The Digital Temple: A Preview of Features, Current and Potential

-

Upload

robert-whalen -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of The Digital Temple: A Preview of Features, Current and Potential

The Digital Temple: A Preview of Features, Currentand Potential

Robert Whalen*Northern Michigan University

Abstract

The Digital Temple is an electronic scholarly edition of George Herbert’s English verse. Whencomplete, it will include diplomatic and modern-spelling transcriptions linked to correspondingdigital images of three essential artifacts: Williams Manuscript Jones B62, Bodleian ManuscriptTanner 307, and a copy of The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations (first edition, 1633).The transcriptions are accompanied by critical annotations and glosses, and all materials – tran-scriptions, images, and apparatus – are presented through a customized user interface. The tran-scription files are marked up according to the Text Encoding Initiative P5 standard, a robustencoding protocol rendering the texts susceptible to an array of display and data search-and-retrie-val operations. This essay briefly introduces the resource, its principal features and potential, anddiscusses some of the technical underpinnings that make it a potentially powerful research tool.

George Herbert (1593–1633) was a priest in the Church of England, Public Orator atCambridge, and author of The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations, widely con-sidered the finest book of devotional verse in the language. With Shakespeare’s Sonnets(1609) and the first folio of the plays (1623), Ben Jonson’s Works (1616), and Donne’sPoems (1633), The Temple is also among the most significant publications of the earlymodern era.

The Digital Temple is a genetic ⁄documentary edition of Herbert’s English poems. Itsobjectives are to bring together the primary materials essential to the study of the Temple;to preserve the resulting database in a way that will ensure maximum portability, robust-ness, and longevity; to facilitate access through a flexible user interface; and to promotereading of Herbert’s verse from a genetic editorial perspective. The final product willinclude diplomatic and modern-spelling transcriptions linked to high-resolution direct-to-digital scans of three artifacts: Williams Manuscript Jones B62, Bodleian ManuscriptTanner 307, and a copy of The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations. A criticalapparatus appropriate to the digital medium and an interface enabling efficient navigationand querying will complement these materials. Its richly encoded transcriptions, high-resolution images, and full-text parallel display distinguish the Digital Temple fromanything currently or formerly available, including the Hutchinson, Di Cesare, andWilcox editions. Though masterful in many respects, these are constrained necessarily bylimitations to which a digital edition is not subject.

Some aspects of the relationship among the sources of Herbert’s poems are not fullyknown, but here are a few general observations. The Williams manuscript, transcribedsometime between 1615 and 1625 by an amanuensis and emended by Herbert, containsroughly half the poems found in the later manuscript and first edition, plus several poemsthat do not appear in either. The Bodleian manuscript was transcribed shortly following

Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.x

ª 2011 The AuthorLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Herbert’s death in 1633, very likely from a source other than Williams. This later manu-script may have served as the copy text for the first edition – the first page looks verymuch like the title page of a printed book and includes the names of the licensers at theCambridge Press – but the manuscript is otherwise unmarked. The first edition of TheTemple follows the Bodleian manuscript in most substantive matters, but also introduces afew significant typographic and layout features not present in either of the manuscripts.

Creation of the Herbert manuscripts and first edition spanned one of the more fractiousperiods in England’s religio-political history, just prior to the Civil War; they are a fascinat-ing index of one writer’s engagement with an ideologically volatile world. Students andteachers of early modern literature, literary scholars, and historians of 17th-century politicsand the English church will have access in a single resource to the evolving art of an impor-tant establishment divine. The high-resolution images will also serve bibliographical studies,and the richly encoded transcriptions will allow scholars from a range of disciplines toexplore the database with the aid of text analysis software. But the principal purpose inbuilding such an edition is to combine unmediated access to the three artifacts with a criticalapparatus that does not elide significant differences among them. The Digital Temple nei-ther champions the manuscripts as finally more authoritative than the first edition, nordiminishes the value of an eclectic transcription, such as those of the Wilcox and Hutchin-son volumes. However, though a good eclectic edition accounts for all variants, its singletranscription cannot avoid favoring one authoritative source over another wherever theydiffer. Parallel display of multiple witnesses in a digital environment forgoes the (perhapsunintentional) rhetorical illusion of a single stable text in favor of an (albeit equally rhetori-cal) emphasis on difference and instability. Insofar as Herbert’s verse is a product of conver-gence between 17th-century manuscript and print cultures, the posthumous first edition isof interest precisely because it contains traces of that convergence.

That the manuscript scribes and Cambridge printers are ontologically implicated in thepoems conceived and composed by George Herbert supports Jerome McGann’s social-text theory of editing. Drawing a sharp distinction ‘between a work’s bibliographical andits linguistic codes’ (52), McGann argues that ‘as the process of textual transmissionexpands, whether vertically (i.e., over time) or horizontally (in institutional space), thesignifying processes of the work become increasingly collaborative and socialized’ (58).This collaborative process includes all producers of the text: authors, amanuenses, printers,publishers, compositors, book designers, etc. The transmission of Herbert’s poems, fromcomposition to publication, has a history, an ontogeny that can enrich our understandingof their meaning. Parallel access to the three earliest sources allows us to see the poemsnot as pristine objects but rather evolving ars opera.

The greatest advantage of a digital edition is the limitless ‘space’ available for presentingall relevant materials. Rather than consulting a textual apparatus to reconstruct actual wit-nesses in the abstract, the Digital Temple user might simply view the several versions side-by-side. Presenting Herbert’s poems in this way is not without theoretical consequence, forit assumes that difference matters and should be in the foreground. It is to endorse an impor-tant aspect of W.W. Greg’s influential editorial theory – namely the need to be wary of the‘tyranny of the copy-text’, for ‘the text rightly chosen as copy may not by any means be theone that supplies most substantive readings in cases of variation’ (26) – but to be skepticalnevertheless of Greg’s confidence in ‘the text rightly chosen as copy’ for the creation of aneclectic transcription. In Genetic Criticism, Deppman, Ferrer, and Groder argue that the edi-tor’s primary concern is not some final textual state, or even texts at all but rather ‘the writ-ing processes that engender them’. Whereas ‘a textual critic will tend to see a differencebetween two states of a work in terms of accuracy and error or corruption’, the genetic

108 The Digital Temple

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

critic and editor ‘will see meaningful variation. Although both scholarly activities deal withmanuscripts and textual versions, their aims are quite different’ (11). The Digital Templetreats all of its sources, first edition included, as members of an ‘avant-texte’, a ‘critical con-struction elaborated in relation to a postulated terminal—so-called definitive—state of thework’ (8), implying, indeed, that there is no texte as such unless by that we mean an abstracteclectic transcription. The present article does not describe or defend in detail the DigitalTemple’s editorial rationale (but see Whalen, 2010, 2008, passim). I would acknowledge,however, that authorial intention and the question of whether its revision history is relevantto a poem’s meaning are complex issues. More contentious still, perhaps, is the question ofwhether anything but an eclectic edition is in fact an edition. What, after all, is a scholarlyedition if not the painstaking construction of an ideal text from among disparate sources?Well, much depends on what we mean by ideal. The Digital Temple presupposes thatlightly mediated access to all relevant source materials is a desirable goal. Such a resource canenrich our experience of Herbert’s work – not just as scholars with an interest in such detail,but as readers of poetry fascinated by the evolution of perhaps the liveliest devotional mind,and certainly one of the most technically brilliant versifiers, in the English tradition.

The Digital Temple consists of five components:

1. the artifacts as represented by high-resolution digital images;2. diplomatic and modern-spelling transcriptions of their contents;3. a set of critical annotations and glosses;4. a user interface facilitating flexible navigation of these materials;5. the technical network of text and computing languages – a text ⁄ code base – that

resides below the surface.

Though most users will have little occasion to deal with this latter component, it is in everyrespect the heart of the project: for decisions about computational code have an enormousimpact on what users ultimately can and cannot do with the resource. Here, then, is a briefdemonstration of the Digital Temple’s user interface in its current form followed by a dis-cussion both of its technical underpinnings and other features of the text ⁄ code base whosepotential for further exploration has yet to be incorporated into the interface.

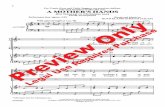

I begin with Herbert’s poem, ‘The Pearl’ – three transcriptions in parallel display usinga modified iteration of the Versioning Machine (v.4.0), open-source software created bySusan Schreibman at the University of Maryland and developed by a team of computingand literary scholars that includes myself (Fig. 1).

At the left are the first two stanzas as transcribed from Williams Manuscript Jones B62(w); at the center is Bodleian Manuscript Tanner 307 (b); and at the right is the first edi-tion (p). Any version can be made to appear in any of the three windows by selectingfrom the drop-down ‘Witness’ menu at the top of each. (Horizontal lines indicate pagebreaks, below each of which is an icon linked to an image of the corresponding sourcepage.) It is also possible to close any one or two of the witness windows by clicking onthe X to the right. (The right-margin justification of all lines is one of three possible set-tings in the software as currently configured, the others being left-margin and center.The setting chosen here only approximates how the poems actually appear in the sources.The inclusion of links to high-resolution images obviates the need for a more accuraterendering of layout – not to mention the painstaking markup that would be required tofacilitate it.) Here are the Williams and Bodleian transcriptions (Fig. 2), now with the lineindicators hidden by unchecking the ‘Line Numbers’ box at the top, and the line-by-lineannotation links revealed by selecting from the drop-down menu to the right of the ‘Line

The Digital Temple 109

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Numbers’ box. One such annotation, a brief headnote next to the title, is shown in thew panel as a temporarily activated pop-up window.

One may also choose to gather all notes in a separate panel (Fig. 3) by selecting thatoption in the ‘Notes’ drop-down menu.

Unless otherwise indicated, each note pertains to all available witnesses. Notice thatwhere a note applies to all witnesses, variant spellings and orthography are handledusing virgules (e.g., conspire/conſpire in the note for line 5). Notice too the small pop-up window in the witness-w panel to the left. Though the transcriptions are diplo-matic, the text ⁄ code base includes modern spellings, activated simply by dragging thecursor over any word. Future plans include a switch to enable or disable this feature as

Fig. 1. ‘The Pearl’, as transcriptions from Williams MS. Jones B62 (w), Bodleian MS. Tanner 307 (b), and TheTemple, first edition (p).

Fig. 2. ‘The Pearl’, as transcriptions from the Williams (w) and Bodleian (b) manuscripts, with pop-up annotationlinks (headnote showing).

110 The Digital Temple

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

desired. Where only one or two witnesses are targeted, the note indicates which. Here,for example, are the transcriptions and notes for the emended lines 21–30 (Figs 4 and5).

The most obvious aesthetic advantage of the Digital Temple is access to high-qualityimages of the sources. Here, again is ‘The Pearl’, now showing all three transcriptions,with the notes function disabled, and a direct-to-digital image from Williams ManuscriptJones B62 (Fig. 6).

The image viewer can be positioned anywhere on the screen by clicking and dragging.Plans also include a zoom feature and the ability to click and drag the image itself withinthe image viewer. Notice that in the w transcription horizontal strike-through lines havereplaced the diagonal lines in the source for the simple reason that I’ve yet to find ordevise a code template that would allow the transcription display to mimic the original tothat degree of accuracy. The same is true of the emendations ‘gustos’ to ‘lullings’ (line22) and ‘twenty’ to ‘many’ (line 25), where the transcription must, of technical necessity,render the changes linearly rather than directly over the words they replace. As men-tioned above, access to images of the sources obviates the need for such close fidelity inthe transcriptions. What matters, from a data search-and-retrieval point of view, is thatdeletions and additions have been captured in the markup, the code that lies below thesurface.

As already mentioned, that text ⁄ code base includes modern spellings. The word huſwife(line 4), for example, looks like this in the code:

<w lemma=‘‘housewife’’><choice><orig>huſwife < ⁄orig><reg>housewife< ⁄ reg>< ⁄ choice>< ⁄w>Included here is the word’s modern OED headword as well as the original and mod-

ernized versions. The lemma and regularization happen in this case to be identical – thesingular nominative form of the word – hence the duplication. This is not so for theword following huſwife in line 4, spunn –

Fig. 3. ‘The Pearl’, as transcriptions from the Williams manuscript (w) and the first edition (p), with annotations indiscrete panel and pop-up showing modernized spelling.

The Digital Temple 111

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

<w lemma=‘‘spin’’><choice><orig>spunn< ⁄orig><reg>spun< ⁄ reg>< ⁄ choice>< ⁄w>– where the OED headword or lemma is the infinitive form of the verb and spun the

past participle. The word spun does appear as a headword in the OED, but only as a par-ticipial adjective.

Fig. 4. ‘The Pearl’, lines 21–30, as transcriptions from the Williams (w) and Bodleian (b) manuscripts and firstedition (p).

Fig. 5. Annotations for ‘The Pearl’, lines 21–30.

112 The Digital Temple

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

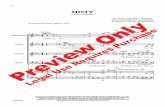

This level of detail in the text ⁄ code base enables the tool-tip mechanism mentionedabove, where a given word’s modern equivalent can be displayed by dragging the cursorover it (see Fig. 3). Indeed, a simple change to the Versioning Machine’s display codeallows a modern-spelling view. Here, for example, is ‘Easter Wings’ (Fig. 7).

Though yet to determine whether to include this option, we are reluctant on heuristicgrounds. Modernization flattens out differences among the several versions; we wouldprefer that all users have the opportunity to become familiar with the conventions ofearly modern spelling and orthography as well as differing scribal and printing practices.(Though not immediately apparent in the display, all ligatured characters in the first edi-tion have been distinguished in the diplomatic markup. Go back, for example, to Fig. 6,lines 38–39 in the first-edition panel to the right, where ‘ſilk twiſt’ and ‘conduct’ containlong-s ⁄ i, long-s ⁄ t, and c ⁄ t ligatures, respectively.) The unobtrusive tool-tip mechanismallowing one to reveal the modernization of a given word is sufficient to help studentsalienated by those conventions to acquire familiarity with little effort. Personal preferencesaside, however, it couldn’t hurt to forgo imposing this curmudgeonly fetish on othersand therefore to install a switch enabling the modern-text option. For now, pleaseindulge us (Fig. 8).

This brief showcase has highlighted some of the user features so far devised for theDigital Temple. Additional plans include access to any one of the three witnesses in itsentirety (excepting the Latin poems in the Williams manuscript), including tables of con-tents and all forme-work features, as well as synchronized scrolling whereby the transcrip-tions and images may be viewed effortlessly side-by-side. Another exciting possibility,pertaining in particular to the 1633 edition, is a mechanism that allows the user virtuallyto ‘unfold’ the book’s individual sheets, made possible by adding signature attributes tothe page-break tags already included in the markup. Users would thereby see the sheets’inner and outer formes as they appeared to the Cambridge printer before being perma-nently folded, gathered, and bound in 1633. Of course, no digital book can ever replacethe experience of examining the real thing. The obverse, however, is that the computercan allow us to see precious artifacts in ways not possible otherwise. (Imagine a librarian’s

Fig. 6. ‘The Pearl’, as transcriptions from the Williams (w) and Bodleian (b) manuscripts and first edition (p), withan image of lines 21–40 as they appear in Williams (58r).

The Digital Temple 113

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

horror at the prospect of dismantling a copy of the first edition of The Temple!) A moredistant future possibility is the expansion of the currently light annotations to include avariorum feature extending that of Helen Wilcox’s magisterial Cambridge edition: a briefreview of the essential critical history for each poem with direct links to the works refer-enced. Though not currently feasible, such a feature soon will be – and, unlike the appa-ratus of a print edition, it would be extensible and thus easily revised to includesignificant future additions to the critical literature.

Perhaps the most significant advantage of a digital Herbert is its susceptibility to soft-ware-enabled analysis. Because it includes both original and normalized spellings as wellas original abbreviations and their expansions, the Digital Temple’s text ⁄ code base ensures

Fig. 7. ‘Easter Wings’, as modern-spelling transcriptions from the Williams (w) and Bodleian (b) manuscripts andfirst edition (p).

Fig. 8. ‘Easter Wings’, as diplomatic transcriptions from the Williams (w) and Bodleian (b) manuscripts and first edi-tion (p), with an image of lines 11–20 as they appear in Williams (28r) and pop-up showing modernized spelling(witness-p, bottom right panel).

114 The Digital Temple

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

accurate and thorough retrieval of all data relevant to a given query. To cite a simpleexample, the query ‘foreign’ would also retrieve ‘forrain’, ‘forren’, and any other semanti-cally identical but orthographically dissimilar character string because all such instances areresolved in the code to a single lemma. The code also includes tags for all deletions, addi-tions, and marginal notes, as well as forme-work features (running titles, page and folionumbers, catchwords, and signatures). Using text analysis software, it would be possible,for example, to summon all instances of deletion and ⁄ or addition along with their folionumbers in, say, the Williams manuscript; or to determine the frequency and measurethe relative significance of co-occurring words; or, in a broader sense, to study Herbert’sidiolect – the poet’s (largely unconscious) semantic, syntactic, and stylistic patterns. Suchtasks are possible based on the project’s current markup. A more immediate future plan isto encode one of the transcriptions (probably that of the first edition) for verse forms,rhyme, meter, and other aural dynamics. Given Herbert’s reputation as a master techni-cian, this will be a welcome feature.

The ability to take advantage of such rich encoding will be built directly into the pro-ject’s user interface. University of Virginia Press, Digital Imprint (to whom the project iscurrently contracted for publication) is home to the MarkLogic Server which has featuresallowing for the construction of numerous search ⁄ retrieval operations, including, forexample, word lexicons and thesaurus functions. But plans for the Digital Temple includemore advanced features – for example, a mechanism for retrieving word co-occurrences(node ⁄ cognate pairs) within a given span, displaying them as a Key-Word In Context(KWIC) list, and measuring the relative significance of the co-occurrences; and anothermechanism for taking advantage of the aural-dynamics encoding mentioned above (allow-ing a user to summon, say, all pentameter lines beginning with a trochaic foot). Theseare but two possibilities. The point is that richly encoded electronic texts – as opposed tolarge databases, such as Google Books that lack this level of granularity – present unprece-dented reading and research opportunities.

No comprehensive digital edition of Herbert’s verse is available. Several electronicanthologies, such as Representative Poetry On-line, provide selections. The FIEN Group’sClassictexts poetry anthology, available both online and as a CD-ROM, includes a tran-scription of the 1633 edition. Luminarium also has transcribed the 1633 Temple and thereis a similar anonymous website (George Herbert and the Temple) that includes six black andwhite images from what appears to be a copy from facsimile. All of these, however, arestrictly HTML-encoded texts – useful only for a web-browser or PDF reader – and offeronly one text. Early English Books Online (EEBO) includes images and a transcription ofthe 1633 edition only. The images are from microfilm – of a quality considerably poorerthan what is envisioned here. More importantly, the transcription ⁄encoding is intendedsolely for reading and large-corpora searching. Its scope and encoding granularity farexceeding those of EEBO’s Herbert, the Digital Temple is certain to be preferred byscholars, teachers, and students of early modern literature.

The project is encoded using TEI(P5)-XML. XML (eXtensible Markup Language) isa kind of meta-language: a set of rules according to which a computing language canbe constructed. The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) is a consortium of humanities com-puting scholars whose purpose is to devise universal standards for the creation, preserva-tion, and transmission of platform-independent electronic texts. The TEI provides acomprehensive set of XML-based protocol with which to label both the intellectualcontents and visual features of any textual artifact. It is only partially prescriptive, how-ever. Rather than tell an editor which features to include, the TEI Guidelines providean almost exhaustive set of ‘tags’ (i.e., markup labels) from which to choose. The

The Digital Temple 115

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

creator of the electronic text must determine what he or she wishes to do with an arti-fact and then set about searching the TEI guidelines for appropriate solutions. The goldstandard in humanities computing, the protocol of the TEI has been used extensivelyfor digital scholarly editions in the past decade. It allows digital editors to represent themultiple sources and their complex relationships in ways that permit them to be que-ried, manipulated for display purposes, and analyzed. It also permits one to include alevel of encoding detail suited to the disciplinary standards of Renaissance scholarlyediting. Editorial information, such as spelling modernization and textual emendationsare captured through the markup to enable flexible display and search options. Theproject-specific TEI protocol also allows for organizational simplicity – all sources tran-scribed and indexed within a single XML file. My preference is to allow users to takefull advantage of the rich encoding by making available the TEI-XML source, whichcan then be analyzed using programs of their choice – though most users are likely torely on the search mechanisms planned for the interface using UVaP’s MarkLogic ser-ver. Moreover, because the transcriptions will be completely portable to other XMLpublishing frameworks, and as new interface tools emerge and TEI-XML publishingbecomes more powerful and sophisticated, we will be able to take advantage of thosedevelopments using the same encoded source. This crucial aspect ensures the edition’slongevity as a research tool.

It is with no little fear and trepidation that we will launch this resource in the wake ofthe 2007 Cambridge edition of Herbert’s English poems. Helen Wilcox’s volume is amonument to a great poet, its critical apparatus embodying hard-won erudition and sensi-tivity of a degree we can only admire rather than aspire to. Our hope, however, is toprovide a vital digital complement to a fine print edition as Herbert studies moves for-ward into the 21st century. Access to high-resolution images, parallel display, and sophis-ticated search mechanisms might encourage the curious reader to consider new ways toexplore Herbert’s work. Now, we are aware that the term curious in Herbert is often anegative one, and can only imagine what he might have thought of a digital Temple(however, ludicrous is such speculation). Recall the ‘curious questions and divisions’ (line12) of the hapless ‘men’ (line 1) in ‘Divinitie’; or perhaps, to misquote lines 152–154from ‘The Church Militant’, we’ve been

given over, for [our] curious arts,To such [digital] stupidities,As [e’en, say, Bill Gates] would deem prodigies.

We trust, however, that for students of Herbert’s verse Providence ‘hath the vertue toexpresse the rare ⁄ And curious vertues’ even of mere ‘herbs and stones’ (‘Providence’,lines 73–74) such as are offered in this new resource.

Acknowledgement

The project editors, Robert Whalen and Christopher Hodgkins, gratefully acknowledgethe support of our institutions, Northern Michigan University and the University ofNorth Carolina, Greensboro. The Digital Temple is currently supported by a NationalEndowment for the Humanities Scholarly Editions Grant, and Robert Whalen wishesalso to thank the NEH for a 2009-2010 Research Fellowship. Any views, findings, con-clusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those ofthe National Endowment for the Humanities, Northern Michigan University, or theUniversity of North Carolina.

116 The Digital Temple

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Short Biography

Robert Whalen, a professor of Renaissance Literature at Northern Michigan University,is author of The Poetry of Immanence: Sacrament in Donne and Herbert (University of Tor-onto Press, 2002) and articles on digital editing. His 2001 Renaissance Quarterly article,‘George Herbert’s Sacramental Puritanism’, was recently selected for reprint in HaroldBloom’s collection, John Donne and the Metaphysical Poets (Chelsea House, 2010).

Note

* Correspondence: Department of English, Northern Michigan University, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette,MI 49855, USA. Email: [email protected]

Works Cited

Deppman, Jed, Daniel Ferrer, and Michael Groden. Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-textes. Philadelphia: Universityof Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Di Cesare, Mario A. The Temple: A Diplomatic Edition of the Bodleian Manuscript (Tanner 307). Binghamton, NY:Medieval and Renaissance Texts Society, 1995.

Greg, W. W. ‘The Rationale of the Copy-Text.’ Studies in Bibliography 3 (1950): 19–36.Hutchinson, F. E. The Works of George Herbert. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1941.McGann, Jerome. The Textual Condition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.Text Encoding Initiative P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange. 22 Nov. 2010. <http://www.

tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/index.html>.Whalen, Robert. ‘Digitizing George Herbert’s Temple.’ E-Publishing: Politics and Pragmatics. Ed. Gabriel Egan. Tor-

onto and Tempe, AZ: Iter and Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 2010. 31–54.——. ‘Enter Tagger: Encoding (Reading) the Digital Temple.’ New Paths for Computing Humanists. Eds. Ray Sie-

mens, Gary Shawver for a special issue of Digital Studies ⁄ Le champ numerique 1.1 (2008): 22 Nov. 2010. <http://www.digitalstudies.org/ojs/index.php/digital_studies/article/view/145/195>.

Wilcox, Helen. The English Poems of George Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

The Digital Temple 117

ª 2011 The Author Literature Compass 8/2 (2011): 107–117, 10.1111/j.1741-4113.2010.00769.xLiterature Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd