Commission Designates East MS Connect as ETC; Opens Door ...

The Door Opens: New Options Available to Manufacturers to ...

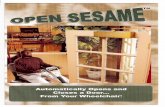

Transcript of The Door Opens: New Options Available to Manufacturers to ...

- 1 -

The Supreme Court’s recent decision

in Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc.v. PSKS, Inc.,1

dramatically alters the

relationship between manufacturers and

distributors by permitting manufactur-

ers, under certain circumstances, to

exert greater influence and control over

the prices charged by distributors. The

Leegin case creates such a fundamental

change in the law that all manufacturers

should consider the import of the deci-

sion on their business, including

whether to adopt policies or enter into

agreements with distributors concerning

resale prices.

The Legal Landscape Before LeeginIn Leegin, the Supreme Court over-

turned almost 100 years of jurispru-

dence, first established in Dr. MilesMedical Co. v. John D. Park & SonsCo,2

that made it a per se violation of

Section 1 of the Sherman Act for manu-

facturers and distributors to agree upon

minimum resale prices. By requiring

application of the per se rule to resale

price maintenance agreements in Dr.

Miles, the Supreme Court deemed such

agreements to be presumptively anti-

competitive, and therefore prohibited

proof from being introduced concerning

whether such agreements had procom-

petitive benefits for consumers.

Shortly after the Dr. Miles decision,

the Supreme Court held in U.S. v. Col-gate & Co.3

that a manufacturer who

unilaterally announces a suggested

resale price policy and refuses to supply

distributors that do not comply, does not

violate Section 1 of the Sherman Act

because no concerted conduct is

involved.

After Colgate, many manufacturers

adopted suggested resale price policies

and many continue to have such policies

today. However, manufacturers have

often had great difficulty enforcing their

policies in a manner consistent with

Colgate because of a lack of judicial

uniformity and clarity concerning when

permissible “exposition, persuasion and

argument”

4

crossed the line into coer-

cion such that a de facto agreement was

said to have existed.

5

Thus, for the past 100 years manu-

facturers have been placed in the unten-

able position of choosing between the

safest legal option, which involved ter-

minating distributors without issuing

any warnings or having any conversa-

tions with violating distributors, or

employing other more practical business

measures involving a dialogue with vio-

lating distributors but doing so with sig-

nificant legal risks.

The Leegin Decision

Leegin is a manufacturer of leather

goods and accessories that distributes

primarily to small boutiques and inde-

pendent stores. Leegin adopted a policy

whereby it refused to sell products to

retailers that charged prices below its

suggested prices. The purpose of the

policy was to maintain Leegin’s brand

image and give retailers enough margin

to provide excellent customer service.

Leegin, like many other manufacturers

before it, implemented its policy poorly

by engaging in conduct that could be

construed as constituting an agreement.

Specifically, Leegin adopted a market-

ing strategy that, in part, required retail-

ers to pledge to sell the company’s prod-

ucts at its suggested resale prices.

Defendant PSKS operated a women’s

apparel store known as Kay’s Kloset,

which sold goods by approximately 75

different manufacturers; Leegin’s prod-

ucts constituted 40 to 50 percent of the

company’s profits. Leegin refused to

supply Kay’s Kloset after learning that it

had discounted products below the sug-

gested resale prices. Kay’s Kloset filed

suit in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Texas, alleg-

ing that Leegin engaged in unlawful

resale price maintenance in violation of

Section 1 of the Sherman Act.

During the trial, Leegin attempted to

introduce expert testimony concerning

the procompetitive effects of its pricing

The Door Opens: New Options Available

to Manufacturers to Exert Increased Influence

and Control Over Resale Prices

–By Michael Hahn, Lowenstein Sandler PC

Michael Hahn

FOCUS on New Jersey

- 2 -

Options Available Post-LeeginLeegin arguably “opens the door” for

manufacturers to exert greater influence

and control over resale prices. Now,

post-Leegin, a manufacturer might

choose to enter into a contract with its

distributors to set minimum resale

prices. This option allows a manufac-

turer to exert greater control over dis-

tributor pricing, as well as the levels of

service that justify such increased pric-

ing. In fact, distributors could be liable

for breach of contract if they sell cov-

ered products below the agreed upon

minimum prices.

The potential risk to a manufacturer

choosing this option is that in a lawsuit

where a Section 1 violation is alleged,

the agreement element of the Sherman

Act would be easily satisfied because

the defendant manufacturer entered into

a contract concerning resale prices. The

effect of Leegin, however, is that a

plaintiff must also prove that the anti-

competitive effects of the resale price

maintenance agreement outweigh any

procompetitive benefits. Therefore, it is

imperative that before a manufacturer

enters into such an agreement, it must

carefully analyze the market in which it

operates and the potential impact that a

resale price maintenance agreement

could have on competition.

Alternatively, a manufacturer might

choose to adopt a suggested resale price

policy or continue to implement its cur-

rent suggested resale price policy. Aside

from a manufacturer not involving itself

at all in a distributor’s resale prices, this

is the most conservative and litigation-

averse option because an antitrust plain-

tiff would need to prove that the

manufacturer’s policy was implemented

improperly such that a de facto agree-

ment would exist and that the anticom-

petitive effects of the agreement

outweigh the procompetitive benefits.

Leegin has reduced the risks associ-

ated with this alternative option because

many manufacturers, even with the best

intentions of complying with Colgate,had difficulty controlling the coercive

conduct that certain sales employees

used to induce compliance with pricing

policies. Prior to Leegin, such conduct

often resulted in liability, but now such

conduct must be coupled with a showing

of anticompetitive effect in the relevant

market. In other words, plaintiffs are

now more likely to be dissuaded from

policy. Leegin’s expert opined that

resale price maintenance could be pro-

competitive by promoting interbrand

competition (i.e., competition between

competing brands) and eliminating “free

riding” (for example, when a consumer

obtains assistance with a product from a

full service retailer and then ultimately

purchases it from a lower priced retailer

that does not provide such services). The

expert also opined that the resale price

maintenance agreement, which Leegin

was alleged to have engaged, was pro-

competitive for these very reasons. The

trial court barred the testimony of Lee-

gin’s experts on the basis that such pro-

competitive justifications were

irrelevant under the per se rule estab-

lished in Dr. Miles. The jury returned a

substantial verdict against Leegin.

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit upheld

the trial court’s decision, also relying on

the per se rule established in Dr. Miles.When the case reached the Supreme

Court, the issue presented was whether

resale price maintenance agreements

should be adjudicated under the per serule (i.e., where a plaintiff need only

prove the existence of an agreement) or

the rule of reason (i.e., where a plaintiff

must prove both the existence of an

agreement and that the agreement had a

net anticompetitive effect in the relevant

market).

The Supreme Court determined that

there are numerous situations where

resale price maintenance agreements

can have a procompetitive effect on

interbrand competition (i.e., competition

between competing brands), and also

that there are situations where a deleteri-

ous effect can result. Because of the

diversity of possible economic conse-

quences from such conduct, the

Supreme Court held that resale price

maintenance agreements, such as that at

issue in Leegin, should no longer be

adjudicated under the per se rule, but

instead under the rule of reason. In

doing so, the Court harmonized the legal

standards applied to resale price mainte-

nance agreements with other types of

agreements typically entered into

between manufacturers and distributors

(e.g., a manufacturer’s allocation of

exclusive territories to distributors).

Additionally, the Court remanded the

Leegin case for consideration consistent

with its decision.

filing an antitrust lawsuit alleging

unlawful resale price maintenance

because there are additional proofs,

some which will result in an expensive

“battle of the experts.”

Last, a manufacturer might consider

it prudent to wait and see how resale

price maintenance agreements are

treated by lower courts under the rule of

reason before deciding on a course of

action. Indeed, the Supreme Court high-

lighted the unknown variables when it

stated that “As courts gain experience

considering the effects of these restraints

by applying the rule of reason over the

course of decisions, they can establish

the litigation structure to ensure the rule

operates to eliminate anticompetitive

restraints from the market and to provide

more guidance to business. Courts can,

for example, devise rules over time for

offering proof, or even presumptions

where justified, to make the rule of rea-

son a fair and efficient way to prohibit

anticompetitive restraints and to pro-

mote procompetitive ones.”

6

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in

Leegin fundamentally changes the rela-

tionship between manufacturers and dis-

tributors concerning resale prices. Every

manufacturer should evaluate its need

for minimum resale prices, the potential

impact in the marketplace in which it

operates and the new legal framework

created by the Supreme Court.

1. 127 S. Ct. 2705 (June 28, 2007).

2. 220 U.S. 373 (1911).

3. 50 U.S. 300 (1919).

4. See, e.g., Acquaire v. Canada Dry Bot-tling Co., 24 F.3d 401, 410 (2d Cir. 1994)

(“Evidence of pricing suggestions, per-

suasion, conversations, arguments, expo-

sition, or pressure is not sufficient to

establish coercion necessary to transgress

§ 1 of the Sherman Act”).

5. See, e.g., Yentsch v. Texaco, Inc., 630

F.2d 46, 52 (2d Cir. 1980) (“We think

there was sufficient evidence here,

although just barely, to find an illegal

combination to maintain resale

prices…”).

6. Leegin, 127 S. Ct. at 2720.