Acknowledgements UNM Hydrogeoecology Group NSF Grant DEB-9903973

THANK YOU! Acknowledgements: This study was supported by the American Cancer Society as part of...

-

Upload

augusta-floyd -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of THANK YOU! Acknowledgements: This study was supported by the American Cancer Society as part of...

THANK YOU!

Acknowledgements: This study was supported by the

American Cancer Society as part of UPACS program

(Grant contract NHINTLTAA02)

1. Agaku TI, Maliselo T, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Secondhand smoke exposure as an Indicator of pro-tobacco social influences and susceptibility to smoking among Zambian Adolescents. Substance Use & Misuse (in press).2. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Olufajo O, Agaku TI. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke and voluntary adoption of smoke-free homes and cars among non-Smoking South African Adults. BMC Public Health 2014;14(1):580.3. Ayo-Yusuf OA. Tobacco smoke pollution in the 'non-smoking' sections of selected popular restaurants in Pretoria, South Africa. Tobacco Control 2014;23(3):193-4. 4. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Olutola BG. ‘Roll-your-own’ cigarette smoking in South Africa between 2007 and 2010. BMC Public Health 2013; 13(1): 597.5. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Odukoya OO, Olutola GB. Socio-demographic correlates of exclusive and concurrent use of smokeless and smoked tobacco products among Nigerian men. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2014; 16(6):641-6. 6. Ayo-Yusuf OA. Agaku TI. Intention to Switch to Smokeless Tobacco Use among South African Smokers: Results from South African Social Attitude Survey data analysis. PLOS One 2014; 9(4): e95553. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.00955537. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Olutola BG. Epidemiological association between Osteoporosis and combined smoking and use of snuff among South African women. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2014; 17; 174-177. 8. Agaku TI, Ayo-Yusuf OA. The association between smokers’ perceived importance of the appearance of Cigarettes/Cigarette packs and “Smoking Sensory Experience”: A Structural Equation Model. Nicotine & Tobacco Research (in press)9. Ayo-Yusuf OA, Olutola BG Agaku TI. Permissiveness towards tobacco sponsorship undermines tobacco Control support in Africa. Health Promotion International (in press). 10. Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Awareness of nicotine replacement therapy among South African smokers and their interest in using it for smoking cessation if provided for free. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2014; 16: 500-505. Other publications from PhD student (Not direct ACS support)11. Louwagie GM, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Tobacco use patterns in tuberculosis patients with high rates of human immunodeficiency virus co-infection in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2013; 13(1):1031. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1031.12. Louwagie G., Wouters E, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Poverty and Substance Use in South African Tuberculosis Patients. American Journal of Health Behavior 2014; 38: 501-509.13. Louwagie GMC, Okuyemi KS, Ayo-Yusuf OA. Efficacy of brief motivational interviewing on smoking cessation at

tuberculosis clinics in Tshwane, South Africa: a randomised controlled trial. Addiction (in press).

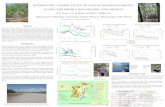

Disparities in smoking in South Africa during 2003 – 2011

Lekan Ayo-Yusuf, BDS, MPH, Ph.D

Complex social challenges – 1st world side by side 3rd world economies and development (28% of a population of 50million unemployed).

Epidemic of HIV/AIDS (5.6 million PLWH) and now increasing NCD burden.

Addressing economic & health disparities is a priority

Background

% Households without piped water

% unemployed by gender

Trends in educational achievement 1996-2011

1996 2001 20110

5

10

15

20

25

No school>Grade 12

% with medical aid

Little progress in NCD mortality

Source: Mayosi et al. (2012) Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61814-5

DALYs attributable to Diarrhea, HIV and Tobacco, 1990-2020 (baseline scenario)

Source: Murray C and Lopez A. The Global Burden of Disease. 1996.

Introduction• Smoking prevalence in South Africa - 34% in 1993 to 21.4% in

2003 (Ayo-Yusuf, 2005) due to anti-tobacco campaigns and anti-tobacco legislation .

• Impact of policies is usually first felt among the socially advantaged than the disadvantaged groups (Graham, 2009).

• The current trend data on the prevalence of smoking in South Africa covered a period either before the implementation of public smoking ban in 2001 or just a little after the implementation (Van Walbeek , 2005; SADHS, 2003).

• Also, in recent times cigarette prices have not increased commensurately with income increases (Blecher & Van Walbeek, 2009), yet cigarette tax increase is the most effective TC measure.

Real prices and consumptionSouth Africa 1960-2008

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 201030

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

R3

R4

R5

R6

R7

R8

R9

R10

R11

Year

Pa

ck

s/a

du

lt/y

ea

r

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 20150

5,000,000,000

10,000,000,000

15,000,000,000

20,000,000,000

25,000,000,000

30,000,000,000

35,000,000,000

40,000,000,000

45,000,000,000

Consumption Sticks (Based on exc. Rev.)

Consumption Sticks (Based on exc. Rev.)

Trends in legal Cigarette consumption 2003-2011

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 201219,000,000,000

20,000,000,000

21,000,000,000

22,000,000,000

23,000,000,000

24,000,000,000

25,000,000,000

26,000,000,000

Total cigarettes

Disparity by area-level deprivation 2010

Highest SES Areas

Quartile 2 Quartile 3 lowest SES Areas

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

<High sch High Sch >High Sch

3-item multiple deprivation (pipe water; flush toilet; employment)Explained 86% variance; Cronbach α = 0.92

Growth of Per Capita Social Spending

Source: South African National Treasury and Statistics South Africa.

1997 2001 2006 20110

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000R

ea

l 20

08

Ra

nd

s

R4 239

R4 993

R7 325

R10 207

Expansion of grants to Children and Foster parents

Source: South African Social Security Agency SOCPEN data.

Objective• To examine changes in smoking prevalence

that may be associated with the impact of current TC policy environment on various social classes in South Africa during 2003-2011.

• Determine socio-demographic factors associated with current smoking and trends in socio-economic inequality in smoking measured using educational achievement.

Methods

• Secondary data analysis — South African Social Attitude Surveys (SASAS) 2003 (n=2855), 2007(n=2,907) and 2011 (n=3,003).

• The SASAS is a national household survey, which uses a multi-stage probability sampling strategy with census enumeration areas as the primary sampling unit.

• Among others, data collected included socio-demographics, current smoking status, the type of tobacco products used and quit attempts.

Methods contd……

• The datasets from the three surveys were then merged (n = 8765).

• Data analysis included chi-square statistics, trend tests and multi-variable adjusted poisson’s regression analysis.

• This model specification was preferred over a binary logistic regression model because the outcome measure (current cigarette smoking) was common. More so, the effect measure (i.e., prevalence rate ratios) allows for ease of interpretation and communication (Barros & Hirakata, 2003).

• Measures of inequality included Slope Inequality index (SII), Relative Concentration Index (RCI)

• Using SATA v10, all data analysis took account of the cluster sample design used in SASAS and level of significance was set at <5% (two-tailed tests).

• The average annual percentage change (APC) in current smoking prevalence over the study period was calculated using JoinPoint regression.

• The Wald’s test for trend was used to assess linear trends in current smoking during 2003-2011, overall as well as by age, race, age, gender, employment and education.

Results: Characteristics of the study participants

female no education < grade 12 grade 12 > grade 12 currentsmoker

51.4%

0.0590000000000001

0.545

0.282

0.114

0.205

CHARACTERISTICS 2003 %(n) 2007 %(n) 2011 %(n) Annual Percentage Change during 2003-

2011 (95%CI)

Adjusted Linear Trend during 2003-

2011 p-valuea

Mean CPD (95% CI) 8.71 (8.96-10.46) 9.17 (8.37-9.98) 9.33 (8.50-10.17) 0.90 (-2.2 to 4.1) 0.20GENDER Male 42.9 (387) 37.0 (368) 34.2 (323) -2.6 (-9.4 to 4.6) 0.08†

Female 9.2 (181) 10.0 (194) 10.3 (199) 1.4 (-3.8 to 6.9) 0.45RACE/ETHNICITY Black 21.9 (280) 18.7 (271) 17.1 (220) -2.7 (-9.8 to 4.9) 0.07Coloured 38.9 (168) 41.8 (150) 40.8 (155) 0.6 (-7.9 to 9.9) 0.84White 26.0 (69) 28.1 (81) 28.2 (94) 1.6 (-31.3 to 50.1) 0.53Indian 28.8 (50) 23.8 (60) 32.1 (52) 0.8 (-5.6 to 7.7) 0.64RESIDENCE Urban 26.5 (400) 23.4 (403) 23.9 (399) -0.7 (-13.9 to 14.6) 0.45Rural 20.4 (168) 19.6 (159) 17.3 (123) -2.1 (-10.8 to 7.5) 0.07EDUCATION > Grade 12 13.6 (46) 21.5 (60) 21.4 (73) 4.3 (-33.5 to 63.7) 0.07Grade 12 29.9 (90) 21.3 (113) 20.0 (133) -4.9 (-26.2 to 22.5) 0.42Grades 1-11 26.9 (443) 23.1 (453) 22.3 (424) -1.9 (-13.5 to 11.3) 0.11No education 22.4 (75) 14.5 (48) 11.7 (21) -8.2 (-24.3 to 11.4) 0.01*EMPLOYMENT Unemployed 21.7 (147) 18.3 (116) 19.6 (146) 5.5 (-31.8 to 63.3) 0.23Housewife/student 20.0 (131) 17.5 (146) 15.8 (103) 5.9 (-28.2 to 56.3) 0.45Employed 30.0 (282) 27.9 (289) 26.1 (251) 4.4 (-38.8 to 77.9) 0.34MARITAL STATUS Never married 25.0 (187) 23.1 (189) 22.9 (198) -0.7 (-7.8 to 6.9) 0.59Divorced/Separated 21.1 (91) 21.5 (118) 20.2 (89) -0.7 (-7.7 to 6.9) 0.70Married 25.1 (289) 21.8 (255) 20.0 (220) -2.8 (-7.8 to 2.5) 0.05*

No school Grade1-11 Grade12 >Grade120

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Proportion of smokers per educational category using RYO Vs. factory cigarettes

in 2003

RYO Factory

No school Grade1-11 Grade12 >Grade120

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Proportion of smokers per educational category using RYO in 2011

RYO Factory

Segment 2003-2008: APC = 0.8 (-2.2 – 3.8); p=0.5Segment 2008-2012: APC = -3.6 (-7.7 – 0.7); p<0.01

Trends in smoking intensity

2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 20120

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

CPDedu0

CPDedu1-11

CPDedu12

CPDedu>12

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 20120

5

10

15

20

25

No Edu Grade 1-12 >Grade 12

Measures of educational inequality

2003 2007 2011

Rate ratio 1.70* 0.73 0.61

SII -5.10 +6 +11.71

RCI 0.84 1.35 1.94

Smoking trends among male adults

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 20120

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

No Edu Grade 1-12 >Grade 12

Trends in educational disparities in smoking among South African men

2003 2007 20110

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

4541.8

26.225.2

19.7

28.427.4

Lowest educatedHighest educated

Survey year

Sm

ok

ing

pre

va

len

ce

(%

)

Smoking trends among female adults

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 20120

2

4

6

8

10

12

No Edu Grade 1-12 >Grade 12

Trends in educational disparities in smoking among South African women

2003 2007 20110

2

4

6

8

10

12

1412.9

6.6

2.6

4

7.7

13.1

Lowest educatedHighest educated

Survey year

Sm

ok

ing

pre

va

len

ce

(%

)

Results contd……

• In general, no Significant decrease in smoking prevalence between among all (21.6% to 19.5%) and among those ≥25 years (24.5% to 21.5%) during 2003 to 2011

• But significant decline among those ≥25 years;

who had no education (22.4% to 11.7%; APC= -8.2; p<0.05 for linear trend).

• Decline was particularly significant among women ≥25 years who were uneducated (p< 0.01 for trend).

• No statistically significant changes were observed by age, race, residence and employment.

• Although aggregate smoking prevalence among women tended to be increasing, this was not statistically significant (p=0.07).

• However, a significant increase in smoking prevalence was observed among women with the highest level of education.

Discussion

• The observed greater decline in smoking among uneducated women may be related to greater sensitivity of this group to current policy environment, namely restrictions on public smoking and increases in cigarette prices, albeit modest increases.

Lower chances of being employed without schooling in 2011 vs. 2001

• The observed increasing trend among the most educated women might be related to this group increasing having more disposable income and being in managerial positions with associated strain, which has been associated with smoking (Gadinger et al., 2009).

• This increasing trend among women may also be related to industry targeting of women with products such as ‘lights’ and slim cigarettes (Carpenter, Wayne, & Connolly, 2005; Agaku,

Vardavas, Ayo-Yusuf, Alpert, & Connolly, 2014).

More women now working as professionals/managers

Women managers/technical professional have higher education

.Waterpipe/Hubblybubbly Electronic cigarette

39

~10% SA smokers use non-cigarette products

~ 3% SA smokers use E-cigarettes

Factors associated with current non-cigarette tobacco useCharacteristics OR (95% Conf. Interval)Age

< 35 years 1.0

≥ 35 years 0.53 (0.31-0.91)

Location

Urban 1.0

Rural 0.32 (0.15-0.71)

Education

<High school 1.0

≥ High school 1.83 (1.08-3.13)

Employment

Unemployed 1.0

Students & Others 2.12 (1.00-4.50)

Employed 1.01 (0.54-1.90)

40

Quit ratio over survey period and in relation to ever use of non-cigarette products

41

• This data suggests that users of any non-cigarette product in South Africa during 2010/2011 were young adults and of high socioeconomic status who use it concurrently with cigarettes.

• However, ever users of E-cigarettes were more likely to have quit smoking than ever users of combustible non-cigarette products, thus highlighting the need to further investigate the role of E-cigarette for tobacco control or tobacco maintenance in South Africa.

• In particular, the differential role of E-cigs among younger smokers (maintenance) compared to older smokers (quitting) needs to be investigated.

42

Conclusions• The disparity between the most educated and the least

educated has narrowed and possibly reversed in recent time as shown by all measures of inequality.

• Despite the significant improvements in socio-economic inequality, there is still a differential effect of current policies on smoking reduction by gender, with uneducated men being less likely to have experienced a decline as compared to women.

• Need to more aggressively pursue the tax policies that focuses on reducing the affordability of tobacco products so as to arrest the increasing trend in smoking among the most educated women.

THANK YOU!

Acknowledgements: This study was supported by the

American Cancer Society (Grant contract NHINTLTAA02)