The Enduring Power of Isolationism: An Historical Perspective

-

Upload

christopher-mcknight -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of The Enduring Power of Isolationism: An Historical Perspective

Summer 2013 | 390

NICHOLS

The Enduring Power of Isolationism An Historical Perspective

May 11, 2013 By Christopher McKnight Nichols Christopher McKnight Nichols is Assistant Professor of History at Oregon State University. His most recent book is Promise and Peril: America at the Dawn of a Global Age (Harvard University Press, 2011). This article is a revised version of a paper he delivered at FPRI’s Study Group on America and the West.

Abstract: Are Americans becoming more “isolationist”? Four years ago, for the first time since the Vietnam War, almost half of those polled by the Pew Research Center stated they would rather the United States “mind [its] own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own” and work to “reduce military commitments overseas” in order to decrease the deficit. Such cautious views about American involvement abroad are on the rise, up ten percentage points over the past decade, according to Pew polls released in 2011 and 2012. A majority of Americans think the United States is withdrawing from Afghanistan too slowly and are reticent to take direct action in Syria. This article explains the long historical context of these recent events to argue for the enduring power and significance of isolationist thought.

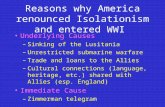

raditionally, Americans who opposed the restrictions on national sovereignty imposed by entering into global agreements, permanent alliances, and interventions in foreign conflicts have advocated for political isolationism. In

the 1920s and 1930s—at the peak of such arguments—isolationist advocates such as the so-called “irreconcilable” Idaho Republican Senator William Borah and his colleague Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota heralded George Washington’s call for freedom from “permanent alliances” and “foreign entanglements.” But even as they rejected most forms of international organizations and binding treaties, Borah and Nye did not call for complete cultural, commercial, or political separation from the world.

Later, during the run-up to the 1952 presidential campaign, Democrat Adlai Stevenson famously pitted the isolationist “ostrich” against the internationalist “eagle.” He warned of the “challenge of a new isolationism.” In particular, Stevenson worried about the challenge presented by Republican Senator and GOP presidential candidate Robert Taft, who, in the tradition of Borah, advocated the

T

doi: 10.1016/j.orbis.2013.05.006

© 2013 Published for the Foreign Policy Research Institute by Elsevier Ltd.

:

Summer 2013 | 391

American Isolationism

doctrine of the “free hand” and urged the nation to spurn the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and strictly limit its commitments to Western Europe and the world.1

Today, America appears to be confronted by a similar set of challenges. Whatever one thinks about U.S. worldwide commitments, one cannot doubt the continuing power of the word “isolationism” and the appeal of many concomitant ideas in our national dialogue. Given that more than three-fourths of Americans approve of President Barack Obama’s decision to pull troops out of Iraq, most are eager to be out of Afghanistan and not involved directly in Syria, and 70 percent reject further U.S. efforts to promote democracy abroad, the interventionism of the Bush era is clearly unpopular. The U.S. is unlikely to return to that approach anytime soon, although the emergence of a drone strategy belies facile assertions that there has been an unambiguous shift away from unilateral modes of engagement.2

The current reassessment of the nation’s proper balance for the twenty-first century between engagement abroad and investment at home is just the latest reappraisal of a long-standing conundrum. Since the United States’ rise to global power, its leaders and citizens have scrutinized the costs and benefits of foreign ambition. In 1943, in the midst of World War II, Walter Lippmann explained the essential paradox involved in this delicate balancing act. He argued that the relationship between means and ends is the critical question for policymakers. “In foreign relations,” he wrote, “as in all other relations, a policy has been formed only when commitments and power have been brought into balance. . . . The nation must maintain its objectives and its power in equilibrium, its purposes within its means and its means equal to its purposes.”3

Historians and political scientists have analyzed thoroughly America’s rise to global power and the debates over how to achieve the right balance between domestic and foreign affairs. Yet the conventional wisdom that the isolationist tradition amounts to atavism, that it has had little historical impact, or that it has no relevance today is inadequate. What has been missing in many recent historical narratives has been a unified account of changing intellectual understandings of isolationism, as viewpoints have varied from the 1890s to the present.

Several excellent older histories of isolationism also miss elements of this intellectual transition because they almost exclusively emphasize diplomacy and political behavior with a focus on two periods. The first encompasses the turbulent years from 1914 through 1920, culminating in the Senate’s rejection of the Treaty of

1Adlai Stevenson, “The Challenge of a New Isolationism,” New York Times, Nov. 6, 1949; Robert A. Taft, A Foreign Policy for Americans (New York: Doubleday, 1951). 2 “Americans' Views on Foreign Policy Issues and Assessment of Republican Candidates,” CBS News Polling Unit, (2011) accessed April 3, 2013, see: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-250_162-57323535/cbs-news-polls-11-11-11/; Micah Zenko, “Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies,” Council on Foreign Relations Special Report 65 (January 2013); on drone strategies see the reporting of Jeremy Scahill, Mark Mazzetti, and Steve Coll. 3 Walter Lippmann, U. S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1943), p. 7.

392 | Orbis

NICHOLS

Versailles and the League of Nations. The second era—and the best explored—is the so-called “battle against isolation” and the neutrality debates centered in the decade from 1930 until the outbreak of World War II. The foremost foreign policy histories of these periods were written and researched mainly in the 1950s and 1960s. They have tended to explore ideas about isolation using traditional methods of political history and the study of foreign relations.

The origins of the isolationist positions for both of these later periods have been largely unexamined. In my work, I explore how those views can be traced back to the 1880s and 1890s and particularly to the debates over empire before and after the Spanish-American War, as intellectual and cultural phenomena. By juxtaposing their development with emerging visions of internationalism and domestic reform, we can better perceive just how pivotal ideas about isolation were to a wide range of new perspectives on the meaning of America in an age of rising global power from the nineteenth century through World War II.4

So, let us take a look back at the trajectory of isolationism and internationalism over the past 130 years, bringing the narrative up to the present, to gain a sense of where the United States has been and where it may be headed.

From the 1890s to the 1920s

At no time were isolationist principles more potent than during the period when America rose to global power from the late nineteenth century through the period after WWI. Isolationism never dominated U.S. policy during this era, yet it was a crucial component first in the debates over empire, in setting the terms for domestic social reform, in the dissent over entering World War I, and subsequently in the backlash against the war and the rise of a new internationalism. Isolation, non-intervention, anti-colonialism, and avoidance of war are primordial American concepts. Yet such values have been far from static. From Democratic President Grover Cleveland to Massachusetts Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to Harvard philosopher-psychologist William James, politicians and intellectuals built differing political philosophies on the firm foundations that they interpreted as having been established by Washington, Jefferson and Monroe. “The genius of our institutions,” said Cleveland, “the needs of our people in their home life, and the attention which is demanded for the settlement and development of the resources of our vast territory dictate the scrupulous avoidance of any departure from that foreign policy commended by the history, the traditions, and the prosperity of our Republic.” Cleveland went on to define such politics as focused inwardly on domestic economic and political progress. He saw these changes as best supported

4 For excellent political and diplomatic scholarship on isolationism in America for the period 1914-1917, see Ernest May’s The World War and American Isolation, 1914-1917 (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1966), and John Milton Cooper, Jr.’s The Vanity of Power: American Isolationism and the First World War, 1914-1917 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1969).

Summer 2013 | 393

American Isolationism

by a stance of “neutrality, rejecting any share in foreign broils and ambitions upon other continents and repelling their intrusions here.”5

These words come from Cleveland’s first inaugural address in 1885. That he invoked three iconic Founding Fathers should come as no surprise. Yet Cleveland also realized that the definition of frontiers and interdependence was changing rapidly. The words “isolation” and “isolated” come up often in this discourse as an objective for American policy—not to keep the United States out of the world but to keep the world’s politics from infecting the nation, or drawing the nation into conflicts not in the “national interest.” Cleveland believed America’s “traditional” policy had to be updated in non-interventionist formulations that could meet the new challenges posed by an industrial society and the nation’s burgeoning global commercial and military power.

For some, such as Lodge, the reserved Boston Brahmin and conservative Republican, this meant reorienting older views of national isolation to help justify international expansion. It is ironic that Lodge is best remembered for spearheading the Senate Republican “reservationists” who opposed the Treaty of Versailles and American membership in the League of Nations from 1918 to 1921. Due to his powerful isolationist-nationalist argument that the covenant threatened American sovereignty, his opponents in those debates cast him as an inveterate isolationist. Yet from the beginning, Lodge held simultaneously to a supposedly fixed historical conception and to a contingent view of traditional isolationism.

In his 1889 biography of George Washington, for example, Lodge wrote, Our present relations with foreign nations fill as a rule but a slight place in American politics, and excite generally only a languid interest, not nearly so much as their importance deserves. We have separated ourselves so completely from the affairs of other people that it is difficult to realize how commanding and disproportionate a place they occupied when the government was founded.6

In this, one of his most quoted early assessments of foreign policy, Lodge exulted in America’s invulnerability to European influence and argued for the continued importance of maintaining a distant relationship. This invocation, however, ignores Lodge’s expansionist beliefs.7 Along with other advocates of the “large policy,” including Theodore Roosevelt, naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, and Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge, Lodge had to resort to intellectual gymnastics to reconcile expansionism with traditional isolation. Lodge epitomized the twin elements of this progression: he developed a coherent new rationale for foreign expansionism as an extension of the westward expansion across the continent. We see this most clearly in the two rounds of debates over the annexation of Hawaii (early and late 1890s), in 5 Grover Cleveland, March 4, 1885, in James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the presidents, 1789-1902 (Washington, D.C.: Published by authority of the Bureau of National Literature and Art, 1903), p. 301. 6 Henry Cabot Lodge, The Life of George Washington (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, rept. 1920, orig.1889), p. 131. 7 Lodge to John T. Morse, Jr., May 6, 1889. Lodge Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

394 | Orbis

NICHOLS

the dispute with Great Britain over U.S. protection of Venezuela’s boundary (1895-1896), and in the Spanish-American War (1898) and Philippine War (1899-1902). In his reassessment of isolation in light of modern realities, Lodge was concerned particularly with expanding and deepening an assertive, unilateral interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine as he worked to lead the nation into war and new territorial expansion, with considerable unexpected consequences.

Swayed by this viewpoint, U.S. policymakers proceeded to make small annexations, new commercial engagements and various development projects, providing the nation with new outposts in the Caribbean and in the Pacific, along with an intercontinental canal to secure. This new territory provided fresh rationales for increased interaction abroad. It also heightened both connections and tensions with nations and peoples involved in those areas, making the United States simultaneously more global and more vulnerable.

To oppose the expansionists, a broad, heterogeneous group of Americans came together at the turn of the twentieth century. This group included William James, the racial reformer W.E.B. Du Bois, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, writer Mark Twain, Massachusetts Senator George Frisbie Hoar, and settlement house activist Jane Addams, among others. Unifying their outlooks was the growing sense that they lived in a period of transition when the social revolution propelled by industrialization had fundamentally altered the framework of society. New circumstances, these anti-imperialists said, demanded a modern view of the nation’s complex relations with the rest of the world. Yet opponents of empire, like James, wanted to preserve long-standing principles in foreign affairs—most notably steering clear of foreign entanglements—and anti-colonial concepts, such as not ruling alien peoples against their will. They also were wary of the ways in which special interests, particularly big business, subtly shaped U.S. foreign policies that ultimately served to promote interventionism.

In many ways, their critique represented a transition in ideals that paralleled the “large policy” interpretation of America’s isolationist traditions. James observed that while bellicosity is a natural instinct, it can be contained. He argued that this was done best when “aggressive” humans sublimated their inner drives toward “moral weight” rather than into “savage ambition.”8 While “large policy” advocates posited the expansionist turn outward as a solution to internal problems, anti-imperialists sought to turn inward to find solutions to pressing domestic concerns rather than attempt costly imperial excursions abroad.

Locating the origins of modern isolationism in these debates over empire during the 1880s and 1890s, a generation earlier than most historians, enables us to understand that isolationist ideas were central in shaping the broader debates in which Americans conceived how their nation ought to act in the world.

The United States never became a major colonial power, nor did the nation take the initiative to establish strong international leadership after World War I. As

8 James to François Pillon, June 15, 1898, James Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Summer 2013 | 395

American Isolationism

America ascended to the status of a world power during the 50 years from the 1880s through the 1930s, imperialist, interventionist, and internationalist impulses intensified. During the 1890s and in the World War I era, neither these worldviews—nor Wilson’s idealistic perspective—were able to resist the powerful pull of enduring, popular isolationist sentiments. That is because newer iterations of isolationist thought evolved so that they were compatible with measured global involvement.

These interrelated views about isolation and internationalism gained acceptance as part of a sophisticated framework for defining both national ideals and global imperatives. In part this explains the many variations on isolationist thought while also demonstrating some of the most salient underlying consistencies. The isolationist perspective was far from monolithic. Ideas about isolation, in light of the changing conditions of modern industrial society and ever-increasing global interconnections between nations and peoples, were elemental across a wide spectrum of political thought.

Shared values emerged as integral to the development of isolationist thought. Most prominent among these were an unyielding interpretation of America’s democratic guiding principles, as well as an updated view of the nation’s vital interests. This view emphasized the pursuit of peace, but also the preservation of freedom of action by combining commercial international engagement with neutrality. The concept of neutrality as it developed in the early 1900s was quite fungible indeed.

These core focuses of refined isolationism developed early on in anti-imperialist thought, notably as formulated by William James. In turn these ideas quickly influenced the views of anti-imperial, anti-interventionist reformers such as Du Bois, Addams and Randolph Bourne (who coined the concept of the United States as a “transnational nation”). These notions surfaced to persuasively inform and connect the arguments of isolationist William Borah with those of international pacifist Emily Balch.

At the same time, Henry Cabot Lodge adhered to some similar long-standing principles of isolationist autonomism as Borah, with its heavy reliance on placing national autonomy at the center of evaluations of foreign policy, and interpreting them in terms of a robust sense of nationalism. This position formed the core of Lodge’s muscular “large policy” expansionism in the 1890s. Thus his early politics were united with his later strident isolationist-nationalist position in the League of Nations debates. A similar vision of isolationist national interest set within an exceptionalist framework also appeared in the arguments of Christian evangelizers and mission advocates, such as YMCA ecumenical leader John Mott. He worked with government but preferred non-governmental outreach, and also shaped the unilaterally nationalist positions advanced by William Borah and the Irreconcilables.

The expansion of American empire in the late nineteenth century was followed by retrenchment from imperialism. This lull, marked by a predominant concern with domestic social reform, was short-lived. New global changes spurred further refinement of isolationist principles. A series of debates began, leading

396 | Orbis

NICHOLS

eventually to intervention, war, and then a significant backlash during World War I, making isolation far more appealing in the post-war period.

The war in Europe reshaped isolationist views of how the nation might best engage abroad. The transformative effects of war both on ideas and society in America are well established. However, the reconciliation of modern isolationism with the new internationalist and transnationalist positions is less familiar. Premised on hopes for peace, anti-war activists came together with an array of radical politicians and social critics from 1914 to 1917. Though they were a small minority and did not prevent entry into the conflict, their criticism echoed during the interwar years, when opposition to interventionism held significant sway, and the movement to outlaw war gained momentum.

In November 1919, in a flourish of oratory directed against congressional ratification of the League charter, Borah said, “But your treaty does not mean peace—far, very far, from it. If we are to judge the future by the past it means war.” In the Senate chambers, he then turned to the gallery and rhetorically questioned the audience. “Is there,” he asked, “any guaranty of peace other than the guaranty which comes of the control of the war-making power by the people?”9

In Borah’s view, the League dispute revolved largely around preserving national autonomy, especially having to deploy force to defend member nations under the terms of Article X of the League Covenant. In the wake of the election of 1920, the course he and the Irreconcilables had helped to steer, along with Lodge, was what they believed citizens wanted. Borah said the resounding Republican victories, coupled with the rejection of the League, were “the judgment of the American people against any political alliance or combination. The United States had rededicated itself to the foreign policy of George Washington and James Monroe, undiluted and unemasculated.”10

These visions of a “new isolationism” were actually a flexible quasi-populist and nationalist form of politics. The burgeoning appeal of a new form of isolation appeared in the advocacy of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, in parts of Jane Addams and Emily Balch’s “new internationalism,” and in the broader U.S. peace movement.. This internationalist-isolationist framework —always in tension, never fully resolved—forms the background of how Americans today debate the “proper” role of the nation in the world.

The 1920s through World War II

During the interwar years, isolation crystallized into a more coherent

ideology and briefly assumed a positive cast in American politics. The Kellogg-Briand Pact to outlaw war in 1928, championed by Borah and Balch, represented a rare moment of unity between isolationists and internationalists. This also signaled

9 William Borah, “On the League of Nations,” Congressional Record (November 1919). 10 Quoted in Thomas Guinsberg, The Pursuit of Isolationism in the United States Senate from Versailles to Pearl Harbor (New York: Garland, 1982), p. 52.

Summer 2013 | 397

American Isolationism

the era’s new possibilities for fusing isolation with international imperatives. Ultimately, Woodrow Wilson’s vision for a world order based upon a partial but genuine relinquishment of sovereignty by even the most powerful nations was more radical than any plan seriously pursued by policymakers before or since. In America, it was rebuked precisely because it turned away from long-standing views that the country should be free from the corrupting influences of foreign politics. Still, during the 1920s and 1930s, the Wilsonian view was not entirely discarded. A significant idealistic rhetoric remained. A dynamic conceptual mix, it combined the new political isolationism with largely open engagement in commercial and cultural arenas, becoming ever more prominent throughout American thought and politics.

Borah’s support of outlawing war was part of his isolationist program. As historian Robert Johnson has shown, virtually the entire peace bloc in Congress and the vast majority of the American population strongly supported the pact despite having significant concerns about its effectiveness. Johnson has found that isolationist anti-war thought was part of a broader effort to find an “alternative to corporatism,” noting that “the peace progressives who favored Kellogg-Briand argued that the treaty embraced anti-imperialism.”11

Seen in this light, the movement to outlaw war echoed William James and the anti-imperial isolationist views of several decades earlier. So, too, did Borah’s assessment in the late 1920s that the Kellogg-Briand Pact might at least rectify the problem of reconciling the status of strong and weak states and shelter dependent regions from colonial excesses and conflicts, an older anti-imperialist argument.12 Those favoring the Pact emphasized a unilateral and generally neutral form of nationalism to complement this anti-imperialism. They argued for moral and economic suasion abroad and once again emphasized the commercial and agricultural base, and disarmament, at home. These positions led Borah and his allies to aim for protection of domestic agrarian interests, even burgeoning agro-business, by raising the tariff. Like Lodge and many imperialists of the 1890s, they also firmly supported immigration restriction.13

Hindsight reveals that these developments during the “interwar years” can be characterized best as a midway point between the prewar period—when a domestic focus precluded international interest, particularly in terms of binding entanglements with Europe—and a global, idealistic, even messianic role as championed by Wilson-style internationalists. One scholar has aptly termed this compromise position for the 1920s as a “new isolationism,” marked by economic, cultural, and limited political participation abroad.14 Borah and other politicians, Balch and other activists, sought to make the United States a leading force in the

11 Robert Johnson, The Peace Progressives and American Foreign Relations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 178. 12 For more on this in terms of “peace progressivism,” see Johnson, The Peace Progressives, esp. p. 178. 13 Borah, Congressional Record, 70th Congress, 1st session, 2011, and 2nd session, pp. 1064-66. 14 See Selig Adler, The Isolationist Impulse, on the “new isolationism.” Adler made a similar argument regarding American foreign policy between the wars in The Uncertain Giant, 1921-1941 (New York: MacMillan Company, 1965).

398 | Orbis

NICHOLS

campaign to outlaw war. Even with all of this engagement, however, a nationalist, inward perspective that refused to make large or binding overseas commitments dominated the era. Well into the 1930s, there was little sense that such perspectives would precipitate another world war. If anything, they were envisioned to prevent the period from ever being termed “interwar.”

Late in his career, Borah famously remarked that the United States had not changed a great deal since the days of Washington, Jefferson and Monroe. What had changed, he said, was that with its rise to global power, America had to be more circumspect when employing that power, relying on authority rather than aggression. From 1929 through 1934, long-standing undercurrents of protectionist isolationism emerged in the form of increased tariffs and often short-sighted inward-focused economic policies precipitated by the Depression. After 1934, beginning with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, tariff policy finally moderated and the United States moved gradually back toward free trade.

By the 1930s Borah’s fusion of freedom and autonomy into an internationally engaged, belligerent type of isolationism had gained wide influence. Yet Borah deemed it perfectly appropriate to have both multilateral and unilateral economic and trade bills. This was as long as they were not permanent and that they protected the average American worker. A distinction must be made between more aggressive isolationists, such as Borah and Hamilton Fish, Jr., who called for full neutral trading rights, and more cautious isolationists such as Nye and Arthur Vandenberg, who were willing to forgo even traditional neutral trading rights in global commerce to prevent war.

Given limited resources, “why stand abroad when we can stand at home,” Borah asked rhetorically, paraphrasing Washington. This perspective found widespread support across a vast swath of American society after the war, when an inward focus seemed essential to ensure progress, and then, during the Depression, to mitigate domestic conditions. Such arguments also resonated across political lines, even finding strange alliances with socialist internationalists such as Norman Thomas, who followed in the footsteps of socialist leader and five-time presidential candidate Eugene Debs. Nye supported Borah’s position against the overreach of business interests on similar grounds.

In a series of hearings and reports from 1934 to 1936, a commission chaired by Nye popularized and added official support to this anti-corporate/anti-special commercial interests interpretation of the causes of war. This commission issued a scathing final report attacking American pro-war business interests, such as J.P. Morgan and the Du Pont Company. In addition to the old critique that special interests and elites had forced the common man and the nation into war against the nation’s interests, the commission alleged a more direct profit motive: the financial industry and so-called “merchants of death” made immense sums from 1914 through World War I.15 The Nye Commission’s well-publicized report summarized

15 Report of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry (The Nye Report), U.S. Congress, Senate, 74th Congress, 2nd sess., (Feb. 24, 1936), pp. 3-13.

Summer 2013 | 399

American Isolationism

this point succinctly, stating: “The committee finds, under the head of the effect of armament, on peace, that some of the munitions companies have occasionally had opportunities to intensify the fears of people for their neighbors and have used them to their own profit.”16 The Neutrality Acts of 1935, 1936, and 1937 helped to solidify this position politically. The time had come, many argued, for America to concentrate its focus inward, to stop worrying about world events, and to bind the hands of the president and special interests to pull the nation into imbroglios abroad.

The resulting new interpretation of the political and legal regime of neutrality was significant because it employed an innovative stratagem: to block future paths to war it reversed even the traditional Washingtonian view on neutral rights and embargoed all arms and war materiel trade with belligerents, insisting that Americans who traveled on the ships of belligerents did so at their own peril. Building on this legislative reasoning, the key was not to insist on traditional or expended neutral rights (a la Wilson), but to resist them, as had not been done in 1914-17.

The Spanish Civil War served as a test case for the stringent neutrality position. A Gallup Poll in 1937 found that 66 percent of Americans “had no opinion on events in Spain.”17 Debates over whether to wrest control of war-making power from the president and Congress fed this anti-war, anti-elite, isolationist sentiment. These views led to a renewed effort for a Constitutional amendment, as proposed by Louis Ludlow and only narrowly defeated in 1938, to make the decision to enter war a referendum put to a public vote. Intellectuals, such as historians Charles Beard and Charles Tansill, lent scholarly prestige and even historical heft to these vigorous positions.18

Borah, the bloc of irreconcilables, Balch, Addams, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and other peace organizations, found common ground when they worked together to push for an American-led international movement to outlaw war and for more forceful neutrality.

These developments made the period of the mid-1930s a “high water mark” of American isolationist thought.19 Yet it is important to recognize that the oscillations of the two decades before World War II hearkened back to the parameters established in the anti-imperialist debates of the 1890s. Because the reputation of American business interests reached its nadir during the Depression, 16 Ibid, Report of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, pp. 3-13. 17 Gallup Poll 1937, on this poll in near-contemporary perspective, Philip E. Jacob, “Influences of World Events on U.S. ‘Neutrality’ Opinion,” The Public Opinion Quarterly, Mar. 1940, pp. 48-65, see also David Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 398-399. 18On Nye’s anti-big business views and neutral rights as foreign policy, see Wayne Cole, Senator Gerald Nye and American Foreign Relations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962); regarding the crystallizing isolationist political positions of the 1930s see Jonas, Isolationism in America, 1935-1941, ch. 1, “The Isolationism of the Thirties.” On the “calm before the storm” and the “isolationist tornado” of the 1930s, see also Adler, The Isolationist Impulse, pp. 218-274. 19For examples see Manfred Jonas, Wayne Cole, and Selig Adler, to name a few.

400 | Orbis

NICHOLS

the debates of the period centered on how to restrain the globally interconnected nature of modern commercial forces. That is, the goal of the 1930s neutrality and related acts was premised on distrust and circumspection. Isolationists like Borah aimed to manage and inhibit “bigness” in political leagues, as well as in economic combinations.

As war broke out across the world, many Americans struggled hard to keep the nation out of all foreign conflicts, including not fighting for or aiding those at war with the Axis powers. Briefly in 1940 the most extreme form of anti-war isolationism allied Gerald Nye and Norman Thomas with Charles Lindbergh and General Robert Wood under the banner of the America First Committee (AFC).

The AFC included a diverse set of intellectuals and public figures, including Lindbergh, Walt Disney, Sinclair Lewis, e.e. cummings, and Alice Roosevelt Longworth. The AFC was one of the largest foreign policy lobby organizations ever formed in the United States. Akin to the Anti-Imperialist League, the AFC was heterogeneous in its membership and fell back on arguments based on American foreign policy traditions. In speeches, pamphlets, and other advocacy AFC leaders consistently argued that the U.S. should remain entirely neutral in words and deeds; that aid to allies “short of war” only weakened America; and that no foreign nation would attack America if the nation pursued a robust preparedness plan of coastal defenses and air power. They made a powerful appeal to an insular, nationalistic type of exceptionalism and xenophobia. They cast the twin menaces of American globalism and interventionism as far worse than that posed by Nazism in Germany, fascism in Italy, or militarism in Japan.

Polls as late as November 1941 indicated that most Americans did not support a declaration of war. The 1941 Atlantic Charter, which extended and formalized an Anglo-American set of “war and peace aims” in opposition to Nazism, well before the U.S. officially entered the war, represented an effort to reject AFC-type isolation. Buttressed by Roosevelt’s powerful articulation of “Four Freedoms” and informed by the legacies of World War I, it was an effort, as one scholar put it, to “redefine human rights” as essential to America’s vision of a “New Deal for the World.”20 Roosevelt had slowly maneuvered the nation into tacit alliance with England by 1941, but not until Pearl Harbor was the potent opposition to formally entering the war ended and the AFC discredited. The xenophobic isolationism espoused by the AFC, most memorably embodied in Lindbergh’s anti-Semitism, irrevocably tarnished the viability of a coherent isolationist politics along with the term “isolationism” itself.

Balch’s humanitarian internationalism naturally led her to support Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms as a global policy. Eventually relinquishing her heartfelt commitment to pacifism in the face of Axis atrocities, Balch publicly supported American entry into World War II to “save humanity,” as she put it. For her

20 Elizabeth Borgwardt, A New Deal for the World: America's Vision for Human Rights (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), on the Atlantic charter, introduction, on the legacy of Wilson, ch. 1.

Summer 2013 | 401

American Isolationism

willingness to engage with other countries in the search for peace, she was accorded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946.21

Isolation in the Wake of World War II

After the war, the United States embarked on a series of global initiatives that deeply influenced how Americans viewed their nation’s international role and its relationship to domestic politics. Isolation as a national value remained a subject of debate but took on increasingly negative characteristics. It appeared severely outdated.

In many ways the attack on the “homeland” of Pearl Harbor had sounded the death knell of isolationism for a globalized world. Yet it did not end the arguments for limited, temporary engagement abroad. The steps taken in these years would have been unthinkable ten years earlier. Rather than repeat the refusal to join the League of Nations, the United States helped to create the United Nations and even located its headquarters on American soil. To ensure a lasting peace the U.S. orchestrated plans of economic integration, highlighted by reconstruction efforts such as the Marshall Plan. Instead of eschewing permanent commitments, the United States unilaterally established the first major peacetime alliance in its history, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). At home, the army demobilized in part but never in full, and the American military-industrial complex was born.22

Even as the postwar Republican party of John Dewey and Dwight Eisenhower embraced a new Cold War model of muscular internationalism, a few staunch isolationists remained. One of the most notable was the son of President William Taft, Senator Robert Taft from Ohio. He argued throughout the early 1950s against joining NATO. Yet, he accepted a policy of tacit support for allies, rather than a binding alliance-based system, if attacked by Russia. He sought enhanced commerce and new markets abroad yet advocated protective tariffs and more modest federal expenditures at home. His view represented the modern isolationist

21On the America First Committee, see Wayne Cole, America First; The Battle Against Intervention, 1940-1941 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1953). The AFC’s “battle against intervention” contrasts poignantly with Emily Balch’s battle against her own pacifist inclinations in her book Beyond Nationalism. 22For an exemplary brief debate on isolationism from 1944 see: Raymond Dennett, “Isolationism is Dead,” Far Eastern Survey, July 26, 1944, pp. 135-137, and Benjamin H. Kizer, “Isolationism is Not Dead,” Far Eastern Survey, August 23, 1944, pp. 155-156. Here I draw on the post-war progression often invoking international human rights language to push for domestic social justice rather than engagement abroad, see Hugh H. Smythe, “The N.A.A.C.P. Protest to UN,” Phylon (4th Qtr., 1947), pp. 355-358. On the debates over the U.N. “neo”/“new” isolationism came to be seen as a threat. See Cabell Phillips, “New Isolationism Endangers ‘Marshall Plan,’” New York Times, July 20, 1947; Adlai Stevenson, “The Challenge of a New Isolationism,” New York Times, Nov. 6, 1949; Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “The New Isolationism,” The Atlantic Monthly, May 1952, p. 189; Paul H. Douglas, “A New Isolationism—Ripples or Tide?” New York Times, Aug.18, 1957; Norman Graebner, The New Isolationism: A Study in Politics and Foreign Policy Since 1950 (New York: Ronald Press, 1956).

402 | Orbis

NICHOLS

formulation of weighing limited options and avoiding long-term entanglements while seeking heightened commercial and cultural interchange, a model dating back 50 years before in the debates over empire. Taft, however, added a heightened level of defensive preparedness keyed in to the strategic concerns of the early Cold War when he asserted, “In any war the result will not come from the battle put up by the western European countries. The outcome will finally depend on the armed forces of America. Let us keep our forces strong.”23

While much changed about the viability of isolation in a bi-polar Cold War world, these ideas did not dissipate. As U.S. commitments abroad transformed, in proxy or hot wars, and in an array of binding, overlapping treaties and alliances, American critics again returned to arguments for reducing international engagements. They noted the limits of U.S. power, and the need to concentrate resources on domestic as well as civil rights reforms. Some among these critics—ranging from Walter Lippmann and George Kennan to George McGovern and even Martin Luther King—were labeled “neo-isolationist” at the time. Such a label is misleading, however, and they resisted such a term.24

In the early years of the Cold War, the rise of a “new isolationism” was of pivotal concern to politicians, internationalists, and public intellectuals. Adlai Stevenson and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote about possible retrenchment. Worrying about Robert Taft’s possible nomination for the presidency, Schlesinger warned of a “sinister pattern” in deeds rather than words related to the new isolationism. Schlesinger, in a fascinating turn of logic, claimed that McCarthyism served as an integral component of the inward-looking, reactionary nature of post-World War II isolationist thought.25

Adlai Stevenson, in contrast, was more measured in his assessment. Still, he fretted that the nation needed to take up the mantle of world leadership more fully. His main fear was a gradual drawing away from globalism. Domestic prosperity and

23 Robert Taft, Speech to Senate, Congressional Record (July 11, 1949), pp. 9205-9209. 24 Many of the most potent expressions of “neo-isolationism” appeared in the mid-1960s and gained further traction into the 1970s in lockstep with opposition to the war in Vietnam. For the best representations of such views in the period, as they developed over time, see “The New Isolationism,” Time Magazine, January 8, 1965; Henry F. Graff, “Isolationism Again – With a Difference,” New York Times, May 16, 1965; Hans J. Morgenthau, “To Intervene or Not to Intervene,” (Originally: Foreign Affairs, April 1967), excerpted in James Hoge, Jr., and Fareed Zakaria, eds, The American Encounter: The United States and the Making of the Modern World (New York: Basic Books, 1997), pp. 265-273; “Harris Poll Finds New Isolationism,” New York Times, Feb. 6, 1970; Robert W. Tucker, “What This Country Needs Is a Touch of New Isolationism,” New York Times, June 21, 1972, quote from p. 43; see also, Hamilton Fish Armstrong, “Isolated America,” (Originally, Foreign Affairs, Oct. 1972) excerpted in The American Encounter: The United States and the Making of the Modern World, pp. 329-335. 25 Justus Doenecke, Not to the Swift: The Old Isolationists in the Cold War Era (Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1979).

Summer 2013 | 403

American Isolationism

economic concerns, he observed, was beginning to assume disproportionate importance in American politics and was leading toward geopolitical complacency26

The heart of modern isolationism continued to beat long after it had been declared dead following Pearl Harbor.27 In 1952 Walter Lippmann wrote, “The traditional and fundamental themes of American foreign policy are now known as isolationism. . . . That is a term, however, which must be handled with the greatest care, or it can do nothing but confuse and mislead,” he said.28 What may be most significant in tracing this history through to the present is that the very persistence of isolationist values shows another deep-rooted desire: the inclination to curb the destructive impulses of aggressive American democracy. America, as Lippmann observed, is rife with “contrary pushes which is to be too pacifist in time of peace and too bellicose in time of war.”29 In this reciprocal relationship, the modern (often idealistic) form of isolationism developed on the Left and the Right and became essential as a counter-balance to urges for war and intervention.

In the late 1960s and through the 1970s this push and pull appeared again with renewed vigor. Warnings of a “new isolationism” dominated the headlines amidst American involvement in Vietnam. But most potent were the calls for a “touch of new isolationism,” in light of the perceived failings of robust intervention. Indeed, the more the United States struggled to extend its influence abroad, the greater the appeal of isolationist values. As historian Robert Tucker wrote in a 1972 essay, a more circumspect isolationist outlook possessed significant advantages as well as a few considerable drawbacks. “The price of a new isolationism is that America would have to abandon its aspirations to an order that has become synonymous with the nation’s vision of its role in history.”30 Still, while American withdrawal from Vietnam and a less interventionist path in fighting proxy wars abroad attenuated the intensity of debates over isolationism, American leaders from both parties continued their dire warnings of a retreat into isolation. Others, generally Left intellectuals, such as Noam Chomsky and Dwight MacDonald,

26 Adlai Stevenson, “The Challenge of a New Isolationism,” New York Times, Nov. 6, 1949; Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “The New Isolationism,” The Atlantic Monthly, May 1952. 27 I paraphrase Selig Adler’s splendid expression at the outset of The Isolationist Impulse. 28 Walter Lippmann, Isolation and Alliances: An American Speaks to the British (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1952), p. 8. 29 Ibid. 30 Robert W. Tucker, “What This Country Needs Is a Touch of New Isolationism,” New York Times, June 21, 1972, and Tucker, A New Isolationism: Promise or Threat? (New York: Universe Books, 1972). For more on this sequence from the 1960s into the 1970s, see Hans J. Morgenthau, “To Intervene or Not to Intervene,” (Originally: Foreign Affairs, April 1967), in The American Encounter: The United States and the Making of the Modern World, pp. 265-273; “Harris Poll Finds New Isolationism,” New York Times, Feb. 6, 1970; Hamilton Fish Armstrong, “Isolated America,” (Foreign Affairs, Oct. 1972), in The American Encounter: The United States and the Making of the Modern World, pp. 329-335.

404 | Orbis

NICHOLS

however, cited the example of Vietnam as they contemplated the profound costs of American global overreach.31

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the demise of a significant Soviet threat, the relative quiescence of geopolitics in the 1990s led to new calls for American global policing and countervailing cries for more caution and inward focus in the new world order. Almost 40 years after warning of the rise of a “new isolationism,” Schlesinger Jr. revivified his case and argued that the new Republican Congress of the mid-1990s constituted an isolationism “risen yet again from the grave,” threatening “Wilson’s and F.D.R.’s magnificent dream of collective security.”32 In light of the 1996 and 2000 presidential elections and the pull of a protectionist, nativist argument for a new isolation, by, e.g., Pat Buchanan, as well as the impulse for a “smug and short-sighted isolationism,” attributed to Trent Lott and Dick Armey, the central problem of post-Cold War “isolationist” politics appeared to be generational, according to the New York Times. “An entire generation, the one just below George W. Bush’s, is growing up with no connection to World War II and only the dimmest memories of the cold war.” Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and George Bush found a rare point of complete agreement. Each derided what they saw as a generational inclination for the United States to be less active in a post-Cold War international system. Each, in his own way, argued for new avenues for American global commitment. Thus, as the New York Times phrased it, the challenge set for “internationalists in both parties will be to make the case for an expansive world view that defines broader diplomatic engagement and leadership by the United States as necessary components of national security and global stability.”33 Conclusion

Today the debates sound remarkably familiar. Isolationist ideas remain just

as significant as in the past (though they are not often considered in terms of “isolationism”). In the wake of 9/11 and ensuing U.S. military involvement abroad, these views operate as reflexive tests applied by Americans on both the right and left as they struggle to assess the nation’s global relationships.

The debates during the period from the 1890s through the 1930s represent the critical moment when the United States first fully confronted its ability to create major international change. Disputes over global engagement versus isolation have been intrinsic to broader conversations about what constitutes a “good society” and how such a society should operate at home, as well as abroad. This thinking still structures our view of the nation’s proper role in the world. 31 See Noam Chomsky, American Power and the New Mandarins (New York: Penguin Books, 1969); for insights into Dwight Macdonald’s thought, see A Moral Temper: The Letters of Dwight Macdonald (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001). 32 Arthur Schlesinger Jr., “Back to the Womb? Isolationism's Renewed Threat,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 1995. 33 “Isolationism’s Return,” New York Times, Oct. 31, 1999.

Summer 2013 | 405

American Isolationism

When President George W. Bush mentioned “isolationism” repeatedly in his 2006 State of the Union address, he was revisiting a century-old debate and recasting it in terms of modern concerns. “In a complex and challenging time,” he said, “the road of isolationism and protectionism may seem broad and inviting—yet it ends in danger and decline.”34 In this case, Bush deployed the potent caricature of the scared, naïve isolationist as his foil, and he was far from alone. A host of recent political commentators have hearkened back to either the lessons or the flaws of the Washington-Jefferson-Monroe isolationist tradition and its unilateralist “go it alone” ideology.

Contemporary figures echo the old critiques. They, too, tend to portray “isolationism” as atavistic, or something relegated to non-realists with a “cut and run” mentality. Yet as they make that case, these critics also tend to neglect attendant realities of today’s “flattened” global world, a concept that would not have been lost on the peripatetic missionary John Mott or international pacifist organizers Jane Addams and Emily Balch. In the 1930s it seemed to many Americans that the nation could afford to be relatively isolationist. However misguided that view was, recently critics of the U.S. interventions have turned to the isolationist tradition’s inherent caution, arguing that the ideas (if not the term) have innate value as a bulwark against hasty interventions and their likely unintended consequences.

And the beat goes on. In mid-summer 2007, The Economist examined how some of these past precedents are reflected in the present and warned that a U.S. turn to isolationism was possible. “America is indispensable” for world betterment, The Economist’s lead editorial stated. Yet it noted that “isolationism is also on the rise,” and wondered if new models for engagement were even possible given America’s recent geo-political setbacks and “new, rising sense [of isolationist retrenchment].”35 Over the past few years numerous politicians and pundits have exclaimed that President Obama’s policies represent “neo-isolationism;” or, as one author put it, his foreign policy marks a “throwback” to a “brand of isolationism that Americans haven’t heard from a major presidential contender in nearly a century.”36

Others have made the case that the entanglements of the twenty-first century are not intractable, but have placed the emphasis elsewhere. Rethinking the U.S. role in geopolitics seems less significant to many Americans than addressing pressing domestic economic challenges amidst increasing wariness about many 34 George W. Bush, “State of the Union Address of the President of the United States,” Jan. 31, 2006, at http://www.whitehouse.gov. 35 “American Power: Still #1,” The Economist, June 28 2007; also, “The Isolationist Temptation,” The Economist, Feb. 11, 2006. 36 For a modest sample of references that deal with isolationism in foreign policy vis-à-vis Iraq, Afghanistan, the “war on terror,” and free trade in international commerce, see Douglas Stone, “Obama’s Neo-Isolationism,” American Thinker, Aug. 11, 2008; Eric Trager, The New York Post, “Barack’s Throwback,” June 4, 2008; James Kirchick, “Barack Obama, Isolationist,” Standpoint Magazine, July 2008; Andrew Sullivan, “The Isolationist Beast Stirs in America Again,” The Sunday Times/Times Online, July 29, 2007; see also Ron Paul’s statements Summer-Fall 2009 on the Obama Administration’s “protectionist” isolationism and trade policy.

406 | Orbis

NICHOLS

forms of foreign relations. In the 2011 GOP Presidential debates, Governor Rick Perry articulated a version of such a view when he pledged to “zero out” foreign aid and asked about the U.N., “Why are we funding that organization?”37 Representative Ron Paul, for his part, stated, “We were never given the authority to be the policemen of the world.”38

A Pew poll released in December 2009—when President Obama was poised to add more troops to the conflict in Afghanistan—revealed American public isolationist sentiment at its highest level in forty years. In this poll and another one in 2011, between 46 and 49 percent of respondents stated that the United States ought to “mind its own business internationally” and leave other countries to their own devices. And 42-44 percent stated that because the United States “is the most powerful nation in the world, we should go our own way in international matters, not worrying about whether other countries agree with us or not.”39

Isolationist views have traveled sinuous, braided routes to the deliberations of the present day. Current nationalist hawks, as well as internationalist doves, employ symbols, images, and tropes that would be familiar to those who considered the global role of the United States from the 1890s through the 1930s. Americans continue to invoke these scripts in ways remarkably consistent with these past thinkers.

Before the United States embarked on the “American Century,” a vigorous debate raged over whether America’s priorities should lie in domestic or in foreign fields. Although largely forgotten by historians, fin de siècle isolationism represented a critical development in American political thought. As we have seen, virtually all assertions of an isolationist-orientation involved some form of international engagement and defy the caricature of isolationism as advocating a fully “walled-and-bounded” political, economic, and cultural removal from the world.

It is a bold but accurate statement to say that isolation continues to be a national value. Often history reveals that the values that are most central are also those that are most contested. Specific interpretations of “isolation” remain subject to vigorous debate. Indeed, these interpretations have been as different as the people who have articulated them. But the persistence of isolationist principles reveals how such notions served to broaden the range of perspectives on how the United States might act in the world. In turn, the shift from debating empire to debating isolation revolved around developing visions of modern internationalism

37 Quoted from CBS News reporting: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-20122309-503544.html (accessed April 3, 2013). 38 For Ron Paul quotes, see: http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2011/sep/14/ron-paul/ron-paul-says-us-has-military-personnel-130-nation/; and see: http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/politics/2011/06/ron-paul-nothing-for-us-to-be-gained-by-leaving-troops-in-afghanistan/ (accessed April 3, 2013). 39 Pew Research Center for the People and Press, “America’s Place in the World,” Pew Poll undertaken with the Council on Foreign Relations, full report located at http://people-press.org/report/569/americas-place-in-the-world (released and accessed on Dec. 3, 2009).

Summer 2013 | 407

American Isolationism

and innovative views about domestic reform. At stake were essential definitions of the meaning of America and the nation’s international options. These elemental attributes of the debates over modern isolationism have been critically important in the past, and as the United States repositions itself and reorients its relations to—and in—the world in light of the changing geopolitics of the twenty-first century, it seems clear that they will remain vital within the national forum of tomorrow.