STUDY: STUDY OF SHATTERED RED TILES WITH OLD...

Transcript of STUDY: STUDY OF SHATTERED RED TILES WITH OLD...

STUDY IS THE GENERIC NAME for a series of focused case-studies of works from the collection. It

involves a single work which is studied in depth, from its techniques, origin and history, to its position

in the artist’s practice and the contemporary debates. The study is made available, in a folder on the

bench.

AN ARTWORK IS A SYSTEM that cannot be reduced only to an object or an index (certificate,

instructions, etc.). It also includes the histories (material and conceptual), the trajectories (physical

or virtual) and the narratives (past or to come) generated by the artwork: this is what this programme

will research.

TO STUDY IS TO DEvOTE TIME and attention to a particular subject, to acquire knowledge. It can also

refer to a piece of work done for practice or an experiment. It is this sense that we would like to

pursue – not the transmission of knowledge or the act of contemplation, but rather an invitation to

act.

STUDY IS NOT AN ATTEMpT to capture or seize but a methodology of encounter and the insistence on

the provisionality as both form and content within the process of research. It is an exercise to respond

to the infinite demand of the work. Not to bring forth any historical truth but to enter into a dialogue

with the work.

IN THIS SENSE THE STUDY IS NOT FINITE, but demands the reader to take up multiple positions and

viewpoints. More than anything, it asks the viewer to engage with the artwork by, at least, spending

some time with it.

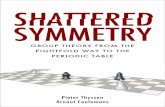

STUDY OF SHATTERED RED TILES WITH OLD BRICKS AND DECAYING WOOD is a sculptural

work by Boyle Family from 1973/74 with materials recorded as: mixed media, resin and fibreglass. It

measures 183 x 183 x 11.5 cm, and is signed and dated on the reverse with: ‘Study of Shattered Red

Tiles with Old Bricks and Decaying Wood 1973/74, Boyle Family, Joan Hills, Georgia Boyle, Mark

Boyle, Sebastian Boyle’. This work was acquired for the David Roberts Collection from the Fine Art

Society, London in 2005 and was included in the exhibition Works from the David Roberts Collection

at David Roberts Art Foundation, Fitzrovia in 2008, together with works by Doug Foster, Anselm

Kiefer, Hyungkoo Lee, Antony Gormley and Gerry Judah.

THE WORK pRESENTS a randomly-selected, square section of West London ground, featuring red tile

paving with parts broken into fragments, and the accompanying dust and detritus.

Shattered Red Tiles with Old Bricks and Decaying Wood is an example of an Earth Study, the

project for which Boyle Family is best known. Earth Studies were started in the early 1960s by Mark

Boyle (1934-2005) and Joan Hills (b.1931), and have been continued in collaboration with their two

children Sebastian (b.1962) and Georgia (b.1963) ever since.

Mark and Joan’s earliest works include happenings staged in Edinburgh, performances at the

ICA, London and light projections with Soft Machine and Jimi Hendrix, as well as their early junk

paintings. These diverse early works were the beginnings of their pursuit to make works which

encompass the whole of reality. At the occasion of an exhibition at Indica Gallery, London in 19661,

Mark Boyle stated ‘I am not trying to prove any thesis and when one is concerned with everything,

nothing (or for that matter anything) is a fair sample. I have tried to cut out of my work any hint

of originality, style, super-imposed design, wit, elegance, or significance. If any of these are to be

discovered in the show then the credit belongs to the onlookers.’

Re-connecting art with the reality of everyday life, as opposed to a discipline that was self-referential,

was a general concern for many artists in the 1960s. Most galleries in London at the time showed

abstract paintings and stylised works concerned with formal aesthetics; but Boyle Family, amongst

other artists, became disillusioned with this art world context and wanted to challenge routine

perceptions or preconceptions of the world. Everything was worthy of study and ‘in the end the only

medium in which it will be possible to say everything will be reality’.2 Other practices concerned

with urban detritus, the mundane and the environment also came out of post war and 1960s

countercultural movements. Hamish Fulton, Richard Long and Robert Smithson all explore the

relationship of the individual to their environment and to everyday materials. The 1969 moon landing

and the first photograph of Earth from outer space from Apollo 17 in 1972 brought about a significant

1 Indica Gallery was located on Mason’s Yard (off Duke Street), London and was co-owned by John Dunbar, Peter Asher and Barry Miles. The exhibition ‘Presentation by Mark Boyle’ took place from July to August 1966.2 Quote from Mark Boyle, ‘Happenings’ ICA Bulletin , June 1965, no.147

shift in the consideration of our position on, and our relationship to the Earth. Artists, perhaps with

this new perspective, followed divergent paths. Some used land as an artistic medium, whilst others

were inspired to pursue a pure aesthetic experience of the world, liberated from materiality. For Boyle

Family however, neither of these strategies was employed. To maintain objectivity in their practice

they followed a scientific approach: an archaeology of the contemporary 3.

IN 1961 Mark and Joan started to work on assemblages, for which they used material found on vacant

lots and demolition sites in London. Wooden frames, bicycle wheels and other junk items were glued

to wooden boards, which were also found on these sites. The first Earth Studies were made in 1964

on Norland Road in the Shepherds Bush area. During one of these visits, they came across an empty

frame from a broken television set. The initial position of the frame contained a composition with

a unique quality. They tried subsequently to position the frame on the ground and found that this

quality could not be reproduced, the resulting image appeared contrived. This led them to throwing

the frame, trying to eschew choice or aim, and they found each time a perfect and perfectly neutral

image. From this moment on they decided to include chance rather than choice in order to isolate

different sections of the ground. Random selection provided a way of focusing attention without an

artistic agenda.

In these early works, Boyle Family created Earth Studies by transferring as much real material as

possible utilising a string grid (similar to that used in archaeological drawings) to a board, using glue,

resin and screws. Their production techniques significantly changed between the first Earth Studies

and the methods used in Study of Shattered Red Tiles. They significantly refined their methods of

production, and subsequent iterations were more accurate and objective, each time making technical

discoveries, which were incorporated into the process. The sites in which existing surface elements

could not easily be transferred to the work led them to use resin to fix the surface material. They were

later able to refine the process with the introduction of fibreglass. Their exact methods, however, can

only be speculated upon as Boyle Family have never explained them: they describe the discussion

of technique as distracting. The collaborative process and cooperative manufacture, along with a

secretive approach to production methods, diverts attention away from the craft qualities and any

artist figure as personality. We can be amazed by the verisimilitude of these earth probes, but any

kind of realism is a by-product of presenting reality itself.

IN THE LONDON SERIES (1967 – 1970) the rectangle was no longer thrown on demolition sites that

Hills and Boyle chose, instead they acquired a map of the area surrounding their flat on Holland Park

Avenue and threw darts at it to arrive at their locations. Every point on the map had an equal chance

of being studied.

3 The Institute of Contemporary Archaeology was inaugurated in 1966 at its first event, ‘DIG’. Boyle Family sent invi-tations out to friends including John Latham and Jasia Reichardt. Attendees were taken to a cordoned off area, which used to be an old garden statue factory. Many were dressed in their Sunday best but all were instructed to dig. The multitude of statue fragments were then taken to Hills and Boyle’s flat and later shown as an exhibition.

THIS pROCESS WAS DEvELOpED INTO THE WORLD SERIES (1969 – ongoing), for which friends

were invited to their flat and asked to throw darts at a world map whilst blindfolded – perhaps the

intention was to remove limitations imposed by the London map. The sites from the World Series

would also draw together aspects of their investigation into reality as multi-sensational presentations.

The actual earth, and evidence of the plant, animal and human life, was collected and put on the wall

for examination.

Study of Shattered Red Tiles was made during a significant period in Boyle Family’s chronology. It

was made after they had begun the London and World Series, and had considerably developed their

methods for selection and execution of the studies. However, it was still a few years prior to them

representing Britain at the 39th Venice Biennale in 1978. The work is not part of a particular series

(London, World, Docklands etc), instead it belongs to a group of studies that were not systematically

made. Rather than arriving at the location in the method detailed for the World Series, the work

Study of Shattered Red Tiles, as an individual Study, had its location determined to a degree by

convenience of access to a site or because they had been granted permission to a location. Once on

site, however, they would still follow their method of selection by throwing a carpenter’s right angle,

to determine one corner of the square for the exact site of the Study.

BOYLE FAMILY’S STUDIES ARE NOT METApHORS, signs or pretenders. Although we might be

puzzled by their verisimilitude, it is clear that these are artworks and not sections of ground that have

literally been dug up. Their operational aesthetic is that of a painting hung in a gallery, sometimes

with very precise lighting instructions to heighten the sense of crumbling masonry or architectural

elements. There is a shift from the horizontal to the vertical, from the ground to display. What was

once passed-by or forgotten now becomes a point of concentration in which we approach these rarely

acknowledged fragments of the world. We suddenly find ourselves studying and paying attention

to the colours of gravel, the shape of a broken glass bottle, the perforations in tiles and the lines in

decaying wood. What they suggest is not the salvage of the past, but fragments recovered from the

detritus of the present. They restore to our attention that which has been discarded or neglected;

the quotidian that we tread on without consideration. The aim is not to elevate the mundane to

the magnificent, rather, to change our attitude to all facets of reality. We are asked to reconsider

the distinctions we make between what is discarded or ignored as insignificant, and that which is

regarded as vital or essential. ‘The most complete change an individual can affect in his environment,

short of destroying it, is to change his attitude to it. From the beginning we are taught to choose, to

select, to separate good from bad, best from better. Our entire upbringing and education are directed

towards planting the proper snobberies, the right preferences. Ultimately these studies are concerned

with everything as it is.’4

4 Mark Boyle in Control Magazine, No.1, 1965

ALTHOUGH THEY STRIvE TO REpLICATE REALITY as much as possible, Boyle Family acknowledge

that every work is a failure, inasmuch as only the original site is perfect. They know that

selections can never be truly random and that it is impossible to eliminate themselves and their

own subjective influences from the work. They recognise that the very act of isolating and recording

changes the meaning of what is introduced to our vision. Studies ‘present as accurately and objectively

as I can manage certain sites randomly selected, isolated at one moment. The next moment the

sites are different. In half an hour they are transformed. And you have the situation as it was at that

instant, perhaps already partially invalidated by its permanence and its isolation.’5

There is a sense of timelessness within these works. It is difficult to distinguish early pavement

studies from more recent works. Looking at Study of Shattered Red Tiles, one could think that it is

the reproduction of an area of ground from the 70s, but it could just as well be a scene 30 years’ from

now. ‘This is one of the problems with science fiction. It always seems to see the future in terms of the

dramatic and the exceptional, when it will of course be as ordinary and everyday as the present is.’6

Boyle Family inadvertently produced an archive of the contemporary environment. The archive, as

with these works will never approach completeness. Rather, they are distinct points or fragments

which, however neutrally assembled, can never present a totality. Gaps between the sites are

fictionalised. What we are asked to do is simply to examine these points and to engage with them.

5 Mark Boyle quoted in J.L.Locher, Mark Boyle’s Journey to the Surface of the Earth. Edition Hansjörg Mayer, Stutt-gart, 1978. P.57-586 Mark Boyle quoted in J.L.Locher, Mark Boyle’s Journey to the Surface of the Earth. Edition Hansjörg Mayer, Stutt-gart, 1978. P.79

INTERvIEW WITH SEBASTIAN BOYLE

SANDRA pUSTERHOFER: My first question regarding this work ‘Study of Shattered Red Tiles with Old

Bricks and Decaying Wood’ refers to the reverse. It is inscribed as 1973/74, Boyle Family, Joan Hills,

Georgia Boyle, Mark Boyle, Sebastian Boyle. So at the time of production you would have been 11 or

12 and Georgia a year younger. I believe you didn’t start to exhibit as ‘Boyle Family’ until 1985. How

much were you and your sister involved at this early stage?

SEBASTIAN BOYLE: Georgia and I started working on the pieces from an early age, we have always

resisted putting a date on it, because it was such a natural process, but maybe we were six or seven.

One thing to remember is that Mark and Joan didn’t go to art school, so they hadn’t got into the

idea that they needed a separate studio. We would come in from primary school and they would be

working on a piece and Mark would call out ‘Christ this bucket of stuff is going off’ and it would be all

hands on deck to use the resin before it went off. We couldn’t afford to waste a bucket of resin.

Sp: The work was bought for the David Roberts Collection in 2005 from the Fine Art Society, but we

have no records for the work prior to this date. Was it produced for a particular exhibition or do you

remember if it was displayed anywhere?

SB: The piece was bought by the Fine Art Society at Christie’s South Kensington in a 20th Century British

Art auction, on 30 June 2005, lot 379. They then exhibited it at the British Art Fair and in a 20th

Century exhibition they put on in the gallery the same year, from which they sold it to the David

Roberts Collection. Our archives are still being sorted out and there are quite a few gaps. It’s history

before then still has to be pieced together.

Sp: You’ve mentioned that Boyle Family is not a democracy, it’s four feuding dictators. We know as little

about your collaborative working process as we do about your techniques of making the works. Does

each one of you have a particular role in the fabrication process?

SB: No, we divide the work up equally and all do all aspects of the work.

Sp: Study of Shattered Red Tiles is a 6ft x 6ft square, which seems to be the size for most of the larger

Studies. For works that are very labour intensive it seems quite a large surface to produce, how did

you decide on this size? Was it important to you that the works have a physical presence in the space?

SB: Yes, Mark and Joan did think the work should have a physical presence. The first point is that they

chose the square because it seemed more neutral, not portrait or landscape. They also said that at

the time there weren’t that many square paintings, so the square differentiated them from many of

the works being made at the time. They made smaller pieces, but 6’ x 6’ became the main size, I think

because it had the physical presence and was still relatively easy for two people to carry. The other

practical consideration was that having not gone to art school they hadn’t got into the habit of having

a studio. They were working at home and most doorways are 6’6”, so the 6’ size meant they could be

carried through doorways. A very important factor, of course.

Sp: How do you decide on the orientation of the work on the wall? Is there another random process

involved or do you make an aesthetic choice?

SB: There isn’t another random process involved in deciding which way they should be hung. We are

happy for the works to be hung any way on the wall. Indeed in many ways we think it is good to rotate

them in hangs. It stops you seeing them in set ways. Some pieces do have arrows on the back, but this

is mainly because of the pressure you are put under to specify a ‘right way’ up. It is easier for many

museums and public collections, as they get complaints if works are hung alternative ways...

The exceptions to this are vertical cliff pieces, which we think should be hung the same way the cliff

went, so the top of the piece is the higher part of the cliff. And also if there is a safety concern. For

example some pieces might have metal rods or broken glass etc and we try to position these ‘dangers’

out of reach of kids or out of range for poking people in the eye.

Sp: You’ve mentioned the influence of Kurt Schwitters on you as an artist and the need to get physical and

make something. This seems quite important to you as a family. You don’t have assistants and you

don’t outsource any material. Everything, from traveling to and surveying the site, to making the casts

and painting is done by Boyle Family. How important is it for you to follow through and be involved in

the process from conception to completion?

SB: We think one of the main things about making art is the physical process of making the piece and

how one of the secrets is that the process of making a piece can often put you in the right mental

framework to then come up with more ideas. So working on one piece can help generate subsequent

pieces. If it is right for some artists to have assistants or outsource their production, then good for

them, we are not critical in any way. It is just that for us, most of the other stuff involved in making

and exhibiting work is a hassle that keeps us away from making pieces. It is all that stuff we want to

delegate, so we can spend as much time working on pieces as we can.

Sp: Boyle Family’s production techniques have significantly changed since the earliest Earth Studies

in the 60’s, always trying to better your skills at recreating the reality of the sites as accurately as

possible. In the early works you were literally transferring objects and debris from the site onto board

whereas now you work mainly in fiberglass and resin. Do you still include real evidence from the

sites? It seems interesting that in order to show reality as objectively as possible you have made the

decision to include less and less of the real material. Was this mainly a question of practicality, in

terms of the time constraints on the actual sites and the comparatively lighter weight of a work made

in fiberglass and resin, or was there also a development in the conceptual/ideological approach to

your practice?

SB: There were all sorts of issues in the development of the work. Early on the move from all real material

transferred onto boards, to real material with resin and fibreglass was firstly to extend the range of

possible sites to include ones where it would be very difficult to transfer any material by hand. It

was one thing to go to a demolition site and pick up discarded bricks and other loose material, but

quite another to go to a street where the paving stones or kerb stones would be too heavy and clearly

belonged to the local council or government. There was also the issue that a lot of the finer and more

delicate material it was impossible to pick up, for example how do you pick up an area of cracked

mud or mud that is drying out after a shower and a dog has walked through it or the grains of sand

on a beach in exactly the way they were on the beach? So the casting techniques extended the range

of possibilities, to try and be more accurate and present the evidence of each site more truthfully. For

example a piece might have evidence of insects or snails moving across the site in very fine detail.

We want to include that evidence because it is a crucial part of the story of the site. Almost all of the

pieces still retain some real material, although the exact amount varies from piece to piece. The ones

with hardly anything are the snow studies, as obviously the snow and ice have melted, although in

theory these pieces could still have traces of pollution on the surface. Most pieces have a range of

real material from the site, usually the loose material, from scrapes and markings to a patina of dirt

and dust, small stones, cigarette ends, ring pulls etc. As we are all working on them at the same time,

often under the pressure of resins setting, we are never exactly sure what is mostly painted resin and

what we have left in as real. We think it is quite good that we don’t have an exact record of what we

have done on each piece. It gives the work a tension and it shows that we are all equal working on the

pieces. Each of us has the same right to work on any area of the piece as anyone else. We don’t divide

them up into areas for each of us to work on.

The idea of trying to see things as they are, for themselves, as accurately as possible is so important

and brings with it so many challenges, that the issue of development in a conceptual sense doesn’t

seem that significant to us. The big conceptual question is whether it is ever possible to see, or

experience, something objectively at all. Many people would suggest that it isn’t even worth making

the attempt. They might argue that truth is a old fashioned, rather quaint concept and that there are

myriad competing ideas of truth in any given situation. And we can go along with that idea, for us it

is more an issue of gathering evidence and making the attempt to see things objectively. It is as if we

have to forget we are artists, forget these might be shown in a gallery or museum, certainly not try

to please a curator, gallerist or critic, or ourselves. We are gathering evidence and we think that is

important for its own sake. We would suggest that even if you think the whole concept of evidence and

truth is deeply flawed, you probably still think it is a problem worth grappling with and the attempt to

gather evidence is still worth it.

Imagine the outrage if governments announced that because the concept of truth might be flawed they

are no longer going to fund research into climate change science. People would be going nuts saying

they had caved in to the fossil fuel lobby.

Sp: You have mentioned in a previous conversation we’ve had that the overall project of Boyle Family is

‘Contemporary Archeology’. Could you explain further how you see the relationship between your

practice and a scientific/archeological approach to the contemporary environment?

SB: The concept of contemporary archaeology is one of the keys to our work. Mark and Joan launched

their Institute of Contemporary Archaeology in February 1966 with a dig at the site of a burnt down

factory in Shepherd’s Bush. They invited a number of friends to come for the dig and participants

included Gustav Metzger, John Latham and Jasia Reichardt amongst others. The main idea was to try

to look at the contemporary world as if one was an archaeologist looking for evidence of past societies

or indeed a scientist of any kind trying to gather evidence. But we don’t see ourselves as scientists or

even pseudo scientists. One of the key distinctions is that our whole project is based on the idea of

trying not to have an agenda, of not trying to find evidence for or against a theory, but of just trying

to see for the sake of seeing. So an archaeologist or scientist might go to a particular location because

it is relevant to their study, there is particular evidence to find and evaluate. We go to random sites

just to see what is there and to record it as accurately as we can. We haven’t got an agenda. We are not

there to say this is evidence of x, y or z and this is bad or good. We are just saying we went to these

sites and we found and recorded this evidence.

Sp: One of the paradoxes that we come across when looking at one of the Earth Studies is that we are

presented with a square of randomly selected ground that presents to us reality as it really was. But

of course as soon as you’ve started recording the sites, you have inevitably changed them as well.

Not only through your artistic gesture but also on a practical level. You have mentioned for example

that in order to work undisturbed and not get into trouble that Mark had business cards printed

stating that he was the Director of the Institute of Contemporary Archeology and you all wore high

viz jackets to look official. And as a result of your technique, the square patch of ground was also left

‘cleaner’ than how you found it I assume, as you would lift up the surface material, dirt and gravel

in the process. There was then almost a performance or intervention at the site. How do you see this

relationship?

SB: We are very aware that we are having an effect on the sites, even a very minimal one in the case of

urban sites in London, for example with a concrete pavement and tarmac, such as at the site for..... In

general our intervention is much less than a small archaeological dig would be at the site. Our sites

are much smaller than most digs and we don’t dig down, but take a record of the surface. This is partly

because the contemporary world is the surface of the earth. It is the trace of the car or dog that passed

by in the last few minutes or the effect of the wind drying out ground as we are there working. To dig

down at all is to go back in time for evidence of the past, not the present. If the wings of a butterfly

on the other side of the world are having an effect, then we certainly are, just by getting to the site

and standing there. Obviously we try to disturb the site as little as possible and we try to record it as

undisturbed as we can.

But we are aware we are having an effect and for this reason with our World Series projects we include

a study of ourselves in the work. Recording ourselves as active agents in the exercise. So for example

with our recent World Series project in Lazio, between Rome and Naples, we took skin samples and

blood and cheek cell samples from each of us. They are not exhaustive, but they are an attempt at

showing that we are aware of this exact issue.

All conversations unless otherwise mentioned have taken place between the artist and the writer between

December 2013 and January 2014.

Boyle Family with electron micro-photographs of hairs, British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1978

InstallationofWorldSeriesmapandNyordStudy,Denmark,fromtheWorldSeries,PaulMaenzGallery,Cologne,1971