The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s last BARRIER REEF

Transcript of The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s last BARRIER REEF

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s last great wilderness areas. Stretching more than 2000 km along the coast of north-eastern Australia, the Reef is also the largest coral ecosystem on Earth. Its unique environment supports an astonishing and almost unequalled biodiversity, from microscopic plankton to whales, with many more species still to be discovered.

The human history of the Reef is no less intriguing. Indigenous Australians have known the Reef for millennia and their Dreaming stories offer tantalising glimpses of a truly ancient world. Europeans first encountered the Reef some 500 years ago on perilous voyages into unknown waters, but have only recently begun to understand its almost unimaginable complexity.

This book weaves these equally vibrant strands of natural and cultural heritage into a single narrative that leads the reader on their own voyage of discovery through one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

THE GREAT BARRIER REEF

A QUEENSLAND MUSEUM DISCOVERY GUIDE

THE G

REAT B

AR

RIER

REEF

A Q

UEEN

SLAN

D M

USEU

M D

ISCOVER

Y GU

IDE

Published by the Queensland Museum with the generous support of BHP Billiton Cannington

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

FOundatiOns OF tHE REEFThe Great Barrier Reef is the largest reef system on Earth. However, perhaps surprisingly, it is also one of the youngest reefs with its history of construction taking place within the past million years. During this time, there have been several periods of reef growth, but the modern Reef as we know it is only about 8000-years-old.

Nonetheless, the Great Barrier Reef has a complex history linked to sea level and climatic change and the structural evolution of the Coral Sea Basin.The Great Barrier Reef formed in the warm, shallow seas of what is now the north-eastern part of Australia’s vast continental shelf. Its beginnings are related to the plate tectonics of the Earth’s early geological history and the break-up of the ancient super-continent of Gondwanaland

Waier Island, Torres Strait. Located at the far northern end of the Great Barrier Reef, this small volcanic island erupted through the oldest foundations of the Great Barrier Reef during the Pleistocene Epoch. The volcanic rocks of the island contain fragments of limestone from these ancient reefs. The limestone shattered when the volcano erupted through the reefs. The likelihood of a volcano coming up through a reef is not high and this event indicates the very specific geological evolution of the Great Barrier Reef.

10 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

The Great Barrier Reef begins in the Gulf of Papua to Australia’s north, where its ancient foundations are overlaid by sediments from the Fly River in New Guinea. International oil drilling projects in the Gulf have revealed buried barrier reefs dating back 6–7 million years at about 100 m depth. However, long-term growth of these reefs was not possible because of continuing geological change, including temperature and sea level fluctuations, heavy sediment loads from the Fly River and the rising Eastern Highlands, as well as some volcanic activity. Even on the continental shelf, volcanic activity erupted through some early established reefs.

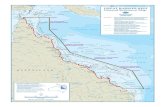

A satellite view of the Great Barrier Reef. The Reef stretches 2300 km from the tip of Cape York, along the Queensland coast, to just off the southern city of Bundaberg, although its oldest foundations lie in Gulf of Papua to Australia’s north.

GEOLOGY & GEOMORPHOLOGY 11

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

A coral-covered reef front, or reef slope, faces the open ocean. The reef front rises from the mesophotic zone (see p. 31) into coral covered buttresses and it consists of two distinctive ‘sub-zones’: the upper reef front and the outer reef. The upper reef front lies in well-lit waters of between 0–20 m depth and supports the greatest diversity of hard corals and fish of any part of a coral reef system. It tends to be dominated by resilient, massive or encrusting corals that face into the prevailing wind and wave direction and act as breakwaters. The corals often take a ‘spur and groove’ formation and some scientists believe that these buttresses act as passageways for sediments leaving the reef flat.Alternatively, they may have originated as karst landforms created by limestone erosion when the sea level was low (see p. 20).

The outer reef below 20–30 m depth is typically steep and cliff-like, with overhangs, caves, rubble-covered terraces and sand or rubble-floored channels.

Background: Osprey Reef, North Horn, Western Wall.

Above left: Upper reef front. Lady Elliot Island.

Below left: Aerial view of reef crest. Bramble Reef.

40 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

The highest and shallowest part of the reef is the reef crest comprised of an intertidal algal pavement and a coral shingle zone.

The crest is the narrowest of the main reef zones, ranging from a few metres to more than 100 metres in width. It separates the reef’s protected inner reef and lagoon from the ocean beyond and often looks like a dark, irregular band of seawater, or a line of white breakers when it is windy or stormy. The composition and structure of the reef crest is influenced by the prevailing wind direction, wave action, type of reef and geographic location. It incorporates channels, side pools, sand patches, crevices, structures that resemble miniature atolls and rubble fields. In contrast, on the protected sides of islands where there is little wave action.the crest is usually poorly developed, or may even be absent.

Above: Lady Elliot Island

Left: Osprey Reef, Admiralty Anchor, western side.

GEOLOGY & GEOMORPHOLOGY 41

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

HiGH isLandsThe high, rocky (continental) islands close to the coast are parts of the mainland that have remained exposed since the last rise in sea levels. Not surprisingly, these islands support plants and animals also found on the adjacent mainland.

Early naturalists often invoked divine intervention to explain the presence of terrestrial plants and animals on remote islands. However, such colonisation results from a mix of remarkable adaptations and chance. For example, some (insects, birds and bats) fly to these destinations, others are blown on air currents (insects and spiderlings), hitch a ride on floating debris (reptiles and mammals), or disperse by hardy eggs or seeds.

Rocks and forests of Fitzroy Island.

DISCOVERY GUIDE TO THE GREAT BARRIER REEF62

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

TRAVELLING PLANTSPlants grow on even the most isolated islands and cays. Octopus Bush (Heliotropium foetherianum), above, which is common on the Great Barrier Reef islands, has reached the world’s most remote atoll, Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands group south-east of Tahiti. Floating, salt-tolerant seeds that can remain viable for many months can be carried vast distances by ocean currents. Seeds or fruit that attach to birds and other animals on contact can also be deposited far from their point of origin. For example, Chaff Flower fruit (Achyranthes aspera) attach with a long, recurved spine and Tarvine (Boerhavia albiflora) fruit is covered in small, sticky projections.

Below: Orb-weaving spider (Poltys sp.).

CAY COMMUNITIESThe first plants to colonise sand cays are the salt and drought-resistant species found on any beachfront and foredune, such as the the grass Thuarea involuta, Beach Morning Glory (Ipomoea pes-caprae) and Beach Pea (Canavalia rosea). On more stable and exposed cays, rings of shrubs form. These are likely to contain Octopus Bush, Silver Bush (Sophora tomentosa), Fan-Flower (Scaevola taccada) and Beach Sheoak (Casuarina equisetifolia). Herb flats and succulent mats are also common on sand cays. Typical plants include grasses, (such as Lepturus repens and Stenotaphrum micranthum), Tarvine, Caltrop (Tribulus cistodes), Lantern Flower (Abutilon albescens), the daisy (Wallastoni abiflora) and the succulents Sea Purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum) and Pigweed (Portulaca oleracea). With time, increasing complexity and increased nutrients, coral cays will develop forests of Pisonia, Beach Sheoak and Sea Trumpet (Cordia subcordata), or a community known as ‘coastal parkland’, with Octopus Bush, fan-flowers, Pisonias, screw palms (Pandanus spp.), above, figs such as Ficus opposite and Beach Sheoak. Where sediments collect along the shoreline, or in lagoons, stands of mangroves may be present.

Left: Jumping spider (Cosmophasis sp.); Right: Bolboceratid beetle.

REEF HABITATS 63

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

COLumNAR cylindrical, column or trunk-like

mASSive rounded, domed or bulky masses of coral

bRANChiNg branched or antler-like

FOLiACeOuS leaf-like or lettuce-like

CORAL gROWth FORmSThe bewildering variety of shape and texture is made more confusing by the fact that it is common for colonies of the same species to grow into different shapes. Physical factors, such as the level of water turbulence and exposure, the impact of competitors or predators and storms and tidal surges, can all influence how a coral colony develops.

The shape of hard corals varies enormously. Some colonies resemble plates, others look like shrubs and they may also be tongue, brain or vase-shaped. To help make sense of this profusion of shapes, marine biologists have recognized the following growth forms:

THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE74

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

LAmiNAR plates or tables arranged in a tier

eNCRuStiNg surface layer growths

FRee-LiviNg unattached to reefs

vASe-ShAPed

Mushroom corals (Family Fungiidae) are so-named because they resemble the gilled underside of a mushroom (without its stem). Some mushroom corals house a single, large polyp that is not cemented to the reef but is instead free-living and mobile. The mouth of these polyps is located within a central depression from which the fine ribs or struts (septa) radiate. When the polyp is extended, its tentacles cover the upper surface. Mushroom corals are likely to be found in calm pools, lagoons and deep water.

CORALS 75

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

A bright yellow calcareous sponge, Pericharax sp., which has its spicule skeleton composed of calcium carbonate (rather than silicon dioxide common in most species of sponges).

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

bizarre and beautiful‘Marine worms’ is the collective name given to a group of soft-bodied, legless, invertebrate animals that are longer than they are wide. About 20 phyla of ‘worms’ have been recorded from the Great Barrier Reef, where the coral habitats support an amazingly diverse variety of segmented worms, flatworms, ribbon worms, peanut worms and spoon worms.

The segmented worms (Phylum Annelida) comprise the largest group and they include the polychaete worms. Some polychaetes have sedentary habits, living in temporary, or permanent, tubes from which they project to capture food.

Free-living or swimming species, such as the Scale Worms (Polynoids), and Blood Worms (Eunicids) are more active and have adaptations that enable to hunt prey and avoid predators. These include a large number of equal body segments, well developed parapodia, jaws, which can be extended outside the body, and sense organs on the ‘head’.

In contrast, sessile species move very little inside their tubes so they have fewer body sections, and reduced or modified parapodia. Instead of jaws, they often have food-collecting organs such as tentacles. Sessile species include Christmas Tree Worms (Serpulids), Feather-duster Worms (Sabellids) and Spaghetti Worms (Terebellids).

As their name suggests, the body of segmented worms is divided into a number of segments, each with a pair of fleshy appendages called parapodia, which in turn are divided into two lobes containing bundles of bristles. In some families of segmented worms, the parapodia are reduced or modified.

Spaghetti WorMSSpaghetti Worms are a conspicuous group of diverse species, most of which live in tubes, although some live naked in sediment. They have numerous long tentacles that spread over the surface like fine strands of translucent spaghetti.

Previous pages: The head of the terebellid polychaete Loimia ingens showing long feeding tentacles. Cilia create currents drawing particulate matter into the groove running centrally along each tentacle. The particles get tangled in mucus and moved to the mouth where glandular lips sort the particles by size. Fine food particles are ingested, and medium-sized particles go to form the tube in which the worm lives. Large particles are rejected.

Left: The terebellid polychaete Reteterebella queenslandica from Lizard Island extracted from its tube in the coral, showing its contracted tentacles and brown bushy gills. Inset: Reteterebella queenslandica with extended tentacles.

156 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

feather-duSter WorMSFeather-duster Worms are readily recognized by their spectacular crown of delicate, feather-like tentacles after which they are named. They construct a muddy tube formed from mucus and grains of sediment and they live in sediments at the base of coral boulders, although some species can bore into coral limestone. These worms are suspension-feeders and sieve food from water currents using fine filaments on the tentacles. Food and other particles are then passed along the tentacles to the mouth, where they may be eaten, used to construct the tube, or rejected.

A Feather-duster worm Sabellastarte sp., removed from its tube.

Above: A Feather duster worm, (Sabellastarte sp.) removed from its tube and showing the tentacular crown and reduced number of parapodia.

Right: A Feather duster worm, (Sabellastarte sp.) emerging from its tube.

MARINE WORMS 157

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

REEF TREASURESMolluscs are among the most beautiful and numerous animals on the Great Barrier Reef, displaying an astonishing variety of sizes, shapes and colours. These soft-bodied invertebrates usually have a calcified, external shell that protects them from predators. The group includes: the gastropods (snails and slugs); bivalves (clams, pearl oysters, mussels); chitons; cephalopods (octopus, squid, cuttlefish and Nautilus); and a few minor groups.

On the Great Barrier Reef, gastropods and bivalves are the most dominant type of mollusc and there are probably more than 10,000 species. Among the more familiar gastropods are the venomous cone snails, which hunt worms, fish or other molluscs; the spider strombs with their multi-

pronged shell; and the beautiful cowries and nudibranchs. Of the bivalves, the giant clams are the most spectacular species on the Reef, but numerous types of venus clams, oysters, scallops and coral-burrowing mussels are also to be found.

After the death of the animal, molluscan shells contribute greatly to the physical structure of the Reef and its associated sediments and, of course, the intact shells of marine snails are eagerly sought by hermit crabs!

Previous pages: A tiny, planktonic, octopus hatchling (Octopus sp.), Heron Island.

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

‘CAT’S EyES’ And TURbAn SnAilSA ‘cat’s eye’ is a thick, calcareous operculum attached to the foot of turban snails. It acts as a barrier against predators if the snail is forced to retreat into its shell.

In the Tapestry Turban (Turbo petholatus, right), the strong resemblance of its ‘cat’s eye’ to an eye of a fish or octopus may also intimidate predators. They were often used in jewellery and Melanesian ritual masks, possibly with the intention of ‘warding off the evil eye’. In most other snails the operculum (if present) is relatively thin and flexible.

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

SEA SlUGS‘Sea Slugs’ is a general term applied to highly evolved marine snails which have either lost or substantially reduced their shell and includes groups such as nudibranchs, sea hares, sap-suckers and side-gilled slugs. Many species have developed the defence strategy of incorporating toxins from their food in order to render themselves poisonous to predators.

Although sea slugs are hermaphrodites (having both male and female sex organs) they must still mate in order to produce fertilised eggs. Typically they lay ribbon-shaped egg masses, sometimes arranged in a coil. They have specialised diets of sponges, hydroid corals, algae or even other nudibranchs! As many as 600 species of sea slug are believed to occur on the Reef, most of them nudibranchs.

This sea slug (Chelidonura inornata) lacks teeth (the radular teeth) and instead ingests tiny flatworms whole. It is easily distinguished from nudibranchs by its two tapering tails.

inoRnATE TAilEd SlUG

This species (Roboastra luteolineata) feeds on other nudibranchs often as big as itself or larger. It does this by engulfing the prey by great expansion of its oral feeding tube.

yEllow-linEd nUdibRAnCH

nUdibRAnCH MiMiCRyThe Pustulose Phyllidiid (Phyllidiella pustulosa, left) is a common nudibranch on the Great Barrier Reef and its pink and black warning colours signal that it is distasteful to fish. A different marine animal, the Imitating Flatworm, (Pseudoceros imitatus, right) also occurs on the Reef and looks very similar to the nudibranch.

Researchers believe the rare flatworm mimics the colour pattern of the nudibranch as a defensive mechanism to also avoid predation by fish. Many brightly coloured nudibranchs prey on sponges and it is likely they obtain their distasteful compounds from the sponges on which they feed.

176 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

Nudibranchs are truly the ‘flowers’of the molluscan world. However — a warning — the bright colours of many species can indicate high toxicity.

Clockwise from top left : Purple-ringed Aeolid (Flabellina exoptanda); Fine-lined Arminid (Dermatobranchus dendronephthyphagus); Cup-coral Aeolid (Phestilla melanobranchia); Black’s Nudibranch (Tambja blacki); Co’s Nudibranch (Chromodoris coi); at centre — Kune’s Nudibranch (Chromodoris kunei ).

Following pages: Avern’s Nudibranch (Glossodoris averni).

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

SEEKing ShEltErOn the Great Barrier Reef many urchins shelter during the day and are only active at night. Some species excavate holes in the coral where they live permanently. Others cause bioerosion while browsing algae from hard substrates of the Reef. Bioerosion is of particular concern on Atlantic Ocean reefs where populations of sea urchins are sometimes at high density.

Sea urchins have an important role in the calcium carbonate budget of the Reef environment (see p. 32). Calcium carbonate from the coral passes through the digestive system of echinoids and is ejected as a fine powder, which contributes to the lagoonal sediments within reefs.

Using the five teeth in its jaw, this rock-boring sea urchin, Echinometra mathaei, sits in a hole it has excavated in the coral.

The skeletons (‘tests’) of regular sea urchins are rounded with the body surface divided into ten radial sections. The beautiful micro-architecture is clearly seen in this collection from the Queensland Museum (shown at actual size).

220 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

Opposite: Bony fish inhabiting coral reefs have many brilliant colour patterns, but these are generally on the membrane of skin covering the scales. The underlying scales are generally translucent, or opaque.

Most modern bony fishes have thin, bony, overlapping elasmoid scales. These often have annular growth rings, are generally more flexible, and lack the enamel coating and horizontal ridges usually present in the placoid scales of sharks and rays.

Bioluminesence in FisHOn dark moonless nights, the blinking lights of flashlightfishes can sometimes be seen around the surface of the Reef. Flashlightfishes have a large white light organ under each eye, which is colonised by luminescent bacteria. The light emitted assists these noctural fish to see, locate and communicate with other members of the school; to attract small crustaceans and other zooplankton on which they feed; and to confuse predators. Onefin Flashlightfish (Photoblepharon palpebratus), shown above, are able to regulate the amount of light visible by raising an eyelid-like curtain of black skin. They blink at various rates according to prevailing conditions and for different purposes. For example, they produce sudden flashes of light to startle and confuse predators, giving the fish time to escape. This species is found in shallow water to depths of 350 m. By day, it shelters in dark caves and crevices in deep water, but actively forages in the open at night.

Australian Pineapplefish (Cleidopus gloriamaris), also known as Port-and-starboard‑light fish, have reddish luminescent organs on the sides of the lower jaw.

274 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

During the summer months, thousands of nesting turtles make their way to the islands of the Great Barrier Reef which are important rookeries for Green, Loggerhead, Flatback and Hawksbill turtles.

Green Turtles nest on islands in both the southern and northern GBR. Raine Island, Moulter Cay, Sandbanks No. 7 and 8 and Bramble Cay are of particular importance as they support the world’s largest breeding aggregation of this species.

Loggerheads nest on islands in the Capricorn – Bunker group of the southern GBR and on the adjacent mainland coast. Mon Repos, near Bundaberg, is an important rookery for this species with nesting occurring between November and February and hatchlings emerging from January to late March. Islands off the central Queensland coast are important Flatback rookeries and Hawksbill Turtles nest on islands in the northern GBR.

High density nesting of Green Turtles on Moulter Cay. These turtles are part of the world’s largest breeding aggregation of this species.

Many of these hatchlings will fall victim to predatory birds, crabs and fish during the first few hours of life. Only 1 in 1000 will make it through to maturity.

THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE286

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

anCIenT maRIneRSMarine turtles are long-lived, taking 35–50 years to reach sexual maturity. Their life histories are complicated and they show high levels of fidelity to feeding and breeding grounds. At the onset of the breeding season, adult turtles migrate from their feeding grounds to a courtship area adjacent to their nesting beaches. These breeding migrations can cover many hundreds of kilometres and distances of up to 3000 km have been recorded. After mating, the males return to their feeding grounds and the females remain at the nesting beaches to lay their eggs. These are deposited in a nesting chamber above the high water mark and several clutches are laid each season, at about two weekly intervals.

When a female turtle has deposited her final clutch for the season, she also returns to her feeding grounds. The eggs incubate for approximately two months before

hatching. The sex of the hatchling turtles is determined by the sand temperature in the nest. Cooler sand temperatures mainly produce male hatchlings whilst warmer temperatures produce females.

On hatching, the young turtles erupt from the nest en masse (usually at night) and scamper down the beach to disappear into the surf. It is thought that only one in a thousand will live to reach sexual maturity. The young turtles (all species except Flatbacks) now disappear from the shallow coastal waters and ride the ocean currents for the next five to ten years.

When they reappear in coastal waters, they have a carapace length of around 40 cm. The young turtles may shift between areas for several years before finally settling on a feeding ground where they remain until they reach maturity. At this point, the cycle begins again.

REPTILES 287

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

BReAcHBreaching is arguably the most spectacular behavior. The whale uses its tail to launch out of the water and then land on its back with a large splash. There are thought to be several reasons why whales breach, including dislodging parasites from their skin and just for fun.

BLOWA surfacing whale produces a spray plume as it exhales water and air from its blowhole. Humpbacks breathe every 7–10 minutes, although they can remain submerged for up to 45 minutes.

HeAD LunGeIn this display the whale lunges forward with its head raised obliquely above the water.

Pec SLAPOne or both fins are raised and then slapped on the surface.

TAIL SLAPWhales raise their tail flukes and then slap them forcefully on the surface. This behaviour is often repeated. Also known as lobtailing.

PeDuncLe SLAPThe tail and lower part of the body closest to the tail (peduncle) is thrown out of the water and then slapped on the surface.

‘SPy HOP’‘Spy-hopping’ is the term used to describe a whale raising and holding its head vertically out of the water. It is thought that whales ‘spy-hop’ when they are examining surface activity.

HUMPBACK BEHAVIOURSHumpback Whales are ‘expressive’ animals that engage in a variety of consistent behaviours to communicate with each other, to signal danger, as part of their courtship patterns and to interact with other animals and the world around them.

Individual Humpback Whales have distinctive patterns underneath the tail, which are best seen when the tail is raised and arched above the surface as the whale rolls into a dive. This behaviour is known as a fluke up dive. Scientists use the under tail patterns to identify (‘fingerprint’) individuals for surveys and behavioural studies.

‘FINGERPRINTING’ INDIVIDUAL WHALES

298 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

DEEP WATER NEIGHBOURSBlue Whales are the biggest animals ever to appear in the earth’s evolutionary history. They have been reported to grow to a length of 30 m and a weight of 190 tonnes, but most Antarctic Blues (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia) reach around 24 m and 90 tonnes, while Pygmy Blues (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) grow to around 21 m and 60 tonnes. (A third species, Balaenoptera musculus musculus, is restricted to the northern Hemisphere). Although they occur around the Australian coastline and make solitary winter migrations into lower latitudes, Blue Whales probably do not eat within, or near, the Great Barrier Reef.

Blue Whales are endangered. In 1905, the population was estimated at 239,000, but by 1973, this had been reduced to just 360 individuals. Today, Antarctic Blue Whales may number around 2000.

Other large whales that could be confused with the Blue Whale, and which are occasionally recorded on the Reef, are the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Bryde’s Whale (Balaenoptera edeni).

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SEAThe passage of a whale between the surface and the depths leaves a marker on the ocean surface. This comes in the form of an elongated area of still water that differs markedly from the surround surface. Researchers and tourism operators can use these patches of water to detect the presence of whales.

MAMMALS 299

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

CaPRICORN SIlvEREyE: THE REEF’S ONly ENDEmIC BIRD‘White-eyes’ (Zosterops species) are common small birds that occur across Australia. They are named for the fine ring of silvery-white feathers around their eyes. Three species occur in Australia: the Silvereye (Zosterops lateralis) in coastal Australia and Tasmania, and the Pale White-eye (Zosterops citrinellus) and Yellow White-eye (Zosterops luteus) of northern Australia. Given the wide range, variability and separation between Silvereye populations in Australia as well as New Zealand and Pacific islands, it is

hardly surprising that 16 distinct subspecies can be recognized. Three of these occur in Queensland, but only one is found on the vegetated cays of the Capricorn and Bunker Group of the southern end of the Great Barrier Reef. The Capricorn Silvereye (Zosterops lateralis chlorocephalus) was first discovered in October 1910. It is the largest of all the Australian subspecies and also has a more yellow-green head and whiter breast than its mainland relatives. It has been extensively studied on Heron Island.

312 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

TROPICBIRDSThere can be few more splendid sights on the Great Barrier Reef than an immaculate white, almost shining, Red-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon rubricauda) set against a deep azure sky or sparkling blue ocean.

The Red-tailed Tropicbird‘s glossy white plumage is highlighted in black and scarlet, with a black eyebrow and feet, bright scarlet beak and tail plumes. The largest breeding colonies of the Tropicbird are found at the Herald Cays and Coringa Islets in the Coral Sea, but some birds also breed at Raine and Lady Elliot Islands.

Tropicbirds are robust high-fliers that will dive into the sea to catch fish and squid. During the breeding season, they will hover and make sweeping arcs at low altitude in the vicinity of nest sites, which are usually a simple scrape on the ground under a shady bush. A second species, the White-tailed Tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus), occurs, but does not breed, on the Great Barrier Reef.

BIRD ICONS OF THE gREaT BaRRIER REEF

BIRDS 313

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

There is also evidence from the eastern Torres Strait, that people were collecting shellfish about2800 years ago on Mer (Murray) Island. Fine red-slipped pottery has been excavated from the nearby island of Dauar and dates to 25000 years ago. Analysis of the pottery indicates it was obtained from Papua New Guinea. Other pottery fragments of a similar age have been excavated from the Islet of Pulu, near Mabuyag, suggesting local manufacture and that coastal Papuan peoples migrated to the Torres Strait around 2500–3000 years ago. Further evidence of human occupation of the Torres Strait come from huge midden deposits of shells, animal bones, [turtle fish, dugong] and cooking stones. As well, stone arrangements and rock, paintings in the Torres Strait are stylistically quite different from those in New Guinea and mainland Australia.

Torres Strait Islanders hunted, fished and gathered food from the sea. A lack of terrestrial animals on the islands was offset by the availability of protein-rich marine foods. Turtles and dugong were hunted with harpoons from canoes. Inshore, people also fished on reefs and gathered shellfish. More than

450 species of marine animals were eaten. On some islands wild plant foods were collected. On others raised garden beds were used to grow bananas, yams, and sweet potatoes.

The Islanders travelled in double outrigger canoes, the hulls of which were obtained via trade with New Guinea. These are the largest indigenous watercraft in Australia. Torres Strait Islanders were linked by complex trade networks and intermarriage — which also involved the adjacent Australian and New Guinea mainlands.

In 1606, Luis Vaez de Torres, commander of the Spanish ship, San Pedro, became the first European to sail through the perilous waters of the region. Thereafter, Torres Strait Islander communities increasingly came into contact with European mariners seeking water and food supplies, sometimes with consequences for both sides. Relationships became more amicable from the 19th Century, allowing the development of trade. Islanders exchanged food, water and turtle shell for metal objects, including steel and iron, bottles and red cloth and beads in a trade relationship similar to that of the GBR islands.

Above: Basket, with woven cross. Pandanus, Mabuyag, western Torres Strait. Left: Arrows, Mer.

Fish hooks, turtle shell, Badu, western Torres Strait.

Gabagaba (club, stone head), Erub and Loyalty Islands-style club, Erub.

336 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

From the 1840s, The London Missionary Society (LMS) had been working to spread Christianity throughout the south-west Pacific. The Society had hoped to convert the peoples of New Guinea to Christianity, but instead decided to set up a base on Erub Island in 1871. The arrival of the Society brought the ‘light’ of Christ to the ‘heathen’ darkness of the Torres Strait and is commemorated in the ‘Bringing of the Light’ Festival.

In the 1860s commercial bêche-de-mer (trepang) operators moved into the region (see p. 364) and, by 1870, the pearling industry had begun in earnest (see p. 367). Torres Strait Islanders, with their superior seafaring skills and knowledge of seas and seasons were essential to the pearling industry. Islanders played a major role in the development of the pearling industry in the Torres Straits. However, they were also exploited and pearling dealt a significant blow to traditional ways of life. The advent of plastic buttons spelt the end of the industry.

The Torres Strait island of Mer was the centre point for the landmark case Mabo vs Queensland in the High Court of Australia. The case overturned the legal fiction of terra nullius, which had claimed Mer as ‘a land belonging to no one’ at the time of colonial annexation. This decision was to have a profound effect. Eventually, all Torres Strait Island communities had their native title rights recognised by the Australian legal system, with later cases recognising rights over sea. The case also had major implications for Australian Aboriginal people seeking rights over their traditional country.

Trochus shell and button blank, Erub.

Recent and archaeological examples of Dibi dibi (mans chest ornament)

HISTORY 337

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

unDeRSTAnDIng THe ReefEver since Captain Cook made his first observations of the Great Barrier Reef in the late 18th century, naturalists and scientists have been determined to learn more about its environment and biodiversity, especially the intricate and complex interactions and relationships that occur there.

The earliest research on Great Barrier Reef was conducted by naturalists embarked on survey ships in the tradition of Joseph Banks on the Endeavour, or Charles Darwin on the Beagle. During the 19th century and early 20th centuries, a new generation of scientists and naturalists chartered vessels to carry out expeditions to often inaccessible, parts of the Reef. The results of these expeditions were published

in popular accounts, or in scientific journals. The first comprehensive monograph on the Reef was a splendid tome entitled, The Great Barrier Reef of Australia: its Products and Potentialities by English scientist, William Saville-Kent. It was published in 1893 and is also one of the earliest publications to make use of photographic plates. As the subtitle suggests, the work is not just a description of the Reef, it also identifies the resources most worthy of exploitation.

Above: William Saville-Kent in the field with camera and specimens. Left: Cover of Saville-Kent’s monograph and colour plate of reef fishes (opposite).

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

fROM SOuVenIRS TO kITScHReef visitors have always collected mementos of their Great Barrier Reef experiences. Souvenir items have ranged from artwork, such as the carved Nautilus shell (upper right), to painted sea shells (upper left) and ceramics (middle left). Hand-painted corals (lower right) and collections of painted corals and shells (such as these incorporated into a lamp, lower left).

384 THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

OlIVe ASHwORTHOlive Ashworth (1915–2000) was a Brisbane born artist, textile designer and photographer active between 1933–c.1988. She is best known for her original and striking textile designs of the Great Barrier Reef and north Queensland rainforests. The Reef designs were based on sketches and photographs, taken while holidaying on the Reef in the late 1930’s (right). The designs were widely used, e.g. for tourist brochures, murals and textiles, in the early 1950’s.

Ashworth’s designs proved most popular when made up as a dress fabric and have been included in several Queensland Art exhibitions. The Queensland Museum’s Olive Ashworth Textile Collection consists of artwork, fabric and clothing samples, fabric yardage, fashion photographs, price lists and press clippings mainly from the latter part of her career.

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

RUBBISHIt has been estimated that an astonishing seven billion tonnes of litter and rubbish from the land or ships at sea enter the world’s oceans every year. Ocean currents carry some of this litter thousands of kilometers from elsewhere in Australia, the South Pacific, South-east Asia and from ships to the Great Barrier Reef. This litter includes, among other things, cans, bottle caps, footwear, toothbrushes, plastic bags, fibreglass, fishing nets, timber, polystyrene items and nylon rope. and even parts of buildings.

Reef litter sometimes contains deadly surprises in the form of discarded weapons of war and bottles or containers of toxic chemicals, such as pesticides. This, and the accidental or deliberate dumping of toxic wastes and contaminated run-off can lead to heightened mortality of marine animals, tainted seafood, and can seriously impact fisheries.

INTROdUCEd SPECIESIntroduced and invasive species are one of the many issues facing reef managers. Some of these, like the House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) and Goat (Capra hircus) are non-native species. Others are native species that have been accidentally introduced from the adjacent mainland.

FaTal PlaSTICSFloating litter is hazardous to many marine animals. The stomach of a rare Bryde’s Whale (Balaenoptera edeni) that washed ashore near Cairns in 2000 contained a mass of plastic sheets, bait bags, zip-lock bags, fertiliser bags, frayed rope, shopping bags and several metres worth of plastic strips. Some of this material may have been accidentally ingested, mistaken for food. Marine animals, especially marine turtles and Sunfish (Mola sp.), often confuse floating plastic bags for sea jellies with fatal results.

THE GREAT BARRIER REEF | DISCOVERY GUIDE404

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

COaSTal vEGETaTION Coastal vegetation can have a big impact on the long-term health and resilience of the Great Barrier Reef. Examples of such vegetation include: mangroves, freshwater wetlands, heaths, shrublands, grasslands and sedgelands, as well as woodlands, forests and rainforests.

Coastal ecosystems provide a range of ‘ecological services’ that support the Reef, including water distribution and filtration, food and habitat and nutrient and chemical cycling. Rivers and estuaries play a vital role in the life histories of many reef animals. For example, the larvae of some reef fish have even been found along streams more than 100 km inland.

405THE FUTURE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s last great wilderness areas. Stretching more than 2000 km along the coast of north-eastern Australia, the Reef is also the largest coral ecosystem on Earth. Its unique environment supports an astonishing and almost unequalled biodiversity, from microscopic plankton to whales, with many more species still to be discovered.

The human history of the Reef is no less intriguing. Indigenous Australians have known the Reef for millennia and their Dreaming stories offer tantalising glimpses of a truly ancient world. Europeans first encountered the Reef some 500 years ago on perilous voyages into unknown waters, but have only recently begun to understand its almost unimaginable complexity.

This book weaves these equally vibrant strands of natural and cultural heritage into a single narrative that leads the reader on their own voyage of discovery through one of the most beautiful places on Earth.

Also available from shop.qm.qld.gov.au:

Published by the Queensland Museum with the generous support of BHP Billiton Cannington

CLICK HERE TO PuRCHasE OnLInE

© QUEENSLAND MUSEUM

![Cayos Cochinos - X-Ray Mag...[2] Established as a key area of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System (the world’s second largest barrier reef, right after the Great Barrier Reef in](https://static.fdocuments.us/doc/165x107/5f7e05e420ed9b5c453b4fb6/cayos-cochinos-x-ray-2-established-as-a-key-area-of-the-mesoamerican-barrier.jpg)