Term Paper Project1

Transcript of Term Paper Project1

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

1/31

TERM PAPER PROJECT

Inception of An Micro credit institution and Structural Analysis

Of Micro Finance In India.

Under The Guidance Of :-

Prof. Namita Sahay &Prof. R.B.L.Goswami.

Presented by;

Abhishek Kumar Sinha (52),Shudhanshu Shekhar Rai(55),Deepak Dwivedi (53),Ankita Srivastava

(60),ShraddhaVerma (57),Abhishek Kumar Singh (56),Swati

Ranjan Naidu (),Ankit Obediah (51),Saurabh Bajaj (54),Vivek

Kumar (59).

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

2/31

Acknowledgement

The authors gratefully acknowledge the guidance

provided by the project guides Prof. R.B.L.Goswami and

Prof. Namita sahay throughout the project.

The authors also wish thank to all other faculty

members for their valuable suggestions and directions.

The authors also thank to their batch mates for

providing constant encouragement, support and valuable

suggestions during the completion of project.

: Group-06

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

3/31

MicrofinanceMicrofinance is the provision of financial services to low income clients, includingconsumers and the self -employed, who traditionally lack access to banking and relatedservices.

More broadly, it is a movement whose object is "a world in which as many poor and near-

poor households as possible have permanent access to an appropriate range of high qualityfinancial services, including not just credit but also savings, insurance, and fund transfers."Those who promote microfinance generally believe that such access will help poor peopleout of poverty.

The Role of Microfinance

Microcredit is undoubtedly the most visible innovation in anti-poverty policy in the last half

century. In the three decades, the number of microcredit borrowers has crossed 150 millions. Themajority had no access to credit from banks before microcredit came to them. Nowadays, people

borrow from MFIs at significantly lower (though often high by US standards) rates. At the sametime MFIs have managed to find ways to be financially sustainable and to keep growing fast.This

is itself is a remarkable achievement. Very little works in many of these countries in terms ofdelivering to the poor; some previous attempts to deliver credit, through state-run banks, for

example, collapsed in the face of widespread corruption and defaults. Many microcreditinstitutions are led by dynamic entrepreneurs who have mastered quality service delivery.

However, many see microcredit as much more than a financial instrument: it has been suggested

that it has the potential to be entirely transformative. There is an influential view that argues that,by putting more spending power in the hands of poor families, and, perhaps more importantly, in

the hands of women, microcredit can expand investment in child health and education, empowerwomen and reduce discrimination against them. There is even the suggestion that, by making

people feel that their lives could be better and giving women independent access to capital,microcredit could fight the AIDS epidemic.Unfortunately, till very recently, there was little

rigorous evidence on either sideis microcredit transformative or ruinous? However this ischanging now, thanks to the courage and vision of a few leading MFIs (including Spandana in

India, Al Amana in Morocco, First Macro Bank in the Philippines, Compartamos in Mexico) thathave allowed researchers (each of us was involved in one or more of these) to evaluate

rigorously the impact of their programs.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

4/31

The two programs evaluated are very different. First Macro Bank provides loan to existing business owners, male or female, on an individual basis.

In the Philippines, male-owned businesses increase profits, although female-owned businessesdo not. In India, borrowers who already own a business buy assets for their business. One

borrower out of eight starts a business they would not have started otherwise. Others buy

durables for their homes. However, there is no evidence that microcredit has any effect on health,education, or womens empowerment, at least right now, eighteen months after they got theloans. On the other hand, there is also no evidence that people are behaving irresponsibly. Indeed

in India we have evidence of people giving up some of the little daily pleasures of life (like tea,snacks, betel leaves and tobacco), to pay for bigger things that they could not previously afford

(carts for their business, televisions for their homes).

Many seem to think that this is not enough. However, as we see it, microcredit seems to havedelivered exactly what a successful new financial product is supposed deliverallowing people

to make large purchases that they would not have been able to otherwise. The fact that somepeople expected much more from it (and perhaps they are right, may be it will just take longer),

is perhaps inevitable given how eager the world is to find that one magic bullet that would finallysolve poverty. But to actually blame microcredit for not promoting the immunization of

children is no different from blaming immunization campaigns for not generating newbusinesses.

Definition of Micro Credit:

Micro credit is the name given to extremely small loans made to poor borrowers.A typical micro credit scheme involves the extension of an unsecured,Commercial - type loan at interest to a poverty stricken borrower. The definition of poverty

stricken varies with the situation, but in Bangladesh the typical definition is a borrowerwho owns less than 0.5 acres of land and relies on wages for all income. Loans aredisbursed in a group setting to poor borrowers, with some amount of non-credit assistancealso being made available. The non-credit assistance typically ranges from skills training tomarketing assistance to lessons in social empowerment.Microfinance is now accepted worldwide as one of the potent tools of poverty alleviation.Awarding of the Nobel Prize (2006) to Dr. Muhammad Yunus and Grameen Bank hasrekindled interest in this form of banking services to the extent that the UN and even themulti-lateral funding institutions are considering it as an effective tool for povertyreduction. However there has always been a group of strident critics who continue todebunk the claim of the Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) in this respect. It would therefore

be worthwhile to try to analyses this form of service in an impassioned way.One can start by looking at how it works. Obviously the main instrument is micro credit orsmall loan, which is offered to clients at a fixed service charge to be repaid in equalinstallments over a fixed period of time. The loan is collateral-free. Some MFIs stressesgroup liability while others give this loan on individual basis but who should however be amember of a small group. The criteria for membership is simple, a cap on the amount ofasset they own makes them equal in each others eyes. However the products orinstruments the MFIs now offer has expanded to include small business/enterprise loans,

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

5/31

hardcore poor loans, supplementary loan to the members within the same family.Importance is given to the savings, and in addition to the mandatory savings, members areoffered a variety savings products that they can avail on voluntary basis.Some MFIs have instituted insurance schemes at very low premiums to protect theborrowers in the event of sudden death where the outstanding amount including interest is

written off. Members are also entitled to taking recourse to a security fund where they cancontribute a fixed amount, say, tk.10 per week where on maturity after eight or ten yearsthey or their nominee in the event of their death are entitled to six times the principalamount. male members get three to four times after four years. The main critique againstthis form of credit is the service charge or the rate of interest charged.This usually varies from 12 percent to 16 per cent among different MFIs. The principal andthe interest are calculated over the period the loan is given, which is to be repaid as a fixamount on a weekly on a monthly basis. The bone of contention lies here. Critics point outthat whereas the services charge or the rate of interest is declared to be around 12 percentto 16 per cent. The effective rates come out to be around 25 percent to 30 per cent. This istrue, but what one misses is these calculation is the fact that those people who are left out

of the institutional banking sector because of the inability to furnish any collateral as wellas hassle of paper works and the shuttling between the bank branches and their place ofabode, MFIs reach this services at the door step of the beneficiaries through the fieldworkers. Moreover the loan is to be paid on a weekly or monthly basis (in some cases ofbusiness or enterprise loan) the burden on the members in tolerable. This becomes evidentwhen one looks the repayment rate of the MFIs, which varies between 90 per cent and 100percent. The lesson here is that the poor who have so long been denied carried are nowusing this tool of augment their lot. They do so by utilizing the credit income generatingactivities (IGA) that also contribute to employment generation

Abstract

More than subsidies poor need access to credit. Absence of formal employment make them

non `bankable'. This forces them to borrow from local moneylenders at exhorbitant

interest rates. Many innovative institutional mechanisms have been developed across the

world to enhance credit to poor even in the absence of formal mortgage. The present paper

discusses conceptual framework of a microfinance institution in India. The successes and

failures of various microfinance institutions around the world have been evaluated andlessons learnt have been incorporated in a model microfinance institutional mechanism for

India.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

6/31

Micro-finance and Poverty Alleviation

Most poor people manage to mobilize resources to develop their enterprises and theirdwellings slowly over time. Financial services could enable the poor to leverage theirinitiative, accelarating the process of building incomes, assets and economic security.

However, conventional finance institutions seldom lend down-market to serve the needs oflow-income families and women-headed households. They are very often denied access tocredit for any purpose, making the discussion of the level of interest rate and other terms offinance irrelevant. Therefore the fundamental problem is not so much of unaffordableterms of loan as the lack of access to credit itself (Kim 1995).

The lack of access to credit for the poor is attributable to practical difficulties arising fromthe discrepancy between the mode of operation followed by financial institutions and theeconomic characteristics and financing needs of low-income households. For example,commercial lending institutions require that borrowers have a stable source of income outof which principal and interest can be paid back according to the agreed terms. However,

the income of many self employed households is not stable, regardless of its size. A largenumber of small loans are needed to serve the poor, but lenders prefer dealing with largeloans in small numbers to minimize administration costs. They also look for collateral witha clear title - which many low-income households do not have. In addition bankers tend toconsider low income households a bad risk imposing exceedingly high informationmonitoring costs on operation.

Over the last ten years, however, successful experiences in providing finance to smallentrepreneur and producers demonstrate that poor people, when given access toresponsive and timely financial services at market rates, repay their loans and use theproceeds to increase their income and assets. This is not surprising since the only realistic

alternative for them is to borrow from informal market at an interest much higher thanmarket rates. Community banks, NGOs and grassroot savings and credit groups around theworld have shown that these microenterprise loans can be profitable for borrowers and forthe lenders, making microfinance one of the most effective poverty reducing strategies.

To the extent that microfinance institutions become financially viable, self sustaining, andintegral to the communities in which they operate, they have the potential to attract moreresources and expand services to clients. Despite the success of microfinance institutions,only about 2% of world's roughly 500 million small entrepreneur is estimated to haveaccess to financial services (Barry et al. 1996). Although there is demand for credit by poorand women at market interest rates, the volume of financial transaction of microfinance

institution must reach a certain level before their financial operation becomes selfsustaining. In other words, although microfinance offers a promising institutional structureto provide access to credit to the poor, the scale problem needs to be resolved so that it canreach the vast majority of potential customers who demand access to credit at marketrates. The question then is how microenterprise lending geared to providing short termcapital to small businesses in the informal sector can be sustained as an integral part of thefinancial sector and how their financial services can be further expanded using theprinciples, standards and modalities that have proven to be effective.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

7/31

To be successful, financial intermediaries that provide services and generate domesticresources must have the capacity to meet high performance standards. They must achieveexcellent repayments and provide access to clients. And they must build toward operatingand financial self-sufficiency and expanding client reach. In order to do so, microfinanceinstitutions need to find ways to cut down on their administrative costs and also to

broaden their resource base. Cost reductions can be achieved through simplified anddecentralized loan application, approval and collection processes, for instance, throughgroup loans which give borrowers responsibilities for much of the loan application process,allow the loan officers to handle many more clients and hencee reduce costs (Otero et al.1994).

Microfinance institutions can broaden their resource base by mobilizing savings, accessingcapital markets, loan funds and effective institutional development support. A logical wayto tap capital market is securitization through a corporation that purchases loans made bymicroenterprise institutions with the funds raised through the bonds issuance on thecapital market. There is atleast one pilot attempt to securitize microfinance portfolio along

these lines in Ecuador. As an alternative, Banco Sol of Bolivia issued a certificate of depositwhich are traded in Bolivian stock exchange. In 1994, it also issued certificates of deposit inthe U.S. (Churchill 1996). The Foundation for Cooperation and Development of Paraguayissued bonds to raise capital for microenterprise lending (Grameen Trust 1995).

Savings facilities make large scale lending operations possible. On the other hand, studiesalso show that the poor operating in the informal sector do save, although not in financialassets, and hence value access to client-friendly savings service at least as much access tocredit. Savings mobilization also makes financial institutions accountable to localshareholders. Therefore, adequate savings facilities both serve the demand for financialservices by the customers and fulfill an important requirement of financial sustainability to

the lenders. Microfinance institutions can either provide savings services directly throughdeposit taking or make arrangements with other financial institutions to provide savingsfacilities to tap small savings in a flexible manner (Barry 1995).

Convenience of location, positive real rate of return, liquidity, and security of savings areessential ingradients of successful savings mobilization (Christen et al. 1994).

Once microfinance institutions are engaged in deposit taking in order to mobilizehousehold savings, they become financial intermediaries. Consequently, prudentialfinancial regulations become necessary to ensure the solvency and financial soundness ofthe institution and to protect the depositors. However, excessive regulations that do not

consider the nature of microfinance institution and their operation can hamper theirviability. In view of small loan size, microfinance institutions should be subjected to aminimum capital requirement which is lower than that applicable to commercial banks. Onthe other hand, a more stringent capital adequacy rate (the ratio between capital and riskassets) should be maintained because microfinance institutions provide uncollateralizedloans.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

8/31

Governments should provide an enabling legal and regulatory framework whichencourages the development of a range of institutions and allows them to operate asrecognized financial intermediaries subject to simple supervisory and reportingrequirements. Usury laws should be repelled or relaxed and microfinance institutionsshould be given freedom of setting interest rates and fees in order to cover operating and

finance costs from interest revenues within a reasonable amount of time. Governmentcould also facilitate the process of transition to a sustainable level of operation byproviding support to the lending institutions in their early stage of development throughcredit enhancement mechanisms or subsidies.

One way of expanding the successful operation of microfinance institutions in the informalsector is through strengthened linkages with their formal sector counterparts. A mutuallybeneficial partnership should be based on comparative strengths of each sectors. Informalsector microfinance institutions have comparative advantage in terms of small transactioncosts achieved through adaptability and flexibility of operations (Ghate et al. 1992). Theyare better equipped to deal with credit assessment of the urban poor and hence to absorb

the transaction costs associated with loan processing. On the other hand, formal sectorinstitutions have access to broader resource-base and high leverage through depositmobilization (Christen et al. 1994).

Therefore, formal sector finance institutions could form a joint venture with informalsector institutions in which the former provide funds in the form of equity and the laterextends savings and loan facilities to the urban poor. Another form of partenership caninvolve the formal sector institutions refinancing loans made by the informal sectorlenders. Under these settings, the informal sector institutions are able to tap additionalresources as well as having an incentive to exercise greater financial discipline in theirmanagement.

Microfinance institutions could also serve as intermediaries between borrowers and the

formal financial sector and on-lend funds backed by a public sector guarantee (Phelps

1995). Business-like NGOs can offer commercial banks ways of funding micro

entrepreneurs at low cost and risk, for example, through leveraged bank-NGO-client credit

lines. Under this arrangement, banks make one bulk loan to NGOs and the NGOs packages it

into large number of small loans at market rates and recover them (Women's World

Banking 1994).

Financial needs and financial services.

In developing economies and particularly in the rural areas, many activities that would beclassified in the developed world as financial are not monetized: that is, money is not used tocarry them out. Almost by definition, poor people have very little money. But circumstances

often arise in their lives in which they need money or the things money can buy.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

9/31

Poor people find creative and often collaborative ways to meet these needs, primarily throughcreating and exchanging different forms of non-cash value. Common substitutes for cash vary

from country to country but typically include livestock, grains, jewelry and precious metals.

As Marguerite Robinson describes in The Microfinance Revolution, the 1980s demonstrated that

"microfinance could provide large-scale outreach profitably," and in the 1990s, "microfinance began to develop as an industry" (2001, p. 54). In the 2000s, the viable, commercialmicrofinance sector in the last few decades, several issues remain that need to be addressed

before the industry will be able to satisfy massive worldwide demand. The obstacles orchallenges to building a sound commercial microfinance industry include:

y Inappropriate donor subsidiesy Poor regulation and supervision of deposit-taking MFIsy Few MFIs that meet the needs for savings, remittances or insurancey Limited management capacity in MFIsy Institutional inefficienciesy Need for more dissemination and adoption of rural, agricultural microfinance methodologies

microfinance industry's objective is to satisfy the unmet demand on a much larger scale, and to

play a role in reducing poverty. While much progress has been made in developing a

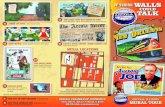

Top 50 Micro Finance Institutions

Rank Name Country

1 ASA Bangladesh

2 Bandhan (Society and NBFC) India

3 Banco do Nordeste Brazil

4 Fundacin Mundial de la Mujer Bucaramanga Colombia

5 FONDEP Micro-Crdit Morocco

6 Amhara Credit and Savings Institution Ethiopia

7 Banco Compartamos, S.A., Institucin de Banca Mltiple Mexico

8 Association Al Amana for the Promotion of Micro-Enterprises Morocco Morocco

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

10/31

9 Fundacin Mundo Mujer Popayn Colombia

10 Fundacin WWB Colombia - Cali Colombia

11 Consumer Credit Union 'Economic Partnership' Russia

12 Fondation Banque Populaire pour le Micro-Credit Morocco

13 Microcredit Foundation ofIndia India

14 EKI Bosnia and Herzegovina

15 Saadhana Microfin Society India

16 Jagorani Chakra Foundation Bangladesh

17 Grameen Bank Bangladesh

18 Partner Bosnia and Herzegovina

19 Grameen Koota India

20 Caja Municipal de Ahorro y Crdito de Cusco Peru

21 Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee Bangladesh

22 AgroInvest Serbia

23 Caja Municipal de Ahorro y Crdito de Trujillo Peru

23 Sharada's Women's Association for Weaker Section India

24 MIKROFIN Banja Luka Bosnia and Herzegovina

25 Khan Bank (Agricultural Bank of Mongolia LLP) Mongolia

26 INECO Bank Armenia

27 Fondation Zakoura Morocco

28 Dakahlya Businessmen's Association for Community Development Egypt

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

11/31

29 Asmitha Microfin Ltd. India

30 Credi Fe Desarrollo Microempresarial S.A. Ecuador

31 Dedebit Credit and Savings Institution Ethiopia

32 MI-BOSPO Tuzla Bosnia and Herzegovina

33 Fundacion Para La Promocion y el Desarrollo Nicaragua

34 Kashf Foundation Pakistan

35 Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women Bangladesh

36 enda inter-arabe Tunisia

37 Kazakhstan Loan Fund Kazakhstan

38 Integrated Development Foundation Bangladesh

39 Microcredit Organization Sunrise Bosnia and Herzegovina

40 FINCA - ECU Ecuador

41 Caja Municipal de Ahorro y Crdito de Arequipa Peru

42 Crdito con Educacin Rural Bolivia

43 BESA Fund Albania

44 SKS Microfinance Private Limited India

45 Development and Employment Fund Jordan

46 Programas para la Mujer - Peru Peru

47 Kreditimi Rural i Kosoves LLC (formerly Rural Finance Project of Kosovo) Kosovo

48 BURO, formerly BURO Tangail Bangladesh

49 Opportunity Bank A.D. Podgorica Serbia

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

12/31

50 Sanasa Development Bank

Micro finance scenario in India :

Since 2000, commercial banks including Regional Rural Banks have been providing funds

.The first thing to remember is that in India the history of rural credit, poverty alleviation

and microfinance are inextricably interwoven. Any effort to understand one without

reference to the others, can only lead to a fragmented understanding. The forces and

compulsions that shaped the initiatives in these areas are best understood in context of

State and banking policy over time. Thus, for e.g., there were peasant riots in the Deccan inthe late 19th Century on account of coercive alienation of land by moneylenders. The policy

response of the British Government to this problem of rural indebtedness was to initiate

the process of organization of cooperative societies as alternative institutions for providing

credit to the farmers as also to ensure settled conditions in the rural areas, so necessary for

a colonial power to sustain itself.

In the development strategy adopted by independent India, institutional credit was

perceived as a powerful instrument for enhancing production and productivity and for

alleviating poverty. The formal view was that lending to the poor should be a part of the

normal business of banks, Simple as that. To achieve the objectives of production,

productivity and poverty alleviation, the policy on rural credit was to ensure that sufficient

and timely credit was reached as expeditiously as possible to as large a segment of the rural

population at reasonable rates of interest.

The strategy devised for this purpose comprised :

Expansion of the institutional structure,

Directed lending to disadvantaged borrowers and sectors and

Interest rates supported by subsidies.

The institutional vehicles chosen for this were cooperatives, commercial banks and

Regional Rural Banks [RRBs].

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

13/31

Between 1950 & 1969, the emphasis was on the promoting of cooperatives. The

nationalization of the major commercial banks in 1969 marks a watershed in as much as

from this time onwards the focus shifted from the cooperatives as the sole providers of

rural credit to the multi agency approach. This also marks the beginning of the phenomenalexpansion of the institutional structure in terms of commercial bank branch expansion in

the rural and semi-urban areas. For the next decade and half, the Indian banking scene was

dominated by this expansion. However, even as this expansion was taking place, doubts

were being raised about the systemic capability to reach the poor. Regional Rural Banks

were set up in 1976 as low cost institutions mandated to reach the poorest in the credit-

deficient areas of the country. In hindsight it may not be wrong to say that RRBs are

perhaps the only institutions in the Indian context which were created with a specific

poverty alleviation - microfinance mandate. During this period, intervention of the

Central Bank (Reserve Bank of India) was essential to enable the system to overcomefactors which were perceived as discouraging the flow of credit to the rural sector such as

absence of collateral among the poor, high cost of servicing geographically dispersed

customers, lack of trained and motivated rural bankers, etc. The policy response was multi

dimensional and included special credit programmes for channeling subsidized credit to

the rural sector and operationalising the concept ofpriority sector. The later was evolved

in the late sixties to focus attention on the credit needs of neglected sectors and under-

privileged borrowers.

The strategies followed are as follow:

*helped to build a broad based institutional infrastructure for the delivery and deployment

of credit.

*ensured a wider physical access of financial services to the poor.

*Access in terms of rural branches increased from 1,833 in 1969 to around 32,200 at

present,

*the population per rural branch declined from 2,01,854 in 1969 to around 16,000 atpresent.

*The proportion of borrowings of rural households from institutional sources increased

from 7 per cent in 1951 to more than 60 per cent at present.

*This significant increase in the credit flow from institutional sources gave rise to a strong

sense of expectation from the state agencies. However, this expectation could not be

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

14/31

sustained because the emphasis, among others, was on achieving certain quantitative

targets. As a result, inadequate attention was paid to the qualitative aspects of lending

leading to loan defaults and erosion of repayment ethics by all categories of borrowers. The

end result was a disturbing growth in over dues, which not only hampered the recycling of

scarce resources of banks, but also affected profitability and viability of financial

institutions. This not only blunted the desire of banks to lend to the poor but also the

development impact of rural finance.

*This was the position on the eve of reforms, which marks the second watershed, in the

history of rural credit.

*The basic aim of the financial sector reforms was to improve the efficiency and

productivity of all credit institutions including rural financial institutions (RFIs) whose

financial health was far from satisfactory. In regard to RFIs, the reforms sought to enhancethe areas of commercial freedom, increase their outreach to the poor and stimulate

additional flows to the sector. The reforms included far reaching changes in the incentive

regime through liberalising interest rates for cooperatives and RRBs, relaxing controls on

where, for what purpose and for whom RFIs could lend, reworking the sub-heads under the

priority sector, introducing prudential norms and restructuring and recapitalising of RRBs.

The object of this narrative is to bring home to you two facts and four

effects.

The two facts are:

*From the time of independence, the overriding concern of development policy makers has

been to find ways and means to finance the poor and reduce the burden upon them.

*Between the concern of the policy makers and the quality of the effort, however, there has

been a gap. The efforts made were not able to achieve the success envisaged for a variety of

reasons mainly, defects in policy design, infirmities in implementation and the inability of

the government of the day to desist from resorting to measures such as loan waivers.

The four consequences flowing from these facts are:

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

15/31

That the banking system - was not able to internalise lending to the poor as a viable activity

but only as a social obligation something that had to be done because the authorities

wanted it so.

This was translated into the banking language of the day : Loans to the poor were part of

social sector lending and not commercial lending ; the poor were not borrowers, they werebeneficiaries ; poor beneficiaries did not avail of loans they availed of assistance.

The language of the time resulted in an attitude of carefully disguised cynicism towards the

poor. The attitude was that the poor are not bankable, that they can never be bankable, that

commercial principles cannot be applied in lending to the poor, that what the poor require

are not loans but charity. Once this mindset hardened it became more and more difficult

for commercial bankers to accept that lending to the poor could be a viable activity. It is

significant to note that the system had to wait for almost a decade for the concept of

microfinance to become credible.

Micro Finance : The Paradigm

The financial sector reforms motivated policy planners to search for products and

strategies for delivering financial services to the poor microfinance - in a sustainable

manner consistent with high repayment rates. The search for these alternatives started

with internal introspection regarding the arrangements which the poor had been

traditionally making to meet their financial services needs. I was found that the poor

tended to and could be induced to - come together in a variety of informal ways for

pooling their savings and dispensing small and unsecured loans at varying costs to group

members on the basis of need. The essential genius of NABARD in the Bank SHGprogramme was to recognize this empirical observation that had been catalysed by NGOs

and to create a formal interface of these informal arrangements of the poor with the

banking system. This is the beginning of the story of the Bank-SHG Linkage Programme.

SHG - Bank Linkage Programme

The SHG Bank Linkage Programme started as an Action Research Project in 1989. In

1992, the findings led to the setting up of a Pilot Project. The pilot project was designed as a

partnership model between three agencies, viz., the SHGs, banks and Non Governmental

Organisations (NGOs). SHGs were to facilitate collective decision-making by the poor andprovide 'doorstep banking; Banks as wholesalers of credit, were to provide the resources

and NGOs were to act as agencies to organise the poor, build their capacities and facilitate

the process of empowering them.

Achievements

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

16/31

The programme has come a long way from the pilot stage of financing 500 SHGs

across the country. Cumulatively, they have so far accessed credit of Rs.6.86 billion.

About 24 million poor households have gained access to the formal banking system

through the programme.

The main findings are that:

i. Microfinance has reduced the incidence of poverty through increase in income,enabled the poor to build assets and thereby reduce their vulnerability.

ii. It has enabled households that have access to it to spend more on education than non-

client households. Families participating in the programme have reported better schoolattendance and lower drop out rates.

iii. It has empowered women by enhancing their contribution to household income,

increasing the value of their assets and generally by giving them better control over

decisions that affect their lives.

iv. In certain areas it has reduced child mortality, improved maternal health and the ability

of the poor to combat disease through better nutrition, housing and health - especially

among women and children.

v. It has contributed to a reduced dependency on informal money lenders and other non-institutional sources.

vi. It has facilitated significant research into the provision of financial services for the poor

and helped in building capacity at the SHG level.

vii. Finally it has offered space for different stakeholders to innovate, learn and replicate. As

a result, some NGOs have added micro-insurance products to their portfolios, a couple of

federations have experimented with undertaking livelihood activities and grain banks have

been successfully built into the SHG model in the eastern region. SHGs in some areas have

employed local accountants for keeping their books; and IT applications are now beingexplored by almost all for better MIS, accounting and internal controls.

(1) The first point is that the poor are bankable. Sounds simple, but, when we view this in

context of the attitudinal constraints which characterized bankers on the eve of the linkage

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

17/31

programme, one realizes what an immense learning point this has been. But, for this we

would still have been in the middle ages.

(2) The second point is that the poor, organized into SHGs, are ready and willing to partner

mainstream financial institutions and banks on their part find their SHG portfolios safe

and performing.

(3) The third point is that despite being contra intuitive, the poor can and do save in a

variety of ways and the creative harnessing of such savings is a key design feature and

success factor.

(4) The fourth point is that successful programmes are those that afford opportunity to

stakeholders to contribute to it on their own terms. When this happens, the chances of

success multiply manifold. This has been possible in the Bank - SHG linkage programme on

account of the space given to each partner and the synergy built in the programme between

the informal sector comprising the poor and their SHGs, the semi-formal sector comprisingNGOs, and the formal sector comprising banks, government and the development agencies.

(5) Yet another learning point has been that when a programme is built on existing

structures, it leverages all strengths. Thus, because the Bank- SHG programme is built upon

the existing banking infrastructure, it has obviated the need for the creation of a new

institutional set-up or introduction of a separate legal and regulatory framework. Since

financial resources are sourced from regular banking channels and members savings, the

programme bypasses issues relating to regulation and supervision. Lastly, since the Group

acts as a collateral substitute, the model neatly addresses the irksome problem of provision

of collateral by the poor.

(6) The last learning point is that central banks, apex development banks and governments

have an important role in creating the enabling environment and putting appropriate

policies and interventions in position which enable rapid upscaling of efforts consistent

with prudential practices. But for this opportunity, no innovation can take place.

Challenges :

Regional Imbalances The first challenge is the skewed distribution of SHGs across States.

About 60% of the total SHG credit linkages in the country are concentrated in the SouthernStates. However, in States which have a larger share of the poor, the coverage is

comparatively low. The skewed distribution is attributed to the over zealous support

extended by some the State Governments to the programme. Skewed distribution of NGOs

and

Local cultures & practices.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

18/31

NABARD has since identified 13 states where the volumes of SHGs linked are low and has

already initiated steps to correct the imbalance.

From credit to enterprise :-

The second challenge is that having formed SHGs and having linked them to banks, how canthey be induced to graduate into matured levels of enterprise, how they be induced to

factor in livelihood diversification, how can they increase their access to the supply chain,

linkages to the capital market and to appropriate/ production and processing technologies.

A spin off of this challenge is how to address the investment capital requirements of

matured SHGs, which have met their consumption needs and are now on the threshold of

taking off into Enterprise. The SHG Bank-Linkage programme needs to introspect

whether it is sufficient for SHGs to only meet the financial needs of their members, or

whether there is also a further obligation on their part to meet the non-financial

requirements necessary for setting up businesses and enterprises. In my view, we mustmeet both.

Quality of SHGs The third challenge is how to ensure the quality of SHGs in an

environment of exponential growth. Due to the fast growth of the SHG Bank Linkage

Program, the quality of SHGs has come under stress. This is reflected particularly in

indicators such as the poor maintenance of books and accounts etc. The deterioration in

the quality of SHGs is explained by a variety of factors including

The intrusive involvement of government departments in promoting groups,

Inadequate long-term incentives to NGOs for nurturing them on a sustainable basis and

Diminishing skill sets on part of the SHG members in managing theirgroups.

In my assessment, significant financial investment and technical support is required for

meeting this challenge.

Impact of SGSY Imitation is the best form of flattery but not always. The success of the

programme has motivated the Government to borrow its design features and incorporate

them in their poverty alleviation programme. This is certainly welcome but for the fact that

the Governments Programme (SGSY) has an inbuilt subsidy element which tends to attract

linkage group members and cause migration generally for the wrong reasons. Also, micro

level studies have raised concerns regarding the process through which groups are formed

under the SGSY and have commented that in may cases members are induced to come

together not for self help, but for subsidy. I would urge a debate on this, as there is a need

to resolve the tension between SGSY and linkage programme groups. One way out of the

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

19/31

impasse would be to place the subsidy element in the SGSY programme with NABARD for

best utilisation for providing indirect subsidy support for purposes such as sensitisation,

capacity building, exposure visits to successful models, etc.

Role of State Governments A derivative of the above is perhaps the need to extend

the above debate to understanding and defining the role of the State Governments vis--vis

the linkage programme. Lets be clear: on the one hand, the programme would not have

achieved its outreach and scale, but for the proactive involvement of the State

Governments; on the other hand, many State Governments have been overzealous to

achieve scale and access without a critical assessment of the manpower and skill sets

available with them for forming, and nurturing groups and handholding and maintaining

them over time.

Emergence of Federations The emergence of SHG Federations has thrown up another

challenge. On the one hand, such federations represent the aggregation of collective

bargaining power, economies of scale, and are fora for addressing social & economic issues;

on the other hand there is evidence to show that every additional tier, in addition to

increasing costs, tends to weaken the primaries. There is a need to study the best practices

in the area and evolve a policy by learning from them.

While we are upbeat about the success achieved and the potential that the SHG Linkage

programme offers, we need to be realistic and not to view this instrument as a one-stop

solution for all developmental problems. SHGs are local institutions having an inherent

potential to flower as decentralised platform for development, but multiple expectations

could overload them and impair their long-term sustainability. Second, in focusing on the

poor let us not forget the rest. The rural sector is a large field and even today the need for

good old-fashioned rural credit and investment in agriculture and infrastructure continues

with the same rigour as yesterday.

Emergence of MFIs :

Having indicated my thoughts on the SHG-Bank Linkage programme, may I now briefly

turn to the MFI model ? MFIs are an extremely heterogenous group comprising NBFCs,

societies, trusts and cooperatives. They are provided financial support from external

donors and apex institutions including the Rashtriya Mahila Kosh (RMK), SIDBI Foundation

for micro-credit and NABARD and employ a variety of ways for credit delivery.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

20/31

MFIs for on lending to poor clients. Though initially, only a handful of NGOs were into

financial intermediation using a variety of delivery methods, their numbers have increased

considerably today. While there is no published data on private MFIs operating in the

country, the number of MFIs is estimated to be around 800. One set of data which I haveindicate that not more than a dozen MFIs have an outreach of 1,00,000 microFinance

clients. A large majority of them operate on much smaller scale with clients ranging

between 500 and 1,500 per MFI. It is estimated that the MFIs share of the total institution-

based micro-credit portfolio is about 8%.

5. MFIs : Critical Issues

MFIs can play a vital role in bridging the gap between demand & supply of financial

services if the critical challenges confronting them are addressed.

Sustainability : The first challenge relates to sustainability. It has been reported in

literature that the MFI model is comparatively costlier in terms of delivery of financial

services. An analysis of 36 leading MFIs2 by Jindal & Sharma shows that 89% MFIs sample

were subsidy dependent and only 9 were able to cover more than 80% of their costs. This

is partly explained by the fact that while the cost of supervision of credit is high, the loan

volumes and loan size is low. It has also been commented that MFIs pass on the higher cost

of credit to their clients who are interest insensitive for small loans but may not be so as

loan sizes increase. It is, therefore, necessary for MFIs to develop strategies for increasingthe range and volume of their financial services.

Lack of Capital The second area of concern for MFIs, which are on the growth path, is that

they face a paucity of owned funds. This is a critical constraint in their being able to scale

up. Many of the MFIs are socially oriented institutions and do not have adequate access to

financial capital. As a result they have high debt equity ratios. Presently, there is no reliable

mechanism in the country for meeting the equity requirements of MFIs. As you know, the

Micro Finance Development Fund (MFDF), set up with NABARD, has been augmented and

re-designated as the Micro Finance Development Equity Fund (MFDEF). This fund is

expected to play a vital role in meeting the equity needs of MFIs.

Borrowings In comparison with earlier years, MFIs are now finding it relatively easier to

raise loan funds from banks. This change came after the year 2000, when RBI allowed

banks to lend to MFIs and treat such lending as part of their priority sector-funding

obligations. Private sector banks have since designed innovative

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

21/31

2 Issues in Sustainability of MFIs, Jindal & Sharma products such as the Bank Partnership

Model to fund MFIs and have started viewing the sector as a good business proposition.

Being an ex-regulator I may be forgiven for reminding banks that they need to be most

careful when they feel most optimistic. At a time when they are enthusiastic about MFIs,banks would do well to find the right technologies to assess the risk of funding MFIs. They

would also benefit by improving their skill sets for appraising such institutions and

assessing their credit needs. I believe that appropriate credit rating of MFIs will help in

increasing the comfort level of the banking system. It may be of interest to note that

NABARD has put in position a scheme under which 75% of the cost of the rating exercise

will be borne by it.

Capacity of MFIs - It is now recognised that widening and deepening the outreach of the

poor through MFIs has both social and commercial dimensions. Since the sustainability of

MFIs and their clients complement each other, it follows that building up the capacities of

the MFIs and their primary stakeholders are preconditions for the successful delivery of

flexible, client responsive and innovative microfinance services to the poor. Here,

innovations are important both of social intermediation, strategic linkages and new

approaches centered on the livelihood issues surrounding the poor, and the re-engineering

of the financial products offered by them as in the case of the Bank Partnership model.

Bank Partnership Model :

This model is an innovative way of financing MFIs. The bank is the lender and the MFI acts

as an agent for handling items of work relating to credit monitoring, supervision and

recovery. In other words, the MFI acts as an agent and takes care of all relationships with

the client, from first contact to final repayment. The model has the potential to significantly

increase the amount of funding that MFIs can leverage on a relatively small equity base.

A sub - variation of this model is where the MFI, as an NBFC, holds the individual loans on

its books for a while before securitizing them and selling them to the bank. Suchrefinancing through securitization enables the MFI enlarged funding access. If the MFI

fulfils the true sale criteria, the exposure of the bank is treated as being to the individual

borrower and the prudential exposure norms do not then inhibit such funding of MFIs by

commercial banks through the securitization structure.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

22/31

Banking Correspondents :

The proposal ofbanking correspondents could take this model a step further extending it

to savings. It would allow MFIs to collect savings deposits from the poor on behalf of the

bank. It would use the ability of the MFI to get close to poor clients while relying on the

financial strength of the bank to safeguard the deposits. Currently, RBI regulations do notallow banks to employ agents for liability - i.e deposit - products. This regulation evolved at

a time when there were genuine fears that fly-by-night agents purporting to act on behalf

of banks in whom the people have confidence could mobilize savings of gullible public and

then vanish with them. It remains to be seen whether the mechanics of such relationships

can be worked out in a way that minimizes the risk of misuse.

Service Company Model :

In this context, the Service Company Model developed by ACCION and used in some of the

Latin American Countries is interesting. The model may hold significant interest for state

owned banks and private banks with large branch networks. Under this model, the bank

forms its own MFI, perhaps as an NBFC, and then works hand in hand with that MFI to

extend loans and other services. On paper, the model is similar to the partnership model:

the MFI originates the loans and the bank books them. But in fact, this model has two very

different and interesting operational features :

(a) The MFI uses the branch network of the bank as its outlets to reach clients. This allows

the client to be reached at lower cost than in the case of a standalone MFI. In case of banks

which have large branch networks, it also allows rapid scale up. In the partnership model,

MFIs may contract with many banks in an arms length relationship. In the service company

model, the MFI works specifically for the bank and develops an intensive operational

cooperation between them to their mutual advantage.

(b) The Partnership model uses both the financial and infrastructure strength of the bank

to create lower cost and faster growth. The Service Company Model has the potential to

take the burden of overseeing microfinance operations off the management of the bank and

put it in the hands of MFI managers who are focused on microfinance to introduce

additional products, such as individual loans for SHG graduates, remittances and so on

without disrupting bank operations and provide a more advantageous cost structure for

microfinance. We need to pilot test this.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

23/31

The Road Ahead : -

I recently wrote an article together with Graham Wright called Banking for the Poor and

not Poor Banking. What we wanted to say was that notwithstanding our significantachievements, there are still large sections of the population without access to financial

services. A conservative estimate for example suggests that just20% of low-income peoplehave access to them. Thus, there is an urgent need towiden the scope, scale and outreachof financial services to reach the vast unreachedpopulation.

In this context may I quote from the recent Annual Policy Statement (2005-06) of the

Governor RBI. Drawing attention to the expansion, greater competition and diversification

of ownership of banks leading to enhanced efficiency and systemic resilience in the

banking sector, the Governor has said that notwithstanding this there are legitimate

concerns in regard to the banking practices that tend to exclude rather than attract vastsections of population, in particular pensioners, self-employed and those employed in

unorganised sector. While commercial considerations are no doubt important, the banks

have been bestowed with several privileges, especially of seeking public deposits on a

highly leveraged basis, and consequently they should be obliged to provide banking

services to all segments of the population, on equitable basis. He has clarified that against

this background, the RBI will implement policies to encourage banks which provide

extensive services while disincentivising those which are not responsive to the banking

needs of the community, including the underprivileged. Further, the nature, scope and cost

of services will be monitored to assess whether there is any denial, implicit or explicit, of

basic banking services to the common person. He has advised banks to review their

existing practices to align them with the objective of financial inclusion.

I have come to the end of my presentation. Looking back I find that the key players are

banks as partners in the linkage programme and emerging MFIs. Banks through their rural

branches have played and continue to play an important role in providing financial services

to the poor on a stand-alone basis. Banks need to introspect on the quality and coverage of

these portfolios. Further as key stakeholders in the Bank-SHG linkage programme, they,

together with other partners need to take forward the good work they have been doing.

The SHG Bank Linkage Programme has done well, has made a tremendous contribution toscale and is on a high growth path. However, the programme is confronted with many

challenges and these need to be addressed through appropriately structured policies and

strategies. In so far as MFIs are concerned it is recognized that they hold significant

potential. However, MFIs need to be challenged to make an increasing contribution to

scale consistent with cost, sustainability and efficiency of operations. Given these and

other challenges embedded in the microfinance context, this conference has been

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

24/31

organised so that we can all deliberate on the issues involved and come up with

appropriate recommendations for policy formulation.

We are living through challenging and upbeat times. Yet anyone who has worked in thefield of development knows the highs and lows of working in this sector. Sometimes

when I look at the vast unfinished agenda, the tasks undone, done partly or done poorly,

when I factor in the forces of apathy and status quo, when I see how slowly things move

when in fact they should be moving rapidly I feel a sense of despair - a realisation that in

the end human endeavour is meagre and that the distance between effort and achievement

is indeed long. At times such as these I recollect a message given to us many years ago

when we were emerging from the trauma of the sub-continents partition between India

and Pakistan, when there was great despair for the future of the two nations. In those dark

and troubled days, a poet, Dr Sir Mohammad Iqbal - later the national poet of Pakistan- said

to us :

Which translated into English means that when light fails and you are surrounded by

darkness, do not despair, take heart - for a thousand million stars must die each night just

so that a new dawn can be born tomorrow.

On this note of hope for a better tomorrow and with a sense of sincere appreciation for all

those working in the sector practitioners and policy makers, researchers and regulators

and academicians and activists I take leave and thank you for having given me thisopportunity of sharing my thoughts with you today.

Bank Partnership Model :

This model is an innovative way of financing MFIs. The bank is the lender and the

MFI acts as an agent for handling items of work relating to credit monitoring,

supervision and recovery. In other words, the MFI acts as an agent and takes care

of all relationships with the client, from first contact to final repayment. The model

has the potential to significantly increase the amount of funding that MFIs can

leverage on a relatively small equity base.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

25/31

A sub - variation of this model is where the MFI, as an NBFC, holds the individual loans on

its books for a while before securitizing them and selling them to the bank. Such

refinancing through securitization enables the MFI enlarged funding access. If the MFI

fulfils the true sale criteria, the exposure of the bank is treated as being to the individualborrower and the prudential exposure norms do not then inhibit such funding of MFIs by

commercial banks through the securitization structure.

Banking Correspondents :

The proposal ofbanking correspondents could take this model a step further extending it

to savings. It would allow MFIs to collect savings deposits from the poor on behalf of the

bank. It would use the ability of the MFI to get close to poor clients while relying on the

financial strength of the bank to safeguard the deposits. Currently, RBI regulations do not

allow banks to employ agents for liability - i.e deposit - products. This regulation evolved at

a time when there were genuine fears that fly-by-night agents purporting to act on behalf

of banks in whom the people have confidence could mobilize savings of gullible public and

then vanish with them. It remains to be seen whether the mechanics of such relationships

can be worked out in a way that minimizes the risk of misuse.

Service Company Model :

In this context, the Service Company Model developed by ACCION and used in some of the

Latin American Countries is interesting. The model may hold significant interest for state

owned banks and private banks with large branch networks. Under this model, the bank

forms its own MFI, perhaps as an NBFC, and then works hand in hand with that MFI to

extend loans and other services. On paper, the model is similar to the partnership model:

the MFI originates the loans and the bank books them. But in fact, this model has two very

different and interesting operational features :

(a) The MFI uses the branch network of the bank as its outlets to reach clients. This allows

the client to be reached at lower cost than in the case of a standalone MFI. In case of banks

which have large branch networks, it also allows rapid scale up. In the partnership model,MFIs may contract with many banks in an arms length relationship. In the service company

model, the MFI works specifically for the bank and develops an intensive operational

cooperation between them to their mutual advantage.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

26/31

(b) The Partnership model uses both the financial and infrastructure strength of the bank

to create lower cost and faster growth. The Service Company Model has the potential to

take the burden of overseeing microfinance operations off the management of the bank and

put it in the hands of MFI managers who are focused on microfinance to introduce

additional products, such as individual loans for SHG graduates, remittances and so on

without disrupting bank operations and provide a more advantageous cost structure for

microfinance. We need to pilot test this.

The Road Ahead

I recently wrote an article together with Graham Wright called Banking for the Poor and

not Poor Banking. What we wanted to say was that not with standing our significant

achievements, there are still large sections of the population without access to financial

services. A conservative estimate for example suggests that just 20% of low-income people

have access to them. Thus, there is an urgent need to widen the scope, scale and outreach of

financial services to reach the vast unreached population.

In this context may I quote from the recent Annual Policy Statement (2005-06) of the

Governor RBI. Drawing attention to the expansion, greater competition and diversification

of ownership of banks leading to enhanced efficiency and systemic resilience in the

banking sector, the Governor has said that notwithstanding this there are legitimate

concerns in regard to the banking practices that tend to exclude rather than attract vast

sections of population, in particular pensioners, self-employed and those employed in

unorganised sector. While commercial considerations are no doubt important, the banks

have been bestowed with several privileges, especially of seeking public deposits on a

highly leveraged basis, and consequently they should be obliged to provide banking

services to all segments of the population, on equitable basis. He has clarified that against

this background, the RBI will implement policies to encourage banks which provide

extensive services while disincentivising those which are not responsive to the banking

needs of the community, including the underprivileged. Further, the nature, scope and cost

of services will be monitored to assess whether there is any denial, implicit or explicit, of

basic banking services to the common person. He has advised banks to review their

existing practices to align them with the objective of financial inclusion.

We have come to the end of my presentation. Looking back I find that the key players are

banks as partners in the linkage programme and emerging MFIs. Banks through their rural

branches have played and continue to play an important role in providing financial services

to the poor on a stand-alone basis. Banks need to introspect on the quality and coverage of

these portfolios. Further as key stakeholders in the Bank-SHG linkage programme, they,

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

27/31

together with other partners need to take forward the good work they have been doing.

The SHG Bank Linkage Programme has done well, has made a tremendous contribution to

scale and is on a high growth path. However, the programme is confronted with many

challenges and these need to be addressed through appropriately structured policies and

strategies. In so far as MFIs are concerned it is recognized that they hold significant

potential. However, MFIs need to be challenged to make an increasing contribution to

scale consistent with cost, sustainability and efficiency of operations. Given these and

other challenges embedded in the microfinance context, this conference has been

organised so that we can all deliberate on the issues involved and come up with

appropriate recommendations for policy formulation.

*What is Exciting about Indian Microfinance?

A Task Force on Microfinance recognised in 1999 that microfinance is much more thanmicrocredit, stating: "Provision of thrift, credit and other financial services and products ofvery small amounts to the poor in rural, semi-urban and or urban areas for enabling themto raise their income levels and improve living standards". The Self Help Group promotersemphasise that mobilising savings is the first building block of financial services.

For many years, the national budget and other policy documents have almost equatedmicrofinance with promoting SHG links to the banks. The central bank notification thatlending to MFIs would count towards meeting the priority sector lending targets for Banksoffered the first signs of policy flexibility towards MFIs. One could argue that MFIs are smalland insignificant, so why bother. The larger point is about policy space for innovation and

diversity of approaches to meet large unmet demand. The insurance sector was partiallyopened to private and foreign investments during 2000. Over 20 insurance companies arealready active and experimenting with new products, delivery methodologies and strategicpartnerships.

Microfinance programmes have rapidly expanded in recent years. Some examples are:

y Membership of Sa-Dhan (a leading association) has expanded from 43 to 96Community Development Finance Institutions during 2001-04. During the sameperiod, loans outstanding of these member MFIs have gone up from US$15 millionto US$101 million.

y The CARE CASHE Programme took on the challenge of working with small NGO-MFIs and community owned-managed microfinance organisations. Outreach hasexpanded from 39,000 to around 300,000 women members over 2001-05, Many ofthe 26 CASHE partners and another 136 community organisations these NGO-MFIswork with, represent the next level of emerging MFIs and some of these are alreadydealing with ICICI Bank and ABN Amro.

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

28/31

y In addition to the dominant SHG methodology, the portfolios of Grameen replicatorshave also grown dramatically. The outreach of SHARE Microfin Limited, for instance,grew from 1,875 to 86,905 members between 2000 and 2005 and its loan portfoliohas grown from US$0.47 million to US$40 million.

Since banks face substantial priority sector targets and microfinance is beginning to berecognised as a profitable opportunity (high risk adjusted returns), a variety of partnershipmodels between banks and MFIs have been tested. All varieties of banks - domestic andinternational, national and regional - have become involved, and ICICI Bank has been at theforefront of some of the following innovations:

y Lending wholesale loan funds.y Assessing and buying out microfinance debt (securitisation).y Testing and rolling out specific retail products such as the Kissan (Farmer) Credit

Card.y Engaging microfinance institutions as agents, which are paid for loan origination

and recovery, with loans being held on the books of banks.y Equity investments into newly emerging MFIs.y Banks and NGOs jointly promoting MFIs.

The 2005 national budget has further strengthened this policy perspective and the FinanceMinister Mr P. Chidambram announced "Government intends to promote MFIs in a big way.The way forward, I believe, is to identify MFIs, classify and rate such institutions, andempower them to intermediate between the lending banks and the beneficiaries."

What is beginning to happen in microfinance can be seen from the perspective of what hashappened to phones in India. With the right enabling environment, and intense competition

amongst private sector players, mobile phones in India expanded by 160% during just oneyear 2003-04 (from 13 to 33 million). Mobile tariffs fell by 74% during the same period.While this is heady progress, there is a less heralded but even more powerful nationwidesuccess on access. In the late eighties, the phone infrastructure was the monopoly of publicsector institutions. Phones were difficult to get and even more difficult to use for thoselacking ownership. Realisation that users need not own a phone to access one led toprivatisation of the last mile - where a phone user could interface with a private sectorprovider using the public sector telecom infrastructure. Even with this policy change, todaythere are 2.5 million entrepreneurs selling local, national and international phone servicesthrough the length and breadth of India. Many of these are now graduating to sell internetservices and could potentially be banking agents - that is the evolving story.

Savings services are needed by many more customers and as frequently as access to phoneservices. Many poor households value access to savings services and find new providersand arrangements, despite hearing of unreliable savings collectors or even occasionallyfalling prey to such arrangements. Many customers are rich, literate and lucky to havebanks working for them. But many others lack access to safe, secure and accessible savingsservices for the short, medium and long terms. In the past, many banks sent collectors togather these savings but problems with monitoring, inability to tackle misappropriation

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

29/31

and the rising aspiration of collectors to become permanent staff of public sector bankskilled a useful service. The central bank has strictly forbidden commercial banks from usingagents in collection of savings services. This is unfortunate as:

y Effective microfinance delivery is about managing transaction costs for providersand customers.

y A combination of agents and technology can play a powerful role in rightly aligningincentives for the collector and customers, while keeping transaction costsmanageable for everyone.

y The banks can only open so many branches, and fixed and operating costs are high,apart from approvals still needed from the central bank to open new branches orclose existing ones. The appointment of agents can keep costs manageable and offergreater flexibility to Banks.

y Banking service may not be able to defy the commercial logic pursued by most othersectors where a variety of retailers provide services to customers, while companiesfocus on customer needs, product design, quality control, branding, logistics and

distribution.

Fortunately, the 2005 Budget opened a small window in this area and the central bankannual policy recently confirmed discussions on this: "As a follow-up to the Budgetproposals, modalities for allowing banks to adopt the agency model by using theinfrastructure of civil society organisations, rural kiosks and village knowledge centres forproviding credit support to rural and farm sectors and appointment of micro-financeinstitutions (MFIs) as banking correspondents are being worked out." But readers maynote that between the budget and the annual policy statement, "credit" has again crept inas the key perceived need.

*Challenges Remain

A World Bank study assessing access to financial institutions found that amongst ruralhouseholds in Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, 59% lack access to deposit account and78% lack access to credit. Considering that the majority of the 360 million poor households(urban and rural) lack access to formal financial services, the numbers of customers to bereached, and the variety and quantum of services to be provided are really large. VijayMahajan, Managing Director of BASICS, estimated that 90 million farm holdings, 30 millionnon-agricultural enterprises and 50 million landless households in India collectively need

approx US$30 billion credit annually. This is about 5% of India's GDP and does not seem anunreasonable estimate.

A tiny segment of this US$30 billion potential market has been reached so far and this isunlikely to be addressed by MFIs and NGOs alone. Reaching this market requires seriouscapital, technology and human resources. However, 80% of the financial sector is stillcontrolled by public sector institutions. Competition, consolidation and convergence are allbeing discussed to improve efficiency and outreach but significant opposition remains; for

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

30/31

example, the All India Bank Employees Association has threatened to strike if theGovernment proceeds with its policy of reducing its capital in public sector banks, mergingpublic sector banks or even enhancing Foreign Direct Investments in Indian private banks.

Many speakers at the Microfinance India conference talked about the significant and

growing gap between surging growth in South India, which contrasts with the stagnation inEastern, Central and North Eastern India. Microfinance on its own is unlikely to be able toaddress formidable challenges of underdevelopment, poor infrastructure and governance.

The Self Help Group movement is beginning to focus on issues of quality and there weresome interesting discussions on embedding social performance monitoring as a part of theregular management information systems.

At the time of the conference, a leading and responsible MFI was being investigated by theauthorities for charging "high" rates of interest. Per unit transaction costs of small loans arehigh but many opinion leaders still persist with the notion poor people cannot be charged

rates that are higher than commercial bank rates. The reality of the high transaction costsof serving small customers, their continuing dependence on the informal sector, the factthat most bankers shy away from retailing to this market as a business opportunity, andthe poor quality of services currently provided does not figure prominently in thisdiscourse. While the central bank has deregulated most interest rates, including lending toand by MFIs, interest rates restrictions on commercial bank for retail loans below US$5,000(all microfinance and beyond) remain and caps on deposit rates also discourage sharingtransaction costs with customers. But most conference participants accepted theimperatives to build sustainable institutions.

There is still lot of policy focus on what activities are and are not allowed and not enough

operational freedom as yet for banks and financial institutions to design and deliverprogrammes, and be responsible for their actions. Prescriptions and detailed circularsoften limit organisational innovation and market segmentation. As Nachiket Mor of ICICIBank said at the conference, if the right indicators are monitored and operational freedomand incentives are clear, both public and private banks have the capacity to rapidly addressthe remaining challenges.

*Closing Remarks

In my view, savings service is the neglected daughter of the family of financial services. Iuse this metaphor because of the sustained discrimination against and frequent disregardfor savings services, despite their productive and reproductive role in financial services[5].This is evident from different nomenclature used at both the international (UNInternational Year of Microcredit, MicroCredit summit) and national levels (Priority SectorLending; Annual Credit Policy; Credit/ deposit ratio). Savings services can be a useful entrypoint for the unbanked to build up a history with the formal financial institutions beforecustomers are entitled to other financial services. With the greater spotlight on knowing

-

8/8/2019 Term Paper Project1

31/31

the customer and the fact that poor households do not have a salary slip, utility bills, clearland titles or unique identity papers, a regular savings record could be the first buildingblock to membership of the formal financial sector. What is more, with savings services,poor customers need to trust the financial institution and not the other way round.

Microfinance is not yet at the centre stage of the Indian financial sector. The knowledge,capital and technology to address these challenges however now exist in India, althoughthey are not yet fully aligned. With a more enabling environment and surge in economicgrowth, the next few years promise to be exciting for the delivery of financial services topoor people in India.

I would like to congratulate CARE, as the lead organisers, for successfully hosting thisglobal cross learning event. Unusually, the event ended with a statement of someobjectively verifiable indicators (such as expansion of urban microfinance, increasedconference participation by public sector banks and redressal of North South divide) onwhich the sector should track progress in a years' time.

*Conclusion

A main conclusion of this paper is that microfinance can contribute to solving the problemof inadequate housing and urban services as an integral part of poverty alleviationprogrammes. The challenge lies in finding the level of flexibility in the credit instrumentthat could make it match the multiple credit requirements of the low income borrowerswithout imposing unbearably high cost of monitoring its end-use upon the lenders. Apromising solution is to provide multi-purpose loans or composite credit for incomegeneration, housing improvement and consumption support. Consumption loan is found tobe especially important during the gestation period between commencing a new economic

activity and deriving positive income. Careful research on demand for financing andsavings behaviour of the potential borrowers and their participation in determining themix of multi-purpose loans are essential in making the concept work (tall 1996).

Eventually it would be ideal to enhance the creditworthiness of the poor and to make themmore "bankable" to financial institutions and enable them to qualify for long-term creditfrom the formal sector. Microfinance institutions have a lot to contribute to this by buildingfinancial discipline and educating borrowers about repayment requirements.