Tame of Thrones: Kehinde Wiley Plays it Safe at the ... · Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A ... in her...

Transcript of Tame of Thrones: Kehinde Wiley Plays it Safe at the ... · Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A ... in her...

BlouinArtInfo

Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum 10 March 2015 Chloe Wyma

Tame of Thrones: Kehinde Wiley Plays it Safe at the Brooklyn Museum

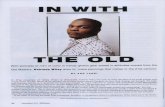

A detail of Kehinde Wiley's "Femme piquée par un serpent," 2008.

(Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York/© Kehinde Wiley)

Since the mid-aughts, Kehinde Wiley has achieved Napoleonic fame for his monumental

paintings depicting young men of color in contemporary streetwear in poses derived from

European courtly portraiture. By unseating the saints and noblemen of Rubens,

Fragonard, and Velazquez and replacing them with handsome, anonymous young men

cast from the streets of Brooklyn, Dakkar, and Beijing, Wiley — curator Eugenie Tsai writes

in her introductory catalog essay for the artist’s mid-career survey at the Brooklyn

Museum — “subverts canonical art history” by making visible its erasure of black bodies.

Nevertheless, the exhibition, titled “A New Republic,” feels more safe than subversive. The

agglomeration of Wiley’s neo-baroque portraits of young black dandies posing against

botanical filigrees doesn’t disturb our way of seeing the world so much as feed our

contemporary taste for promiscuous juxtaposition and nobrow pastiche.

BlouinArtInfo

Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum 10 March 2015 Chloe Wyma

Despite some nice surprises — six full-length portraits in stained glass, a series of bronze

busts, a lovely group of intimately scaled altarpieces inspired by the 15th-century

Netherlandish painter Hans Memling — “A New Republic” is dominated by Wiley’s tested

and approved format of beefy, large-scale portraiture citing the grand history of European

oil painting. “Equestrian Portrait of the Count Duke Olivares,” 2005, for instance, is

adapted from Velasquez’s 1634 portrait of Gaspar de Guzmán, a prominent Spanish

courtier and politician during the reign of Philip IV. A black man in his 20s, wearing a red

hoodie and wielding a golden lance, assumes the count’s position atop a rearing white

stallion. The sliver of Arcadian landscape in the immediate foreground gives way to one of

Wiley’s conventional faux-brocade backdrops, this one ornamented with golden tendrils

against a royal blue ground. Another crowd-pleaser is the delectably kitschy, almost

Koonsian portrait of Michael Jackson, commissioned by the late King of Pop in 2008.

Pictured in full armor, Jackson rides a beribboned show pony, attended by an entourage

of naked cherubim hovering overhead.

At their best, Wiley’s portraits, such as the billboard-sized “Femme Pique par un Serpent,”

transcend shellacked hauteur and exude homoerotic male beauty. In that particular work,

inspired by Auguste Clesinger’s 1847 sculpture of a writhing female nude in death throes

from a snakebite, Wiley simultaneously queers and racializes the sublimated perversity of

19th-century academic statuary, replacing the pallid marble female nude with a reclining

black man in low-slug jeans and a green hoodie. Here, the black male body, still an object

of anxiety and presumed criminality in American culture, lies on a divan, gazing at the

viewer like a coy odalisque. Compared to this steamy display of inverted exoticism and

epicene genderfuckery, Wiley’s recent, stately paintings of black women, modeling

couture gowns designed by Givenchy’s Riccardo Tisci, feel perfunctory and over-branded,

less a series of portraits of individuals than a product of luxury cross-promotion.

“A New Republic” is an emphatically visual, generous show that will likely appeal to a

broad range of museumgoers beyond your typical (mostly white) Chelsea-crawling art

crowd; and this is indisputably a good thing. Nevertheless, for work that deals with race

and the politics of representation, Wiley’s feels rather anodyne. For the most part, his

celebratory, affirmative paintings of people of color don’t challenge or implicate the white

viewer, nor do they cast a critical eye on contemporary race politics. The object of Wiley’s

BlouinArtInfo

Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum 10 March 2015 Chloe Wyma

critique — the lilywhite demographics of early modern European portraiture — is too

distant, too historical, to have much of a purchase on current conversations about race in

America.

Wiley’s signature mashup of European heraldry and hip-hop swagger, art historian

Connie H. Choi writes in her catalog essay, employs “a multiplicity of cultural signifiers to

challenge the status quo.” On the contrary, what’s striking about Wiley’s work isn’t how it

places itself in opposition to some nebulous “status quo,” but how it participates in

mainstream popular culture, mapping neatly onto a politically ambivalent rhetoric of

black royalism that functions as an aspirational symbol for empowerment but belies the

everyday experiences of the vast majority of African Americans living in a society still

structured by racial injustice. From Beyoncé’s coronation as “Queen Bey” to Kanye West

and Jay Z’s noblesse-obsessed collaborative album “Watch the Throne,” metaphors of

nobility in mainstream hip-hop function as an expedient shorthand for the luxuriant

exceptionalism and conspicuous wealth once reserved for European aristocracy (Lorde’s

woozy 2013 hit “Royals” has been widely read as a critique of consumerist fantasy in Top-

40 hip-hop, albeit from the patronizing perspective of a white teenager from New

Zealand). To be clear, it’s the exhibition literature, not the artist, that’s attempting to frame

Wiley’s painting as an oppositional cultural practice. Wiley’s work isn’t activist art, nor

does it pretend to be: “As an artist and a student of history,” he told New York magazine,

“you have to be at once critical and complicit… It’s about pointing to empire and control

and domination and misogyny and all those social ills in the work, but it’s not necessarily

taking a position. Oftentimes it’s actually embodying it.”

Wiley’s gesture of inserting black subjects into the canon of Western painting is less a

radical appropriation of European pictorial conventions than a progressive but ultimately

soft postmodern mash-up of art historical quotations. Moreover, beyond the works’

schticky conceptual formula, there’s something subtlety condescending — or at least

viscerally irritating — about the fact that, in so much of his work (with the notable

exception of his globe-trotting “World Stage” series), the heroism of Wiley’s subjects

remains contingent upon analogies to a princely European past. In fact, perhaps the best

work in “A New Republic” dispenses with art historical trappings altogether: 2006’s

“Mugshot Study,” a modest, relatively unassuming portrait of an anonymous young black

BlouinArtInfo

Review: ‘Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic’ at the Brooklyn Museum 10 March 2015 Chloe Wyma

man pictured in a wanted poster the artist came across in Harlem. Eschewing the pompier

bombast of much of the work on view, the painting cogently addresses the criminal justice

system’s vilification and trivialization of black lives, “repatriating” his image, as the

cultural critic Touré put it in the show’s catalog, from “the plantation of criminal

expectations.” This pared-down work might not have the commercial appeal of Wiley’s

blockbuster paintings, but it may be a generative place for an established artist to begin

anew.