STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING … · Cultural Dimension, and Graphic Design Curriculum....

Transcript of STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING … · Cultural Dimension, and Graphic Design Curriculum....

Man In India, 95(2015) © Serials Publications(Special Issue: Researches in Education and Social Sciences)

Address for communication: Wong Shaw Chiang, Raffles University Iskandar, Malaysia, E-mail:[email protected]

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING SOCIALRESPONSIBILITY DIMENSIONS INTO GRAPHIC DESIGNCURRICULUM

Wong Shaw Chiang, Shafeeq Hussain Vazhathodi Al-Hudawi,Abdul Rahim Hamdan and Mohamad Burhanuddin Musah

Integration of social responsibility dimensions into graphic design curriculum has receivedincreasing attention nowadays, and that is due to exclusive impacts designers have in society.Despite this, precise understanding among students of integrating social responsibility pertainingto societal, environmental, and cultural dimensions into graphic design curriculum, specificallyin the Malaysian context is inconclusive. In this qualitative study, 3 groups of students from 3private colleges in Malaysia shed some light on their understanding of social responsibilitydimensions, and with regards to their experiences of how these dimensions are integrated by theirlecturers into the graphic design curriculum. Results indicate that while all students present asufficient understanding of social responsibility in societal and cultural dimensions, it tends to belacking in environmental dimension. Further, most students express that despite their lecturers’planning for meaningful content and pedagogical processes for the graphic design courses, nospecifically related formal goals are integrated into the curriculum. The results, therefore suggestthat more precise definitions of each social responsibility dimension needs to be integrated intographic design curriculum, specifically in the curriculum purposes, content, pedagogical processes,and assessment methods.

Keywords: Social Responsibility Dimensions, Societal Dimension, Environmental Dimension,Cultural Dimension, and Graphic Design Curriculum.

Introduction

Global communication trends have become more sophisticated due to theadvancement of digital technology. The trends have influenced the economicbehavior of humans, and as a result an affluent consumer culture is growing. Insuch a situation, the question of “how could graphic design practitioners (GDPs)perform their visual communication skills in advertising, marketing, promotion,and packaging more responsibly?” is particularly relevant because, the very natureof graphic design (GD) is social, and GDPs are to be at the forefront of “makingthe world a better place for all” as they, among others, are considered to be agentsof social change as well (Whiteley, 1993, p. 98). They have the ability to shapepublic information and influence people’s lifestyles (Mononutu, 2010). As such,besides focusing just on the traditional role as facilitators of communication forcommercial purposes to fulfill client needs and the client’s aesthetic expectations,GDPs should take account of designer ethics and particularly of the socialresponsibility (SR) with regards to societal, environmental, and cultural dimensions.

548 MAN IN INDIA

GD education mainly focuses on “specialties such as magazine layout, bookand record covers, posters, advertising, and Web-design, …[and equips] studentswith a well-rounded, professional portfolio” (Heller and Fernandes, 2006, p. 26).According to Findeli (1994, p. 50), GD education should make students familiarwith “moral questions governing or resulting from the conception, production,distribution, and the use of [such] artefacts” (Findeli, 1994, p. 50). As he furtherclaims strong design ethics and SR components, i.e. the evaluation of design, eco-design or the social impacts of design have to be taken into account while planningand developing GD related program (Findeli, 1994). According to the oldest, largest,and most prestigious American professional design association, American Instituteof Graphic Arts (AIGA), GD education has assumed the role of enhancing thesocially responsible and ethical positions of GD profession over the past 25 years(AIGA, 2014). But there are concerns that GD students are more careful of theaesthetics of the final products than the process of designing solution for a socialissue. In this context, this article aims to report a study conducted on students’understanding of GD curriculum (GDC) in terms of integrating social responsibilitydimensions (SRDs) into it. Specifically the study looked into students’understanding of SRDs in the socially and culturally diverse context of Malaysiaand particularly the ways in which they think these dimensions were integratedinto different GDC components.

Social Responsibility

Social Responsibility is about our respect for the planet, its people, and theenvironment (Vesselle and Mckay, 2011). Since all of our decisions and actionscarry certain impacts on the planet, to understand such impacts and to accept theresponsibility is sine qua non to a morally and ethically concerned global citizen,especially in the context of unprecedented environmental, social and cultural crisesthat demand our attention (Vesselle and Mckay, 2011). It is unlikely thatpractitioners of any profession including GD be excluded from understanding andintegrating SR into their practices.

Social Responsibility Dimensions and Graphic Design Practices

There are pursuits more worthy of our [GDPs] problem-solving skills.Unprecedented environmental, social and cultural crises demand our attention.Many cultural interventions, social marketing campaigns, books, magazines,exhibitions, educational tools, television programs, films, charitable causes andother information design projects urgently require our expertise and helps(Adbusters, 2000).

Concerns on integrating SR into GD began since 1960s when Ken Garland(1964) started to advocate the “First Things First” manifesto in critical responseto the status of quo of the advertising industries’ overemphasis on the commercially

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 549

driven design jobs, where it seemed to contribute nothing to the transformations,improvement, and wellbeing of the society. The revised version of the “First ThingsFirst” manifesto urges the designers to rethink and reevaluate their social positionin the 21st century (Adbusters, 2000). These two manifestos claim that there areother worthier things than using designers’ skills and imagination for commercialrewards and promotion of products, where designers have to critically distinguishbetween “design as communication (giving people necessary information)” and“design as persuasion (trying to get them to buy things)” (Poynor 2005, p. 4). Asone of the coordinators of the “First Things First” 2000 manifesto, Poynor insiststhat the current state of GD practice is heading towards a distorted direction whereit emphasizes too much on promoting unnecessary commercial products. Thus, hestates that “designers are engaged in nothing less than the manufacture ofcontemporary reality” (p. 3) and do not think of who truly benefits from theircreative design solutions.

In response to this, another social designer and educator Victor Papanek (1977),thus, for example has called for a new social agenda for designers in his book“Design for the Real World”. As a strong proponent of socially responsible design,he criticizes commercial markets creating needless and useless designs. He urgesdesigners to design for social and human needs. Such needs range from the needsof third world countries to the special needs of the elderly people, the poor,handicapped and disabled.

Designing for the society is “integral part of the political, social, cultural,environmental, commercial and technological world around us” especially in thebackground of the rampant consumer-driven culture, where design has become arecognized corporate asset (Akama, 2008, p. 20). GDPs hence are required “tothink more critically about what they are doing and the cultural, social andenvironmental conditions they contribute to” (p. 56). In other words, GDPs havedistinct social roles to play, specifically in societal, environmental, and culturaldimensions when designing for society.

To Berman (2009) societal dimension of design is about “[not] just doinggood design, [but] doing good” in terms of accelerating awareness, transmittingpositive information, social values, and norms along with using persuasive designskills (Berman, 2009, p. 156). Perkins (2006) shares with Berman’s opinion, thatdespite focusing on creating artificial needs or promoting unnecessary productsthrough manipulative or deceptive advertising and marketing messages, designersneed to invest part of their efforts to transform the world to be a better place forliving (Perkins, 2006; AIGA, 2014).

Sustainability is the key focus of the environmental dimension, where accordingto AIGA, graphic designers need to be aware and make others aware aboutenvironment friendly issues through design. To Thorpe (2006), it concerns witheventually supporting human wellbeing, such as reducing the use of harmful

550 MAN IN INDIA

materials and excessive waste, encouraging the development of renewable energy,and instilling environmental awareness to every design user.

Cultural dimension is about GDPs working in harmony with the societalconcerns regarding languages, traditions, norms, beliefs, values, and etc., at timessacrificing their personal views for the wellbeing of the collective society (Meyer,2008). In order to avoid misunderstanding or conflicts, GDPs need to be as objectiveas possible to interpret and reinterpret the above aspects, especially from theperspectives of design users.

Integrating Social Responsibility Dimensions into Graphic Design Curriculum

Indeed, there is an immense body of growing literature on the indivisible relationshipbetween GD practice and SR (Mononutu, 2010; Berman, 2009; Heller and Vienne,2003; Frascara, 1997; McCoy, 1994), designing for social change (Shea, 2012),using GD education to enhance the socially responsible positions of GD profession(Social Impact Design Summit, 2012; AIGA, 2014; The International Council ofGraphic Design Association (ICOGRADA), 2011), and so forth.

This body of literature, in short, presents GD as “a tool for social, cultural, andeconomic development” (Harland, 2011, p. 34), as it is equally about developingcreative solutions to the advertising demands of new global marketplace.

In response to this, in effect, a large numbers of design institutions worldwidehave started integrating SRDs to their GDC. Their GDC encourages students toengage with their community thereby allowing them to gain deeper understandingof the social causes and obtain critical knowledge of the consequences of designfrom various dimensions.

For example, The Department of Visual Arts (DVA) of Stellenbosch Universityin South Africa has implemented a Community-based Service-learning modulefor first three-year GD students (Costandius and Rosochacki, 2012). As part of theGD program, this module seeks to develop societal awareness among students.Students are given various projects to exercise their critical thinking skills and toengage with the community on issues such as cultural oppression, racial relation,political violence, citizenship, collective identity, national memory, and etc. Theyare challenged to search for creative methods to articulate and resolve these issuesutilizing visual communication skills. In Swinburne University of Technology(2015) of Melbourne, Australia has included courses such as Sustainable Designas well as Contemporary Design Issues in their GD program and they aim to dealparticularly with “design for environmental, global, and social sustainability”. InEngland, educational institutions such as Kingston University London (2015) andthe London College of Arts (2015) provide opportunities for students to engagewith the issues of SR that stem beyond charity and good intentions.

The integration of SR into GDC of the above Universities and educationalinstitutions is encouraging. However, such meaningful integration does not happen

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 551

by chance. Plenty of efforts are required in making appropriate adjustments in thecurriculum in order to develop better understanding of students with regards toSRDs and related issues.

Graphic Design Curriculum in Malaysia

In Malaysia, in line with the aspiration of the Ministry of Higher Education ofMalaysia (MOHE) to “produce individuals who are competitive and innovativewith high moral values to meet the nation’s aspirations” (MOHE, 2009), theMalaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA) has fixed a set of guidelines on thedevelopment and implementation of Art and Design related programs, whichcertainly also include GD. The Program Standards by MQA (2012) states thegeneral aims for the Art and Design Programs as to provide graduates with in-depth and broad-based knowledge, advanced visual communication skills, criticalthinking skills, creativity and innovation in specialized and interdisciplinaryareas of studies, contextual understanding, entrepreneurship and professionalism,which contribute towards the creative industry and the visual culture (MQA,2012).

Furthermore, it is particularly important to note that SR is formally stated byMQA (2012) as one of the significant domains of intended learning outcomes inthe Program Standards. Among eight domains of intended learning outcomesidentified by the MQA, domain 3 and 4 are particularly relevant to SRDs. They aredomain (3): social skills and responsibilities; and domain (4): values, attitudes,and professionalism (MQA, 2012). Thus, they are significant guidelines for thedevelopment and implementation of GD related program in Malaysia, in terms oftheir contents, pedagogies, and assessment methods.

Contents of GDC as provided in Malaysia combine both practical andtheoretical aspects, thus exposing students in a balanced approach to the theoryand practice in GD. Both creation as well as analysis of the meaning and functionsof the particular communication designs is parts of GDC. The courses as identifiedby the MQA (2012) include advertising design, computer graphic, corporateidentity, drawing and illustration, visual culture, media and time-based art,packaging design, principles of design, publication design and electronic pre-press,typography, and visual communication (pp. 54-55). Various pedagogies such asInquiry Learning Model (ILM), Problem Based Learning (PBL), and IntegrativeLearning (IL) are among the recommended methods of instruction by the MQAemphasizing on developing and polishing the critical and creative thinking skills,problem solving abilities, communication, teamwork, and interpersonal skills, andreflective thinking skills of students so that they can undertake the challenges ofthe industry. Learning outcomes of each component courses of GDC are to beassessed for their distinctive objectives using both summative and formativetechniques.

552 MAN IN INDIA

However, various concerns posed by writers like Poynor (2005) and Tung(2002) are of great significance to the Malaysian context of presently availableGD education programs. This is because, the typical concern of GD education, isto prepare students for entry-level employment (Heller, 2005). Perceivably then,even though there are social projects structured in the GD courses, students aremostly assessed based on the aesthetics of the final products instead of theirunderstanding and cultivation of the sense of designers’ SR. Up to the best noticeof the researchers, there are no research studies on the understanding among GDstudents of SR pertaining to societal, environmental, and cultural dimensions,specifically in the Malaysian context. Thus their understanding of these dimensionshas remained vague. The current study, therefore explored how GD studentsunderstand the societal, environmental and cultural dimensions of SR andparticularly, how they think about these SRDs are integrated into the four essentialcomponents of curriculum: purposes, content, pedagogical processes, andassessment methods of the GDC.

Methods

In this study, three groups of students associated with GD related programs fromthree private colleges in Malaysia were selected according to non-probabilitypurposive homogeneous sampling technique (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison, 2000)to find out how they think SRDs are integrated into the GDC. Twelve studentswere chosen based on their learning experiences with regards to the GD relatedcourses (Table 1) and they were divided into three groups. In order to make theamount of data manageable yet to maintain its dynamism in quality, a focus groupmethod was used to collect data.

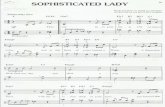

TABLE 1: THE PROFILE OF GD STUDENTS

Student Group No. of Learning Course TitleParticipants Experiences

Group-1 4 3 Years Final Project (Multimedia)Group-2 4 2 Years Communicate with Words and ImagesGroup-3 4 1.5 Years Packaging Design

The discussion questions were reviewed for their clarity, understandability,and relatedness in achieving the main objectives of the study through expertjudgment. Before conducting discussion, respondents were presented with threesituations or cases, each referring to any of the societal, environmental, and culturalconcerns in Malaysia. According to the given situations or cases, the students wererequired to provide their understanding of each SRD in relation to GD practices inMalaysia and how they feel about SRDs being integrated into the GDC components.The responses of the students in the group discussions were recorded, and thentranscribed word by word. The transcriptions were coded using technique as

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 553

suggested by Creswell (2007). Then based on the frequency of occurrence majorthemes were listed, classified, for data analysis purposes, and were accordinglylabelled taking account of the aims of the study. Furthermore, the themes werecross analyzed, compared, and contrasted to form a more structural interpretationof the data with regards to students’ understanding of integrating SRDs into GDCin the Malaysian context.

Results

This section provides a summary of the results from the study. Respondent responsesare based on their reflection on the three situations or cases corresponding to thesocietal, environmental, and cultural concerns in Malaysia.

Students’ Understanding of Social Responsibility Dimensions in relation toGraphic Design Practices

All students responded positively and expressed their deep appreciation on thetelevision commercial (TVC). Most of them felt that this video was different fromthe mainstream commercial advertisements that were produced for selling purposes.All of them thought that the message of this video was very direct yet meaningful.It was about instilling family value to the public in Chinese New Year. “Kinship ismore important than materialistic enjoyment in life”, one student said.

Subsequently, all students asserted that designers have the responsibility todeliver positive message and desirable social value to influence the society. Onestudent posed an interesting statement and suggested “designers have to put morenutrition in commercial advertising”.

However, three students pointed out that it was the creative strategy that usedto communicate the societal-oriented message, which made it a successful TVC.“I think the director of this video use the comparison of two different expectationsfrom the elderly people on their children to bring out the message in a clevermanner”, one of the students claimed. Another two students believed that theeffectiveness of this video lied on its used of the emotional ingredients that cantouch people’s heart. As one of the students stated:

By communicating something, which is very related to yet being overlooked by the audiencesin their daily life, it is relatively easier to touch their heart. They might feel that this kind ofvideo very meaningful and emotionally connected.

More significantly, this kind of meaningful message created powerful long lastingimpacts in the audiences’ minds. Two students mentioned that:

I think this kind of advertisement will make the audiences remember for a very long periodof time. We are the witnesses.

I think this kind of socially oriented video with positive value is more enduring than thatkind of mere commercial message kind of video. The reason is clear because this [commercial]

554 MAN IN INDIA

video has been first published 8 years ago but now, we are here to talk about it, discover itsvalue. It is something amazing. How can an advertisement be so powerful? What is thereason?

Subsequently, one student suggested that:

I think we should swap the agenda… Normally money is the main agenda or commercialresult is the main agenda, then the hidden agenda is to touch their [the audiences’] hearts. Itshould be the other way round.

In addition, large numbers of students averred that designers have to identify theneglected social issues and people that deserve more attention in the society. Forexample, two students referred to this video and asserted that:

This video shows its concerns to the people in the society like elderly people, their livingconditions, and so on. From the conversation among the elderly people in the video, we canknow that our society is penetrated by those materialistic cultures and very realistic. I thinkthis video seems like a reminder to the audiences.

Through this advertisement, I also notice that we should care about the marginalized groupof people in our society. For example in this video, there is someone [designer or director]start to notice that their children gradually forget the elderly people in the old folk’s home.

Regarding the environmental issues in Malaysia, all students shared a common opinionthat graphic designers could use creative idea to educate public. Since visualcommunication is their expertise, they thought that to promote the environmentalawareness message to the public by strategizing a campaign is the least they can do.

In addition, three students mentioned that graphic designers could change theways or behaviors in which people use the design. Designers could think of thecreative idea to extend the “life” of the design by adding extra values. The centerquestion of this kind of idea, according to one of the students, is “how to avoid thedesign to be thrown away after fulfilling its primary purpose of protecting theproduct or communicating a message?” Another two students suggested that:

We can create design that can be used for second time. For example the flyer it is not onlymeant for reading or spreading out message but it can be brought back to home and dosomething extra.

Since we have the ability to alter how people use or consume the packaging, we can extendthe life of the packaging perhaps. Give the packaging second value…

Due to the exposures and the areas of specialization, students from Group-1 andGroup-2 did not deal with print work as many as students from Group-3. They diddo some print works like promotional items but were severely lesser than studentsfrom Group-3 and this had affected their awareness in selecting the papers andmaterials for their design. Two students mentioned that:

We just think that to use less paper can save money rather than anything relates to theenvironment.

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 555

We do not know the way we select the paper can contribute to environmental issues orproblems. [Basically] We just select the paper based on the suitability of our design concept.

Comparatively, all four students from Group-3 had better understanding of thecharacteristics and impacts of materials, colours, inks, and papers towards theenvironment. They pointed out that these were the aspects they would seriouslylook into when doing their design. One student claimed that this is “because thosechemical inks can also affect our environment” and therefore “the less inks weuse, the less impact of our design towards the environment”.

The video in case # 3 received different responses from the students. Twostudents showed their appreciations to the video and said that:

I appreciate [this video] very much…Her intention of wanting to make people laugh duringChinese New Year is definitely good. I mean good is that she just want to have fun, why soserious with political things.

I like this video. I think those issues [social injustice] should be delivered to Malaysian andthere must be one person who go and did that.

However, most students expressed their disagreements with the creation of thevideo. For example, one student from another camp argued that:

I don’t really like this video. No doubt this video is presenting some socially concernedissues to us, but I think that it seems like they are laughing at themselves because we are allin “satu” family…

More specifically, they did not like this video because of its poor execution on thecontroversial issues in Malaysia. The issues was told in a too direct manner andfailed to consider how different ethnic groups in Malaysia interpreted the message.One student maintained that:

I think to tell people about those issues are ok but the idea or execution can be muchbetter…I think if want to talk about these kind of sensitive issues in Malaysia where consistsof different ethnic groups, we need to be more symbolic or subtle instead of like this video,so direct and provocative.

What made the conflict become more complicated was the viral effect of socialmedia. There were so many people shared this video and it seemed like “let otherpeople to laugh at your country [Malaysia]”, one student claimed.

Hence, designers have to handle culturally sensitive issues with care especiallyin a country that consists of diverse ethnic groups like Malaysia. Designers canchoose to be a problem solver or a troublemaker. As one student suggested that:

I know that you want other people to laugh but eventually this kind of content will provokethe negative thinking of another group of people. I mean the reactions of the people arevery negative. As designers we have to solve the problems but not making the problemseven worse.

Subsequently, the students recommended two things, which the graphic designershave to be taken into account when dealing with similar issues in Malaysia. First

556 MAN IN INDIA

of all, some thought that designers have to understand that Malaysia comprises ofdiverse ethnic groups when doing their design. If the design fails to receive theacceptance of different groups of people, the harmonious state of the country canbe threatened. One student mentioned that designers have to respect everyone whostays in the country. Another student mentioned that:

I think we really have to go and understand about their culture [of each ethnic group] whenwe are doing [something] which really relate to them.

Secondly, some students also stated that designers have to care about everyonewho is going to be exposed to the design and message — how they interpret it andhow they feel about it. One student stated that:

Even though you have a target audience you have to be prepared that the ways in whichthose who are not your target audience thinks.

Nonetheless, as mentioned earlier, there are also students thought that this was asuccessful video if its intention was to provoke the negative emotions of differentethnic groups of people in Malaysia. Two students argued that:

I think it entirely up to the audience to interpret the messages. There may be one group ofpeople agree with this video but there may be another group of people disagree with thisvideo. I don’t see if there are any discriminating messages in this video.

I mean the audience has the ability to filter what they want and what they don’t want… Ithink designer is just an agent. We receive commission from others and do the job.

They thought that the audience should have the wisdom to interpret the messageand more importantly, they are not forced to watch the video.

The Ways in which Students Think about Social Responsibility Dimensions beingintegrated into Graphic Design Curriculum

All students mentioned that the societal dimension-related objectives were notofficially stated in the syllabus but were in the project outlines. Their lecturersgave verbal reminders and showed them related case study, examples or video atthe beginning of every project to encourage them to do something that can bringpositive results to the Malaysian society.

On the other hand, students from Group-1 and Group-2 claimed thatenvironmental dimension was not emphasized as much as societal dimension dueto the nature of their respective courses. A large number of students did not evenmanage to distinguish the issues between environmental and societal dimensions.They just mixed the issues of these two dimensions together. “You cannot actuallyblame us because we are not trained or taught to do print design”, one studentsuggested. These students stated that there were no related objectives stated in thesyllabus as well as in the project outline. However, Group-3 students provided atotally different opinion and mentioned that their lecturer put rather heavy weight

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 557

on environmental dimension in the course. They said that the lecturer always“warned” them sternly to reduce the harmful effects of their design to theenvironment by selecting the materials wisely.

All students declared that their lecturers place high emphasis on the designers’SR in cultural dimension. Though related objectives were not listed formally inthe syllabus and project outlines, all indicated that to study the local culture andlifestyle of the target audience in relation to the use of words and images is anunwritten rule in their GD courses.

On the other hand, the responses from the students showed that their lecturersused a variety of methods or strategies to deliver related content to them. Mostly,they said that their lecturers used PowerPoint, lecture, and video to enhance theirsocietal awareness as graphic designers. A lot of successful awareness campaignsthat done by other people were shown to the students and some expressed that theseexamples left strong impressions in their minds. For example, one student said that:

There was a class where the lecturer showed us a website for disabled [blind] people. Howdo you [we] consider the image [for blind people] when doing your [our website] design?

In addition, few students mentioned that they got the opportunity to have “informaldiscussions” with their lecturers after the class. According to them, duringdiscussions, the lecturers would share their personal experiences in dealing withthose social projects to inspire and influence them to do something similar. Onestudent described that:

He [The lecturer] always shared some small little social issues or our daily lives problemswhich most of the time, overlooked by us… I would surprise or shock why I didn’t thinkabout that before. He always asked us what could designer do to improve something?

Group-1 and Group-2 students said that there were related content regardingenvironmental dimension as they advanced through their respective courses, whichwere those kinds of environmental awareness campaigns. However, they all thoughtthat those examples were not part of the syllabus but something extra because therelated content was not given consistently throughout the entire course. Hence,they assumed that the lecturers showed those examples to them were not for thesake of promoting environmental awareness among them.

As for the students from Group-3, they mentioned that environmental awarenessor related content was delivered to them in a quite clever manner. On the one hand,video and Power Point were used to let them received the latest information aboutthe characteristics of different types of materials. On the other hand, they noticedthat the lecturer deliberately making himself as a role model to influence theirdaily habits. The students felt that the lecturer designed a lot of small actions andbrought a lot of interesting recyclable stuffs to the class in order to stimulate theircuriosity of “knowing why”. In such situation, interactive discussions happenednaturally and fruitfully. Two of the students gave examples and said that:

558 MAN IN INDIA

I remember he did bring an example to us where this paper bag is made of recycle paper.Everyone will be very curious and start asking about the paper bag…He will bring a lot ofpapers and show us which papers are biodegradable and more “green” and which are not.

…he will bring a plastic bottle come to the class and compress the plastic bottle in front ofus. He will not tell us why he does so, instead, he tends to want us to ask him personally...

All students declared that their lecturers did not include cultural dimension-relatedcontent in formal lecture but rather in the project discussion. They mentioned thatthe lecturers would request them to research thoroughly on the culture and lifestyleof particular group of target audience according to their individual projectrequirements. Based on the students’ critical analysis of the audience, the lecturerswould then take the opportunity to provide extra inputs to then.

Regarding the pedagogical processes, all students mentioned that their projectbriefs were very open and they were given freedom to choose what to do.However, most of them maintained that their lecturers inclined to encouragethem to make attempts at social awareness campaign. Some of them expressedthat they approached their projects due to the inspiring examples provided bytheir lecturers. During the design process, they felt that their lecturers always“troubled” them. This was because the lecturers tended to pose and address a lotof doubts and questions on them. These doubts and questions were mostlyregarding their analysis of research about the social issues and the practicality ofdesign solutions. Nonetheless, the students showed their appreciation towardthe commitments of the lecturers to give consistent feedbacks so that theycould make further reflection on the issues and do essential revisions on theirproject.

Since the design project briefs were very open, Group-1 students mentionedthat it was the personal preference to deal with environmental issues in their projectswhile Group-2 students stated that there was no related learning activity or projectaddressed environmental awareness to them in the course. Contrary, Group-3students claimed that every project in the course deal with environmental awarenesspertaining to the aspects of the use of papers, materials, sizes, inks and so on. Theirlecturer gave consistent reminders during the design process. They were urged toreflect again and again if there were better or greener materials could be used forparticular design solutions. More significantly, some projects were specificallydesigned to develop their environmental sensitivity. For example, one studentrecalled that:

I remember I was given the assignment to design a packaging to protect the eggs. I thinkthis project remind me in fact to protect an egg can use less paper. Which means that weshould also care about the size of design. The less we use the more materials or papers wecan save. And for this project we are only allow using one piece of paper.

All students agreed that they had adequate level of “cultural sensitivity” whendoing the different projects – it was “in” the project itself to study about the target

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 559

audience. During the weekly discussions, the lecturers would judge if the content,message, images, and words that the students developed were suitable for specificgroup of audience in Malaysia. In addition, the students were encouraged by thelecturers to do “visual analysis”. One student suggested an interesting outdoorlearning activity planned by the lecturer and said that:

I remember that was a time he brought us to go shopping. He wanted us to buy all thepackaging that related to one product. After that we need to bring all the packaging back toour class and do analysis on the aspects that we are talking like target audience, visual, andcopywriting…

For the societal dimension, the students thought that they were assessed formativelywhen they developed their projects. Weekly tutorials were conducted. Lecturerswould give feedback and suggestions to the students for further improvement basedon their research. These kinds of discussions were not limited to face-to-facecommunication in the class, there were students mentioned that their lecturers wouldgive extra comments to them through social media due to the limited time in class.One student suggested that:

We can ask him questions through Facebook, he will look at our project seriously, offersome extra inputs to us, even he will do some research and help us... He will post someuseful links in the group and keep showing examples to us.

However, during the summative assessment stage, all students declared that theirresults were solely determined by the effectiveness of the design solution and itsexecution. The lecturers did not assess the societal value of the projects, instead,according to one student, “they assessed whether your work works in the realworld, looks good, and nice or not…Basically they mark based on your skills, theydon’t mark how much of positive social value you put into your work”. There wasone student thought that the final assessment of the course focused more ondeveloping their commercial competencies instead of the sense of SR. “I think ourlecturer didn’t really indicate in the course [assessment] that he wanted us tobecome the “hero” to address or solve social problems or issues”, the studentmentioned.

Since environmental dimension was not part of the respective courses’ featureof Group-1 and Group-2, the students expressed that there was no related assessmentcarried out by their lecturers. For Group-3, the students said that the lecturers gavethem friendly but serious reminders about the selection of materials, papers, andetc. during the weekly tutorials.

Lastly, all students stated that the assessment of the cultural dimension wasdone during weekly tutorial and feedback regarding the analysis of target audienceand the use of images and words in their design. Not only in the formativeassessment, this dimension was also emphasized in the summative assessmentwith the criteria of “target audience” and “visual language”.

560 MAN IN INDIA

Discussion

The responses indicate that while all students acquire a sufficient understanding ofgraphic designers’ SR in societal and cultural dimensions in relation to GD field inthe context of Malaysia, their understanding of the environmental dimension tendsto be lacking in general.

Putting More “Nutrition” into Commercial Advertising

Students as a whole present a good understanding of SR in societal dimension becausemost of their responses could be found in the literature (e.g. Shea, 2012; Berman,2009; Perkins, 2006). The responses of the students indicate their understanding ofthe very nature of GD is social, that graphic designers have to deal with differentrange of human action related issues (Friedman, as cited in Sassoon, 2008). Morespecifically, they asserted that since the designers have the ability to shape publicinformation, they could address the overlooked social issues, disclose the needs ofmarginalized groups, and deliver positive messages in a creative and persuasivemanner to influence the action and behavior of the people in the society.

In addition, graphic designers can move across commercial boundaries andmake their design more socially meaningful and inspiring. With regards to this,one student posed an interesting statement that “designers have to put more nutritionin commercial advertising”. Such statement means that graphic designers can moveaway from the creation of the excessive and useless needs among the public (Perkins,2006; Berman, 2009) and move towards the production of more useful and longlasting communication that contributes to the betterment of the society (Garland,1964; Poynor, 2005). Another student added that graphic designers nowadaysshould “swap the agenda” to focus more on the social side instead of the commercialside of the design. Such focus suggested by this student did not mean that thedesigners should ignore the needs of the commercial clients but instead; a reversalof priority in the GD practice is needed. Certainly, these responses suggest thatstudents in the study understand the graphic designers’ job is much more than justmaking the design looks appealing for commercial purposes. Designers cancontribute towards the betterment of their society.

Using Less to Reduce the Environmental Impacts

The responses of the students indicate that the majority of them are lacking of theenvironmental awareness of the graphic designers. Despite the students of Group-1 and Group-2 (two-thirds of all students) were able to spell out that graphicdesigners can use their visual communication skills to promote the awareness amongthe public by strategizing effective campaigns to deal with the environmental issuesin Malaysia, they did not show their further understanding of the environmentalimpacts with regards to the selection of the raw materials, production methods,usage, and disposal issues for the GD products. For example, as one of the students

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 561

said, “…we do not know the way we select paper can contribute to the environmentissues or problem…we just select the paper based in the suitability of our designconcept”. Comparatively, the students from Group-3 (one-thirds of all students)demonstrated a better understanding of the characteristics and impacts of materials,colours, inks, and papers towards the environment. Particularly, they pointed outthat these were the key aspects they would look into when creating the design. Oneof the students claimed that this is because “those chemical inks can also affect ourenvironment” and therefore “the less inks we use, the less impact of our designtowards the environment.”

Handling Culturally Sensitive Issues with Care

Most students believed that graphic designers should be the peacemakers. Sincegraphic designers have the power to shape public information and message, thestudents said that they have to handle culturally sensitive issues with care especiallyin a socially and culturally diverse context such as in Malaysia. With such power,graphic designers have an immerse responsibility to understand the distinctiveculture of various audiences in the society to avoid communicating insensitiveinformation and message. Most of the students understand that different audiencescan perceive an information or message in different ways and so graphic designershave to interpret the issues, subject matters, topics, images, and words to be usedin the design objectively. Such understanding of students reflects the culturalconcerns of graphic designers as suggested by Meyer (2008) earlier in the literature.Nonetheless, quite a numbers of the students said that to concern with the cultureof different audiences does not mean that the designers should feel oppressed whendealing with the sensitive issues, instead, the key question is: How those sensitiveissues can be ingeniously put across to the general public without offending orinsulting other people who live in the same context? This requires not only thetalent of the graphic designers but also their choices – whether they want to bepeacemakers or troublemakers.

On the other hand, however, there was a small amount of students claimedthat graphic designers are merely the agents of communication and so the selectionof issues, subject matters, topics, images, and words should depend on the purposesof the design and the needs of the clients. A provocative design with aggressivemessage cannot be considered as failure or insensitive if it is created with thepurpose of stimulating the provocative reaction or emotion of the audiences. Hence,these students felt that the audiences themselves should have the wisdom to interpretthe information and message and more importantly, they should “have the abilityto filter what they want [to see or believe] or what they don’t want [to see orbelieve]”, one of the students argued.

Then on these GD students think of how the SRDs are integrated by theirlecturers into the curriculum purposes, content, pedagogical processes, and

562 MAN IN INDIA

assessment methods, respectively, the results indicate that there were no formallywritten goals or objectives statements in their syllabus or related curriculumdocuments regarding the different SR dimensions. Despite the students said thattheir lecturers in general did provide verbal reminders or examples about thedifferent SRDs at the beginning of the semester with the purpose of picturizing therespective courses to them, not all SRDs were given equal amount of “informal”emphasis, especially the environmental dimension. For example, while the studentsfrom Group-3 mentioned that their lecturer put rather heavy weight onenvironmental dimension in the course, students from Group-1 and Group-2 claimedthat there were no related examples or reminders given by their lecturers about theenvironmental concerns due to the nature and focus of their courses. It should bemore significantly noted that these two groups of students did not even be able todifferentiate the responsibility of graphic designers in between environmental andsocietal dimensions. With such responses from the students, it appears too stronga statement to say that SRDs are not being given adequate amount of emphasis intheir GD courses as compared to those formal and intended goals or objectives,which relate to the “technical skills set” of graphic designers. Such “informal”practices made, may be entirely upon personal preferences of lecturers, obviously,do not fulfill the requirements of MQA (2012) to serve SR as one of the significantdomains of intended learning outcomes.

In a positive step, however, the students in the study expressed that theirlecturers did find ways to integrate different SRDs into other curriculumcomponents, specifically in the content and pedagogical processes. As for therelated content, most of the students said that the lecturers tended to show a lotof successful and meaningful examples that were done by other people whileexplaining particular social role of graphic designers to them. According to them,these examples were shown in a variety form of media such as video clips, socialmedia, website, poster, brochure, packaging design, and so on. There was also acollective tendency of the students to agree that these examples left quite a strongimpression in their minds. However, “I would say these examples [in relation toSRDs] were not given throughout the entire course but there were certaintimes the lecturer gave us some very inspiring examples”, as stated by oneof the students. This statement implies that those SRDs-related examplesplay only a supporting role in the GD courses and are not the main content forlearning.

In addition, students from Group-2 and Group-3 said that they did acquirerelated information while having “informal discussions” with their lecturers afterthe class. The content in these informal discussions, according to these students,included the sharing of the lecturers’ personal experiences and practices. Thestudents expressed that they were really enjoyed and interested in those kinds ofinformal discussions. For example, a student described that:

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 563

He [The lecturer] always shared some small little social issues or our daily lives problemswhich most of the time, overlooked by us. And every time after he shared his experiences tome, I would surprise or shock why I didn’t think about that before.

In addition, students from Group-3 observed that their lecturers inclined to“compress plastic bottles” and “use recycle bag” in front of them and such actionshad stimulated their curiosity of “knowing why”. Students said that informal yetinteractive discussions just happened naturally and fruitfully with their lecturers,as it was themselves who took the initiative to know more. Collectively, studentsstated that they could digest this kind of environmental-related information moreeffectively as it stored better in their minds. The responses of the students indicatethat informal discussions after the class can act as a powerful way of delivering thecontent in relation to different SRDs to the students and more importantly, thelecturers lead students by making themselves as role models.

All students mentioned that in general there were no specific design projects,which deal with the societal, environmental, and cultural dimensions respectively.It was entirely up to their individual preference if they wanted to explore relatedissues. Only students from Group-3 stated that they were once given a packagingdesign project that aimed at enhancing their environmental sensitivity. Nonetheless,some students said that they would explore those societal, environmental, andcultural issues in Malaysia due to the encouragements and inspiring examplesprovided by their lecturers. Hence, further understanding of different SRDshappened during when they discussed the projects with lecturers. According tothese students, their lecturers inclined to pose them a lot of questions regardingtheir analysis of research, content of design, ideas and solutions, selection ofmaterials and media, use of words and images, and they encouraged them todiscover, inquire, and reflect further. From the answers of the students, it isapparently clear that their GD lecturers conducted classes in a rather interactiveand reflective manner and they are encouraged them to learn actively andindependently during the design process.

In addition, as compared to societal and environmental dimensions, theresponses of students indicate that cultural dimension is somehow “inherited” inGD. They study the cultures and lifestyles of target audience in every design projectwith the intention to develop content, message, ideas, words, and images that canbe accepted by them.

All students agreed that their lecturers mostly assessed SRDs formatively duringstudents’ design projects. Weekly tutorials were conducted and feedbacks weregiven for further improvement or change. On the other hand, during the summativeassessment, all students declared that their results were mainly determined by theeffectiveness of the design solution and its execution. A student said that basicallylecturers grade the design projects based on the outcomes and skills, and theyseldom grade positive values that they integrate into their works. Subsequently,

564 MAN IN INDIA

another student pointed out that: “I think our lecturers didn’t really indicate in thecourse that he wanted us to become a “hero” to address those social problems orissues”. In relation to such responses of the students, both Kvan (2001) and Lawson(2006) state that outcome-oriented assessment, which serves the final designoutcomes as the primary measurement of the performance, can affect studentsfocus on the design outcome instead of the process. Consequently, students mayoverlook the socially significant learning value generated in the design process. Inother words, there is a high tendency that socially significant learning does noteffectively occur among students even though they receive very good results inrelated design projects.

Conclusion

The present article reports a study conducted to seek GD students’ understandingof SRDs and the ways in which SRDs were integrated to GDC from the Malaysiancontext. The evidences show that students have a sufficient understanding of SRin societal and cultural dimensions, but inadequate understanding of theenvironmental dimension. In addition, students viewed that clear efforts have beenmade by their lecturers towards integrating SRDs into the GDC, although notformally and comprehensively in each curriculum component. This in turn suggeststhat further steps need be taken that precise and distinctive issues of concern ineach SRD are accurately considered, and delivered in the GD related programs ina comprehensive manner. With regards to this, the future Program Standards bythe MQA may make specific references to “social responsibility” and to the meansof integrating SR in relevant contents, pedagogical processes, and assessmentmethods of individual courses in GDC.

References

Adbuster. (2000). The First Things First Manifesto.Retrieved September 24, 2013 from: https://www.adbusters.org/blogs/why-i-am-renewing-first-things-first-manifesto.html

Akama, K. (2008). Whose Role is it anyway? Communcation Design and Designer’s Role inSociety. Retrieved February 19, 2015 from: http://newviews.co.uk/london 2008/pdf/Cluster_6.pdf

American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA). (2014). Deign Business + Ethics.Retrieved September24, 2013 from: https:// www.aiga.org/landing.aspx? pageid=10591&id=51

Berman, D. (2009). Do Good Design. California, USA: New Riders.

Costandius, E. and Rosochacki, S. (2012). Educating for a Plural Democracy and Citizenship –A Report on Practice. Perspectives in Education, 30(3), 13-20

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research Methods in Education (5thed.). NewYork: RoutledgeFalmer.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Enquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among FiveApproaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Findeli, A. (1994). Ethics, Aesthetics, and Design. Design Issues, 10, 49-68.

STUDENTS’ UNDERSTANDING OF INTEGRATING... 565

Frascara, J. (1997). User-centred Graphic Design: Mass Communications and Social Change,London: Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Garland, K. (1964). First Things First Manifesto. London: Goodwin Press.

Harland, R. (2011). The Dimensions of Graphic Design and Its Spheres of Influence. DesignIssues, Volume 27, Number 1 Winter 2011, 21-34.

Heller, S. (2005). The Education of a Graphic Designer. New York: Allworth

Heller, S., Fernandes. T. (2006). Becoming a Graphic Designer: A Guide to Careers in GraphicDesign. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

Heller, S. and Vienne, V. (2003). Citizen Designer: Perspectives on Design Responsibility. NewYork: Allworth Press.

Kingston University London. (2015). Graphic Design BA (Hons). Retrieve March 1, 2015 from:http://www.kingston.ac.uk/undergraduate-course/graphic-design/

Malaysian Qualifications Agency (MQA). (2012). Program Standards: Art and Design. RetrievedJune 30, 2014 from: http://www.mqa.gov.my/portal2012/ garispanduan/ART_Final%20BI%2029022012.pdf

McCoy, K. (1994). Countering the Tradition of the Apolitical Designer. In: Myerson, J. (Eds)Design Renaissance: Selected papers from the International Design Congress, Glasgow,and Scotland 1993. Horsham: Open Eye, 105-114.

Meyer, R. (2008). Culture, Context, and Communication: Developing a Culturally SensitiveCurriculum in Graphic Design Education. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations.(AAT 1454660)

Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE) (2009). The Mission of Ministry of Higher EducationMalaysia.Retrieved September 24, 2013 from: http://www.mohe.gov.my/educationmsia/index.php? article=dept

Mononutu, C. (2010). Design Social Responsibility: Ethical Discourse in Visual CommunicationDesign Practice. Retrieved September 24, 2013 from: http://dgi-indonesia.com/design-social-responsibility-ethical-discourse-in-visual-communication -design-practice/

London College of Arts. (2015). BA (Hons) Graphic and Media Design. Retrieve March 1, 2015from: http://www.arts.ac.uk/lcc/courses/undergraduate/ba-hons-graphic-and-media-design/

Papanek, V. (1977). Design for the Real World:Human Ecology and Social Change. New York:Academy Chicago Publishers.

Perkins, S. (2006). Ethics and Social Responsibility. Retrieved September 24, 2013 from: http://www.aiga.org/ethics-and-social-responsibility/

Poynor, R. (2005). First Things First: Revisited. Retrieved September 24, 2013 from: www.strg-n.com/edu/hgkz_BuK/files/first_things.pdf

Sassoon, R. (2008). The Designer: Half a Century of Change in Image, Training, and Technique(p. 6, 13). Chicago, IL: Intellect Books, The University of Chicago Press.

Shea, A. (2012). Designing for Social Change: Strategies for Community-Based Graphic Design.New York, USA: Princeton Architectural Press.

Social Impact Design Summit. (2012). Design and Social Impacts: A Cross-Sectorol Agenda forDesign, Education, Research, and Practice. Retrieve September 24, 2013 from: http://arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf \

566 MAN IN INDIA

Swinburne University of Technology. (2015). Communication Design Major - 2010. RetrieveMarch 1, 2015 from: http://www.swinburne.edu.au/study/courses/ specialisations/515.

The International Council of Graphic Design Association (ICOGRADA). (2011). ICOGRADADesign Education Manifesto 2011.Retrieve September 24, 2013 from: http://www.icograda.org/education/manifesto.htm

Thorpe, A. (2006). The Designer’s Atlas of Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Tung, M. (2002). Good Design is Good Business. In Hanan, A.A. and Rahim, E (Eds), YoungGraphic Designers Workcamp (pp.42-49). Malaysia: Arjo Wiggins Ltd.

Vesselle, S. and Mckay, B. (2011). A Case Study of an Innovative Graphic Design CurriculumFocusing on Social Responsibility. Design Principles and Practices: An InternationalJournal, 5(5), 471-487.

Whiteley, N. (1993). Design for Society. London: Reaktion Books.