The European Rating Fund How to Reform the Credit Rating ... · 1 The European Rating Fund – How...

-

Upload

phamkhuong -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of The European Rating Fund How to Reform the Credit Rating ... · 1 The European Rating Fund – How...

1

The European Rating Fund – How to Reform the Credit Rating System

For the Trento SGEU Conference 2016

Dirk-Hinnerk Fischer

PhD- candidate at:

Ragnar Nurkse School of Innovation and Governance

Tallinn University of Technology

Akadeemia tee 3

Tallinn 12618, Estonia

E-mail: [email protected]

Abstract

The complexity of the financial markets and their controlling entities make structural reforms highly

problematic and controversial. This paper addresses the deficiencies of the Credit Rating Agency

market. The contribution to this long and ongoing discussion is a profound reform for the market.

The reform is based on the introduction of a communicational layer taking over the contract

distribution between issuers and agencies. This process changes the market fundamentally, but it

does not impact either side´s capacity to make profit. The distribution of products for ratings gets

anonymized and randomized, which eliminates most conflicts of interest that are preventing the

market players from preforming as they should. The reform proposal is focused on the European

Union, but the structure is easily adaptable to all other markets.

Keywords

Credit Rating Agency, Financial Market Supervision, Financial Control, Financial Institutions, Financial

Reform

1. Introduction

The market for credit ratings is a highly controversial topic. Numerous problems with conflicting

interests and unsatisfactory performances are documented. Thorough reforms of the markets have

not really been implemented. Moreover, most of the solutions proposed in the academic debate

have their flaws as they do not sufficiently address some of the crucial conflicts of interest that

plague this market.

This paper proposes a new distribution and administration system for the rating agency market. The

model focuses on the European Union, but is easily adaptable to other parts of the world. The

European Rating Fund (ERF) is a simply designed communication and distribution platform that

eliminates the conflicts of interest for the rating agencies. The objective of the ERF is to enable the

rating agencies to perform more accurately in regard to financial market risk assessment.

This paper introduces an ERF as one possible design for a completely new supervisory entity that

provides a protective layer for the rating agencies and a payment pool for the issuers, without

creating high costs or time-consuming bureaucracy. The ERF mediates between companies issuing

financial market products and the rating agencies. It introduces a randomized contract distribution,

payment and communication system that eliminates the conflicts created by the current structure

without impacting the independence and profitability of either side of the market. Market failures

deriving from oligopolistic structures, gaming behaviour, moral-hazard, as well as conflicts of interest

2

will all be eliminated by this new regulatory entity. This enables the credit rating agencies (CRAs) to

report more accurate results.

Protection from these conflicting interests is the core reason for creating the European Rating Fund.

The ERF is a public entity which intermediates all communication, regarding ratings, between the

CRAs and all issuing companies. Within the ERF a randomized matching process takes over the

contractual agreements between the particular CRA and issuing entity. The ERF can be pictured as a

layer in between the two markets. Its introduction requires a few legal changes in the market as

contracts are no longer made between the companies directly, but with the ERF instead. No rating

that was not distributed by the ERF is accepted as a valuable rating.

Within the European Union the ERF could be created as a sub-entity supervised by the Single

Supervisory Mechanism, but many different arrangements are possible. Some will be exemplified

within the paper.

The structure follows a classical approach. It will start with the literature review, which explains the

history, purpose and most importantly the problems for and of the credit rating agencies. Chapter

four then focuses on the most influential alternative reform proposals as the ERF is not the first

solution attempt. Following that, the analysis continues with the description of the design of the ERF

so that the reader is able to understand the positive and negative aspects of this new structure. The

last chapter summarizes the paper.

2. The credit rating market and its historic development There are countless studies on the CRA market and its problems. This literature review will focus on

the most important issues. It will start with a brief analysis of the historic development of the CRAs

and their current importance for the entire financial markets. This entire chapter and its subsections

are focused on three core problems of the market for which the ERF finds solutions. The three issues

are the market composition, the payment structure and the summarized market failures.

Criticism of the performance of the CRAs did not start only after the subprime crisis. The

underperformance of the CRAs and the systemic problems that triggered this led repeatedly to

attention in times of crisis. (Kuhner 2001) The last times their performance provoked broad criticism,

were the Enron crisis and the subprime crisis. (Hill 2002; Hill 2010; White 2009) These crises also

emphasized the controversial performance of the CRAs in warning the markets of possible threats or

excessive risk exposure. (Dennis 2008; Notermans 2013; Sy 2004) But the CRAs have proven

themselves in more than these two crises as inefficient reporting and warning tools. (Dennis 2008;

Skreta & Veldkamp 2009; Véron 2011)

The CRAs are supposed to supply the market with information about the risk, the stability and the

reliability of particular products or institutions. In our economy there is no perfect information which

makes it necessary to give investors the ability to inform themselves realistically on the risk of a

product. The issue of incomplete information makes it also obvious that the CRAs are not able to

perform without errors, as also they are only trying to develop probabilities. Thus, some credit rating

error has to remain acceptable. This service should be provided by a tertiary party to ensure the

independence of the analysis. This economically important role is performed by the CRAs. The CRAs

developed out of the basic need for information. Potential investors could buy information on bonds

against a small fee. The biggest players in the market are and always have been the three US

American companies of Standard & Poor´s, Moody´s and Fitch. These companies started as

publishing houses and developed from there on. They came from the background of publishing

information on railroad bonds in the early 20th century. These three companies traditionally

published their information and sold it to speculators and investors. (White 2010; Manns 2009)

Roosevelt and his “New Deal” raised the relevance and impact of the agencies. They became a part

3

of the official stock exchange supervision and were thus publicly protected and enforced to rate the

security of investments, as numerous products needed ratings to be allowed to be traded on the

official platforms. (Lütz 2002) This impact has not diminished over time and the US American model

spread around the world with the globalization of the financial markets and later with the adaptation

of the Basel agreements.

The European Union reacted over time. The European Securities and Markets Authority has taken on

the difficult task of increasing the accountability of the CRAs within Europe. This supervision entity

covers one important part of the supervision of the performance of the CRAs, but the incentive

systems for the CRAs remain mostly the same. (CFR.org 2015)

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision that supported and built the CRA´s influence with the

Basel I Agreement from 1988 and cemented the fundamental role for the ratings and the CRAs in the

agreement popularly called Basel II, (BCBS 1998; BCBS 2006) distanced itself from the too important

role of the CRAs in a report on credit risk estimation from 2015. The entire publication offers no

solution for the problem of the weak performance of the CRAs, while the dependence on these

entities remains, but it shows a shift in perspective. (BCBS 2015) The agreements also furthered the

view that the bank itself can be seen as its first control entity as it has to fulfil the equity and liquidity

requirements. (BCBS 2011) This means that the CRAs are losing a little bit of their influence, but as

much of the risk estimation is still based on their calculations they are not really threatened. Further

alternative rating mechanisms will be introduced for a further improvement of the system. (BCBS

2015)

A big systemic change turned the entire market upside down when Moody´s changed the system of

payment in 1971. The other big players in the market adapted the model in the following years. Up

to that point the interested investor had to pay for the information. Afterwards the issuing entity had

to pay for a rating. The main arguments for this change were that photocopy machinery was just

becoming a standard and the company feared the use of unauthorized copied samples and thus a

massive loss in revenue. Another argument has been to lower the entrance barrier for investors.

(White 2009; Rügemer 2012a)

The market structure and the payment system have been criticised by researchers and journalists on

various occasions. (Manns 2009; Dennis 2008) Comparative studies with the CRAs using other

payment models have shown that the issuer-pay-model leads to inflated ratings in comparison to

investor-pay-models. (Xia & Strobl 2012) This theoretical comparison means that the current

payment system really has distorting effects on the performance of the CRAs. The payment system

lays thus the fundament for the first big impact on the market, which is the conflict of interest.

The second big issue with this payment system is that the CRAs generate a significant share of their

revenue from rating complex tools and products. The complexity of these products gives the CRAs an

incentive to inflate some ratings that outweighs the concern about quality work and reputation as

the complexity covers grey areas in the products. The issue is that highly complex products are hard

to evaluate and rate. The supervision of these complex ratings on complex products is even harder,

which implies that a payment system in which both sides profit from higher ratings, without a proper

control of the reliability of the model used to rate the product can be easily crooked. (Mathis et al.

2009)

Only a few substantial reforms occurred since the changes in the payment system were

implemented, one of which was the introduction of the rating outlooks and reviews, or commonly

called “watchlists”. These enabled the CRAs to inform the public about products which would

probably be unable to sustain the credit quality. Products indicated on these lists are under

observation and the watchlists focus on short term developments for the products. These indications

thus hold a lot of adaptive power for the CRAs without directly downgrading a product. (Haan &

Amtenbrink 2011) The watchlists enables the CRAs to warn investors and keep the ratings up to date

4

in accordance with market and product changes. This mechanism improves the feedback mechanism

between market and issuer.

2.1. The importance of the CRAs The CRAs are a crucial basis for information on a variety of products within the highly diversified

financial markets. The ratings hold a crucial position in the decision making process of most

investors. They are also crucial for our modern regulatory system and are the determining factor for

the size of most equity ratios. This makes them an important subject for regulation. Over the years

some of this regulation turned out to be mis-regulation and some of the results of this mis-regulation

have been mentioned above.

Regulation can worsen a crisis if the already struggling financial market players are obliged to

increase their equity base over proportionally when the ratings are dropping, which means that

prices are dropping and the market players are already losing money. This forces them to re-order

their portfolio and react to the changed situation, but at the same time they need to increase their

equity bases to comply with the regulation, as the ratings for the products are dropping. In the end

this is a self-enforcing cycle of more needed equity and less tolerance for risk, which drives the

involved entities deeper and deeper into trouble. This vicious cycle can prevent banks from lending

and can thus transmit troubles on the financial markets to the rest of the economy. (Ioannidou 2012;

Mizen 2008)

The CRAs are thus indirectly holding a position of systemic importance, which is problematic if we go

back to the payment structure. The ability for the CRAs to impact the capital requirements of their

clients while being paid by the same entities is controversial, as mentioned. The CRAs determine the

risk weights with their ratings, which then again determine the amount of the necessary capital

adequacy ratios. This system does not hurt anyone during times of good economic development, but

during times of crisis the triggered process is highly problematic. The crisis would melt the value of

numerous financial market products. The bank would thus be in need to restructure its assets, which

most of the time goes along with an increased need for liquidity. On the other side the ratings for the

products are dropping and thus the capital adequacy ratios are increasing. So the anyways stressed

banks would be put under even more pressure by the regulation, but banks are not the only financial

market entities that would be hit by such a downgrading circle. Some pension and insurance funds

would also be forced to sell off all products falling below triple A. More and more funds are impacted

if the rating falls even lower than that, (Sinclair 2008) which means that losses for these entities are

almost inevitable, as a product that the majority wants to sell is very probable to lose value. The

entire situation leads to a cycle of strong incentives for high ratings for the banks which are, due to

the payment structure able to directly impact the revenue of the CRAs. This makes the CRAs directly

dependent on the satisfaction of the issuing entities with the rating grade for their product.

The resulting cycle was beautifully described:

…the growth of mortgage securitisation generated fee income – to banks and mortgage

brokers who sold the loans, investment bankers who packaged the loans into securities,

banks and specialist institutions who serviced the securities and ratings agencies who gave

them their seal of approval. Since fees do not have to be returned if the securities later suffer

large losses, everyone involved had strong incentives to maximise the flow of loans through

the system whether or not they were sound.

(Crotty 2009, p.565)

This led to a circle of excessively optimistic ratings, especially in the case of Mortgage Backed

Securities and Collateralised Debt Obligations, which made up for about 40% of Moody´s revenues in

2005. (Crotty 2009)

5

The CRAs fulfil their systemically important role in times of economic stability to a satisfactory extent

without any public regulation. (Kraft 2011; Utzig 2010; Akdemir & Karslı 2012) The conducted

research shows that the influence, especially on sovereign level, has been and still is significant for

our system, even though it has to be mentioned that this influence differs greatly regarding the

product type and the particular market situation. One study found that downgrading of sovereign

ratings has a significant response for government bond yield spreads. (Afonso et al. 2012)

Downgrading has also a significant spill over effect on related countries, depending on the type of

announcement, the announcing company and the country that is downgraded. (Arezki et al. 2011)

For developing countries the little surprising correlation between factors that support the repayment

of bonds and the enhancement of CRA ratings have been documented. (Archer et al. 2007; Ferri et al.

2001) This leads to the conclusion that the activity of CRAs is relevant to sovereigns.

For bond prices on the other hand little evidence of announcement effects has been found, but it has

to be mentioned that the sample of European banks in this case is not very diversified, which might

distort the results of the study. The same study on the other hand found strong effects of ratings on

equity prices. (Gropp & Richards 2001)

For stock and swap markets the literature shows that the ratings by all three agencies are anticipated

by the market, but downgrade still had a significant impact in 2004, (Norden & Weber 2004) which

goes along with the finding that there is no significant difference between anticipated downgrades

and unanticipated changes. (Purda 2007) Other studies found that the tool of the watchlist turned

into a monitoring device, which enables the CRAs to put pressure on the reviewed companies,

especially for low quality borrowers. (Bannier & Hirsch 2010)

Most studies, also the one´s named here, on the ratings of governmental and private entity products

emphasize the short term impact of the ratings while the long-term impact is less significant.

(Notermans 2013)

While the importance of the CRAs and their work is questioned by some researchers, others even see

them as one of the core reasons for the emergence of the subprime crisis as they enabled the

volume of the subprime mortgages traded in the first place. (White 2009; Hill 2011) A general

agreement seems to be that the subprime crisis was at least partially triggered by all the weak and

non-performing control mechanisms and not only the CRAs. (Blundell-Wignall & Atkinson 2009)

These mechanisms were not really enabled to work as the circumvention of capital requirements was

made too easy, for a systemically relevant number of companies, which led to a weakened structure.

(Kao 2012) The problem was enabled by the absence of a global regulatory framework among other

things, as national regulatory attempts often trigger cross border regulatory arbitrage. (Moshirian

2011) This general problem of financial market regulation also has to be kept in mind when talking

about the CRA market, as the cross border effects can also deter the result of implemented

regulations.

All these aspects led to a decreased credibility for the work of the CRAs. They suffered a hit mainly

because the ratings for securitized mortgage-backed securities were tremendously over optimistic

before the crisis. (Brunnermeier et al. 2009) Warning signs were there and the crisis could have been

predicted. The crisis had very similar development patterns as former financial crises. (Reinhart &

Rogoff 2014) But the CRAs did not react in time and not fiercely enough. (Longstaff 2010) This too

slow and too small reaction scratched their reputation, as they were seen by many as a reliable

source of information for complex products before the crisis. (Mizen 2008) The reports that the CRAs

helped the issuers to construct the instruments they themselves rated in the end did not help to add

additional confidence in the reliability of the CRAs. Some of the very famous collateralized debt

obligations have been optimized in this way to achieve an optimized rating grade. (Freeman 2009)

The same accounts for the countless reports of more and more information about agencies

6

disregarding changes in the products and markets to protect their own market shares. (Taibbi 2013)

This public confrontation led to a further loss in trust after the crisis.

One crucial systemic problem with the CRAs is the role they played in the contagion process of the

financial crisis. After the beginning of the crisis, the agencies downgraded numerous products. This

triggered an increase in the equity cushions, held by the market players, to fulfil the nonlinear capital

requirements in respect to the rating of the particular product. In the end, banks were forced to

generate liquidity very quickly and in great volumes, which then again led to further asset sales into a

collapsing market and borrowers were forced to sell securities due to margin calls. These circles froze

the credit markets, which suffered badly due to the credit crunch, which then again backfired into

the financial markets and so on. (Crotty 2009) Every player in this structure behaved rationally. The

blame can thus not be with one kind of organisation alone. The blame has to lie with the particular

incentive system, but the cycle could have been stopped if the CRAs would have been regulated

appropriately.

In conclusion it can be said that the CRAs are at the epicentre for many regulatory attempts. So if

their performance is unsatisfactory or even crooked the safety net for the entire financial market

looks more like a sail after a storm than like a reliable source of stability.

2.2. The market failure within the Rating Agency Market Regulating the CRA market is a controversial and complex issue. Estimations focused on the

regulation of CRAs have shown that regulators are facing multiple challenges within this very

particular market. Regulators need to prevent inflated as well as collusively derived ratings. (Stolper

2009)

Generally it can be said that the special interest towards the CRAs, as they are private entities, comes

from the public role that they are playing as deputies. Deputies in this case means that private

companies are entitled by law to occupy a public role. The problem with such agents is that most

states struggle to make such entities accountable for their performance, which is also the case in the

CRA market. A certain level of accountability for their risk assessments would give states, but also

other market players a certain level of leverage to engage the entities and would hence incentivise

them to improve their performance. (Manns 2009; Schwarcz 2002)

Another important issue is the basic economic theorem of moral hazard and the more general

conflict of interest. Both problems have been associated earlier with the CRAs by other researchers.

(Kao 2012; Kalinowski 2012; Dam & Koetter 2011)

Moral hazard occurs if a decision making person takes more risk than rational, only because someone

else has to take the burden of the risk created by the decision. The case of the CRAs is one particular

case that might be described by moral hazard. Moral hazard appears in the CRA market as the agency

suffers not under the possible results of too optimistic ratings. The CRAs gives a rating and other than

its reputation, among investors it has nothing to lose if a rating is too optimistic. This would seem

important, but the problem is that the investors do not have a direct link to the CRAs anymore, which

means that it has very little significance for the CRAs. So if the markets were mainly based on

reputation of quality work the issue would not be as big, but the market is based on the described

payment system, which incentives the CRAs to follow their clients interest, which was triggered as

the market did not reward accurate ratings anymore. The persons carrying the biggest share of the

risk are the investors, who do not have a possibility to impact the ratings. This alone invites the

agencies to gaming or speculative behaviour, (Coffee 2011; Hill 2010; White 2009) even though some

researchers claimed the reputation pressure would equalize these effects, but in regard to those

results one has to notice that this research was conducted before the last fundamental financial

crisis. (Schwarcz 2002)

Another issue is that the clients of the CRAs and thus the issuers of the products have the

7

opportunity to just move to another agency for a rating, which incentivises the agencies to give

optimistic ratings regardless of the situation in the markets. (Diomande et al. 2009) Reputational

considerations, like the classical theory of the “reputational-capital”, have to be put aside at this

point, as empirical facts proof them wrong. The reputational incentive deriving from the investors is

simply weaker than the incentive to make profit and also to please their direct customers. (Dennis

2008)

The market itself is, in the current composition not able to solve the market failures on its own.

Regulatory steps need to interfere at this point.

Another conflict of interest that cannot be solved by the markets alone derives from the CRA market.

Investors and sales agents are, among other influence factors, relying on the information provided by

the ratings and the resulting level of risk for a particular product. The other side of the coin is the

problem that the CRAs have a self-interest in their rating grades, as described earlier in the cyclical

development of the over optimistic CDOs and MBSs grades. The CRAs are in a position of asymmetric

information, as they are supposed to have more information on the products than the rest of the

market.

Issues of asymmetric information can partially be solved by increased transparency. It has been

shown that regulatory reforms work best, if transparency is given and if they empower private-sector

control. Successful reform triggers incentive systems to foster private companies to conduct efficient

control themselves, (Barth et al. 2004) which means that the issuers need to be incentivised to share

all necessary information to the rating specialists.

This sharing of models and information has a direct connection to another fundamental problem of

the current CRA market structure. The issue has been named “the burden of proof”. This burden lies

currently with the agencies, which means that each CRA has to be able to understand the inner

working processes that determine the effects of a product. They are supposed to predict its

behaviour in every possible scenario. For simple products this is certainly not a problem, but for

modern and advanced products this can be very challenging. A former Standard & Poor´s chief credit

officer for structured finance admitted that the model used for mortgage-backed securities in the

years 2005 and 2006 was only a little more accurate than a coin flip. (Jacobides 2014) So, the issuer

needs to provide sufficient information and transparency on the products to enable a reliable rating.

This emphasizes that the burden of proof has to lie with the product engineers from within the firms

and not with the CRA. The financial engineers should be able to explain how a product works and

reacts in particular market situations. The end is, that the CRAs did not receive, claim or use sufficient

information to adequately rate the more complex products. The incentive for not claiming, using or

protesting for the information is given by the conflict of interest described above.

Collateralised Debt Obligations for example were priced by highly sophisticated models, which were

hard to verify and harder to retrace. The value estimation worked in a “marked-to-model” manner

rather than in the usual “marked-to-market” way and was misrated by the CRAs, as a reliable

calculation for these products was not really possible with the provided information and the created

models were not really up to the task. (Roubini 2008) The switch of the burden of proof means that

the constructing entities have to be obliged to provide all information that the CRAs are requiring, so

that they are able to understand the inner workings of such products. (Kalinowski 2012) This step

provides a crucial advancement as it is documented that some algorithms within the market, high

frequency or not, are not sufficiently understood to measure their performance even in times of

usual service much less in times of crisis. (MacKenzie 2014)

The incentive to provide good ratings becomes even more forceful with more advanced products,

which means that the incentive to switch between agencies is getting bigger the more complex a

product is. Every CRA is hence forced to keep the interest of their customers in mind, as these could

just switch to another supplier. The issuers on the other side have a need for good ratings. This

8

significates that they will move to another CRA if their agency is not preforming as hoped for. The

payment system has produced various documented cases in which the behaviour within the markets

was even related to methods close to bribery and fraud. (Rügemer 2012a; Taibbi 2013) Incentives for

behaviour like this on both sides lead to contradicting interests and inflated results. (Skreta &

Veldkamp 2009) The issuers can pressure the CRAs for higher ratings and threat to move to the

competition, while the CRAs are incentivized to accept higher ratings for not as solid products to fulfil

their customer’s interest. The CRAs are thus struggling to rate with accuracy.

A part of the issue is the tendency of herding behaviour in the CRA market, which means that if one

agency downgrades a product the probability that another agency will downgrade the same product

increases. (Güttler & Wahrenburg 2007) This might sound like a contradiction to the last paragraph,

but it is not, as the market and issuers’ situations for the particular cases are different.

Nevertheless, herding behaviour is yet another indicator for the distorting impacts that the markets

are subject to. The distortion reflects on the investors, who can take these tendencies into account

and could already speculate on further downgrading, if another agency has done so. Which means

that the risk evaluation of one CRA partially depends on that of another agency, which puts once

again the performance of the agencies at question, even so this behaviour can be rational in cases

where new information came up.

3. Solution attempts – numerous proposals

The market structure in combination with the payment system is not a sustainable mixture. In the

academic and political world some extreme opinions are circulating regarding a solution of the

current trap, the CRAs are caught in, (Rügemer 2012a) but the most probable outcome is that the

ratings are kept mandatory. This is actually not harmful as the communication and control provided

by these entities can be helpful for the improvement of a working reaction mechanism. But the

performance has to fulfil the needs of the markets, which means that it is necessary to reform the

system. So if the CRAs are private companies and they are supposed to perform satisfactory as

deputies, in stabilizing the markets, they need to be controlled in a more efficient way. The issue

with controlling private entities is that it is cost intensive and complicated for both sides, which

means that a more promising approach would be to free the CRAs from their conflicts of interests

and enable them to work as efficient as possible.

Most experts in the field see the CRAs with critical eyes nowadays and so does the Basel Committee,

which issued a consultative document in March 2015 that reads: “In revising the treatment of bank

exposures, the Committee aims to remove both references to external credit ratings and the link to a

sovereign´s credit risk.” (BCBS 2015, p.5) The Committee, as mentioned, aims to introduce measures

to limit the importance of the CRAs for banks. The current proposal of the Basel Committee would

lead to an increased self-control of the banks, which are underlying their own strong incentive of

survival. This first alternative solution proposal thus aims to replace the influence of the CRAs with

self-controlling power or the banks. The problem with this proposal is that the incentive systems for

the management and key employees are most of the time short-term oriented, as most contracts are

set out for only a few, often two years and the individual performance is measured in turnover or

profit. This means that for these entities the importance of long-term and sustainable decisions has

to be secondary. So in the end systemic changes should be implemented and deputies or public

entities should control the markets and should represent the interest of the society. This is important

as the company’s interest as well as the market´s interest are represented within the firm, but the

interests of the society and other markets are missing. If one of the three interests, companies-self-

interest, market-interest and public-interest are not represented within a systemic relevant market it

will lead to problems with stability in the long run. The argument that competition will place the

9

general interest first cannot hold for in this particular case as the self-controlling mechanism under

the current market structure would trigger a race to the bottom situation in which all involved

entities would promote their products as much as possible with the least amount of control possible.

The long-term interest is erased from the equation and the classic liberal argument can thus not

work in this case.

Regardless of the problems with one particular proposal, all have their upside as the tendency has

been documented that the performance and accuracy of the CRAs increases if their market position

is threatened by a possible public regulation or enforced public discussions on the topic. (Cheng &

Neamtiu 2009)

Reform proposals, like alternative payment structures with a supervised user fee approach have

been proposed and would actually solve the intrinsic problem of the agencies. This second proposal

is built on a competitive auction process and thus an adaptation of the old subscription process. The

user fee approach develops around the competitive bidding process. The CRAs would have the ability

to put their products out forbidding. All interested buyers would then be able to bid for each

product. The approach is supposed to contain the costs for the ratings, widen the competition among

the CRAs, facilitate the entrance of new companies and evaluating the attractiveness of market-

based assessments. The bidding would be controlled by a public entity, which should ensure the

smooth development of the process. The problem is that this approach is not solving the gaming

behavioural problems that are challenging the market. (Manns 2009) The proposal binds the CRAs to

the investors seeking information as clients and the issue of reputation would gain importance again,

but it has to be assumed that the described movement from one CRA to another in search for the

best rating would not be eliminated. Which would put the rating agencies under the same pressure,

under which they currently already are, as the factor of herding behaviour would also regain

importance.

Going back to the original subscription based payment model is due to technological development

and thus broad availability of the ratings not possible anymore. The user fee approach circumvents

this problem as the winner and thus receiver of ratings are a limited and easily determined group of

entities or people.

Other proposals like the third reform proposal for this paper are public rating agencies, which are

supposed to rate the ratings of the private agencies and would start their activity by researching the

market before they would start rating themselves are a well discussed topic. On the one hand the

creation of a public rating agency is an attempt to ensure the performance of the entire system. It

ought to provide the three big CRAs with a real competitor that is accepted by the market. The public

CRA could prevent any herding tendency, because of its public backing and thus independence from

the market. On the other hand the proposal of a public CRA can lead to a new situation of moral

hazard, in regard to national political interest. To keep these interests from dominating such an

entity it would be necessary to develop it independently. Within the European Union the creation of

a European Rating Agency has been discussed intensively, but such an entity would most probably

never gain credibility in regard to sovereign ratings, especially not in times of crisis. A public rating

agency tackles some problems, but it resolves not the basic conflicts arising from the market

structure. (Diomande et al. 2009; Schroeder 2013; Tichy 2011; Eijffinger 2012) Even if the public

rating agency would be created in an independent fashion that would enable more credibility the

public rating agency approach would not able to really free the market of its profound conflict of

interest and thus market failures.

Some even more controversial proposals delegate the ratings to the ECB directly or plan to

nationalize the CRAs. Delegating the ratings to the ECB is intrinsically flawed, as it would lead to a

direct conflict of interest within the ECB, as the adequate measures in monetary policy can be

10

contradicting to the adequate measures for the financial markets.

Nationalizing the CRAs is particularly controversial and most of the time even seen as completely

unrealistic, as it would not solve enough issues in order to provide a valid argument for such an

aggressive intervention. (Eijffinger 2012) The public agencies would underlie the same trust issues as

the public agency described in the paragraph above.

A fourth and less known proposal is the idea of putting the CRAs under pressure by a “Credit

Research Initiative”, which is a supposedly independently financed entity that provides ratings as a

public good. The logic is that such entity providing universally available ratings forces, sooner or later,

the “for profit” CRAs to increase their performance or search for their niche service within the

market. The highly demanding project is developing, but it is still a long way from the objective.

(Duan & Van Laere 2012) The problem with the system is that the credibility is not necessarily given

and the project might only gain traction after another crisis in which the ratings of this agencies

would be more precise than the ratings of the current CRAs. The second issue with this proposal is

that its independence needs to be questioned as the project requires a lot of funding and some of

the sources of this funding might have their own interests.

The fifth and last alternative, which is the closest to the design of the ERF was introduced by Welfens

(2010). All issuers are supposed to pay into a pool, which then finances the rating itself and

distributes it with the help of competitive tenders. The ERF follows a similar approach, but it takes

another and further step, but the ERF, introduced in this paper, cannot solve all of these problems

singlehandedly. Additional reforms are needed to enable the resolution of all systemic problems of

the CRA market successfully.

4. The European Rating Fund The basic idea for this new entity is that the ERF is a distribution layer between the CRAs and the

issuer. All products that are to be rated are matched with a randomized process within the ERF to a

CRA. This step eliminates all problems deriving from the current payment system. Additionally the

gaming behaviour for issuers of switching between CRAs is minimized, as it cannot be ensured that

another CRA will receive the product in the second attempt. On the other side, this system eliminates

the incentive for the CRAs to provide over optimistic ratings, as the issuer is not able to switch the

provider, as the rating distribution is randomized.

In detail, the creation of this entity would, under the design presented here, mean that a one-time

public investment would be necessary to create the ERF. The further funds will be provided by the

issuing parties. A small percentage, not more than 1%, of the costs for a rating could be kept by the

new public entity to finance the ongoing costs and the updating of the system. The price for one

rating, with regard to its volume and complexity, could be determined in a yearly updated agreement

between representatives of the CRAs and the issuers with a supervision from the ERF. This step

would mean that the price would become insensitive to market pressures.

As important, for the success of the ERF, as the changes to the payment system are, is its distributive

function. The detailed distribution process of the ERF could look like the following. The issuing

entities send the application for all new products, for which ratings are wanted and all necessary

information to the ERF. The CRAs on the other hand send the number of ratings they would like to

claim to the ERF. The administration of the ERF then runs a randomized matching process which

distributes the products to one of the agencies. This randomized process does not mean that the

development of the company becomes a gamble, it rather follows clear lines, but this will follow in

more detail later.

This completely new distribution system cuts the direct contact between issuers and agencies and

eliminates thus the gaming incentive for both sides. The opinion of the issuer is no longer relevant to

the CRA, as the contract is not made between the agencies and the issuing company, but respectively

11

with the ERF, and the CRAs do not need the approval of the issuing entity to receive further

contracts. This fact cannot be stressed enough as it is in complete contrast to the current system. The

number of contracts an agency receives is not impacted by the impressions or preferences of the

issuer. The agencies have the ability to improve their probability of receiving a certain number of

ratings, but they do not have the ability to influence the products they are getting. The impact

factors on the number of claims used in this example will be explained in more detail. The impact

factors are good performance, adequate response time and the number of claims the particular CRA

reports to the ERF. A formula with these or similar incentives can be designed in many ways and

there is really no importance to how it looks as long as it fulfils the crucial requirements of

incentivising high quality performance.

Just a few other ways to exemplify such distribution influences could be that all sellers of products

with ratings receive an automated formula, as most trades are electronic anyway, which gives them

the opportunity to rate the trust they have in a particular rating, on the product they are selling.

These points could then be compared to industry averages and companies with higher points in one

kind of product would receive more ratings of this kind than other companies. Professional traders

could receive time saving variants of such enquires. Another way could be to test products issued by

the ERF so that very comparative results would be received. So, one can see that there are numerous

ways to incentivise high quality performance.

Another important aspect for the ERF is the settlement of disputes between CRAs and issuers. A first

case is that if any information is missing the CRA is supposed to claim such information indirectly

from the issuing entity through the ERF. This standardized process could be organized in form of an

anonymized email distributor. The process can be completely automatized, which would enable a

transmission within milliseconds and would thus not take a lot of time. Another form to organize this

claim for more information would be an online form that the rating specialist fills and which is

transmitted over a platform of the ERF to the responsible issuer. A lot of other technical solutions are

possible, but elaborating all of them is not the purpose of this paper. If the issuer is not willing or

able to provide more information it denies further data. The CRA can then decide if a rating is

possible without the additional data. The CRA can deny the rating if it is not possible and the ERF will

inform the issuer. If the issuer insists on receiving a rating the ERF will send the product to another

agency. The claim will then be tested by the other CRA and if this agency also reviews the provided

information as not sufficiently transparent the product receives the rating grade of not sufficiently

transparent. An additional upside deriving from this step is the limiting of unnecessary complicated

products as the CRA could just not rate them in a reliable form. It could be a T instead of an AAA, but

this design question can be left up to the ingenuity of the CRAs themselves.

The ERF is also a basis for information in court in case of charges against an agency and should be

heard as its position enables it´s employees to have detailed insight to the market and its

development. Such system of charges can only work if the burden of proof is shifted towards the

issuing entity. The responsibility for the CRAs in this case is that they need to be able to prove in

cases of question, that they actually used the necessary information for each rating. If the CRAs are in

particular cases only able to close in heuristically on the results regarding the performance of a

product during different market situations, they are not to be made reliable for their rating. The CRAs

needs to be able to fully understand a product in order to rate it. This step gives the CRAs a more

profound insight, but it does not solve the accuracy of ratings in general as the macro influence

factors are not considered here.

Another point would be that the ERF would need to be entitled to enforce penalties in case of

inappropriate behaviour or unrealistic estimates in regard to the ratings, which would be reflected in

12

the distribution function as well. The ERF also needs to be obliged to report any further misbehaviour

to the authorities and depending on the case even the press.

4.1. One exemplified composition of the ERF

Up to this point the approach was explained more or less generally. The following section is an

exemplified process that can be created in many similar forms, but the way presented here is a first

idea of how to do it. The formula is part of the distribution process within the ERF. The process of

distribution will work in two steps. The first step is the determination of the rate of supply and

demand. Supply in this case is the number of applications for ratings and demands are the claims

made by the CRAs to receive products in need for ratings. The first step is thus the determination of

how many claims every CRA is getting filled.

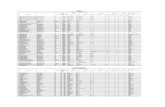

For company s this process looks like:

(I) 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 = ∑𝑛𝑎𝑝𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑠 − ∑𝑛𝑐𝑙𝑎𝑖𝑚𝑠

One could say that 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 = 𝑆𝑢𝑝𝑝𝑙𝑦 − 𝐷𝑒𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑑

Hence:

If 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 > 0 -> Matching of all ratings in accordance with step two and transmission of all

not allocated ratings to the next day

If 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 = 0 -> Matching of all ratings in accordance with step two

If 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 < 0 -> Distribution of the real quota through formula (II) and matching of all ratings

in accordance with step 2

s = company

x = Number of cases of liabilities – number of penalties from investors, issuers or the ERF (need to be

accepted by the ERF) – erased after two years without new claims

n = Number of years

y = Number of too fast or slowly published ratings – erased after two years without new problems

c = Number of claims of the agency

𝑖𝑛𝑑∅ = Industry average

The second formula comes only into place if the first step has resulted in𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 < 0.

(II) 𝑄𝑠𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑙 = 𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛 − (∑(𝑥𝑠1

2+√𝑥𝑠222+ √𝑥𝑠𝑛

2𝑛)

𝑥𝑖𝑛𝑑∅− 1) − (

∑(𝑦𝑠12+ √𝑦𝑠2

22+ √𝑦𝑠𝑛

2𝑛)

𝑦𝑖𝑛𝑑∅− 1) − (

√𝑐𝑠2

√𝑐2

𝑖𝑛𝑑∅

− 1)

The formula used here tries to cover some of the other systemic problems of the CRA market. It uses

thus accountability as an impact factor, but this is by no means necessary for every formula with this

position and function. The point of this formula is to set the right incentives for the rating agencies.

The formula incentivises against over reporting and for high quality work, which also sets a very first

step towards a new possibility for more reliability on the ratings. A company that is poorly or hastily

performing can suffer under its own poor performance especially if the poor performance continues

over time.

The point of liabilities in the formula is that the rated products might not have a rating they deserve.

In this case the issuers and even the clients buying these products are able to charge liabilities

13

against the rating agency. These liabilities can be claimed against CRAs if a rating has not kept up to

the claims a particular grade is pronouncing. Liabilities can be claimed by investor if they are not

believing that the CRA used all necessary, provided information to create the particular rating. The

CRA needs to explain why the rating in the particular case was supposedly wrong, in response to the

charges. The liabilities are thus not focused on the actual performance of the rated product, but on

the question if the CRA did everything in its power to estimate the risk of a product correctly.

To protect the CRAs from a flood of charges on daily basis is it important to put in a minimum level

from which the CRAs might be made reliable for their misbehaviour.

Reliability in the case of the CRAs is hard to define and should not be reflected in a strict percentage

as the reliability has to reflect the particular market situation, but it should be expressed in

quantitative as well as in a qualitative and long term oriented, averaged form. Each rating grade, in

each company has a definition. These definitions should be enough to enable a working system of

reliability, while it always remains partially up to the opinion of the court if a liability is charged or

dismissed against a CRA. It is also up to the court if a liability just means an impact on the score of

receiving products to rate, or if the failure is so severe that actual monetary penalties are to be

enforced.

This system would thus provide a very first step towards the introduction of a limited responsibility

for the quality of their work. It gives all issuers and investors the possibility to encourage high quality

performance by claiming liabilities and it protects the CRAs from unrealistic financial claims. A not

well performing company will receive less claims and should be further punishable by the ERF if the

performance is not improving. Similar claims about limited rating agency liability have been made by

others as well. (Dennis 2008; Bartels & Weder 2013)

The ERF also introduces systemic changes that are not implied in the system. The ERF tries to enable

a higher reliability on ratings in any economic situation and quality ratings are subject to the fact that

the issuing entities need to be obliged to inform the rating specialists, in detail, about the inner

workings of their products and disclose their model in all detail. This means that the burden of proof

needs to be shifted towards the issuer.

The other important, not yet mentioned, structural change, that fights the problem of the current

market composition is that the CRAs have the right to deny a rating. The CRAs do possess this right at

the current time, but as they are paid from the issuer if they are trapped. This might lead to not

complete independence. With the ERF they receive the right to refuse the rating, without losing

money, as the issuer needs to pay for the rating anyways, if not sufficient information is provided. If

the second CRA testing the claim that crucial information is missing agrees with the first CRA. The

rating for the particular product is denied. Such rating denial result in a temporary reapplication ban

for this particular product until all necessary information is provided. These cases of dispute between

the issuer and the CRA could be settled by the ERF.

The second step of the distribution process could look like the following. The entire process can be

pictured as two long lists. One is the list of the products in need of ratings and the other one is each

accepted claim of the CRA (𝑄𝑠𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑙). The list of products is ordered in accordance to a ratio of volume

and complexity. The ratio might be a simple calculation, for example, volume of the product times

level of complexity. The level of complexity can be a grouping process of 5 groups. Group 1 is the

lowest and least complicated category. This group would contain shares of big, well-performing and

well-established companies. Group 5 would be highly complex products like algorithmic trading

products.

The product with the highest ratio is occupying the highest position. The second list of claims is only

ordered by the CRA. The claims of the CRA with the most claims (𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛) are at the top, which is why

a bottom-up-mechanism is used. The CRA real and thus accepted claims are put in a bottom-up-

order and 1 3⁄ of all ratings will then be distributed, which means that the company with the most

14

registered claims (𝑄𝑠𝑔𝑒𝑛) will receive the products with the smallest volume and the company with

the least number of claims will be receiving the ratings for the biggest products. The model used here

helps new companies to enter the market. This highly demanding indirect entry burden will ensure

that only companies that are capable of working on the highest level of quality are able to enter the

market as a newcomer company. At the same time the mechanism is ensuring that those companies

are receiving highly profitable contract, which facilitates their development. The quality

requirements for creating a rating agency have to be highly demanding. The performance of the

agency is logically of crucial importance, as only the incentive to high quality performance can bring

the CRAs to innovate and to include not only quantitative, mass standard considerations in their

calculations, but also situation based individual considerations. The broad concept of quality work

means that a high class rating grade is not supposed to be something natural, it has to be earned and

reliable.

The remaining 2/3 of the claims will then be distributed with the help of an automated

randomization process. Such processes are hard to design, but modern programming is always

improving and exemplifying such a process would not help anyone at this point.

The ability of CRAs to adapt their number of claims to their performance situation needs to be

stopped by the introduction of an industry average that determines how many ratings one rating

specialist can conduct per day, with sufficient quality. This productivity related process can only work

with products that are really evaluated by employees and not by algorithms. So groups of products

and market situations in which it is allowed to focus on the use of these analytical tools have to be

defined in a discussion process between regulators and market players. No CRA is allowed to surpass

the industry average number of ratings per rating specialist times their rating specialists, with their

number of claims by more than 5 %. These 5 % above the average are supposed to enable a

profitable quantity for the CRAs, but it is also supposed to prevent the rating specialists from

overstressed, hasty and unreliable work.

But the ERF is not a miraculous tool that has only upsides. The incentive for growth for the CRAs

would be limited with the current design, as it is only focused on supporting smaller companies and

the incentives for high quality work are only negative pressures instead of positive incentives. If this

would be a problem for achieving the objective of these pressures remains a question, but it should

be mentioned that there is up to this point not one incentive for high quality performance that

rewards those who do perform on a high level directly.

Another crucial aspect of the ERF is the cutting of the direct connection between agencies and

financial institutions. The relation has to be minimized to guarantee the efficiency and objectivity of

the entire control system. For that reason the communication between the agencies and the issuing

entities is bound to a strictly defined protocol. Ideally the process would be anonymized as far as that

is possible, as this would minimize the influences of interpersonal relations and thus possible

personal conflicts for the involved.

The ERF would thus resolve most described market intrinsic problems and would make further

market developments like the introduction of public agencies or advanced performance

accountability easier to implement. The introduction of the ERF would completely change the CRA

market and it would improve the performance of the CRAs without hurting the mobility of the core

financial markets. It would thus be one additional stabilizing puzzle piece for the entire financial

system.

The limitations of the ERF come from several sides of the financial market. One fundamental problem

that the structure cannot tackle is an issue with derivatives. Derivatives enjoy bankruptcy privileges,

which were implemented to advance the trade with these products. These privileges enabled a

widespread of derivatives and thus an increased contagion during the development of the crisis.

15

(Bolton & Oehmke 2015; Roe 2008; Stulz 2009) The ERF is not able to interfere here, as the

bankruptcy privileges keep making derivatives, destabilizing or not, very attractive and thus higher

rated. The ERF cannot stop this possible source of contagion.

Another limitation to the objective of CRA independency is definitely the so called revolving door

effect. This process of high level employees changing numerous times between the private sector

companies and the financial market supervision entities.(Lucca et al. 2014) Even though the CRAs are

not official supervision entities can be presumed, through numerous interviews and other sources

that they are also subject to this effect. (Dennis 2008; Rügemer 2012b; Taibbi 2013)

Yet another limitation is the still existing ability for organized fraud, which means that either on the

personal or on a structural level fraud and circumvention is still possible, if criminal intention is

behind it. This is an unlikely case, but it is possible and should thus be mentioned.

The last limitation of the ERF is the fact that not only the CRAs underestimated the risk deriving from

complex products. Also the supervising entities and accountants underestimated the risk. Such a

systemic mis-interpretation of risk can also not be solved by the ERF.

5. Conclusion

The European Rating Fund is a simple but efficient adaptation for the market of the rating agencies.

Through its unavoidability for the rating agencies, it is able to change the market constellation and

eliminate most conflicting effects distorting the current market. The ERF eliminates the problematic

payment contradiction of the markets, as the entity intervenes and handles the contractual

agreement for every single product itself. The ERF also eliminates gaming behaviour and the effects

of the oligopolistic market composition as the ability for both sides to play, in a game theoretical

sense, disappears through the randomization process.

Its efficiency lies within its simple, but absolute position between the CRAs and the issuing

companies. The analysis has shown that the ERF would be efficient in improving the performance of

the CRAs. The ERF is not a bureaucratically demanding and expansive entity, but rather a

combination of slim and fast working processes, that enable a fast and consistent distribution

process, but it is not a tool that claims that all problems associated with the CRA market would be

solved by introducing the entity. Some additional reforms would be necessary like the shift of the

“burden-of-proof”. The ERF and the surrounding reforms also trigger high quality performance,

which fights the herding effect.

With regard to other reform proposals for the CRA market the ERF is the most efficient one as the

organizational structure is easy and creates no new conflicts. It fights the customization processes

within the markets, as the communication is minimized to the necessary or even anonymized. The

entity also creates no unnecessary high new costs for all entities involved and the introduction of the

ERF would free all entities in the market from distorting impacts, without limiting their business

freedom. But the ERF is no miracle tool that solves all problems that led to the financial market crisis.

The ERF is a tool that provides solid solutions for numerous problems of the CRAs. Numerous issues

with the financial markets remain and will keep distorting the CRAs as well.

This paper invites researchers, financial experts and politicians to start a discussion about a real

world implementation of a distribution platform similar to the one presented in this paper, which is

here, for the sake of the example called European Rating Fund.

As an indicator for those who might be in strong opposition to the proposed system, there has been

an introduction of a similar structure, after the last financial crisis. Central counterparty clearing

houses helped to facilitate the derivatives trade, as well as they limit the risk in over the counter

trades. These structures might work on another side of the financial markets, but their service is

structurally rather similar and might be seen as a first indication of a good performance for a

structure like the ERF.

16

To mention it once and because financial regulation is always more than a continental discussion, the

ERF could be designed as a global endeavour – and then might be called Worldwide Rating Fund,

with national subsections, but this is probably just an idealistic concept.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank my supervisors: Antonius Notermans from the Department of International

Studies and Rainer Kattel, from the Ragnar Nurkse School of Innovation and Governance of the

Tallinn University of Technology. Additionally I would like to thank Utz-Dieter Bolstorff for his critical

advice.

6. Bibliography

Afonso, A., Furceri, D. & Gomes, P., 2012. Sovereign credit ratings and financial markets linkages: Application to European data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 31(3), pp.606–638.

Akdemir, A. & Karslı, D., 2012. An assessment of Strategic Importance of Credit Rating Agencies for Companies and Organizations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, pp.1628–1639.

Archer, C.C., Biglaiser, G. & DeRouen, K., 2007. Sovereign Bonds and the “Democratic Advantage”: Does Regime Type Affect Credit Rating Agency Ratings in the Developing World? International Organization, 61(02), pp.341–365.

Arezki, R., Candelon, B. & Sy, A.N.R., 2011. Sovereign Rating News and Financial Markets Spillovers : Evidence from the European Debt Crisis. IMF Working Paper, 11(68), pp.1–27.

Bannier, C.E. & Hirsch, C.W., 2010. The economic function of credit rating agencies - What does the watchlist tell us? Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(12), pp.3037–3049.

Bartels, B. & Weder, B., 2013. A Rating Agency for Europe a Good Idea? CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP9512.

Barth, J.R., Caprio, G. & Levine, R., 2004. Bank regulation and supervision: what works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(2), pp.205–248.

BCBS, 1998. Basel Capital Accord - International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, Basel.

BCBS, 2011. Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, Available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf.

BCBS, 2006. International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, Available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf.

BCBS, 2015. Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk,

Blundell-Wignall, A. & Atkinson, P., 2009. Origins of the financial crisis and requirements for reform. Journal of Asian Economics, 20(5), pp.536–548.

Bolton, P. & Oehmke, M., 2015. Should Derivatives be Privileged in Bankruptcy ? , pp.0–51.

Brunnermeier, M. et al., 2009. The Fundamental Principles of Financial Regulation, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 11,

CFR.org, 2015. The credit rating controversy. Council of Foreign Relations. Available at:

17

http://www.cfr.org/financial-crises/credit-rating-controversy/p22328 [Accessed September 20, 2015].

Cheng, M. & Neamtiu, M., 2009. An empirical analysis of changes in credit rating properties: Timeliness, accuracy and volatility. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(1-2), pp.108–130.

Coffee, J.C.J., 2011. Ratings reform: The good, the bad and the ugly. Harvard Business Law Review, 1(231).

Crotty, J., 2009. Structural causes of the global financial crisis: A critical assessment of the “new financial architecture.” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(4 SPEC. ISS.), pp.563–580.

Dam, L. & Koetter, M., 2011. Bank bailouts, interventions, and moral hazard Lammertjan Dam Michael Koetter Discussion Paper Series 2: Banking and Financial Studies. , (10).

Dennis, K., 2008. The Ratings Game: Explaining Rating Agency Failures in the Build Up to the Financial Crisis. University of Miami Law Review, 63(1111).

Diomande, M.A., Heintz, J.S. & Pollin, R.N., 2009. Why U.S. Financial Markets Need a Public Credit Rating Agency. The Economists´ Voice, 6(6).

Duan, J.-C. & Van Laere, E., 2012. A public good approach to credit ratings – From concept to reality. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(12), pp.3239–3247.

Eijffinger, S.C.W., 2012. Rating agencies: Role and influence of their sovereign credit risk assessment in the eurozone. Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(6), pp.912–921.

Ferri, G., Liu, L.G. & Majnoni, G., 2001. The role of rating agency assessments in less developed countries: Impact of the proposed Basel guidelines,

Freeman, L., 2009. Who´s Guarding the Gate? Credit-Rating Agency Liability as “Control Person” in the Subprime Credit Crisis. Vermont Law Review, 33(585).

Gropp, R. & Richards, A., 2001. Rating agency actions and the pricing of debt and equity of European banks: what can we infer about private sector monitoring of bank soundness? Economic Notes, 30(3), pp.373–398.

Güttler, A. & Wahrenburg, M., 2007. The adjustment of credit ratings in advance of defaults. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(3), pp.751–767.

Haan, J. De & Amtenbrink, F., 2011. Credit Rating Agency,

Hill, C.A., 2011. Limits of Dodd-Frank´s Rating Agency Reform. Chapman Law Review, 15(1).

Hill, C.A., 2002. Rating Agencies Behaving Badly: The Case of Enron. Connecticut Law Review, 35.

Hill, C.A., 2010. Why Did Rating Agencies Do Such a Bad Job Rating Subprime Securities?, Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1582539 [Accessed April 27, 2015].

Ioannidou, V., 2012. A first step towards a banking union. In Banking Union for Europe - Risks and Challenges. pp. 85–95.

Jacobides, M.G., 2014. What drove the financial crisis? Structuring our historical understanding of a predictable evolutionary disaster. Business History, February(5).

Kalinowski, W., 2012. Shadow banking and the moral hazard - Principles for reducing model-based opacity in securities finance, Paris.

Kao, E.S., 2012. Moral Hazard During The Savings And Loan Crisis And The Financial Crisis Of 2008-09: Implications For Reform And The Regulation Of Systemic Risk Through Disincentive Structures

18

To Manage Firm Size And Interconnectedness. NYU Annual Survey Of American Law, 67, pp.817–860.

Kraft, P., 2011. Rating Agency Adjustments to GAAP Financial Statements and Their Effect on Ratings and Bond Yields,

Kuhner, C., 2001. Financial Rating Agencies: Are they credible? - Insights into the reporting incentives of rating agencies in times of enhanced systemic risk. Schmalenbach Business Review, 53(January), pp.2–26.

Longstaff, F. a., 2010. The subprime credit crisis and contagion in financial markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 97(3), pp.436–450.

Lucca, D., Seru, A. & Trebbi, F., 2014. The revolving door and worker flows in banking regulation. Journal of Monetary Economics, (678).

Lütz, S., 2002. Der Staat und die Globalisierung von Finanzmärkten: Regulative Politik in Deutschland, Großbritannien und den USA, Frankfurt am Main/ New York: Campus Verlag.

MacKenzie, D., 2014. A Sociology of Algorithms: High-Frequency Trading and the Shaping of Markets,

Manns, J., 2009. Rating risk after the subprime mortgage crisis: a user fee approach for rating agency accountability. North Carolina Law Review, 87, pp.1011–1090.

Mathis, J., McAndrews, J. & Rochet, J.-C., 2009. Rating the raters: Are reputation concerns powerful enough to discipline rating agencies? Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(5), pp.657–674.

Mizen, P., 2008. The credit crunch of 2007-2008: A discussion of the background, market reactions, and policy responses. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 90(5), pp.531–567.

Moshirian, F., 2011. The global financial crisis and the evolution of markets, institutions and regulation. Journal of Banking and Finance, 35(3), pp.502–511.

Norden, L. & Weber, M., 2004. Informational efficiency of credit default swap and stock markets: The impact of credit rating announcements. Journal of Banking and Finance, 28(11), pp.2813–2843.

Notermans, T., 2013. Reforming Finance; A Literature Review. FESSUD, Financialisation, Economy, Society and Sustainable Developement, 8, pp.1–91. Available at: http://ideas.repec.org/p/fes/wpaper/wpaper08.html [Accessed November 11, 2014].

Purda, L.D., 2007. Surprise Rating Changes. , XXX(2), pp.301–320.

Reinhart, C. & Rogoff, K., 2014. This time is different: A panoramic view of eight centuries of financial crises. The Annals of Economics and Finance.

Roe, M.J., 2008. The Derivatives Market´s Payment Priorities as Financial Crisis Accelerator. , 539, pp.221–273.

Roubini, N., 2008. how will financial institutions make money now that the securitization food chain is broken? economonitor.com. Available at: http://www.economonitor.com/nouriel/2008/05/19/how-will-financial-institutions-make-money-now-that-the-securitization-food-chain-is-broken/ [Accessed October 22, 2015].

Rügemer, W., 2012a. Rating Agenturen - Einblicke in die Kapitalmacht der Gegenwart 2nd ed., Bielefeld: transcript XTEXTE.

Rügemer, W., 2012b. Rating Agenturen Einblicke in die Kapitalmacht der Gegenwart, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Schroeder, S., 2013. A Template for a Public Rating Agency. Journal of Economic Issues, 47(2),

19

pp.343–350.

Schwarcz, S.L., 2002. Private Ordering of Public Markets: The Rating Agency Paradox. University of Illinois Law Review, 1.

Sinclair, T.J., 2008. The new masters of capital: American bond rating agencies and the politics of creditworthiness, Cornell University Press.

Skreta, V. & Veldkamp, L., 2009. Ratings Shopping and Asset Complexity: A Theory of Ratings Inflation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 56(5), pp.696–699. Available at: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304393209000622.

Stolper, A., 2009. Regulation of credit rating agencies. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(7), pp.1266–1273.

Stulz, R.M., 2009. Financial Derivatives: Lessons From the Subprime Crisis. The Milken Institute Review, First Quar, pp.58–70.

Sy, A.N.R., 2004. Rating the rating agencies: Anticipating currency crises or debt crises? Journal of Banking and Finance, 28(11), pp.2845–2867.

Taibbi, M., 2013. The Last Mystery of the Financial Crisis. Rolling Stone. Available at: http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-last-mystery-of-the-financial-crisis-20130619 [Accessed September 23, 2015].

Tichy, G., 2011. Credit rating agencies: Part of the solution or part of the problem? Intereconomics, 46(5), pp.232–262.

Utzig, S., 2010. The Financial Crisis and the Regulation Banking Perspective Asian Development Bank Institute. Social Science Research Network, (188), pp.1–26.

Véron, N., 2011. What Can and Cannot Be Done about Rating Agencies. Policy Briefs, 21(November), pp.1–8.

Welfens, P.J.J., 2010. Transatlantic banking crisis: Analysis, rating, policy issues. International Economics and Economic Policy, 7(1), pp.3–48.

White, L.J., 2010. The Credit Rating Agencies. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(2), pp.211–226.

White, L.J., 2009. The credit-rating agencies and the subprime debacle. Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society, 21(2-3), pp.389–399.

Xia, H. & Strobl, G., 2012. The issuer-pays rating model and ratings inflation: Evidence from corporate credit ratings. Available at SSRN 2002186, (May), p.43. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2002186.

Adrian, T. & Shin, H.S., 2009. The Shadow Banking System: Implications for Financial Regulation, New York.

Afonso, A., Furceri, D. & Gomes, P., 2012. Sovereign credit ratings and financial markets linkages: Application to European data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 31(3), pp.606–638.

Akdemir, A. & Karslı, D., 2012. An assessment of Strategic Importance of Credit Rating Agencies for Companies and Organizations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58, pp.1628–1639.

Archer, C.C., Biglaiser, G. & DeRouen, K., 2007. Sovereign Bonds and the “Democratic Advantage”: Does Regime Type Affect Credit Rating Agency Ratings in the Developing World? International Organization, 61(02), pp.341–365.

20

Arezki, R., Candelon, B. & Sy, A.N.R., 2011. Sovereign Rating News and Financial Markets Spillovers : Evidence from the European Debt Crisis. IMF Working Paper, 11(68), pp.1–27.

Bannier, C.E. & Hirsch, C.W., 2010. The economic function of credit rating agencies - What does the watchlist tell us? Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(12), pp.3037–3049.

Bartels, B. & Weder, B., 2013. A Rating Agency for Europe a Good Idea? CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP9512.

Barth, J.R., Caprio, G. & Levine, R., 2004. Bank regulation and supervision: what works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13(2), pp.205–248.

BCBS, 1998. Basel Capital Accord - International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, Basel.

BCBS, 2011. Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems, Available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf.

BCBS, 2006. International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards, Available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf.

BCBS, 2015. Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk,

Blundell-Wignall, A. & Atkinson, P., 2009. Origins of the financial crisis and requirements for reform. Journal of Asian Economics, 20(5), pp.536–548.

Bolton, P. & Oehmke, M., 2015. Should Derivatives be Privileged in Bankruptcy ? , pp.0–51.

Brunnermeier, M. et al., 2009. The Fundamental Principles of Financial Regulation, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 11,

CFR.org, 2015. The credit rating controversy. Council of Foreign Relations. Available at: http://www.cfr.org/financial-crises/credit-rating-controversy/p22328 [Accessed September 20, 2015].

Cheng, M. & Neamtiu, M., 2009. An empirical analysis of changes in credit rating properties: Timeliness, accuracy and volatility. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 47(1-2), pp.108–130.

Coffee, J.C.J., 2011. Ratings reform: The good, the bad and the ugly. Harvard Business Law Review, 1(231).