THE ACADIA PERSPECTIVE I · who otherwise could not afford a national park experience. Looking...

Transcript of THE ACADIA PERSPECTIVE I · who otherwise could not afford a national park experience. Looking...

1Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

In the midst of summer, national parks area favored destination of millions of fami-lies, students, first-time campers, and

explorers. Parks give us a place to stretch ourminds, our spirits, and our bodies. We thinkof soaring mountains, roaming buffalo, desert-ed pueblo villages, the Atlantic Ocean crash-ing against obdurate granite, definingmoments from our American history—anabundance of experiences for all imaginations.

The legacy protected by our national parksshapes our understanding, our experience asAmericans. Last October I was fortunate tojoin National Park Service professionals andseveral park partners to watch a rough cutof the new Ken Burns documentary: TheNational Parks: America’s Best Idea. (Readmore about this series on page 12.) The doc-umentary reminded me that Acadia is big-ger than its 35,000 acres. It is not just onepark, in one state, created by and for onecommunity of people. Acadia is much biggerthan that. It is a gorgeous piece of our 85-million-acre national park system heritage, “acontinent wide and more than a century old.”

And that means that what Friends ofAcadia does—what our members do—ismuch bigger too.

When Friends of Acadia makes grants tothe park—more than $13 million since 1995—we show others what can be done to pro-tect and enhance our national park legacy.

When Friends and its members advocatefor full funding and sound management poli-cies for our national parks, we toss a stoneinto a magnificent pond creating ripplesthat spread out to affect all 85 million acres.

When Friends volunteers mobilize to getwork done in the park and communities –more than 100,000 volunteer hours donat-ed since 1995 with a paid-labor value wellover $1 million – they set an example of goodstewardship, taking their ownership respon-sibilities seriously.

And we need to do more. We will alwaysneed to do more to safeguard our heritage.

For instance, in Acadia:

• Over the past year, two federal agen-cies—separately—proposed erecting an80-foot pole and 100-foot pole on thesummit of Cadillac for communications.One agency has found an alternate loca-tion outside national park boundaries,the other proposal is still under research,with Friends of Acadia and othersencouraging location also outsideAcadia’s border.

• Despite a small increase in base fund-ing, the park remains underfunded andunderstaffed—by 20 people at least. In2003, a business plan for Acadia showedthat the park was underfunded by 53%,and the spending base has been erod-ing ever since.

• More than 130 parcels within Acadia’sboundaries remain in private owner-ship, unprotected and vulnerable todevelopment.

We have inherited a tremendous legacy inour national parks, a gift which comes witha responsibility. We must ensure that the nextgeneration has opportunities to hear the storyof their heritage and to experience theirnational parks—as they were preserved.

•This past year, a landowner proposeda large-scale eco-resort development on3,200 acres abutting the park on theSchoodic Peninsula, threatening ecolog-ical isolation and a permanent change tothe character of the communities, theregion, and the discovery experience ofvisiting Acadia at Schoodic.

Right now, we have once-in-a-lifetime oppor-tunities to affect the betterment of our parks:

• In 2016 the National Park Service, andAcadia, will celebrate their centennialanniversary. Plans for celebrating thismilestone include informed, creativethinking today to prepare for a soundsecond century of inspiration,

• Our national parks were recognized aseconomic generators and received eco-

nomic stimulus funding through theAmericans Recovery and ReinvestmentAct. Acadia is in line to receive more than$8 million, which will be put to workrepairing roads and facilities at theSchoodic Education and ResearchCenter and on MDI park roads.

• The Ken Burns documentary has thecapacity to reinvigorate Americans’involvement in the care of their her-itage protected by our national parks.

The contributions of Friends members pro-vide a model of inspired, committed stew-ardship. The ripples are moving out…

If you are not a member of Friends ofAcadia, you are welcome to join this inspiredcorps of park stewards.

—Marla O’Byrne

THE ACADIA PERSPECTIVE

President’s Column

Nor

een

Hog

an

2 Summer 2009

A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities

FEATURE ARTICLES

7 New Name, Same Great Trail Ian MarquisHistoric trail names and what they mean for you this summer

8 Acadia’s Island Rangers Stuart West and Chris WiebuschThe story behind the wardens of Acadia’s wild islands

10 Loon Lessons: Working Together to Learn More Ginny ReamsA look at the life and times of Loon 983-153-53

12 The National Parks: America’s Best Idea Marla S. O’ByrneInformation about the upcoming documentary by filmmaker Ken Burns

14 Reaching Out to My Generation Keith MillerReflections on the importance of national parks and our connection to them

16 The Cairns Society: A Guiding Force for the Next Generation of Friends Lili PewThe importance of the work being done by one special group of “friends”

ACTIVITIES/HIGHLIGHTS

5 Memorial—Harriette Mitchell

17 Updates

25 Advocacy Corner

26 Book Reviews

DEPARTMENTS

1 President’s Column The Acadia Perspective Marla S. O’Byrne

3 Superintendent’s View Shaping Stewards: Education at Acadia Sheridan Steele

6 Poem The Stone Canoe Christina Lovin

13 Special Person Mike Blaney Marla S. O’Byrne

27 Schoodic Committee The Future of the Rockefeller Building Garry Levin

28 Chairman’s Letter Celebrating All Our Friends Lili Pew

Summer 2009Volume 14 No.2

BOARD OF DIRECTORSLili Pew, Chair

Edward L. Samek, Vice ChairJoseph Murphy, TreasurerMichael Siklosi, Secretary

Emily BeckGail Clark

Andrew DavisJohn Fassak

Nathaniel FentonDebby Lash

Ed LipkinLiz Martinez

Barbara McLeodJoe Minutolo

Marla S. O’ByrneJack Russell

Howard SolomonNonie Sullivan

Christiaan van HeerdenSandy WalterBill Whitman

Dick WolfBill Zoellick

HONORARY TRUSTEESEleanor Ames

Robert and Anne BassEdward McCormick BlairCurtis and Patricia BlakeRobert and Sylvia Blake

Frederic A. Bourke Jr.Tristram and Ruth Colket

Shelby and Gale DavisDianna Emory

Frances FitzgeraldSheldon Goldthwait

Neva GoodwinPaul and Eileen Growald

John and Polly GuthPaul Haertel

Lee JuddJulia Merck

Gerrish and Phoebe MillikenGeorge J. and Heather Mitchell

Janneke NeilsonNancy Nimick

Jack PerkinsNancy Pyne

Louis RabineauNathaniel P. Reed

Ann R. RobertsDavid Rockefeller

Patricia ScullErwin Soule

Diana Davis SpencerBeth Straus

EMERITUS TRUSTEESW. Kent Olson

Charles R. Tyson Jr.

FRIENDS OF ACADIA STAFFTheresa Begley, Projects & Events Coordinator

Mary Boechat,Development AssistantSharon Broom, Development Officer

Sheree Castonguay, Accounting & Administrative AssociateStephanie Clement, Conservation Director

Lisa Horsch Clark, Director of DevelopmentIan Marquis, Communications Coordinator

Diana R. McDowell, Director of Finance & AdministrationMarla S. O’Byrne, President

Mike Staggs, Office Manager

Friends of Acadia Journal

3Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

When a senior at Mount DesertIsland (MDI) High School askedour chief of interpretation to

mentor her senior project in May, she hadno idea she was fulfilling a goal establishedwhen she was only three years old. Back in1992, park staff set the goal to provide everystudent in the local community with a parkexperience—before they graduated from highschool—that could lead to future engagementin parks. This student, who used park hik-ing trails to study the history of the island,had taken trips to the park in middle school.We met our goal, thanks to a solid founda-tion of education and interpretation at Acadia.

From the early days, when SuperintendentGeorge B. Dorr himself showed off the newnational monument to its first visitors, Acadiahas offered enthusiastic, knowledgeable parkguides. Ranger-guided trips here have takenmany forms— from naturalist-led car cara-vans and bicycle tours along rough islandroads, to 1930s sailboat trips from Bar Harborto the Schoodic Peninsula (complete with alobster dinner), to tidepool talks near OtterPoint as early as 1932.

Following in the footsteps of the earlyranger naturalists, today’s park interpretersprovide high-quality information services,walks, talks, school visits, teacher and com-munity workshops, exhibits, emerging tech-nology media, and publications to the park’svaried audiences. Interpreters now, as ever,are the storytellers. They help people connectto park features with the aim of elicitingappreciation and stewardship. The hikerinspired by the view from mountain tops wholearns about fragile alpine plants will stepmore carefully on summits. The student whounderstands the intricacies of tidepools can

see the connections between conserved lands,their own coastal communities, and the Gulfof Maine.

As they work to inspire visitors, park inter-preters constantly adapt to the changingneeds of their audiences. Twenty-one yearsago this fall, at the request of local teachers,park staff added curriculum-linked schoolprograms to the already rich program slatefor visitors. The goal, with one part-timeranger, was to invite all fourth- and sixth-grade classes on MDI to visit the park for aranger-guided program. Within two years,with outstanding community response, theMDI goal was met; an additional program forthird graders was added; and schools on off-shore islands began attending.

In 1992, with the advice, encouragement,and funding of the National Park Foundationand The Pew Charitable Trusts, the nextambitious target was set: to provide at leastone park experience to every student in sur-rounding communities by the time the stu-dent graduated from high school. In just threeyears, park staff developed a sixth-grade sci-ence program for Echo Lake Camp, createda park science video for all Maine secondaryschools, and updated curriculum goals andcreated new teacher guides and student mate-

rials for every park program. Seven years later,the science camp moved to the SchoodicEducation Research Center, where, as theSchoodic Education Adventure (SEA), it pro-vides opportunities for students from neigh-boring towns to experience Acadia firsthand.With the help of Friends of Acadia andL.L.Bean Kids in Acadia grants, SEA atten-dance has doubled, extending to studentswho otherwise could not afford a nationalpark experience.

Looking ahead to 2016—the centennial forboth Acadia National Park and the NationalPark Service (NPS)—we will set the bar evenhigher. To remain relevant to all Americans,the NPS must work harder than ever toengage families and young people directlyin the national parks. Along with high qual-ity, family-oriented programming, we mustuse emerging media and relevant techniquesto engage 21st-century visitors. To date, wehave established internships and youth intakeprograms for students and created blogs foryoung employees to post their experiences.Summer residencies for teachers help themtake the park back to their classrooms. Virtualtours, bus and carriage ride funding, andthe first statewide Junior Ranger program areall part of Interpretation 2009. And there’smore to come in the future.

Partners are helping park interpreters tosteadily advance on an ambitious 100thanniversary goal: by 2016, to reach every stu-dent in Maine with a park experience beforethey complete high school. For Acadia—andall of our national parks—to thrive, we mustensure that the next generation of advocatesand stewards will be in place to protect ourparks and green spaces. Our ongoing effortsin education and interpretation at Acadia willhelp us get there.

—Sheridan Steele

SHAPING STEWARDS: EDUCATION AT ACADIA

Pete

r Tr

aver

s

Superintendent’s View

Heart of the Matter

“The influence of such work travels far;and many, beholding it, will go hence as missionaries to extend it.”

—George Bucknam Dorr

4 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

Kind Words from Friends

Dear Friends,We admire all you do and try to visit

Acadia as often as possible. Thank you forbeing there for so many of us.

Sincerely, Julie Goetze

The Thrill of the Quest

Dear Friends,My family travels to Acadia a couple of

times each summer. I was doing a search ofevents in the area for our first trip of theseason at the end of June. The idea of a“challenge” or quest has absolutely delight-ed my 7 year old!

Thank you for organizing such a neatevent.

Stacie PepperdCharlestown, RI

Another Season of Good Grooming

Dear Friends of Acadia Winter TrailGrooming Volunteers,

In lieu of the cookies and hot toddies youdeserve, I am writing this letter to thank youfor your work on the trails over the courseof this fabulous winter!

I have thanked you in my mind every timeI snapped on my skis and headed out intomy favorite hills on smooth, even tracks.

I was amazed by how much you accom-plished within a couple days after everysnowfall. Not only did you take time out ofyour lives to do this work, but you did itaccording to the random timing of the storms:showing up at late, early, cold, dark, and crazyhours to climb on those machines.

Years ago, when there were only a fewgroomers, I sometimes prided myself onbeing the first person to break trail aroundthe Mountain, or around Witch Hole. Butnow I’m more into skiing than slogging, andit’s a blast to fly around all the trails at topspeed.

I know I speak for many people (and formost, if not all, of you) when I say that thesewinter outings are not just my recreation.They are my therapy, healthcare, and spiri-tual renewal.

Thank you for sharing your passion, yourenergy, and your time.

And thanks for making winter so muchfun! Happy spring!

Rebecca HunterBar Harbor and Sullivan

A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities

Friends of Acadia preserves, protects, and promotes stewardship of the outstanding

natural beauty, ecological vitality, and distinctive cultural resources of

Acadia National Park and surrounding communities for the inspiration and enjoyment of current and

future generations.

The Journal is published three times a year.Submissions are welcome.

Opinions expressed are the authors’.

You may write us at43 Cottage Street / PO Box 45

Bar Harbor, Maine 04609or contact us at207-288-3340800-625-0321

www.friendsofacadia.orgemail: [email protected]

EDITORIan Marquis

DESIGNPackard Judd Kaye

PHOTOGRAPHER AT LARGE Tom Blagden

PRINTINGPenmor Lithographers

PUBLISHERMarla S. O’Byrne

This Journal is printed on chlorine-process free, recycled, and recyclable stock using soy-based ink.

Summer 2009Volume 14 No.2

Notes from Friends

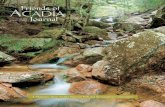

Pink granite in fog near summit of Penobscot Mountain.

Cover photograph by Tom Blagden

Friends received this drawing and note from Isaac Weaver, who attended this year’s Earth DayRoadside Clean-up with his mother and two sisters as one of their Acadia Quest activities.

5Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

A VOLUNTEER LEGACY

Harriette Mabel (Buzynski) Mitchell1920 – 2009

Harriette Mitchell, a friend and volunteer, died on June 6, 2009. She was bornHarriette Mabel Tillson on Sept. 17, 1920, in Thomaston, Maine, and moved toBar Harbor in the early 1960s. Harriette worked for many years at the Mount

Desert Island Hospital—she was the first registered ostomy nurse in Maine—and raisedher three boys, Neil, John, and David Buzynski, next to and in Acadia National Park.Harriette loved to hike, and when pressed, thought Canon Brook may have been her favoritetrail. But she also enjoyed the long hike from Bar Harbor to the Jordan Pond House forpopovers.

In addition to hiking, raising a family, and work, Harriette was a dedicated volunteer.Over the years, she volunteered with the Reach to Recovery program, Senior Companionprogram, Eastern Agency on Aging, the Abbe Museum, the Maine American Cancer Society,and Friends of Acadia. She traveled to Ecuador and the Dominican Republic with theHancock County Medical Mission.

Harriette was an intrepid volunteer for the park, as well. In the 1960s, she and a friendhiked all over MDI in search of native plants, with landowner permission, to divide andplant in a large blackberry patch at Sieur de Monts that was to become the Wild Gardensof Acadia. With buckets slung from a pole on their shoulders, the friends collected hun-dreds of plants for the gardens.

Many will remember Harriette at Take Pride in Acadia Day, where for nearly 20 yearsshe served lunch and dessert to cold and hungry Friends volunteers. And over the years,Harriette shared her knowledge of Acadia history, dropping in with an article and memo-ries of places and people in the park. Her son Neil recalls, “Mom was not only a friend ofAcadia, but a lover of Acadia. She knew of many places to go and see a special flower ortree that were on the trails and roads, but perhaps where others did not take the time tolook. Although she is out of sight, she will never be out of mind. She has left her footprintin one form or another in Acadia National Park.”

Harriette Mitchell left a rich legacy of active stewardship in Acadia, at the Wild Gardens,and with Friends.

MemorialIN MEMORIAMWe gratefully acknowledge gifts

received in memory of:John E. Ainsworth

Samuel David AmitinThe Bakalians

Matthew BaxterDaniel BazinetLucie Blasen

Wilmer BradburyBenjamin Breeze

Virginia Ann BrownGeorge H. BuckCharles E. Bybee

Carol S. CampbellDow L. Case

ChakraGregory Michael Colonis

Marilynn CoombsMarion G. Decker

Ray O. DeihlFrancis W. Dinsmore

Tucker ElliottPersifor FrazerRichard Frost

Jeannette GerbiGilbert Greene

Brenton S. Halsey, Jr.Irma Jantz

Betty S. JohnsonOlin Kettelkamp

Ilmars KnetsDavid Krieger

Joseph B. KrisandaWilliam Lawrence

Barbara K. LeeEric LindermayerMarlene Marburg

Robert McCormickMichelle

Elizabeth MondayRobert Palmer

Mary C. PhilbrickEunice Thompson Orr

George PutnamReona Pyzynski

David L. RabascaGordon RamsdellBayard H. RobertsArnold R. SchultzMarvin ShappiroJeanne B. SharpeClare F. Shepley

Hale Daniel SimonsRobert Smith

Charles A. SoderlundDavid StaintonJudith Steves

Richard G. TalpeyEileen M. Tateo-BeebeRobert Kinsey Taylor

February 1, 2009 – May 31, 2009

Harriette Mitchell (second from left) at Take Pride in Acadia Day, 2003. Also pictured (from left to right) areTerry Begley and Marla O’Byrne, FOA staff, and Nina Gormley, volunteer.

VOLUNTEER FIELD CREW LEADERSLen BerkowitzBruce BlakeBucky &

Maureen BrooksJenn Donaldson Rod FoxMike HaysHeidi HershbergerCookie HornerSteve JohnsonYvonne Johnson

ACADIA WINTER TRAILSASSOCIATION VOLUNTEERS

Dirck BradtPeter J. BrownMark FernaldGary FountainMatt GerrishMichael GilfillanPaul HaertelKarol Hagberg

OFFICE VOLUNTEERSFloy ErvinJeannie HowellEileen LinnaneMary Ann SiklosiJean SmithAnne Warner

ACADIA QUESTSponsor

L.L. Bean

EARTH DAYSponsors

Bar Harbor Bank & TrustThe FirstThe Knowles Company

In-Kind Donors Acadia Shops Hannaford SupermarketsGeddy’s RestaurantJack Russell’s Steakhouse and BreweryLeary’s Landing Irish PubROOT’s Trenton IGA

NATIONAL TRAILS DAYSponsors

Bar Harbor Bank & TrustThe FirstThe Knowles Company

In-Kind DonorsHannaford Supermarkets

6 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

The Stone Canoe

At

Pemaquid

it lay, resting

on its side, tossed

up by an epic storm.

Skipped across the wide

sea by some giant. Skiffed

upon a wave so great that stone

might float, come to rest, wrecked

and wedged between the earth-bound

boulders strewn below the salt-greened

bell of the signal house. Formation or

freak, or an accident of native granite

laid over in the sun to dry. Curved

beam, pointed prow, stone-solid

and unmovable. What memory

made me wish to push it to

the brink of cliff, climb

in with you, plummet

to the rocks below:

the dark and

savage

surf

?

—Christina Lovin

FRIENDS OF ACADIA POETRY AWARD

Honorable Mention

PoemIn Gratitude

Alan KingVesta KowalskiDon LenahanJim LinnaneMark & GeorgiaMunsellBesty Roberts Bob SandersonJulia SchlossHoward SolomonAl & Marilyn Wiberley

Bill JenkinsDavid KiefStephen LinscottH. Stanley MacDonaldRobert MassuccoDennis Smith Charlie Wray

7Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

Acadia Trails Forever

When hiking Acadia’s many trails,a map is a necessity. Starting thissummer, however, you may find

that the trail names on your map do notmatch the posted signs. Whatever is a hikerto do?

The simple answer: keep on hiking. Thetrails themselves have not changed, and intime, the maps will reflect the new names.But of course, that raises another question:why do some of the trails have new names?What was wrong with the old ones?

Historically, the trails in Acadia NationalPark were named for many reasons. Some,such as the Emery Path, honored people; oth-ers, like the Gorge Path and Great Notch Trail,reflected a particular landmark or nearby fea-ture; many bore the names of the mountainsthey ascended. But these names have neverbeen static; over the years, a considerablenumber of trails have been renamed, often tosomething entirely different than the origi-nal. Most visitors to the park, for example,are unaware that a section of the SouthBubble Trail was originally known as BubblesDivide, or that the portion of PenobscotMountain Trail running from the ridge east-ward, down the steep cliffs, was once calledthe Spring Trail. Many of these changesoccurred decades ago – long enough that vis-itors might feel a sense of loss when they findthat a familiar trail now has an unfamiliarname. But in fact, these “new” names are notnew at all.

The historic names of the park’s trails are ofgreat value—they provide perspective, and paytribute to those who helped shape this landinto one of our nation’s most beloved nation-al parks. Because of this significance, park staffare working to restore many of Acadia’s trailsto their original names. This work began onthe west side of Mount Desert Island in the fallof 2008, and will continue to the east side dur-ing the summer of 2009. The project is partof the Acadia Trails Forever program, estab-lished by Friends of Acadia and the park, andfunded by money from both park user fees

and Friends of Acadia’s trails endowment.Of course, the changes will not always be

obvious. Many of the revisions are, in a way,purely cosmetic: the Jordan Pond Carry Trailwill become simply Jordan Pond Carry; theSargent Mountain South Ridge Trail willbecome the Sargent South Ridge Trail. To theotherwise-occupied hiker, captivated byAcadia’s woods, the difference will likely beunnoticed. But others are more radical, andmight make you pause to pull out your mapand confirm that, yes in fact, you are on thecorrect trail. The system’s present Tarn Trail,along the west side of the Tarn, will returnto its historical name of Kane Path. The FlyingMountain Trail will now terminate at ValleyCove, where it will extend northward to ManO’War Brook as Valley Cove Trail. The EastFace trail on Champlain Mountain is now theOrange and Black Path.

Another thing to note is the use of the word“path.” Formerly, on the east side of MDI,highly-constructed trails were often knownas paths. Over the years, this naming con-vention has changed, and we are now accus-tomed to referring to “trails,” rather than

“paths.” But now, this change is beingundone, and trails that were originally pathswill return once again to that designation.Some examples include Asticou & JordanPond Path, Bubble & Jordan Ponds Path,Emery Path, and Schiff Path.

Restoring historic names to Acadia’s trailsis only a small part of the park’s Hiking TrailsManagement Plan – but it is not an effortundertaken lightly. In deciding which trailnames to modify and which to retain, parkstaff carefully examined and evaluated thehistoric origin of each trail. Some of thechanges are minor, while others are majorrevisions – but they were all enacted in orderto improve the sense of character and histo-ry of the island’s trail system.

So, this summer, when you come across atrail name you don’t recognize, don’t fret –just make note of the new name on your map,and then, when you’re ready, continue yourhike. The name may be different, but the trailis still the same. ❧

IAN MARQUIS is communications coordi-nator at Friends of Acadia.

NEW NAME, SAME GREAT TRAILIan Marquis

Trail signs on top of Dorr Mountain

8 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

Stewardship

ACADIA’S ISLAND RANGERSStuart West and Chris Wiebusch

When most park visitors think ofAcadia, the popular MountDesert Island section of the park

is usually what comes to mind. The more dis-tant Schoodic and Isle au Haut, though fea-tured within the park’s color brochure, areless advertised and far less visited. Even less

frequented are the islands that dot the hori-zon as you look out from the summit ofCadillac Mountain. They, too, are woven

within the fabric of Acadia National Park.This is a story of the rangers that tend to thoseislands.

Only 12 of the islands you see from thepark’s peaks are owned and managed in themanner of park property on MDI. Most ofthe other islands are privately owned, but pre-served through hundreds of conservationeasements held by the State of Maine, non-profit conservation organizations, and AcadiaNational Park. The fact is, without theseimportant easements in place, the wild,untouched appearance of these distant islandscould be quite different. A total of 78 islandsin the archipelago are currently protectedunder conservation easements maintained bythe park.

For the uninitiated, these remote islandswill forever remain nothing more than a beau-tiful backdrop to Acadia’s stunning scenery—and for many, that is enough. But those will-ing to expend the time and effort to ventureout to the islands will gain an experience

By necessity, Acadia’s remoteisland rangers are jacks-of-all-trades. In addition to actingas law-enforcement, they aretrained in emergency med-ical, search and rescue, andwildland fire response—asare most of the ranger force.In addition, they must also beable to safely operate boatswithin the 100-square-milearea encompassing theremote island operation. Above: Remote island rangers in the Parker, Acadia’s

23-foot boat.

Below: Just a few of the many islands protected by thepark (Burnt Island in the foreground, Pell Island inthe center, and Merchant Island at the top right).

All

phot

ogra

phs

cour

tesy

of

the

Nat

iona

l Par

k Se

rvic

e

9Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

unmatched by anything on MDI. Acadia’s lessfrequented islands provide visitors the great-est opportunity for solitude and contempla-tion—a chance to explore Acadia’s unmani-cured wild side.

Visitors are welcome on the islands ownedby the park, and on some of the conservation

easement properties (however, access onislands under easement is determined by eachprivate landowner). Many of these areas haverestrictions in place to protect the habitat andwildness of these lands. For instance, visita-tion may be limited at certain times of theyear, to allow nesting birds to rear theiryoung, or seals to raise their pups.

Acadia’s remote islands are patrolled andmonitored by a specialized group of rangerswho are self-taught in the area of conserva-tion easements, and who have, over theyears, learned the coastal waters. One full-time ranger and two seasonal rangers spendMay through October visiting each easementand patrolling the islands. On park-ownedislands, they enforce the rules and regula-

tions as if they were on MDI. Working withthe Lands Office in Acadia’s ResourceManagement Division, and with privatelandowners, these rangers also patrol andregulate use on the islands with conserva-tion easements. When visiting the easementislands, rangers ensure that easement

covenants have not been breached, and thatvisitors are in compliance with applicableregulations.

By necessity, Acadia’s remote island rangersare jacks-of-all-trades. In addition to acting aslaw-enforcement, they are trained in emer-gency medical, search and rescue, and wild-land fire response—as are most of the rangerforce. In addition, they must also be able tosafely operate boats within the 100-square-mile area encompassing the remote islandoperation.

Rangers operate two boats: an 18-footAlaskan Lund, ideal for shallow waters andbeach landings, and a 23-foot Parker, bettersuited to rough seas, inclement weather, andovernight trips. As many a boater can testify,

the waters along coastal Maine are unforgiv-ing if you do not pay close attention and heedthe weather, buoy markers, seas, and granite-lined approaches. Boat-operation qualificationsrequire that each ranger attend a motorboatoperators course, and then accompany anoth-er ranger with experience in order to learn thearea. They also must log 15 hours operatingthe boat, and then complete a skills checklistbefore they are allowed to go out on their own.

Of course, even jacks-of-all-trades cannotwork entirely alone. Rangers also cooperatewith other divisions in the park to provide boattransportation to the islands. The small staffbrings volunteers out for shoreline clean-ups,assists maintenance crews with projects andtransportation of materials, and transportsresearchers and dignitaries to areas seldomexperienced by the average park visitor.

Island rangers are also responsible forisland-specific projects, including cleaningup unauthorized campsites, collecting debris,posting signs for bald eagle and sea bird nest-ing closures, locating and recording histori-cal and cultural sites, and monitoring areasof archeological significance. They workclosely with other agencies—such as the U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service and the MaineWarden Service, and with non-profit organ-izations, such as Maine Coast Heritage Trust,the Nature Conservancy, and the MaineIsland Trail Association—to monitor islands,perform work projects, and provide infor-mation on what is happening on these dis-tant park lands. The island rangers are thecaretakers of Acadia’s most remote andsecluded holdings.

The next time you admire the view fromone of Acadia’s many peaks, remember: theislands you see are more than simply a beau-tiful backdrop. They are a vibrant, vital partof Acadia, watched over by group of highlytrained professionals. ❧

RANGER CHRIS WIEBUSCH leads the boatpatrol operation, and STUART WEST isAcadia’s chief ranger.

Taking a break after an island clean-up on Baker Island.

10 Summer 2009

Loon 983-153-53 is either lucky or avery good father. For seven years, hehas returned to the same tree-lined

pond on Mount Desert Island. Like clock-work, he and his mate (or mates, as the lackof bands on the female has preventedobservers from determining if she is one birdor several over the years) land on the pondeach spring. They build a nest of muddy reedsand grasses along the lakeshore. The eggs arelaid in May, and hatch in late June. Downybrown chicks emerge, heading into the waterwith mom and dad within a day. At least oneof loon 983-153-53’s chicks has survived eachyear since 2002—twice the reproductive suc-cess rate for loons in Maine. We know a lotabout loon 983-153-53, and we have the

Mount Desert Island Loon Monitoring Projectto thank for it.

In the late 1990s, the BioDiversity ResearchInstitute (BRI) began a loon pilot project withAcadia National Park and other organizations.They knew the statewide success rate wasapproximately .5 (one fledged chick for everytwo pairs of loons), but what they didn’tknow was how loons were doing on theisland. It seemed like they would flourishhere—MDI’s lakes and ponds provide amplesuitable habitat. But where were they breed-ing? And more importantly: were the chickssurviving? If not, why?

The project resulted in a few banded birds,discovery of some problems facing nestingloons, and an awareness that increased con-servation efforts were needed to better pro-tect loons and understand the issues theyfaced. In 2002, with the support of the parkand grants from Friends of Acadia, the BRIjoined forces with the Somes-MeynellWildlife Sanctuary (SMWS) to begin theMount Desert Island Loon MonitoringProject, with a goal to explore the reproduc-tive population success of common loons(Gavia immer) on Mount Desert Island.

For five years, BRI and SMWS gathered

data about each loon pair attempting to neston the island, trained volunteers, and com-municated with researchers and landowners.When the initial project ended, AcadiaNational Park and Friends of Acadia steppedforward to work with SMWS in a three-yeartrial partnership (2007–2009). Since that time,staff and volunteers have monitored 14 lakes,with seven to nine nesting territories, over afour-month period each spring and summer.

David Lamon, executive director of SMWS,and Bruce Connery, wildlife biologist atAcadia National Park, administer the project.A loon monitoring intern leads the field activ-ities and public outreach each summer,ensuring that the monitoring schedule anddesign are being followed. The intern collectsdata from staff, volunteers, and lakeshore res-idents, and maintains a database of loon nest-ing territory and population information thatis shared between SMWS and the park, aswell as BRI. Julie Rumrill, who holds a Masterof Science degree from the University ofVermont, is the 2009 intern.

Volunteers are essential to the loon moni-toring project—and more volunteers join theeffort every year. Over the past two years,more than 50 volunteers have participated inloon stewardship activities. After an intro-ductory training, they spend hours watchingnesting loons and filling out observationforms with questions about behavior, dis-turbance, and more. “Loon observation is thetype of work that really lends itself to citizenscientist involvement,” says Lamon. “Thework volunteers do is important; their obser-vations make the picture that much clearer.”

The contributions of volunteers andlakeshore residents make loon monitoring anexcellent public education tool—which is onereason the project is so notable. Lamon saysthere are other reasons, too. “It’s a great exam-ple of a collaboration where the pieces—two nonprofits and one governmentagency—come together to accomplish muchmore collectively than they could on theirown,” says Lamon. “For example, in the

Wildlife

LOON LESSONS: WORKING TOGETHER TO LEARN MOREGinny Reams

Friends of Acadia Journal

Known as the “Great Northern Diver,” common loonscan travel up to 200 feet underwater in search of fish.

Young loons spend time with both parents, learning to fish or resting on a parent’s back.

All

phot

os c

ourt

esy

of L

ora

Hal

ler

11Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

2007–2008 season, the program saw morethan 1,000 hours of monitoring and educa-tion.” Of equal importance, the informationcollected over the eight-year duration of thestudy provides baseline data that can serveas a launching pad for further studies.

The data collected on Mount Desert Islandalso provides context for other studies. A2007 BRI study tested environmental con-taminants in 23 bird species in Maine, includ-ing one unviable loon egg from Long Pond.Researchers found that mercury levels in theloon egg exceeded the level where adverseeffects have been detected in other birds.Many of us think Acadia is pristine, but thatis not always not the case. Prevailing windscarry airborne contaminants—includingemissions from power plants and vehicles, aswell as waste combustion—from the southand west toward Maine, where they aredeposited in the environment. As mercuryand other contaminants are deposited intolakes and ponds and across terrestrial habi-tats, they are converted by algae and bacte-ria into forms that are more easily digestedor absorbed. Ingested by fish, these contam-inants work their way through the food chain,reaching the top, where traces of these con-taminants accumulate in fish-eating species.Loons and other species that occupy the topof the food chain in water environments arehighly susceptible to these contaminants, andcan serve as indicators of aquatic ecosystemhealth—especially for mercury contamination.

The vulnerability of loons is something themonitoring project can help track. Betweenfour and eight pairs of loons nest on MountDesert Island each year. Over the study’s sevenyears, these nesting loons produced an aver-age of approximately one fledged chick forevery two nesting pairs—or .49 young perpair, which is nearly the same reproductionrate as the state. A total of 21 loon chicks havefledged since the study began. Loon moni-tors observed several factors that contributeto the reproductive success and failure ofloons on the island: predation of eggs andchicks by birds and mammals, sudden

changes in water levels that flood nests, deathof parents, and unviable eggs. During thecourse of the project, two loons died on LongPond from lead poisoning, caused by theingestion of lead fishing tackle. (Although itis illegal to sell lead fishing tackle of ½ ounceor less in Maine, many anglers still use it.

When discarded and left in the environment,lead tackle poses serious problems for loons.)

What’s in store for the future of the loonmonitoring project? 2009 is the last sched-uled year of the three-way partnership, butboth Lamon and Connery stress the need tocontinue collecting information. “By contin-uing the study, we can keep a minimum base-line going for future studies,” says Lamon.And unanswered questions remain: Whyare some territories on the island more pro-ductive than others? Do other loons on theisland have high concentrations of mercury?What are the long-term effects of mercury onthe population? Can management tools—such as signs, trail closures, and placementof nesting rafts—help increase nesting andfledging success?

Only through continued monitoring ofloons on Mount Desert Island can we answerthese questions—and more.❧

GINNY REAMS is the writer-editor at AcadiaNational Park.

PROTECTING LOONSMany of us are fascinated with loons andtheir haunting calls. Unfortunately, nest-ing loons are highly sensitive to distur-bance; if we approach too closely, theymay leave the nest, putting the lives oftheir chicks at risk. If a loon exhibitssigns of stress (the “penguin dance”across the water, a quavering laugh, ora flattened body and neck next to thewater), you are too close.

Practice good stewardship behavior:• In canoes and kayaks, never approach

resting, nesting, or diving loons.• In motorboats, use slow speeds near

shorelines.• Keep pets leashed and away from

loons in water.• Avoid using lead fishing gear in lakes.

Designed for life on the water, loon are awkward on land, going ashore only to mate and incubate their eggs.

The loon population is fairly stable in Maine, but theirsusceptibility to contaminants is cause for concerns.

12 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

Ihave favorite stories I recall wheneveranyone will listen about the best of mynational park experiences. Few people

enter a national park without being inspiredby the experience, creating indelible memo-ries. After a day spent riding a carriagethrough Acadia last year, a visitor said tome, “I will want to come back again andagain, but if I don’t, it will be a day I willremember forever.”

This fall, Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan’snewest documentary, The National Parks:America’s Best Idea, tells the story of ournational parks and the inspiration behindtheir creation. Six years in the making, thesix-part series explores the creation of thenational park idea and the stories of the indi-viduals who created national parks. AsDayton Duncan says, “. . . Our series is filledwith heroes—people who are entirelyunknown to most Americans. These werepeople from every conceivable background—

from the rich who through their wealth andtheir philanthropy created parks, to the poorwho, for example, gave pennies to help savethe Smokies.”

Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan haveexplored our American identity in other doc-umentaries, through such diverse topics asThe Civil War, Lewis & Clark, The War, Baseball,and Jazz. “I think we’ve always been curiousabout who we are as a people and what it

means to be American,” said Burns. “I thinkwhat’s amazing about the parks story is thatit’s so intimate.”

At the heart of the documentary is the ideaof the uniquely American legacy of our parks.“I like to think that the park idea is basicallythe Declaration of Independence overlaid ontothis land that we inhabit,” said Duncan. “Inother places they set those special places asidefor the very richest in their society or for peo-ple who were of the nobility. But as Americans,we rejected that, determining that this land

belongs to everyone. Created by the people,for the people to enjoy forever, the nationalparks embody the essence of democracy.”

The National Parks includes interviews dis-cussing aspects of national park history, jour-nal entries, photographs, paintings, and sto-ries from a range of experiences and inspira-tions in the growing National Park System.“What is life but to dream and do,” wroteElizabeth Gerkey in her journal more than80 years ago while planning her next nation-al park visit.

The series tells the history of the newly cre-ated National Park Service in 1916, and theevolving understanding of the opportunitiesand responsibilities incumbent on the stew-ards of our national parks and the heritagethey protect. “But our national heritage isricher than just scenic features; the realiza-tion is coming that perhaps our greatestnational heritage is nature itself, with all itscomplexity and its abundance of life, which,when combined with great scenic beauty asit is in the national parks, becomes of unlim-ited value. This is what we would attain inthe national parks,” as George MelendezWright wrote in 1933.

The National Parks is filmed in America’smost breathtaking landscapes — from Hawai’ivolcanoes to the Atlantic crashing on Maine’srocky coast, a sweep over Bridal Falls inYosemite to grizzly bears fishing in a wildAlaskan river. This summer, on August 5 and6 in Bar Harbor and Portland, respectively, youhave an opportunity to preview The NationalParks, with Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan onhand to discuss the series, the making of thedocumentary, and their rich cache of storiesabout national parks and the individuals whohave created and cared for their legacy. Formore information about the August events,visit our website at www.friendsofacadia.org.The series will air on PBS stations September27 through October 2, and will be availablefor streaming through October 11.

Until then, we hope to see you out in thepark. ❧

—Marla O’Byrne

THE NATIONAL PARKS: AMERICA’S BEST IDEA

History

“National parks are the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely

democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.” —Wallace Stegner

Ken Burns at Nevada Falls, Yosemite National Park.

Paul

Bar

nes

13Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

April 29 marked the close of an era inAcadia National Park’s land protec-tion history when Mike Blaney, lands

specialist extraordinaire, retired. Mike becameAcadia’s first lands specialist in 1989, aftermore than 25 years working in various sea-sonal and permanent positions in theNational Park Service. Taking on this neweffort at Acadia, Mike guided the develop-ment of the park’s conservation easement pro-gram. Under his leadership, the park accept-ed—and now monitors—212 conservationeasements protecting more than 12,000 acresof privately-owned land. The easement pro-gram has expanded Acadia’s extensive con-servation legacy of protected natural, cultur-al, and scenic resources.

When a landowner grants a conservationeasement on his or her property, rights aredonated—the right to develop a portion or allof the property, for example. Whatever agree-ment is developed through the easement, theprotected property must be monitored annu-ally to assure compliance, particularly as own-ership changes. The legal understandingdeveloped through an easement may be for-gotten, or the commitment diluted as second-and third-generation landowners take own-ership. Each year, Mike visited the easedproperties—captaining a park boat to reachthe many protected properties located onoffshore islands—and developed relationshipswith landowners to ensure ongoing protec-tion of the natural, cultural, and scenicresources under Acadia’s stewardship.

Mike also shepherded easements throughthe process of legal review, negotiation,and presentation to the town in which thelands resided and to the Acadia NationalPark Advisory Commission. Once an ease-ment was granted to the park, Mike devel-oped the baseline data—the snapshot of thelands’ character at the time of protection,to be monitored annually. His responsibili-ties were immense, and for many years hewas the sole staff person working on thepark’s conservation easement program.

In 2000, Friends of Acadia embarked ona multi-year commitment to contract addi-

tional professional support to assist Mike withbaseline management of the park’s conserva-tion easement program. Friends also gavethe first annual grant to hire a lands protec-tion assistant—the factotum as Mike calledher. Over the past few years, Mike expandedthe easement monitoring effort to include theassistance of off-shore rangers. “I asked therangers to monitor from offshore as they wereout on other trips that took them past pro-tected lands,” said Mike. “It was a naturalfit.” [Read more about this effort on page 8]

Mike is a walking database of informationand history about the properties protected,the landowners’ original conservation intents,

and the role of different partners in the pro-tection of lands and islands surroundingAcadia. Ongoing protection may becomemore challenging with change of owner-ship, but as Mike says, “the conservation ease-ment concept is a valid tool. It benefits thetown, the people, and the property owner.”

Planning ahead for his retirement, twoyears ago Mike encouraged Acadia to hire hisreplacement, Emily Seger, to work closelywith him. Emily has taken the reins as landsspecialist with a strong understanding ofAcadia’s commitment to land protection andits many responsibilities as the holder of morethan 200 conservation easements.

During his years with the park, Mike cre-ated a legacy of land protection that will ben-efit millions for ages to come. The conserva-tion easements negotiated under his tenureprotect coastal habitats, unimpaired views,and the experience of natural wildness alongAcadia’s coast.❧

—Marla O’Byrne

Special Person

MIKE BLANEY: LAND PROTECTION LEGACY

Mike Blaney aboard his boat, monitoring some of Acadia’s island easements.

Under his leadership, thepark accepted—and nowmonitors—212 conservationeasements protecting morethan 12,000 acres of private-ly-owned land.

Jill

Web

er

14 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

This speech was given at the 2009 Friends ofAcadia Annual Meeting

It is an honor for me to be here today,and to have the opportunity to speak atthis annual meeting of an organization

which has done so much for both the causeof conservation and Acadia National Park.

As many of you are aware, I am the grand-son of another Keith Miller—superintendentof Acadia from 1971 to 1978—a man whospent most of his life crisscrossing the UnitedStates, first as a ranger, and later as a super-intendent in the national park service.

My grandfather has taught me so manythings over the course of my life that I doubtit would be possible to accurately convey withwords the positive influence he has had onme. It was he that taught me the importanceof fulfilling commitments, seeing projectsthrough the end, and making sure I did mybest no matter what the task. He taught menever to be late. He taught me never to fol-low, but instead to lead. And, as any true childof the Great Depression, he taught me thatabove all else, I was to clean my plate.

But perhaps most importantly, when Iwas very young, he took me one of the beach-es in Acadia. There, I found a special stone—a beautiful stone, one I wanted to take homewith me and keep as my own. My grandfa-ther stopped me, and spoke to me a phrasequite simple, but one which has stuck withme to this day. “Imagine if everyone took one.Then there would be none left for anybodyelse.” This was truly the first time that themeaning of conservation, albeit in its mostsimple definition, dawned upon me. That ifwe all took and never bothered to preserve,we would rob not only ourselves, but all thosewho came after us of the same beauty we wereso fortunate to enjoy at that very moment.

Still very young, but with this most basicunderstanding of conservation, I went on tovolunteer for Friends of Acadia. I joined theYouth Conservation Corps, and later landeda job with the Acadia National Park trail crew,where I now work with a group of men I

could not be more proud to call my cowork-ers. Here, I learned that pouring rain was noexcuse to avoid work; that being covered inmud was something to proud of no matterhow much your family fretted about the dam-age you were doing to the washing machine;

and that there were far more intricacies todigging a ditch than I had ever thought pos-sible. But more importantly, I began to gainan understanding of both the remarkableamount of work required to maintain a parklike Acadia, and the value of an organization

Youth

REACHING OUT TO MY GENERATIONKeith Miller

Keith Miller demonstrates the use of a highline to move heavy rocks at Family Fun Day.

Rog

ier

van

Bake

l

15Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

like Friends and its volunteers, who were will-ing to donate their time, money, and muscleto help protect this park they had come tolove so much.

It was slowly becoming clearer to me whatthe practical applications of conservationentailed: thousands of hours back-breakinglabor; hundreds of thousands of dollars; anda commitment to continuously work to main-tain that which never seemed to stop tryingits best to fall apart. It became all too obvi-ous that the work of conservation was neverdone. But at the same time, I began to seehow these obstacles could be overcome:through the sheer determination of individ-uals who did not see the task as a daunting,never-ending difficulty, but rather a labor oflove, whose infinite nature was only a testa-ment to the need for continued vigilance anddedication. I was now going from under-standing why it was important to conserve,to seeing how it could be done in the realworld, by real people.

However, at the end of every summer Iwould return home to school—now to col-lege—and to the ever faster-paced life of mygeneration. Our days seem so full to us thatwe often barely find the time to sleep. Butwhen we do find that rare time off, it seemsto me, my generation has largely forgottenabout national parks. It is not that we har-bor any ill will towards them, or that we wereborn without an appreciation for naturalbeauty—but simply that they do not cometo mind. We have become too wrapped upin the world we have constructed around our-selves. We simply cannot see the forest pastthe skyscrapers. I would say that the major-ity of my friends have spent little to no timein a national park, but have spent countlessdays in malls, movie theatres, or in front oftheir own televisions and computers.Whether it was out of convenience or a gen-uine concern for our safety, too many of ourparents never told us to ‘go play in the woods’instead raising us within the comfortable con-fines of our homes, schools, and day-care cen-ters. Dirt and scratches and mosquito bites

became declared enemies of a society evermore obsessed with cleanliness and comfort.While human material progress is certainlya blessing in a number of ways, my genera-tion’s connection to the natural world hasbeen among its greatest silent casualties.

But I did not come here to decry the mod-ern world, nor am I attempting to condemnmy generation as worse than any other. WhatI wish to do is simply call on all of us to helpbring my generation back—to help us regaina healthy balance between the world of manand the world of nature—because it is fromAmerica’s most quiet of monuments, nation-al parks, that we may have the most to learn.

Truly, National Parks are one of America’sgreatest experiments in both democracy andconservation. They demonstrate what can beachieved when differences in wealth and classare put aside to save something that is ofunfathomable worth to the nation as a whole.In these days when the gaps between thewealthy and the poor—between the politi-cians and the common man—seem to growever wider, national parks stand as a testa-ment to what can be achieved when we rec-ognize that some things are too precious totake for ourselves, but should instead be pro-tected by all of us, for all of us, and for allthose who come after us.

It is remarkable to me, that as America laidthe foundations of the greatest industrial basethe world has ever seen, and as capitalismand the market came to define the Americanpsyche, there were men like John Rockefeller,George Dorr, and Teddy Roosevelt, whostepped back for a moment and thought notto gobble up these pristine Edens for them-selves to save as private getaways, but insteadtook it upon themselves to set these placesaside for the American public as a whole.And employed by them in this venture werecountless artisans, names now forgotten,whose remarkable staircases, vistas, andbridges all stand as monuments to these men’smost democratic of visions. This was auniquely American idea—that these beauti-ful places would not be bought and horded

by the few, but made available to all—thatevery single person had the right to enjoythese treasures. This was a new democraticconservation.

My generation could stand to learn somuch from this great experiment, and fromorganizations like Friends of Acadia. We mustlearn that man cannot live in conflict withnature, but is much better off seeking har-mony with her. We must learn that sometasks like conservation require endless devo-tion and will never be ‘finished’ per se, butthis does not diminish their importance. Andwe must learn that sometimes self-interestmust be put aside for the good of us all, andthat when we do all come together it isabsolutely astounding what we can achieve.It only takes a minute on the top of Cadillacto come to that realization.

In closing, I would ask two things of all ofyou: Firstly, the next time a young person tellsyou they have a vacation, or even a free week-end, remind them that national parks arethere. Encourage them to take a hike, gokayaking, or even just take a walk. I can guar-antee that if you can just get them out there,for even the shortest of times, there is a verygood chance they will fall in love. And hon-estly, if you want to rope in a college stu-dent, mentioning how inexpensive access tonational park is never hurts.

And secondly, the next time a child orsomeone from abroad asks you ‘what isAmerica’? Before you leap into talking aboutskyscrapers, cheeseburgers, automobiles, andHollywood, perhaps take a moment and tellthem about our national parks. Maybe tellthem how we pioneered democratic conser-vation before you tell them about how wepioneered mass production. America’s great-est achievements are not all asphalt andsteel—many are granite and dirt—and Iwould hope you can convince my generationand others of this simple fact.❧

KEITH MILLER is the grandson of KeithMiller, Acadia National Park superintendentfrom 1971 to 1978.

16 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

“Never doubt that a small group of

thoughtful, committed citizens can

change the world. Indeed, it is the only

thing that ever has.” —Margaret Mead

One of the greatest joys of my role aschairman of Friends of Acadia ispublicly celebrating the work of the

incredible members and volunteers who sup-port us. The Cairns Society is an example ofhow effectively the next generation is devel-oping as stewards on behalf of AcadiaNational Park. In order for this preciousresource to endure as a wellspring of wildserenity, there must always be people who arewilling to protect it: stewards and stake-holders. That is precisely what the Cairns are.

I asked Leandra Fremont-Smith, a CairnsSociety founder, to share how the name cameabout, and also to explain the purpose androle of the Cairns. This is what she had to say:“If you hike Acadia’s mountain trails youwill see them. Piles of rock marching up themountain with you. As trail markers, cairnskeep hikers on a single route, protecting frag-ile soil and vegetation. In foggy or stormyweather, they can be life-savers, helping tokeep you safely on the trail. The role of thecairns is crucial in protecting the mountainlandscape—and you.”

Friends of Acadia is a starting point formany generations of members to becomeactively engaged in an effort to support aplace of great value: Acadia National Park.

“I originally came up with the idea to forma young group in order to support FOA,” saysFremont-Smith. “I have gone to many of yourevents—the Annual Benefit, Family Fun Day,and friend-raising activities like ReverendPeter Gomes’ “Charles Eliot & Acadia.”

Despite the fact that Friends currentlysponsors many events and activities that

encourage volunteerism, Leandra and sever-al of her friends felt that a key group of indi-viduals was missing: next generation leadersin the 25-45 year-old range. This particularage group is unique because they frequentlyuse the park, but are so occupied with jobsand young families that participating in FOAactivities is often difficult or next-to-impos-sible. However, if a group were to hold one

or two events a year at the right time, with awell thought-out guest list, these individu-als could still be engaged despite schedulingdifficulties.

“Once someone is a Cairn, they will beable to look forward to reoccurring eventseach year that fit into their busy schedule,”Fremont-Smith says. “It is our hope that fiveyears from now, Cairns members will becomemore active in Friends of Acadia in general—volunteering in the park, helping out withannual events, and even making financialcontributions.”

Last summer, the Cairns Society held theirfirst event in Northeast Harbor. By allaccounts, it was a complete success, wel-

coming a new wave of Friends for Acadiasupporters. Part of the reason for this suc-cess, Fremont-Smith believes, is the group’sfocus: island-wide representation.

“When I first organized the Cairns Society,I wanted to have four women who could rep-resent the island well,” she says. “LauraZukerman is from Little Cranberry, JennyPetschek from Seal Harbor, Elizabeth Merckand Heather Toogood from Northeast Harbor,and I am from Bar Harbor. Between the fourof us, we were able to devise a dynamic guestlist, as well as including guests fromSomesville, Southwest Harbor, and BassHarbor. We put on an amazing event, and in2009 we added Kate Pickett and CourtneyUrfer to our committee.”

This year, the Cairns Society is gearing upfor several gatherings. In addition to meet-ings on Mount Desert Island, the group isplanning a film event in New York City,focused on Acadia National Park. But whyNew York?

“So many of the Cairns work in New Yorkor close by, and all of us miss Acadia duringthe busy times of the year when getting toMaine is simply not possible,” Fremont-Smithsays. “Having an event locally gives all of usthe chance to celebrate our passionate com-mitment to Friends, be informed of currentwork in Acadia, and synthesize our energyinto action as next generation leaders.”

Working with a group like the Cairns—acollection of dedicated, inspired next-gener-ation leaders—makes my role as Chairmanof the Board a true joy. Thank you, CairnsSociety. We are all here to help you growand continue your successful legacy for thenext generation of leadership of Friends andAcadia. ❧

LILI PEW is chairman of the Friends ofAcadia Board of Directors.

Leadership

THE CAIRNS SOCIETY:A GUIDING FORCE FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF FRIENDS

Lili Pew

Kat

e Pi

cket

t

17Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

Looking for the perfect gift idea fora birthday or anniversary?

Introduce someone you care about toAcadia with a gift membership in

Friends of Acadia.

Please send a special $40 gift package* to:

___________________________Name

______________________________________________________Address

_________________________________________________________________________________City, State, Zip Code, & Telephone Number

Message you would like on the card:_________________________________________________________________________________* Gift package includes:

• Greetings from the Heart of Acadia, a packet of seven lovely note cards designedespecially for Friends of Acadia, featuringphotographs of Acadia National Park.

• A one-year subscription to the Friends ofAcadia Journal, published three timesannually

• A Friends of Acadia window decal

• The satisfaction of knowing that membership in Friends of Acadia helpsto preserve the remarkable beauty ofAcadia National Park

To give a gift membership, simply mail theabove form, along with a check made payable toFriends of Acadia, in the envelope provided or

visit www.friendsofacadia.org.All contributions to Friends of Acadia are used to preserve,protect, and promote stewardship of the outstanding natu-ral beauty, ecological vitality, and distinctive culturalresources of Acadia National Park and the surroundingcommunities. All gifts are tax deductible.

Friends of AcadiaP.O. Box 45 • Bar Harbor, ME 04609

www.friendsofacadia.org207-288-3340 • 800-625-0321

Give the Gift of Acadia

��

��

Acadia Gateway Center PassesZoning HurdleOn Saturday, May 30th, Trenton residentsapproved the contract between the MaineDepartment of Transportation and the Townof Trenton to change the zoning for the prop-erty on the west side of Route 3 where the

Acadia Gateway Center will be located. Thiswas a critical step in the process to build theCenter that will house DowneastTransportation’s offices and maintenance facil-ities and provide a location for visitors to pur-chase park passes, get local and park infor-mation, and ride the Island Explorer if theychoose.

Presently, the Island Explorer bus serviceworks well for residents and visitors to Acadiawho have parking spaces at their lodgingestablishments or homes on Mount DesertIsland (MDI). Buses pick up and drop off pas-sengers anywhere along their routes where itis safe. An underserved population, howev-er, is day visitors and those coming from off-Island lodging establishments. Adequate pub-lic parking was not available at the airport,Thompson Island, or other locations on theapproach to MDI to enable visitors to leavetheir cars for the entire day and ride the IslandExplorer for hiking or other activities.

For more than ten years, the partners inthe Island Explorer had been planning a tran-sit and welcome center as Phase 3 of the bussystem. Multiple sites in Trenton and BarHarbor were studied as possible locations for

the center. Friends of Acadia purchased onoption on 369 acres in Trenton, which even-tually was selected as the preferred location.The Maine Department of Transportation(MDOT) completed an environmental assess-ment of the project, projecting no signifi-cant impacts. Friends then purchased theland and immediately sold approximately152 acres bordering Route 3 to MDOT.

The Acadia Gateway Center will be built

in four phases. The first phase is the mainte-nance center and office space for DowneastTransportation, which runs the IslandExplorer and other transit services inHancock County. The entrance road and util-ity systems for all phases of the GatewayCenter will also be constructed in the firstphase. The design of the maintenance cen-ter is nearly complete, and MDOT will securebuilding permits from the Trenton PlanningBoard before going to bid on the contract tobuild this summer. MDOT is also pursuingthe federal and state funding needed to begindesign work for the second phase of theCenter, the welcome center buildings andparking areas.

Acadia Night Sky Festival PlannedIf you have ever been awed by AcadiaNational Park’s starlit skies, plan a visit to Mt.Desert Island for the inaugural Acadia NightSky Festival, September 17-21, 2009.Amateur astronomers, park visitors, andresidents will be treated to a series of artsevents, lectures, and family activities associ-ated with Acadia’s relatively pristine darknight skies. The festival follows on a part-

Updates

Concept sketch of the Acadia Gateway Center.

18 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

“Acadia is in our blood”PO Box 52

Bar Harbor, Maine 04609

E-mail: [email protected]

ACADIA FOREVER

Estate Planning—Supporting the Mission of Friends of Acadia

Preserving and protecting the outstanding natural beauty,

ecological vitality, and cultural distinctiveness of

Acadia National Park and the surrounding communities

is a wise investment.

And, it’s simple. Add only one of the following sentences

to your will, or a codicil:

I hereby give ______% of my residuary estate to Friends of Acadia, Inc., a Maine charitable corporation,

PO Box 45, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, for its charitable purposes.

I hereby bequeath $______ to Friends of Acadia, Inc., a Maine charitable corporation, PO Box 45,

Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, for its charitable purposes.

I hereby devise the following property to Friends of Acadia, Inc., a Maine charitable corporation,

PO Box 45, Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, for its charitable purposes: [legal description of the property].

For more information, call the office at 207-288-3340 or 800-625-0321,

email the director of development at [email protected],

or visit our website at www.friendsofacadia.org.

John

Cip

rian

i

19Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

Our purpose...is supporting yours.

nership among Friends of Acadia, the IslandAstronomy Institute, and Acadia NationalPark to measure, promote, and protect thequality of Acadia’s night skies. Local cham-bers of commerce, nonprofit organizations,businesses, and others have joined the effort,planning daytime, nighttime, indoor, andoutdoor activities during the festival. The fes-tival dates were selected because there willbe a new moon, and the evenings will still berelatively warm. Highlights include a nightsky-themed concert by the BangorSymphony Orchestra, ranger-led night walksin Acadia, and a night cruise on FrenchmanBay. The festival schedule, accessible atwww.nightskyfestival.org, changes regularlyas new events are added—so check oftenfor updates. Join us in this community cele-bration to promote the protection and enjoy-ment of Downeast/Acadia’s stellar night skyas a valuable natural resource through edu-cation, science, and the arts.

Acadia QuestSo far, over 75 teams have signed up for the2009 Acadia Quest program. The Quest, inits second year, is a program organized by

Friends of Acadia and Acadia National Park,designed to encourage kids to spend moretime outside—especially in Acadia. Thisyear’s program kicked off on Saturday, April,25th, with two events for the teams to choosefrom: the Earth Day Roadside Clean-up andNational Junior Ranger Day (pictured).

L.L.Bean Research FellowshipsAwardedWhat do rock climbers, arboreal insects, bar-nacles, and bats have in common? They areall the focus of research projects fundedthrough the 2009 L.L.Bean Acadia ResearchFellowship program. Thanks once again toL.L.Bean’s gift of $25,000 to Friends ofAcadia, six research projects will receivefinancial support this year. This fundingwas matched by $10,000 from AcadiaPartners for Science and Learning to supporttwo additional research projects specific tothe Schoodic District of Acadia National Park.

The L.L.Bean Acadia Research Fellowshipprogram is designed to encourage fieldresearch at Acadia in the physical, biological,ecological, social, and cultural sciences. Thegrant prospectus lists important park issuesto be addressed, such as air pollution, habi-tat fragmentation, non-native invasivespecies, and recreation impacts on parkresources and the visitor experience. Collegeand graduate students, faculty, agency sci-entists, private-sector researchers, and otherqualified individuals are all welcome to apply.

In 2009, twenty-three applications,requesting over $94,000, were received forthe L.L.Bean Acadia Research Fellowships.The following projects received grants:

Dr. Daniel Bunker, New Jersey Institute ofTechnology. Quantifying invasive speciesrisks: Traits, trade-offs, and target commu-nity composition.

Timothy Divoll, University of SouthernMaine and Biodiversity Research Institute.Coastal and island use by bats in relation topotential windpower.

Kevin Dougherty and Dr. John Daigle,University of Maine. Rock climbers’ experi-ence and their attitudes toward managementof climbing in Acadia.

Justin Havird, University of Florida. A sur-vey of the freshwater fishes in the streams ofAcadia National Park.

Dr. Jeremy Long, Northeastern University

Tyle

r N

ordg

ren

20 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

Bar Harbor – Ellsworthwww.cadillacsports.com

BRUCE JOHN RIDDELLLANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

27 PINE STREETBAR HARBOR, MAINE 04609

207.288.9668

Creative & Innovative Landscape Architecturefor Residential & Estate Gardens

BRECHER + BRECHER +SEALANDERARCHITECTS

members of the American Institute of Architects

RESIDENTIAL

COMMERCIAL

PUBLIC

ARCHITECTURE

AND

PLANNING

SINCE 1982OFFICES in BAR HARBOR & ELLSWORTHOFFICES in BAR HARBOR & ELLSWORTHwww.brechersealander.comwww.brechersealander.com

FORESIGHT & GENEROSITY

WAYS YOU CAN GIVE“One of the greatest satisfactions in doing any

sound work for an institution, a town, or a city, or for the nation,

is that good work done for the public lasts, endures through

the generations; and the little bit of work that any individual of

the passing generation is enabled to do gains the association

with such collective activities an immortality of its own.”

—Charles W. Eliot, Sieur de Monts Celebration, 1916

Please consider these options for providing essential financial support to Friends of Acadia:

Gift of Cash or Marketable Securities. Mail a check, payable to Friends of Acadia, to PO Box 45,

Bar Harbor, Maine 04609, or visit www.friendsofacadia.org/annualfund to make a secure gift using your credit card. Call or visit the website

for instructions on giving appreciated securities, which can offer income tax benefits as well as savings on capital gains.

Gift of Retirement AssetsDesignate Friends of Acadia as a beneficiary of your IRA, 401(k),

or other retirement asset, and pass funds to Friends of Acadia free of taxes.

Gift of Real PropertyGive real estate, boats, artwork, or other real property to

Friends of Acadia and you may avoid capital gains in addition to providing much needed funds for the park.

Gift Through a Bequest in Your WillAdd Friends of Acadia as a beneficiary in your will.

For more information, contact Lisa Horsch Clark at 207-288-3340 or 800-625-0321,

email [email protected], or visit our website at www.friendsofacadia.org/join.

Tom

Bla

gden

21Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

Marine Science Center. Causes of spatial vari-ation in barnacle recruitment in AcadiaNational Park.

Robin Verble, University of Arkansas LittleRock. Do invasive European fire ants influ-ence arboreal insect diversity?

The Schoodic fellowships, supported byAcadia Partners for Science and Learning,were awarded to:

Dr. Abraham Miller-Rushing, USA NationalPhenology Network and The Wildlife Society.Monitoring phenology at Acadia NationalPark: Setting an example for the NationalPark Service and beyond.

Dr. Benjamin R. Tanner, Western CarolinaUniversity. Determination of carbon seques-tration rates in salt and freshwater marshes inthe Schoodic Section of Acadia National Park.

A Winning DesignEvery year, Acadia National Park holds acompetition among local students to createa design for Acadia’s annual park pass. Thisyear’s winner is Carolyn Liu, a soon-to-beeighth-grader at Connors Emerson School inBar Harbor. For her efforts, she was award-ed a check for $50 by Friends of Acadia and

Acadia National Park; Acadia National Parkpresented her with a certificate and additionalgifts provided by Eastern National. Carolyn’sdesign (pictured) will be reproduced on allof this year’s annual passes.

Schoodic Press Packet AvailableIn response to multiple inquiries by mem-bers of the press, Friends of Acadia has assem-bled a press packet with information aboutthe proposed development on the 3,200-acreWinter Harbor Properties lands adjacent toAcadia National Park at Schoodic. The presspacket can be found online at www.friends-ofacadia.org/advocacyschoodic. A hard copycan also be sent to any groups or journalistswho might be interested. Included in thepress packet are newspaper articles about theproposed development, a Power Point pres-entation on the resource values of theSchoodic section of the park, informationabout Friends of Acadia, the concept plan forthe proposed “eco-resort,” and maps depict-ing natural resource information. Friendscontinues to work with partners to assess andrespond to plans by Winter Harbor Propertiesto develop the land.

Keeping our Roadsides CleanMore than 300 volunteers participated in our10th annual Earth Day Roadside Clean-up.The event has become, for many people, anannual right of spring. This year, excellentweather added to the enthusiasm of the vol-unteers, many whom were thrilled to be out-

side, soaking up the sunshine—even if theywere picking up trash. Participants collectedover 1000 bags of trash, plus an assortmentof large items, including automobile parts,cell phones, and hundreds of Styrofoam cupsand plastic bags, from over 150 miles of road-side in the MDI, Trenton, and Schoodic areas.We collected less trash than last year—evi-dence that the clean-up is, indeed, improv-ing the condition of our roadsides.

F R O GH I L LDESIGNS

Betsy Barmat Stires Interior Designer

Mt. Desert Island, ME — Washington, D.C.

TEL: 703-597-3385

EMAIL: [email protected]

www.froghilldesigns.com

Carolyn Liu (center) with Kevin Langley of AcadiaNational Park (left) and Stephanie Clement of Friendsof Acadia (right).

22 Summer 2009 Friends of Acadia Journal

2009 Annual MeetingMore than 200 people gathered on July 9 forthe 2009 Annual Meeting at the Bar HarborClub. Speakers included Keith Miller, whosespeech is printed on page 12. This year, thePresident’s Award for Damn Good Work waspresented to Georgia Munsell for her out-

standing efforts as a volunteer, including herwork at the membership table. The Marianne

Edwards Distinguished Service Award wasgiven to the National Parks ConservationAssociation, represented by Vanessa Morell,director of ally development, for their unceas-ing advocacy on behalf of our nation’s nation-al parks.

In Acadia, The Work Goes OnEvery year, Friends funds programs that offermeaningful employment in Acadia. This year,we hired seasonal employees to assist withtrails, at the Wild Gardens of Acadia, and inthe lands protection office at the park.

The recreation intern and three ridge run-ners train and work with park rangers,spending the summer on Acadia’s trails. Thisyear’s ridge runners are Cecily Swinburne, agraduate of the College of the Atlantic; NicoleLavertu, a graduate of the University ofMaine; and Jeremy Cline, an incoming jun-ior at Middlebury College. This year’s recre-ation intern is Kevin Dougherty, currently agraduate student in the University of Maine’sParks, Recreation, and Tourism program.

New Members

Thomas Hageman and Nancy HoltjeCynthia HillMr. and Mrs. William HodgkinsBob HoganEdna HooverCharles JanewayHarvey Klugman and Lynne ShulmanNorman and Susan LadovKathy LawsonIan LibhartMr. and Mrs. Justin LilleyPaul and Sandra LoetherAllen and Barbara LovelandSuzanne LuescherJudith MacInnesKathleen MacNaughtonKatie MartinGail MerriamCynthia MervisDouglas Michlovitz

Dan MillerAndrew MonkLee and Siobhan NesbittJoyce PuglioEd and Phyllis RaiderMitchell RalesRobert RobbinsCraig and Amy RoebuckStella RossRichard and Leslie SaltsmanJames A. SaltsmanPhyllis Sears and Ivan KennedyElizabeth SmithLauren StrobeckJohn SuchanecFred TraskTom and Beth WalshDavid Wilson

February 1–April 30, 2009

We are pleased to welcome our newest friends:

Georgia Munsell speaks at this year’s Annual Meeting

23Friends of Acadia Journal Summer 2009

HANNAFORDSUPERMARKETS

86 Cottage StreetBar Harbor

Where Shopping is a Pleasure.

ATM Major Credit Cards

ONE SUMMIT ROAD • NORTHEAST HARBOR, MAINE 04662

www.KNOWLESCO.com207 276 3322

Distinctive properties.Legendary service.

Real estate professionals since 1898.

National Trails Day in AcadiaSaturday, June 6, was National Trails Day. Organized by Friends of Acadia and Acadia National Park, theevent was attended by more than 100 people, including 11 Acadia Quest teams. Many of the teams took partin the new First Time Hikers program, exploring trails on Great Head and South Bubble with guidance frompark interpretive staff.