The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

-

Upload

abelsanchezaguilera -

Category

Documents

-

view

345 -

download

2

description

Transcript of The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 1/27

The Form of Chopin's "Ballade," Op. 23Author(s): Karol BergerSource: 19th-Century Music, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Summer, 1996), pp. 46-71Published by: University of California PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/746667

Accessed: 25/07/2010 22:16

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unlessyou have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 2/27

T h e

o r m

o f

Ch opin s

Bal lade ,

O p

2 3

KAROLBERGER

The main

challenge facing

a

composer

of

a

relatively long

and

complex

work is

that of

continuity.

A

short

piece may

be

built

from

a

single phrase,

or a few

phrases arranged

n a

simple pattern

(such

as

Chopin's

favorite,

and

infinitely

varied,ABA).

In a

longer

work,

how-

ever,

the

question

arises: When the end of a

phrase

has been

reached,

what comes next?

Change

by

itself

is

easy

to achieve:

it is

enough

to

string

one

phrase

after another. The

difficul-

ties

begin

when one

wants not

just

one-phrase-

after-another

but

a continuous

discourse,

a

"configuration"

(to

use Paul Ricoeur's

term)

in

which "one-after-the-other"

becomes "one

because-of-the-other,"

a

whole rather than a

heap-that

is,

when

the

form

of the work is

"narrative"

as

opposed

to

"lyric."

In

a

separate

essay,

I

have

explained why

one

might

want to

understand narrative

and

lyric

as

the two most fundamental

forms

of

compo-

sition.'

In a

narrative

(ortemporal)form, partssucceed one anotherin a determined

order,

and

their

succession is

governed by

the relation-

ships

of

causing

and

resulting by necessity

or

probability.

On the other

hand,

in a

lyrical

(atemporal)

form,

the

parts,

whether

existing

simultaneously

or

succeeding

one

another,

are

governed by

the

relationship

of the

necessary

or

probable

mutual

implication.

Thus,

in

creat-

ing

a narrative

work,

one must not

only give

each

phrase

a function

within the

whole,

but

also

establish,

for

instance,

that the

later

phrases

are in

some

way

caused or

prepared by

some-

thing

that

happened

earlier

(although

not nec-

19th-Century Music XX/1 (Summer 1996).@by The Re-

gents

of the

University

of California.

'See

my

"Narrativeand

Lyric:

Fundamental

Poetic

Forms

of

Composition,"

in

Musical

Humanism and Its

Legacy:

Essaysin Honor of Claude V.Palisca, ed. N. K. Bakerand

B. R.

Hanning (Stuyvesant,

N.Y., 1992),pp.

451-70.

46

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 3/27

essarily

in

the

immediately preceding

phrase).

The

relationships

of

causing

and

resulting

are

the

main

means

of

achieving

narrative

conti-

nuity.

In

identifying

the main

problem

of

any large,

complex,

narrative

form with

continuity

and

its solution

with

probabilistic

causality,

one

need

not see either

issue

as

being

faced

only

by

the

composer.

The

listener

and the

performer

face

the same

problem

and have the same

means

of

solving

it at their

disposal.

Once

they

as-

sume

that

they

are

dealing

with a

single

work,

performersand listeners must attempt to de-

termine

(by

continuously proposing,

trying

out,

and

revising hypotheses,

in the

process

of

play-

ing

or

listening)

how the whole

is divided

into

parts

and

what function

each

part

has in

mak-

ing up

the

whole.2

And once

they

assume

that

the work

is

narrative,

they

must then look

for

the

relationships

of

causing

and

resulting

among

the

parts.

Both the problem and its solution pertainto

the structure

of

the work

itself,

as I shall

dem-

onstrate.

Neither

the

composer's

nor the

performer's

and

the listener's

thought

processes

will matter

here;

rather

what matter

primarily

are

the

constitution

and

significance

of the

world that the

composer's

work

presents

as an

occasion for the

performer's

and listener's

in-

terpretations-the

world

that,

after

all,

is al-

ways

someone's

interpretation

(in

this

case,

my own).

But it

would not

be

surprising

if

the

young Chopin

consciously

shared

the classicist

ambition

to create

wholes

rather than

heaps,

since this

was

clearly

the tenor of

the music

education that

he received

in Warsaw.

Indeed,

at the

beginning

of his

stay

in

Paris,

he received

a

letter

from his

composition

teacher,

J6zef

Elsner, writing

from Warsaw

on

27

November

1831,

advising

him that "the

concept

of the

whole

in

the work

is the mark

of a true

artist;

a

craftsman

puts

one stone

on

another,

places

one beam

on another."3

What

follows, then,

is an

exercise

in formal-

ist close readingof, in this case, Chopin's First

Ballade

in

G

Minor,

op.

23

(published

in

1836).

This is a silent

imaginary performance,

a read-

ing

that would be

followed most

profitably

with

the

score

in

hand.

Elsewhere,

in a

companion

essay,

Ihave

attempted

to show how one

might

subject

the

results of such

a

reading

to

a

further

interpretation

and

might

move

beyond

formal-

ism,

without

sacrificing

its

insights

and with-

out falling into the familiar trapat the bottom

of

which

waits,

grinning,

Hermann Kretz-

schmar.4

I

I

consider first the

"punctuation

form,"

the

way

the work is articulated

into a

hierarchy

of

parts

by

means

of

stronger

and weaker ca-

dences.5

Form,

after

all,

involves

a

relationship

between the parts and the whole, and if the

form is

temporal,

the

parts

succeed one an-

other.

In

the

last two

centuries,

musical form

has been

commonly

thought

of as

produced by

the

manipulation

of two

factors,

key

and theme.

The musical

form,

on this

view,

results from

an interaction

of a tonal

plan consisting

of

a

succession

of stable and unstable tonal areas

and a thematic

plan consisting

of an

exposi-

tion,

development,

and

recapitulation

of

themes.

This view

suppresses

a much

older,

"rhetorical"

onception

(Dahlhaus's

term),6

till

well remembered

by

theorists

in

the late

eigh-

teenth

century, whereby

a form results

in

the

KAROL

BERGER

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23

21

have

argued

that

the

unity

of the work

is the reader's

necessary,

not

optional,

assumption

in

"Diegesis

and

Mi-

mesis: The Poetic Modes and

the Matter of

Artistic Pre-

sentation,"Journalof Musicology

12

(1994),

407-33;

and I

have discussed the

temporal

nature

of the

process

of musi-

cal

interpretation

in

"Toward

a

History

of

Hearing:

The

Classic

Concerto,

A

Sample

Case,"

in Convention in

Eigh-

teenth-

and

Nineteenth-Century

Music:

Essays

in

Honor

of

Leonard

G.

Ratner,

ed. W.

J.Allanbrook,J.

M.

Levy,

and

W. P.

Mahrt

(Stuyvesant,

N.Y., 1992), pp.

405-29.

3"Pojqcie

calosci

w dziele znamieniem

jest

prawdziwego

artysty;

rzemie4lnik

stawia

kamienf

na

kamiefi, belkq

na

belkp

kladzie"

(Fryderyk Chopin, Korespondencia,

ed.

Bronislaw

Edward

Sydow,

vol.

I

[Warsaw, 1955], p. 198).

(All

translations

in

this article are mine unless otherwise

indicated.)

4See

my "Chopin's

Ballade

Op.

23

and the Revolution

of

the

Intellectuals,"

in

Chopin

Studies

2,

ed.

John

Rink

and

Jim

Samson

(Cambridge,

1994),

pp.

72-83.

5Foran introduction to the

concept

of

"punctuation

form"

and for an

explanation

of the

punctuation terminology

used

here,

see

my

"The First-MovementPunctuation Form

in

Mozart's Piano

Concertos,"

in Mozart's

Piano Concer-

tos:

Text, Context,

Interpretation,

ed. N.

Zaslaw

(Ann

Ar-

bor, 1996),pp.

239-59.

6Carl

Dahlhaus,

"Das rhetorische

Formbegriff

H. Chr.

Kochs und die Theorie der

Sonatenform,"

Archiv

fiir

Musikwissenschaft

35

(1978),

155-77.

47

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 4/27

19TH

CENTURY

MUSIC

first

place

from

"punctuation"

(to

speak

with

Koch),7

an articulation

of the

musical

discourse

by

means of

cadences

of

varying

strength.

The

cadentialpunctuationarticulatesthe whole into

successive

parts

and

provides

the

framework

within

which

the

respective

roles of

other for-

mal

factors,

of

keys

and

themes,

can be under-

stood.

By

the

1830s,

theorists

lost

much

of the

interest

in cadences

and

punctuation

that

ani-

mated their

predecessors

from

the

sixteenth

through

the

eighteenth

centuries.

Cadence

was

too

conventional

an

object

to

attract

much

at-

tention in an age that appreciatedoriginality

above

all

else and

found

it

in the

uniqueness

of

the

thematic

and

harmonic

invention

and ma-

nipulation.

But this

lack

of theoretical

interest

should

not blind

one to the

continued

impor-

tance

of

punctuation

in the

practice

of

a com-

poser

for

whom the

music of

Bach

and Mozart

continued

to

be

a

living

presence.

The

main

musical

discourse

of the

G-Minor

Ballade, the Moderato (in 6; mm.

9-208),8

is

framed

on

both

sides,

by

the

Largo9

ntroduc-

tion

(in

C;

mm.

1-8)

and the Presto

con fuoco

coda

(in

0;

mm.

209-64).

The two

parts

of the

frame could not

be less balanced: at the

begin-

ning, a mere eight measures, without so much

as a hint

of cadence

either

internally

or at the

end,

articulated

only by

brief

rests,

as

if

the

speaker

were short

of breath

or,

better,

still

turning

in

his

mind the

subject

of the about-to-

be-opened

story;

at the

end,

fifty-six

measures

7Heinrich

Christoph

Koch,

Versuch

einer

Anleitung

zur

Composition,

3 vols.

(Leipzig,

1782-93).

8Throughout

his

article,

I

measure

a section

from

its

first

melodic

downbeat,

no matter

how

long

the

preceding

up-

beat,

to

its last

melodic

downbeat,

even

when

the

first

melodic

downbeat

of the

next section

is simultaneous

with

this

last

downbeat

(i.e.,

even

when

the two

phrases

are

"elided"),or when the upbeatof the next section follows

immediately

in

the

same measure

(and

the

two

phrases

are

"linked").

9Largo

s the

indication

in

Chopin's

autograph

(formerly

in the

collection

of

Gregor

Piatigorski,

Los

Angeles)

and

in

the

French

first

edition

(Paris,

1836),

which was

certainly

prepared

on

the basis

of this

autograph

and

probably

proof-

read

by

the

composer.

In the

German

first

edition

(Leipzig,

1836),

the

indication

is

Lento. Of

the

two

principal

mod-

ern

editors

of

the

Ballade,

Ewald

Zimmermann

chooses

the

autograph

and

the

Schlesinger

edition

as the

basis

of

his

text,

implicitly

rejecting

the

readings

of

the

Breitkopf

and

Hartel

edition as inauthentic (see the "Kritischer

Bericht"

accompanying

Fr6deric

Chopin,

Balladen,

ed.

Ewald

Zimmermann

[Munich,

1976],

p.

3),

whereas

Jan

Ekier

argues

for the

authenticity

of

the

German

first edi-

tion, claiming

that

it was

"basedon

corrected

proofs

of

F

[the

French

first

edition]

on

which

Chopin

made a

number

of

additional

changes"

"Critical

Notes"

to

Fred6ric

Chopin,

Balladen,

ed.

Jan

Ekier

[Vienna,

1986], p.

xxi;

for detailed

arguments

on

which

this

conclusion

is

based,

see the

Komentarze

ir6ddowe

published

with

Fryderyk

Chopin,

Ballady, Wydanie

Narodowe

A.1,

ed.

Jan

Ekier

[Cracow,

1970]).

Ekier's

claims

for the

authenticity

of the German

first edition do not convince. (Compare also Zofia

Chechlinfska,

"The

National

Edition

of

Chopin's

Works,"

Chopin

Studies

2

[1987],

7-19.)

He

asserts,

for

instance,

that

a

change

of

tempo

indication

was too

major

a

revision

to

have

been

introduced

by

anyone

other than

the com-

poser,but he himself refers

to a number

of

Chopin's

works

where

tempo

indications

differ between

the

French and

German

first

editions,

without

being

able

to

show that

these

differences

can

be attributed

to

Chopin.

Similarly,

he claims

that

the celebrated

Breitkopf

and

Hirtel

reading

of the

left hand

in

m.

7,

with

d

instead

of

eb1,

represents

too

important

a revision

to

have been

introduced

without

the

composer's

authorization,

but since-as

Ekier

himself

notes-the

revision

corrects

the

parallel

fifths between

the

right

and left hands

(mm.

6-7),

it

might

well have

been

introduced

by

a

pedantic

house editor

in

Leipzig.

By

claim-

ing

that

Breitkopf

and

Hirtel

based

their

text on

corrected

proofs of the Schlesinger edition, Ekier ignores the fact

that

a

manuscript

of the

Ballade,

whether

the

composer's

autograph

or a

copy,

was

still

in the

possession

of

the

Leipzig

publishers

in

1878

(see

their

letter

to

Chopin's

sister,

Izabela

Barciflska,

dated

Leipzig,

1

February

1878,

quoted

and

discussed

in

KrystynaKobylafiska,

Rekopisy

Utwor6w

Chopina:

Katalog,

vol.

I

[Cracow,

1977],

p.

126;

see also

Kobylafiska,

Frederic

Chopin:

Thematisch-

bibliographisches

Werkverzeichnis,

ed.

Ernst

Herttrich,

trans.Helmut

Stolze

[Munich, 1979],

p.

46).

Most

likely,

the

German

first

edition

was based

on

this

manuscript

andnever

proofread

by

the

composer.

(See,

however,

n.

19

below.) This would be fully consistent with Chopin'snor-

mal

publishing

practices,

as described

by

Jeffrey

Kallberg

("Chopin

n

the

Marketplace:

Aspects

of the

International

Music

Publishing

Industry

in

the

First

Half

of the

Nine-

teenth

Century,"

Notes 39

[1982-83],

535-69,

795-824):

"Throughout

his

career,

he

would

ordinarilygive

an

auto-

graph

manuscript

to

the

French

publisher

for

use

in en-

graving

he edition.

...

In his

middle

years

(roughly

1835-

41), copyists

were allowed

to

read over

proofs,

and

at

least

some

of the

time,

Chopin

would

check

over

these

copyist-

corrected

proofs

before

submitting

them

to the

publisher.

But

during

these

years,

Chopin

did

not

entirely

relinquish

proof-reading ... [p. 551]. Until mid-1835, Chopin's Ger-

man

editions

were

engraved

from

printed

proofs

originat-

ing

in France.

From ate

1835

through

the

remainder

of

his

career,

manuscripts

were

as a

rule

sent

eastward.

As

in

France,

the

years

1835

to

1841 saw

copyists'

manuscripts

employed

along

with

autographs

....

Most

of the

manu-

scripts

were

reviewed

by

Chopin

prior

to

being

forwarded

to

Leipzig

.

.

[pp.

808-09].

While

the

composer

in

his

early years

and

once

or

twice

later

sent

proofs

of

his

music

to

Germany

to

serve

as

engraver's

copy,

no case

is

known

where

he corrected

proof

sheets

engraved

by

one

of

his

German

publishers.

Once

his

music

in whatever

form

...

left his handsforLeipzig,Vienna, or anotherGermanpub-

lishing

center, Chopin's

ability

to

oversee

the

musical

text

ceased"

(pp.

815-16).

An

important

additional

consideration

should

be

men-

48

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 5/27

of

emphatic

peroration,

ending

(in

m.

250)

with

a cadence

whose

powers

of

closure

are

enhanced

as much

by

the

length

of the dominant

preced-

ing the final tonic (mm. 246-49) as by the dura-

tion

of the

appendix

prolonging

the tonic

(mm.

250-64),

and

articulated

internally

by

three

weaker

cadences

(mm.

212,

216,

224).

In

spite

of

(or

rather

because

of)

the introduction's

hesi-

tant

and

open

character

at the

beginning,

the

design

is

insistently goal-oriented

and closed

at

the end.

This

is a discourse

in search of

an

aim.

Once the

aim

is

reached,

it

is

repeatedly

stressed. One could imagine a number of ways

in which the

"speaker"

might

have eased

his

way

into the

Moderato,

but

after the

Presto

absolutely

nothing

remains

to

be said.

The Moderato

itself

preserves

unmistakable

traces of the

sonata-allegro

tradition.

The

regu-

lar

first

period

(mm. 9-90),

to

speak

in

punctua-

tion terms

(or,

in thematic

terms,

the

exposi-

tion),

consists of

two balanced

(antecedent-con-

sequent) phrases (mm. 9-36 = 8 mm. + 20 mm.;

and

mm. 68-82

=

8

mm.

+

7

mm.),

the

first

followed

by

three

appendixes

prolonging

the

final cadential

tonic of the

phrase

(mm. 36-44,

45-48,

and

49-56)

and the second

by

one such

appendix

(mm. 83-90).

The

two

phrases

are

connected by a twelve-measure unpunctuated

and

uncadenced

transition

(mm. 56-67).

As is

the

norm

in

Chopin's

sonata

practice,

the ab-

breviated

ast

period

(the

recapitulation)

restates

only

the second

half of the

"expositional"

first

period,

that

is,

only

the second balanced

phrase

and

its

appendix

(mm.

166-88

corresponding

o

mm.

68-90).

But

what

happens

n between these

two

broad

periods

(mm. 91-166)

and after

them

(mm. 189-208) defies any explanation in terms

of

the

sonata-allegro

tradition.

For want of

bet-

ter

terms,

one

might

speak

in a

preliminary

fashion

of

a

complex two-part

transition

(mm.

91-137)

preparing

he central

episode(mm.

138-

66)

and

another,

simpler

one-part

transition

(mm.

189-208)

preparing

the coda.

Now it is

immediately

apparent

hat

the latter transition

(mm. 189-208) corresponds

o

(or

recapitulates)

the first partof the former transition (mm. 91-

106)

in its

punctuation

form

as

well

as its

har-

monic and thematic

content: the

four mea-

sures of modulation

ending

with

a hint of a half

cadence

(mm. 91-94)

are

recapitulated

in six

measures

(mm. 189-94),

and the twelve-mea-

sure

appendix prolonging

the cadential

domi-

nant

(mm. 95-106)

is

recapitulated

in

twelve

measures

(mm.

195-206)

and followed

by

a

two-

measure appendix that resolves the dominant

to the tonic

(mm. 207-08).1o

Moreover,

the

cen-

tral

episode

(mm. 138-66)

resembles

in

its

rela-

tive

harmonic

stability

and

especially

in

its

KAROL

BERGER

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23

tioned here.

As far as

I

know,

none of

the student

exemplars

of the Ballade that survive

with

the

composer's

autograph

annotations correctsthe

introductory tempo

indication or

the

left-handchord

n m. 7 to conform

with the

Breitkopf

nd

Hirtel readings.(See Kobylafiska,Rekopisy,I, 127; idem,

Werkverzeichnis,

p.

46;

Frederic

Chopin,

CEuvres

our

pi-

ano:

facsimil

de

l'exemplaire

de

Jane

W.

Stirling,

ed.

Jean-

JacquesEigeldinger

and

Jean-Michel

Nectoux

[Paris,

1982]).

Thus,

in

the

unlikely

case

that these

readings

tem

from the

composer

himself, they

would

represent

an

ultimately

re-

jected

momentary

hesitation

on his

part.

Finally,

an

early

autograph

of the first fifteen

or

sixteen measures

of the

Ballade,

known to exist

in

a

private

collection,

is also

marked

Largo Kobylafiska,

Werkverzeichnis,

Erginzungen:

Berichtigungen,"

Musikantiquariat

Hans

Schneider,

Bedeutende

Musikerautographen,

Catalog

No.

241

[Tutzing,

1980],p. 16).Insum,while completecertainty n this matter

is

unlikely

(unless

the

manuscript

mentioned

in

Breitkopf

and

Hirtel's

letter to

Barcifiska

comes

to

light),

it seems

most

plausible

to conclude

that the

readings

ransmitted

n

the German first edition are

not authentic

and

that the

authorized ext is best

represented

by

the

French irst

edition

read

n

conjunction

with the

autograph

nd

whatever

can be

learned rom the annotations

n

the

exemplars

hat

belonged

to the

composer

or his students.

Needless

to

say,

this

conclusion

in no

way

detracts

from the

interest that

the

Breitkopf

and

Hartel

readingsmay

hold

for

the

student of

the

performance

and

reception

history

of

the work outside

FranceandEngland.Heinrich Schenker'sargument n favor

of

the German

reading

of

m.

7

is as

telling

as

it is unconvinc-

ing.

See

Schenker,

Der

freie

Satz

(2nd

edn.

Vienna, 1956),p.

110 and

fig. 64,

ex.

2.

'oGiven

the

very

close

correspondence

of mm. 189-208

and

91-106,

no

analyst

that

I

am aware

of considers the

latter section

to be a

part

of the

exposition,

and

Chopin's

well-known practice of recapitulatingnormally only the

second

half of the

exposition,

it is

puzzling

that so

many

analysts

of

op. 23, including

most

recently

even

the

usu-

ally

admirablyperceptive

Jim

Samson, identify

a mirror

or

symmetrical

recapitulation

(with

the first theme

recapitu-

lated

after the second

one)

in

the

work.

Compare

Jim

Samson,

Chopin:

The Four Ballades

(Cambridge,

1992),

pp.

45-50.

The most

noteworthy analyses

of the Ballade

to

appear

after Samson's

book are

John

Daverio,

Nine-

teenth-Century

Music and

the German Romantic Ideol-

ogy

(New York,

1993),

pp.

39-41,

and Charles

Rosen,

The

Romantic

Generation

(Cambridge,

Mass., 1995), pp.

323-

28. Daverio talks of "an overridingpalindromic form" (p.

40). Rosen,

on the other

hand,

considers both returns

of

theme

A

as "a ritornello"

or "a refrain"

p.

327)

and avoids

any suggestion

of a

recapitulation.

49

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 6/27

19TH

CENTURY

MUSIC

punctuation form,

although

not

in

its thematic

content,

the

coda

(mm.

209-64):

both

consist of

three

short incises followed

by

a

very

large

one

(in the episode, three four-measureincises are

followed

by

a

seventeen-measure

one;

in the

coda,

two incises of four

measures each

are

elided

with one of nine

measures,

which is

elided in

turn with a

twenty-seven-measure

one,

followed

by

a fifteen-measure

appendix).

I

shall show that the

correspondences

between

the

episode

and

the

coda

go

further than

that.)

Thus

only

the second

part

of

the first transition

(mm. 106-37) seems to be left without a direct

recapitulation

or at least a

corresponding

sec-

tion in the last third of the

piece.

Since this

is,

however,

a

developed

restatement of the

sec-

ond balanced

phrase

of the main

period

(mm.

106-26

=

8

mm.

+

13

mm.,

corresponding

to

mm. 68-82

=

8

mm.

+

7

mm.),

this time

ending

with a half rather than full cadence

(m.

126),

with

the

final

cadential dominant

prolongedby

the following appendix(mm. 126-37), even this

music finds its

corresponding

counterpart,

if

not an

exact

restatement,

at the

beginning

of

the

recapitulation

(mm. 166-88).

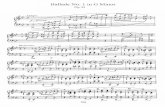

Figure

1

summarizes the

punctuation

form

of the

Ballade.

(The

recapitulating

sections are

linked with the sections

they recapitulate by

continuous

vertical

lines;

sections

correspond-

ing

in some

other,

weaker

way

are

linked

by

interruptedlines; I andV mark sections ending

with a

full

or half

cadence,

respectively;

+I

and

+V

in

parentheses

mark

appendixes prolonging

the final tonic

or dominant of

the

preceding

cadence,

respectively;

1 indicates that the sec-

tion is

linked

with the

following

one,

e-that

it

is elided

with the

following

one;

Arabic numer-

als count

measures within

a

section.)

Several

points clearly emerge.

First,

the norm

underly-

ing Chopin's balancedphrases (that is, the an-

tecedent-consequent phrases

that

present

the

two main

themes)

seems to be

two

eight-mea-

sure

incises,

but the

norm

is

obeyed (estab-

lished)

in the first incise

only

to be

departed

from in the second.

In

the first

(unrecapitulated)

phrase (mm. 9-36),

the

generous

expansion

of

the second incise to

twenty

measures

may per-

haps

adumbrate the overall end-oriented

shape

of the work. Even if all parenthetical repetition

(mm.

24-25

repeat

mm.

22-23)

as

well as the

parenthetical expansion

of the

penultimate

cadential

dominant

(mm.

32-35-the

only

mea-

sures

that could

be

removed from

the incise

without a loss of

motivic

substance

or

gram-

matical integrity)were removed from the sec-

ond

incise,

a

sizable

consequent

of

fourteen

measures would still

remain. On

the

other

hand,

the

behaviorof

the

second

(recapitulated)

hrase

(mm.

68-82 and

166-80)

is

quite

different. Here

the

slightly

shorter

consequent

weakens the

sense of

closure and

necessitates a

continua-

tion.

(When

the

phrase

is

recapitulated/devel-

oped

in mm.

106-26,

the

consequent

is made

longerto make room fora modulation.)Whereas

the

balanced

phrases

are

conceived

in

terms of

the

eight-plus-eight

norm,

the

episode

and the

coda

suggest

another

underlying

norm,

an

addi-

tive

construction

of

four

four-measure

incises

(I

shall offer

arguments

for this

reading

later),

with the norm

observed

only

in

the first two or

three

incises,

and with an

enormous

expansion

of the

last incise.

(Together

with the conse-

quent of the first phrase, these are by far the

largest

incises of the entire

work.)

Once

again,

the end-oriented

shape

of

the

whole is reflected

in

the structure of

these two sections.

This

contributes to the sense of a discourse that

constantly

yearns

for

(and

finally

attains)

an

emphatic

conclusion.

Second,

the

handling

of the cadences shows

an

abiding

concern for

continuity.

To be

sure,

the discourse is marked by a number of ca-

dence

articulations,

and all are

additionally

strengthened by

one or more

appendixes

pro-

longing

their final

chords.

Nevertheless,

these

cadences

and

appendixes

(save,

of

course,

the

last

one)

are either linked or elided

with the

following

music.

This ensures that the sense

of

articulation is never

very

strong-never

as

em-

phatic,

for

instance,

as the one

commonly

en-

countered at the end of the first period(exposi-

tion)

of the Classical

sonata-allegro.

In

addition to

such obvious devices

as

the

link and the

elision,

Chopin

also

uses

subtler

ways

of

smoothing

over

the

joints

between

suc-

cessive sections. The

introduction,

for

example,

is left without a cadence.

The cadence

that

should have

closed it comes at the

first down-

beat of

the

following phrase (m.

9),

but because

this downbeat is preceded by an upbeat, this is

not

a normal case of elision

(in

which the

last

melodic downbeat

of a

preceding

section

and

50

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 7/27

Measure:

1 9

36

45 49

56 68

83

91 95

106

126

13

81 81+

20e

(5e

+

51)

(21[21])

(8e)

121

81+ 71

(41[41])

41

(12e)

81+13e

(121)

41,

Punctuation:

Ie

(+

11)

(+II)

(+

Ie)

II

(+I )

VI

(+Ve)

Ve

(+V1)

Section:

Intro.

First

period:

Transition:

Ep

phrase

1

Transition

phrase

2

part

1

part

2

Measure:

166

181

189

195

207

20

81+ 71

(41

41])

61

(121)

(21)

41,

Punctuation:

II

(+I )

VI

(+Vl)

(+I )

Ie

Section:

Last

period:

Transition:

Co

phrase

2

part

1

Figure

1:

The

Punctuation

form

of

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23.

U,

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 8/27

19TH

CENTURY

MUSIC

the

first of

the

following

one

coincide).

Instead,

the

melody

of the

introduction

is

interrupted

in

midstream

rather

than

concluded,

and it

is

only covertly

continued

through

the

upbeat

and

first

downbeat of

the

following

phrase.

One

might

call this

a

superelision.11

Similar

cases

of

superelision

occur at the

ends of the

only

other

two

sections that lack

cadences,

the

transition

between

the

first and

second

phrase

of the

first

period

(mm.

56-67)

and the

episode

(mm.

138-

66), parallel spots

to

the extent

that

both

pre-

cede the

same

material,

the second

phrase

of

the period. In the formercase, the cadence oc-

curs in

m.

69,

that

is,

one

measure

after the

new

phrase

had

begun

(on

the

last

quarter

of

m.

67).

Like the

introduction,

the

transition

is

in-

terrupted

in

midstream and

only covertly

con-

tinued as the new

phrase begins

with the

same

dyad

the transition

died out on.

And

similarly,

the

cadence that should

have endedthe

episode

is

delayed

until m.

167,

that

is,

one

measure

after the beginning of the next phrase. The

melodic link

(the

dyad)

between the

episode

and the

following

phrase

is

lacking

this

time,

but the harmonic bond

between them

is much

stronger,

since the cadence

begins

within

the

episode

and is

completed

within

the

phrase:

the cadential

dominant is reached

in

m. 158

in

the form of the six-four

(EL) hord,

which is

prolonged

through

the

downbeat of m. 162 and

resolvedby way of the chromaticpassingchords

in

mm.

162-65 to

the

V5(BM)

hord at the

begin-

ning

of the new

phrase

in

m.

166.

Here,

as

throughout

the

Ballade,

Chopin's

evident

goal

is to

punctuate

without

stopping,

to

suggest points

of articulation

without

im-

peding

the drive toward the final

destination.

The

composer's

concern

with

such issues

may

be

graphically

illustrated

by

his subtle revision

of the phrasingin mm. 54-5 7. In the autograph,

mm.

54-55

(i.e.,

the last two measures of the

final

appendix

to the first

phrase)

are

placed

under one

slur,

and

mm.

56-57,

the first two

measures of the

following

transition,

are

placed

under another.

In this

way,

Chopin

originally

marked a

point

of

articulation

between the

ap-

pendix

and the

transition

very

clearly.

In

the

French

first edition, however, he decided to

cover all four

measures

with a

single

slur,

thus

increasing

the

sense of

continuity

between the

two sections.

Third,

full

cadences are

used

to close the

relatively

stable

sections

that

state or

restate

their material

(the

two

balanced

phrases

of both

periods

and the

coda),

and

half

cadences close

the

relatively

unstable

sections,

with the

func-

tion of preparing he appearanceof the follow-

ing,

more stable sections

(the

two

phrases

of

transition).

Here

Chopin

strictly

observes

the

Classical

usage.

The

central

episode, however,

is

anomalous,

since-as

observed

earlier-it

promises

to

close with

a full

cadence but

post-

pones

its

completion

until

after the be

inning

of the next

phrase

and ends on

the

V3

chord.

This

imaginative

ending

makes it at

once a

section of relative stability and transition.

Fourth,

the

relative

strength

of a cadence

depends

primarily

on the

length

of its

domi-

nant;

observe

where the

strongest

cadences oc-

cur and

how

they

are handled.

The

dominants

of

longest

duration

are

placed

as

follows:

mm.

94-106

(thirteen

measures),

the

appendix

of the

first

part

of the

transition

between the

first

period

and

the central

episode

through

the

first

measure of the following phrase (anothercase

of the

superelision

that

always precedes

the

appearance

of this

material);

mm.

126-37

(twelve

measures),

the

appendix

of the

second

part

of the

first

transition;

mm. 158-66

(nine

measures),

the

already

discussed

cadence

supereliding

the

episode

with

the last

period;

mm.

194-207

(fourteen

measures),

the two

ap-

pendixes

of the second

transition;

and

mm.

238-49 (twelve measures),the final cadence of

the work. It is clear

that once the main the-

matic material has been

presented,

that

is,

im-

mediately

after the first

period

(exposition),

the

discourse consists

essentially

of one

strong

cadential

statement after another.

Although

there are no

seriously prolonged

dominants

through

the end of the first

period (the only

dominant-prolongation, lasting

four-and-a-half

measures, occurs at the cadence of the first

phrase,

mm.

312-35), every phrase

after

the

first

period,

with the sole

exception

of

the

"The articulation between the introduction and the first

period

is

further

weakened

by

a subtle textural

transition,

as the monophony of the paralleloctaves in mm. 1-5 gives

way

to

the

first hint of the

homophonic, melody-with-

accompaniment,

texture in mm.

6-7,

thus

preparing

he

homophonic

texture

of the first

period.

52

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 9/27

Measure:

1

9

36 45 49 56 68 83 91 95 106 126

138

Theme/motif:

a

A al a2 a3 x B b "b" "A" "B"

y

C

I

-->

(V)

wt"Vb"-l-

(V)

I

Key: (V) i -- "VI"/VI VI

Punctuation:

Ie (+ Il)

(+I1)

(+

Ie)

Il

(+II)

V1

(+Ve)

Ve

(+Vl)

Section:

Intro.First

period:

Transition:

Episode

phrase

1

Transition

phrase part

1

part

2

Measure:

166 181 189 195

207

209

250

Theme/motif:

B b "b" "A"

z

D

"A"

Key:

--

(V)

i

Punctuation:

II

(+II)

V1

(+Vl)

(+II)

Ie

(+I)

Section:

Last

period:

Transition:

Coda

phrase2 part1

KAROL

BERGER

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23

Figure

2: The

Harmonic

and thematic

plans

of

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23.

recapitulatory

phrase

of

the

last

period,

ends

with

a

seriously prolonged

dominant.

But it is

noteworthy that only one, the final, of these

strong

cadences

is suited

to conclude

the dis-

course,

since

only

it is

simultaneously

a

full

cadence and has

a final tonic

prolonged by

an

appendix.

The

impression,

again,

is of

a

dis-

course

in

search of

a

suitably strong

conclu-

sion,

reached

only

after a

number of less suc-

cessful

rehearsals.

II

In

music

analysis

the

"what"

questions,

al-

though indispensable,

are

generally

less

inter-

esting

than the

"why" questions.

It

is

clear at

this

point

what

the

punctuation

form

of the

Ballade

is,

but not

why

the work has this form

rather than another.

To make

the

first

step

in

this

direction,

I shall turn to the harmonic

and

melodic matter

of the musical discourse.

Fig-

ure 2 summarizes

the harmonic and thematic

plans

of the

work,

mapping

them

against

the

already

identified formal

units.

Upper-and

lowercase Roman

numerals stand for

major

and

minor

keys

respectively;

an arrow marks a

modulation;

V in

parentheses

signifies

the domi-

nant

preparation

of the

following

key;

quota-

tion marks around

a

Roman

numeral indicate

that the

key

in

question

has

not been

adequately

prepared,

that we are

"on,"

but not "in"

it,

as

Tovey

would

say;

a

key

is crossed-out

when it

is

prepared

but withheld.

Capital

letters iden-

tify major

thematic

ideas,

lowercase

letters,

with or without Arabic

numerals,

identify

mi-

nor motivic ideas that serve to individualize

less

important

formal

units,

such as

appen-

dixes;

quotation

marks

around a

letter indicate

that the theme

in

question

is

being

developed,

rather

than

stated.

Through

the end of the first

period,

the har-

monic

plan

of the Ballade more or less meets

sonata-allegro expectations,

at

least

to

the ex-

tent that

it

establishes the

main

key,

modu-

lates,

and establishes the second

key.

After-

ward,

it

goes

its

own

way.

To be

sure,

the

further modulation one

might

expect

does oc-

cur,

but,

instead of

leading

toward new har-

monic

regions,

it

circles back to the second

key;

and the retransition and

reestablishing

of

the main

key

occur

much later

than

they

would

in a

sonata-allegro.

Thus,

the basic

plan

con-

sists of two

tonic

areas

of

roughly

similar

di-

mensions at the

beginning

and end

framing

a

much

longer

(more

than twice

as

long

as either

of

the two tonic

regions)

central submediant

area,

the latter

in

three

parts:

a

tonally

stable

one

corresponding

to the

second

phrase

of

the

first

period;

an unstable one

corresponding

to

the

transition;

and another stable one corre-

sponding

to

the

episode

and last

period.

In ef-

fect,

two tonal

recapitulations

can be

identi-

fied,

one

occurring

before and one after the

thematic

recapitulation:

the return of the

submediant

in m.

138

and

of the tonic

in

53

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 10/27

19TH

CENTURY

MUSIC

m.

209.

It

is

worth

observing

that

there

is

rela-

tively

little tonal

instability

in

the

piece;

the

principal

areas

of

instability

are

confined

to

the

transitions.

Otherwise,

the

discourse is

remark-

ably

reluctant to

modulate

and

proceeds

in

broad,

stable tonal areas of either the tonic or

submediant. Measured

against

the

sonata-alle-

gro expectations

raised

at the

beginning,

the

most

striking

feature

of

this tonal

plan

is

the

postponement

of the

main

key's

return until

the

coda,

that

is,

until well after the thematic

recapitulation

had been

completed.

This shift

of the tonic's return from the point where it

would

coincide with the

beginning

of

the

the-

matic

recapitulation

to the

beginning

of

the

coda,

lending

so

much more dramato the

point

of

return,

confirms

and reinforces our sense of

the

work's

general shape

as imbalanced

and

end-oriented.

A

few harmonic details

deserve additional

comment.

First,

the dominant

preparation,

he

essential harmonic content of the introduction,

emerges

only

gradually

out of the

opening

II6

(Neapolitan

sixth)

chord;

ts first elements show

up only

in

m.

3,

which

emphasizes

c3

and

f#2,

the

two

indispensable

pitches

of the

V7

chord,

itself

fully

spelled

out

only

after the introduc-

tion

is

over

in

m.

8. This

beginning

is

harmoni-

cally

as

strikingly

reluctant as

the

ending

will

be

strikingly

emphatic.'2

The

specific harmony

Al, which dominates the first three measures

and out

of which

the dominant

emerges,

may

hint at the

importance

the

pitch

Ab

will

have

in

the

tonal

plan

of

the

whole,

as

it is

the

only

step

of the submediant

key

missing

from the

tonic G minor.

Second, Chopin's already

noted reluctance

to modulate is

nowhere

more

evident than

in

the

transition

between

the two

key

areas of

the

first period.He not only follows the first phrase

with three

appendixes,

thus

postponing

the

moment

when

the

tonic

key

will have to

be

abandoned,

but

also continues

to hesitate

even

after the

transition

gets underway

in m.

56.

Strictly

speaking,

there is no

real modulation

here,

in

the sense of an

adequate

preparation

of

the

following key-only

a

chromatic sliding

down of the

bass from

GG

in

m.

56

through

GGl

in

m.

62

to FF in m.

63,

all

of

which

is

executed with

such vacillation that until the

downbeat of

m. 63

the

music could

still

slide

back

easily

to

g

minor. As a

result,

when the

new

key,

El

major,

appears

n

m.

68,

it

is

quite

unprepared,

and even the cadence in m.

69

is

not sufficient to

stabilize

it. In

fact,

the tonal

instability of the second phrase is initially so

great

that it

is

not even clear whether

El or Bl

will be

its

key:

the

hint

of

a

cadence

in

El

at

the

end of the first incise

in

m. 69 is

immediately

followed

by

another hint of a cadence

in Bl at

the

end of

the

second incise

in

m.

71.

For

a

strong

cadential confirmation of

the

second

key,

one must wait until the end of the

second

phrase

in

m. 82. Like the

whole

Ballade,

the second

phrasemoves from an ambiguous, hesitant be-

ginning

to

a

clearly

defined

goal

at the

end.

The

remarkable reluctance

with which the

main

key

is

abandoned and

the second one

reached

contrasts

strongly

with the

normal Classical

practice

of an

energetic

drive toward

the sec-

ond

key (although

the

concealing

of

a

hint

of

what this second

key might

be

in

the

first

mea-

sures of the work does

have Classical

prece-

dents).The relative lack of a forwardharmonic

drive

is

compensated

for,

at least

in

part,by

the

seamlessness

of the transition

from the

main

to the second

key

area

and,

again,

this

is

in

contrast

with the normal

Classical

practice

of

placing

a

strong

point

of

'articulationbefore

the

second

phrase.

Needless to

say,

Chopin's

mas-

tery

of the

mechanics

of modulation

cannot

be

in

doubt.

Rather,

his aesthetic

goals

are

differ-

ent from those of his Classical masters. At

every step

one discovers

that

he aims not

for

the

Classical

balance

and

symmetry

of

clearly

articulated

formal

units

but for

an overall

shape

that

projects,

from

an

unassuming

and

reluc-

tant

beginning,

a sense

of a

relatively

seamless,

gradual

accumulation

of

energy

and

accelera-

tion toward

the

inevitable,

frantic

conclusion.

Third,

the

longest

section

of tonal

instabil-

ity in the Ballade, the transition between the

first

period

and

the

episode, represents

a move-

ment within

the second

key,

rather

than

away

'2Moreover, t

is

reluctant

not

only

harmonically

but

also

texturally,

with the

gradual

emergence

of

homophony

out

of

monophony,

and

rhythmically,

with measured

rhyth-

mic differentiationof values emergingonly graduallyout

of the

initial

lack

of

metric

definition

and

rhythmic

differ-

entiation;

on

every

level,

mm. 6-7 furnish

the crucial me-

diating

step.

54

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 11/27

from it.

The new

key,

BN

enharmonically

no-

tated

as A

(I

shall offer

my

reasons for this

interpretation

later),

is

adequately

prepared

by

the dominant-function six-four appendix in

mm.

94-105

(strictly speaking,

its

parallel

mi-

nor,

b

,

is

prepared),

but

the

confirming

BN-

major

cadence is

reached

only

in m.

107,

after

the

beginning

of the next

phrase

on V7 of

the

new

key

in m. 106

(the already

discussed

superelision);

because toward the end

(from

m.

118

on)

the new

phrase

initiates

a

move

back

to E6and ends

with a

half

cadence

in that

key

(or rather its parallel minor), the key of B? is

never confirmed

by

a

full cadence

coinciding

with either the

beginning

or end

of the

phrase.

The

daring

diminished-fifth

relationship

be-

tween

E6

and

B?

is

certainly

noteworthy,

defin-

ing

as

it does the

high point

of

harmonic insta-

bility

in the work.

Chopin,

who

loved to

flatten

the fifth

degree

of

a

chord,

here transfers

his

predilection

from the

level of chordal structure

to that of key structure.

The thematic

plan

of

the

Ballade,

like the

harmonic

one,

follows

the

sonata-allegro

model

through

the end of the first

period,

to

the

ex-

tent at least

that

it

presents

two

thematic

ideas

in

two different

keys,

and

alludes

to them once

more in the last

period,

where the second

theme

is

recapitulated,

although, against

all sonata

precedents,

in the second

rather than the main

key. This lack of correlation between the the-

matic and harmonic

recapitulations

and the

introduction of two new thematic

ideas,

C

and

D

after

the

first-period

exposition,

constitute

the two

most

striking

features

of the

thematic

plan

as

measured

against

the

sonata-allegro

ex-

pectations

raised at the

beginning.

The

two

features

are related to this extent:

that the sec-

ond theme is

recapitulated

in

the

subsidiary

rather than main key necessitates the continu-

ation of

the discourse

beyond

the end of the

last

period

so

that the main

key

can

return in

the coda. The introduction of

a new theme at

the

point

where the tonic

key

returns

gives

this

point

additional

emphasis

and

importance

and

confirms our fundamental

reading

of the over-

all

shape

of the work

as

focused on the final

goal.

Like theme

D,

theme C itself articulates

and

emphasizes

the arrival of the tonal reca-

pitulation:

it has been noted

above that the

Ballade

contains two such

points

of tonal re-

turn,

first

to the submediant

in

m. 138 and

second

to the tonic in m.

209.

This

and

because

C

and

D

are

the two new themes introduced

after the first-period exposition further

strengthen

the

correspondence

between

the

epi-

sode

and the

coda

already

noted on

the

basis of

punctuation

alone. In

fact,.the

correspondence

goes

even

deeper:

both themes have a similar

motivic

construction.

The four

incises of both

themes,

C and

D

(see fig. 1),

are filled with

motivic

content

that could be labeled mmnn'-

that

is,

in

terms

of the motivic

content,

the

second incise repeatsthe first, while the fourth

wants to

repeat

the

third, but,

unable to con-

tain

its

energy,

bursts its

limits

as

if

losing

self-

control

in

a

giddy

rush

to

the cadence.

Thus

the

episode

takes on the

appearance

of a re-

hearsal

for the

coda,

and the whole

sequence

of

events

from m.

166

on can be read as

a

rectifi-

cation of the

sequence

of events

from m.

68 to

m.

165,

as

if

the search

for a

proper

conclu-

sion-the essential content of the work-did

not

get

it

right

the first

time

and

had

to

be

repeated

and corrected on second

try.'3

KAROL

BERGER

Chopin's

Ballade,

op.

23

'3Needless

to

say,

the

similarity

of the overall thematic

plan,

a-b-b1

(mm. 1-67, 68-165,

and 166-264

respectively),

to the form

of the

medieval ballade

is

fortuitous.

In

choos-

ing

a

name for the

genre

his

op.

23

was

to

inaugurate,

Chopin

was

certainly inspired by

the tremendous Euro-

pean vogue for the poetic ballad among the Romantics,

and

in

particular

by

that

virtual

manifesto

of

Polish liter-

ary

Romanticism,

Adam Mickiewicz's collection of

Ballady

i

Romanse

(Ballads

and

Romances)

of

1822. There

is no

good

reason

to distrust Robert Schumann's

testimony

in

this matter:

"He

spoke

then

[when

he met Schumann in

Leipzig

on 12-13

September

1836]

also of the

fact that

he

got inspiration

for his ballads from some

poems

of

Mickiewicz"

(Er

sprach

damals auch

davon,

daf

er zu

seinen

Balladen

durch

einige

Gedichte

von

Mickiewicz

angeregt

worden

sei.) (Schumann,

Gesammelte

Schriften

fiber

Musik und

Musiker,

vol.

II,

ed. M.

Kreisig

[5th

edn.

Leipzig, 1914],p. 32).See, however,ChristianeEngelbrecht,

"Zur

Vorgeschichte

der

Chopinschen

Klavierballade,"

n

The Book

of

the

First International

Musicological

Con-

gress

Devoted to the Works

of

Frederick

Chopin,

Warszawa

16th-22nd

February

1960,

ed.

Zofia

Lissa

(Warsaw,

1963),

pp.

519-21;

Giinther

Wagner,

Die

Klavierballade um

die

Mitte

des

19.

Jahrhunderts,

Berliner Musikwissen-

schaftlicheArbeiten9

(Munich-Salzburg,

976),

pp.

42-48;

and Anselm

Gerhard,

"Ballade und Drama:

Frederic

Chopins

Ballade

opus

38

und

die franzbsische

Oper

um

1830,"

Archiv

ffir

Musikwissenschaft

48

(1991),

110-25.

See also

James

Parakilas,

Ballads Without Words:

Chopin

and the Tradition of the Instrumental Ballade(Portland,

Or.,

1992),

pp.

26-27. For the date

of

Chopin's

meeting

with

Schumann,

see Schumann's

letter to Heinrich Dorn

in

Riga,

written

in

Leipzig

on

14

September

1836: "Eben

55

7/17/2019 The Form of Chopin's Ballade, Op. 23

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/the-form-of-chopins-ballade-op-23 12/27

19TH

CENTURY

MUSIC

I

have

commented

above on

the

relative lack

of tonal

instability

in

the

Ballade.

Similar

and

closely

related to

it

is the

scarcity

of

genuine

thematic development in the piece-and the

little

there is is

confined to

the two

transitions,

just

as the

areas of

harmonic

instability

were.

Even

many

of

the

passages signaled

by quota-

tion

marks in

fig.

2

as

developmental

do

not

quite

live

up

to the Classical

image

of

thematic

working:

mm.

91-94

and

189-94

merely

con-

tinue to use

the motif of

the

preceding appen-

dix

to shift the

key up by thirds;

in

mm. 106-

26 the second theme is not so much developed

as

restated with a

modulatory

change

at

the

end

(thus,

one

might

speak

of a

development

only

after m.

117)

and with

its

charactertrans-

formed from the

original

sotto voce

pianissimo

to the

chordally

reinforced

ortissimo;

and

mm.

250-64 do not so much

develop

as

make

refer-

ences to

previously

heard ideas. Even

mm.

95-

106

and

195-206,

which

are as close to

genuine

development as the Ballade ever gets, begin

with restatements of

the main

theme and

only

later

lapse

into a brief and

rudimentary

the-

matic

working.

But in these two

passages,

at

least,

one

cannot

really

speak

of

a

thematic

restatement

(as

in

mm.

106-26),

since

too little

of the

original