systems research For Better health - Altarum...

Transcript of systems research For Better health - Altarum...

Value-Based Pharmaceutical Purchasing: What Do We Know About What Works?How can pharmacy benefits be designed to increase quality and control costs for employers and consumers? What are the primary strategies for doing so?

Gloria N. Eldridge, PhD, MSc

Holly Korda, PhD, MA

Megan Shaheen, MPH

altarum instituteissue BrieFJanuary 2011

systems research For Better health

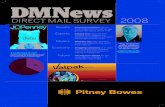

Hospital care31%

Physician/Clinicalservices

21%

Dental services4%

Prescrip�on drugs10%

Nursing home6%

Home health care3%

Remaining personal

health care8%

Other health spending

17%

altarum instituteissue BrieFJanuary 2011

systems research For Better health www.altarum.org

Value-Based Pharmaceutical Purchasing: What Do We Know About What Works?How can pharmacy benefits be designed to increase value and lower costs for employers and consumers? What are the primary strategies for doing so?

aLTaruM InSTITuTE 2

ISSuE

Prescription drug costs represent a

significant portion of the billions spent

by employers each year on health care for

their employees: $259 billion, which is

10% of total u.s. health spending in 2010.

employers concerned with addressing rising

health benefits costs face difficult decisions

about how to balance pharmacy benefits

in the context of the overall health benefit

package. some strategies attempt to restrict

consumers’ use of specific products to

reduce pharmacy and overall health benefits

costs. others use options that may increase

pharmacy costs but improve value because

increased adherence to drug regimens can

reduce expensive inpatient hospitalizations,

readmissions, or emergency department

visits. still other strategies provide guidance

or restrictions on product selection in the

search for value.

altarum Institute researchers conducted an environmental scan and found three major areas of value-based pharmaceutical purchasing in-novation: generic substitution, incentive-based formularies, and value-based insurance design (VBID). Increasing or decreasing co-payments and co-insurance is an important consumer lever used either alone or in concert with these three strategies.

Health Spending by Category, September 2010

Total u.S. Health Spending = $2.59 trillionSource: altarum monthly national Health Expenditure estimates.

Pharmacy Benefits: Carve In or Carve Out?

Employers can use several approaches to providing and administer-ing pharmaceutical benefits. These can be carved out of the health insurance plan administered separately by third party pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), or they can be integrated within the larger health benefit structure. Health benefit managers, or their PBMs, can also use

aLTaruM InSTITuTE 3

systems research For Better health www.altarum.org

Summary of Pharmacy Benefit Management Op�ons That Work Approach Summary

Generic subs�tu�on provides consumers with the generic equivalent of brand-name medica�ons. Purchasers o�en use this approach to save money by giving incen�ves to use generic rather than brand-name medica�ons.

Most studies show generic subs�tu�on to be effec�ve in reducing pharmacy benefit costs for consumers as well as purchasers. One study found that if a generic had been subs�tuted for all corresponding brand-name outpa�ent drugs in 2000, the median annual savings in drug expenditures per person would have been $45.89 for adults younger than 65 years of age and $78.05 for adults at least 65 years of age. In these age groups, the na�onal savings would have been approximately $5.9 billion and $2.9 billion, respec�vely, represen�ng approximately 11% of drug expenditures.1

Incen�ve-based formularies (mul�-�er formularies) are designed to curb the increasing costs of prescrip�on drugs by providing financial incen�ves (i.e., lower copayments) for enrollees to choose drugs that the payer prefers. Payers some�mes use this approach to promote certain products over others. Ideally, criteria for placing drugs in different �ers should be based on clinical outcomes, not on the cost of ingredients and manufacturer rebates. If not, then the costs of pharmaceu�cals may decrease, but overall medical costs may increase.2 Value-based insurance design can be used to address this issue.

Several studies have found that the adop�on of an incen�ve-based formulary and the accompanying changes in copayments resulted in lower aggregate u�liza�on of and spending on drugs.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 However, most of the savings go to health insurance plans, not to consumers.10 There is greater spending by pa�ents.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Evidence regarding effects on u�liza�on and consumer health spending are mixed.

Value Based Insurance Design (VBID), also known as Value Based Benefit Design seeks to increase value in health care through insurance design and incen�ves. One version of VBID reduces or eliminates cost sharing for services that have strong evidence of clinical benefit. Another version increases cost sharing for services that do not show evidence of clinical benefit.17 Cost-sharing provisions of VBID address the problem of overconsump�on of health services in the absence of a consumer having a financial stake due to insurance coverage.

Evidence regarding VBID is limited but increasing as purchasers gain experience with this approach. The Pitney Bowes examples highlighted here provide addi�onal evidence.

What We Know About What Works

Many studies have been conducted on the effect on consumer behavior of the use of generic substitution, copayments and coinsurance, and incentive-based formularies. There are few published studies of value-based insurance design beyond those on the benefits designs of Pitney Bowes. The table on this page reviews the existing evidence.

a number of strategies to seek value as part of their overall health benefits offerings. For example, PBMs can use such strategies as disease management; utilization management, such as drug utilization review or prior authorization; delivery system, such as use of mail order pharmacies; or benefit design strategies and consumer cost-sharing.

The evidence is mixed as to whether integrated or carved out models are most effective. While administrative costs are increased by carving out pharmacy costs, the pharmacy benefits manager concentrates on ways to lower costs in pharmaceuticals. PBMs, as market specialists, can negoti-ate better prices with drug companies. For larger companies, this can result in substantial savings in pharmaceutical costs. at the same time, the PBM’s decisions may not be taking into account the effects of decisions on pharmaceutical benefits in light of overall value of health care. also, for self-insured companies, carving out the pharmaceutical benefit means they are not covered under protections established to limit expenses. For smaller companies, the added administrative burden of dealing with another vendor may make the carve-out option difficult, especially if full benefit analyses are to be conducted.

as health care systems become more integrated, improved data systems will enhance understand-ing of prescription drug costs and the effects of pharmacy benefit changes in the larger context of overall benefits costs. Data systems that enable review of both pharmacy and health services claims are important for objective assessment of overall benefits costs.

aLTaruM InSTITuTE 4

systems research For Better health www.altarum.org

Coinsurance and copayments can be used in concert with generic substitution and are important levers in both incentive-based formularies and value-based insurance design. These are cost-sharing arrangements that require consumers to bear at least some cost, encouraging them to select cost-effective medications. Coinsurance rates keep pace with rising drug costs and ensure that the consumer has some financial stake in choice of medication. If coinsurance is so high that the consumer will not adhere to prescribed drug regimens, overall medical costs may increase. Lower cost sharing results in greater prescription drug use. Higher levels of cost sharing result in reductions in prescription drug use.19, 20, 21, 22 Several studies have found that increased cost sharing has detrimental effects on patient’s health.23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 However, these studies were not necessarily testing value-based insurance design. Modest increases in prescription copayments have been shown to have a negative impact on consumers’ medication purchasing decisions. These increases may lead to pill splitting or other reduced-dosing methods, increased time between refills, and increased medication discontinuation, particularly for symptomatic medications, but also for classes of prescription medications used for long-term disease prevention.29

In addition to these benefit design options, a number of innovative tools are available to support drug adherence. For example, computerized, real-time alerts offer consumers, physicians, and pharmacists an array of prompts and reminders of refills and alerts about medicines with potential contraindications and therapeutic alternatives. This approach is useful if consumers and providers are attuned to personal digital assistants (PDas), email, and other new technologies.

The Pitney Bowes CaseTo implement its value based insurance design, Pitney Bowes shifted all diabetes drugs and devices from tier 2 or 3 formulary status to tier 1. Over the next year, overall direct healthcare costs per plan participant with diabetes decreased by 6%. In addition, the rate of increase in overall per-plan participant health costs at Pitney Bowes has slowed markedly, with net per-plan participant costs in 2003 at about $4,000 per year versus $6,500 for the industry benchmark. In all of Pitney Bowes’ self-funded plans and a few of the others, drug benefits are provided by a separate pharmacy benefit manager. This coverage of approximately 90% of all employees under one common pharmaceutical plan provides a potentially powerful single point of entry for studying—and improving—long-term disease outcomes in the Pitney Bowes population.

another Pitney Bowes effort eliminated copayments for cholesterol-lowering statins and reduced them for a blood clot inhibitor called clopidogrel. The change resulted in an immediate 2.8 percent increase in adherence to statins relative to controls and, for clopidogrel, a 4 percentage point difference in the adherence rate between intervention and control patients a year later.

Sources: (Mahoney, 2005)30; (Choudry, et al., 2010)31

The Carespeak Communications and Mount Sinai Hospital CaseCarespeak Communications and Mount Sinai Hospital teamed up on a program to send regular reminders to pediatric liver transplant patients (ranging in age from 1 to 27) or their caregivers via two-way text message. Follow-up alerts are sent to caregivers of those who do not respond within a predetermined time range. Physicians also proactively monitor performance and then send motivational messages to encourage continued adherence, or else they identify and intervene with non-adherent patients before the risk of rejection increases.32 The program increased adherence to medication regimens and significantly reduced the risk of organ rejection.33, 34

systems research For Better health www.altarum.org

Missionaltarum serves the public good by solving

complex systems problems to improve

human health, integrating research,

technology, analysis, and consulting skills.

Visionaltarum Institute demonstrates and

is sought for leadership in identifying,

understanding, and solving critical systems

issues that impact the health of diverse

and changing populations. altarum is

acknowledged as a valued, collaborative,

and collegial institute of the utmost

competence and integrity.

EVIDENCE FOR ACTION

Pharmacy benefit management is not a “one size fits all” proposition. •Integrated benefits models or carve outs, and any combination of approaches, incentives, and tools can be used to create value for pur-chasers. Importantly, pharmacy benefit value should be assessed in the context of the health benefit package overall. Integrated benefits data and reporting systems facilitate this assessment.

return on investment (rOI) is difficult to calculate given that it is dif-•ficult to quantify and attribute directly to value based pharmaceutical policy. However, some employers may see cost savings from value-based pharmaceutical purchasing reflected in reduced absenteeism and “presenteeism” (when employees are at work but not productive).

Purchasers can use PBMs to administer their prescription drug ben-•efits—but the evidence on whether PBMs result in savings is mixed. Some studies report significant savings generated through the PBM, while others do not.

Multi-tiered formularies can be tricky to implement. Selection criteria •should be based on clinical outcomes to ensure that the costs of pharmaceuticals does not decrease at the expense of rising medical costs.

Outside of a VBID framework, there is evidence that increasing cost •sharing may lead to pill splitting or other reduced-dosing methods, increased time between refills, and increased medication discontinu-ation. Several studies have found that increased cost sharing has detrimental effects on patient’s health. In addition, this may lead to increases in overall health care costs for an employer.

Changing pharmaceutical benefits may change not only pharma-•ceutical, but also overall health benefit costs. Considering one set of claims data, either pharmaceutical or health plan claims, in isolation from the other set will lead to misleading findings.

Carve-outs for pharmaceutical benefits, as in the Pitney Bowes case •example, can leverage value in pharmaceutical benefit design for larger groups of the covered population.

Given high turnover, some employers are reluctant to use value-•based insurance design concepts because the investment may not pay dividends in the medium to long term if employees exit a firm.

Computerized, real-time alerts only work with patients and caregiv-•ers who are computer or technology savvy and willing to receive information in this format.

altarum institute integrates objective research and client-centered consulting skills to deliver comprehensive, systems-based solutions that improve health and health care. a nonprofit serving clients in the public and private sectors, altarum employs more than 350 individuals and is headquartered in ann arbor, Michigan with additional offices in the Washington, DC area; Sacramento, California; atlanta, Georgia; Portland, Maine; and San antonio, Texas.

aLTaruM InSTITuTE 5

This issue brief is part of a series on value-based purchasing prepared by researchers in the Systems research and Initiatives Group at altarum Institute. It highlights summary findings of environmental scans and evidence reviews completed in December 2010 to identify and assess “what works” to improve value in health care purchasing and health system performance. For more information: www.altarum.org or contact Gloria n. Eldridge, PhD, MSc at [email protected].

systems research For Better health www.altarum.org

15 Landon, B. E., rosenthal, M. B., normand, S.-L. T., Spettell, C., Lessler, a., underwood, H. r., et al. (2007). Incentive formularies and changes in prescription drug spending. American Journal of Managed Care, 13 Part 2, 360-369.16 Huskamp, H. a., Deverka, P. a., Epstein, a. M., Epstein, r. S., McGuigan, K. a., Muriel, a. C., et al. (2005). Impact of 3-tier formularies on drug treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 435-441.17 Fendrick, a. M., Smith, D. G., & Chernew, M. E. (2010). applying value-based insurance design to low-value health services. Health Affairs, 29, 2017-2021.18 Leibowitz, a. W., Manning, W., & newhouse, J. P. (1985). The demand for prescription drugs as a function of cost-sharing. Social Science & Medicine, 21, 1063-1069.19 Smith, D. G., & Kirking, D. (1992). Impact of consumer fees on drug utilization. Pharmacoeconomics, 2, 335-342.20 Lexchin, J. H., & Grootendorst, P. (2004). Effects of prescription drug user fees on drug and health services use and on health status in vulnerable populations: a systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Health Services, 34, 101-122.21 Pauly, M. V. (2004). Medicare drug coverage and moral hazard. Health Affairs, 23, 113-122.22 Op. cit., Leibowitz, a. W., Manning, W., & newhouse, J. P. (1985).23 Goldman, D. P., Joyce, G. F., Escarce, J. J., Pace, J. E., Solomon, M. D., Laouri, M., et al. (2004). Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291, 2344-2350.24 Goldman, D. P., Joyce, G. F., & Karaca-Mandic, P. (January, 2006). Varying pharmacy benefits with clinical status: The case of cholesterol-lowering therapy. American Journal of Managed Care, 12, 21-28.25 Joyce, G. F., Escarce, J. J., Solomon, M. D., & Goldman, D. P. (2002). Employer drug benefit plans and spending on prescription drugs. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 1733-9.26 Joyce, G. F., Goldman, D. P., Karaca-Mandic, P., & Zheng, y. (2007). Pharmacy benefit caps and the chronically ill. Health Affairs, 26, 1333-1344.27 Joyce, G. F., Goldman, D. P., Vogt, W. B., Sun, E., & Jena, a. B. (august, 2009). Medicare Part D after 2 years. American Journal of Managed Care, 15, 536-544.28 Solomon, M. D., Goldman, D. P., Joyce, G. F., & Escarce, J. J. (2009). Cost sharing and the initiation of drug therapy for the chronically ill. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169, 740-748.29 Op. cit., Landsman, P. B., yu, W., Liu, X., Teutsch, S. M., & Berger, M. L. (2005). 30 Mahoney, J. J. (2005). reducing patient drug acquisition costs can lower diabetes health claims. American Journal of Managed Care, 11, S170-176.31 Choudry, n. K., Fischer, M. a., avorn, J., Sebastian Schneeweiss, D. H., Berman, C., Jan, S., et al. (2010). at Pitney Bowes, value-based insurance design cut copayments and increased drug adherence. Health Affairs, 29, 1995-2001.32 aHrQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. (n.d.). Regular reminders via text message increase adherence to medication regimen, significantly reduce risk of organ rejection in pediatric liver transplant patients. retrieved July 28, 2010, from www.innovations.ahrq.gov: http://www.innovations.ahrq.gov/content.aspx?id=270533 Miloh, T., annunziato, r., arnon, r., Warshaw, J., Parkar, S., Suchy, F. J., et al. (2009). Improved adherence and outcomes for pediatric liver transplant recipients by using text messaging. Pediatrics, 124, e844-850.34 Op. cit., aHrQ Health Care Innovations Exchange. (n.d.).

1 Haas, J. S., Phillips, K. a., Gerstenberger, E. P., & Seger, a. C. (2005). Potential savings from substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 1997-2000. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142, 891-897.2 ranD Health research Highlights of Joyce et al. (2002). Cost Sharing Cuts Employers’ Drug Spending—but Employees Don’t Get the Savings. http://www.rc.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/2005/rB4553.pdf.3 Blumenthal, D., Herdman, r., & Eds. (2000). Description and Analysis of the VA National Formulary. Washington, DC: national academy Press.4 Motheral, B., & Fairman, K. a. (2001). Effect of three-tier prescription copay on pharmaceutical and other medical utilization. Medical Care, 39, 1293-1304.5 Motheral, B. r., & Henderson, r. (1999/2000). The effect of a closed formulary on prescription drug use and costs. Inquiry, 36, 481-491.6 Huskamp, H. a., Epstein, a. M., & Blumenthal, D. (2003). The impact of a national prescription drug formulary on prices, market share, and spending: Lessons for Medicare? Health Affairs, 22, 149-158.7 Horn, S. D., Sharkey, P. D., & Phillips-Harris, C. (1998). Formulary limitations and the elderly; results from the Managed Care Outcomes project. American Journal of Managed Care, 4, 1105-1113.8 Joyce, G. F., Escarce, J. J., Solomon, M. D., & Goldman, D. P. (2002). Employer drug benefit plans and spending on prescription drugs. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, Erratum, 2409.9 Thomas, C. P., Wallack, S. S., Lee, S., & ritter, G. a. (2002). Impact of health plan design and management on retirees’ prescription drug use and spending. Health Affairs, Web First, W408.10 Op. cit., ranD Health research Highlights of Joyce et al. (2002).11 Op. cit., Motheral, B., & Fairman, K. a. (2001).12 Fairman, K. a., Motheral, B. r., & Henderson, r. (2003). retrospective, long-term follow-up of the effect of a three-tier prescription drug copayment system on pharmaceutical and other medical utilization and costs. Clinical Therapeutics, 25, 12.13 Huskamp, H. a., Deverka, P. a., Epstein, a. M., Epstein, r. S., McGuigan, K. a., & Frank, r. G. (2003). The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 2224-2232.14 Landsman, P. B., yu, W., Liu, X., Teutsch, S. M., & Berger, M. L. (2005). Impact of 3-tier pharmacy benefit design and increased consumer cost-sharing on drug utilization. American Journal of Managed Care, 11, 621-628.

020411

aLTaruM InSTITuTE 6