The consumer guide to competition - International Development

Transcript of The consumer guide to competition - International Development

The consumerguide to competition:A practical handbook

March 2003

Com

petit

ion

and

com

petit

ion

polic

y

Con

clus

ions

Con

sum

ers

and

com

petit

ion

Con

sum

ers

and

regu

latio

n

Acknowledgements

The Consumer Guide to CompetitionHandbook was written by Phil Evans atConsumers Association, UK and edited byLezak Shallat from Consumers InternationalRegional Office in Santiago, Chile. This workwas undertaken within the ConsumerMovement and Competition Policy Post Dohaprogramme, which is funded by the UKDepartment For International Development(DFID). However, in addition to gratefullyacknowledging the support of DFID, this workbuilt on existing activities funded by the FordFoundation, the ministry of foreign affairs ofthe Dutch Government, the European Union,the International Development and ResearchCentre (IDRC), and Oxfam.

Designed and produced by Steve Paveley

© Consumers InternationalMarch 2003

ISBN 1 902391 42 X

2

Acknowledgements

3

Contents

Introduction 6Assessing assumptions 6

Section 1: Competition and competition policy 9

Part I: What is competition? 10

Part II: What competition does 12Direct gains 12

Lower prices 12More choice 14New entrants 14Better service 14

Indirect gains 15Efficiency and productivity gains 15What about jobs? 17

Part III: Impact of Competition Law and Policy 19

Section 2: Consumers and competition 23

Part I: Markets and consumer behaviour 24Classical model of consumer behaviour 24

Utility maximisation 25Stable preferences 26Optimal information 26

Undermining the model of rational consumers 28When the rational model does not apply 29

Part II: Defining the market 31Geographic market definition 31

How it is currently done 31The end of geography? 32Van Thunen Circles 32Internet market definition 32Matrix of key questions 33

Contents

The consumer guide to competition: A practical handbook

Product market definition 33How it is currently done 33Substitutability 33

What’s needed: Time in substitutability assessments 34Working time into assessments 35

Demand-side complementarities 36Supply side substitution 37

Part III: Calculating market shares 38How it is currently done 38Doing the sums 38Step down differences between market shares 40Temporal aspects to concentration 41What’s needed: Impact of external trade 41Problems with indices 42

Part IV: Assessing vertically integrated markets 43How it is currently done 43Two-stage process 44Tying 45

Part V: Mitigating factors in assessments of market power 46How it is currently done 46Countervailing power 47Technological innovation 48

Part VI: Barriers to entry, establishment and exit 49How it is currently done 49Barriers to entry 49Structural barriers and market entry 52Barriers to establishment 52

Part VII: Strategic behaviour 52How it is currently done 52Bertrand or cournot? 53Predatory pricing 54Fighting brands, fighting ships and reputation 55The chain store paradox and signalling 55

Part VIII: Aiming for workable competition 56

Section 3: Consumers and regulation 57

Part I: Regulation: What it is, why it has grown 58What exactly is regulation? 58Why regulation has grown 59

Part II: Regulation and market failure 61Why regulation should happen 61

4

Contents

Part III: Why regulation happens 63Why regulation does happen 63Theory of regulation: Stigler-Peltzman 63Role of interest groups 64Watching out for the bootleggers 66

Part IV: Government failure, regulators and regulation 67Government failure and the role of regulators 67Identifying government failure 68Comparing market with non-market failure 70

Part V: Getting regulation to work for consumers 72When will regulation be successful? 72Attempts at reforming regulation 74

Section 4: Conclusions 77

Targets for regulation 80The process for regulating in normal markets 80Who can best deal with the spillover effects? 81How will improved efficiency and redistribution affect rent seeking? 81

Appendices 83

Appendix I: Behaviour, structure, strategy/conduct, performance, policy 84

Appendix II: Hints on decision-making and the analytical approach 85

Appendix III: Possible errors in market assessments 86

Appendix IV : Factoring in consumer behaviour 87

Appendix V: Structure-conduct-performance paradigm 90

Endnotes 91

What is Consumers International? 95

5

“Chaos, illumined by flashes of lightning”– Oscar Wilde on Robert Browning’s style 1

The analysis of markets is not an exactscience but a combination of evidence-based research and analytical interpretation.This handbook does not aim to provide anexact roadmap of ‘how-to’ proportions butto describe the parameters of thinkinggenerally contained in market structureanalyses and competition investigations.More importantly, this handbook aims toindicate the range of issues that competitionanalysis can cover and point out potentialproblem areas for those of us involved inrepresenting the consumer interest incompetition cases.

In addition to providing a guide to competitionpolicy investigations, this handbook alsosuggests improvements to the existingmethodologies in the area of consumerbehaviour, plus new approaches in geographicmarket definition and substitutability.

Incorporation of consumer behaviour morefirmly into the assessment of competition cases focuses on developing a matrix ofindicators to assess the degree to which theimplicit model of consumer behaviour willhold true. The key problem here is the scarcityof hard and fast indicators of consumerbehaviour other than ones derived from actual purchasing behaviour. As a result, theindicators we propose are more aboutidentifying barriers to consumer rationalitythan indicating the degree of that irrationalityitself. The advantage of this approach is that itallows the pinpointing of specific barriers torationality in individual markets and gives

6

structure to assessments both of competitionproblems and the likely success of regulatorysolutions.

The additions we recommend in the definitionof relevant geographic markets are also relatedto the ways consumers behave within normallydefined geographic markets. Establishedmethodologies generally use proxy indicatorsand measures of substitutability in the marketas guides to defining the market. We are notproposing to scrap those indicators but tocomplement them with more consumer-focusedones. In particular, we recommend additionalmeasurements of consumer mobility andpurchasing behaviour within markets toascertain the degree to which consumers define their own geographic markets.

We also propose several ways forward toincorporate the development of e-commerceinto geographic market definition. We argue for the use of data about Internet usage byconsumers that is tied to an understanding ofthe distribution of consumers within themarket. This will help pinpoint the potential for e-commerce to have an effect on off-lineretailers and suppliers.

In the field of substitutability analysis, wepropose a series of indicators to gauge thelikelihood that consumers will invest time inseeking substitutes. The measures are similar inscope to those used in defining the role of theconsumer in competition investigations.However, they are more capable of having realdata tied to them and are more explicit aboutthe judgmental weightings built into the overallscale. Again, the aim is not to supplantestablished methodology but to supplementestablished methods with consumer-focusedindicators.

Assessing assumptions

No one comes to the topic of competitionwithout a host of prejudices and historicalbaggage, and assessment of markets rests on anumber of these views. Aside from theestablished rules of economics and lessons fromthe study of markets, the followingassumptions make a useful starting point:

The consumer guide to competition: A practical handbook

Introduction

Introduction

7

Markets exist only because of consumers

Consumption is the sole end and purpose ofproduction, and the interest of the producerought to be attended to only so far as it may benecessary for promoting that of the consumer. –Adam Smith 2

We sometimes forget that the market is only inexistence because of the consumer. Thedefinitions of markets tend to focus on thefirms that operate in them. If we think ofmarkets in this way we miss the centrality ofthe consumer to understanding how the marketfunctions. We also end up with regulatorysolutions that favour businesses overconsumers and aid collusion and abuse ofcompetition.

Competition operates in the real world

The social object of skilled investment should beto defeat the dark forces of time and ignorancewhich envelop our future – John Maynard Keynes 3

You can’t step twice into the same river –Heraclitus

We must subscribe to the post-Keynesian viewof the world:

• Economic and political institutions are notnegligible

• The economy is a process in historical (real) time

• In a world where uncertainty and surprisesare unavoidable, expectations have anunavoidable and significant effect oneconomic outcomes.4

Markets are complex and operate in real time.Any assessment of a market must take accountof this and not rely on simple snapshots orstatic views of competition.

There is more collusion in ordinarymarkets than most people presume

Adam Smith argued that '(p)eople of the sametrade seldom meet together, even for merrimentand diversion, but the conversation ends in a

conspiracy against the public, or in somecontrivance to raise prices.’ 5

Many consumers and regulators like to thinkthat the natural state of markets is competition.In fact, the natural state of markets is morelikely to be collusive. The desire of companiesand their managers to have a 'quiet life'encourages collusion and underminescompetition. This is not to say that allindustries are riddled with anti-competitivebehaviour – some are, and some are not.However, it does indicate that there are manymore abuses of competition and consumersthan most people would expect.

Government is not blamelessThere used to be essentially two views on thesource of monopoly power.6 These views weredivided into:

• self-sufficiency: firms gain monopoly powerunder their own steam:

• interventionist: monopoly power is accruedas a result of government intervention or failure.

In the real world, it is unlikely that either viewwill always be correct. In most cases, theaccrual of monopoly power will arise from aninteraction of the two sources.

Established approaches only tellpart of the storyCompetition regulation tends to analyse firmsin markets and has less experience in dealingwith consumers in markets. Inability to factorreal consumer behaviour into analysis will limitresponses to cases, reduce the ability to proposereal solutions and hamper the recognition of‘emergent properties’ in markets that a holisticview of a market will provide.

Competition is not an end in itself

Cecil Graham: What is a cynic?Lord Darlington: A man who knows the price ofeverything and the value of nothing.– Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892)

While the study of markets and promotion ofcompetition are important exercises, it must beremembered that the object of the market is not

The consumer guide to competition: A practical handbook

8

competition. We must raise our eyes from theworkings of the market to really see what sortof world we want to live in.

Markets are good at providingallocative efficiency, notdistributional equityCompetition analysis and investigations aregood for improving allocative efficiency but notfor dealing with distributional equity. It is quitedangerous to confuse the two targets.

Allocative efficiency, or Paretoefficiency/optimality, occurs when it is notpossible for anyone to be made better offwithout making someone else worse off. Paretoefficiency can be seen in conjunction with aNash equilibrium. A Nash equilibrium occurswhen a firm aims for profit maximisation at thesame time as competing firms, and means thatno firm can gain by changing its strategy fromthe one it has independently chosen.

Distributional equity is a broader social concerndriven by a desire to strive towards whatTobin7 has called 'specific egalitarianism'. Thisis the concern to ensure that distribution of aresource or service is done in a manner that isless unequal than the simple ability-to-paysolution would provide for. A distributionalequity solution may involve measures outsideand beyond the assessment of allocativeefficiency. As we discuss below, the decision-making process should assess and aim for theallocative efficiency position before consideringwhat distributional impacts may be.

Raymond Carver, one of the finest Americanshort-story writers of the 20th century,produced a collection entitled “What Do WeTalk About When We Talk About Love?’ Thesame question can be asked aboutcompetition. Like love, we know competitionwhen we see it. But when we try to pin downexactly what it is, we find ourselves trippingover words and definitions. Like love,competition tends to be viewed in differentways by different people. This sectionoutlines what competition is, what it is notand what it might become. It also discussessome important distinctions betweencompetition, competition law, competitionpolicy and regulation.

At its most basic, competition is the process ofrivalry between firms and other suppliers forthe money and loyalty of customers over aperiod of time. The nature of this rivalrydepends to some degree on the structuresapparent in the marketplace and the historyand culture both of consumers and producersin that market. This rivalry tends to focus onone of two routes, or a combination thereof:

• Price-based competition: rivals compete tocut their costs and prices to catch theattention of customers.

• Service-based competition: rivals go beyondprice offers and offer differentiated serviceoffers. These may sometimes includeinnovations in product and service markets.

The package that the consumer sees in acompetitive market is a often combination ofthese two approaches.

10

The classic approach to competition stems fromAdam Smith’s notion that competition occurredwhen rivals acted in isolation from one another.Collusion would not generate competition.Following individual self-interest, whencollected together in a market, would generatethe best economic outcome. Smith’s focus onthe ‘Invisible Hand’ that guides individualactors in an economy to a wider end to whichthey had not strived has taken on almostmythical proportions in the modernunderstanding of markets.

Smith’s approach to competition was abehavioural one. Competition worked on thebasis of the behaviour of individual players inthat market and would be stymied by themonopolistic behaviour of those same players.The market was almost an exterior result ofindividual behaviours which none of theplayers aimed for but arrived at, courtesy of theInvisible Hand.

During the 19th century, a more structural viewof competition emerged. This approachgenerated the widely held view that a marketcould be defined as competitive when therewas a sufficiently large pool of sellers of ahomogenous (identical) product so that nosellers had a enough of a market share toenable them to influence product price byaltering the quantity they placed on the market.

The more structural approach of the 1930-40sled to the development of the Structure,Conduct, Performance approach to industrialorganisation. This approach marked a hugestep forward in the understanding of marketsand is still remarkably influential today.

The behavioural approach tends to be strongestamong the business community. It focuses onthe behaviour of firms and tends to argue thatif there is a competition problem, amending thebehaviour of firms within that market willdeliver results. The behaviouralist error focusesalmost exclusively on the appearance of rivalrypresented by businesses.

In contrast, the structural approach looksalmost exclusively at the market structure andassumes a deterministic relationship between

Competition and competition policy

Part I: What iscompetition

structure, conduct and performance. It tends toargue that getting the structures right in themarket will drive behavioural changes.

The behavioural and structural approaches canlead to opposite errors in the analysis ofcompetition in a marketplace. Taking tooabsolutist a line in looking at markets in eithertradition can lead to the following errors:

• The behaviouralist error assumes that firms,left to their own devices, will tend towardscompetition. This is typified in the ChicagoSchool /Robert Bork approach to competitioninvestigation which rests on the implicitmoral superiority of capitalist enterprisesover government regulation. It assumes thatmarkets are best left to themselves and that ifthere is a breach of competition rules,behavioural remedies are best – simplydirecting the firms to their previous narrowpath of competitive virtue. This type of errorpredisposes the proponent to leave marketsalone for too long.

• The structuralist error assumes that allbehaviour in markets is driven by thestructure in that market. This tends to leadproponents to a reductionist, deterministicapproach that assumes that all you have todo is get the structures right (e.g.: wherethere are few firms, they must be colludingand must be broken up) and the desiredbehaviour will follow. This type of errorleads to a more intrusive regulatory approachto competition problems.

The two errors tie rather neatly into FMScherer’s acute observation, as described in hisclassic textbook8, about the difference betweenrivalry and competition. He defines rivalry asthe process by which business peopleconsciously jockey for position against rivalfirms. This, he argues, is often defined by thosebusiness people as competition. However, youcan have rivalry without vigorous competitionand competition without rivalry (e.g. oncommodity trading systems).

This distinction between rivalry andcompetition is an important and useful one forconsumer organisations. We are often faced

11

with markets where firms maintain that theyare competing vigorously for consumers’money, whereas we sense that the market is notworking as well as it could in the interest ofconsumers.

Part I: What is competition

Competition and competition policy

The process of competition and itsmanifestation in rivalry between firmsdelivers a number of things in thosemarkets where it is strong. The effects ofcompetition can be generally grouped intotwo broad areas: those directly relevant forconsumers and those indirectly relevant for consumers.

Direct gains

It is always more straightforward to prove thedisadvantages for consumers where there is nocompetition than it is to prove how good it isfor consumers when competition exists. This isfor a number of reasons, most notably thatwhen measuring the impact of the blocking of amerger, or the liberalisation of a market it isalmost impossible to separate out each of thepossible reasons for a change in pricing orchoice. There are always ‘other factors’ thatcome into play. However, there are somegeneral things that can be said to flow directlyfrom competition.

Lower pricesThe greater the competition within a market,the more likely vigorous price competition willoccur. In contrast, monopolists’ only incentiveis to keep prices high. This poses afundamental problem for consumers in dealingwith pricing, a problem that rests on whetheryou can tell from price alone whether a marketis competitive or not.

Economic theory tends to argue that in aperfectly competitive market, prices will bedriven as near as possible to marginal cost. Inmost national markets, this will likely lead to

12

Part II: What competitiondoes

harmonised prices. At the same time, a marketrun by a cartel, or in which there is price-fixingor collusion, will also tend toward a singleprice. The conundrum for consumerorganisations is whether this single price isevidence of near-perfect competition or near-absolute lack of competition. The answer to thisconundrum requires steering a path betweenthe behavioural/structural errors outlinedabove.

Looking for collusionWhile there are no cast-iron pointers to guidethe consumer activist, the following signs maypoint to collusion:

• What opportunities does the industry haveto meet and discuss prices and output? If there is a strong industry lobby group,regular conferences and regular closedmeetings, the industry has the opportunity toengage in anti-competitive behaviour moreeasily than an industry without suchopportunities. It is a lot easier to create a cartelat the fringes of a regular industry meeting orconference than to organise a stand-alonegroup that has to be established specifically for the task.

• Does the industry tend to speak with thesame voice? In a highly competitive market, it is rare that allplayers will have the same view of an issue.While there will be many common issues onwhich they may agree (e.g. levels of taxation orregulatory burdens), beware of the industry inwhich there appears to be one voice only. Thispoints to an industry where the culture is oneof co-operation, not competition.

• How much price and cost signalling is there? Collusion is easier if you know your rivals’prices and costs. Look at the market and seehow easy it is for firms to see each other’sprices and understand each other’s costs. Forexample, in petroleum retailing, most firms aretotally vertically integrated and the productthey deal with is pretty much identical. Eachfirm thus knows that its own costs are unlikelyto be significantly different to its rivals. Thenature of retailing in this oligopoly marketmeans that each firm knows its rivals’ pricesand has a fair understanding of their costs.

Part II: What competition does

13

show that prospective competition (as proxiedby the number of years remaining toliberalisation) and effective competition (asproxied by the share of new entrants or by thenumber of competitors) both bring aboutproductivity and quality improvements andreduce the prices of all the telecommunicationsservices considered in the analysis. No clearevidence could be found concerning the effectson performance of the ownership structure ofthe industry (as proxied by both the publicshare in the PTO and years remaining toprivatisation). Severin Borenstein, Nancy Rose.Competition and Price Dispersion in the U.S.Airline Industry. July 1991. NBER WorkingPaper No. W3785

The pattern of price dispersion that we find doesnot seem to be explained solely by costdifferences. Dispersion is higher on morecompetitive routes, possibly reflecting a patternof discrimination against customers who are lesswilling to switch to alternative flights or airlines.We argue that the data support an explanationbased on theories of price discrimination inmonopolistically competitive industries.

Eric Kodjo Ralph, Jens Ludwig. Competitionand Telephone Penetration: An InternationalStatistical Comparison. By using the naturalexperiment in world telephony markets wherenations have chosen vastly different regulatoryregimes, this paper shows how competitionspurs telecommunications penetration. Further,we show that moving from two to three ormore firms is more important than movingfrom one to two, and that actual entry mattersmore than the threat of entry. This is ofeconomic as well as policy interest since game-theoretic models yield ambiguous predictionsabout oligopoly and monopoly when entry isthreatened.

Aaron S Edlin. Do Guaranteed-Low-PricePolicies Guarantee High Prices, and CanAntitrust Rise to the Challenge? Harvard LawReview, Vol. 111, No. 2, December 1997.

This article argues that there is an analogybetween a seller offering (and agreeing) tomatch a price for a buyer and other buyer-selleragreements that violate the Sherman Act. Thisarticle also considers a wholly new avenue for

Firms can estimate margins and the ability ofits rivals to engage in different levels of pricecompetition. If each player in a tight oligopolymarket knows price, costs and long runmargins, competition on price is extremelyunlikely.

What experience has taught usThe positive price effects of competition areenormously important. For consumerorganisations in some nations, competition maybe seen as a luxury or as a tool for the middleclasses. In other nations, consumerorganisations may ask: “What does competitionpolicy mean to a consumer living on less than adollar a day?” The simple answer lies in beingable to stretch that dollar further and havinggreater choice in where that dollar is spent.Turn the question around, and it is even easierto understand: “What good is a monopoly to aconsumer living on less than a dollar a day?”

Prices matter: they matter most for those withthe least to spend. An interest in driving pricesdown through competition is an interest sharedby all consumers. If competition can drivedown prices, then we must look to the policymix that helps deliver competition. The mixwill include reducing barriers to entry inmarkets (through trade liberalisation, removingrestrictive regulations and getting governmentsout of some markets) as well as rules to stopcompanies from simply controlling a market fortheir own benefit. Competition is not created bycompetition policy but competition policy canprotect competition once it occurs.

EVIDENCE FILE No. �

Oliver Boylaud, Giuseppe Nicoletti. OECDEconomics Department. Regulation, MarketStructure and Performance inTelecommunications Economics Department.April 21, 2000. OECD Economics DepartmentWorking Paper No. 237

Controlling for technology developments anddifferences in economic structure, panel data(long-distance (domestic and international) andmobile cellular telephony services in 23 OECDcountries over the 1991-1997 period) estimates

Competition and competition policy

attacking price matching, asking whether theprice discrimination involved in matchingviolates the unfair-competition or price-discrimination laws. In so doing, this articleexamines whether price matchers should beable to protect themselves from such an attackwith a "meeting competition" defence. Breakingwith conventional wisdom, this articleconcludes that the defence should be rejected in cases in which meeting competition maysignificantly injure competition among sellers.

More choiceThe other clear and obvious benefit ofcompetition is that it can generate more choice.Instead of the one monopoly supplier,consumers can choose from different options.For example, in the telephony market, thechoice for many years was a land-line, if youcould get one at all. This land-line tended to becontrolled by the national, government-ownedmonopoly. The arrival of competitors in land-line operations in many countries changed thisstate of affairs. However, the biggest shift in themarket has been driven by the arrival of mobiletelephony. This has not only provided morechoice but also helped open access to themarket for many more consumers than couldpreviously access a fixed land-line.

New entrantsA competitive market can trigger market entry.(Of course, market entry can be triggered byflabby monopolists.) The argument about entryreflects the idea that entry will only tend tooccur where a potential new player seesattractive margins being earned by existingplayers. Thus a lack of competition triggersentry. However, a firm entering a market canonly survive if it can compete with rivals. If themarket is sewn up through collusion orgovernment regulation, then the new entrantwill simply not survive.

What experience has taught usChoice is sometimes seen as some terribleproblem for the middle classes, but whereconsumers can exercise choice, we should beempowered to do so. Competition can deliverchoice at its most basic level. When a countrylike India effectively has only one make of carfor many years, consumers are denied choice.

14

But when other firms are allowed to compete,consumers have a choice. What’s more,innovation is driven into the sector, aspreviously dominant players have to fight forconsumer money. However, choice does notdeliver everything. In some markets, choice isdifficult either because the market is complexor because the market is made complex byexisting players to confuse consumers intosticking with the firms they recognise. Thereare real barriers to choice that must berecognised in drawing up regulations.

EVIDENCE FILE No. �

Mary W Sullivan. US Department of Justice.The Effect of the Big Eight Accounting FirmMergers on the Market for Audit Services.March 17, 2000. Working Paper No. EAG 00-2.The research assesses how the two Big Eightmergers of 1989 affected the market for auditservices. A data set of 1,978 firms over a 12-year period is used to test four theories of howthe mergers could have affected competitionand consumer welfare. The study finds that themergers reduced the marginal costs of auditinglarge clients. There is no evidence that themergers were anticompetitive or that theyreduced costs for all types of audit buyers.

Better serviceIt may seem a strange to argue that competitiondelivers better service. It helps to identify whatwe mean by service. For example, in theaviation market, service is generally defined toinclude frequency and punctuality as well asthe cup of tea or coffee. Back in the 1970s, priorto liberalisation, US airlines competed almostentirely on ‘service’ rather than prices (whichwere fixed). This led to such insane ‘service’offerings as in-flight cocktail piano bars andplayboy bunnies. Bloated fares and lack ofcompetition encouraged the airlines to wastemoney on gratuitous service ‘innovations’.

What experience has taught usMonopoly providers offer little choice and getlazy, which drives down service quality (e.g.Aeroflot in the 1970-80s) or encourages them toinvest huge amounts of money on excessivefrills (e.g. US airlines in the early 1970s). Either

Part II: What competition does

15

way, the consumer loses. Service quality tendsto improve when firms are forced to competewith other firms. Why would a monopolyprovider bother to provide a better servicewhen it knows it will not be punished if it does not?

Indirect gains

While the direct gains of competition arerelatively easy to identify, the indirect gains aremore difficult. However, the relationshipbetween the direct and indirect gains isimportant to investigate. Indirect gains throughenhanced efficiency, productivity and evenprofitability can result in even greater gains forconsumers. In a competitive market, therelationship between direct and indirect gainscan form a virtuous circle. In monopolisedmarkets, the opposite may be true: lack ofdirect gains for consumers can form a viciouscircle resulting in the destruction of efficiency,productivity and profitability that reduces thepossibility of future gains for consumers.

Efficiency and productivity gainsEfficiency and productivity gains for firms arenot usually viewed as being a benefit deliveredto consumers from competition. But whencertain conditions are met, such gains can forma virtuous circle of competition, efficiency andproductivity. When consumers choose betweenproducts on an individual basis, they signaltheir preferences. When these individualpreferences are aggregated together, firmsreceive a clear market signal of what consumerswant (and do not want) and what to produce.When a firm loses out, it is spurred on to findways to recapture consumer preferences eitherby cutting costs (to undercut their competitors),or by innovating and producing a betterproduct to recapture these preferences, or both.This constant need to capture consumerpreferences forces firms into a never-endingsearch for the productivity gains and efficiencyenhancements that will allow them to go one-up on their rivals.

This competition-productivity-efficiency drivecan bring about a situation where consumersbenefit from better service and lower priceswhile firms in the market see profit

enhancements. An example of this comes fromthe UK supermarket sector, where retail priceshave been declining steadily over recent yearsas profits have been rising. Consumers havebeen reaping a fair share of the benefits ofcompetition between the main players.

What experience has taught usThe indirect gains from competition may appearto be of secondary interest to consumers, butthey are of fundamental importance over thelong-term. More productive and efficient use ofresources helps an economy to develop morequickly and leads to a higher standards ofliving. (It does not, however, deal with issues ofincome distribution). More dynamic firms tendto innovate more and be more responsive totheir consumers. This triggers new products,new markets and new approaches to consumer-industry relations. Efficiency and productivitygains from competition are actually the mostimportant long-term benefit a consumer canreceive from competition.

EVIDENCE FILE No. �

Richard Disney, Jonathan Haskell, Ylva Heden.Restructuring and Productivity Growth in UKManufacturing. May 2000 CEPR DiscussionPaper No. 2463

We find that (a) 'external restructuring'accounts for 50% of labour productivity growthand 90% of TFP growth over the period; (b)much of the external restructuring effect comesfrom multi-establishment firms closing downpoorly-performing plants and opening high-performing new ones, and (c) externalcompetition is an important determinant ofinternal restructuring.

Francesco Trillas Jane, The Structure ofCorporate Ownership in Privatised Utilities.September 2002. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 3563

In the benchmark case where the governmentmaximizes privatisation proceeds, it is shownthat the optimal level of concentration increaseswith a tougher regulatory climate for investors.A more lenient regulatory regime increases thevalue of the commitment not to interfere

implicit in a more dispersed ownershipstructure. Deregulation (through increasingmonitoring costs) also pushes corporatestructure in the direction of more ownershipconcentration. When political objectives areadded to the analysis, it is shown that lobbyingwith managers induces levels of shareholderdispersion that are higher than in thebenchmark case. Collusion with largeshareholders, however, may yield higherconcentration levels than in the benchmark. Inthe case of managerial lobbying, the leniency ofthe regulatory climate does not have anyimpact on the equilibrium stake of the blockholder, and has a negative impact on thedifference between the political and thebenchmark outcomes.

Mariko Sakakibara, Michael E Porter.Competing at Home to Win Abroad: Evidencefrom Japanese Industry.

We find robust evidence that domestic rivalryhas a positive and significant relationship withtrade performance measured by world exportshare, particularly when R&D intensity revealsopportunities for dynamic improvement andinnovation. Conversely, trade protectionreduces export performance. These findingssupport the view that local competition, notmonopoly, collusion, or a sheltered homemarket, pressures dynamic improvement thatleads to international competitiveness.

Frank R Lichtenberg. Industrial De-Diversification and Its Consequences forProductivity. January 1990. Jerome LevyEconomics Institute Working Paper No. 35

Using plant-level Census Bureau data, we showthat productivity is inversely related to thedegree of diversification: holding constant thenumber of the parent firm's plants, the greaterthe number of industries in which the parentoperates, the lower the productivity of itsplants. Hence de-diversification is one of themeans by which recent takeovers havecontributed to U.S. productivity growth. Wealso find that the effectiveness of regulationsgoverning disclosure by companies of financialinformation for their industry segments waslow when they were introduced in the 1970sand has been declining ever since.

16

Michael Gort, Nakil Sung. Competition andProductivity Growth: The Case of the USTelephone Industry. Economic Inquiry.

Abstract: Both the estimation of total factor productivitygrowth and the analysis of cost shifts show amarkedly faster change in efficiency in theeffectively competitive market than for the localmonopolies. The results support, byimplication, a policy of permitting entry andcompetition in local telephone markets.

Jalana D Akhavein, Allan N Berger, David BHumphrey. The Effects of Megamergers onEfficiency and Prices: Evidence from a BankProfit Function. January 1997. FEDS PaperNumber 97-9.

We find that merged banks experience astatistically significant 16 percentage pointaverage increase in profit efficiency rank relativeto other large banks. Most of the improvement isfrom increasing revenues, including a shift inoutputs from securities to loans, a higher-valuedproduct. Improvements were greatest for thebanks with the lowest efficiencies prior tomerging, who therefore had the greatest capacityfor improvement. By comparison, the effects onprofits from merger-related changes in priceswere found to be very small.

Sumit K Majumdar. The Hidden Hand and theLicense Raj: An Evaluation of the RelationshipBetween Age and the Growth of Firms in India.Imperial College of Science, Technology andMedicine, Management School Forthcoming inJournal of Business Venturing

The evidence suggests that entrepreneurialbehaviour is an important feature ofcontemporary Indian industry. Recentanecdotes about Indian firms, particularly inthe information technology sector, suggest thatthere has been a resurgence of industrialactivity in the country. These beliefs are borneout by the analysis. The "hidden hand" is aliveand well in India! Additionally, the relationshipbetween size and the growth of Indian firms isnegative. This suggests that a process ofindustrial fragmentation may be taking place inIndian industry, with small firms growingfaster than larger firms and reducing the

Competition and competition policy

importance of large firms in Indian industry.This has important implications for the futurecompetitiveness of Indian industry.Allen N Berger, David B Humphrey. Bank ScaleEconomies, Mergers, Concentration, andEfficiency: The U.S. Experience

Scale and scope economies in banking are notfound to be important, except for the smallestbanks. X-efficiency, or managerial ability tocontrol costs, is of much greater magnitude – at least 20% of banking costs. Mergers have nosignificant predictable effect on efficiency –some mergers raise efficiency but others lowerit. Market concentration results in slightly lessfavourable prices for customers, but has littleeffect on profitability.

Allen N Berger, Timothy H Hannan. TheEfficiency Cost of Market Power in the BankingIndustry: A Test of the ‘Quiet Life’ and RelatedHypotheses.

We find the estimated efficiency cost ofconcentration to be several times larger thanthe social losses from mispricing astraditionally measured by the welfare triangle.

What about jobs?Employment and unemployment are majorconcerns in all countries. It is often argued inthe popular press that greater competitionleads to higher unemployment and worseemployment prospects for workers. This beliefis supported by the evidence of immediatepost-privatisation restructurings that oftencentre on job losses. Stories of job loss generallyreceive more coverage than stories of jobcreation. When a factory shuts down and athousand workers are laid off, it is not hard toidentify the immediate losers from the process.In contrast, having ten firms employ 100 extrapeople does not grab tomorrow’s headlines.The problem with the relationship betweencompetition and employment is that measuringdirect effects is complex. For example, when anew firm sets up shop and enters a market, theimmediate employment impact is positive. Inthe long run, however, that firm might displaceanother or force the rival firm to engage inefficiency measures that require it to cutemployment levels.

17

A basic argument about the relationshipbetween competition and employment comesfrom its obverse relationship. In monopolysituations, a share of monopoly power is oftenexercised by the employees. This can bebeneficial in terms of wages and workingconditions. The correlation between monopolypower (public or private) and restrictivepractices by workers is fairly close. It makesintuitive sense that when a firm has aprivileged position, its employees are able toextract greater benefits from that firm at alower cost to that firm, because the firm canpass on these additional costs on to itscustomers. Almost every nationalised postal,railway, utility and national airline companyhas faced this problem. We often find,particularly in developing countries, that thesefirms are akin to arms of the state designed toemploy large numbers of people as analternative to the welfare state.

The problem with workers extracting a share ofthe benefits from the monopoly firm is that ittends to be a short-term benefit which laterendangers the entire enterprise whencompetition is introduced. Sharing monopolyrents only works as long as there are monopolyrents to share. When firms lose money, themonopolist is left either to extract morerevenue from customers or from the taxpayerthrough the state. The subsidy afforded by thestate is thus shared between the monopolistand its employees.

When competition is introduced, the incumbentmonopolist tends to be lumbered with abloated cost base (as its monopoly positioninvited inefficiency and encouraged its workersto extract ever-higher wages at the expense ofconsumers). New entrants are not faced withthis legacy problem and can thus come in withsignificantly lower costs. The impact on theincumbents will vary by industry.

The immediate likely impact on employment isthus negative from competition. Determiningmedium to long-term impact, however, is moredifficult. Competition drives efficiency intoresource allocation. If investors find that capitalinvested in a monopolist comes under pressure,they will likely seek to invest that capital wherethe return is better. Loss of capital from a

Part II: What competition does

monopolist almost certainly means that anotherfirm or sector will benefit from increasedinvestment and will be better able to employ people.

What experience has taught usConsumer organisations have a real dilemmawith employment issues in competitionmatters, for diverse reasons. As concernedcitizenry with current or potential alliances toother groups that may benefit from maintainingthe status quo, it is easy for consumerorganisations to get drawn into protectionistarguments against competition. The high-profile nature of many deregulation initiativesand liberalisation efforts makes every job loss apolitical issue. It is always difficult to sitopposite people who will lose their jobs andargue that the move will lead to long-termgains and better employment prospects forothers. (As Keynes argued, in the long run weare all dead.) But the truth is that morecompetition, particularly among dominantincumbents, is good for the consumer, good forthe economy and good for employment.

EVIDENCE FILE No. �

Pietro F Peretto. Market Power, Growth andUnemployment. March 1998 Duke University,Economics Working Paper No. 98-16.

Labour market reforms that reduce the cost oflabour have effects in the product market thatreinforce the modern view that a morecompetitive labour market leads to lowerunemployment. This implies that such reformsare even more attractive than previouslythought. In agreement with the idea thatproduct market competition matters, moreover,I show that lower barriers to entry in theproduct market lead to lower unemployment.

Marianne Bertrand, Francis Kramarz. DoesEntry Regulation Hinder Job Creation? Evidencefrom the French Retail Industry. November 2001.CEPR Discussion Paper No. 3039

We show that stronger deterrence of entry bythe boards, and the increase in large retailchains' concentration it induced, slowed downemployment growth in France.

18

Michael C Burda. Product Market Regulationand Labour Market Outcomes: How CanDeregulation Create Jobs? January 2000. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 230.

A non-negligible component of the recentDutch employment miracle could be attributedto product market deregulation, in particularliberalization of shop-closing laws effected inthe mid-1990s. I sketch a model, based onBurda and Weil (1999), which can rationalizepotential public interest aspects of suchregulations as well as identify theiremployment and output costs.

Competition and competition policy

The case that competition is generally good forthe economic well-being of a country is astrong one. Similarly the argument thatcompetition damages workers’ rights is weak.Of greater interest is the relationship betweencompetition and competition policy. This mayseem an academic point, but it is also importantfor practical policymakers. If you want toencourage competition, what balance of toolsand policies are needed to achieve this end?

All advocates of competition and competitionlaw and policy recognise that these are only one element of the toolkit to foster a morecompetitive economy. Within the area ofregulation that we loosely refer to ascompetition policy, a range of policies existsaimed at diverse areas of activity. We can dividethese policies along the following continuum:

19

Competition law and policy take differentforms in different countries. Most countriesseek a phased approach to their development.Cartel rules and rules on price-fixing areusually the first to be brought in, followed byincreasingly tough rules on mergers andcollusive behaviour. (Most developed countries,for example, had fairly strong laws on cartels,and price fixing before they had firm rules onmergers.) Sectoral regulation only comes intoits own during deregulation efforts. Obviously,sectoral regulation rules were not thought ofbefore countries started to privatise their public utilities.

As the table on page 20 illustrates, the patternof adoption of different elements of acompetition regime can be done on a graduatedapproach. While competition advocates willdiffer about which element goes where, itprovides a useful typology for thinking abouthow countries new to competition enforcementshould deal with competition law and policy.

Part III: Impact of competition law and policy

Part III: Impact ofcompetition lawand policy

Area of activity Type of policy

Government-supplied services Monitoring, target setting, competitive neutrality with private sector

Public utilities Basic sectoral regulationIntroduction of competitorsCompetitive tendering

Privatised public utilities Sectoral regulation Competition regulation

Private firms acting individually Rules on anti-competitive behaviour, price fixing,abuse of dominance, predatory pricing

Private firms knowingly acting together Rules on market division, market sharing, price fixing, collusion on keeping others out, cartel formation

Private firms effectively acting together Oligopoly rules for firms that effectively do not compete, market review mechanisms to inject competition

Private firms merging Rules on mergers

If a country wishes to privatise a publiclyowned company, it must recognise that it ismoving from what is termed a ‘high trust’ formof regulation to a ‘low trust’ form of regulation.High-trust regulation assumes that thosecarrying out the activity have a wider remitand broader accountability to elected officials.Low-trust regulation assumes that the firm willbehave in a narrowly self-interested way (asprivate firms are supposed to). This move fromhigh-trust to low-trust demands sectoral andcompetition regulation. When privatising, wemust assume that the newly minted privatefirm will abuse whatever power it has.

What does experience tell us?Experience shows that the best way to dealwith this problem is to ensure as muchcompetition as possible before privatisation ofthe domestic monopoly. Once competition hasstarted to bite, additional liberalisation can beintroduced, provided it is followed by sectoralregulations to ensure that competition thrives.If privatisations are not handled properly, theconsumer interest is undermined and serioussocial problems, including unrest, can occur.

Competition policy is flexible; no one-size-fits-all approach is possible. Countries can offeradvice and recommend reforms but theythemselves will be re-assessing on a permanentbasis how they conduct competition reforms.Competition policy is about getting the toolkitright to protect consumers and foster

20

competition, not about requiring countries to follow a rigid path to development.

EVIDENCE FILE No. �

George Symeonidis. Price Competition,Innovation and Profitability: Theory and UKEvidence. University of Essex – Department ofEconomics; Centre for Economic PolicyResearch (CEPR) May 2001. CEPR DiscussionPaper No. 2816

The econometric results suggest that theintroduction of restrictive practices legislationin the UK had no significant effect on thenumber of innovations commercialised inpreviously cartelised R&D-intensivemanufacturing industries, while it caused asignificant rise in concentration in theseindustries. In the short run profitabilitydecreased, but in the long run it was restoredthrough the rise in concentration.

Brian R Cheffins. Investor Sentiment andAntitrust Law as Determinants of CorporateOwnership Structure: The Great Merger Waveof 1897 to 1903. Faculty of Law, University ofCambridge.

One theme the paper develops is that mergersmatter with respect to the evolution of systemsof ownership and control. A second topic thepaper deals with is the process by which a

Competition and competition policy

Different stages of development for a national competition regime

Start Enhancement Advancement Maturity

Competition advocacy and Merger control Regulation Second generationpublic education international agreements

Control of horizontal Vertical restraints International Pro-active competitionrestraints co-operation advocacy

agreements

Checking abuse of Development ofdominance effects doctrine

Exceptions and exemptions, including on public interest grounds

Technical assistance

Source: Gesner Oliviera after Shyam Khemani and Mark Dutz. 1996. The Instruments of Competition Policy and their Relevance for Economic Development. PSD Occasional Paper No. 26. World Bank. Quoted in P Mehta. 2003. Friends of Competition. CUTS, Jaipur.

country's investors become sufficientlycomfortable owning publicly traded shares topermit a transition from concentrated todispersed share ownership. A third theme thepaper emphasizes is antitrust law's significance.The experience in the U.S. and Germanysuggests that the legal status of anti-competitive alliances is a potentially importantdeterminant of corporate ownership structures.

J Gregory Sidak, Michael K Block, F C Nold.The Deterrent Effect of Antitrust Enforcement.Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 89, No. 3, 1980.

We show that a cartel's optimal price is likely tobe neither the competitive price nor the pricethat the cartel would see in the absence ofantitrust enforcement but rather anintermediate price that depends on the levels ofantitrust enforcement efforts and penalties. Ourempirical results reveal that increasing antitrustenforcement in the presence of a credible threatof large damage awards has the deterrent effectof reducing mark-ups in the bread industry.

J Gregory Sidak. Rethinking AntitrustDamages. Stanford Law Review, Vol. 33, 1981.

Part I analyzes the consumer's economic injuryfrom exploitative behaviour and shows that,prevailing contrary opinion notwithstanding,the Clayton Act does not unambiguouslyestablish a consumer right to be free from suchinjury. Because the prevailing interpretationmay cause allocative inefficiency, Part Iproposes a countervailing producer's right anda corresponding damage rule. Part II analyzesthe kind of injury that competitors suffer fromexpansionary behaviour. It criticizes thecompetitor's right suggested by the currentdamage rule and proposes an alternative rightand damage rule that would improve socialwelfare by enhancing productive efficiency. PartIII proposes implementing the economic rightssuggested in Parts I and II through a judicialtest for calculating antitrust damages thatwould restrict the availability of such damages.

Bruce H Kobayashi. Antitrust, Agency andAmnesty: An Economic Analysis of theCriminal Enforcement of the Antitrust LawsAgainst Corporations. George Mason Law &Economics Research Paper No. 02-04.

21

Because criminal fines are not accuratemeasures of loss, and because of the vicariousnature of corporate liability, there is a greatdanger that higher-than-optimal penalties willinduce corporations to incur excessive costs inan attempt to avoid these high fines. Thepotential over deterrence costs resulting fromhigher-than-optimal fines is exaggerated by theAntitrust Division's expanded use of theCorporate Leniency Policy. Ironically, the costsof over deterrence will result in higher prices toconsumers, a decrease in welfare, and,ultimately, in the exact effects that the criminalantitrust laws are intended to prevent.

Margaret C Levenstein, Valerie Y Suslow. What Determines Cartel Success? University ofMichigan Business School Working Paper No. 02-001.

Our examination of cartel duration concludesthat cartels are neither short-lived nor long-lived; they are both. Similarly, our analysis ofthe effect of cartels on prices and profitabilityfinds that there is enormous variance in cartelsuccess at raising price to the joint-profitmaximizing level. In our examination of cartelbreakdowns we find, as suggested by recenttheoretical literature, that cheating is a commoncause. Occurring even more frequently,however, are entry, external shocks, andbargaining problems, suggesting that theseissues should be given deeper consideration infuture work. Stigler's hypothesis that largecustomers contribute to cartel breakdowns isborne out in a few case studies. But thereappear to be more cases in our sample in whichlarge customers help to stabilize the cartel.Only the oldest of suppositions, that highlyconcentrated industries are more prone tocartelisation, seems to hold true across studies.Our inability to find more commonality amongthese studies and among cartels does notsimply reflect our ignorance of carteloperations or secrecy on the part of cartels (orthe different methodological approachescovered in this survey). Rather, it reflects theinnumerable possibilities for organizing asuccessful cartel, and the interdependence ofthose factors determining cartel success.

Part III: Impact of competition law and policy

Increasingly, competition regulators mustface up to the difficulties of conductingmarket analysis in areas where consumerbehaviour is an important factor. This needis most immediately felt in the investigatoryphase, when regulators map the market.While the best regulators are attempting tounderstand how consumers behave in themarket, this has tended to proceed on anad-hoc basis largely based on the interest ofstaff and the willingness of panel membersto ensure its operation. However, theimportance of consumer behaviour must notbe underestimated in identifying possibleregulatory solutions to competitionproblems. It is here that an understanding of drivers for consumer behaviour isparticularly important.

This section identifies ways to assessconsumer behaviour in competitioninvestigations. It starts from thepresumption that optimal consumerbehaviour in a market is characterised byclassical economic theory. However, acombination of structural and behaviouralfactors hamper the ability of consumers toattain the model of rationality established inclassic economic theory. We thereforepresent a matrix of factors and a scale ofimportance to estimate the likelihood thatconsumers will conform to this rationalconsumer model. We hope these categoriesof effects will provide a guide for indicatorsof consumer behaviour to supplement themore established methods of marketinvestigation.

24

Why should we care?The behaviour of consumers in markets is oftenviewed as a ‘given’ in the analysis ofcompetition problems. Classically trainedeconomists have tended to view consumers asrational beings who will pursue the maximumbenefit to themselves in a selfish way. Themessages transmitted to the market from thisindividual behaviour will help direct resourcesin an efficient manner and help drive marketsto more efficient operation.

If competition investigations and analyses areconducted on the basis that consumers act in adetermined manner, such investigations willmake certain assumptions at both the front andback end of their deliberations. Thus, in theinvestigation phase, regulators may assume acertain pattern of behaviour corresponding towhat one would expect from a rational model ofconsumer behaviour. Similarly, at the final stageof investigation, regulators may assume thatconsumers will behave in a classically ‘rational’manner when remedies are introduced.However, two key questions must be asked:

• To what degree does consumer behaviourmatch the classical model?

• If it does not, what effect should this have on the manner in which markets are viewedand regulated?

Classical model of consumer behaviour

The classical model of consumer behaviourassumes that consumers do essentially threethings in making decisions: “All humanbehaviour can be viewed as involvingparticipants who [i] maximise their utility [ii]from a stable set of preferences and [iii]accumulate an optimum amount of informationand other inputs in a variety of markets.” 9

To a large extent, the degree to which theserules apply will indicate the degree to whichthe assumption of consumer rationality applies.For analytical purposes, we thus need to askthe degree to which each rule applies.

Three key caveats need to be placed on theclassical approach:

Consumers and competition

Part I: Markets andconsumerbehaviour

25

Part I: Markets and consumer behaviour

1 Bounded rationality: Human cognitiveabilities are not infinite. (We all have limitedcomputational skills and flawed memories.)

2 Bounded willpower: People often takeactions in the short term that they know to bein conflict with their own long-term interests.

3 Bounded self-interest: People generally care,or act as if they care, about others, evenstrangers, in some circumstances.10

Given these bounds on behaviour, we need toidentify the degree to which consumers act inthe classically rational manner. To do this, weneed to identify all the problems that get in theway of consumers making rational decisions.We can thus identify factors over which wehave little control and those that regulators and the operation of the market can affect.

Utility maximisationThe idea of the utility-maximising individual is key to the classical view of consumerbehaviour. However, it is also one of theweakest links in the chain of argument thatseeks to place consumers within the rationalchoice model. A number of important caveatsmust be placed on the idea that consumerspursue a utility-maximising approach. Theseinclude cultural and peer group issues andmore basic structural processing issues on thepart of individuals.

The following factors can limit the operation ofa utility-maximising consumer.

Cultural aspects to decision-makingConsumers do not behave in a vacuum in anygiven market; their behaviour is circumscribedby their own cultural norms and thoseprevalent in the market. A clear understandingis needed of a market culture and the degree towhich the consumer can operate comfortablywithin it.

Tests:

• What is the culture of the market in question?• In what sub-culture does the market sit?• How will changes to that market affect the

cultural interactions of participants?

The endowment effect: Any product that is already part of theindividual consumer’s existing endowment

will be more highly regarded than a productthat is not. Individuals tend to rate what theyalready own higher than products that they donot own.

Tests:

• Proxy measures may include markets withheavy advertising budgets and campaignsaimed at boosting ‘new’ features to existingproducts. This may spill over into misleadingand deceitful advertising.

• Pressure advertising/marketing may be a problem

Sunk costs and the momentum theory The momentum theory argues that individualswill complete a task once work has begun,irrespective of the continuing validity of theoriginal decision. A sunk cost is an already-borne cost that is not easily recoverable.Individual sunk costs do affect decision-making.

Tests:

Is this a market where:• sunk costs are common, and legitimately so?• final decisions are arrived at over time?• consumers are required or encouraged to pay

for goods over time?• the final quality of work is only ascertainable

long after payment?• consumers have little opportunity to revisit

original decisions?

Psychic costs of regretPresent decisions may be affected whenindividuals feel unable to trust themselves tomake correct decisions in the future.

Tests:

• Is there a mismatch between ‘objective’measures of consumer need and ‘subjective’assessments?

• Is there a need for compulsion in markets?(e.g. health insurance)

• Is the market one that attracts lower incomeconsumers through its ability to discountlong-term fallibility in decision-making? (e.g.Christmas Clubs)

• Is this business proposition risky enough towarrant higher charges, opaque charginginformation or high credit charges?

• Will comparative information limit thepotential for abuse?

26

• What sources of information are available toenable decisions to be made?

• How accurate is information about products/services that incorporate losses (investmentproduct) and gains (M&S voucher)?

Stable preferencesThe idea that consumers make decisions from afoundation of stable preferences can beundermined by many factors, including thoserelated to the risk and perceived risk of adecision and the cost of getting a decisionwrong. The key difficulty, in analytical terms, ofidentifying factors in the operation ofpreferences is the close link between thosepreferences and the idea of utilitymaximisation. Many factors in consumerbehaviour that undermine the idea of theutility-maximising individual also underminethe idea that consumers operate from a set ofstable preferences.

The operation of a stable set of preferences canalso be undermined by the nature ofconsumption behaviour. For example, if theconsumers purchase a service or product thatrequires them to use an intermediary foradvice, the preferences of the sellers will be asimportant as those of the consumers. Similarly,the transparency of the transaction will beimportant, as will the degree to which theproduct and/or service are bundled in apackage whose individual parts are difficult toidentify and accurately price.

Optimal informationMuch work has been carried out on theproblems of information transmission inmarkets. The role of information economics hasgrown over recent decades in response to theproblems faced by regulators in liberalisingmarkets and by companies operating incomplex markets. The 'common understanding'reached is that information acts as a grease toeffective markets and the more information thatcan be made available, the more effective thisgrease will be. Unfortunately, the ability ofconsumers to compute the information theyreceive cannot match the desire of regulatorsand companies to furnish that information. Asa result, information can actually limit theeffective operation of a market, or make itslower to react to market mechanisms.

Consumers and competition

Self-control and pre-commitmentConsumers often recognise that their existingconsumption patterns are incapable of meetingcertain future needs (e.g. Christmas spending,retirement). This prompts saving and tying theconsumer into patterns of committedexpenditure.

Tests:

• Is this a market where regular payments forfuture goods are commonplace?

• How does the decision-effect-feedback loopwork in this market?

• How clear to the consumers are the costs of gradualism?

• How independent is the informationavailable to the consumer about the decision-effect-feedback loop?

Losses and gains treated differentlyBecause losses and gains are treated differently,we need to have an understanding of how themarket in question treats losses and gains inmarketing and product/service provision.

Options for dealing with combinations of losses and gains:

• Segregate gains: Individuals prefer to treatmultiple gains as a series of individual gains.(e.g. two gifts wrapped separately arepreferable to two gifts in a single wrapping).

• Integrate losses: Individuals like to place alltheir losses in one basket.

• Let big gains cancel small losses: If theoverall balance of gains and losses is positive,losses should be pooled with the gains tocancel them out.

• Segregate ‘silver linings’: When large lossesout-weigh small gains, gains may beseparated out as a ‘silver lining’ to the cloudof the large loss.

• The picture becomes less clear when dealingwith smaller gains and losses. Here,integration may be the preferred option.

Tests:

• What opportunity exists in the market forconsumers to bundle and re-bundle lossesand gains?

• How clear is the quality/price information inbundled products/services? Can objectivecalculations be made of relativecosts/benefits?

27

Part I: Markets and consumer behaviour

The following are constraints on the optimalacquisition of information by consumers:

Framing and informationThe quality of information available to theconsumer is key. However, the importance of thedecision and the time the consumer will/willnot want to allot to the decision cannot beunderestimated. Markets with low levels ofclarity in information and time investment mayforce consumers to make irrational or incorrectdecisions, or no decisions at all. Solutions insuch markets are unlikely to centre on moreinformation. Solutions may range from lessinformation to clearer information,benchmarking and basic product design.

Problems are presented to consumer in two ways:

• Transparent: Choice behaviour does notviolate basic tenets of rationality.

• Opaque: People may well violate basicprinciples.

Tests for transparency of information:

• How transparent/opaque is the informationpresented to the consumer?

• In what environment does the consumermake the decision?

• How much time does the consumer have tomake the decision?

• What other sources of information areavailable to the consumer to make adecision?

• What effect will a merger/behaviour have onthe transparency/opacity of information?

The structure of a problem The way in which a problem is presented to theconsumer may affect the choices made.Prospect Theory tells us that the same problempresented in different ways may influence thedecisions taken.

Tests:

• How many ways is the information in themarket presented?

• How uniform is the presentation of marketinformation?

• How much time will the consumer need toinvest before a decision is made and howmuch gain will the consumer get from that decision?

• How will the consumer make a cost-benefitanalysis in the market?

How consumers learnMarkets with limited learning opportunitiescontain a number of incentives to abuse marketpower and consumers (e.g. investmentmanagers making decisions whose effects willnot be uncovered for decades). While somemarkets have limited opportunity for learning,others try to limit learning for reasons ofcontrol (e.g. many insurance and investmentproducts, travel agents). Consumers needsufficient, clear information to learn. Solutionsin markets where this is not the case mayinclude information requirements and clearupdates on long-term decisions.

Necessary feedback on decisions is oftenlacking because:

• Outcomes are delayed and not easilyattributable to a specific action.

• Variability in the environment degrades thereliability of the feedback, especially whereoutcomes of low probability are involved.

• There is no information about what theoutcome would have been if another decisionhad been taken.

• Most important decisions are unique andtherefore provide little opportunity forlearning.

• Outcomes received with certainty are over-weighted compared to outcomes that areuncertain.

• Gains are treated differently to losses. Lossesgenerate a risk-seeking response while gainsproduce a risk-adverse response.

Tests:

Delay and variability• How long does it take before a consumer

understands the effect of a consumptiondecision? The obvious application here isfinancial services (e.g. credit cards vs.pensions). A rule of thumb: the longer thetime between decision and effect andfeedback, the weaker the potential foreffective competition.

• What is the transmission mechanism forinterpreting the decision-effect-feedbackloop? Who controls it?

• How easy is it to understand thetransmission mechanism and how accessibleis the information contained in it?

Uniqueness and alternatives• How often is the consumer in the market?• How many other decisions will the consumer

have made in the market?• Do any accurate proxy measures exist in the

market for the consumer to rely upon?

Time and importance• How important is the decision-effect-

feedback to the consumer?• What other decisions-effect-feedback loops

will the consumer be dealing with during asimilar time frame?

• Will peer group pressure have any influenceon the seeking/acceptance of information?

• How are consumers likely to value the time needed to interpret the transmissionresults?

Over-weighting certainty• How certain is the relationship between

decision-effect-feedback? How much is theconsumption decision a bet (e.g. aninvestment) and how much a certainty (e.g. a tin of beans);

• What is the consumer understanding of thebalance of probabilities in the market?

• How clear is the information in the marketabout probabilities?

Gains and losses• Is the product/service a bundle?• How clear are the gains and losses in the

market?• Do consumers have the opportunity to

re-bundle gains and losses according topreference?

Search costs Any difference in price between goods is seenin relation to the total price of the goods. Thusconsumers will spend time searching for alower-priced television, but not for a tin ofbeans. This has greatest implications for substitutability assessments and for thepossibility of local monopolies.

28

Consumers and competition

Tests:

• How important is this consumer decisionrelative to the potential saving?

• What is the likely peer group view of thegains from shopping around?

• What is the consumer understanding of themarket within which they are shopping?

• What are the physical bounds of the market?• How long will a consumer normally shop

around for in this market?• Are impediments placed in the way of a

consumer to limit the ability to find searchinformation?

• Do stores stock products that makecomparison shopping easier?

• How much of the market is migrating to the Internet, both in consumer and retailer terms?

Undermining the model ofrational consumers

Competition analysis is replete with indicesand mathematical calculations. These measuresall relate to the structural characteristics of themarket while tending to skate over theelements that relate more directly to consumerbehaviour. Attempts to bring more cohesion tounderstanding consumer behaviour in a marketare prone to the same difficulties seen in tryingto uncover strategic behaviour by companies.Pointers and proxy measures are thus useful inindicating certain patterns for assessing thedegree to which consumers will behave in aclassically rational manner.

The factors outlined in the matrix discussedbelow attempt to identify barriers to rationality.Given the scale and identification of problems,they can only be used as a rule-of-thumb guideto assessing markets. The advantage of usingsuch rules-of-thumb rests primarily on theability to identify those individual barriers andcombinations of barriers, which will hamperthe effective operation of consumers in amarket. As such, they may help to framesolutions or contribute to the assessment ofproposed policies.

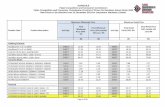

Matrix of factors hindering consumerrationality

Scale: 1=low, 2=medium, 3=high

How likely is it that consumers will maximise utility?

Length of time for the decision process to be made

Cost of searchThe opportunity cost of the decision

Cost to revisit a decisionCost to revise the decision

Sub-total for utility maximisation

How stable are consumer preferences likely to be?

Cost of getting decision wrongNumber of people involved in decision

Risk involved in the decisionBundling of other products/services to choice

Sub-total for stable consumer preferences

How good will the information be?Length of time post-decision to see effect

Volume of information requiredBackground information needs

Diversity of information presentationDecision feedback time

Likelihood not in the market againLikelihood not in related markets again

Likelihood proxy measures of performance not available

Sub-total for optimal information

Overall totalLikelihood that rational consumer model

will not apply

When the rational modeldoes not apply

The matrix for assessing the degree to which therational consumer model applies can only act asa guide in assessment of markets and possibleregulatory or market behaviour. The matrixpresents both structural and behavioural aspectsof markets. The object of regulators/marketparticipants should be to move the marketcloser to the ideal type for consumer behaviourto become more rational. This would producelower scores for each market.

29

The matrix should also provide a useful tool forassessing the likely effects of remedies incompetition cases. The question here will be thedegree to which a merger or a remedy in acomplex monopoly case or regulatory decisionincreases or decreases the likelihood thatconsumers will act in a rational manner.

While use of this matrix provides rule-of-thumb assessments for factoring-in consumerbehaviour, this approach must be employed inconjunction with other tools for competitioninvestigations.

The role of the matrix will differ betweenmarkets where direct sector-specific regulationexists and markets where no such regulationexists. In the former, it helps point to specificremedies or structural/behavioural indicators.In the latter, it helps identify the need toaddress broader policy goals (e.g. informationprovision or development of proxymeasurements) to allow informationtransmission to work more effectively.

Worked examplesThe matrix of questions to be asked in a givenmarket is applied to a series of specificexamples below (see page 30). The marketschosen range from complex, to verticallyintegrated to relatively simple. The workedexamples test the relative application of the matrix.

Totals represent the sum of each score; theestimation of the applicability of the rationalconsumer model reflects the degree to whichthe total score relates to the 'worst case' market(where all questions receive a 3 rating). In orderto maintain consistency in the application ofthe scale, some questions are presented the'wrong way round'. This keeps the scale andrankings relatively unsullied. (Please note,however, that a degree of bias in the estimationof scale is unavoidable, particularly when it issubjective.)

Part I: Markets and consumer behaviour

30

Consumers and competition

Worked examples of rational consumer matrix

Ideal Pension Cars Holiday Tin of beansmarket

How likely is it that consumers will maximise utility?Length of time for the decision process to be made 1 3 2 2 1Cost of search 1 3 3 2 1The opportunity cost of the decision 1 2 2 2 1Cost to revisit a decision 1 3 3 1 2Cost to revise the decision 1 3 3 1 2Sub-total for utility maximisation 5 14 13 8 7

How stable are consumer preferences likely to be?Cost of getting decision wrong 1 3 3 2 1Number of people involved in decision 1 2 2 2 1Risk of the decision 1 3 2 3 1Bundling of other products/services to choice 1 2 1 3 1Sub-total for stable consumer preference 4 10 8 10 4

How good will the information be?Length of time post-decision to see effect 1 3 1 2 1Volume of information required 1 3 2 2 1Background information needs 1 3 2 2 1Diversity of information presentation 1 3 3 3 2Decision feedback time 1 3 1 3 1Likelihood not in the market again 1 3 2 2 1Likelihood not in related markets again 1 2 1 2 1Likelihood proxy measures of performance not available 1 2 1 3 1Sub-total for optimal information 8 22 13 19 9

Overall total 17 46 34 37 20Likelihood that model will not apply 90.20 66.67 72.55 39.22

Scale: 1=low 2=medium 3=high

Bounds: most likelihood that model will apply: 17most likelihood that model will not apply: 51

Defining the relevant market is acornerstone of competition investigations.Definitions have emerged from a learningprocess based more on organic evolutionthan on the development of hard and fastrules. While this provides endlessopportunities for interpretation, it doesafford some degree of flexibility in thesystem. We propose a set of additionalfactors to be taken into account in thedefinition of relevant markets. In thegeographic market analysis stage, weadvance a number of proxy measuresavailable to regulators to assess the degreeto which consumers define the geographicbounds of their own markets. We alsopropose a route to understanding thepotential impact of electronic commerce onthe operation of specific markets: thatregulators utilise market segmentation dataand consumer research work to identify thelikelihood of consumer groups transferringtheir purchasing behaviour to onlinemarketplaces.