Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

-

Upload

ramona-bozianu -

Category

Documents

-

view

227 -

download

0

Transcript of Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

1/28

10.177/1077727X03258701 ARTICLEFAMILYANDCONSUMERSCIENCESRESEARCHJOURNALKim etal. /TEENS’ MALLSHOPPINGMOTIVATIONS

Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations:Functions of Loneliness and Media Usage

Youn-Kyung KimUniversity of Tennessee

Eun Young KimChungnam National University

Jikyeong KangThe University of Manchester

Theshoppingmall canserveas a venue through which teens canfulfill their needs by socializingwith friends, enjoying entertainment, or simply visiting thesite. This study testedwhether andhowmall shoppingmotivations were related to lonelinessand media usage amongteen consum-ers. Data were collected via a mall intercept survey from 531 teens in four large shoppingmallsin theUnitedStates.Findingsindicatedthat mall shoppingmotivationsconsistedof fivedimen-sions: service motivation, economic motivation, diversion motivation, eating-out motivation,andsocialmotivation.Results suggest directions formarketersand educatorsto follow in estab-lishing positive programs to provide social support for teens.

Keywords: teens; mall shopping motivations; loneliness; media usage.

Teens need to gain special attention from marketers and scholars inthe area of family and consumer sciences because of their unique

demographic and psychological characteristics. Teens between theages of 12 and 19, born in the 1980s to parents of baby boomers orolder generation Xers, are growing rapidly in number and consump-tionpower. Thispopulation segmentis increasing in number at twicethe rate of the overall U.S. population (Goff, 1999). Although teensmake far less money than adults, they have relatively more dispos-able income (Zollo, 1995), which is earned from parental allowancesand part-time jobs. Furthermore, the decrease in family size becauseof sociodemographic changes (e.g., delayed marriage, higher divorce

140

Authors’Note: Thisproject wasfundedby theInternational Council of ShoppingCen-

ters Educational Foundation.Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, Vol. 32, No. 2, December 2003 140-167© 2003 American Association of Family and Consumer Sciences

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

2/28

rate) allows parents to spend more money on their children(Anderson, 2000).Traditionally, mallsattractedconsumers through theavailabilityof

a wide assortment of stores and merchandise in a single location.Over the years, the mall has grown larger by increasing its range of social andentertainmentproviders andactivities (e.g., special events,food courts, cinemas, and video arcades). By broadening the mix of tenants and activities, the mall has transcended its role as an eco-nomic entity to position itself as a center for entertainment and cul-turalevents(Bloch,Ridgway,&Dawson,1994;Graham,1988).Infact,going to the mall has become a majorelementin the lifestyles of mod-ern U.S. consumers and has been labeled as “a culturally ingrainedphenomenon” (Cuneo, 2000, p. 38). Many consumers consider the

mall “a premier habitat” and spend a relatively long time on-site(Bloch et al., 1994). Despite all these changes, consumers now go tomalls less frequently and instead seek convenient shopping throughcatalogs andthe Internet because theyhave more timepressures thanin the past. However, teens, who have more free time for shoppingthan other population groups (i.e., baby boomers and generationXers), are shopping at malls in greater numbers today (Kang, Kim, &Tuan, 1996; Richardson, 1993).

Althoughadolescencecanpotentiallybe a timeof self-identificationand new discoveries that lead to new adultroles, this time period alsocan bring about stress in the form of depression, loneliness, and otherpsychological difficulties (S. T. Hauser & Bowlds, 1990; McCord,1990). These psychological stresses may be compounded by the factthat most teens live in nontraditional families with two working par-ents, stepparents, or a single parent and/or may have unsatisfactoryrelationships with their friends. During this stage of their lifetime,teens experience decreases in family influences and increases in peerand media influences (Arnett, 1995).

According to Wilson and MacGillivray (1998), most teens reveal astrongpsychosocialneedtobelongtoandbeapprovedbyotherswhoare significant to them. As a result, they conform to peers in lifestylepreferences, such as leisure-time activities, dress, and music (Berndt &Das,1987; Huston & Alvarez, 1990). Teens consider shoppingmore of an experience than a routine (Zollo, 1995). They shop to becomemoreindependent, socialize with friends, or express themselves (Omelia,

1998). In fact, many retail settings (e.g., record store, video arcade)provide a meeting place for teens who desire to be with their peergroup or reference group. Thus, the venue through which teens can

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 141

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

3/28

fulfill theirunique needs seemsto be a shopping mall where they cansocialize with friends, enjoy entertainment, or solve their lonelinessor other psychological stresses (Bloch et al., 1994; Omelia, 1998).

Given the role the mall plays in meeting teens’ multiple needs, itseemscriticalthateducatorsandmarketersunderstandwhyandhowteens exhibit certain consumption behavior in malls. As the first step,this study examined how teens vary in the motivations that bringthem to the mall. Next, it assessed how teens’ various mall shoppingmotivations are associated with their level of loneliness and mediausage, which entailed using the structural model to investigate thecausal relationshipsamong these three variables.Thisstudy providesuseful information for educators to incorporate teens’ mall shoppingmotivations into their educational programs. Retailers who develop

strategies based on teens’ special needs for shopping will create astrong relationship with this younger group providing long-termresults.

RESEARCH BACKGROUND

Mall Shopping Motivations

Within a consumer behavior context, motivation refers to the drive,urge, wish, or desire that leads to a goal-oriented behavior (Mowen,1995). Mall shopping motivation is simply that aspect of motivationthat is attributed to shopping in a mall setting. Inreviewing the litera-

ture, motivations forshopping in malls range from utilitarianmotiva-tion to hedonic or experiential motivation (Bellenger & Korgaonkar,1980; Bloch et al., 1994; Kang et al., 1996; Roy, 1994).

Utilitarian motivation involves satisfying functional needs, suchas convenient shopping; procuring goods, services, or specific infor-mation;and reducing thecosts (i.e., money, time, and effort) that mayhave to be expended in transportation, finding specific products orservices, and waiting in check-out lines (Kim & Kang, 1997). Hedonicor experientialmotivation involves satisfyingemotional or expressiveneeds, such as fun, relaxation, and gratification (Bloch, Ridgway, &Nelson, 1991; Roy, 1994). These hedonic satisfactions may be derivedfrom ambience, entertainment, browsing,and social experiences out-side the home (e.g., meeting friends, watching people).

More specific mall shopping motivation categories were found inthe literature. For instance, Bellenger, Robertson, and Greenberg

142 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

4/28

(1977) identifiedtwomall shoppinggroupsbased on shopping orien-tations. Recreational shoppers enjoy shopping as a leisure-time activ-ity. Convenienceor economic shoppersapproachmall shopping froma time- or money-saving point of view. In Roy’s (1994) study, mallshopping motivation consisted of three dimensions: functional eco-nomic motivation, deal proneness, and recreational shopping moti-vation. They found that deal-proneness motivation was negativelycorrelated with visit frequency, which implies that price-sensitiveconsumers might wait for special sales before mall visits and thusmay become relatively infrequent patrons of shopping malls. On theother hand, the degree of recreational shopping motivationwas posi-tively correlated with visit frequency, suggesting that people whowant to satisfy the needs for affiliation, power, and stimulation visit

malls relatively often.Bloch et al. (1994) identified distinct patterns of the mall habitat.

The six patterns captured were

• mall enthusiasts, engaging in a wide range of behaviors that include ahigh level of purchasing, enjoymentof themall aesthetics (e.g.,physicaldesign, appearance), and experiential consumption

• escape, representing sensorystimulation,a relief from boredom, and anescape from routine

• exploration, tapping consumers’ desires for variety or novelty andenjoyment of exploring new products or stores while in the mall

• flow, reflecting a pleasurable absorption that is associated with losingtrack of time

• knowledge or epistemic, referring to obtaining information about new

stores and new products• social affiliation, addressing the enjoyment of communicating and

socializing with others

Kang et al. (1996) identified six motivation factors of mall shop-pers: aesthetic ambience, economic incentives, diversion/browsing,social experience, convenient service availability, and consumptionof meal/snack. These researchers found that mall shopping motiva-tions vary significantly according to age group. The teen consumergroup, compared to the other age groups (ages 20 to 49 and 50 andolder), had stronger diversion/browsing and social experienceshopping motivations.

Earlyresearchintoteensconcentratedonunderstandingtheroleof

consumer socialization agents, such as family, peer, andmedia in con-sumer behavior (Moore & Schultz, 1983; Moschis & Churchill, 1979;

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 143

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

5/28

Moschis & Moore, 1979). Subsequent research combined these vari-ables with shopping orientations (Shim & Gehrt, 1996), clothing or brand choice (Taylor & Cosenza, 2002; Wilson & MacGillivray, 1998),and shopping experience as entertainment (Baker & Haytko, 2000).Nevertheless, related literature reveals that except for Kang et al.(1996), a lack of empirical research is focused on teen consumer behavior as it relates to mall shopping motivation. Limited studiesreported that, compared to adult consumers, teen consumers aremore likely to be motivated to shop for the hedonic needs of diver-sion, enjoying the crowds, and entertainment, such as enjoying thefood court or interior of malls, than for utilitarian needs (Cebrzynski,1999; “The Survey Says: Teen-agers Want to Shop ’til They Drop”,1994). Lack of research focus on this population group, combined

with their number and purchasing power, underscores the need tounderstand how teens’ mall shopping motivation relates to theirneeds in retail environments.

Loneliness and Mall Shopping Motivations

Loneliness has been documented as a condition that affects manylarge segments of U.S. society. In fact, it has been acknowledged thatloneliness is a relatively common experience among teens. This may be a result of their trying to define their role in the family and searchfor greater independence (Kostelecky & Lempers, 1998; Marcoen &Goossens, 1993; Perlman, 1988).

Although there has been some debate about the definition and

measurement of loneliness, a commonly held definition of lonelinessincludes underlying dimensions, such as an unpleasant experience,deficiencies in a person’s social relationships,anda subjectiveexperi-ence with social isolation (Forman & Sriram, 1991; Russell, Peplau, &Cutrona, 1980). The Russell et al. (1980) Revised UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale, one of the best knownscales to measure loneliness, conveys these three dimensions. Con-trastedwith adults, teens’ loneliness might be induced from deficientsocial relationships with their peers or friends, such as having fewerfriends or being isolated from peers (Lewis, Dyer, & Moran, 1995;Moschis, 1987). Other deficient social relationships may be derivedfrom a lack of interpersonal communication among family members,parents’ divorce, a recent death or serious illness in the family or of aclose friend, or a failed romance (Kostelecky & Lempers,1998; Weiss,1974). Loneliness also can be a subjective experience in the sense that

144 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

6/28

individuals who do not have friends may not feel lonely or that thoseindividualswhohave friends canbe lonely. Thesubjectiveexperienceof loneliness is supported by McWhirter’s (1997) study that throughfactor analysis of the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale, two distincttypes of loneliness were revealed: intimate loneliness and socialloneliness.

As a strategy to cope with and solve their feelings of loneliness,teens make an effort to find more satisfying friendships and socialcontacts.However, these effortsmayresult in sensually oriented solu-tions, such as drinking or taking drugs, or diversionary activities,such as keeping busy, working, or reading. Shopping malls can func-tionasapositivevenueforteenstoalleviatetheirlonelinessviamulti-ple means such as socializing, browsing, entertaining, or simply buy-

ingwhat they want. Bloch et al. (1991) notedthat“shoppingmalls arealso hospitable to people who are alone” by providingsocial contacts(p. 446).

Literature has provided much evidence to support the role of aretail settingas an outlet forsocial stimulationandsupportforcertainindividuals. Stone (1954) identified four types of women shoppers:economic shoppers, personalizing shoppers, ethical shoppers, andapathetic shoppers. Among these four groups, personalizing shop-pers form strongpersonal attachments to store employees as a substi-tuteforsocial contact. Accordingto Tauber (1972), shopping canmeetsocial motives (e.g., socialexperiences outsidethehome, communica-tion with others having a similar interest, status and authority, andthe pleasure of bargaining) as well as personal motives (e.g., diver-sion, browsing, self-gratification, learning about new trends). Tauberargued that an individual may visit a retailer in search of diversionorsocial contact when he or she feels bored, lonely, or depressed.

Rubenstein andShaver (1980) posed the research question, “Whenyou feel lonely, what do you usually do about it?” Results yieldedfour factors including going shopping, social contact (e.g., calling orvisitinga family andfriend), sadpassivity (e.g., doing nothing, sleep-ing, thinking), and active solitude (e.g., writing, exercising, workingon a hobby). Finding two separate factors of going shopping andsocial contact suggests that going to a store or mall may represent ameans to fill a social void apart from the moreintimate socialcontactsthat may or may not be available. Forman and Sriram (1991) sug-

gested a negative attitude toward depersonalized retailing (e.g., self-service stores) existed among lonely consumers. It is contended that

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 145

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

7/28

retailing establishments provide lonely individuals an outlet forsocial participation,whichalleviatesfeelings of intimate isolation. Onthe other hand, individuals with fewer social interactions and casualfriendships are less likely to cope with their negative feeling, such associal loneliness (McWhirter, 1997). This supports Eronen andNurmi’s (2001) argument for the relationship between social avoid-ance and loneliness. In the context of shopping, Hirschmann (1984)found that social isolation was negatively related to experientialshopping, discussing that lonely consumers are less likely to engagein shopping for sensory or novelty needs.

Based on reviewing the literature, we propose the followinghypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a: Teens’ intimate loneliness will increase their mall shoppingmotivations.

Hypothesis 1b: Teens’ social loneliness will decrease their mall shoppingmotivations.

Loneliness and Media Usage

Adolescence is a time when the presence and power of familydiminishes and new adult roles, such as marriage and long-termemployment, typically have not yet occurred. Accordingly, this com-plex transitional stage may produce teens more inclined to make useof media in their socialization than are younger or older consumers(Arnett, 1995). In addition, many teens go home to parentless houses

andarealoneafterschool,whichinducesthemtospendmoretimeonmedia.Media provides teens with norms, values, and behaviors about

their age group and groups they aspire to join, as well as providingteens with a resource for fulfilling various needs (Ferle, Edwards, &Lee, 2000). Among these needs are relaxation, coping, killing time,youth-culture identification, and entertainment (Arnett, 1995; Roe,1995).

According to Moore and Schultz (1983), listening to music was thecoping strategy most commonly used by teens when they are angry,anxious, or unhappy. Teens reported watching television was a delib-erate coping strategy to dispel negative affect (Kurdek, 1987) or todivert themselves from personal concerns with passive, stressful

emotions that had accumulated during the day (Arnett, Larson, &Offer, 1995). Similarly, reading printed media (e.g., magazine,

146 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

8/28

newspaper) can be anotheractivity that teens may use to reduce theirlevel of loneliness. Although no study examined teens’ loneliness inrelationtomediausage,itcanbespeculatedthatteenswhofeellonelyengage in heavier use of media. Thus, the following hypothesis isposed:

Hypothesis 2: Teens’ intimate loneliness and social loneliness will increasetheir media usage.

Media Usage and Mall Shopping Motivations

The pervasive presence of the media in industrialized countriesprovides teens with vast exposure to a wide range of products, ser-

vices, and processes that would not be available through the familyandfriends. In addition, as teens seekto distance themselves from theconstraints of family and go beyond the influence of friends, themedia can act as agents to expand their horizons of consumption-related knowledge or preferences (Wilson & MacGillivray, 1998).

McGrath (1998) reported that approximately 76% of teenagerswatch television at home, and one half of them watch television withfamily whileeating dinner; 24% of teens listento the radio. Ferleet al.(2000) discovered that, among media types, the greatest number of media usage hours among teens was allocated to listening to theradio. Although teens’ magazine and newspaper readership consti-tutes a smaller amount of the average teen’s time compared to televi-sion and radio, it should not be ignored because of the media’s reach.

For example, 82% of Seventeen magazine’s female readers are in theage bracket of 12 to 17 years (Ebenkamp, 2000). Nearly 70% of teensread a daily newspaper at least once a week (Freeman, 1999).

Several consumer studies examined the influence of the media onthe development of consumer decisions and socialization (Shim,1996), shopping orientation (Moschis, 1976), product evaluations(Churchill & Moschis, 1979; Moschis & Moore, 1979), and sociallydesirable consumer behaviors(Moschis & Moore, 1982).More specifi-cally, Moschis (1976) associated media usage with different shoppingorientations (i.e., special shopper, brand-loyal shopper, store-loyalshopper, problem-solving shopper, psychosocializing shopper, andname-conscious shopper). For example, problem-solving shoppersand psychosocializingshoppers spent more hours viewing televisionthan other types of shoppers. Special shoppers read more home

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 147

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

9/28

magazines, whereas the name-conscious shoppers were more likelyto read fashion, news, and business magazines.Mediatypealsowasassociatedwiththecreationofpositiveorneg-

ative consumer orientations. Television watching was related toundesirable consumer orientations, such as the increased desire forcompulsive consumption (Lee, Lennon, & Rudd, 2000), conspicuousconsumption(Moschis&Moore,1982),andadecreasedabilitytopro-cess information regarding consumption (Ward, Wackman, &Wartella, 1977). On the other hand, newspaper reading was linked todesirable consumer orientations because it was correlated positivelywith thedevelopmentof rational consumer orientations, such as con-sumer knowledgeor financialmanagement (Moore& Moschis,1981).

Information about teens’ media usage in relation to shopping ori-

entations or motivations is limited. Among the few studies, Shim(1996) investigated adolescents’ consumer decision-making stylesfrom the consumer socialization perspective. Teens’ receptiveness totelevisioncommercials was positivelyrelated to the social/conspicuousorientations, such as buying expensive, well-known brands, seekingexcitement from novelties and fashion, and shopping for recreationand entertainment. On the other hand, increased reading of printedmedia (i.e., newspaper) appeared to point adolescents toward moreutilitarian orientations including high quality, price consciousness,and value for money (Shim & Gehrt, 1996).

Additionalstudiesfocusedonteens’mediausageandhowitinflu-enced their consumptiondecisions. Accordingto Moschis andMoore(1979), the amount of newspaper readingwashighly related to brandpreferences among teens. This suggested that teens may use brandnameasanefficientshoppingtoolinevaluatingvariousproductsthathave different levels of price, performance, andwarranty. Wilson andMacGillivray (1998) also discovered that television and magazinesprovided a substantial influence on adolescent clothing choice. In theFerle et al. (2000) study, television and radio were found to fulfillentertainmentandleisure needs most often,whereas magazinescom-monly were used for shopping and health-related information.

Conclusively, the literature supports the argument that teens’media usage can influence why teens visit or shop at the mall. Thus,the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 3: Teens’ media usage will increase their mall shoppingmotivations.

148 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

10/28

METHOD

Measures

Measures consisted of three main constructs: shopping motiva-tions,mediausage,andloneliness.Revisionoftheinitiallydevelopedquestionnaire was based on a pretest of a small convenience sample(n = 20). Inputs from the respondents ledto several minor revisions inthe final questionnaire’s wording, instructions, or formats.

Shopping motivations.Initially,alistof16itemsofshoppingmotiva-tions was drawn from the literature encompassing utilitarian aspectsas well as hedonic aspects of mall shopping (Bellenger et al., 1977;

Bloch et al.,1994; Kang et al.,1996; Roy, 1994; Tauber, 1972). Examplesof shopping motivation items included “to hunt for a real bargain”and “to simply enjoy the crowds.” These shopping motivation itemswere measured on a 7-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 =strongly agree).

Media usage.Fourmediausages(e.g.,watchingtelevision,listeningto radio, readingnewspaper, and reading magazine) were measured.Respondents were asked howoften they engage in these activities ona 7-point rating scale (1 = never, 7 = always).

Loneliness.ThemeasureoflonelinesswasderivedfromtheRevisedUCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1980), a scale shown to have

high internal consistency. The scale consisted of 11 items, whichassessed an individual’s self-perceived loneliness. The items werecomposed of intimate loneliness such as “I feel isolated from others”and “No one really knows me well” and social loneliness such as“Therearepeoplewhoreallyunderstandme”and“TherearepeopleIcan talk to.” The items of social loneliness were reverse coded beforescoring to reflect the concept of loneliness.

Sampling and Data Collection

The sample in this study focused on teen consumers aged 12 to 19.After obtaining human participant approval from the InternalReview Board, data were collected via mall intercept survey in fourlarge shopping malls located in New York, Houston, Dallas, and LosAngeles. To ensure adequate sample diversity, data collection was

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 149

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

11/28

implementedat a variety of times and days of the week. Interviewersintercepted shoppers as they were exiting the malls to ask for theirparticipation in thesurvey. Prospective respondents were offered a $2cash payment to secure participation. They took an average of 20minutes to complete a four-page, self-administered questionnaire. Atotal of 531 teens completed the survey.

The group of respondents in this study consisted of slightly moreyoung women (52.3%) than young men (47.7%). Most respondentslived with family (82.3%). The largest number of respondents wasunemployed (56.4%), followed by those employedpart-time (28.3%).Three ethnic groups were included in the sample: White (31.4%),Black (34.7%), and Hispanic (31.3%).

Data Analysis

For identifying underlying dimensions of shopping motivation,we preliminarily conducted an exploratory factor analysis. Then aconfirmatory factor analysis using LISREL 8 (Jöreskog & Sörbom,1993) verified shopping motivation factors derived from the explor-atory factor analysis. Loneliness also was factor analyzed using prin-cipal components analysis with varimaxrotationto determine under-lying constructs in the structural model. Finally, the measurementmodel and structural model using correlation matrix with maximumlikelihood (ML) were estimated simultaneously via LISREL 8(Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993). Overall fit of the model was assessed byvarious statistic indexes: chi-square (χ2), goodness of fit index (GFI),

adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Shopping Motivation Factors

An exploratory factor analysis using principal components factoranalysis with varimax rotation was employed to identify underlyingdimensions of 16 shopping motivation items. Three items were elimi-nated due to loadings less than 0.50. The remaining 13 items resultedin five factors with eigenvalues of 1.0 or higher, accounting for 64.4%

of the total variance in shopping motivations.

150 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

12/28

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to verify the factorstructure of shopping motivationderived from the exploratory factoranalysis. Theresultrevealed thatχ2 valuewas89.47with54degreesof freedom,whichwassignificant( p = .0017). This result was most likelycausedbythesensitivityofthe χ2 ratiotestoverlyaffectedbythelargesample size (N = 531) even though the model may explain the datawell (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995).Therefore, alternative fit indexes such as GFI, AGFI, and RMSEAwereusedtoevaluatethegoodnessofthemodelfit.TheGFI,orAGFI,which is independent of the sample size and relatively robust againstdeparture from normality, was 0.97 and 0.96, respectively. TheRMSEAis 0.036, indicatinga relatively small residual. Thus, theover-all model fit indexes are within the acceptable range. As illustrated in

Table 1, the factor loadings of those indicators ranged from 0.63 to0.80, and Cronbach’s alphas of the factors ranged from .62 to .76.Therefore, it was deemed that the factor structure of each shoppingmotivationwasvalidandcouldbeusedtotestthestructuralmodel.

Thefirst factor, service motivation, consisted of three items: to visitmedical/dental/vision care office, to usebanking service, andto lookat the interior design of malls. It is notable that the interior design of malls was loaded in the same factor with service providers. Accord-ingtoKimandKang(1997),utilitarianmotivationisextendedtocom- bine assorted tasks in achieving the greatest efficiency and time sav-ing. In this view, although teens visit service providers, enjoyment of theinteriorsofthemallmaycontributetotheirperceptionoftimeeffi-ciency. The mean of this factor was lowest ( M = 2.57) of the five shop-ping motivations, which supports the Kang et al. (1996) finding thatyoungerconsumersarelesslikelytovisitserviceproviders(e.g.,bankand clinics) in malls than are adult consumers.

The second factor, economic motivation, included three purchase-related items: to find a good price, to hunt for a real bargain, and tocomparison shop to find the best for one's money. The mean of eco-nomic motivationwashighest ( M = 5.09) of all shopping motivations,suggesting that teen consumers in this study were sensitive to price.This finding may have resulted from respondents’ employment sta-tus (56.4% unemployed, 28.3% employed part-time). Contrary toBarbin, Darden, and Griffin’s (1994) contention that consumers’ bar-gain (e.g., price discount) perceptions are related to hedonic value

and utilitarian value, a bargain was perceived as an economic aspectto stimulate teen consumers to go shopping.

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 151

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

13/28

The third factor, diversion motivation, contained three items char-acterizedbynonpurchaseshoppingactivities:justsothatIcangetoutof the house,when I ambored,and just tobrowse.Thisfactor receivedthe second highest shopping motivation mean score ( M = 4.79). Theimportance of diversion as a shopping motivation is consistent withprevious findings concerning why people shop in general (Blochet al., 1994; Kang et al., 1996; Tauber, 1972).

The fourth factor, eating-out motivation, included such motiva-tionsastogetasnackandtohaveamealatthefoodcourtandresulted

152 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

TABLE 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Shopping Motivation

Factor

Factor Items Loading ( ij ) t Value Reliability M ( SD )

Service motivation 0.73 2.57

to visit medical/dental/vision

care offices 0.75 14.51 2.51 (1.99)

to use banking services 0.72 15.06 2.61 (1.88)

to look at the interior design

of malls 0.71 13.56 2.70 (1.87)

Economic motivation 0.76 5.09

to find good prices 0.80 17.26 5.14 (1.77)

to hunt for a real bargain 0.67 14.47 5.20 (1.88)

to comparison shop to find

the best for my money 0.68 14.63 4.93 (1.77)

Diversion motivation 0.71 4.79 just so that I can get out of

the house 0.69 14.15 4.90 (1.96)

when I’m bored 0.69 14.10 4.64 (1.97)

just to browse 0.63 12.94 4.82 (1.84)

Eating-out motivation 0.66 3.44

when I want to get a snack 0.76 14.51 3.18 (1.96)

to have a meal at the food court 0.65 12.96 3.70 (1.86)

Social motivation 0.62 3.65

to watch people 0.71 12.08 3.60 (2.17)

to simply enjoy the crowds 0.63 11.27 3.70 (2.07)

Goodness of Fit Statistics

χ2

= 89.47 (df = 54,

p = .0017)

GFI = 0.97

AGFI = 0.96

RMSEA = 0.036

NOTE:GFI= goodnessof fitindex;AGFI= adjustedgoodnessof fitindex;RMSEA= rootmean square error of approximation.

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

14/28

in a moderate mean score ( M = 3.44). It is possible that, to many teens,eating is not their primary purpose for visiting the mall, but it is anintegral part of their visits, whether they are alone or with friends.

The fifth factor, social motivation, contained two items: to watchpeople and to enjoy the crowd. This factor represents that teens go tomalls for social experiences, such as meeting friends and watchingpeople. A moderate mean score also resulted for social motivation( M = 3.65), indicating that teens may enjoy social stimulation or asense of belongingness as a secondary purpose of the mall visit.

Measurement and Structural Models

For testing hypotheses, an analysis with simultaneous estimation

of structural and measurement models was performed by usingLISREL8. The structural model tested causative relationships amonglatent variables (i.e., loneliness, media usage, and shopping motiva-tions). In the structural model, there are two exogenous variables—intimate loneliness (ξ1) and social loneliness (ξ2)—and seven endoge-nous variables—media usage (η1 = audiovisual media, η2 = printedmedia) and shopping motivations (η3 = service motivation, η4 = eco-nomic motivation,η5 = diversion motivation, η6 = eating-out motiva-tion, η7 = social motivation). The measurement model assessed howthose latent variables are measured in terms of observed indicatorsand described the validity and reliability of the measurement. It con-sisted of observed exogenous indicators (x variables) for lonelinessand observed endogenous indicators (y variables) for media usage

and shopping motivations (see Table 2).

Measurementmodel.Toassessthemeasurementmodel,allobservedindicators were set free by standardizing all exogenous and endoge-nous latent variables becausethe magnitude of coefficient matrix (β’sor γ ’s) for latent variables depends on one observed indicator arbi-trarily selected as a referent for latent variables (Jöreskog & Sörbom,1989). The estimated measurement model presented in Table 2 con-sisted of 6 observed x variables for two loneliness factors, 4 observedyvariablesformediausage,and13observedyvariablesforfiveshop-pingmotivationfactors. Overall, thecoefficients of factor loading (λij)on latent constructs ranged from 0.54 to 0.88 ( p < .001). Reliabilities of latent variables ranged from 0.62 to 0.87. Therefore, the measurementmodel was confirmed to be valid and reliable.

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 153

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

15/28

1 5 4 TABLE 2: The Measurement Model Result

Standardized

Latent Variables and Observed Indicators Coefficients ( ij ) t Value Reliabil

Loneliness

Intimate loneliness (ξ1) 0.80

X1: I feel isolated from others 0.82 19.88

X2: I am unhappy being so withdrawn 0.77 18.34

X3: I feel left out 0.68 15.95

Social loneliness (ξ2) 0.87

X4: there are people I can turn toa

0.88 23.65

X5: there are people I can talk toa

0.82 21.67

X6: there are people who really understand mea

0.77 19.94

Media usage

Audiovisual media (η1) 0.85Y1: television 0.85 20.88

Y2: radio 0.86 21.00

Printed media (η2) 0.81Y3: magazine 0.83 19.42

Y4: newspaper 0.82 14.70

Mall shopping motivation

Service motivation (η3) 0.73

Y5: to visit medical/dental/vision care office(s) 0.68 14.70

Y6: to use banking services 0.77 16.44

Y7: to look at the interior design of malls 0.63 13.65

Economic motivation (η4) 0.76

Y8: to find good prices 0.83 17.78

Y9: to hunt for a real bargain 0.65 14.33

Y10: to comparison-shop to find the best for my money 0.67 14.70

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

16/28

1 5 5

Diversion motivation (η5) 0.71Y11: just so that I can get out of the house 0.69 14.15

Y12: when I am bored 0.70 14.34

Y13: just to browse 0.63 13.14

Eating-out motivation (η6) 0.66

Y14: when I want to get a snack 0.75 10.81

Y15: to have a meal at the food court 0.67 11.18

Social motivation (η7) 0.62

Y16: to simply enjoy the crowds 0.54 8.27Y17: to watch people 0.83 7.85

a. Items reverse coded before scoring.

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

17/28

Loneliness, through an exploratory factor analysis, generated twofactors whose eigenvalue was above 1.0, and three items were elimi-nated due to lower factor loadings below 0.60. The first factor, inti-mate loneliness, included five items: “I feel isolated from others,” “Iam unhappy being so withdrawn,” “I feel left out,” “I am no longerclose to anyone,” and “There is no one I can turn to.” The second fac-tor,socialloneliness,includedthreeitems:“TherearepeopleIcantalkto,” “TherearepeopleI can turn to,” and “Thereare people who reallyunderstand me.” Two factors accounted for 67.3% of the total vari-ance for loneliness. By confirming the Loneliness factor structurederived from the exploratory factor analysis, two indicators for thelatent Intimate Loneliness factorwere removed dueto thefactor load-ing lower than 0.60. Conclusively, the latent variable of loneliness

consisted of two latent factors: intimate loneliness (ξ1) measured bythree indicators and social loneliness (ξ2) measured by three indicators(see Table 2). A descriptive analysis of loneliness indicates that themean score of intimate loneliness ( M = 3.13) is slightly higher thanthat of social loneliness ( M = 2.87). However, the mean of loneliness is below the midpoint, which supports a stronger relationship betweenfriends or peers among teens (Berndt & Das, 1987; Rokach, 2001) andpositive nomination in a peer group (Eronen & Nurmi, 2001).

Media usage wasclassified intotwo constructs: audiovisualmediaand printed media. The construct of audiovisual media usage (η1)consisted of two observed indicators of television and radio; printedmedia usage (η2) consisted of two observed indicators of magazineand newspaper (see Table 2). A descriptive analysis provided themean scores for two mediagroups:audiovisual media ( M = 5.41) andprinted media ( M = 4.98).

Shopping motivation was confirmed to have five constructs: ser-vice motivation (η3), economic motivation (η4), diversion motivation(η5), eating-out motivation (η6), and social motivation (η7). One itemloaded on social motivation resulted in a low coefficient but wasretained because one indicator for a latent construct is not consideredadequatetoverifyameasurementmodel(Jöreskog&Sörbom,1989).

Structural equation model. To examine causal relationships amonglatent variables (i.e., loneliness, media usage, and shopping motiva-tion), we first estimated a proposed structural model, followed by the

modified model. Theχ2

value was first evaluated, but it is very sensi-tive to a large sample size, which may cause the risk of rejecting avalid model. Therefore, we used the bic statistic adopted by R. M.

156 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

18/28

Hauser and Wong (1989) for posteriori tests: bic = L2

– df × log N ,whereL2 isthelikelihoodratioteststatisticor χ2 whenthesamplesizeis large under the assumption of multivariate normality, df is thedegreeoffreedom,and N is the sample size. Models with lower (morenegative) bic statistics areconsideredas better fit. In addition, thedif-ference between likelihood ratio test statistics for comparing twonested models is expressed as the difference betweenthe two modelsin χ2 and degrees of freedom (Bagozzi & Yi, 1989; R. M. Hauser &Wong, 1989).

As presented in Table 3, overall fit statistics of the proposedmodelsuggestedthattheχ2 value of 706.85wassignificant (df =205, p

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

19/28

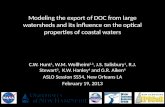

et al., 1994; Roy, 1994). Thus, finally, the path (β75) from diversionmotivation (η5) to social motivation(η7) was added in the model. Thefit of Model D in Table 3 provided a decreased χ2 value of 414.55 (df =202, p < .001) and a decreased bic statistic of –134.89. The difference between Model C and D was significant (χ2C-D = 32.15, df = 1, p < .001),which implies that the final modified Model D was acceptable. Inaddition, other indexes were within ranges for accepting the model

(GFI= 0.94; AGFI = 0.91), whichexceeded the 0.90 standard for modelfit (Kelley, Longfellow, & Malehorn, 1996). The RMSEA was also

158 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

Figure 1: Structural Model of Teens’Mall Shopping MotivationsNOTE:GFI= goodnessof fitindex;AGFI= adjustedgoodnessof fitindex;RMSEA= rootmean square error of approximation.*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Loneliness Media Usage Mall Shopping Motivation

β63 = .67***

Audio-

visual

Media

(η1)

Printed

Media

(η2)

Intimate

Loneliness

(ξ1)

Social

Loneliness

(ξ2)

ServiceMotivation

(η3)

Economic

Motivation

(η4)

DiversionMotivation

(η5)

Eating-outMotivation

(η6)

SocialMotivation

(η7)

γ 31= .42***β31 = -.26***

β62 = -.24**β61 = .18*

β41 = .15*

β51 = .18*

β32 = .21**

γ 12 = -.17**

γ 22 = -.16**γ 42 = -.19***

γ 52 = -.17**γ 71= .17**

β75 = .35***

ψ 21= .62***

Goodness of Fit Statistics

χ2

= 414.55 (df = 202, p = .00)

GFI = 0.94

AGFI = 0.91

RMSEA = 0.045

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

20/28

reduced from 0.066 to 0.045, which indicates a better fit. Accordingly,

thefinalrevisedmodelillustratedinFigure1wasdeemedtobeaverygood fit. The final structural model illustrated in Figure 1 includessignificant standardized path coefficients.

Hypotheses Testing

Hypothesis 1. Loneliness was significantly related to shoppingmotivations, but the effects on shopping motivation differed by theLoneliness factor, whether it was intimate loneliness or social loneli-ness. More specifically, the Intimate Loneliness factor had positivedirecteffects on service motivation(γ 31 =.42, p < .001) and social moti-vation (γ 71 = 0.17, p < .01). Teens who feel emotionally isolated tendtoenjoybeingsurroundedbythecrowdsandtouseservicecenters(e.g.,

medical/dental/vision care offices, banks) or enjoy interior design. Itis notable that the indirect effect of intimate loneliness on eating-outmotivationvia theService Motivational factor (γ 31 × β63 =0.28, t =5.09,

p < .001) was slightly greater than its direct effects on social motiva-tion (0.17). Therefore, this finding supports Hypothesis 1a, suggest-ing that lonely teens who feel isolated from others or feel left out arelikely to be motivated to shop for enjoying a crowded mall atmo-sphere and retail environments, such as interiors and service centers,which, in turn, leads to eating in food courts or snack corners.

As compared to intimate loneliness, social loneliness resulted insignificant negative effects on economic motivation (γ 42 = –.19,

p < .001) and diversion motivation (γ 52 = –.17, p < .01). Therefore,

Hypothesis 1b mentioning that social loneliness will decrease mallshopping motivations is supported. Teens who are socially isolated

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 159

TABLE 3: Summary of Goodness of Fit Statistics for Structural Models

Model 2

df Bic GFI AGFI RMSEA

A. Proposed model 706.85* 205 149.25 0.90 0.86 0.068

B. Model A + ψ 21 537.77* 204 –17.11 0.92 0.89 0.056

C. Model B + β63 446.70* 203 –105.46 0.93 0.91 0.048D.Model C + β75 414.55* 202 –134.89 0.94 0.91 0.045

NOTE:Bic = statistics based on Bayesian theory forposteriori tests;GFI = goodness offit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness of fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error ofapproximation.*p < .001

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

21/28

wereless likely to visitthe mall for searching for good prices,huntingfor bargains, and comparison shopping. This finding somewhat sup-ports the literature that teen consumers who had many friendstended to be well informed andsophisticated becausetheir friends orpeers were primary sources of shopping information or knowledge(Lewis et al., 1995; Moschis & Moore, 1979). The finding that sociallylonelyteens who feel a lack of socialnetworks were less likely to shopfordiversion reflects Hirschman’s (1984) argument that a person whofeels socially isolatedparticipates in forbidden forms of consumptionto meet his or her sensory desires (e.g., uninhibited parties, drug andalcohol experimentation).

Conclusively, for teens, the two dimensions of loneliness—intimate loneliness and social loneliness—play important roles as

antecedents of different mall shopping motivations. The effects of intimate loneliness and social loneliness on mall shopping motiva-tions were opposite in direction, that is, positive and negative,respectively.

Hypothesis 2. With respect to the relationship between lonelinessand media usage, intimate loneliness was not significantly related tomedia usage, whereas social loneliness was significantly related tomedia usage. Teens who feel isolated from others may not benefitfrommediausageasaneffectivevenuetoalleviatetheirloneliness.Tothe contrary, social loneliness negatively influenced both types of media usage: audiovisual media (γ 12 =–.17, p

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

22/28

increases, their knowledge of products and prices increases andresults in visiting the mall for specific reasons. Considering Shim’s(1996) contention that the visual commercial media (e.g., television)motivated teen consumers to shop for novelty or sensational anddiversion needs, the shopping mall can act as a venueto support theirpsychological needs.

Printed-media usage resulted in a positive effect on service moti-vation (β32 = 0.21, p = 0.01) and a negative effect on eating-out motiva-tion (β62 = –.24, p < .01). Teens who used more printed media werelikely to use more service providers, whereas they were less likely togotomallsfor havinga meal orsnack. Indirecteffectswerealsofound between two media usages and eating-out motivation via the mediat-ing service motivation. Audiovisual media resulted in a negative

indirect effect on eating-out motivation [(β31) × (β63) = –.17, t = –2.98, p < .01], whereas the printed media had a positive indirect effect oneating-out motivation [(β32) × (β63)=0.14, t =2.48, p

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

23/28

media usage and particular shopping needs in the mall environmentand thus encourage development of programs to meet these needs.Foremotionallyisolatedteens,themallcanprovidethemwithoppor-tunities to visit service providers, enjoy interior design, eat, andwatch the crowds in the mall. For these teens, the formats of foodcourts, snack corners, or restaurants need to be explored to ensurethat theyserveto fulfill socializing needs,suchas meetingfriends andsolving loneliness. Special mall events and exhibits might enhancethis effect. For socially isolated teens, expressive mall attributes (e.g.,prestige, attractive ambience) may be more important than economicmall attributes (e.g., reduced prices or comparison shopping). Inaddition, the mall should provide goal-oriented tenants or activities(e.g., cinema, video arcade), because socially isolated teens are not

motivatedbypassiveactivities(e.g., browsing)to alleviate boredom.Usage of media seems to be related to different types of shopping

motivations. Audiovisual media usage (i.e., television, radio)increased mall shopping for fulfilling diversion or economic motiva-tions, whereas printed media usage (i.e., magazine, newspaper)increased teens’ mall visits of service providers. This information can be used as a basis for developing media plans targeting teens. Tar-geted television and radio messages could advertise malls’ specialpromotions, sweepstakes, and complementary lines of productsofferedforcomparisonshopping.Thesemessagescanbeconveyedinan attractive and exciting shopping environment appealing to teenswho need diversion from their routine daily life. Magazines andnewspaperscould includeinformation on the availability of services,such as hair styling, vision care, and shoe repair.

Results increase the theoretical understanding of teen consumers’shoppingmotivations and suggest directions for retailers and educa-torsastheyestablishprogramsdirectedatteens.Inparticular,thecrit-ical role of shoppingto alleviate teens’ loneliness provides a potentialavenue for reshaping or recharacterizing the shopping mall. Mallscan be established as multipurpose retail/community centers thatprovide appropriate intervention and treatment programs for lonelyteens and supplement programs created by social agencies. Retail business can boost teen socialization by providing entry-level jobsthat are fun and exciting to teens. The role of the mall becomes moreimportant to meet this goal, given the fact that loneliness has been

linked to a variety of other serious individual and social problems,including alcoholism (Nerviano & Gross, 1976), adolescent

162 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

24/28

delinquent behavior (Brennan & Auslander, 1979), and suicide(Wenz, 1977).Mall owners and retailers should ensure that shopping malls are

hospitable to teen consumers who are lonely by providing moresociallysupportive functions that canbe performed by service agentsand salespeople. They could provide teen-oriented social interac-tions, such as special mall events (e.g., music, fashion shows) andexhibits. In addition, their experience can be enhanced by attractivedécor and music directed at teen consumers. However, it is arguedthat teens bring problems intomalls viashoplifting, overspending, orusing parents’ credit cards, and thus some malls enforce age restric-tions for teens underage 16unlesstheyare accompanied bytheirpar-ents or someone older than 19 years (Chatzky, 2002; Saelens, 1998;

Terlep, 1997). Professionals working in the area of family and con-sumer sciences should consider programs to educate teens and par-ents to develop social ethics in shopping malls. Likewise, mall retail-ers need to emphasize family-oriented products or services andspecial community events during weekends.

The findings of this study should be interpreted with caution dueto several limitations. The samplingwas limited to majorcities in lim-ited geographic locations. Unquestionably, geographical locationsother than the major cities selected for this study should be consid-ered to replicate the findings of the study. In addition, the hypothesessetforth in this study specifically dealt with theshoppingmotivationsof teen consumers with regard to mall shopping. With increasingdebate on the vitality of mall shopping as challenged by growth innonstore retailing (i.e., Internet shopping), theoretical considerationsshould be given to the shopping motivations of teen consumers fornontraditional channels of retailing.Researchcould focus ontheneedfor a revised theoretical structure based on shopping motivation. Forinstance, teens’ shopping associated with a specific product (e.g.,clothing) or brand preference (Taylor & Cosenza, 2002) should beexamined for better understanding teens’ shopping motivations. Inaddition, the antecedents of mall shopping motivation could includedemographic (e.g., gender and ethnicity) and psychographic vari-ables, such as self-esteem, family communication pattern, andmaterialism (Carlson, Walsh, Laczniak, & Grossbart, 1994; Darley,1999).

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 163

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

25/28

REFERENCES

Anderson, C. (2000). Survey: The young: Youth, Inc. The Economist, 357(8202), S9-S10.Arnett, J. J. (1995). Adolescents’ uses of media for self-socialization. Journal of Youth &

Adolescence, 24(5), 519-533.Arnett, J. J., Larson, R., & Offer, D. (1995). Beyond effects: Adolescents as active media

users. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 24(5), 511-518.Bagozzi,R. P., & Yi, Y. (1989).On theevaluationof structuralequationmodels. Journal of

the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.Baker, J., & Haytko, D. (2000). The mall as entertainment: Exploring teen girls’ total

shopping experiences. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 7(1), 29-58.Barbin, B., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic

and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644-656.Bellenger,D.N.,&Korgaonkar,P.K.(1980).Profilingtherecreationalshopper. Journal of

Retailing, 56(3), 77-92.Bellenger, D. N., Robertson, D. H., & Greenberg, B. A. (1977). Shopping center patron-

age motives. Journal of Retailing, 53(2), 29-38.Berndt,T. J.,& Das,R. (1987).Effectsof popularity andfriendship on perceptionsof the

personality and social behavior of peers. Journal of Early Adolescence, 7, 429-439.Bloch,P.,Ridgway,N.M.,&Dawson,S.A.(1994).Theshoppingmallasconsumerhabi-

tat. Journal of Retailing, 70(1), 23-42.Bloch, P., Ridgway, N., & Nelson, J. (1991). Leisure and the shopping mall. Advances in

Consumer Research, 18(1), 445-452.Brennan, T., & Auslander, N. (1979). Adolescent loneliness: An exploratory study of social

and psychological pre-dispositions and theory. Unpublished manuscript. Boulder, CO:Behavioral Research Institute.

Carlson, L., Walsh, A., Laczniak, R. L., & Grossbart, S. (1994). Family communicationpatterns and marketplace motivations, attitudes, and behaviors of children andmothers. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 28(1), 25-53.

Cebrzynski, G. (1999,March8). Restaurants maywant to getwiredto reach GenerationY youths. Nation’s Restaurant News, 33(10), 14.

Chatzky, J. (2002, June 17). Aguide for silver spoon parents. Time, 159(24), 82.Churchill, G. A. Jr., & Moschis, G. P. (1979). Television and interpersonal influences on

adolescent consumer learning. Journal of Consumer Research, 6(1), 23-35.Cuneo, A.Z. (2000).Malls move to capturesales lost to theNet. Advertising Age, 71(32),

38-46.Darley, W. K. (1999). The relationship of antecedents of search and self-esteem to ado-

lescent search effort and perceived product knowledge. Psychology & Marketing,16(5), 409-427.

Ebenkamp, B. (2000, February 28). Teen-Y shoppers. Bandweek , 41(9), 28.Eronen, S., & Nurmi, J. E. (2001). Sociometric status of young adults:Behavioral corre-

lates,and cognitive-motivationalantecedents and consequences. International Jour-nal of Behavioral Development, 25(3), 203-213.

Ferle, C. L., Edwards, S. M., & Lee, W. (2000). Teens’ use of traditional media and theInternet. Journal of Advertising Research, 40(3), 55-65.

Fetto, J. (2002). Teen chatter. American Demographics, 24(4), 14.

Forman,A. M.,& Sriram,V. (1991).The depersonalization of retailing:Its impact on thelonely consumer. Journal of Retailing, 67(2), 226-243.

164 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

26/28

Freeman, L.(1999,April28). Teen-agers turn heartthrobsfor eager publishers. Advertis-ing Age, 70(18), S8.Goff, L. (1999). Don’t miss the bus! American Demographics, 21(8), 48-54.Graham, E. (1988, May 13). The call of the mall. The Wall Street Journal, p. 7R.Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E.,Tatham,R. L.,& Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis

(4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.Hauser, R. M.,& Wong,S. (1989).Sibling resemblance and intersibling effectsin educa-

tional attainment. Sociology of Education, 62(3), 149-171.Hauser, S. T., & Bowlds,M. K. (1990).Stress, coping,and adaptation.In S. S. Feldman&

G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 388-413). Cam- bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hirschman, E. C. (1984). Experience seeking: A subjectivist perspective of consump-tion. Journal of Business Research, 12(1), 115-136.

Huston, A. C., & Alvarez, M. M. (1990). The socialization context of gender role devel-opment in early adolescence. In R. Montemayor, G. Adams, & T. Gullotta (Eds.),Fromchildhood to adolescence:A transitionalperiod? (pp.156-182).Newbury Park, CA:

Sage. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1989). LISREL 7: A guide to the program and applications

(2nd ed.). Chicago: JÖRESKOG and SÖRBOM/SPSS Inc. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). Windows LISREL 8.12a. Chicago: Scientific Soft-

ware International.Kang, J.,Kim,Y.,& Tuan, W. (1996).Motivationalfactorsof mallshoppers: Effectsof eth-

nicity and age. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 3(1), 7-31.Kelly, S. W., Longfellow, T., & Malehorn, J. (1996). Organizational determinants of ser-

vice employees’ exercise of routine, creative, and deviant discretion. Journal of Retailing, 72(2), 135-157.

Kim, Y., & Kang, J. (1997). Consumer perception of shopping costs and its relationshipwith retail trends. Journal of Shopping Center Research, 4(2), 27-62.

Kostelecky, K. L., & Lempers, J. D. (1998). Stress, family social support, distress, andwell-being in highschoolseniors. Family& Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 27(2),125-145.

Kurdek, L. (1987). Gender differences in the psychological symptomatology and cop-ing strategies of young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 7, 395-410.

Lee, S., Lennon, S., & Rudd, N. (2000). Compulsive consumption tendencies amongtelevision shoppers. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 28(4), 463-488.

Lewis, M., Dyer, C. L.,& Moran, J. D. (1995).Parental and peer influences on the cloth-ing purchases of female adolescent consumers as a function of discretionaryincome. Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences, 87, 15-20.

Marcoen, A., & Goossens, L. (1993). Loneliness, attitudes aloneness, and solitude: Agedifferences and developmental significance during adolescence. In S. Jackson &H. Rodriguez-Tome (Eds.), Adolescence and its social worlds (pp.197-228).New York:Lawrence Erlbaum.

McCord, J. (1990). Problem behaviors. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At thethreshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 414-430). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univer-sity Press.

McGrath, C. (1998). Busy teenagers. American Demographics, 20(7), 37-38.

McWhirter,B. T.(1997). Loneliness, learnedresourcefulness, and self-esteem in collegestudents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 75(6), 460-469.

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 165

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

27/28

Moore, D.,& Schultz,N. R. (1983).Loneliness at adolescence: Correlates,attributes andcoping. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 12, 1-8.Moore, R. L., & Moschis, G. P. (1981). The impact of newspaper reading on adolescent

consumers. Newspaper Research Journal, 2(4), 1-8.Moschis, G. P. (1976).Shopping orientations andconsumer uses of information. Journal

of Retailing, 52(2), 61-70.Moschis, G. P. (1987). Consumer socialization. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.Moschis, G.P., & Churchill, G.A. (1979).Ananalysisof theadolescentconsumer. Journal

of Marketing, 43(3), 40-48.Moschis, G. P., & Moore, R. L. (1979). Decision making among the young: A socializa-

tion perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 6, 101-112.Moschis, G. P., & Moore, R. L. (1982). A longitudinal study of television advertising

effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 279-286.Mowen, J. C. (1995). Consumer behavior (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.Nerviano, V. J.,& Gross,W.F.(1976).Loneliness andlocusof control foralcoholicmales:

ValidityagainstMurrayneedandCattelltraitdimensions. Journal of Clinical Psychol-ogy, 32, 479-484.

Omelia, J. (1998).Understandinggeneration Y: Alook at thenext waveof U.S. consum-ers. Drug & Cosmetic Industry, 163(6), 90-92.

Perlman, D. (1988). Loneliness: A life-span, family perspective. In R. Milardo (Ed.),Families and social networks (pp. 190-220). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Richardson, L. (1993, August). “Consumers in the 1990s”: No time or money to burn.Chain Store Age Executive, pp. 15A-17A.

Roe,K. (1995).Adolescents’ useof sociallydisvaluedmedia:Towarda theory of mediadelinquency. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 24(5), 617-631.

Rokach,A. (2001).Strategies of coping withloneliness throughout thelifespan.CurrentPsychology: Development, Learning, Personality, Social, 20(1), 3-18.

Roy, A. (1994). Correlates of mall visit frequency. Journal of Retailing, 70(2), 139-161.Rubenstein, C.,& Shaver, P. (1980).Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and

therapy. New York: John Wiley.Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale:

Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality & Social Psy-chology, 39(3), 472-480.

Saelens, E. (1998, March 27). Bill may limit mall-goers. The State News. Retrieved fromwww.statenews.com/editionsspring98/032798/ci_mall.html

Shim, S. (1996).Adolescent consumer decision-making styles: The consumer socializa-tion perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 13(6), 547-569.

Shim, S.,& Gehrt, K. C. (1996).Hispanic and Native American adolescents: An explor-atory study of their approach to shopping. Journal of Retailing, 72(3), 307-324.

Stone, G. P. (1954). City shoppers and urban identification: Observations on the socialpsychology of city life. American Journal of Sociology, 60, 36-45.

“The survey says”: Teen-agers want to shop ’til they drop. (1994, November). ChainStore Age Executive, pp. 91-96.

Tauber, E. M. (1972). Why do people shop? Journal of Marketing, 36, 46-49.Taylor, S. L., & Cosenza, R. M. (2002). Profiling later aged female teens: Mall shopping

behavior and clothing choice. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19(5), 393-408.

Terlep, S. (1997, June 12). Senate mulls letting malls limit teen-agers. The State News.Retrieved from www.statenews.com/editionssummer97/061297/nw_mall.html

166 FAMILY AND CONSUMER SCIENCES RESEARCH JOURNAL

-

8/15/2019 Teens’ Mall Shopping Motivations

28/28

Ward,S.,Wackman,D.B.,&Wartella,E.(1977). How children learn to buy: The developmentof consumer information-processing skills. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.Weiss, R.(1974).Theprovisionsof socialrelationships. In Z.Rubin(Ed.), Doingunto oth-

ers (pp. 17-26). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.Wenz, F. Z. (1977). Seasonal suicide attempts and forms of loneliness. Psychological

Report, 40, 807-810.Wilson, J., & MacGillivray, M. (1998). Self-perceived influences of family, friends, and

media on adolescent clothing choice. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal ,26(4), 425-443.

Zollo, P. (1995). Talking to teens. American Demographics, 17(11), 22-28.

Kim et al. / TEENS’ MALL SHOPPING MOTIVATIONS 167