Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

-

Upload

huffpostfund -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

-

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

1/8

current as of April 23, 2009.Online article and related content

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/10/1197

. 2005;293(10):1197-1203 (doi:10.1001/jama.293.10.1197)JAMA

Ross Koppel; Joshua P. Metlay; Abigail Cohen; et al.

Facilitating Medication ErrorsRole of Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems in

Correction Contact me if this article is corrected.

Citations Contact me when this article is cited. This article has been cited 265 times.

Topic collections

Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas.ErrorQuality of Care; Quality of Care, Other; Drug Therapy; Adverse Effects; Medication

the same issueRelated Articles published in

. 2005;293(10):1261.JAMARobert L. Wears et al.Computer Technology and Clinical Work: Stil l Waiting for Godot

. 2005;293(10):1223.JAMAAmit X. Garg et al.Performance and Patient Outcomes: A Sy stematic ReviewEffects of Computerized Clinical Decision Support Systems on Practitioner

Related Letters

. 2005;294(2):180.JAMARoss Koppel et al.In Reply:

. 2005;294(2):179.JAMADon Levick et al.. 2005;294(2):1 79.JAMASteven M. Hegedus.. 2005;294(2):179.JAMACharles Safran et al.. 2005;294(2):178.JAMASam Bierstock et al.

. 2005;294(2):178.JAMAAnn Keillor et al.Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems and Medication Errors

http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/[email protected]

http://jama.com/subscribeSubscribe

[email protected]/E-prints

http://jamaarchives.com/alertsEmail Alerts

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=correction&addAlert=correction&saveAlert=no&correction_criteria_value=293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=correction&addAlert=correction&saveAlert=no&correction_criteria_value=293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=citedby&addAlert=cited_by&saveAlert=no&cited_by_criteria_resid=jama;293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=citedby&addAlert=cited_by&saveAlert=no&cited_by_criteria_resid=jama;293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/external_ref?access_num=jama%3B293%2F10%2F1197&link_type=ISI_Citinghttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=citedby&addAlert=cited_by&saveAlert=no&cited_by_criteria_resid=jama;293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/collalerthttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/collalerthttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/collalerthttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtlhttp://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtlhttp://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtlhttp://jama.com/subscribehttp://jama.com/subscribehttp://jama.com/subscribemailto:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected]://jamaarchives.com/alertshttp://jamaarchives.com/alertshttp://jamaarchives.com/alertshttp://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/mailto:[email protected]://jamaarchives.com/alertshttp://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtlhttp://jama.com/subscribehttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/180http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-bhttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/179http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178-ahttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/294/2/178http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1261http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/293/10/1223http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/collalerthttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=citedby&addAlert=cited_by&saveAlert=no&cited_by_criteria_resid=jama;293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/external_ref?access_num=jama%3B293%2F10%2F1197&link_type=ISI_Citinghttp://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/alerts/ctalert?alertType=correction&addAlert=correction&saveAlert=no&correction_criteria_value=293/10/1197http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/293/10/1197 -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

2/8

-

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

3/8

tion error so distressing, circum-stancesof medicationerror so prevent-able, and studies of CPOE preliminaryyet so positive. 21,26-28 Studies of CPOE,however, are constrained by its com-parative youth, continuing evolution,need to focus on potential rather than

actual errors, and limited dissemina-tion (in 5% to 9% of US hospitals). 29-36Two critical studies 21,30 examined dis-tinctions between reductions in pos-sible ADEs vs actual reductions inADEs; the former are well docu-mented and often cited, but the latterare largely undocumented and un-known. Studiesof CPOE efficacy(17%to 81% error reduction) usually focuson its advantages 2,3,6-11,14-16 andare gen-erally limited to single outcomes, po-tential errorreduction, or physician sat-

isfaction.28,30,34-40

Oftenstudies combineCPOE and clinical support systems intheir analyses. 30,40,41

Inthe past3 years, though, a few stud-ies21,26-28,30,31,33,42-46 suggested some waysthat CPOE might contribute to medica-tionerrors(eg, ignoredfalsealarms, com-puter crashes,ordersin thewrongmedi-cal records).Several decades of human-

factors research, moreover, highlightedunintended consequences of techno-logic solutions, with recent discussionson hospitals. 32,33,42-44,47-52

We undertook a comprehensive,multimethod study of CPOE-relatedfactors that enhance risk of prescrip-

tion errors.

METHODSDesign We performed a quantitative andqualitative study incorporating struc-tured interviews with house staff,pharmacists, nurses, nurse-managers,attending physicians, and informa-tion technology managers; real-timeobservations of house staff writingorders, nurses charting medications,

and hospital pharmacists reviewingorders; focus groups with house staff;and written questionnaires adminis-tered to house staff. Qualitativeresearch was iterative and interactive(ie, interview responses generatednew focus group questions; focusgroup responses targeted issues forobservations).

Setting We studied a major urban tertiary-careteaching hospitalwith 750beds, 39000annual discharges, and a widely usedCPOE system (TDS) operational therefrom 1997 to 2004. Screens were usu-

ally monochromatic with pre-Win-dows interfaces (EclipsysCorp,BocaRa-ton, Fla).Thesystemwasusedonalmostallservicesandintegrated with thephar-macys and nurses medication lists.

This study was approved by theUni-versity of Pennsylvania institutional re-view board. The researchers were notinvolved in CPOE system design, in-stallation, or operation.

Data CollectionIntensive One-on-One House Staff Interviews . To develop our initial ques-tions, we conducted 14 one-on-onehouse staff interviews. An experi-enced sociologist (R.K.) conducted theopen-ended interviews, focusing onstressors and other prescribing-errorsources(mean interview time, 26 min-utes; range,14-66 minutes).

Focus Groups . We conducted 5 fo-cus groups with house staff on sourcesof stress andprescribing errors, moder-atedbyanexperiencedsociologist(R.K.)andaudiorecorded.Participantswerere-imbursed $40 (average group size, 10;

range, 7-18; and average length, 1.75hours; range, 1.4-2 hours).Expert Interviews . We interviewed

the surgery chair, pharmacy and tech-nology directors, clinical nursing di-rector, 4 nurse-managers, 5 nurses, aninfectious disease fellow, and 5 attend-ing physicians. All interviews, except1,wereprivately conducted bythesameinvestigator (R.K.).

Shadowing and Observation . Dur-ing a discontinuous 4-month period(2002-2003),weshadowed4 house staff,

3 attending physicians,and 9 nursesen-gagedin patient care andCPOEuse. Weobserved 3 pharmacists reviewing or-ders. The researcher (R.K.) wore a fac-ulty identification badge. Observationnotes were freehand but guided by theinterview findings.

Survey . From2002to thepresent, wedistributed structured, self-adminis-

Box. Advantages of CPOE Systems Compared With Paper-BasedSystems 1,2,6-9,11,13-15

Free of handwriting identification problemsFaster to reach the pharmacyLess subject to error associated with similar drug namesMore easily integrated into medical records and decision-support systemsLess subject to errors caused by use of apothecary measuresEasily linked to drug-drug interaction warningsMore likely to identify the prescribing physicianAble to link to ADE reporting systemsAble to avoid specification errors, such as trailing zerosAvailable and appropriate for training and educationAvailable for immediate data analysis, including postmarketing reportingClaimed to generate significant economic savings With online prompts, CPOE systems can

Link to algorithms to emphasize cost-effective medications

Reduce underprescribing and overprescribingReduce incorrect drug choices

Abbreviations: ADE, adverse drug event; CPOE, computerized physician order entry.

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

1198 JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 (Reprinted) 2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/ -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

4/8

tered questionnaires to house staff whoorder medications via CPOE. The 71-item questionnaire focused on work-ing conditions andsources oferror andstress. We report here on 10 CPOE-related questions. We constructed the

survey after our interviews and focusgroups, leading us to provide separateanswer options about sources of errorandsourcesof stress; addquestionsonCPOE asa possible source oferror risk,an issue that emerged in our qualita-tive research; and quantify the fre-quency of these error risks. Not allCPOE-related error risks are ame-nable to survey questions. We haverobust survey results on 10 of the 22identified error risks; these findingsare presented with the qualitativefindings.

Thesampled population (N=291) in-cluded house staff who typically entermore than 9 medication orders permonth.The targetstudypopulation ex-cluded648residents in services thatsel-domuseCPOE: pathology, podiatry, oc-cupational medicine, anesthesia,radiology, radiation oncology, ophthal-mology, and dermatology.

More than 70% of the question-naires were administered at routinehouse staff meetings. Other house staff

were located via departmental coordi-nators or pagers. Participants received$5 coupons for local coffee shops.Twohundred sixty-one house staff (88% of the target population) completed thequestionnaire.

RESULTSCharacteristics of the house staff wereas follows. Of 94 interns contacted, 85(90.4%) participated; of 96 second-year residents, 84 (87.5%) partici-pated; and of 107 third- through fifth-year residents,92 (85.9%) participated.Theparticipating samplewas44.8% fe-male,66.3%white, and 32.5% were in-terns. Participants mean age was 29.6years. These data didnot differ signifi-cantly from characteristics of nonpar-ticipants.

Our qualitative and quantitative re-search identified 22 previously unex-plored medication-error sources thatusers report to be facilitated by CPOE. We group these as (1) information er-rors generatedby fragmentation of dataand failure to integrate the hospitalsseveral computer and information sys-tems and (2) human-machine inter-face flaws reflecting machinerules thatdo not correspond to work organiza-tion or usual behaviors.

Information Errors: Fragmentationand Systems Integration FailureAssumed Dose Information . Housestaffoftenrelyon CPOE displays to de-termine minimal effective or usualdoses. The dosages listed in the CPOE

display, however, are basedon thephar-macys warehousingandpurchasing de-cisions,not clinicalguidelines. For ex-ample, if usual dosages are 20or 30mg,the pharmacy might stock only 10-mgdoses, so 10-mg units are displayedonthe CPOE screen. Consequently, somehouse staff order 10-mg doses as theusual or minimally effective dose.Similarly, house staffoften rely onCPOEdisplays for normal dosage ranges.

House staff regularlyuse CPOEtode-termine dosages ( TABLE). In the last 3months, 73% of housestaff reported us-ing CPOE displays to determine lowdoses for medications they did notusu-ally prescribe; 82%used CPOE displaystodeterminerangeofdoses(Table).Twofifths(38%-41%)used CPOE displays todetermine dosages at least a few timesweekly; 10% to 14% used CPOE dis-plays in this misleading way daily.

MedicationDiscontinuationFailures .Ordering new or modifying existingmedications is usually a separate pro-cess from canceling (discontinuing)

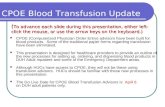

Table. Frequencies of Reported Medication Ordering Errors and Error Risks Involving the CPOE System (n = 261 Respondents)

Error Type

Error Frequency During Past 3 Months, %

NeverLess Than

Once a Week About a FewTimes a Week

About Oncea Day

More ThanOnce per Day

MissingResponse, %

Information Errors *

Used CPOE to determine low dose for infrequently usedmedications

27.3 34.6 28.5 7.3 2.3 0.3

Used CPOE to determine the range of doses forinfrequently used medications

18.5 40.4 27.3 10.8 3.1 0.3

Delayed for several hours canceling medication becauseof fragmented CPOE display

48.6 29.0 12.0 6.2 4.2 0.6

Observed a gap in antibiotic therapy because of unintended delay in reapproval of antibiotic

16.9 43.5 26.9 6.9 5.8 0.3

Human-Machine Interface Flaws

Not able to quickly tell which patients ordering forbecause of poor CPOE display 45.4 32.3 12.3 5.0 5.2 0.3

Been uncertain about patients medications becauseof multiple CPOE displays

28.5 25.4 23.4 11.7 10.9 1.5

Delayed ordering because CPOE system down 16.3 45.0 33.1 8.8 4.6 0.3Had difficulty specifying medications and problems

ordering off-formulary medications8.5 37.1 30.9 12.0 11.6 0.6

Abbreviation: CPOE, computerized physician order entry.* Generated by fragmentation of data and failure to integrate the hospitals several computer and information systems.A reflection of machine rules that do not correspond to work organization or usual behaviors.

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 1199

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/ -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

5/8

an existing medication. Without dis-continuing the current dose, physi-cians can increase or decrease medica-tion (giving a double total dose, eg,every 6 hours and every 8 hours), addnew but duplicative medication, and

addconflictingmedication.Medication-canceling ambiguities are exacerbatedby the computer interface andmultiple-screen displays of medications; as dis-cussed below, viewing 1 patients medi-cations may require 20 screens.

Discontinuation failures for at leastseveral hours from not seeing pa-tients complete medication recordswere reported by 51%(Table).Twenty-two percent indicated that this failureoccursa fewtimes weekly, daily, ormorefrequently.

Procedure-Linked Medication Dis-continuation Faults . Procedures andcertain tests are often accompanied bymedications. If procedures are can-celedorpostponed,no software linkau-tomatically cancels medications.

Immediate Orders and Give-as-Needed Medication DiscontinuationFaults . NOW (immediate) and PRN(giveasneeded)ordersmaynotentertheusual medication schedule and are sel-domdiscussedat handoffs.Also,becausemedication charting is so cumbersomeand displays so fragmented, NOW and

PRNordersare less certain tobechartedor canceled as directed. Failure to chartorcancelcanresultinunintendedmedi-cations on subsequent days or reorder-ing (duplications) on the same day.

Antibiotic Renewal Failure . Tomaxi-mize appropriate antibiotic prescrib-ing, housestaffarerequiredto obtain ap-proval by infectious disease fellows orspecialist pharmacists. Lack of coordi-nationamonginformation systems, how-ever, can produce gaps in therapy be-cause antibioticsaregenerally approved

for3days.Beforethe thirdday, housestaff should request continuation or modifi-cation. To aid this process, reapprovalstickersare placedon paperchartson thesecond day. However, when house staff order medications, they primarily useelectronic charts, thus missing warningstickers. No warning is integrated intotheCPOEsystem,and ordering gapsex-

panduntilnoticed.Some unintentionalgaps continue indefinitely because itisunknown whether antibiotics were in-tentionallyhalted.. In thelast 3 months,83% of house staff observed gaps in an-tibiotic therapy because of unintended

delays in reapproval.Twenty-seven per-cent reportedthis occurrence a fewtimesweekly; 13%, once daily or more fre-quently (Table).

Diluent Options and Errors . A re-cent CPOE innovation requires housestaff to specify diluents (eg, saline so-lution) for administering antibiotics. Afew diluents interact with antibiotics,generating precipitates or other prob-lems. Many house staff are unaware of impermissible combinations. Pharma-cists catch many such errors, but theirinterventions are time-consuming andnot ensured.

Allergy Information Delay . CPOEprovides feedbackon drugallergies, butonly after medications are ordered.Some house staff ignored allergy no-tices because of rapid scrolling throughscreens, the need to order many medi-cations, difficulties discontinuing andreordering medications, possibility of false allergy information, and, most im-portant, post hoc timing of allergy in-formation. House staff claimedposthocalertsunintentionally encourage house

staff to rely on pharmacists for drug-allergy checks, implicitly shifting re-sponsibility to pharmacists.

Conflicting or Duplicative Medi-cations . The CPOE system does notdisplay information available on otherhospital systems.For example,only thepharmacyscomputerprovidesdruginter-actionandlifetimelimitwarnings.Phar-macists call house staff to clarify ques-tionable orders, but this additional stepcosts timeand increases error potential.Housestaffandpharmacistsreportedthat

this method generates tension.Human-Machine Interface Flaws:Machine Rules That Do NotCorrespond to Work Organizationor Usual BehaviorsPatient Selection . Itis easyto selectthewrong patient file because names anddrugsareclosetogether, thefont issmall,

and, most critical here, patients namesdo not appear on all screens.. DifferentCPOE computer screens offer differ-ing colors and typefaces for the sameinformation, enhancing misinterpre-tation as physicians switch among

screens.Patients names are grouped alpha-betically rather than by house staff teams or rooms. Thus, similar names(combined with small fonts, hecticworkstations, and interruptions) areeasily confused.

Fifty-five percent of house staff re-ported difficulty identifying the pa-tient they were ordering for because of fragmented CPOE displays; 23% re-ported that this happened a few timesweekly or more frequently (Table).

Wrong Medication Selection .Apa-tients medication information is sel-dom synthesized on 1 screen. Up to 20screens might be needed to see all of apatients medications, increasing thelike-lihood of selectinga wrong medication.

Seventy-twopercentofhouse staff re-ported that they were often uncertainabout medications and dosages be-cause of difficulty in viewing all themedications on 1 screen.

Unclear Log On/Log Off . Physi-cians can order medications at com-puter terminals not yet logged out by

the previous physician, which can re-sult in either unintended patients re-ceiving medication or patients not re-ceiving the intended medication.

Failure to Provide MedicationsAfter Surgery . When patients un-dergo surgery, CPOEcancels their pre-vious medications. Whensurgeons or-der new or renewed medications,however, the orders are suspended(not sent to the pharmacy) until acti-vated by postanesthesia-care nurses.But these activations still do not dis-

pensemedications. Physiciansmust re-enter CPOE and reactivate each previ-ously ordered medication. Surgeryresidents reported that they some-times overlooked this extra process.

Postsurgery Suspended Medica-tions . Physicians ordering medica-tions for postoperative patients whomtheyactually observeon hospital floors

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

1200 JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 (Reprinted) 2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/ -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

6/8

can be deceived by patients real loca-tion vs patients computer-listed loca-tion. If patients were not logged out of postanesthesia care, theCPOE will notprocess medication orders, labelingthemsuspended. Physicians must re-

negotiate the CPOE and resubmit or-ders for patients to receive postsurgi-cal medications.

Loss of Data, Time,and Focus WhenCPOE Is Nonfunctional . CPOE isshutdown for periodic maintenance, andcrashes are common. Backup systemsprevent loss of data previously en-tered. However, orders being enteredwhen the system crashes are lost andcannotbe reentered until the systemisrestarted. House staff reported that theneed to wait for the systems revival andorder reentry increases error risks.

Eighty-four percent reported de-layed medication orders because of sys-temshutdowns. Forty-sevenpercent re-ported that shutdowns occur a fewtimes weekly to more than once daily(Table). The CPOE manager con-firmed house staff downtime esti-mates; 2 or 3 weekly crashes of at least15 minutes are common.

Sending Medications to WrongRooms When the Computer SystemHas Shut Down . If the computer sys-tem is down when a patient is moved

withinthehospital,CPOE does notalertthepharmacy, andmedications are sentto the old room, thus being lostorde-layed. Also, wrong medications mightbe administered to new patients inold rooms.

Late-in-DayOrdersLostfor24Hours . When patients leave surgery or are ad-mitted late in the day, medications andlaboratoryordersmight be requestedfortomorrow at, forexample,7 AM.Bythetime the intern enters the orders, how-ever, it might already betomorrow(ie,

after midnight). Therefore, patients donot receive medications or tests for anextra day.

Role of Charting Difficulties in In-accurate and Delayed MedicationAdministration . Nurses are required torecord (chart) administration of medi-cations contemporaneously. However,contemporaneous charting requires

time when there is little time avail-able. Computerizedphysician order en-try systems compound this challengeconsiderably. To chart drug adminis-trations, nurses must stop administer-ingmedications,find a terminal, log on,

locate that patients record, and indi-vidually enter each medications ad-ministration time. If medicationsarenotadministered (eg, patient wasoutof theroom), nurses must scroll through sev-eral additional screens to record therea-son(s) for nonadministration.

Nurses reported that up to 60% of their medications are not recordedcon-temporaneously but arechartedat shiftend or post hoc by the nurse managervia global computer commands.

Many house staff, aware of record-ing inaccuracies, seek nurses to deter-mine real administration times of time-sensitive drugs (eg, aminoglycosides).House staff reported that these addi-tional steps are distracting and time-consuming. Interrupted ordering ormedication reviews can increase errorrisks.

Moreover, because of cumbersomecharting, some medications, espe-cially insulin, are recorded on parallelsystems (ie, paper chart, separate pa-per sheets, or directly in CPOE). Mul-tiple systems cause confusion, andoff-

system information is sometimes lost.Inflexible Ordering Screens, Incor-rect Medications . House staff re-ported that because of CPOE inflex-ibility, nonstandard specifications (eg,test modifications or specific scanangles) are often impossible to enter.Medications accompanying proce-dures must be stopped and reordered,with dangers linked to uncertain can-celing and reordering.

Similarly, nonformulary medicationscan be lost because they must be en-

tered on separatescreen sections,mightnot be sent to the pharmacy, and mightescape nurses notice (eg, nonformu-lary medication to prevent organ rejec-tion was not listed among medicationsinCPOE, was not sent to the pharmacy,and was ignored for 6 days).

Ninety-two percent reported thatCPOE is inflexible, generating difficul-

ties in specifying medications or order-ing off-formularymedications. Thirty-onepercent reported that thisoccurreda few times weekly; 24% said daily ormore frequently (Table).

COMMENTOur qualitative research identified 22situations inwhichCPOE increasedtheprobability of prescribing errors. Ourquantitative data reveal that severalCPOE-enhanced error risks appearcommon (ie, observed by 50% to 90%ofhouse staff) and frequent (ie, repeat-edly observedto occur weekly or moreoften). We broadly grouped the errorrisks as informationerrors generatedbyfragmentation of data and failure to in-tegrate the hospitals several com-puter and information systems (10 er-ror types) and human-machineinterface flaws reflecting machine rulesthat do not correspond to work orga-nization or usual behaviors (12 errortypes).Although this schema is not ex-haustive, it informs both administra-tive and programming solutions.

PerhapsCPOE-facilitated error risksreceived limited attention because themethodologies andfociofpreviousstud-ies addressed CPOEs role in error re-duction 2,3,6-11,14-16,42 and seldom its rolein error facilitation. 21,26-28,31,32,45 Onekey

study27

examined errors but was en-tirely qualitative,with no frequency es-timates. Other reasons CPOEs prob-lems may have escaped la rgerexamination include the orientation of medical personnel to solve or workaround problems, beliefs that prob-lems are due to insufficient training ornoncompliance, erratic error-report-ingmechanisms, and focus on technol-ogy rather than on work organiza-tion. 30,32,42,43,52,53 Our multimethod,triangulated approach explored wider

ranges of CPOEs effects.33,42,48,54

That CPOE use might increase thelikelihood of medication errorswas anunanticipated finding,which wouldnothave surfaced without open-endedqualitative research. Survey data pro-videda different type of validation andstrengthened our confidence in thefindings. Our error risk frequency es-

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 1201

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/ -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

7/8

timates are from a robust sample of house staff.

Weconductedresearch atonly 1 hos-pital. Although theCPOEsystem weex-amined (TDS) has comprised as muchas 60% of the market, 55-57 it is possible

that severalCPOE-facilitatederrors dis-cussed here may not be widely gener-alizable. Also, TDS, like all complexCPOEsystems,is customized andun-dergoes repeated improvements. Ourqualitative findings are not from ran-domhouse staff samples. Identified er-ror risks may be overstated or under-stated.However, oursurveyfindings arebased on an almost 90% sample of rel-evant house staff and are less likely sus-ceptible to sample bias.

House staff may have misinter-preted our questions or response cat-egories. Despite extensive pretests, fo-cus groups, and poststudy interviews,the process is hardly foolproof.

Although house staff in one-on-oneinterviews and focus groups discussedactual errors, the survey data reflecthouse staff responses or statementsabout medication error likelihood, notactual ADEs. Thus, our survey analysisfocuses on features of error-prone sys-tems ratherthan errorsthemselves.Also,we stress that hospital pharmacists re-view every order and reject about 4%;

many errors existed with paper-basedsystems, and without direct compara-tive studies wecannot contrast their rela-tive advantages; there isnoreason tosus-pect that TDS is inferior to any otherCPOE system; and it is badly designedand poorly integrated CPOE systemsthat are at issue.

CPOE is widely regarded as the cru-cial technology for reducing hospitalmedicationerrors. 2,3,6-22,30,31,58,59 As withanynewtechnology, however, initialas-sessments may insufficiently consider

risks and organizational accommoda-tions. * The literature on CPOE, withfew exceptions, 21,26-28,34,39,45 is enthusi-astic. Our findings, however,reveal thatCPOEsystemscan facilitate error risksin addition to reducing them. With-out studies of the advantages and dis-

advantages of CPOE systems, research-ers are looking at only one edge of thesword.This limitation isespecially note-worthy because many problems weidentified are easily corrected.

Ourrecommendationsconcentrateon

organizational factors. (1) Focus pri-marilyon theorganization ofwork, noton technology; CPOE must determineclinical actions only if theyimprove, orat least do not deteriorate, patient care.(2) Aggressively examine the technol-ogy in use; problems are obscured byworkarounds, the medical problem-solving ethos, and low house staff sta-tus.(3)Aggressivelyfix technologywhenit is shown to be counterproductivebecausefailuretodosoengenders alien-ation and dangerous workarounds inaddition to persistent errors; substitu-tion of technology for people is a mis-understandingofboth. (4)Pursueerrorssecond stories and multiple causa-tions tosurmount thebarriersenhancedbyepisodicandincompleteerrorreport-ing, which is standard, and manage-mentbeliefin theseerrorreports,whichobfuscates and compounds problems.(5) Plan for continuous revisions andquality improvement, recognizing thatall changes generate new error risks.

In our work, use of multiple quali-tative and survey methods identified

and quantified error risks not previ-ously considered, offering many op-portunities for error reduction. AsCPOEsystemsare implemented, clini-cians and hospitals must attend to theerrors they cause, in addition to theer-rors they prevent.

Author Contributions: Dr Koppelhad full accessto allof the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the dataanalysis. Study concept and design: Koppel, Metlay, Localio,Kimmel, Strom.Acquisition of data: Koppel, Cohen, Abaluck, Localio.Analysis and interpretation of data: Koppel, Cohen,Abaluck, Localio.Drafting of the manuscript: Koppel, Cohen.Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-tellectual content: Koppel, Metlay, Cohen, Abaluck,Localio, Kimmel, Strom. Statistical analysis: Koppel, Cohen.Obtained funding: Koppel, Metlay, Localio, Kimmel,Strom.Administrative, technical, or material support: Koppel,Cohen, Localio, Strom. Study supervision: Koppel, Cohen, Strom.Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by agrant from the Agency for Healthcare Research andQuality (AHRQ), P01 HS11530-01, Improving Pa-tient Safety Through Reduction in Medication Errors.Dr Metlayis also supportedthroughan AdvancedRe-search Career Development Award from the HealthServices Researchand DevelopmentService of theDe-partment of Veterans Affairs.Role of theSponsors: Neither AHRQnor theDepart-

ment of Veterans Affairs had any role in the designand conduct of the study; collection, management,analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the ap-proval of the manuscript.Project AdvisoryCommittee: LindaH. Aiken,PhD,Uni-versity of Pennsylvania; David W. Bates, MD, MSc,Harvard School of Medicine; Shawn Becker, RN, USPharmacopeia; Marc L. Berger, MD, Merck & Co;StevenL. Sauter, PhD, National Institute forOccupa-tional Safety and Health; Thomas Snedden, PA, De-partment of Aging; Paul D. Stolley, MD, MPH, Uni-versity of Maryland; Joel Leon Telles, PhD, DelawareValley Healthcare Council of Hospital Association ofPennsylvania.Acknowledgment: We thank Charles Leonard,PharmD; Frank Sites, MHA, RN; Joel Telles, PhD; Ed-mund Weisburg, MS; and Ruthann Auten, BA.

REFERENCES1. Lesar TS, Lomaestro BM, Pohl H. Medicationprescribing errors in a teaching hospital: a 9-year experience. Arch Intern Med . 1997;157:1569-1576.2. Kohn LT,Corrigan J, DonaldsonMS, eds. ToErr IsHuman: Building a Safer Health System . Washing-ton, DC: National Academy Press; 2000.3. Kaushal R, BatesD. Computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support systems. In: Sho- janiaKG,DuncanBW, McDonaldKM,et al,eds. Mak-ingHealthCareSafer:ACriticalAnalysisofPatientSafetyPractices .Rockville,Md:AgencyforHealthcareResearchand Quality; 2001. Evidence Report/Technology As-sessment No. 43; AHRQ publication 01-E058.4. Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE,et al. Na-ture of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals:a literaturereview. AmJ HealthSystPharm . 2003;60:1750-1759.5. Leape L, Bates D, Cullen D, et al. System analysisof adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274:35-43.6. Bates DW,Leape LL, CullenDJ,et al.Effectof com-puterized physician order entry and a team interven-tionon preventionof seriousmedication errors. JAMA.1998;280:1311-1316.7. Instituteof Medicine. Crossingthe Quality Chasm:A New Health System for the 21st Century . Wash-ington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.8. Bates DW, Kuperman G, Teich JM. Computerizedphysicianorder entry andqualityof care. QualManag Health Care . 1994;2:18-27.9. Schiff G, Rucher DT. Computerized prescribing:building the electronic infrastructure for better medi-cation usage. JAMA. 1998;279:1024-1029.10. Bates DW, Cullen D, Laird N, et al. Incidence ofadverse drugevents andpotential adverse drugevents:implications for prevention. JAMA. 1995;274:29-34.11. Bates DW, Cohen M, Leape LL, Overhage JM,Shabot MM, Sheridan T. Reducing the frequency oferrors in medicineusing information technology. JAm Med Inform Assoc . 2001;8:299-308.12. Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM,BrodieM, et al.Viewsof practicing physicians and the public on medicalerrors. N Engl J Med . 2003;347:1933-1967.13. Sittig DF, Stead WW. Computer-based physi-cian order entry: the state of the art. J Am Med In-form Assoc . 1994;1:108-123.14. Teich JM, Merchia PR, Schmiz JL, Kuperman GJ,Spurr C, Bates DW. Effects of computerized physi-cian order entry on prescribing practices. Arch Intern Med . 2000;160:2741-2747.* References 30, 32-34, 42-44, 46, 48-52, 60.

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

1202 JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 (Reprinted) 2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/ -

8/9/2019 Study: Computerized Physician Order Entry Facilitates Error

8/8

15. Bates DW,Gawande AA. Patient safety: improv-ing safety withinformation technology. N EnglJ Med .2003;348:2526-2534.16. HealthLeaders looks at hospital CPOE programs[iHealth Web site]. Available at: http://www.ihealthbeat.org/index.cfm?Action=dspItem&itemID=100527 . Accessed May 3, 2004.17. Kuperman G, Teich J, Bates DW. Improving carewithcomputerizedalerts andreminders. Assoc Health

Serv Res. 1997;14:224-225.18. iHealth. Frist aide says EMR bill could pass Janu-ary 30, 2004. Available at: http://www.ihealthbeat.org/index.cfm?Action=dspItem&itemID=100537.Ac-cessed May 1, 2004.19. iHealth. Clinton reiterates IT stance, details leg-islation. Available at: http://www.ihealthbeat.org/index.cfm?action=dspItem&itemID=100529 . Ac-cessed May 1, 2004.20. ThePatientSafety andErrors Reduction Act.June15, 2000. Available at: http://www.senate.gov/~enzi/mederr.htm. Accessed May 1, 2004.21. Berger RG, Kichak JP. Computerizedphysician or-derentry:helpfulor harmful? JAm Med InformAssoc .2004;11:100-103.22. Broder C. Lawmakers push health care IT at thestate level [iHealthWeb site]. Available at:http://www.ihealthbeat.org/index.cfm?Action=dspItem&itemD=99285. Accessed May 3, 2004.23. Petersen LA, Brennan TA, ONeil AC, Cook EF,Lee TH. Does house staff discontinuity of care in-crease the risk for preventable adverse events? AnnIntern Med . 1994;121:866-872.24. Gordon S. LifeSupport . Boston, Mass: Little Brown& Co; 1997.25. Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D, Sochalski J, Silber J.Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurseburnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987-1993.26. Ash JS, Gorman PN, Seshadri V, Hersh WR. Per-spectives on CPOE and patient care. J Am Med In-form Assoc . 2004;11-207-216.27. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. Some unintended con-sequencesof informationtechnology in health care:thenature of patient careinformationsystem-related errors. J Am Med Inform Assoc . 2004;11:104-112.28. Kaushal R, Kaveh S, Bates DW. Effects of com-puterized physician order entry and clinical decisionsupport systems on medication safety: a systematicreview. Arch Intern Med . 2003;163:1409-1416.29. AshJS, GormanPN, Seshadri V, HershWR. Com-puterized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: re-sults of a 2002survey. J AmMed InformAssoc . 2004;11:95-99.30. Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, Feinglass J, Yar-

nold P, Noshkin G. The epidemiology of prescribingerrors. Arch Intern Med . 2004;164:785-792.31. United States Pharmacopeia. MEDMARX 5thAn-niversary Data Report: A Chartbook of 2003 Find-ings and Trends 1999-2003 . Rockville, Md: UnitedStates Pharmacopeia; 2004.32. WoodsDD. Behind Human Error: CognitiveSys-tems, Computersand Hindsight . Dayton, Ohio: CrewSystems Ergonomic Information and Analysis Cen-

ter, Wright Patterson Air Force Base; 1994.33. Cook R,Render M,Woods DD.Gaps: learninghowpractitioners create safety. BMJ. 2000;320:791-794.34. Cook RI. Safety technology: solutions or experiments? Nurs Econ . 2002;20:80-82.35. Nightingale PG, Adu D, Richards NT, Peters M.Implementation of rules basedcomputerised bedsideprescribingand administration:intervention study. BMJ.2000;320:750-753.36. Bernard F, Savelyich B, Avery A, et al. Prescrib-ing safety features of general practice computer sys-tems:evaluationusing simulated testcases. BMJ. 2004;328:1171-1172.37. Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Glasen DC, et al. A com-puter-assistedmanagementprogramforantibiotics andother antiinfective agents. N Engl J Med . 1998;338:232-238.38. Sanders DL, Miller RA. The effects on clinical or-dering patterns of a computerized decision support sys-tem for neuroradiology imaging studies. Proc AMIA Symp. 2001:583-587.39. McNutt RA, Abrams R, Aron DC. Patient safetyefforts should focus on medical errors. JAMA. 2002;287:1997-2001.40. Feied C, Handler J, Smith M, et al. Clinical infor-mation systems: instant ubiquitous clinical datafor er-ror reduction and improved clinical outcomes. Acad Emerg Med . 2004;11:1162-1169.41. Ramsay J, Popp H-J, Thull B, Rau G. The evalu-ation of an information systemfor intensivecare. Be-hav Inf Technol . 1997;16:17-24.42. Woods DD, Cook RI. Nine steps to move for-wardfrom. ErrorCogn TechnolWork . 2002;4:137-144.43. Patterson ES,Cook RI, Render ML.Improving pa-tient safety by identifying side effects from introduc-ingbar codingin medicationadministration. JAmMed Inform Assoc . 2002;9:540-553.44. Woods DD. Steering the reverberations of tech-nology change on fields of practice: laws that governcognitive work.Available at: http://csel.eng.ohio-state.edu/laws/laws_talk/media/0_steering.pdf. Ac-cessed December 24, 2004.45. Shane R. Computerized physicianorder entry: chal-lenges and opportunities Am J Health Syst Pharm .2002;59:286-288.

46. Ferner R.. Computer aidedprescribingleaves holesin the safety net. BMJ. 2004;328:1172-1173.47. Woods DD, Tinapple D. Watching human fac-tors watch people at work. Presidential address at:43rd Annual Meeting of the Human Factors andErgonomics Society; September 28, 1999; Houston,Tex.48. Cook RI. Twoyearsbeforethe mast: learning howto learn about patient safety. In: Hendee W, ed. En-

hancing Patient Safetyand Reducing Errorsin HealthCare . Chicago, Ill: National Patient Safety Founda-tion; 1999.49. Ottino JM. Engineering complex systems [essay].Nature . 2004;427:399.50. Perrow C. Normal Accidents: Living With High-Risk Technologies . Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univer-sity Press; 1999.51. Sarter NB, Woods DD, Billings CE. Automationsurprises. In: SalvendG, ed. Handbook of Human Fac-tors and Ergonomics . 2nd ed. New York, NY: JohnWiley & Sons; 1997:1926-1943.52. Tucker AL, Edmondson AC. Why hospitals dontlearn from failures: organizational and psychologicaldynamics that inhibit system change. Calif ManageRev. 2003;45:55-72.53. RasmussenJ. Trends in human reliabilityanalysis.Ergonomics . 1985;28:1185-1196.54. GiacominiMK, Cook DJ.Users guidesto themedi-calliterature, XXIII: qualitative research in healthcareA: aretheresultsof the studyvalid? JAMA. 2000;284:357-362.55. TDS[now within the Eclipsys Corporation].Avail-ableat: http://www.eclipsys.com/Solutions/med_mgt.asp. Accessed December 29, 2004.56. Frost & Sullivan. US computerized physician or-der entry market, 2002. Available at: http://www.frost.com/prod/servlet/report-homepage.pag?repid=A372-01-00-00-00&ctxht=FcmCtx3&ctxhl=FcmCtx4&ctxixpLink=FcmCtx5&ctxixpLabel=FcmCtx6.Accessed May 7, 2004.57. TDS[now within the Eclipsys Corporation].Avail-able at: http://www.eclipsys.com/about/default.asp. Accessed December 29, 2004.58. Ash JS, Gorman PN, Lavelle M, Lyman J. Mul-tipleperspectives on physicianorder entry. ProcAMIA Symp. 2000:27-31.59. Ash J, Gorman P, Lavelle M, Lyman J, Fournier L. Investigating physician order entry in the field: les-sons learned in a multi-center study. Medinfo . 2001;10:1107-1111.60. Cook RI, Woods DD. Implications of automa-tion surprises in aviation for the future of total intra-venous anesthesia (TIVA). J Clin Anesth . 1996;8(3suppl):29S-37S.

COMPUTERIZED ORDER ENTRY SYSTEMS AND MEDICATION ERRORS

2005 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, March 9, 2005Vol 293, No. 10 1203

at University of South Carolina on April 23, 2009www.jama.comDownloaded from

http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/http://jama.ama-assn.org/