Tech Resrep Divisional Performance Measurement 2005

description

Transcript of Tech Resrep Divisional Performance Measurement 2005

-

Divisional Performance Measurement:An Examination of the Potential Explanatory Factors

Research Report

Professor C DruryHuddersfield University

H EL-ShishiniHuddersfield University

-

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51.1 Research problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51.2 Research objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61.3 Research boundaries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61.4 Definition of terms used throughout the thesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61.5 Outline of the report. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

2. Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.2 Alternative forms of organisational structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82.3 Factors influencing the emergence of divisionalised companies . . . . . . . . . 102.4 The advantages and disadvantages of divisionalisation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132.5 The pre-requisites for successful divisionalistion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132.6 Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

3. Divisional Performance Measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 153.2 Distinguishing between divisional and managerial performance . . . . . . . . . 153.3 Limitations of financial performance measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 163.4 Improving financial performance measures: Economic value added (EVA). 173.5 Integrating financial and non-financial measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 183.6 Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

4. Controllability and Cost Allocations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204.2 Categories of uncontrollable costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204.3 Distinguishing between controllable and uncontrollable costs . . . . . . . . . . 204.4 Reasons for the allocation of uncontrollable costs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214.5 Reasons for non-allocation of some of the costs of common resources . . 234.6 Empirical evidence relating to cost allocation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234.7 Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

5. The Research Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.2 The need for further studies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.3 Data collection method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.4 Sample selection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265.5 The respondents. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275.6 The response rate. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275.7 Questionnaire content . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285.8 Tests for non-response bias . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 285.9 Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Divisional Performance Measurement1

Contents

-

Divisional Performance Measurement 2

6. Survey Findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 296.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 296.2 The use of different performance measures to evaluate

divisional managerial performance and the economic performanceof the divisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

6.3 The relative importance of different financial measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 306.4 Economic value added usage . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 316.5 The influence of divisional management and

group headquarters management in setting financial targets . . . . . . . . . . . 316.6 Non-financial measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 316.7 The costs of common resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 326.8 The application of the controllability principle common resource costs . . 326.9 The application of the controllability principle to

group business sustaining general and administration costs . . . . . . . . . . . . 346.10 The application of the controllability principle to

uncontrollable environmental factors and divisional interdependencies . . 346.11 The extent to which uncontrollables are informally taken into account . . 356.12 Importance of factors influencing organisations to allocate the

cost of common resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 356.13 Importance of factors influencing organisations not to allocate

common resource costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 386.14 Treatment of the variance between budgeted

and actual costs of common resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 386.15 Degree of satisfaction with the performance measurement system . . . . . 406.16 Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

7. Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.2 Motivation for the research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.3 A summary of the research objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.4 A discussion of the major findings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427.5 Limitations of the research and areas for further study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

Appendix 1: Survey Questionnaire . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

-

Divisional Performance Measurement3

Most large organisations adoptdivisionalised structures. The manner inwhich divisional performance iscontrolled and measured is, therefore, ofparticular importance. This reportpresents the research findings of a postalquestionnaire relating to the applicationof the controllability principle anddivisional performance measurement inUK companies.

A central issue of performance reporting is whether divisionalmanagers should be held accountable for items that theycannot influence by their actions. The conventional wisdomof management accounting, as reflected in textbooks,advocates that the evaluation of a managers performanceshould consist of only those factors under a managerscontrol. Therefore, divisional managerial performancemeasures should include only the items controllable bydivisional managers. Or, performance measurement should bebased on the application of the controllability principle.

The limited empirical evidence, however, suggests that theallocation of uncontrollable costs for responsibilityaccounting purposes is widespread and that thecontrollability principle often does not appear to be appliedin practice. It is apparent that the traditional two-foldclassification of costs being controllable or non-controllableis too simplistic and that the application of the controllabilityprinciple lies along a continuum. At one extreme, there is noapplication of the controllability principle, with companiesholding managers responsible for all uncontrollable factors. Atthe other extreme, there is the full application of thecontrollability principle, where companies tend to holddivisional managers responsible only for controllable factors.In between these extremes, managers may be heldaccountable for some uncontrollable factors.

Besides the application of the controllability principle, thechoice of appropriate measures of divisional managerialperformance has been widely debated in managementaccounting literature.

One area of debate is whether based on the application ofthe controllability principle different performance measuresshould be used to evaluate the performance of divisionalmanagers and the economic performance of the divisions, orwhether a single measure should be used for both purposes.

Another area of debate relates to the choice of appropriateperformance measures. Traditionally, the debate wasconcerned with which traditional financial measures (forexample, net profit before or after taxes, controllable profit,residual income, return on investment) should be used. Overthe past decade, new measures have emerged, such aseconomic value added (EVA) and the balanced scorecard.Non-financial measures have also been given moreprominence and the relative emphasis that should be givento financial and non-financial measures, and how they shouldbe integrated, has also been subject to debate.

In view of these developments and the fact that most ofthe previous empirical research was undertaken more than 20years ago when the business environment and managementpractices were very different from those existing today it isappropriate to undertake empirical research relating to theapplication of the controllability principle and divisionalperformance measurement in UK companies.

Executive Summary

-

The research objectives are to:

investigate the use of financial and non-financialperformance measures in evaluating divisional managersperformance;

identify the level of the application of the controllabilityprinciple, in terms of the identified uncontrollable factors;

identify the influence of the level of the application ofcontrollability principle on the degree of satisfaction withthe divisional performance measurement system; and

investigate the relationship between the use ofnon-financial performance measures and the degree ofsatisfaction with the performance measurement system.

The following is a summary of the major research findings:

the majority of companies did not use identical measuresfor evaluating the performance of divisional managers andthe economic performance of the divisions;

target profit before charging interest on capital wasconsidered to be the most important measure used toevaluate the performance of divisional managers by 55 percent of the organisations, target profit after charginginterest on capital (residual income) was considered themost important measure by 14 per cent of theorganisations. The widely-cited target return on capitalemployed measure was ranked as the most importantmeasure by only 7 per cent of the respondents;

EVA was used by 23 per cent of the respondents as amethod of evaluating the performance of divisionalmanagers. A further 11 per cent of the respondentsplanned to introduce EVA within the next two years. Thefindings also suggested that 43 per cent of those using EVAdid not make any adjustments to accounting numbers tocompensate for the distortions introduced by generallyaccepted accounting principles (GAAP). This suggests thatthese companies are computing a residual income measurerather than a true EVA measure;

non-financial measures were used to evaluate divisionalperformance by 78 per cent of the respondents;

the balanced scorecard was used to evaluate divisionalperformance by 42 per cent of the respondents and 18 percent used the European Foundation for QualityManagements (EFQM) Excellence Model;

overall, the amount of the costs of common resources as apercentage of divisional turnover is relatively low, being 10per cent of divisional turnover or less for approximately73% of the responding organisations;

different categories of non-controllable costs wereidentified and the findings indicated that a significantmajority of organisations allocate all, or most, of eachcategory of non-controllable costs for measuring divisionalmanagerial performance;

the most important reasons for allocating commonresource costs were related to an attempt to useallocations as surrogates for the costs that would beincurred if the divisions operated as independentcompanies. Encouraging divisional managers to take agreater interest in the costs of shared resources and

putting pressure on resource centre managers to controltheir costs were also considered to be important reasonsfor cost allocations. Measurement problems relating toseparating controllable and non-controllable costs and costallocations being undertaken because of companytraditions were relatively unimportant reasons;

despite the fact that the majority of companies do notfully apply the controllability principle in terms of costallocations, the responses to why some of the costs ofcommon resources were not allocated indicated that theapplication of controllability was the dominant reason;

a further aspect of the application of the controllabilityprinciple was investigated by examining how the variancebetween budgeted and actual allocated uncontrollablecommon costs was dealt with. Within the uncontrollablecost category, approximately 70 per cent of divisionalmanagers were not held accountable for the variance. Thisindicates the application of the controllability principle, asprotecting managers from differences arising frominefficiencies occurring outside of their divisions;

most companies do apply the controllability principle insome situations but not in others. There is a much greatertendency not to fully apply the controllability principle interms of allocating uncontrollable costs to divisionalmanagers as a means of increasing their targetperformance measure. In contrast, it tends to be applied atthe variance analysis stage. The findings suggest that thecontrollability principle is considered to be important andis widely used in practice. However, it is applied in a moreflexible manner than depicted by conventional wisdom. Itwould appear that the need to use allocations as amechanism to increase target divisional profit to cover afair share of central costs outweighs the apparentinfringement of the controllability principle that occurswith the allocations;

several factors were examined that may explain the level ofapplication of the controllability principle. They includedthe location of the head office (UK or overseas), the listingstatus (listed or unlisted) and the extent to whichuncontrollable factors were informally taken into account.None of the factors were significant. In particular, noevidence was found to suggest that those companies thatdid not formally apply the controllability principle weremore likely to take into account uncontrollable factorsinformally when compared with those companies thatapplied the controllability principle more extensively;

there was no significant relationship between the level ofautonomy or the application of the controllability principleand the degree of satisfaction with the performancemeasurement system.

there was a significant negative association between theextent of the use of non-financial measures and the degreeof satisfaction with the performance measurement system.This indicates that the greater the use of non-financialmeasures, the lower the satisfaction with the performancemeasurement system; and

there was no evidence to support the hypothesis that, thelower the level of application of the controllabilityprinciple, the greater the use of non-financial measures.

Divisional Performance Measurement 4

-

Divisional Performance Measurement5

1.1 Research problemSurveys in the UK (Scapens et al, 1982; Drury et al, 1993),USA (Reece and Cool, 1978) and Australia and New Zealand(Skinner, 1990) indicate that the majority of companies inthese countries have adopted divisionalised organisationalstructures. The manner in which divisional performance iscontrolled and measured is, therefore, of particularimportance.

A central issue of responsibility accounting is whether adivisional manager should be held accountable for items thathe or she cannot influence by his or her actions (for example,Horngren et al. 1997, p. 192; Atkinson et al, 1997, p. 564;Choudhury, 1986, p. 189; Merchant, 1987, p. 316). Themanagement accounting literature (for example, Merchant,1998) distinguishes between the economic performance of adivision and the performance of its manager, advocating thatthe evaluation of a managers performance should consist ofonly those factors under a managers control. Therefore,divisional performance measures (whatever the measure inuse) should include only the items controllable by divisionalmanagers. In other words, performance measurement shouldbe based on the application of the controllability principle.The empirical evidence, however, suggests that the allocationof uncontrollable costs for responsibility accounting purposesis widespread and that the controllability principle often doesnot appear to be applied in practice, in respect ofuncontrollable costs.

Previous research (such as, Ramadan, 1985; Merchant, 1985)has focused on whether costs are allocated to divisions and based on this observation conclude whether thecontrollability principle is being applied. Merchant (1987),McNally (1980) and Skinner (1990), however, suggest thatsuch a two-fold classification is too simplistic and that theapplication of the controllability principle has different levelslying along a continuum. At one extreme, there is noapplication of the controllability principle. Companies holddivisional managers responsible for all uncontrollable factors,including uncontrollable costs, all of the uncontrollableeffects of environmental uncertainty and divisionalinterdependencies. At the other extreme, there is the fullapplication of the controllability principle, where companiestend to hold divisional managers responsible only forcontrollable factors. In between these extremes, managersmay be held accountable for some uncontrollable factors.

Previous research has not given much attention to identifyingwhere companies applying the controllability principle fallwithin this continuum, or the factors influencing the differentapplications of the controllability principle. This has resultedin several prominent researchers advocating the need forfurther research relating to the application of thecontrollability principle and the potential explanatory factorsthat might explain the different levels of application (forexample, Atkinson et al, 1997, p. 84; Merchant et al, 1995, p.635). In particular, after conducting case study researchrelating to the application of the controllability principlewithin a small number of divisionalised companies, Merchantet al (1995, p. 635) considered the small sample size alimitation of his study and called for future research using alarger sample.

Apart from the application of the controllability principle, thechoice of appropriate measures of divisional managerialperformance has been widely debated in managementaccounting literature. The conventional wisdom (includingAmey, 1969; Amey and Egginton, 1973; Emmanuel and Otley,1976) that emerged from this debate suggests that, forinvestment centres where divisional managers havesignificant authority for making capital investment decisions,or those profit centres where divisional managers caninfluence significantly the investment in working capital,residual income is the most appropriate measure of divisionalperformance. For those profit centres where divisionalmanagers cannot influence the investment in working capital,conventional wisdom advocates that return on investment(ROI) or target absolute profit (normally derived from assetsemployed in the division multiplied by a target return oninvestment) should be used. Until recently, accountingtextbooks (such as Drury, 1996; Kaplan and Atkinson, 1989;Horngren et al, 1999) advocated residual income as themajor financial measure.

Despite this recommendation, residual income does notappear to be widely used in practice (Mauriel and Anthony,1966; Reece and Cool, 1978; Scapens and Sale, 1981; Skinner,1990). Furthermore, residual income has recently beenrefined and renamed as EVA.

Economic value added (EVA) is now being marketed byconsultants to measure the financial performance ofdivisionalised companies. Therefore, it is important toinvestigate the financial performance measures that arecurrently being used to measure divisional performance.Management accounting literature (Emmanuel et al, 1995,p. 242; Keating, 1997, p. 267) suggests that differentmeasures could be used in order to evaluate the economicperformance of divisions and the managerial performance ofdivisional managers. Despite this suggestion, the literaturereview was unable to trace any studies that have examinedwhether divisionalised companies use different performancemeasures for measuring the performance of their divisionsand the performance of divisional managers.

1. Introduction

-

Recently, much publicity has been given in managementaccounting literature to two areas that are related to themeasurement of divisional performance. The first is toimprove the financial performance measures (for example,EVA). The second is to integrate financial and non-financialperformance measures (Kaplan and Norton, 1996).

There is little empirical research relating to the use ofimproved financial performance measures and the use ofnon-financial performance measures in measuring divisionalmanagerial performance. In addition, controllability principleliterature has emphasised the application of the principle, inthe context of financial performance measures, withoutconsidering the relationship between the use of non-financialperformance measures and the controllability principle.

1.2 Research objectivesThe objectives of the research are to:

investigate the use of financial and non-financialperformance measures in evaluating divisional managersperformance;

identify the level of the application of the controllabilityprinciple in terms of the identified uncontrollable factors;

identify the influence of the level of the application of thecontrollability principle on the degree of satisfaction withthe divisional performance measurement system; and

investigate the relationship between the use ofnon-financial performance measures and the degree ofsatisfaction with the performance measurement system.

1.3 Research boundariesIt is apparent from sections 1.1 and 1.2 that this researchfocuses on the formal performance measurement system andthe issue of performance evaluation in terms of comparingthe targeted and actual performance. It does not examinehow the outputs from the performance measurement system(in terms of the rewards or punishments) are used tomotivate managers to achieve organisational goals. How theperformance system is used to evaluate and reward divisionalperformance is considered to be beyond the scope of thisresearch. An examination of the influence of the rewardstructure warrants a separate research project focusing,possibly, on a single organisation instead of the cross-sectional postal survey method that was used for this study.

1.4 Definition of terms used throughout the thesisThroughout this report, various terms are used widely thatmay be subject to different interpretations by readers. Inorder to avoid any ambiguity, the terms are defined in thissection. It should also be noted that definitions of the firstthree items were provided within the survey to ensure thatall respondents applied uniform definitions in their answers.

DivisionFor the purpose of this research, a division is defined as asegment within the organisation where the divisional chiefexecutive has responsibility for most of the production andmarketing activities of the segment and is accountable for aprofitability measure. Sometimes, the divisional chiefexecutive has responsibility for the investment activities. Thedivision may be known within the organisation as a profit orinvestment centre, subsidiary, branch, sector or business unit.

Common resources costsThe term common resources applies to resources or servicesprovided by the head office for the benefit of two or moredivisions within the organisation. Common resources costsinclude central costs relating to activities such as:

data processing; research and development; marketing services; training programmes; personnel; accounting; internal auditing; legal services; and group planning.

Distinguishing between the economic performance of thedivisions and the managerial performance of theirmanagersSome companies distinguish between the economicperformance of the divisions and the managerial performanceof their managers or chief executives. As a result, somecompanies use different performance measures to evaluatethe economic performance of the divisions and theperformance of divisional managers. A separate divisionalmanagerial performance measure is one that excludes thosecosts that cannot be controlled or influenced by a divisionalmanager, whereas divisional economic measures generallyinclude the allocation of uncontrollable costs based on theprinciple that if, the divisions were independent companies,they would have to bear such costs.

Uncontrollable factorsFor the purpose of this research, uncontrollable factorsinclude:

uncontrollable costs of common resources; the group general and administrative costs; uncontrollable environmental factors such as changing

economic conditions, competitors actions and businessclimates; and

the effects of divisional interdependencies.

Divisional Performance Measurement 6

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Introduction7

Level of application of the controllability principleTwo extreme levels of the application of the controllabilityprinciple have been identified. The first is the low level ofapplication and has the following characteristics:

all, or most, of the uncontrollable common resources costsand the group general and administrative costs areallocated to divisions; and

the effects of uncontrollable environmental factors anddivisional interdependencies are not taken into accountwhen measuring divisional managerial performance.

The high level of application of the controllability principlehas the following characteristics:

the uncontrollable common resources costs and the groupgeneral and administrative costs are generally not allocatedto divisional managers; and

the effects of uncontrollable environmental factors anddivisional interdependencies are taken into account, to aconsiderable extent, when measuring divisional managerialperformance.

In between the high and low level of application of thecontrollability principle, there are many levels of applicationof the controllability principle.

1.5 Outline of the reportThe report consists of seven chapters.

Chapter 1 provides an identification of the research problem,research objectives, research boundaries and a brief summaryof the definition of the terms used throughout the report.

In Chapter 2, the historical background relating to theemergence of divisionalised companies is described. Thischapter also discusses the different interpretations of thefactors influencing the emergence of the divisionalisedstructure. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages ofdivisionalisation and the pre-requisites for successfuldivisionalisation are discussed.

Chapter 3 describes the different financial performancemeasures that are presented in literature to evaluatedivisional performance and provides a summary of theempirical studies relating to the usage of these measures.

Chapter 4 provides a description of the controllabilityprinciple and identifies the different categories ofuncontrollable costs. In addition, the findings and limitationsderived from previous empirical studies are summarised.

Chapters 5-7 focus on describing the research. In Chapter 5,the research methods are described. Chapter 6 presents theresearch findings. Finally, Chapter 7 discusses the researchfindings, limitations of the research and suggestions forfuture research.

-

2.1 IntroductionThis chapter focuses on the historical background and factorsinfluencing the emergence of divisionalised companies. It isorganised as follows:

section 2.2 describes the alternative forms oforganisational structures and responsibility centres;

section 2.3 describes the factors that have influenced theemergence of divisionalised companies;

the advantages and disadvantages of divisionalisation arepresented in section 2.4;

section 2.5 describes the pre-requisites for successfuldivisionalisation; and

the final section, Section 2.6, provides a summary of thechapters content.

2.2 Alternative forms of organisational structuresAccording to Child (1972, p. 2), the term structure is definedas: the formal allocation of work roles and the administrativemechanisms to control and integrate work activities,including those which cross formal organisation boundaries.

Given that structure may differ between organisations, it isappropriate to identify the main types so that a divisionalisedstructure can be contrasted with alternative forms oforganisational structure.

According to management accounting literature,organisational structure can be classified into two maingroups: decentralised and centralised. Simon (1954) presentsthe following definition to distinguish between a centralisedand decentralised organisation.

An administrative organization is centralized to the extentthat decisions are made at relatively high levels in theorganization; decentralized to the extent that discretionand authority to make important decision are delegated bytop management to lower levels of executive authority.(Simon, 1954, p. 1)

This definition indicates that the distinction betweencentralisation and decentralisation relates to the delegationof authority to make important decisions. If such authority isconcentrated at the higher organisational level, decision-making is centralised, whereas if the authority is delegated tothe lower organisation levels, it is decentralised.

Similarly, Mintzberg and Quinn (1996, p. 338) definedecentralisation as a diffusion of decision-making power. Ifdecision-making rests at one given point within anorganisation, it is considered to be a centralised organisation.If the decision-making responsibility is dispersed amongmany individuals, the organisation is considered to berelatively decentralised. This definition implies thatdecentralisation and centralisation are a matter of degreeand that full decentralisation, or centralisation, is not feasiblein practical terms. Horngren (1982, p. 630) claims that fullcentralisation is not economical, in most instances, as it canbe impossible to handle all information and make alldecisions at the top organisational levels.

According to Galbraith and Nathanson (1978, p. 5) astructure is defined as the:

segmentation of work into roles such as production,finance, marketing, and so on; the recombining of roles intodepartments or divisions around functions, products,regions, or markets; and the distribution of power acrossthis structure.Galbraith and Nathanson (1978, p. 5)

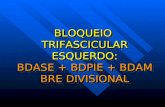

It is apparent from this definition that a structure can eitherbe functional or divisionalised. A functional structure can beachieved by dividing all of a firms activities of a similar typeinto a number of separate functional areas, such asproduction, finance and marketing. The managers of theseareas report directly to the chief executive. Figure 2.1(a)depicts a functional structure. In the figure, none of themanagers of the five departments is responsible for morethan one part of the process of acquiring the raw materials,converting them into finished products, selling to customers,and administering the financial aspects of this process. Theproduction department, for example, is responsible for themanufacture of all products, at a minimum cost and ofsatisfactory quality, and to meet the delivery dates requestedby the marketing department. The marketing department isresponsible for the total sales revenue and any costsassociated with selling and distributing the products but notfor the total profit. The purchasing department is responsiblefor purchasing supplies, at a minimum cost and ofsatisfactory quality, so that the production requirements canbe met. Revenues and costs (including the cost ofinvestments) are combined together only at the chiefexecutive or corporate level. This level is classified as aninvestment centre.

2. Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies

Divisional Performance Measurement 8

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies9

Figure 2.1 A Functional and Divisionalised Organisational Structure

IC = Investment centresCC = Cost centresRC = Revenue centre

(a) Functional Organisational Structure

(b) Divisionalised Organisational Structure

Financial and administration

manager(CC)

Marketingmanager

(RC)

Productionmanager

(CC)

Other functional managers

(CCs)

Purchasingmanager

(CC)

Research anddevelopment

manager(CC)

Chiefexecutive

(IC)

Product Ydivisionalmanager

(IC)

Product Xdivisionalmanager

(IC)

Other functional managers

(CCs)

Product Zdivisionalmanager

(IC)

Other functional managers

(CCs)

Other functional managers

(CCs)

Chiefexecutive

(IC)

-

A divisionalised structure involves the establishment ofseparate, semi-autonomous units (normally established onthe basis of either individual products/product groupings orgeographical regions) that are coupled together by a centraladministrative structure. The semi-autonomous units arecalled divisions or business units and the centraladministration relates to the central headquarters/headoffice. A divisionalised structure, which is divided intodivisions in accordance with the products that are made, isshown in Figure 2.1(b).

Generally, a divisionalised organisational structure results inthe decentralisation of the decision-making process.Divisional managers are normally free to set selling prices,choose what market to sell in, make product mix and outputdecisions, and select suppliers (this may include buying fromother divisions within the com-pany or from othercompanies). In a functional organisational, structure pricing,product mix and output decisions are normally made bycentral management. Consequently, the functional managersin a centralised organisation will have far less independencethan divisional managers. Divisional managers have profitresponsibility. They are responsible for generating revenues,controlling costs and earning a satisfactory return on thecapital invested in their operations. Managers within afunctional organisational structure do not have profitresponsibility. For example, in Figure 2.1(a), the productionmanager has no control over sources of supply, selling prices,or product mix and output decisions.

The creation of separate divisions may lead to the delegationof different degrees of authority; for example, in someorganisations a divisional manager may, in addition to havingauthority to make decisions on sources of supply and choiceof markets, also have responsibility for making capitalinvestment decisions. Where this situation occurs, thedivision is known as an investment centre. Alternatively,where a manager cannot control the investment or hasresponsibility for making only minor capital investmentdecisions and is responsible only for the profits obtainedfrom operating the fixed assets assigned to him or her bycorporate headquarters, the segment is referred to as a profitcentre.

In contrast, the term cost centre is used to describe aresponsibility centre in a functional organisational structurewhere a manager is responsible for costs but not profits. Thefinal category of responsibility centre is a revenue centre.These are responsibility centres where managers, such asregional sales managers, are only accountable for financialoutputs in the form of generating sales revenues.

It can be seen from Figure 2.1 that a further distinguishingfeature between a functional structure and divisionalisedstructure is that, in the functional structure, only theorganisation as a whole is an investment centre. Below thislevel, a functional structure applies throughout. Within adivisionalised structure, the organisation is divided intoseparate investment, or profit, centres and a functionalstructure applies below this level.

Many firms attempt to simulate a divisionalised profit centrestructure by creating separate manufacturing and marketingdivisions in which the supplying division produces a productand transfers it to the marketing division, which then sells theproduct in the external market. Transfer prices are assigned tothe products transferred between the divisions. This practicecreates pseudo-divisionalised profit centres. Separate profitscan be reported for each division, but the divisional managershave limited authority for sourcing and pricing decisions. Tomeet the true requirements of a divisionalised profit centre, adivision should be able to sell the majority of its output tooutside customers and should also be free to choose thesources of supply.

In 1980, Ezzamel and Hilton investigated the degree ofautonomy allowed divisional managers in 129 large UKcompanies. They found that divisional managers enjoyedsubstantial discretion in taking operating decisions relating tooutput, selling prices, setting credit terms, advertising andpurchasing policies. However, there was close supervision bytop management in choosing capital projects and specifyingcapital expenditures in the annual budget.

2.3 Factors Influencing the Emergence of DivisionalisedCompaniesAs this research is devoted to divisionalised companies, it isrelevant to discuss the factors influencing their emergence.The following sub-sections present the different argumentsrelating to the emergence of divisionalised companies. Thefirst section, Section 2.3.1, introduces Alfred D. ChandlersStrategy and Structure (1962). Chandlers argument is basedon the historical background of American corporations. Thesecond section introduces the work of Oliver E. Williamson,Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis of Antitrust Implications(1975). The third section, Section 2.3.3, discusses thecontingency theory literature.

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies 10

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies11

2.3.1 Strategy and structureChandler (1962) adopts a historical approach in examiningthe relationship between strategy and structure. His study isbased on a basic notion that structure follows strategy.Chandler defines strategy as:

the determination of the basic long-term goals andobjectives of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses ofaction and the allocation of resources necessary forcarrying out those goals(Chandler, 1962, p. 13).

He identifies three main strategies: horizontal, vertical anddiversification. A horizontal strategy implies growth inmarkets that may be local, national or multinational. Itproduces a unitary structure1. A vertical strategy includesabsorbing functions that are either backwards-looking(towards suppliers) or forward-looking (towards customers)and produces a functional structure. The final strategy can beachieved by diversification into products that are eitherrelated, or unrelated, to the current products, leading to theadoption of a multidivisional structure. Once a diversificationstrategy is adopted, a company becomes a co-ordinator ofmultiple product lines.

Chandler argues that the unitary structure was not a goodmechanism to control multiple products as it becamedifficult for top management to keep track of the diversifiedproduct lines. Firms attempted to deal with these strategyshifts within their administrative structures. When this failed,some changed, inventing the multidivisional structure. Adivisionalised structure was adopted by many Americancorporations, such as Du Pont Nemours & Co (Du Pont),General Motors Corporation (General Motors), Standard OilCompany (Standard) and Sears and Roebuck Company(Sears). Du Pont and General Motors began to fashion theirnew structure shortly after World War 1. Standard started itsreorganisation in 1925 and Sears in 1929. The companiesdeveloped their new structure independently of each other.Each company thought its problems were unique andrequired a tailor-made solution. The divisionalised structureprovided this and gradually became a model for similarchanges in many American companies.

Given that a diversification strategy leads to the adoption ofa divisionalised structure, Chandler examined the reasonsthat encouraged companies to diversify into related andunrelated products. He found that diversification in theUnited States was driven by accelerated urbanisation andtechnological change occurring shortly after the beginning ofthe 20th century that provided firms with an incentive todiversify and to adopt a multidivisional structure.

1 A unitary structure is defined as a group of functional divisions:sales, finance and manufacturing. Specialisation by function permitsboth economies of scale and an efficient division of labour to berealised. (Chandler, 1962, ch.1).

Furthermore, the nature of the industry and industrialtechnology determine, to some extent, the possibility ofadopting a divisionalised structure. Chandler argues thatfirms in certain industries are more likely to choosediversification strategies because those industries involvetechnologies that lead naturally to related or unrelatedproducts. Du Pont, for example, was a diversifiedmanufacturing company. It had begun to diversify intoproducts that utilised similar chemical technology. FromChandlers point of view, firms in electrical equipment,machinery, automobile and food industries are more likely toadopt diversification strategies, while firms in metal mining,steel making and petroleum are more likely to integratevertically. Many reasons for the rejection of the divisionalisedstructure in these companies are given:

the nature of these industries required a tightadministrative control that could be achieved bycentralised functional structure;

these industries made standardised products in largevolume for a well-defined market, so it was easy to planand control their activities using unitary or departmentalstructure; and

such industries used simple operations and there were nomajor technological and market changes.

The companies working in these industries found it easy todeal with operating decisions without adopting adivisionalised structure.

2.3.2 Markets and hierarchiesWilliamson (1981) developed a theory of the organisationsand markets that rests upon three general propositions:

bounded rationality (Simon, 1957); information impactedness; and opportunism.

Bounded rationality refers to human behaviour that isintentionally rational, but only limitedly so (Simon, 1961,p. xxiv). It suggests that human beings are quite limited in theamount of information they can receive, store, retrieve andprocess without error. Bounded rationality appears whenmanagers are suffering from information overload.

Information impactedness means that information is notuniversally distributed in an organisation, nor is it free.

Opportunism means that individuals may take actions basedon their own information and that these actions may be atthe expense of the organisation. Organisational membersmay, therefore, pursue goals which differ from those statedby top management, as well as manipulate and distortinformation.

-

Williamson argues that the continuous expansion of theunitary/functional structure creates a cumulative loss ofcontrol, which has internal efficiency consequences(Williamson, 1975, p. 133). As size increases, actors (ororganisers) reach their limits of control due to boundedrationality. Opportunism is, therefore, more likely to occurwithin the organisation and, consequently, organisationalefficiency and profitability are threatened. By adopting themultidivisional structure, the problems of control are resolvedand the continued growth of the organisation is possible.

In addition, Williamson (1975, Ch.8) argues that themultidivisional form (the M-form) exists to deal with bothbounded rationality and opportunism.

Operating decisions were no longer forced to the topmanagement but were resolved at the divisional level,which relieved the communication load-strategic decisionswere reserved for general office, which reduced partisanpolitical input into the resource allocation process. Theinternal auditing and control techniques, which the generaloffice had access to, served to overcome informationimpactedness conditions and permit fine tuning controls tobe exercised over the operating parts.(Williamson, 1975, pp. 137-138).

From this definition, it is apparent that top managementmake strategic decisions. Divisions, however, are delegatedthe authority to make operating decisions. This implies thatdetailed information will be available at divisional level andtop management will receive summarised financial reports.

Since operating decisions are made at divisional level, there isa possibility that divisional managers may pursue sub-goalsthat differ from those intended by top management. Thus,Williamson (1975) stresses the importance of internal controlat multidivisional companies. Such internal control involvesthree basic control tools:

manipulation, by the centre, of the incentives in terms ofsalary, bonuses, and promotion;

internal audits; and the centralisation of the cash flow allocation process.

Williamson argues that the most important control tool isthe cash flow process. He claims that cash earned bydivisions is pooled at the centre and reassigned to divisionsbased on the expected future yield as assessed by the centre.

The M-form structure, according to Williams, is likely toachieve a higher performance than the unitary structure. Heargues that some companies do not fully delegate todivisions the authority over operating decisions and the headoffice is extensively involved in operating issues. Therefore,the M-form hypothesis is only fully applied to thosecompanies that separate strategic and operating decisionsand that use internal control.

2.3.3 Contingent factorsAccording to contingency theory literature, the followingcontingent factors influence the adoption of a divisionalisedstructure:

diversification strategy. It was suggested, in Section 2.3.1that structure follows strategy and, in particular, thatdiversification leads to the adoption of an M-formstructure;

the size of the company. According to Mintzberg and Quinn(1996, p. 709), as companies become large, they tend todiversify and then divisionalise. There are three reasons forthis. Firstly, large companies tend to be risk averse anddiversification spreads such risk. Secondly, large companiescan dominate their market and, therefore, are likely todiscover growth opportunities elsewhere, throughdiversification and then divisionalisation. Finally, most ofthe giant companies reach their superior financialperformance by diversification, thus producing greaterpressure for further diversification;

the age of the firm. The effect of the age of the firm issimilar to that created by company size. According toMintzberg and Quinn (1996, p. 709), older firms tend todiversify and then divisionalise. This is because managers inolder companies sometimes look for new challengesbeyond the traditional markets, seeking diversion or changethrough diversification. In addition, as time passes, newcompetitors enter old markets, forcing the management tolook elsewhere for growth opportunities;

imitation. Many researchers (including DiMaggio andPowell, 1983 and Fligstein, 1985) argue that largeorganisations are likely to come to resemble one anotherand, therefore, the spread of multidivisional form is theresult of firms desire to emulate other successful firms;and

other factors. There are many researchers (Khandwalla,1974; Hill and Pickering, 1986; Mohoney, 1992) who arguethat there are other factors that influence the adoption ofan M-form structure: new acquisitions, decline in companyperformance, advice of management consultants,inter-organisational communication problems and thenature of the industry.

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies 12

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies13

2.4 The advantages and disadvantages of divisionalisationDrawing on organisational theory and empirical research,management accounting literature attributes manyadvantages and disadvantages to a divisionalised structure.Solomons (1965, Ch. 1) and Drury (2000, pp. 794-795) claimthat divisionalisation has to following advantages:

divisionalisation may improve decision-making byimproving the quality and speed of the decisions. Divisionalmanagers can make quicker decisions as they are moreclosely associated with the problem at hand and therequired information does not usually have to pass alongthe chain of command to, and from, top management;

the delegation of responsibility to divisional managersprovides them with greater freedom, thus making theiractivities more challenging and providing the opportunityto achieve self-fulfillment. This process should mean thatmotivation and efficiency will be increased, not just at thedivisional manager level, but throughout the wholeorganisation. According to Dittman and Ferris (1978), themanagers of profit centres should have greater jobsatisfaction than the managers of cost centres and quasi-cost centres. Studying 480 US companies, they found thatthe reported level of job satisfaction for profit centremanagers was significantly more than the level ofsatisfaction reported for cost and quasi-cost centremanagers. They recommend that, wherever possible,system designers should try to construct profit centres fororganisational units;

by delegating the responsibility of decision-making todivisions, top management will have more time to devoteto more important tasks (for example, strategic planning)since it will free them from detailed involvement inoperating decisions; and

a division can be used for training the future members oftop management by enabling trainee managers to acquirethe basic managerial skills and experience in anenvironment that is less complex than managing the wholecompany.

On the other hand, divisionalised companies may suffer fromthe following disadvantages:

there is a danger that, in divisionalised companies, divisionsmay compete with each other excessively and divisionalmanagers may be encouraged to take actions that willincrease their profits at the expense of the profits of otherdivisions. For example, situations can arise where thedivisional managers may sell their products outside of theorganisation rather than transferring them to otherdivisions. It may be cheaper for the company, as a whole,to transfer internally rather than the receiving divisionsbuying from the external market and the supplyingdivisions selling in the external market;

divisionalisation can cause many managerial problems.There is the possibility of loss of control by delegatingdecision-making to divisional managers. This problem canbe overcome by using a good performance evaluationsystem, together with appropriate control information; and

the cost of providing central activities may be lower thanthe cost of similar activities in non-divisionalisedcompanies. For instance, a large central accountingdepartment in a centralised company may be less costly tooperate than separate accounting departments for eachdivision within a divisionalised company.

2.5 The pre-requisites for successful divisionalisationCompanies adopting a divisionalised structure should havesome attributes to attain successful divisionalisation. Suchattributes have been discussed by Solomons (1965, p. 10).Solomons argues that the first attribute is that the activitiesof a division should be as independent as possible of otherdivisions activities. On the other hand, the independence ofdivisions from each other is a necessary condition fordivisionalisation. However, it should not be carried out up tothe limit, thereby destroying the idea that divisions are anintegral part of a single organisation. Instead, divisions shouldcontribute, not only to the success of the company, but alsoto the success of each other.

The second attribute is that there should be a co-ordinationmechanism to solve possible conflicts between divisions,including conflicts in determining transfer prices and therequirements of shared resources. Solomons claims that anaccounting system can play an essential role in solving anypossible conflict that may arise between divisions.

-

2.6 SummaryThis chapter has discussed the alternative forms oforganisational structure and described the different types ofresponsibility centres. In addition, factors influencing theadoption of a divisionalised structure were discussed.

The first factor was the relationship between strategy andstructure (Chandler, 1962). It was suggested thatdiversification strategy leads to the adoption of adivisionalised structure.

The second factor was that high transaction costs, boundedrationality and opportunistic behaviour lead to the adoptionof an M-form structure (Williamson, 1975). It wasemphasised that the M-form structure requires the:

allocation of operating decisions to divisional levels andstrategic decisions to top management level;

manipulation of the incentives by the centre; maintenance of an efficient internal audit; and concentration of cash flow allocation processes.

The remaining factors influencing the adoption of adivisionalised structure were derived from the contingencytheory literature.

It is widely recognised that, in pursuing a diversificationstrategy, the size and age of an organisation, and imitation ofsuccessful organisations, are important factors in theadoption/non-adoption of the M-form structure.

Empirical studies that have been undertaken provide mixedsupport of the contention that the M-form structureoutperforms the unitary structure. They suggest that thesuccessful adoption of the M-form structure is dependentupon maintaining appropriate control mechanisms andperformance measurement systems. The next chapter,therefore, focuses on the methods that are described inliterature for controlling and measuring divisionalperformance.

Divisional Performance Measurement Historical Background of Divisionalised Companies 14

-

Divisional Performance Measurement15

3.1 IntroductionThis chapter describes the different financial performancemeasures that are presented in management accountingliterature to evaluate divisional performance and provides asummary of the empirical studies relating to the usage ofthese measures. It begins with a discussion of the theoreticaldistinction between the economic and managerial divisionalperformance measures. This is followed by a brief summary ofthe limitations of traditional divisional financial measures anda description of two major innovations in the 1990s thatsought to overcome these limitations.

3.2 Distinguishing between divisional managerial andeconomic performanceTraditionally, literature has advocated that divisional financialperformance measurement should distinguish between theperformance of divisional mangers and the economicperformance of the divisional unit (Dearden, 1987; Drury,2000, p. 796). To evaluate the economic performance ofdivisions, corporate management requires a periodicreporting system providing attention-directing information.Such attention-directing information highlights thosedivisions that require more detailed studies to examine theireconomic viability and ways of improving their futureperformance. If the purpose is to evaluate the performance ofdivisional managers, only those items that are controllable, orinfluenced by the divisional manager, should be included inthe performance measure.

The need to distinguish between divisional managerial andeconomic performance leads to three different profitmeasures divisional controllable profit, divisionalcontribution to corporate sustaining costs and profits anddivisional net income.

Divisional controllable profit is advocated for evaluatingdivisional managerial performance because it includes onlythose revenues and expenses that are controllable orinfluenced by divisional managers. Thus, the impact of itemssuch as foreign exchange rate fluctuations and the allocationof central administrative expenses may be excluded on thegrounds that managers cannot influence them. However,such expenses may be relevant for evaluating a divisionseconomic performance.

Those non-controllable expenses that are estimated to beavoidable in the event of divisional divestment are deductedfrom controllable profit to derive the divisional contributionto corporate sustaining costs. Examples of such expensesinclude the allocation of those corporate joint resourcesshared by divisions that fluctuate according to the demandfor them. Assuming that cause-and-effect allocations can beestablished that provide a reasonable approximation of thecost of joint resources consumed by a division, then theallocated cost can provide an approximation of avoidablecosts. Thus, the divisional contribution to corporate sustainingcosts and profits is appropriate for measuring divisionaleconomic performance since as its name implies it aimsto provide an approximation of a divisions contribution tocorporate profits and unallocated corporate sustainingoverheads.

Divisional net income is an alternative measure for evaluatingdivisional economic performance. It includes the allocation ofall costs. From a theoretical point of view, this measure isdifficult to justify, since it includes arbitrary apportionmentsof those corporate sustaining costs that are likely to beunavoidable unless there is a dramatic change in the scaleand scope of the activities of the whole group. The mainjustification for using this measure is that corporatemanagement may wish to compare a divisions economicperformance with that of comparable firms operating in thesame industry. The divisional contribution to corporatesustaining costs and profits is likely to be unsuitable for thispurpose. This is because divisional profits are likely to beoverstated due to the fact that, if they were independent,they would have to incur some of the corporate sustainingcosts. The apportioned corporate sustaining costs thereforerepresent an approximation of the costs that the divisionwould have to incur if it traded as a separate company.Consequently, companies may prefer to use divisional netprofit when comparing the performance of a division withsimilar companies.

To compare the financial performance of different companiesor divisions, a profitability measure is required that takes intoaccount the differing levels of investment in assets. Return oninvestment (ROI) meets this need by acting as a commonratio denominator for comparing the percentage returns oninvestments of different sizes in dissimilar businesses, such asother divisions within the group and outside competitors. Ithas become established as the most widely used singlesummary measure of financial performance. According toJohnson and Kaplan (1987), it was developed by Du Point inthe early 1900s and since then it has become widely used byoutsiders to evaluate company performance. Its majorbenefit is that it provides a useful overall approximation ofthe success of a firms past investment policy by providing asummary measure of the ex post return on capital invested. Afurther attraction of ROI is that it is a flexible measure. Thenumerator and denominator can include all or just a subset of the line items that appear on corporate financialstatements. It can be adapted to measure managerialperformance by expressing controllable profit as a percentageof controllable investment.

3. Divisional Performance Measures

-

It is more appropriate, however, to use ROI for evaluating theeconomic performance of a division than managerialperformance, since controllable profit and assets are notreported in external published financial statements.Therefore, it is impossible to compare divisional controllableprofit as a percentage of controllable assets with similarcompanies outside of the group. For comparing the economicperformance of a division, net income is likely to be thepreferred profit measure to be used as the numerator tocompute ROI, to ensure consistency with the measures thatare derived from the financial reports of similar companiesoutside of the group.

Return on investment (ROI) has a major weakness if used toevaluate divisional managerial performance: the measuremay encourage divisional managers to maximize the ratio,which can lead to suboptimal decisions. For example, amanager heading a division that is currently earning a 30 percent ROI might be reluctant to accept an investment projectyielding a 25 per cent return, as this would dilute thedivisions ROI. However, if the companys (and the divisions)cost of capital is 15 per cent, the project is likely to yield apositive net present value and ought to be accepted.Alternatively if the divisional existing ROI was 10 per cent,acceptance of a project expected to yield a return of 13 percent would increase the existing ROI, even though its returnis less than the cost of capital.

In order to overcome the problems attributed to the use ofROI, textbooks recommend that residual income should beused to evaluate divisional managerial performance.Controllable residual income involves deducting fromcontrollable profit a cost of capital charge on the investmentcontrollable by the divisional manager. The main argumentfor advocating the use of residual income is that it increasesthe likelihood of divisional managers investing in projects ifthey have positive net present values (NPV). Returning to thefirst example, and assuming an investment of 10 million,estimated residual income will increase by 1 million (2.5million profit, less 1.5 million cost of capital charge) if theproject is accepted. In the second example, acceptance of theproject will result in an estimated decline in residual incomeof 0.2 million (1.3 million to 1.5 million). A furtheradvantage of residual income over ROI is that it is moreflexible, since different costs of capital can be applied toinvestments that have different levels of risk. In other words,the residual income measure enables different risk-adjustedcapital costs to be incorporated into the computation. Bycontrast, ROI cannot easily incorporate these differences.

Residual income does not appear to be widely used inpractice. In the USA, Mauriel and Anthony (1966) reportedthat only 7 per cent of companies participating in theirresearch relied solely on residual income. Similarly, Reece andCool (1978) reported that 2 per cent of the companies intheir research pool used only residual income. In the UK,Scapens et al (1982) reported that 37 per cent of respondentcompanies used residual income, whereas the Australian/NewZealand study by Skinner (1990) reported only 7 per centusage. By contrast, ROI was widely used. In the USA, Maurieland Anthony (1966) and Reece and Cool (1978) reportedthat 60 per cent, and 65 per cent, of respondend companiesused ROI, respectively.

Previous studies indicate that companies tend to use ROI inorder to make inter-division and inter-firm comparisons(Reece and Cool, 1978; Skinner, 1990). Since ROI is a ratio, itcan be used to compare the attained ROI between divisionswithin a given company or with other divisions, whereas anabsolute monetary measure is not appropriate for makingsuch comparisons. In addition, outsiders tend to use ROI as ameasure of a companys overall performance. Corporatemanagers may therefore want their divisional managers tofocus on ROI in order to make their performance measurecongruent with outsiders measure of the companys overallperformance.

A major weakness of the above studies is that they make noattempt to distinguish between whether the performancemeasures were used to evaluate either divisional economic ormanagerial performance, or whether the same reportedmeasure was used for both purposes.

3.3 Limitations of financial performance measuresFinancial performance measures are generally based onshort-term measurement periods and this can encouragemanagers to become short-term oriented. For example,relying on short-term measurement periods may encouragemanagers to reject positive NPV investments that have aninitial adverse impact on the divisional performance measurebut have high payoffs in later periods. Financial performancemeasures are also lagging indicators (Eccles and Pyburn;1992, p. 41). They determine the outcomes of managementsactions after a period of time. Therefore, it is difficult toestablish a relationship between managers actions and thereported financial results. Financial performance measures arealso subject to the limitation that they deal with only thecurrent reporting period, whereas managerial performancemeasures should focus on future results that can be expectedbecause of present actions. Ideally, divisional performanceshould be evaluated on the basis of economic income byestimating future cash flows and discounting them to theirpresent value. This calculation could be made for a division atthe beginning and the end of a measurement period. Thedifference between the beginning and end values representsthe estimate of economic income. The main problem withusing estimates of economic income to evaluate performanceis that it lacks precision and objectivity and that the bestestimates of future outcomes are likely to be derived fromdivisional managers.

Divisional Performance Measurement 16

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Divisional Performance Measures17

According to Johnson and Kaplan (1987), companies tend torely on financial accounting-based information for internalperformance measurement. This information may beappropriate for external reporting but it is questionable forinternal performance measurement and evaluation. Themajor problem is that profit measures derived form usingGAAP are based on the historical cost concept and thus tendto be poor estimates of economic performance. In particular,using GAAP requires that discretionary expenses are treatedas period costs, resulting in managers having to bear the fullcost in the period in which they are incurred.

A possible reason for the use of GAAP for divisionalperformance evaluation is to ensure that performancemeasures are consistent with external financial accountinginformation that is used by financial markets to evaluate theperformance of the company as a whole. This may arisebecause of the preference of corporate management fordivisional managers to focus on the same financial reportingmeasures.

Given the problems associated with the use of financialperformance measures, two possible methods of dealing withthem emerged in the early 1990s. The first seeks to improvefinancial performance measures and the second incorporatesnon-financial performance measures with financialperformance measures. These methods are discussed in thefollowing sections.

3.4 Improving financial performance measures: economicvalue added (EVA)During the early 1990s, Stern Stewart and Co (SternStewart), a New York-based consulting firm, repackaged andrefined residual income in the form of economic valueadded (EVA). The objective of EVA is to develop aperformance measure that accounts for the ways in whichcorporate value can be added or lost. Thus, by linkingdivisional performance to EVA, managers are motivated tofocus on increasing shareholder value.

The EVA concept extends the traditional residual incomemeasure by incorporating adjustments to the divisionalfinancial performance measure for distortions introduced byGAAP. Economic valued added(EVA) can be defined as thefollowing.

EVA = conventional divisional profit accountingadjustments cost of capital charge on divisional assets

Adjustments are made to the chosen conventional divisionalprofit measure (for example, controllable profit, net income)in order to replace historic accounting data with a measurethat approximates economic profit and asset values. SternStewart has stated that it has developed approximately 160accounting adjustments that may need to be made toconvert the conventional accounting profit into a soundmeasure of EVA, but it has indicated that most organisationswill only need to use about ten of the adjustments. Theseadjustments result in the capitalisation of many discretionaryexpenditures such as research and development, marketingand advertising by spreading these costs over the periods inwhich the benefits are received. Also, by taking into accountall the capital costs, EVA attempts to show the amount ofwealth a business created or destroyed in each period.

According to Young (1999), adjustments aim to:

produce EVA figures that are closest to cash flow and,therefore, less subject to the distortions and bias arisingfrom accrual accounting;

avoid the arbitrary distinction between investments intangible assets (which tend to be capitalised) andintangible assets (which tend to be written off as incurred)arising from the application of the conservatism principle;

prevent the amortisation, or write-off, of goodwill; bring off balance sheet debt (finance) into the balance

sheet as is the case when assets are subject to leasing; and correct for the bias associated with accounting

depreciation.

Biddle et al (1998) investigated the extent of EVA usage inthe USA.

Economic value added, or EVA, has become a newbuzzword in the corporate movement towards emphasizingshareholder value. Displaying a pattern familiar forcorporate fads, EVA citations have grown exponentiallyfrom a handful in 1993 to more than 300 in 1997. Fortunemagazine has touted EVA as the real key to creatingwealth, a new way to find bargains, and since 1993 haspublished an annual Performance 1000 issue featuringEVA.(Biddle et al, 1998, p. 60).

McConville (1994) reported that AT&T and Coca-Cola areusing EVA. Similarly, McTaggaret et al (1994), Chen and Dodd(1997) and Copeland et al (1996) found that many Americanand British companies used EVA, or similar measuressuggested by their consulting firms. Otley (1999) claims thatthere is a relationship between the extent to which the stockmarket is strong and the adoption of EVA. He demonstratesthat EVA is accepted in countries that have strong stockmarkets, such as USA and the UK. In countries with weakstock markets, it is less likely that EVA will be adopted.

-

Research has also been undertaken to discover whethercompanies that adopt EVA achieve a higher performancethan companies that do not. For example, Tully (1999)reports the results of the study undertaken by Stern Stewart.The study measured the stock performance of 67 clients(adopters of EVA) over the first five years of their use of EVA.The results indicated that adopters of EVA achieved a higherperformance than their ten closest competitor companies.Although much research has been undertaken relating toEVA, little evidence is available relating to the extent that it isused to measure and evaluate divisional performance.

3.5 Integrating financial and non-financial measuresTo mitigate against the dysfunctional consequences that canarise from relying excessively on financial measures,management accounting literature advocated many yearsago (for example, Solomons, 1965) that these should besupplemented with non-financial ones that measure thosefactors critical to the long-term success and profits of theorganisation. These measures focus on areas such ascompetitiveness, product leadership, productivity, quality,delivery performance, innovation and flexibility in respondingto changes in demand. If managers focus excessively on theshort-term, the benefits from improved short-term financialperformance may be counter-balanced by a deterioration innon-financial measures. Such non-financial measures shouldprovide a broad indication of the contribution of a divisionalmanagers current actions to the long-term success of theorganisation.

Two major problems arise with the use of non-financialmeasures, however. Firstly, which of a vast number ofmeasures should be selected as key measures to be includedin the performance reports to evaluate divisionalperformance? Secondly, confusion arises when measuresconflict with each other, resulting in it being possible toenhance one measure at the expense of another. Accordingto Kaplan and Norton (2001), previous systems thatincorporated non-financial measurements used ad hoccollections of such measures more like checklists ofmeasures for managers to keep track of and improve, thana comprehensive system of linked measurements.

The need to integrate financial and non-financial measures ofperformance and identify key performance measures that linkmeasurements to strategy led to the emergence of thebalanced scorecard. The balanced scorecard aims to providean integrated set of performance measures derived from thecompanys strategy that gives top management a fast butcomprehensive view of the organisational unit. The balancedscorecard was devised by Kaplan and Norton (1992) andrefined in later publications (Kaplan and Norton, 1993, 1996,2001).

The balanced scorecard philosophy assumes that anorganisationss vision and strategy is best achieved when theorganisation is viewed from the following four perspectives:

customer perspective (How do customers see us?); internal business perspective (What must we excel at?); learning and growth perspective (Can we continue to

improve and create value?); and financial perspective (How do we look to shareholders?).

The balanced scorecard involves establishing major objectivesfor each of the four perspectives and translating eachobjective into specific performance measures. Kaplan andNorton recommend targets be established for eachperformance measure. For feedback reporting, actualperformance measures can also be added. In order tominimise information overload and avoid a proliferation ofperformance measures, the number of measures used foreach of the four perspectives should be limited to criticalmeasures.

A crucial assumption of the balanced scorecard is that eachperformance measure is part of a cause-and-effectrelationship involving a link from strategy formulation tofinancial outcomes. Measures of organisational learning andgrowth are assumed to be the drivers of the internal businessprocesses. The measures of these processes are, in turn,assumed to be the drivers of measures of customerperspective, while these measures are the driver of thefinancial perspective. The assumption that there is a cause-and-effect relationship is necessary because it allows themeasurements relating to non-financial perspectives to beused to predict future financial performance.

The balanced scorecard thus consists of two types ofperformance measures. The first consists of lagging measures.These are the financial (outcome) measures within thefinancial perspective that are the results of past actions.Mostly, these measures do not incorporate the effect ofdecisions when they are made. Instead, they show thefinancial impact of the decisions as their impact materialises.This can be long after the decisions were made. The secondtype of performance measure is leading measures that arethe drivers of future financial performance. These are thenon-financial measures relating to the customer, internalbusiness process and learning and growth perspectives.

Divisional Performance Measurement Divisional Performance Measures 18

-

Divisional Performance Measurement Divisional Performance Measures19

The balanced scorecard has also been subject to frequentcriticism. Most criticism questions the assumption of thecause-and-effect relationship on the grounds that it is tooambiguous and lacks a theoretical underpinning or empiricalsupport. The empirical studies that have been undertakenhave failed to provide evidence on the underlying linkagesbetween non-financial data and future financial performance(American Accounting Association Financial AccountingStandards Committee, 2002). Other criticism relates to theomission of important perspectives, the most notable beingthe environmental/impact on society perspective and anemployee perspective, although there is nothing to preventcompanies adding additional perspectives to meet their ownrequirements.