Strings and Stringing - great bass viol and stringing.pdf · Stringing Techniques of Harpsichord...

Transcript of Strings and Stringing - great bass viol and stringing.pdf · Stringing Techniques of Harpsichord...

FRIEDEMANN HELLWIG

Strings and Stringing: Contemporary Documents

THE 1974 issue of this JOURNAL contains two papers which surely are remarkable to everyone interested in the problems of strings

and stringing techniques of historical instruments: Djilda Abbott's and

Ephraim Segerman's article on Strings in the 16th and 17th Centuries offers an explanation of the early stringing techniques of lutes, viols, and citterns, and-perhaps even more important--gives an introduc- tion into the physics behind them, applicable to all kinds of stringed instruments, keyboards included. With the information drawn from it the much discussed papers on the stringing of Italina harpsichords by Shortridge, Barnes, Thomas, and Rhodes, and others (published mostly in this JOURNAL) become more transparent. The second article, Stringing Techniques of Harpsichord Builders undertakes an attempt to correlate findings of old wire on historical instruments to written sources. The two papers make it clear that further historical material in regard to instruments, wire and wire-trading, and written docu- ments will be needed for future research. It is the aim of this paper to provide material of this kind.

I. GAUGE NUMBERS ON KEYBOARD INSTRUMENTS In the Germanisches Nationalmuseum all clavichords, harpsichords,

spinets, virginals, and a number of pianofortes and square pianos received a thorough examination during the past years. String gauge numbers have been found on some twenty of them. They are listed below together with the string lengths of top and bottom notes and all intermediary Cs. No further comment is offered in order to avoid hasty conclusions about the kind of gauge system to be applied.

I Clavichord, fretted (MIR 1053). Tyrol (?), c. 1725 f - h 4 String lengths: cl - f1' 5 not original gl - c#2 6 dC - b?2 7 b2 - e3 8

9'

2 Fretted clavichord (MIR os54). Christian Gottlob Hubert, Bayreuth 1763 f 4 String lengths: b 5 C 114.5cm f#1 6 c 87.5 d2 7 cl 53.4

C2 28.I C3 14.0 f3 10.7

3 Unfretted clavichord (MIR 1o62). Johann Anton Fuchs, Innsbruck 1781 F 1/o String lengths: C I FF II16.o cm e 2 C 104,4 a 3 c 79.4 d' 4 c' 49.0 g1 5 c2 25.2 d#2 6 C3 14.0 b2 7 f3 12.7 f- 7(!)

4 Unfretted clavichord (MINe 67). Mathieu Schautz, Augsburg 1793 G xi/o String lengths: B I FF 132.4 cm

c# 2 C 119.2 d# 3 c 90.3 b 4 c' 61.2 fi 5 c2 33.5 dz 6 c3 I8.I b ?2 7 P 14.0

5 Unfretted clavichord (MINe 72). Johann Paul Kraemer & Soihne, G ittingen 1798 8': FF ooo 4': FF o String lengths:

FF0 ooot FF ot 8': FF 143,1 cm 4': FF 106,4 cm GG oo GG I C 126.8 C 96.2 GG# ooi GG# Ii F II5.o F 89,8 BB? o A 2 c 95.8 C o0 BB 21 c 50.0 D I C 3 c2 25.5 E It C 3 c3 12.4 F3 o D 4 a3 7.2 G ot D# 40 G# I F 5 A I* B 2 d 21

92

8': e 3 f# 31 g# 4 c' 41 gt 5

c2 51 g2 6 d3 61

6 Unfretted clavichord (MINe 71). North German, end of i8th century 8': A oj String lengths:

B? o in a later hand 8': FF 143.x cm 4': FF IO3,I cm B I C 117.o C 84.4 c 2 c 83.6 A 64.1 d• 21 ct 49.3 f1 3 cZ 23.4 a 3 c3 11.7 c1 4 g3 7.5 d#1 41

gt 5 d#2 51

bz 6 d#3 61

7 Unfretted clavichord (MIR 1063). Broedler, Vaihingen/Enz 1809 c I String lengths: g 2 FF 122.o cm el 3 C 0o2.6 c#2 4 c 71.8 f#2 5 c' 43.4 c3 6. Stahl c2 24.5

c4 13.3 (Stahl: steel) c' 6.7

8 Unfretted clavichord (MINe 73). German, beginning of I9th century 8': E 2/o 4': FF o String lengths:

F o FF# I not original G I GG# 2 A 2 BB 3 c# 3 D# 4 f 4 F gelb 5 f#' 5 F weif 5 e2 6 A 6 (gelb: yellow) g3 7 B 7 (weil3: white)

93

9 Unfretted clavichord (MINe 74). South German, c. I820 D# oo String lengths: G o FF 133.5 cm c I C 122.4 g 2 c 91.7 di 3 c1 62,7 fz 4 C2 32.0 g3 5 c3 16.1

C4 9.0 f' 6.6

io Harpsichord (MINe 78). Giovanni Battista Giusti, Lucca 1681 fl 8 String lengths: d2 9 C/E I52.o/15o.9 cm cs 1o c 104.0/99.5

c 53.-1/51.1 c2 27.6/25.1 c3 13-7/13-2

xI Harpsichord (MI 449. On loan). Martinus Vater, Hannover, c. 1700oo c I String lengths: g 2 GG/BB 156.8/154.7 cm

d# 3 9th-centuryC

153.7/150.6 c2 4 addition?

c 102.9/98.6 f2 5 c1 5L.8/49.5 b2 6 c2 26.5/25.4 eS 7 c3 13.9/13.4

es 11.4/10.9

Iz Harpsichord (MI 450). Joseph Mahoon, London 1742 8': FF 13 String lengths:

GG 12 8': FF I84.9/183.3 cm 4': FF Io6.6cm BB II C I69.2/165.5 C 91.2 D Io c 116.9/113.8 c 60.6

F# 9 c' 67.7/65.3 c' 33.3 B? 8 c2 34.4/33.1 c2 16.2 d 7 c3 17.4/16.6 c3 7.9 g# 6 f3 13.5/13.1 f3 6.o di 5 g#1 4 On loan from the Colt Collection, e2 3 Bethersden, Kent c#3 2

13 Harpsichord (MI 451). Jacob Kirckman, London 1750 FF 13 String lengths: GG 12 FF 179.9/178.9 cm

94

AA xi String lenghts: BB io C 163.8/x66.o D 9 c 119.3/116.5 F# 8 c' 69.3/67.2 c 7 C2 34.7/33.6 f 6 c3 17.4/16.5 c#~ 5 f3 13.2/12.7 c2 4 On loan from the Colt Collection

14 Octave spinet (MINe 94). Italy, c. 1700 A 5 String lengths: c# 6 C/E 63.o cm g 7 c 49.4 d$c 8 ct 29.3 br, 9 C2 13.3 dC2 10 C3 5.2 c3 II

IS Fortepiano (MIR 11o4). Johann Andreas Stein (?), Augsburg, c. 1780 FF Miss f String lengths: GG Moss f FF 169.7 cm BB[ Moss 0 C 152.2 $ c 107.5

E Q c' 57.2 F A Stahl C2 29.0 B I c3 14.5 a 2 f3 11.4 at 3 f 4 (M6ss= Messing: brass) c4' 5 (Stahl: steel)

16 Fortepiano (MIR Ixos). Ignaz Joseph Senft, Augsburg, c. 1780 FF 5/o String lengths: GG 4/o FF i69.ocm AA 3/o0 C 153.9 C 2/o0 c 105.2 E i/o ct 55.7 F# St(ahl) c2 27.2 c I c3 13.9 bI 2 f3 Ix.O bb' 3 g#2 4 (Stahl: steel)

17 Fortepiano (MIR I107). Nanette Streicher, Vienna, c. 18o7 FF 0 String lengths: GG 8 FF 167.9cm

95

AA 8 String lenghts: BB t C 152.9

D#$ c 103.8

F 3 cl A

o C2 27.8

1 cs I3.8 C c0 13.8

f# - c' 7.6

a' 2

fz 3 c# 4 g3 5

x8 Fortepiano (MINe 136). South German, c. 182o B 3/ot String lengths: d4 2/o CC 179.5 cm a 2/o0 C I57.o e' I/o c 104.9 bi I/oi c' 52.7

fz2 I C2 27.2 ~#3 Ii C3 13.2

c#4 2* c4 6.3 f4 5.o0

19 Fortepiano (MIR 1119). Conrad Graf, Vienna, c. 1826 FF 6/o String lengths: AA 6/o0 CC 193.o cm

C# 5/s C 152.5 F 5/o0 c III.2 A 4/o c' 54.6 d 4/o0 c2 27.5 g 3/o c3 13.8 c#1 3/0o c4 7.2 f1 2/o f4 5.6 c#2 2/o0 g#2 0 Brass: FF-G# (111.7 cm) d3 Steel: A (130.2 cm)-f

4

gsS I c#4 Ij

20 Square piano (MIR 1152). South German, end of I8th century c# I String lengths: d# 2 not original f# 3 b 4 d#1 3 f#1 4

96

b s 5 fz 6

21 Square piano ('Clavecin royal'; MIR 1161). Christian Salomon Wagner, Dresden 1794 d z String lengths: d# 21 (?) FF I52.o cm f 3 C I28.o b 30 c 95.2 fl 4 c1 62.2 b' 4* C2 33.5 f2 5 (?) C3 I8.o b2 5t g3 Iz.o

2. OLD WIRE GAUGES On the occasion of a visit to the Municipal Museum of Ulm my

attention was attracted by three simple pieces of steel with slots at the sides and numbers next to them. They proved to be early measuring tools for thicknesses of wire, similar to those illustrated in books from the 17th century onwards, describing the process of wire drawing.' In the course of the past year some twenty gauges have been examined in the Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena (Westphalia), in the Stiedtische Sammlungen fiir Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Ulm, and in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. Although none of them can be more than vaguely related to gauge systems of musical instruments I would like to give a general description of how to use them, and to offer a list of measurements taken from six gauges from four centuries. I hope that gauges clearly used by the musical instru- ment craft will be found one day.

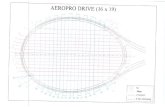

Wire gauges2 consist of steel plates (oblong ones have handles at one end) with slots of varying sizes along the sides, each of them with a number or letter next to it (Pl. IX). In order to measure a piece of wire the narrowest slot through which the wire would pass has to be found. The diameter of this slot is considered the diameter of the wire; the gauge number belonging to this slot therefore indicates the gauge number for the wire in question. The wire is passed through the slots from the edge of the plate towards its centre. The wire can be pulled out through the circular hole in which the slot ends, without passing the slot once more.3

All wire gauges found, including those illustrated in Plate IX, 1 to 6, have now been measured by introducing thickness gauges into their slots. Inaccurate though this method is, it showed that the reduction of wire diameters may vary considerably in the drawing process. A

97

constant reduction factor may have been aimed at; however, without accurate means of diameter determination it must have remained an approximation (the modern micrometer was not invented before the second half of the past century).4

i Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena/Westphalia. Inv. No. P 882/xo. I6th/ 17th century? 5 o.81 mm K o.9o F i.05 K 12 1.18 12 1.29 4 i.6o 3 1.8o

2 Stiidtische Sammlungen fur Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Ulm. Signed: Felmi [Selmi?] 1627 I ? 13 1.12 mm 2 0.14 mm 14 1.21 3 0.35 I5 1.25 4 0.36 16 1.32 5 0.42 17 1.45 6 o.65 18 1.38 7 0.55 19 1.65 8 o.58 20 i.8o 9 o.88 21 1.95 10 o 0.93 22 2.0 II 0.95 23 2.2 12 I.OO 24 2.6

3 Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena. Inv. No. P 882/28. Signed: [?] HD 1736// DG 6 M 0.38 mm 51 G 0.57 5 S 0.63 40 K 0.70 4 F 0.98 30 12 1.26 3 K 2* 12 1.30 2 4 1.46 Ii 3 1.63 I

F K F

98

4 Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Niirnberg. Inv. No. Z. 170. Signed: ANNO 17 ANDREAS MONATH 59 DEN 6 OCTOBER I 0.19 mm 13 o.89 2 O.12 14 I.oo 3 o.17 15 1.02 4 0.22 16 1.2o 5 o.26 17 1.24 6 0.34 18 1.44 7 0.48 19 I.58 8 o.62 20 1.69 9 0.71 21 1.85 o10 o.81 22 2.00

II 0.88 23 2.3 12 0.90 24 2.5

5 Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena. Inv. No. P 882/14. Signed: 18 H 2o//FT 7 ? 6B 0.75 6* o.24 mm 5 B o.85 6 o.26 4 B 0.97 51 o.28 3 B 1.18 5 0.29 I B(!) 1.36 4 o0.32 2 B 1.45 4 0.35 4 1.70 3* 0.36 3 1.85 3 0.38 M 2.25 2 o0.41 N 2.6 2 0o.44 K 3.0 li 0.45 F 3.5 I o.46 GM 4.1 F 0.49 M 4.7 K 0.5I FR 5,5 F 0.55 GR 6.0 M o.6o S 6.7 G o.65 K 7.8

6 Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena. Inv. No. P 2991 g. Signed: M I902// W. Schneider

2o ? II 0.70 19 ? 10

o 0.72 18 ? 9 o.85 17 0.36 mm 8 0.90 16 0.40 7 0.94 15 0.48 6 1.03 14 0.50 5 1.o8 13 0.58 4 1.17 12 o.65 3 1.24

99

2 1.30 3/0 1.60 I 1.35 4/0 1.80 0 1.44 5/0 o 1.95

2/o 1.49 6/0 2.05

3. GAUGE NUMBERS OF MUSICAL WIRE IN SOUTH GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, EARLY 19TH CENTURY A most interesting and at the same time most reliable source on

wire drawing is Karl Karmarsch's article on Draht (wire) in Johann Joseph Prechtl's Technologische Enzyklopadie which appeared in the I83os.1 Karmarsch, born in Vienna, later living in Hannover where he founded the Institute of Technology, is known as a scholar devoted to turning the hitherto largely empirical technology into a scientific discipline. In his treatment of the various aspects of wire and its pro- duction he frequently mentions musical wires. The passages of interest are quoted in the following:

(p. 2io:) Gauges and gauge numbers of Austrian and Styrian factories; thick- nesses according to the wire drawn by one of the finest producers (at Frauen- thai):

No. thickness, Zoll

5 Saitendraht 0o.o04 6 Instrumentdraht 0.012

7 detto o.o0o 8 detto o.oo9 9 detto o.oo8

Io detto 0.007 0 detto o,oo6

(p. 211:) Products from Carinthian factories: Name thickness, Zoll

Saitendraht 0.015 ditto Nro. o o0.013 ditto Nro. oo o.o011 ditto Nro. ooo 0.OLO ditto Nro. oooo 0.oo9 ditto Nro. ooooo o.oo8

(pp. 212, 213:) Amongst the fine wires are Claviersaiten which are drawn mostly by their own workmen from coarser wires on handwheels (without further annealing), and which are numbered in a peculiar way when sold. The Nuremberg strings famed for their excellent quality exist in I3 sorts IOO

which are marked by numbers in the following way: 9/ot [read 91 zero] is the coarsest kind; then follow 9/o, 8/o0, 8/o, and so forth as far as 2/o, oi, o, and further I, II, 2, z2 as far as 61, 7. At Nro. 9/o0 the thickness is 0.039 Zoll; at Nro. 7 only 0.oo8 Zoll. In Vienna, where presently wire strings are made equal in quality to those of Nuremberg, one has them in 17 sorts of the numbers 8/o, 7/o as far as 2/0, o, I, 2 as far as 9. The thickness of Nro. 8/o is 0.050 Zoll, that of Nro. 9 however 0,008 Zoll.

(p. 220:) The brass Claviersaiten are hard-drawn from good brass wire on handwheels, also polished to give them a fine shine ... They are numbered equal to the iron ones.

The quoted texts display the variety of gauge systems used in a limited area at the beginning of the 19th century, a variety which might appear weak information through the fact that Karmarsch failed to state the kind of Zoll he referred to. Fortunately, he gives various tables with diameters of wire in Zoll and the number of feet of wire

weighing one pound. He also gives the specific weight of the wire in

question in comparison to water. From these tables the fixed relation between the foot measure (I foot =12 Zoll) and a pound can be established which can then be compared to measures given elsewhere in the encyclopedia.6 The result is that Karmarsch used the Wiener Fufi equalling 316.I mm; one Zoll would therefore be 26.34 mm.

The especially interesting task of converting and further elaborating the data on the Nuremberg and Viennese gauges is accomplished in the following manner (taking the Nuremberg wire as an example): The measurements of the thickest and the thinnest strings are trans- formed into their metric equivalent:

no. 9/0o = 0,039 Zoll = I.027 mm no. 7 = 0,008 Zoll = 0,211 mm

The intermediary gauges are assumed to follow a constant factor x for all 30 steps of diameter reduction;7 this would amount to:

1.027 X30 = 0.211

x 30 0,211

S1,037

x = 0.94587 or c. 5.4%

The figure for the Viennese gauges would be o.89217 or c. IO.8%

The diameters of the various Nuremberg and Viennese gauges may then be calculated:

IOI

Nuremberg gauge system 9/0t 1.o27 mm 2/0 0.465

9/o 0.974 o1 o.441

8/o0 o.924 0 0.419

8/o o.877 I o.397 7/o0 o.832 It o.377 7/0 0.789 2 0.357

6/o0 0.748 21 0.339

6/o o0.710 3 0.322

5/o* 0.673 3 o0.305 5/o 0.638 4 0.289 4/01 o.6o6 4* 0.274

4/o 0.575 5 0.260

3/01 0.545 5* 0.247

3/0 o0.517 6 0.234

2/01 o 0.491 6f 0.222

7 0.211 Viennese system

8/o 1.317 mm I 0.529 7/0 1.175 2 0.472

6/o 1.048 3 0.421

5/o 0o.935 4 0.375

4/ 0 o.834 5 0.335

3/0 0.744 6 0.299

2/0 0.664 7 0.267

o 0.593 8 0.238 9 0.211

Two things seem noteworthy: the reduction factor of Vienna is twice that of Nuremberg. Has Karmarsch perhaps omitted intermediary gauges with half numbers which are indeed suggested by the gauge numbers found on instruments of Viennese provenance? Secondly, the Viennese gauge system is almost identical to the system communicated by Bakeman as 18th-century French.8 This would lead to a certain scepticism as to the validity of region and time that Bakeman attributes to his various gauge systems.

4. STRINGS ON ITALIAN HARPSICHORDS When in 1960 John Shortridge published his paper on Italian

Harpsichord-Building in the 16th and 17th Centuries9 he could hardly have foreseen what controversies would derive from his observations about the variation of string lengths found in early Italian keyboard instruments and its interpretation. With W. R. Thomas's and J. J. K. Rhodes's contribution on String Scales on Italian Keyboard Instruments'0 IO2

the discussion became so stirred that the question of brass or steel on an Italian instrument was passionately debated wherever two organ- ologists met. Unfortunately the authors' arguments--though perfectly clear to them--appeared contradictory and confusing to many of their readers (a good portion of the subsequent disputation filled the following pages of this JOURNAL). John Barnes, for the Graz restorers' conference in 1971, summarized the results of his own and other people's research in an excellent lecture.11 Following him, Italian harpsichords should be strung in brass, with the pitch varying in accordance with the string lengths found in the individual instrument. Brass was claimed to be the authentic material on the grounds of the Pythagorean scaling of the Italian harpsichord. Barnes admitted that historical documents from the country in question were not known.

In fact, any further confirmation or damnation of the Edinburgh brass theory was to be expected from Italian sources. Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini, organist, organologist, and collector of early keyboard instruments, has indeed found two passages in support of the above suggestions. In a letter of 26 March 1975 Tagliavini has communicated to the Germanisches Nationalmuseum that about 1630 a certain Padre della Tavola, Maestro di Capella del Santo di Padova, affirmed that he possessed a fine cembalo constructed in 1570 by Vito Trasuntino, 'gi' con l'ottavina' and 'alla quarta bassa' (quoting della Tavola's wording, i.e. 'formerly with an octave' and 'at the lower fourth').

The second finding of importance has recently been published by Tagliavini12 but has probably been overlooked: at the beginning of the I8th century Angelo Furio of Todi justified the variety of different pitches with the tuning of the quilled instruments because 'il cembalo codato et armato di corde d'argento o d'ottone richiede il suono pib grave del non codato, o sia spinetta quadrangolata armata di corde d'acciaio' (quoted from Furio's text; i.e. 'because the wing-shaped harpsichord furnished with strings of silver or brass demands a lower sound than the non-wing-shaped, or quadrangular spinet furnished with strings of steel').

Tagliavini's findings need no further explanation. However, a word of approval has to be said in honour of those who on the basis of technological considerations have come to understand the Italian harpsichord in a way that has now been confirmed by historical documents.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The data on gauge numbers found on instruments in the Germanisches Nation- almuseum forms part of a catalogue being prepared by DrJ. H. van der Meer.

1o3

I thank him for allowing me to publish the above extracts from his material. Furthermore, I have to thank the staff of those museums which gave permission to examine wire gauges under their care, especially so Dr H. H. Diedrich of the Deutsches Drahtmuseum, Altena. Professor Wolfgang Freiherr von Stromer, an expert on the Nuremberg history of economics and on early wire-drawing techniques, very kindly drew my attention to Karmarsch's writings. Finally, I am grateful to Professor Tagliavini who so readily conveyed his findings to his colleagues at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum.

NOTES I E.g. in: Johann Samuel Halle, Werkstdtten der heutigen Kiinste, Brandenburg

and Leipzig 1761, 1762. Diderot and D'Alembert, Encyclopidie raisonnie. 2 German: Drahtlehre, Drahtmafl, Klinke. French: calibre, jauges defils. 3 Free translation of Karl Karmarsch's contribution on 'Draht' (wire) in

Johann Joseph Prechtl, Technologische Enzyklopddie oder alphabetisches Handbuch der Technologie . . ., vol. 4, Stuttgart 1833, pp. 141-233 (the pssaages quoted from pp. 149, I50).

4 0. H. DShner,

Geschichte der Eisendrahtindustrie, Berlin 1925, p. oo. 5 See note 3. 6 K. Karmarsch, Gewichte und Mape, vol. 6, Stuttgart 1835, pp. 559-567. 7 See note 3, P. 170o. 8 GSJ XXVII (1974), P. 99. 9 Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., Bulletin No. 225. io GSJ XX (1967). ii 'The Stringing of Italian Harpsichords', in: Vera Schwarz (ed.), Der

klangliche Aspekt beim Restaurieren von Saitenklavieren. Bericht ... Beitriige zur Aufftihrungspraxis, Schriftenreihe des Instituts fiir Auffiihrungspraxis der Hochschule fir Musik ... in Graz (V. Schwarz ed.), vol. 2, Graz 1973, PP. 35-39.

12 'Considerazione sulle vicende storiche del corista', in L'Organo, XII, no. 1-2 (January-December 1974), pp. 120-132. Quoting Angelo Furio from Todi (1687-1723), Libretto Seconda-Piena Instruttione sopra lIntavolatura (Bologna, Biblioteca Musicale 'G. B. Martini', MS. D 52), p. is: Della regola da osservarsi nell'accordare I'istromento.

I04

-li

(I) (2) (3)

(4) (5) (6) PLATE IX

(see p. 97) Wire ga uges:

(1) 16th/17th century (Deutsches Drahtmusen,,, Altena Westphalia)

(2) Fehlni 1627 (Stidtische Samnlungen, Ulm)

(3) HD 1736 DG (Deutsches Drahtmiusemun) (4) Andreas Monath 1759 (Germanisches Nationaluseium,, Nuremberg) (5) H 182o FT (Deutsches Drahttituseutiu) (6) M 1902 W. Schneider (Deutsches Drahtmnuseum)