The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics ... · Susan Buck-Morss 101...

Transcript of The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics ... · Susan Buck-Morss 101...

The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of LoiteringAuthor(s): Susan Buck-MorssSource: New German Critique, No. 39, Second Special Issue on Walter Benjamin (Autumn,1986), pp. 99-140Published by: New German CritiqueStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/488122 .

Accessed: 29/12/2014 11:31

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

New German Critique and Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve andextend access to New German Critique.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore: The Politics of Loitering

by Susan Buck-Morss

I

A Note on Method

... already today, as the contemporary mode of knowledge- production demonstrates, the book is an obsolete mediation be- tween two different card-filing systems. For everything essential is found in the note boxes ofthe researcher who writes it, and the reader who studies it assimilates it into his own notefile. Walter Benjamin, Einbahnstrasse, 1928.

In the Passagen- Werk, Benjamin has left us his note boxes. That is, he has left us "everything essential." Lamentations over the work's in- completeness are thus irrelevant. Had he lived, the notes would not have become superfluous by entering into a closed and finished text. And surely, the card file would have been thicker. The Passagen-Werk is as it would have been: a historical lexicon of the capitalist origins of modernity, a collection of concrete, factual images of urban experience. Benjamin handled these facts as if they were politically charged, capable of transmitting revolutionary energy across generations. His method was to create from them, through the formal principle of montage, constructions of print which had the power to awaken political con- sciousness among present-day readers. The Baudelaire essays (1938, 1939) were two such constructions. Had Benjamin lived, the Passagen- Werk notes would have been the source of others.

The Passagen-Werk, as the 1935 expose indicates, was to be a com- mentary on both "texts" and "reality." Benjamin recognized the dif- ference. In the former case, he tells us, "philology is the fundamental science"; in the latter it is "theology" (V,' 574). Crucially important to a

1. The Passagen-Werk is vol. V of Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schr7ften, eds. Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhaiuser (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1972 -), cited here by volume number.

99

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

100 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

theological reading was what Benjamin described as "telescoping the past through the present" (V, 588). It means that the elements of the 19th century which he chose to record reflected the concerns of his own era. These connections are most often not spelled out in the Passagen-Werk. Still, we can, and indeed must assume their existence. Benjamin wrote explicitly: "The events surrounding the historian and in which he takes part will underlie his presentation like a text written in invisible ink" (V, 595). And he made it clear that he chose the Paris arcades as the central image precisely because these early forms of industrial luxury were in decay in his own time. We may be sure that his research in 19th-century world expositions was sparked by the Paris Expositions of 1931 and 1937; the early, utopian renewal schemes which he noted made a critical constellation with Le Corbusier's 1925 Voisin Plan to make a high-rise development out of central Paris: Grandville's animated drawings of nature took on particular signifi- cance in the 1930s given the success in Paris of Walt Disney's first animated feature films. In the 1850s the bourgeois state first articu- lated an ideology of capitalists and workers united in a common purpose - the Urform of the Popular Front line which sold out radical working- class politics in 1936. The Passagen-Werk's focus on Napoleon III (the first bourgeois dictator) was in response to the rise of Hitler, just as its concern with Baron von Haussmann's public architecture provided the prototype for the state-glorifying projects of Albert Speer. As a his- torian Benjamin valued textual exactness not in order to achieve a hermeneutical understanding of the past "as it actually was" - he called historicism the greatest narcotic of the time - but for the shock of historical citations ripped out of their original context with a "strong, seemingly brutal grasp" (V, 592), and brought into the most immediate present. This method created "dialectical images" in which the old- fashioned, undesirable, suddenly appeared current, or the new, de- sired, appeared as a repetition of the same.

"One should never trust what an author himself says about his work," wrote Benjamin (V, 1046). Nor should we, because if Benjamin is correct, the truth-content of a literary work is released only after the fact, and is a function of what happens in that reality which becomes the medium for its survival. It follows that in interpreting the Passagen- Werk, our attitude should not be reverence for Benjamin's work that would immortalize it as the product of a great author no longer here, but reverence for the very mortal and precarious reality that forms our own "present," through which Benjamin's work is now telescoped.

Today the Paris arcades are being restored like antiques to their former grandeur; the bicentennial celebration of the French Revolution has at least threatened to take the form of another great world exposition; Le

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 101

Corbusier-inspired urban renewal projects, now in decay, have be- come the desolate setting for a film like Clockwork Orange; Walt Disney Enterprises are constructing technological utopias in the tradition of Fourier and St.-Simon. When trying to reconstruct what the arcades, expositions, urbanism, and technological dreams were for Benjamin, we cannot close our eyes to what they have become for us. It follows that a philological reading of the Passagen-Werk, although necessary, is not enough and that sometimes, in the service of truth, Benjamin's own words must be ripped out of context with a "seemingly brutal grasp."

The responsibility for a "theological" reading of the Passagen-Werk (one which concerns itself not only with the text, but also with changing present reality which has become the index of the text's legibility) can- not be brushed aside. This means simply that politics cannot be brushed aside. The following comments on the figure of the flaneur are programmatic of a method of interpreting the Passagen-Werk that tries to acknowledge this political responsibility.

II

The Extinction of a Social Species/Urforms of the Present

1st dialectical step: the arcades grow from a lustrousplace into a delapidated one (V, 1213). The historical index of[dialectical] images says not only that they belong to a particular time; it says above all that only in a par- ticular time do they come "to legibility"

(V, 577).

As Ur-forms of contemporary life, Benjamin avoided more obvious social types and went to the margins. He singled out the flaneur, pros- titute, collector - historical figures whose existence was precarious economically in their own time (although their numbers flourished in early industrialism),2 and socially across time because the dynamics of industrialism ultimately threatened these social types with extinction,

2. The collector came into his own later. Benjamin connects him with the decline of the arcades when, as flaneur and prostitute disappeared from them, the collector expanded his terrain and assembled there the out-of-date products of the earlier period (V, 272). Ultimately, this figure, too, was threatened by industrialism: "I do know that time is running out for the type that I am discussing here [. . .]. But, as Hegel put it, only when it is dark does the owl of Minerva begin its flight. Only in extinction is the collector comprehended" (Walter Benjamin, "Unpacking my Library," Illumina- tions, trans. Harry Zohn [New York: Schocken Books, 1969]), p. 67. (Hereafter Ill.)

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

102 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

as it threatened the arcades, the environment which had originally been so attractive to their trades.

For the flaneur, it was traffic that did him in. In the relatively tranquil shelter of the arcades, his original habitat, he practiced his trade of not trading, viewing as he loitered the varied selection of luxury-goods and luxury-people displayed before him. "Around 1840 it was elegant to take turtles for a walk in the arcades. (This gives a conception of the tempo of flanerie)" (V, 532). By Benjamin's time, taking turtles for urban strolls had become enormously dangerous for turtles, and only somewhat less so for flaneurs. The speed-up principles of mass pro- duction had spilled over into the streets, waging "war on flaneurie" (V, 547). The "flow of humanity ... has lost its gentleness and tranquili- ty," Le Temps reported in 1936: "Now it is a torrent, where you are tossed, jostled, thrown back, carried to right and left" (V, 564). With motor transportation still at an elementary stage of evolution, one already risked being lost in the sea.

Today, it is clear to any pedestrian in Paris that within public space, automobiles are the dominant and predatory species. They penetrate the city's aura so routinely that it disintegrates faster than it can coalesce. Flaneurs, like tigers or pre-industrial tribes, are cordoned off on reserva- tions, preserved within the artificially created environments of pedes- trian streets, parks, and underground passageways. In Victor Hugo's old age, viewing the city from the roof of a public omnibus still preserved (for men)3 some of the panoramic pleasure of parapatetic flanerie (V, 545, 554-5), if not the freedom "to follow one's inspiration as if the mere turning right or left already constituted an essentially poetic act" (V, 547). Today the very efficient metro system extinguishes the view (except for a glimpse of the Seine at Bir Hakeim or the tree-lined Boulevard at Glaciere), and places diminish to dots and colors on a map, or block letters on the station walls.4 In the metro there is no verg- ing off course, no time for the flaneur's "irresolution" (V, 536). The old, buff-colored metro cars still allow air to penetrate; the new ones, blue and black, are sealed as tight as space-capsules. In them, pressed during rush hour up against the next person like so many sandwiches, with nothing but solopsism and indifference for defense,5 the would-

3. Women were forbidden on the roofs (V, 544). 4. Benjamin comments on the "fate of street names in the vaults of the metro"

(V, 1008). 5. Benjamin noted the observation of Georg Simmel that the crowding of urban

life would be "unbearable" without psychological distance, and that the money- nature of social relationships functioned as "an inner protection against the all-too- pressing proximity" (V, 561).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 103

be flaneurs face fellow-travellers and replicated wall advertisements while fighting offboredom, or panic (the two are close). But when dark- ness turns the trafficjam into a garland of lights and exhaust fumes are overpowered by sidewalk smells of food and drink, the crowd in its leisure hours still enters into the nighttime panorama of the boule- vards6 in order to reenact en masse, as an atavistic practice, the combina- tion of distracted observation and dream-like reverie that is charac- teristic of the flaneur.

The present uninhabitability of Paris streets is a recurrence of the past. "Until 1870 carriages dominated the streets"; it was because of this that "flanerie first took place principally in the arcades ..." (V, 85). Under Napoleon III the elements of modernity moved out of the womb of the arcades and settled onto the new boulevards built by Haussmann. The construction of wide sidewalks first made strolling on the boulevards possible, hastening the decline of the arcades,7 and corresponding to a change in the function of flanerie. Benjamin made a cryptic note: "Dialectic offlanerie: The interior as street (luxury)/the street as interior (misery)" (V, 1215). The arcades, interior streets lined with luxury shops and open through iron and glass roofs to the stars, were a wish-image, expressing the bourgeois individual's desire to escape through the symbolic medium of objects from the isolation of his/her subjectivity. On the boulevards, the flaneur, now jostled by crowds and in full view of the urban poverty which inhabited public streets, could maintain a rhapsodic view of modern existence only with the aid of illusion, which is just what the literature of flanerie - physiognomies, novels of the crowd - was produced to provide. If at the beginning, the flaneur as private subject dreamed himself out into the world, at the end, flanerie was an ideological attempt to reprivatize social space, and to give assurance that the individual's passive obser- vation was adequate for knowledge of social reality. In Benjamin's time, even this ideological form of flanerie was at the brink of decline: The flaneur had become a "suspicious" character.'

The flowering of flanerie was brief, corresponding to the first bloom- ing of the arcades. This era of origins is irretrievable. Benjamin's con- cern was not nostalgia for the past, but the critical knowledge necessary for a revolutionary break from history's most recent configuration. He

6. The "flaneur of the night" was encouraged as early as 1866 by stores open until 10:00 p.m. (V, 540).

7. Other causes were electric lighting, the banishing of prostitution, and the new culture of free air, which found the old passageways stifling (V, 1028).

8. Walter Benjamin, "Die Wiederkehr des Flaneurs" (review of Franz Hessel, Spazieren im Berlin, 1929), III, p. 198.

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

104 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

claimed the past was illuminated only when lit by the present (V, 573), and the converse was equally true: "Every present is determined by those [past] images which are synchronic with it" (V, 57 8). Such images are "dialectical," in one sense of the term, when they are negated and preserved in history at once. In our own time, in the case of the flaneur, it is not his perceptive attitude which has been lost, but rather its marginality. If the flaneur has disappeared as a specific figure, it is because the perceptive attitude which he embodied saturates modern existence, specifically, the society of mass consumption (and is the source of its illusions). The same can be argued for all of Benjamin's historical figures. In commodity society all of us are prostitutes, selling ourselves to strangers; all of us are collectors of things.

"The dialectical image... is the Urphiinomen of history" (V, 592). Benjamin's images are truth-as-image, presented "naked before eyes of the attentive observer"9 - archetypes in Goethe's sense, but with a historical index.0 The arcades are such an archetype, a concrete man- ifestation of economic facts which

in their own self-development - unfolding a better word - let emerge from themselves the series of con- crete historical forms of the arcades, just as the leaf unfolds from itself the entire abundance of the empiri- cal plant world (V, 577).

In connection with these historical forms, the figure of the flaneur "who goes botanizing on the asphalt"" is crucial. It provides philo- sophical insight into the nature of modern subjectivity - that to which Heidegger referred abstractly as the "throwness" of the subject - by placing it within specific historical existence.'" In the flaneur, concrete-

9. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, cited in Georg Simmel, Goethe (Leipzig: Verlag von Klinkhardt and Biermann, 1913), p. 57. Benjamin refers to this book (and this page) when commenting on the affinity between his concept of truth and that of Goethe. (V, 577).

10. The Passagen-Werk documents the source (Ursprung) of contemporary mass society, and understands the causal connection in terms of the Goethean concept of Urphiinomen: "Ursprung - that is the concept of the Urphiinomen brought out of the pagan connection with nature and into the Judaic connection with history.. ." (V, 577). Theology, like the flaneur also threatened by modernity with extinction, might well be described as the dialectical Urform of Benjamin's method, negated and preserved at once: "My thinking is connected to theology like the ink-blotter to ink. It is totally saturated with it. But if it were up to the blotter, nothing that has been written would remain" (V, 588).

11. Walter Benjamin, "The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire," Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, trans. Harry Zohn (London: NLB, 1973), p. 36. (Hereafter CB).

12. "What separates the [dialectical] images from phenomenology's 'essences' is

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 105

ly, we recognize our own consumerist mode of being-in-the-world. Benjamin wrote: "the department store is [the flaneur's] last haunt"

(V, 562). But flanerie as aform of perception is preserved in the charac- teristic fungibility of people and things in mass society, and in the merely imaginary gratification provided by advertising, illustrated journals, fashion and sex magazines, all of which go by the flaneur's principle of "look, but don't touch" (cf. V, 968). Benjamin examined the early connection between the perceptive style offlanerie and that of journalism. If mass newspapers demanded an urban readership (and still do), more current forms of mass media loosen the flaneur's essen- tial connection to the city. It was Adorno who pointed to the station- switching behavior of the radio listener as a kind of aural flanerie. is In our time, television provides it in an optical, non-ambulatory form. In the United States particularly the format of television news-programs approaches the distracted, impressionistic, physiognomic viewing of the flaneur, as the sights purveyed take one around the world. And in connection with world travel, the mass tourist industry now sells flanerie in two and four week packets.'4

The flaneur thus becomes extinct only by exploding into a myriad of forms, the phenomenological characteristics of which, no matter how new they may appear, continue to bear his traces, as Urform. This is the "truth" of the flaneur, more visible in his afterlife than in his flour- ishing.

III

2nd dialectical step: [. . .] Not-yet-conscious knowledge ofpast existence. Knowledge of that which has been as a making-self-conscious which has the structure of awakening (V, 1213). A central problem of historical materialism that finally should be seen: ... in what way is it possible to connect a heightened graphicness to the execution of the Marxist method? The first stage . .. will be to take over into history the principle of montage (V, 5 75).

Benjamin's distinction between Erfahrung and Erlebnis paralleled that between production, the active creation of one's reality, and a

their historical index. (Heidegger searches in vain to save history for phenomenology abstractly, through 'historicity')" (V, 578).

13. Theodor W. Adorno, "Radio Physiognomik" (1939), Frankfurt-am-Main, Adorno Estate, p. 46.

14. Discussed in Susan Buck-Morss, A Tourguide to Modern Experience, unpublished.

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

106 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

~?i~~-~ip~

I

~n .S

~s~~

s;- "i K~

:

e- -a

i,

~1~7 :I ??1

~,~i~ ~ s~ir?

ii?~ c i? -ki ~" " :;B ~;:??i?-~~-~~~";~

a?:~i

~-~-?i ..?c.,--:-p,;~~6n~ a

~-?MI- .i6:ii?-d-,;i.n ~~in-i~~

'~~~il~s~~ ~-~ ~-~~ ~~ ii~i~ ~au \'S;I1~~~~S~bf-~~

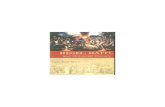

L'homme-Sandwich (miroir du monde, nr. 316, 21 March 1936, p. 45)

reactive (consumerist) response to it: "Erfahrung is the product ofwork; Erlebnis is the phantasmagoria of the idler" (V, 962). To the idler who strolls the streets, things appear divorced from the history of their pro- duction, and their fortuitous juxtaposition suggests mysterious and mystical connections. Time becomes " 'a dream-web where the most ancient occurrences are attached to those of today' " (V, 546). Mean- ings are read on the surface of things: "The phantasmagoia of the flaneur: reading profession, origins and character from faces" (V, 540).

"... [T]he idler, the flaneur, who no longer understands anything of production, wants to become an expert of the market (of prices)" (V, 473). Now, if Marx's economics is correct, this expert of the market will never understand anything of value. Yet Benjamin made a strategic choice in the Passagen-Werk to focus on consumption rather than pro- duction, and this in a work in which, to quote Adorno, "every sentence

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 107

is and must be loaded with political dynamite."'5 If the Passagen-Werk was to have been more than a critique of false consciousness, just what is Benjamin doing in the phantasmagoria of the marketplace, the commodity-filled dreamworld of the flaneur/consumer? Benjamin writes: In the face of the "wind of history" (V, 592) for the dialectician, "thinking means setting sails. How they are set is the important thing" (V, 57 1). "What for others are digressions are for me the data that deter- mine my course" (V, 570). But this course is precarious. To cut the lines that have traditionally anchored Marxist discourse in production and sail off into the dreamy waters of consumption is to risk, politically, running aground. Does the Passagen-Werk project avoid this risk? The question is asked not in the name of Marxist orthodoxy, but rather, in the critical spirit of Adorno, who grew alarmed by the apparent affir- mation of mass consciousness and lack of class differentiation in Ben- jamin's theory. To test the waters, consider the following assertion typical of Benjamin's commentary in the Passagen-Werk: "[The flaneur] takes the concept of being-for-sale itself for a walk. Just as the depart- ment store is his last haunt, so his last incarnation is as sandwichman" (V, 562).

Why the sandwichman? In a Charles Dickens novel there appears "an animated sandwich composed of a boy between two boards,"16 but the fact that this figure had its own history in the 19th century is a class marker ignored by Benjamin. Tracing class history, it appears, is not the kind of knowledge he is after. Nor does it interest him that sandwiches also have a social history. The first "sandwich" (inanimate, composed of cold beef between two bread slices) was invented as a mode of repast in the 1760s byJohn Montague, Earl of Sandwich, in order to save himself the need of leaving the gaming table (OED). This class marker, coincidentally, intersects again with Benjamin's course. For if sandwich-eating became a bourgeois fashion in the 19th century (entering Parisian discourse in 180317 and undergoing the prolifera- tion of forms typical of capitalist production),18 then so did gambling, and the 19th-century gambler is a major figure in the Passagen-Werk. But, again, what intrigues Benjamin is not the social history of gambling as a pastime among ruling classes despite changes in the mode of produc-

15. Letter, Adorno to Benjamin, 6 November 1934 (V, 1106). 16. Oxford English Dictionary (hereafter OED). 17. Petit Robert (hereafter PR). When did the sandwich become the traditional

lunch of the worker? Did it make it possible for him to remain at his work station, like Lord Montague at his gaming table?

18. A Glasgow confectioner, 1866, made 100 different varieties of sandwiches (OED).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

108 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

tion, but the particular historical form of gambling within industrial capitalism which is prototypical of the way time passes: Ifflanerie is the lived experience of the "phantasmagoria of space," then gambling is that of the "phantasmagoria of time" (V, 1212).

The historically specific nature of the gamblers' gestures is that they "show us how the mechanism to which the players in a game of chance entrust themselves possesses them body and soul, so that even in their private spheres and no matter how passionately moved they may be, they can no longer function in any way but reflexively" (CB 135, trans. altered). Benjamin connects this behavior not only to the harried city- dweller or the flaneur jostled by the crowd, but to the industrial worker's gesture at the machine. Of course the capitalist who gives himself over to fate at the gaming table is replicating in his leisure his activity of gambling on the stock market during the "work" day, but this parallel is for Benjamin less revealing than the characteristic "futility, the emptiness, the inability to complete something" (CB 134) which connects the gambler and the machine laborer: "Gambling in fact contains the modern worker's gesture .... The jolt in the move- ment of a machine is like the so-called coup in a game of chance" (CB 134).

The relation of the industrial worker to the thing-world of production, Benjamin is arguing, is not different from the relation of consumers to the thing-world of consumption: Neither is social experience (Erfahrung) of a type that could lead to knowledge of the reality behind appearances (cf. V, 472). Is he suggesting a description of consciousness in which class distinctions are irrelevant? Yes, and no. Yes, because if worker's productive activity does not lead to knowledge, then critical theory cannot privilege the cognitive experience of the proletarian class. No, because when the same words are used to describe the most remote social phenomena (the bourgeoisie, leisure-time, gambling/ the pro- letariat, work-time, machines), dialectical images are created out of language itself. For Benjamin, "language is the place where one meets dialectical images" (V, 577), and this in two ways: the same concept can describe two socially remote realities; or, the same reality can be de- scribed by the most antithetical linguistic terms. With the aid of the mimetic skill of correspondences, Benjamin places concepts strate- gically, off-angle against referential contents, rather than letting them hover over them like luffing sails. (Note that for Benjamin, against structuralists and post-structuralists, the dialectic power of language exists only if the things as referents are not bracketed out). The result is a tension between words and the things they represent which, far from blurring distinctions, functions to sharpen perceptions intensely. For the dialectician "words are sails. How they are set, that secures them as

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 109

concepts" (V, 591). Once they are set, it is not within language, but within the space between language and reality that the cognitive proc- ess is compelled forward.

But in which direction? Toward a theory of modern perception in which producer and consumer are alike afflicted by an illusory, false consciousness, a collective unconscious in which reality takes on the distorted form of a dream. If the goal is revolutionary cognition, will this tack possibly lead us to it? Is it enough for our critical autonomy that, rather than being carried along by the historical drift of consumer society, we, situated within it, fight upwind? More, on the course of loitering, will there be any wind to move us?

Benjamin was counting on the explosive force of dialectical images to jolt people out of their dreaming state. Revolutionary cognition occurred not at the point of production, but at the moment of "awaken- ing." Perceived images were dream-symbols which needed interpreta- tion, and this required a historical knowledge or origins. Benjamin described the "pedagogic" side of his work: " 'to educate the image- creating medium within us to see dimensionally, stereoscopically, into the depths of the historical shade' " (V, 571). Now, a stereoscope, that instrument which creates a three-dimensional image, works from not one image, but two. On their own, the historical facts in the Passagen- Werk are flat, situated, as Adorno complained, "on the crossroads of magic and positivism."9 It is because they are, and were meant to be, only half the text. The reader of Benjamin's generation was to provide the other half from the fleeting images that appeared, isolated from history, in his or her lived experience. The spatial, surface montage of present perception which makes all of us flaneurs can be transformed from illusion to knowledge once the "principle of montage" is re- functioned temporally, that is, once the axis of montage is turned "into history"; it makes it possible "to grasp the design of history as such. In the structure of commentary" (V, 575).

Let us return to get our bearings to Benjamin's comment "The sandwichman is the last incarnation of the flaneur" (V, 565), and take a different tack. The double exposure of past and present is presented here as a riddle, in which knowledge of the past doesn't historicize present truth, but crystallizes it. The unravelling of this riddle would place Benjamin's readers within an image-sphere where revolutionary "awak- ening" was possible, as I hope to demonstrate.

The sandwichman was a denigrated, yet familiar figure in Paris in the 1930s, one which would have entered the perceptive range of most

19. Letter, Adorno to Benjamin, 10 November 1938, in I, p. 1096.

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

110 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

city-dwellers. Human billboards, they advertised and publicized the products and events (cinemas, store sales) of bouregois consumer cul- ture. Yet they themselves, despite the uniforms they were loaned to give a respectable appearance, were associated closely with poverty: "You have seen them passing on our streets, emaciated and shabby in their long grey coats and under their caps with polished visors. Let us speak in all frankness: I am scarcely a partisan of their job. Typically, neither the dignity of publicity nor that of man ends up increased by these pitiful processions."20 The sandwichmen, casual laborers, part- time and non-unionized, were recruited from the ranks of the clochards, 12,000 of whom were registered in Paris in the mid-1930s as sans domicilefixe.2' They slept where they could, beneath the Seine bridges, and one would suppose, in the shelter of the decaying arcades (as they already had in the era of their origins22). Marginal people, proletarian declasses, these were "the whole population of the ragged, the tattered, and the hungry which society had cast out" (Brassaii 32). During the Depression years of the 1930s, to be sure, society's cast-outs were mul- titude. What could be more removed than this "last incarnation" from the original flaneur of a hundred years earlier who, with his dandy-like appearance, developed a reactionary life-style that looked back to an era when leisure was a way of life, and a sign of class dominance?

What indeed? For the flaneur, and for the urban writers who styled themselves after him, such characters - vagabonds, ragpickers, cab- drivers - were merely part of the urban landscape, and hardly the most attractive one (CB 21-22). But even when an author expressed sympathy for the new urban destitute, it was of a sort peculiar to modem perception. It evoked emotion without providing the knowledge that could change the situation. Benjamin mentions Balzac who, passing a man in tatters, "touched his own sleeve and came to feel there a rent through which gaped the poor man's elbow" (V, 561). Such empathic identity (Einfihlung) was as characteristic of the commodity world as it was inadequate. The momentary feeling of horror or sympathy for a stranger was related to that "love at last sight" which infected the erotic life of the city-dweller (CB 125). Einfiihlung could be evoked by things as

20 Miroir du monde, 22 March 1936, p. 45. 21. Brassdii, The Secret Paris of the 30's, trans. Richard Miller (London: Thames and

Hudson, 1977), pp. 32-33. See also "Clochards" Dictionnaire de Paris (Larousse, 1964), pp. 135-36.

22. "And those who cannot pay... for a night's lodging? Well, they sleep where they find a place, in passages, in arcades, in any possible corner where the police or the owners allow them to sleep undisturbed" (Friedrich Engels, Die Lage der Arbeitenden Klasse in England [1844] cited in V, 94).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 111

well as people.23 As a form of solidarity, it was a purely mental event, and dissipated quickly from consciousness. The flaneur records the merely apparent reality of the market place behind which the social relations of class remained concealed. The empathic relationships he establishes in their place make not only human misery, but "the [class] struggle against misery into an object of consumption."24

There was no way the mimetic gesture of Einfiuhlung could close the gap between classes, no way that the flaneur and the clochard could become one under its sign - which might be read as an expression of the desire for a common humanity, but not its realization. It should be clear that what was at stake for Benjamin was a very present concern, the problem of the politically committed, bourgeois writer and intel- lectual of his own time. The humanism which led "men of letters" to support the Popular Front against fascism, or to join the international movement for disarmament, was one of which Benjamin as a Marxist was suspicious. In "The Author as Producer" (1934) Benjamin gave didactic answers. On the world peace movement, he quoted Trotsky: "When enlightened pacifists undertake to abolish War by means of rationalist arguments, they are simply ridiculous. When the armed masses start to take up the arguments of Reason against War, however, this signifies the end of war" (UB 92). On the intellectuals' solidarity with the proletariat, he insisted: "political commitment, however revo- lutionary it may seem, functions in a counter-revolutionary way so long as the writer experiences his solidarity with the proletariat only in the mind and not as a producer" (UB 91). Precisely this second lesson is the point of the historical montage of flaneur and sandwichman.

The task of the man of letters is to understand clearly his objective position in the productive process, and for this the historical figure of the flaneur proves invaluable. The flaneur is not the aristocrat: not leisure (Musse) but loitering (Miissiggang) is his trade. In order to survive under capitalism he writes about what he sees, and sells the product. To put it plainly: The flaneur in capitalist society is a fictional type; in fact, he is a type who writes fiction. Flanerie promoted a style of social observation which permeated 19th-century writing, much of which was produced for the feuilleton section of the new mass newspapers. The flaneur-as-writer was thus the prototype of the author-as-producer

23. Projection onto miserable persons, commodities on display, stars on the screen, women passing by, made them fantasy figures within one's own experience (Erlebnis), while they themselves remained mute (V, 528). See section (v) below.

24. Walter Benjamin, "The Author as Producer," Understanding Brecht, trans. Anna Bostock (London: NLB, 1973), p. 96. (Hereafter UB.)

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

112 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

of mass culture. Rather than reflecting the true conditions of urban life, he diverted readers from its tedium (I, 1193).25

Observed by his public while he "works" at loitering (V, 559-60), the flaneur-as-writer may have social prominence, but not dominance. His protests against the social order are never more than gestures because (not surprisingly under capitalism) he needs money. The pro- totype of the rebellious flaneur is the boheme,26 who like Baudelaire, has "political insights [that] do not go fundamentally beyond that of the professional conspirator" (CB 13). His objective situation connects him with the clochard, and in fact the bravado of their politics of loiter- ing, its anarchism and individualism, is the same. " 'Society didn't want anything to do with me,' he said philosophically, 'and I didn't want anything to do with it. I made my choice.., .and I've got my independence.' " These lines could have been spoken by an advocate ofl'art pour l'art in 1860 just as well as by their actual speaker, a Paris clochard in the 1930s (cited in Brassiii, 30).27 In both cases there is self- deception.28 The 19th-century writer "goes to the marketplace as flaneur, supposedly to take a look at it, but in reality to find a buyer" (CB 34). There, in the stereoscopic depth of history, he is brought face to face with the 20th-century clochard, supposedly scornful of society, but in reality a sandwichman who advertises its coming attractions.

IV

What do we know of the streetcorners, curbstones, the architec- ture of the pavements, we who have never felt the streets, heat, dirt and edges of the stones under naked soles... ? (1V 1018).

But if the political lesson for bourgeois intellectual and unemployed proletariat is the same, their social reality is not. Capitalism has two

25. Among his modern forms: the reporter, a flaneur-become-detective, covers his beat (V, 554); the photo-journalist hangs about like a hunter ready to shoot (V, 964).

26. Cf. an 1843 description: "I mean by bohemians that class of individuals whose existence is problematic.., .of which the majority awake in the morning without knowing where they will eat at night; wealthy today, starving tomorrow; prepared to live honestly if they are able, and otherwise if they are not" (cited in V, 539).

27. Cf.: "A ragpicker cannot, of course, be part of the bohime. But... everyone who belonged to the boheme could recognize a bit of himself in the ragpicker. Each person was in a more or less obscure revolt against society and faced a more or less pre- carious future" (CB, p. 20).

28. Benjamin praised Baudelaire for seeing through that deception: "I who sell my thought and want to be an 'author' " (CB, p. 34).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 113

ways of dealing with leisure, stigmatizing it within an ideology of unemployment, or taking it up into itself to make it profitable. The dividing line cuts between prosperity and suffering, and it makes a great deal of difference on which side one fails.

The flaneur is the prototype of a new form of salaried employee who produces news/literature/advertisements for the purpose of informa- tion/entertainment/persuasion (the forms of both product and pur- pose are not clearly distinguished). These products fill the "empty" hours which time-off from work has become in the modern city. Writers, now dependent on the market, scan the street scene for material, keeping themselves in the public eye and wearing their own identity like a sandwich board. They live in a certain district, frequent a certain cafe, and the fame of both person and place goes up. Benjamin notes that such a writer acts as if he knew Marx's definition that "the value of every commodity is determined ... by the socially necessary labor time of its production .... In his eyes and frequently also those of his employer, this value [for his labor time] receives some fantastic compensation. Clearly the latter would not be the case if he were not in the priviledge position of making the time for the production of his use value observable for public evaluation, in that he spends it on the boulevards and thus at the same time displays it" (V, 559-60). Bour- geois writers need a mass audience and depend for employment on those capitalist pleasure-industries which holds that audience captive. Financially, many have done well, and in certain cases (beginning with Hugo, Sue, La Fontaine) they achieved political power as well. Even those who like Baudelaire have been self-conscious secessionists from society are caught in the unresolved tension within bourgeois society between the "outsider" and the "star."29 The inter-war "lost" genera- tion which was Benjamin's own (although he was not yet then a star) found each other on the Paris streets, observed as well as observer - Breton's circle at the Caf6 Cert,, and Sartre's at the Deux Magots. Artists and writers had become a part of the Parisian landscape, as significant a component of the "phantasmagoria" of the city as the clochards.

But in the latter, antithetical case, capitalism, rather than paying the idler-on-the-street royally, turns its reserve army of the unemployed out onto the street and then blames them for being there. The clochards of Paris are still with us. Capitalism replenishes their number, if not

29. Benjamin noted in a count of clippings from newspapers made in 1911, "the names of Baudelaire and Victor Hugo could be found as often as Napoleon" (V, 372).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

114 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

drastically via Depressions, then gradually via automation.30 Their numbers rise and fall with the economic weather vane, but whichever way the wind blows, these twenty-four-hour loiterers don't disappear. They are a (frequently romanticized) Paris institution, achieving an almost mythic status. And yet to attribute their permanence (- some are reputed to have metro stops as mailing addresses -) to some archetypal weakness (or strength) of character would be to fail to see the permanence of the social order which needs to create a myth about them in order to conceal the reason why, in an affluent and "free" society, such poverty exists. "As long as there is still one beggar," wrote Benjamin, "there still exists myth" (V, 505).

Our perception of the clochards illustrates the deceptiveness ofEin- fiihlung. They fascinate us the more their poverty, intoxication, dirt and idleness seem to come from defiance rather than hopelessness. It is their spitting in the eye of bourgeois decorum and their total disregard for its success values to which we, observing from the safe side, feel drawn. Yet to contemplate falling into their vulnerable state evokes a shudder, a fact which the authorities may count on, allowing these street-dwellers as a presence that constrains the rest of us. Included among "us" must be Benjamin, who never denied his bourgeois class background.

He wrote of his youth: "I never slept on the street in Berlin.... Only those for whom poverty and vice turn the city into a landscape in which they stray from dark till sunrise know it in a way denied to me.""31 Poverty and vice. Laboring classes and dangerous classes. To whom do the streets "belong"? In the early notes for the Passagen- Werk (1927-29) Benjamin began a formulation: "Streets are the dwelling place of the collective. The collective is an eternally restless, eternally moving essence that, among the facades of buildings, endures (erlebt), experi- ences (erflhrt), learns and senses as much as individuals in the protec- tion of their four walls. For this collective the shiny enamelled store signs are as good and even better a wall decoration as a salon oil- painting is for the bourgeoisie. Walls with the "defense d'afficher" are its writing desk, newspapers are its libraries, letterboxes its bronzes, benches its bedroom furniture - and cafe terraces the balcony from which it looks down on its domestic concerns after work is done" (V, 994 again, 533, 1051). The same passage appears in Benjamin's 1929 review of Franz Hessel's book Spazieren in Berlin, except that the subject

30. Cf. Alexandre Vexliard, Introduction a la sociologie du vagabondage (Paris, Marcel Riviere et Cie, 1936), pp. 90-91.

31. Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (London: NLB, 1979), p. 330. (Hereafter OWS.)

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 115

(which still seems to have Benjamin's approval) is not the Kollektiv, but "the masses [die Masse] - and the flaneur lives with them..." (III, 198).

In the 1938 essay on Baudelaire, the idea undergoes a significant change. In place of the collective, the flaneur alone takes possession of the streets. He no longer sleeps on its benches; and the walls are now "the desks against which he presses his notebooks" (CB 37). The passage has a new conclusion: "That life in all its variety and inexhaust- ible wealth of variations can thrive only among the grey cobblestones and against the grey background of despotism was the political secret on which the physiologies [written by the flaneurs] were based" (CB 37). The tone of the revision (- the flaneur writes "against the grey background of despotisms" -) is clearly critical, and the reason for the change is fascism. In a late (post- 1937) entry to the Passagen- Werk Ben- jamin mentions as the "true salaried flaneur" and "sandwichman" Henri Beraud (V, 967), proto-fascist journalist for Gringoire, whose nationalist and anti-Semitic attack on Leon Blum's Minister of the Interior led the latter to suicide. (Benjamin notr i that intimations of such politics could already be found in Baudelaire, whose diary con- tained the "joke": "A fine conspiracy could be organized for the pur- pose of exterminating theJewish race" [CB 14]). Like a street-hawker, the financially successful Beraud peddled the fascist line which camou- flaged class antagonisms by replacing them with the pseudo-issue of race. The vertical division between classes was thereby displaced onto a horizontal one between nationals and outsiders, allowing the attack on the Left to be concealed under the jargon of patriotism.

A salaried flaneur profits by following the ideological fashion. Ben- jamin connects him ultimately to the police informer and in a late note makes the association: "Flaneur - sandwichman - journalist-in- uniform. The latter advertises the state, no longer the commodity" (I, 117-9). In an economically precarious and ideologically extremist climate like the 1930s the penalty for a writer's refusal to toe the politi- cal line could be great. After 1933, Benjamin's anxieties over money were constant; after 1939, his fear was for personal safety. For this independent Leftist and exiled German-Jew, Paris did not provide a lasting refuge. He wrote in what is surely a late entry: "The proletariat has a very specific experience of a metropolis. The emigrant has in it a similar one" (V, 437).

It is impossible to pin down the Passagen-Werk fragments with chrono- logical precision and thus to argue, for example, that Benjamin no longer spoke of the collective positively after 1933.32 But even if he did change

32. In fact, at least as late as the 1935 expose Benjamin expressed hope that the

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

116 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

his evaluation of the revolutionary potential of the masses, this may not be the crucial point. It seems to me that throughout the Passagen-Werk Benjamin (entirely consistently) argued both 1) only the proletarian class had potential power as a revolutionary subject; and yet 2) only by awakening the not-yet-conscious collective could that class be ad- dressed. The emphasis here was on awakening (a state the bourgeoisie would never reach).3 The dreaming collective might include both classes. It was simply the "crowd," and it was the source of misleading and illusory perceptions. Two (late) quotations are crucial. On the crowd as the observed: "In fact this [1860] 'collective' is nothing but appearance (Schein). This 'crowd' on which the flaneur feasts his eyes is the mold into which, 70 years later, the 'Volksgemeinschaft' was poured. The flaneur, who prided himself on his cleverness ... was ahead of his contemporaries in this, that he was the first to fall victim to that which has since blinded many millions (V, 436). And as the observer: "The audience of the theater, an army, the inhabitants of a city [form] the masses, which as such do not belong to a particular class. The free market increases these masses rapidly.., .in that every commodity collects around itself the mass of its customers. The totalitarian states have taken this mass as their model. The Volksgemeinschaft attempts to drive everything out of individuals that stands in the way of their com- plete assimilation into a massified clientel. The only unreconciled opponent... in this connection is the revolutionary proletariat. The latter destroys the illusion of the crowd (Schein der Masse) with the reality of the class (Realitiit der Klasse)"(V, 469). Fascism appealed to the collec- tive in its unconscious, dreaming state. It made "historical illusion all the more dazzling by assigning to it nature as a homeland" (V, 595). After 1937 Benjamin noted that Erlebnis had come to mean that surren- der to fate encapsuled in the Hitler Youth slogan: "I am born a Ger- man, and therefore I die" (V, 962). Far from "compensating for the one-sided spirit of the times" (Jung), this reaction was totally per- meated by it (V, 589-590). Benjamin asked the question: "Should it be Einfiihlung in exchange value which first makes people capable of the total Erlebnis [of fascism]?" (V, 963) "To the eye which shuts itself when faced with this experience [of the "inhospitable, blinding age of big-scale industrialism"] there appears an experience of complemen-

"dreaming collective" could be awakened (at the same time that class differences were insisted upon).

33. In an early note: "Did not Marx teach us that the bourgeoisie can never itself come to fully enlightened consciousness? And if this is true, is one not justified in attaching the idea of the dreaming collective (i.e., the bourgeois collective) onto his thesis?" (V, 1033).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 117

tary nature as its almost spontaneous after-image" (I, 609). Fascism was that after-image. While condemning the contents of modern cul- ture, it found in the dreaming collective created by consumer-capitalism a ready-at-hand receptable for its own political phantasmagoria. The psychic porosity of the unawakened masses absorbed the staged ex- travaganzas of mass meetings as readily as it did mass culture.34 And if the sandwichman was the last, degraded incarnation of the flaneur, he himself underwent a further metamorphosis. Les extremes se touchent. On the historical, conceptual level, the images of flanneur and sandwichman converge. But on the existential, per- ceptual level, as social extremes they remain distinct. (Both axes are

c s::

M ~ejcl~c E 3

~~hJ

~.i::::: r.

;g~

:B"~i"?

~t~c "~~:a~g?:~~ i-

81 e~

~9e~,~

~~1~4~~4~~$~d~ rg-

'BC:

German Street-scene, 1933. Escorted by armed guards, a Jew stripped of his shoes and trousers carries a sandwich board with the 'humorous' legend 'I am aJew but I have no complaints about the Nazis.' (ARCHIV GERSTENBERG)

34. ". . . the flames on the sides of the Nuremberg stadium, the huge overwhelm- ing flags, the marches and speaking choruses, present a spectacle to [today's] modern audiences not unlike those American musicals of the 1920s and 1930s which Hitler himself was so fond of watching each evening" (George Mosse, The Nationalization ofthe Masses [New York: Howard Fertig, 1975]), p. 207.

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

118 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

necessary for knowledge; neither - empirical perception nor histori- cal conception - conflates into the other.) The difference is between feeling totally at home on the streets, and being exposed and vulner- able there because one is totally homeless. The rulers feel public space to be an extension of their own personal one: They belong there because it belongs to them. For the politically oppressed (a term which this century has learned is not limited to class) existence in public space is more likely to be synonymous with state surveillance, public cen- sure, and political constraint.

V

Sie kibnnen sich nicht vertreten, sie miissen vertreten werden - Marx, 18. Brumaire

To inhabit the streets as one's living room, is quite a different thing from needing them as a bedroom, bathroom or kitchen, where the most intimate aspects of one's life are not protected from the view of strangers and ultimately, the police. Benjamin noted from a 1934 book, Images de Paris, this "portrayal of suffering, presumably under the Seine bridg- es .... A bohemian woman sleeps, her head bent forward, her empty purse between her legs. Her blouse is covered with pins which glitter from the sun, and all her household and personal possessions: two brushes, an open knife, a closed bowl, are neatly arranged-... creating almost an intimacy, the shade of an interior around her" (V, 537).

The homeless bohemian is a woman. In the US today her kind are called "bag ladies." They have been consumed by that capitalist society which makes of Woman the prototypical consumer. Their appearance, in rags and carrying their worldly possessions in worn bags (from Bloomingdale's, perhaps) is the grotesquely ironic gesture that they have just returned from a shopping spree.

Some of the early sandwichmen were women (a fact Benjamin does not note), and sexual difference complicates the politics of loitering.35 In 1884 a writer for the London Times reported: "Yesterday... I met... a procession of ... girls... bearing sandwich adver- tisements"; and the following year there appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette: "We have, and not so very long ago, seen women employed as 'sandwiches' " (OED). The step from displaying sandwich-board adver- tisements to the display of one's own body for sale seemed to them a

35. I am indebted to Mary Lydon for material in this section. See her article, "Foucault and Feminism. A Romance of Many Dimensions," Humanities in Society, vol. 5, nos. 3 and 4 (Summer/Fall 1982).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 119

small one. It was the era of the moral reform movement in England, which brought a shift from the regulation of sexuality to its repression. The Gazette spearheaded the campaign. It culminated in a public demonstration of 250,000 in Hyde Park to demand raising the female age of consent from thirteen to sixteen. Josephine Butler exclaimed: "The crowds and the days remind me of revolution days in Paris.""36 A recent historian has argued: "Compared to mid-Victorian moral- reform movements, this new social-purity crusade was more oriented to a male audience, more hostile to working-class culture, and readier to use the instruments of state to enforce a repressive sexual code."37 For women, state "protection" cut two ways, as under its banner in the late nineteenth century an attempt was made to limit their social freedom and curtail their access to public life.

Sexual repressiveness was not lacking in Paris. Benjamin noted: "1893 the coquettes were driven out of the arcades" (V, 270). Like the flaneurs, they had been at home there:38 "In an arcade, women are as in their boudoir" (V, 612). Prostitution was indeed the female version of flanerie. Yet sexual difference makes visible the privileged position of males within public space. I mean this: the flaneur was simply the name of a man who loitered; but all women who loitered risked being seen as whores, as the term "street-walker," or "tramp" applied to women makes clear. "Les grandes horizontales" became a term of reference for prostitutes in the era of Haussmann's boulevards. The popular literature of flanerie may have referred to Paris as a "virgin forest" (V, 551), but no woman found roaming there alone was expected to be one.

The politics of this close connection between the debasement of women sexually and their presence in public space, the fact that it functioned to deny women power, is clear, at least to us. But it is not clear whether Benjamin should be included among "us" on this point. It was not Benjamin's politics to employ feminism as an analytical frame. True, there is a statement in the Baudelaire essay (1938): "The lesbian is the heroine of modernity" - but heroines, like heroes, were ultimately tragic figures, individualistic and unfruitful in their social protest.39 True, he affirms Bachofen's image of a matriarchal utopia,

36. Cited in Judith R. Walkowitz, Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women, Class and the State (Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1980), p. 246.

37. Ibid. 38. One prostitute was nick-named the Passage des Princes. 39. The "spirituality" and "pure love" of the lesbian which "knows no pregnancy

and no family" was connected, like androgeny and male impotence, with barrenness (1, 661; 672); in the absence of collective politics, suicide became "the only heroic act" remaining"in reactionary times" (CB, p. 76). (Itwas the act taken by Claire Demar, and by Benjamin himself.)

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

120 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

but as an expression of nostalgia for the lost mother, not an affirmation of the free woman. True, Benjamin redeems from oblivion the political manifesto of the Saint-Simonian feminist, Claire Demar, and praises it, compared to the "grandiloquent fantasies" of Enfantin, as "unique in its power and passion" (CB 91). The Passagen-Werk gives serious con- sideration generally to her writings. Demar called for radical sexual freedom for women and the absolute termination of patriarchy: "No more motherhood! No law of race. I say: no more motherhood. Once a woman has been freed from men who pay her the price of her body ... she will owe her existence... only to her own creativity.... Then, only then, will man, woman and child all be liberated from the racial law of exploitation of humanity by humanity" (V, 974).

Yet Benjamin does not follow up on his gesture of yielding to a woman's voice. Instead, he cites Baudelaire, who addresses prostitutes in his poems while the women themselves remain mute: "Baudelaire never wrote ... about whores from the whore's viewpoint" writes Ben- jamin, (V, 438), and proceeds to do likewise.

The image of the whore, the most significant female image in the Passagen-Werk, is the embodiment of objectivity, not subjectivity. Not the prostitute but "prostitution" is a keyword; and it is coupled with "gambling" as a manifestation of the alienation of erotic desire (in the man) when it surrenders itself to fate: "for in the bordello and gaming hall it is the same, most sinful delight: to insert fate within desire, and this, not desire itself, is to be condemned" (V, 612-13). For Benjamin, while the figure of the flaneur embodies the transformation of percep- tion characteristic of modern subjectivity, the figure of the whore is the allegory for the transformation of objects, the world of things. As a dialectical image, she is "seller and commodity in one" (CB 171). As commodity, she is connected in the Passagen-Werk with the constella- tion of "exhibition," "fashion," and "advertisement": "The modern advertisement demonstrates ... how much the attraction of woman and commodity can fuse together" (V, 436). As seller she mimics the commodity and takes on its allure: the fact that her sexuality is on sale is itself an attraction. If society traditionally channelled erotic desire through the elaborately regulated and constrained exchange of women as gifts, the great excitement of the whore is that she promises the buyer liberation from all that. Benjamin writes: "Not in vain the relationship of the pimp to his wife, as a 'thing' which he sells on the market aroused intensively the sexual fantasies of the bourgeoisie" (V, 436).

Benjamin wrote: "The love for the prostitute is the apotheosis of Einfiihlung onto the commodity" (V, 475). In the 19th century this is what was new about the "oldest profession." The prostitute's natural

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 121

body resembled the lifeless mannequin used for the display of the latest fashion; the more expensive her outfit, the greater her appeal. Ben- jamin states as a theme: "Attempt to lure sex into the world of things" (V, 1213). What he calls the "natural" desire for procreation was thus diverted: "The sexuality which formerly - socially - was made mobile by the fantasy of the future of productive powers [i.e., having children] is now only made so by the the [fantasy] of the power of capital" (V, 436). To desire the fashionable, purchasable woman-as-thing is to desire exchange-value itself, that is, the very essence of capitalism. Once this occurs, "the commodity . .. celebrates its triumph" (V, 435): Erotic desire, instinctual nature itself, and also those forces of fantasy- life that might imagine a better society, are cathected onto com- modities. Trapped within capitalism, they become its enthusiastic source of support.

If the whore is a commodity and seller in one, so of course, are all wage-laborers under capitalism.40 Marxists habitually exclude pros- titutes from the revolutionary class because their labor is "unproduc- tive," and assign them, disparagingly, to the Lumpenproletariat. Ben- jamin admits: "The prostitute does not sell her labor power; instead her trade brings with it the fiction that she is selling her capacity for pleasure...,,4 But behind that fiction, increasingly, the difference becomes negligible: "Prostitution can claim to count as 'work' as the moment work becomes prostitution. In fact the lorette is the first to renounce radically the camouflage of a lover. She already has herself paid for her time; from there she is not very far away from those who claim to be wage laborers" (V, 439). At the same time, and particularly in times of unemployment, workers must make themselves "attractive" to the firm: "The closer work comes to prostitution, the more inviting it is to describe prostitution as work - as has long been true in the argot of prostitutes. The convergence considered here proceeds with giant steps under the sign of unemployment; the 'keep smiling' [English in original] on the job market adopts the behavior of the whore who, on the love market, picks up someone with a smile" (V, 455).

Intellectual workers are no less prostituted. Benjamin notes that

40. Hence Marx's statement in the 1844 manuscripts: "Prostitution is only aspecific expression of the general prostitution of the labourer .. ." (V, 802).

41. The comment continues: "Insofar as this represents the most extreme exten- sion which the range of the commodity can experience, the prostitute was always a pre- cursor of the commodity economy. But precisely because the commodity character was otherwise underdeveloped, this side of it didn't remotely need to become so harshly prominent. In fact, for example, medieval prostitution did not demonstrate the crassness which was the rule in the nineteenth century" (V, 439).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

122 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

Baudelaire as a writer identified with whores. The Konvolut entitled "Baudelaire" documents the transformation of social relations under capitalism, of which prostitution is prototypical, by recording the transformation of erotic life (in the male) as it appears in Baudelaire's poetry. It is the honesty of Baudelaire, the shocking, raw immediacy of his sense impressions of the new urban reality, recorded before con- sciousness could manage to construct false reconciliations or whole- ness, which for Benjamin makes him so useful for critical insight, even when the poet himself had no theoretical grasp of the source of the problem. In Baudelaire's poetry, with the whore as allegorical figure in an "erotology of the condemned" (V, 438), the debasement of erotic life is presented in all its facets, and in Satanic lividness: the fetishistic fragmentation of desire, the dismemberment of the female body, the connection of sexuality and death, the isolation and fixation of the senses, the boredom and angry despair which permeates erotic life; the loneli- ness, and its result, ultimately, in impotence. But even if this poet iden- tified with whores, they remain the "other" for him, a field of symbolic rather than experienced meaning. Einfihlung, projection onto women passing by, as onto commodities in store windows, entails not the loss of self, but incorporation of the world (women, things) as fantasy images within one's own day-dreams (and then losing oneself in them). This is the flaneur's "illustrative seeing": Like an allegorist composing an emblem book, he writes "his reverie as text to the images" (V, 528). Benjamin noted: "Baudelaire's readers are men. It is they who have made him famous. They are the ones he redeemed" (V, 418). "For men [Baudelaire] means the presentation and transcendence of the lewd side [cote ordurier] in their sexual life" (I, 673). Benjamin comments: "Women don't like him" (ibid.).

No wonder. When Baudelaire inscribes his poems as allegory on the body of the whore, as a woman she is reduced to a sign, which is to suf- fer the same degredation as the sandwichman. Benjamin describes Einflihlung as the "unlimited tendency to represent the position of everyone else, every animal, every dead thing in the cosmos" (I, 1179). But women are not dead things. They are (silenced) subjects. If they are represented solely through the man as speaker, even the most out- rageous claims may be taken seriously,42 which would not be the case if

42. As an example of such a claim, consider Benjamin's totally serious speculation at the close of the Konvolut on fashion: "The horizontal body position had the greatest advantages for the female of the species of homo sapiens, if one considers the oldest specimens. It made pregnancy easier, as one can already gather from the girdles and bandages which pregnant women today are accustomed to use. Starting from here one might perhaps dare to ask whether the upright posture in general didn't occur earlier

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 123

they were speaking for themselves. When prostitutes have given voice to their experiences, and when they have described the modern de- basement of erotic life in terms of the behavior of men, one gets a very different picture of the problem. Listen to them:

[Capitalists and authorities exercise their power by day, then] ... off they go to pay us a visit. And once they've got us stripped to our chemises they stop their gabble, their illusions of grandeur collapse and their arrogance disappears. They all start stammering like little boys who want twopence to buy sweets (Amelie Hdelie, 1913). All these prosperous citizens ... tender husbands and affectionate fathers, arrogant lawyers, famous doctors and eloquent members of parliament turned out to be mentally sick. As a rule their wives had no idea of the type and degree of their aberrations. It was only on us that they ventured to make their appalling demands (Anna Salva, 1946).

Women in the modern era have not been silent. Nor have they re- frained from action. In Benjamin's notes on the 19th century there crop up in several contexts the revolutionary acts of women - the armed group of Vesuviennes in the 1848 revolution, for example - and he notes that the revolutionary "mob" took on the image of a cas- trating Medusa (V, 852). But these quotations (like those from Clarie Demar) are left largely unmediated by his theoretical commentary.43 At the same time he suggests a redemptive image of the whore "in dis- torted form, to be sure," which feminists will find disturbing: "the image of value to everyone and which is tired out by no one"; she becomes the "unquenchable fountain" of the sweet milk of "the giving mother" (V, 457). This is quite far from the militant image of women in

with the little man than with the woman. Then the little woman would have been for a while the four-footed accompanver of the man, as it is today with a dog or cat. Indeed, from this idea it is only perhaps one step further to the possibility that the frontal meet- ing of the two partners in the sex act was originally a form of perversion, and perhaps it was not in the least this mistake through which the woman learned to stand upright" (V, 132) [!].

43. Recent scholarship has documented the prevalence of the Medusan image of the crowd, and the connection between the fear of unconstrained female sexuality and the threat of proletarian revolution in nineteenth-century France. See Susanna Bar- rows, Distorting Mirrors (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982). See also Neil Hertz, "Medusa's Head: Male Hysteria under Political Pressure," Representations, 1:4 (1983).

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

124 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

the June insurrection of 1848, rebelling against capitalism and patri- archy (in distorted form, to be sure) by "cutting out the genitals of several prisoners" (V, 856).

Ultimately, perhaps, in the eyes of men whose erotic desire is dis- torted by commodity reification, potentially castrating women (like reptiles and other threats of nature) are safest under glass.

r ?4P

Askd& A Adimb, Aft

Mannequin vivant installed in a display window Miroir du Monde. 1936

V

Like the flaneur, the whore stands on the brink of extinction in the 20th century precisely when her characteristics have begun to per- meate all of erotic life. "Money has sex appeal" one hears, and this for- mula itself gives only the crudest outlines of a fact which reaches far beyond prostitution. Under the domination of commodity fetishism, the sex appeal of [every] woman is tinged to a greater or lesser degree with the appeal of the commodity" (V, 435-36).

Sexual liberation for women under capitalism has had the night- mare effect of"freeing" all women to be sexual objects (not subjects). It must be admitted that women have collaborated actively in this pro- cess. If men in the late bourgeois era, like gamblers, have surrendered

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 125

their power of agency to the blind forces of fate, then women, like whores, have used their power of agency against itself: they make themselves objects. Even with no one looking, and even without a dis- play case, viewing oneself as constantly being viewed inhibits freedom. As with all surveillance, it is a form of censorship. Throughout the Passagen-Werk Benjamin's observations on this process of the self- censorship of women and its connection with perceptions of class dif- ference are insightful (and his criticisms are deserved). He notes generally women's "participation through fashion in the nature of commodities" (V, 1211). He cites an 1883 description of the "tyranny" of fashion, to which women submit to maintain their social status (V, 125), and refers to Georg Simmel's comment that women rely on fashion due to the "weakness" of their social position (V, 127). The nature ofwomen's commodification, Benjamin observes, has changed to reflect the changing conditions of capitalist production: The regi- mentation of the assembly line has come to be reflected in a new form of sexiness: the chorus line, with its display of women "in strictly iden- tical clothes" (V, 427). In the modern city, women appeared as "mass- produced" through the "masking of individual expression" under make-up: "later the uniformed 'girls' of the review underline this" (V, 437).

Women in capitalist society - all women - impersonate com- modities in order to attract a distracted public of potential buyers, a mimesis of the world of things which by Benjamin's time had become synonymous with sexiness. Benjamin considers it the supreme mani- festation of the mechanization of nature, the victory of the inorganic over the organic. Like Baudelaire, he connects it with death, noting that psychoanalysis, which develops as a science under capitalism "doesn't hesitate ... to envisage the relationships between death and sexuality and, more precisely, the ambivalent apprehension of finding the one in the other"; the connection exists also in literature in the figure of the "femmes fatales, the conception of a female machine, artificial, mechanical, without standards in common with living crea- tures, and always murderesses" (V, 849).

Mechanical dolls were an invention of bourgeois culture. In the 19th century these automatons, as well as wax figures, were common. As late as 1896 the "doll motif had a socially critical meaning. Thus: 'You have no idea how these automatons and dolls become repugnant, how one breathes relief in meeting in this society a fully natural being' " (V, 848). Ironically, if playing with dolls was originally the way children learned the nurturing behavior of adult social relations, it has become a training ground for learning reified ones. The goal of little girls now is

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

126 The Flaneur, the Sandwichman and the Whore

to become a "doll."44 This reversal epitomizes that which Marx con- sidered characteristic of the capitalist-industrial mode of production: Machines which bring the promise of the naturalization of humanity and the humanization of nature result instead in the mechanization of both.

~~i,"?owl "t A4 0 4? kAll 4?Wa _.

44,i

,00 ~ llj~:,"'41 voii

It

Street Hawkers, Wind-up Toys, and Children Miroir du Monde 1936

Marx in his early writings claimed that the quality of erotic relation- ships provides an index as to the degree of social progress: "The relationship of man to woman is the most natural relation of human being to human being. It therefore reveals the extent to which man's

44. Similarly, where Dickens could still see an "animated sandwich," human life lending its qualities to the thing( a quality which gives Grandville's work a socially utopian character), the 20th century sees simply the "sandwich man," the human-turned- thing.

This content downloaded from 216.165.95.73 on Mon, 29 Dec 2014 11:31:58 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Susan Buck-Morss 127