Summary - University of Manchester

Transcript of Summary - University of Manchester

132

TRANSFERRING ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING THEORY ACROSS CULTURAL BOUNDARIES

David I. Wilson*

and

Ahmed Ghoneim**

Department of Marketing Colleac? of Business Administration The Pennsylvania State? University

University Park, PA 16802

*Professor of Marketing and Administrative Director of the Institute for the Study of Business Markets.

-*-*Dactaral Student and AT>si <~>tant Lecturer, Cario University.

Summary

This paper reports on a complex, descriptive, and general model of. Egyptian organizational buying behavior. The model evolved from an exploratory study of buying process in th« Egyptian industrial public sector. A second issue is the discussion of the transferabi1ity of theories of organizational buying behavior across cultural and country boundaries. The development of broad theory is an important step in internationalization of industrial marketing.

Specifically the paper compares and contrasts current literature? and the Egyptian model. The major modification*-, to "Western" buying behavior theory to jccomodati* the Egyptian situation are noted.

133

As the' world continues to shrink scholars are becoming more attuned to the need to examine the? transfer of theory across international boundaries. It -sterns reasonable to conclude that there is not "A Theory of Organizational buying behavior, but rather, a basic set of theories that with modification will meet the needs of most situations. This conference is an important step in the direction o-f developing an understanding o-f the problems in building international industrial marketing theory that can be transfered between countries.

Like products, theory has to be modified to meet local circumstances as it moves internationally. This paper examines the processes of adapting a theory as it moves from one? culture to a very dissimilar culture. In particular, the transfer of fundamental concepts such as the buying center and the buygrid from a United States context to an Eygptian context is described. Some general comments on theory transfer conclude the paper.

The Problem

The new open-door economic policy of the Egyptian government encourages foreign investment and provides a favorable and attractive investment climate for Western business firms. Unfortunately, there are few studies available to guide business people in serving this market. The primary problem addressed in this paper is the development of a model of the Egyptian organizational buying process that would be helpful to someone attempting to understand Egyptian public sector campani es.

* A secondary objective was to explore the transferabi1ity oforganizational theory from one culture to another. The transfer of theory across international boundaries is obviously related to many variables such as nulturo, economics, business organization and government policies. A review of the literature of cross cultural studies found that most studies where either intracountry or international studies of countries having a high correspondence on the critical variables of culture, economic and political environment (1). Many of the studies were theory -free and basically described the buying process. Several studies did have a simple buying stage process models underlying thorn.

The IMP Project Group study is a major attempt to develop a new theoretical approach to international marketing and purchasing of goods based upon four groups o-f variables that describe and influence the interaction between buying and Jt-jlling companies,. This model while interesting and challenging did not hcwy th«3 specificity thai would bo useful in adapting a model to the Egyptian buying process.

134

The first stt'p was to identify apuropr L atv? theories uf organizational buvinq beh.-Avior that may parallel the buying situation in the Egyptian public sector. A number of i-.hcj^e models are discussed in the nex t -section. Append!.:: A provide?* background on thu-? Egyptian public nectar, comparing op pr.-.it ion and selected comments on cultural variables which provide useful background for model understanding.

Complex Models o-f Organizational Buying

Over the years a number o-f models have been developed in an attempt to describe the organizational buying process. These models have combined both task and non-task vari tables in an attempt to address the ccmplexities o-f the process. A listing o-f the models that have been identified as "complex" aro in Fi qure 1.

The basic concepts of thr? BUYGRID model have reasonable ace'? p t a n c;3 within the U.S. a c a d e m i c c o m m u n 11 y a n d h a v o b«.? a n incorporated into the MATD1JY and Supplier Choice Model-5. These three models deal with a structured buying process, a buying phase concept and permit analysis o-f a buying center or buying committee process all of which are relevant to the transfer of theory to the Egyptian situation. These models will be discussed in some detail.

the BUYGRID Model

Industrial buying is conceptualized as a process taking place over time rather than as a simple choice process. Many researchers (2) have distinguished stages or phases through which the decision passes in a chronological order.

In an early attempt to model the industrial buying process, Webster (3) identified four stages: problem recognition, buying responsibility, search and choice. Webster's model generated interest in the concept of phases in the buying process. Robinson, Fans and Wind (4) expanded that four-stage model to an eight-stage model and combined it with Faris's (5) three types of purchase situations then came up with the BUYGRID model.

The existence and duration of each of these eight phases depends upon the buying situation. In a new-task situation all phases supposedly exist and are extensive, whereas in a straight-rebuy situation phases are supposedly quickly passed through and some of them may be skipped.

The BUYGRID mod^l is "virtually devoid of predictive ability and offers little insights into the nature of the complex interplay between task and nantask variables. It does not permit inferences about behavioral causc-and-effect

135

re?lationr>hips of thr? kind needed tor designing efficient marketing strategies" (6).

Drspite these flaws, the? model is widely accepted. It has a I'in motivated researchers to work on the.? cone opt of phases ot the buying process.

The MATBUY Model

Mailer (7) developed a comprehensive conceptual model of production material buying (MATBUY) behavior in the following way:

1. De-fining the general process (and the stages) o-f production material buying.

2. Assessing the? different decision making points in the process where policy decisions (implying potential organizational conflict situations) arc taken.

3. Assessing the ways in which the vendor selection (a key subprocess) can be carried out.

4. Defining the principal personal, organizational, and situational or contextual variables having an effect on the production material buying process especially policy decision points and vendor selection (8).

Mailer divided the production material buying process into flight phases:

A - Purchase Initiation

B - Evaluation Criteria Formation

C - Information Search

D - Supplier DeT-inition for RFQ' s

£ - Evaluation of Quotations

F - Negotiations

G - Supplier Choice

H - Choice Implementation

Hi thin -jach of these; phases ho discussed decisions, individual s / dap # r t mean t <-:., an d p r ab i urn . i / t a * k -3 i n vo 1 vc?d .

136

'U though the? MATBUY model tried to be 30 comprehensive that i t c' D v u r -3 cane s p t u a 11 y .^J_l_ t h e? p r i n c i p ,.\ I decision p r o b 1 e m s ..AIV! conflict -situations, it has thu fallowing flawy:

1. It is devoid o-f predictive validity and empirical ral i ab i 1 i ty. Consequent I y , it has 1 i tt I o berv_> f 1.1 for marketing strr\tr:gi '.->ts.

::. Unlike the BUYGRID modal, it did not combine its phases with the different buying situations.

Supplier Choice Model

While the BUYGRID and MATBUY models are basically conceptual, the Supplier Choice model (9) is based on an empirical study of purchasing in si:; U.S. firms. The major' objective of the? study was to identify decision rulc?s th<? buying center members use during the supplipr choice process. The Supplier Choice modtfl is based on a decision process model consisting of a finitf? series of steps in the form of highly simplified rules. The result is a series of process flow models that describe in detail the rules that guide each step of the doci sion model.

Vyas and Woodside (10) found that during the earlier stages in the choice process, the buyer employed noncompensatory, conjunctive rules to eliminate unworthy candidates. Later in the process the price became a predominant criterion, when additional candidates were eliminated by using disjunctive decision rule.

This model was an important input into the development of the Egyptian model.

The Buying Center Concept

In their case study, Cyert, Simon and Trow (11) introduced the first citation recognising that not only the purchasing agent and his staff, but also a number of other managers in the firm are involved in the buying decision.

The term "buying center" was, for the first time, used by Robinson, Fans and Wind (12). After reporting the findings of several studies, they concluded that the buying influence is widely diffused among several persons and departments in the buying firm.

One? year lator, Weigand (13) suggested that studying the- purchasing agwnt only is not enough. He concluded that thr-> industrial buying function is complex and involves many poop To (with vastly different views) at all Invols in the firm.

137

Brand (14) used the term "decision-mating unit," Dunean (15) u ;,c?d tho tt?rm "organ i.-. .it i onal doc i si on unit," but thoy arc still in the same direction try to strops the multi-person nature? at- the buying decision and the importance of studying it from this perspective.

In 1978 the buying center concept captured the attention and interest of many of the industrial buying behavior scholars (16). In his endeavor to do-fine the buying center boundaries, Wind (17) raised the following questions: direct vs. indirect involvement, roles vs. people, individuals vs. group characteristics, temporary vs. permanent buying center, single vs. multiple decisions, patterns of formation and change, and whether or not outsiders should be included in the buying center definition.

A good definition of the buying center is that of Spekman (18) who defines it as "the informal organization subunit, composed of individuals from several functional departments, speci f i c£*l I y charged with making purchasing related decisions relative to a particular commodity or class of commodities."

The buying center concept again has good acceptance in the U.S. and seemed to be important in the Egyptian situation. Hence, it was an important concept in developing a model of the Egyptian organizational buying process.

Transfering the Theory

One basic building block is the buying center concept. In Egypt it is not difficult to define the buying centor or to identify its members as it is formal 1y defined bv thu organization. It is called the "buying committee." The buying committee is not on the organisation chart of the? company but its members are pre-appointed by the president of the company. He selects representatives from the major concerned departments (purchasing, production, financial and sometimes the legal affairs departments). This committne is created prior to any buying decision. It differs from the general concept of buying center in literature which states that the conposition of buying center is a function of the buying situation. Buying committee studies and recommends, but does not make the final decisions. Committee's recommendations are subject to the sanction of tha appropriate authority according to the pre-set financial 1 i in i t -.i .

The? Egyptian model framework drawr, heavily upon the BUYfiRID, MATBUY and th,-? Supplier Choice Models. ft ..< I l-.'mut^ I: a P:: pi ore? buying ph.-v.^s, r.x?r sun /d e.'p, \rtmen t. «n,, t o«,;l-: s/,xr 11 v i I i' "-., decision rules and criteria thah arc? ^mploym-j in Egypt)an

138

or nan i z a i: i on x I buy i ng, The r esu J. t i s .A gun or n I i - «d -f I ow chart a-f the? Egyptian Public 'sector buying pro<:c":,«j.

n-u> first .-it^p W<J <-, ta prepare? a rough outline or a model u :-, i. n G the? s1 r u c t ur r> of the U.S. mod o 1 r,. Th ; <:> «. j t r uc t . i r a n^ryud ar, a guide to the exploratory -field work. [n addition to personal observation, data were collected in two ways; analysis of company buying constitutions and other purchasing documents and indepth interviews with buying committee members as identified by the purchasing manager. Data were collected on buying phases, persons/departments, tasks/activities, decision rules and criteria that are employed in the buying process. As a validity choc!::, data obtained from one member were checked with other members of the buying committee. The sample was limited to five public sector companies, one from each of the five industrial sectors.

The Model

As in the U.S. models the process is triggered by the establishment of a buying need. Once this need or problem is recognized a multi-part process is initiated. Th«e first step is assessing the degree of newness of the need. If it is not new, the user will be able to fill a purchase request which will detail the required specifications, quantity and the date by which the purchased itern(s) are required. The purchase request is then sent to purchasing department for processi ng.

Processing depends upon the urgency of the request. If it i.-3 not urgent, the purchasing department will invite? potential suppliers to bid. The manner of bidding invitation is different according to the dollar value of the purchase.

Open tenders are used when the dollar value is largo and there are many potential suppliers' who are not known to purchasing department or when the purchasing department wants to induce new suppliers to bid. In the open tender situation the purchasing department puts an advertisement in the two most popular daily newspapers at least twice, ten days before the closing date. Few details are in this advertisement. It i « an open invitation to all possible supppliers giving them general information about the tender and the specific closing date. Detailed specifications are kept in the purchasing department where interested suppliers or their agents may obtain these details upon paying a fee.

[f the dollar value is moderate and there are a fewer but known suppliers, the purchasing department will contact thum directly (RFC!) inviting them to bid. This is called a 1 irni ted tender.

139

Bt?fore the closing date the purchasing department may receive suppliers' wax-sealed guotations which are kept in a special box. On the specified closing date, at 12:OO noon, an ad hoc committee opens the tt?nders in -front of all participant suppliers or their agents. The seals are broken and the quotations are read aloud. The data -for each bidder is them transferred to a spread sheet. Samples, if any, are sent to the laboratory for inspection. Before the buying committee meeting the purchasing department converts all prices to a common comparable base.

The buying committee simultaneously compares all quotations using the noncompensatory, conjunctive decision rule. They usually start by comparing quality. Any quotation with unacceptable quality, i.e., does not meet the company standards is rejected. The remaining suppliers' offering are examined further- The buying committee continues these comparisons until they arrive at a price, eliminating suppliers who do not meet the minimum standards on the attribute list, which is the last and decisive factor. The supplier quotation which meets all the other criteria and has the lowest price is recommended to the next level of authority. The committee reports this recommendation to the appropriate managerial authority for final approval.

Returning to the beginning of the flow chart. If the problem is new and the accurate specifications can not be determined and described, the company may, if it is possible, buy A small quantity of the product to test it. If not, they may contact or visit potential suppliers or invite their representatives for discussion with their counterparts in the buying company. By this stage, if the need is not urgent, it will be processed through the tender method as mentioned above.

If the need is moderately urgent, the dollar value is not too large, and quite a few public-sector suppliers available thun a negotiation committee will sequentially invite or visit possible suppliers and conduct direct negotiation. Tins committee procedures are less structured than the buying committee but generally fallows the same procedures and use the same criteria. After selecting the.1 supplier (s) the committee reports to the appropriate authority for final approval.

At last, in all exceptional cases, i.e., when the need is very urgent, price is not negotiable, only one supplier is available and the? dollar value is small, a direct order is awarded to the solo supplier. One purchasing agent may place the order and then report to the appropriate authority for approval .

140

Discussion

A comparison between Vyas and Woodside's (19) model and the Egyptian model resulted in the following key difference's:

t. Vyas and Woods!de pointed out that purchasing agents do not discuss the preparation of purchase requisitions with members o-f other departments. On the contrary, Egyptian purchasing departments extensively discuss purchase requests with users to make sure that speci f icat i ons are clearly described be-fore any further processing.

2. Users in Egypt are not officially required to suggest names of potential suppliers in their purchase requests unless they are asked for it by the purchasing department. This is to minimize the negative effects of friendship between suppliers and users who can describe the required specificahioins in such a way that the specifications can only bo met by their friends. According to Vyas and Woodside names of potential suppliers are suggested by users on their purchase requests.

3. The first phase of Vyas and Woodside's model is selecting those suppliers who will receive the requests for quotations. In Egypt there is no prior selection; rather, all possible suppliers are invited to bid.

Vyas and Woodside mentioned that none of thecompanies that they studied used a formal vendor rating system. In Egypt all buying processes are structured and regulated. Buying constitution formally states all the decision criteria and the decision rules. This process is to minimise the influence of subjective factors.

Unlike Vyas and Woodside's model, after receivingquotati ons change the evaluation negotiated

no supplier data of his process is

if the best

is asked or permitted toquotation. Only after the

completed are pricesquality supplier has the

highest price.

In contrast to the U.S., Egyptian buyers do notinform the ex plicitly the buyer quotation deci si on.

rejected suppliers. Moreover, it is written in the tender advertisement that has the right to accept or reject any with no obligation to justify his

141

According to Was and Wood side if only one acceptable bid i * r e c i? i v e d , the b u y o r •:* t .* r t «., "tactful negotiation" wit.h 1. he bidder who i«.-, usually LI r i ,.i w a r- o a i ^ h c f a <: t. t h a t. h is q u o t a t1 o n i s t h o o n J y one received by the-? buyer. In Egypt because* all the w<£ix-<r,<?al cd quotations are opened and read aloud in front. o-f all participating suppliers or their agents, a sole bidder is always aware o-f this fact.

Transfer o-f Theory

The model developed in this paper supports the general concept that organizational buying theory can be transferred across cultures. The major modifications of the model were accomodatiuns of cultural and organizational influences. Tha literature review cited earlier only found one multi-national study of buying behavior (the IMP Project Group, 19(32). The? homoqeniety of the sample nations does not lead us to explore problems of theory transfer. It it?em«.b that each group of scholars read their own set of literature arid develop theory appropriate to theiT own needs. Major influences in this gap of mutual interest seem to be distance, language and different philosophies of science. Conferences such as this help to close the gap by bringing together scholars with mutual interests and shared goals. Theory transfer will evolve as more researchers attempt to test their theory across multiple national and cultural situations.

142

Appendix A

Organization of Egyptian Industry and Buying Process

Organization of Egyptian Industry

The? output of Egyptian industry is split between th<j public and the private sectors. The public sector is so predominant in that it produces more than 757. of the total industrial production.

The public sector firm tends to be the? larger one in the? Egyptian economy. The? private sector consists of many small enterprises whereas the public sector consists of a fiaw large companies. For instance, tn the Egypti'an textile industry l-.herc? ar» more than 650 small private factories bu<- only JO 1 ar gc? pub I i c compan i es.

There? are 112 companies in the Egyptian industrial public sr?ctor. They are classified, according to the last: annual report of the ministry of industry, by the type of industry as foilows:

1. Textile Industry 30 companies2. Chemical Industry 233. Metal Industry 334. Food Industry 215. Mining Industry _5 "

TOTAL 112

Th(?^e companies are und^r the control of the ministry of industry and comprise the "public-sector industry." Thus, the t;?rm "public-sector industry" d»Tfin» r; industrial companies under the control of the ministery of industry. Although there are other industrial activities under the control of other ministries, this definition is practical, clear cut and has been used in all Egyptian studies to date.

Studies have concentrated on the public-sector industry rather than the private sector for the following reasons:

1. The public sector is the predominant: (produces 75V.).

2. T t i s more? organized and has more? capable? personnel.

3. Data art? relatively available* and trustworthy-

143

4. Tht-> r t-?l. .-U. i ve ease? o-f obtai. nina data once? the.jipproval r;)f thr> Cnntral ttar»ncy o-f Mob i. 1 i .: <.\t i an .ind/-"U ', > h i. --;t ; <--, ird 1. r-.-jt h-:r -, a « introduction from thein i IT i. > 1: r y o f i n d i.t -.s I: r v ar e i. :> \i(.it?d .

The -following chart present's thr? general organizational structure o-f the public-doctor industry.

Minister o-f Industry

Highor Counci1 of

Textile Sector

Hi ghorCounci 1 o-fChe?mi caiSector

Hi gher Counci 1 o-f

Msh.-il SPCtor

HighcrCounciI of

FoodSector

HigherCounc i 1 o-f

M i n J. n c;Ge?ctor

1 Board of Directors of Company "X 1

President o-f Company "X"

Buying Organization and Buying Committee

This section discusses the? organization o-F buying activities in Egyptian companies. Because the buying committee plays a paramount role in buying process in Egyptian companies, a brie-f discussion o-f buying center concept as related to the Egyptian buying committee -follows.

In a typical Egyptian industrial company, the purchasing department could -be represented on the company organization

chart as follows:

144

President

General Manager of Commercial Affairs

I

Purchasing Marketi ng

Local Purchases

While local purchases department deals with local market, imports department deals with foreign markets and hence has different problems such as money transfer, letters of credits, and foreign currency problems.

If there is a common product needed that has to be imparted and it is used by more than one company, the company which uses the major share of that item imports it for all other companies. The buying committee will consist of a representative from each company. This pooling of purchasing orders is to gain the economies of large scale buying.

Four buying methods are used: direct order, direct negotiation, limited tender, and open tender. Direct order i-s used when the company has only am.» purchase alternative. The order is placed directly with the sole source of supply. Direct negotiation is u.^ecJ whun the company has a few alternatives all within the public sector. There 1,1 no need for the long tender procedures ar, each potent laJ source? i-. wp?ll known. When the timing of the? purchase is not that

j ers are known to the buyer they (RFD)

tender as it is limited to known of the purchase,

large, according to tender

urgent and potentialare contacted personally

total value

d-inl i mi ted) will be used.

T h i D i -7, call ed t h e 11 m i t ed suppliers and limited in the

If the total value at the known -financial limit'., open

The unlimited tender meansany supplier anywhere in the world may submit a tender.

Every company has pro-set financial limits which determine the buying method that should be used. Although throe limits

trom onr? company to another and tram one --.oct.ar to thr?y ar-n WeH known, and documented. Each company'^

d i 1 -f or mother

145

purch.-iso pol ici-vr, cloarly describe these limits.

Social Influence

Social groups ar>-? perceived as :* men, -is of sharing responsibilities more? than sharing acti vi tins. If anything --.hould go wrong, responsibility will he diffused among all members and no one can be held responsible. That diffusion of responsibility can be explained by the large number of committees: "higher committees, " "central committees" and "supreme committees" that are found in Egyptian organizations. Fraternal organizations as they exist in U.S.A. are not common in Egypt. Egyptians in general are friendly so, it is not necessary to be a member in fraternal social organizations to be able to socialize. Social relationships are still quite strong within family structure and within the whole society.

The family authoritarian pattern carries ovc?r in ho business organizations. Committees, though numerous, do not make decisions. Their recommendations arr? subject to the top management approval .

Values

Egyptians highly value friendship. Friendship plays a paramount role in an Egyptian's life. The impact of this norm of friendship is substantial. One's time is not his own as friends have their rights to an individual's tim»-?. It is common for an Egyptian to change his schedule if one of his fric?nds needs him for any reason at any time. The norm i«s that one should not let a friend down: rather, one should look out for a friends' interests exactly as he expects his friends to guard his own interest. Friendship is valued more than money. It gives an Egyptian more satisfaction to spend time with friends than to earn more money. Friendship is an important force in business. People in power at all levels are partial to friends and their friends' friends. So, everyone strives to build friendship "networks" and enlarge them.

The religious values, brotherhood, and friendship leads Egyptians to value generosity towards their guests. Moslem teachings say "your guest i£ the guest of God;" therefore, one will be rewarded from God for generosity now and hereafter. Egyptians are in general poor, yet paradoxically in entertaining, they are extravagantly generous.

According to Islamic rules, ono must hold firm trj his commitments. God will hold him responsible for his word. Edward Hall (In Kassar j i an and Robert son (20)) said: "in the Arab world, once a man's word is given in * particular kind of way, it is just as binding, if not more so, than most of

146

our ujritton contracts. The? written contract, there*ore?, vioJatec; the Moslem's sensitivities and re-fleets on his honor."

Egyptians conception of time is different. In rural areas farmers do not care about time as they have plenty of it. Due to the seasonal nature of their work, farmers work only 160 days a year. They are not in a hurry, always relaxed this is the "agricultural behavior." In citirjs people schedule their time but never stick to their schedules as friendship demands cause schedule changes.

In business, making a decision usually takes much timt? as a result of the long chain of required sanctions and the larqe number of committees and higher, central, and supreme committees. In business meetings, people of higher status usually come late because it is not appropriate for them to wait for lower status people, especially since they are not sure that everyone will come on time and it is difficult for them to keep their time schedule. Higher statue, people da not v\jait in linos to do any job. Their own jobs an-3 always done far them. Egypt may be the only country where people? go to their friends' offices to visit just social visits. Others who come for business have to wait as a result.

147

Figure 1

Complex Model of Organizational Buying Behavior in Chronological Order

1. BUYGRID Modal (Robinson, Paris and Wind 1967)

2. COMPACT Model (Robinson and Stidsen 1967)

3. Simulation Model (Wind and Robinson 1968)

4. Information Processing Model (Howard and Morgenroth 1968)

5. Organizational Buying Behavior Model (Webster and Wind 1972)

c. Industrial Buyer Behavior Model (Sheth 1973)

7. Dyadic Paradigm (Bonoma, Bagozzi and Zaltman 1975)

S. Organizational Interaction Model (Hakanssen and Ostberg 1975)

9. Industrial Buying Task Group Model (Spekman 1977)

10. Industrial Market Response Model (Cho-f-fray and Li lien 197G)

11. Communication Network Dyadic Systems Model (Johnston 1979)

12. MATI?UY Model (Moller 1981)

13. Supplier Choice Model (Vyas and Woodsid« 1984)

148

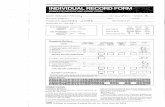

The BUYGRID Model

BUYGRID Model BUYCLASSES

New Task

Mudi f ied Rebuy

Straight Rebuy

Anticipation or recognition of a problem (need).

Determination of character istics and quantity of needed i tern.

Description o-f characteristics and quantity o-f needed item.

Search for and qualification of potential sources.

Acquisition and analysis of proposals.

Evaluation of proposals and selection of supplier(s).

Selection of an order routine.

Performance feedback and '. j v-U uat i on .

149

References and Notes

Brad lay. M. F.

Davig, W.

Hakansson, H. Wootz, B.

R-rvr?, R. and Johansen, E

Sarin, S.

Woodside, A., Karpati, T and Kakarigi , D.

Webster, F-

Ozanne, M. and Churchi11, G.

Brand, G.

Buying Behavior in Ireland s Public Soctor, Industrial Marketing Management, 6,1977, pp. 25J-250.

Industrial E'uying Behavior in Brazil, Industrial Marketing Management, 9, 1900, pp. 273-230.

A Framework o-f Industrial Buying and Selling, Indus trial Marketing Management, 9, 1979, pp. 28-39.

Organizational Buying in the Offshore Oil [ndu^try, Industrial Marketing Manage ment, 11, 1982, pp. 275-282.

Buying Decisions in Four Indian Organizations, Industrial Marketing Manage ment, 11, 1982, pp. 25-37.

Organizational Buying in Selected Yugoslav Firms, Industrial Marketing Manage ment, 7, 1978, pp. 391-395.

Modeling tho Industri.,-..; Buying Process, Journal o-f Marketing Research, November, 1965, pp. 370-376.

Five Dimensions o-f the Indus trial Adaption Process, Journal o-f Marketing Research, August, 1971, pp. 222 227«

The Industrial Buying Decision, Wiley, NY, 1972.

150

4.

Qzanne, M. and Churchill, A.

Brand, G.

Robinson, P., Paris, C and Wind, Y.

5. Ibid.

6. Webster, F. and Wind, Y

7- holler, K.

8. Ibid., p. 11.

9. Vyas, N. and Wcodside, A.

10. Ibid.

11. Cyert, R., Simon, H. and Trow, D,

12. Robinson, P., Paris, C and Wind, Y.

Modeling tho Industrial Buying Process, Journal of Marketing Research, November, 1965, pp. 370-376.

Five Dimensions o-f the Indus trial Adaption Process, Journal o-f Marketing Research, August, 1971, PL.O O O **> O '7±*~~. *.*- f *

The Industrial Buying Decision, Wiley, NY, 1972.

Industrial Buying and Crea tive Marketing, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA, 1967.

Organizational Buying Be havior, Prentice-Hall, Wood Cliffs, NJ, 1972.

Industrial Buying Behavior of Production Material, TheHelsinki School of Economics, Helsinki, 1981.

An Inductive Model o-f Indus trial Supplier Choice? Process, Journal of Marketing, Winter, 1984, pp. 30-45.

Observation o-f a Business Decision, Journal of Business, 29, October, 1956, pp. 237-238.

Industrial Buying and Crea tive Marketing, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA, 1967.

151

IT-. Wrai q.imd , R.

14. Webster, F.

Qzanne, "M. and Churchi11, G.

Why Studying th'? Purchasing Agent is Not Enough, Journal o-f Marketing, January, I960, pp. 41-45.

Modeling the Industrial Buying Process, Journal o-f Marketing Research, Ncvember, 1965, pp. 370-376.

Five Dimensions o-f the In dustrial Adaption Process, Journal o-f Marketing Research, August, 1971, pp .

3.

Brand, G.

Dun can, R

16. Wind, Y.

Spekman, R

Bagozzi, R

17- Wind, Y.

The Industrial Buying Decision, Wiley, NY, 1972.

Characteristics o-f Organisa tional Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty, Administrative Science Quarterly, September, 1972, pp. 313-327.

The Boundaries o-f Buy~ing Decision Centers, Journal o-f Purchasing and Material Management, Summer, 1978, pp. 23-29.

A Macro-Sociological Exam ination o-f the Industrial Buying Center, American Marketing Association Con-ference Proceedings, 1978, pp. 111-115.

Exchange and Decision Process in the Buying Center, in Zaltman, G. and Bonoma, T. (eds. ), Organizational Buying Behavior, American Marketing Association, 1978, pp. 100-125.

The Boundaries o-f Buying Decision Centers, Journal o-f Purchasing and Material Management, Summer, 1978, pp.

Spekman, R

Bagozz i, R.

152

A Macro-Sociological Exam ination of the Industrial Bu v i ng Ct:»n t «r , Amer i can Marketing Association Confer ence Proceedings, 1978, pp. 111-115.

Exchange and Decision Process in the Buying Center, in Zaltman, G. and Bonoma, T. (eds.) , Organizational Buying Behavior, American Marketing Association, 1978, pp. 1CO-

18. Spekman, R.

19. Vyas, N. and Woodside, A

20. Kassarjian, H. and Robertson, T.

An Alternative Framework for Explaining the Industrial Buying Process, in Zaltman, G- and Bonoma, T. (eds.), Organizational Buying Be havior, American Marketing Association, 1978, pp. 84-90.

An Inductive Model o-f Industrial Supplier Choice Process, Journal of Mar keting, Winter, 1984, pp. 30-45.

Perspectives in Consumer Behavior, Scott, Foresman and Company, IL, 1981.