, but simply by reinterviewing thepatient, reviewing the other material, and looking at all the information ina different way. When they taught their method, they did it by thinkingout loud, by making their process transparent.

Similarly, I have had other remarkable teachers, inside and outside ofmedicine, noteworthy not only for what they taught me but also for howthey taught and how they organized and presented their material. Whenthese people, master clinicians and teachers, retired or died, they tookmany of their secrets with them, a loss to the community of patients andphysicians. Would it not have been great for them to have been debriefedand to have had their skills and secrets described, sorted out, and pub-lished?

To a certain extent, this book is my attempt to debrief myself. Not that Iam extraordinary in the way that I have described these others. Nonethe-less, I reflect on these matters, and, through the years, I have kept good re-cords, not only of clinical data, but also of how patients, students, andteachers say things. I have recorded how I say things to patients and stu-dents and what works and does not work.

Lest we forsake the best of the past as we move to the future, we shouldrecognize that medicine, like the Talmud, a compendium of biblical com-mentary and discussion, is built layer upon layer, the result of the com-bined labors of many generations. . . . The creative work of one generationserves as the basis for the creative work of the next.2 . . . [It] is thus the re-corded dialogue of generations of scholars [and] has all the characteristicsof a living dialogue.3 If we do not continually write about, clarify, inte-grate, and carry on the dialogue of medicine, then we do not build onprior knowledge, and we are condemned forever to reinvent the wheel.Our task, as physicians and teachers who appreciate the importance of the

Introduction xxxi

-

human side of medicine, is to preserve those values and techniques and passthem on to our students.

TEACHING THE HUMAN SIDE OF MEDICINE

Many patients, students, and friends have expressed doubt that the hu-man side of medicine can be taught. Either you have it or you dont, theysay. Unequivocally I declare: The human dimensions of medicine andhow to apply that knowledge can be taughtby drawing upon studentsown experiences, by modeling the relationship, and by thoughtful exami-nation of the infinite number of medical transactions.

My undergraduate, semester-long course at Macalester College, Semi-nar in the Human Side of Medicine: What Its Like to Be a Patient; WhatIts Like to Be a Physician, meets in a two-hour weekly session, with dis-cussions, weekly papers, and a term paper. Together the students and I ex-plore the essence of that part of medicine, seen from the standpoint of thepatient and the physician. Let me parse the title of the course.

The course is a seminar, not a lecture course. That means that there is anintimacy between my students and me, which allows for open andopen-ended discussion. Nonetheless, there are a framework and an agendato the discussions, which this book approximates. During the seminarmeetings, we often tell stories from our own lives and use these stories asdata for our discussion.

The human side of medicine: The theme of the course, and of this book, isthat medicine, while technical in many of its methods, is a human profes-sion, about people. While illness may be defined in terms of an abnormalorgan or organ system, it is ultimately about human distress, and the sci-ence of it is only part of the method of inquiry and action. It does not alwayshelp the patient when the physician presents technical information with-out providing context, comfort, compassion, and continuityall humandimensions of medicine.

What its like to be a patient takes priority in the subtitle over what its liketo be a physician. The primary axiom of the course and of my practice andprofessional life is the patient is the center of the drama, not the doctor,not the hospital, not the insurance company or other institution. The taskof the physician is to appreciate what its like to be in the patients situation,to clearly define the patients needs, and then to help the patient meetthose needs. That is where we begin the course.

The composite life of a physician, what its like to be a physician, cannot beignored by anyone considering a career in medicine. Being a physicianmeans dealing not simply with illness but with people with illness, having

xxxii Introduction

-

to interpret and decode their stories in order to define their problems be-fore one can suggest and provide a remedy. That is a very stimulating andsatisfying activity. What its like to be a physician is more than what the doctordoes all day. It means knowing how to plan our day to make best use of time,to integrate our professional and personal lives and provide balance, to setlimits, to attend to our family, and to share some of the emotional burdens.Being a physician is intense work, filled with complex decisions (most ofwhich become second nature with experience), and we can be easily se-duced into allowing our professional activity to overtake our personal life.

We begin the course with a story of one patients experience with illness.To this we add stories from the students experiences, for almost all studentshave had experience with either their own or a close family members en-counter with a more than trivial illness. We learn from stories. Sometimeswe miss all their lessons. Sometimes we unconsciously alter them by howwe listen or how we retell them. But this does not negate the point that oneof the joys and opportunities of being a physician is being privy to storiesand the discovery that is involved.

I like to use the photograph on page xxxiv when I teach the course.Take three minutes to study the photo, I tell the students, and then taketen minutes to write a story about it. All they know for sure is the caption:Home health nurse examining a patient in his home, Madison County,NC. Each of the students stories, of course, is different, focusing variouslyon the man, the woman, the nurse, or all three. The students construct sto-ries of differing acute and chronic illnesses; the mans variouslosseshealth, independence, income, and ultimately life; and the impactof his illness on the man, the woman in the doorway, usually called hiswife, and the nurse. Some notice the photo of the serviceman on thebookshelf in the background, and construct yet another story. Some noticethe walker in the foreground. Others notice the modesty of the dwelling.

After the students read their stories to the whole class, I tell them whatthe phogorapher, Rob Amberg, told me. The woman to the right is themans daughter. He was 94 years old when the photograph was made, andhe had been living with her and her husband for a number of years. Thehome health nurse made regular weekly visits with him. That work is in-credibly rewarding. The nurses play a vital role in our very rural, often iso-lated community, acting not only as interpreters between patients andclinic doctors, but also as a strong social connection. Most of the nurses endup being good friends with their patients. Both the man and his daughterare long gone, and, while Im sure he would be flattered to be thought soyoung, I suspect she would be equally upset to be thought so old,

Introduction xxxiii

-

The photograph is but a moment in these peoples lives. The point of theexercise is to demonstrate that we unconsciously construct stories aboutpeople from scant knowledge of the facts and then draw conclusions fromthose stories. The less we know for sure, the more inaccurate our infer-ences. Especially as physicians and other health care professionals, we needto know as much of the story as possible to make valid decisions and do ourjobs well.

I have set out to write a sweet book, full of patients, students, and physi-cians stories and reflections. It represents the cumulative wisdom of all myteachersmy professors, my colleagues, my family and friends, and my pa-tients and students. Much of what I do and much of who I am as a physicianand teacher is derived from what I have learned from them.

Ill begin chapter 1, after presenting the medical history, by telling a story.Then I will identify the issues, address the role of the doctor-patient relation-ship, and finally ask, What did I learn?

xxxiv Introduction

Home health nurse examining a patient in his home, Madison County, North

Carolina. Shot for Southern Exposure magazine. Photographer: Rob Amberg.Copyright 1984.

-

PART I

WHAT ITS LIKE TO BE A PATIENT

-

Chapter 1

Medical Care Starts with thePatients Story

The story is never over.

One cannot be a good physician without understanding what it is like to bea patient.

THE HISTORY

A 50-year-old physician had chest pains for two months, brought on by exertion andrelieved by rest. His physical examination was normal. A cardiac stress test was posi-tive: Walking on the treadmill reproduced his pain, and the change in the electro-cardiogram pattern indicated that the pain was from coronary insufficiency,impaired circulation of blood to the heart. A coronary angiogram, an x-ray of the ar-teries of the heart, showed multiple areas of coronary artery narrowing. A few dayslater, he had coronary artery bypass surgery. Three days following surgery, he had athree-hour period of extremely rapid heartbeat, a disturbance of cardiac rhythmcalled atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response, associated with chest painand hypotension, a drop in blood pressure; it resolved with treatment. He was dis-charged from the hospital eleven days after the surgery, recovered uneventfully, andreturned to work part-time in ten weeks and full-time six weeks after that.

This medical history, equivalent to a brief oral case presentation or to anote in a patients chart, summarizes the story of a real illness.

-

Is it the whole story? And if not, is it sufficient to describe what the patientand his family went through? And if there is a longer story, is appreciation ofthat saga important in knowing how to care for the patient and his family?

What can we learn from knowing the whole story?

THE STORY

The patient kept a journal of his memories of this period in his life. Hereis the story in his own words.

I had had pain in my lower teeth on vigorous exertion for many years. I recall thateven playing touch football twenty years ago had brought it on. So when I noticedit again, I didnt pay much attention to it. Its simply more of the same, I thought,unlikely to be of consequence.

For two months though, beginning in May, I noticed that besides the pain in myteeth, I would have pain, not severe, high up in my chest and in my left arm withcertain activities such as walking in the park with my son and walking across thestreet from my office to the hospital. The pain would promptly go away, so how se-rious could it be, I thought. To validate that point, I would climb three or fourflights of stairs. Always the last flight would bring on the pain. I would fall asleep atnight thinking about it, wake up in the morning thinking about it, and always sayto myself, Its not my heart. I told no one, not even my wife, in whom I confideeverything.

And then in July, after two months of this, I said to myself, Its not just me whodepends on me, but also my wife and my two children, and My children are bothgoing away in the next two months, one to study abroad for a year and the other toBoston, 1,400 miles away, to start college. If I am really ill, it would be unfair tospring this on them from a distance. And finally, I asked myself, What would Iadvise me if I saw myself as a patient?

So I made an appointment for a stress test to be done two days later. Then I toldmy wife about the pains and the test. And, doing my best to deny that this could beanything serious, on the night before the stress test, I called a friend in Boston totidy up plans for a vacation later that month. I saw my personal physician themorning of the test and told him about my symptoms for the first time. I kept be-lieving that I would pass the test.

The doctor who monitored the test stopped it after two minutes. I knew thatmeant that the test was positive, and she confirmed my fear. I returned to my per-sonal physician who by then had been informed of the results. He prescribed nitro-glycerin to be used in an emergency and arranged for me to see a cardiologist twodays later.

My wife picked me up at the office. I told her the results. My voice broke and Iwept. Later I spoke to my children, telling them for the first time what was goingon.

4 The Human Side of Medicine

-

That evening I told my office partner. The next day I worked and saw patients.Why not? I reasoned. It will be an easy dayno especially difficult problems.But I was preoccupied and couldnt concentrate. At the end of the day, I told mystaff, and again my voice broke. But even then I was tentative about how long Idbe awaythe stress test might be falsely positive.

The next day, Friday, I did not work. With my wife I saw the cardiologist. Thecoronary angiogram had already been arranged for the following Monday, and Iasked that I be the first case of the day, in order to avoid delays or postponement,common occurrences on a busy cardiology service.

Whom else did I tell? My rabbi, with whom I had a close relationship andfriendship. My father, 81, healthy but emotionally vulnerable and living in an-other city. My sister, a nurse, also living elsewhere.

My fathers immediate response was, Ill be there tomorrow. I was annoyedthat he decided without asking me and I asked him not to come until we knew theresults of the angiogram. Later he called back and said, Tell me what you want meto do.

What did I feel? Sadness. Id hate to lose me, I thought. Im a helluva guy.And shame, that I didnt take good enough care of myself, that I wasnt a jock.

The following day, Saturday, I went to our synagogue, a small congregation. Inmy behalf, the rabbi said the special prayer one says for an ill person, asking forhealing of body and healing of spirit. I had mixed feelings about acknowledgingto those gathered that I was not well. On the one hand, I wanted the support of mycongregation; on the other hand, I was embarrassed by my illness.

The next day, I attended a previously scheduled gathering of my wifes family.By then my problem was no secret, and they all gave me their moral support. Onehad had a similar problem with a good outcome. His suggestion: Get anotheropinion.

On Monday, I entered the hospital for the angiogram. A lot was runningthrough my mind. Should I take the pills routinely prescribed before anangiogram? Whats the test really like? Could it harm me? Whats the outcome go-ing to be? The test went easily enough.

Later that day, the cardiologist came to my room to discuss the findings. He toldmy wife and me that there were a number of narrowed arteries and their branches,that the situation was serious, and that he was uncertain if surgery would help. Wewere stunned!

My children, who had been part of this drama since the previous week, hadbeen sent out of my room by the cardiologist for what we thought would be a brieftalk with us. That talk lasted over half an hour. When they returned, they wereoutraged at having been excluded. Dont ever do that again! they said.

The next day the surgeon arrived and said that surgery was an option and thathe could do it. With the cardiologist, I examined my choices. Treatment with med-icine alone would not improve the long-term outlook. Angioplasty, using a bal-loon-tipped catheter to enlarge the areas of narrowing, might be a possible remedybut had its risks. Surgery, though also risky, seemed the best choice.

The Patients Story 5

-

We agreed to proceed with the surgery. Of each of my physicians, the internist,the cardiologist, and the surgeon, I asked for continuity of care, that each wouldsee me daily and be personally available, rather than a surrogate. I did not want de-cisions about my care to be made by someone who did not have a complete per-spective about me medically. I wanted to be looked after by someone who knewwho I was. I did not want too many cooks spoiling the broth. I did not want to feelabandoned. They agreed.

Then I went home to await surgery, scheduled for the following Friday. Again Irequested that I be the first case of the day.

In the interim I arranged my affairs. Though I felt things would turn out well, Iapproached the event by planning for the possibility that I might not survive. Withmy wife and my attorney, a close friend, I reviewed my will, my assets, my personaland office financial matters, and my insurance, and I made sure that my wife hadaccess to all of this material. I was struck by my wifes strength. I wrote individualletters to my wife, to my son and daughter, and to my father and sister. Before thesurgery, I gave each the letter. These were not letters to be opened in the event ofmy death but rather ones to be read immediately (and maybe more than once),expressions of love, affection, and admiration, validating our relationships. I occu-pied myself with many tasks. I faced my mortality.

On Thursday, early in the day before surgery, I checked into the hospital. In thecourse of interviewing me, the admissions clerk inquired about how much cash Iwas carrying: Do you have any money? Never one to pass up a straight line, I an-swered, I make a living.

Always looking at how things can be done better, I found myself silentlycritiquing the nurses presentation as she gave me instructions on how to preparemyself for the surgery and what to expect. To familiarize us all to the surroundingsand to show us what a patient looks like immediately after surgery, the nurse tookmy family and me to the intensive care unit where I would go after surgery. As aphysician, I had been there many times. Now through different eyes, I saw what apatient looked like after surgery: very weak, pale, and hooked up to tubes and aventilator.

My rabbi visited and asked, What do you fear most? My immediate answer,given without thought, was, Dying. It seemed like the right thing to say. But aftera moments reflection, I gave a more honest answer, Coming out of this a differentpersonat the worst, having a stroke, but, short of that, having a different person-ality, losing my sense of humor. I asked him, Whats the appropriate prayer forthis moment? He replied, the Shma, a signature prayer of Judaism, which is adeclaration of faith and belief in God. I had recited this prayer hundreds of timesduring my lifetime, but it took on new and more personal meaning to me this timewhen I once more repeated, And you shall love the Lord your God with all yourheart and These words which I command you shall be in your heart.

That evening, the nurse told me to shower and to scrub my entire body with aspecial soap to minimize the chance of infection after surgery. I scrubbed long andhard, anything I could do to ensure success.

6 The Human Side of Medicine

-

The surgeon had dropped in earlier to talk and answer questions and had toldme to call him at home if I had any further concerns. At 10 p.m., I called him topoint out that I had athletes foot; I had some time ago read a medical article thatsuggested that such a condition, even though minor, risked contamination of thevein that was to be taken from my leg as a bypass graft. Even then I was still person-ally involved in my care. He acknowledged my concern and assured me that hewould pay special attention to the donor vein.

Finally I asked myself, What strengths, what prior experiences could I callupon from my experience of fifty years? I recalled my mothers life and the exam-ple of her courage and equanimity as she dealt with breast cancer. I recalled mydays in college and medical school when, at a certain point in preparing for anexam, I would declare, Ive done all I can do, and I would quit studying. At about10:30 on this night before my surgery, I said to myself, Ive done all I can do. Itstime to relax. This is a new experience for me. Lets see what I can learn from it.

I felt good about myself. I felt that I had made peace with my father and my sis-ter, with whom my relationships were at times volatile. I felt I had lived a good life.I was proud of my marriage and of where my children were in their own lives. I wasat ease and as serene as I have ever been.

On Friday morning, the day of surgery, I was awakened at 5:30, and I showered andscrubbed again. My family arrived, and they accompanied me to the door of the oper-ating room suite. This was the summer of the Iran-Contra hearings in the Congressand among my last words to them, to lighten the moment, were, Reagan knew. AnIV was started, and thats the last thing I remember before waking up after surgery.

At different times during the period of surgery, friends, the hospital director ofnursing, and our rabbi visited my family as they waited at the hospital. It meant agreat deal to them.

My next memory was a nurse saying to me, Dr. X, wake up. I was connected toa ventilator, a number of tubes, and a cardiac monitor, the normal routine. My fam-ily visited, and I asked for a clipboard, pencil, and paper, on which I wrote, Reaganknew, signaling to them, and validating for myself, that I was intellectually intactand my sense of humor was still there.

The next few days brought various treatments and manipulations. Still lookingafter myself, when the tube connecting me to the ventilator was to be removed, Isignaled the anesthesiologist, Be sure to deflate the cuff. I noticed blood on myleg wound dressing and asked the nurse if that was unusual. The nurse said, Morethan we usually see, and that concerned me. Later that day, the surgeon told methat the amount of blood was normal. I had chills and wondered whether they wererelated to one of my medicines. My doctor had the same thought and discontinuedthe drug. In anticipation of the removal of a tube from my chest, I took a codeinepill, and that was the last of the narcotics I required for surgical pain. I coughed fre-quently and used the blow bottles to minimize the risk of lung infection. I helpedto take care of myself.

On Monday, three days after surgery, I no longer needed quite so much observa-tion and was moved to a step-down ward. That evening, I noticed sporadic irregu-

The Patients Story 7

-

larities of my heartbeat and then an abrupt change to a rapid heart rate. An alarmmust have gone off at the nurses desk; she appeared and told me what I alreadyknew. She phoned the cardiologistnot mine, but the one on calland he pre-scribed an intravenous drug. I said, Call Dr. Y [my own cardiologist], and he pre-scribed a different medication. I wondered if the intravenous line was running anddelivering the medicine adequately. I wondered if the nurse would have called mydoctor if I hadnt asked. I wondered if the nurses knew what they were doing. Myheart continued to beat rapidly. One nurse told me my blood pressure was down.

I was rushed back to the intensive care unit. By now I was having pain in myarm. Please ask Dr. Y to come in, I said to the nurse. I still had a part in overseeingmy care. I felt that if I didnt stay involved, harm could occur.

My mind raced. My blood pressure is down and Im having pain; my grafts mustbe closing. I could die. All of this preparation and surgery has been for nothing. Mymain defensesdenial, intellectualization, rationalization, and humorno lon-ger worked. Instead, for the first time, I felt real terror. Afraid to hear the answer, Ihad to ask the doctor, Will I survive? Yes, he answered gently and with reassur-ance, and then he said, Let go. He meant, Relax and let us handle this. But Iwas still figuring, struggling, and trying to make decisions. I wondered if I could diefrom this, if I should ask my wife to come to the hospital for yet more last-minutewords.

Now it was after midnight. Someone from the intensive care unit called mywife. Very much afraid, she struggled with whether or not to come down, felt shecould not share her fears with our children or my father and sister who were stayingwith her, and decided to stay home. She had to deal with other feelings also, for notso long before, she had lost her mother after a long illness and years ago her fatherhad died suddenly from heart disease. Call as often as you want, the nurse toldher. She called frequently, awake all night.

With morphine, other drugs, a blood transfusion to correct the postoperativeanemia, and the passage of time, the abnormal rapid heart rhythm resolved. So didthe pain. The entire episode lasted less than three hours. Nevertheless, it is themost vivid of all my memories, and when I recall those moments and retell thatpart of the story, I often will find myself near tears.

With the shift change at 7 a.m., a new nurse took over my care. On meeting mefor the first time now, she said: Oh! Youve had heart surgery! Youll need to diet!Youll need diet foods! I sell diet foods! I was amused by the absurdity of the situa-tion. Here I was, having just faced what I thought was my impending death, andthis nurse was talking to me about diet foods. In a less generous moment later, Ithought how unaware and thoughtless this person was not to have acknowledgedwhat the night had been like for me.

The rest of the day was uneventful, and the following day I was transferred backto the step-down ward and the same room where the arrhythmia had started. Iwondered if this room was unlucky for me, but I quickly dismissed that thoughtwith, Thats nuts! God would not be so frivolous. And then I settled down to aroutine for the rest of my hospital stay.

8 The Human Side of Medicine

-

Two nurses were primarily responsible for my care, one from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. andanother from 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. Each was competent but had a different style. Onewould check me over and say, Your pulse is 80, your blood pressure is 120 over 80,your lungs are clear in a very businesslike way. The other would do all of that, butalso she would talk with me, inquire about my feelings, and listen. I found myself,after a few days, becoming angry with the first nurse. She never asked, How is itgoing for you? or Whats it like for you? I weighed the pros and cons of speakingto her about this, and ultimately, a day or two before my discharge, I told her whatwas on my mind. I started with a compliment. I appreciate the care youve givenme, I said, and then I told her what I thought was lacking: attention to my feel-ings. She was defensive. I thought that because you are a doctor, you didnt needthat kind of attention, she said. There was always someone in here visiting.(There wasnt.) I told her that the because you are a doctor excuse was actually abigoted statement, for she was judging me not as an individual but as a member of agroup. I was, first of all, a patient and a person, that is, a person in need, and myneeds were the same as other patients.

By the weekend, things were going well, except that I again began to noticetooth pain, similar to what I had noticed before the surgery. What did it mean? Inphysical therapy, I noticed some pattern changes on the EKG and asked the thera-pist about them. She said, The ST segments look better. But no one had said theylooked bad in the first place. More reason to worry.

On the last day, I took another stress test and passed. The uncertainty about thepain in the teeth was resolved again for the moment. Before I left the hospital, Icompleted a questionnaire to test how much I had learned in the cardiac rehabili-tation program, which included a unit on sexual relations and at what interval af-ter surgery I could resume. To test my knowledge, the questionnaire asked, Whencan you have sex? My answer: October 3rd at 3:15 p.m.

I have always told patients who are returning home from a hospital stay that thefirst few days are difficult ones. More than one realizes, a patient depends on thehospital staff for many things, and being home without the extra hands and the re-assurance of the hospital surroundings is an adjustment. And it was for me. On thefirst night, I had to get up several times to urinate, and each time was a majortaskmy wife had to help me out of bed and get me moving. I solved that problemthe next day by sending my son to get a plastic urinal to keep at my bedside. Ineeded my wife to help me to climb stairs and to change positions, the things thatnurses and others had helped with in the hospital.

Two days into my convalescence at home, I developed pain in the left side of mychest and I found that my ability to move air into the blow bottles was much less. Ithought the worst: Maybe I had a pulmonary embolus, a blood clot that had injuredmy lung. But I didnt call my doctor and decided to wait it out. I was back lookingafter myself, being my own doctor. The pain resolved after a few days.

With my wife, I developed a routineeating, walking, napping, and receivingone or two visitors a dayand that schedule took up most of the day. When friendsand family visited over the next few weeks, I found that the quality of the visits and

The Patients Story 9

-

the conversation varied, from talk that was light and inconsequential to conversa-tions that were best of all for me, the opportunity to talk about feelings and sub-stance.

Early on August 23, my birthday, my wife received a phone call informing herthat her cousin, who had been my patient and was only a few years older than I, haddied suddenly of a heart-related problem. When she told me, I wept for the firsttime after surgery. I realized that I cried not only for him but also for myself, a re-lease of accumulated emotion encompassing all that I had gone through over thelast few weeks.

I attended a cardiac rehabilitation group three times a week. I was the youngestand the newest in the group. The therapists were optimistic and encouraging butwould say to me things like, Your blood pressure is up today. Has it been up be-fore? and, pointing to my heart rhythm tracing, Are these irregular beats atrial orventricular in origin? I had to keep reminding them that in this place I was a pa-tient and not the doctor.

I reflected a great deal during this time. I thought about the uncertainties of thefuture. Would the symptoms recur? Would my life be shortened? I recognized that Iwas far more robust than before the surgery. I was more active, and yet I knew therewere things I could not do. It would be foolhardy, I thought, to take canoe trips intothe wilderness. Though I had never done that, that limit symbolized that my illnessplaced restrictions on my life, which had been unrestricted before. During thistime of convalescence, many symptoms came and went without explanation, butduring their presence, I always asked myself, Is this serious? Is this heart painagain?

I found that my wife had many fears also, as she does even now. Early on,when we would walk together and I would pause for a moment, shed ask, Isanything wrong? When I would come home later than expected, she wor-ried. I learned to call if I would be late, and I still do. We had to take care ofeach other.

During the first few weeks after surgery, I found it easy to rationalize givingup many of my usual tasks by saying that I was sick. My wife paid the bills andtook on most of my other responsibilities. I was reluctant to give up that sickstatus but ultimately began to declare myself a well person, and, in mid-Octo-ber, 10 weeks after the surgery, after visiting our daughter in Boston, I returnedto practice for half-days. Six weeks after that, in December, I resumed full-timework.

My greatest concern on returning to work was that my mind would not be asgood. But it worked as well as ever. I found that the greatest stress was the numberof matters competing for my attention. When I had been home, I could concen-trate on one thing at a time and take my time doing it. Now I realized that my work,medical practice, was an extremely complex logistical task, and the necessary tran-sition to that mode of living was my greatest hurdle.

In January, my wife, daughter, and I all flew to Israel, where our son was study-ing, for a family reunion.

10 The Human Side of Medicine

-

WHAT DO WE LEARN FROM THIS STORY? WHATARE SOME OF THE ELEMENTS OF THE HUMAN SIDEOF MEDICINE?

The details of this story provide insights into what happens when some-one recognizes that he is not well, seeks advice, and connects with a physi-cian. The patient counts on accurate diagnosis and wisely chosen therapy;what actually takes place is far more. Unless we understand how compli-cated the process really is, we forgo the opportunity to look at it analyticallyand learn from it.

To teach all of this, I use two paradigms.The first is the biopsychosocial model, central to my education at the Uni-

versity of Rochester, where I learned to see all patients in the context oftheir life stories. Illness does not just happen. Important biological, psycho-logical, and social factorsand often all threecontribute. Part of attend-ing to patients and caring for their illnesses is discovering all the possibleelements of their illnesses; neglecting any part may lead to only a partial so-lution and incomplete care and may delay or prevent recovery.

The second paradigm is a series of five steps, which provide a systematicapproach to looking at each encounter with a patient, to learn from it, andto add to ones experience.

Step 1: the story. The patients story is what really happened and the asso-ciated feelings, emotions, and reflections. It holds most of the clues to diag-nosis and treatment. More than any single laboratory or x-ray test or eventhe physical examination of the patient, the patients story gives broad andvaluable information about what is wrong.

Step 2: the history. Inquiring about the patients story, then editing and re-shaping it into a useful oral and written format, is the process called takingthe history. The product, the medical history, provides the basis for definingthe issues and taking action.

Step 3: the issues. By defining the issues, we explore all the dimensions of amedical problem and not simply the diagnosis. Issues are questions that areraised by the patients story and the history. They include at least the fol-lowing:

What is the diagnosis? Given the diagnosis of coronary heart disease (or diabe-tes, appendicitis, etc.), what additional information do I need to care ade-quately for this patient? Unless we know all the elements of the diagnosis, wecannot completely address treatment and care.

What are the treatment options? Of all the options, what is the best choice?

What is the prognosis; that is, how will it turn out?

The Patients Story 11

-

More often than not, there are additional issues, such as

Why did this happen now?

How will this illness progress, if treated or untreated? Will treatment make a dif-ference?

How will the illness affect the patients self-image?

How will the treatment of this illness affect the patients other illnesses?

What is the impact of this illness on the patients family?

Can the patient afford the treatment?

Are there ethical considerations?

What can go wrong?

Each diagnosis and problem has its own set of issues. If the story and the his-tory are incomplete, then the definition of the issues will be inaccurate andthe actions taken may be neither appropriate nor beneficial.

Step 4: the doctor-patient relationship. The relationship between the patientand the physician facilitates care. In each transaction, physicians shouldask, To what extent can the patient and I use that relationship to enhancecare?

Step 5: What did I learn? Step 5, the most important one in the physiciansprofessional growth, integrates all the other steps. Asking What did Ilearn? allows insight and discovery. What did I learn about the patient,his experience of illness and how he copes, the disease or problem, the pro-cess of obtaining the information from the patient and other sources, aboutwhat can go wrong? What did I learn about myself? Even when an illness isincurable or when one does not get along with a patient, there is much tolearn. When things go badly, it leads to asking other productive questions,What happened? How can I prevent this from happening again? It is theway we learn from experience.

What one learns runs the gamut from the simple to the profound. Here iswhat I learned from this story.

Patients consult a physician at different stages of their illness. The thresholdfor consulting a physician is different because each of us has different per-ceptions of what is going on, different fears, and different defenses. This pa-tient used denial frequently during the early stages of his symptoms,though, as a physician, he should have known better. Other factors pertain.Timing (his children were going away) and the influence of others (Mywife made me make this appointment is a common statement) oftenbreach the threshold for consulting a physician.

12 The Human Side of Medicine

-

The medical history and the story from which it is derived are important. De-spite his having serious underlying heart disease, this patient had a com-pletely normal physical exam. Only the patients story gave the clues to thediagnosis.

For each problem, there are implied questions: What is the cause of thisproblem (the diagnosis)? What is the solution (the treatment)? How is it goingto turn out (the prognosis)? These are some of the technical issues ofmedicine, and the physician must address each of them with each trans-action.

Even with excellent care, things can go wrong. This patient experienceddrug-induced chills and a disorder of heart rhythm. The physicians andnurses promptly recognized and treated each complication of treatment.Drug- and treatment-induced illnesses occur frequently.

Illness has symbolic meaning to patients, and patients have psychological reac-tions to illness. This patient initially felt sadness, shame, and embarrass-ment. Other patients may feel anger, resentment, disappointment,inadequacy, or failure. They may feel that they are being punished for pre-vious missteps. Some see illness as an opportunity for growth. Some feelthat their religion has failed them. Some feel isolated. Recognizing the di-versity of meanings and psychological reactions enables the physician toindividualize care.

Patients have psychological defenses, some healthy and some not so healthy.This patients defenses included the following:

Denial. Its not my heart, he said when he first started having the discomfort,and he tried to reinforce this denial by climbing stairs despite the pain and bypressing on with his vacation plans.