Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in Outpatients with Congestive Heart Failure

-

Upload

barbara-appleton -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

1

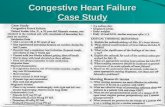

Transcript of Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in Outpatients with Congestive Heart Failure

Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11): 693-698LEADING ARTICLE 1173-8790/03/0011-0693/$30.00/0

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved.

Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in Outpatientswith Congestive Heart FailureImpact on Clinical and Economic Outcomes

Nicholas D. Palmer,1 Barbara Appleton2 and Erwin A. Rodrigues2

1 Cardiothoracic Centre, Liverpool, UK2 Aintree Cardiac Centre, University Hospital Aintree, Liverpool, UK

Congestive heart failure (CHF) encompasses a spectrum of clinical syndromes and presentations. It affectsAbstract1–2% of the population in the UK and is associated with significant mortality which is comparable to mostcancers. It accounts for more than 5% of adult medical admissions in the UK, with significant annualre-admission rates. Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of CHF has resulted in significant advance-ments in CHF management. Current pharmacologic agents, such as ACE inhibitors, β-adrenoceptor antagonistsand spironolactone, influence symptoms and improve mortality. Despite this, many patients still requirehospitalization. Multiple, potentially reversible factors are involved which, if addressed effectively, may result insignificant reductions in re-admission rates. Patients with CHF often have other conditions, such as respiratorydisease, resulting in prolonged lengths of stay. Suboptimal care and failure to adhere to management guidelinesis also a preventable cause for re-admission. There has been an increasing need to develop adjunctive,non-pharmacologic strategies for managing CHF, which are designed to improve the patient’s functional statusand quality of life. Key elements include systematic follow-up care and patient education. The concept ofintensive outpatient or home-based CHF intervention has been developed and extensively evaluated in severalrandomized controlled trials. Early studies were inconclusive but provided an indication that discharge planningand home-based education are valuable strategies. Recently, an increasing number of studies utilizing the CHFnurse practitioner have provided positive results for non-pharmacologic intervention and demonstrate thepotential of these interventions to reduce admissions to hospital by up to 50%. These studies had specificinclusion criteria and could not be generalized to the CHF population as a whole. The Study to Evaluate theeffectiveness of Nurse-led Intervention in the management of outpatients with heart Failure (SENIF) exploredwhether a similar approach to CHF management was beneficial in a typical outpatient population of patients withCHF. Over 12 months, fewer intervention group patients required admission, resulting in 69% fewer hospitaldays. Cost effectiveness of nurse-led intervention has been suggested in several studies including SENIF,resulting from reduced hospitalizations and re-admissions, which vastly outweighed the modest increase inexpenditure required to run the programs. Hospitalizations because of CHF impact greatly on limited healthcareresources. Specialist nurse-led intervention in CHF is a cost-effective, non-pharmacological strategy to helpoptimize CHF management.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a complex pathologic process moderate to severe left ventricular impairment, which is com-associated with a spectrum of clinical syndromes and presenta- parable to most cancers.[2,3] Current data suggests an incidence ratetions. It is seen as an escalating public healthcare problem affect- of 1/1000 population, rising to 12/1000 in octogenarians.[4] Al-ing approximately 1–2% of the population in the UK.[1] Annual though an improved prognosis for CHF has been demonstrated,mortality ranges from 10–50%, depending on the severity of heart predominantly because of pharmacologic interventions such asfailure, and average survival is only 2.5 years in patients with ACE inhibitors[5,6] and β-adrenoceptor antagonists,[7] CHF re-

694 Palmer et al.

mains a significant burden on healthcare resources and results in ularly highlighted in the Cooperative North Scandinavianpoor health-related quality of life and premature mortality. Recent Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS), in which hospital re-studies have shown that the incidence of CHF is under-reported admissions for CHF among patients actively treated with ACEsince it tends to be regarded as a consequence of a primary inhibitors remained in the order of 40–50%.[17]

condition such as coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease or2. Factors Relating to Hospitalizationshypertension.[8]

In the UK, over 150 000 hospitalizations annually are a directMultiple factors contribute to hospital admission in up to 90%result of CHF, accounting for more than 5% of adult medical

of patients with CHF.[18,19] Potentially reversible causes such asadmissions.[9] In the US, it is the most common cause of hospitali-poor understanding of CHF, poor compliance with medication andzation in people over the age of 65 years[10] whilst re-admissiondiet, poorly controlled ischemic heart disease or hypertension,within 1 year occurs in 33% of patients and is influenced predom-respiratory infections (because of lack of immunization) and inad-inantly by an increasing population of elderly people.[11] Notequate discharge planning and follow-up are well recognized. Itsurprisingly, CHF absorbs a significant, and steadily increasing,has been suggested that if these issues were addressed effectivelyproportion of healthcare resources, accounting for 1–2% of totalthey would be likely to reduce re-admissions by 40–50%.[20]

healthcare expenditure in developed countries, with a dispropor-tionate amount utilized in repeated hospitalizations.[12]

3. Other Aspects of CHF ManagementThe aim of the current review is to provide the rationale for

specialist nurse-led intervention in CHF and provide the back- Despite compelling clinical evidence and major advances inground evidence for its efficacy from clinical and economic as- pharmacologic management, the high re-admission, morbidity andpects. Our experience of such a program in the form of the the mortality rates associated with CHF have not been completelyStudy to Evaluate the effectiveness of Nurse-led Intervention in ameliorated. Some argue that the rise in hospitalization rates couldthe management of outpatients with heart Failure (SENIF[13]) is be a result of more accurate reporting strategies.[4] However,also described as a potential model for the management of CHF in most authors concur that patients with CHF have the highest re-a real-world population of patients. A literature search was under- admission rates of all patients, with 8% of all patients dischargedtaken on Medline using the key words ‘heart failure’, ‘nursing’ with CHF being re-admitted within 3 months.[10,21] Inadequateand ‘management’. Additional data were obtained from studies quality of care and frequent failure to achieve best practice incited as references on acquired leading papers in the area of eligible patients are seen as preventable causes for re-admissionnurse-led intervention in CHF. and is often traced directly to the healthcare provider.[22] Factors

related to healthcare providers have been identified in 10–21% ofrelapses.[23] These factors include doctors failing to translate clin-1. Pharmacologic Advances in Congestive Heartical evidence into practice. There are many barriers, includingFailure (CHF) Managementissues such as lack of continuing education of busy health profes-sionals, lack of time and awareness, inadequate communicationIn the last 20 years there have been significant advancements inbetween specialities and other healthcare providers, and costs,CHF management related to improved understanding of the patho-especially of drugs. Practice guidelines have removed some obsta-physiology, better methods of assessment and improved treatment.cles. However, there is strong evidence that patients not treated byIn addition, there are a number of pharmacologic agents thata cardiologist have up to a 7-fold increased risk of re-admission.[24]significantly influence symptoms, slow the progression of theAn example of this treatment gap can be demonstrated by the useillness and improve the patient’s quality of life and survival. ACEof ACE inhibitors. In a number of studies of the optimal manage-inhibitors have been shown to reduce mortality and morbidityment of patients with heart failure, a significant proportion ofbecause of their influence on the ventricular remodeling process.eligible patients who were treated by general physicians were notBenefit has been demonstrated following myocardial infarction[6]

receiving these drugs and therefore not benefiting from theirand in patients with chronic left ventricular dysfunction resultingeffect, compared with patients being treated by cardiologists.[25-28]from ischemic or non-ischemic etiologies.[5] More recently, impor-

tant symptomatic and prognostic benefits have been demonstrated Noncompliance with drug treatment ranges from 42% towith the use of β-adrenoceptor antagonists[7] and spirono- 64%.[28,29] The factors that contribute to noncompliance includelactone,[14] while therapies such as digoxin[15] and nitrates[16] are misunderstanding of instructions given by healthcare practitioners,useful adjuncts. Despite these pharmaceutical advances, a high polypharmacy, patient perceptions, forgetfulness and senility. Aproportion of patients requires hospitalization. This was partic- further consideration should be that older patients or patients with

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11)

Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in Outpatients with Congestive Heart Failure 695

complex health problems are at considerably greater risk of re- uate the effectiveness of these interventions there have been aadmission. Patients with CHF often have other significant co- number of major randomized controlled trials of nonpharmaco-morbidity, such as diabetes mellitus, respiratory disease and renal logic intervention in CHF.dysfunction, resulting in more frequent hospitalization and pro- In a study conducted before the pharmacologic developmentslonged lengths of stay.[30,31] of today, Hansen et al.[39] provided district nurse visits on day one

It is well established that CHF is a complex health issue that and general practitioner visits 2 weeks later for CHF patients in arequires management with evidence-based drug regimens. Yet the primary care setting. The study assessed healthcare utilization overmanagement of CHF is a universal healthcare problem and to 1 year, but little or no benefit was demonstrated. In 1999, Naylor etaddress this problem, agreed pharmacologic strategies for treat- al.[40] undertook a study of comprehensive discharge planning byment have been published at the international,[32] national,[33] and practice nurses that demonstrated a short-term reduction in re-local level. These guidelines are being seen as an important admissions but no long-term benefit.[40] The use of a self-caremilestone of change by providing a systematic review of treatment behavior model in patients with CHF produced benefit with re-options and a practical and comprehensive approach to CHF. They spect to symptoms and hospitalizations but was unable to meet thenot only recommend the most effective drug treatment, but also primary outcome of cost effectiveness.[41] While these studiessupport the view that the role of nonpharmacologic intervention is were inconclusive, they provided a clear indication that dischargea key element in the care of patients with CHF. planning and home-based education were valuable strategies and,

perhaps combined within a different approach, may have the4. Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in CHF potential to be effective.

There are an increasing number of studies that have providedpositive results of nonpharmacologic intervention and reduction in4.1 Evidence for its Effectivenesshospital use. Rich et al.[42] reported that nurse-led intervention had

There has been an increasing need to develop adjunctive strate- beneficial effects on rates of re-admissions, quality of life and costgies for managing CHF. The primary aim is to identify the ‘high- of care at 90 days among over 250 high-risk, elderly patients withrisk’ patient who is frequently readmitted to hospital. Subsequent severe CHF. This was the first study to evaluate a program ofinterventions should be designed to improve the patient’s func- comprehensive education and follow-up, including home-basedtional status and quality of life, while addressing the deficiencies and clinic-based visits, with frequent telephonic contact. Thein healthcare systems that can lead to poor health outcomes. The principal goals of follow-up were to reinforce the patients’ educa-key elements of any strategy should include adequate social ar- tion, ensure adherence to diet and medication, and to identifyrangements and assistance, with systematic follow-up care and recurrent symptoms amenable to treatment on an outpatient basis.clinical monitoring. In addition, it is well known that patient Survival for 90 days without re-admission was achieved in 91 ofeducation has a positive effect on quality of life and results in 142 patients (64%) in the intervention group compared with 75 ofdecreased admission rates because of better awareness of CHF.[33] 140 (54%) in the usual care group (p = 0.09). A 56% reduction inThis education should include general topics such as diagnosis and hospital re-admissions was noted in the intervention group (p =treatment, activity and dietary recommendations, medication and 0.02). The intervention also resulted in an improvement in qualitythe importance of compliance with treatment plans. A flexible of life (p = 0.001) and reduced healthcare costs of $US460 perapproach to education, which includes family and caregivers, is patient compared with the usual care group (1994 values). Interest-essential. Other aspects of a successful comprehensive service ingly, 1-year follow-up showed a similar trend, indicating that ashould include access to primary care and specialized follow-up. relatively brief intensive approach continued to impact for someUndoubtedly, this systematic management is not readily available time after its cessation.[42] Similar results were produced in ain mainstream healthcare and is unlikely to be successfully estab- further study by Stewart et al.[43] Hospitalized patients with im-lished without a cohesive evidence-based approach. To rectify this paired left ventricular systolic function, poor exercise toleranceinadequacy in care, the concept of intensive outpatient or home- and a history of at least one admission for heart failure werebased CHF intervention has been developed and evaluated in a randomized to usual care (n = 48) or home-based intervention,number of countries throughout the world. The provision of this comprising a single visit 1 week after discharge to optimizecoordinated approach can take place in a number of facilities medical therapy, identify early clinical deterioration and improveincluding specialist centers for heart failure management,[34] CHF medical follow-up where appropriate (n = 49). Study endpointsclinics,[35] comprehensive community-based management sys- were frequency of unplanned re-admission and out-of-hospitaltems,[36] or multidisciplinary hospital-based services.[37,38] To eval- deaths over a 6-month period. Patients receiving the intervention

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11)

696 Palmer et al.

had fewer re-admissions (p = 0.03), out-of-hospital deaths (p = effect of this intervention is since there was limited follow-up in0.11), and days of hospitalization (p = 0.05) than patients receiving all the studies. Furthermore, the mechanisms of the beneficialusual care. effect are unclear but they probably relate to improved treatment

compliance and patient education, and early detection of clinicalCline et al.[44] evaluated an in-hospital education program, plusdeterioration thus avoiding hospital admission. Finally, no studiesfollow-up at specialist nurse-led heart failure clinics, in 206 pa-have clearly demonstrated improved survival because of insuffi-tients aged 65–84 years. This included self-assessment – self-cient patient numbers and relatively short follow-up, although itmanagement criteria with an educational program for patients andmay not be possible to show benefit in the elderly, chronically illtheir families mainly concerning treatment issues. The patientpatients in these studies.undertook two hospital visits, and one home visit was performed 2

weeks after discharge, followed by access to a nurse-led clinic for The described randomized studies of nurse-led management in8 months. A trend towards a reduced mean number of hospital CHF have some limitations. In general the selected population ofadmissions was demonstrated in favor of patients receiving the patients, such as the elderly, had severe CHF and was randomizedintervention (p = 0.08), but more significantly, there was a longer following a hospital admission with CHF. Selection criteria weremean time to re-admission (106 vs 141 days, p < 0.05). Other somewhat specific, with exclusion of other chronic disease pro-studies were designed on a multidisciplinary, single home-based cesses that might affect hospitalization rates.[51] In more recentintervention at 7–14 days post-discharge. A better event-free sur- studies the inclusion criteria were broader with regard to age andvival (38% vs 51%, p = 0.04) and fewer re-admissions compared co-morbidity, thus allowing for comparison of strategies in condi-with standard care were demonstrated.[45] Blue et al.[46] also evalu- tions approximating everyday clinical practice.[46] The SENIF trialated a home-based intervention, based on more regular home visits explored whether a similar approach to CHF management iswith telephone contact. A 25% reduction in re-admission and 50% beneficial within a typical outpatient population of patients withreduction in length of hospital stay resulted. Other models of CHF.[13] The study was designed with the ability to translate itsintervention, including a nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary inte- findings to general medical healthcare systems, both community-grated approach between primary and secondary care, are current- and hospital-based. It was undertaken in a single teaching hospitally under evaluation. that covers a population of 330 000 in an area with a high inci-

The efficacy of nurse-led services has also been shown in the dence of heart disease. The sample population was selected frommanagement of hyperlipidemia,[47] smoking cessation,[48] hyper- patients with moderate to severe CHF who attended a cardiologytension,[49] and diabetes mellitus.[50] From these studies and the clinic. They were required to be clinically stable and to have notCHF studies it can be concluded that the effect of adjunctive been admitted to hospital within the preceding 3 months. The trialnonpharmacologic intervention has the potential to prevent admis- sought to investigate the impact of nurse-led intervention in ansions to hospital by approximately 50% and prolong survival outpatient population of patients with respect to hospital ad-without adversely affecting quality of life. They provide clear mission rates and quality of life over a 1-year period. The mainevidence that adjunctive intervention is highly effective and rivals intervention in the active care group was a series of planned clinicthe effectiveness of some individual drugs.[26] The research re- or home visits, during which patients and their caregivers receivedviewed identifies a number of different models of care, which a comprehensive program of care, including an initial assessmentprovide similar elements, including education, support and access of patients and their caregivers, and an educational program to-to care. The common theme throughout all these trials is the CHF gether with information on self-management, detecting clinicalnurse practitioner, who appears to be a key component in CHF deterioration, diet and drug compliance. The nurse had the oppor-management, whether that is home-based intervention, hospital tunity to discuss patients with the cardiologist and to optimize andclinics or an integrated care program. simplify pharmacologic regimens, as necessary. Regular follow-

The debate will continue as to whether home-based or clinic- up with the nurse took place for 12 months. Fifty-five patients,based intervention is the more effective strategy. It may be that a mean age 63 years, were randomized to usual care or intervention.combination of home- and clinic-based follow-up, an approach not Similar baseline characteristics were noted between the groups. Inyet studied, will prove to be the most effective of all. In addition, the intervention group, there were two admissions because of CHFfurther research is still needed to establish the optimal timing and compared with 14 in the usual care group (risk ratio 0.14, p =frequency of the interventions that have already proved effective. 0.02). Hospital admission for any cause was reduced by 81% in theFrom the studies described in this section, benefit was obtained intervention group (risk ratio 0.19, p = 0.01). No significantusing both high-intensity (Rich et al.[42]) and low-intensity pro- difference in death rate was noted between the two groups. Multi-grams (Stewart et al.[43]). It is unclear what the precise duration of ple re-admissions were more frequent in the usual care group

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11)

Specialist Nurse-Led Intervention in Outpatients with Congestive Heart Failure 697

(15.4% vs 0%, p = 0.04). The total number of days of hospitaliza- effectiveness of nurse-led intervention has been suggested intion was reduced, with 157 in the usual care group and 29 in the several studies, including SENIF,[13] on the basis of reduced hospi-intervention group, and there was a difference in hospital bed talizations and re-admissions, which in all cases vastly outweighedusage of 81.5% (p = 0.01). This difference in hospital bed usage the modest increase in expenditure required to run a nurse-ledresulted almost exclusively from a reduction in the number of program in CHF. For instance, Rich et al.[42] described a $US460hospitalizations since the length of stay was similar in both groups. (1994 values) saving per patient over a 90-day follow-up period,

resulting entirely from the reduced re-admission rate. The clinic-In the US, because of the pressure to lower healthcare costs,based approach of Cline et al.[44] produced a mean annual reduc-cost containment and length of hospital stay are other standardtion in healthcare costs of $US1300 (1997 values) [p = 0.07 vsoutcome measures used in most nurse-led intervention studies.usual care]. In a relatively stable population of CHF patients, theThe main aim of many of these studies is to reduce length of stay.SENIF trial confirmed these findings, with a mean annual costTopp et al.[52] reported a reduction in length of stay from 6.29 daysreduction of £838 (2000 values) [p = 0.03].[13] This degree of costto 4.6 days after implementation of CHF management guidelines.benefit compares very favorably with other scenarios such as theIt would appear that the American concept of managing acute CHFimpact of lipid-lowering therapy or coronary artery bypass graft-is fast and aggressive, and that patients are rapidly treated for theiring on the incidence of further coronary events.clinical deterioration and swiftly discharged. However, the US has

a higher incidence of re-admissions, which may be a consequence5. Conclusionof short hospital stays. In comparison with American studies, the

average length of stay in the UK has dropped from 11.4 days inThe management of CHF in the recent past has focussed1990 to 8 days in 1993.[11] This reported average of 8 days is

predominantly on pharmacologic therapy based on clear clinicalsimilar to the SENIF trial,[13] which reported an average length ofevidence. However, hospitalizations resulting from CHF are stillstay of 7.5 days, with no difference in the intervention comparedincreasing, because of multiple factors, resulting in a significantwith the usual care group.burden on limited healthcare resources. The evidence fornonpharmacologic intervention in CHF, with the use of specialist4.2 Optimization of Drug Therapynurse-led intervention, is compelling. The adoption on a wide-spread basis of such an inexpensive, cost-effective program helpsIn addition to other studies, the SENIF trial[13] demonstratedoptimize the management of a common and debilitating condition.that nurse-led intervention provides an effective method for opti-

mizing the use of ACE inhibitors, β-adrenoceptor antagonists andAcknowledgementsspironolactone, both in hospital and in the community. West et

al.[37] reported a significant increase in effective treatment withThe authors received no sources of funding and have no conflicts of

nurse-led management. In this setting, close adherence to guide- interest directly relevant to the content of this review.lines and protocols was undertaken, while a safety net was pro-vided by identifying patients who failed to respond to treatment,

Referencessimplifying drug regimens and monitoring effectiveness. Ulti- 1. Ho KK, Anderson KM, Levy D, et al. Survival after the onset of congestive heart

failure in Framingham Heart Study subjects. Circulation 1993; 88: 107-15mately, it is argued that patients who are receiving optimal drug2. Royal College of General Practitioners, Office of Population Census and Surveys,treatment and other advice will feel better, have an improved

and the Department of Health and Social Security. Morbidity statistics fromquality of life and stay well for longer.[25] This in turn will reduce general practice: fourth national study, 1991-2. London: HMSO, 1998

3. Sanderson S. ACE Inhibitors in the treatment of chronic heart failure: effective andhospitalizations and the economic burden to the health service.cost-effective. Bandolier 1994: 1 (8): 14-7

4. Cowie MR, Wood DA, Coats AJ, et al. Incidence and aetiology of heart failure: a4.3 The Economics of Nurse-Led Intervention population-based study. Eur Heart J 1999; 20: 421-8

5. SOLVD investigators. Effects of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced leftventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991;In view of the increased number of patients with CHF there is a325: 293-302

need to ensure that they receive optimal management and effective 6. Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Investigators. Effects of ramipril onmortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction withutilization of limited healthcare resources. The National Serviceclinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993; 324: 821-8Framework in the UK has recognized that effective management

7. MERIT Investigators. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: meto-of CHF does not occur consistently throughout the health ser- prolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure

(Merit-HF). Lancet 1998; 353: 201-7vice.[33] The overwhelming positive evidence from the numerous8. Murdoch DR, Love MP, McMurray JJV, et al. Importance of heart failure as astudies of nurse-led intervention in CHF is now resulting in the cause of death: changing contribution to overall mortality and coronary heart

implementation of similar programs throughout the world. Cost disease mortality in Scotland 1979-1992. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 1829-35

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11)

698 Palmer et al.

9. Murray J, Hart W, Rhodes G. An evaluation of the cost of heart failure to the 35. Abraham WT, Bristow MR. Specialist centre for heart failure management. Circu-National Health Service in the UK. Br J Med Econ 1993; 6: 91-8 lation 1997; 96: 2755-7

10. Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, et al. Hospitalisation of patients with heart 36. Houghton AR, Cowley AJ. Managing heart failure in a specialist clinic. J R Collfailure: national hospital discharge survey 1985-1995. Am Heart J 1999; 137: Physicians Lond 1997; 31 (3): 276-93520-60

37. West JA, Miller NH, Parker KM, et al. A Comprehensive management system for11. McMurray J, McDonagh T, Morrison CE, et al. Trends in hospitalisation for heart heart failure improves clinical outcomes and reduces medical resource utilisa-

failure in Scotland 1980-1990. Eur Heart J 1993; 14: 1158-62 tion. Am J Cardiol 1997; 79: 58-6312. McMurray J, Petrie MC, Murdoch DR, et al. Clinical epidemiology of heart 38. Kegel LM. Advanced practice nurses can refine the management of heart manage-

failure: public and private health burden. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 9-16 ment failure. Clin Nurse Spec 1995; 9 (2): 76-8113. Appleton B, Palmer ND, Rodrigues EA. Study to evaluate specialist nurse-led 39. Hansen FR, Spedtsberg K, Schroll M, et al. Geriatric follow-up by home visits

intervention in an outpatient population with stable congestive heart failure: after discharge from hospital: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 1992;results of a prospective, randomised study (the SENIF trial) [abstract]. J Am

21: 445-50Coll Cardiol 2002; 39 (9): 33B

40. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R. Comprehensive discharge planning and home14. Randomised Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) investigators. The effect of

follow-up of hospitalised elders: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA 1999; 281:spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure.

613-20N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 709-1741. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG, et al. Does increased access to15. Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG). The effect of digoxin on mortality and

primary care reduce hospital readmissions? N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1441-7morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 525-3342. Rich MW, Beckham V, Carney RM, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to16. Northridge DB. Nitrates in heart failure. BMJ 1996; 12: 352-6

prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl17. CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe

J Med 1995; 333: 1190-5congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian

43. Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD, et al. Effects of home-based intervention onEnalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 1429-35unplanned readmissions and out-of-hospital deaths. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998; 46:18. Vinson JM, Rich MW, McNamara T. Early readmission of elderly patients with74-80congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990; 38: 1290-5

44. Cline CMJ, Israelsson BYA, Erhardt LR, et al. Cost effective management19. Opasich C, Febo O, Riccardi G, et al. Concomitant factors of decompensation inprogramme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart 1998; 80: 442-6chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol 1996; 78: 354-7

45. Townsend J, Piper M, Frank AO, et al. Reduction in hospital readmission stay of20. Chin MH, Goldman L. Factors contributing to the hospitalisation of patients withelderly patients by a community based hospital discharge scheme: a randomisedcongestive heart failure. Am J Public Health 1997; 87: 643-8controlled trial. BMJ 1998; 297: 20-7

21. Gooding J, Jette AM. Hospital readmissions among the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc46. Blue L, Lang E, Morrison CE, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist-led1985; 33: 595-601

intervention in heart failure. BMJ 2001; 323 (7315): 715-822. Andrews K. Relevance of readmission of elderly patients discharged from ageriatric unit. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34: 15-21 47. Cofer LA. Aggressive cholesterol management: role of the lipid nurse specialist.

Heart Lung 1997; 26 (5): 337-4423. Michalsen A, Konig G, Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading tohospital admissions with decompensated heart failure. Heart 1998; 80: 437-41 48. Taylor CB, Debrusk R. Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction:

effects of a nurse-managed intervention. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113: 118-2324. Reis SE, Holubkov R, Feldman AM, et al. Treatment of patients admitted to thehospital with congestive heart failure: speciality-related disparities in practice 49. Perry HM, Sambhi MP, Cusham WC, et al. The VA hypertension and screeningpattern and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 733-8 programme. Nurse Pract 1992; 11: 54-60

25. Stevenson LW. Tailored therapy before transplantation for treatment of advanced 50. Peters AL, Davidson MB, Ossorio CR. Management of patients with diabetes byheart failure: effective use of vasodilators and diuretics. J Heart Lung Trans- nurse with support of sub-specialists. Arch Intern Med 1995; 9: 8-12plant 1991; 10: 468-76

51. Fonarow GC, Stevenson LW, Woo MA, et al. Impact of a comprehensive heart26. Cleland JGF. Health economic consequences of pharmacological treatment of

failure management programme on hospital readmission and functional statusheart failure. Eur Heart J 1998; 19 Suppl. P: 32-9

of patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30: 725-3227. McMurray JJV. Failure to practice medicine based medicine: why do physicians

52. Topp R, Tucker D, Weber C. Effect of a clinical case manager/clinical nursenot treat patients with heart failure with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibi-

specialist on patient hospitalised with congestive heart failure. Nurs Casetors? Eur Heart J 1999; 20 Suppl.: 15-22Manag 1998; 3: 140-7

28. Davidson F, Haghfelt T, Gram LF. Adverse drug reactions and drug compliance asprimary cause of admission to a cardiology department. Eur J Clin Pharm 1988;34: 83-6

About the Author: Dr Nicholas Palmer is a Senior Specialist Registrar in29. Monane M, Bohn RL, Gurwitz JH, et al. Non-compliance with congestive heart

Cardiology at the Cardiothoracic Centre in Liverpool, England. His prima-failure therapy in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1994; 154: 433-7ry clinical and research interest is in percutaneous coronary intervention.30. Victor CR, Vetter NJ. The early admission of the elderly to the hospital. AgeMrs Barbara Appleton is the Senior Specialist Congestive Heart FailureAgeing 1985; 14: 37-42nurse at University Hospital Aintree in Liverpool. She has led the develop-31. Williams EL, Fitton F. Factors effecting early unplanned readmissions of elderlyment of the nurse-led CHF service and has a continuing research interest inpatients to hospital. BMJ 1988; 297: 784-7

this area. Dr Erwin Rodrigues is Consultant Cardiologist and Clinical32. Task Force on Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines forthe diagnosis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 1995; 16: 741-51 Director for Cardiology at University Hospital Aintree. He has played an

integral role in developing specialist nurse-led services in the centre.33. Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Coronary HeartDisease. London: Department of Health, 2000

Correspondence and offprints: Dr Nicholas D. Palmer, The Cardiothoracic34. Smith LE, Fabbri SA, Pai R, et al. Symptomatic improvement and reducedCentre, Thomas Drive, Liverpool, L14 3PE, UK.hospitalisation for patients attending a cardiomyopathy clinic. Clin Cardiol

1997; 20: 949-54 E-mail: [email protected]

© Adis Data Information BV 2003. All rights reserved. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 2003; 11 (11)