The Human Being as Concrete and Abstract Form in Visual Art : Auguste Rodin, Bodhisattva Maitreya,...

-

Upload

toyin-adepoju -

Category

Documents

-

view

8 -

download

0

description

Transcript of The Human Being as Concrete and Abstract Form in Visual Art : Auguste Rodin, Bodhisattva Maitreya,...

-

Le Penseur by Auguste Rodine Picture by Nancy Steisslinger Panoramio http://www.panoramio.com/photo/1869505

The Human Being as Concrete and Abstract Form in Visual Art Auguste Rodin, Bodhisattva Maitreya, Owusu-Ankomah and Victor Ekpuk Oluwatoyin Vincent Adepoju Compcros Comparative Cognitive Processes and Systems Exploring Every Corner of the Cosmos in Search of Knowledge

-

2

Le Penseur in the Jardin du Muse Rodin, Paris Modeled 1880-1881, enlarged 1902-1904; cast 1919 http://www.rodinmuseum.org/collections/permanent/103355.html Licensed under Attribution via Wikimedia Commons -http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Le_Penseur_in_the_Jardin_du_Mus%C3%A9e_Rodin,_Paris_May_2005.jpg#/media/File:Le_Penseur_in_the_Jardin_du_Mus%C3%A9e_Rodin,_Paris_May_2005.jpg

-

3

A perennial challenge in the visual arts is that of how to depict the human being in reflection. How can the state of methodical or calm contemplation be communicated through a medium that is accessible through the senses, which, most of the time, can grasp only the physical form and not see into the mind? Two of the most famous examples of how this challenge has been met represent suggesting the mental state of a person through the appearance of the body. This suggestion operates through depicting the body in a dynamic stance or in a calm pose. Auguste Rodin's Le Penseur, The Thinker The premier example of the dynamic stance of the body as evoking reflection is French sculptor Auguste Rodin's Le Penseur, The Thinker, in which a seated man is shown with his hand curled in a fist and supporting his chin, as he bends his back slightly, in the classic image of a person in deep thought. His muscles bulge all over his body in concentrated tension as if they are about to burst from his form. The bulging muscles suggest dynamism, and are evocative of action. This dynamism, however, is not kinetic, is not one of physical action, even though physical dynamism is ordinarily associated with physical action. This effect of non-kinesis is generated by the fact that the figure is not only still, he is seated. His body has assumed a position normally associated with rest but the idea of rest is negated by the rippling bulge of his muscles. The only logical conclusion, reinforced by the work's title, is that the dynamism projected through the figure's body is mental dynamism demonstrated in terms of deep and possibly anguished thought the figure is immersed in. The rugged character of the stone composing the figure's body and the plinth on which it sits as well as the pronounced undulations of the bones of the feet and fingers amplify the sense of potent physicality projecting powerfully contained energy. The evocative force of the work is expanded by its original positioning overlooking Rodin's Gates of Hell, his sculptural depiction of scenes from the

-

4

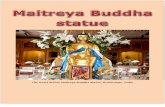

Italian writer Dante Alighieri's famous picture of Hell in Inferno, the first book of his Divine Comedy, hell being in Christian understanding the place of everlasting torture unredeemable humans go when they die, an idea Dante explores in terms of commentary on the nature of human life, the relationship between the work of the poet and that of the sculptor being beautifully described at the Rodin Museum site on The Thinker in relation to the Gates of Hell . Rodin's The Thinker, therefore, is engaged in reflection on the challenges, tensions and negativities of human existence as dramatized by the sculptor's recreation of Dante's cosmological image in Inferno. The Bodhisattva Maitreya The other most famous approach to depicting reflection through the body is represented by sculptures of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Buddhist art. Perhaps no more sublime evocation of the depth of peace, demonstrating a cognitive penetration to the meaning of being, beyond the vicissitudes of existence in pain and fulfilment, an ultimate Buddhist ideal, has ever been created. The beatific peace of the face of the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism understood to have reached this cognitive state, or that of Bodhisattvas, beings who are committed to helping others reach this state even as they either strive to reach it or have reached it, is complemented in these sculptures by the physical postures they assume, suggesting a concentration of energy within the integration of body and mind, the figure placing one leg on his knee in calm poise or seated in the yogic lotus posture, both legs curled in a delicate but firm pose under the body, creating a pyramid with the legs as the base, the middle of the body as the sides and the head as the apex, an image of physical concentration and mental focus. The lyricism of the slender form of the Bodhisattva Maitreya above resonates with the stamp of profound contemplation on the face through the correlative visual harmony of the body and the balance of facial features suggesting what the English poet John Keats in his "Ode On a Grecian Urn" describes as unheard melodies, an internal music vibrating, in this context, in terms of the perfect alignment of all aspects of the self. The balance of the body in its simplicity of form and yet majesty of manner suggests the Buddhist ideal of transcendence of life's vicissitudes occasioned by the subjugation of humanity by ignorance of the forces that define the nature of existence, the statue embodying the majesty of kingship, not over any other person or domain but over one's self and the course of one's existence.

-

5

Bodhisattva Maitreya Asuka period, 7th century Tokyo National Museum http://webarchives.tnm.jp/imgsearch/show/E0010229

-

6

Owosu-Ankomah's Thinking the Microcron, No. 1. Another approach to the challenge of correlating reflection and the human body in visual art is that of the use of physical posture in relation to the character of the physical environment, as demonstrated by the paintings of the Ghanaian/German artist Owosu-Ankomah. Ankomah, in a couple of his works, adapts the seated pose made famous by Rodin, in others, the figure is seated in a different pose or is standing. In those images which are most clearly expressive of reflection, the figure is shown interacting with abstract forms in a contemplative manner, suggesting reflection on those structures as other abstract patterns shape the space of interaction, within an environment suffused by a calm blue amplifying the sense of immersion in a reflective experience. The blending of the human form with the symbol space, as these symbols are imprinted on the human body in gradations of the colour that suffuses that space, demonstrates interactivity between the human being and spatial construction in terms of abstract symbols and colour harmony. A unique kind of space is thereby projected, one demonstrating properties that inspire profound reflection and the sense of the ineffable, a density of evocative value suggesting the convergence of the cosmos at a particular point in space, this being my interpretation, from personal experience in Nigeria, of Owusu-Ankomah's description of the inspiration for his spatial depiction in the Akan version of an understanding of nature pervasive across cosmologies that emphasize the cognitive agency of nature, better known as animism. This is the idea of "kusumadze" or "kusum", a " sacred site involved in the performance of mystery rites... sacred, secret, mysterious places where we meet for ritual exchanges with whatever protective spirits guide our culture" as Owusu-Ankomah describes this in Owusu-Ankomah: Microcron - Kusum (Hidden Signs - Secret Meanings). This harmony of the figural, the abstract and the spatial thus suggests the contemplative depth, and in consonance with the scope of abstract symbols shaping the space, the range of cultural and multi-disciplinary engagement required to grasp the constellation of ultimate possibility represented by the band of multi-coloured circles the figure gazes on, the manifestation of cosmic potential the artist names the Microcron.

-

7

Owusu-Ankomah Thinking the Microcron No. 1 2011, Acrylic on Canvas 120 x 140 cm 25 / 44 http://www.owusu-ankomah.de/en/artworks.html

-

8

Owusu-Ankomah, Auguste Rodin and Michelangelo Buonarroti Owusu-Ankomah is a heir, in terms of inspiration, of Auguste Rodin, and Rodin and Owusu-Ankomah are inspirational heirs of the greatest master of the depiction of the human form in Western art, the 15th-16th century Italian polymath, Michelangelo Buonarroti. Integrating various elements visible in the Renaissance master's body of work, they have created their own unique visualisations. Their achievement may be seen in relation to Michelangelo's Moses, a marble figure that seems to contain a latent volcano through the palpitations of energy suggested by the modelling of its form, even as the near mythic Biblical figure is shown seated, and his Captives, emerging with agonising lyricism from the stone, unfinished at their creator's death. The depiction of power, at times at rest, and poetic motion, both at times related to reflection, is what the master's disciples have created as their contribution to the artistic dramatisation of the scope of possibilities of the human form. Victor Ekpuk's The Thinker Another example, demonstrated by Nigerian-US artist Victor Ekpuk, in his drawing adapting the title of Rodin's famous sculpture The Thinker, is that of evoking rather than depicting the human form, dispensing altogether with its concrete contours, and suggesting it's spatial actualisation through a basic sequence of lines, the reflective activity evoked through inscriptions suggesting semiotic space as well as the act of interpretation and reflection that semiotic space involves. Ekpuk achieves in this work one of his more exquisite explorations of relationship between various kinds of visual forms as may be depicted two dimensionally, in this case using the line or brushstroke and ideographic patterns suggestive of lettering, in relation to the semi-circle, the circle or oval. The human body is represented by nothing more than a curved line, the lower curve perhaps suggesting the bend at the waist we see in Rodin's seated figure and its adaptations, and the head by two semi-circles, one inside the other, evocative of the brain inside the head, the red colour filling the semi-circle and resonating with blood as nourishing fluid for the brain, the arrangement of white dots on the red background possibly projecting the patterns that shape the mind.

-

9

Victor Ekpuk The Thinker 2012, 12"x9.5" Graphite, ink & collage on paper http://www.aquaartmiami.com/PopUpObjectDetails.aspx?dealerid=27511&objectid=579924

-

10

The semi- circular forms are positioned within a square lattice of enigmatic inscriptions demonstrating the structured progression and visual form of script but ultimately uncorrelative with any known script, therefore dramatising human symbol making as a primary means of relating with reality as well as the challenges of creating and interpreting these symbol complexes. The entire form is dynamic in the way it shapes space through the flourish of the single line moving outward to complete the open ended formation of the central semi-circle and the fluid brushstroke that defines the lower part of the form. Rodin's sculpture or the idea it projects is here re-imagined, but in a manner that distills an imaginative essence from the combination of physicality and evocation of mental action through the concrete form of the body that makes Rodin's work great. Perhaps the fluid balance of the brushstrokes that define Ekpuk's thinker could transport one to the dynamism of the daily walk of life enabled by the energising power of nature and the understanding this journey may bring as the human being moves in time but may aspire to eternity, this being a transposition of a meaning of the spiral, a central, recurrent motif in Ekpuk's art, as understood in the Nsibidi semiotic forms from which the artist derives his signature engagement with the hermeneutic imperatives of script.